Gonzalez v. The Home Insurance Company Reply Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

December 22, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gonzalez v. The Home Insurance Company Reply Brief for Petitioner, 1989. 090b89a1-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f26ce424-d039-4476-8c9b-cdae284c0593/gonzalez-v-the-home-insurance-company-reply-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

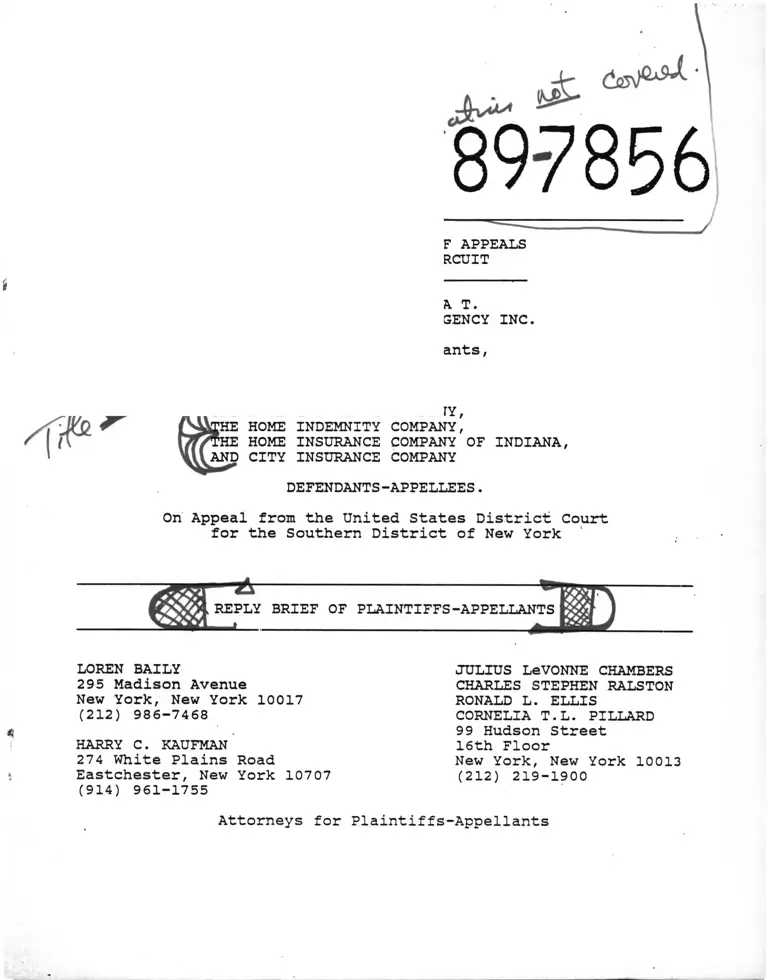

EDWARD F. GONZALEZ, ANA T.

GONZALEZ, AND A.T.G. AGENCY INC.

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

THE HOME INSURANCE COMPANY,

HOME INDEMNITY COMPANY,

HOME INSURANCE COMPANY OF INDIANA,

AND CITY INSURANCE COMPANY

, Jr

" * 89-7856

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of New York

LOREN BAILY

295 Madison Avenue

New York, New York 10017

(212) 986-7468

HARRY C. KAUFMAN

274 White Plains Road

Eastchester, New York 10707

(914) 961-1755

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

RONALD L. ELLIS

CORNELIA T.L. PILLARD

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...................................... ii

INTRODUCTION .............................................. 1

I. IN RESPONSE TO PATTERSON, PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS HAVE

PROPERLY ADVANCED ADDITIONAL ARGUMENTS TO SHOW THAT

THEIR COMPLAINT STATES A SECTION 1981 CLAIM ......... 1

II. THE COMPLAINT CLEARLY ALLEGES THAT PLAINTIFFS CONTRACTED

WITH TWO PAIRS OF DEFENDANTS AT TWO DIFFERENT TIMES, AND

EACH CONTRACT WAS DISCRIMINATORY WHEN FORMED ........ 3

III. PLAINTIFFS' STANDING IS NOT BASED ON THE RIGHTS OF THIRD

PARTIES .............................................. 7

IV. PATTERSON DOES NOT BAR SECTION 1981 CLAIMS OF

DISCRIMINATORY CONTRACT TERMINATION ................. 9

CONCLUSION ................................................. 1 1 l

l

CASES

Albert v. Caravano. 851 F.2d 561 (2d Cir. 1988) .......... 2

Barkan v. Hilti 89-C-318-E (N.D.Okla. October 12, 1989) ... 9

Chevron Oil Co. v. Huson. 404 U.S. 97 (1971) ............. 1, 2

Conley v. Gibson. 355 U.S. 41 (1957) ...................... 3

D. Federico Co. v. New Bedford Redevelopment Authority,

723 F. 2d 122 (1st Cir. 1983) ........................... 2

DeMatteis v. Eastman Kodak, 511 F.2d 306 (2d Cir. 1975)

modified on other grounds, 520 F.2d 409 (2d Cir. 1975) . 7, 8

Gersman v. Group Health Ass'n. 1989 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 13449

(D.D.C. Nov. 13, 1989) ................................. 8

Johnson v. Mateer, 625 F.2d 240 (9th Cir. 1980) .......... 2

Lopez v. S.B. Thomas. Inc., 831 F.2d 1184 (2d Cir. 1987) .. 8

Lvtle v. Household Manufacturing, Inc.,

88-334, 106 L. Ed. 2d 587 (1989) ....................... 9

Mackey v. Nationwide Ins. Co.. 724 F.2d 419 (4th Cir. 1984) 8

Martin v. New York State Deo11 of Mental Hygiene,

588 F. 2d 371 (2d Cir. 1978) ............................ 2

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 109 S. Ct. 2363, 105 L.

Ed. 2d 132 (1989) .................................... Passim

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union. 50 F.E.P. Cases at 1173 . 3, 5

Phelps v. The Witchita Eagle-Beacon,. 886 F. 2d 1262

(10th Cir. 1989) ....................................... 8

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229 (1969) ..... 7, 8

The Dartmouth Review v. Dartmouth College, 1989 U.S. App.

LEXIS (1st Cir. Nov. 9, 1989) .......................... 8

INTRODUCTION

Defendants-appellees' arguments dwell on issues irrelevant

to plaintiffs-appellants' section 1981 claim, and seek to

undermine plaintiffs' claims largely by mischaracterizing them.

I. IN RESPONSE TO PATTERSON. PLAINTIFFS-

APPELLANTS HAVE PROPERLY ADVANCED ADDITIONAL

ARGUMENTS TO SHOW THAT THEIR COMPLAINT STATES

A SECTION 1981 CLAIM

Defendants repeatedly point to a change in emphasis in

plaintiffs' arguments since the Supreme Court decided Patterson

v. McLean Credit Union, 109 S. Ct. 2363, 105 L. Ed. 2d 132

(1989), as if it were impermissible for plaintiffs to argue that

their Complaint, drafted prior to the Supreme Court's decision,

states a section 1981 claim under standards announced in that

case. See Appellees' Brief at 8, 23, 34 n. 9, 40. Defendants'

implication that it is unfair or burdensome to litigate under new

legal theories after there has already been extensive discovery

and briefing prior to Patterson. see Appellees' Br. at 6, only

adds support to plaintiffs' position that Patterson should not be

applied retroactively to this case. See Appellant's Br. at 30-

33 .

If Patterson is to be applied here, it is plaintiffs'

prerogative to explain how the allegations of their Complaint are

adequate to withstand dismissal under the standards the Supreme

*

Court recently set out in Patterson. As the Supreme Court

explained in Chevron Oil Co. v. Huson. "[w]e should not indulge

in the fiction that the law now announced has always been the law

1

and, therefore, that those who did not avail themselves of it

waived their rights." 404 U.S. 97, 107 (1971) quoting Griffin v.

Illinois. 351 U.S. 12, 26 (1956).

Defendants also assert that plaintiffs "go beyond the

pleadings" in their description of the facts. Appellees' Br.

at 2. In the context of a motion to dismiss, and of de novo

review of the grant of such a motion, a court may appropriately

rely on allegations in a plaintiff's affidavit to supplement

facts formally pleaded in the complaint. See Eh_Federico Co.— v.s.

New Bedford Redevelopment Authority, 723 F.2d 122, 126 (1st Cir.

1983) (holding that there is no need formally to amend the

Complaint where there is no prejudice to the opposing party);

Johnson v. Mateer. 625 F.2d 240, 242 (9th Cir. 1980) (remanding

to allow plaintiff to amend under Rule 15(b) where factual

allegations were submitted in an affidavit to the district

court). Because defendants in this case have had adequate notice

of the affidavit allegations, and those allegations are

consistent with the Complaint, the Court of Appeals should not

affirm the dismissal merely because a formal amendment was not

made.1

1 Even cases defendants cited in their brief in support of

their argument that plaintiffs' Complaint is inadequate authorized

plaintiffs to replead on remand. See, e.g., Albert v.— Caravano,

851 F. 2d 561, 563 (2d Cir. 1988) (affirming dismissal of claims

without prejudice to plaintiff's right to amend complaint) ; Martin

v. New York State Pep't of Mental Hygiene, 588 F.2d 371, 372 (2d

Cir. 1978) (same).

2

II. THE COMPLAINT CLEARLY ALLEGES THAT PLAINTIFFS

CONTRACTED WITH TWO PAIRS OF DEFENDANTS AT

TWO DIFFERENT TIMES, AND EACH CONTRACT WAS

DISCRIMINATORY WHEN FORMED

Defendants argue that the October 21, 1983 addendum to the

Agency Agreement "cannot realistically be considered as the

'making' of a new contract," Appellees' Br. at 18, because it was

merely a "formal" or "technical" amendment, adding Home of

Indiana and City Insurance as "nominal parties." Id. at 18, 19,

22. See id. at 4. They appear to be contending that the second

two defendants were parties to the agency agreement from the

start, and that the addendum merely reconciled the written record

with the practical reality of the parties' contractual

relationship. Id. at 20, 21.

Defendants' assertions that a contractual relationship

between plaintiffs and all four defendants existed prior to

October 21, 1983 is entirely unsupported by the allegations of

the Complaint, and it is those allegations and the reasonable

inferences to be drawn therefrom which are alone relevant here.

Conlev v. Gibson. 355 U.S. 41 (1957). There are no allegations

that the second two defendants had any relationship with

plaintiffs prior to October 1983. Defendants' position that a

contract was formed with the second two defendants by practice

alone without a formal writing contradicts plaintiffs'

allegation, acknowledged by the district's court, that plaintiffs

entered into an agency agreement with the first two defendants on

December 28, 1982, and that the agreement was only later amended

to include the second two defendants. Complaint at paras. 14-15

3

(A4); 50 F.E.P. Cases at 1173 and n. 1. In the current

procedural posture on appeal from the dismissal of the Complaint

for failure to state a claim, defendants' contention must fail.2

Defendants mischaracterize plaintiffs' claims when they

assert that "Gonzalez has not alleged and cannot show that the

addendum was offered or formed in a racially discriminatory

manner." Appellees' Br. at 18. Defendants acknowledge, as they

must for purposes of this appeal, plaintiffs' allegations that

additional "conditions and restrictions" were placed on ATG

between December 1982 and October 1983. Id- at 20; see Complaint

paras. 21, 40, 41—N, 41—0, 41—P, 41—Q, 41—T (A5, A8, A10). They

view these restrictions as immaterial to the contract with the

second two defendants on the ground that the addendum merely

adopted the "standard Agency Agreement and contained no other

'terms' or 'provisions.'" Appellees' Br. at 18-19. The

additional conditions and restrictions, including the

requirements that plaintiffs produce an established quota of

premiums in a set period of time and that they solicit only

certain types of business, see Appellants' Br. at 5, were,

however, undeniably incorporated into the agreement with the

second two defendants. Indeed, it was precisely because the

plaintiffs ostensibly failed to fulfill these additional

2 Even if evidence of record were relevant at this stage,

the contract between plaintiffs and the second two defendants

explicitly states that it was "effective October 21, 1983."

Appellees' Br. at 19, n. 4. The parole evidence rule thus

precludes consideration of evidence directly to the contrary.

4

conditions that The Home of Indiana and City Insurance cancelled

their agency agreement with plaintiffs. See Complaint at para.

39; Appellees' Br. at 5.

With respect to the terms of the initial Agency Agreement

between plaintiffs and the first two defendants, defendants have

staked out the extreme position that if, at the time the contract

was formed, defendants intended to discriminate but did not so

state in the written Agency Agreement, the discrimination is not

actionable under section 1981. See Appellees' Br. at 23-25.

Thus, for example, if the intent of defendants Home Insurance and

Home Indemnity in December 1982 when they signed the Agency

Agreement was to require their Hispanic agents to bring in more

business and provide more documentation, to work under more

difficult conditions than white agents, or to behave in a more

deferential manner, defendants take the position that such

discrimination is beyond the scope of section 1981. When there

was discrimination from the outset in contract formation,

however, it violates section 1981 as construed in Patterson

regardless of whether the discriminatory terms were memorialized

in writing.3

3 Defendants are wrong when they describe the

discrimination as starting only 9 months after the formation of

the initial agency agreement. See Appellees' Br. at 14-15. Even

the district court characterized the Complaint as having alleged

that the discrimination began "almost immediately." 50 F.E.P.Cases

at 1173. Defendants also incorrectly assert that plaintiffs, in

their argument in support of amendment of the Complaint, have

identified no. new allegations that would support a section 1981

claim. Examples of such allegations are set forth in Appellants'

Br. at 16-17.

5

III. PLAINTIFFS' STANDING IS NOT BASED ON THE

RIGHTS OF THIRD PARTIES

The insurance companies argue that plaintiffs have no

•standing to challenge defendants' discriminatory refusal to enter

into insurance contracts made by plaintiffs as agents on the

ground that the discrimination is directed only at third parties.

Appellees' Br. at 26-34. Contrary to defendants' assertions,

however, plaintiffs have alleged that when defendants

discriminatorily rejected insurance contracts with plaintiffs'

clients, they violated plaintiffs' own rights under section 1981

in two respects. Plaintiffs claim violations of their rights (1)

to "make" insurance contracts between ATG's clients and the

defendant insurance companies, and (2) to enter into individual

unilateral contracts with the insurance companies for commissions

on each insurance policy the company issued to an ATG client.

Neither claim asserts or depends on the rights of third parties.

ATG made contracts and had a right under section 1981 not to

be discriminated against in so doing.4 This was plaintiffs'

4 The existence of this right depends on statutory

construction of section 1981, and not on appellants' status under

insurance law or agency principles; the right exists irrespective

of whether defendants are correct that an insurance agent would not

be a party to the individual insurance contracts the agent

arranged. See Appellees' Br. at 28-29.

It is immaterial to the construction of section 1981 whether

the statute by its plain language gives appellant more protection

than "other employees or agents simply because of the fortuity that

he arranges contracts." Appellees' Br. at 26. Appellants lack

rights under Title VII because they are not employees, regardless

of how anomalous that may seem. By the same token, persons such

as insurance agents, realtors, or wholesale buyers whose work

6

right, independent of the rights of ATG's clients and of the

defendant insurance companies to make contracts with one another

free from discrimination. See Appellants' Br. at 18-22. To the

extent that defendants contracted unequally with plaintiffs based

on assumptions about the race of their clients, see Appellants'

Br. at 21, this, too, was discrimination directly against

plaintiffs because the assumptions were based on plaintiffs'

race, not the race of their clients.

ATG also entered into unilateral contracts with the

insurance companies each time ATG brought in business which the

companies accepted. See Appellants' Br. at 22-23. These

contracts, which are distinct from both the Agency Agreement and

the individual insurance policies, were contracts to which only

plaintiffs and defendants were parties.. Thus> plaintiffs' right

to enter such contracts on a nondiscriminatory basis is their

own, and not the right of third parties.

Even if defendants' position that ATG does not have standing

to assert the section 1981 rights of its clients were relevant,

it is contrary to law. Plaintiffs do have standing to assert

their clients' rights. See Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 396

U.S. 229 (1969); DeMatteis v. Eastman Kodak, 511 F.2d 306, 312

(2d Cir. 1975) modified on other grounds, 520 F.2d 409 (2d Cir.

involves the making of contracts — whether on their own behalf or

for an employer or principal — are protected by the plain terms *

of section 1981 where others might not be.

7

1975) .5

IV. PATTERSON DOES NOT BAR SECTION 1981 CLAIMS OF

DISCRIMINATORY CONTRACT TERMINATION

Defendants concede that the question whether section 1981

extends to contract termination was not presented in Patterson

and that the Supreme Court accordingly did not decide it.

Appellees' Br. at 35, 37-38. Under the circumstances, this

Circuit should either follow its own established precedent that

section 1981 covers contract termination, see Lopez v._S.B.

Thomas. Inc.. 831 F.2d 1184, 1187-88 (2d Cir. 1987), or refrain

from deciding this appeal pending decision in Lytle. Defendants

5 Cases cited by defendants do not sustain the opposite

contention. Judge Haynesworth's view in Mackey v. Nationwide Ins.

Co.. 724 F.2d 419 (4th Cir. 1984), is founded on a misapprehension

of Sullivan. 396 U.S. 229. In his view, the white plaintiff in

Sullivan who challenged the defendant's refusal to assign a

property interest to a Black family had standing to sue only

because the Black purchasers would not themselves be in a position

to vindicate their own rights. Mackey, 724 F.2d at 422. In fact,

however, the Black purchasers were co-plaintiffs in Sullivan. 396

U.S. at 235. This and other Circuits have not read Sullivan as

barring white plaintiffs from challenging race discrimination where

Blacks also harmed by the discrimination themselves might be able

to sue.

Defendants' reliance on The Dartmouth Review v. Dartmouth

College. 1989 U.S. App. LEXIS 16928, *11 n. 3 (1st Cir., Nov. 9,

1989), is similarly misplaced. The First Circuit in that case

cited DeMatteis with approval, and dismissed the claims of the

white plaintiffs precisely because the plaintiffs had not asserted

that they or anyone else were harmed by race discrimination against

others (or against themselves), but had claimed that they were

persecuted because of their own racist views. Gersman v . Group

Health Ass'n. 1989 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 13449 (D.D.C. Nov. 13, 1989),

merely holds that emotional distress is an insufficient basis for

standing under section 1981. And the Tenth Circuit in Phelps_v̂ _

The Witchita Eagle-Beacon, 886 F.2d 1262, 1267 (10th Cir. 1989),

expressly reiected the lower court's holding that the plaintiff in

that case lacked standing, affirming only on the separate ground

that defamation is not actionable under section 1981.

8

are wrong that the contract-termination issue is not before the

Court in Lvtle. The first question presented in the respondent's

brief addresses whether section 1981 covers discriminatory

termination. Brief for Respondent, Lvtle v. Household

Manufacturing. Inc.. 88-334 (filed October 19, 1989), and the

petitioner also discusses the issue in his reply brief. Reply

Brief for Petitioner, at 17-23 (filed November 29, 1989).

(Relevant pages of each brief attached as addendum hereto).6

6 Regarding the merits of the termination claim, although

defendants characterize as "legally unsound" plaintiffs' contention

that termination of their at-will contract can equallybe described

as refusal to re-contract, at least one federal district court has

adopted that view. See Barkan v. Hilti. Civil Action No. 89-C-

318-E (N.D.Okla. October 12, 1989)(attached hereto).

9

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, and the reasons stated in the

original Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellants, the decision below

should be reversed and the case should be remanded to the

district court.

Respectfully submitted,

295 Madison Avenue/ f

New York, New York 10017

(212) 986-7468

HARRY C. KAUFMAN

274 White Plains Road

Eastchester, New York 10707

(914) 961-1755

CORNELIA T.L. PILLARD

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

Dated: New York, New York

December 22, 1989

10

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This will certify that I have this date served the

following counsel for Defendants-Appellees with true and correct

copies of the foregoing Reply Brief of Plaintiff-Appellants by

placing said copies in the U.S. Mail at New York, New York

postage thereon fully prepaid addressed as follows:

Lawrence 0. Kamin

Willkie, Farr & Gallagher

One Citicorp Center

153 East 53rd Street

New York, New York 10022

Mitchel H. Ochs

Willkie, Farr & Gallagher

One Citicorp Center

153 East 53rd Street

New York, New York 10022

Executed this

York.

In The

Satprrmr (£nurt uf th? llnilrii S’talrs

October T erm, 1989

No. 88-334

J ohn S. Lytle,

Petitioner,

v.

Schwitzer U.S. Inc .,

A Subsidiary of Schwitzer Inc .,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether Petitioner is precluded from maintaining a

cause of action for discriminatory termination and re

taliation under this Court’s holding in Patterson v. Mc

Lean Credit Union that 42 U.S.C. § 1981 does not en

compass conduct after the formation of an employment

contract?

2. WTas the Court of Appeals correct in applying collat

eral estoppel to Petitioner’s § 1981 claims after a full

and fair hearing was held on his Title VII claims, the

elements of which are identical to those under § 1981?

3. Does the Seventh Amendment require that Petitioner

receive a new jury trial on his § 1981 claims when he

failed to establish a prima facie case of discrimination

during the trial of his Title VII claims?

(i)

nied, 320 U.S. 214 (1943U Similarly, when a directed

verdict is appropriate, the erroneous denial of a jury trial

constitutes harmless error. Laskaias i\ Tnomburfj, 73o

F.2d 260 C 3d C i r . cert, denied, 469 U.S. 886 11984 >.

Here, the district court dismissed Lytle’s Title VII dis

charge claim at the conclusion of Lytle’s evidence, ruling,

as a "matter of law. that Lytle had not established the ele

ments of a prima facie case. The court made a similar

ruling regarding the retaliation claim at the conclusion

of all the evidence. Thus, Petitioner’s evidence would not

have withstood a motion for a directed verdict and, as a

consequence, any error regarding denial of a jury trial

would ha've to be deemed harmless error.

ARGUMENT

I. THE FOURTH CIRCUIT’S JUDGMENT SHOULD BE

AFFIRMED ON THE BASTS OF THIS COURT’S DE

CISION IN PATTERSON v. McLEAN CREDIT

UNION

Petitioner contends that the Fourth Circuit’s decision

improperly deprived him of his Seventh Amendment right

to a jury trial on his 5 1981 claims for discriminatory

discharge and retaliation. However, the Court’s recent

decision in Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, ----- U.S.

___ , 105 L. Ed. 2d 132 (1989). makes clear that § 1981

does not provide a cause of action for discriminatory dis

charge, or for retaliation in response to protected activi

ties. Accordingly, this Court should affirm the Fourth

Circuit’s judgment on the basis of Patterson or, alterna

tively. dismiss the writ of certiorari as improvidently

granted. See Picc'rillo v. New York, 400 U.S. 548, 548-

59 '1971) i writ dismissed as improvidently granted be

cause intervening court decision meant that constitutional

question on which Court granted certiorari was no longer

necessary to resolution of the case).

Initially, it is well settled that Schwitzer, as the pre

vailing party below, may defend the appellate court’s

11

12

judgment on any ground raised in the courts below,

whether or not that ground was relied upon, rejected or

even considered by the lower courts. E.g., Washington v.

Yakima Indian Nation, 439 U.S. 463, 476 n. 20 (1979) ;

United States v. New York Telephone Co., 434 U.S. 159,

166 n. 8 (1977) (“prevailing party may defend a judg

ment on any ground which the law and the record per

mit. . . .” ). Indeed, a respondent or appellee before this

Court may even defend a judgment on grounds not previ

ously urged in the lower courts,9 and this is especially

appropriate where, as here, an intervening decision by

this Court has changed controlling law. See Sure-Tan,

Inc. v. NLRB, 467 U.S. 883, 896 n. 7 (1984) (permitting

a petitioner, who is normally limited to issues presented

in the petition for certiorari, to raise issue for first time

before this Court because bf intervening change in con

trolling law). Finally, it is particularly appropriate for

the Court to consider alternative statutory grounds for

affirmance where, as here, the Petitioner has posed a con

stitutional challenge to the decision below. See Jean 'v.

Nelson, 472 U.S. 846. 854 (1985), quoting Spector Motor

Co. v. McLaughlin, 323 U.S. 101, 105 (1944) (federal

courts must consider statutory grounds for judgment be

fore reaching any constitutional questions because “ [i]f

there is one doctrine more deeply rooted than any other

. . ., it is that we ought not to pass on questions of con-

stitutionalitv . . . unless such adjudication is unavoid

able” ).

In short, both this Court’s precedents and the posture

of this case suggest very strongly that the Court should

dispose of the instant case on the Patterson issues rather

9 Schu-eiker v. Hogan. 457 U.S. 569, 585 & n. 24 >1982), quoting

Blum v. Ba-con. 457 U.S. 132. 137 n. 5 (1982) (“Although appellees

did not advance this argument in the District Court, they are not

precluded from asserting it as a basis on which to affirm the court’s

judgment . . . [because it': ‘is well accepted that . . . an appellee

may rely upon any matter appearing in the record in support of

the judgment.’ ”).

13

than the Seventh Amendment issues raised by Petitioner.

Here, Schwitzer has asserted from the outset that Peti

tioner could not maintain causes of action for termina

tion and retaliation under § 1981 i’J.A. 44, 51-56). Pat

terson provides significant new guidance on that question,

and it presents purely legal, non-constitutional issues that

can be decided on the instant record with no prejudice to

the parties. Accordingly, we turn now to a discussion

of how Patterson impacts this case and requires affirm

ance of the Fourth Circuit’s judgment.10

The relevant portion of § 19S1 under scrutiny in Pat

terson provides that “ [a] 11 persons within the jurisdic

tion of the United States shall have the same right in

every State and Territory to make and enforce contracts

. . . as is enjoyed by white citizens. . . .” 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

The Patterson Court emphasized that, contrary to the

trend in lower court cases, § 1981 “cannot be construed

as a general proscription of racial discrimination in all

aspects of contract relations.” Patterson, 105 L. Ed. 2d at

150. Rather, the Court held that the right “to make”

contracts “extends only to the formation of a contract,”

that is, “the refusal to enter into a contract with some

one, as well as the offer to make a contract only on dis

criminatory terms.” Id. Thus, the Court refused to ex-

10 The Patterson decision applies retroactively. See, e g., Morgan

v. Kansas City Area Transportation Authority, ------ F. Sapp. ------

(W.D. Mo. 1989) [1989 Westlaw 101802]; Leong v. Hilton Hotels,

Inc., ------ F. Supp. ------ . 50 FEP Cases 733 (D. Hawaii 1989).

The majority of courts faced with this issue have implicitly found

that the decision should be applied retroactively. See, e.g., Overby

v. Chevron U.S.A., Inc., 384 F.2d 470 (9th Cir. 1989) ; Brooms v.

Regal Tube Co., 381 F.2d 412 (7th Cir. 1989). But see Gillespie

v. First Interstate Bank of Wisconsin Southeast, 717 F. Supp. 649

(E.D. Wise. 1989). Retroactive application of judicial decisions is

the rule, not the exception. United States v. Givens, 767 F.2d 574,

578 (9th Cir.), cert, denied. 474 U.3. 953 (1985). In addition,

“ [t]he usual rule is that federal cases should be decided in accord

ance with the law at the time of decision.” Goodman v. Lakens

Steel Co., 482 U.S. 656, 662 (1987).

.3 .P II- j 1 mm*. T

■ -V .

14

tend this aspect of § 1981’s coverage to discriminatory

conduct occurring after the formation of a contract:

[T]he right to make contracts does not extend, as a

matter of either logic or semantics, to conduct by

the employer after the contract relationship has been

established, including breach of the terms of the con

tract or imposition of discriminatory working condi

tions. Such post-formation conduct does not involve

the right to make a contract, but rather implicates

the performance of established contract obligations

and the conditions of continuing employment. . . .

105 L. Ed. 2d at 150-51. See also 105 L. Ed. 2d at 152,

155. Consistent with this rationale, the Court held that

Patterson’s claim of pervasive workplace racial harass

ment involved only post-formation conduct which was not

cognizable under § 1981.11

The Court gave a similarly restrictive reading to the

second relevant aspect of § 1981. The Court held that

the right “to enforce” contracts established in § 1981

“embraces protection of a legal process, and of a right

to access to legal process, that will address and resolve

contract-law claims without regard to race.” 105 L. Ed. 2d

at 151. While this protection may extend to private

race-based efforts to impede access to contract relief.r- 11 12

11 The Court recognized that § 19S1 may cover port-formation

conduct in those limited situations where the conduct denies an

employee the right to “make” a new employment contract with the

employer. For example, a race-based refusal to promote may or may

not be actionable under § 1981. depending upon whether the nature

of the change in position is such that it would involve entering into

a new contract with the employer. 105 L. Ed. 2d at 156. “Only

where the promotion rises to the level of an opportunity for a new

and distinct relationship between the employee and the employer is

such a claim actionable under § 1981.” Id.

12 The Court cited the example of a labor union which bears ex

plicit responsibility for prosecuting employee contract grievances

and which carries out that responsibility in a racially discrimina-

15

the right “does not . . . extend beyond conduct by an

employer which impairs an employee’s ability to enforce

through legal process his or her established contract

rights.” Id.

Aside from the fact that these constructions comport

with the “plain and common sense meaning” of § 1981’s

statutory' language 1105 L. Ed. 2d at 156 n. 6), the

Patterson Court also recognized that strong policy con

siderations support such limited constructions. 105 L.

Ed. 2d at 152-53. An employee who suffers post-forma

tion discrimination may seek relief under the adminis

trative procedures provided in Title VII. In that statute,

Congress established an elaborate administrative pro

cedure designed to assist in the investigation of discrim

ination claims and to work towards the resolution of

these claims through conciliation rather than litigation.

See 42 U.S.C. > 2000e-5ibi. Only after these procedures

have been exhausted may a plaintiff bring a Title VII .

action- in court. See 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-51 f ) f 1 ). Thus,

permitting an emplovee to pursue a parallel claim under

§ 1981 without resort to the statutory prerequisites would

“undermine the detailed and well-crafted procedures for

conciliation and resolution of Title VII claims,” render

ing such procedures “a dead letter.” Patterson, 105

L. Ed. 2d at 153.

Applying the Patterson standards to the instant case,

it is clear that the Petitioner has no viable claims under

§ 1981. Petitioner does not contend that Respondent

prevented him from entering into or enforcing a con

tract because of his race. Instead, he contends that Re

spondent discriminatorily discharged him and then re

taliated against him for filing a charge with the EEOC.

Petitioner’s right under § 1981 to make or enforce a con

tract on a race-neutral basis is therefore not implicated.

tory manner. 105 L. Ed. 2d at 151, citing Goodman v. Lu.kens Steel

Co., supra..

16

First, a discharge is, by definition, post-formation con

duct which does not involve an employee s right to make

or enforce a contract. Such conduct, therefore, falls out

side the purview of § 1981. See Leong v. Hilton Hotels

Corp supra; Copperidge v. Terminal Freight Handling

Co., -__ F. Supp. ------- 50 FEP Cases 812 (W.D. Tenn.

19891 ; Sofferin v. American Airlines, Inc., 717 F. Supp.

587 (N.D. 111. 1989) ; Hall v. County of Cook, State of

Illinois,----- F. Supp.------- (N.D. 111. 1989) [1989 West-

law 99802] ; Greggs v. Hillman Distributing Co., -----

F. Supp. ----- . 50 FEP Cases 1173 (S.D.N.Y. 1989).

But see Padilla v. United Air Lines, 716 F. Supp. 485

(D. Colo. 1989).13

Second, Petitioner’s discharge claim is, at bottom, noth

ing more than an assertion that he was punished more

severely for absenteeism than were similarly situated

white employees. See Pet. Br. at 8-12. This is pre

cisely the type of conduct the Patterson dissent argued

should be covered by 5 1981. See 105 L. Ed. 2d at 170

(stating that § 1981 was intended to prohibit the prac

tice of handing out severe and unequal punishment for

perceived transgressions” ). However, the Patterson ma

jority clearly rejected the dissent’s position that such

discriminatory rule application is sufficient to state a

claim under § 1981. 105 L. Ed. 2d at 155. While rec

ognizing that such post-formation discrimination might

be evidence that any divergence in explicit contract

terms is due to racial animus, the majority nevertheless

emphasized that the “critical . . . question under § 1981

remains whether the employer, at the time of the forma

tion of the contract, in fact intentionally refused to

13 This district court decision upholding- discharge claims under

§ 1981 demonstrates that the lower courts have not. in fact, had

"little difficulty applying the straightforward principles that (the

Court announced in Patterson}." Patterson. 105 L. Ed. 2d at 156

n. 6. This provides an additional reason why the Court should take

this opportunity to reiterate the reach of § 1981 and the Patterson

decision.

17

enter into a contract with the employee on racially neu

tral terms. ’ Id. (emphasis in original).

Finally, Petitioner does not and cannot contend that

his discharge was a race-based effort to obstruct his

access to the courts or other dispute resolution processes,

indeed, his discharge had nothing to do with any effort

to enforce contract rights or claims.

In short, the Petitioner’s discharge claim in the instant

case involves post-formation conduct unrelated to his right

to make or enforce a contract, and hence it is not coe-

nizable under § 1981.

Petitioner’s retaliation claim is even farther afield

from § 1981 coverage. First, like Petitioner’s discharge

claim, the retaliation claim involves only post-formation

conduct and therefore is not actionable under § 1981.

Overby v. Chevron U.S.A., Inc., supra; Williams v. Na

tional Railroad-Passenger Carp.. 716 F. Supp. 49 iDDC

1989) ;•Danger-field v. Mission Press, ___ F Supp ___ '

50 FEP Cases 1171 (N.D. 111. 1989)

Second, the prohibition of retaliation against employees

or filing discrimination charges is purely a creature of

statute, having come into existence only by an express

prohibition in Section 704(a) of Title VII, 42 U SC

§ 2000e-3 (a) . Indeed, the prohibition specifically relates

only to the exercise of rights conferred by Title VII.

Not only did the right to be free from such retaliation

not exist before the passage of Title VII, see Great Amer

ican Savings & Loan Association v. Novotny 442 U S

366. 377-78 (1979 ). but it would be inappropriate 'to

inject rights created by one statute into another statute

passed approximately 100 years earlier. See Warren v.

Halstead Industries, ----- - F. Supp. ----- .33 FEP Ca<;ps

1416 0I.D.N.C. 1983, (questioning whether a caule

of action created by Title VII is actionable under § 1981).

See also Saldivar v. Cadena, 622 F. Supp. 949 (WD

18

Wise. 1985) (retaliation for advocacy of equal protec

tion does not support a § 1981 claim i .

Moreover, this conclusion is particularly appropriate

given the Patterson Court’s admonition against stretch-

s 1981 to protect conduct already covere

V III ^Patterson, 105 L. Ed. 2d at 153 The Court s con-

cen t'w ith frustrating Title V II’s c o n d it io n goals, to -

oussed above, “is particularly apt where the very con

duct complained of centers around one of Title VII s con-

“ procedures, the filing of an EEOC complamt^

Overbv v Chevron U.S.A. Inc., 884 F—d »

FEP Cases at 1213. Since 5 704(a) of Title y n Pro

scribes Respondent’s alleged retaliatory- conduct, the Court

fhouU “d'edine to twist the interpretation of another

statute (§ 1981) to cover the same conduct. lOo L. Ed.

2d at 153.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, retaliation for

filincr Title VII charges is not even a race-based issue, filing Title v u cnai0« 8 eoveraee The anti-wViifh is the sine qua non of > lyo-i co%erag

retaliation provisions of Title VII are designed to pro-

tect channels of information, not freedom from race-

based conduct, and they are equally availab.e to em-

,• -4? fVipiy rac° 5ex. national orurm.

of Title VII “extends protection to all who a -

‘participate’ regardless of their race or sex. k Thu-. P

quite simply, a claim of retaliation for filing Tire VI

charges has nothing to do with an employee » >,19S1 ™

to make and enforce contracts

citizens Indeed, even before this Lomt.

c ion manv lower courts had held that discrimination

S o n factors other than race, such as retaliation in

violation of S 704fat of Title VU does not violate^ 1981.

See eg., Hudson v. IBM. ----- F. -upp. •

J i; d NY 1975'; Takcall v. T7 ERD. Inc.,

^ % 9 Supp _ , 2 3 FEP Cases 947 <M.D. Fla. 1979 - ;

o

Grant v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., ----- F. Supp. ----- , 22

FEP Cases 6S0 iS.D.N.Y. 1978); Barfield v. A.R.C. Se-

curity, Inc., ----- F. Supp. ----- , 10 FEP Cases 739

iN.D. Ga. 19751.14 The correctness of that conclusion

has only been confirmed by Patterson’s mandate that

< 1981 be interpreted in accordance with the plain and

common sense meaning of its terms and that courts

should avoid “twist [ing] the interpretation of [§ 1981]

to cover the same conduct” covered by Title VII. 105

L. Ed. 2d at 153.

In sum. while both of Petitioner's claims are cogniza

ble under Title VII. and indeed have been given full

consideration under that statute, neither is cognizable

under § 1981. Accordingly, this Court should either af

firm the Fourth Circuit’s judgment on the basis of

Patterson or dismiss the writ of certiorari as improv-

idently granted.

II THE SEVENTH AMENDMENT DOES NOT RE

QUIRE RETRIAL OF ISSUES ALREADY DECIDED

BY THE DISTRICT COURT

The preceding section demonstrates that the funda

mental predicate of Petitioner’s Seventh Amendment ar

gument no longer exists. Specifically, the collateral es

toppel and jury trial issues arose in the Fourth Cir

cuit only because the court assumed that the district

court had erroneously dismissed Petitioner’s § 1981

claims. If dismissal was proper—and the foregoing sec

tion shows it was—then no new trial is necessary and,

a fortiori, the question of whether collateral estoppel is

applicable does not arise. As a consequence, the Court

need not reach the collateral estoppel Seventh Amend-

14 Although there are cases to the contrary (e.g., Goff v. Conti

nental Oil Co.. 678 F.2d 693 (5th Cir. 1982)), they are not in keeping

with the .statutory intent of 5 1981 to prohibit employment deci

sions based on race, rather than post-discharge actions allegedly

based on participation in statutory proceedings under Title VII.

19

No. 88-334

In The

Supreme Court of tf)t ^HnitEb states

October Te r m , 1989

John S. Lytle

v.

Petitioner,

Household Manufacturing, Inc.,

d/b/a Schwitzer Turbochargers,

Respondent.

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Julius LeVonne Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

Ronald L. E llis

E ric Schnapper

Judith Reed*

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Penda D. Hair

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Pamela S. Karlan

University of Virginia

School of Law

Charlottesville, VA 22901

(804) 924-7810

Attorneys for Petitioner

* Counsel of Record

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS. WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

CONTENTS

I. The Seventh Amendment Compels Reversal of

the Court of Appeals’ Judgment ................... 1 II.

II. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Does Not

Preclude Petitioner From Maintaining This

Action . . .......................................................... 10

is of constitutional dimension, it is an issue the Court

need not reach in order to resolve the jury trial question

in our favor.

(1) Discriminatory Discharge. Respondent urges

this Court to hold that all discriminatory discharges are

not actionable under section 1981. If the application of

section 1981 to claims of this sort necessarily gave rise to

a simple rule, either including or excluding all cases that

might be characterized as "discharges," this might be an

issue that could appropriately be resolved at this

juncture. But because of the widely differing events that

may occur when an employee loses his or her job, the 15

15(...continued)

Tennessee Valiev Authority. 297 U.S. 288, 346-48 (1936)(Brandeis, J.,

dissenting). In the instant case the constitutional issue has already

been resolved, and repeatedly so, in petitioner’s favor (P. Br. 34-41),

and involves not a potential conflict with a co-equal branch of

government, but this Court’s special responsibility to supervise

compliance with the Seventh Amendment by the lower federal courts.

On the other hand, the complex statutory questions raised by

respondent regarding the meaning of Patterson are entirely novel,

having their origins in a decision less than six months old.

17

application of Patterson and section 1981 to discharges,

like their application to promotions, is complex and fact-

specific.

The mere announcement that an employee is fired

may by itself do no more than terminate a contractual

relationship; if that were all that occurred when a

particular employee was dismissed, such an event might

arguably constitute pure post-formation conduct.16 * But

what actually occurs in a discharge case may in fact be

more complex. Having been formally dismissed, the

16 Several post-Patterson cases hold that all racially motivated

discharges are actionable under section 1981. See, e.g., Birdwhistle

v. Kansas Power and Light Co., 51 FEP Cases 138 (D. Kan. 1989);

Booth v. Terminix International. 1989 U.S.Dist. LEXIS 10618 (D. Kan.

1989). At least where the discharged worker was an "at will"

employee, this conclusion seems consistent with Patterson, since at-

will employment is commonly regarded as "hiring at will". Corbin on

Contracts, § 70 (1952); Martin v. New York Life Ins. Co., 148 N.Y.

117, 42 N.E. 416,417 (1895). An employer who fires an at-will

employee is not terminating an existing contract, but refusing to

make new additional unilateral contracts. Since, however, at least

some discharges of at-will or other employees .are undeniably still

actionable after Patterson, and the instant complaint thus cannot be

dismissed at this juncture, it is not necessary to decide whether all

discharges are still actionable.

18

potential plaintiff, technically already an ex-employee, at

times seeks to get back his or her job, or, perhaps, some

other position at the firm.17 That a dismissed employee

might immediately seek that old job, or some other

position, is hardly surprising; "the victims of

discrimination want jobs, not lawsuits." Ford Motor Co.

v. EEOC. 458 U.S. 219, 231 (1982).18 Since the

announcement of the dismissal, as respondent itself

argues, ends the old contractual relationship, an ex

employee’s renewed efforts to work at the firm constitute

an attempt to make a new contract. If an employer

spurns these overtures of a newly dismissed employee

because he or she is black, that discriminatory act would

17 See, e.g., Jones v. Pepsi-Cola General Bottlers, 1989

U.S.Dist. LEXIS 10307 (W.D.Mo. 1989)(discharge claim actionable

under section 1981 because the employee, after being told he was

fired, "requested a different job, offering to sweep floors if necessary,

to stay employed. Defendant refused.").

18 Indeed, petitioner sought reinstatement herein. Joint

Appendix (JA) 13, par 3.

19

quite literally be a "refusal to enter into a contract1

within the very terms of Patterson.19 That would

obviously be so in the case of a dismissed worker who

applied a year later for employment, as occurred in

McDonnell Douglas v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1978).

There is no principled basis for treating differently a

dismissed employee who seeks reinstatement, or a new

position, a day, an hour, or a minute after his or her

dismissal. On four occasions prior to Patterson this

Court held actionable under section 1981 the discharge of

a former employee; in each case the employee, after

19 Padilla v. United Air Lines. 716 F. Supp. 485, 490 n. 4 (D.

Colo. 1989)("Defendant’s refusal to reconsider plaintiff for rehire due

to discriminatory practices is clearly prohibited by § 1981"); Jones

v. Pepsi-Cola General Bottlers, 1989 U.S.Dist. LEXIS 10307

(W.D.Mo. 1989)("in refusing on the basis of race to make a new

contract [with the dismissed worker], defendant violated section

1981").

20

having been told of the dismissal decision, had taken

steps to induce the employer to restore him to his job.20

Section 1981 would also be applicable to the

termination decision itself if the employer, for racial

reasons, fired a black employee for misconduct for which

white employees were or would have been disciplined in

a less harsh manner. Such discriminatory disciplinary

practices would violate the last clause of section 1981, a

provision not at issue in Patterson, which requires that

blacks "shall be subject to like punishment . . . and to no

other" as whites. The equal punishment clause, on the

other hand, would have no application to an employer

who, with no pretense of disciplinary motive, selected

employees for discharge on the basis of race.

20 McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co., 427 U.S.

273, 275 (1976)(grievance); Delaware State College v. Ricks, 449

U.S. 250, 252 (1980)(appeal of termination decision); St. Francis

College v. Al-Khazraii. 481 U.S. 604, 606 (1987)(appeal of

termination decision); Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S. 656,

664 (1987)(grievance).

21

The complaint in this case, filed almost five years

before Patterson, understandably does not address

specifically all of the additional subsidiary facts that may

be relevant, or even critical, after Patterson. The

complaint does allege that respondent, prior to dismissing

petitioner for an alleged violation of company rules, had

chosen not to discharge whites "who have committed

more serious violations of the company’s rules" than had

petitioner. JA 8, par. 15. This claim clearly falls within

the equal punishment clause of section 1981. The

complaint does not indicate, on the other hand, what

petitioner may have said to company officials after the

initial notice to petitioner that he had been dismissed;

affidavits submitted by respondent indicate that there

were at least two subsequent meetings between those

officials and petitioner before petitioner finally left the

22

plant.21 Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

petitioner was not required in his 1984 complaint "to set

forth specific facts to support [his] allegations of

discrimination," or to anticipate any additional

requirements that might follow from this Court’s 1989

decision in Patterson. Conlev v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41, 47-

48 (1957).

(2) Retaliation. Respondent urges this Court to

hold that no form of retaliation is ever prohibited by

section 1981, arguing that all retaliation constitutes post

formation conduct. (P. Br. 17-19). The application of

section 1981 to retaliation claims raises a large number

of different legal issues, because of the wide variety of

circumstances in which some form of race related

21 Petitioner testified that while he was operating his machine

Larry Miller told him of the termination. Tr. 143. Subsequently

petitioner apparently met both with A1 Duquenne, the production

superintendent, and then with the Employee Relations Department.

Affidavit of A1 Duquenne, p. 3.

23

C S : 0 I SB. S D3Q0C * 30Ud l I

C r

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF OKLAHOMA •

F I L E D

OCT 12 1939 C $

RITA G. BARKAN, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

Jack C Silver, Gerk

U.S. DISTRICT COURT

v s . No. 89-C-318-e y

HILTI, INC.,

Defendant

O R D E R

This case is before the Court on three matters. First,

Defendant, Hilti, Inc., appeals from the Magistrate's order denying

a discovery stay during the pendency of the motion to dismiss.

Second, Hilti moves to dismiss Plaintiffs' complaint on the grounds

that the recent decision of the Supreme Court in Patterson— v̂ _

McLean Credit Union, ______ U.S. ------ , 109 S.Ct. 2363 (1989)

eliminates Plaintiffs' claims for relief under 42 U.S.C. §1981.

Third, Plaintiffs move to dismiss Hilti's counterclaims. These

matters will be addressed in turn.

■ The-'Magistrate ' s~ O-rder- Denying—a- Stay of Discovery—

Title 28 U.S.C. §636 (1982) of the Federal Magistrate's Act

provides that the Court may designate a Magistrate to hear and

determine certain pretrial matters and in particular certain

discovery matters such as the one now before the Court.

Reconsideration of a Magistrate's order is, however, specifically

limited. 28 U.S.C. § 636 (b) (1) (A) reads, •'... A judge of the court

may reconsider any pretrial matter under this subparagraph (A)

0 0 0 • 3 9 b d I I t’S : C 1 66. S 0 3Q

( (

where it has been shown that the Magistrate's order is clearly

erroneous or contrary to law."

A stay of discovery is not ordinarily warranted even during

the pendency of dispositive notions, and it is a natter of

discretion whether to impose a stay. The Court finds in this case

that Defendant has not met its burden to show that the Magistrate's

decision to deny a stay was clearly erroneous or contrary to law.

pefendant's Motion to Dismiss $1931 Claims

The Court is satisfied that the Patterson decision does not

eliminate Plaintiffs' claims under 42 U.S.C. §1981. The Supreme

Court held in Patterson that an employee's claim for racial

harassment is beyond the scope of §1981. The employee in Patterson

had an additional claim, however, that her employer violated §1981

in failing to promote her. With regard to this claim the Court

stated:

the question whether a promotion claim is

actionable under §19 81 depends upon whether the

nature of the change in position was such that

it involved the opportunity to enter into a new

contract with the employer.

____ U.S. at ___ , 109 S.Ct. at 2377. This language is instructive

in understanding the extent to which Patterson circumscribes

§1981's application in the workplace. In this case Plaintiffs were

at-will employees of Hilti. An at-will employee's contract is

entered anew each day between the employee and the employer, c . f.,

Hinson v. Cameron. 742 P.2d 549 (Okla. 1987). It can be said,

therefore, that the employee's discharge is a refusal by the

employer to enter an employment contract with the employee. If the

2

F£ : £ I 5 8 . S. .3.3CL

employer's refusal is racially motivated, then it is actionable

under §1981. .An action pursuant to §1981 in such circumstances is

completely consistent with the supreme Court's analysis of §1981's

scope in Patterson. If Hilti's discharge of these at-will

employees was racially motivated they may maintain an action under

§1981. Hilti's motion to dismiss is accordingly overruled.

Plaintiffs' Motion to Dismiss Counterclaims for Defamation

And Tortious Interference with Business Relationships

, The- only-specific, -clearly - articulated statements Hilti

alleges to be defamatory are those made in the Plaintiffs'

Complaint. As such, they are privileged statements under

Okla.Stat.tit. 12 §1443.1 (West Supp. 1989) which . protects

statements and expressions of opinion made in connection with

judicial proceedings. They are not statements that can be made

the subject of a defamation claim. See. Joplin _v. .Southwestern

Bell Telephone Co.. 753 F.2d 803 (10th Cir. 1983); White_v^

Basnett. 700 P.2d 666 (Okla.App. 1985). Hilti has not articulated

any other statements allegedly made by any of the Plaintiffs

outside of this action. Hilti's counterclaim for defamation is

therefore overruled.

F O O ' 38Ud 1 I

Plaintiffs' allegations in connection with this action

likewise do not form the basis for an actionable tort for

intentional interference with business or contractual

relationships.

The Plaintiffs' motions to dismiss these counterclaims are

sustained.

3

i

£ £ : £ ! 6 8 , 5 33Q

(

IT IS THEREFORE ORDERED that the motion of Defendant Hilti to

dismiss is overruled;

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that the Magistrate's discovery order

of June 27, 1989 is affirmed; and

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that the motions of Plaintiffs to

dismiss Hilti's counterclaims are sustained.

ORDERED this Hz. day of October, 1989.

£ 0 0 ' 3E'bd i i

f

. j •• ■

JLiC etJe-ttm

JAMES tf. ELLISON

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

4