Brief for Appellee

Public Court Documents

February 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Brief for Appellee, 1985. 3c34bd7d-ed92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f31f115e-e17f-4947-9107-9da8ea9bcd2a/brief-for-appellee. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

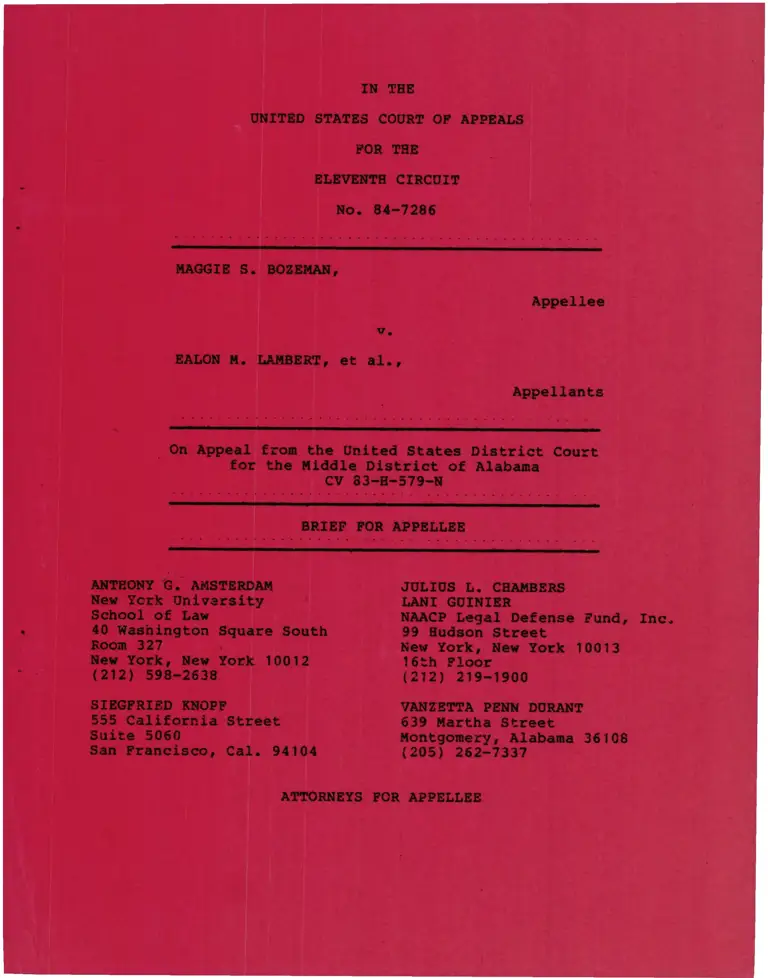

IN TEE

UNITED STATES COT'RT OF APPEAIJS

FOR THE

ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 84-7286

I,TAGGIE S. BOZEIIA}I,

Appellee

V.

EALON U. [.AUBERTT €t dl.2

Appellants

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the lriddle Dlstrict of Alabama

cv 83-E-579-N

BRIEE' FOR APPELLEE

A}ITEONY G.- AI.{STERDNi JULIUS L. CHAIIBERS

New York University I"ANI GUINIER

School of Law NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Inc.

r 40 Washington Square South 99 Budson St,reet

Room 327 New York, New York 10013

New York, New York 10012 l6th Floor

(212) s98-2638 12121 219-1900

SIEGFRIED KNOPF VAIIZETTA PENN DT'F"AIIT

555 California Street 639 t{artha Street

Suite 5060 Montgom€Ey, Alabama 36108

San Francisco, CaI. 941 04 ( 205') 262-7337

ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLEE

Thig appeal ls ent,lt,led co preference as an appeal fron a

grant of habeae corpus under 28 U.S.C. 52254.

tt

srAEEttBm REGARDING ORAr/ ARGIrllEtlr

Appellee reepectf ully request,s oral 'argument. The legal

lssues are cornplex and the consequences for appellee are slgnlfi-

cant.

tlt

TABLE OF CONTENTS

-

STATET{ENT REGARDING PREFERENCE ........................

STAfEIIIENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUIrIENT o.............. o.....

TABLE OF CONTENTS ........o....................r.......

TABTE oF cAsEs ......o......... o. o... o.................

SIATEIIIENT OF TIIE ISSUES ................... o...........

STATEI.{ENT OF THE CASE ....o............................

I. PROCEEDINGS BELOW o......o..o.o..""'o..""

II. STATEIT{ENT oF THE FACTS ....o......o..........

III. STATEIT,TENT OF THE STANDARD OF REVIEW

SUllltlARY OF THE ARGUI,IENT . o o........ o... o...............

STATEMENT oF JURISDICTION ............................o

ARGUITIENT . . . . . . . . . o . . . . . . . . . . . o . . . . . . o . . . o . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I. THE DISTRICT COURT VIEWED THE EVIDENCE

IN THE LIGIIT MOST FAVORABLE TO THE STATE

AND PROPERLY DETERII{INED IT WAS INSUFFI-

CIENT AS A !4ATTER OF FEDERAL CONSTITU-

TIONAL LAW ..........o........."'o"o"t""

A. The District Court Properly Applied

The Relevant Law To Conclude The

Evidence Was Insufficient, . .. ...........

B. In Enforcing Jackson v. Virgini?,

The District Court Was Not Requireal

To AccePt State Findings That The

Evidence Was Sufficient ............ ... o

C. The District Court's View Of The

Evidence was Not, Inconsistent with

Factual Findings Of The Alabama

Court of Criminal Appeals ....... -... . - -

II. THE INDICTIT,IENT AGAINST It{S. BOZEMAN WAS

FATALTY DEFECTIVE IN THAT IT FAILED TO

INFORM I{ER OF THE NATURE AND CAUSE OF

THE ACCUSATION ............"' o " " " "" ""

Page

ii

111

iv

vi

xi

1

'l

3

9

l0

12

12

12

13

20

22

1V

27

PaE

A.

B.

The Indictment was Constitutionally

Defective In That It, Failed To Pro-

vide Fair Notice Of A1I Of The

Charges On Which The Jury Was Per-

mitted To Return A verdict of Guilt

The Indictment Was Fatally Defec-

tive In That It Failed To Include

Constitutionally Suff icient A1Ie-

gations Concerning The Charges Of

Fraud

(1)

o a a a a o a o a a a a a a a a aa a a a a

The factual allegations in

each count were constitu-

tionally insufficient to Pro-

vide notice of the nature and

cause of the allegedly fraudu-

lent conduct ......................

28

39

41

45

47

49

(2) Counts I and II were consti-

tutionally insufficient for

failure to al1ege the crucial

mental element of the offense

of fraudulent voting under

517-23-1 . .. o o.. ........ ......... ..

TABLE OF CASES

Case

Andrews v. State , 344 So.2d 533 Crim. APp- ) ,

cert. denied, 344 So.2d 538 (Ala. 1977) ..... o.. o o o

Bachellar v. Maryland, 3g7 U.S. 564 (1970) .o........

Barbee v. State, 417 So.2d 611 (Ala. Crim.

App. 1982) ........o....... o.. o.... " 'o " o t o t" "

Boykin v. Alabama, 395 U.S. 238 (1969) ..-oo.o......

Bozeman v. State, 401 So.2d 169i 454 U.S.

1058 ( 1981 ) . . . . o . . .. .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . o.. o . . . . .

Page

... 2r5r14

23,24,25,26

18 r27

18

35

35

28 t34

39

18r19

35

34

18

14

34

35

35

40

35

39

Brewer v. williams, 430 U.S. 387 (1977) -.......o......

BfOWn V. A1len, 344 U.S. 443 ( 1953) ...................

Brown vo State, 24 So.2d 450 (A1a. ApP. 1946)

Carter v. State, 382 So.2d 610 (A1a. Crim-

App. 1980), cert. denied, 382 So.2d

614 ( 1980 ) . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . o . .. . . . .. .. . . . .. . . . . .

Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U.S. 196, 201 (1948) ............

County Court of Ulster County v. Al1en, 442

u.s. 140 ( 1979) . .. ......... ....... . ... .... o o.. . ....

Cuy1er v. Sullivan, 446 U.S. 335 (1980) ..-............

Davidson v. State, 351 So.2d 683 (Ala. Crim.

APP. 1977 ) ....o o...................... " " " " "" '

DeJonge v. oregon, 299 u.S. 353 (1937) .o...o..--..o...

Dickerson v. State of A1abama, 667 F.2d 1354

(11th Cir. 1982), cert. deniedr 459 U.S.

878 ( 1982 ) .... o.. .. .... ..... ........ .. .... .. . o.. ...

Duncan v. Stynchcombe, 704 F.2d 1213, ('l 1th

Cif . 1983) .................. o... o.............. o...

Dunn v. United States, 442 U.S. 100 (1979) ............

Edwards v. State, 379 So.2d 338 (Ala. Crim.

App. 1979 ) ..... o........... o...................... r

-vl.

Case

Fendley v. State, 272 So.2d 500 (Ala. Crim.

App. 1973 ) .............. o.......... o. o.............

Fitzgerald v. State, 303 So.2d 162 (A1a. Crim.

App. 1974 ) ............. o........ .. .................

Goodloe v. Parratt, 605 F.2d 1041 (8th Cir.

1969 ) .. ....... .... .. ... ... " ' ' o " ' " ' ' ' " " " ' t ' " '

Goodwin v. Balkom , 684 F.2d 794 ( 1 lt'h Cir.

1982) , cert. denied, 1 03 S.Ct. 1798 (1982) . ..... ...

Gray v. Rains, 662 F.2d 589 (1Oth Cir. 1981) .r........

Page

35

35

36

35

19

34

21

Passim

36

21

35

38

34

34 r36

41 ,46

28

18

38

Gunsby v. Wainwright, 595 F.2d 654 (5th Cir.

1979)t cert. denied, 444 U.S. 946 (1979) 18

Harmon v. State, 249 So.2d 369 (AIa. Crim.

App.), cert. denied, 249 So.2d 370 (Ala-

197 1) . . . . . . . . . . . . o . . . . . . . . . . t . ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' '

Holloway v. McElroy , 632 E.2d 605 ( 5th Cir.

1980), cert. denied, 451 U.S. 1028 ( 1981 ) ..........

In fe GaUlt , 387 U.S. 1 ( 1 967) . . ..... ..... o........ ...

In re winshiP, 397 U.S. 358 ( 1970) ... -................

Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307 (1979 ) ... o o. -.... o..

Keck v. United States, 172 U.S' 434 (1899) ...-.-.o..-.

La Vallee v. Delle Rose, 410 U.S. 690 (1973) .......-.o

Maggio v. Fulford,

-

U.S.

-,

76 L-Ed.2d

794 ( 1983 ) . .... . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . o. . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Nelson v. State, 278 So.2d 734 (AIa. Crim-

App. 1973 ) ............... o........ o................

Plunkett v. Estel1e, 709 F.2d 1004 (5th Cir.

1983), cert. denied, 104 S.Ct. 1000......-....o....

Presnell v. Georgia, 439 U.S. 14 ( 1978) .. - -...........

Russell v. Unit,ed States, 369 U.S. 749 (1962) .........

Smith v. otGrady, 311 u.S. 329 (1941) ...-........-...-

17

-v1l-

Case

Spray-Bilt v. Interso1l-Rand World

?.2d 99 (5t.h Cir. 1965) .......

Street v. New York, 394 U.S. 576 (

Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S.

sumner v. lrlata, 449 U.S. 539 (1981

38,39 r 40

) ......oo.....o....t 10r12r17

20 ,21 ,22 r26

38

38, 39, 40

18 ,22

42

35r36

41 t42

43

42

43

46 ,47

34 r45

41

46

Trade, 350

Page

't9

401969)

3s9 ( 1931 )

aaaaaa

Tarpley v. Estelle, 703 F.2d 157 (5th Cir.

1983), Ceft. denied, 104 S.Ct. 508 ....... o...... o..

TerminiellO V. ChiCagO, 337 U.S. 1 (1949) .............

TOWnSend V. Sain, 372 U.S. 293 (1963) ...oo.........o..

United St,ates v. Berlin, 472 F.2d 1003 (2nd

Cir. 1973) ..........o...."o""""o""t"""'o'

united States v. Carll, 105 U.S. 61 1 ( 1882) ..... " " "

United States v. C1ark, 546 F.2d 1130 (sth

Cir. 1977) ...t........""""t"""ooo"'o"""'

united States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542

( 1 875 ) . . . . . . . o . . . ' " " " ' " " " t " o " ' ' o ' " " " " "

United States V. Curtis, 505 F-2d 985 (1Oth

Cir. 1974) .............."""""""""'o"o"o'

Uniced States v. Diecidue, 603 F.2d 535 (5th

Cir. 1979) ..............'. "' o" " " " " " o " t o' o "

United States v. Dorfman, 532 F. SuPp. 1118

(N.D. I1l. 1981 ) ............................. o.....

United St,ates v. Dreyfus, 528 F.2d 1064 (5t'h

Cir. 1976) ...............' o"' o " " o "' o " " .. " "'

United St,ates v. Haas, 583 F. 2d 216 , reh.

denied, 588 F.2d 829 (5th Cir. 1978),

Ceft. denied, 440 U.S. 981 (1979 ) ..... o............

United States v. Hessr l24 U.S.483 (1888) ......"""

United States v. Huff, 512 F.2d 66 (5th

Cir. 1975) ..............'""""""'"""""'''

46

46

- vlll.

Case

United St.ates v. Nance, 144 U.S. APp. D.C.

477, 533 F.2d 699 (1976) ..........""""o""""

United States v. Outler, 659 F.2d 1306 (5t,h

Cir. Unit B 1981), cert. denied, 445 u.S.

950 ( 1982) . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . .. . .. .. . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . o ..

United St.ates v. Ramos, 666 F.2d 469 (11th

Cif. 1982) ............................ o............

United States v. Strauss, 283 F.2d 1955

( 5tn Cif . 1960 ) .. . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . o . . . . . o . . . . . . . o . . .

von Atkinson v. smith, 575 F.2d 819 (10th

Cif . 1978 ) .......... o..............................

Wainwright v. Sykes, 433 U.S. 72 (1977) o-.oo..........

Wainwright v. Wittr 53 U.S.L.W.4108 (Jan.

21 , 1985) ....................... " " " " " o " .. o .. '

Watson v. Jingo, 558 F.2d 330 (6th Cir. 1977 ) .... o....

Paqe

43

34 ,41

42 ,45

34 t41 ,45

34 r45

2r40t42

2

12

passim

12

Wilder v. St,ate , 401 So.2d 151 (Ala. Crim-

App.), cert. denied, 401 So.2d 167 (Ala.

1981 ), cert. denied, 454 U.S. 1057 ( 1982)

38

39

18

38

35

14

14

40Williams v. North Carolina, 317 U.S. 287 (1942) -......

Williams v. Stater 333 So.2d 610 (Ala. Crim.

App. ), af f rd, 333 So.2d 513 (A1a- 1976 ) ............

i{i]SOn V. St,ate, 52 AIa. 299 ( 1875) . o.................

Unlled States Constitution and Statutes

SiXth Amendment ...o....................o..............

FOuftgenth Amgndmgnt ................o..........o......

28 U.S.C. 52241 (C) ( 3) ... ............. o... .. . o...... ...

28 u.s.C. 52254 (d ) . o . . . . . o . . . . . ... . . .. . . . . . . .. . . . .. . ..

Fed. R. CiV. P. 54(b) ......... o.. r....................

1X

Alabara Statutcs

Ala. Acte 1980r No.

Ala. Code S13-5-lt5

AIa. Code S17-10-3

AIa. Code St7-10-6

Ala. Code s 1 7-1 0-7

AIa. Code Sl7-23-1

othcr lutborltlrs

75 'Am. Jr.2d Trlal

76 Am. Jr.2d Tria1

80-732r P. 1478, SS3, 4 ...........

( 1975 ) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ' t .

(1975) .............................

( 1975 ) . . . . . . . t . . . . . . . . . . . . . . o . . . . . .

( 1975 ) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

( 1975 ) . . . . o . . o I o . . . . . o . . . . . . . . . o ' ' '

5885 ...... r... ........... ....... a o.

511l 1 . ... ........... ...... ...... ...

Paqe

31

11r29

31 ,32

11 ,29 r30

11r29

30r31

11 ,29

30 ,31

pasgin

{0

{0

-I

9ImEUEI|T Op rBE rSsIrBS

f.

lIhether the Distrlct Court correctly aPPIied

the appllcable law to find under {ggfson v!

vlrstiia, 443 U.S. 307 (1979) thatT-EFEt-Tt

EEfTffif nost f avorable to t,he prosecutlon,

the evidence was insufftclent to suPport a

convictlon?

II.

Whether an indictnrent whlch fails to inform a

defendant of the nature and cause of the

accuEatl.on agalnst her violaEes the Slxth

Amenduent?

-rt

UNISED

FOR

IN TEE

STATES COSRT OF APPEALS

TEE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 84-7286

UAGGIE S. BOZBIIAII,

V.

EALON !1. tAl,tBERTr €E E1.1

Appellee

Appellants

On Appeal fron

for the

the United States Distrlct Court

Irliddle Dlstrict'of Alabama

cv 83-E-579-N

STATEI,iENT OF TBE CASE

I. PROCEEDINGS BELOIY

Indicted on three counts of voting fraud (Alabama Code

S17-23-1 (1975)), appellee trlaggie S. Bozeman was tried by jury in

the Circuit Court of Pickens County, Alabama. IIer motion for a

directed verdict at the close of the St,aters case was denied, and

the jury returned a single verdict of "guilty as charged" without

specifying the count or counts on which its verdict rested. t'ts.

Bozeman was sentenced Lo four years in prison. She appealed her

conviction, challenging inter alia t.he sufficiency of the

evidence and the const,itutionality of t,he indictment. The

Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed, holding that the

verdict was 'not patently against the weight, of the evidence" and

that the indictment was adequate. Bozeman v. State, 401 So.2d

L67 , 171 ( 1981) . Af t,er denial of a mot,ion f or rehearing, the

issues $rere present,ed to the Alabama Supreme Court and the

Supreme Court of the United SEates, but, both denied certiorari.

Bozeman v. State, 401 So.2d LTLi 454 U.S. 1058 (1981).

The insEant federal habeas corpus proceeding was initiated

by the filing of a petit,ion for a Writ of llabeas Corpus (herein-

after nPetition") on June 8, 1983. On January 20, 1984, Ils.

Bozeman filed a Motion for Summary Judgnent, asserting that the

evidence offered at t,rial was insufficient to prove guilt beyond

areasonab1edoubtundert'heDueProcessstandardSof@

Virginia, 443 U.S. 307 (1979), ind that the indictment was

insuf f icient, t,o inf orm her of the naEure and cause of the

accusat,ion against her as required by the Sixth and Fourteenth

Amendments. The district court grant,ed the motion on April 13,

1984 r and ordered that l'ls. Bozeman's conviction be vacat,ed. The

court held that, taken in the light most favorable to the

prosecution, the evidence at trial was insuff icient' for any

rational trier of fact to find each element, of the crime beyond a

reasonable doubt. The court also held that Ms. Bozemanrs

constitut,ional rights were violated because the indictment failed

to provide any notice of a number of criminal statutes and

theories of liability submitted to the jury.

This appeal was taken on April 27, 1984. On llay l, 1984, the

district court granted apPellant,s a stay of judgment pending

appeal.

II. STATEI,IENT OF TEE FACTS

trtagg ie s. Boz eman, a black school teacherr NAACP Branch

presidentr and long-time civil rights activist, was convicted by

an all-white jury of violating Alabama Code 517-23-1 because of

her alleged participation in an effort to assist elderly and

illiteraEe black voters to cast absentee ballots in the Demo-

cratic Primary Run-Off of September 26, I978 (hereinafter

'run-off "). The three count indictmenE, charged t,hat she:

COTINT ONE

,atid vote more than once t oE did deposie more

than one ballot for the same office as her

voter oE did vote iIlegally or Eraudulently,

in the Democrat,ic Primary Run-off Election of

September 26, L978,

COUNT TWO

did vote more than once as an absentee voter,

or did deposit more than one absentee ballot

for t,he same of f ice or off ices as her voter oE

did cast i1IegaI or fraudulent absentee

ballots, in t.he Democratic Primary Run-of f

Election of SePtember 26, L978,

3

COUNT THREE

did cast illegaI or fraudulent absentee

ballots in the Democrat.ic Primary Run-off

Election of Sept,ember 25, 1978, in that she

did deposit with the Pickens County Circuit

C1erk, absentee ballots which were fraudulent

and which she knew to be fraudulent, against'

the peace and dignity of the State of

Alabama.

1Tr. 211'

At, trial the prosecution introduced thirty-nine absentee

ballots, Tr. 41r drd claimed that Ms. Bozeman had participated in

the voting of these ballots in violation of S17-23-1. ft was

undisputed t,hat each ballot had been cast in the run-off , and

purported t,o be the vote of a different black elderly resident of

Pickens County.

No evidence was presented that llls. Bozeman had cast or

participated in t,he casting, f ilIing out or Procurement of any of

the thirty-nine absentee baIlots. fndeed there is nothing in the

record to lndicate who cast those balIots. Tr. 2I. The tran-

scripE is also silent, as to whether }ls. Bozeman voted even once

in the run-off.

The prosecution hinged its case on evidence that lls. Bozeman

played a minor role in the not,arizing of the 39 absentee balIots,

and contended that her role in the notarizing $ras sufficient to

The following abbreviations

Court trial transcriPt; "IIrg.

Judge Truman llobbs i 'R. " f or

will be used: "Tr.' for Circuit

Tr. " f or llearing before District

Record on Appeal.

4

warrant her conviction under 517-23-1, because the voters did not

appear before the notary. Tr. 195-197; g!. Tr. 90, 105-106.

District Attorney Johnston, in his resPonse to I'tS. Bozeman rs

motion for a directed verdict at the close of the Staters case,

claimed that the thirty-nine absentee ballot,s "\.rere not properly

notarized, and in that sense, they were fraudulent.' Tr. 196. He

stated that "the act of the Defendant in arranging the conference

[at which t,he ballots were notarized] and in participating in the

presentation of the ballots t,o lthe notary] to be notarized was

fraud.' Tr. 195.

The prosecution called only nine of the thirty-nine absentee

voters t.o testify. Each of these witnesses rrras elderly, of Poor

memory, illiterate or semi-literate, and lacking in even a

rudiment,ary knowledge of vot.ing or notarizing procedures. The

Alabama Court of Criminals Appeals found t,heir testimony confu-

sing in several instances. 401 S.2d at 170. The court below

found that mosc of their testimony did not concern Ms. Bozeman,

R. L66, and when it did it, was "simply incomprehensible." R. 168.

Nevertheless, insofar as any synthesis could be made of the

individual testimony, t,he court below construed iC in t,he light

most favorable to Ehe prosecution.

It is uncontested that only two of the nine voters, l'tS.

Soph ia Spann and I{S . Lou Sommervi 1le, gave evidence of any

cont,act with llls. Bozeman regarding absentee vot,ing.2 (Prosecu-

ltlls. Lucille Harris (Tr. 189 ) and Ms. Maudine Latham (Tr. 91-93 )

5

tion's closing argument, Record on Appeal, Volume 3 of 3, at 26-)

The court below found that no connection was drawn by even these

voters between [,1s. Bozeman and any of the absentee ballots cast

in t.he run-of f .3

The court found that 'not one of the elderly voters t,esti-

fied that Bozeman ever came to see him or her about voting in

connection with the runoff," R. 165, and that the only evidence

against tls. Bozeman was the testimony of Paul Rollins, a notary

from Tuscaloosa. Mr. Rollinst testimony was that, Ms. Bozeman was

one of a group of women who brought. ballots to be notarized, that

she may have called to arrange the meeting, and that she was

present when the notary notarized the ballots after the women as

a group assured him the signatures were genuine. Id.4' The

testified to never having seen the absentee ballot introduced

into evidence as their vote. !1s. Anne Billups (Tr. 97-98), t'ls.

I'lattie Gipson (Tr. 1I0 ) , Fls. Janie Richey (Tr. L271, and [ls.

Fronnie Rice (Tr. I36-137, L48, 15I) each remembered voting by

absentee ballot in the run-off. Mr. NaE Dancy (Tr. 113) did not

provide any coherent testimony whatever on the way in which he

voted in the run-off.

D{s. Spann testified that, she did not sign an aPPlication or a

ballot, and was told thaE an absentee balIot was cast in her name

when she went to her usual polling place. The court below found

that "She stated that Bozeman came at, some time prior to the

runrcff and asked if Spann wanted to vote absentee and Spann said

she did not. Julia Wilder witnessed Spannrs application.rr R.

169. Fts. Sommerville stated in an out-of-court "deposition" that

t{s. Bozeman'may have filIed in her ballot and that she never

signed the balIot." R. 169. The deposition was not admitted

into evidence, id., and, at trial the witness vehemently denied

its contents. E

ttr. Rollins testified that he notarized the thirty-nine ballots

in his office in Tuscaloosa without the voters being present. Tr.

56-64. He testified that Ms. Bozeman, with three or four other

6

district court found that all other circumstantial indicat.ions of

R. L72. Theguilt were stricken or were ruled inadmissible.

circumstant,ial evidence to which the court referred was the

testimony of the court clerk and the t,estimony of Mrs. Lou

Sommerville. The court found with regard to the clerk:

Janice Tilley, the court clerk, testified that

Bozeman came in several times to pick up

applications for absentee ballots. This was

entirely legal. She also stated Lhat one

t ime , j us t pr ior to t,he runof f , Bozeman and

Wilder came together in a car, although only

Wilder came int,o t,he office. Upon objection by

defense counsel, however, the trial judge

struck most, of this testimony, including all

references t,o Wilder. The only testimony that,

was not stricken was E,hat, Bozeman was in a car

alone and did not come inside.

R. 166

The court f ound that [Irs. Sommerville's t,estimony about, her

balIot was incomprehensible, in part because the prosecution

attempted to introduce evidence connecting t'ls. Bozeman with Mrs.

Sommerville's absentee ballot by reading to the jury not,es pur-

porting to be t,he transcript of an out-of-court "deposition" of

Mrs. Sommerville condueted without an at,torney present for either

yromen, $ras present in the room when he was notarizing the

bal1ots. Tr. 57 . But [t{r. Rollins denied that tils. Bozeman

personally requested him to not,arize t,he ballots. Tr. 59, 60,

62, 64. lle also stated that he had no memory of [1s. Bozeman

representing to him that the signatures on t,he ballots were

genuine. Tr. 73-74. All the prosecution could elicit from l,lr.

Rollins was that Ms. Bozeman and the other women present at, the

notarizing were "together." Tr. 50-61, 62, 64, 7L.

7

the witness or lltS. Bozeman.5 On the stand, l,1rS. SOmmerville

test,ified that t{s. Bozeman had never signed anything for her, and

denied ever giving a deposition. R. 169. The court determined

t,hat, rLou Sommerville's deposition was never placed in evidence

and would not have been admissible as substantive evidence

anyway.' R. L72.

The district court concluded:

Although there was convincing evidence to show

that Ehe ballots vrere iIlegally cast, there

was no evidence of intent on Bozemanrs Part

and no evidence thaE she forged or helped to

forge the ballots. There is no evidence t,hat

she t,ook applications to any of the votersr oE

that she helped any of the voters fill out an

application or ballotr oE t.hat she returned an

application or ballot for any of the voters,

and no ballot was mailed t.o her residence.

Thus, there was no evidence that Bozeman

realized when she accomPanied Wilder and

others to the office of Rollins thaE the

ballots she helped to get notarized were

fraudulent.

R. 172.

Testifying in person, [t{rs. Somerville vehemently challenged the

veracity of t.he notes rePresented by the Prosecut,or to be a

transcript oe her out-of-court statements, and steadfastly denied

that Ms. Bozeman was involved in any way with lllrs. Sommerville's

voting activities. Tr. 163, 159, L73t L74t 175. According t,o the

Out-of-Court statements, l,ts. Bozeman aided Mrs. Sommerville tO

fill out an application for an absentee ba1lot in order that I'trs.

Sommerville could vote by absentee ballot in the run-off. TE.

161, 159. Taken in the light most favorable to the prosecution,

even the out-of-court statements -- which were neither admitted

nor admissible in evidence showed only that [1s. Bozeman aided

Mrs. Sonunerville to engage in lawful vot,ing activities wich the

latterts knowledge and consent.

8

Af ter f irst det,ermining t,hat, Nls. Bozeman had exhausted all

her st,ate remedies, t,he dist,rict court applied the JagFson v.

Virg inia st.andard and held t,he evidence insuf f icient for a

rational trier of face to find guilc beyond a reasonable doubt.

The court also ruled Ehat t,he indictment was constitutionally

defective.

III. STATEI,TENT OF TTIE STAT{DARD OF RBVIEW

Appellants I expl icit, cont,entions on appeal are that the

district court failed to observe rules prescribed by statute and

caselaw for analyzing constit,utional issues presented in federal

habeas corpus proceedings. The standard of review of these

asserLed errors is whether the district court disregarded

applicable legal principles in its analysis of the constitutional

merits of the case. Appellants do not explicitly contend that if

the district court analyzed lls. Bozeman's .Iacfso" v. Virginia

claim according Eo t,he applicable legaI principles, it erred in

finding const,itutionally insufficient evidence t,o sustain her

conviction. If this contention is nevertheless implied in

appellantsr argument,s, the standard of review is whether the

dist,rict courtrs conclusion is fairly supported by the record as

a whole.

9

SUTITUARY OF ARGUI,IENT

I. Appellants t submiss ion that t,he district court erred

under Sumner v. [lat.a and 28 U.S.C. 52254 (d ) in f ailing to def er

to state-court fact. findings (or to explain it,s refusal to do so)

when adjudicating trls. Bozeman's 93g!gg claim is utterly baseless

on this record and in law. In the first place, the district

court made no findings of historical fact that. differ materially

from those of Ehe stat,e courts, it disagreed only with the state

courts I ult,imate conclusions regarding the constitutional

suf f iciency of t,he evidence. In t,he second place, state-court

fact findings that lack the minimal evidentiary support demanded

by the constit,utional rule of Jackson v. Virginlq self-evidently

falI outside t,he scope of the "determination[s] ... on the merits

of a factual issue" which are 'presumed to be correct" under 28

U.S.C. S2254(d), because, by def inition, they are rnot fairly

supported by the recordr' 28 U.S.C. 52254(d) (8). Thus, the

district courtrs explicit conclusion that there was no constitu-

tionally sufficient evidence to sustain Ms. Bozemanrs conviction

fully satisfied Sumner and 52254(d) at the same time that it

established a Jackson violation.

The district court properly conducted an independent review

of t,he state-court record as required by Jackson. Its det,ermina-

tion that the evidence, taken in the light most favorable to the

prosecution, vras insuff icient to sustain a conviction is amply

10

supported by the record as a whole, and is not based on any

Eactual findings inconsistent with the Alabama Court of Criminal

Appeals' opinion. Appellants I effort to creat,e such inconsisten-

cies by pointing to the trivially different phraseologies used by

the district court and by the Court of Criminal Appeals in

summarizing the trial transcript will not withstand analysis.

II. The dist,rict court found that the Erial judge instruct-

ed the jury on four statutes, Ala. Code 517-10-3 (1975) [miscited

by the trial judge as 517-23-31, Tr. 202i AIa. Code 517-10-6

irszsl [miscired by rhe t,rial judge as s17-10-7), Tr. 202-203i

AIa. Code S17-I0-7 (1975), Tr. 203-204i and Ala. Code 513-5-115

(1975), Tr. 2O4i and on t,he offense of conspiracy, Tr. 206. The

jury was further instructed that proof that Ms. Bozeman had

COmmited any aCt 'not authorized by ... or ... contrary tO' any

Iaw would constitute an "i1legal" act warranting her conviction

under 517-23-1. Tr. 201. The effect of t,hese inst,ructions tras to

make a violation of each of the other statutes a seParate ground

for liability under S17-23-L. Yet the indiccment contained no

allegations that Ms. Bozeman had violated those other statutes or

had engaged in acts which would constitute violations of t.hem.

For these reasons the district court correctly held that the

indictment failed t,o provide notice of the offenses for which t'ls.

Bozemanrs conviction was actually sought and that her conviction

rrras accordingly obtained in violation of due process.

l1

I.

STATET.{ENT OB JURISDICTION

The district court, had jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C.

52241(c)(3). The dist,rict courtrs final judgnent was certified

pursuant, E,o Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(b).

ARGqUENT

TEE DISTRICT COT'RT VIEWED THE EVIDENCE IN TEE LIGET UOST

FAVORABLE TO TEE STATE AND PROPERLY DETERI,IINED IT WAS

INSUFFICIENT AS A I,iATTER OF FEDERAL CONSTITUTIONAL LAW.

The district court held under I3*Eg. v. Virginia, 443 U.S.

307 (1979) | that no rational trier of fact could have found Ms.

Bozeman guilty of the offense charged. Appellants apparently do

not seek this Courtrs review of the correctness of that conclu-

sion upon the evidence revealed by the trial record. Rather,

they invoke 9ggl95 v. Ei!g, 449 U.S. 539 ( 1981) ' to cont,end that

the district court "inexplicably" ignored factual findings of

the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals (Brief at 19-20) and failed

to identify its reason for doing sor inasmuch as it did not

specify the particular exception to 28 U.S.C. 522541d) r6 on which

it relied. Appellants also contend that the dist.rict court did

not view all the evidence in the light most favorable to the

prosecution.

5 Section 2254(dl provides that, subject to

federal habeas corpus courts shalI accept

determinat.ions made by state courts.

enumerated except i.ons ,

as correct t,he factual

12

The Dlstrlct Court Properly applied The Relevant Law to

Conclude The Evidence Was Insufficient'

In Jackson v. JiIgi!$, the Supreme Court established the

standard by which federal habeas courts should measure the

constit,ut,ional sufficiency of evidence in stat,e criminal Prosecu-

tions. Jacks-o11 analysis begins with an identification of Lhe

elements of the crime under state law. It then requires an

examination of the record evidence with reference to each element

of the crime, deferring to factual findings of the trial court or

jury and resolving all disputes in favor of the prosecution. It

ends with a determinaEion whetherr oo this evidence, a rational

trier of fact could find every element of the crime proved beyond

a reasonable doubt. 443 U.S. at 318-19.

In the present case, the district court scrupulously

followed the Jackson standard. It first outlined Ehe Jackson

ruler €xplaining t,hat 'a mere tmodicumr of evidence is insuf f i-

cient.' R. 170. See Jackson v. VLrgin-ia, suPra, 443 U.S. at

320. It next determined the elements of t,he crime under Alabama

Iaw, quoting t.he language of the stat,ute under which Ms. Bozeman

was charged, Alabama Code S17-23-1 (1975):

"'talny person who votes more than once at any

election held in t ts more

than one ballot for the same office as his

vot,e at such election, or knowingly attempt,s

to vote when he is not entiffil-86-do sor or

is guilty of any kind of rllgsel_gt _gEaudulent

voting r is guitty of

enphasis added. )

A.

13

The court referred to relevant state case law holding Ehat 'rthe

words "illegal or fraudulentn . o . are . . . descriptive of the

intent necessary for the commission of the offenser m and that n r

[t]fre of f ense denounced by t,he statute . . . is voting more than

oncert ... or voting when the voter is not enEitled to so.' R.

1'71.7 The two essential element,s of knowledge or int,ent to carry

out, illegat-_voting acEijLElL were thus isolated, and the court

t,hen examined the evidence in Bozeman to det,ermine whether these

elements were proved. R. 171-73.

It expressly started from the premise that, under Jackson,

the evidence must be "viewed in a light most favorable to the

prosecution....' R. 170. It f urt.her recognized that " Ii]n

determin ing whether the evi.dence established Ithe] . . . elements

lof the crime as def ined by stat,e law], the court may not resolve

issues of credibility. guncan [v. St,ynchcombe] , 704 E.2d [121311

at 1215 [(11th Cir. 1983)].. Thus, where the evidence conflicts

the court must assume that the jury accepted the prosecution's

version, and must defer to that result. 443 U.S. at 326." Id.

The elements of the offense proscribed by S17-23-1 are employing

fraud to vote more than once. Wilson v. State , 52 Ala. 299, 303

1t875); wilder v. State, 401 SffiA-l51,-TtrO-(Ala. Crim. App.),

cert. deriiEd7701 sSl2ttoz (Ala. 't981), cert. denied, 454 u.s.

TrsT'rr5E?r.

l4

Reviewing t.he trial transcript with these principles in

mind, t.he district court f ound that the only evidence of f ered

against Ms. Bozeman was that. she: (i) picked up "Ia]pproxi-

mately 25 to 30 applications" for absentee ballots from the

Circuit Clerk's off ice during the week preceding t'he run-off , Tr.

18; (ii) was present with three or four other women, who did not

include the votersr dt the notarLzLng of some absentee ballots

which were cast in the run-off, Tr. 57i (iii) may have made a

telephone call to the notary "pertaining Eo ballotsr" Tr. 76'77i

and (iv) spoke to prosecution witness Ms. Sophia Spann about

absentee voting when "it wasn't voting timer" Tr. 184. Addition-

ally, Lhe court found that there tdas evidence Presented by the

prosecution but not admitted by the trial judge3 (v) that [tls.

Bozeman aided Ms. Lou Sommerville, with lls. Sommervillers

consent, to fill out an application for an absentee ballot, Tr.

161-162,159i and (vi) that in an election held prior to the

run-off, Ms. Bozeman may have aided Ms. Sommerville to fill out

an absentee ba1lot , Tt. 173-17 4, 176-77 . FinaIIy, t,he court

observed that evidence on which the state relied in the proceed-

ings below had been stricken from the record by the trial

judge.S R.171-172.

In the proceeding below, appellants stated that the testimony at,

trial showed that lrls. Bozeman'went to t,he courthouse with Julia

Wilder the day that she carried atl these thirty-five or forty

f raudulent Ulltots uP there and deposit.ed them in the clerk's

office." (Record on Appeal, Vol. 2 of 3 at 22-231. The district

court found Ehat the t.estimony to which appellants referred had

been stricken and the jury instructed to disregard it. R. 172.

15

At trial the prosecution had contended t,hat t,he evidence of

Ms. Bozemanrs presence at the notarization vras sufficient to

establish culpability under S17-23-1 because the voters were not

before the notary. Tr. 195-97. Alternatively, in the court

belowr appellants argued that there was suff icient evidence t,o

convict l,ls. Bozeman of conspiracy t ot aiding and abetting.

(Record on Appeal, VoI. 2 of 3, at 22-23). The district court

conscientiously reviewed the state court record in the light most

favorable to both theories, and rejected both as unsupported by

E,he evidence under the standards of Jackson v. Virginia. R.

17 2-17 4 .

Specif ically:

rAlthough there was convincing evidence to

show t,hat t,he t f S 1 ballots were i11e9a11y

cast, there nas no evidence of intent on

Bozeman's-

or helped to forqe the ballots. There is no

evidence thaE shii Took appllcations to any of

the voters, or that she helped any of the

voters fiII out an application or ballotr oE

that she returned an application or ballot for

any of the vot,ers, and no ballot was mailed to

her residence. Thus, there was no evidence

that Bozeman realized

he oflficE of Rollins

that the ballots that she helped to get-is

Even considering the excluded

show that ttts. Bozeman or Ms.

2L-23.

testimony, there was no att.empt to

Wilder deposited any ballots. TE.

16

SimiIarly, even under appellants' theory of aiding and abetting,

"there ... was no evidence of intent.' R. 173. The district

court concluded that:

"The evidence d id not, show Bozeman t,o have

played any role in t,he process of ordering,

collectingr oE filling out the ballots. The

record alio lacks anv evidence of any contEE--oe-r,ween gFzeman ano

mus

indicate Ehat Bozeman knew the ballots to be

Eraudulent. o ( I4.; emphasis added. )

Since on this record nno rrational trier of facE could have found

the essential elements of t,he crime beyond a reasonable doubt,, r"

R. 1'70, the district court ruled that t,he evidence was insuff i-

cient to sustain a constitutional conviction.

Thus, the district court I s analysis of the record 'rras

conducted precisely as required by Jackson. Its independent

review of the evidencer taken in the light most favorable to the

prosecution, was entirely consistent with its responsibilities

under 28 U.S.C. S2254(d).

Section 2254(d) requires a federal habeas court to apply a

presumption of correctness to the factual determinations made by

a state court. summer v. lrlata, 449 u.s. 539 ( 1981). The statute

is designed t.o ensure that. deference will be given to state-court.

evidentiary findings, arrived at after weighing the credibility

of wit,nesses at trial. @,

L.Ed.2d 794 ( 1983); Sumner v. ltata, 1g3g.

u.s. , '7 6

On questions of

17

historical fact, the state courtrs findings are controlling

unless there are substantive or procedural deficiencies in the

findingsr oE the findings are not fairly suPported by the record.

28 U.S.C. S2254(d) (1-8).

The deference required by 52254(d), however, applies g!].1L to

historical facts. A federal habeas court is not bound by

stat,e-court determinations of questions of law, or mixed ques-

tions of law and fact. that, require the application of constitu-

tional principles to historical facts. Cgvler ]r. Sul.livan, 446

U.S. 335, 342 ( 1980); Brewer v. ,Wil1ians , 430 U.S. 387, 403-04

(19771. Accord, !{ainwriqht v. Witt., 53 U.S.L.W, 4108, 4112 (U.S.

Jan. 21 , 1985 ) . The Supreme Court explicit,ly reiterated the

principle in .f=Sf so" , 443 U.S. at 318, citing the leading

opinions which announced it, Townsend v. Saigr 372 U.S. 293r 318

11953); Erown v. A11en, 344 U.S. 443t 505-07 (1953) (opinion of

Justice Frankfurter). This court has also held consistently in

cases involving questions of law or mixed questions of 1aw and

fact t,hat the Presumption of correctness does not aPPly. 9S9,

€.g:, @, 684 F.2d 794, 803-04 (1lth Cir. 1982)l

cert,. denied, 1 O3 S.Ct. 1798 (1982); Dickerson v. State o!

4l-abama, 667 F.2d 1354, 1368 (11th Cir. 1982) cert *gig9, 459

u.s. 878 (1982); Gunsby v. Wainwriglrt, 596 F.2d 654t 555 (5t,h

cir. 19791 , g-err.- 9s!is9, 444 U.S. 946 (1979). And the law of

the Circuit is sett,led that determinations of the sufficiency of

the evidence involve the application of lega1 judgment requiring

18

an independent review of the record. @, 632

F.2d 605, 540 (5th Cir. 1980), cert. denig9, 451 U.S. 1028

(1981); see also Ep-ray-Bilt_:r. I,ntersoII-Rand Wor-13-Esge, 350

F.2d 99 ( 5th Cir.. 1 965 ) .

A federal district court which makes a proper analysis of a

Jackson v. Vir_ginia claimr €rs the court below did here, affronts

no rule or policy of 52254(d). By viewing the evidence "in a

light, most f avorable t,o the prosecution" (R. 170 ), presuming

"that the jury accepted t,he prosecution's version" of conflicting

evidence (fg. ), and ndeferIing] t,o that result" (!{. ) ' the court

not merely accepts all findings of historical fact which the

state courts actually made in favor of the prosecution, but every

such finding which they might have made. To be sure, the

district court may disagree with t,he state court rs ultimate

conclusions regarding the sufficiency of the evidence, 443 U.S.

at 323-24, but these conclusions are the very paradigm of

judgments which are not 'entitled to a presumption of correct,ness

under 28 U.S.C. 52254(d)" because they represent 'a mixed

determination of 1aw and f act t,hat requires the application of

legal principles to the historical facts ...', Cuyler v.

Su1livan, supra, 446 U.S. at 341-342i conPgfg Jackson v.

Yirginiar 443 U.S. at 318 ("A federal court has a duty to asssess

the historic facts when it is called upon t,o apply a constitu-

tional st.andard to a conviction obtained in a state court").

Against the background of these settled principles, lye turn now

t9

to appellants I argument,

more r oE that t,he court

fulfilment of this duty.

t,hat Sumner v. Mata demands something

below did something less, t,han the

B. In Enforcing ilackson v. Virgi,nia, the District Court

was Nor nequi;6d-6- AcGFm.Ee pindings rhar rhe

Evldence Was Sufficient.

Appellants I contention that, a federal court enforcing

Jackson v. Virginia must give deference to state-court findings

under Sumner v. Mata misconceives the whole point of Jackson and

the whole point of Sumner. ff this contention had merit, Jackson

claims could never be enforced, because it is qlgry the case

that f ederal habeas proceedings rais ing A=cf son claims are

preceded by ( 1 ) a st,ate jury finding that the evidence is

sufficient to prove every element of the offensei 12) a state

trial-court finding that the evidence is sufficient to support

the jury's verdict, and (3) a state appellate-court finding of

that same f act. Federal-court deference to t,hese omnipresent

findings would render the Jackson decision an exercise in

futility, the Jackson opinion an absurdity.

The Jackson Court was not unaware of this point. See 443

U.S. at 323 ("The respondent,s have argued . . . that whenever a

person convicted in a staLe court has been given a 'fulI and fair

hearing' in t,he state system -- meaning in this instance state

appellate review of t,he sufficiency of the evidence further

federal inquiry . . . should be foreclosed. This argument would

20

prove far too much.'). Indeed, the precise question debated in

the Jackson opinion $ras whether In re Eig:I$t 397 U.S. 358

(1970) required federal habeas courts to review state-court

factual findings to the extent necessary to enforce the federal

constitutional requirement of proof beyond a reasonable doubt as

the condition precedent to a due-process criminal conviction.

{gSEEgg's pIain, clear answer to that question was yes.

There is nothing in this answer that is inconsistent with

gg5g in the slightest measure. Sumner was based squarely on 28

U.S.C. 52254, and merely held t,hat t,he requirements of 52254

applied to findings of fact of state appellate courts as well as

findings of fact of state trial courts. Well before either

Sumner or Jackson, it was settled law that federal habeas courts

rrere required to defer to state t,rial-court findings of fact,

such as the jury's finding of guilt, or the trial judgers finding

of the sufficiency of the evidence, under the conditions speci-

f ied by 52254. 9E' *-, La. Vj*-lee v. Del1e E, 410 U.S. 690

( 1 973 ) . The reason why Jackson nonetheless concluded that

federal habeas courts could review these findings independently

to determine whether the evidence of guilt was constitutionally

suf f icient is obvious. f t is t.hat any case in which the Jackson

test, of constitut,ional insufficiency of the evidence is met is a

fortiori a case in which S2254(d) explicitly permits federal

habeas corpus redetermination of the facts because "the record in

the State court proceeding, considered as a whole, does not

21

fairly support Ithe] factual determination" of t,he jury thaE

every element of guilt was proved beyond a reasonable doubtr oE

Ehe factual findings of the state trial court and appellate

courts that the evidence was sufficient for conviction. In

short, every substant,ively valid Jackson claim is, by definition,

within t,he class of cases in which 52254(d) permies (and Townsend

v, Sain, 372 U.S. 293 ('l 963), requires) federal habeas corPus

redetermination of state-court fact finding. Sumner v. tlata

neither requires a federal district court to ignore, nor to

"explainr' this patent.ly obvious point.

The Distrlct Courttg View of the Evidence Was Not

Inconsistent With Bactual Flndings of the Alabana Court

of Crimlnal Appeale

Appellants further urge that the court below disregarded

specific findings of historical fact by the Alabama Court of

Criminal Appeals. They not,e (Brief at, 18) t,hat Judge Hobbs was

able to reduce the prosecution's evidence to a single sentence:

"The only evidence against Bozeman was Rollins' testimony that

she was one of the ladies who brought the ballots to be nota-

rized, that she may have caIled to arrange the meeting, and t,hat

the ladies as a group represented the ballots to be genuine after

he told them that the signators were supposed to be present. " R.

171. Appellants complaln that this sentence does not summarize

C.

22

the trial transcript in language identical to the summary of the

transcript found in the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals I

opinion.

This is a quarrel about opinion-writing phraseology and

nothing eIse. For while appellants contend t,hat the district

courtrs factual findings were 'considerably at odds with the

facts found by the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals in the same

caser (Brief at 19), they point to only three trivial instances

of alleged inconsistencies:

" ( 1 ) Paul Rollins 'testif ied t,hat he had talked with

Bozeman about notarizing the balloc3J 401 So. 2d

at 169 (emphasis supplied) (as opposed to rshe may

have called' )

(2) r!,1r. Rollins stated. . . that he subsequently

went to Pickens County t,o f ind those persons who

had allegedly signed the ballots. ile had

IBozemants] assistance on that occasion, however,

he was not sure he did not go to Pickens County

prior to September 26, 1978. I 401 So. 2d 169 (no

mention of this in the district court opinion)

(3) The state court relied heavily on t,he t.estimony of

Sophie Spann. 401 So.2d at 169-70. The district

court, in contrast, treated her evidence briefly

in section II of its opinion (R. 169); then, quite

inexplicably, ignored the evidence entirely when

it reached the critical summary of the staters

case. (R. 171r." (Appellants' Brief at 19-20.)

Upon examination, even these insignificant discrepancies dis-

aPPear.

23

( 1 ) Judge Hobbs' paraphrase of Rollins' testimony with

respect to the telephone call simply summarizes t,he ful1er

version of that testimony set forth earlier in the district

court's opinion:

rHe [Rollins] also staEed that he received t,wo

calls t,o set up the meeti.g, but, that he could

not remember whet,her Bozeman made either call.

He lat.er testif ied, however, that Bozeman made

one call pertaining to some ballots, but he

was not sure which ba1Io'ts." (R. 166-6Ti

E@naET3 fflEa

Summing up 1ater, Judge IIobbs understandably described this

t,estimony by saying that Bozeman "may have called to arrange the

meeting. n R. 1'71. The only variation between this formulation

and the one employed by the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals was

that the Alabama court wrote that, i{s. Bozeman "had" arranged a

meeting with the notary. The "had,/nay have" line is plainly a

distinction without a differ.ence, since as with all the

evidence Judge Hobbs viewed Rollins' testimony in the light

most favorable to t.he prosecution.

(2) The second of the critical'tfacts" which appellants

claim t.hat Judge Hobbs did not ment,ion is incorrectly quoted.

Corrected, it becomes irrelevant.9

9 Correctly, 'rMr. Rollins stated o . . that he subsequently went to

Pickens County to find those persons who had al1egedIy signed the

balIots. He had [Ms. Bozeman'sJ assistance on that occasion,

however, he was sure he did not qo to Pickens County prior to

seprlmre; EmpEfs6-ada6di.tfr5fe-:ffi

ffiage Hobbs to mention this incident, since it

occurred after the run-off primary in question and involved

24

(3) The third supposed discrepancy of "fact" cited by

appel lants is t,hat the st.ate court " rel ied heavily on the

testimony of Sophie Spann, n while Judge Hobbs treat,ed her

evidence "briefly." In summarLzLng Ehe record, the Alabama Court

of Criminal Appeals did not indicate specifically the facts on

which it based its conclusion t,hat the evidence was suf f icient,

saying only that the evidence was circumstantial and confusing in

several instances , 401 So.2d at, 1'10. Even if appellants are

correct that, the Alabama court relied "heavily' on Fls. Spann's

t,estimony, there is nothing in t,he testimony cited by that court

or cont,ained in the trial transcript linking Ms. Bozeman Eo Ms.

Spannrs absentee ba11ot. Neither the ballot application nor the

baIIot contained a signature PurPorting to be that of Ms.

Bozeman. According to the Alabama court, all that Fls. Spann said

with regard to lts. Bozeman is that they were life-Iong friends

who had a conversation about voting absentee "when it wasnrt

voting time.o Tr. 184.10 That same conversat,ion is described by

another unrelated elect.ion.

duced at trial by the defense

and was not treat,ed otherwise

testimony about it was intro-

show 1,1s. Bozeman I s good f aith

the Alabama court.

The

to

by

10 According to the Alabama Court, I{s. Spann testif ied that,:

(a) "she had never voted an absentee balIot, but that

lBozemanl had come t,o her house and had talked to her

about it.' This occurred "before voting time."

(b) She had known Bozeman all her life.

(c) She had never made an application for an absentee ballot

nor had she ever signed her name to one.

25

the court below. R. 159.11 Judge Hobbs treat,ed the testimony of

Ms. Spann in t,he same vray that he treated all other testimony

by highlighting only those aspects of the evidence that could be

viewed as materially supporting t'ls. Bozemanrs conviction of the

charges in the indictment.

Thus, Judge llobbs did not disregard or disagree with any

facts found by the state appellate court. IIis sole disagreement

was with the state court I s ultimate conclusion that those facts

added up to sufficient proof to allow a reasonable mind to find

l.ls. Bozeman guilt,y beyond a reasonable doubt. The rule laid down

in summer v. trlata, 449 u.s. 539 ( 1981), requires t.hat federal

habeas courts must specify t,heir reasons for denying state

factual findings a presumption of correctness under S2254(d) if

and wh.en they disregard those findings. Since Judge Hobbs did

(d) She knew l{ilder, but knew Bozeman better; Wilder had never

come to her house nor ever discussed voting with her.

(e) She went to Cochran to vote and was informed that an

absentee ballot was cast for her in A1iceville.

401 So.2d 169-70.

11 Judge llobbs'summary of the Spann testimony went as follows:

nsophia Spann testified that she did not sign an

application or a balIot. She also stated that

when she went t,o her usual polling place, she was

told that her absentee ballot had been cast. She

stated that Bozeman came at some time prior to

the runoff and asked if Spann wanted co vote

absentee, and Spann said she did not. JuIia

Wilder witnessed Spann 's .gggljg!.i.g. " ( R. -Ttr9;

Ein-F'E'e'siE-ffife?) .-

26

not disregard any state-court findings, he was obviously

obliged to st,ate reasons for doing something that he did not

Cf. Brewer v. Williams, 430 U.S. 387, 395-397, 401-406 (1977).

In P:-ewer, both part, ies agreed to submit the case to the

federal district court on the basis of the state-court record.

The district court made findings of fact based on it,s examination

of that record. It found a number of facts in addition to those

which t,he state courts had found, but none of its f indings

including the supplemental findings conflicted with Ehose of

the State courts. The Supreme Court held that the district court

had fully complied with t,he strictures of 28 U.S.C. 52254(d). 430

U.S. at 397.

Here too, while Judge Hobbs made some additional findings,

none of his findings conflict,s with any historical facts found by

the Alabama courts. Appellants' att,empt now to f ind some

inconsistency between specific factual findings of the Alabama

Court of Criminal Appeals and the factual findings of the

district court, below is groundless.

rI. TEE INDICTUENT AGAINST I'TS. BOZEMAN WAS FATALLY DEFECTIVE IN

TEAT IT FAIT.ED TO INFORTIT IIER OF THE NATURE AND CAT,SE OF TEB

ACCT'SATION

The indictment f iled against l'ls. Bozeman failed in numerous

respects to provide the level of notice required by the Sixth

Amendmentrs guarantee that in all criminal cases the accused

not

do.

27

shall receive "not,ice of the nature and cause of the accusationn

against her. Each of t,hese failures, standing alone, amounts to

a denial of constitutionally required notice; together, they add

up to a stunningly harsh and egregious denial of notice, a right,

which the Supreme Court has deemed rthe first and most universal-

ly recognized requirernent of due process. " Smith _v._ S]!Iad[, 311

U.S. 329, 334 (1941); see also CQle v. Arkansas, 333 U.S. 196,

201 ( 1948).

The district court found that t,he indictmenE failed t,o

provide any notice of a number of charges which were submitted to

the jury. Ms. Bozeman was tried,'to put it simp1y... uPon

charges that were never made and of which [she was] ... never

not,if ied. " R. 183. She did not discover the precise charges

against her, "unti1 [she] . . . had rested Iher] . .. cElS€. n R.

182. The district court held that she was thereby denied due

process.

The Indictment lrlas Constit,utionally Defective In That

It Palled To Provide Fair Notlce Of Alt Of The Charges

On Whlch The Jury Was Permitted To Return A Verdict Of

Guilt,

The district court noted t,hat various statutes and theories

of Iiability as to which the indictment provided no notice

whatsoever were incorporated into Ehe charges submitted to the

jury as the basis for a finding that Ms. Bozeman had violated

S17-23-1 by 'any kind of illegal ... voting." The indictment is

A.

28

set forth at pages 3-4, s-g3Ig. In each of ics three counts it

ostensibly tracked various provisions of S17-23-1. It alleged

disjunct,ively with other charges in Count I Ehat Dls. Bozeman had

"votIed] illega1ly or fraudulenEly"' and in Counts II .nq III

that she had "cast illegal or fraudulent absentee ballot,s. " Only

in Count III was any factual specificat,ion provided; and t,here it

vras alleged that IUs. Bozeman had deposited fraudulent absentee

ballot,s which she knew to be fraudulent. In none of the counts

was any elaboration given to that portion of the charge which

accused i'ls. Bozeman of having 'votledl illegally" or having 'cast

i1legal .., absentee ba1lots."

In the instructions to the jury, t,he t,ria1 judge did frame

elaborat.e charges under which [tls. Bozeman could be convicted of

ilIegal voting. After reading S17-23-1 to the jury, he explained

the statuEers provision against "any kind of illegal or fraudu-

lent voting" by def ining t.he terms "i1IegaI" and "f raudulent. tr

Tr. 201. Concerning the term "illegalr" he instructed the jury

that, 'illegal, of course, means an act that, is not, authorized by

law or is cont,rary to the layr.' Tr . 201 . He then instruct,ed the

jury on four statutes: Ala. Code S17-10-3 (1975) [miscited as

S17-23-3), Tr. 202i A1a. Code S17-10-6 ( 1975) [miscited as

S17-10-71, Tr. 202i AIa. Code S17-10-7 (1975), Tr. 203-204i and

Ala. Code S13-5-115 (1975), TE. 204-205. None of these statutes

or their elements was charged against I'ls. Bozeman in the indict-

ment. Their t,erms provided numerous new grounds on which to

29

convict. The jury was thus authorized to find Ms. Bozeman guilty

under S 1 7-23-1 if she had acted in a manner trnot authorized by or

. .. contrary to' any one of the provisions of a number of

statutes not specified or even hinted at in the indicLment.

For example, the jury was first instruct,ed on S17-10-3,

miscited by the trial judge as S17-23-3, which sets forth certain

qualifications as t,o who may vote by absentee balIot. The trial

judge instructed that, under S17-10-3 a person is eligible to vote

absentee if he will be absent from the county on election day or

is afflicted with'any physical illness or infirmity which

prevents his attendance at the poIIs. " Tr. 202. Thus a finding

by t,he jury t,hat one of the absentee voters had not been physi-

cally 'prevent Ied] " from going to the polls to vote in the

run-off would have constituted the finding of an ract not

authorized by ... or ... contrary to' S17-10-3, necessitating i{s.

Bozemanrs conviction under S17-23-1 even t,hough she was given no

notice in the indictment that such proof could be grounds for

liabilit.y.

The trial judge then instructed the jury EhaE S17-10-6'

miscited as S17-10-7, requires, illg alia, that all absentee

ballots nshall be sworn t.o before a Notary Public" except in

cases where the vot,er is conf ined in a hospital or a similar

inst,it,ution, or is in the armed forces. Tr. 203. Furt,her, under

S17-10-7, the trial judge stat,ed that the notary must s\{ear that

the voter opersonally appeared" before him. Tr. 203. Accord-

30

inglyr €Vidence Ehat. Ehe voters were not present at the notariz-

ing, gg9 Tr. 56-64, suf f iced to establish per se culpabilit,y

under S 17-23-1 alt,hough, again, the indictment gave Ms. Bozeman

no warning whatsoever of any such basis for culpability. l 2

The trial judge then instructed the jury that S13-5-115

provides:

"'Any person who shall falsely and incorrectly

make any sworn statement or affidavit as to

any matters of fact required or authorized to

be made under the election laws, general,

primary, special or locaL of t,his state shall

be guilt,y of perjury. The section makes iL

illega1 to make a sworn st,atement, oathr oE

affidavit as to any matters of fact required

or authorized to be made under the election

laws of this state. I'

Tr. 204. Both sentences of this instruction contain egregious

misstat,ements concerning S I 3-5- 1 1 5. The f irst, sent,ence rePre-

sents a verbat,im reading of 513-5-1I5 with one crucial error. The

trial judge instructed that S13-5-115 proscribes "falsely and

incorrectly" making the sworn statements described in the

statute, whereas in f act the st,atut,e proscribes the making of

such statements "falsely and corruptly" -- i.e.r with criminal

intent. The second sentence of the instruction, which apparently

12 It is noteworthy that SS17-10-5 and 17-10-7 were amended several

months af ter I{s. Bozeman's trial by Acts 1980, No. 80-732, p.

1478, SS3, 4, and no longer require notarization of the bal1ot.

31

represent.s the t,rial judge's interpretation of S13-5-115, has

the absurd result of naking i11egaI every sworn statement duly

made under the election laws.

Irrespective of t,hese misstatements, the charging of

Sl3-5-115 deprived lls. Bozeman of constitutionally required

notice. The misstatement,s of the terms of a st,atute which tls.

Bozeman had no reason to suspect she was confronting in the

first place only aggravated this denial of due proc""".13

The district court found that the trial courtrs charge, by

explicitly permitting the jury to convict Mrs. Bozeman of casting

an improperly notarized ba11ot, was especially prejudicial

because the only evidence against Ms. Bozeman was her partici-

pation in the notarization. R. 181-82. The indictment contained

no allegations which could have put her on notice that, her

participation in t,he notarizing process was violative of S17-23-1

or in any way criminal. As the district court. said: "There is a

world of difference between forging a person's ballot and failing

to follow the proper procedure in getting t,hat person's ballot

13 the trial judge also misread 517-23-1 in a way which expanded the

charges against Ms. Bozeman. IIe instructed Lhe jury that

517-23-1 penalizes one who "deposits more t,han one ballot for the

same office.' Tr. 201. In fact S 17-23-1 penalizes one who

"deposits more than one ballot for t,he same office as his vote'r

(emphasis added). This omission by the trial judE6 FfiiEETIy

changed the meaning of the statute so that the mere physical act

of depositing two or more ballots at, the same election even

ballots deposited on behalf of other voters violates

517-23-1. It thus produced a new charge against Ms. Bozeman of

which the indictment provided no notice.

32

notarized." R. 183. Yet, three of the four statutes not charged

in the indictment but submitted to the jury as a basis for

convict ion under S 17-23-1 made I'ls. Bozeman I s minor participation

in the not.arizing into grounds of pg se culpabiliEy. At, trial

a large part of the prosecution's case was spent attempting to

prove through the testimony of lilr. Rollins, and through questions

posed to virtually all of the test,ifying voters, that. the

notarizing t,ook place outside of the presence of the voters, and

that ttls. Bozeman had in some rday participated in t,hat notarizing.

Ilence, t.he charges made for the f irst time in the instructions

provided new grounds f or culpabilit,y which were crucial Lo her

conviction.

The court below held that the failure to aIlege these

grounds for culpability in t,he indictment violated Ms. Bozemanrs

Fourteenth Amendment rights. The violat,ion vras a1I the more

significant because evidence of the proper elements of the one

statute charged in the indictment, was insufficient or nonexis-

tent.

The only relevant allegations in the indictment were that

Ms. Bozeman had "voteId] iIlegally" (Count I) or had 'cast

ilIegal o.o absentee ballots" (Counts II and III) in the run-off.

These allegations in no way informed Ms. Bozeman with particula-

rity t,hat she could be prosecuted under the rubric of ilIegal

voting for acts 'not authorized by . . . or . o. contrary to" the

four unalleged statut,es charged in the instructions. But

33

" [n]otice, to comply with due process requirernents, must be given

sufficiently in advance of the scheduled court proceedings so

that reasonable opPortunity to prepare will be afforded, and it

must rset forth the alleged misconduct with particularitY.'' In

re G?u1t, 387 U.S. 1, 33 (1957).

nConviction upon a charge not made would be a

sheer denial of due process.'

D-eJonge v. Oregon , 299 U. S. 353, 362 1 1937 ) ; see also Dunn v.

United Statesr 442 U.S. lO0, 106 11979)i Jackson v. Virginiar 443

U.S. 307, 314 11979) i P-resnell v. CSofgis, 439 U.S. 14, 16

( 1978); CoIe v. Arkansas, 333 U.S. 196t 201 ( 1948).

Ms. Bozeman was plainly subjected to an egregious violation

of the rule that, in order t,o satisfy the Notice Clause of the

Sixth Amendment, an indictment must allege each of the essential

elements of every statuE,e charged against the accused. ESg

Russell v. United St,ates, 369 U.S. 7 49, 761-766 (1962) i Unit'ed

States v. Ramos , 666 F.2d 469, 47 4 ( 1 1t,h Cir. 1982) i Uni,ted

States v. Outler, 559 F.2d 1305, 1310 (5th Cir. Unit B 1981),

EI!. @-!g5!, 455 U.S. 950 (1982); United States v.,.-HaPs, 583

F.2d 216 | 219 reh. 9S!$!, 588 F.2d 829 ( 5t.h Cir. 1978), cert.

denied, 440 U.S. 981 11979); United St.ates v. Strauss, 283 F.2d

34

155, 158-59 (5th Cir. 1960).14 Here, the indictment failed even

remotely to ident,ify the critical elements upon which her guilt

was made to depend at trial.

The indictment. also violated the rule of United States v.

Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1875), that:

nwhere the def inition of an of fence, whettrer

it be at common law or by statute, includes

generic terms, it is not suf f icient t,hat, the

indictment shal1 charge the offence in the

same generic terms as in the definition; but

it must state the species it must descend

t.o the particulars.'

14 rfris rule is followed by the Alabama courts as a proposition of

both Alabama law and f ederal const.itutional Iaw. E, €.9. r

Andrews v. State, 344 So.2d 533, 534-535 (Ala. Crim. APp. ), cert.

ffia 539 (Ara. 1977). rn fact, under alabama-E

Eiffire to include an essential element of the offense in the

indictment is regarded as such a fundamental error that it

renders the indictment void, and objection to such an indictment,

cannot be waived. Seg g-.9.,!!., @t 417 So.2d 611

(Ara. crim. App.-T9efrca-rter@o.Zd 610 (Ala.

irim. App. 1980i, tqrt. aeniffita 11980); Edwards v.

stare ,"37 9 so. zdTI8, TTFTaIa. crim. lpp | 1979)_i DfrfEgn-il

, 351 so.2d 583 (Ala. crim. App. 1977)i Fendrey v. state,

T*o.Za 5OO (Ata. Crim. App. 1971i; ritzgerffi

So.2d 162 (Ala. Crim. App. iitAlt grow 450

(AIa. App. 1946); Nelson v-. state, 2ffi1a. crim. APP.

1973); wirriams v.ffi2d 610 (Ara. crim. App. ), aff 'd,

333 so.ffi); Harmon v. state ' 249 so.2d 369-TAE

crim. App. ), cert. deniedrffi(Ala. 1971 ).

ah

Id. at 558 (citation omitted). The Cruikshank rule is fundamen-

tal to the notice component of due Process. See Essel]--v.-

United States', 369 U.S. 749, 755 (1962). It is apposite to this

case because "i1Iega1tr is unquestionably a "generic term." Kegk

v. United Stq..1!ss ,172 U.S. 434,437 (1899); Goodloe v. P?rratt,

605 F.d 1041, 1045-46 (8th Cir. 19791. An indictment which

charges unspecified illegalities as did Ms. Bozemanrs in

charging her with "votIing] illegally" or "castIing] illega1 ..o

absentee ballots" must, under Cruikshank, "descend to the

particulars" and identify the acts and underlying laws which

atlegedly constituted the illegalities. Iq. In Ms. Bozemanrs

situation, grqilqbqflk required that the indictment allege that

she violated 517-23-1 by failing to comply with each of the four

st,atutes as they were charged against her in the instructions,

and contain specific factual allegations giving her fair notice

of t,he acts which were allegedly criminal under those charges.

Such was the conclusion which Ehe court below derived from

Goodloe v. Parratt,, 605 F.2d 1041 (8th Cir. 1979), where habeas

petitioner Goodloe had been convicted in a state court of

operating a motor vehicle to avoid arrest. Under Nebraska law

t.he crime allegedly commit,ted by the defendant for which he was

subject to arrest, and because of which he was resisting, had to

be proven as an element of the offense of resisting arrest. !].

at 1045. The Goodloe court found that during trial the prosecu-

tion changed the offense it was relying on as the crime for which

36

Goodloe was allegedly resisting arrest. fg. at 1044-1045. This

change denied Goodloe constitutionally required notice. Id. In

addition, irrespective of the change in underlying offenses at,

triaI, the Eighth Circuit held under Cruikshank that Goodloe was

denied consticutionally required notice because the initial

charge against him had failed to include notice of the underlying

offense which Goodloe had alleged1y committed and because of

which he vras a11egedIy resisting arrest. The indictment t,here-

fore failed to "allege an essential subst,antive element. " I4. at

1046.15

The f acts of Goodloe are analogous to t'ls. Bozemanrs case,

since the four statutes invoked against her which the state

failed to charge in the indictment were incorporated as substan-

tive elements of S17-23-1's prohibition against illegal voting.

15 The court reasoned:

"The indictment uPon which Goodloe was tried

charged that he did, in the words of the stat'ute,

runLawfully operate a motor vehicle to flee in

such vehicle in an effort to avoid arrest' for

violating any law of this State.' There is no

indication from this statutory language thatr ds

the trial court held and instructed the juryr 6r

additional element must be proven for conviction:

actual commission of the violation of state law

for which the defendant fled arrest. Once prior

violation of a specific state statute became an

element of the offense by virtue of t'he trial

court ruling, Goodloe was entitled not only to

notice of that. general fact,, but also to specific

notice of what law he was alleged to have

violated. "

Id. at 1045.

37

, watson v- JiEgg, 558 F.2d 330 (5th Cir. 1977). See also

Plunkett v. Estelle, 709 F.2d 1004 (sth Cir. 1983), cert. denied,

104 s.Ct. 1000; Tafpley v. Estelle, '703 F.2d 157 (5th Cir. '1983),

ger!. 4SniS9, 104 S.Ct. 508; Gray v. Rain.s, 662 F.2d 589 (1Oth

Cir. 1981); Von Atkinson v. Smithr 575 F.2d 819 (1Oth Cir. 1978).

The district court followed the basic approach of these cases in

determining that the jury could reasonably have convicted Ms.

Bozeman of a crime not charged in the indictment. The court's

determination was based on its examination of the trial as a

who1e, including the charge, the arguments of counsel, the theory

of the prosecution and the evidence. R. 179-80. The court

re jected appellants' argument that I'ts. Elozeman was challenging

Ehe jury charge rat.her than the indictmentrs failure t,o provide

fair notice of the charge. As appellantsr now realLze, "Judge

Hobbs considered the instruction on stat,utes not contained in the

indictment to amount to a constructive amendment to the charging

instrument, allowing the jury t,o convict the def endant for an

unindicted crime. SeeT Plunkett v. Estelle, 709 F.2d 1004 (5th

Cir. 1 983 ). " Brief at 22.

This was entirely correct. It was the challenged indictment

which created the substantial potential for abuse eventually

realized by the oral charge. Eg Stromberg v. California, 283

U.S. 359, 364-55 (1931); Te5$iniello v. Chicagot 337 U.S. 1r 5

(1949). As Judge Hobbs explained, Ms, Bozeman "went into court

facing charges that Ishe] ... had rstolen' votes and ended up

38

being tried on the alternative theory that [she] had committed

one or more st.atutory errongs in the notarization of ba11ots.'r R.

182-83. Because the indictment failed to give lvls. Bozeman fair

"notice of the nature and cause of t,he accusation" against her as

required by the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments, the district

court properly overturned her convictiorr. l6

The Indictment Was Fatally Defective In That It Failed

To Include Constitutionally Sufficient Allegations

Concerning The Charges Of Fraud

Additional grounds support the district courtrs judgment

invalidating the indictment. Each count alleged at least in the

alternative that Ms. Bozeman had in some way committed fraud

through her voting activities in the run-off. For the reasons

set forth in the following subsection ( 1 ), these allegations of

f raud f ailed to provide t,he quantum of notice required by the

B.

1 6 Stromberg and Terminiello demonstrate the fallacy of appellants'

21-22). Sincemault lay in the indictment, no

objections to the jury instrucLions were required to preserve Ms.

Bozeman I s challenge to it. Svkes is inapposite because ttls.

Bozeman properly and consistently--aEEacked the indictment for its

failure to give her adequate notice of the charges throughout the

state proceedings, beginning with her plea filed on [lay 28, 1979,

and continuing through her motion for a nev, trial filed on

November 28 , 1979. E;4\gg is inappos ite because ['1s. Bozeman

raised the noLice issue-6i-?irect appeal to the Alabama Court of

Criminal Appeals, and that court entertained the issue on the

merits. 401 So.2d at 170. See, e.9.., !gg!.!Iglrt of ulster

County v. A11en, 442 U.S. ffi, T-4F54

ffiuse the Arabama courtrs consi<ier-ffiFrigirt, ro

notice to be so fundamental that objections to indictments on the

ground of lack of proper notice cannot be waived. Note 14 EuPra.-

$, g:.L-, Boykin v. Alabama, 395 u.S. 238, 241-42 ( 1969 ) .

39

Sixth Amendment. Moreover, as not,ed in subsection (2) be1ow,

Counts I and II failed to a1lege fraudulent intent or knowledge

as a necessary element, of the offense charged. Counts I and II

failed to allege any S rea whatsoever. Only in Count III was

Dls. Bozeman accused of having acted with fraudulent intent.

The prejudice caused by these constitutionally defective

counts is incalculable since Dls. Bozeman was convicted under what

can OnIy be desCribed aS an "extra-general verdict. " In a

general verdict, the jury gives its verdict g each count

without elaboration as t,o the f indings of fact. ESg generally 75