Crawford v. Marion County Election Board Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

December 10, 2007

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Crawford v. Marion County Election Board Brief Amicus Curiae, 2007. e1ee2e9d-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f2a3c8f0-abf7-4b5e-93cc-5ab69510f9ea/crawford-v-marion-county-election-board-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

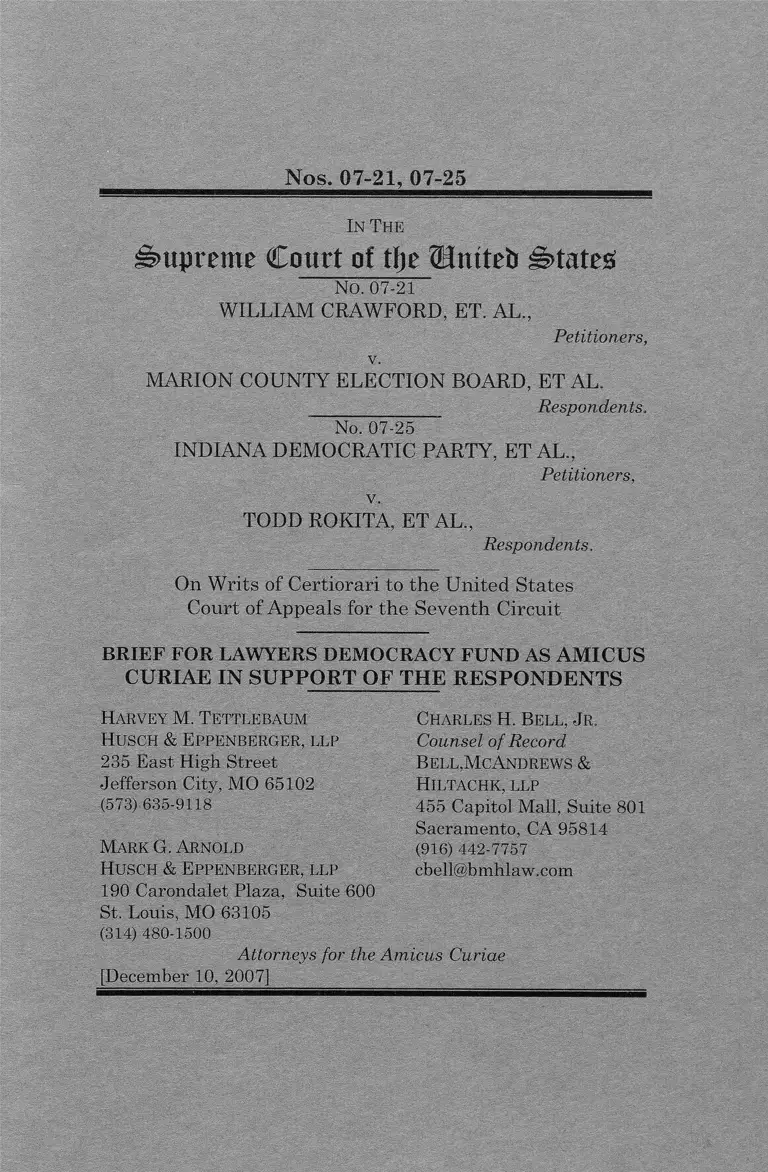

Nos. 07-21, 07-25

In T he

Supreme Court of tlje SJntteb i§>tate3

No. 07-21

WILLIAM CRAWFORD, ET. AL.,

Petitioners,

v.

MARION COUNTY ELECTION BOARD, ET AL.

_____________ _ Respondents,

No. 07-25

INDIANA DEMOCRATIC PARTY, ET AL.,

Petitioners,

v.

TODD ROKITA, ET AL.,

Respondents.

On Writs of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

BRIEF FOR LAWYERS DEMOCRACY FUND AS AMICUS

CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF THE RESPONDENTS

H a r v e y M . T e t tl e b a u m

HUSCH & EPPENBERGER, LLP

235 East High Street

Jefferson City, M O 65102

(573) 635-9118

M a r k G. A r n o ld

HUSCH & EPPENBERGER, LLP

190 Carondalet Plaza, Suite 600

St. Louis, MO 63105

(314) 480-1500

C h a r l e s H. B e l l , J r .

Counsel of Record

B e l l .M cA n d r e w s &

HlLTACHK, LLP

455 Capitol Mall, Suite 801

Sacramento, CA 95814

(916) 442-7757

cbell@bmhlaw.com

Attorneys for the Amicus Curiae

[December 10, 2007]

mailto:cbell@bmhlaw.com

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE .......... .......... . 1

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF

ARGUMENT....................... 1

ARGUMENT...................... 4

I. NONE OF THE PETITIONERS

IN THIS CASE HAVE

STANDING TO PURSUE THE

CLAIMS IN THIS LITIGATION......... 4

A. Article III Standing and

Case or Controversy......................4

B. The Organizational

Plaintiffs Lack Standing to

Assert Any Claims..................... 6

2. The organizational

plaintiffs cannot

assert claims in their

own right..............................6

3. The organizational

plaintiffs cannot

assert claims by

those who forget or

lose their photo

identification...... .............11

C. Individual Plaintiffs Lack

Standing to Assert Any

Claim s........................ .............. 12

II. THE VOTER ID LAW IS A

REASONABLE MEANS TO

SERVE THE STATE’S

COMPELLING INTEREST IN

PRESERVING THE ACTUAL

AND PERCEIVED INTEGRITY

OF ELECTIONS........ .................... 14

A. Courts should defer to the

legislative judgment about

the wisdom of the Voter ID

law................................ 15

B. The Indiana Legislature

could reasonably have

concluded that Photo ID

was a reasonable response

to voter fraud .......... 23

1. The Legislature

could reasonably

have concluded that

both the fact and the

perception of voter

fraud was a serious

ii

problem 24

i l l

2. The Legislature

could reasonably

have concluded that

Voter ID is a

reasonable wav to

combat vote fraud. .......... 28

3. The Legislature

could reasonably

have concluded that

Voter ID would not

seriously impact

eligible voters who

currently lack such

identification....................31

CONCLUSION.............................................................. 32

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Anderson u. Celebrezze, 460 U.S. 780 (1983)..... ...... 17

Burdick v. Takushi, 504

U.S. 428 (1992).... .................. ...............16, 17, 22, 23, 27

City of Los Angeles u. Lyons, 461 U.S. 95 (1983)...... 12

Clingman v. Beaver, 544 U.S. 581 (2005) ........... 20

Cook v. Gralike, 531 U.S. 510 (2001)............... . 15

Common Cause/Georgia v. Billups, 504

F.Supp.2d 1333 (N. D. Ga. 2007) ................ ....... 4, 8, 13

Crawford v. Marion County Election Bd., 472

F.3d 949 (7th Cir. 2007).................. ......... .......... ...... 7, 9

Eu v. San Francisco County Democratic Cent.

Comm., 489 U.S. 214, 231 (1989) .............................. 29

Fed. Election Comm’n v. Nat’l Right to Work

Committee, 459 U.S. 197 (1982) ........................... ...... 18

Friends of the Earth v. Laidlaw, 528 U.S. 167

(2000) ................. ........... ............................ .................... ......... 6

Griffin v. Roupas, 385 F.3d 1128 (7th Cir. 2004), cert,

denied, 544 U.S. 923 (2005)................. ................. ......17

V

Havens Realty Corp, v. Coleman, 455 U.S. 363

(1982).................................................................. 7

Indiana Democratic Party v. Rokita, 458

F.Supp.2d 775, 783 (2006)...... 4

Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555

(1992) ..................................................................... 5, 12

Metro. Wash. Airports Auth. v. Citizens for the

Abatement of Aircraft Noise 501 U.S. 252 (1991)....... 9

New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann, 285 U.S. 262

(1932).............................................................................. 21

Nixon v. Shrink Missouri Government PAC,

528 U.S. 377 (2000).................................................22, 30

Purcell v. Gonzalez,___U .S .___ , 166

L.Ed. 2d 1 (2006).............. ....... ..........................14, 27, 29

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 555 (1964)..............14

Rosario v. Rockefeller, 410 U.S. 752 (1973)...... ..20, 21

San Antonio Sch. Dist. v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1

(1973 ................................................................................ 21

Smiley v. Holm, 285 U.S. 355 (1932)...... 16

Tex. Democratic Party v. Benkiser, 459 F.3d 582

(5th Cir. 2006)................................................................. 11

Timmons v. Twin Cities Area New Party, 520 U.S.

351 (1997)........................................................................ 16

VI

U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton, 514 U.S. 779

(1995).... .................. ............ ............................... ........... 15

Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490, 498 (1975)..............4, 9

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

U.S. Const, art. I, § 4............................... ................2, 15

U.S. Const, art. II, § 1 .......................................... . 16

FEDERAL STATUTES

42 U.S.C. § 1973gg................................ ....... ....... ...... ...18

42 U.S.C. § 15483............... .................................. ......... 18

49 U.S.C. § 30301............... .............................. . 18

STATE STATUTES

Ind. Code § 3-11-1-24....................................................31

Ind. Code § 3-10-1-7.2...................................................31

Ind. Code §3-ll-8-25.1(e)............................................ .31

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Comm’n on Fed. Election Reform, Report, Building

Confidence in U.S. Elections (Sept. 2005) (Baker-

Carter

Report)........ ........................ ................. ........ ..................25

Fund, Stealing Elections: How Voter Fraud Threatens

Our Democracy (2004).......................................... .........25

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE1

Amicus curiae Lawyers Democracy Fund,2 a non

profit, tax exempt organization under section

501(c)(4) of the Internal Revenue Code, has as its

mission to promote fair and honest elections, free of

coercion, intimidation and fraud. Lawyers Democracy

Fund seeks to assure that all citizens are able to

exercise their right to vote and that reasonable,

common sense anti-fraud protections be enacted to

prevention dilution of each person’s honest vote.

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF

ARGUMENT

The Seventh Circuit panel below confirmed the

common sense rationale for Indiana’s Voter ID

requirement. Citing the 2005 Carter-Baker

Commission Report, the panel observed that today,

no person in the United States can board an airline,

enter a government building, or purchase liquor or

cigarettes, without providing photo identification.

Voting is one of the core elements of our American

freedoms, and the right to vote is precious. Yet the

historic record of vote fraud in America is clear.

Attempts to steal the vote, and thus steal a measure

Pursuant to Rule 37, letters of consent from the parties

have been filed with the Clerk of the Court.

No counsel for a party authored this brief.in whole or in

part, and no person or entity other than amicus, its

members or its counsel contributed monetarily to this brief.

of each honest citizen’s franchise, are neither

imagined, nor implausible. Unfortunately, a long list

of such attempts can be compiled since the turn of

this century just seven years ago.

Article I § 4 o f the Constitutional vests the States

with power to enact procedural requirements for

elections, including the power to prevent vote fraud. The

Court views such requirements with deference unless

they impose a “ severe burden” on the right to vote.

The Voter ID law does not impose a severe burden on

the right to vote. On the contrary, by reducing vote

fraud, it preserves the right to vote. An eligible voter

whose ballot is nullified by an illegal vote has been

disenfranchised just as much as an eligible voter who

cannot cast a ballot.

More than 99% o f Indiana voters already have photo

ID and possession o f such documentation is necessary to

exercise numerous other constitutional rights, such as the

right to file suit in federal court or to travel aboard

commercial aircraft. Petitioners have not identified a

single person whom photo ID would prevent from voting

and the district court excluded their statistical evidence

as “utterly incredible.”

Indigent persons or persons with religious objections

to photo ID may cast a provisional ballot, which will be

counted if they file an affidavit to that effect within ten

days after the election. Non-indigent persons can obtain

the documents necessary to obtain photo id by exercising

a minimal amount o f foresight and initiative. This is no

2

more burdensome than the requirement to register to vote

before the election.

If the Voter ID requirement creates a severe burden,

it is hard to imagine any rule requiring voter

identification that would pass muster.

More than half the states have enacted voter ID laws,

and the Court should allow those experiments in

democracy to continue.

There is no question that vote fraud is, in some

places, a serious problem. The bipartisan Baker-Carter

Commission concluded that there is “no doubt” that

voter fraud and multiple voting take place and “could

affect the outcome o f a close election.” The 1600

fraudulent ballots cast in the 2004 Washington

gubernatorial elections substantially exceeded the 129

vote plurality o f the winner, but the result stood because

no one knew who the beneficiary o f the fraud was.

Perhaps the most telling evidence however, is that

Petitioners were unable to identify a single person

injured by the law. This problem also confronted

challengers to Georgia’s and New Mexico’s Voter ID

statutes, as well as Arizona’s citizen ID statute.

These cognizable facts before the Court lead to only

one conclusion. This reasonable, non-discriminatory

voting requirement is akin to advance voter

registration requirements, and subject to limited

constitutional scrutiny.

3

ARGUMENT

4

I. NONE OF THE PETITIONERS IN THIS

CASE HAVE STANDING TO PURSUE

THE CLAIMS IN THIS LITIGATION

A. Article III Standing and Case or

Controversy

The opponents of photo identification laws in

this case find themselves facing the same stunning

omission that every lawsuit challenging photo

identification requirements up to this point has

faced—no individual or group has standing to

challenge the law in question. Opponents again fail

to identify a single voter that is actually harmed by

the provisions of any photo identification for voting

requirement. Indiana Democratic Party v. Rokita,

458 F.Supp.2d 775, 783 (2006); see also Common

Cause/Georgia v. Billups, 504 F.Supp.2d 1333, 1374,

1380 (N. D. Ga. 2007).

Although the Seventh Circuit addressed the

issue of standing very succinctly, Article III standing

is the “ ‘irreducible’ constitutional minimum” that

must be satisfied when a party brings a claim in

federal court. Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490, 498

(1975). In order to assert a claim under federal

jurisdiction, a plaintiff must show that (1) he or she

has suffered an actual or threatened injury (an

“injury in fact”), (2) the injury is fairly traceable to

the challenged conduct of the defendant, and (3) the

injury is likely to be redressed by a favorable ruling.

Id. at 498-99.

5

Petitioners in this case are unable to

demonstrate even the first element of standing,

because there is no entity or individual that has

suffered an injury in fact. In order to show an injury

in fact, a plaintiff must show an “invasion of a legally

protected interest which is (a) concrete and

particularized, and (b) actual or imminent, not

conjectural or hypothetical.” Lujan u. Defenders of

Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555, 560 (1992) (quotation marks

and citations omitted).

Because of the lack of any individuals or

entities that are harmed, if the Court reaches the

merits of this case, there is no evidence in the record,

or elsewhere, that it will actually grant relief to

anyone. Indiana and Georgia first passed laws

requiring photo identification for in-person voting in

2005. Ind. Public Law No. 109-2005; 2005 Ga. Laws,

Act 53. Since that time, the plaintiff organizations

opposing these laws politically and legally have failed

to identify any individual who has actually had his or

her right to vote violated by requiring photo

identification for in-person voting. Common

Cause/Georgia, 504 F.Supp.2d at 1374, 1380; Rokita,

458 F.Supp.2d at 783.

Petitioners can be divided into two distinct

groups: (1) the organizational plaintiffs, including the

Indiana Democratic Party, which are asserting claims

on behalf of their members or in their own right; and

(2) the individuals who are asserting individual and

representative claims, including the state legislators.

Each group lacks standing in this case.

6

B. The Organizational Plaintiffs Lack

Standing to Assert Any Claims

1. The Democratic Party and other

organizations cannot represent claims of

their members in this case

Only under limited circumstances may

organizations represent claims of their members. See

Friends of the Earth v. Laidlaw, 528 U.S. 167, 181

(2000). In order for an organization to pursue an

action on behalf of its members, the organization

must show at least one member who has standing in

their own right. Id. Like the plaintiffs in Georgia,

the organizational plaintiffs in this case, including

the Indiana Democratic Party, fail to locate a single

member of any organization that has standing to sue.

Rokita, 458 F.Supp.2d at 817 (“None of the

Organization Plaintiffs has identified a single

member who does not already possess the required

photo identification and has an injury beyond ‘mere

offense’ at having to present photo identification in

order to vote which, as we have said, does not confer

standing.”); see also Common Cause/Georgia, 504

F.Supp.2d at 1380. As discussed below, the

requirement of photo identification does not result in

a denial of equal protection, and thus the district

court’s determination that the Democratic Party can

assert claims on behalf of its members is incorrect.

Rokita, 458 F.Supp.2d at 813-814. Thus, the

organizational plaintiffs do not have standing to sue

on behalf of their members.

2. The organizational plaintiffs cannot

assert claims in their own right

7

The Seventh Circuit found that the Indiana

Democratic Party had standing to pursue the claims

outlined in the complaint independently, then quickly

moved to the merits of the case. Crawford v. Marion

County Election Bd., 472 F.3d 949, 951-952 (7th Cir.

2007). The Seventh Circuit relied on Havens Realty

Corp. v. Coleman, 455 U.S. 363 (1982), to establish

that the Indiana Democratic Party suffered an injury

in fact, because the Indiana Democratic Party claims

it would devote resources it would not otherwise

spend to get its supporters to the polls if the state

enforced the photo identification requirement.

Crawford, 472 F.3d at 951. However, the assertion

that the Indiana Democratic Party would reallocate

resources is only that— an assertion. The Indiana

Democratic Party has not demonstrated that it

actually reallocated any of its resources, nor are there

any facts, beyond vague assertions, to suggest that it

plans to do so. Rokita, 458 F.Supp.2d at 816.

This Court should not stretch Havens to reach

the same conclusion as the Seventh Circuit. In

Havens, this Court found an organization had

standing because counteracting the discriminatory

housing practices of the defendants resulted in the

organization devoting significant resources away

from its core mission. Havens, 455 U.S. at 379.

Havens is distinguishable because here, as opposed to

the context of the discriminatory housing practices,

an injury in fact cannot be clearly demonstrated.

Resources the Indiana Democratic Party would

expend for elections with or without the photo

identification requirement relate to the exact same

mission: getting Democratic voters to the polls.

8

Unlike the situation in Havens, where the

organization had to devote specific resources away

from its core mission, the method by which the

Indiana Democratic Party performs or encourages its

activities does not detract from its core mission. Id.

In addition, the organization in Havens had

already expended significant resources to counteract

the defendants’ policies, id., while the Indiana

Democratic Party has expended nothing outside of its

legal fees, only saying it will devote some funds to the

subject in the future. Rokita, 458 F.Supp.2d at 816.

The district court in Common Cause/Georgia refused

to extend Havens when the NAACP made an

argument almost identical to that of the Indiana

Democratic Party in this case. Common

Cause/Georgia, 504 F.Supp.2d at 1372. The district

court found that the “injury” of reallocating funds is

completely of the making of the organization, without

evidence that the organization had expended any

funds as a result of the photo identification law. Id.

at 1372-1373. As is the case here, and unlike the

organization in Havens, the NAACP also only said it

would devote funds at some point in the future.

Havens, 455 U.S. at 379; Common Cause/Georgia,

504 F.Supp.2d at 1372-1373.

Extending the holding of Havens, as the

Seventh Circuit did in this case, undermines the

concept of standing by allowing any organization to

create standing by merely claiming that a law would

result in a reallocation of its funds at some point in

the future. Id. at 817. The requirement of an “injury

in fact” is reduced to a mere “allegation of possible

harm,” and potentially allows every organization to

9

assert standing in its own right instead of bringing

claims on behalf of its members. This Court and

other federal courts face the distinct possibility of

rendering a large number of opinions where no actual

case or controversy exists. It is a major change in

U.S. law to conclude that the “ ‘irreducible’

constitutional minimum” of standing by showing an

injury in fact is not required for an organization to

pursue a claim in federal court. Warth, 422 U.S. at

498-99.

But even if this Court did extend Havens, there

is no clear evidence that those less likely to possess

photo identification are members of the Indiana

Democratic Party. The Seventh Circuit relies on

conclusory statements related to the likelihood of

lower-income individuals to lack photo identification

to support the concept that Democrats are less likely

to possess photo identification, but the Seventh

Circuit does not point to a specific study that yields

that same conclusion. See Crawford, 472 F.3d at 951.

The district court in Georgia dismissed a similar

attempt to show a connection between partisan and

income-based likelihood to lack photo identification

under a Daubert motion. Common Cause /Georgia,

504 F.Supp.2d at 1371. The district court in Indiana

discussed at length why the expert report offered by

Petitioners to show discrimination was generally

unhelpful. Rokita, 458 F.Supp.2d at 802-809.

Petitioners’ reliance on Metro. Wash. Airports

Auth. v. Citizens for the Abatement of Aircraft Noise

501 U.S. 252 (1991) is also inappropriate in this case.

While Petitioners argue that this Court found

standing for an organization based on frustration of

10

the group’s primary purpose, this Court focused on

the alleged personal injury to the respondents due to

“increased noise, pollution, and danger of accidents,”

before also citing the increased difficulty for the

group to fulfill its purpose. Id. at 264-265. The

assertion of frustration of purpose without more was

insufficient to establish an injury in fact. Id. If

frustration of purpose alone is a sufficient basis for

finding jurisdiction without any additional injury

requirement, then groups wishing to challenge laws

could create organizations with a “purpose” that

would be affected by a law without ever having to

show any injury in fact. Extending the doctrine of

standing to this point renders it almost meaningless.

If the Court finds that frustration of purpose

alone is sufficient to confer standing, Metro

Washington still does not provide support for

Petitioners’ position. Id. CAAN had a very clear

purpose in Metro Washington: to reduce noise and

aircraft activity at Washington National Airport. Id.

at 265. There is a clear connection between the

challenged authority and a reduction in aircraft

activity. Id. The primary purpose of the Indiana

Democratic Party is not nearly as clear-cut as the

purpose of CAAN, and there is no clear connection

between photo identification requirements and the

purpose of the Indiana Democratic Party. The

Indiana Democratic Party will undertake the same

activities regardless of whether the photo

identification requirement is enforced. Thus, Metro

Washington is inapplicable to this case.

Tex. Democratic Party v. Benkiser is also

distinguishable in that it involved a very clear

11

financial injury that occurred to the state party, not a

vague potential injury. 459 F.3d 582 (5th Cir. 2006).

In Benkiser, the Fifth Circuit upheld the standing of

the Texas Democratic Party because the party had a

clear injury in fact. Id. at 586. If the state allowed

the withdrawal of then-Congressman Tom DeLay, the

Texas Democratic Party would be required to raise a

large amount of funds for a specific time frame to run

a more competitive race. Id. The court could readily

identify the actual injury in Benkiser. Id. In

contrast, the Indiana Democratic Party merely offers

vague assertions of changes to internal accounts

based on the photo identification requirement.

Rokita, 458 F.Supp.2d at 816. The court in Benkiser

also relied on the harm to the election prospects of

the Texas Democratic Party, providing another basis

for an injury in fact that the Indiana Democratic

Party is unable to show in this case, because it cannot

conclusively state the partisan impact of the law.

Benkiser, 459 F.3d at 586-587.

3. The organizational plaintiffs cannot assert

claims by those who forget or lose their

photo identification

The district court incorrectly determined that

the Indiana Democratic Party has the ability to bring

claims on behalf of voters who forget or lose their

photo identification. Rokita, 458 F.Supp.2d at 812.

An individual who forgets photo identification is no

different from an individual who forgets any other

form of identification that may be required by his or

her state, or that was required by the state of Indiana

prior to passage of the photo identification

requirement. Additionally, the Indiana Democratic

12

Party is unable to identify these voters. Id. at 811-

812. It is entirely possible that the voters who forget

their identification are part of different political

parties. Id. The Court has made clear that a mere

hypothetical harm is not enough to grant standing to

a particular plaintiff. City of Los Angeles v. Lyons,

461 U.S. 95, 101-102 (1983). The Court should not

rely on this potential issue to create standing in this

case.

The Indiana Democratic Party and the other

organizational plaintiffs do not have standing to

assert claims on behalf of individual members or in

their own right. They have not suffered a legally-

cognizable harm to themselves, and have no members

which have standing to bring an independent action.

C. Individual Plaintiffs Lack Standing to

Assert Any Claims

The individual plaintiffs do not have standing

to pursue claims that their constitutional rights are

violated by the photo identification requirements. In

order to assert a claim, the individual plaintiffs must

show an actual or imminent invasion of a legally-

protected interest. Lujan, 504 U.S. at 560. The

individual plaintiffs in this litigation simply cannot

show that any legal interest is even affected, let alone

invaded. Some of the individual plaintiffs in this case

already have photo identification, and others have

ready access to photo identification, including one

plaintiff that actually works at the Bureau of Motor

Vehicles (“BMV”). Rokita, 458 F.Supp.2d at 798-799.

Contrary to the finding of the district court,

merely not having photo identification does not confer

13

standing on an individual. The district court in

Common Cause/Georgia recognized that failure to

possess photo identification does not invade a legally-

protected interest, because there are clear

alternatives available to vote without identification.

504 F.Supp.2d at 1373-1374. Individuals who lack

photo identification could easily obtain a free card

from the state, or the individuals could choose to vote

by absentee ballot with no photo identification

requirement. Id. at 1377-1379; Rokita, 458

F.Supp.2d at 812-813, 827. While the Rokita court

found that the imposition of a barrier to voting is

sufficient to show invasion of an interest and grant

standing to individual plaintiffs, it failed to take into

account that no barrier has actually been erected by

the statute because of the available alternatives to in-

person voting. Rokita, 458 F.Supp.2d at 813-814.

Individuals can obtain absentee ballots and freely

vote without photo identification. Id. at 812-813, 827.

Individuals can go to the BMV and obtain free

identification cards that allow them to vote in person

if they so choose. Id. Individuals can vote a

provisional ballot and return with sufficient

identification prior to certification of the election

results. Id. The court in Common Cause/Georgia

correctly recognized that simply requiring photo

identification is not by itself a burden on the right to

vote. 504 F.Supp.2d at 1377-1378.

Because no individuals are harmed by the

photo identification law, there are no individuals with

standing to pursue any claims in this litigation.

Without any individual plaintiffs, the legislators

cannot represent the interests of their constituents or

any other individuals who may be affected by the

14

photo identification law. See Laidlaw, 528 U.S. at

181.

In spite of the best efforts of the Petitioners, no

group or individual before this Court has standing to

pursue the claims in the Petition. No individual or

group has demonstrated the invasion of any legally-

protected interest by the actions of the defendants,

and cannot show standing to pursue any claims.

II. THE VOTER ID LAW IS A REASONABLE

MEANS TO SERVE THE STATE’S

COMPELLING INTEREST IN

PRESERVING THE ACTUAL AND

PERCEIVED INTEGRITY OF ELECTIONS.

There are two ways to disenfranchise a voter. One

is to deny an eligible voter the opportunity to cast a

ballot. The other is to allow an ineligible voter to cast

a ballot that negates the properly-cast vote of an

eligible voter. The latter is just as effective a means

of disenfranchisement as the former:

[T]he right of suffrage can be denied by a

debasement or dilution of the weight of a

citizen’s vote just as effectively as by wholly

prohibiting the free exercise of the franchise.

Purcell v. Gonzalez, ___U.S. ____ , 166 L.Ed. 2d 1, 4

(2006), quoting Reynolds u. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 555

(1964).

The inability of petitioners and their amici to

recognize that simple truth infects every aspect of

their briefing, from the standard of review to the

deference due to the State of Indiana to the

reasonableness of the Voter ID law.

A. Courts should defer to the

legislative judgm ent about the

w isdom o f the V oter ID law

This Court has always recognized the difference

between substantive restrictions on the right to vote

and procedural requirements for the exercise of that

right. The Constitution specifically delegates to the

states the authority to implement the latter. Because

the Voter ID law does not impose a severe burden on

the right to vote, the Court should defer to the

legislative judgment about the wisdom and necessity

of such a law to avoid corruption in the electoral

process.

This Court has held that many voting

requirements were “constitutional because they

regulated election procedures and did not even

arguably impose any substantive qualification. U.S.

Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton, 514 U.S. 779, 835

(1995) (emphasis original). Accord, Cook v. Gralike,

531 U.S. 510, 523 (2001).

Article I § 4 of the Constitution grants “broad

power,” Cook, 531 U.S. at 523,” to the states to

regulate the procedure for elections: “The Times,

Places, and Manner of holding Elections for Senators

15

1 6

and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each

State by the Legislature thereof.”3

The Court has held that this delegation includes,

not just the nuts and bolts of holding elections, but

fraud prevention as well:

[Tjhese comprehensive words embrace

authority to provide a complete code for

congressional elections, not only as to times

and places, but in relation to notices,

registration, supervision of voting, protection

of voters, prevention of fraud and corrupt

practices, counting of votes, duties of

inspectors and canvassers, and making and

publication of election returns . . . .

Smiley v. Holm, 285 U.S. 355, 366 (1932) (emphasis

added).

Voting being a fundamental right, the deference

due the state legislature is not unlimited. The Court

must weigh “the character and magnitude of the

asserted injury” against “the precise interests” the

state is seeking to serve. Burdick v. Takushi, 504

U.S. 428, 434 (1992). A restriction deserves strict

scrutiny only when it places “severe burdens on

plaintiffs’ rights.” Timmons v. Twin Cities Area New

Party, 520 U.S. 351, 358 (1997). When the burden is

not severe, the review is “less exacting” and a “State’s

important regulatory interests will usually be enough

3 Article II § 1 also vests authority in the state legislatures to

determine the method of choosing electors for the

presidency.

17

to justify reasonable, non-discriminatory

restrictions.” Id., quoting Burdick, 504 U.S. at 434

(internal punctuation omitted). Accord, Anderson u.

Celebrezze, 460 U.S. 780, 788 n.9 (1983) (“ [w]e have

upheld generally applicable and evenhanded

restrictions that protect the integrity and reliability

of the electoral process”).

For a variety of reasons, the Court should find

that the burden here imposed is insufficiently severe

to warrant strict scrutiny. Instead, the Court should

defer to the expertise of the legislature.

First and foremost, as the Seventh Circuit

recognized, strict scrutiny “would be especially

inappropriate in a case such as this, in which the

right to vote is on both sides of the ledger.” 472 F.3d

at 852. The objective of voter ID is to prevent an

ineligible voter from disenfranchising an eligible

voter by nullifying the latter’s ballot:

[T]he striking of the balance between

discouraging fraud and other abuses and

encouraging turnout is quint-essentially a

legislative judgment with which we judges

should not interfere unless strongly convinced

that the legislative judgment is grossly awry.

Griffin v. Roupas, 385 F.3d 1128, 1131 (7th Cir. 2004),

cert, denied, 544 U.S. 923 (2005).

In the context of campaign finance laws, the Court

has refused to “second-guess a legislative

determination as to the need for prophylactic

measures where corruption is the evil feared. Fed.

18

Election Comm'n v. Nat’l Right to Work Committee,

459 U.S. 197, 210 (1982). As vote fraud is one type of

electoral corruption, the Court should apply the same

standard here.

The National Voter Registration Act, the so-called

Motor Voter Law, 42 U.S.C. § 1973gg et seq., and the

voter id provisions of the Help America Vote Act

(HAVA), 42 U.S.C. § 15483, both make it

substantially easier to register to vote. The minimal

voter ID provisions in HAVA make it considerably

easier for ineligible voters to register.

Suppose an eligible voter challenged these

statutes on the ground that they increased the

likelihood of vote fraud. One doubts that this Court

would apply strict scrutiny to such a challenge.

Instead, the Court would defer to Congress on just

where on the continuum the line should be drawn.

Second, photo ID is a widely used form of

identification that virtually everyone has and is

relatively easy to get. The district court found as a

fact that more than 99% of all Indiana voters already

had photo ID in the form of a valid driver’s license.

458 F.Supp. 2d at 807. Indiana’s requirements for

obtaining photo ID are not materially different from

those in the federal National Driver Register, 49

U.S.C. § 30301.

Photo ID is essential for the exercise of numerous

rights. To exercise the constitutional right of access

to the federal courts, one must present valid photo ID

even to enter the building. To exercise one’s

constitutional right to travel to the seat of

government to petition Congress, photo ID is a

prerequisite to boarding the aircraft. Most banks will

not disburse cash without a photo ID; many

commercial office buildings deny access to visitors

without photo ID. As the district court held:

The incontrovertible fact that many public and

private entities already require individuals to

present photo identification substantially

bolsters the State’s contention that among all

the possible ways to identify individuals,

government-issued photo identification has

come to embody the best balance of cost,

prevalence, and integrity.

458 F.Supp. 2d at 826 (internal punctuation omitted).

Third, the district court found as a matter of fact

that petitioners could not identify a single eligible

voter who would be unable to cast a ballot due to the

photo ID law, 458 F.Supp. 2d at 822, and that

petitioners’ statistical evidence was “utterly

incredible and unreliable.” Id. at 803:

[I]t is a testament to the law’s minimal burden

and narrow crafting that Plaintiffs have been

unable to uncover anyone who can attest to the

fact that he/she will be prevented from voting

despite the concerted efforts of the political

party and numerous interested groups who

arguably represent the most severely affected

candidates and communities.

19

Id. at 823.

20

Fourth, the law provides an escape hatch for those

who forget their photo ID or cannot obtain one for

religious or economic reasons. The voter may cast a

provisional ballot and validate that ballot by

appearing at the clerk of courts or county election

board within ten days of the election and providing

photo ID. If the voter has religious objections to

photo ID, or is indigent, the voter can execute an

affidavit to that effect and the provisional ballot will

be counted.

This is no more burdensome than a state

requirement that a voter register, in order to vote,

“within a state-defined reasonable period of time

before an election” — a burden that this Court

characterized as “minimal.” Clingman u. Beaver, 544

U.S. 581, 590-91 (2005) (internal punctuation

omitted). It is considerably less onerous than the

rule upheld in Rosario v. Rockefeller, 410 U.S. 752

(1973), requiring such registration eight months

before the presidential primary and 11 months before

the non-presidential primary.

To be sure, it is theoretically possible to imagine

an eligible first-time applicant, not indigent, who

encounters unexpected difficulties in obtaining the

necessary primary documents. But this is a one-time

problem; once in possession of photo ID, the applicant

need not submit any more primary documents.

It is also a problem that can be easily resolved by

a little foresight and a little diligence. If the

applicant starts the process of obtaining primary

documents early enough before the election, those

21

obstacles can be overcome in time to be in possession

of photo ID once the election rolls around.

In Rosario, the voter had to have enough foresight

and initiative to act eight months before the

presidential primary. The Court held that was not an

undue burden in light of the importance of preserving

“the integrity of the electoral process.” 410 U.S. at

761. It is inconceivable that any significant number

of people could not track down primary documents in

eight months.

Fifth, applying strict scrutiny to this modest

reform would almost surely end any further efforts to

stamp out vote fraud. Justice Brandeis was right:

“ [0]ne of the peculiar strengths of our form of

government” is “each State’s freedom to ‘serve as a

laboratory; and try novel social and economic

experiments.”’ San Antonio Sch. Dist. v. Rodriguez,

411 U.S. 1, 50 (1973), quoting New State Ice Co. u.

Liebmann, 285 U.S. 262, 280 (1932) (Brandeis, J.,

dissenting).

Prompted by the Baker-Carter Report, many

states are tinkering with their election laws to root

out vote fraud. Perhaps some of those efforts will

work better than photo ID. Or perhaps there are

better ways to implement photo ID than Indiana s.

Rodriguez held that “ [n]o area of social concern

stands to profit more from a multiplicity of

viewpoints and from a diversity of approaches than

does public education,” 411 U.S. at 50, and the same

is true of efforts to eradicate vote fraud.

22

The flexible and deferential legal standard

announced in Burdick permits the states to function

as laboratories of democracy. It recognizes that the

legislature is far better equipped than courts to draw

the delicate balance between encouraging all eligible

voters to cast ballots and discouraging ineligible

voters from trying to do so.

Petitioners and their amici argue that they are

entitled to strict scrutiny if they can prove that photo

ID prevents so much as one eligible voter from voting.

This Court has never adopted so draconian a rule.

Burdick itself recognizes that every election rule

affects “at least to some degree” an eligible voter’s

right to vote. 504 U.S. at 433:

Accordingly, the mere fact that a State’s

system creates barriers tending to limit the

field of candidates from which voters might

choose does not of itself compel close scrutiny.

Id. (citations and internal punctuation omitted).4

Instead, the Court required a balancing test,

weighing the “magnitude” of the injury against the

state’s interests. 504 U.S. at 434. As the Seventh

Circuit recognized in the instant case, the “fewer

people harmed by a law, the less total harm there is

to balance against whatever benefits the law might

confer.” 472 F.3d at 952. See Nixon v. Shrink

The Court has repeatedly equated ballot access and voting

rights cases as equivalent for purposes of constitutional

analysis. Burdick, 504 U.S. at 438, quotingJBullock v.

Carter, 405 U.S. 134, 143 (1972).

Missouri Government PAC, 528 U.S. 377, 396 (2000)

(“a showing of one affected individual does not point

up a system of suppressed political advocacy that

would be unconstitutional”).

One suspects that petitioners and their amici

would not be thrilled if their logic were applied to

laws like the Motor Voter Law or HAVA that are

designed to encourage voter registration. Such laws

inevitably make vote fraud easier. If the

disenfranchisement of a single voter is enough to

require strict scrutiny, then a single act of vote fraud

requires strict scrutiny and, most probably,

invalidation of these laws. That is no more

reasonable than ousting photo ID if it excludes a

single eligible voter.

Petitioners simply refuse to recognize that vote

fraud disenfranchises eligible voters just as much as

refusing to count their ballots in the first place.

Reasonable people can, of course, disagree on where

the line should be drawn. But that is precisely why

Burdick adopts a deferential standard of review that

the Court should apply in the instant case, just as it

did in Nat 7 Right to Work.

B. The Indiana Legislature could

reasonably have concluded that

Photo ID was a reasonable response

to voter fraud

The district court made a number of factual

findings, none of which are seriously contested.

Those factual findings clearly establish that the

Indiana legislature could reasonably have concluded

23

24

that vote fraud was a serious problem; that photo ID

was a reasonable solution; and that photo ID would

not seriously impact eligible voters.

1. The Legislature could reasonably have

concluded that both the fact and the

perception of voter fraud was a serious

problem.

The district court held that, to the extent that

Indiana was required to provide empirical support for

its concerns about vote fraud, “it has clearly done so.”

458 F.Supp. 2d at 826. The foundation for that

factual finding is the conclusions of the bi-partisan

Baker-Carter Report and the experience of other

states with serious vote fraud.

The Comm’n on Fed. Election Reform, Report,

Building Confidence in U.S. Elections (Sept. 2005)

(Baker-Carter Report) (co-chaired by former

Democratic President Jimmy Carter) concluded that

“there is no doubt” that both vote fraud and multiple

voting occur and “could affect the outcome of a close

election.” App. 138. The Report also concluded that

the “electoral system cannot inspire public confidence

if no safeguards exist to deter or detect fraud or to

confirm the identity of voters.” Baker-Carter Report

at 18.

The most egregious illustration of actual fraud is

the 2004 Washington State gubernatorial election, in

which the winner had a plurality of 129 votes. In

post-election litigation, the trial court concluded that

more than 1,600 ballots had been fraudulently cast.

Since the court could not determine how many of

25

those fraudulent votes had been cast for the winner,

it refused to set aside the election. State S.J. Ex. 3 at

4-5; 19.

Other recent examples of election fraud, accepted

as true by the district court, include:

• In Milwaukee in the 2004 general

election, more that 200 ineligible felons

voted; more than 100 persons voted

twice, used fake names or false

addresses, or voted in the name of dead

people. More than 4,500 votes were cast

than voters listed. State S.J. Ex. 4 at 2-

4.

• In St. Louis, in the 2000 general

election, there were more than 1,000

fraudulent ballots cast, including 14

dead people, 68 multiple votes, and 79

vacant-lot votes. Fund, Stealing

Elections: How Voter Fraud, Threatens

Our Democracy (2004) at 64.

« In the 1997 Miami mayoral election,

dozens and perhaps hundreds of persons

not residing in the city cast fraudulent

ballots. State S.J. Ex. 10 at 1-2.

• The Department of Justice has

conducted more than 180 investigations

into voter fraud since 2002, making 89

charges and securing 52 convictions.

State S.J. Ex. 2 at 23.

26

• Dead people voted in Georgia, Illinois,

and Pennsylvania. State S.J. Ex. 12-14;

18. The Seventh Circuit has held that

voter fraud “is a serious problem in U.S.

elections generally” and Illinois has a

“particularly gamey history” of voter

fraud. Roupas, 385 F.3d at 1130-31.

That is precisely the kind of empirical information

on which this Court has held a legislature may

reasonably rely in making policy. In Nixon, the Court

rejected a First Amendment challenge to Missouri’s

restrictions on campaign contributions based on the

State’s interest in avoiding corruption. The evidence

on which the Court relied included:

• The state treasurer gave the state’s

banking business to a bank that had

contributed $20,000 to the treasurer’s

campaign.

• The state auditor got $40,000 from a

brewery and $20,000 from a bank.

• A political action committee linked with

an investment bank gave $420,000 to

candidates in northern Missouri.

• A state representative was accused of

taking kickbacks for sponsoring

legislation.

• A state attorney general was indicted for

using the state workers compensation

fund to benefit campaign contributors.

Nixon, 528 U.S. at 393-94. The Court described this

evidence as “not presenting] a close call.” Id. at 393.

Accord, Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 27 n.28 (1976)

(relying on the Seventh Circuit’s description of

incidents of corruption caused by campaign

contributions).

Petitioners and their amici make much of the fact

that no one in Indiana has ever been charged with

voter fraud based on impersonating another voter.

The inference they seek to draw from that fact is that

such fraud never occurs. As the Seventh Circuit

observed, it was at least as reasonable for the

legislature to infer that the “extreme difficulty of

apprehending a voter impersonator” explains the

absence of such prosecutions. 472 F.3d at 953.

Under Burdick, the Court should defer to the

legislature on which inference is most plausible.

The legislature was also entitled to consider the

ample evidence of a public perception that voter fraud

was a serious problem. This Court has recognized

that the appearance of corruption in elections is “ [o]f

almost equal concern” as actual corruption. Nixon,

528 U.S. at 389, quoting Buckley, 424 U.S. at 26, and

cases there cited (internal punctuation omitted). The

“avoidance of the appearance of improper influence is

also critical . . . if confidence in the system of

representative government is not to be eroded to a

disastrous extent.” Id. (internal punctuation

omitted). Accord, Purcell,___U.S. a t ____, 166 L.Ed.

2d at 4 (“ [confidence in the integrity of our electoral

processes is essential to the functioning of our

participatory democracy”).

27

28

There is substantial evidence in the record

proving that the public believes, by wide margins,

that vote fraud occurs:

• Before the 2000 elections, a Rasmussen

poll showed that 59% of the electorate

believed that there was “some” or “a lot”

of vote fraud. State S.J. Ex. 22 at 1.

• After those elections, a Gallup poll

showed that 67% of adults had only

“some” or “very little” confidence in the

way votes were cast. State S.J. Ex. 23 at

8-9.

• A 2004 Zogby poll found that 10% of

voters believed their votes were not

accurately counted. Fund, Stealing

Elections at 2.

• More than 13.6% of Americans believed

that the 2004 presidential vote was

unfair. State S.J. Ex. 24 at 1.

Thus, the Indiana legislature had an ample basis

for believing that vote fraud was a serious problem

requiring a reasonable response

2. The Legislature could reasonably have

concluded that Voter ID is a reasonable

wav to combat voter fraud.

There is no question that combating voter fraud is

a compelling state interest, and for precisely the

same reason that access to the ballot box is a

29

fundamental right: voter fraud disenfranchises

eligible voters whose votes are nullified by fraudulent

ones. Voter ID is a reasonable means to accomplish

that compelling interest.

“A State indisputably has a compelling interest in

preserving the integrity of its election process.”

Purcell, ___U.S. a t ____, 166 L.Ed. 2d at 4, quoting

Eu v. San Francisco County Democratic Cent. Comm.,

489 U.S. 214, 231 (1989) (internal punctuation

omitted). Petitioners and their amici admit as much.

We have already alluded to some of the reasons

why voter ID is a reasonable response to the problem

of voter fraud: virtually everyone has government-

issued photo ID; such ID is required for a host of

activities; and a voter without photo ID can cast a

provisional ballot and then validate that ballot with

relative ease.

Perhaps the best evidence that voter ID is a

reasonable response to the problem is that the

bipartisan Baker-Carter Commission recommended

it. The Baker-Carter Report recites that:

• Effective voter ID is one of the “bedrocks

of a modern election system.” Report at

10.

• “[I]n close or disputed elections, and

there are many, a small amount of fraud

could make the margin of difference.”

Report at 18.

30

• “Photo IDs are currently needed to board

a plane, enter federal buildings, and

cash a check. Voting is equally

important.” Id.

Indeed, the Baker-Carter Report is considerably

stricter than the Indiana law here at issue with

respect to provisional ballots. The Report

recommends that voters be allowed to cast such

ballots. After the 2010 elections, however, it

recommends that the voter only have 48 hours to

validate the provisional ballot, compared with ten

days under Indiana law. And it does not have the

escape hatch for indigent voters or those with

religious objections to photo ID. Report at 20-21.

Moreover, there is a wide and growing consensus

in favor of voter ID. In 2001, only 11 states required

it. By September 2005, when the Baker-Carter

Commission issued its report, 24 states required it

and 12 more were considering doing so. Report at 18.

Indiana’s requirements for verifying citizenship are

quite similar to those set forth in the National Driver

Register, 49 U.S.C. § 30301.

Finally, there is strong public support for voter

ID. As the district court found, 458 F.Supp. 2d at

794, a 2004 Zogby poll found that 82% of respondents,

including 75% of Kerry supporters, favored photo ID.

Nixon relied on similar, though less overwhelming

public support, in finding Missouri’s campaign

finance restrictions to be reasonable. 528 U.S. at 394.

It should do the same with voter ID.

31

Thus, the legislature had ample basis for believing

that voter ID is a reasonable way to combat vote

fraud.

3- The Legislature could reasonably have

concluded that Voter ID would not

seriously impact eligible voters who

currently lack such identification.

Likewise, the Legislature had ample reason to

conclude reasonably that Voter ID would not

seriously impact eligible voters who currently lack

such identification. First, there are the exemptions

discussed above, principally the exemption for

absentee ballot voting by mail. Among those

automatic entitled to cast absentee ballots are

Indiana’s disabled and senior voters over age 65. Ind.

Code § 3-11-1-24. In addition, residents of state-

licensed care facilities who vote at polling places

within those facilities are exempted from the Voter

ID requirement. Ind. Code § 3-10-1-7.2; 3-11-8-

25.1(e). Thus, the Legislature provided exemptions

for foreseeable categories persons who were less

likely to be able to travel to obtain Voter ID. Finally,

the Voter ID law allowed any person who failed to

present photo identification at the polls to complete a

provisional ballot, and to provide the photo

identification to an election office within 10 days.

Thus, the Indiana law is replete with exemptions

adopted to mitigate potential impacts of the Voter ID

Law. The fact the law has been administered without

any indication of problems with compliance since its

enactment in 2005, combined with the 2006 data

indicating that 99% of Indiana’s voting age

population had the requisite Voter ID, demonstrates

32

the Voter ID law does not “severely burden” voting

rights, and is constitutional.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, this Court should

affirm the judgment of the Seventh Circuit.

Respectfully submitted.

HARVEY M.

TETTLEBAUM

HUSCH &

EPPENBERGER, LLC

235 East High Street

Jefferson City, MO

65102

(573) 635-9118

MARK G.ARNOLD

HUSCH &

EPPENBERGER, LLC

190 Carondalet Plaza

Suite 600

St. Louis, MO 63105

(314) 480-1500

CHARLES H. BELL, JR.

Counsel of Record

BELL, MCANDREWS &

HILTACHK, LLP

455 Capitol Mall

Suite 801

Sacramento, CA 95814

(916) 442-7757

Attorneys for the Amicus Curiae

CERTIFICATE OF WORD COUNT

As required by Supreme Court Rule 33.1(h), I certify

that the document contains 7,130 words, excluding

the parts of the document that are exempted by

Supreme Court Rule 33.1(d).

I declare under penalty of perjury that the

foregoing is true and correct.

Executed on December__, 2007.

Charles H. Bell, Jr.

,;r- ' - ■ - ; ■■■