Evans v. Newton Petitioners' Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Evans v. Newton Petitioners' Reply Brief, 1965. 9bbc1248-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f2e5a675-92d5-4479-ad4d-95629b36881c/evans-v-newton-petitioners-reply-brief. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

\

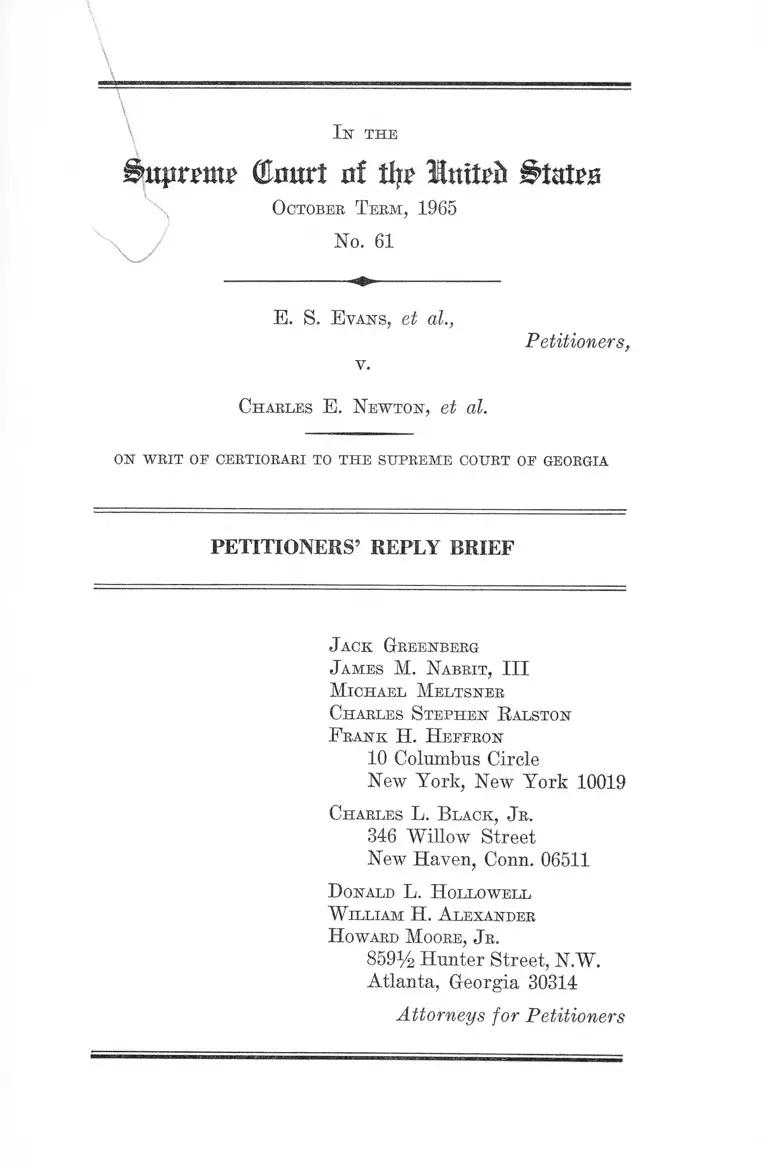

I s THE

g>uprjmtp OJourt of % Init^ B u t zb

"\ October T erm, 1965

No. 61

E. S. Evass, el al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Charles E. Newtos, et al.

OS WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OE GEORGIA

PETITIONERS’ REPLY BRIEF

J ack Greesberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsser

Charles Stephes R alstos

F rask H. Heperos

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Charles L. Black, Jr.

346 Willow Street

New Haven, Conn. 06511

Dohalb L. Hollowell

W illiam H. A lexasder

H oward Moore, Jr.

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

A rgument :

I. General R ep ly ....................................................... 1

II. Certain Particular Errors in Preliminary Parts 5

of Respondents’ B r ie f .......................................... 5

III. The Respondents Are Mistaken in Maintaining

“ The Private Nature of Charitable Trusts”

(Brief p. 23) and in Their Deductions There

from ............................................. -........................... 8

IV. The Appropriate Remedy in This Case (Reply

ing to Respondents’ Point II) .............................. 14

V. Respondents, in Their Points III-V, Mistake

The Application of Shelley v. Kraemer, The

Significance of The Incompatibility of Bacon’s

Two Desires, and The Significance of The City’s

Desegregation .......................... ........ .......... ......... 18

VI. Respondents Are Wrong in Their Contention

That §69-504, Georgia Code, Acts 1905, p. 117,

Is Not A Significant Consideration in This Case 24

Table oe Cases

Brown v. Gunn, 75 Ga. 441 (1885) ............................. 28

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S.

715 (1961) ................................................................... 30,31

PAGE

XI

County of Gordon v. Mayor of Calhoun, 128 Ga. 781

(1907) ................................ -......................................... 28

Dexter v. Harvard College, 176 Mass. 192................. 9

East Atlanta Land Co. v. Mowrer, 138 Ga. 380 (1912) 28

Ford v. Harris, 95 Ga. 97 (1894) .................................. 28

McCletchey v. Atlanta, 149 Ga. 648 ............................ 22

McGhee v. Sipes, 334 U.S. 1 —....................................... 18

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501........ .......................... 12

Mayor and Council of the City of Macon v. Franklin,

12 Ga. 239 (1852) ........................................................ 27,28

Paschal v. Acklin, 27 Tex. 173 (1863) .......... ............... 9

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U.S. 244 ............... 32

Pettit v. Mayor and Council of Macon, 95 Ga. 645

(1894) ........................................................................... 28

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 .............- ............... 3,4,18,19,

20, 21, 23

The Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36 .... 12

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461-------------------—........— 11,12

Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 4

Wheat. 518 ................................................................... 8

PAGE

Western Union Telegraph Co. v. Georgia Railroad

and Banking Co., 227 F. 276 (S.D. Ga. 1915) ____

Ill

E nglish Statute

Elizabethan statute of charitable uses, 43 Eliz. 1, c. 4 9

PAGE

State Statutes

Georgia Acts 1937, No. 50, p. 594.................................. 11

Georgia Code of 1895, Section 4008 (3157) ................. 24, 25

Georgia Code, Section 69-501 (Acts 1892, p. 104)....... 4

Georgia Code, Section 69-504 (Acts 1905, p. 117) ....4, 8, 24,

25, 26, 28, 29,

30, 31, 32

Georgia Code, Section 108-203 ...................................... 9

Otheb A uthorities

Bogert, Trust and Trustees (1960) ........................ 5, 6, 9,10,

11, 21

4 Pomeroy, Equity §1024................................................ 26

In t h e

S u p r e m e (Orm rt ni % I r n t e i i S t a t e s

October T erm, 1965

No. 61

E. S. E vans, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

Charles E. Newton, et al.

ON WRIT o f CERTIORARI to THE SUPREME COURT OE GEORGIA

PETITIONERS’ REPLY BRIEF

I.

General Reply.

Respondents’ brief addresses itself to a number of special

points in petitioners’ argument (and in that of the United

States as amicus curiae). It is petitioners’ belief that these

special arguments can best be replied to within a framework

which exhibits the relevance (or lack thereof) of the issues

to which respondents address themselves. With deference,

it seems to petitioners that the tendency of respondents’

brief is to confuse; the most effective reply is a clearer struc

turing of the issues.

The following are the affirmative parts of the decree of

the Superior Court: (1) The acceptance of the City’s resig

nation as trustee, (2) The appointment of new trustees. It

is against the affirmance of this judicial decree that peti

tioners complain to this Court. Primarily, what petitioners

2

ask of this Court is a reversal, and a remand with directions

to vacate that decree and undo its effect.

The Superior Court entered this decree in a suit brought

by persons appointed by a public authority, with the an

nounced sole purpose of bringing about the reinstitution of

racial discrimination in Baconsfield. The resignation ac

cepted was tendered by a public authority on the assigned

sole ground that its tendering and acceptance would make

possible such reinstitution of racial discrimination. The new

trustees, under these circumstances, were appointed in order

that they might discriminate. It is petitioners’ contention

that the Superior Court’s action in accepting the resigna

tion, and in appointing new trustees, given the nature of

the parties and the state of the pleadings before it, con

stituted the last and crucial step in a set of actions viola

tive of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Petitioners contend that the Superior Court’s action was

violative of the Fourteenth Amendment, and must be re

versed and undone, on either of two hypotheses, which

exhaust possibility:

(1) The Superior Court’s action was violative of the

Fourteenth Amendment, if it be assumed that the new

trustees, if confirmed in office, might constitutionally

discriminate. On that view (which petitioners think

the wrong view) the actions of the Board of Managers

and of the City, and the action of the Superior Court

confirming the steps they had taken, are unconstitu

tional on the ground that it is not the proper business

of any public authority to act affirmatively to clear

the way for racial discrimination, even though that

discrimination will have become lawful in itself in con

3

sequence of the accommodating governmental action.

Here, of course, one parallel will be Shelley v. Kraemer,

discussed at length by respondents, but this is so much

stronger a case than Shelley that none of the perplex

ities surrounding that case in many minds should im

pede decision in this case. Here the intervention of

publie authority—Board of Managers, City, and a

Court of Equity supervising a charitable trust—is

several orders of magnitude higher than in Shelley.

And here, in contradistinction to the lower court’s

action in Shelley, the public power is not carrying

out an unequivocally expressed private choice, but is

itself inescapably choosing between two equally clear

instructions of the testator, incompatible as a matter

of law.

(2) The Superior Court’s action was violative of the

Fourteenth Amendment if the resegregation of Bacons-

field by the new trustees would itself violate the Four

teenth Amendment, because on that hypothesis the ac

tion of the Board of Managers, the City and the Court

was directed at the institution of a discrimination for

bidden by the Constitution. It would not matter that

a new lawsuit might after a lapse of time correct the

discrimination. The Constitution forbids racial dis

crimination for a day or a year as well as for a century.

If it will be unconstitutional for the new trustees to

segregate, then it was unconstitutional for the Superior

Court to put them in office for that unlawful purpose,

after a resignation, tendered by a City, for the same

announced unlawful purpose.

It is to be the establishment of the second of these alterna

tive grounds that the establishment of the illegality of

4

discriminatory operation of Baconsfield, by the new trus

tees, is essential. (The unlawfulness of such operation with

the city as trustee is conceded by itself.) Petitioners, reply

ing to respondents’ arguments, will contend that such oper

ation would be unlawful:

(1) Because the state power, favoring charitable trusts

and policing compliance with their terms, would be

involved in a manner forbidden by the doctrine of

Shelley v. Kraemer.

(2) Because, against the background of Georgia law

prior thereto, §69-504 of the Georgia Code must be

taken to have constituted a form of state influence

surrounding the creation of trusts; indeed, that section,

against such background, seems to have made flatly

unlawful the unsegregated limitation—“all women and

children”—exactly corresponding to the segregated one

Senator Bacon used—“white women and children.”

(3) Because the public character of Baconsfield—not

necessarily as a charitable trust in general, but as a

charitable trust that can be held to be such only because

of its wholly public purpose and, indeed, its taking

over of a governmental function—invests it with gov

ernmental character.

(4) Because, beginning with its necessary affirmative

approval of the conditions in Senator Bacon’s will

(Georgia Code 69-501, Acts, Ga. 1892, p. 104), the past

involvements of the City with Baconsfield are such

as to make it impossible for a formal transfer to eradi

cate the factor of state involvement in its operation.

Petitioners, then, contend that the decree entered below

violated the Fourteenth Amendment on either of the two

5

possible views. It was either (1) the last and confirming

step in a series of actions, themselves taken by public au

thority, by which a racial discrimination previously unlaw

ful was purposefully made lawful, or (2) the last and

confirming step (as petitioners urge is the correct view)

in a series of such actions, by which an unlawful racial

discrimination was made factually possible, at least for

a time. On either view, reversal is required, and the apt

remedy is a mandate requiring rejection of the City’s resig

nation and rescission of the appointment of new trustees.

While petitioners will reply one by one to such of respon

dents’ points as require it, each such reply should be read

with the above outline in mind.

II.

Certain Particular Errors in Preliminary Parts of

Respondents’ Brief.

A. “ The Board of Managers of Bacons field.'”

Under the quoted heading, at p. 12 if., respondents con

tend that the Board of Managers of Baconsfield is not an

organ of public power in any sense. “ The Board is not the

agent of the City but of Mr. Bacon.” p. 12. This conten

tion is made in the face of the fact that the Board is ap

pointed by the City Council, to supervise a park of which

the City is trustee. That Georgia law and equity give

such trustee no power over such a Board is hard to believe.

See, Bogert, Trusts and Trustees, $391, at pp. 205-6 (1960).

But in any event the Board was, at the crucial time of

the inception of this lawsuit, and until appeal was taken

from the lower court’s decree, constituted, as to personnel,

by the City Council. It was, moreover, all white (a thing

6

which can hardly be held immaterial to its deciding to

start this suit) because the City Council, a purely public

authority, obeyed a private man’s wish by making all

white appointments, thus discriminating racially.

The petition in the court below seems in itself to rec

ognize the City’s ascendancy over the Board, at least in

part, for it confesses the Board’s inability to control the

park’s use, while at the same time saying that a new trustee,

in the City’s place, would have powers the Board does not

have. If the Board is independent of the City, why could

it not have done what the new trustee could do?

But if the respondents were to succeed in establishing

their thesis that the Board was in complete charge, inde

pendently of the City, they would have won a Pyrrhic

victory. They rightly see that this thesis requires that

the City be viewed as a “ passive title holder,” a charac

terization said by respondents to be of “ vital significance.”

(Respondent's Brief, p. 12) But if that really were all

the City was, then its “ resignation” was a sham, a “ res

ignation” from nothing, a “ resignation” which could have

had no reason, and can bear no significance, except clearing

the road for the continuing all-white character of Bacons-

field. If respondents are right, the City had no duties to

resign from, and resigned away only the claims of its

colored citizens. None of the substantial reasons for allow

ing trustees’ resignations would apply (see Bogert, Trusts

and Trustees, §515 (I960)), and to “ freeze” the City as

trustee (see Respondents’ Brief, p. 43) would “ freeze” it

in nothing, but would, on a practical analysis, be no more

than requiring it not to act affirmatively as an accessory

before the fact to racial discrimination, while at the same

time very substantially breaking its trust, as a City, to

all its citizens.

7

Finally, the involvements of the City, in tendering its

“ resignation” and in other manners, are so deep, that the

public power is vitally engaged, whatever view be taken

of the status of the Board of Managers.

B. “ The Scope of the Georgia Supreme

Court’s Decisions

In the section so headed, respondents appear to be con

tending that no issue of federal law was raised before or

decided by the Georgia Supreme Court. This thesis is one

petitioners confess difficulty in understanding. Petitioners’

amended petition for intervention, in the Superior Court,

objected on federal constitutional grounds to the exact ac

tion the court later took (R. 63). The repugnancy of this

action to the Fourteenth Amendment was assigned as error

to the Georgia Supreme Court (R. 2). As stated and in

substance, this was a federal question, the question whether

the resignation could be approved, and new trustees sub

stituted, all for the overtly proclaimed purpose of re-segre

gating Baconsfield, without violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment. No legerdemain, no prestidigitation with

state code provisions, can make that question anything

but federal.

It is true that, when the order was entered in the Su

perior Court, segregation had not yet recommenced. But

it had been announced repeatedly, on the sheer common-

law record, that the purpose of the whole proceeding was

resegregation, that that and only that was what the order

was in aid of, and that the business would be getting under

way as soon as practicable after the order was signed.

Whether the judicial act performed in that context and

with that effect was in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment is the central federal question in this case. That it

lias clear logical connections with the further federal ques

tion—whether the racialist operation of the park by “ pri

vate” trustees also violates the Fourteenth Amendment,

does not make it any the less a question in itself, or any

the less “ federal” .

III.

The Respondents Are Mistaken in Maintaining “ the

Private Nature of Charitable Trusts” (Brief p. 2 3 ) and

in Their Deductions Therefrom.

Perhaps seeking to meet petitioners’ arguments (Peti

tioners’ Brief, pp. 22 ff.) that the public character of Ba-

consfield tends to bring this case within the rule of Marsh

v. Alabama and other cases, so as to render unlawful its

contemplated all-white operation (see Summary above,

p. 4), the respondents draw large consequences from

Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 4 Wheat. 518,

a case almost entirely unrelated to this one, on its holding.

The draft they make on that famous opinion is not honored

by its language, as they quote it :

“ But if this be a private eleemosynary institution,

endowed with a capacity to take property for objects

unconnected with government, whose funds are be

stowed by individuals on the faith of the charter; if

the donors have stipulated for the future disposition

and management of those funds in the manner pre

scribed by themselves, there may be more difficulty in

the case,. . . ” (4 Wheat. 630).

But Baconsfield is not private. It is “ dedicated to the

public use,” in the language of the statute authorizing its

creation, G-a. Code §69-504. The funds for keeping it up are

9

authorized to be “ covered” into the City Treasury (R. 24).

Its objects, far from being “unconnected with government,”

are governmental objects, more often attained by govern

mental action than by any other means.

We have to do here not with a college—planning curricu

lum along special lines, hiring faculty by acts of judgment,

selecting students for special aptitude, choosing books,

closed by its very nature to the general public—but with a

park, altogether public except for Negroes. The question

whether the “private” character of a charitable trust for a

college would, if granted, irresistibly (though paradox

ically) imply a similarly “private” character in a charitable

trust for a public park, is a question that can be sensibly

answered only by recourse to the respective (and very dif

ferent) reasons of the law for supporting these two so

dissimilar “ charities” . Such a comparison is instructive, for

it serves to highlight and make both manageable and lim-

itable the definite public character of such trusts as the

Bacon trust.

“ Schools of learning, free schools, and scholars” are in

the Elizabethan statute, 43 Eliz. c. 4; cf. Ga. Code §108-203.

Such gifts can be and commonly are limited to restricted

classes, and to restricted aspects of education. Paschal v.

Acklin, 27 Tex. 173 (1863); Dexter v. Harvard College,

176 Mass. 192. A park for the use of one person a year,

or of all who could pass a special examination, never was

thought to be a charitable object.

The reason, in the case of educational trusts, is succinctly

stated in Bogert, Trusts, §375:

Society will be aided if any or all of its citizens, rich

or poor, obtain wisdom, knowledge, skill or culture.

10

The theory upon which charitable trusts for parks have

been sustained, as summed up by the same authority, is

different toto coelo. The title of the paragraph is included,

because it speaks directly to the theoretical question:

§378. Governmental Trusts— Community Benefits

Governments (whether national, state or local) have

as their objects the furnishing of facilities and services

which will make the lives of their citizens comfortable

and safe. They carry benefits of a social nature to

large groups. Their work is not confined to distribu

tions for the mere financial enrichment of their in

habitants. Trusts for governmental or municipal pur

poses are therefore charitable. In the Statute of Char

itable Uses these trusts were represented by gifts for

the repair of bridges, ports, havens, causeways, sea

banks, and highways.

̂ ^

Types of Governmental Benefits

Examples of charitable trusts of this class are to

be found where the purpose of the trust was to furnish

to the inhabitants water, light, or gas, at cost or less,

or supply other public utility services which are usually

or occasionally furnished by municipalities; to con

struct or repair streets, sidewalks, roads, or bridges;

to erect or keep in order sea dykes, landing places,

levees, docks, and similar works on the ocean or other

water fronts; to supplement the existing police or fire

departments of a municipality; to establish or aid life

saving stations; to originate or maintain public parhs

or playgrounds, and monuments, fountains, gates, or

other ornamental or useful structures therein; to pre

11

serve natural scenery, or to beautify public property

or private grounds by encouraging the keeping of fine

yards and gardens or by planting trees, shrubs, or

flowers; or to improve the living conditions of the

people, or to promote understanding and good feeling

between different groups in society, or to aid the cause

of peace. Bogert, Trusts and Trustees, §378, pp. 170,

177-180 (1960). (Emphasis supplied and footnotes

omitted.)

This passage has been quoted at length because it is only

in a full context that we can perceive how thoroughly the

very concept of the charitable trust for a park is saturated

with public character. It is held to be charitable precisely

because it is public in all its bearings—because its main

tenance is a governmental function, and because it is di

rectly accessible to all. (A secondary authority, summing

up the law, has been used, because there are no Georgia

cases, and it is the general state of the subject that is

relevant to the present purpose.) The public character of

such a trust as the present, and perhaps even the essen

tiality of that character to its validity, is recognized very

clearly in Georgia Acts 1937, No. 50, p. 594, declaring that

“ all gifts to the United States, or to any state or to any

sub-division thereof for any public purpose, shall be char

itable.”

We have dealt with this abstract issue, “public vel non,”

because respondents have posed it, but the significance of

the term “ public” can be assessed only in the context of

some purpose, e.g.: Do we mean “public” so as to sxxggest

a parallel with Terry v. Adams? Or so “ public” that the

failure of the state affirmatively to prevent racial discrim

ination is a “ denial” of equal “ protection” in the community

12

life—a denial which may result from state “ inaction” as

well as from state “ action”—if, against plausibility, the

state be thought not to “ act” in its favoring of charitable

trusts? For these purposes, the different kinds of charitable

trusts may well be not reducible to a single category. This

case cannot pose all the issues that will arise in later cases,

and we are in no position either to plead future and perhaps

hard cases, or to make concessions for those who will be

involved in them. But we do submit that where a trust,

such as this one, is of a sort held “ charitable,” with all

of state favor such a holding implies, only on the grounds

that it extends a benefit immediately to the public at large,

and that it performs a function of government, then that

trust ought to have to respond to constitutional guarantees.

We submit that such a case falls squarely within the prin

ciple of Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501; if the streets of

the town had been dedicated on charitable trust, with the

formal title in a trustee selected by the Company, and the

dirty work in the hands of a Board of Managers, could

Marsh’s conviction have stood? We submit that such a

case as the present should be held within the reason of

Terry v. Adams, for a governmental function is as defi

nitely being performed in this case as in that.

Respondents (their Brief, p. 26) imagine horrible results

if Baconsfield be opened to all the citizens of Macon. These

all disappear when one grants to this Court the capacity

to make proper distinctions for reasons of weight. Re

ligious “ discriminations” in institutions never opened to

the general public may not be “ arbitrary” at all, but may on

the contrary be implementary to religious liberty; racial

discrimination invokes no analogous countervailing consti

tutional or societal value. The first opinion construing the

Fourteenth Amendment, The Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U. S.

13

(16 Wall.) 36, recognized and emphasized the obvious

historic fact that the Amendment was aimed primarily at

eliminating racial discrimination; to say that racial dis

crimination is always forbidden is not to say that every

differentiation is always forbidden. At the same time,

some of the respondents’ horribles need thinking about,

when brought closer to this case. Suppose a large public

park in Macon were, by the will of a man long dead, open

to and frequented by the whole public, except that Eoman

Catholics were excluded? This example, authentically hor

rible, seems the logical consequence of the position respon

dents urge. If every “ charitable” trust for a governmental

purpose, like this one, is immune from federal constitutional

standards, then a few rich men and a compliant city ad

ministration could racialize a town, suppress free speech in

many of its functionally public places, and impose serious

disadvantages on minority religions, without responding to

the Fourteenth Amendment. It happens that only Negroes

now have to fear a widespread use of the doctrines the

respondents urge. But they should not be made, because of

their unique political vulnerability in the present time, vic

tims of a theory that has no stopping place short of such a

consequence.

14

IV.

The Appropriate Remedy in This Case (Replying to

Respondents’ Point II).

In this point, respondents seek to send the federal claim

of petitioners wandering in an untraceable labyrinth of

state law. As always, this attempt has to fail; the clue, as

always, is the Supremacy Clause.

There is more than one way to violate the Fourteenth

Amendment. Petitioners claim, to be sure, that segregation

of this park by “ private” trustees, against the background

shown on this record, would in future violate the Four

teenth Amendment. But petitioners also claim that the

organs of the State of Georgia may not, in a lawsuit brought

for the announced purpose of segregating a facility which

by no other means can be segregated, act in concert for

the proclaimed end of attaining this segregation. One body

appointed by a public authority brought a suit praying

that the court so alter the legal position as, on their theory

of the matter, to clear the way for segregation. A second

body—the City of Macon—obligingly cleared the way, an

nouncing in a resolution of the Council that said that was

its purpose. The Superior Court then acted judicially by

accepting a resignation tendered on this ground and this

ground only, being apprised by the record before it that

that was the ground and that the whole proceeding before

it had no other aim or expectable effect. Starting with a

situation in which, by repeated confession, exclusion of

Negroes from Baconsfield was unlawful, these parties,

wielding state power, so acted as, at least hopefully, to make

it lawful, and (if that hope were doomed to be vain) so as

to make it factually possible until another lawsuit was

15

brought. Whatever else violates the Fourteenth Amend

ment, that kind of action by state-empowered governmental

entities violates that Amendment. State-law categories and

state-conferred powers can have no bearing on the matter.

Nor is the remedy in this court unclear or difficult. The

decree of the Superior Court, accepting the City’s resigna

tion and appointing new trustees, was an essential step in

a set of actions violating the Fourteenth Amendment. If

this case goes back to the state court under a mandate that

that decree be reversed, then what has been done up to now

will be undone.

It is quite true that, if “ private” trustees are confirmed

in their trusteeship, and exclude Negroes from this park,

these petitioners or others similarly situated may apply

for relief, contending that such segregation violates the

Fourteenth Amendment. It is also true that, on one alter

native, the merits of the present suit implicate the question

that would then be raised, for if exclusion of Negroes by

the new trustees would be unlawful, then the decree of the

Superior Court constituted a substitution of a trustee who

proposed to segregate, for one who was not segregating.

This judicial action, on the hypothesis that segregation of

Baconsfield by any trustee would violate the Fourteenth

Amendment, would amount to the appointment by a Georgia

court of a trustee who proposed to infringe the Constitu

tion, for the purpose of his infringing it. And the remedy

in this court at this step would be just the same—the un

doing, by apt mandate, of this judicial action hostile to the

federal right.

It is because of its relevance in the second of these alter

native theories that petitioners—joined by the United

States as amicus curiae—have presented argument that

16

segregation of Baconsfield, in the whole setting, would vio

late the Fourteenth Amendment, whoever the trustee might

be. In the procedural setting of this case, that argument,

though very important, is immediately material only as it

establishes the impropriety of the lower court's action in

bringing about a state of things in which a trustee appointed

for the purpose of segregating takes office. But, petitioners

also contend that the alteration of affairs so that a previ

ously unlawful segregation could become lawful would be,

equally, a forbidden objective for the city councils and the

courts of Georgia. Getting in a trustee who will segregate

is not a proper public objective, whatever the subsequent

status of his acts will be.

Bespondents argue at length against the availability of

the doctrine of cy pres in this case, though neither peti

tioners nor the United States as amicus have laid any stress

on this point in their briefs here. Petitioners cheerfully

concede that Georgia controls her own legal terminology,

and that if the state law as defined by the state courts can

not call by the name cy pres any doctrine which will re

quire the reversal of this case then another name has to be

found. The federal doctrine we invoke will not fail merely

because it may not fit into the categories of Georgia law.

The federal requirement is that the agencies of a state

refrain from so acting as to foster and facilitate segrega

tion. They have so acted in this c9.se, and the exactly

tailored corrective measure is a mandate requiring that the

unconstitutional steps—the acceptance of the resignation

and the appointment of new trustees—be recalled.

In the background is the question whether the conse

quence of opening of this park will be the failure of the

trust and reverter to the heirs. That issue has nowhere

17

yet been briefed or argued; it seems unlikely that this

court would let stand an unconstitutional administrative

and judicial action, on the ground that to disturb it might,

when all the facts are known and all the arguments heard,

result in reverter. At this stage, it seems almost enough

to say that the express language of Senator Bacon’s will

seems to make the feared result impossible (R. 19). At

the least, no judicial decree of reversion could pretend to

implement Senator Bacon’s intention, for, here again his

intentions were both clear and legally incompatible— (1) to

keep Negroes out of Baconsfield and (2) to keep Bacons-

field a park forever. Choice between these would not give

effect to his will, but would be a judicial choice between two

incompatible terms of his will, a choice which the court, a

state agent, and not Senator Bacon would be making. It

might be added that the affirmative purpose of this trust,

a park for white people, will not fail if the park is opened

to all, for the white people will have as much access to it

as they ever had; to hold that the admission, as well, of

colored people vitally frustrates the trust would seemingly

have to rest on the proposition that, as a matter of law,

proximity to Negroes is so great a detriment to whites as

to ruin the park for the latter. I f the time ever came, peti

tioners would say what little needs to be said about the

standing of that proposition as a state-law ground for

decision, in confrontation with the Fourteenth Amendment.

18

V.

Respondents, in Their Points III-V, Mistake the Ap

plication of Shelley v. Kraemer, the Significance of the

Incompatibility of Bacon’s Two Desires, and the Signifi

cance of the City’s Desegregation.

“ In Shelley v. Kraemer,” say respondents, “ there was in

volved the right of a Negro citizen to buy property which

the owner desired to sell him . . . ” This is a flatly mistaken

account of Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1. Shelley actually

concerned a plaintiff’s invocation of the judicial process to

prevent a Negro from being in a certain place, on the ground

that state contract and real property law gave the plaintiff

the right to keep the Negro from being there. The case in

volved principally the right of a Negro to occupy a house

in violation of a covenant against Negro occupancy, bind

ing on him as a matter of state law, as against the claim

of his neighbor to oust him. In McGhee v. Sipes, 334 U. S. 1,

companion case to Shelley, and decided on the same day

and on the same grounds, the seller was not even a party;

in both cases, it was occupancy, not sale that was at stake.

The negative easement held by the plaintiff in Shelley was a

property right under state law, as well as a contract right,

and consisted in the right to have no Negroes occupying

the property on which the easement lay; so the state court

in McGhee described it.

On every ground on which the Shelley rule might be de

fined and limited, the present case is a stronger case than

Shelley. I f the Shelley rule is to be limited to a context

of public impact of discrimination, the park is more in

the public life than is the home or even the neighborhood.

I f the functional equivalence of racial covenants to racial

19

zoning contributed to the Shelley result, then it can be

noted that the result of the Georgia Court’s action will be,

at least hopefully, the functional equivalent of the same

old segregated Baconsfield as run by the City. If public

involvements collateral to that of the court (e.g., the record

ing system in Shelley) are needful, those are so extensive

and so obvious here as to make enumeration at once onerous

and needless. If what avails is the lack of competing con

stitutional values, none are found here.

The one rationally arguable affirmative objection to this

Court’s action in Shelley was that the discrimination com

plained of there, though enforced by judicial action,

originated in an unequivocal choice by private parties. On

that score, this case is far stronger than Shelley. In that

case, the “ private choice” was univalent. Here no facade of

“ construction” can disguise the fact that Senator Bacon

plainly wanted, and said he wanted, two legally incom

patible things, (1) an all-white park, and (2) a park held

by the City. We may guess that he would have then pre

ferred, or now, if living and looking over the modern world,

would prefer, one or the other. But the will, besides provid

ing for exclusion of Negroes, very carefully back-stops the

provisions for City control. If the City cannot under its

Charter serve as trustee, then the City Council is to ap

point the new trustee (a provision ignored in the proceed

ings below), and that trustee is to act subject to “ such safe

guards and restrictions” as the City Council imposes. The

City is authorized to commingle the trust funds in its own

treasury (B. 24). The individual trustees for the life of

Mrs. Bacon and the daughters had to report annually to the

City. The City is to approve new members of the Board of

Managers (another provision ignored in the proceedings

below).

20

With all this in the will, it is not open to any court to say

that Bacon’s desire for public involvement in the manage

ment of the park is not clear. In Shelley then, the state court

had at least enforced the unambiguous will of contracting

parties. In this case, the state court had ineluctably to

choose between equally clear expressions. Such a choice is

inescapably an affirmative judicial act, a choice between

policies. Confronted with such a choice, no state organ,

court or city or board of managers, or all in concert, can be

permitted to choose the policy of segregation in the name of

carrying out the will of a private donor.

The respondents, to be sure, invite us to speculate on the

relative importance to Bacon of these incompatible provi

sions. Such speculation, to be applicable at all to the cur

rent situation, would have to address itself to the question

whether Bacon, whose death was closer to Appomattox than

to 1965, would prefer to give up his desire for public control

of the park rather than give up his desire to segregate.

Would he see a common resort to a public park in a city the

size of Macon today as constituting “ social relations,” the

thing he desired to avoid? (R. 21) In 1964, a former Sena

tor from a Confederate state led the way to the passage

of the Civil Rights Act, and one Congressman from Bacon’s

own state voted for it and was re-elected. Might Bacon have

come to see the present situation somewhat as they see it?

These, the only relevant speculations, would be altogether

idle. The only thing we know is that Bacon provided, very

deliberately, for discrimination and for public control, and

that the organs of the State of Georgia, choosing discrimina

tion at the expense of public control, are not “ following” a

private man’s plan for his property, but choosing, on their

own responsibility, between two incompatible features of

his plan.

21

Nor does the relatively passive act of the state court—

“ accepting” the City’s resignation—make that judicial act

any the less an affirmative act of the State of Georgia. The

seeming passivity of this action was made possible only be

cause of the prior preparation of the situation by other

organs of the State. Nor is a trustee’s “ resignation” either

perfunctory or perfunctorily acceptable; see Bogert, Trusts

and Trustees, §§514-515. (1960). Moreover, the Board of

Managers, an organ appointed by the City Council, and

wielding public power, asked the court for the removal

of the City as trustee, in order that segregation might con

tinue. This action alone would suffice to impart “ state

action” into the pattern; public officials surely may not

take affirmative action, as filing this petition was, for the

confessed purpose of perpetuating segregation. Had the

state court granted this relief on these grounds, the parallel

with Shelley would have been too exact to leave room for

argument. Instead, another holder of state power, the City,

changed its position in the middle of the lawsuit and so

acted as to enable the state court to grant, in practical

effect, the same relief the petition asked for, under the

milder rhetorical figure of “ accepting” a resignation. The

responsibility of the state for the result cannot be affected

by the assignment of different roles in the drama to dif

ferent wielders of state power.

In any event, the action of the state court in appointing

new trustees was altogether affirmative. Those trustees were

appointed in a proceeding commenced by a petition asking

for their appointment on the ground that, if appointed, they

could exclude Negroes. They were appointed directly after

the City had resigned, on the ground, assigned by itself,

that the new trustees could exclude Negroes. This appoint

ment, on the record, is an affirmative judicial act aimed

22

solely at the perpetuation of a discriminatory regime in

Baconsfield.

Nor is it a valid objection that the state court’s refusal to

accept the City’s resignation would have compelled the City

to remain as trustee unwillingly. In the first place, on the

City’s own express admissions, that unwillingness was based

solely on its unwillingness to run the park on an open basis;

this is not the case of compelling service by a trustee as

against general objections, or even as against undisclosed

objections, but rather it is a case of following to its obvious

consequences the rule that no organ of state power may so

act with the intent, purpose and effect exclusively to per

petuate racial discrimination. Nor does it appear that the

City’s being trustee is in any way onerous; to be “ trustee”

is simply to operate the park, a normal municipal function.

(At all events, the policing of this park must to a consider

able extent fall on the City.) Georgia municipalities, more

over, enjoy no general immunity from being compelled to

perform affirmative duties; in McCletchey v. Atlanta, 149

Ga. 648, for example, the City was held compellable by

mandamus to make an annual appropriation for operating a

“ cyclorama” and to build up and keep separate a special

fund for this purpose, in obedience to state law—a com

pulsion more “ affirmative,” if grounded in a less important

power, than a compulsory continuance as trustee, where

resignation is confessedly in furtherance of segregation.

(It seems nearly unnecessary to add that no general state-

law rule, whether common-law or statutory, giving cities

in general the power to resign trusts in general, can prevail

over an obligation of federal constitutional origin, or fix the

quality, for federal constitutional purposes, of the act of

resigning.)

23

Finally, only disorder or needless litigation would flow

from this court’s regarding the ease as not yet raising the

segregation issue, and the state court’s order as not directly

implementing segregation. That order was a first step on a

road clearly marked by the parties, who have candidly

stamped this suit, and the substitution of trustees with

which it terminated, as aimed at segregation only. Peti

tioners insist, then, that far from being inapplicable here,

Shelley governs this case. The only anxiety petitioners

would feel about Shelley is that it would be unfortunate

if any of the questionings about Shelley, any of the uncer

tainty about the scope of its rule, entered this case. If

Shelley had never been decided, this case would still be one

presenting a clear pattern of state action. It is saturated

with state action. No unequivocal private choice is being en

forced. The State of Georgia has chosen among policies,

and has chosen the segregation policy, no more following

the will of a private person than if the opposite choice had

been made. If the order of the state court be thought in

sufficient alone to constitute state action, then one need

only advert to the fact that the whole litigation pattern was

set up for the court’s action by parties who themselves hold

state power, and who confessedly took the actions they took

in order that segregation might prevail.

24

VI.

Respondents Are Wrong in Their Contention That

§69-504, Georgia Code, Acts 1905, p. 117, Is Not a

Significant Consideration in This Case.

Respondents, confronted with Ga. Code §69-504, a statnte

that explicitly spells out legal sanction for racially segre

gated public parks of the Baconsfield sort, insist that that

statute is not a “ significant consideration.” They go on

to say:

In 1904, the year prior to the passage of that statnte,

a testator in Georgia could obviously have created a

trust involving a park with a municipal corporation

as trustee without inserting any racial restriction. Or

he could have created such a trust with a racial re

striction. (Respondents’ Brief, p. 48.) (Emphasis sup

plied.)

Respondents, in this passage, create a mystery they fail

to dispel. Why, if the law of 1904 was so clear, did the

Georgia legislature, in 1905, go to the trouble it did in

passing this section?

Petitioners contend that the answer first suggesting itself

—that Georgia Law was at the least not clear on this

point—is borne out by all the materials now accessible.

First, the Georgia Code of 1895, covering this matter,

seems to name no category including parks as a subject of

charitable trusts. The Code enumeration is as follows:

§4008. (3157.) Subjects of charity. The following

subjects are proper matters of charity for the juris

diction of equity:

25

1. The relief of aged, impotent, diseased or poor

people.

2. Every educational purpose.

3. Provisions for religious instruction or worship.

4. For the construction or repair of public works,

or highways, or other public conveniences.

5. The promotion of any craft or persons engaging

therein.

6. For the redemption or relief of prisoners or cap

tives.

7. For the improvement or repair of burying-

grounds or tombstones.

8. Other similar subjects, having for their object

the relief of human suffering, or the promotion of

human civilization.

“ The promotion of human civilization” would seem a pre

tentious statement of the objective of a park; for a state

court to hold that segregating a park constitutes such a

promotion of civilization would violate the Fourteenth

Amendment. No “ construction or repair” is the principal

subject of this trust. No Georgia court, by the respondents’

own account, had ever held any part of this section ap

plicable to a park, in all the years before §69-504 became

law. This really is enough to establish the entire uncer

tainty, in the Georgia law as Senator Bacon new it, of the

propositions so confidently put forward by the respondents.

There is much more, however. The respondents, ignoring

and not citing the applicable Georgia Code section just

quoted, deal with the matter as one of “ common law.” They

do not tell us why that law in its pristine state applied, in

26

the face of the Code enumeration. More significantly, they

do not advert to the grounds on which other jurisdictions

than Georgia had upheld charitable trusts for parks. Those

grounds were two in number, not unconnected. These are

summarized in 4 Pomeroy Equity §1024, as follows:

4. Other Public Purposes.— Other public purposes,

not in the ordinary sense benevolent, may be valid

charities, since they are either expressly mentioned

by the statute, or are within its plain intent. All of

these purposes tend to benefit the public, either of the

entire country or of some particular district, or to

lighten the public burdens for defraying the necessary

expenses of local administration which rest upon the

inhabitants of a designated region.

There being no Georgia cases, this synthesis of the “ com

mon law” elsewhere is significant. The park, where held

a public charity, is so held because it benefits the whole

public, or because its receipt free of charge lightens the

expense of the performance of a governmental function.

The upholding of racially segregated parks, as objects of

public charity, would be a contradiction in terms on the

first of these theories, and the second of them so deeply

implicates the charitable trust in the governmental plan as

to make its enforcement plainly obnoxious to the Four

teenth Amendment, as against the “ state action” objection.

Thus, as one would confidently expect when so carefully

drawn a statute as §69-504 is put through the state legisla

ture, the prior Georgia law was at least doubtful. It is

against the parts of that law that were not doubtful that

§69-504, and its operation, are to be judged. A very clear

role can be assigned this statute, so mysterious a phenom

enon on respondents’ account, when one adverts to the law

27

of parks in Georgia, as plainly seen in the old Georgia

cases.

As respondents say, “no Georgia case had dealt with a

charity involving a park . . . ” But plenty of Georgia cases

had dealt with parks, treating them, as the common law

traditionally does, as lands “ dedicated to the public,” the

members of the public, as such, having easements of enjoy

ment in them.

The leading case, never lost sight of in later opinions,

is Mayor and Council of the City of Macon v. Franklin, 12

Ga. 239 (1852). In a luminous opinion, Judge Nisbet learn

edly reviews the doctrine of “ dedication,” concluding :

Dedications of lands for charitable and religious pur

poses, and for public highways, are valid without any

grantee to hold the fee, and the principle upon which

they are sustained, sustains dedications of streets,

squares and commons. City of Cincinnati vs. The

Lessee of White, 6 Peters’ R. 435, 436. Beatty vs.

Kurts, 2 Peters’ R. 256. Town of Paulett vs. Clark, 9

Cranch, 292. Lade vs. Shepherd, 2 Stra. 2004. 12

Wheat. 582.

# # # # #

That commons and squares are subjects of dedication,

and under the principles which govern streets and

highways, see the great case of The City of Cincinnati

vs. White’s Lessees, 6 Peters, 431. Watertown vs.

Cohen, 4 Paige R. 510. State vs. Wilkinson, 2 Ver

mont R. 480. Pearsoll vs. Post, 20 Wend, 111. 22 Wend.

425. (12 Ga. at 244-45.)

The holding of the case was that The City of Macon

might not sell for a private use land which it had itself

“ dedicated” to the public as a public square or common.

Other G-eorgia cases treat public parks and analogous

tracts as “ dedicated,” with reciprocal public easements.

Cownty of Gordon v. Mayor of Calhoun, 128 Ga. 781 (1907),

decided a few years after the passage of §69-504, shows

that the Georgia court, which by respondents’ correct ac

count never dealt with a park as the subject of a charitable

trust, thoroughly knew the “ common,” with its accompany

ing public easements, as the legal device by which parks

were maintained as such. See also Pettit v. Mayor and

Council of Maoon, 95 Ga. 645 (1894).

There was, however, one difficulty, not much felt, per

haps, in 1852, the year of Macon v. Franklin, but later a

cloud that could have been seen on the horizon. The “ dedi

cation” that creates a public park is to the public as a whole.

Georgia law was of one voice on this, Ford v. Harris, 95

Ga. 97, 100 (1894); East Atlanta Land Co. v. Mowrer, 138

Ga. 380, 388 (1912); Western Union Telegraph Co. v. Geor

gia Railroad and Banking Co., 227 F. 276 (S. D. Ga. 1915).

The concept of “ dedication” left no room for selecting

parts of the “public” to enjoy the public easement; there

was no middle ground, conceptually, between the public

use, comprehensive as to the public, and the private ease

ment, an unsatisfactory legal basis for operating a public

park.

The expectable trouble developed, not as to parks, but

as to the analogous case of the cemetery. In Brown v.

Gunn, 75 Ga. 441 (1885), “persons of color” claimed, as

members of the public, the right to be buried or to bury

their dead in a cemetery they contended had been “dedi

cated” to the public. The court held, on the facts, that no

“dedication” had taken place, but there was no suggestion,

in the opinion, that such “ dedication” could conceivably,

as a matter of law, have been to the white public only.

29

This, then, was the background of §69-504:

1. No provision in the purportedly exhaustive Code

enumeration authorized the setting up of a charitable

trust for a park.

2. The “ common law” of the subject, outside Geor

gia, generally rested the inclusion of parks in the sub

ject-matter of charitable trusts on two grounds, one

of which was incompatible with, racial exclusion and

the other of which so deeply involved the interests of

government in the operation of the park as to make it

likely that “ state action” would be found.

3. No Georgia case had ever held a park, racially

restricted or not, to be the proper subject of a chari

table trust.

4. Georgia’s public parks were conceived as “ dedi

cated” commons, with corresponding public easements.

This concept, thoroughly familiar to the Georgia court,

had no room for restriction to parts of the public.

Thus, the only sure and well-travelled way of giving

one’s land for a public park—“ dedicating” it to the

public—contained no means of enforcing a racial re

striction.

5. In at least one case that got as far as the state’s

highest court, Negroes, asserting the very claim so

irresistibly suggested by all the foregoing, had sought

to enjoy their easement in “ dedicated” property, and

had been turned away only on a narrow finding of

fact.

Petitioners are emboldened to think that the situation de

fined by these numbered points was the one §69-504 was

designed to meet, because it is the very situation to which

30

it appears to address itself. It reads and sounds like re

medial legislation, and if it was, this was what it was

designed to remedy. In any case, this is the legal back

ground against which it became law.

Against that background §69-504 is no longer the puzzle,

the mystery, that respondents have made of it. That sec

tion supplies the one thing needful—permission to give

land as a park with racial restrictions—and it supplies

that alone. Before it was passed, anybody who wanted to

give his land as a park for the whole public could “ dedi

cate” it, in the time-honored way. The single practical

change the section made was that he now could restrict

his gift racially—not in general or in any way he wished,

but only racially.

The 1905 statute, then, by the leave and only by the

leave of which this racially restrictive term was inserted

in Senator Bacon’s will, was a specifically hostile state

act against the colored race, authorizing clearly, for the

first time in Georgia law, their exclusion from parks other

wise public. That was its minimum effect. Here we have

what one would never have expected to encounter in such

explicit clarity, literally that very thing which Mr. Justice

Stewart, concurring in Burton v. Wilmington Parking Au

thority, 365 U. S. 715 at 727 (1961), found by inference:

“ . . . This legislative enactment . . . authorizing discrimi

nation based exclusively on color.” Here is no mere gen

eral declaration of a right to discriminate on any grounds,

but rather on the one hand the lending of Georgia’s law

sanction, for the first time so far as one can tell, to chari

table trusts for public parks, with the proviso that racial

discrimination and that discrimination alone, is to be per

mitted—and, on the other hand, the plugging of a loophole

31

that had made racial discrimination difficult in the law of

public parks as it actually had existed in Georgia. Surely

one may say, as Mr. Justice Stewart said in Burton, “ Such

a law seems . . . clearly violative of the Fourteenth Amend

ment.” 365 U. S. at 727.

This is the minimum effect of this statute. But is it not

also clear that, against this background, any citizen must

see that the state is at least suggesting discrimination!

Even on respondents’ own account, is this not the necessary

effect of such a statute? If it were, as they contend, merely

declaratory of one consequence of a general capacity in

testators to discriminate in any manner, must it not for

that very reason function as a mark of the state’s special

interest in this form of discrimination? Against the legal

backdrop that actually existed, on the other hand, it must

surely signal to all a state policy of fostering and favoring

segregation, evidenced in the most convincing manner by

solicitude to make such segregation possible against all

previous objections of a technical cast.

Finally, a careful lawyer, seeing in §69-504 his only re

liable Georgia authority for setting up a trust for a park,

might well be afraid to count on a later time’s reading of

a statute so clearly racial in its thrust. The verbal prob

lem he would have would not be, as respondents would

have this Court believe, that of the meaning of the "word

“may.” The problem would be whether the act which, under

the statute, the testator “ may” perform is (1) the convey

ance of land for a park with or without any of the condi

tions enumerated; or (2) the conveyance of the land to

gether with the one he chooses from among those conditions.

Stranger feats of statutory construction have been per

32

formed than a court’s reading this language to have the

latter meaning.

This general point is not, however, the only reliance in

this case. What Senator Bacon actually did, in the first

instance, was to leave his land in trust as a park for the

white women and children of Macon (R. 19). Now §69-504,

on its face and with no ambiguity whatever, fails to au

thorize a gift to women and children on an unsegregated

basis. It authorizes a gift for white women and children

only, or for colored women and children only, or for women

and children of any other race only, but none for women

and children of all races together. Had Senator Bacon,

therefore, wished to leave his park for all women and chil

dren, he would have had to conclude that he could not law

fully do so under §69-504, and that if he tried to do so on

an alternative “ common law” theory he would be met not

only by all the difficulties above discussed, but also by the

powerful argument that this carefully drawn statute, enu

merating permitted discriminations, excluded others by im

plication. The Board of Managers, to be sure, later opened

the park to all whites. But Bacon could not have known

they would, and authorized them not to. Under §69-504,

he could not have authorized them to exclude all men, and

admit all women and children.

The actual effect of all this on Senator Bacon’s mind is

not important. Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U. S.

244. What is important is that the State of Georgia, in

passing this statute:

(1) Supplied the specific thing its law had lacked—

a clear means for a private person’s giving his land

for a “public” park on racially discriminatory terms.

33

(2) In the context of prior law, signalled the state’s

anxious interest in seeing racial discrimination (rather

than mere general “ freedom of choice” ) authorized and

practiced.

(3) Engendered legal doubt that any trust for a park

would be valid without racial discrimination, and, un

less its readable text and normal implications be

ignored, made flatly unlawful the non-racist rule of

admission—“women and. children only”—correspond

ing to the racist rule—“white women and children

only”—actually adopted in this case, thus in effect com

manding segregation by race if a “women and children”

park was wanted.

Respondents say that this section is “ not significant,” and

that petitioners’ attempt to have the Court view it as being

so “will not bear analysis.” On the foregoing considera

tions, petitioners submit that respondents have mistaken

the position.

CONCLUSION

The acceptance of the City’s resignation and the appoint

ment of new trustees constituted a judicial action con

firmatory of actions of other organs of state power, hav

ing the express sole aim of reinstituting racial discrimina

tion in Baconsfield. While petitioners strongly urge that

this renewed segregation is in itself illegal, the decree en

tered violates the Fourteenth Amendment, on either of the

two possible views as to the latter question. Respondents’

arguments fail to cast serious doubt on this conclusion.

34

Petitioners therefore renew their prayer that the judg

ment of the Supreme Court of Georgia be reversed, and

that the reversal of the Superior Court’s decree be ordered.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. Narrit, III

Michael Meltsner

Charles Stephen R alston

F rank H. Heeeron

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Charles L. Black, Jr.

346 Willow Street

New Haven, Conn. 06511

D onald L. H ollowell

W illiam H. A lexander

H oward Moore, J r.

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

Attorneys for Petitioners

,-1