Greenberg v. Veteran Opinion

Public Court Documents

April 17, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Greenberg v. Veteran Opinion, 1989. 82828164-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f3344818-700e-4ed9-b376-20b02087991b/greenberg-v-veteran-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

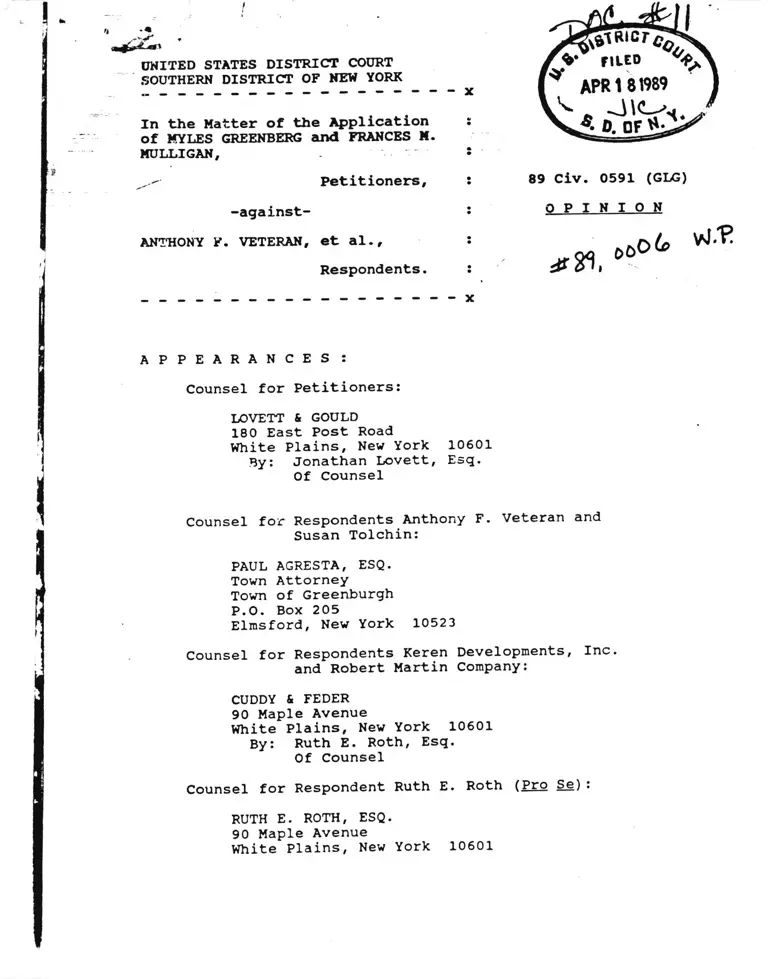

UHITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

X

In the Matter of the Application

of MYLES GREENBERG and FRANCES M.

MULLIGAN,

Petitioners,

-against-

ANTHONY F. VETERAN, et al.,

Respondents.

89 Civ. 0591 (GLG)

O P I N I O N

A P P E A R A N C E S :

Counsel for Petitioners:

LOVETT & GOULD

180 East Post Road

White Plains, New York 10601

By: Jonathan Lovett, Esq.

Of Counsel

Counsel for Respondents Anthony F. Veteran and

Susan Tolchin:

PAUL AGRESTA, ESQ.

Town Attorney

Town of Greenburgh

P.O. Box 205

Elmsford, New York 10523

Counsel for Respondents Keren Developments, Inc.

and Robert Martin Company:

CUDDY & FEDER

90 Maple Avenue

White Plains, New York 10601

By: Ruth E. Roth, Esq.

Of Counsel

Counsel for Respondent Ruth E. Roth (Pro Se):

RUTH E. ROTH, ESQ.

90 Maple Avenue

White Plains, New York 10601

Counsel for Respondents Anita Jordan, April Jordan,

Latoya Jordan, Anna Ramos, Lizette Ramos,

Vanessa Ramos, Gabriel Ramos, Thomas Myers,

Lisa Myers, Thomas Myers, Jr., Linda Myers,

Shawn Myers, and National Coalition for the

Homeless:

-and-

Local Counsel for Respondents Yvonne Jones, Odell A.

Jones, Melvin Dixon, G e n Bacon, Mary

Williams, James Hodges and National

Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, Inc.White Plains/Greenburgh Branch:

PAUL, WEISS, RIFKIND, WILTON & GARRISON

1285 Avenue of the Americas

New York, New York 10019

By: Jay L. Himes, Esq.

Cameron Clark, Esq.

Melinda S. Levine, Esq.

William N. Gerson, Esq.

Of Counsel

Counsel for Respondents Yvonne Jones, Odell A. Jones,

Melvin Dixon, Geri Bacon, Mary Williams,

James Hodges and National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People, Inc.

White Plains/Greenburgh Branch:

GROVER G. HANKINS, ESQ.

NAACP, Inc.

4805 Mount Hope Drive

Baltimore, Maryland 21215-3297

By: Robert M. Hayes, Esq.

Virginia G. Shubert, Esq.

COALITION FOR THE HOMELESS

105 East 22nd Street

New York, New York 10010

Julius L. Chambers, Esq.

John Charles Boger, Esq.

Sherrilyn Ifill, Esq.

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

Andrew M. Cuomo, Esq.

12 East 33rd Street - 6th Floor

New York, New York 10016

Of Counsel

E T T E L, D.J.:

Federalism is a concept whose vitality is perceived by some

to be rather fluid. There are those, for example, who beli|ve lt

worthy only of lip service and that, as a general proposition, if

a matter may be brought in a court it may be brought in faderal^

court. To that thinking, the retort is quite simple: "federal

courts are courts of limited Jurisdiction.-’ Still others, while

cognizant of the notion's existence, perceive its recognition as

-seasonal" in nature, going in and out of style with the

philosophical predilections of a given administration and the

quantity and temperament of its judicial appointments. As to that

point of view, we note only that the document serving as

federalism's source is entitled to greater deference than the whims

of current majoritarian thinking.

There are those, however, who share our view that federalism

is a neutral constant of federal jurisprudence, the necessary

product of our dualist system. The proceeding before us is rife

with federalist implications, and it is our recognition of and

respect for those concerns which shapes and guides our handling of

the matter.

New York has provided an avenue for judicial review of state

and municipal administrative action under N.Y. Civ. Prac. L. A R.

("NYCPLR") §§ 7801-06 (McKinney 1981 t Supp. 1989), the so-called

Article 78 proceeding. Judicial review under these provisions

(1978) .

Owen Fm,i o . 6 mention CO. V. Kroger, 437 U.S. 365, 374

1

generally is limited to determining whether the official’s actions

constituted an abuse of discretion, were unsupported by sufficient

evidence, or were contrary to existing law. Id̂ . at § 7803.

Although an Article 78 proceeding cannot be initiated in federal

court, Chicago. Rock Island & Pacific R.R. Co. v. Stude, 346 U.S.

574, 581 (1954), it is contended that such a proceeding nonetheless

may be removed here so long as a federal question is asserted in

the Article 78 petition — apparently no matter how tangential or

attenuated — or if the respondents allegedly were acting pursuant

to federal law protecting equal rights — even if that law

parallels similar state law mandating like action.

As will become clear, we harbor certain reservations as to

this interest in "federalizing" Article 78 proceedings generally

and this proceeding in particular. Fortunately, at least in this

case a solution presents itself. Animated chiefly by due respect

for the principles of comity and federalism that serve as the

essential bedrock for healthy federal-state relations, we find that

abstention is proper in this case and, consequently, we remand the

matter sua sponte to the court from whence it originated and

belongs (in our view) — the New York Supreme Court for the County

of Westchester.

I. BACKGROUND

This case, at its core, is unmistakably a product of the

"NIMBY Syndrome" — i.e., that syndrome triggered by proposals to

locate prisons, public housing, waste facilities, and other such

2

mmunity additions usually perceived by the targeted community as

undesirable, the abiding characteristic of which is to ensure that

the proposed facility be placed somewhere if it must but -fiot In

My Backyard.- The public project at issue here is the proposed

construction of emergency housing for the homeless.

in January of last year, the Town of Greenburgh, in

conjunction with the County of Westchester, proposed to build

emergency or -transitional- housing to accommodate 108 homeless

families on land owned by the County in the Town. The proposed

developer is West H.E.L.P., Inc. ("West HELP"), a not-for-profit

corporation formed for the express purpose of constructing housing

for the homeless of Westchester County. It is generally

acknowledged that the vast majority of homeless people who would

qualify for residence in the West HELP project are minorities,

specifically blacks.

In response to that announcement, a number of Greenburgh

residents living in the area immediately surrounding or adjacent

to the proposed site formed the Coalition of United Peoples, Inc.

("COUP"). COUP'S purpose, de facto or otherwise, is to coordinate

opposition to the West HELP project and, most importantly, to

ensure that the project is not constructed in COUP'S backyard. As

part of those efforts, COUP began a drive under N.Y. Village Law

§§ 2-200 to 2-258 (McKinney 1973 & Supp. 1989) (the "Village Law")

to incorporate an area encompassing the proposed West HELP project

as a separate village to be denominated the Village of Mayfair

3

follwood.1 On September 14, 1988, pursuant to section 2-202 of

the Village Law, COUP presented an incorporation petition to

Creenburgh Town Supervisor Tony Veteran, whose responsibility it

is in the first instance to determine whether the petition comp

with the requirements of the Village Law. In accord with section

2-204 o f 1 the Village Law, a public hearing on the matter was

conducted on November 1 at which oral testimony was received. Town

supervisor Veteran then adjourned conclusion of the hearing until

November 21 for the sole purpose of entertaining written comments

on the petition.

Also on November 1, and prior to any decision by Town

Supervisor Veteran on the merits of the petition, various citizens

of the Town of Greenburgh, a number of homeless people living in

Westchester County, the National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People, and the National Coalition for the Homeless

joined forces as plaintiffs in a federal action in this court

against COUP, certain of its members, and Town Supervisor Veteran.

V. neutsch. No. 88 Civ. 7738 (GLG). The complaint alleges,

inter alia, a civil rights conspiracy amongst the named defendants

pursuant to 42 U.S.C. S 1985, the ostensible purpose of which is

to deprive plaintiffs of voting, housing, and emergency-shelter

2 Just how incorporation of the proposed viliage would

obstruct construction o ? housing for « » "So u "

admittedly County-owned I . the newly formed village

Presumably, COUP believes thf “ tlofnecessary zoningwould be able to so bog down and delay approval or n r become

and other permits that pursuit of the prelect

undesirable.

4

ights grounded in federal and state law. Plaintiffs also sought

a declaratory judgment directing that Town Supervisor Veteran

reject the allegedly discriminatory incorporation petition,

contending that such a result would be consistent with the proper

execution of his oath of office. The COUP defendants moved to

dismiss that action on various grounds (among them ripeness and

standing). The motion was adjourned sine file pending determination

of the instant matter, which had been removed to this court during

the interim.

Town Supervisor Veteran, apparently not in need of a federal

court order controlling his actions, issued a decision on December

1, 1988 rejecting COUP'S incorporation petition (the "December 1

Decision"). In a carefully worded opinion, six specific grounds

were enumerated as the bases for the decision.

(1) the proposed boundaries are not described with "common

certainty," as required by section 2-202 of the Village Law;

(2) the proposed boundaries, where ascertainable, evidence an

intent to discriminate and are gerrymandered to exclude black

residents, rendering the petition violative of "rights granted by

the federal and state constitutions";

(3) the petition was prepared for the invidious purpose of

"preventing the construction of transitional housing for homeless

families," rendering it violative of "rights granted by the federal

and state constitutions";

(4) substantial petition signatures were obtained under false

pretenses;

5

(5) substantial petition signatures are irregular; and

(6) numerous Torn residents (particularly newer re

are not identified as would-be inhabitants of tbe proposed village,

as required by section 2-202 of tbe Village Lav.»

.Cnder tbe express provision of section 2-210 of tbe Village

review of a town supervisor’s decision on an incorporation

petition may be bad only through an Article 78 proceeding on

grounds that tbe decision -is illegal, based on insufficient

evidence, or contrary to the weight of evidence.- Eleven days

after Town Supervisor Veteran issued his decision on the COUP

petition, two COUP members instituted an Article 78 pr

New York Supreme Court challenging that decision. On January 30

of this year, the respondents in that proceeding filed a petition

for removal in the Southern District of New York, designating the

matter as related to the pending peutsch action.

s Decision be reversed and the Urging that the December 1 Decision

petition to incorporate the village of Mayfair Knollwood be

sustained, the Article 78 petition sets forth five specific bases

allegedly supporting the relief requested:

(1) since section 2-206(3) of the Village Law requires that

testimony offered at a petition hearing "must be in writing" and

that the "burden of proof shall be on objectors," and since only

oral testimony was taken at the November 1 hearing, Veteran’s

5 principally as * r.eS? ‘ c°[onThich,C i S l alia, drops

complaint was filed in the Bja£||!l act „u a civil rights

defendant Veteran as a member

conspiracy.

6

ions were contrary to the requirements of the Village Law and

thus illegal or, alternatively, his decision was not supported by

sufficient evidence; F -- x

(2) since a town supervisor's authority under section 2-206

Jf'the Village Law to review incorporation petitions allegedly is

strictly ministerial (i.e., limited to assessing the validity of

only those objections related to petition requirements set forth

by the statute), and because the statute does not provide for an

examination of or inquiry into the petitioners' intent, Veteran's

decision is illegal because it went beyond the scope of his

ministerial authority or, alternatively, his perceptions of

discriminatory intent are not supported by sufficient evidence;

(3) since under section 2-206 of the Village Law the sole

evidence Veteran purportedly was allowed to consider was that

adduced at the November 1 public hearing and reduced to writing,

his reliance on material received during the period he allowed for

further written comment between November 1 through 21 renders his

decision illegal or, alternatively, contrary to the weight of the

objecting evidence received at the November 1 hearing;

(4) since no objections allegedly were filed with respect to

the means by which petition signatures were gathered or as to the

sufficiency of the list of regular inhabitants, Veteran's decision

is illegal or is unsupported by sufficient evidence; and

(5) since the petitioners' opinions, motives, or intentions

are matters allegedly protected by the First Amendment of the

7

%

i

k

states constitution. Veteran's decision violates those

rights/

Freely expressing our doubt as to the propriety of removal

this case, a conference in chanters was scheduled to discuss, inter

a u r ' i i , Whether, as g e n e r a l proposition. Article 78 proceedings

nay be renoved to federal court, (ii) if 80' “hether renoval

this case is justified under either of the pertinent statutory

provisions invoked, to be discussed into. '<hether'

assuming the instant proceeding can be renoved, Principles of

abstention dictate that we stay our hand or disniss in deference

to a state proceeding addressing sone or all of the issues raised.

Memoranda and letters on these subjects were submitted to the

court prior and subsequent to the scheduled conference. Generally,

all parties are of the belief that the Article 78 proceeding at bar

could be and properly was renoved, and only counsel for the Article

78 petitioners expressed any concern as to possible abstention

implications. In sum, it is readily apparent that the parties are

content to be before this court and believe that this court is the

proper forum in which to address the Article 78 matter; no motion

to remand is contemplated. Notwithstanding this state of affairs,

but consistent with the primacy of this court's obligation to

protect its jurisdiction, the court has engaged in its own research

I “ 7 a infra we add only that it appears certain4 As discussed into, 1we ^ the procedures employed

of the questions bearing on the 1 g Y f his £uthority under the

and whether Veteran e*ceeded the sc of New York law (indeed, from

w h a t T e ̂ e ^ r b ^ pefitTolfeVs' counsel, certain of the state

quest Tons3 may be makers of first impression, .

8

r #»

the matter. See Railway Co. v. Ramsey. 89 D.S. (22 Wall.) 322,

328 (1874) (noting court’s authority to remand §ua sponte if

jurisdiction is found lacking); Cutler v. Rae, 48 U.S. (7 How.)

729, 731 (1849) (holding consent of parties does not confer federal... - .....

jurisdiction; it remains "duty of this court JtciL take notice of the

want of jurisdiction, without waiting for an objection from either

party"). Finding that, even if this proceeding properly was

/

removed, we should abstain pursuant to familiar jurisprudential

considerations, we now remand this proceeding sua sponte. See

Corcoran v. Ardra Ins. Co.. 842 F.2d 31, 36-37 (2d Cir. 1988)

(holding "that when the district court may properly abstain from

adjudicating a removed case, it has the power to remand the case

to state court"). II.

II. DISCUSSION

The right to remove a state case to federal court is, of

course, a unique incident to our federalist system with no

antecedent at common law. Consequently, removal must be founded

upon one of the statutory bases provided by Congress. Gold-Washing

and Water Co. v. Keves. 96 U.S. 199, 201 (1877). The instant

petition invokes two such statutory provisions. First, the Article

78 respondents contend that removal is warranted under the

infrequently utilized "refusal clause" of the civil rights removal

statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1443 (2). Second, it is contended that the

assertion of the First Amendment challenge to the December 1

Decision presents a federal question and warrants removal under the

9

eral federal: removal statute, 28 U.S.C.

consider each of these provisions in turn.

$ 1441(b) We

-t

i a. 28 P.S.C. S 1443(21

- Respondents devote the lion's share of their argument to the

propriety of removal in this case under the refusal clause of the

civil rights removal statute.' The refusal clause permits removal

in those cases where a person acting "under color of authority" is

"refusing to do any act on the ground that it would be inconsistent

with [federal law providing for equal rights]." Of the precedent

that exists construing this awkwardly worded statute, perhaps the

two leading decisions were rendered by two of this circuit's most

learned and respected jurists.

Certainly, the most complete analysis of the statute provided

to date in any circuit is then District Judge Newman's opinion in

Bridgeport Edu. Ass'n v. Zinner. 415 F. Supp. 715 (D. Conn. 1976),

which sets out the criteria to be employed in a refusal clause

analysis. Generally adopting what he termed Judge Newman’s

"exhaustive and scholarly review of the subject," now Chief Judge

Brieant, sitting by designation and writing for the two-member

majority in White v. Wellington. 627 F.2d 582 (2d Cir. 1980),

succinctly summarized the relevant inquiry: the refusal clause

"may be invoked when the removing defendants [state or municipal

officials] make a colorable claim that they are being sued for not

acting 'pursuant to a state law which, though facially neutral,

would produce or perpetuate a racially discriminatory result as

10

Led.'* Id,, at 586 (quoting tinner, <15 F. Supp. at 722). The

statute is exceptional in that it allows the presence of a federal

defense to control the question of jurisdiction, tinner, <15 P.

Supp. at 723 n. 7 (citing IflulffifUl* iNashville P-P- v- X°ttleY ,

v*211 U.3 ^ 1 4 9 (1908)).

Recognizing, we think, that the statute, if left open-ended,

could lead to the -federalization" of standard state cases

involving challenges to official state or municipal action, an

important limitation (consistent with the existing legislative

history) has been read into the law’s meaning. To state a

-colorable claim- under the statute, the removal petition must

contain a good faith allegation that there exists a conflict

between the state law in issue and a federal law protecting equal

rights. AS Chief Judge Brieant put it, the removal petition must

allege "a colorable claim of inconsistent state/federal

requirements.” Wellington, 627 F.2d at 537. £en also Armeno v,.

nridcenort Civil Serv. Comm'n. 446 F. Supp. 553, 557 (D. Conn.

1978) (Newman, J.) (noting refusal clause permits removal when

official "declined to observe state requirements that he believes

are inconsistent with the obligations imposed on him by a federal

law protecting equal rights"). The basis of the conflict

requirement seems self-evident: without a colorable federal-state

conflict, the need to remove to federal court to ensure the proper

vindication of superior federal mandates is not manifested. When

federal and state interests are compatible, the state court is

poised to assure that the defendant’s parallel justification for

11

/

ion under state law is given proper consideration. ££-

■eiUnoton. 627 F.2d at 590 (Kaufman, J.. concurring) (state

officials will seek -extraordinary* option of removal under the

refusal clause and forego the familiar confines of a state forum

■because the federal issue they seek to litigate is

substantial").

indeed. Judge Meskill, dissenting in Wellington, characterized

the colorable conflict requirement as the -jurisdictional

touchstone- under the refusal clause. Wellington, 627 F.2d at 592.

The Wellington majority concurred with that assessment:

f n 1 with Judge Meskill*s

iS«s

of^the removing defendant must be -colorable,

at 586-87. Where the majority and dissent parted ways was on

what would constitute a -colorable conflict.- In that case, the

defendants had phrased their removal petition in the alternative;

i.e., they contended that they had not violated the applicable

state statute or, if it were found that they had, then they acted

as they did for to do otherwise would have been inconsistent with

the requirements of federal law protecting equal rights. Judge

Meskill felt that alternative allegations of this nature did not

justify removal under the exceptional provisions of the refusal

clause. Id. at 591. The majority, however, found -no reason why

12

removal petition cannot contain inconsistent allegations in the

nature, here, of a traditional plea of confession and avoidance

without confession,- so long as the petition contains -a colorable

claim of inconsistent state/federal requirements." at 587.

Put differently, the contrary nature of state law need not be a

matter definitively resolved, so long as the defendant

alternatively can assert in good faith a colorable claim of

conflict with federal law. IcL, at 590 (Kaufman, J., concurring).

Guided by these holdings, we find that a colorable conflict

between federal and state law is neither asserted in the instant

petition nor can such a conflict in good faith be found to exist.

As outlined supra. Town Supervisor Veteran denied the

incorporation petition on six enumerated grounds. Only grounds (2)

and (3) implicate federal concerns relating to equal rights; the

remaining grounds for denial are largely ministerial in nature,

based entirely on the filing requirements of New York's Village

Law. Grounds (2) and (3), however, each conclude that even though

the Village Law "does not specifically address itself to the

•intent' of the petitioners, I firmly believe that the rights

granted by the federal and state constitutions transcend the

procedural technicalities set forth in the Village Law." December

1 Decision ! 2 , at 4; ^ ! 3, at 6. The referenced constitutional

protections are not identified in either the December 1 Decision

or the removal petition, but it seems plain that the allusions are

13

r 5 ,the Fourteenth Amendment's command of equal protection. Thus,

respondents conclude, the Village Lav, though neutral on its face,

would produce a discriminatory result if applied in ignorance of

federal constitutional proscriptions* and therein rests the

5 Citing only Gomillion v Liahtfoot. 364 U.S. 339 (I960),

respondents' memorandum notes simply that "Supervisor Veteran

relied on federal constitutional protections against race

discrimination . . . [and] [t]here can be no genuine

these provisions are lavs 'providing for equal civil rights.

Respondents' Conference Memorandum at 9. S S S . also T° ™ V Z

Greenburgh's Memorandum at 4 (same). gomillion struck down a

gerrymandered plan redefining the boundaries of the City of

Tuskegee, Alabama as violative of the Fifteenth Amendment. That

amendment provides that the right of citizens to vote shall not be

denied on account of race or color. Justice Whittaker, noting that

the Gomillion plaintiffs were not being denied their right to vote

"in the Fifteenth Amendment sense" (i.e., they could still vote,

albeit not within the newly defined city limits), concurred in the

decision but on grounds that the "fencing out" of black citizens

"is an unlawful segregation of races of citizens, in violation of

the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment . . . •

Id. at 349. Although of no moment, we think Justice Whittaker

makes a cogent point. More importantly, however, it has been

suggested that the Supreme Court has come ultimately to embrace

Justice Whittaker's analysis. See Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S.

725, 748 (1983) (Stevens, J., concurring) (noting "the Court has

subsequently treated Gomillion as though it had been decided on

equal protection grounds") (citing Whitcomb v.Chavis, 403 U.S. 124,

149 (1971)). Accord City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 86-87

& n .7 (1980) (Stevens, J., concurring). We will not belabor the

reader with citation to a number of Court cases, both majority and

concurring opinions, which have cited Gomillion in the Fourteenth

Amendment context. Suffice it to say that gerrymandering by race,

although a Fifteenth Amendment violation under gomillion, certainly

falls within the reach of the Equal Protection Clause as well.

That additional support could be especially pertinent here since

those who would be excluded from the allegedly gerrymandered

boundaries of the Village of Mayfair Knollwood would not, iplifce

the plaintiffs in Gomillion. be deprived of their pre-existing

right to vote (here, in the Town of Greenburgh). See especially

Caserta v. Village of Dickinson, 491 F. Supp. 500, 506 n.14 (S.D.

Tex. 1980) (distinguishing Gomil1ion since excluded plaintiffs

retained their pre-existing right to vote; "[t]hose not within the

Village of Dickinson boundaries have merely maintained their status

quo as members of Galveston County"), aff'd in relevant part, 672

F.2d 431, 432-33 (5th Cir. 1982).

14

!

jKrable conflict. Respondents' Conference Memorandum at 8-9.

^Whether or not this is so, however, we believe respondents

argument misses a crucial point.

Wellington repeatedly references and requires a conflict

between federal and "state law," not a state law or statute. The

corpus of pertinent "state law" under Wellington. 11 seems to us'

must necessarily include state constitutional law, for it is a

fundamental m ucim of any constitutional society, as New

that constitutional mandates govern and delimit legislative

regulatory enactments of the majority. Thus, at least one New York

court has noted that incorporation petitions, even if in compliance

with the ministerial requirements of the Village Law, will not be

sustained if their end is that of advancing racial discrimination.

Tn re Rose. 61 Hisc.2d 377, 305 N.Y.S.2d 721, 723 (Sup. Ct. 1969),

a f f M j - , . 36 A. D. 2d 1025, 322 N.Y.S.2d 1000 (2d Dep't 1981, .‘

Although state law in such a case may be found by resort to the

State Constitution, as opposed to the Village Law,

law- nonetheless which forbids the invidious result.

AS is made plain by the December 1 Decision, Town supervisor

Veteran relied on both the Federal and State Constitutions in

rejecting the petition. No conflict between the pertinent federal

and state constitutional provisions was perceived by Supervisor

Veteran; he acted at the command of botji. SSS especially

6 Whether a town supervisor, as °PP°s^ ^°ssed inURos4 and

authority to make that determination was not discussed ----

is not addressed here.

15

linciton. 627 F.2d at 587 (central inquiry is whether official

subjectively believed an actual conflict between federal and state

law existed); id. at 590 (Kaufman, J.f concurring) (same). Nor is

any such conflict to be found by reference to existing state law;

federal and New York constitutional law governing equal protection

are in harmony. See Seaman v. Pedourich. 16 N.Y.2d 94, 262

N.Y.S.2d 444,' 450 (1965) (noting New York's equal protection

clause, embodied in N.Y. Const, art. 1, § 11, "is as broad in its

coverage as that of the Fourteenth Amendment"); Dorsey__v -

Stuwesant Town Coro. . 299 N.Y. 512, 530 (1949) (holding protection

afforded by New York's equal protection clause is coextensive with

that granted by Fourteenth Amendment), cert, denied. 339 U.S. 981

(1950) .

The case at bar, therefore, is readily distinguishable from

Cavanaah v. Brock. 577 F. Supp. 176 (E.D.N.C. 1983) (three-judge

panel), a case cited by respondents. Removal in that case was

permitted under the refusal clause because the removing defendants

argued that the relevant provisions of the North Carolina

Constitution. which were alleged to be in conflict with the

Fourteenth Amendment, either had been rescinded or, if in effect,

could not be complied with due to the contrary dictates of the

Federal Constitution. Id̂ . at 179-80. Here, the Equal Protection

Clause will embrace whatever discrimination allegedly would have

occurred, supra note 5, and Seaman and Dorsey make plain that the

corollary state constitutional provision is at least as broad as

its federal counterpart. Thus, if Town Supervisor Veteran was

16

^^«guired by the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

to act as he did, he similarly would be required to so act by the

equal protection clause of the New York Constitution since the

latter is to be read la pari materia with its federal relation.

^Xertainly, notwithstanding Supervisor Veteran's belief that

he was complying with state constitutional law, respondents'

ability to remove this case under the refusal clause is not lost

if the removal petition contains an allegation based on that

belief. Such is the teaching of Wellington. Respondents, however,

must in good faith be able to plead alternatively that if they were

not acting in accordance with state law, then their refusal to so

act was the product of conflict between federal and state mandates.

Wellington. 627 F.2d at 587. No such good faith assertion can be

made here. Federal and state law are coextensive in this area.

See also Fed. R. Civ. P. 11 (requiring that any "pleading, motion,

or other paper" submitted to the court and signed by an attorney

be grounded in good faith belief that its substance is warranted

by facts, law, or good faith argument for the law's modification).

The jurisdictional paragraph of the removal petition

acknowledges this reality. See Verified Petition for Removal 5 11,

at 4-5 ("proposed village petition was rejected in part on the

basis of federal and state Constitutional and statutory provisions

providing for equal rights . . . [and,] [accordingly, this action

may be removed to this Court by respondents pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§ 1443(2)") (emphasis added). The petition's conclusion, however,

does not state the law. If it did, then in every case challenging

17

te or municipal action relying on federal authority parallelling

cited state law, the case could be removed to federal court, m i s

is not the conundrum contemplated by the refusal clause; indeed,

it is no conundrum at all. Federal and state law must not merely

parallel one another; they must be in conflict (or, more

accurately, there must be a good faith allegation of conflict).

See especially In re Quirk. 549 F. Supp. 1236, 1241 (S.D.N.Y. 1982)

(refusal clause satisfied since colorable conflict existed between

federal court order and New York civil service law); In re Buffalo

Teachers Fed'n. 477 F. Supp. 691, 694 (W.D.N.Y. 1979) (removal

under refusal clause appropriate since "state defendant caught

between the conflicting requirements of a Federal [court] order and

of state law"); Zinner. 415 F. Supp. at 718 (noting refusal clause

M •intended tc enable state officers, who shall refuse to enforce

state laws discriminating in reference to [civil rights] on account

of race or color, to remove these cases to the United States courts

when prosecuted for refusing to enforce those laws'") (quoting

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 1115 (1863) (statement of Rep.

Wilson)). Contrasted with those scenarios, respondents here are

being prosecuted for having acted as they saw fit under the State's

equal protection clause, not for having failed to do so, and that

provision tracks its federal namesake.

Consequently, we find that there is no colorable conflict

between federal and state law in this case, and that removal, if

‘ 18

other than those providedr

^xstified here, must be found for reasons

under the refusal clause.7

•' fr. 28 P.S-g. « 1441(bi

Urjder 28 V-p.C. S 1441(b), "(a]ny civil action of which the

district courts have original jurisdiction founded on a claim or

right arising under the Constitution, treaties or laws of the

United States shall be removable without regard to the citizenship

or residence of the parties." Clearly, the assertion of the First

Amendment claim in the petition presents a federal question. We

are not so sure, however, that an Article 78 proceeding

automatically qualifies as a "civil action" under the removal

statute.

The term "civil action" (or the predecessor term "civil suit")

has been capaciously defined. Thus, the Supreme Court has opined

that appeals from state or municipal administrative action via writ

of prohibition or mandamus may qualify for removal:

The principle to be deduced from [our] cases

is, that a proceeding, not in a court of

justice, but carried on by executive officers

in the exercise of their proper functions, as

7 Our decision on the refusal clause might appear

aratuitous in light of our holding infra that, even if this case

was^properly11 removed, principles of abstention warrant a remand

Our ruling on the abstention/remand, however, might be d i f f e t

were we to find that the case could be removed under ref

clause Congress's explicit determination that state officials

Hfort^th^oV/on'ora1; ^ oStUnIS

does? al?er a?l, have a federal as well as state component.

in the valuation of property for the just

distribution of taxes or assessments, is

purely administrative in its character, and

cannot, in any just sense, be called a suit;

and that an appeal in such a case, to a board

of assessors or commissioners having no

judicial powers, and only authorized to

determine questions of quantity, proportion

„ and value, is not a suit; but that such an

appeal may become a suit, if made to a court

or tribunal having power to determine

questions of law and fact, either with or

without a jury, and there are parties litigant

to contest the case on the one side and the

other.

TTnshur Countv v. Rich. 135 U.S. 467, 475 (1890). Record

commissioners of Road Improvement Djst. No. ? v- St. Louis S.Wr_

Rv, Co.. 257 U.S. 547, 557, 559 (1922). CjU Weston v. City Council

of Charleston. 27 U.S. (2 Pet.) 449, 464 (1829) (the term -civil

suit," in defining Supreme Court's appellate jurisdiction over

state cases, is a comprehensive one including various modes of

proceeding; so long as an adversary proceeding inter partes, it

qualifies as a "civil suit").

That said, it is beyond cavil that a statutory appeal of

administrative state action, whether or not it involves diverse

parties or a federal question, may not be filed in federal court.

npoartmenf of Transp. and Dev, of Louisiana v. Beaird-Poulan, Inc^,

449 U.S. 971, 973-74 (1980) (Rhenquist, J., dissenting from denial

of certiorari) (citing Stude, 346 U.S. at 581). Following from

that principle, we doubt that Congress intended the term "civil

action" under the removal statute to be so sponge-like as to allow

its absorption of every conceivable type of proceeding involving

appeal from state or municipal administrative action which touches

20

/

n a federal question. To believe otherwise is to suggest that

Congress was ignorant of notions of comity and federalism that are

such an important part of our constitutional and jurisprudential

fabric. F+ T^nlm S.W. RV. . 257 D.S. at 554 ("[a]n

administrative proceeding transferred to a court usually becomes

judicial, although not necessarily so") (emphasis added).*

in New York, an Article 78 proceeding, although admittedly

civil in nature, is manifestly circumscribed by the terms of the

statute, and it possesses numerous indicia distinguishing it from

a typical inter partes civil action. It is a self-styled "special

proceeding," NYCPLR § 7804(a), designed to supplant the previous

writs of certiorari, mandamus, and prohibition, id^ at § 7801.

Consequently, and consistent with the predecessor writs, the scope

of review in an Article 78 proceeding is narrowly confined, id*, at

§ 7803, and the relief recoverable is limited, id*. at § 7806. A

number of other substantive and procedural irregularities are

unique to this form of proceeding. See especially NYCPLR § 103

(expressly noting distinction between "civil action" and "special 8

8 Indeed, the proper application in the modern context of

19th-Century Court precedent defining "civil action is a matter

Jot free 7rom doubt. Those Courts could not possibly have

envisioned the rise of populism, the demise of economic: due

process, and ultimately the advent of the New De?l, all of whic

r-adicallv chanqed economic life and governance in this society.

Mirroring S e federal model produced by the New Deal a multitude

Of administrative agencies now permeate the ranks or state

decisionmaking. In that context, we think it a J^itimate question

to wonder whether the Supreme Court and/or Action" so as to

appropriate to define expansively the term^ ci stateallow the universal removal of garden-variety appeals from state

administrative action.

21

eeding,- and vesting courts with authority to convert a special

proceeding into a civil action if nature of claim or relief sought

goes beyond confines of the for~r>; J. Weinstein, H. Korn, » A.

Miller, r-f s a a a a s * * * » <1980 ‘ Supp- Dec’ 1988>

(discussing nature of Article 78 proceeding); D. Siegel^ Handboci

ga JteM very Civil rraciisa 55 557-70 (1978 8 supp. 1988) (saae, .

Given the unique nature of the action, the fingerprints of

federalism inevitably will be so spread upon an Article 78

proceeding that we doubt the proceeding ordinarily can be wiped

clean of its essential state administrative character by the mere

presence of a federal question, no matter how insignificant, and

be rendered removable thereby. Therefore, to permit generally the

removal of Article 78 proceedings under 28 U.S.C. 5 1441 1S- we

think, to invite disruption with well-settled notions of comity

and federalism. See, Srivello y, poard of Adiustment, 183

F SUPP. 826, 828 (D.N.J. I960, (holding appeal of state

administrative action via writ of certiorari, although nominally

denominated a -civil action at law.- did not constitute a -civil

action- as that term is used under the general removal statute);

v onhl ic s e r v ^ o m l ^ u i i ^ i - 129 F - SUPP' 722' 725

7 7 7 ^ 7 example, an Article. 7 ^ P

different from the administrati » ^ _ The court there held

Liberty Mutual Ins. Cô ., 367 U. .■ l ratiVe determination on a

that a challenge to a Texas federal court as a

worker’s compensation cla diversity but only because Texas law

.•civil action" o n l e n a e an proceeding [; ]

provides that such a c h a . without reference to what may have

£ln decided'by U.e^exas Industrial Accident] Board." M , at

354-55 (emphasis added).

22

V

/

Mo. 1955) (finding appeal of state administrative action by

writ of certiorari to county court "was a mere continuation of the

administrative proceeding" and, thus, could not be removed). Eat

see City Of ovatonna v. Chicago , Roc* Island jPacific F-R, S

298 F^Supp. 919, 922 (D. Minn. 1969) (and cases ci'fd therein).’0

Despite our misgivings, we assume for present purposes that

an Article 78 proceeding may be removed under the general removal

statute, for our concerns and respect for federalism can be

accommodated in this case by the law of this circuit relating to

10- Our conclusion would by necessity be when

removal of an Article 78 p r o c s , c l v i f r l g h t r r e m o r a ? statute

discussed ^ since an Article 78 proceeding Uthe^rescribed

avenue of challenge to administrative ac clause if thata proceeding must be removable under the refusal clause

clause is to be given effect ^ J ^ h e federal interest in an

Article. 781 proceeding ^may so Predominate as to warrant^the

cases^nvolving^ppeals1*^^ state* PPVr^^ ^te“ t°^ecco quotas imposed

^moval1 Xn tho cases,

however, the local committees ^ere authorized by d l l

^ i c u ^ ^ s ^ ^ ^ f e » = ^ | r ^ - g

the tobacco crop. See pavis v. d°Yner ̂ 2 Vi? PvnnVars Racinq

- 8C5n d 2tdhe8rl51r> 8 6 3 - ^ ft, Cir._ »5if

s i b i u t r t ^ t

cert- denied.^ 7 however, we remain dubious

to the wisdom of a general rule permitting the removal of

Article 78 proceedings. Although several Article 78

have been removed to courts in this circuit, this specific question

has never been addressed. Obviously, it could be argued that the

ability to remove such proceedings heretofore simply

assumed without the need for extended discussion. We are not so

sure.

23

remand authority. The Supreme Court has held that removed

actions generally may not be remanded except within the narrow

confines of the remand statute, 28 D.S.C. § 1447(c) (i.e., that the

case was removed improvidently or without jurisdiction). Thermtrgn

Prod. . Inc, v. Hermansdorfer, 423 U.S. 336, 345 & n. 9 (1976). Th^

Second Circuit, however, has found a practical exception to that

rule, concluding -that when the district court may properly abstain

from adjudicating a removed case, it has the power to remand the

case to state court.- gorcopan v. Ardra Ins. Co_«., 842 F.2d 31, 36-

37 (2d Cir. 1988). Accord Naylor v. Case and McGrath, Inc^, 585

F. 2d 557, 565 (2d Cir. 1978). The exception, among other things,

is grounded in the reality that no purpose would be served by

retaining a removed case and then dismissing it on abstention

grounds, if applicable, rather than simply remanding the matter to

the appropriate state forum. Because the fingerprints of

federalism referenced earlier are so clearly discernible here, we

find abstention to be appropriate and we thus remand the matter in

accord with the remand exception outlined in Ardra Insurance

c. Abstention

Jurisprudential limitations on our jurisdiction long ago

announced in Bur ford v. Sun Oil Co_̂ , 319 U.S. 315 (1943) largely

control our view of this matter.

Burford, of course, involved a challenge to the validity of

state administrative action permitting the drilling of certain

wells in an east Texas oil field. The legal challenge was

24

ftiated in federal court on grounds of diversity and federal

Question (due process); the case at bar was removed to federal

court on the latter basis. In granting dismissal of the Burford

challenge in the exercise of its equity Jurisdiction, the Court

noteciJ" ____ _ _ ___ -

Although a federal equity court does have

jurisdiction of a particular

may, in its sound discretion, whether its

jurisdiction is invoked on ground of diversity

of citizenship or otherwise, "refuse to

enforce or protect legal rights, the exercise

of which nay be prejudicial to ^ e p u b i i c

interest" rrmited States ex rel. Greathouse v_f_

^ 2 8 9 U.S. 352, 360 (1933)); for it "is In

the public interest that federal courts of

eouity should exercise their discretionary

power with proper regard for the J^htful

independence of state governments

out their domestic policy." [Pennsylvania y^

Will jams. 294 U.S. 176, 185 (1935).]

Burford, 319 U.S. at 317-18 (footnotes omitted). Those concerns

were found to be present in Bufford, which involved important state

interests (the division of oil-drilling rights) that were the

subject of comprehensive state regulation.

The Second circuit has distilled the principles underlying

Burford thusly:

rBurford! abstention is appropriate when a

federal case presents a difficult issue o_

state law, the resolution of which wiU have

a significant impact on important state

policies and for which the state has Prov^ ^

a comprehensive regulatory system with

channels for review by state courts

me rBurford, 319 U.S.] at 333-34, 63

l CX. at lioT^oir In short, federal courts

should "abstain from interfering wi

specialized, ongoing state regulatory

schemes."

25

(

1 lance of American Insurers v. Cuomo. 854 F.2d 591, 599 (2d Cir.

1988) (quoting L e w v. Lewis. 635 U.S. 960, 963 (2d Cir. 1980)).

In the case at bar, petitioners seek the incorporation of the

Village of Mayfair Knollvood, which requires a grant of state

authority. ^.Y. Const, art. 10, $ 3.; Village Law $ 2-200; 1 E.

McQuillen, The Law of Municipal Corporations §§ 1.19 & 2.07b (3d

ed. 1987) ("McQuillen") . As Town Supervisor Veteran alluded to in

his December 1 Decision, the legal concept of village incorporation

was created to allow residents of a particular area the opportunity

to band together for the purposes of securing fire and police

protection and other public services, such as water and sewer.

December 1 Decision 1 2, at 3-4. Given these uniquely local

interests, and particularly in an age of increasingly scarce

resources (both natural and fiscal), it would seem beyond

peradventure that the State of New York retains as profound an

interest in certifying village incorporation petitions as does the

State of Texas in certifying oil-drilling licenses. See especially

Gomillion. 364 U.S. at 342 (recognizing "the breadth and

importance" of a State's power "to establish, destroy, or

reorganize by contraction or expansion its political subdivisions,

to wit, cities, counties, and other local units"); Hunter v. City

of Pittsburgh. 207 U.S. 161, 176, 178-79 (1907) (noting creation

of municipal incorporations and definition of their size and nature

are matters peculiarly within jurisdiction of the States). Accord

1 McQuillen § 3.02, at 235; 2 McQuillen at §§ 4.03 & 7.03; C.

Rhyne, Municipal Law §§ 2-2 & 2-26 (1957) . Thus, that as a general

V ... . . . .....

26

oposition federal courts should not be

which the village incorporation process

unremarkable and inevitable conclusion.

muddying the

swims seems

waters

to us

in

an

Further, and acting partly as confirmation of the above state

interest. New York has established a "comprehensive regulatory

system with channels for review by state courts or agencies,"

amprican Insurers. 854 F.2d at 599, to assess the propriety of

village incorporation petitions:

* the statute specifically identifies what geographic areas may

be incorporated as a village, section 2-200 of the Village

Law;

* it spells out in elaborate detail who may petition for

incorporation and what the contents of the petition must

comprise, section 2-202;

* it establishes a public notice and hearing requirement once

a petition is filed with a town supervisor, again setting

forth in great detail the hearing requirements, section 2-204;

* it specifically notes what objections may be lodged

a village petition, and how and when these objections should

be presented, section 2-206;

* it sets forth a specific timetable for action on the petition

following hearing, and outlines the prerequisites for the

written decision that the town supervisor must issue on the

matter, section 2-208;

* it specifically provides that review of a town supervisor's

decision may be had only by resort to an Article 78 proceeding

on grounds that the "decision is illegal, based on

insufficient evidence, or contrary to the weight of the

evidence," section 2-210(1);

* it requires that appeal via the Article 78 route must be taken

within 30 days from filing of the town supervisor's decision,

section 2-210(2), and that such appeal shall have preference

over all civil actions and proceedings, section 2-210(4)(e); *

* it goes on to delineate the right to and procedures for

conducting an election to determine the question of

incorporation, sections 2-212 to 2-222;

27

it sets forth the procedure for £<.1=1.1 jeview^ of

incorporation election, j and Prov .̂ ..<ons 2-224 to 2-230? and, original election is set aside, sections 2 224 to

finally,

it outlines the formalities of incorporating, the PJ°«Jures

, S S r H ^ ^ ^ c n s “ d232thto S 3 *

If this does not constitute a comprehensive statutory scheme,

regulating in this case a matter within the fundamental

prerogatives of the state, then the court would be hard pressed to

identify such a scheme. Certainly, the scheme is as comprehensive

and the interest as strong as those existing in levy, where the

Second Circuit directed abstention due to Hew York's "complex

administrative and judicial system for regulating and liquidating

domestic insurance companies." levy- 635 F.2d at

paraphrase Burford, we think the regulation of village

incorporations so obviously involves a matter of uniquely state

policy that wise judicial discretion counsels in favor of avoiding

needless federal intervention in the state's affairs, especially

since a comprehensive regulatory scheme to address this matter has

been put in place. Burford, 319 U.S. at 332.

That this proceeding also implicates a federal question does

not alter our conclusion. fiurfold, too, involved a federal

question but, as the Supreme Court noted, ultimate review of that

question before the Court was preserved fully by their action. Id.

at 334. Accord Levy, 635 F.2d at 964.

Moreover, the federal question here asserted may never need

be reached. Four of the five challenges to the December 1 Decision

28

asserted in the Article 78 petition (claims (l)-(4), delineated

supra) involve challenges to the propriety of Veteran's actions

under the Village Law.11 Petitioners' counsel has represented that

certain of these questions — particularly those involving the

nature of the local hearing to be held on these matters, how and

what evidence can be received and relied upon, and the scope of the

town supervisor's statutory authority — appear to be matters of

unsettled state law. We have found little case law specifically

addressing the state issues here raised. If the December 1

Decision is reversed on any of these grounds, the First Amendment

assertion will not be reached. When unsettled questions of state

law are susceptible of an interpretation which may obviate the

federal constitutional question presented, the federal court should

defer on these questions — at least in the first instance to

a state tribunal. Orozco v. Sobol, 703 F. Supp. 1113, 1121

(S.D.N.Y. 1989) (cases collected, including Railroad— Comm 1 n— of

Texas v. Pullman. 312 U.S. 496 (1941)). See also Levy, 635 F.2d

at 964 (since federal question was bound with state issues, best

left in the first instance to state courts with review available

11 We add that the existence of these purely state

administrative issues places this case in a posture far different

from that found in Gomil1ion and cases like it, which constitute

straight constitutional challenges to gerrymandered municipal

boundary plans devised upon conclusion of the legislative or

administrative drafting processes. Had the instant incorporation

petition been approved under the Village Law, and the Deutsch

defendants (assuming they had standing) then challenged that action

in federal court on Fourteenth Amendment grounds, we have little

doubt that we properly would have jurisdiction over the subject

matter and that plaintiffs' choice of a federal forum would be

respected. That is not the posture of this case.

29

These concerns militate ltimately before the Supreme Court). The

further in support of abstention.12

M concludes. In words equally applicable here:

The claims [in Buried] amounted to an attack

on the reasonableness of the s^a^e

^ administrative action. Thus ^ e r a l

^ ^ 3 ^ S t e ^ t i ^

creating* i S S S S S s * ! ? t h . ^ i K s ? ? a t i o / o f

S e state scheme • of % S ? e

officialseS«fd the expeditious and evenhanded

12 The Supreme Court has ob s ® \ n vh^ch federal courts

of abstention are not rigid Px9®° ^ reflect a complex of

must try to fit cases ™ £ ions inherent in a systemconsiderations designed to soften th esses>„ ppnn7,oii Co.

that contemplates parallei judi ‘ ^ P ^ 9 (1987). Thus, although

Texaco^ Inc^, 107 S. Ct. ±__ ^ Rurf0rd considerations, the

this case is governed largely Y P certainly is relevant.

existence of ^ l ^ n o t e 9 however, there do existNotwithstanding Pennzoxl s footno ' “ the "various types of

important procedural difference:s hent the product of Burfordabstention. " Pertinenthere w e n o ^ t h a ^ Pfederal ^

abstention is dismissal, ^ hl^e the federal court retaining

issues may be bifurcated ^ \ h^ it^ n t s allowed the option

jurisdiction over the former a _ddress the federal concernsif returning to that forum to ^ d r e s s . t n e^i^ ot Medical

following state review. -Fnq1an (1964)^ ^ Harris CountyE^miners, 375 U.S. 411, *21-22 (1964^. & _ ̂— 15) (dismissal

Comm1rs Court v. Moore, 420 U.£ . ' to remove obstacles to

in Pullman case appropriate if neces ry bifurcate the

state court jurisdiction) . ^ makes n o since to do so

federal and state issues in tbl* i n ' Law's scheme of providing

would potentially frustrate th® . 9 { incorp0ration petitions,

for complete and expeditious review ^ * T ° e ? e n t s of section 2-

Further, consistent with the s?™ bringing a new Article

210(4)(b) of the Village bh® t issues would be substantial

78 proceeding to address solely ,. arcruably rendering that

(given the number of parties in the

"solution" inequitable. Sinces Bu the proceeding whole and

instant proceeding, we choose to P ... was emphasized

remand the entire matter to _ state court whlch' as w * the

in both Burford and Levy, is entirely ®°mP ^ n£e reached) .First Amendment issue asserted here (if it need be re

30

administration of state programs counsels

restraint on the part of federal courts.

Levy. 635 F.2d at 964. Here, Article 78 review under the Village

Law is designed to provide the aggrieved party with the opportunity

forj^xpedited and confined judicial review of state administrative

action. That review is, in essence, largely an extension of the

administrative process itself given the reviewing court's limited

scope and remedial authority, and it is that forum which should be

deciding the state issues which predominate in this matter. If

federal questions are implicated in that process and improperly are

decided, ultimate review before the Supreme Court is preserved.

Abstention, therefore, is warranted here.

Conclusion

Assuming the general removability of Article 78 proceedings,

the instant matter involves a federal question and may be removed

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1441(b). Consistent with Ardra Insurance,

however, and because we would abstain from deciding the issues here

presented under familiar jurisprudential considerations, the

instant proceeding is remanded to the court froni whence it was

removed, the New York Supreme Court for Westchester County.

SO ORDERED.

Dated: White Plains, N.Y.

April /O , 1989April !* )

GERARD L. GOETTEL

U.S.D.J.

31

(212) 373-3234 February 10, 1989

Hon. Gerard L. Goettel

United States District Court for

the Southern District of New York

United States Courthouse

101 East Post Road

White Plains, New York 10601

Matter of Greenberg v. Veteran

______89 Civ. 0591 (GLG^______

Dear Judge Goettel:

On behalf of all removing respondents, I am submit

ting a copy of our additional memorandum in support of

removal.

I also enclose a copy of the first amended and

supplemental complaint in the related case of Jones v.

Deutsch, 88 Civ. 7738 (GLG), served pursuant to Your Honor's

instruction at the February 2, 1989 conference.

Respectfully,

Jay L. Himes

Enclosures

cc: All Counsel

BY HAND

bcc: Homeless Team and Counsel

(212) 373-3234 February 10, 1989

Jonathan Lovett, Esq.

Lovett & Gould

180 East Post Road

White Plains, NY 10601

Timothy Quinn, Esq.

Quinn & Suhr

170 Hamilton Avenue

White Plains, NY 10601

Paul Agresta, Esq.

P.O. Box 205

Elmsford, NY 10523

Jones v. Deutsch

Dear Counsel:

In accordance with the Court's instruction at the

February 2, 1989 conference, I enclose a copy of our first

amended and supplemental complaint. This pleading is identi

cal in form to that submitted on our motion for leave to

amend. The only changes are in paragraph 5, where two

additional homeless families have been added as plaintiffs,

and in the caption and paragraphs 57 and 59, where corre

sponding additions are made.

Sincerely,

Jay L. Himes

Enclosure

BY HAND

bcc: Homeless Team and Counsel