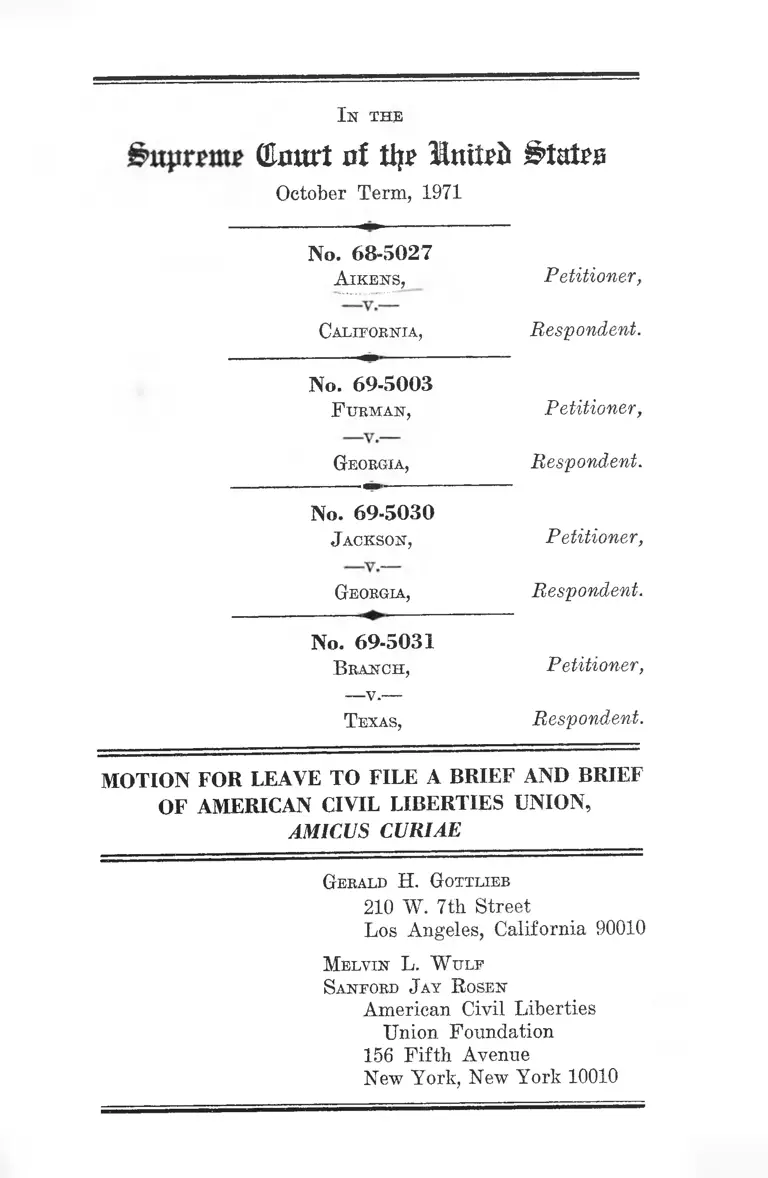

Aikens v. California, Furman v. Georgia, Jackson v. Georgia, and Branch v. Texas Motion for Leave to File a Brief and Brief of American Civil Liberties Union Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Aikens v. California, Furman v. Georgia, Jackson v. Georgia, and Branch v. Texas Motion for Leave to File a Brief and Brief of American Civil Liberties Union Amicus Curiae, 1971. f08c610e-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f293c2fe-305d-41df-b3d2-14ef4ea843e0/aikens-v-california-furman-v-georgia-jackson-v-georgia-and-branch-v-texas-motion-for-leave-to-file-a-brief-and-brief-of-american-civil-liberties-union-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

(Emtrt at % I n M States

October Term, 1971

No. 68-5027

A ikens,

California,

No. 69-5003

F urman,

Georgia,

No. 69-5030

J ackson, Petitioner,

Georgia, Respondent.

No. 69-5031

Branch, Petitioner,

— v .—

T exas, Respondent.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF AND BRIEF

OF AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION,

AMICUS CURIAE

Petitioner,

Respondent.

Petitioner,

Respondent.

Gerald H. Gottlieb

210 W. 7th Street

Los Angeles, California 90010

Melvin L. W ulf

Sanford J ay R osen

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

156 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York 10010

I N D E X

PAGE

Interest of Amicus ................................................ - ....... 6

Summary of Argument.................................................. 6

Argument

Introduction....... ..................... -.... -......................... 7

I. Cruelty and the Lack of a Rational B asis.......... 10

II. Cruelty in Context ............................................... 23

III. Upon Proof of Torture .............................-.......... 40

Conclusion ................................................................................. 42

Appendices

Appendix A

Transcript from the Los Angeles Superior

Court Case of People v. Thornton.................... la

Appendix B

A Brief History of Prisons and Penitentiaries .. 59a

Appendix C

Some Further Glimpses of Capital Punishment:

Father Dingberg and San Quentin Psychiatrist

David G. Schmidt ............................................... 66a

Appendix D

Assertions of Deterrence and the Circularity

of Violence .......................................................... 72a

A p p e n d ix E

Biographies of Non-Legal Authorities 90a

11

Authorities Cited

page

Cases:

Blackburn v. Alabama, 361 U.S. 199 ............................ 20

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 ................. 16

Cox v. State, 203 Ind. 544,181 N.E. 469 ........................ 8

Commonwealth v. Ritter, 13 D. & C. 285 (1930) .......... 10

Dorr v. United States, 195 U.S. 138.............................. 24

Harper v. Wall, 85 F. Supp. 783 (D. N.J.) ................... 33

In re Anderson and Saterfield, 73 Cal. Rptr. 21, 447

P.2d 117 (1968) .......................................................... 9

In re Estrada, 63 Cal.2d 740 (1965) .............................. 13

In re Kemmler, 136 U.S. 436 ......... ........... -........... 12,17, 20

In re Smigelski, 30 N.Y. 513, 154 A.2d 1 (1959) .......... 13

Jordan v. Fitzharris, 257 F. Supp. 674 (N.D. Cal.

1966) ........................................................................... 8,34

Lear, Inc. v. Adkins, 395 U.S. 653 ............ ................... 9

McDonald v. Commonwealth, 173 Mass. 322, 53 N.E.

874 ............................................................................... 34

Mickle v. Henrichs, 262 F. 687 .........,........ -................. -8, 33

Nowling v. State, 151 Fla. 584, 10 So.2d 130............... 34

People v. Aiken, 74 Cal. Rptr. 882 (1969) ..................... 9

People v. Heslen, 163 P.2d 21 (1945) ..................... -...... 13

People v. Ketchel, 59 Cal.2d 50 ........ -.......................... 13

People v. Oliver, 1 N.Y.2d 152,134 N.E.2d 197 (1956) .. 13

Ill

PAGE

People v. Thornton, 73 Cal. Rptr. 21 (1967) ..............passim

Politano v. Politano, 146 Mise. 792, 262 N.Y.S. 802 .... 34

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 ............................ 17

Rudolph v. Alabama, 375 U.S. 889 ................................ 13

State v. Evans, 73 Idaho 50, 245 P.2d 788 ............... ..... 8

State v. Evans, 73 Idaho 349, 121 P.2d 326 ................. 33

State v. Kimbrough, 212 S.C. 348, 46 S.E.2d 273 ..........8, 34

State v. Pugh, 15 Mo. 509 (1851)...................... .......... . 13

State v. Ross, 55 Or. 450, 104 P. 596 ............................ 8, 33

State ex rel. Francis v. Resweber, 329 U.S. 459 ....—17, 28

State ex rel. Garvey v. Whitaker, 48 La. Ann. 527, 19

So. 457 (1896) ....................................... ..................... 8, 34

Stephens v. State, 73 Okla. Cr. 349, 245 P.2d 788 ...... 33

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 .................... 8,12,14,17, 20,

40, 41, 42, 43

United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U.S. 144 .... 16

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 ........ 8,11,12, 24, 33

Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130 ............................ ..12, 29, 42

Williams v. Field, 416 F.2d 483 (9th Cir. 1969) .......... 34

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510................. .......... 19

Workman v. Commonwealth, 429 S.W.2d 374 (Kv.

1968) .................................... ...................................... 8,29

Constitutional Provisions:

United States Constitution

Sixth Amendment................................. .............. 43

IV

PAGE

Seventh Amendment

Fourteenth Amendment........................................... 24

State Statute:

Cal. Ev. Code Section 452(g) (h) ............................ 9

Other Authorities:

The English Bill of Rights of 1689, 1 W. & M. 2,

c. 2 S 10.................. ...................................-----.......... 11

2 Story, J., Commentaries on the Constitution 623

(1873) ......... ................ ........... ...............- - ............. . U

Holmes, The Common Law 42 .................................... 13

Cohen, M. R., Law and the Social Order 310................ 13

Michael and Wechsler on Criminal Law and Its Ad

ministration 6 (1940) ................................................ 13

Ramsey Clark: “Modern penology with all its correc

tional rehabilitation skills affords greater protection

to society than the death penalty which is incon

sistent with its goals.” Speech, July, 1965 ..... ........ 14

Sellin, Capital Punishment (1967) ..............16, 30, 31, 32, 38

Eshelman, Death Row Chaplain 160 (Prentice 1962) .... 18

Dostoevsky, The Idiot 19 .............................................. 19

West, Scientific Reflections on the Death Penalty,

Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions,

Santa Barbara, California 1967 ................................ 21

Duffy, Warden Clinton T., The San Quentin Story 81

(1951) ....................................................................... 21

Cobin, Herbert L., “Abolition and Restoration of the

Death Penalty in Delaware”, The Death Penalty in

America, ed. Hugo Bedau (Chicago, 1964) 366 ...... 23

V

PAGE

Duffy, Clinton T., 88 Men. and Two Women....... ..........35, 40

Beccaria, Cesare, “On the Death Penalty”, from 1764

Treatise, Dei Delitti E Delle P ens .......................... 29, 30

California Legislature Assembly Committee on the

Administration of Justice, Report 3 (1970) ............31,32

Sutherland and Cressey, Principles of Criminology

292 (1955) ............................................. 31,32

Schuessler, “The Deterrent Influence of the Death

Penalty,” 284 Am. Journ. Pol. and Soc. Sci. 54

(1952) ................................................ 31

Gibbs, Suicide 517 (1968) ...............................................31,32

Bedau, The Death Penalty in America 399 (1967) ___ 32

Filler, “Movements to Abolish the Death Penalty in

the United States” ............................. ,....................... 38

Dickens, “Letter to M. de Cerjat, December, 1849” .... 38

Cong. Beg. 225 (1791) .................................................. 11

55 Col. L. Bev. 1039 ....................................................... 13

31 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1378 .................................................. 13

36 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 110 .................................................... 13

34 So. Cal. L. Bev. 286 .................................................. 13

I?r th e

(Emul at tl|? InttTft States

October Term, 1971

No. 68-5027

A iken'S,

----v .—

Petitioner,

California, Respondent.

No. 69-5003

F urman, Petitioner,

Georgia, Respondent.

No. 69-5030

J ackson,

----V,----

Petitioner,

Georgia, Respondent.

No. 69-5031

Branch,

—v.—

Petitioner,

Texas, Respondent.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF OF

AMERICAN QVIL LIBERTIES UNION AS

AMICUS CURIAE

2

It is hereby respectfully moved pursuant to Rule 42 of

the Rules of this Court that the above named amicus

curiae be granted leave to file the accompanying brief in

support of the Petitioners.

Consent to such filing has been requested and had been

granted on behalf of the Petitioners Aikens, Furman, and

Jackson, and for the Respondent State of California.1

Counsel for Petitioner Branch has indicated that he will

not oppose Amicus's motion, but he declined to provide

his consent prior to review of Amicus’s brief. Consent

has been refused by Respondents, State of Georgia and

State of Texas. (Copies of the page proofs of this brief

were sent by first class mail to the counsel for each Re

spondent on August 27, 1971, the date the Petitioners’

briefs were filed.)

The interest of the amicus curiae as stated in the accom

panying memorandum is as follows:

The American Civil Liberties Union, with affiliates in

most states, including California, Georgia and Texas, is

a private, non-partisan organization, consisting of 160,000

members, which is engaged exclusively in defense of the

Bill of Rights. The Eighth Amendment to the Constitution

prohibits the infliction of “cruel and unusual punishments.”

We believe that execution for crime is a “cruel and unusual

punishment.” As an organization, we seek elimination of

capital punishment throughout the United States. In this

sense, the amicus curiae has a wider stake in the issue

presented in these cases than do the Petitioners. In the

accompanying brief and appendixes, the amicus curiae has

marshalled the best historic and social scientific evidence

_ 1 These letters of consent have been filed with the Clerk. Both

sides have consented to amicus curiae’s filing of a brief in the

Aikens case.

3

bearing on the wider issue of the overall “cruel and un

usual” character of capital punishment, thereby providing

for the Court the wider context within which these cases

should be considered.

Respectfully submitted,

Gerald H. Gottlieb

210 W. 7th Street

Los Angeles, California 90010

Melvin L. WVi.f

Sanford J ay R osen

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

156 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York 10010

1st the

Bnprtnw (Emirt of tip? In M

October Term, 1971

No. 68-5027

A ikens, Petitioner,

—v.—

California, Respondent.

No. 69-5003

F urman,

—v.—

Georgia,

No. 69-5030

J ackson,

Georgia,

No. 69-5031

Branch, Petitioner,

—v.—

Texas, Respondent.

Petitioner,

Respondent.

Petitioner,

Respondent.

BRIEF OF AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION,

AMICUS CURIAE

6

In te re st o f Am icus

The American Civil Liberties Union, with affiliates in

most states, including California, Georgia and Texas, is a

private, non-partisan organization, consisting of 160,000

members, which is engaged exclusively in defense of the

Bill of Bights, The Eighth Amendment to the Constitution

prohibits the infliction of “cruel and unusual punishments.”

We believe that execution for crime is a “cruel and unusual

punishment” and for that reason file this brief to present

argument in support of that principle.

Sum m ary o f A rgum ent

Three paths of reasoning lead to the same conclusion:

the death penalty is unconstitutional under the Eighth

Amendment prohibition of cruel and unusual punishments.

I. The cruel and unusual punishments clause requires

that all penal sanctions which are cruel, albeit not

so severe as to be torture, be rationally related to

a legitimate state objective in the administration of

the penal law. If the petitioners show that the death

penalty is cruel and that there is no basis in human

reason to believe that the death penalty serves a

permissible objective of punishment, then capital

punishment must be held unconstitutional.

II. The cruel and unusual punishments clause is a fun

damental protection of individual rights. The wide

spread disenfranchisement and extreme isolation of

prisoners on death rows prevents the condemned

man from effectively appealing to majoritarian in

stitutions for enforcement of his constitutional

7

rights. It is the Court’s duty to exercise the most

rigid scrutiny in this case.

A. The death penalty, clearly suspect under the

Eighth Amendment, is unnecessary in a so

ciety with adequate alternative means of ful

filling the legitimate objectives of the penal

law. It is therefore unconstitutional.

B. The death penalty and the necessarily asso

ciated experience of death row shocks and

devastates the consciences of civilized men.

It is therefore unconstitutional.

III. The cruel and unusual punishments clause prohibits

the torture of persons convicted of crimes. If the

petitioner sustains the burden of proving that the

death penalty constitutes torture, capital punish

ment must be held unconstitutional.

A R G U M E N T

Introduction

Amicus notes the policy of this Court scrupulously to

avoid overstepping the bounds of its province of constitu

tional review. Conversely it is recognized that when

fundamental rights guaranteed to the people by the Con

stitution are threatened, this Court forcefully acts to pro

tect the Nation’s constituted plan. In the cases before the

Court questioning the constitutionality of the death penalty

under the “cruel and unusual punishments” clause of the

Eighth Amendment, an issue is presented which deserves

careful scrutiny. Although the fixing of limits upon pen

alties for crimes is usually a legislative function, there

8

have been eases in which this Court and inferior tribunals

have declined to give unrestrained deference to legislatures

—where matters such as the fundamental protection against

cruel and unusual punishments are threatened.2

This Court has not heard or decided the question of the

constitutionality of the death penalty under the Eighth

Amendment. That question is a narrow one; the wider

question of the wisdom of capital punishment is not the

focus of this brief.

While narrow, the scope of the constitutional question

does not prevent a proper disposition of that question. Any

overcurtailment of the scope of the review could render the

pointed and economical language of the Eighth “mere sur

plusage.”

Reference is made to the testimony of certain experts

in the fields of criminology and sociology,3 psychiatry,4

penology,5 and medicine and other professionals attached to

2 Weems v. U. 8., 217 U.S. 349 (1910) (cadena temporal) ;

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958) (de-nationalization) ; Work

man v. Commonwealth, 429 S.W.2d 374 (Ky. 1968) (life applied

to juvenile) ; State v. Evans, 73 Idaho 50, 245 P.2d 788 (life for

lewd conduct); Cox v. State, 203 Ind. 544, 181 N.E. 469; State

v. Ross, 55 Or. 450, 104 P. 596; Jordan v. Fitzharris, 257 F.

Supp. 674 (N.D. Cal. 1966) (solitary confinement in inhuman

conditions) ; State ex rel. Garvey v. Whitaker, 48 La. Ann. 527,

19 So. 457 (1896); State v. Kimbrough, 212 S.C. 348, 46 S.E.2d

273 (30 yrs. for burglary) ; Mickle v. Henrichs, 262 F. 687

(vasectomy).

3 Thorsten Sellin, Emeritus Professor of Sociology, University

of Pennsylvania.

4 Louis .Jolyon West, M.D., Chief of Neuropsychiatry, UCLA

Medical Center.

5 Clinton F. Duffy, former Warden San Quentin Penitentiary.

9

the prison6 in the ease of People v. Thornton, Superior

Court, Los Angeles County, 1967, a collateral proceeding,7

as well as books and journals.

6 Father Edward J. Dingberg, Roman Catholic Chaplain,

Byron Eshelman, Protestant Chaplain, William Graves, M.D.,

physician.

7 There is precedent for expanding the meaning of “record” be

yond its narrowest meaning. In Lear, Inc. v. Adkins, 395 U.S. 653

(1969), Mr. Justice Harlan for the majority recognized the inade

quacy of review by this Court, were it not to encompass what the

state supreme court’s opinion considered. Adkins submitted evi

dence of an agreement relating to a patent—which was not in evi

dence in the trial court—to the California Supreme Court.

“Lear argues that this original agreement was not submitted

in evidence at trial and so should not be considered a part of

the record on appeal. The California Supreme Court, however,

treated the agreement as an important part of the record be

fore it, 67 Cal.2d at 906, 435 P.2d at 335, and so we are free

to refer to it,” 23 L. Ed.2d at 615 fn. 1.

In the California Supreme Court opinion in the present case,

reference was made to the disposition of the issue of the constitu

tionality of the death penalty in a prior ease before the California

Supreme Court, People v. Aiken, 74 Cal. Rptr. 882 at 889 (1969).

The opinion of the California Supreme Court in that prior case,

In re Anderson and Saterfield, 73 Cal. Rptr. 21, 447 P.2d 117

(1968), makes extensive reference to the brief filed by amicus

curiae for that case and to the transcript from the Los Angeles

Superior Court case of People v. Thornton (1967), 73 Cal. Rptr.

21 at 33, 34, 35, which are referred to in this brief. (Admissibility

of the social science evidence before the California courts is pro

vided under Cal. Ev. Code Section 452(g) (h) and the official

Assembly Committee comment therein.)

A thorough review of the California Supreme Court holding in

People v. Aiken, the case now before this Court, properly includes

review of the transcript from People v. Thornton and the social

science issues raised in the amicus brief before the Court in In re

Anderson and Saterfield.

10

I.

C ruelty and th e Lack o f a R ational Basis

A. T he Death P enalty and P ermissible

Objectives oe the P enal L aw

The cruel and unusual punishments clause requires that

all penal sanctions which are cruel, albeit not so severe as

to be torture, be rationally related to a legitimate state

objective in the administration of the penal law. If the

petitioner shows that the death penalty is cruel and that

there is no basis in human reason to believe that the death

penalty serves a xiermissible objective of punishment, then

capital punishment must be held unconstitutional.

What are the permissible objectives of the penal law!

The Roman statesman and lawyer, Seneca, stated then

succinctly in theory: “The law in punishing wrong aims at

three ends—either that it may correct him whom it

punishes, or that his punishment may render other men

better, or that, by bad men being put out of the way, the

rest may live without fear.” 8 Enlightened men have long

recognized the cruelty of the motive of revenge. Plato,

speaking through Protagoras, observed, “No one punishes

those who have been guilty of injustice solely because they

have committed injustice, unless indeed he punishes in a

brutal and unreasonable manner. When anyone makes

use of his reason in inflicting punishment, he punishes not

on account of the fault that is past, for no man can bring it

about that what has been done may not have been done, but

on account of a fault to come, in order that the person

punished may not again commit the fault and that his

8 Quoted in Commonwealth v. Bitter, 13 D. & C. 285 (1930).

11

punishment may restrain from similar acts those persons

who witness the punishment.” 9

The maturation and implementation of the doctrine

occurred in the context of the evils against which it is

directed. Penal practices of various societies in history

indulged the objective of revenge; tortures such as the

rack, pillory, and thumbscrew existed until the recent past.

Revenge through torture reached its zenith in England

during the Stuart reign, and was perfected in burnings at

the stake, breaking on the wheel, boiling in oil, drawing and

quartering, and other ghastly acts. The English Bill of

Rights of 1689 was a response to the atrocities;10 therein

the phrase “cruel and unusual punishments” first appeared.

The same phrase in the Eighth Amendment to the Con

stitution apparently was an adoption from the English

Declaration j11 the wording is exact.

The debate in the Congress upon the proposed amend

ment included the objection of Mr. Livermore and fore

shadowed the present case that comes nearly two centuries

later. Said Mr. Livermore to his Congressional colleagues

at work on the Eighth Amendment:

“It is sometimes necessary to hang a man, villains often

deserve whipping and perhaps having their ears cut

off; but are we in the future to be prevented from in

flicting these punishments because they are cruel?”

Cong. Reg. 225 (1791)

9 Ibid.

101 W. & M. 2, c. 2 S 10; see Weems v. United States, 217 U.S.

349 (1910), and the dissenting opinion at 395-400; cf. 2 J. Story,

Commentaries on the Constitution 623 (1873).

11 Ibid.

12

It was in the face of this objection that the Congress, and

the states, passed and ratified the Eighth Amendment.12

Some courts and commentators have maintained that it

was aimed solely at the practices of the Stuart regime in

England.13 This ignores what this Court said in Weems

after noting the Livermore colloquy:

“Legislation . . . should not, therefore, be necessarily

confined to the form that evil had theretofore taken.

Time works changes, brings into existence new con

ditions and purposes. Therefore, a principle to be vital

must be capable of wider application than the mischief

which gave it birth.” Weems v. United States, 217 U.S.

349 (1910).

A half-century later, this Court said: “The words of the

[Eighth] amendment are not precise, and . . . their scope

is not static. The Amendment must draw its meaning from

the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress

of a maturing society . . . ” Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86,

(1958).

In both the English and American bills of rights, the

cruel and unusual punishments clause is inextricably asso

ciated with clauses prohibiting excessive fines and excessive

bails.14 A punishment that is excessively severe is one that

12 Weems v. U. S., 217 U.S. 349, 369 (1910).

13 In re Kemmler, 136 U.S. 436, 446-447 (1890).

14 “But it is safe to assume that punishments of torture, such as

those mentioned by the commentators referred to [Cooley,

Const. Lim. 4th Ed. 408 ; Wharton, Cr. L. 7th Ed. §3405] and

all others in the same line of unnecessary cruelty, are forbid

den . . . ” by the Eighth Amendment, Wilkerson v. Utah, 99

U.S. 130, 136.

“Torture is defined to be torment, judicially inflicted; pain by

which guilt is punished or confession extorted; anguish; ex-

13

imposes retribution. The historical anod textual context of

the Eighth Amendment as well as the Congressional intent

as exemplified by Mr. Livermore’s contention, are all in

corporated in the interpretation of the amendment that sees

revenge as an impermissible objective of punishment.

Leading modern state courts agree that revenge is not a

proper function or objective of state power.15 The Supreme

Court of California has held that lighter punishment pre

scribed by the legislature subsequent to the criminal act

but before final judgment should prevail as against the

heavier, previously prescribed punishment, In re Estrada,

63 Cal. 2d 740, 745 (1965) and in explanation quoted from

the similar New York case of People v. Oliver, 1 N.Y.2d 152,

134 N.E.2d 197, 201 (1956), where Judge Fuld said:

“According to the best modern theories concerning the

functions of punishment in criminal law, the punish

ment or treatment of criminal offenders is directed

toward one or more of three ends: (1) to discourage

and act as a deterrant upon future criminal activity,

(2) to confine the offender so that he may not harm

society, and (3) to correct and rehabilitate the offender.

There is no place in the scheme for punishment for its

treme pain; anguish of body or mind”, State v. Pugh, 15 Mo.

509 (1851).

“Torture is the act or process of inflicting pain, especially as a

punishment or in order to extort confession or in revenge”,

People v. Ileslen, 163 P.2d 21 (1945).

15 See also: Rudolph v. Alabama, 375 U.S. 889 (dissenting opin

ion of Justice Goldberg), In re Smigelski, 30 N.Y. 513, 154 A.2d 1

(1959) ; People v. Ketchel, 59 Cal.2d 50; Holmes, The Common Law

42, 46; M. R. Cohen, Law and the Social Order 310; Michael and

Weehsler on Criminal Law and Its Administration 6 (1940) ; 55

Col. L. Rev. 1039, 1052; 34 So. Cal. L. Rev. 286; 36 N.Y.U. L. Rev.

110, 117; 31 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1378, 1381.

14

own sake, the product simply of vengeance or retri

bution.”

Mr. Justice Brennan, concurring in Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S.

86, expressed similar sentiments.

B. T he Death P enalty I s U nrelated to P ermissible Ob

jectives.

Having established the permissible objectives of pun

ishment in the context of the Eighth Amendment, the ques

tion then is whether the death penalty is rationally

connected to one or more of those objectives, namely, de

terrence of future crime, isolation of dangerous individuals

from society, or rehabilitation of criminal personalities.

It is obvious that death can in no way rehabilitate.

While death does “isolate” a dangerous individual from

doing further harm, it is manifest that imprisonment for

life accomplishes the same end equally well.16 Life im

prisonment affords an opportunity to rehabilitate. It does

not entail irretrievable decisions as to guilt as does the

death penalty. Life imprisonment avoids presenting physi

cal violence of the state as an official example.

There is no evidence that the death penalty offers any

additional deterrence over and above imprisonment. This

is made clear in the testimony of the criminologists and

psychiatrists who testified in the Thornton trial (Appendix

A) and in the fact brief on the subject of deterrence (Ap

pendix D) which reviews the published works of the major

authorities on that subject in the United States.

18 Kamsey Clark: “Modern penology with all its correctional re

habilitation skills affords greater protection to society than the

death penalty which is inconsistent with its goals.” Speech, July,

1965.

15

Briefly, the uncontroverted evidence—largely statistical

—shows that no lowering of the criminal homicide rate

occurs in those states in which the death penalty is a punish

ment for murder as compared to those States which do not

provide the death penalty ;17 there is no evidence of greater

incidence of criminal homicides committed on police or

prison guards in States that have abolished the death

penalty as compared to States that have retained it ;18 com

parisons between neighboring states with similar cultural

and ethnic characteristics show no significant difference in

criminal homicide rates resulting from one of the states

retaining capital punishment and the other state having

abolished it;19 in states which have abolished and then re

stored, or restored and then abolished capital punishment,

no significant change has occurred in the criminal homicide

rate, and similar findings have been reported for entire

nations;20 increases in homicide rates are associated with

the days immediately following well-publicized acts of

violence, including executions ;21 and reduction of the rate

of criminal homicides depends on factors other than the

presence of the death penalty.22

“[T]he constitutionality of a statute predicated upon the

existence of a particular state of facts may be challenged by

a showing to the court that those facts have ceased to exist.”

17 See Appendix D, pp. 73a-74a.

18 See Appendix D, pp. 79a-83a.

19 See Appendix D, p. 78a; Appendix A, Testimony of Thorsten

Sellin, People v. Thornton, 9a-10a.

20 See Appendix D, pp. 74a-76a.

21 See Appendix D, pp. 86a-89a.

22 See Appendix D, pp. 72a-86a.

16

U. S. v. Carotene Products Co., 304 U.S. 144 (1938); see

also Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 489 f .4, 494

f.ll. (1954). In view of this contemporary uncontroverted

evidence, it is emphasized that no state of facts, either

known or which could reasonably be assumed, affords sup

port for the proposition that the death penalty is a deter

rent to the kinds of crimes for which it is the punishment, as

opposed to imprisonment. Clearly, then, the death penalty

does not serve the objectives of rehabilitation, isolation or

deterrence.23

C. T he Contemporary Context of J udicial Review of

Death P enalty Statutes: New Developments

The death penalty has been referred to by this Court—in

occasional dicta—as constitutionally permissible. (We

stress that no decision has been made under the Eighth

23 Thorsten Sellin, eminent sociologist and penologist and fore

most authority in his field on the issue of deterrence and the death

penalty:

“I have attempted to show that, as now used, capital punish

ment performs none of the utilitarian functions claimed by its

supporters, nor can it ever be made to serve such functions.

It is an archaic custom of primitive origin that has disappeared

in most civilized countries and is withering away in the rest.

“If an intelligent visitor from some other planet were to

stray to North America, he would observe, here and there and

very rarely, a small group of persons assembled in a secluded

room who, as representatives of an all-powerful sovereign

state, were solemnly participating in deliberately and artfully

taking the life of a human being. Ignorant of our customs, he

might conclude that he was witnessing a sacred rite somehow

suggesting a human sacrifice. And seeing our great universi

ties and scientific laboratories, our mental hospitals and clinics,

our many charitable institutions, and the multitude of churches

dedicated to the worship of an executed Saviour, he might well

wonder about the strange and paradoxical workings of the

human mind.” Sellin, Capital Punishment (1967), p. 253.

17

Amendment.)24 What, within the court’s competence, is

different now from when these comments were made and

from when the Eighth Amendment was ratified?25

First, at the time of ratification of the Bill of Rights, the

penal system in America was poorly developed.26 Of the

legitimate ends of penal administration, the objective of

isolation of dangerous individuals from societj7 could only

be effectively furthered by the execution of dangerous indi

viduals. At common law, all felonies were punishable by

death (probably in part for this reason) and in the United

States at the time of ratification, numerous crimes were

still punishable by death. Since ratification, our penal sys

tem has developed into a reliable institution, effective in

removing dangerous individuals from society.

Second, reliable empirical information about the death

penalty in terms of its cruelty,27 its actual effect as a

24 Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86; State ex rel. Francis v. Besweber,

329 U.S. 459; In re Kemmler, 136 U.S. 436.

25 The most obvious new development, of course, is the 1962 hold

ing of this Court in Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660, that for

the first time made the Eighth Amendment’s commands applicable

to the States.

26 See Appendix B, pp. 59a-65a, a short history of prisons.

27 Testimony of Dr. Louis Jolyon West, People v. Thornton, re

produced in Appendix A infra, pp. 40a-41a, is cogent here:

“Q. Have you had occasion to consider the relationship be

tween physical and mental pain, that is, between the impact

of stress on the body as such and that of stress, fear, the ex

pectation of death, the anxieties involved on the other—have

studies been made that would shed light on the relationship

between these two phenomena? And if so, are you familiar

with these studies? A. Yes, I am familiar with those studies.

I have carried out such studies myself. It is possible to meas

ure the degrees of intensity of physical pain through the use

of objective instrumentation. The Hardy-Wolff-Goddell ap-

18

paratus for measuring the intensity of noxious stimulation and

the subjective responses to it, make it possible to define ap

proximately 21 increments of discernible change and pain ex

perience. These have been put together into a scale, a so-called

Dol Scale, which has ten and a half points, each containing

two increments. When you reach ten and a half Dols of pain

ful stimulus, it can’t hurt any more than tha t; that’s the maxi

mum amount of pain a person can feel, and increasing the

amount of painful stimulation, whether it be burning or pres

sure on the bone and so on, does not produce an additional

degree of pain. It has been my experience that certain indi

viduals who are actually subjected to torture, knowing about

this and having been engaged in such experiences, as in a

laboratory—I am thinking now here of certain physicians who

were trained with Dr. Wolff and then who were subsequently

captured, first by the Japanese and later in Korea, and sub

jected to some very painful stimulation, found comfort in the

knowledge that things could only hurt so much. Biologically

there was a limit, and they knew what that limit vcas and

were able to endure.

Whereas in the psychological sphere, the type of anguish

that comes from knowledge that there are others in whose

hands we are helpless, who will when the time comes destroy

us, doesn’t seem to have any limit; there is no way to measure

it; and I would regard such torture as more severe than any

thing that could be inflicted by thumb screws, racks, or pain

machines of the kind we use in the laboratory.

Q. To what extent, Doctor, in your professional opinion, can

the application of the mental stress, the mental pain that you

have mentioned, be a factor in causing insanity? A. Well, I

believe that it can be causative of mental illness either tem

porarily or permanently, and that this indeed takes place in

Death Row types of situations all the time. That doesn’t mean

in all cases, but that it is going on all the time, as long as

you’ve got a Death Row . . . ”

Chaplain Byron E. Eshelman, Supervising Chaplain at San Quen

tin Prison, 1951-present, describes the execution of Leandress Riley:

“A guard unlocked his cell. He gripped the bars with both

hands and began a long shrieking cry. It was a hone chilling,

wordless cry. The guards grabbed him, wrested him. violently

away from the bars. The old shirt and trousers wrere stripped

off. His flailing arms and legs were forced into the new white

shirt and fresh blue denims. The guards needed all their

strength to hold him while the doctor taped the stethoscope in

place. The deep-throated cry, alternating with moaning and

shrieking, continued. Leandress had to be carried to the gas

chamber, fighting, writhing all the way.” Eshelman, Death

Bow Chaplain 160, Prentice 1962.

19

deterrent,28 and its side effects on the society,29 was virtu

ally non-existent in the last century. As the sciences of

criminology, penology, psychology, psychiatry, and soci

ology have developed increasingly reliable indices of human

behavior, social scientists have turned their attention to

the institution of capital punishment and its effects upon

the convict and his society. What they have illumined is

an evil so monstrous in its effects on the convict and society

that Arthur Koestler has said that whether one approves

of capital punishment is the “test of one’s humanity . . . .” 30

Third, very recent developments in the protection of

individual rights of the accused and increased safeguards

from executions by mistake have enlarged the right of

appeals and necessarily extended the time between

sentencing and death. The mental torture of death row is

an inseparable part of the death penalty today.31 Earlier

decision-making by courts has not had the institution of

death row and its implications to consider.

Fourth, as noted in the Introduction, supra, the concept

of judicial notice has expanded so that evidence of social

sciences is now within the scope of a court’s scrutiny.32

28 See Appendices A and D.

29 See Appendix D, pp. 86a-92a.

30 Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968).

31 “But the chief and worst pain may not be in the bodily suf

fering but in one’s knowing for certain that in an hour, and then

in ten minutes, and then in half a minute, and then now, at the

very moment, the soul will leave the body and that one will cease

to be a man and that that’s bound to happen; the worst part of

it is that it’s certain. . . . To kill for murder is a punishment in

comparably worse than the crime itself.” Dostoevsky, The Idiot

19. See also Appendix C.

32 See note 7, supra.

20

Fifth, in line with developing information now available

through the social and psychiatric sciences, courts have

been giving increasing attention to mental suffering as a

cruelty in and of itself.33 Simultaneously, the proliferation

of lengthy waits on death row have created extreme mental

problems in prisoners awaiting execution or reprieve.

Because of the requirement that the condemned be

legally sane at the time of his execution, it is not uncommon

for inmates of the row to be removed for psychiatric treat

ment (including extensive electric shock therapy) to restore

them to their senses for their execution (an indication of

the intention of the State to prevent the condemned, if

possible from escaping into insanity).84 Here, then, is “some

thing more than the mere extinguishment of life.” 35 The

mental anguish and suffering inflicted on a convict waiting

33 f r0p y Billies, 356 U.S. 86 (1958):

“Since Chambers v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227, 84 L. Ed. 716, 60

S. Ct. 472, this court has recognized that coercion (of con

fessions) can be mental as well as physical, and that the blood

of the accused is not the only hallmark of an unconstitutional

inquisition. A number of cases have demonstrated, if demon

stration were needed, that the efficiency of the rack and thumb

screw can be matched, given the proper subject, by more

sophisticated modes of persuasion.” Blackburn v. Alabama,

361 U.S. 199 (1960).

34 There have been persons on Death Row who needed psychiatric

treatment and who were removed from Death Row to the hospital

for psychiatric treatment, including electric shock, to remove

borderline mental illness so that they could be returned to Death

Row so that they would know what was happening to [them]

when [they were] being executed. Approximately two dozen men

have been so treated. The prisoner must know the crime he com

mitted for which he is sentenced to execution. Summary of

Testimony, Dr. Schmidt, San Quentin Prison State Psychiatrist,

in People v. Thornton, R.T. 394, 396-397, 400.

35 In re Kemmler, 136 U.S. 436 (Dictum) :

“A good many of these doomed men end up in the hands

of the psychiatrist. The strain of existence on Death Row

21

D. I rrationality and U nconstitutionality

The death penalty, arguendo, may have been legitimate

in times past, when alternative means of isolation were

unavailable or unreliable, when ideas of its deterrent effect

were based solely upon intuition in the absence of any

sociological evidence whatsoever, when judges were unable

to base decisions on social sciences, when execution was

is very likely to produce behavioral aberrations ranging from

malingering to acute psychotic breaks. In most states the

warden will transfer such a person to the psychiatric unit of

the prison or the security area of a mental hospital. Here the

prisoner is not unlikely to pass the rest of his days as a mem

ber of that vaguely defined population, ‘the criminally in

sane.’ ”

West, Scientific Reflections on the Death, Penalty, Center

for the Study of Democratic Institutions, Santa Bar

bara, California, 1967.

Warden Clinton T. Duffy, San Quentin Prison 1940-1951:

“Once in a while, under the pressure of a tremendous fear, a

condemned man loses his mind before execution time. The

California law holds that no man can be put to death unless

he knows why his life is being taken and understands the dif

ference between right and wrong. In short, he must be legally

sane. There is a grim irony in this stipulation, because uurmg

those last dreadful hours of suspense the responsibility for

gauging a man’s mind and his thoughts lies with me. How

can I know when a man is insane! Is he insane because he

will not eat or sleep or because he talks hysterically? Is he

insane because he behaves strangely in the face of death? I

don’t know.” Duffy, Warden Clinton T., The San Quentin

Story 81 (1951).

Joseph D., Lohman, Dean of the School of Criminology, Uni

versity of California, 1961-1970:

“When sheriff of Cook County (Chicago), Illinois, I had occa

sion to observe the day-to-day life of inmates on Death Row.

I visited the Death Row at the Cook County jail sometimes

daily, never less than once or twice a week. I observed evi

dence of anguish on the part of inmates of Death Row, as

well as evidence of mental' illness. I was advised of attempted

suicides, and we kept a constant twenty-four-hour guard on

22

swift, sparing the condemned the anomie of death row,

when onr knowledge of the human psyche and its infinite

capacity for mental anguish was primitive.86 Perhaps in an

earlier century there was a basis in human reason for a

legislature to believe that the death penalty served the

legitimate penal ends of isolation and deterrence without

unnecessary cruelty. But times have changed, and such

cannot be said today.37 The death penalty is cruel in view

of such factors as the physical and mental anguish of 1,000

days on death row and the execution transaction, and serves

only the illegitimate penal objective of revenge or retribu

tion. It ought therefore to be held unconstitutional.

duty with a view to avoiding that eventuality. There was a

disposition toward suicide by some of the inmates.

I observed changes in the mental condition of inmates on

Death Eow. Some of those changes were physical deteriora

tion of the men, rejection of food, withdrawal of the men,

plaintive and almost childlike pleas, progressing and develop

ing as execution date approached; the complete disintegration

of the personality of the individual.

The sequence of events started with an unbelief that this

could have happened to them and that some agency would

intervene to upset the whole procedure, desperate, plaintive

pleas for help, development of psychosomatic or psychological

care and administration which attained a more frequent and

finally the complete withdrawal of the individual, quite often

huddling in a corner, unable to locomote even about the cell

in many cases.” Summary of Testimony, Dean Lohman, in

People v. Thornton, E.T. 583, 585.

36 See fn. 27, supra.

37 Some legislatures have abolished the death penalty only to

reinstitute it at a later date. Frequently, the re-institution of

capital punishment is provoked by a notorious and heinous crime,

and is legislated with dismaying swiftness. In Delaware, for ex

ample, the cruel beating and murder of an 89 year old woman in

1961 led to a bill which re-instituted the death penalty. State

Senator James H. Snowden of Wilmington declared it to be

“panic legislation” that was motivated by emotion and revenge,

but the bill passed nevertheless over the veto of Governor Elbert

23

II.

C ruelty in Context

The Cruel and Unusual P unishments Clause I s a F unda

mental P rotection oe I ndividual R ights. T he W idespread

Disenfranchisement and E xtreme I solation of P risoners

on Death R ows P revents the Condemned Man F rom

E ffectively Appealing to Majoritarian I nstitutions for

E nforcement of H is Constitutional R ights. Scrutiny I s

T herefore R equired, Guided by the F ollowing:

A. The Death P enalty, Clearly Suspect U nder the

E ighth A mendment, I s U nnecessary in a Society W ith

Adequate Alternative Means of F ulfilling the

Legitimate Objectives of the P enal L aw. I t I s T here

fore Unconstitutional.

B. T he Death P enalty and the Necessarily A ssociated

E xperience of Death R ow Shocks and Devastates the

Consciences of Civilized Men . I t I s T herefore Un

constitutional.

N. Carvel. In returning the bill to the legislature, Governor Carvel

remarked, “The lack of useful purpose of the death penalty has

been the basis for the almost universal condemnation of its use

by the church bodies in the United States and throughout the

world upon the ground that revenge and brutality can have no

place in a morally oriented society and that society can be pro

tected by other means than the taking of a human life . . . The

function of the criminal law is to protect the law-abiding

and not to fulfill a lust for revenge. Anything that tends to asso

ciate the law with the idea of vengeance impairs its dignity and

subtracts from the aspect that intelligent people accord it.” In

Herbert L. Cobin, “Abolition and Restoration of the Death Penalty

in Delaware”, The Death Penalty in America, ed. Hugo Bedau

(Chicago, 1964) pp. 366-371.

24

A. F undamental P rotection

The Eighth Amendment occupies a fundamental place in

the American system as a protection of individual liberties

against the evils of unlimited government. The rule of

civilized law requires limits upon government and the

Eighth Amendment is one of them. The cruel and unusual

punishments clause has been a fundamental guarantee of

the Anglo-American legal system since 1689 and, as such,

deserves nothing less than vigorous enforcement.

In 1904, the Court had held that only the most funda

mental provisions of the American Bill of Bights applied

to an unincorporated territory. Dorr v. United States, 195

U.S. 138. Six years later in Weems, the Court applied the

cruel and unusual punishment principle to the unincor

porated Philippine territory, considering the provision to be

“essential to the rule at law and the maintenance of indi

vidual freedom,” 217 U.S. 349, 367.

Thus, the Eighth Amendment is a fundamental protection

of individual rights, now embraced by the Fourteenth

Amendment, and effective upon State as well as territorial

governments, and, “essential . . . to individual freedom.”

B. Cruelty

The death penalty is substantially different from all

other penalties commonly imposed upon criminals. Its

uniqueness is partly in its inherent destructiveness of the

high objective of criminal sanctions—rehabilitation. The

1,000 or more days of tension, anxiety, and mental torture

on death row constitute an experience inseparable from the

execution itself.

Dr. Louis Jolyon West, an eminent psychiatrist, has

testified as to the mental torture of the death row ex-

25

perienee.38 After testifying that mental pain has no limit

within the knowledge of his discipline whereas there is a

definite and scientifically measurable limit to physical pain,39

Dr. West compared the two:

“Q. Does that mean that any conclusion can be

drawn as to the comparative relationship between that

physical pain which might be induced by physical

torture and, on the other hand, a mental pain which

might be induced by the pendency of death, one or the

other? A. What it suggests is that ultimately at least

the degree of suffering involved in mental pain is

capable of being greater in terms of human experience

than that involved in this kind of physical tor

ture . . . 40

Dr. West also testified to the comparative anguish induced

by the loss of citizenship and the death row experience:

“Q. The case cited in 1959 by the United States

Supreme Court, of Trop v. Dulles, and in which the

punishment was the creation of statelessness, depriva

tion of citizenship, to which the court said the punish

ment was illegal because, among others, trying to

subject an individual to an ever increasing amount of

fear and distress, and now can you compare, Doctor,

based upon your understanding, your experience, your

_38 The complete testimony of Dr. West is reproduced as Appen

dix A, pp. 31a-65a. Dr. West was professor and head of the

Department of psychiatry, Neurology and Behavioral Sciences,

University of Oklahoma School of Medicine.

39 See footnote 27, supra; Appendix A, pp. 40a-42a.

40 Testimony of Dr. West, People v. Thorton, Superior Court,

Los Angeles, reproduced in Appendix A, p. 42a.

26

clinical evaluations and your readings, is this kind of

degradation of fear and distress imposed upon a Death

Bow inmate, how is it as compared to that imposed in

this case of this kind that I have described? A. I

would regard it as substantially greater; in other

words, while depriving the person of his citizenship

suggests a terrible loss of support by the parent

society, the Death Bow situation employs not only loss

of support but the ultimate threat by the parent

society, namely that of destruction. There are many

reasons based upon research and human development

that I believe this is the most severe stress that is

possible for a human being to experience.” 41

The former Warden of San Quentin Prison (1940-1951),

Clinton T. Duffy, unequivocally condemned the death

penalty.42 Duffy said,

“In connection with my prison work at San Quentin, I

have observed 150 executions . . . I would say in my

experience the average time an inmate spends on

death row is about three years . . . I have a definite

opinion that the procedures and practices resulting in

the execution of persons in California is cruel. I have

always felt it . . . The inmates are undergoing the

tension of naturally they are going to undergo execu

tion (sic), and they have to be under custody at all

times during this pending execution, the thought that

they are going to be executed and the date is arriving,

getting closer and closer, and the fears and the concern

41 Testimony of Dr. West, People v. Thornton, Superior Court,

Los Angeles, Appendix A, pp. 42a-43a.

42 Testimony of Warden Duffy, People v. Thornton, R.T. 4, 8.

27

and the emotions they are building up are real cruel.

I have known them on death row to become so involved

emotionally that they have committed suicide . . . ” 43

Chaplain Byron E. Eshelman, supervising chaplain at

San Quentin Prison since 1951, describes the execution of

the last man to die on San Quentin’s Death Row:

“We have had other situations of rather violent

resistance and one of the most recent executions which

we had, which was April 12 of this year [1967] and

this was in the execution of Aaron Mitchell, there were

violent aspects to his resistance and while not as vio

lent as in Mr. Riley, but this again to me was a cruel

and highly disturbing episode.

This man developed a bizarre behavior in the last

hours of his life and he took off all his clothes and he

cut his arm with razor blades and when I came down

to the holding cell to administer to him, as I was the

Chaplain of record, and it was my responsibility to

administer to this man at the last, he was standing

naked at the end of his cell and in a crucifix form with

his hands out to the side and his feet together and this

blood was dripping down his arm and I said to him,

‘Aaron, do you know m ef He said, ‘You are not Jesus,’

and I said, ‘No, I am not Jesus,’ and I told him who I

was and at this second he took his right hand and wiped

the blood on his left arm and he said, ‘This is the

blood of Jesus Christ. I am the second coming to save

the world from sin,’ and he kept that position through

out this time and he wTas indicating words, but, of

course, the doctor told me that during the night he

4311 id.

did sit down and he did get a little sleep but the next

morning he was back in the same position.

When it came time to dress him he resisted and he

said that he didn’t want to be bothered. Then he had

to be manhandled and put on the wheelchair and we

had to wipe the blood off his face and arms and tried

to get him to look presentable and then he made a

loud shreik, about the worst I ever heard anyone make,

and then he fell back on the cot and then began to

shreik like in a convulsion but then the officers had

to bring him to his feet. He went almost limp and he

didn’t resist anybody from then on but we had to wait

until the Warden gave the signal to bring him in. I

walked ahead of him and tided to comfort him and con

sole him and say a prayer but he didn’t seem to register,

but when they strapped him in or put him in, he said,

or he cried out, ‘I am Jesus Christ,’ and the execution

proceeded then with this man in this particular state

of mind.” 44

The death penalty is cruel and is more than suspect under

the Eighth Amendment. Once this is accepted, the burden

should be upon the state to show that the death penalty is

necessary to accomplish a permissible end of state punish

ments.

C. T he Heath P enalty I s an'U nnecessary

E xercise of the P enal P owter

This Court has condemned the infliction of unnecessary

pain in the execution of the death penalty.45 The infliction

44 Summary of Testimony, Chaplain Eshelman, in People v.

Thornton, Los Angeles Superior Court No. 328,445, R.T. 90-92.

45State ex rel. Francis v. Resweber, 347 U.S. 483 (1947).

29

of the death penalty has never been heard or ruled upon

under the Eighth Amendment. As early as 1879, the Court

foresaw the feasibility of applying the test of necessity to

punishments of torture and like evils:

“ it is safe to affirm that punishments of torture, such

as those mentioned by the commentators referred to,

and all others in the same line of unnecessary cruelty,

are forbidden by that amendment to the Constitution,

Cooley, Const. Lim. 4th Ed. 408; Wharton, Crim. Law.

7th Ed. 3405,” Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130.

In recent years, several lower courts have employed the

test of necessity under the cruel and unusual punishments

clause.

“Does the punishment go beyond what is necessary to

achieve the aim of the public intent as expressed by

the legislative act? If it exceeds any legitimate penal

aim, it is cruel and unusual,” Workman v. Common

wealth, 429 S.W.2d 374 (Ky. 1968).

Judicially noticeable facts show that imprisonment in a

modern penal institution accomplishes the end of insulation

at least equally well without destroying all hope of rehabili

tation, and that there is no evidence to support a contention

that the death penalty is a special further deterrent to

crime over imprisonment and other penalties.46

The adequacy of life imprisonment as a complete alterna

tive to the death penalty was recognized by Beccaria (Ce-

sare Bonesana) as early as 1764. In his famous essay on

Crime and Punishment, he wrote:

46 See Appendixes A and D.

30

“In order that a punishment be just it should have only

the degree of intensity sufficient to keep men from

committing crimes. No one today, in contemplating it,

would choose total and perpetual loss of his own free

dom, no matter how profitable a crime might be. There

fore, the intensity of the punishment of perpetual servi

tude as a substitute for the death penalty possesses

that which suffices to deter any determined soul.” 47

Beccaria’s position on capital punishment was not

adopted by the political leaders of the Enlightment; and

not without reason, for the existence of reliable penal re

formatories is a relatively late development in history. The

first state prison was opened in Pennsylvania in 1829; the

movement did not become widespread until the end of the

19th century.48 Experimentation and development of ef

ficiency in the maintenance of reformatories took still more

time, so that it is only recently that prisons can be con

sidered reliable in protecting society from the most desper

ate convict.

Modern statistical studies tend to support Beccaria’s

belief that imprisonment is an adequate alternative to the

death penalty.

In terms of the isolation of dangerous individuals, the

Pennsylvania Board of Parole Study found in 1968 that

of those felons who had previously been incarcerated, mur

derers are less likely to have had records of escapes or

other prison infractions; 90% of murderers with prior

47 Cesare Beccaria, “On the Death Penalty”, from a 1764

Treatise, Dei Delitti E Delle Dene, as in : Capital Punishment,

Thorsten Sellin, Ed. p. 41 (N.Y. 1967).

48 See Appendix B for a more extensive history of prisons.

31

incarcerations compared with 79% of non-murderers had

no prior record of escapes or other prison infractions.49

Thus there is no reason to believe that convicted murderers

are more prone to escape, create discipline problems, or

otherwise deviate from the norm of behavior in a maximum

security prison.

Statistical and other sociological studies on the deterrent

factor of the death penalty as compared to life imprison

ment are abundant and virtually uniform in their conclu

sion that there is “no positive relationship between homi

cide rates and the existence or non-existence of the death

penalty, executions or no executions and the homicide

rates” (Testimony of Dr. Thorsten Sellin, People v. Thorn

ton, Los Angeles Superior Court R.T. 14-15).50

“In general, when the homicide rate in states which au

thorize the death penalty is compared with the homicide

rates in other states, it is found that the former states have

homicide rates two to three times as great as the latter,”

Sutherland and Cressey, Principles of Criminology 292 (5th

Ed. 1955). Moreover, there is no study which concludes that

the death penalty is more effective in deterring capital

offenses than imprisonment. See, for example, Schuessler,

“The deterrent influence of the Death Penalty,” 284 Am.

Journ. Pol. and Soc. Sci. 54 (1952); Sellin, Ed., Capital

Punishment 135, 294 (1967); Gibbs, Suicide 517 (1968).51

49 Reprinted in Cal. Legis. Assembly Comm, on the Admin, of

Justice, Report, 3-12 (1970).

50 Reprinted in Cal. Legis. Assembly Comm, on the Admin, of

Justice, Report, 3-12 (1970).

51 An extensive discussion of the social science studies on sub

ject of the death penalty with special emphasis on the question of

deterrence is presented as Appendix D.

32

Other comparisons between abolitionist and retentionist

states show no significant difference in the rehabilitation

success rate of paroled murderers. This is significant be

cause a second conviction for murder carries a certain death

sentence in retentionist states. Any deterrent value pos

sessed by the death penalty would be expected to manifest

itself more in this kind of study than in any other:

“In the eight states, cited here only because of the

availability of parole data (California, Connecticut,

Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Ohio, New York,

and Rhode Island), we find that of some 1,158 mur

derers paroled, six committed another murder and nine

others committed a crime of personal violence short of

murder or a felony. The record of successes shown by

the two abolitionist states (Michigan and Rhode Island)

is certainly equal to that of the six states which retain

the death penalty. Indeed, of the eight states, Califor

nia is the only one with several cases where a murderer

was released and killed again,” Bedau, The Death

Penalty in America 399 (1967). See also California

Legislature Assembly Committee on the Administra

tion of Justice, Report 3-12 (1970).

Other studies show that temporary abolition of the death

penalty with later re-introduction produces no change in

the homicide rates.52 Studies in abolitionist states show no

change in homicide rates before and after the abolition of

the death penalty.53

52 Selim, ed., Capital Punishment 122 (1967).

53 Sutherland and Cressey,. Principles of Criminology 295

(6th Ed. 1960); Gibbs, Suicide 517.

33

It may be concluded on the basis of all studies conducted

by social scientists on the subject of deterrence by threat

of execution that there is no evidence to support the propo

sition that the death penalty deters the commission of capi-.

tal offenses any more than does long imprisonment. Any

conclusion that deterrence is a function of capital punish

ment must be based on anecdotes, intuition, emotion, or the

mere opinion of police and prosecutors. In an age when

such scientific studies are abundant and uncontroverted, it

is unreasonable and irrational to consider the death penalty

to be a deterrent with the alternative of imprisonment

readily available.

In holding that cadena temporal, when imposed for the

crime of falsifying a public record, was excessive and un

constitutional under the cruel and unusual punishments

clause, the Court said:

“The State thereby loses nothing and loses no power.

The purpose of punishment is fulfilled, crime is re

pressed by penalties of just, not tormenting, severity,

its repetition is prevented, and hope is given for the

reformation of the criminal,” Weems v. U.S., 217 U.S.

at 381.

D. T he Death P enalty Shocks the Conscience oe

Contemporary Civilized Men

Many Courts have interpreted the cruel and unusual

punishments clause to mean that those punishments are.

unconstitutional which “shock the conscience of civilized

men,” State v. Evans, 73 Idaho 349, 121 P.2d 326; Stephens

v. State, 73 Okla. Cr. 349, 245 P.2d 788; State v. Ross,

55 Or. 450, 104 P. 596; Mickle v. Henrichs, 262 F. 687

(D. Nev.); Harper v. Wall, 85 F. Supp. 783 (D. N .J.);

34

Politano v. Politano, 146 Mise. 792, 262 N.Y.S. 802; Mc

Donald y . Commonwealth, 173 Mass. 322, 53 ISLE. 874;

State v. Kimbrough, 212 S.C. 348, 46 S.E.2d 273; Fowling

v. State, 151 Fla. 584, 10 So.2d 130; State ex rel. Garvey

v. Whitaker, 48 La. Ann. 527, 19 So. 457; Williams v.

Field, 416 F.2d 483 (9th Cir. 1969); Jordan y . Fitzharris,

257 F. Snpp. 674 (N.D. Cal. 1966).

The former warden of San Quentin Prison, Clinton T.

Duffy, describes his experiences while supervising death

row:

“In connection with my prison work at San Quentin,

I have observed 150 executions. I have supervised the

execution of 88 men and 2 women. I would say my ex

perience is that the average time an inmate spends on

Death Row has been about three years . . .

I hate the death penalty because of its inhumanity.

Doomed men rot in a private hell while their cases are

being appealed, and they continue to rot after a death

date is set. They live in the company of misery, not

only their own but their neighbory. They know there

are two roads out of Death Row, and that they might

well have to take the one which leads to the gas cham

ber.

One night on death row is too long, and the length

of time spent there by the Chessmans and many others

constitutes cruelty that defies the imagination. It has

always been a source of wonder to me that they didn’t

all go stark, raving mad.

The men of Death Row live in fear and hopelessness,

and their thoughts are never off the glass-walled en

closure that waits for them six floors below. This is

35

not justice but torture, and no court in the land will

delibately sentence a defendant to that.

I hate the death penalty because it is a brutal spec

tacle. There is nothing good about an execution and

no one is satisfied when it is over. Even those who say

that justice has been served leave the death house white

and shaking and determined never to return.” 54

Dr. William Francis Graves, former Death Row physi

cian at San Quentin, describes the effect of the experience

on the inmates:

“Coinciding with the arrival of men on Death Row,

there developed a very steady deterioration mentally

and physically. I think that in regard particularly of

Henry Ford McCracken, who I feel probably was

microcephalic to start with. He deteriorated very

rapidly during the months that I observed him on

Death Row, mentally and physically. Finally, he be

came impossible to communicate with and on one occa

sion I found him wallowing in his cell in his own ex-

cretum, just babbling, and I transferred him to the

prison hospital where, under the direction of Dr. David

Schmidt, he was given electric shock therapy and fi

nally after a series of such treatments, he recovered

sufficiently so that his execution could be legally ar

ranged ; so that he had recovered mentally to the point

where he could appreciate the fact that he was being

punished and therefore be legally executed.” 55

Byron Eshelman, San Quentin’s chaplain, describes the

double execution of Pierce and Jordan in 1956:

54 Duffy, Clinton T., 88 Men and Two Women, 254.

56 Testimony of Dr. Graves, People v. Thornton, pp. 147, 154-56.

36

“A few minutes before ten the next morning, Father

Dingberg approached Pierce’s Holding Cell. The con

demned man was covering his face with his hands; the

Father thought he was praying, or trying to catch a

moment of rest.

Suddenly, Pierce lowered his hands and grinned up

at Father Dingberg. Blood was pulsing from his neck.

Dr. M. D. Willicut, San Quentin’s chief medical officer,

and Claude Lansing, a lieutenant of the guards, hur

ried into the cell. Pierce tried to fight them off, slug

ging, scratching, and biting. They pinioned his arms,

discovered a four-inch gash across the right side of

his throat all the way up to the ear.

After a quick conference, Warden Teets ordered the

four guards to drag Pierce from the Holding Cell and

carry him to the gas chamber. Jordan was supposed

to have gone first, as a reward for good behavior, but

Pierce couldn’t be kept waiting now. He fought all the

way down the corridor, screaming:

‘Lord, I ’m innocent! You know I ’m innocent!’

Forty-seven witnesses were gathered outside the gas

chamber windows as Robert Pierce was carried inside.

Blood was spraying from his neck.

‘I ’m innocent!’ he screamed at the witnesses. ‘Don’t

let me go like this, oh, God!’

Two of the witnesses got sick and had to leave.

While he battled against being strapped into the

chair, Pierce alternately cursed, wept and asked for

divine blessing. Then, suddenly, he appeared to relax.

A moment later he was hoarsely screaming curses at

God, the witnesses, the guards.

Jordan was brought in. He looked down at his crime

partner, dying even before the cyanide pellets were

dropped. ‘I t’s o.k.,’ he said, half to himself.

37

Pierce kept up his screaming. He threw back his

head, twisting to show his mutilated throat to the wit

nesses. His white shirt was soaked with blood.

The door was firmly shut, the pellets dropped.” 56

San Quentin’s Roman Catholic chaplain, Father Ding-

berg:

“When I use the term ‘piecemeal dying’ in reference

to the men on Death Row, I mean the following:

I would say that a man on condemned row dies, as I

observe it, daily, weekly, and certainly if he had been

in San Quentin for a protracted period of time, in

terms of a loss of his sense of values, a withdrawing

within himself to the point where relations would be

come more and more difficult, all of which, as I saw,

was the result of this constant element of lack of pri

vacy, being affected by everything that happened to

every other individual on the Row. For example, in

the event a man who was with him on the Row were to

be told that he. was to be executed on a certain day,

that man in effect, by identifying would die with him

even though perhaps his execution might be months,

if not years, away.

Frankly, I believe that when a man finally is taken

downstairs and the cyanide pellets were dropped, he

already had been executed many, many times over.” 57

The following religious organizations support Father

Dingberg and Chaplain Eshelman in their condemnation of

56 Testimony of Chaplain Eshelman, People v. Thornton, pp.

162-63.

57 Testimony of Father Dingberg, People v. Thornton, pp. 643,

651. " - ■

38

capital punishment: Lutheran Church in America (1966);

American Baptist Convention (1960); Church of the Breth

ren (1957); Disciples of Christ (1957); Protestant Epis

copal Church in the United States (1958); American Ethi

cal Union (1960); Union of American Hebrew Congrega

tions (1959); General Conference of the Methodist Church

(1960); American Unitarian Association (1956); Universal

is! Church of America (1957); Anglican Church of Cana

da’s Executive Council (1958); United Church of Canada

(1960); and innumerable state and local church organiza

tions.58

Charles Dickens:

“You have no idea what the hanging of the Mannings

really was. The conduct of the people was indescriba

bly frightful, that I felt for a time afterwards almost

as if I were living in a city of devils. I feel, at this

hour, as if I never could go near the place again. Two

points have occurred to me as being good commentary

to the objections to my idea. The first is that a terrific

uproar was made when the hanging processions were

abolished and the ceremony shrunk from Tyburn to the

prison door. The second is that, at this time, under the

British government in New South Wales, executions

take place within the prison walls, with decidedly im

proved results.” 59

The execution and the experience on Death Bow are so

well hidden from view that only such persons as Warden

58 Filler, “Movements to Abolish the Death Penalty in the

United States,” cited in Sellin, Ed., Capital Punishment, N.Y.

1967.

59 Dickens, “Letter to M. de Cerjat, December, 1849.”

39

Duffy, Dr. Graves, Father Dingberg, and Chaplain Eshel-

man have an opportunity to know what capital punishment

really entails. Indeed, Warden Duffy has written,

“To enforce the law should be a source of pride and

satisfaction. Most men and women charged with these

duties are dedicated individuals. Even though they

often are grossly underpaid, they’re willing to make

personal sacrifices for the good of the community. I ’ve

heard many an official proudly declare after perform

ing a brave and unselfish act, ‘I was glad to do it; it

was only my job.’

I ’ve never heard anyone say, ‘I was glad to take part

in this execution; it was only my job.’

Executions are held behind locked doors in dark,

gloomy enclosures before a handful of witnesses, few

of whom ever brag about what they have seen. No

matter how eager their desire to watch a killer pay the

penalty, their steps falter as they approach the execu

tion chamber, their stomachs turn at what they see

there, and they can’t get away fast enough after the

spectacle is over. Except for a few officials, like the

warden, the doctor, and the clergyman, the names of

people who participate in an execution are never an

nounced. The identity of the executioner is the most

jealously protected of all, for this very title makes the

flesh creep and the blood run cold. I never knew an

executioner who admitted his profession to the outside

world, either while he was active or after he retired.

If the death penalty were right and proper, it would

be carried out in public places and anyone would be

free to watch it. If it were a source of pride instead

of shame, the participants would be heroes and the

40

condemned the villains they were meant to he. Instead

it’s the other way around. A Caryl Chessman becomes

a martyr and his executioner a pariah.” 60

Within this country, there are several dozen death rows.

If and when the deaths—nearly 600 human beings are wait

ing—are inflicted, the knowledge of that event will be in

jected into the common culture, shared by the nation’s peo

ple. Inevitably, the wholesale slaughter will be on the

American conscience, first to shock, then to dull it; and, if

the official slaughter continues, and if history is a guide,

there will be a heightened appetite in some. Cruelty gen