Correspondence from Blacksher to Judge Pittman

Public Court Documents

October 24, 1980

3 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Correspondence from Blacksher to Judge Pittman, 1980. 1b0a48be-cdcd-ef11-b8e8-7c1e520b5bae. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f2dc725f-8e78-4248-b30d-c6bb636c8c5d/correspondence-from-blacksher-to-judge-pittman. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

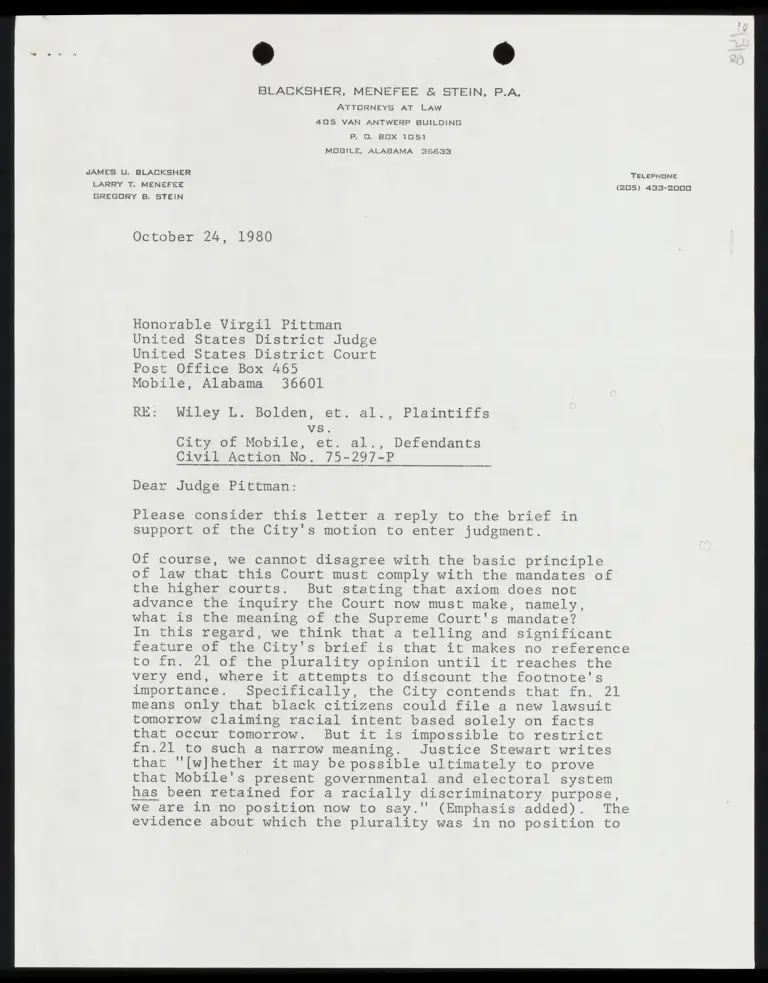

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A.

ATTORNEYS AT LAw

405 VAN ANTWERP BUILDING

P.O. BOX 105)

MOBILE, ALABAMA 36633

JAMES LI. BLACKSHER

TELEPHONE

LARRY T. MENEFEE

(205) 433-2000

GREGORY B. STEIN

October 24, 1980

Honorable Virgil Pittman

United States District Judge

United States District Court

Post Office Box 465

Mobile, Alabama 36601

RE: Wiley L. Bolden, et. al.

vs,

City of Mobile, et. al.,

?

Civil Action No. 75-297-P

Plaintiffs

b J

Defendants

Dear Judge Pittman:

Please consider this letter a reply to the brief in

support of the City's motion to enter judgment.

Of course, we cannot disagree with the basic principle

of law that this Court must comply with the mandates of

the higher courts. But stating that axiom does not

advance the inquiry the Court now must make, namely,

what is the meaning of the Supreme Court's mandate?

In this regard, we think that a telling and significant

feature of the City's brief is that it makes no reference

to fn. ‘21 of the plurality opinion until it reaches the

very end, where it attempts to discount the footnote's

importance. Specifically, the City contends that fn. 21

means only that black citizens could file a new lawsuit

tomorrow claiming racial intent based solely on facts

that occur tomorrow. But it is impossible to restrict

fn.21 to such a narrow meaning. Justice Stewart writes

that "[w]hether it may be possible ultimately to prove

that Mobile's present governmental and electoral system

has been retained for a racially discriminatory purpose,

we are in no position now to say." (Emphasis added). The

evidence about which the plurality was in no position to

Honorable Virgil Pittman

October 24, 1980

Page Two

comment on is referred to in the preceding sentence of

the footnote as the "several proposals that would have

altered the form of Mobile's municipal govermnment'. The

clear meaning of the footnote, therefore, is that this

evidence is still subject to judicial review under the

new legal standards of intent. Otherwise the plurality

would have said that they had examined this evidence and

had found it unconvincing. Certainly, that is the meaning

Justices White and Marshall attached to fn. 21 in their

separate opinions. Surely, if the plurality had disagreed

with Justices Marshall and White in this respect, the

plurality opinion would have noted and disavowed such

crucial misunderstandings contained in the dissenting

opinions. As Section IV.B. of the plurality opinion shows,

Justice Stewart went out of his way to point out what

he considered to be the errors in the dissenting opinions.

Obviously Justice Stewart carefully scrutinized Justice

Marshall's dissenting opinion. If he had disagreed with

Justice uit Li fn. 39, which flatly states that the

plurality intends that on remand the lower court should

reexamine the evidence under the new intent standards,

he would have said so.

We take this opportunity to enclose for the Court's

information the brief just filed by the United States

in Lodge v, Buxton, No. 783-3241 (5th Cir.). This brief

shows that the United States agrees with us that the

Supreme Court in City of Mobile v. Bolden went no further

than to rule that analysis of the evidence under the Zimmer

standards can not sustain a judgment of unconstitutionality.

In particular, we call to the Court's attention the

government's very thorough and careful exposition of an

additional legal theory not yet addressed by the Supreme

Court which is equally applicable to the instant case.

The United States points out that both the fifteenth amend-

ment and §2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 prohibits the

use of facially neutral election schemes that have the

effect of perpetuating racially discriminatory and ex-

clusionery conditions flowing directly from the state's

past official actions designed to exclude blacks from

political power. Basically, this was the theory of law

ammounced in the Fifth Circuit's en banc decision, Kirkse

v. Board of Supervisors of Hinds County, 554 F.2d nT

Honorable Virgil Pittman

October 24, 1980

Page Three

(5th Cir. 1977) (en banc), cert. denied, 434 U.S. 968

(1978). The government's Lodge v. Buxton brief shows how

the Kirksey theory is fully consistent with, and even

reconciles, the Supreme Court's pronouncements in City of

Mobile v. Bolden and White v. Regester. We stand by our

prior arguments that this Court has already made findings

of intent based on legally sufficient evidence already

of record under the Arlington Heights guidelines. However,

we believe this Court should consider the Kirksey theory

as well. In an area of the law that is developing as

quickly as this, judicial economy clearly requires that

lower courts consider and apply to the evidence all legal

and constitutional theories which ultimately must be con-

sidered by the appellate courts.

Best regards.

Very respectfully,

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A.

\ ;

| / N : f / 7 | Fi

| 7 Atl \ AL & 220 EE

/ [|

J. U. Blacksher

JUB :nwp

Enc

cc (w/enc) C. B. Arendall, Jr., Esquire

William C. Tidwell, III, Esquire

(w/o enc) Fred G. Collins, Esquire

Charles S. Rhyne, Esquire

William S. Rhyne, Esquire

Edward Still, Esquire

Jack Greenberg, Esquire

Eric Schnapper, Esquire