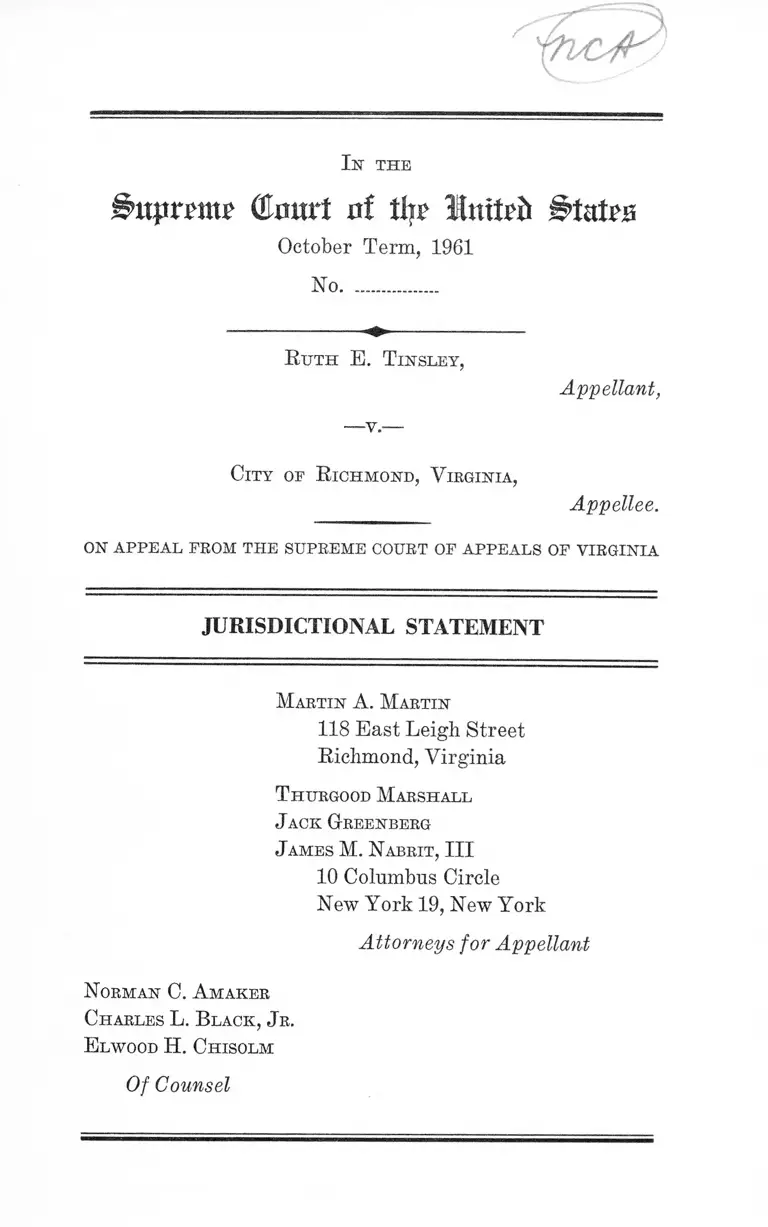

Tinsley v. City of Richmond, Virginia Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Tinsley v. City of Richmond, Virginia Jurisdictional Statement, 1961. 4ac2813b-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f3188654-6370-4a89-83a1-8fa89545af68/tinsley-v-city-of-richmond-virginia-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

mptmt (tart uf % llmttb Btutez

October Term, 1961

No..................

R uth E. T insley,

Appellant,

City of R ichmond, V irginia,

Appellee.

ON APPEAL PROM THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Martin A. Martin

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond, Virginia

T hurgood Marshall

J ack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellant

Norman C. A maker

Charles L. Black, J r.

E lwood H. Chisolm

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Citation to Opinion B elow .... ........ .................................. -

Jurisdiction ...............................-....................... -.................

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved .....

Question Presented ........... .................................................

Statement ..............................................................................

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and De

cided ...................... ................. ----- -------------- ---------—

The Questions Are Substantial ........... ...........................

Conclusion ..............................................................................

2

2

3

3

3

7

8

14

A ppendix ............ 15

Opinion Below ............. 15

Judgment ..... 25

C i t a t i o n s :

Cases:

Atlantic Coast Line R. Co. v. Goldsboro, 232 IT. S. 548 .. 2

Benson v. Norfolk, 163 Va. 1037,177 S. E. 222 (1934) .... 12

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 .................................... 8

Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 TJ. S. 495 ...................................... 10

11

Chapman v. Crane, 123 U. S. 540 .................................... 2

Commonwealth v. Carpenter, 325 Mass. 519, 91 N. E. 2d

666 (1950) ........................................................................ 8,11

Commonwealth v. Challis, 8 Pa. Superior Ct. 130 (1898) 12

Commonwealth v. Slome, 321 Mass. 129 ...................... 12

Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U. S. 385 ..10,12

Deer Park v. Schuster, 16 Ohio Ops. 485, 30 Ohio L.

Abs. 466 (1940) .............................................................. 8,11

Dorchy v. Kansas, 272 U. S. 306 ...................................... 2

Ex parte Mittelstaedt, 164 Tex. Grim. 115, 297 S. W. 2d

153 (1956) ........................................................................ 9,11

Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization, 307

U. S. 496 .......................................................................... 8

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 8 1 ................... 9

Kunz v. New York, 340 U. S. 290 ................................... 8

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451 .......................10,12

Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee, 1 Wheat. 304 ....................... 13

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268 ........................... 8

People v. Diaz, 4 N. Y. 2d 469,151 N. E. 2d 871 (1958) ..8,11

People v. Johnson, 6 N. Y. 2d 549, 161 N. E. 2d 9 (1959) 12

People v. Merrolla, 9 N. Y. 2d 62, 172 N. E. 2d 541

(1961) ................................................................................ 12

People v. Wiener, 254 App. Div. 695, 3 N. Y. S. 2d

974 (1938) .............................. 8,11

Pinkerton v. Verberg, 78 Mich. 573, 44 N. W. 579 (1889) 9

PAGE

I l l

Saia v. New York, 334 IT. S. 558 ................................... 8

Schneider v. Irvington, 308 U. S. 147 ........................... 8

Soles v. Vidalia, 92 G-a. App. 839, 90 S. E. 2d 249

(1955) ................................................................................8,11

St. Louis v. Gloner, 210 Mo. 502, 109 S. W. 30 (1908) ..8,11

State v. Hunter, 106 N. C. 796, 11 S. E. 366 (1890) .... 8

State v. Starr, 57 Ariz. 270, 113 P. 2d 356 (1941) .... 12

State v. Sugarman, 126 Minn. 477,148 N. W. 466 (1914) 12

Tacoma v. Roe, 190 Wash. 444, 68 P. 2d 1028 (1937) .... 13

Territory of Hawaii v. Anduha, 48 F. 2d 171 (9th Cir.

1931) ....................................... ..........................................8,11

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 ...........................9,14

Union National Bank v. Lamb, 337 U. S. 3 8 ................... 2

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 ............................... 12

Zucht v. King, 260 IT. S. 174 ............................................ 2

Other Authorities:

American Law Institute, Model Penal Code, Tentative

Draft No. 13 ....................................................................9,13

Douglas, “Vagrancy and Arrest on Suspicion,” 70 Yale

L. J. 1 (1960)

PAGE

14

I n t h e

kapron* (Emtrt nt % MnxUb States

October Term, 1961

No.................

E uth E. T insley,

Appellant,

— y.—

City of E ichmond, V irginia,

Appellee.

ON APPEAL FROM THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Appellant, Euth E. Tinsley, appeals from the judgment

of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, entered on

April 24, 1961, affirming a judgment of the Hustings Court

of the City of Eichmond, Virginia, convicting appellant of

violating a municipal ordinance, and submits this State

ment to show that the Supreme Court of the United States

has jurisdiction of the appeal and that a substantial ques

tion is presented. In the alternative, should the Court re

gard this appeal as having been improvidently taken, ap

pellant prays that this Statement be regarded and acted

upon as a petition for a writ of certiorari in accordance

with 28 U. S. C. §2103.

2

Citation to Opinion Below

The Hustings Court of the City of Richmond did not

render an opinion in this case. The opinion of the Supreme

Court of Appeals of Virginia (R. 31) is reported at 202 Va.

707, 119 S. E. 2d 488, and is printed in the Appendix here

to, infra, p. 15.

This is a criminal proceeding in which appellant was

convicted in the Hustings Court of the City of Richmond

on April 11, 1960, of violating §24-17, Code of the City of

Richmond, Virginia (R. 4). Appellant petitioned the Su

preme Court of Appeals of Virginia for a writ of error

contending there and below that the ordinance under which

she was convicted was unconstitutional under the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States. Writ of error was granted

(R. 1 ); April 24, 1961, the Supreme Court of Appeals

affirmed the conviction, sustaining the validity of the ordi

nance in question (R. 46).

Appellant filed Notice of Appeal in the Supreme Court

of Appeals on July 24, 1961. Jurisdiction of the Supreme

Court of the United States to hear this appeal rests upon

28 U. S. C. §1257(2).

The following decisions sustain the jurisdiction of this

Court to review the judgment by appeal in this case:

Atlantic Coast Line R. Co. v. Goldsboro, 232 U. S. 548,

555; Zucht v. King, 260 U. S. 174, 176; Union National

Bank v. Lamb, 337 U. S. 38, 40-41; Chapman v. Crane, 123

U. S. 540, 548; Dorchy v. Kansas, 272 U. S. 306, 308-309.

Jurisdiction

3

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions Involved

1. This case involves the validity of Section 24-17 of the

Code of the City of Richmond, Virginia, 1957:

Any person loitering or standing on the street, side

walk or curb, shall move on or separate when required

to do so by any member of the Police Bureau and shall

cease to occupy such position on the street, sidewalk,

or curb.

2. This case also involves section 1 of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Question Presented

Whether a city ordinance punishing disobedience of a

policeman’s order to any person on the street to move on,

but articulating no standard to guide the police, the courts,

or the public, violates the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States,

where applied to convict and punish appellant.

Statement

Appellant, Ruth E. Tinsley, was arrested in Richmond,

Virginia on February 23, 1960, on a warrant charging that

on that day she did “unlawfully refuse to move on when

told to do so by police officer D. L. Nuckols in violation of

Section 24-17 of the City Code” (R. 3). Appellant was

brought before the Hustings Court of the City of Rich

mond, entered a plea of not guilty, and elected to be tried

by the Court without a jury (R. 4-5). She was found

guilty and a ten dollar fine was assessed on April 11, 1960

4

(R. 4). The Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia granted

a writ of error (R. 1), and on April 24, 1961, affirmed the

judgment below (R. 46).

On February 23, 1960, at 3:55 p.m. (R. 13), appellant,

Mrs. Ruth E. Tinsley, a Negro1 58 years of age, a long-time

resident of Richmond and the wife of a practicing dentist in

the City, was standing on the sidewalk near the corner of

Sixth and Broad Streets in downtown Richmond (R. 22).

She was standing under a clock, near a glass window of

Thalhimer’s Department Store while waiting, as she had

done frequently in the past, to meet a friend (R. 22, 23,

24). The sidewalk was sixteen and a half feet wide; ap

pellant was about thirty-five feet from the curb-line of the

nearby corner (R. 14-15). She was alone, talking to no one,

and was not at all disorderly (R. 17). People were walking

up and down the sidewalk; no one was blocking it (R. 18).

Before reaching this corner, someone had given her a

handbill stating “ don’t buy where you cannot eat, and turn

your charge plate in, and something else” (R. 22). There

upon, she decided not to enter Thalhimers, but merely to

wait for her friend. (R. 23, 24).

That day the downtown area was crowded and a group of

pickets was walking back and forth at Thalhimers. Patrol

man Nuckols had been assigned to patrol the area with his

trained attack dog, and to keep everyone in the area moving

because of the picketing (R. 12). A newsboy earlier had

been required to move from the corner, but later obtained

permission to remain and sell papers (R. 13); persons wait

ing for buses had been directed to stand away from the

building (R. 8 ); plainclothesmen were instructed to keep

1 The designation “ CF” , meaning colored female appears in the

warrant (R. 3).

5

moving (E. 9). All this was said to be part of a police effort

to keep the sidewalks open and avoid trouble in the area of

picketing (R. 9), Nothing in the record indicates that Mrs.

Tinsley was aware of any of these police activities or the

reasons for them.

As soon as Mrs. Tinsley stopped at the store window,

officer Nuckols approached her. He testified (E. 13-14):

Q. Tell the Court exactly what happened as you ap

proached Mrs. Tinsely? A. Well, before I got to Mrs.

Tinsley I had asked some people were they waiting for

the bus, and they said that they were. I said would

you mind waiting for the bus at the bus stop. They

moved over there, and I passed the Sixth Street door

and Mrs. Tinsley was standing there, and I said that

she would have to keep moving on. She stated why

have I got to move. I said “Do you mind, please, to keep

moving on?” She said how about them people there?

I said that I hadn’t got to them yet. By that time it was

two gentlemen standing at the corner and they moved.

She said are you going to tell me the reason why I

have got to move. I said move, said that in a tone of

voice where she was sure to hear, if she had been hard

of hearing she certainly could have heard it. She had

some packages in her hand, handbag, and she did like

this (indicating by stamping foot).

Q. So you asked her to move twice, please to move

on? A. The first time I asked her “Would you mind,

keep moving.” The second time “Please move.” And

the third time I said “ Move.”

Q. Did she move? A. No, sir. I placed her under

arrest.

6

On cross examination, the officer testified (E. 25) :

Q. And the only thing that happened was you ordered

her, I think on two occasions, twice on the same oc

casion, to move, and each time she asked you why.

Why must she move. You never did tell her why she

should move, did you? A. No, sir.

Q. And then you just arrested her without telling

her why you were arresting her, or why she was re

quired to move? A. (Pause) No, I didn’t tell her

why she had to move (E. 18-19).

Appellant repeatedly testified that all she wanted to

know was “ why” she had to move on (E. 25):

Q. Did you have any intention of violating any law?

A. I had no intention. That is why I wanted to know

why.

Q. Did you know you were violating any law? A. I

didn’t know I was violating a law, because I thought

you could ask why. That is all I wanted to know, was

why. . . .

# * * * *

A. I didn’t know where I had to go. People were cross

ing the street. There were people on the curb. There

were people around everywhere. I wanted to know why

that I had to move on.

The record contains no evidence of violence or appre

hension of violence in the vicinity; nor does it reveal that

normal passage of the sidewalk was blocked; nor does it

display any reason why a citizen in the normal course

of events might anticipate that he ought not to occupy

a place on the street, except, of course, the officer’s com

mand to move on.

7

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

At the beginning of trial, appellant’s counsel orally

moved to dismiss the warrant on grounds that the ordi

nance violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States, “ on its face” and “ in its applica

tion to this particular case” , because of its vagueness and

because it gave the police officer unfettered authority to

require citizens to move on (R. 6-7). The Court overruled

the motion (R. 7).

On appeal, among the errors assigned was a claim that

the ordinance “ grants unlimited and unfettered authority

to any police officer in the City of Richmond, Virginia, to

require citizens on the street to separate or move on, with

out limitations, and therefore violates the Constitution of

Virginia and the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the

Constitution of the United States” ; and a further claim

that “ said section is so vague as to violate the Constitution

of the State of Virginia and the Constitution of the United

States” (R. 2-3).

In affirming the conviction, the Supreme Court of Appeals

of Virginia rejected all of the claims urged by petitioner

in her assignments of error. The opinion below did not

discuss the issues presented by appellant’s assignments of

error specifically in terms of the Fourteenth Amendment.

However, the Court did treat and reject appellant’s argu

ments and clearly sustained the validity of the statute.

The Court held that the delegation of discretionary power

to police officers under this ordinance was justified by the

impracticability of prescribing a more definite rule (R. 35),

saying that “ the failure to set out a specific standard of

conduct in the ordinance does not render the ordinance

void” (R. 36); held that the officer on the facts of this

case acted “ reasonably” (R. 41-42); and that the statute was

8

sufficiently definite and was not “unconstitutional and void

for the reason assigned” (R. 42). It is abundantly clear

that disposition of the Fourteenth Amendment objections

to the validity of the ordinance was necessary to a deter

mination of the case, and that the ordinance was sustained

against these challenges.

The Questions Are Substantial

This case involves a substantial constitutional issue af

fecting an important aspect of personal liberty, the right

to make peaceful and ordinary use of public streets free

from police interference under a criminal ordinance grant

ing policemen absolute discretion to order persons to

“move along.”

The right to use the public streets is so clearly an as

pect of personal liberty that the point need not be labored,

as “ [ljiberty under law extends to the full range of con

duct which the individual is free to pursue, . . . ” 2 It

should be sufficient to note that liberty to use the streets is

recognized in many decisions involving free speech, as

sembly, and religion,3 as well as in cases involving loiter

ing4 and curfew laws.5

2 Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, 499.

3 See Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization, 307 U.S.

496, 515-516; Schneider v. Irvington, 308 U.S. 147, 160; Saia v. New

York, 334 U.S. 558, 561, note 2; Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S.

268; Kunz v. New York, 340 U.S. 290.

4 Deer Park v. Schuster, 16 Ohio Ops. 485, 30 Ohio L. Abs. 466

(1940) ; St. Louis v. Gloner, 210 Mo. 502, 109 S.W. 30 (1908) ;

People v. Diaz, 4 N.Y.2d 469, 151 N.E.2d 871 (1958); State v.

Hunter, 106 N.C. 796, 11 S.E. 366 (1890); Soles v. Vidalia, 92 Ga.

App. 839, 90 S.E.2d 249 (1955); Commonwealth v. Carpenter, 325

Mass. 519, 91 N.E.2d 666 (1950) ; Territory of Hawaii v. Anduha,

48 F.2d 171 (9th Cir. 1931). Cf. People v. Wiener, 254 App. Div.

9

The ordinance invoked against appellant furnishes no

guide to define circumstances under which an officer may

direct a person to move on. This is left entirely to police

discretion. The only check on police discretion is subse

quent judicial review in a criminal prosecution in which

Virginia courts apply a generalized conception of “ rea

sonableness” . The ordinance permits a policeman to or

der a person about the streets for any reason a police

man deems fit and subjects the citizen to the peril of

criminal punishment if he fails to move. The citizen is

criminally liable if, upon judicial consideration of various

circumstances not mentioned in the ordinance, nor defined

elsewhere, a court determines that the police demand was

reasonable. The invitation to official abuse in this ordi

nance is amply illustrated by the present case. Officer

Nuckols simply demanded that appellant leave, refused to

answer her repeated simple question as to why, repeated

his demand more loudly, and then arrested her. The court,

in determining that his actions were “ fully justified” by the

circumstances (R. 42), approved his refusal to answer ap

pellant’s simple question and concluded that the “ officer was

under no obligation to stand and argue with the defen

dant.” 5 6

695, 3 N.Y.S.2d 974 (1938) ; Ex parte Mittelstaedt, 164 Tex. Crim.

115, 297 S.W.2d 153 (1956). In Pinkerton v. Verberg, 78 Mich.

573, 584, 44 N.W. 579 (1889), the court said: “Personal liberty,

which is guaranteed every citizen under our Constitution and laws,

consists of the right of locomotion,—to go where one pleases, and

when, and to do that which may lead to one’s business or pleasure,

only so far restrained as the rights of others may make it necessary

for the welfare of all other citizens.”

5 Cf. Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81, 111 (concurring

opinion) describing a curfew as a restraint upon “liberty.”

6 Cf. Thompson v. Louisville, infra. With reference to alterca

tion with policemen see also American Law Institute, Model Penal

Code, Tentative Draft No. 13, pp. 13-18. (The reporters observed,

at p. 14: “Hostility to policemen among considerable groups in the

10

The ordinance, as thus expounded, clearly contains no

readily ascertainable standard of guilt or criminality which

fairly warns a citizen that his conduct is prohibited. To

be sure a citizen will know when he has not obeyed a com

mand to move on. But neither the officer making such a

demand, nor the citizen subjected to it, nor the court later

reviewing it, is furnished by the statute with any stand

ards for determining whether the policeman’s command

is one which may be safely disregarded (an “ unreasonable”

order) or must be obeyed to avoid a violation of law (a

“ reasonable” order ). This determination can only be made

by the courts (themselves operating in terms of a vaguely

defined conception of reasonableness based upon circum

stances possibly unknown to the defendant) on an ad hoc

basis after the fact.

The courts have long recognized that one of the evils

of vague criminal laws is that they confer upon judges

and jurors the discretion to punish actions not clearly de

fined. See Connally v. General Construction Company, 269

TJ. S. 385, 395 (“ varying impressions of juries” ) ; Burstyn

v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495, 532 (Mr. Justice Frankfurter, con

curring) (law did not “ sufficiently ax^prise . . . of what may

reasonably be foreseen to be found illicit by the law enforc

ing authority, whether court or jury or administrative

agency” ). See, generally, Lametta v. New Jersey, 306

IT. S. 451.

Of course, it might be argued that a citizen could obey

every police command and thereby gain safety from the

Richmond ordinance; but this would require the peaceful,

population rests in part on a feeling that /arrests often reflect

affront to the policeman’s personal sensibilities rather than vindi

cation of the public interest.] It would therefore improve police

prestige if the law and police administration took a conservative

approach to penalizing petty wounds to policemen’s sensibilities.” )

11

harmless citizen to submit to every police demand on the

public street, no matter how arbitrary or irrational. Many

state courts have condemned loitering ordinances which,

like the one in this case, were so vague that they failed

to define the prohibited conduct.7 These eases illustrate the

prevalent judicial abhorrence of vague loitering laws.

In Commonwealth v. Carpenter, 325 Mass. 519, 91 N. E.

2d 666 (1950), the highest court of Massachusetts invali

dated a law similar to that in the present case. That law

provided in relevant part that “No person shall, in a street,

unreasonably obstruct the free passage of foot-travelers,

or willfully and unreasonably saunter or loiter for more

than seven minutes after being directed by a police officer

to move on. . . ” . The Court observed that the portion of

the law relating to obstruction of travel was not in issue

and that no violence or breach of the peace was involved.

Thus the reasoning of the Court is equally applicable here.

The Court said at 325 Mass. 519, 521-522, 91 N. E. 2d 666,

667:

In the view we take, the facts are unimportant. The

part of the ordinance here considered we hold to be

void on its face as repugnant to the due process clause

of §1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States and to Art. 12 of the .Declaration

of Rights of the Constitution of this Commonwealth.

It undertakes to make criminal an intentional and un

reasonable failure by one on a street to move on as

soon as seven minutes have elapsed after a direction

7 St. Louis v. Gloner, supra; People v. Diaz, supra; Deer Park

v. Schuster, supra; Soles v. Vidalia, supra; Territory of Hawaii

v. Anduha, supra; Commonwealth v. Carpenter, supra; Ex parte

Mittelstaedt, supra. See also People v. Wiener, 254 App. Div. 695,

3 N.Y.S.2d 974 (1938) (invalidating a law prohibiting disobedi

ence to police officers’ commands).

12

to that end given by a police officer. Prima facie, mere

sauntering or loitering on a public way is lawful and

the right of any man, woman, or child. This the Com

monwealth concedes. Under the ordinance, such con

duct continues conditionally lawful subject to a direc

tion to move on by a police officer followed by unrea

sonable failure to comply and the expiration of seven

minutes. Not all idling is prohibited, but only that

which is unreasonable. The vice of the ordinance lies

in its failure to prescribe any standard capable of in

telligent human evaluation to enable one chargeable

with its violation to discover those conditions which

convert conduct which is prima facie lawful into that

which is criminal. A “ statute which either forbids or

requires the doing of an act in terms so vague that men

of common intelligence must necessarily guess at its

meaning and differ as to its application, violates the

first essential of due process of law.” Connally v.

General Construction Co., 269 U. S. 385, 391; Lanzetta

v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451, 453; Winters v. New

York, 333 U. S. 507, 515-516; Commonwealth v. Slome,

321 Mass. 129, 133-134. (Emphasis supplied.)

Moreover, cases upholding loitering laws have approved

only ordinances containing standards for the exercise of

police discretion, i.e., limiting their application to certain

areas, times, and circumstances.8 These cases demonstrate

8 See, for example, State v. Sugarman, 126 Minn. 477, 148 N.W.

466 (1914) (obstructing sidewalk) ; Tacoma v. Roe, 190 Wash. 444,

68 P.2d 1028 (1937) (same); Commonwealth v. Challis, 8 Pa.

Superior Ct. 130 (1898) (same); State v. Starr, 57 Ariz. 270,

113 P.2d 356 (1941) (limited as to certain times in specific area

near schools and in terms of absence of “ legitimate reason” ) ;

People v. Johnson, 6 N.Y.2d 549, 161 N.E.2d 9 (1959) (in schools) ;

People v. Merolla, 9 N.Y.2d 62, 172 N.E.2d 541 (1961) (within

in 500 feet of dock or pier). An apparent exception is Benson v.

Norfolk, 163 Ya. 1037, 177 S.E. 222 (1934).

13

the feasibility of drafting municipal ordinances so as to

limit police discretion to dealing with clearly defined evils.

Loitering laws which prevent obstruction of the streets,

authorize quelling potential riots, or which serve other

valid, defined legislative ends, need not confer on police

officers unlimited power to restrain the liberty of citizens

using the public streets.9

The conflict of the holding below in this case with the

dominant tenor of other state court decisions on the same

point of federal constitutional law makes it desirable that

this Court settle the point. See Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee,

1 Wheat. 304, 347-348, 380.

The importance of this issue should not be obscured

by its presentation in the context of a conviction on a minor

criminal charge, punished by a ten dollar fine. The im

portance of minor offenses such as this in our judicial sys

tem was well stated in a recently published discussion of dis

orderly conduct and related offenses by the American Law

Institute in its Model Penal Code, Tentative Draft No. 13,

P-2:

This article deals with a vast area of penal law

which has received little systematic consideration by

legislatures, judges, and scholars. The reason for this

is that the penalties involved are generally minor,

and defendants are usually from the lowest economic

and social levels. Appeals are infrequent and pres

sures for legislative reform are minimal. Yet, this is

a most important area of criminal administration, af

fecting the largest number of defendants, involving a

great portion of police activity, and powerfully in

fluencing the view of public justice held by millions

of people.

9 Cf. American Law Institute, Model Penal Code, Tentative Draft

No. 13, §§250.1(2), 250.12.

14

The importance attached to the administration of justice

in cases involving minor offenses is further illustrated, of

course, by this Court’s review of Thompson v. Louisville,

362 U. S. 199. And see Douglas, “ Vagrancy and Arrest on

Suspicion,” 70 Yale L. J. 1 (1960).

Review of this case would bring under the hand of this

Court a case involving the infringement of a basic liberty,

that of freedom of movement, by a means fundamentally

wanting in the definiteness and freedom from arbitrary

power that make up our concept of due process of law.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons it is submitted that this cause

presents substantial federal constitutional questions of

public importance which merit plenary consideration by

this Court for their resolution.

Respectfully submitted,

Martin A. Martin

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond, Virginia

T hurgood Marshall

J ack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellant

Norman C. A maker

Charles L. Black, Jr.

E lwood H. Chisolm

Of Counsel

APPENDIX

P r e s e n t :

Opinion Below

All the Justices.

Record No. 5232

R uth E. T insley

-v.-

City of R ichmond

F rom the Hustings Court of the City of R ichmond

W. Moscoe Huntley, Judge

Opinion by J ustice H arry L. Carrico

Richmond, Virginia, April 24th, 1961

Ruth E. Tinsley was arrested on a warrant which con

tained the charge that she did on the 23rd day of February,

1960, “ unlawfully refuse to move on when told to do so by

Police Officer D. L. Nuckols in violation of Section 24-17

of the City Code.” Richmond City Code, 1957, Section 24-

17. Upon her trial in the court below, without a jury, she

was found guilty and her punishment was fixed at a fine of

$10.00. She sought, and was granted, a writ of error to

the judgment of conviction.

The defendant has assigned a number of errors which

attack the constitutionality and validity of the ordinance

under which she was arrested, tried and convicted. She

also contends that the evidence presented against her was

insufficient to sustain her conviction.

16

The material facts in the case are not in dispute.

On February 23rd, 1960, Thalhimer’s Department Store,

located in a block bounded by Sixth, Seventh, Broad and

Grace Streets, in the City of Richmond, was being picketed

by large numbers of persons who were carrying placards,

and who were circling the store on the sidewalks adjacent

thereto. In addition to the pickets, large crowds were on

the sidewalks. Demonstrations of a similar nature had

taken place previously in the same area, and some students

taking part in the demonstrations had been arrested.

A number of police officers, some in uniform, and some

not, had been assigned to the area. They had been in

structed by their superiors to keep everyone moving on the

sidewalks, and in compliance with these orders the pickets,

onlookers, and even the police officers not in uniform, were

directed to keep moving. Two of the police officers, Lt. L.

H. Griffin and Patrolman D. L. Nuckols, testified that these

actions were taken to keep the sidewalk open for pedestrian

traffic and to avoid disorder.

Persons waiting for buses at a bus stop were required

to move to a position, in line, near the curb.

A newsboy, selling newspapers on a corner of the block,

was required by the police officers to move on, but was

later permitted to return when the newspaper company by

whom he was employed intervened with the police in his

behalf.

Defendant, on this date, was on her way to Thalhimer’s

to pay a bill she owed there, and then planned to wait out

side the store to meet a friend. As she neared the store,

someone gave her a handbill which contained an admonition

against dealing at Thalhimer’s, so she decided not to go

into the store to pay her bill, but instead to wait for her

friend outside the store building, at the corner of Sixth

and Broad Streets.

17

Defendant saw the pickets and the large crowds of peo

ple on the sidewalks.

She was standing against the window of the store when

Officer Nuckols, in full uniform, approached her and asked

her to move on. She asked him why she had to move. Again

the officer asked her to move. She then pointed out to him

some other people who were not moving and again asked

him why she had to move. The officer said he hadn’t yet

gotten to the other people and then ordered her to move.

She refused, and the officer arrested her on the charge

set forth in the warrant.

The ordinance in question, Section 24-17 of the Code of

the City of Richmond, is as follows:

“ Any person loitering or standing on the street, side

walk or curb, shall move on or separate when required to

do so by any member of the Police Bureau and shall cease

to occupy such position on the street, sidewalk or curb.”

Defendant contends that the ordinance is unconstitutional

in that:

1. It is an unlawful delegation of legislative power, be

cause it fails to prescribe standards to guide the conduct

of the members of the Police Bureau.

2. It is vague and ambiguous.

These two contentions will be dealt with together, since

the arguments advanced by defendant in support of her

first contention would, if valid, apply to her second con

tention, and vice versa.

We recognize the constitutional prohibition that or

dinarily, in a statute or ordinance, a legislative body can

not delegate to administrative officers an exercise of dis

cretionary power, without providing a uniform rule of

action to guide such officers. We have, however, also recog

nized a well established exception to this rule. This excep

18

tion applies in instances where it is difficult or impracti

cable to lay down a definite or comprehensive rule, or where

the discretion relates to the administration of a police

regulation and is essential to the public morals, health,

safety and welfare.

It is our opinion that in the enactment of the ordinance,

the city has validly exercised the powers given it under its

charter, and has not unlawfully delegated its legislative

power.

Section 2.04 of the charter grants to the City Council

the power to adopt ordinances “ for the preservation of the

safety, health, peace, good order, comfort, convenience,

morals and welfare of its inhabitants,” and for the “ pre

vention of conduct in the streets dangerous to the public”

(Acts of Assembly 1948, p. 183).

In the exercise of these powers the City Council adopted

Section 24-17 of the City Code of 1957. It should be noted

that the ordinance now in dispute was first adopted in

1909 and has been re-enacted in the various city codes since

that time, pursuant to previously existing charter au

thority.

The ordinance in question is of a regulatory nature and

is designed to preserve the safety, peace, good order and

convenience of the inhabitants of the City, and to prevent

conduct in the streets dangerous to the public.

In order to carry out the purposes for which such a

regulatory ordinance is adopted, the legislative body may

place in the hands of the officers responsible for its enforce

ment, such discretion as is reasonable and proper to pro

mote public peace and order. Moreover, it would be impos

sible, in such a case, to delineate in the ordinance itself,

each circumstance which would be sufficient to warrant

action by such officers. Under these conditions, the failure

to set out a specific standard of conduct in the ordinance

does not render the ordinance void.

19

This court has recognized this principle in the case of

Taylor v. Smith, 140 Ya. 217, 124 S. E. 259, where we said:

“ We are of the opinion that a city may, in the execution

of its police power, invest its administrative and executive

officers with a reasonable discretion in the performance

of duties devolved upon them to that end, whenever it is

necessary for the safety and welfare of the public. Such a

discretion is neither arbitrary nor capricious.” (140 Va.,

at pages 231, 232.)

The court also quoted, with approval, the following from

12 A. L. R. 1435:

“ It is also well settled that it is not always necessary

that the statutes and ordinances prescribe a specific rule

of action, but on the other hand, some situations require

the vesting of some discretion in public officials, as for in

stance, where it is difficult or impracticable to lay down a

definite, comprehensive rule, or the regulation relates to

the administration of a police regulation and is necessary

to protect the public morals, health, safety, and general

welfare.”

We have previously upheld the validity of an ordinance

similar to the one in question here, in the case of Benson v.

City of Norfolk, 163 Va. 1037, 177 S. E. 222.

In the Benson case the City of Norfolk had, in 1907, in

exercise of charter powers similar to those held by the City

of Richmond, enacted the following ordinance:

“ Sec. 483. Authority of police to require persons on

street to move on.

“ Any person or persons, vending or hawking goods,

wares or merchandise, or loitering or standing on any of

the streets or ways of the City, shall when required so

to do by any member of the police force, move on, or any

group of persons standing shall separate and move on, and

20

cease to occupy such position on the street or way, under

penalty of not less than three nor more than fifty dollars

for each offense, and in addition, in the discretion of the

Police Justice, may be confined in jail not exceeding thirty

days.”

Benson assailed the constitutionality of the Norfolk

ordinance on the grounds, among others not applicable

here, that it constituted an unlawful delegation of legis

lative power in that it failed to lay down rules for the

conduct of the police officers in enforcing the ordinance.

We said in the Benson case:

“ The general power to regulate the use of the streets,

and to do all things necessary or expedient for promoting

the general welfare and peace of its inhabitants, and to

make and enforce all ordinances would certainly seem to

warrant the enactment of the ordinance in question. (163

Va., at page 1039.)

# # # # *

“ It is, in our opinion, most salutary that the police offi

cers of a municipality should have reasonable authority

and discretion. Indeed, in exigencies, it is vital to the wel

fare of the community.

“ Courts should assume, initially, that they will exercise

their discretion and authority in a fair and reasonable

way.” (163 Va., at page 1040.)

We re-adopt these views and hold them to be controlling

in the case now before us.

Legislative enactments of a similar nature have come

under review in the courts of other jurisdictions. While

there is a division of authority on the question of the

validity of such regulations (See Am. Jur., Highways, Sec

tion 189, pp. 488, 489 and 65 ALB 2d, p. 1152) we adhere to

our holding in Benson v. City of Norfolk, supra, that they

are valid.

21

Typical of the cases approving such regulations is Peo

ple v. Galpern, 259 N. Y. 279, 181 N. E. 572, in which the

Court of Appeals of New York had under examination

section 722 of the Penal Law (Laws 1923, c. 642, as amended

by Laws 1924, c. 476) which provided that in cities of 500,-

000 inhabitants or more, it would constitute disorderly

conduct if a person “ congregates with others on a public

street and refuses to move on when ordered by the police.”

Galpern was standing on a sidewalk with five or six

friends, in an orderly and inoffensive way. There were no

other circumstances surrounding the incident. A police

officer ordered the members of the group to move on, and

Galpern refused to do so, and was arrested and charged

with disorderly conduct. His conviction was upheld, and the

Court said in its opinion:

“A refusal to obey such an order can be justified only

where the circumstances show conclusively that the police

officer’s direction was purely arbitrary and was not calcu

lated in any way to promote the public order. That is not

the case here.” (181 N. E., at page 574.)

See also State v. Sugarman, 126 Minn. 477, 148 N. W.

466; City of Tacoma v. Roe, 190 Wash. 44, 68 P. 2nd 1028.

In the Galpern case, as has been noted, the regulation

required that a person had to congregate with others be

fore an order to move on could be given. In the Sugarman

case, three or more persons had to be assembled before such

an order would be warranted. But in the Roe case, as with

the ordinance now before us, a person standing alone

on the street or sidewalk could be ordered to move on. A l

though these regulations differ in these respects, it will be

seen from a reading of all of them that a common purpose

is sought to be achieved—a free and unobstructed passage

of the street or sidewalk. In each regulation the offense

consists of standing on the street or sidewalk, and the

22

person’s obligation to move on is conditioned upon a warn

ing by a police officer to so move. The regulation has been

upheld even though only one person of a group refused to

move on and was arrested because he did not comply. The

fact that such a regulation may be operative when a per

son is standing alone does not render the regulation void.

The important consideration is whether the regulation is

designed to afford free and unobstructed passage of the

street or sidewalk for the preservation of public order, and

the controlling factor in each arrest is whether or not the

officer authorized to enforce the regulation has acted arbi

trarily.

The test as to whether there has been a reasonable and

proper exercise of the authority given the enforcing offi

cers by the statute or ordinance is a matter for judicial

determination, and depends upon the circumstances sur

rounding each arrest. If, upon judicial review, it appears

that the police officer has acted arbitrarily, it is the duty of

the courts to acquit the alleged offender. On the other hand,

if the officer has acted reasonably to promote the public

welfare and peace, his actions must be upheld.

In this case, where, at the time of the arrest, picketing

of a highly controversial nature was taking place, crowds

of people were on the sidewalks, some friendly and some

hostile to the pickets, and tensions ran high, it was impera

tive that order be maintained, and that there be a “pre

vention of conduct in the streets dangerous to the public.”

(Richmond City Charter §2.04.) Under these circum

stances, when the police officer invoked the ordinance in

question against the defendant, we cannot say that he acted

arbitrarily. The facts fully justify the action taken by him.

Defendant complains that the ordinance is so vague and

ambiguous as to render it unconstitutional and void.

The test of statutory definiteness has been laid down in

the case of Standard Oil Co. v. Commonwealth, 131 Va. 830,

23

833,109 S. E. 316, that “ an ordinance of a regulatory nature

must be clear, certain and definite, so that the average

man may, with due care, after reading the same, understand

whether he will incur a penalty for his action or not, and

if not of this character it is void for uncertainty.”

We think the ordinance in question amply meets this

test, and is not unconstitutional and void for the reason as

signed.

The defendant, in her argument that the ordinance is

vague and ambiguous seems also to assert that the facts

surrounding her arrest show that she was denied due

process of law and the equal protection of the laws guar

anteed to her under the Constitution of the United States

and Section 11 of the Constitution of Virginia. She cites,

as the basis for this assertion, the fact that the newspaper

boy was permitted to return to the corner and was not

again required to move on, while she was arrested. She

states that this proves that the police officer discriminated

against her in arresting her. Although this objection was

not stated, assigned or presented as required by Rules of

Court 1:8, 5:1 §4 and 5:12 §1 (d), the answer to the

objection is simply that nothing appears from the ordi

nance itself or from the evidence presented in the trial

court to show any discriminatory action in this case.

Finally, defendant contends that the evidence was not

sufficient to support her conviction.

When the sufficiency of the evidence is challenged after

conviction it is our duty to view it in the light most

favorable to the prosecution, granting all reasonable in

ferences fairly deductible therefrom. The judgment should

be affirmed unless “ it appears from the evidence that such

judgment is plainly wrong or without evidence to support

it.” § 8-491, Code, 1950; Crisman v. Commonwealth, 197 Va.

17, 87 S. E. 2nd, 796; Toler v. Commonwealth, 188 Va.

774, 51 S. E. 2nd 210.

24

We think the evidence is sufficient to support the judg

ment of the trial court, and that the judgment is plainly

right. Defendant knew that a demonstration was taking

place in the block where she was standing; she had notice

of it from the handbill which had been given her, and she

respected its admonition to the extent that she deviated

from her purpose to go into the store to pay her bill. She

saw the pickets and their placards; she saw the large

crowds; she knew that students, who had taken part in the

demonstrations, had been arrested. She deliberately placed

herself in an emotion-packed situation, where at any mo

ment trouble could have erupted, causing danger to the

defendant and to the others on the sidewalk. She was told

three times by a uniformed officer to move on; when she

refused her offense was complete.

The police officer was under no obligation to stand and

argue with the defendant. To have done so would have de

feated the very purpose of the ordinance and the reason

for keeping everyone moving—the maintenance of order.

Under the circumstances, the officer was called upon to act

with dispatch and firmness. Since he did not act arbi

trarily, it is no defense to say that he should have acted

more judiciously. As was said in the Galpern case, supra'.

“ The courts cannot weigh opposing considerations as to

the wisdom of the police officer’s directions when a police

officer is called upon to decide whether the time has come

in which some directions are called for.” (181 N. E., at

page 574.)

The defendant has been convicted under a valid ordinance

by competent and sufficient evidence. The judgment of

conviction is therefore Affirmed.

25

Judgment

VIRGINIA:

In the Supreme Court of Appeals held at the Supreme

Court of Appeals Building in the City of Richmond on

Monday the 24th day of April, 1961.

Record No. 5232

R uth E. T insley,

Plaintiff in error,

— against—

City of R ichmond,

Defendant in error.

Upon a writ of error and supersedeas to a judg

ment rendered by the Hustings Court of the City

of Richmond on the 11th day of April, 1960

This day came again the parties, by counsel, and the

court having maturely considered the transcript of the

record of the judgment aforesaid and arguments of coun

sel, is of opinion, for reasons stated in writing and filed

with the record, that there is no error in the judgment com

plained of. It is therefore adjudged and ordered that the

said judgment be affirmed, and that the plaintiff in error

pay to the defendant in error thirty dollars damages, and

also its costs by it expended about its defense herein.

Which is ordered to be forthwith certified to the said

hustings court.

A Copy,

Teste:

Clerk.

38