Walker v. Georgia Supplemental Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

May 24, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Walker v. Georgia Supplemental Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1965. 6323053b-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f2fc1458-e6de-42f7-8542-aa837d2e6618/walker-v-georgia-supplemental-brief-in-opposition-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

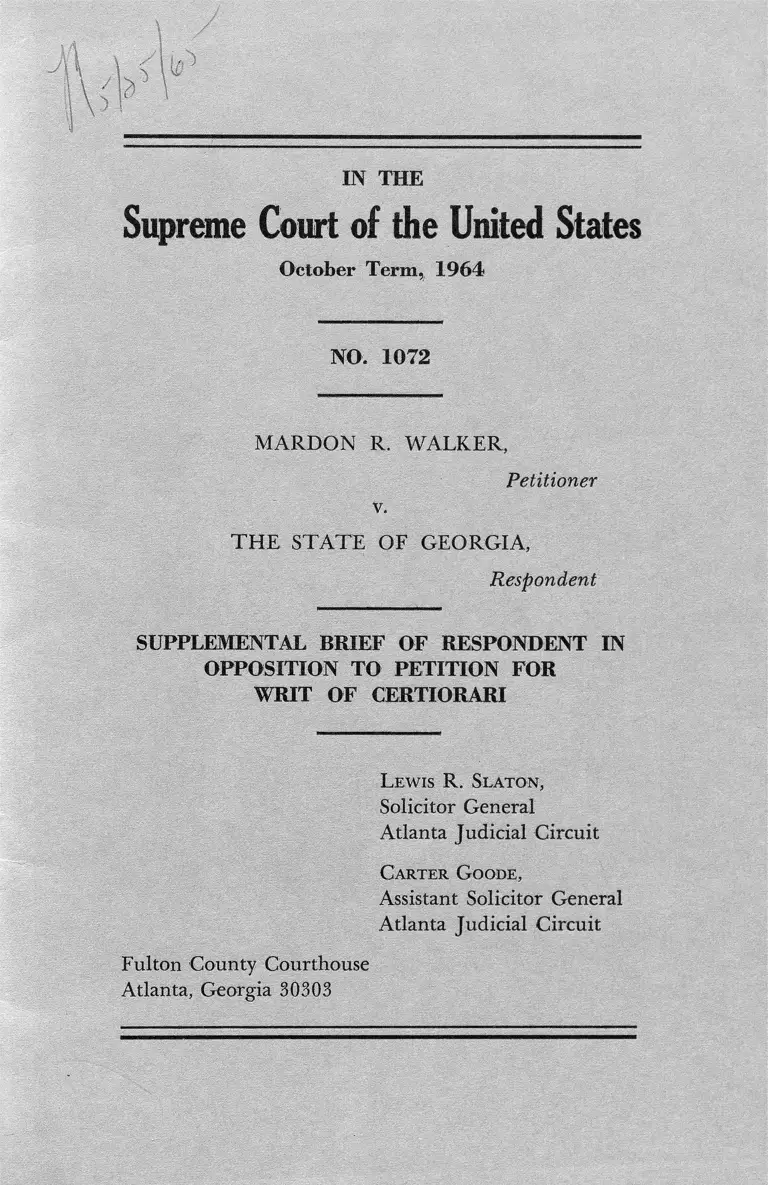

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1964

NO. 1072

MARDON R. W ALKER,

Petitioner

T H E ST A T E OF GEORGIA,

Respondent

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF OF RESPONDENT IN

OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR

WRIT OF CERTIORARI

L ewis R. Sla to n ,

Solicitor General

Atlanta Judicial Circuit

C arter G oode,

Assistant Solicitor General

Atlanta Judicial Circuit

Fulton County Courthouse

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1964

NO. 1072

MARDON R. W ALKER,

v.

Petitioner

T H E STA TE OF GEORGIA,

Respondent

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF OF RESPONDENT IN

OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR

WRIT OF CERTIORARI

In our original brief we said:

“We are unable to reconcile the opinion below,

as it relates to the question whether Krystal at

70 Peachtree Street is a place of public accommo

dation within the meaning of Title II of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, with Bolton v. State, 220 Ga.

632, 140 S.E. 2d 866 on the same point. In Bolton,

decided February 8, 1965, Hamm and Lupper,

supra, are followed, in a factual situation which

appears to us to be indistinguishable from that in

1

2

this case. We are therefore in the position of the

State of Arkansas in the Lupper case. (See 85 S. Ct.

384, 1964, note 3, at page 388), and feel that a

remand on the issue of coverage would not serve

any useful purpose.

Before leaving this area, we can state that we

would, if the question of abatement were still open,

point out that Georgia has a savings law3 which

expresses a state policy to save convictions, and as

to abatement take generally the positions of the

dissenting Justices in Hamm and Lupper, supra.”

It has come to our attention that the twO! questions,

whether Krystal is a place of public accommodation

within the meaning of Title II of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, and whether the demonstrators were disorderly

or the demonstration forcible, may not have been devel

oped sufficiently on the trial.

We quote the Supreme Court of Georgia in the opin

ion below (220 Ga. at p. 426) , referring to coverage by

the Act:

“T o demonstrate the fallacy of the defendant’s

argument that this court should grant the motion

for new trial on account of the passage of the

Civil Rights Act, whether this particular restaurant

comes within the provisions of the Civil Rights

Act depends upon whether it is a place of public

accommodation within the meaning of the Act. The

Act, section 201, provides that a restaurant is a

“3 Ga. Code Ann. Sec. 26-103: All crimes shall be prosecuted

and punished under the laws in force at the time of the commis

sion thereof, notwithstanding the repeal of such laws before such

trial takes place, cf. Jackson v. State, 12 Ga. 1, 4; Crosby v.

Courson, 181 Ga. 475, 182 S.E. 590.” .

place within the meaning of the Act ‘if its operations

affect commerce, or if discrimination or segregation

by it is supported by State action.’ It is readily

apparent that the determination of that question

is one of fact, which can only be made in the trial

court.”

Obviously, a determination whether the occurrence

was peaceful and non-forcible should also be made in

the trial court.

We have never intended to imply that we consider

the question of abatement foreclosed by Hamm, and

Lupper, or Blow or McKinnie, in any case where the

demonstrators were disorderly or the demonstration

forcible. We feel that on the record now before the

court, the applicant and her fellow demonstrators were

engaged in a common enterprise in which each, as a

matter of law, was criminally responsible for the acts of

the others. In its present condition, the record shows

that the conduct of the group of demonstrators in the

demonstration in which applicant was a participant was

disorderly, and the demonstration forcible and violent.

We share the misgivings of the Supreme Court of

Georgia about Hamm and Lupper expressed in Bolton,

(220 Ga. at p. 633) :

“In those two cases the majority held that the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbids discrimination in

specified places of public accommodation and removes

peaceful attempts to be served on an equal basis

from the category of punishable activities. While

those majority holdings do not accord with our

conception of the meaning and purpose of the pro

visions of the Constitution of this State and the

4

Constitution of the United States which prohibit the

enactment of ex post facto or retroactive laws (Code

sec. 1-128, 2-302), we are, under our oaths, never

theless required to follow them and we will there

fore do so in these cases; and being so required,

we therefore hold that these pending convictions

are abated by the 1964 Civil Rights Act and it is

ordered that the sentences imposed on each of these

defendants be vacated and that the charge against

each defendant be dismissed.”

We cannot say too many times that no departure from

the requirements that demonstrations be peaceful, or

derly and nonviolent should be tolerated. Any other

approach would be to legalize anarchy.

Headnote 5 of the opinion below (220 Ga. at page

416) is as follows:

“This court has no original jurisdiction and is

limited to the trial and correction of errors of law

from the superior courts and other enumerated

courts of this State. Code Ann., Section 2-3704.

Thus the contention made in the general grounds

of the motion for new trial that the enactment into

law of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by the Congress

abates defendant’s conviction and prevents her pun

ishment for violating the Georgia anti-trespass Act

raises no question for consideration by this court,

as this question was not raised or passed upon in

the trial court.”

This ruling is in accord with the Constitution of the

State of Georgia (Art. 6, Par. 4) whereby the jurisdic

tion of the Supreme Court is limited to the correction

of errors of law from the Superior Courts and the City

5

Courts of Atlanta and Savannah and like Courts. The

Supreme Court of Georgia has no original jurisdiction,

has no jurisdiction to pass upon a question not deter

mined in the Court below, and in Headnote 5 above,

gave recognition to this constitutional inhibition.

It is the law of Georgia that in this case the question

whether the case should abate on account of the passage

of the Civil Rights Act must be first determined in the

trial court. The question whether this case abates by

the Civil Rights Act does not now exist in this case.

The Supreme Court of Georgia was without jurisdiction

to consider this question, did not consider it, but ex

pressly ruled that it could not do so, and we respectfully

submit the question cannot be considered by the

Supreme Court of the United States at this stage of the

case. The only way this question can get into the case

is by defendant raising the question in the trial court;

if the trial court holds the case is not abated by the

passage of the Civil Rights Act, defendant may except

in regular course.

It is elementary that only matters in issue can be

adjudicated. One reason is that only thus do the parties

have notice enabling them to present their evidence.

The question whether this case should be abated under

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was not in issue before the

trial court, thus was not within the jurisdiction of the

Supreme Court of Georgia to determine, and is not now

before the Supreme Court of the United States. T o select

portions of the evidence bearing on the effect of the

Civil Rights Act and to adjudicate therefrom whether

the case should thereby be abated, when this matter

was not put in issue before the trial court so that the

6

parties could knowingly present evidence thereon, would

be to depart from the ordinary course of judicature.

Additionally, it should be remembered that defendant

filed a second motion for rehearing in the Supreme Court

of Georgia on March 1, 1965, presenting the Civil Rights

Act and the case of Bolton versus State, 220 Ga. 632.

The Supreme Court held on March 15, 1965, that it

was without authority under the rules of the Court to

permit the filing of this second motion for rehearing.

This prosecution should not abate.

Respectfully submitted.

L ewis R. S la to n ,

Solicitor General

Atlanta Judicial Circuit

C arter G oode,

Assistant Solicitor General

Atlanta Judicial Circuit

Counsel for Respondent,

State of Georgia

Fulton County Courthouse

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

7

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

GEORGIA, FU LTO N CO UNTY

I, Carter Goode, of counsel for the State of Georgia,

respondent in the foregoing case, certify that I have this

day served copies of the foregoing Supplemental Brief

of Respondent in Opposition to Petition for Writ of

Certiorari upon Petitioner, by depositing in the United

States Post Office in Atlanta, Georgia, two copies of same

in an envelope addressed to Jack Greenberg, attorney,

Suite 2030, 10 Columbus Circle, New York, New York,

10019, and two copies of same in an envelope addressed

to Donald L. Hollowell and Howard Moore, Jr., Attor

neys, 859V2 Hunter Street, N. W., Atlanta, Georgia,

30314, counsel of record for petitioner, with sufficient

first class postage affixed thereto.

This May___ «i2. 4 ______, 1965.

s/ •C_, <3., *-» ̂ L . ^5"© ® c / C —

7 C arter G oode

Assistant Solicitor General

Atlanta Judicial Circuit