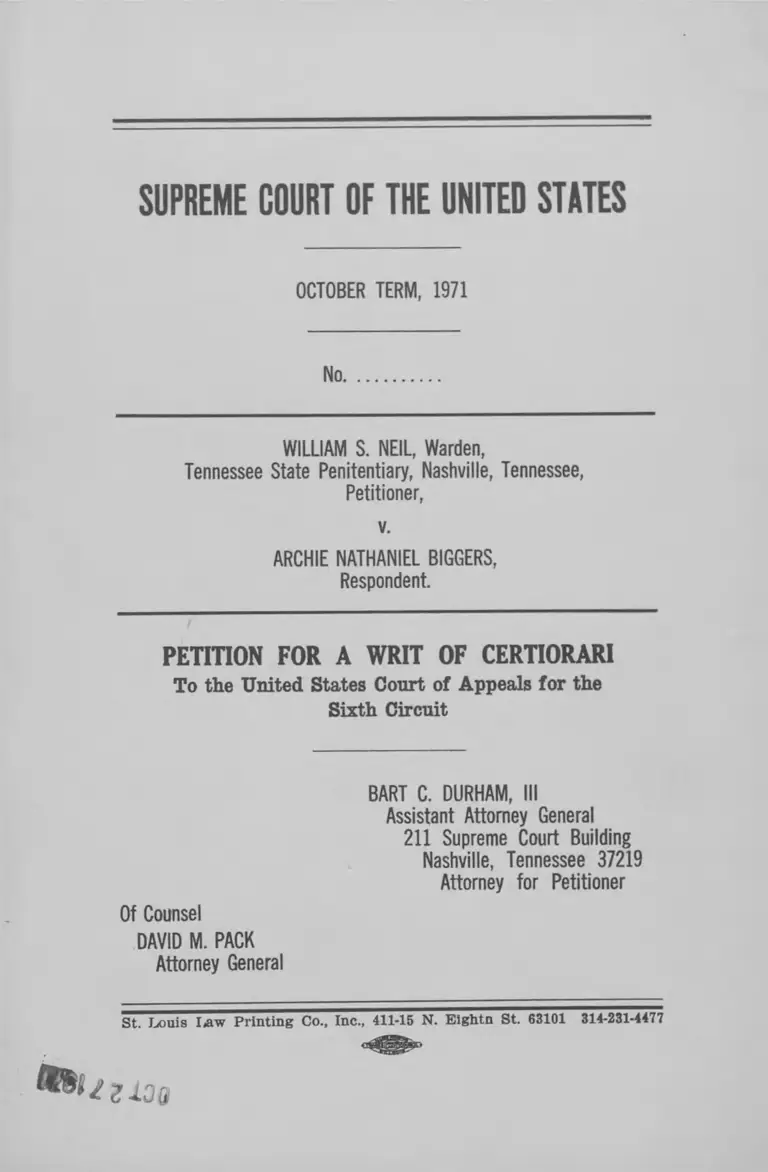

Neil v. Biggers Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

Public Court Documents

October 27, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Neil v. Biggers Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, 1971. 05ddb552-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f2851854-bbcd-467d-9727-ba6dbaf042f5/neil-v-biggers-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-sixth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1971

No.

WILLIAM S. NEIL, Warden,

Tennessee State Penitentiary, Nashville, Tennessee,

Petitioner,

v.

ARCHIE NATHANIEL BIGGERS,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

To the United States Court of Appeals for the

Sixth Circuit

Of Counsel

DAVID M. PACK

Attorney General

BART C. DURHAM, III

Assistant Attorney General

211 Supreme Court Building

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

Attorney for Petitioner

St. Liouis I jaw Printing Co., Inc., 411-15 N. Eightn St. 63101 314-231-4477

Z - L Q t

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Opinions below .................................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ............................................................ 2

Questions Presented ........................................................ 2

Constitutional, Statutory and Rules Provisions In

volved .................................................................. 2

Statement of the Case ...................................................... 5

Reasons for Granting the Writ:

1. A 4-4 affirmance by this Court of a State’s high

est court is res judicata as to the same issue be

tween the same parties in a future habeas corpus

action .............................................................. 0

2. The resolution on the merits of the alleged un

constitutional identification is inconsistent with

previous decisions of this C ou rt............................ 9

Conclusion ...................................................................... g

INDEX TO APPENDICES

Appendix

A. Biggers v. Neil, Warden, No. 20,540 (6th Cir.

1971) (opinion) ...................................................... A -l

B. Biggers v. Neil, Warden, Civil No. 5120 (M. D.

Tenn., May 4, 1970) (Order) ..............................A-39

C. Biggers v. Neil, Warden, Civil No. 5120 (M. D.

Tenn., April 17, 1970) (Order) ..............................A-46

11

D. Biggers v. Russell (Neil), Warden, Civil No.

5120 (M. D. Tenn., July 29, 1969) (Order) ........A-57

E. Biggers v. Russell (Neil), Warden, Civil No.

5120 (M. D. Tenn., May 12, 1969) (Order) ........A-58

F. Biggers v. Tennessee, 390 U.S. 1037 (1968)

(Order denying petition to rehear) ........................ A-60

G. Biggers v. Tennessee, 390 U.S. 404 (1968) ........A-61

H. Biggers v. Tennessee, 388 U.S. 909 (1967) ........A-67

I. Biggers v. State, 219 Tenn. 553, 411 S.W.2d 696

(1967) ........................................................................ A -68

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Anderson v. Johnson, Warden, 390 U.S. 456 (1968).. 8, 9

Biggers v. Tennessee, 390 U.S. 404 (1968) .................. 8

Coleman v. Alabama, 399 U.S. 1 (1970) ..................... 9

Durant v. Essex Company, 74 U.S. (7 Wall.) 107

(1868) .............................................................................. 8

Etting v. United States Bank, 24 U.S. (11 Wheat.) 59

(1826) .............................................................................. 8

Foster v. California, 394 U.S. 440 (1968) ..................... 9

Hertz v. Woodman, 218 U.S. 205 (1909) ..................... 8

Radich, Appellant v. New York, 401 U.S. 531 (1971) 8

Sanders v. United States, 373 U.S. 1 (1963) .............. 8

Stovall v. Denno, 388 U.S. 293 (1967) ......................... 9

United States v. Pink, 315 U.S. 203 (1941) .................... 8

Ill

Statutes

28 U.S.C., §1254(1) ....................................................... 2

28 U.S.C., §2241 ............................................................. 3

28 U.S.C., §2244 ............................................................. 3>6

28 U.S.C., §2403 ............................................................. 4>6

Constitution of the United States:

Fifth Amendment ...................................................... 2

Fourteenth Amendment ............................................... 2

Supreme Court Rules

Rule 23 ................................................................................ 4 7

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1971

No.

WILLIAM S. NEIL, Warden,

Tennessee State Penitentiary, Nashville, Tennessee,

Petitioner,

v.

ARCHIE NATHANIEL BIGGERS,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

To the United States Court of Appeals for the

Sixth Circuit

The petitioner William S. Neil, Warden, Tennessee

State Penitentiary, respectfully prays that a writ of cer

tiorari issue to review the judgment and opinion of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

entered in this proceeding on August 18, 1971.

OPINIONS BELOW

Mr. Biggers’ rape conviction was affirmed by the Ten

nessee Supreme Court, 219 Tenn. 553, 411 S.W.2d 696

(1967)(App. I). This Court granted certiorari, 388 U.S.

909 (1967) (App. H), affirmed the judgment below by an

equally divided vote, 390 U.S. 404 (1968) (App. G), and

— 2 —

denied a petition to rehear. 390 U.S. 1037 (1968) (App.

F). The United States District Court for the Middle Dis

trict of Tennessee granted a petition for writ of habeas

corpus in unreported orders (Apps. B-E) and the Sixth

Circuit affirmed in an opinion not yet reported (App. A).

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit was entered on August 18, 1971, and this petition

for certiorari is timely filed within ninety days of that

date. This Court’s jurisdiction is invoked under 28

U.S.C., § 1254(1).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. What effect did this Court’s equally divided affirm

ance of a state conviction after plenary consideration

have upon subsequent District Court reconsideration, by

collateral review in federal habeas corpus, of what Pe

titioner contends to be the identical issue presented to this

Court?

2. Was Respondent denied a fair trial as a result of the

use of identification evidence allegedly the by-product of

an unconstitutional procedure?

CONSTITUTIONAL, STATUTORY AND RULES

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The Fifth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States provides in pertinent part:

“ No person shall . . . be deprived of life, liberty, or

property, without due process of law . . . ”

The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States provides in pertinent part:

“ No state shall make or enforce any law which

shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens

— 3 —

of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any

person of life, liberty, or property, without due proc

ess of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdic

tion the equal protection of the laws.”

Habeas corpus is codified in Title 28, United States

Code, which provides in pertinent part:

§ 2241. Power to grant writ

“ (a) Writs of habeas corpus may be granted by

the Supreme Court, any justice thereof, the district

courts and any circuit judge within their respective

jurisdictions . . .

“ (c) The writ of habeas corpus shall not extend

to a prisoner unless—

4

“ (3) He is in custody in violation of the Constitu

tion or laws or treaties of the United States . . . ”

‘ ‘§2244. Finality of Determination

(c) In a habeas corpus proceeding brought in be

half of a person in custody pursuant to the judgment

of a State court, a prior judgment of the Supreme

Court of the United States on an appeal or review

by a writ of certiorari at the instance of the prisoner

of the decision of such State court, shall be conclusive

as to all issues of fact or law with respect to an as

serted denial of a Federal right which constitutes

ground for discharge in a habeas corpus proceeding,

actually adjudicated by the Supreme Court therein,

unless the applicant for the writ of habeas corpus

shall plead and the court shall find the existence of

a material and controlling fact which did not appear

in the record of the proceeding in the Supreme Court

and the court shall further find that the applicant

for the writ of habeas corpus could not have caused

such fact to appear in such record by the exercise of

reasonable diligence.”

— 4 —

Title 28, United States Code, further provides:

“ §2403. Intervention by United States;

constitutional question

In any action, suit or proceeding in a court of the

United States to which the United States or any

agency, officer or employee thereof is not a party,

wherein the constitutionality of any Act of Congress

affecting the public interest is drawn in question, the

court shall certify such fact to the Attorney General,

and shall permit the United States to intervene for

presentation of evidence, if evidence is otherwise ad

missible in the case, and for argument on the question

of constitutionality. The United States shall, subject

to the applicable provisions of law, have all the rights

of a party and be subject to all liabilities of a party

as to court costs to the extent necessary for a proper

presentation of the facts and law relating to the ques

tion of constitutionality.”

The 1954 rules of this Court were in effect at the time

of the certiorari grant (June 12, 1967). Rule 23, The Pe

tition for Certiorari, remained unchanged in pertinent part

by the 1967 amended rules, and was as follows:

“ 1. The petition for writ of certiorari shall contain

in the order here indicated—

“ (c) The questions presented for review, expressed

in the terms and circumstances of the case but without

unnecessary detail. The statement of a question pre

sented will be deemed to include every subsidiary

question fairly comprised therein. Only the questions

set forth in the petition or fairly comprised therein

will be considered by the court.”

Rule 33

“ (2) (b) In any proceeding in whatever court

arising wherein the constitutionality of any Act of

— 5 —

Congress affecting the public interest is drawn in

question and the United States or any agency, officer

or employee thereof is not a party, all initial plead

ings, motions or papers in this court shall recite that

28 U.S.C., § 2403 may be applicable and shall be served

upon the Solicitor General, Department of Justice,

Washington, D.C. 20530. In proceedings from any

court of the United States as defined by 28 U.S.C.,

§ 451, such initial pleading, motion or paper shall

state whether or not any such court has, pursuant to

28 U.S.C., § 2403, certified to the Attorney General the

fact that the constitutionality of such Act of Congress

was drawn in question.”

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The respondent Mr. Biggers was convicted of committing

a rape at knifepoint which occurred in 1965. Seven months

after the offense, while Mr. Biggers was being detained as

a suspect in another rape case, the victim identified him

as her assailant. The subsequent conviction based on that

identification was affirmed by the Tennessee Supreme

Court. This Court granted certiorari, heard oral argu

ment, and affirmed the conviction by a four to four vote.

Plenary consideration was given before this Court to all

aspects of the identification question.

Shortly thereafter, Mr. Biggers filed a federal habeas

corpus action. The District Court for the Middle District

of Tennessee after an evidentiary hearing found the po

lice station identification improper and voided the convic

tion. The Sixth Circuit affirmed, primarily because the

judges who wrote the majority opinion thought the Dis

trict Judge decided a different question than that pre

sented this Court on certiorari. Judge Brooks in dissent

felt that this Court had indeed decided the precise ques

tion so as to import finality in the matter.

— 6 —

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

1. A 4-4 Affirmance by This Court of a State’s Highest

Court Is Res Judicata as to the Same Issue Between the

Same Parties in a Future Habeas Corpus Action.

The Sixth Circuit incorrectly decided important federal

questions in conflict with a specific previous ruling by this

Court and, further, in conflict with a constitutional stat

ute. The Court has so far departed from applicable law

as to call for an exercise of this Court’s power of super

vision.

The District Judge ordered a new trial untainted by the

identification procedures at the police station. The Court

indicated that it would not apply 28 U.S.C. § 2244(c),

supra, and if it did apply that statute, under the facts of

this case, it might be unconstitutional (App. B). The

Sixth Circuit did not mention this statute in arriving at

its decision. It is the position of Petitioner that the stat

ute does apply and both lower courts improperly dis

regarded it.

Pursuant to Rule 33(2) (b) of this Court, it appearing

that 28 U.S.C. § 2403 may be applicable, three copies of

this petition have been served upon the Solicitor General,

Department of Justice, Washington, D. C. 20530. No court

below has certified that the constitutionality of 28 U.S.C.

§ 2244(c) was drawn in question.

The Court of Appeals majority opinion gave three rea

sons why it thought the identification matter could be adju

dicated in federal habeas corpus despite this Court’s pre

vious affirmance. All three reasons are erroneous. They

are as follows:

— 7 —

a) The District Judge did not decide the same question

as this Court did.

It is said below that different facts were considered on

federal habeas corpus than were considered by this Court

on certiorari. The majority points to language in the peti

tion for certiorari which mentions voice identification.

Their conclusion that the certiorari grant was so very nar

row overlooks Rule 23 of this Court which says that the

statement of a question presented is deemed to include

every subsidiary question fairly comprised therein.

Specifically, the argument is that this Court considered

only voice identification, whereas the District Court con

sidered the totality of the circumstances. With the excep

tion of certain language heretofore noted respecting voice

identification in the certiorari petition, the parties in their

briefs, oral arguments, petition to rehear, and again in the

court below, have always given plenary treatment to the

identification question.

The District Judge sought to avoid the adjudication by

this Court by saying that the voice identification took place

during a show-up and since he found the show-up proce

dure unconstitutional, he need not reach the voice identifi

cation. Yet implicit in this Court’s affirmance of the State

conviction was the fact that it was necessary for this Court

to consider the constitutionality of the former in order to

adjudicate the latter.

b) Res judicata does not apply in the usual sense under

the facts of this case.

This was the second reason the Sixth Circuit gave in

affirming the District Judge. It is true that res judicata

does not apply to a federal habeas corpus action. Sub

sequent decisions may be retroactive. New evidence may

— 8 —

be discovered. The Sixth Circuit was correct in stating

the general principle but applied this principle improperly.

It should have been persuasive to the lower courts that

a constitutional claim that has been thoroughly thrashed

out as was the case here has been settled. There should

be finality between these two parties at least with respect

to this issue. Sanders v. United States, 373 U.S. 1 (1963).

c) The equally divided affirmance means only that the

judgment below remained in effect.

The majority said, “ As we read these decisions, the

equally divided vote of the United States Supreme Court

in Biggers v. Tennessee, 390 U.S. 404 (1968), means only

that ‘ the judgment of [the Supreme Court of Tennessee]

remains in effect citing Anderson v. Johnson, Warden,

390 U.S. 456 (1968). This is an oversimplification.*

This Court in the Biggers case gave plenary considera

tion to the identification question and affirmed the

Tennessee Supreme Court. To the Petitioner, an affirm

ance means that the judgment below is affirmed.

To allow it to be overturned the next day would render

the affirmance meaningless. Judge Brooks’ dissent cites

a number of cases which he believes hold that an equal

division affirmance means a conclusive decision on the

facts. Leading cases are Etting v. United States Bank,

24 U.S. (11 Wheat.) 59 (1826); Durant v. Essex Com

pany, 74 U.S. (7 Wall.) 107 (1868); Hertz v. Woodman,

218 U.S. 205 (1909); and United States v. Pink, 315 U.S.

203 (1941). The fact that the major authorities are so

old and the question is unsettled militates in favor of a

* This is accepted as an affirmance by others including the

Government Printing Office in its slip opinions. An example is

the affirmance by an equally divided court in Radich Appel

lant v. New York, 401 U.S. 531 (1971).

— 9 —

grant of certiorari to decide this important question. The

only Twentieth Century authority the court below was

able to muster was Anderson v. Johnson, Warden, 390

U.S. 456 (1968).

2. The Resolution on the Merits of the Alleged Uncon

stitutional Identification Is Inconsistent With Previous

Decisions of This Court.

The identification was made in 1965 when Mr. Biggers

was shown to the victim at the police station. The lower

court incorrectly applied the totality of the circumstances

test discussed in Stovall v. Denno, 388 U.S. 293 (1967),

and other lineup and show-up cases. See, e.g., Coleman

v. Alabama, 399 U.S. 1 (1970), and Foster v. California,

394 U.S. 440 (1968). Four Justices of this Court have so

thought as indicated by their vote for affirmance when

this same issue was here before.

CONCLUSION

A writ of certiorari should issue to review the judg

ment and opinion of the Sixth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted

BART C. DURHAM, III

Assistant Attorney General

211 Supreme Court Building

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

Telephone (615) 741-2091

Counsel for Petitioner

Of Counsel

DAVID M. PACK

Attorney General

APPENDIX

— A -l —

APPENDIX A

No. 20540

United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit

Archie Nathaniel Biggers,

Petitioner-Appellee,

v.

William S. Neil, Warden, Tennes- ”

see State Penitentiary, Nashville,

Tennessee,

Respondent-Appellant. -/

Decided and Piled August 18, 1971

Before: Edwards, McCree and Brooks, Circuit Judges.

Edwards, Circuit Judge. In this case we are asked by

the State of Tennessee to review and reverse the issuance

of a writ of habeas corpus sought by petitioner Biggers

in the United States District Court for the Middle District

of Tennessee. After a full hearing and after review of the

full record of the proceedings in the state courts of Ten

nessee wherein Biggers had been convicted of rape and

sentenced to 20 years in Tennessee’s State Vocational

Training School, the District Judge found that identifica

tion procedures employed by Nashville police and subse

quently made the subject of extensive testimony at trial

had been so essentially unfair as to represent a depriva

tion of appellant’s federal constitutional right to due

process of law. He ordered Tennessee either to retry

appellant or release him.

The District Court found the facts pertinent to issuance

of the writ as follows:

A p p e a l from the

United States Dis

trict Court for the

Middle District of

Tennessee, Nash

ville Division.

— A-2 —

“ On the evening of January 22, 1965, Mrs. Mar

garet Beamer was attacked at knife-point by an in

truder who broke into her home. Mrs. Beamer’s

screams aroused her thirteen-year old daughter who

rushed to the scene and also began to scream. At this

point, the intruder is alleged to have said to Mrs.

Beamer, ‘ You tell her to shut up, or I ’ll kill you

both.’ This Mrs. Beamer did, whereupon she was

taken from the house to a spot two blocks away and

raped. The entire episode occurred in very dim light

and the rape itself occurred in moonlight. As a re

sult, Mrs. Beamer could give only a very general

description of her assailant, describing him as being

fat and flabby with smooth skin, bushy hair and a

youthful voice.

“ Over a seven month period following the crime

the police showed Mrs. Beamer various police photo

graphs and had her attend several ‘ line-ups’ and

‘ show-ups.’ However, the victim was unable to iden

tify any of the persons shown to her as being her

assailant. Finally, on August 17, 1965, petitioner was

arrested as a suspect in the rape of another woman.

While petitioner was being detained in connection

with that case the police asked Mrs. Beamer to come

to the police station to ‘ look at a suspect.’ The iden

tification process employed at this point was called

a show-up.

# # #

“ At the instant show-up Mrs. Beamer identified

petitioner as being her assailant. As to what tran

spired at the show-up, there is some conflict between

the testimony given by Mrs. Beamer at the trial and

that given by her at the evidentiary hearing held in

this court on October 30, 1969. In testimony given at

the trial, Mrs. Beamer testified that on viewing the

petitioner the ‘ first thing’ that made her think he

— A-3 —

might be her assailant was his voice. However, at the

October hearing, Mrs. Beamer testified that she iden

tified petitioner positively prior to having him speak

the words spoken by Mrs. Beamer’s attacker more

than seven months earlier during the crime— ‘ You

tell her to shut-up or I ’ll kill you both.’ There is also

conflict between the testimony given by police officers

at the trial and that given by them at the October

hearing as to whether or not identification of peti

tioner was made before or after he was asked to

speak these words.

“ At any rate, petitioner was identified at this

show-up as being Mrs. Beamer’s attacker, and the

subsequent indictment and conviction of petitioner

was based almost exclusively upon this station house

identification.1

The District Judge reviewed this record on a legal

standard recently reiterated by the United States Supreme

Court in language which is directly applicable here:

“ In United States v. Wade, 388 U. S. 218 (1967),

and Gilbert v. California, 388 U. S. 263 (1967), this

Court held that because of the possibility of unfair

ness to the accused in the way a lineup is conducted,

a lineup is a ‘ critical stage’ in the prosecution at

which the accused must be given the opportunity to

be represented by counsel. That holding does not,

however, apply to petitioner’s case, for the lineups

in which he appeared occurred before June 12, 1967.

Stovall v. Denno, 388 U.S. 293 (1967). But in de

claring the rule of Wade and Gilbert to be applicable

only to lineups conducted after those cases were de

cided, we recognized that, judged by the ‘ totality of

,!1 There is considerable doubt on reading the trial record

as to whether or not Mrs. Beamer made a positive in-court

identification of petitioner at the time of the trial.”

— A-4 —

the circumstances,’ the conduct of identification pro

cedures may be ‘ so unnecessary suggestive and con

ducive to irreparable mistaken identification’ as to

be a denial of due process of law. Id., at 302. See

Simmons v. United States, 390 U.S. 377, 383 (1968);

cf. P. Wall, Eye-Witness Identification in Criminal

Cases; J. Frank & B. Frank, Not Guilty; 3 J. Wig-

more, Evidence, § 786a (3d ed. 1940); 4, id., §1130.”

Foster v. California, 394 U.S. 440, 442 (1968).

Employing the term “ show-up” to refer to a situation

where police bring a single suspect before a victim of

crime for identification purposes, the District Judge held:

“ On this basis the Court must conclude that the

circumstances here present are not such as to warrant

the show-up procedure and, consequently, that its use

at petitioner’s trial denied him due process of law.

# * *

[TJhere is no indication that a truly concerted effort

was made to produce suitable subjects for a line-up.

Aside from a phone call to the juvenile home and a

screaming of Metro Jail inmates no other efforts were

made. There are several other prison facilities in the

area and there is no evidence that any effort was

made to screen them for subjects. The Court sees no

reason why this could not have been done in order to

maximize the fairness of the identification process.

Here, there was no evidence of any death-bed urgency

as in Stovall which would have precluded the police

from delaying the identification procedure until a

suitable line-up could have been arranged. The crime

was seven months old, the victim was fully recovered

and well, and there are no other indications that the

ends of justice demanded an immediate show-up

rather than a much more reliable line-up. Further-

— A-5 —

more, none of the other circumstances which the above

discussed cases indicate may justify a show-up ex

isted in the instant case. The evidence clearly shows

that the complaining witness did not get an oppor

tunity to obtain a good view of the suspect during

the commission of the crime.2 Also, the show-up con

frontation was not conducted near the time of the

alleged crime, but, rather, some seven months after

its commission.3 Finally the witness in the instant

case was unable to give either an independent photo

graphic identification of the suspect or a good physi

cal description of her assailant.4 The nature of the

show-up as conducted in this case—with the great

lapse of time between the crime and the identification,

the hesitancy of the witness in identifying the peti

tioner,5 the circumstances of the stationhouse con

frontation coupled with Mrs. Beamer’s knowledge

that petitioner was thought by police to be her as

sailant,—tended to maximize the possibility of mis-

identification of the petitioner. True, it may have

been more convenient for the police to have a

show-up. However, in matters of constitutional due

process where police convenience is balanced against

the need to extend basic fairness to the suspect in a

criminal case, the latter value should always outweigh

“ 2 The only other eye-witness, Mrs. Beamer’s daughter

could not identify Biggers. And see, the case o f United

States ex rel. Garcia v. Follette, supra [417 F.2d 709 (2d Cir.

1969)] and accompanying text and cases.

“ 3 See the case of United States ex rel. Williams v. La-

Vallee, supra [415 F.2d 643 ( 2d Cir. 1969), cert, denied 397

U.S. 997 (1971)] and accompanying text and cases.

“ 4 See the case of United States v. Thompson, supra [417

F.2d 196 (4th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 1047 (1970)]

and accompanying text and cases.

“ 5 See United States v. Gilmore, supra [398 F.2d 679 ( 7th

Cir. 1968)] and accompanying text.” (Footnotes in quotation.)

— A-6 —

the former. In this case it appears to the Court that

a line-up, which both sides admit is generally more

reliable than a show-up, could have been arranged.

The fact that this was not done tended needlessly to

decrease the fairness of the identification process to

which petitioner was subjected.

“ Due process of law and basic fairness demand that

the most reliable method of identification possible be

used in a criminal case. See, Simmons v. United

States, supra, [390 U.S. 377 (1967)] at 383-384. The

conduct of the show-up in this case created an atmos

phere which was so suggestive as to enhance the

chance of misidentification and hence constituted a

violation of due process.

“ Clearly, this identification did not amount to a

harmless error, since the victim’s identification of

petitioner was virtually the only evidence upon which

the conviction was founded. See, Chapman v. Cali

fornia, 386 U.S. 18 (1966).

# # *

“ Accordingly, judgment will be entered granting

the application of Archie Nathaniel Biggers for a

writ of habeas corpus, voiding the conviction ob

tained in the state court, and discharging the peti

tioner from custody after the state has had a reason

able time to retry him upon the same charge, any such

new trial to be unaffected by Mrs. Beamer’s station-

house identification and the testimony of the police

officers who were present when it took place.’ Biggers

v. Tennessee, supra, at 409, [390 U.S. 404 (1968)].

We too have reviewed the state trial court record and

the appellate record above that, as well as somewhat dif

ferent transcript developed in the testimony before the

District Judge. We believe the record does not allow us to

— A-7 —

find that the conclusions of fact of the District Judge are

clearly erroneous.

In addition, we find no error in the District Judge’s un

derstanding of the principles of due process of law as they

apply to identification proceedings prior to decision of the

Wade,1 Gilbert1 2 cases. Normally this would mean affirm

ance of the judgment on the careful opinion written by

Judge Miller3 in the court below.

What divides our panel, however, is the effect of the

direct appeal proceedings which preceded the instant fed

eral habeas corpus case. These included affirmance of ap

pellant Biggers’ conviction by the Supreme Court of Ten

nessee, a grant of certiorari by the United States Supreme

Court, and the subsequent affirmance of the decision of

the Supreme Court of Tennessee by an equally divided

vote of the membership of the United States Supreme

Court. Our brother finds in the appellate proceedings

which culminated with a 4-4 affirmance by the United

States Supreme Court a final adjudication of all due

process issues arising out of the pretrial identification

measures employed in relation to appellant Biggers. As

we understand the matter, he regards the 4-4 vote as the

expression of a final federal view upon the critical due

process question involved in this appeal, and believes that

it precluded the District Judge from entertaining, taking

testimony on, or making findings of fact in relation to the

pretrial identification process in the course of appellant

Biggers’ petition for a federal writ of habeas corpus.

There are three reasons which compel our disagree

ment:

1 United States v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218 (1967).

2 Gilbert v. California, 388 U.S. 263 (1967).

3 Judge William E. Miller is now a member of the United States

Court o f Appeals for the Sixth Circuit.

— A-8 —

First, the District Judge decided a different question

than that which had been presented to the United States

Supreme Court on certiorari.

The question upon which certiorari was granted as

stated in the Application for Certiorari was:

“ The petitioner, a 16 year-old Negro boy, was com

pelled by the police, while alone in their custody at

the police station, to speak the words spoken by a

rapist during the offense almost eight months earlier

for voice identification by the prosecutrix.

“ Was the denial of petitioner’s right to personal

dignity and integrity by the police, and the failure to

give him benefit of counsel, provide him with a line

up, or with any other means to assure an objective,

impartial identification of his voice by the prosecutrix

a violation of petitioner’s Fifth, Sixth and Fourteenth

Amendment rights'?” (Emphasis added.)

As is clear from the quotation below from Judge

Miller’s opinion, he expressly did not decide the effect of

voice identification, except perhaps as a portion of “ the

totality of circumstances” of an impermissibly suggestive

show-up:

“ [T]he Court finds it unnecessary to reach the is

sue of whether voice identification as used here

amounted in itself to a violation of due process. It

may be that the validity of such identification should

normally be left to the jury. Since the voice identifica

tion took place during the show-up and the show-up

procedure itself is unconstitutional as employed in

this case, there is no reason to reach the specific is

sue raised concerning voice identification.”

While obviously four members of the court felt that the

grant of certiorari opened the door for consideration of a

— A-9 —

broad due process question, it is entirely possible that

some or all of the four members who voted against re

versal did so solely on the voice identification issue

squarely represented by the application for certiorari.4

Secondly, as we understand the controlling decisions of

the United States Supreme Court, we believe that the

doctrine of res judicata does not apply in the usual sense

in federal habeas corpus proceedings. Fay v. Noia, 372

U.S. 391 (1963); Sanders v. United States, 373 U.S. 1

(1963); Townsend v. Sain, 372 U.S. 293 (1963).

In Fay v. Noia the Supreme Court said:

“ The breadth of the federal courts’ power of inde

pendent adjudication on habeas corpus stems from

the very nature of the writ, and conforms with the

classic English practice. As put by Mr. Justice Holmes

in his dissenting opinion in Frank v. Mangum, supra,

at 348: ‘ I f the petition discloses facts that amount to

a loss of jurisdiction in the trial court, jurisdiction

could not be restored by any decision above.’ It is of

the historical essence of habeas corpus that it lies to

test proceedings so fundamentally lawless that im

prisonment pursuant to them is not merely erroneous

but void. Hence, the familiar principle that res judi

cata is inapplicable in habeas proceedings, see, e. g.,

Barr v. Burford, 339 U.S. 200, 214; Salinger v. Loisel,

265 U.S. 224, 230; Frank v. Mangum, 237 U.S. 309,

334; Church, Habeas Corpus (1884), §386, is really

but an instance of the larger principle that void judg

ments may be collaterally impeached. Restatement,

Judgments (1942), §§ 7, 11; Note, Res Judicata, 65

4 Since certiorari was granted on the issue o f voice identifica

tion, the briefs presented before the Supreme Court (quoted at

length in Judge Brooks’ dissent) could not expand the scope of the

Supreme Court’s consideration merely by discussing broader due

process questions.

— A-10 —

Harv. L. Eev. 818, 850 (1952). Cf. Windsor v. Mc-

Veight, 93 U. S. 274, 282-283. So also, the traditional

characterization of the writ of habeas corpus as an

original (save perhaps when issued by this Court)

civil remedy for the enforcement of the right to per

sonal liberty, rather than as a stage of the state

criminal proceedings or as an appeal therefrom, em

phasizes the independence of the federal habeas pro

ceedings from what has gone before. This is not to say

that a state criminal judgment resting on a constitu

tional error is void for all purposes. But conventional

notions of finality in criminal litigation cannot he

permitted to defeat the manifest federal policy that

federal constitutional rights of personal liberty shall

not he denied without the fullest opportunity for plen

ary federal judicial review.” Fay v. Noia, supra at

422-24. (Emphasis added.) (Footnotes omitted.)

In Sanders, the Supreme Court discussed the same

principle:

‘ ‘ At common law, the denial hy a court or judge of

an application for habeas corpus was not res judicata.

King v. Suddis, 1 East 306, 102 Eng. Rep. 119 (K. B.

1801); Burdett v. Abbot, 14 East 1, 90, 104 Eng. Rep.

501, 535 (K. B. 1811); Ex parte Partington, 13 M. &

W. 679, 153 Eng. Rep. 284 (Ex. 1845); Church,

Habeas Corpus (1884), §386; Ferris and Ferris, Ex

traordinary Legal Remedies (1926), §55. ‘ A person

detained in custody might thus proceed from court

to court until he obtained his liberty.’ Cox v. Hakes,

15 A. C. 506, 527 (H. L., 1890). That this was a prin

ciple of our law of habeas corpus as well as the Eng

lish was assumed to he the case from the earliest

days of federal habeas corpus jurisdiction. Cf. Ex

parte Burford, 3 Cranch 448 (Chief Justice Mar

shall). Since then, it has become settled in an un

broken line of decisions. Ex parte Kaine, 3 Blatchf.

— A -ll —

1, 5-6 (Mr. Justice Nelson in Chambers); In re

Kaine, 14 How. 103; Ex parte Cuddy, 40 F. 62, 65

(Cir. Ct. S. D. Cal. 1889) (Mr. Justice F ield ); Frank

v. Mangum, 237 U.S. 309, 334; Salinger v. Loisel, 265

U. S. 224, 230; Waley v. Johnston, 316 U. S. 101;

United States ex rel. Accardi v. Shaugh/nessy, 347

U. S. 260, 263, n. 4; Heflin v. United States, 358 U. S.

415, 420 (opinion of Mr. Justice Stewart) (dictum);

Powell v. Sacks, 303 F.2d 808 (C. A. 6th Cir. 1962).

Indeed, only the other day we remarked upon ‘ the

familiar principle that res judicata is inapplicable in

habeas proceedings.’ Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391, 423.

“ It has been suggested, see Salinger v. Loisel,

supra, at 230-231, that this principle derives from the

fact that at common law habeas corpus judgments

were not appealable. But its roots would seem to go

deeper. Conventional notions of finality of litigation

have no place where life or liberty is at stake and in

fringement of constitutional rights is alleged. I f ‘ gov

ernment . . . [is] always [to] be accountable to the

judiciary for a man’s imprisonment,’ Fay v. Noia,

supra, at 402, access to the courts on habeas must not

be thus impeded. The inapplicability of res judicata

to habeas, then, is inherent in the very role and fu/nc-

tion of the writ.” Sanders v. United States, supra at

7-8. (Emphasis added.) (Footnotes omitted.)

Thirdly, we do not believe that logically or historically

a 4-4 division of the United States Supreme Court can be

held to represent any federal adjudication of appellant’s

federal constitutional claims on the merits.

An equal division of an appellate court does not settle

any principle of law or issue of fact for that court. It rep

resents affirmance of the judgment appealed from because

there were insufficient votes for reversal.

Supreme Court opinions which we believe to be settled

law demonstrate both principles:

— A-12

“ In the very elaborate arguments which have been

made at the bar, several cases have been cited which

have been attentively considered. No attempt will be

made to analyze them, or to decide on their applica

tion to the case before us, because the judges are

divided respecting it. Consequently, the principles of

law which have been argued cannot be settled; but

the judgment is affirmed, the court being divided in

opinion upon it.” Etting v. United States Bank, 24

U.S. 57, 76 (1826). (Emphasis added.)

“ In cases of appeal or writ of error in this court,

the appellant or plaintiff in error is always the mov

ing party. It is affirmative action which he asks. The

question presented is, shall the judgment, or decree,

be reversed? If the judges are divided, the reversal

cannot be had, for no order can be made. The judg

ment of the court below, therefore, stands in full

force. It is, indeed, the settled practice in such case

to enter a judgment of affirmance; but this is only

the most convenient mode of expressing the fact that

the cause is finally disposed of in conformity with the

action of the court below, and that that court can

proceed to enforce its judgment. The legal effect

would be the same if the appeal, or writ of error,

were dismissed.” Durant v. Essex Co., 74 U.S. 107,

112 (1868). (Emphasis added.)

“ Four members of the Court would reverse. Four

members of the Court would dismiss the writ as im-

providently granted. Consequently, the judgment of

the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit remains in effect.” Anderson v. Johnson,

Warden, 390 U.S. 456 (1968). (Emphasis added.)

As we read these decisions, the equally divided vote of

the United States Supreme Court in Biggers v. Tennessee,

390 U.S. 404 (1968), means only that “ the judgment of

— A-13 —

[the Supreme Court of Tennessee] remains in effect.”

Anderson v. Johnson, supra, at 456. There is, of course,

no doubt that federal habeas corpus allows for subsequent

federal review of claims of federal constitutional viola

tions after final state court judgment. And it is clear from

the opinion of the Supreme Court of Tennessee, 411 S.W.

2d 696 (1967), that it neither considered nor decided the

federal constitutional validity of the “ show-up” which the

District Judge on habeas found invalid.

The judgment of the District Court is affirmed.

Brooks, Circuit Judge, dissenting. I respectfully dissent.

As indicated in the majority opinion, this is an appeal by

the State of Tennessee from an order of the District

Court granting petitioner-appellee, Archie Nathaniel Big-

gers, a writ of habeas corpus. Petitioner Biggers was

convicted in state court for the crime of rape. Upon appeal

to the Supreme Court of Tennessee the conviction was

affirmed. Biggers v. State, 219 Tenn. 553, 411 S.W.2d 696

(1967), rein, denied March 1, 1967. An appeal to the United

States Supreme Court followed. Certiorari was granted,

388 U.S. 909 (1967), and the Supreme Court affirmed the

judgment of the Supreme Court of Tennessee by an

equally divided Court. Biggers v. Tennessee, 390 U.S. 404

(1967), reh. den. 390 U.S. 1037 (1967). Petitioner then

brought this action for a writ of habeas corpus. The Dis

trict Court granted the writ, basing its decision to set

aside petitioner’s state conviction upon its conclusion that

the totality of circumstances surrounding petitioner’s pre

trial identification presented a significant possibility of

irreparably mistaken identification,1 and, therefore, peti

1 Petitioner’s identification preceded the decisions in United

States v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218 (1967), and Gilbert v. California,

388 U.S. 263 (1967), and the standards established by those cases

are not to be applied retroactively, Stovall v. Denno, 388 U S 293

(1967).

— A-14 —

tioner’s constitutional due process rights were violated

when this identification (the sole identification evidence)

was testified to by the police at the state trial. A number

of other constitutional challenges were raised, however,

since the District Court concluded that the pretrial iden

tification prejudiced petitioner’s constitutional rights, it

did not reach the merits of the other claims. For reasons

hereafter stated, I would reverse the judgment and re

mand to the District Court for consideration of the other

claims raised by the petition for habeas corpus.

The State of Tennessee has raised two issues on this

appeal. First, whether the District Court properly enter

tained the petition for habeas corpus in light of the United

States Supreme Court’s affirmance of petitioner’s con

viction. Second, whether petitioner was denied a fair trial

as a result of the use of the identification evidence alleg

edly the by-product of an unconstitutional identification

procedure. The District Court decided both issues in favor

of petitioner Biggers, and the State of Tennessee contends

both conclusions are erroneous. While the issues as for

mulated by the State of Tennessee generally convey the

nature of the questions under review, they do not ac

curately delineate the legal controversy involved. Thus,

there is really no doubt that the District Court had the

power to entertain the petition for habeas corpus, how

ever, the essence of the dispute is whether the power of

the court to collaterally review petitioner’s state convic

tion extended to the issue of the constitutional infirmity

of the pretrial identification procedure. And the question

which divides this Court is what effect, if any, did the

United States Supreme Court’s equally divided affirm

ance of petitioner’s state conviction have upon subsequent

District Court reconsideration, by collateral review, of the

identical issue presented to the Supreme Court. I view

the crucial issue in this case as essentially one of litigious

finality in criminal matters. See Bator, Finality in Grim-

— A-15 —

inal Law and Federal Habeas Corpus for State Prisoners,

76 Harv. L. Rev. 441 (1963), for a discussion of relevant

policy considerations.

The District Court’s conclusion on the matter of finality

is summed up by its holding that:

“ The fact that petitioner’s conviction was tech

nically affirmed by reason of the United States Su

preme Court’s even division of opinion is of no con

sequence here since the merits of the claim were not

adjudicated. Even if they had been adjudicated,

Sanders shows that those claims would not have been

automatically barred from consideration by this Court

in a habeas corpus proceeding.”

The District Court, as well as the majority opinion con

strue the language in Sanders v. United States, 373 U.S.

1 (1962), and Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1962), that prin

ciples of “ res judicata are inapplicable in habeas proceed

ings” to mean that a District Court has jurisdiction to

entertain any and all claims raised by a habeas corpus

petition. However, I do not interpret that language em

ployed in Sanders and Noia, supra, to mean there is no

finality in a criminal matter. Clearly a criminal defend

ant having had a particular issue fully litigated first in

state court and then federal court, simply cannot turn

around upon an adverse resolution of the issue and start

the whole process of litigating the question again. The

point is well taken, and I do not see a difference of views

on the question, that res judicata will not bar the criminal

defendant from beginning a habeas corpus proceeding in

the United States District Court which raises new issues

or issues not fully litigated in the state or federal courts.

However, logic and precedent dictate that a defendant is

collaterally estopped from relitigating the merits of an

issue plenarily litigated and resolved on the merits against

him. See Gaitan v. United States, 295 F.2d 277, 280 (10th

— A-16 —

Cir. 1961), cert, denied 369 U.S. 857 and 9 A.L.R.3d 213,

discussing the confusion resulting from the indiscriminate

use of res judicata nomenclature. Also see, United States

ex rel. Schnetzler v. Follette, 406 F.2d 319, 322 (2nd Cir.

1969), cert, denied 395 U.S. 926, basing a similar holding

on the principle of stare decisis.

As has been indicated, the difficult question dividing this

Court is whether the issue of the constitutional infirmity

of the pretrial identification procedure has been fully

litigated. That is, was the equally divided affirmance by

the United States Supreme Court of petitioner Biggers’

conviction an adjudication on the merits of the pretrial

identification issue. The majority feels that the constitu

tionality of the entire identification procedure had not

been scrutinized by the Supreme Court in the original

appeal because 1) the District Judge felt he was deciding

a different question than that presented to the Supreme

Court, that is, the District Judge concentrated his atten

tion on the legality of the show-up rather than on the

constitutionality of the voice identification; 2) the applica

tion for certiorari filed in the Supreme Court by petitioner

stresses only the constitutionality of the voice identifica

tion; and 3) there is no positive indication in Mr. Justice

Douglas’ dissenting opinion in Biggers v. Tennessee, 390

U.S. 404 (1968), that more than four Justices considered

a “ broad due process question” . I disagree and believe

the record simply does not support the majority’s con

clusion that the constitutionality of the entire pretrial

identification procedure was not wholly reviewed by the

Supreme Court.

First, I fail to see what significance can be attached to

the fact that the District Court felt that it was deciding

a different question than that which was presented to the

Supreme Court. Just because the District Court took

special interest in the legality of the show-up in assessing

the “ totality of circumstances” does not mean the Su

— A-17 —

preme Court ignored consideration of that fact or con

centrated solely on the voice identification in applying the

“ totality” test. Moreover, the appellate record shows

that the Supreme Court had before it all facets of the

identification procedure in reviewing the case on cer

tiorari. Thus, I see no importance in the fact that the

District Court chose to emphasize a previously considered

aspect of the totality of the identification procedure in

determining its constitutionality.

Secondly, I find absolutely no support in the Supreme

Court appellate record for the majority’s position that

Biggers’ application for certiorari limited the Court’s

review only to the constitutionality of the voice identifica

tion as, quite to the contrary, the record clearly shows

that the entire spectrum of factors surrounding the iden

tification procedure was presented in a broad due process

challenge to the conviction. As a preliminary observa

tion, it should be emphasized that even on this appeal

petitioner had admitted in his brief that the Supreme

Court reviewed the broad due process question. In foot

note five of petitioner’s brief it is stated:

“ The [Supreme] Court heard arguments and con

sidered briefs with respect to whether Biggers’ Fifth

and Fourteenth Amendment rights had been abridged

in (1) his identification violated the Due Process

Clause under the totality of circumstances test adopted

in Stovall v. Denno, 388 U.S. 293 (1967) and (2) the

use at trial of words which Biggers was compelled

to speak solely for purposes of voice identification

violated the Fifth Amendment as incorporated in the

Fourteenth. The latter question had been reserved by

the Court in United States v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218 at

223 (1967).”

While Biggers’ application for certiorari was phrased so

as to emphasize the voice identification question, the State

of Tennessee’s statement of the issues presented in its

— A-18 —

“ Brief In Opposition to the Petition for Writ of Cer

tiorari” definitely indicates a broader due process factual

review.2 Furthermore, the briefs accompanying the ap

plication for the writ of certiorari and the actual briefs

filed once the writ was granted unquestionably show that

all factors surrounding the identification procedure were

raised for review in the broadest due process challenge

possible. I recognize and regret that quoting from these

documents will substantially lengthen this dissenting

opinion, but I feel that it is necessary to demonstrate

conclusively that the Supreme Court had before it all

aspects of the identification procedure in hearing the

original appeal in this case, that there has been plenary

review of that issue, and that no new issues of fact or

law regarding this question were raised by petitioner in

his habeas corpus request.3

In the appeal to the Supreme Court the grounds for

granting certiorari were presented through Biggers’ “ Pe

tition and Brief for Writ of Certiorari” . In that docu

ment at pages 7-8, under subtitle “ Reasons for Granting

the W rit” , it is argued:

2 Question II in the State of Tennessee’s brief under the sub

title “ Questions Presented” was “ Whether or not the Sixth Amend

ment to the United States Constitution relating to assistance of

counsel requires counsel to be present during the identification pro

cedure, (1) when the investigation is but a general inquiry into

an unsolved crime, and (2 ) when held prior to commencement of

criminal proceedings” [Emphasis in original]. And, in the State

of Tennessee’s “ Supplemental Brief in Opposition to the Petition

for the Writ of Certiorari” the question specifically addressed was

“ whether or not petitioner was denied due process o f law by the

identification procedure followed at the police headquarters. . . .”

3 An additional reason for quoting at some length from these

documents is that they are not readily available. In quoting from

these materials, I have omitted footnotes and references to tran

script pages, however, the complete record of all documents

filed in this case in the Supreme Court may be found in

Volume 51. Transcripts of Records and File Copies of Briefs,

Nos. 232-237, Supreme Court of the United States, October Term

1967.

— A-19

Petitioner Was Denied His Rights Under the Due

Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and the

Fifth and Sixth Amendments to the United States

Constitution Under Circumstances Similar to Those

in Conflicting Court of Appeals Cases Granted Cer

tiorari and Presently Pending Before This Court.

The facts in this case are starkly simple, but they

raise a critical question of the fairness and impar

tiality of police identification practices. They reveal

that Archie Biggers was denied his right to a fair

trial by police practices which denied him elementary

Fourteenth Amendment protections.

The only evidence against petitioner at trial was

the identification made by the prosecutrix, Mrs. Mar

garet Beamer, that Archie Biggers was the man who

had raped her. Biggers, a 16 year old Negro was

arrested early on the morning of August 17, 1965 and

charged with the attempted rape of another woman

(Tr. 70). Later the same day, the police brought

Mrs. Beamer, who had been raped on the night of

January 22, 1965, almost eight months earlier (Tr. 4-7,

20, 85-88) to “ look at a suspect” (Tr. 27-28, 57, 106,

109-110). Unable to describe or identify her assailant

(Tr. 13) her case had remained without clues. Asked

to identify Biggers if she could, the first view she had

of the petitioner was of him alone in the custody and

presence of five police officers (Tr. 112). He had no

lawyer. The police then required him to speak the

exact words of the rapist spoken during the offense

(Tr. 6, 7, 17, 47, 93, 108, 112-113, 156), on the basis

of which she identified petitioner as the rapist. These

were the circumstances surrounding the identification

by the prosecutrix.

The facts in this case raise the issue present in

conflicting Second and Fifth Circuit cases which this

— A -20 —

Court has granted certiorari to determine. United

States ex rel. Stovall v. Denno, 355 F.2d 731 (2nd

Cir. 1966), cert, granted 34 U.S.L. Week 3429 (June

20, 1966); Wade v. United States, 358 F.2d 557 (5th

Cir. 1966), cert, granted 35 U.S.L. Week 3124 (Oct.

10, 1966). The Second Circuit, sitting en banc, held

that the defendant’s Fifth, Sixth and Fourteenth

Amendment rights were not violated when he was

taken to the victim’s hospital room for identification

without the benefit of a line-up or counsel, even though

arraignment had been postponed to allow him to ob

tain counsel. The Fifth Circuit, in Wade v. United

States, supra, specifically adopted the view of the dis

senting judges in United States ex rel. Stovall v.

Denno, supra. It excluded testimony of the line-up

on the ground that the line-up had violated the de

fendant’s constitutional rights because two witnesses

had seen him in the custody of the police shortly

before the line-up, and defendant’s counsel had not

been notified and was not present at the line-up.

Archie Biggers, like Wade, was denied elemental pro

tections against suggestion and the right to counsel

during the test to identify his voice. Indeed, the cir

cumstances of Biggers’ identification were less con

ducive to impartiality than those in United States v.

Wade, supra, and the arguable necessity for speed in

identification and difficulty in arranging a line-up in

volved in United States ex rel. Denno, supra, is not

present in this case.

In subsection II of that subtitle (“ The Facts in This

Case Show That Petitioner Was Denied Due Process of

Law and the Protection of the Fifth and Sixth Amend

ments to the Constitution of the United States” ) it is

argued:

To negate inference or suggestion from an identifi

cation proceeding, a line-up is generally regarded as

— A-21 —

essential to provide a mode of comparison by police

authorities. See Criminal Investigation and Interro

gation, Gerber and Scbroeder ed., §22.20 (1962);

Criminal Investigation, Jackson ed. (5th ed. 1962) at

pp. 41-42. The failure to provide Archie Biggers with

the protection of a line-up in a rape case, considering

his youth, the eight month period since the rape and

other circumstances is inexcusable. There was no

reason for the lack of a line-up, and every reason to

provide one. As Archie Biggers was being held in

police custody for an unrelated charge, this is not a

case of street identification immediately after arrest,

nor even a case where it was physically impossible to

hold a line-up. Nor was there need to identify Archie

Biggers quickly. Mrs. Beamer had been raped eight

months earlier and the time necessary to arrange a

line-up certainly would not have affected her identifi

cation. Indeed, the time lapse, well known to the

police, should have been sufficient to mandate a line-up

to police conscientiously seeking an impartial, dispas

sionate identification.

Again in subsection II at pages 12-13 it is argued:

Archie Biggers was also denied his right to assist

ance of counsel at the time of his identification, clearly

a “ critical stage” in his case. Escobedo v. Illinois,

378 U.S. 478, 486 (1964). The police were without a

clue to the identity of the man who had raped Mrs.

Beamer. If she could identify a man it would cer

tainly form at least the basis for prosecution. If

counsel had been present he could have done several

things to insure an impartial test. He could have

requested a line-up, or alternatively some other plan

to assure conditions designed to avoid suggestion. If

present, counsel could have questioned the prosecutrix

during identification before she had placed herself in

the position of making a positive identification. It is

quite possible that his mere presence would have

served to counterbalance that of the police, and the

inherent suggestiveness of police station identifica

tion of one in custody. Had counsel been present he

might have prevented the police from requiring the

petitioner to speak the words of the rapist, words

which carried an inherent suggestion of guilt. Or

counsel might have advised his client to remain silent.

The circumstances of this case, taken separately and

in combination, establish violations of the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and through it,

violations of the Fifth and Sixth Amendments.

In the State of Tennessee’s “ Brief in Opposition to the

Petition for Writ of Certiorari” it is argued at page 8:

Petitioner urges this Court to grant certiorari in

this case because he contends that the identical ques

tion raised here is presented in the two (2) cases

mentioned in which this Court has previously granted

certiorari. Respondent respectfully insists that the

questions are not the same.

It is clear from an analysis of United States ex rel.

Stovall v. Denno, supra, and Wade v. United States,

supra, that the question in those cases is not whether

it is a violation of due process for a victim to identify

an accused during an identification procedure at police

headquarters, but whether it is incumbent upon the

State to provide counsel to the accused at the identi

fication procedure following the commencement of

criminal proceedings against him. The case at bar is

unlike those cases inasmuch as at the time of the

identification of the accused by Mrs. Beamer, no crimi

nal proceedings had commenced insofar as this matter

is concerned. The plain truth is that the petitioner

had been arrested on a separate charge and as a mat

— A-22 —

— A-23 —

ter of general inquiry Mrs. Beamer was called to see

whether or not she could identify him.

Once certiorari was granted the briefs decidedly show

that the Supreme Court had before it for review each and

every aspect of the identification procedure so as to assess

the “ totality of circumstances.” Beside the point that the

“ totality” test raises a factually all encompassing due

process issue, in Biggers’ Supreme Court brief under the

subtitle “ Argument” the broadest due process argument

is made. Therein, at pages 8-18, it is argued:

The Circumstances of Petitioner’s Pre-Trial Identi

fication and Its Use as Evidence at Trial Deny Him

Due Process of Law as Guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment.

The decisions of this Court in United States v.

Wade, 388 U.S. 218 (1967) and Gilbert v. California,

388 U.S. 263 (1967) holding pre-trial identification in

absence of counsel violates the Sixth Amendment,

would require reversal in this case but for the decision

in Stovall v. Denno, 388 U.S. 293 (1967), barring their

retroactive effect. Like Wade and Gilbert, Biggers

was denied the right to the assistance of his retained

counsel by the police holding a pre-trial identification

proceeding in his attorney’s absence. The Court re

manded Wade to determine whether a subsequent in

court identification should be excluded as the tainted

product of the line-up identification, while Gilbert ex

cluded in-court testimony of the pre-trial identification

per se. As petitioner was convicted on the testimony

of the prosecutrix’s pre-trial identification at a showup

(she did not attempt to identify him at trial) where

petitioner was unrepresented by counsel, Biggers

would be entitled under Gilbert to exclusion of the

identification.

— A-24 —

A. The Failure of the Police to Hold a Lineup Vio

lates Due Process.

The question, therefore, is that left open in Stovall

v. Denno, 388 U.S. 293, 301, 302 (1967), whether the

pre-trial confrontation between petitioner and the

victim “ was so unnecessarily suggestive and con

ducive to irreparable mistaken identification that

[petitioner] was denied due process of law. This is

a recognized ground of attack upon a conviction inde

pendent of any right to counsel claim. Palmer v.

Peyton, 359 F.2d 199 (C.A. 4th Cir. 1966).” The

accused in Stovall was identified without a lineup, a

procedure of acknowledged suggestiveness: “ The

practice of showing suspects singly to persons for the

purpose of identification, and not as part of a line-up,

has been widely condemned” (388 U.S. at p. 302).

Nevertheless, due process was not violated in Stovall

solely because of exigent circumstances. The victim

was in danger of death, and if an identification was to

be made at all “ an immediate hospital confrontation

was imperative” (Ibid.).

The extraordinary need for an immediate identifi

cation without a lineup present in Stovall is com

pletely absent here. On the contrary, at the time of

the identification, Biggers was in police custody on

an unrelated charge and continuously available for

identification. Similarly, Mrs. Beamer was, and had

been for seven months, continuously available to

identify possible suspects. Her health was unimpaired,

and no other factors made an immediate identification

by her without a lineup “ imperative.” Held without

exigent compelling circumstances, Biggers’ showup

identification violated due process under the reason

ing of Stovall v. Denno, supra.

United States v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218 (1967) and

Gilbert v. California, 388 U.S. 263 (1967) found need

— A-25 —

of impartial and selective identification procedures,

and thereby the need for counsel, even when a lineup

is held in part because the reliability of any identifi

cation of a stranger is severely limited by normal

human fallibilities of perception and memory. A

showup, on the other hand, results in the maximiza

tion of suggestion that the suspect is the guilty party

and suggestion is the “ ‘ one factor which, more than

anything else, devastates memory and plays havoc

with our best intended recollections * * V ” Sugges

tion is in large part the product of restricted selec

tivity offered the witness in the identification process.

Instead of being forced to choose between several

persons with different heights, weights, profiles and

voices, Mrs. Beamer was confronted with a single

individual whose suspected guilt the police communi

cated by presenting him alone and in custody. The

witness is free to accept or reject this police judg

ment, but not to choose. With good reason, therefore,

the showup is labelled “ the most grossly suggestive

identification procedure now or ever used by the

police.” Wall, Eyewitness Identification in Criminal

Cases 28. See also, Stovall v. Denno, 388 U.S. 293,

302 n. 5 (1967).

In identifying petitioner, Mrs. Beamer relied par

ticularly on her recollection of a voice she had not

heard in seven months, but selectivity is decreased

even more when identification is by voice. An identi

fication by physical appearance may rest upon various

characteristics, one or a combination of which may be

particularly striking, such as the shape of a nose or

mouth, skin complexion, scars, or height and weight.

Voice identification rests merely upon the tone and

timbre of a voice, as well as an individual’s speech

peculiarities. When few words are spoken and no

special speech peculiarities are present, as in this

— A-26 —

case, only tone and timbre are left to provide identifi

cation. Selectivity is at the barest minimum; the

probability of error is maximized. Biggers, moreover,

spoke softly during the identification (R. 17). It is

difficult to believe the intruder spoke this way during

the assault and rape. The unreliability of voice identi

fications as compared to physical identifications, with

the resultant increased necessity for a lineup, was

recognized by the Fourth Circuit in Palmer v. Peyton,

359 F.2d 199, 201-202 (1966):

“ Where the identification is by voice alone, the

absence of some comparison involves grave dan

ger of prejudice to the suspect, for as one noted

commentator has pointed out: ‘ [E]ven in ordi

nary circumstances one must be cautious and

accept only with reserve what a witness pretends

to have heard * * V ”

This Court rigorously questioned the reliability of

all identification testimony in United States v. Wade,

supra, and quoted with approval Mr. Justice Frank

furter’s observation that: “ The identification of

strangers is proverbially untrustworthy. The hazards

of such testimony are established by a formidable

number of instances in the records of English and

American trials.” The Case of Sacco and Vanzetti

30. If this characterization applies to an identifica

tion by lineup, where comparison and selectivity are

greatest and suggestion minimal, it applies with far

greater force to the showup in this case where Mrs.

Beamer could only accept or reject police suspicion

that Archie Biggers was the rapist, and where the

showup identification was the sole evidence of guilt,

see infra p. 17.

The holding in Stovall that absent unusual circum

stances a show-up violates the due process rights of

— A-27 —

an accused is also soundly rooted in the policy adopted

in United States v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218 (1967) and

Gilbert v. California, 388 U.S. 263 (1967). Those cases

envision that “ presence of counsel itself can often

avert prejudice and assure a meaningful confronta

tion at trial.” (388 U.S. at 236). Suggestion is to be

prevented by an attorney calling the attention of the

police to identification procedures which produce it

and by proposing safeguards. For the attorney to

play a practically meaningful role as insurer of the

integrity of the pre-trial identification proceedings,

practices such as the showup which result in undue

suggestion must be condemned or counsel is reduced

to the role of passive observer, unable to prevent un

reliability and reduced to attempting to expose it

after the fact at trial. I f counsel is unable to assert

that a procedure as destructive of reliability as the

show-up is unconstitutionally suggestive, it is diffi

cult to see how he will be able to assist law enforce

ment as Wade presupposes “ by preventing the in

filtration of taint in the prosecution’s identification

evidence” (388 U.S. at p. 238).

B. The Circumstance of the Identification and Its

Use at Trial Violate Due Process.

This case, however, goes far beyond Stovall, supra.

The record affirmatively shows that petitioner’s iden

tification, and the use made of it by the state, denied

him the fair trial guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment. The circumstances which denied Archie

Biggers due process will be separately examined, but,

of course, their prejudicial impact upon his trial is

cumulative.

First. Prior to the police call “ to look at a sus

pect” Mrs. Beamer was particularly open and sus

— A-28 —

ceptible to suggestive influence. The crime had oc

curred seven months earlier and had lasted at the

most 30 minutes; inevitably the sharpness of her

memory had faded. Mrs. Beamer, by her own admis

sion at trial, was terrified by fear of violence to her

self and children. When asked (R. 14):

Q. “ Are you able to describe this man other

than seeing a butcher knife?”

She replied:

A. “ No, other than I remember the blade being

shiny. ’ ’

The crime took place at night. Mrs. Beamer was

grabbed in an unlit hallway and marched through an

unlit kitchen to railroad tracks and then to a wooded

area. At trial, she gave only a general explanation of

the characteristics which led her to identify peti

tioner. As the Court said in Wade, the danger of sug

gestion is “ particularly grave when the witness’ op

portunity for observation was insubstantial. . . . ”

(388 U.S. at p. 229).

Second. The police suggested that the petitioner

was the rapist when they arrived at Mrs. Beamer’s

home and asked her to go “ look at a suspect.” In

herent in the word “ suspect” was the suggestion that

the police had sufficient evidence linking the petitioner

to the crime to warrant holding him at the police

station for her identification. Thus the normal ex

pectation of a witness that the guilty person will be

present at the identification was substantially in

creased by the police. Cf. Williams, Proof of Guilt, 96.

Third. At the station house Mrs. Beamer first saw

Archie Biggers in the custody of five police officers,

all of whom remained present during the identifica

tion. The sheer number of officers, implying the im

portance of the petitioner as a “ suspect” , may well

have allayed any thought by the witness that this

— A-29 —

might not be “ the man.” On the other hand, the num

ber of officers may have increased her fear of con

tradicting the police as to the identity of a man re

garded by them for reasons unknown to her as a

* ‘ suspect. ’ ’

Fourth. When Mrs. Beamer did not identify Biggers

by his physical appearance, the police required him

to speak words spoken during the attack—“ Shut up

or I ’ll kill you.” —and eventually his compelled

speech was presented to the jury at trial. There is

little that could have been more suggestive of his guilt.

Mrs. Beamer had not indicated that the rapist had

particular speech mannerisms which required those

words to be spoken, and even if he had had speech

peculiarities he could have spoken other sentences of

phrases containing each of these words. Whether or

not a violation of petitioner’s Fifth Amendment

rights (see Argument II, infra) use of the rapist’s

precise words was unnecessarily suggestive.

Wall has evaluated the latter two suggestive tech

niques used in this case. He states that “ As bad as a

show-up is, there are a number of ways it can be made

worse. * * * One method is to point out the suspect to

the witness even before the showup, indicating his

status as suspect. * * * If this practice is not deemed

suggestive enough, then the suspect, when shown

alone, can be required to act or speak in the manner

in which the perpetrator of the crime is supposed to

have acted or spoken, a method adopted for example,

in the Sacco-Vanzetti case.” Eyewitness Identification

in Criminal Cases 30.

Fifth. Archie Biggers was unprepared and un

equipped to protect himself against an identification

made unfair by suggestions to the witness. He was

16 years old, had a ninth grade education, and ap

— A-30 —

parently no previous police record. His immaturity,