Abrams v. Johnson and United States v. Johnson Join Appendix

Public Court Documents

March 20, 1996

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Abrams v. Johnson and United States v. Johnson Join Appendix, 1996. 5e831ec6-ab9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f336a34b-f32b-4289-a503-8f3b3fb72dfe/abrams-v-johnson-and-united-states-v-johnson-join-appendix. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

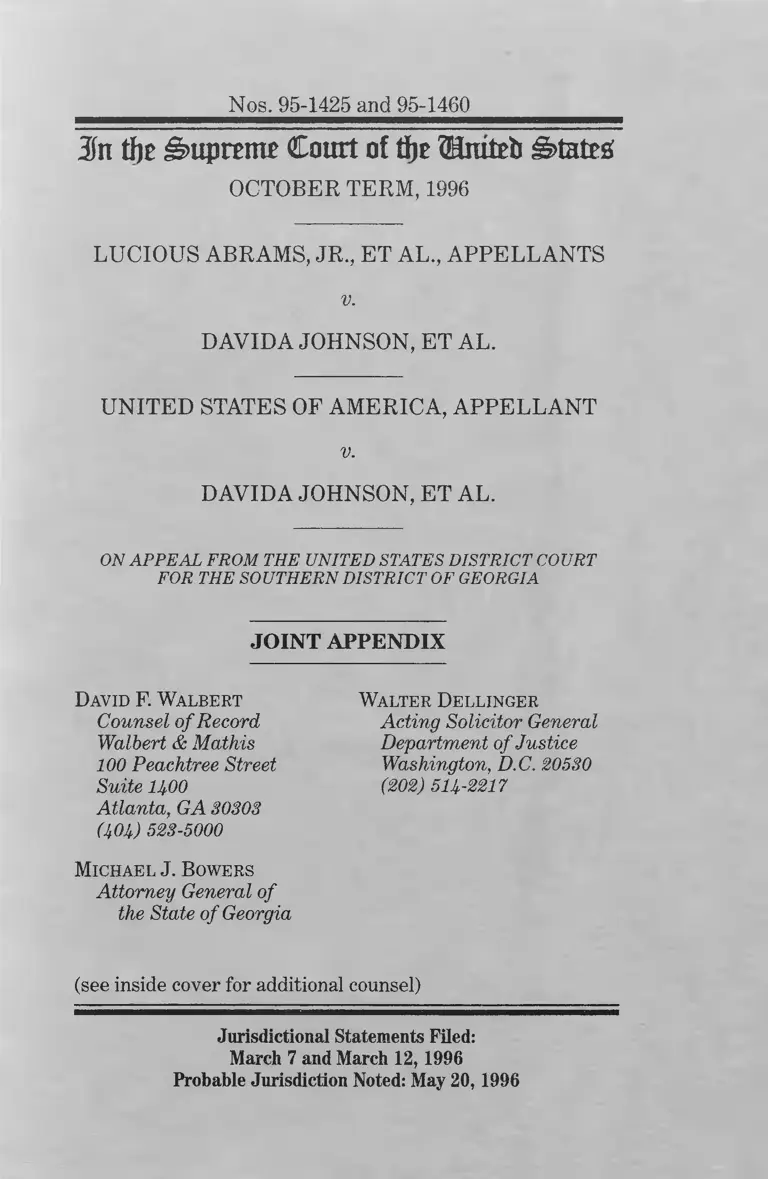

Nos. 95-1425 and 95-1460

3fn tf)£ ^upreim Court of tfjr Miutrb £§>tatr£

OCTOBER TERM, 1996

LUCIOUS ABRAMS, J R , ET A L , APPELLANTS

v.

DAVIDA JOHNSON, ET AL.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, APPELLANT

v.

DAVIDA JOHNSON, ET AL.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

JOINT APPENDIX

David F. Walbert

Counsel o f Record

Walbert & Mathis

100 Peachtree Street

Suite 14.OO

Atlanta, GA 30303

(hOU) 523-5000

Michael J. Bowers

Attorney General o f

the State o f Georgia

(see inside cover for additional counsel)

Walter Dellinger

Acting Solicitor General

Department o f Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 5U-2217

Jurisdictional Statements Filed:

March 7 and March 12,1996

Probable Jurisdiction Noted: May 20,1996

Dennis R. Dunn

132 State Judicial Building

Atlanta, GA 30334

Counsel fo r Appellees Miller et al.

A. Lee Parks

Counsel o f Record

Kirwan, Parks, Chesin & Remar, PC.

75 Fourteenth Street

2600 The Grand

Atlanta, GA 30309

(404) 873-8000

Counsel for Appellees Johnson, etal.

Laughlin McDonald

Counsel o f Record

Neil S. Bradley

Maha Zaki

Mary Wyckoff

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation, Inc.D

44 Forsyth Street — Suite 202

Atlanta, GA 30303

(404) 523-2721

E laine R. J ones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

J acqueline Berrien

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc

99 Hudson Street

New York, N.Y. 10013

Gerald R. Weber

American Civil Liberties Union o f Georgia, Inc.

142 Mitchell Street, S.W.

Suite 301

Atlanta, GA 30303

(404) 523-6201

Counsel fo r Appellants Abrams, et al.

3fn tf)t B>u$mm Court of tfje MnitEb

OCTOBER TERM, 1996

No. 95-1425

LUCIOUS ABRAMS, JR., ET AL., APPELLANTS

v.

DAVIDA JOHNSON, ET AL.

No. 95-1460

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, APPELLANT

v.

DAVIDA JOHNSON, ET AL.

ON A PP EA L FROM THE UNITED STATES

D ISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOU THERN D ISTRICT OF GEORGIA

JOINT APPENDIX

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

A. Relevant docket entries in the United States

District Court for the Southern District

of Georgia, Augusta Division ...................... 1

From the 1995 Trial:

B. Testimony of Joseph K a tz .......... ................... 9

l

11

Page

C. [Corrected] Report of Joseph Katz, State’s

Exhibit 170 , with selected attachments from

Tabs 3 and 4 .................. ................... . 30

D. Testimony of Allan J. Lichtman ..................... 53

E. Report [by Allan J. Lichtman] on Issues

Relating to Georgia Congressional Districts,

Exhibit DOJ 24, with selected tables, and

charts from Appendix 1 ............................ 62

F. Testimony of Ronald E. Weber ...................... 84

G. Report of Ronald E. Weber, Plaintiffs’

Exhibit 82 and tables from Attachment E .. 96

H . Joint Statement of Undisputed Fact ............ 116

From the Remedial Phase:

I. Three declarations by Selwyn Carter

(Abrams Exhibit 35) ...................................... 141

J. Testimony of Linda M eggers.......................... 152

K. Testimony of Sanford Biship .......................... 155

L. Argument: Laughlin McDonald...................... 157

M. Testimony of Selwyn Carter ............... 159

N. Argument: David Walbert ................. 184

O. Testimony of Linda M eggers......................... 186

P. Maps and Charts

1. Congressional Redistricting Plan MSLSS

(House passed)(Abrams Exhibit 37) . . . . . 190

Ill

Page

2. Congressional Redistricting Plan

AMICUSR (Lewis-GingrichXAmicus

Exhibit 1 ) . . . . . . . . . . . . ........ .................. 192

3. Congressional Redistricting Plan

ABRAMS A (R. 296 and R. 319)............ 194

4. Congressional Redistricting Plan

ABRAMS C (R. 296)................................ 196

5. Congressional Redistricting Plan

ACLU1A (Abrams Exhibit 36) . . . . . . . . 198

6. Congressional Redistricting Plan Plaintiffs’

Remedy 4 (R, 342) ............ . 200

7. Congressional Redistricting Plan Plaintiffs’

Remedy 4X (R. 363) ........... 202

8. Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 47-49 (race

maps from AMICUSR of DeKalb,

Bibb, and Muscogee Counties) .............. 204

9. Chart: Black population in Georgia’s

Eleventh District in F irst Enacted Plan

(DeKalb, Richmond, and Bibb

Counties).................................................... 207

Q. ORDERS noting probable jurisdiction

and consolidating appeals .......................... 208

DATE

7/12/95

8/2/95

8/14/95

8/14/95

U nited States D istrict Court

FOR THE SOUTHEREN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

A ugusta D ivision

CIVIL ACTION NO. CV 194-008

L ucious Abrams, J r ., et a l ., appellants

v

Davida J ohnson, et a l .

A. RELEVANT DOCKET ENTRIES

NR PROCEEDINGS

243 NOTICE of the State of Georgia’s Calling

of a Special Session of the G eneral

Assembly in Which to Enact a Remedial

Reapportionment Plan by State dfts Zell

Miller, Pierre Howard, Thomas Murphy,

Max Cleland.

251 ORDER setting hearing on redistricting

remedies at Augusta on 8/22/95 at 9 a.m.,

inviting original parties to submit sug

gestions not to exceed 25 pages no later

than 8/15/95, and informing parties that

all pending motions and m atters relating

to costs and atty fees will be considered

(signed by Judge Dudley H. Bowen Jr.),

copies served. [Entry date 08/03/95]

258 P L A IN T IF F S ’ SU B M ISSIO N on

Remedy Per Court Order of August 2,

1995 [edit date 08/14/95]

260 MOTION by A bram s in te rv en o rs for

Reconsideration of [251-1] order dtd 8/2/95

1

2

8/15/95

8/15/95

8/15/95

8/17/95

8/22/95

to allow interveners to submit remedies

for consideration, and to stay Ct.’s order of

8/2/95 to allow the Ga Gen Assembly to

complete congressional redistricting with

brief in support. [Entry date 08/15/95]

262 SUBMISSION of Defendant Thomas B.

Murphy in Response to the Court’s Invita

tion to Submit Suggestions as to Remedy.

267 MOTION by United States to Vacate [251-

1] order of 8/2/95 setting hearing on redis

tricting remedies at Augusta on 8/22/95 to

allow for a legislative remedy with brief in

support. [Entry date 08/16/95]

271 R E SPO N SE by dfts Miller, H ow ard,

Cleland to ct’s 8/2/95 [251-1] order setting

hearing on redistricting remedies. [Entry

date 08/16/95]

274 AMENDED BRIEF of Amici Curiae by

John Lewis and Newt Gingrich.

— Motion hearing held * * *. All pending

motions to intervene DENIED; to appear

amicus curiae GRANTED for the pu r

pose of m aking w ritte n subm issions,

D E N IE D for purpose of m aking oral

arguments or participating in open Court;

* * * [E n try date 09/28/95] [Edit date

09/29/95] Motion to dismiss Abrams inter-

venors is DENIED; Abrams intervenors’

motion to be allowed to submit proposed

redistricting remedies is GRANTED; all

motions to stay or vacate the order call

ing for today’s hearing DENIED; * * *

deadline Oct 15 set for new plan; * * *

3

8/31/95

9/1/95

9/1/95

9/5/95

9/13/95

9/15/95

9/28/95

10/11/95

10/13/95

Abrams intervenors not to participate [in

trial on 2d District]; Abrams intervenors’

proposal for plan of rem edies of 11th

Cong. District to be filed within 10 days;

Counsel to notify the Court in writing if

reapportionm ent plan not passed. * * *

[Entry date 09/28/95] [Edit date 09/29/95]

295 STATUS REPORT by Zell Miller, Pierre

How ard, Max Clelancl as to proposed

Congresional plan [Entry date 09/01/95]

296 PROPOSED REDISTRICTING PLANS

by Abrams Intervenors.

297 NOTICE by Thomas Murphy with respect

to legislative proceedings (status of special

session of Georgia General Assembly)

300 STATUS REPORT by Zell Miller, Pierre

Howard, Max Cleland regarding proposed

Congressional plan passed by Georgia

Senate on 8/31/95 [Entry date 09/07/95]

306 NOTICE by dft Thomas Murphy with

respect to legislative adjournment.

307 STATUS REPORT by Zell Miller, Pierre

Howard, Max Cleland [Entry date 09/18/95]

— Bench trial set for 10:00 10/30/95 before

Chief Judge Edenfield; C ircuit Judge

Edmondson and District Judge Bowren at

Augusta. [Entry date 10/02/95]

319 SUPPLEMENTAL DECLARATION of

Selwyn Carter

321 B R IEF on remedy by plffs [Entry date

10/25/95]

4

10/18/95

10/20/95

10/20/95

[sic]

10/27/95

10/27/95

10/27/95

10/27/95

10/30/95

[sic]

325 ORDER directing parties to subm it a

plan that makes the least chgs, in terms

of line drawing, bringing the 11th Dist.

into compliance w/US Constitution, and a

plan that makes the least chgs, in terms of

line drawing, in GAs present congressional

plan bringing the 11th and 2d Dists. into

compliance w/US Const; the parties are

instructed to confer regarding these plans;

signed by Judge James L. Edmondson);

copies served. [Entry date 10/25/95]

329 ORDER directing parties to submit plans

based on first plan that GA submitted to

Dept, of Justice for preclearance signed

by Judge Dudley H. Bowen Jr.); copies

served. [Entry date 10/25/95]

— Bench trial held as to 2d District; ruling

reserved; rem edy phase to continue on

10/31/95

343 SUBM ISSION of dfts Miller, Cleland,

and Howard in connection with the issue

of remedy.

344 NOTICE of filing minimum change plan

and brief by Abrams Intervenors

345 RESPO N SE/REM ED Y submission by

defendant Thomas Murphy to [329-1] order

and [325-1] order of 10/17 and 10/20/95.

348 BRIEF on remedy by United States

349 BRIEF on remedy by United States

10/[30]- Bench trial held; counsel argum ent and

5

31/95

11/9/95

11/16/95

11/22/95

11/22/95

11/22/95

11/22/95

11/30/95

evidence on remedy phase concluded; rul

ing of the Court reserved; the Court to

notify the parties if additional briefing

permitted. All evidence from 11th District

trial made a part of the record in these

proceedings. * * * [Entry date 11/01/95]

363 ORDER directing plffs’ counsel to submit

proposed plan to be known as plffs’ rem

edy 4X by 11/22/95, comments from each

p a rty not to exceed 12 pgs in leng th

(signed by Judge Dudley H. Bowen Jr.);

copies served. [Entry date 11/10/95]

368 ORDER inviting parties to submit addit

material to indicate chgs in racial composi

tion of DeKalb Co, GA, from the ‘90 census

to present ( signed by Judge Dudley H.

Bowen Jr. for 3- judge ct); copies served.

369 RESPONSE by United States to plffs’

[367-1] response to Ct’s order of 11/9/95,

plffs’ plans remdy 4X and 4X-R

370 RESPONSE/REPLY by Abrams inter-

venors to [367-1] plffs’ response to Ct

order of 11/9/95

371 RESPONSE/SUBMISSION of additional

dem ographic evidence by dfts Miller,

Howard and Cleland to [368-1] order of

11/16/95

372 R E PL Y /R ESPO N SE by amicus John

Lewis and amicus Newt Gingrich to plffs’

suggested [367-1] response/rem edy 4X

and 4XR [Entry date 11/27/95]

374 OBJECTION by S ta te dfts Miller,

6

12/1/95

12/1/95

12/1/95

12/6/95

12/7/95

12/8/95

12/8/95

Howard, Cleland to [369-1] response by US

Dept of Justice to plffs’ plans 4X and 4XR.

375 REPLY by plffs to [369-1] response by

United States, [370-1] response by Karen

Watson, William Gary Chambers Sr., G.

L. Avery, Lucious A bram s Jr., [372-1]

response by Newt Gingrich, John Lewis

to court order of November 9

376 RESPONSE memorandum by Abrams

intervenors to [371-1] submission of addi

tional dem ographic evidence by Max

Cleland, Pierre Howard, Zell Miller

377 ORDER that Georgia’s Second Congres

sional D istrict is unconstitutional in its

current composition; dfts are barred from

using it in future congressional elections;

(signed by Judge Jam es L. Edmondson

for three-judge court); copies served.

378 RESPONSE by United States to [374-1]

objection by Cleland, Howard and Miller,

and response to [375-1] response by plffs

to US subm ission of plan on 11/22/95

[Entry date 12/07/95]

379 OBJECTION by defendants Miller,

Howard, and Cleland to [372-1] reply/re-

sponse by Amici Curiae Gingrich and Lewis

to plffs’ suggested remedy 4X and 4XR

380 OBJECTION by plffs to submission of

affid of Donald Hill in [372-1] response by

Newt Gingrich and John Lewis

381 RESPONSE by United States to [371-1]

submission of additional demographic

information by Cleland, Howard, Miller

7

12/13/95

12/13/95

1/11/96

1/11/96

1/12/96

384 R E S P O N S E of am icus Lew is and

Gingrich to [379-1] objection by state dfts

C lei and, Howard, Miller to reply of amici

to plffs’ 4X and 4XR suggested remedy,

and response to [380-1] plffs’ objection to

amici’s submission of affid of Donald Hill

385 ORDER redraw ing Ga’s congressional

districting plan; directing tha t elections

for members of the House of Reps of the

Congress of the US from the St of GA be

conducted in accordance with the plan

appended to this Order as Appendices

“A” and “B”; motions terminated; signed

by three-judge court Edenfield, Bowen

and Edmondson; copies served. [E ntry

date 12/14/95]

397 N O TIC E OF A P PE A L by Lucious

Abrams Jr., G. L. Avery, William Gary

Chambers Sr., Karen Watson to Supreme

Court of the US from Order dtd 12/13/95,

oral ruling on 8/22/95, and Order of 1/8/96;

copies served. [385-1] order, [395-1] order

[Edit date 01/12/96]

398 MOTION by Lucious Abrams Jr., G. L.

Avery, William Gary Chambers Sr., Karen

Watson for a Stay pending appeal of Order

of Ct entered 12/13/95, permitting ‘96 pri

m ary and general elections to be held

under a redistricting plan that does not

violate Sec. 2 and 5 of Voting Rights, with

brief in support. [Edit date 01/16/96]

401 NOTICE OF APPEAL by dft-intervenor

United States to the Supreme Court of the

8

US from 12/13/95 order of USDC; copies

served. [385-1] order [Entry date 01/16/96]

1/26/96 407 ORDER denying Abrams In tervenors’

[398-1] motion for a Stay pending appeal

of Order of Ct entered 12/13/95 (signed

by Judge J. L. Edm ondson, Judge B.

Avant Edenfield and Judge Dudley H.

Bowen J r . ); copies served.

9

B.

TESTIMONY OF JOSEPH KATZ

[Excerpt from Trial Testimony, 5 T. Tr. p. 63,

line 5 to p. 86 line 1,]

Could you tell us, in a more conversational way, what

you have found. Essentially, to this point, you’ve been

asked to undermine Dr. Lichtman’s work, I think. So tell

us why it’s not worthy of your credit.

MR. WALBERT: I was just moving to the next point,

Your Honor.

HONORABLE JUDGE BOWEN: Tell me, in a more

conversational way, about his work, what you find trou

bling about it?

A (Dr. Katz) The thing I find troubling about it is

attempting to estimate election by election the actual

voting percentages of the white voters for the white

candidate and the black voters for the black candidate.

The data that he has available, that any of us have

availab le, is m erely th e re g is tra tio n d a ta for the

precinct, and the vote data for the precinct. And if we

have precincts that are racially mixed in that there’s a

high percentage of white and black voters, with only the

vote data and the registration data, it really isn’t possi

ble to dig out what the percentages of racial voting pat

terns are. And this is magnified when we had very few

precincts to work with.

HONORABLE JUDGE BOWEN: Could it be said

that any time you have a precinct in which there are two

races voting, that there is inevitably some extrapolation

in saying who voted and who did not?

A (Dr. Katz) Yes. And to come up with an estimate by

necessity, you have to make some additional assump

tions about the way the different races voted.

10

HONORABLE JUDGE BOWEN: You asked, or your

[sic] mentioned, some impossible results. Are those

results that are impossible because of mathematical cal

culation or because of the methodology used?

A (Dr. Katz) In these cases, i t ’s because of the

methodology used. The quadratic relationship that I

have demonstrated here, if you try to start fitting linear

equations to election data where your precincts fall, say,

under 40% black registered voters, then what you’re

getting in effect are observations that fall somewhat

along that line where turnout increases.

And if you then fit a line to that, that will simply shoot

the turnout further up, and it never has a chance to

adjust back down.

HONORABLE JU D G E BOWEN: Go ahead, Mr.

Walbert.

MR. WALBERT: If Your Honor doesn’t mind, if I

could make an inquiry of the Court, I just found out that

one of the copies I was working off of this report when

the p rin te r made it apparently left all the exhibits

out behind Tab Five, and if I might just to make sure

that —

HONORABLE JUDGE BOWEN: have - - -

MR. WALBERT: Do you have something?

HONORABLE JUDGE BOWEN: I have charts and

graphs on mine.

MR. W ALBERT: All rig h t. T h a t’s good. I ju s t

checked the original one that is marked as an exhibit in

evidence as well.

HONORABLE JUDGE BOWEN: Well, Dr. Katz, I

know you and Mr. Walbert have talked about this a num

ber of times, and that there are necessary terms of art,

11

but don’t hesitate to speak to us in a conversational way.

Q (Mr. Walbert) Now, Dr. Katz, I want to turn your

attention to the ultimate question here in this Court

about the likelihood of this kind of evidence, the likeli

hood of determining whether a black candidate would or

would not win in a district of a certain percentage of

black voters.

And let me ask you, before we turn to your calcula

tions and your charts, does Dr. Lichtman’s methodology

allow one to make those kinds of predictions or not?

A Not as methodology to the extent that he merely

estimates the racial polarization of voting estimates.

Q All right. Now have you used statistical techniques

and standard analytical techniques, Dr. Katz, to try to

make determinations of the likelihood of a black candi

date prevailing in a black-on-white election in congres

sional districts of various percentages, using the data

that Dr. Lichtman relied upon?

A Yes. That data and some additional data.

Q Okay. Now, are the final determination, before we

go back to them in detail, are those the charts that are

contained in your report, most of them anyhow, behind

Tab Five?

A Yes, they are.

Q Now, I’m going to pick out from here, if I could,

what I believe to be the first one of those charts behind

Tab Five, and put it up here.

Now using the data that Dr. Lichtman has, and he

relied upon, tell the Court what is depicted here by the

probability of the black candidate winning an election,

what this line and data plot would allow one to use this

chart for.

12

A Okay. What I’ve tried to represent here is a fre

quency distribution of the percentage of precincts in all

of the elections in the database, in which the black can

didate or black candidates had the majority of the vote.

Q Let me ju s t get you, what is, if you wanted to

determine, Dr. Katz, the likelihood of a black candidate

winning in a black and white race, can this chart, based

on the database here, be used for that purpose?

A Yes.

Q How would you do that?

A You would look at the racial composition of the

election. Say there’s 25 to 30% black registered voters,

and the estimate, or the probability that the black candi

date would win is the number approximately 20% in this

box here.

HONORABLE JUDGE BOWEN: Do you make any

assumption about the qualifications of the candidates

being equal?

A No. W hat I’m trying to do is just get an overall

probability without limiting it to —

HONORABLE JUDGE BOWEN: This is your, this is

your pro jection , not L ich tm an’s, you’re using the

Lichtman information. Is that right?

A I’m using the database from Dr. Lichtman, but I’m

not using it in the way he used it.

HONORABLE JUDGE BOWEN: All right. This is

your graph.

A Yes, sir, that’s correct.

HONORABLE JUDGE BOWEN: Okay.

Q (Mr. Walbert) Now, let me, I think, flip a couple

13

more charts back in your exhibit Tab Five there , I

believe this would be the one that is depicted there, Dr.

Katz.

In this graph, is it the same kind of presentation of

the graphical analysis that was on the previous one?

A Yes, it is. What’s changed in the database of elec

tions that I’ve used to conduct the analysis.

Q How has the database been changed in preparing

this particular one, Dr. Katz?

A In this graph, I enhanced the Lichtman database to

include the r e s t of th e p rec incts from th e 1990

Governor’s primary.

Q Let me stop you there, if I might. When you say

you enhanced it to include the rest of the precincts for

the 1990 Governor’s primary, what do you mean?

A Dr. Lichtman’s database did not contain all of the

precincts from the 1990 Governor’s election, primary

election.

Q Was there any apparent methodology to his select

ing ones here and there that you could determine at all?

A Not that I could determine.

Q Was Dr. L ich tm an’s da tabase , pu t aside the

Governor’s election, but the rest of the election, was

there any geographical limitation to it, or was it from

various places all over the State of Georgia?

A Mostly from all over Georgia, although in predomi

nantly white counties, I don’t think he had any election,

probably because there weren’t any black/white elec

tions.

Q All righ t. Now, his database, in fact, was ju s t

14

black/white elections; wasn’t it?

A That’s correct.

Q And was it all democratic primary elections except

for a couple of judicial ones?

A There were judicial elections, there was also a few

general elections. But I didn’t use those.

Q All right, sir. He testified in [h]is deposition that

primaries were the ones that were most important to

him, Dr. Katz?

A That’s my understanding from reading of his depo

sition.

Q Okay. Is that why you used the primaries when you

ju st said you did?

A Yes.

Q Okay. Now, you have also enhanced Dr. Lichtman’s

database you say, you just said, by using the rest of the

Governor’s race that he is a part of. Why is the 1992

Labor Commissioner and the 1992 Second and Eleventh

Congressional Districts primary elections in that data

base as well?

A Those are additional black/white elections in which

I can enhance the overall number of precincts to get

more precise estimates of the probabilities of the black

candidate prevailing.

Q Okay. Now, was the selection of those black/white

democratic primary elections consistent with the rules

that Dr. Lichtman has purported to you in the develop

ment of his database, Dr. Katz?

A Yes.

Q Were you making any independent political judg-

15

ments about the propriety of elections or just trying to

track his method, his selection?

A I was trying to track Dr. Lichtman’s selection.

Q Now —

HONORABLE JUDGE EDMONDSON: This is a lit

tle bit unusual, I guess, because we’re hearing a witness

whose purpose is to undercut the testimony of another

witness who we have not yet heard.

Explain to me why it is, what is the point that you and

the government of the United States are disagreeing

about that is pertinent to the outcome of this case.

I understand that there is a great deal of disagree

m ent betw een the S tate of Georgia and the United

States Government about elections in Georgia in gen

eral, and other kinds of elections, but, for our case, what

is the point of controversy that I should be focusing on

here?

MR. WALBERT: I think this, Your Honor, as far as 1

understand Dr. Lichtman’s testimony, when you start

going down this kind of a chart here, it is my under

standing that his opinions, as he has ventured before, is

that you, basically, blacks can’t win under some level—

and Fm not sure that he has ever quantified that specifi

cally, but I would expect that he would in this case on

his testimony—and what we are showing here is that

there is a whole lot different probability and pattern, if

you will, Judge, than I expect Dr. Lichtman to testify to.

I think he has basically got his concept about, if Fve

read him correctly in other case, is that there is kind of a

step function here. You’re in a safe d istric t a t some

point, and then it rapidly drops off into oblivion and it

stays down there. And I think that’s the critical question.

16

HONORABLE JUDGE EDMONDSON: I did under

stand from reading summaries of these reports that that

was where, that there was a difference of view on that

point.

What I do not understand is how that m atters to this

case, since whatever the percentage of voting-age black

vo ters are in the E leven th D istric t or the Second

District is, I gather, not now disputed, and what is the

significance of this pointing out that Georgia thinks one

thing and the United States Government thinks some

thing else when what is being done here is defending a

district that already exists?

MR. WALBERT: Well, to some extent, Your Honor, I

guess it’s in response to Your Honor’s instructions or

suggestions, and I think it is an appropriate one, that we

are the client of the law in this case in the highest and

best sense.

And I think it would be an inappropriate thing to

come into this Court and to defend this district to say

and to take the position that it is absolutely necessary

for [a] black person to have any chance of election that

this district being the percentage that it is.

And I th in k th e go v ern m en t’s ev idence of Dr.

Lichtman tends to be in that direction. I don’t think, the

State has not taken that position. And I think that what

we ought to try to do here is just—we have no idea how

this is going to turn out, quite frankly, when Dr. Katz

started doing it.

We just said, my request to Dr. Katz was: Is there a

way that you can statistically, with statistical quantita

tive methodology, come up with this. With an ideal of a

real, what’s the likelihood of winning. Because that’s the

bottom line.

17

HONORABLE JU DGE EDMONDSON: Am I to

understand that the chief reason that you’re litigating

this point in this case is to prevent th is Court from

including in its decision in this case some statement that

a State black district must have “X” percentage of vot

ers because you don’t want to have that precedent hang

ing over you in other litigation?

MR. WALBERT: I think tha t’s one, that has partly

stated one of the two reasons.

HONORABLE JUDGE EDMONDSON: What is the

other one?

MR. WALBERT: The other reason really is to show

to the Court what the truth is, if you will, the best that

we can, in terms of what percentages are appropriate to

the likelihood of black candidates winning in a district of

different percentages. To me, that is a very germane

point in this case, to our way of thinking.

And I think tha t the State—I guess that there’s—

Judge if I can focus in real closely, I do think that the

intervenors and the government take the position of

both se ts of in te rv en o rs th a t the S ta te was really

absolutely compelled as a matter of law under Section 2

to enact this district. We don’t take that position. I t’s a

fundamentally different position.

We take the position that the State having enacted it,

giving this type of chart here and these type of results,

it was reasonable w hat the S ta te did in its overall

action, and that the Constitution should not strike down

what the State did.

But we fundamentally disagree, Your Honor, on the

fact th a t th e S ta te was com pelled by e ith e r the

Fourteenth Amendment or Section 2 to do this.

18

HONORABLE JUDGE EDMONDSON: This ju st

goes to justifying the district if it is found to be bizarre

under Shaw; is that right?

MR. WALBERT: Yes, I think—yes, I think tha t’s a

fair statement, yes sir.

HONORABLE JU DGE EDMONDSON: I under

stand this much better now.

MR. WALBERT: I appreciate it. Thank you.

Q (Mr. Walbert) I think we’ve probably covered that

exhibit as much as need be, Dr. Katz. Let me ask you, if

I might, one last point which goes to the first reason

here, and that is this:

Did Dr. Lichtman also include in his database, in his

analysis, some of the judicial elections in Georgia, such

as some precincts from the R obert Benham race in

1984?

A Yes, he did.

Q Have you made an assessment, Dr. Katz, of all of

the database on judicial elections in his database, with

all of the precincts, with all of the state-wide precincts

for Judge, now Justice, Benham, and Justice Sears-

Collins, in all of the four state-wide elections?

A All four state-wide, yes, I have.

Q All right.

A And one of these exhibits shows the probability of

the black candidate winning the election if we throw in

these additional elections.

Q Now, you used the judicial elections on the local

level that Dr. Lichtman had as well; didn’t you?

A Yes.

19

Q Did you m ake a finding or d e te rm in a tio n of

whether the judicial elections are, in fact, sufficiently

similar in their characteristics statistically, to be a reli

able indicator in this kind of race, or are they materially

different?

A I found that statistically, the judicial elections are

materially different.

Q Would it, from a statistical point of view, be inap

propriate in your judgm ent to rely on the one group

going back and forth from congressional to judicial or

judicial to non-judicial elections?

A Inappropriate in the sense that they seem to be

measuring different kinds of elections.

MR. WALBERT: We have no further questions of this

witness, Your Honor.

HONORABLE JUDGE BOWEN: Dr. Katz, just one

other thing. This graph that you have here, do you pre

sent this as a projection of what would, or what might

happen, or simply a report of what has happened in the

past?

A (Dr. Katz) I presented it as what might happen,

since this was the only empirical evidence that I can col

lect to try and predict the voting pattern in the future.

HONORABLE JUDGE BOWEN: There is no rela

tionship, as far as you know, to the qualifications of the

candidate? It is strictly race-based?

A (Dr. Katz) Yes.

HONORABLE JU D G E BOW EN: All rig h t. Ms.

Murphy, you may have a question or two.

MS. MURPHY: I have a few minutes of examination

20

for Dr. Katz. Fm wondering if the Court would like to

take it’s morning break now, before I start?

HONORABLE JUDGE EDMONDSON: How much

time is it going to take?

MS. MURPHY: I expect it will take about tw enty

minutes.

HONORABLE JUDGE EDMONDSON: W hat do

you think, Judge Bowen? We would like to take the

morning recess about 11:00, which gives you about sev

enteen minutes. Let’s see if you can do your twenty in

seventeen.

MS. MURPHY: Well, I hope you will give me that

extra minute or two if I need it.

HONORABLE JUDGE EDMONDSON: Well, keep

in mind that speed is the essence of war.

MS. MURPHY: I hate to think we’re actually at war

here.

HONORABLE JUDGE BOWEN: Go.

CROSS EXAM IN ATIO N B Y

MS. MURPHY:

Q Dr. Katz, I’m Donna Murphy, good morning.

A Good morning.

Q And, as you know, I represent the United States.

You’ve read Dr. Lichtman’s entire report in this case; is

that correct?

A Yes.

Q And the analysis that you were describing that is

21

set forth on pages 1 to 18 of your report, that analysis is

based only on the data that underlies the appendices of

Dr. Lichtman’s report; is that correct?

A That’s correct.

Q So, Dr. Lichtman did, in fact, analyze the elections

you were talking about a few minutes ago, the 1990

gubernatorial primary, the 1990, the 1992 labor commis

sioner primary, and the 1992 congressional election in

Districts Eleven and Two, in the table in the body of this

report.

A Yes, but they were just partial, it wasn’t the com

plete election.

Q B ut you analyzed them for th e E lev en th

Congressional and the Second Congressional Districts?

A Yes.

Q And so, you[r] analysis of the statistical methodol

ogy and whatever data issues that you have would only

go to the appendices of Dr. Lichtman’s report. Is that

correct?

A That’s correct.

Q With regard to those appendices, in Dr. Lichtman’s

report, he doesn’t rely on any one election in those

appendices to draw a conclusion; does he?

A I don’t know what he relies on.

Q Well, you’ve read his report. Does he purport to

rely on any particular election percentages?

A Not only does he not rely on any particular one, he

never provides an overall assessm ent of how all the

results for all the elections fit together in coming up

with an estimate, and overall estimate.

22

Q So he basically uses those as sort of a background

to show some, over 300 elections I believe, what his

assessment of racial voting patterns is in Georgia over a

wide number of elections. Is that correct?

A That’s my understanding as to his intentions, yes.

Q And, have the pages tha t you have attached to

Tabs Three and Four of your report, from Exhibits

“168” and “169”, you didn’t pull those pages out, you

pulled those pages out to illustrate the problems that

you found; is that correct?

A That’s correct.

Q So, these are going to be the ones that show what

the problems might be, not necessarily representative of

the typical page in your report of Dr. Lichtman’s analysis.

A As part of my report, I also give overall summary

statistics to the extent to which these problems existed

in this set of elections.

Q But my question was with regard to these particu

lar pages that you pulled out, those are designed to illus

trate the problem; is that correct?

A Yes.

Q Now with regard to your analysis on pages one

through, I believe it is 18 of your report, it basically

boils down to a critique of the use of double ecological

regression analysis to analyze racial voting patterns;

isn’t that correct?

A I’m not sure I understand the reference that you

gave me. Page 18?

Q Page one through 18, I’ve been talking about this

whole first section —

23

A Oh, one through 18.

Q of your report.

A Yes.

Q Are you familiar with the Supreme Court opinion

of Thornburg v. Cringles!

A I read that opinion, it’s been a while, yes.

Q And you’re aware tha t in tha t case, the Court

relies on, in fact, double ecological regression analysis

estimates of voting behavior in drawing its conclusions

about racially polarized voting.

A I don’t recall whether they relied on double ecolog

ical regression estimates, but I think they did rely on

some ecological regression estimate.

Q And those ecological regression estim ates were

performed by Dr. Bernard Grofman; is that right?

A I’m not sure.

Q You don’t have any reason to dispute that, though?

A No.

Q Are you aware of any differences betw een the

m ethodology th a t Dr. L ichtm an em ploys and th e

methodology that was employed by the plaintiffs’ expert

in the Thornburg v. Gingles case?

A I’m not familiar with the methodology employed in

the Thornburg v. Gingles case, so I can’t, you know, tell

you if there is any differences.

Q So if I —

A But I also don’t know the extent to which that data

had more precincts more amenable to double ecological

regression.

24

Q But if I would represent to you that Dr. Lichtman

employed the same analysis as Dr. Grofman did in the

Thornburg v. Gingles case, you wouldn’t have any rea

son to dispute me on that, would you?

MR. WALBERT: Objection as to the form of tha t

question.

MR. PARKS: The plaintiffs join in that. I don’t want

to hear any objections, but it’s —

MR. WALBERT: But he has ju s t testified th a t he

didn’t know what happened, and for her to ju st argue

the case and say, “you can’t then tell me that — ”

HONORABLE JUDGE BOWEN: “Well, that might

be argumentative, and we’ll save that.

Q (Ms. Murphy) Are you aware, Dr. Katz, that in the

case of Garza v. County o f Los Angeles, the type of cri

tique that you’re presenting here was presented exten

sively by a number of different statistical experts con

cerning analysis performed by both Dr. Lichtman and

Dr. Bernard Grofman?

A Yes, but your, you have to keep in mind that the

election data makes a big difference as to the appropri

ateness of methodology —

Q I am saying —

A The methodology, let me finish, please.

Q I’m sorry.

A A methodology by itself isn’t usable for every con

ceivable data set. Just to say that somebody used eco

logical regression in one circumstance and it turned out

to be a reasonable methodology, doesn’t make it reason

able in every circumstance.

25

Q So you’re saying that the Court in the Garza case

rejected the kind of criticism that you’re offering that

that wouldn’t necessarily lead to the same conclusion

concerning your critique of Dr. Lichtman’s analysis.

A Not necessarily. The data is totally different.

Q And are you aware that the Garza Court did reject

those critiques?

A I’m not—I haven’t read the Garza opinion, and I

don’t know what the Court did.

Q Now, after, on page, I believe, 20 of your report,

you get into a som ewhat different area, where you

employ your own, if I can call it, hom ogen[e]ous

precinct analysis to try and estimate racial voting pat

terns; is that correct?

A Average racial voting patterns.

Q Average racial voting patterns.

A Yes.

Q And if I understood your earlier testimony, you put

three different sets of estimates for three different data

bases; is that correct?

A Is this on page 20 and 21?

Q Pages 20 through 21.

A Yes, I do.

Q And if I understood your earlier testimony, I take

it th a t the th ird e s tim ate th a t you rep o rt, which

includes judicial elections, you would consider to not be

very relevant or germane to this case. Is that correct?

A Well, in terms of relevance or germane to this case,

I don’t have an opinion on that. I t’s there to show that

26

when you throw in the additional judicial elections, that

there is a substantial increase in the average percent

vote of whites voting for the black candidate.

Q I apologize. I th ink my question was poorly

phrased. In fact, you found a different pattern in the

judicial, the state-wide judicial election that you ana

lyzed in terms of voting patterns; is that correct?

A Different from what?

Q Different from the pattern you found in, say, the

number two, all the data you analyzed in the number

two estimate.

A Yes.

Q So which would you consider if you were trying to

estimate voting behavior in a congressional election,

congressional primary election. Which of these three

sets of estimates that you report would you consider the

most, the best estimate?

A Following Dr. Lichtman’s political assumptions? Or

do you want me to make my own assumptions, what I

think would be the best thing to use.

Q Well, what assumptions would you make? I mean,

your not a political scientist, are you?

A No.

Q Okay, so what assumptions would you make? Let’s

take a step backwards.

A Well, from a statistical perspective, I would want

Congressional elections to estimate the degree of racial

polarized voting in future Congressional elections, and

other elections that are related to that.

Q So I’m asking you of these three sets of estimates

27

you report here, which would you consider the best and

the most reliable. I realize they’re not perfect, I under

stand your testimony.

A Okay. I would go with number two.

Q And based on the set of estimates in number two,

would you say that there are substantially or signifi

cantly different voting patterns among black and white

voters according to these estimates?

A Yes, in that the competence interval surrounding

these numbers are about, plus or minus, 1%.

Q And do you have an opinion on w hether or not

these numbers would be indicative of racially polarized

voting? Do you have an opinion?

I don’t know if you’re, if you feel comfortable giving

an opinion since your [s?'c] a statistical person, not a

political scientist or a political analyst.

A To the degree of whether it’s legally significant,

o r - - -

Q No, just, if you understand the term racially polar

ized voting do you have an opinion on these numbers?

A Well, my opinion is that there is a 95% competence

interval to the average percent white voting for black

candidates that goes from 27% to 29%. So, to the degree

that whites tend to vote for white candidates in the

range of the approximately 71 to 73%, that’s, there is a

tendency for white voters to vote for white candidates.

Q Maybe I should ask the question a little differently.

Rather than getting into a term that obviously has some

legal implications, these numbers indicate a fair degree

of cohesion among white voters and cohesion among

black voters; is that correct? Can you agree with that?

28

A By cohesion, I think that’s a legal term, too.

Q Oh, is it? Voting similarities? Can we agree on a

term?

A W hites tend to vote for w hite candidates and

blacks tend to vote for black candidates according to the

results of number two.

Q Thank you. I have a question—I’m not sure if you

still have these charts in front of you. This exhibit which

you’re still looking at here, Plaintiffs’ “174”, and you

indicated that this is a chart indicating the probability of

a black candidate getting elected where the percentage

of black voters fell at certain intervals; is that correct?

A Yes.

Q And this particular chart we’re looking at is the,

includes the 1990 gubernatorial and 1992 labor commis

sioner, and the 1992 Second and Eleventh Congressional

D istrict races, as well as the many smaller elections

included in Dr. Lichtman’s data; is that right?

A Yes.

Q According to your estimates as based on this chart,

a t approxim ately—will you agree w ith me th a t the

probability of a black candidate winning doesn’t go

above 50% until the percentage of black registered vot

ers reaches approximately 50%?

A Yes. In the range from 45 to 50, that percentage is

a 46% probability, and from 50 to 55%, that’s a 62% prob

ability. It’s about 50%.

Q And, I’m now showing you Defendants’ Exhibit

“172”, which is a similar chart that you did based only on

what you termed “the Lichtman database,” is that cor

rect?

29

A That’s correct.

Q And if I asked the same question, at what point

does the probability of a black candidate winning go

above 50%, what would your response be? Is it approxi

mately 50%?

A. Let me check my numbers to be sure. Yes, it’s

approximately 50%. It’s 44% in the range from 45 to 50%

black registered voters, and the probability is 55% in

the range from 50 to 55%.

30

C. [CORRECTED] REPORT OF

DR. JOSEPH L. KATZ

[State’s Exh. 170, at 14 (Part II)-22]

HI. A N A L Y SIS OF THE R E L IA B IL IT Y OF THE

E S T IM A T IO N OF R A C IA L VO TING P E R

CENTAGES D E TE R M IN ED B Y DR. LICHT-

MAN.

I have analyzed Dr. Lichtman’s primary election data

base that was provided on computer diskettes by the

D epartm ent of Justice and Dr. Lichtman. The data

included on these diskettes encompass the great major

ity of those elections for which racially polarized voting

estimates are given in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2 of Dr.

Lichtman’s report. I find that the potential difficulties

with double ecological regression racial voting esti

mates, enumerated in the previous section, are present,

to varying degrees, in the analysis of these elections.

Approximately 50% of the elections in the Lichtman

database have nine or fewer precincts. Approximately

38% of the elections have one or more impossible values

for the four turnout estimates. Approximately 32% of

the elections have registration data taken from a year

that is different from the year of the election.

The rac ia l po lariza tion vo ting e s tim a te s in Dr.

Lichtman’s report are single numbers or “point esti

mates” derived as ratios from four estimates of white

and black voter turnout for white and black candidates

in an election, taken from two separate “least squares”

lines. In the context of statistical regression methodol-

ogy, each of the four voter turnout estimates is subject

to some degree of variation from the “tru e ” vo ter

31

tu rn o u t percen tages th a t are sough t.4 I have con

structed 95% confidence intervals for each of the four

voter turnout estimates to assess this variation.5 These

confidence intervals, in turn, assist in evaluating the reli

ability of the racial vote estimates derived from double

ecological regression. My detailed analyses of these

elections, individually, are contained in State Exhibit 166.

(Illustrative excerpts from this exhibit that pertain to

several of the Lichtman elections follow Tab 3)

A brief summary of the results of my confidence inter

val determinations are the following:

(1) In fully half of the elections in the Lichtm an

database, the length of the 95% confident interval

for the white turnout for white candidates was

26% or greater.

(2) In half of the elections, the length of the confidence

intervals for white turnout for black candidates

was 18% or greater.

4H ypo the tica lly , th is p a r tic u la r an a ly s is w ould n o t ap p ly in a case

w h e r e e v e r y p r e c in c t in a n e le c t io n w a s 100% h o m o g e n e o u s ,

w h ite o r b lack , b ec au se in th a t in s tan ce double ecological re g re ss io n

p ro d u c e s e x a c t r a c ia l v o te p e r c e n ta g e s . In th e L ic h tm a n d a ta ,

w h ich is co m p rised e n tire ly of p re c in c ts th a t a r e a t le a s t to som e

e x te n t m ixed , th e re is n e c e ssa rily som e d e g re e o f s ta t is tic a l v a r i

ab ility in v o te r tu rn o u t e s tim a te s .

5I h a v e u sed 95 p e rc e n t confidence in te rv a ls , w h ich m ean s th a t ,

b a se d on th e e lec tio n d a ta ana lyzed , th e re is a .95 p ro b a b ility th a t

th e “t r u e ” v o te r tu r n o u t p e rc e n ta g e fo r a n e le c tio n is co n ta in e d

so m ew h e re in th e in te rv a l. T he 95% level is ty p ica lly u sed in s ta t is

tica l ana ly sis .

T h e s ta t is t ic a l r e g re s s io n m eth o d o lo g y fo r c o n s tru c tin g confi

dence in te rv a ls is n o t a p e rfe c t a n sw e r to th e v a r ia b ili ty issu e w ith

ecological re g re s s io n e s tim a te s , b u t i t is th e m o st a p p ro p ria te m ea

s u re ava ilab le .

32

(3) In half of the elections, the length of the confidence

interval for black turnout for black candidates was

23% or greater.

(4) In half of the elections, the length of the confidence

interval for black turnout for white candidates was

34% or greater.

The sensitivity of the racial vote percentages to the

lengths of these 95% confidence intervals is demon

strated by the following example. Suppose that, in a cer

tain election, double ecological regression predicts a 15%

turnout of whites for the white candidate(s) and a 5%

turnout of whites for the black candidate(s). Therefore,

the estimated percentage of white voters voting for the

white candidate(s) is 15/(15 + 5) or 75%, and the esti

mated percentage of white voters voting for the black

candidate(s) is 25%.

Using the above-stated median percentage for our

example indicates that there is a 95% chance that the

“tru e ” percen tage of w hite reg is te red vo ters who

turned out for the white candidate is between 2% and

28%. Similarly, there is a 95% chance that the “tru e”

white turnout for the black candidate(s) is between -4%

and 14%, even though a negative result is a practical

impossibility.

Different selections of voter turnout from the two

95% confidence intervals can generate significantly dif

ferent white vote percentages. For example, if 6% of the

white registered voters turn out for the white candi

date^) and 14% for the black candidate(s), then 20% of

the white voters still turn out to vote, as in our initial

estimate. However, only 30% of the white voters are

then predicted to have voted for the white candidate(s),

compared to the original 75%.

I also produced 95% confidence intervals, under the

33

statistical regression methodology, for racial vote esti

mates based upon single ecological regression for a sub

set of elections from the Lichtman database.6 For the

most part, these confidence intervals are fairly wide. My

detailed analyses of these elections, individually, are

contained in S ta te E xhib it 165. (Some illu stra tiv e

excerpts from this exhibit that pertain to several of the

Lichtman elections follow Tab 4)

As part of his results, Dr. Lichtman reports squared

correlation coefficients, or R2 values. Although Dr.

Lichtman estim ates racial voting behavior based on

double ecological regressions, the R2 reported by Dr.

Lichtman pertains to values he has calculated for single

ecological regression. More significantly, R2 values do

not m easure the accuracy or degree of confidence of

racial voting estim ates derived from single or double

ecological reg ress io n .7 Thus, a high R2 value says

nothing about the statistical confidence level applicable

to those voting estimates.

I conclude that Dr. Lichtman’s small election by small

election analyses do not provide a meaningful and reli

able description of racial voting behavior in Georgia.

IV. A N A L Y SIS OF RAC IAL VOTING P E R C E N T

AGES OVER M A N Y GEORGIA ELECTIONS.

While Dr. Lichtman’s analyses do not lend themselves

to a meaningful description of racial voting behavior in

6T h is s u b s e t w a s t h e p o r t i o n o f h is d a t a p r o v id e d b y t h e

D e p a r tm e n t o f J u s tic e in an e a r lie r d isk e tte .

7F o r e x m p le , i f a ll th e p re c in c ts in th e e le c t io n w e r e 100%

racia lly hom ogenous, s in g le and double ecological re g re s s io n w ould

p roduce ex a c t ra c ia l v o tin g p e rc e n ta g e s re g a rd le s s o f th e slope of

th e le a s t s q u a re s line. B u t th e R 2 v a lu e could b e a n y w h e re from 0

to 1.0

34

Georgia generally, that is not to say that this data is

utterly irrelevant to that issue. A better methodology

using this data would be to measure overall racial voting

behavior by estimating the average racial voting per

centages over a representative set of Georgia elections.

My method differs from that of Dr. Lichtman and Dr.

Weber in that I do not estimate racial voting patterns

in individual elections, but seek to examine average vot

ing patterns over a number of elections.8

Moreover, because of the methodological problems

inherent in double ecological regression analysis, and

particularly because of the incorrect assumption that

voter turnout is a linear function, a methodologically

sound way to determine estimates of racial voting pat

terns is to look at the homogeneous precincts—i.e.,

those 100 percent one race or the other, or nearly so.9

To determine overall voting behavior, the results for all

of the homogenous precincts for the various elections

8W hile th e se m ethodo log ies can e lim ina te som e o f th e s ta tis tic a l

p ro b le m s of Dr. L ic h tm a n ’s an a ly s is , th e y s ti ll do r e q u ir e c e r ta in

a s su m p tio n s a b o u t v o tin g behav io r. F o r ex a m p le , a h om ogeneous

p re c in c t an a ly s is r e g u ir e s th e a s su m p tio n th a t w h ite v o te r s in a

hom ogenous w h ite p re c in c t v o te th e sam e as w h ite v o te rs in a non-

h o m o g en o u s p re c in c t, an d th e sam e th in g fo r b la c k v o te r s . T h a t

m ay o r m ay n o t b e t ru e , and i t is s ta tis tic a lly im possib le to d e te r

m ine w h e th e r o r n o t i t is tru e .

9In th is ana ly sis , I h av e u sed only th o se p re c in c ts th a t a re 95%-

100% one race o r th e o ther. Dr. L ich tm an does do a s im ila r k ind of

h om ogenous p re c in c t ana ly sis , b u t h is d e te rm in a tio n s c o n sid e r as

“h o m o g e n e o u s” a n y p re c in c t th a t is b e tw e e n 80% an d 100% one

r a c e o r t h e o th e r . C a ll in g p re c in c ts “h o m o g e n e o u s ” w h e n th e y

h a v e such a la rg e d e g re e o f h e te ro g e n e ity su b s ta n tia lly a ffec ts th e

re lia b ility and accu racy o f th e e s tim a te s d e r iv e d .

35

are averaged together, weighted by the number of vot

ers in the precincts.10

I have also made these determinations of racial voting

patterns using homogenous precinct analysis for several

different data sets. F irst is the Lichtman data set, again

utilizing all of those elections of his that were provided to

me by Dr. Lichtman and the Department of Justice. I

have also made the same determinations for an election

data set consisting of those in Dr. Lichtman’s data set

plus other major recent elections involving black-white

candidates in Georgia—the Governor’s primary election

in 1990 (which involved Andrew Young; only a portion of

the precincts from this election were included in Dr.

Lichtman’s data); the 1992 Labor Commissioner primary

(which included black candidate A1 Scott); and the sec

ond and eleventh congressional primary races from 1992.

Finally, I have made the same calculations for the

most comprehensive available database of Georgia elec

tions with black-white opponents. This includes the

Lichtman data, all of the four large races mentioned

above, and all four state-wide black-white judicial races

(again, portions of one of these races were already

included in Dr. Lichtman’s data).

The results are as follows:

i°“W eig h tin g ” g iv es a p ro p o rtio n a lly g r e a te r w e ig h t to a p re c in c t

w ith m o re v o te rs th a n one w ith less. T his avo id s a n o th e r p ro b lem

in h e re n t in th e p re s e n ta tio n b y Dr. L ich tm an w h ich m ak es no d is

t in c t io n b e tw e e n a n e le c tio n th a t m a y h a v e o c c u r re d in a sm all

co u n ty o r d is tr ic t w ith a few v o te rs an d one th a t m ay h av e o ccu rred

from a n elec tion in a c o u n ty o r a d is tr ic t w ith fa r m o re v o te rs .

LICH TM AN ELECTION DATA (No. 1)

Average Percent

Whites Voting

for Black Candidates

22%

Average Percent

Blacks Voting For

White Candidates

23%

36

LICH TM AN ELECTIONS PLUS R E S T OF

GOVERNOR, LABOR A N D CONGRESS (No. 2)

Average Percent Averace Percent

Whites Voting Blacks Voting For

for Black Candidates White Candidates

28% 20%

LICH TM AN ELECTIONS PLUS R E ST OF

GOVERNOR LABOR, CONGRESS AND JUDICIAL

(No. 3)

Average Percent Average Percent

Whites Voting Blacks Voting For

for Black Candidates White Candidates

38% 20%

V. A N A N A L Y S IS OF TH E L IK E L IH O O D OF

B LA C K C A N D ID A TE S P R E V A IL IN G OVER

W H I T E O P P O N E N T S I N D I S T R I C T S OF

VARYIN G P ER C E N TA G E S OF B LA C K VOT

ERS.

I have been asked to perform a statistical analysis, if

possible, that predicts the likelihood of black candidates

prevailing over white opponents, based on the existing

data, as a function of the racial percentage of the elec

tion district. Neither Dr. Lichtman nor Dr. Weber have

done such an analysis.

F irst, I determ ined the frequency distribution for

black candidates winning individual precincts in the

available data sets as a function of the racial composition

of those precincts. From that frequency distribution, I

then calculated the probabilities of black candidates

winning in entire election districts as a function of the

percentage of black registered voters in the district.

These results were graphically plotted for several data

sets. In making these plots, I have used intervals of five

37

percent (for example, a range of 40 percent to 45 per

cent, and then 45 percent to 50 percent, of black regis

tered voters). The results of these probability analyses

are contained after Tab 5.

Generally speaking, the results of this analysis indi

cate that black candidates in the several election data

bases have relatively low chances of winning against

white opponents when the percentage of black regis

tered voters is relatively small. However, the chances of

black success are by no means zero even when the per

centage of black registered voters in a district may be as

low as 25 or 30 percent. Then, the likelihood of a black

candidate winning the election and defeating his white

opponents increases steadily until the percent of black

re g is te re d v o te rs becom es a sign ifican t m ajo rity

(approximately 55-60 percent, although the num ber

varies depending on the specific election database). The

likelihood of an African-American candidate winning

plateaus in the 70-80 percent range, and then increases

slowly as the percentage of black reg istered voters

increases on up to 100 percent.

38

D R . L IC H T M A N ’S P R IM A R Y E L E C T IO N D A T A B A SE

(R E C E IV E D 06/94)

B A L D W IN C O U N T Y

C O U N T Y C O M M IS S IO N E R (1) 1988

IN IT IA L E L E C T IO N

V O T E R R E G IS T R A T IO N , 1988

W H IT E V O T E R B L A C K V O T E R

R E G IS T R A T IO N , 5506 R E G IS T R A T IO N , 2241

5 DATA P O IN T S

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

W H IT E V O T E S C A S T F O R

W H IT E C A N D ID A T E (S ): 41%

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

B L A C K V O T E S C A S T F O R

B L A C K C A N D ID A T E (S ): 16%

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N

(R -SQ )

W H IT E : 0.0122

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F

S T A T IS T IC A L

S IG N IF IC A N C E

W H IT E : 0.8595

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N

(R-SQ )

B L A C K : 0.0212

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F

S T A T IS T IC A L

S IG N IF IC A N C E

B L A C K : 0.8153

ESTIM ATED TURNOUT

W H IT E B L A C K

V O T E R S V O T E R S TO TA L

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) 3.5% (193) 6.6% (149) 341

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) 5.0% (276) 1.3% (29) 305

E S T IM A T E D TO TA L

T U R N O U T 8.5% (469) 7.9% (178) 646

39

TURNOUT CONFIDENCE INTERVALS

W H IT E V O T E R S B L A C K V O T E R S

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) -26% TO 33% -34% TO 47%

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) -21% TO 31% -35% TO 38%

D R . L IC H T M A N ’S P R IM A R Y E L E C T IO N D A T A B A SE

(R E C E IV E D 06/94)

B R A N T L E Y C O U N T Y

C O U N T Y C O M M IS S IO N E R (3) 1980

R U N O F F E L E C T IO N

V O T E R R E G IS T R A T IO N , 1980

W H IT E V O T E R B L A C K V O T E R

R E G IS T R A T IO N , 4549 R E G IS T R A T IO N , 294

9 DATA P O IN T S

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

W H IT E V O T E S C A S T F O R B L A C K V O T E S C A S T F O R

W H IT E C A N D ID A T E (S ): 56% B L A C K C A N D ID A T E (S ): 453%

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N

(R -SQ )

W H IT E : 0.2912

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F

S T A T IS T IC A L

S IG N IF IC A N C E

W H IT E : 0.1337

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N

(R -SQ )

B L A C K : 0.1024

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F

S T A T IS T IC A L

S IG N IF IC A N C E

B L A C K : 0.4013

ESTIM ATED TURNOUT

W H IT E B L A C K

V O T E R S V O T E R S TO TA L

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) 41.7% (1896) -69.1% (-203) 1693

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) 32.5% (1479) 88.7% (261) 1740

E S T IM A T E D TO TA L

T U R N O U T 74.2% (3375) 19.6% (58) 3433

40

TURNOUT CONFIDENCE INTERVALS

W H IT E V O T E R S B L A C K V O T E R S

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) 12% TO 71% -228% TO 89%

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) 4% TO 61% -64% TO 241%

D R . L IC H T M A N ’S P R IM A R Y E L E C T IO N D A TA B A SE

(R E C E IV E D 06/94)

B R O O K S C O U N T Y

S C H O O L B O A R D 1986

R U N O F F E L E C T IO N

V O T E R R E G IS T R A T IO N , 1986

W H IT E V O T E R

R E G IS T R A T IO N , 4120

11 DATA P O IN T S

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

W H IT E V O T E S C A S T F O R

W H IT E C A N D ID A T E (S):

152%

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N

(R -SQ )

W H IT E : 0.104

B L A C K V O T E R

R E G IS T R A T IO N , 2272

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

B L A C K V O T E S C A S T F O R

B L A C K C A N D ID A T E (S ):

66%

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N

(R -SQ )

B L A C K : 0.8814

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F

S T A T IS T IC A L

S IG N IF IC A N C E

W H IT E : 0.3334

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F

S T A T IS T IC A L

S IG N IF IC A N C E

B L A C K : 0

41

ESTIM ATED TURNOUT

W H IT E B L A C K

V O T E R S V O T E R S TO TA L

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) 9.6% (397) 23.2% (526) 923

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) -3.3% (-136) 44.4% (1010) 874

E S T IM A T E D TO TA L

T U R N O U T 6.3% (261) 67.6% (1536) 1797

TURNOUT CONFIDENCE INTERVALS

W H IT E V O T E R S B L A C K V O T E R S

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) -8% TO 27% -1% TO 47%

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) -11% T O 5% 34% TO 55%

D R . L IC H T M A N ’S P R IM A R Y E L E C T IO N D A T A B A SE

(R E C E IV E D 06/94)

C O L U M B IA C O U N T Y

C O U N T Y C O M M IS S IO N E R (5) 1984

R U N O F F E L E C T IO N

V O T E R R E G IS T R A T IO N , 1983

W H IT E V O T E R B L A C K V O T E R

R E G IS T R A T IO N , 12805 R E G IS T R A T IO N , 1843

12 DA TA P O IN T S

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

W H IT E V O T E S C A S T F O R

W H IT E C A N D ID A T E (S ):

59%

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N

(R -SQ )

W H IT E : 0.2051

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

B L A C K V O T E S C A S T F O R

B L A C K C A N D ID A T E (S ):

70%

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N

(R-SQ )

B L A C K : 0.6216

42

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F

S T A T IS T IC A L S T A T IS T IC A L

S IG N IF IC A N C E S IG N IF IC A N C E

W H IT E : 0.1393 B L A C K 0.0023

ESTIM ATED TURNOUT

W H IT E B L A C K

V O T E R S V O T E R S TO TA L

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) 15.6% (2001) 26.5% (489) 2491

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) 11.0% (1403) 62.3% (1149) 2552

E S T IM A T E D TO TA L

T U R N O U T 26.6% (3405) 88.9% (1638) 5043

TURNOUT CONFIDENCE INTERVALS

W H IT E V O T E R S B L A C K V O T E R S

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) 7% TO 24% 13% TO 40%

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) -4% TO 26% 38% TO 87%

D R . L IC H T M A N ’S P R IM A R Y E L E C T IO N D A TA B A SE

(R E C E IV E D 06/94)

C O W E T A JU D IC IA L C IR C U IT

P R E S ID E N T 1988

P R E S ID E N T IA L P R E F E R E N C E E L E C T IO N

V O T E R R E G IS T R A T IO N , 1986

W H IT E V O T E R B L A C K V O T E R

R E G IS T R A T IO N , 5948 R E G IS T R A T IO N , 3149

12 DATA P O IN T S

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

W H IT E V O T E S C A S T F O R B L A C K V O T E S C A S T F O R

W H IT E C A N D ID A T E (S ): B L A C K C A N D ID A T E (S ):

103% 101%

43

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N

(R-SQ )

W H IT E : 0.4238

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F

S T A T IS T IC A L

S IG N IF IC A N C E

W H IT E : 0.0219

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N

(R -SQ )

B L A C K : 0.9119

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F

S T A T IS T IC A L

S IG N IF IC A N C E

B L A C K : 0

ESTIM ATED TURNOUT

W H IT E B L A C K

V O T E R S V O T E R S TO TA L

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) 23.3% (1386) -0.3% (-8) 1378

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) -0.7% (-39) 42.9% (1351) 1312

E S T IM A T E D TO TA L

T U R N O U T 22.6% (1347) 42.6% (1343) 2690

TURNOUT CONFIDENCE INTERVALS

W H IT E V O T E R S B L A C K V O T E R S

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) 11% TO 36% -16% TO 15%

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) -7% TO 5% 35% TO 50%

D R . L IC H T M A N ’S P R IM A R Y E L E C T IO N D A T A B A SE

(R E C E IV E D 06/94)

F R A N K L IN C O U N T Y

B O A R D O F E D U C A T IO N 1984

R U N O F F E L E C T IO N

V O T E R R E G IS T R A T IO N , 1984

W H IT E V O T E R B L A C K V O T E R

R E G IS T R A T IO N , 7793 R E G IS T R A T IO N , 429

13 DATA P O IN T S

44

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

W H IT E V O T E S C A S T F O R

W H IT E C A N D ID A T E (S ):

49%

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

B L A C K V O T E S C A S T F O R

B L A C K C A N D ID A T E (S ):

117%

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N

(R-SQ) (R-SQ )

W H IT E : 0.0315 B L A C K : 0.2361

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F

S T A T IS T IC A L S T A T IS T IC A L

S IG N IF IC A N C E S IG N IF IC A N C E

W H IT E : 0.5617 B L A C K : 0.0923

ESTIM ATED TURNOUT

W H IT E B L A C K

V O T E R S V O T E R S TO TA L

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) 24.9% (1941) 1.7% (7) 1948

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) 26.5% (2061) -11.8% (-50) 2011

E S T IM A T E D TO TA L

T U R N O U T 51.4% (4002) -10.1% (-43) 3959

TURNOUT CONFIDENCE INTERVALS

W H IT E V O T E R S B L A C K V O T E R S

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) 10% TO 40% -97% TO 101%

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) 19% TO 34% -65% TO 41%

45

D R . L IC H T M A N ’S P R IM A R Y E L E C T IO N D A T A B A SE

(R E C E IV E D 06/94)

IR W IN C O U N T Y

C O U N T Y C O M M IS S IO N E R (1) 1980

IN IT IA L E L E C T IO N

V O T E R R E G IS T R A T IO N , 1981

W H IT E V O T E R B L A C K V O T E R

R E G IS T R A T IO N , 2909 R E G IS T R A T IO N , 560

10 DATA P O IN T S

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

W H IT E V O T E S C A S T F O R

W H IT E C A N D ID A T E (S):

57%

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N

(R -SQ )

W H IT E : 0.0604

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F

S T A T IS T IC A L

S IG N IF IC A N C E

W H IT E : 0.4937

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

B L A C K V O T E S C A S T F O R

B L A C K C A N D ID A T E (S ):

-2677%

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N

(R-SQ )

B L A C K : 0.2961

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F

S T A T IS T IC A L

S IG N IF IC A N C E

B L A C K : 0.1039

ESTIM ATED TURNOUT

W H IT E B L A C K

V O T E R S V O T E R S TOTA L

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) 42.2% (1228) 16.7% (93) 1321

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) 32.3% (939) -16.1% (-90) 849

E S T IM A T E D TO TA L

T U R N O U T 74.5% (2167) 0.6% (3) 2170

46

TURNOUT CONFIDENCE INTERVALS

W H IT E V O T E R S B L A C K V O T E R S

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) 15% TO 70% -64% TO 97%

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) 12% TO 53% -75% TO 43%

D R . L IC H T M A N ’S P R IM A R Y E L E C T IO N D A T A B A SE

(R E C E IV E D 06/94)

IR W IN C O U N T Y

C O U N T Y C O M M IS S IO N E R (1) 1980

R U N O F F E L E C T IO N

V O T E R R E G IS T R A T IO N , 1981

W H IT E V O T E R

R E G IS T R A T IO N , 874

6 DATA P O IN T S

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

W H IT E V O T E S C A S T F O R

W H IT E C A N D ID A T E (S ):

52%

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N

(R -SQ )

W H IT E : 0.014

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F

S T A T IS T IC A L

S IG N IF IC A N C E

W H IT E : 0.8233

B L A C K V O T E R

R E G IS T R A T IO N , 115

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

B L A C K V O T E S C A S T F O R

B L A C K C A N D ID A T E (S ):

-32%

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N

(R-SQ )

B L A C K : 0.1394

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F

S T A T IS T IC A L

S IG N IF IC A N C E

B L A C K : 0.466

47

ESTIM ATED TURNOUT

W H IT E B L A C K

V O T E R S V O T E R S TOTA L

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) 37.7% (329) 57.3% (66) 395

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) 34.3% (300) -13.9% (-16) 284

E S T IM A T E D TO TA L

T U R N O U T 72.0% (629) 43.5% (50) 679

TURNOUT CONFIDENCE INTERVALS

W H IT E V O T E R S B L A C K V O T E R S

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) -29% TO 104%> -171% TO 285%

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) -14% TO 83% -179% TO 151%

D R . L IC H T M A N ’S P R IM A R Y E L E C T IO N D A T A B A SE

(R E C E IV E D 06/94)

J E N K I N S C O U N T Y

C O U N T Y C O M M IS S IO N E R (1) 1972

R U N O F F E L E C T IO N

V O T E R R E G IS T R A T IO N , 1972

W H IT E V O T E R B L A C K V O T E R

R E G IS T R A T IO N , 2940 R E G IS T R A T IO N , 1152

7 DATA P O IN T S

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

W H IT E V O T E S C A S T F O R

W H IT E C A N D ID A T E (S ):

54%

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N

(R-SQ )

W H IT E : 0.0621

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F

S T A T IS T IC A L

S IG N IF IC A N C E

W H IT E : 0.5899

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

B L A C K V O T E S C A S T F O R

B L A C K C A N D ID A T E (S ):

49%

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N

(R -SQ )

B L A C K : 0.1589

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F

S T A T IS T IC A L

S IG N IF IC A N C E

B L A C K : 0.3758

48

ESTIM ATED TURNOUT

W H IT E B L A C K

V O T E R S V O T E R S TO TA L

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) 24.3% (715) 60.6% (698) 1413

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) 20.3% (598) 58.9% (678) 1276

E S T IM A T E D TO TA L

T U R N O U T 44.6% (1312) 119.5% (1377) 2689

TURNOUT CONFIDENCE INTERVALS

W H IT E V O T E R S B L A C K V O T E R S

F O R W H IT E C A N D (S ) -8% TO 57% -16% TO 137%

F O R B L A C K C A N D (S ) -0% TO 41% 11% TO 107%

49

L IC H T M A N DATA (R E V IS E D )

B A L D W IN C O U N T Y

C O U N T Y C O M M IS S IO N E R (1) 1988

IN I T IA L E L E C T IO N

V O T E R R E G IS T R A T IO N , 1988

5 DA TA P O IN T S

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

W H IT E V O T E S C A S T F O R B L A C K V O T E S C A S T F O R

W H IT E C A N D ID A T E (S ): 17.7 % B L A C K C A N D ID A T E (S ): -40%

C O N F ID E N C E IN T E R V A L C O N F ID E N C E IN T E R V A L

W H IT E V O T E F O R W H IT E B L A C K V O T E F O R B L A C K

C A N D ID A T E (S ): C A N D ID A T E (S ):

-3.9% TO 39.3 % -69.9% TO -10.1%

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N (R-SQ ): 0.92

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F S T A T IS T IC A L S IG N IF IC A N C E :

0.01

L IC H T M A N DATA (R E V IS E D )

B R A N T L E Y C O U N T Y

C O U N T Y C O M M IS S IO N E R (3) 1980

R U N O F F E L E C T IO N

V O T E R R E G IS T R A T IO N , 1980

9 DATA P O IN T S

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

W H IT E V O T E S C A S T F O R

W H IT E C A N D ID A T E (S ):

56.4%

E S T IM A T E D P E R C E N T O F

B L A C K V O T E S C A S T F O R

B L A C K C A N D ID A T E (S ):

164.9%

C O N F ID E N C E IN T E R V A L

W H IT E V O T E F O R W H IT E

C A N D I D A T E (S):

16.9% TO 95.9%

C O N F ID E N C E IN T E R V A L

B L A C K V O T E F O R B L A C K

C A N D ID A T E (S ):

-47.5% TO 377.3%

50

S Q U A R E D C O R R E L A T IO N (R-SQ ): 0.21

P -V A L U E M E A S U R E O F S T A T IS T IC A L S IG N IF IC A N C E :

0.214

L IC H T M A N DATA (R E V IS E D )

B R O O K S C O U N T Y

S C H O O L B O A R D 1986

R U N O F F E L E C T IO N

V O T E R R E G IS T R A T IO N , 1986

11 DATA P O IN T S