Sibron v NYS Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1967

93 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sibron v NYS Brief Amicus Curiae, 1967. d4f5a660-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f34195bb-fbac-400a-a148-a559f3664cdc/sibron-v-nys-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

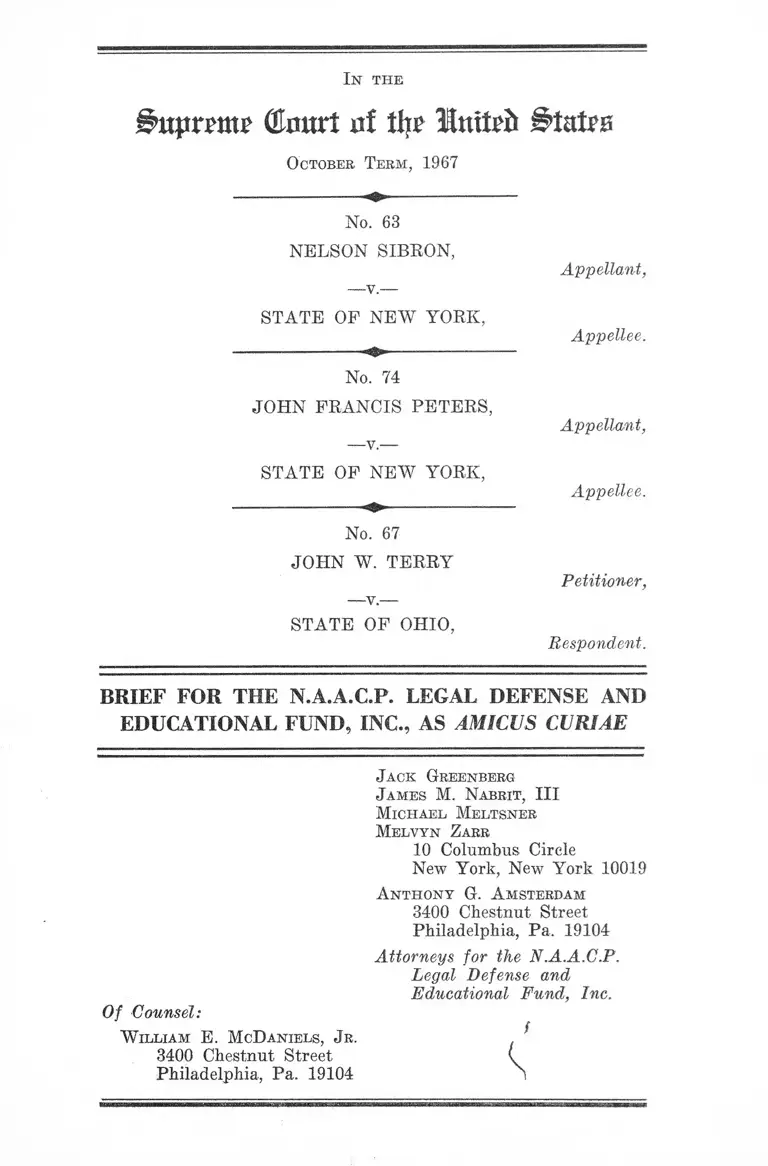

In the

IhtprmT Glmtrt nf tlje llniteii Stairs

October Term, 1967

No. 63

NELSON SIBEON,

—■v.—

STATE OP NEW YORK,

No. 74

JOHN FRANCIS PETERS,

STATE OP NEW YORK,

No. 67

JOHN W. TERRY

STATE OP OHIO,

Appellant,

Appellee.

Appellant,

Appellee.

Petitioner,

Respondent.

BRIEF FOR THE N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE

Of Conns el:

W illiam E. McDaniels, Jr.

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

Attorneys for the N.A.A.C.P.

Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

f

I N D E X

PAGE

Interest of the Amicus Curiae................................. ........... 1

A rgument

I. The Issues............................................................... 9

II. The Genius of Probable Cause ............................ 21

III. The Deceptive Allure of “Reasonable Suspi

cion” ............................- .... .................. -..................... 31

IY. Stop-and-Frisk, Law Enforcement and the Peo

ple ............................................................................ - 58

Conclusion ......... ...... ............ — ........................................ 69

Appendix ............................................ la

Table or A uthorities

Cases:

Aguilar v. Texas, 378 U. S. 108 (1964) .......................... 26,30

Beck v. Ohio, 379 U. S. 89 (1964) ...........13,14,15, 26, 27, 31

Berger v. New York, — — U. S. —-—•, 87 S. Ct. 1873

(1967)................................ ......... ......... 9,14, 21, 30, 31, 57, 58

Blefare v. United States, 362 F. 2d 870 (9th Cir. 1966) 31

Boyd v. United States, 116 U. S. 616 (1886) ...... ............ 35

Brinegar v. United States, 338 U. S. 160 (1949) .......15, 20,

31, 56

Camara v. Municipal Court,------U. S . ------- , 87 S. Ct.

1727 (1967) .............................................................-......... 31

Carroll v. United States, 267 U. S. 132 (1925) .... .......... 30

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227 (1940) ................... 58

Chapman v. United States, 365 IT. S. 610 (1961) .........26, 30

Commonwealth v. Hicks, 209 Pa. Super. 1, 223 A. 2d

873 (1966) ............................. ........... - ........................ -40,41

Commonwealth v. Lehan, 347 Mass. 197, 196 N. E. 2d

840 (1964) ......... .................................................—.......... 49

Cooper v. California, 376 U. S. 58 (1967) ................... 30

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536 (1965) .......................... 24

De Salvatore v. State, 2 Storey (Del.) 550, 163 A. 2d

244 (1960) ............ ........... - ....................................... ...... - 16

Dokes v. Arkansas, 0. T. 1967, No. 109.......................... 2

Giordenello v. United States, 357 U. S. 480 (1958) ....... 30

Goss v. State, 390 P. 2d 220 (Alaska, 1964) ................... 41

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U. S. 479 (1965) — .......... 14

Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 IT. S. 496 (1939) ......................... . 24

Henry v. United States, 361 IT. S. 98 (1959) — 15, 20, 26, 30

Johnson v. United States, 333 IT. S. 10 (1948) ...............7, 26

Jones v. United States, 357 U. S. 493 (1958) .................. 30

Kavanaugh v. Stenhouse, 93 R. I. 252, 174 A. 2d 560

(1961), appeal dismissed, 368 IT. S. 516 (1962) ......... 16

Lankford v. Gelston, 364 F. 2d 197 (4th Cir. 1966) .......4, 69

Lawrence v. Hedger, 3 Taunt. 14, 128 Eng. Pep. 6

(C. P. 1810) .......... ............. ...... ........ .............................. 19

Louisiana v. United States, 380 IT. S. 145 (1965) ........... 25

ii

PAGE

I ll

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643 (1961) ........................... 26

Marcus v. Search Warrant, 367 U. S. 717 (1961) ...A, 21, 23

Marron v. United States, 275 U. S. 192 (1927) ........... 21

McDonald v. United States, 335 U. S. 451 (1948) _____ 23

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U. S. 436 (1966) __________ 24, 58

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167 (1961) ....................... ...... 26

PAGE

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268 (1951) ................... 25

Olmstead v. United States, 277 U. S. 483 (1928) ......... 14

People v. Anonymous, 48 Misc. 2d 713, 265 N. Y. S. 2d

705 (Cty. Ct. 1965) ......... ...... ......................................... 53

People v. Beverly, 200 Cal. App. 2d 119, 19 Cal. Rptr.

67 (D. C. A. 1962) ......... ............. .................................. 41

People y. Cassesse, 47 Misc. 2d 1031, 263 N. Y. S. 2d

734 (Sup. Ct. 1965) .......... ...................... .......... .....18,50,55

People v. Hoffman, 24 App. Div. 2d 497, 261 N. Y. S. 2d

651 (1965) ........................... .............. ......... ............. 17, 49, 54

People v. Michelson, 59 Cal. 2d 448, 380 P. 2d 658

(1963) ................................................ ’....... ..................... 50

People v. Peters, 18 N. Y. 2d 238, 219 N. E. 2d 595

(1966) .................. ............. ........ ...................33,40, 51, 54, 55

People v. Pugach, 15 N. Y. 2d 65, 204 N. E. 2d 176

(1964) .................... ............................17,18,48, 49, 50, 54, 55

People v. Reason, -------Misc. 2 d ------- , 276 N. Y. S. 2d

196 (Sup. Ct. 1966) ............ .............................18,50,53,55

People v. Rivera, 14 N. Y. 2d 441, 201 N. E. 2d 32

(1964) ....... .............................. ................................ 48,49,51

People v. Taggart, C. A. N. Y., App. T. 2, No. 120,

decided July 7, 1967 ....... .............................................. 50, 52

Rios v. United States, 364 IT. S. 253 (1960) ...... .............. 20

IV

Schmerber v. California, 384 U. S. 757 (1966) ...........14, 30

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382 U. S. 87 (1965) ....... 24

Stanford v. Texas, 379 IT. S. 476 (1965) .............4, 21, 22, 23

Staples v. United States, 320 F. 2d 817 (5th Cir. 1963) - 33

State v. Terry, 5 Ohio App. 2d 122, 214 N. E. 2d 114

(1966) .................................................................... ........ - 34

Stoner v. California, 376 U. S. 483 (1964) ........... ........... 30

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 (1940) ..................... 24

United States v. Di Be, 332 U. S. 581 (1948) ...............13,14

United States v. Margeson, 259 F. Supp. 256 (E. D. Pa.

1966) ......... ........................................................................ 49

Warden v. Ray den ,-----■ U. S. ------- , 87 S. Ct. 1642

(1967) ....... - .......................................................... ......... 30

Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U. S. 471 (1963) .... 13, 30

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963) ....................... 25

Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886) ............. 25

Statutes:

Del. Code Ann., tit. 11, §§ 1902-1903 ............................ . 16

N. H. Rev. Laws, §§594:2-594:3 (1955) ...................... 16

New York Code of Criminal Procedure, § 180-a.......16, 57

R. I. Gen. Laws, §§ 12-7-1-12-7-2 (1.956) ............ .......... 16

Uniform Arrest Act, § 2 .............................................. 16,17

Uniform Arrest Act, § 3 ........... .... ...... ............................. 18

PAGE

V

Other Authorities:

Adams, Field Interrogations, 7 P olice 26 (1963) .... 37, 46

Amebic ah Civil L iberties Union, P olice P ower and

Citizens’ R ights (1967) .......................................... 4, 7, 44

A merican Civil L iberties Union of Southern Cali

fornia, R eport, P olice Malpractice and the W atts

R iot (1965), reproduced in Cray, T he B ig Blue

L ine (1967) ....................................... ................................. 2

A merican Law Institute, Code op Criminal P roce

dure, § 18, Official Draft, June 15, 1930 ................... 32

A merican Law I nstitute, Model Code of P re-Ar

raignment P rocedure, Tent. Draft No. 1, March 1,

1966 ............................................. 10,16,17,18,19,20,32,38

PAGE

Aspen, Arrest and Arrest Alternatives: Recent

Trends, U. III. L. F orum 241 (1966) .......................... 11

Baldwin, Nobody K nows My Name (Dell ed. 1963) .... 44

Barrett, Personal Rights, Property Rights, and the

Fourth Amendment, Supreme Court R ev. (1960) ... 10, 34

Bator & Vorenberg, Arrest, Detention, Interrogation

and the Right to Counsel: Basic Problems and Pos

sible Legislative Solutions, 66 Colum. L. Rev. 62

(1966) 10

Bristow, F ield I nterrogation (2d ed. 1964) ...... 46,47,52

Brooks, New York’s Finest, 40 Commentary 29 (Aug.

1965) 44

Case Note, 35 F ordham L. Rev. 355 (1966) ............... 11

Comment, Police Power to Stop, Frisk and Question

Suspicious Persons, 65 Colum. L. R ev. 847 (1965) ....11,19

Comment, Selective Detention and the Exclusionary

Rule, 34 U. Ch i. L. R ev. 158 (1966) 11

VI

Cray, T he B ig Blue Line (1967) .... ............ 4, 6, 36, 37, 48

Cross, The Negro, Prejudice and the Police, 55 J.

Cbim . L., Crim . & P ol. Sci. 405 (1964) _____ _______ 44

Devlin, T he Criminal Prosecution in E ngland

(1958) ...................................................... ............... ........ 13

District op Columbia, R eport and R ecommendations

op the Commissioners’ Committee on P olice A r

rests for Investigation (1962) (The Horsky Re

port) ..................... — .................. ........-............ ............ 5, 6,10

3 E lliot’s Debates (2d ed. 1836) ..................................—. 22

Foote, The Fourth Amendment: Obstacle or Neces

sity in the Law of Arrest, 51 J. Crim. L., Crim. &

P ol. Sci. 402 (1960) ...... ....................... 6,10,13,33,48, 60

Foote, Law and Police Practice: Safeguards in the

Law of Arrest, 52 Nw. U. L. R ev. 16 (1957) .... . 5, 6,10,

48, 59

Fraenkel, Concerning Searches and Seizures, 35 Harv.

L. R ev. 361 (1921) ................ .............................. .......... 21,22

Goldstein, Police Policy Formulation: A Proposal for

Improving Police Performance, 65 Mich . L. R ev.

1123 (1967) ............................................................. - ...... 11,59

2 Hale, Pleas of the Crown (1st Amer. ed. 1847) .... 19

2 H awkins, Pleas of the Crown (8th ed. 1824) ____ 19

Hayden, The Occupation of Newark, 9 New Y ork R e

view of B ooks, No. 3, Aug. 24, 1967 ......... .................. 62

Hazard, Book Review, 34 U. Ch i. L. R ev. 226 (1966) 44

Hogan & Snee, The McNabb-Mallory Rule: Its Rise,

Rationale and Rescue, 47 Geo. L. J. 1 (1958) ............ 40

Kamisar, Book Review, 76 Harv. L. R ev. 1502 (1963) ....6,11

PAGE

vii

Kamisar, A Dissent from the Miranda Dissent: Some

Comments on the “New” Fifth Amendment and the

“ Old” Voluntariness Test, 65 Mich. L. R ev. 59

(1966) ......... ....... ......... ............ .......... ................... ..... . 11

Kennedy, Crime in the Cities: Improving the Ad

ministration of Criminal Justice, 58 J. Crim. L.,

Grim. & P ol. Sci. 142 (1967) -....................................... 60

Kuh, Reflections on New York’s “ Stop-and-Frisk” Law

and Its Claimed Unconstitutionality, 56 J. Grim. L.,

Grim. & P ol. Sci. 32 (1965) ...... ............... ........... ...... 11,19

LaF ave, A rrest— T he Decision to Take a Suspect

into Custody (1965) ..................................................2,5,10

LaFave, Detention for Investigation by the Police: An

Analysis of Current Practices, W ash. IT. L. Q. 331

(1962) ..... ........... ............... .............................5,10

LaFave, Search and Seizure: “ The Course of True

Law . . . Has Not . . . Run Smooth, U. III. L. F orum

255 (1966) ....................................................................... 11

Landynski, Search and Seizure and the Supreme

Court: A Study in Constitutional Interpreta

tion (Johns Hopkins University Studies in Histori

cal and Political Science, ser. 84, no. 1) (1966) ....21, 24, 26

Lasson, The H istory and Development of the F our

teenth A mendment to the United States Consti

tution (Johns Hopkins University Studies in His

torical and Political Science, ser. 40, no. 2) (1937) .... 21

Leagre, The Fourth Amendment and the Law of

Arrest, 54 J. Crim. L., Crim. & P ol. Sci. 393

PAGE

(1963)... .....................................................................................................................10,19,39

Legislation, 38 St. J ohn’s L. R ev. 392 (1964) ............... 11

V l l l

PAGE

Mascolo, The Role of Functional Observation in the

Law of Search and Seizure: A Study in Misconcep

tion, 71 D ick. L. Key. 379 (1967) ....... ........... ........... 32

2 May’s Constitutional H istory oe E ngland (Amer.

ed. 1864) ______ ____ _______ ____________ __________22, 23

McIntyre & Chabraja, The Intensive Search of a Sus

pect’s Body and Clothing, 58 J. Crim. L., Crim. &

P ol. Sci. 18 (1967) ............................. ............... ...... . 51

New York Times, January 23, 1966 .............................. . 8

New York Times, Edit., July 16, 1967 .......... .................... 62

Norris, Constitutional Law Enforcement Is Effective

Law Enforcement: Toward a Concept of Police in

a Democracy and a Citizens’ Advisory Board, 43 IT.

D et . L . J. 203 (1965) ............. .......... .......................... 59

Note, Detention, Arrest and Salt Lake City Police

Practices, 9 U tah L . R ev. 593 (1965) ................. .... ..5,11

Note, 4 H ouston L . K ey. 589 (1966) ....... ............. .... .... 11

Note, Philadelphia Police Practices and the Law of

Arrest, 100 U. P a . L . R ev. 1182 (1952) ............... 5,11,32

Note, “ Stop and Frisk” and Its Application in the Law

of Pennsylvania, 28 U. P it t . L. R ev. 488 (1967) .....11

Note, Stop and Frisk in California, 18 H astings L. J.

(1967) ............. ...... .................. ......... ........... .......... .......11,47

Note, 13 W ayne L . R ev. 449 (1967) ........................ ....... 11

P ayton , P atrol P rocedure (1966) ............................ ....47,49

Perkins, The Law of Arrest, 25 I owa L . R ev. 201 (1940) 13

P resident ’s C ommission on L aw E neorcement and

A dministration of J ustice , T ask F orce R epo rt :

T he P olice (1967) .....................2, 3, 5, 26, 45, 51, 61, 63, 67

P resident ’s C omm ittee on C ivil R ights , R eport : To

S ecure T hese R ights (1947) 4

IX

PAGE

Recent Case, 71 D ic k . L. R ev. 682 (1967) ........... ........... 11

Recent Decision, 37 M ic h . L. R ev. 311 (1938) ........ . 12

Recent Decision, 5 D uquesne L. R ev. 444 (1967) ........... 11

Recent Decision, 18 W. R es. L. R ev . 1031 (1967) .....— 11

Recent Statute, 78 H arv. L. R ev . 473 (1964) __________ 11

Reich, Police Questioning of Law Abiding Citizens, 75

Y ale L. J. 1161 (1966) ................................................. 23

Remington, The Law Relating to “ On the Street” De

tention, Questioning and Frisking of Suspected Per

sons and Police Privileges in General, 51 J. Crim.

L., Cr im . & P ol. Sci. 386 (1960) .......................... 10,17, 32

R eport of th e P resident ’s C ommission on Crime in

the D istrict oe C olumbia on th e M etropolitan

P olice D epartm ent (1966) ....... ..................................... .... 44

Rexrotli, The Fuzz, 14 P layboy (no. 7) 76 (July 1967) .. 2

Ronayne, The Right to Investigate and New York’s

“Stop and Frisk” Law, 33 F ordham L. R ev . 211

(1964)... ........... ................................... ............................ 11

Rustin, Black Power and Coalition Politics, 42 Com

m entary 37 (Sept. 1966) ......... ................... ........... ..... 63

Schoenfeld, The “ Stop and Frisk” Law Is Unconstitu

tional, 17 Syracuse L. R ev. 627 (1966) ...... ............... . 11

Schwartz, “ Stop and Frisk” in New York Law and

in Practice: A Case Study in the Abdication of

Judicial Control Over the Police (unpublished manu

script) ............................ .......... ................................. 3, 44, 49

Siegel, The New York “ Stop and Frisk” and “Knock-

Not” Statutes: Are They Constitutional?, 30 Brook

lyn L. R ev. 274 (1964) 11

X

Six Cities Study—A Survey of Racial Attitudes in Six

Northern Cities: Preliminary Findings, A Report

of the Lemberg Center for the Study of Violence,

Brandeis University, June 1967 __________________ 66

S k o ln ic k , J ustice W ith o u t T r ia l : L aw E nforce

m ent in D emocratic S ociety (1966) ....3, 5, 7, 36, 43, 45, 61

Souris, Stop and Frisk or Arrest and Search—The Use

and Misuse of Euphemisms, 57 J. Cr im . L ., Cr im . &

P ol. Sci. 251 (1966) ......................................... ....................11,48

S tate op N ew Y ork , T emporary S tate C ommission on

th e C onstitutional Convention , I ndividual L iber

ties, th e A dministration op Crim in al J ustice (1967) 11

2 S tudies in Crime and L aw E nforcement in M ajor

M etropolitan A reas (Field Surveys I I I ) (Report of

a Research Study Submitted to the President’s Com

mission on Law Enforcement and Administration of

Justice, 1967) ................... ......................................... 3,5,36

“ Summer Riots,” New Republic, June 24, 1967 .......... 62

Symposium Note, The Law of Arrest: Constitution

ality of Detention and Frisk Acts, 59 Nw. U. L. R ev.

641 (1964) .................................. 11,17

Thomas, Arrest: A General View, Cr im . L. R ev. 639

(1966) .......................................... 19

Thomas, The Law of Search and Seizure: Further

Ground for Rationalisation, Cr im . L . R ev. 3 (1967) .... 20

T iffan y , M cI ntyre & R otenberg, D etection of Crime :

S topping and Q uestioning , S earch & S eizure , E n

couragement & E n trapm en t (1967) ..................3 ,5 ,1 0 ,4 1 ,

47, 49, 52

Traynor, Lawbreakers, Courts and Law-Abiders, 31

Mo. L. R ev. 181 (1966)

PAGE

59

XI

Traynor, Mapp v. Ohio at Large in the Fifth States,

Duke L. J. 319 (1962) ..... ....................................... ....... 11

Trebach, T he R ationing op J ustice (1964) .... ........... 4

T udor, L ife of James Otis (1823) .................................... 23

Vorenberg, Police Detention and Interrogation of Un

counselled Suspects: The Supreme Court and the

States, 44 B. U. L. R ev. 423 (1964) ................... ....... 11

Waite, The Law of Arrest, 24 Texas L. R ev. 275 (1946) 13

Warner, The Uniform Arrest Act, 28 V a. L. R ev. 315

(1942) ....... ................... ..................................... ..........11,13, 16

Wilgus, Arrest Without a Warrant, 22 Mich. L. R ev.

541 (1924) .............................. .............. ................... ....... 13

Williams, Police Detention and Arrest Privileges

Under Foreign Law: England, 51 J. Crim. L., Crim.

& P ol. Sci. 413 (1960) ....... ............................................ 13

Wilson, Police Arrest Privileges in a Free Society: A

Plea for Modernization, 51 J. Crim. L., Crim. & P ol.

Sci. 395 (1960)

PAGE

11

In the

Bnpnmv (&mrt nt f c 'MnxUb Btntvz

October Term, 1967

No, 63

NELSON Sibron,

Appellant,

—v.—

State op New Y ork,

Appellee.

No. 74

John F rancis Peters,

Appellant,

— v.—

State op New Y ork,

Appellee.

No. 67

John W. Terry,

Petitioner,

—v.—

State op Ohio,

Respondent.

BRIEF FOR THE N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE

Interest o f the Amicus Curiae

“I am married to Raymond Fullwood, a Negro. Because

I am Caucasian, in the five years of our marriage, we

have been stopped no less than twenty times by Los

Angeles police officers. . . . I am certain that the rea

son they chose to stop us is because we are a mixed

2

couple.” Mrs. Marilyn Fullwood, in Los Angeles, Cali

fornia.1

“Association of a woman with men of another race

usually results in the immediate conclusion that she

is a prostitute. If a Negro woman is found in the com

pany of a white man, she is usually confronted toy the

police and taken to the station unless it is clear that

the association is legitimate.” Detroit, Michigan police

practice, as observed by Professor Wayne E. LaPave.2

The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., is a non-profit membership corporation, incorporated

under the laws of the State of New York in 1939. It was

formed to assist Negroes to secure their constitutional

rights by the prosecution of lawsuits. Its charter declares

that its purposes include rendering legal aid gratuitously

to Negroes suffering injustice by reason of race or color

who are unable, on account of poverty, to employ and en

gage legal aid on their own behalf. The charter was ap

1 Quoted in A merican Civil L iberties Union of Southern

California, Report, Police Malpractice and the W atts R iot

15-16 (1965), reproduced in Cray, The Big Blue L ine 31 (1967).

Cray documents for other cities as well as the prevalence of the

police practice of accosting interracial couples. Id. at 227 n. 3.

See also Rexroth, The Fuzz, 14 P layboy (No. 7) 76 (July 1967).

2 LaF ave, A rrest— The Decision to Take a Suspect Into Cus

tody 455 (1965). See President’s Commission on Law Enforce

ment and A dministration of Justice, Task F orce Report : The

P olice 184 (1967) : “ [F]ield interrogations are sometimes, used in

a way which discriminates against minority groups, the poor, and

the juvenile. For example, the Michigan State Survey found, on

the basis of riding with patrol units in two cities, that members of

minority groups were often stopped, particularly if found in

groups, in the company of white people, or at night in white

neighborhoods, and that this caused serious problems.” Of. TJokes

v. Arkansas, 0. T. 1967, No. 109.

3

proved by a New York court, authorizing the organization

to serve as a legal aid society. The N.A.A.C.P. Legal De

fense and Educational Fund, Inc., is independent of other

organizations and supported by contributions of funds

from the public.

A central purpose of the Fund is the legal eradication

of practices in our society that bear with discriminatory

harshness upon Negroes and upon the poor, deprived, and

friendless, who too often are Negroes. The stop and frisk

procedure which New York and Ohio ask this Court to

legitimate in these eases is such a practice. The evidence

is weighty and uncontradicted that stop and frisk power

is employed by the police most frequently against the in

habitants of our inner cities, racial minorities and the

underprivileged.3 This is no historical accident or passing

circumstance. The essence of stop and frisk doctrine is

the sanctioning of judicially uncontrolled and uncontrol

lable discretion by law enforcement officers.4 History, and

not in this century alone, has taught that such discretion

comes inevitably to be used as an instrument of oppression

3 President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and A dminis

tration of J ustice, Task F orce Report: The Police 183-185

(1967); 2 Studies in Crime and Law Enforcement in Major

Metropolitan A reas (Field Surveys III) 82-108 (Report of a

Research Study Submitted to the President’s Commission on Law

Enforcement and Administration of Justice, 1967) [hereafter cited

as University of Michigan Study] ; Skolnick, Justice W ithout

Trial : Law Enforcement in D emocratic Society 217-219

(1966); Tiffany, McIntyre & Rotenberg, Detection of Crim e :

Stopping and Questioning, Search & Seizure, Encouragement &

Entrapment 20-21 (1967) ; Schwartz (Herman), “Stop and Frisk”

in New York Law and in Practice: A Case Study in the Abdica

tion of Judicial Control Over the Police (unpublished manuscript)

31-34, and authorities cited.

4 See part III, infra.

4

of the unpopular.5 It was so in the case of the search and

seizure practices which the Fourth Amendment was written

to condemn.6 We believe that that Amendment protects

the unpopular, the Negro, and all our citizens alike, from

subjection to the oppressive police discretion which stop

and frisk embodies.

In the litigation now before the Court—as is usual in

cases where police practices are challenged—two parties

essentially are represented. Law enforcement officials,

legal representatives of their respective States, ask the

Court to broaden police powers, and thereby to sustain

what has proved to be a “ good pinch.” Criminal defen

dants caught with the goods through what in retrospect

appears to be at least shrewd and successful (albeit con

stitutionally questionable) police work ask the Court to

declare that work illegal and to reverse their convictions.

Other parties intimately affected by the issues before the

Court are not represented. The many thousands of our

citizens who have been or may be stopped and frisked

5 “Where lawless police forces exist, their activities may impair

the civil rights of any citizen. In one place the brunt of illegal

police activity may fall on suspected vagrants, in another on union

organizers, and in another on unpopular racial and religious minor

ities, such as Negroes, Mexicans, or Jehovah’s Witnesses. But

wherever unfettered police lawlessness exists, civil rights may be

vulnerable to the prejudices of the region or of dominant local

groups, and to the caprice of individual policemen. Unpopular,

weak, or defenseless groups are most apt to suffer.” President’s

Committee on Civil Bights, Beport: To Secure These B ights

25 (1947). See also Tkebach, The E ationing op Justice 5-6

(1964) ; Cray, The Big Blue L ine 113-127, 183-194 (1967) ;

A merican Civil L iberties Union, Police Power and Citizens’

Bights 6-13 (1967) ; Lankford v. Gelston, 364 F. 2d 197, 203-204

(4th Cir. 1966) (en banc).

6 See the history recounted in Marcus v. Search, Warrant, 367

U. S. 717 (1961), and Stanford v. Texas, 379 U. S. 476 (1965).

5

yearly, only to be released when the police find them inno

cent of any crime, are not represented.7 The records of

their cases are not before the Court and cannot be brought

7 The prevalence of the practice of street detention and interro

gation, and of the related practice of arrest for investigation, is

universally acknowledged. Concerning the former, see President’s

Commission on Law Enforcement and A dministration of Jus

tice, op. cit. supra, note 3, at 183-185; Skolnick, op. cit. supra,

note 3, at 224-225; LaFave, op. cit. supra, note 3, at 344-345; Tif

fany, McIntyre & R otenberg, op. cit. supra, note 3, at 5-86;

Note, Detention, Arrest, and Salt Lake City Police Practices, 9

Utah L. Rev. 593, 610-616, 618 (1965) ; Note, Philadelphia Police

Practices and the Law of Arrest, 100 U. Pa . L. Rev. 1182, 1189,

1193, 1195, 1200-1206 (1952). Concerning the latter, see District

of Columbia, Report and Recommendations of the Commission

ers’ Committee on P olice A rrests for Investigation (1962) {The

Horsky Report) ; LaF ave, op. cit. supra, note 3, at 300-364; Tee-

bach, op. cit. supra, note 5, at 4-7; Foote, Law and Police Practice:

Safeguards in the Law of Arrest, 52 Nw. U. L. R ev. 16 (1957);

LaFave, Detention for Investigation hy the Police: An Analysis of

Current Practices [1962], W ash. U. L. Q. 331.

What proportion of persons subjected to these practices and

frisked or searched is found to be innocent of any crime cannot

now be reliably determined. The National Crime Commission’s

Task Force on Police describes a study finding that twro out of ten

persons “frisked” were found to be carrying either a gun or a

knife. President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Ad

ministration of Justice, op. cit. supra, note 3, at 185. We have

not been able to determine whether the study referred to is the

same study (involving 224 cases) that is summarized in 2 Uni

versity of Michigan Study 87, but it appears to be. The summary

coincides with the Task Force Report in showing that guns or

knives were discovered in twenty-one per cent of personal searches

by police. Like the Task Force Report, it does not purport to say

what proportion of these weapons was illegally possessed. It does

disclose that stolen property and other criminal evidence was very

infrequently found, with the result that seventy-nine out of one

hundred persons searched by police in confrontations originating

“on view” were discovered to have nothing incriminating; and

seventy-four out of one hundred persons searched in confrontations

originating with a police dispatch also were discovered to have

nothing incriminating. Most significant, the University of Michigan

study makes clear what the Task Force Report leaves ambiguous:

that the personal searches studied include (and may well be com-

6

here. Yet it is they, far more than those charged with crime,

who will hear the consequences of the rules of constitutional

law which this Court establishes. The determination of the

quantum of “belief” or “ suspicion” required to justify the

exercise of intrusive police authority is precisely the deter

mination of how far afield from instances of obvious guilt the

authority stretches. To lower that quantum is to broaden

the police net and, concomitantly, to increase the number

(and probably the proportion)* 8 of innocent people caught

prised primarily of) searches incident to a valid arrest on prob

able cause. Id. at 89. This last circumstance doubtless explains the

extraordinarily high yield (a little over 20 per cent) reported here,

compared with the low yield elsewhere observed for police investi

gative practices undertaken without probable cause—for example,

the arrests for investigation studied in the Horsky Report, D istrict

of Columbia, Report and Recommendations of the Commission

ers’ Committee on P olice A rrests for Investigation 34 (1962) •

Kamisar, Book Review, 76 H arv. L. Rev. 1502, 1506 (1963) (seven

teen out of eighteen persons arrested for investigation are released

without being charged), and the automobile stops and related prac

tices mentioned in Foote, The Fourth Amendment: Obstacle or

Necessity in the Law of Arrest, 51 J. Crim. L., Crim. & Pol. Sci.

402, 406 (1960). The data, of course, are fragmentary. Of. the

testimony of a retired Detroit policeman before the United States

Civil Rights Commission, quoted in Cray, op. cit. supra, note 5,

at 185:

“ I would estimate— and this I have heard in the station also

—that if you stop and search 50 Negroes and you get one good

arrest out of it that’s a good percentage; it’s a good day’s

work. So, in my opinion, there are 49 Negroes whose rights

have been misused, and that goes on every day. That’s just

about the entire population of Detroit over a period of time.”

8 Again, it is difficult to test this supposition empirically. See

note 7 supra; and see Foote, Law and Police Practice: Safeguards

in the Law of Arrest, 52 Nw. U. L. Rev. 16 (1957). However, if

the sort of police judgment assumed alike by the differing concepts

of probable cause and reasonable suspicion is at all rational, one

would suppose that the less compelling the perceived evidence of

guilt on which an officer acts, the higher proportion of persons he

will affect who turn out to be innocent.

7

up in it. The innocent are those this Court will never see.9

Yet we believe that some attention to their situation and

appreciation of their interests is indispensable to the ap

propriate resolution of the constitutional controversy now

presented. With deference, amicus curiae wishes to speak

principally in behalf of their interests—which we conceive

to be indistinguishable (but for the vagaries of a “ reason

able suspicion” ) from those of the citizenry generally.

These interests, of course, are not adverse to those of

the police, except insofar as the police interests may be

quite parochially defined. The citizen on the street needs

the protection of the police, amply empowered, just as he

needs protection from them. He is the potential victim

both of crime and of law enforcement. His interest does

not lie in “handcuffing the police.” But neither does it lie

in giving the police every power over his life which they

claim is indispensable to efficient crime control.10 Against

9 “ The statistical data [about abusive police practices] are diffi

cult to find and document, for most people who are mistreated by

the police tend to be poor, friendless, out-of-the-ordinary members

of society and frequently in trouble with the law in other situations.

They don’t complain often, and wrhen they do, seldom have the

money, time, confidence in the ‘system’ or knowledge of the agen

cies that could help them to thread their way through the maze of

legal steps necessary to challenge the abuse.

“Moreover, fear of reprisal by the police is quite real, especially

among Negroes and other minorities, but this trepidation has no

social or economic bounds. There is a general wish to ‘stay out of

trouble’ among many white, middle-class citizens.” A merican

Civil Liberties Union, Police Power and Citizens’ R ights 6

(1967). See also Skolnick, op. cit. supra, note 3, at 221-222, 233-

234.

10 Cf. Johnson v. United States, 333 U. S. 10, 14 (1948) : “ Crime,

even in the privacy of one’s own quarters, is, of course, of grave

concern to society, and the law allows such crime to be reached on

proper showing. The right of officers to thrust themselves into a

home is also a grave concern, not only to the individual but to a

society which chooses to dwell in reasonable security and freedom

8

that latter coarse the Fourth Amendment and every aspira

tion of a free society oppose.11

The parties have consented to the filing of an amicus

curiae brief by the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educa

tional Fund, Inc. Copies of their letters of consent will be

submitted to the Clerk with this brief.

from surveillance. When the right of privacy must reasonably

yield to the right of search is, as a rule, to be decided by a judicial

officer, not by a policeman or government enforcement agent.”

11 It is not so with some societies. Consider the extraordinarily

efficient South African police practice reported in the New York

Times, January 23,1966 :

“Johannesburg, Jan. 22— The police in Johannesburg

have hit on an effective, if crude, way to reverse an alarming

rise in armed robberies in the city: to treat every black man

as a criminal suspect.

“ This is done by saturating a proscribed area with police

men under orders to check the ‘reference books’—the passports

all blacks must carry in ‘white’ areas— of every African they

encounter. Sometimes the orders also call for thorough searches

of any parcels the blacks may be carrying, or even of their

persons.

“ These police blitzes employ anywhere from 1,000 to 2,500

officers each. They come without warning, usually to the city’s

business district. .. .

“ The arrests are almost always for irregularities in the ref

erence books, not for armed robbery. But the effect is evi

dently to keep criminals off the streets and off balance. Since

early November the raids have been held almost weekly, with

the result that the number of armed robberies has been re

duced by more than 50 per cent.U

“ The undeniable success of the raids shows that it is not a

fantastic notion for the white authorities to find a suspicion

of criminality in a black skin— an indication of the extent to

which this is a society at war with itself.”

9

A R G U M E N T

I.

The Issues.

These stop and frisk cases present a congeries of issues.

May a police officer constitutionally restrain an individual

for the sole purpose of investigating him? If so, under

what circumstances? Upon probable cause to believe him

guilty of a crime? Upon “ reasonable suspicion” ?12 What is

the permissible extent of the restraint? How long may it

last?13 How much force may be used to effect it? May the

police officer constitutionally search the citizen incident to

such restraint, or incident to questioning without restraint?

If so, under what circumstances? Whenever a citizen is

restrained or questioned? When there is probable cause to

believe (or when there is “ reasonable suspicion” ) that the

citizen is armed? How intrusive may the search be? May

some or all objects discovered in the search be admitted

12 The present cases do not present factually the question of the

extent of police powers to “ freeze” the scene of a recent and pal

pable crime, as where patrol officers responding to a call find a man

bleeding on the ground and others fleeing. Nor are those cases

necessarily controlled by what the Court may hold here.

13 The present cases do not present factually instances of ex

tended on-the-street detention. Nor do they present instances of

removal of the citizen to a squad car or to the police station. How

ever, insofar as the New York statute here attacked on its face

may allow extended detention and a shift in the locus of custody,

this Court may properly consider the constitutionality of a stop-

and-frisk authorization which is not limited in the time or place of

the detention it allows. Cf. Berger v. New York, ------ U. S. ------ ,

87 S. Ct. 1873 (1967).

10

into evidence against the citizen in a criminal trial?

Weapons? Burglars’ tools? Narcotics?14

This Court may wish to treat these issues more or less

discretely. But their proliferation should not conceal the

point that what is fundamentally in question here is the

choice, under the Constitution, between two antagonistic

models of the police investigative process. This is true

conceptually, as study of the burgeoning literature of stop

and frisk reveals.15 It is true historically, because the Court

14 The present cases do not present factually the question whether

objects seized in a frisk, other than those which it is illegal to

possess, may be used in evidence in a criminal trial of the frisked

citizen. However, because of the intimate relationship between the

substantive constitutional rules regulating police conduct and the

exclusionary sanction by which they are enforced, see part II,

infra, the Court may wish to consider that question.

15 Detailed and useful analyses of stop and frisk doctrine and

related issues are found in A merican Law Institute, Model Code

of Pre-Arraignment Procedure, Tent. Draft No. 1, March 1,

1966, Commentary on §2.02, at pp. 91-105; D istrict of Columbia,

Report and Recommendations of tile Commissioners’ Committee

on Police A rrests for Investigation (1962) (The Horsky Re

port) ; L aF ave, A rrest : T he Decision to Take a Suspect Into

Custody 300-364 (1965); Tiffany, McIntyre & Rotenberg, D e

tection of Crim e : Stopping & Questioning, Search & Seizure,

Encouragement and Entrapment 5-94 (1967) ; Barrett, Personal

Rights, Property Rights, and the Fourth Amendment [1960], Su

preme Court Rev. 46, 57-70; Bator & Yorenberg, Arrest, Deten

tion, Interrogation and the Right to Counsel: Basic Problems and

Possible Legislative Solutions, 66 Colum. L. Rev. 62 (1966) ; Foote,

Law and Police Practice: Safeguards in the Law of Arrest, 52 Nw.

U. L. Rev. 16 (1957) ; Foote, The Fourth Amendment: Obstacle

or Necessity in the Law of Arrest, 51 J. Crim. L., Crim. & Pol. Sci.

402 (1960) ; LaFave, Detention for Investigation by the Police:

An Analysis of Current Practices (1962), W ash. U. L. Q. 331;

Leagre, The Fourth Amendment and the Law of Arrest, 54 J. Crim.

L., Crim. & Pol. Sci. 393 (1963) ; Remington, The Law Relating

to “ On the Street” Detention, Questioning and Frisking of Sus

pected Persons and Police Privileges in General, 51 J. Crim. L.,

Crim. & P ol. Sci. 386 (1960) ; Souris, Stop and Frisk or Arrest

and Search— The Use and Misuse of Euphemisms, 57 J. Crim. L.,

11

is now asked for the first time to legitimate criminal investi

gative activity that significantly intrudes upon the privacy

Crim. & Pol. Sci. 251 (1966) ; Warner, The Uniform Arrest Act,

28 V a . L. Rev. 315 (1942) ; Wilson, Police Arrest Privileges in a

Free Society: A Plea for Modernization, 51 J. Crim. L., Crim. &

P ol. Sci. 395 (1960); Note, Stop and Frisk in California, 18 H ast

ings L. J. 623 (1967) ; Comment, Selective Detention and the Ex

clusionary Buie, 34 U. Chi. L. Rev. 158 (1966); Comment, Police

Power to Stop, Frisk, and Question Suspicious Persons, 65 Colum.

L. Rev. 847 (1965); Note, Detention, Arrest, and Salt Lake City

Police Practices, 9 Utah L. Rev. 593 (1965) • Symposium Note,

The Law of Arrest: Constitutionality of Detention and Frisk Acts,

59 Nw. U. L. Rev. 641 (1964); Note, Philadelphia Police Practices

and the Law of Arrest, 100 U. P a. L. Rev. 1182 (1952) ; Note, 4

H ouston L. Rev. 589 (1966); Case Note, 35 F ordham L. Rev. 355

(1966) ; Recent Statute, 78 Harv. L. Rev. 473 (1964).

See also State of New Y ork, Temporary State Commission on

the Constitutional Convention, Individual Liberties, the A d

ministration of Criminal Justice 67-70 (1967) ■ Aspen, Arrest

and Arrest Alternatives: Recent Trends (1966), U. III. L. F orum

241, 250-253; Goldstein,. Police Policy Formulation: A Proposal

for Improving Police Performance, 65 Mich. L. Rev. 1123, 1139-

1140 (1967) ; Kamisar, A Dissent from the Miranda Dissents:

Some Comments on the “New” Fifth Amendment and the “ Old”

Voluntariness Test, 65 Mich. L. Rev. 59, 60-61 n. 8 (1966) ; Kami

sar, Book Review, 76 H arv. L. Rev. 1502 (1963) ; Kuh, Reflections

on New York’s “Stop-and-Frisk” Law and Its Claimed Unconsti

tutionality, 56 J. Crim. L., Crim. & P ol. Sci. 32 (1965); LaFave,

Search and Seizure: “ The Course of True Law . . . Has Not . . . Run

Smooth” [1966], U. III. L. F orum 255, 308-311; Ronayne, The

Right to Investigate and New York’s “Stop and Frisk” Law, 33

F ordham L. Rev, 211 (1964) ; Schoenfeld, The “Stop and Frisk”

Law is Unconstitutional, 17 Syracuse L. Rev. 627 (1966); Siegel,

The New York “ Stop and Frisk” and “Knock-Not” Statutes: Are

They Constitutional?, 30 Brooklyn L. Rev. 274 (1964) ; Traynor,

Mapp v. Ohio at Large in the Fifty States [1962], D uke L. J. 319,

333-334; Vorenberg, Police Detention and Interrogation of Un

counselled Suspects: The Supreme Court a-nd the States, 44

B. U. L. Rev. 423 (1964) ; Note, “Stop and Frisk” and its Applica

tion in the Law of Pennsylvania, 28 U. P itt. L. Rev. 488 (1967) ;

Recent Decision, 18 W. Res. L. Rev. 1031 (1967) ; Recent Case,

71 D ick. L. Rev. 682 (1967); Recent Decision, 5 D uquesne L.

Rev. 444 (1967); Note, 13 W ayne L. Rev. 449 (1967); Legislation,

38 St. J ohn’s L. Rev. 392, 398-405 (1964).

12

of individuals who are undifferentiable from Everyman as

the probable perpetrators of a crime.16 It is true in the

practical, day-to-day world of the streets and the lower

courts, as we propose to develop more fully in the discus

sion that follows. Initially it will be helpful, we believe,

to identify the two contending models and their attributes.

The Classical Arrest-Search Model

Under classical criminal procedure, the police may accost

and question any person for the purpose of criminal inves

tigation.17 But they may not detain him, restrain or “ ar

rest” his liberty of movement in any significant way, except

16 See notes 35-36 infra and accompanying text.

u Most of the older cases cited by the proponents of modern-day

stop and frisk do no more than recognize that the police are free

to question an individual on the street so long as they do not detain

him in any way. Cases which denominate such questioning an

“arrest,” forbidden in the absence of probable cause, are generally

found to involve circumstances in which the police communicated

to the individual an effective sense of restraint. The decisions are

discussed exhaustively in the literature cited in note 15 supra;

note 18 infra. They are adequately summarized in the following

passage from Recent Decision, 37 Mich. L. Rev. 311, 313 (1938) :

“ [Although the courts rarely discuss the question, whether

stopping and questioning is an arrest seems to be decided on

the basis of whether any restraint of personal liberty is in

volved. Thus, where force or threat of force is used and the

subject submits to the authority of the officer for questioning,

an arrest occurs. On the other hand, where the officer merely

approaches or accosts the suspect and asks him questions,

there is no arrest because there is no restraint of the person.

Still other courts hold that merely stopping a traveler on the

highway is an arrest.”

So far as we are aware, no one seriously contends that the police

are or should be prohibited from non-coercive questioning of an in

dividual on the street, provided that it remains clear to him that

he is free to leave and to refuse to answer questions. We, cer

tainly, would not so contend.

13

for the purpose of holding him to answer criminal charges.18

Any such restraint of an individual is an arrest, and may

be made only on probable cause to believe him guilty of an

offense.19 The police may not make a personal search of an

individual, without a warrant or effective consent, except

_18 “ The police have no power to detain anyone unless they charge

him with a specified crime and arrest him accordingly. Arrest

and imprisonment are in law the same thing. Any form of physical

restraint is an arrest, and imprisonment is only a continuing ar

rest. If an arrest is unjustified, it is wrongful in law and is known

as_ false imprisonment. The police have no power whatever to de

tain anyone on suspicion or for the purpose of questioning him.

They cannot even compel anyone whom they do not arrest to come

to the police station.” Devlin, The Criminal Prosecution in Eng

land 82-83 (1958). Accord: Williams, Police Detention and Ar

rest Privileges under Foreign Laiv: England, 51 J. Crim. L., Grim.

& Pol. Sci. 413, 413-414 (1960). This is assumed by the principal

American writers on arrest, see Warner, The Uniform Arrest Act

28 Va . L. Rev. 315, 318 (1942); Waite, The Law of Arrest, 24

Texas L. Rev. 275, 279 (1946) ; Perkins, The Law of Arrest, 25

Iowa L. Rev. 201, 261 (1940) ; Wilgus, Arrest Without a.. War

rant, 22 Mich. L. Rev. 541, 798 (1924). It is also assumed in this

Court’s decisions under the Fourth Amendment, see note 54

infra. Concerning the “ charging purpose” component of classical

arrest theory, see note 55 infra.

Nothing said here touches the question wdiat powers police may

have to take custody of an individual for non-criminal purposes—

as when a sick or drunk adult or a lost child is found on the street.

The question is not now before the Court.

19 E.g., United States v. Di Be, 332 U, S. 581 (1948) ; Johnson v.

United States, 333 L. S. 10 (1948) ; Wong Sun v. United States,

371 U. S. 471 (1963); Beck v. Ohio, 379 U. S. 89 (1964). See

Foote, The Fourth Amendment.- Obstacle or Necessity in the Law

of Arrest, 51 J. Crim. L., Crim. & Pol. Sci. 402:

“In the law of arrest and by long constitutional history,

‘reasonable’ has been interpreted as the equivalent of probable

cause. An officer acts reasonably if, on the facts before him,

it would appear that the suspect has probably committed a

specific crime. This is the context in which the word is used

in the fourth amendment and in most state arrest laws. Our

cases sharply distinguish the reasonableness of an arrest on

probable cause from an unreasonable apprehension grounded

on ‘mere’ suspicion.”

14

that, incidental to a valid arrest, they may make a more or

less intensive personal search.20 The Classical Arrest-

Search Model thus recognizes two categories of police in

vestigative powers. Powers whose exercise does not signifi

cantly invade personal liberty and the right of privacy—the

“ right to be let alone” 21—are given the police to use at

large, indiscriminately, at their discretion, and without ju

dicial supervision. Powers whose exercise does invade these

rights may be used by the police, but not indiscriminately,

not against Everyman. They may be used only against

persons whom there is probable cause, to believe are crim

inal actors, and hence distinguishable from Everyman.

The “probable cause” determination made by a policeman

20 See note 54 infra concerning search incident to arrest. It

is plain that a personal search without a warrant, not incident to

arrest, is forbidden by the Fourth Amendment. United States v.

I)i Be, 332 U. S. 581 (1948) ; Beck v. Ohio, 379 U. S. 89 (1964) ;

and see Schmerber v. California, 384 U. S. 757 (1966).

21 See Mr. Justice Brandeis, dissenting, in Olmstead v. United

States, 277 U. S. 438, 471, 478-479 (1928) :

“ The protection guaranteed by the Amendments, is much

broader in scope. The makers of our Constitution undertook

to secure conditions favorable to the pursuit of happiness.

They recognized the significance of man’s spiritual nature,

of his feelings and of his intellect. They knew that only a

part of the pain, pleasure and satisfactions of life are found

in material things. They sought to protect Americans in their

beliefs, their thought, their emotions and their sensations.

They conferred, as against the Government, the right to be let

alone—the most comprehensive of rights and the most valued

by civilized men. To protect that right, every unjustifiable

intrusion by the Government upon the privacy of the individ

ual, whatever the means employed, must be deemed a viola

tion of the Fourth Amendment. And the use, as evidence in

a criminal proceeding, of facts ascertained by such intru

sion must be deemed a violation of the Fifth.”

Justice Brandeis’ view, of course, has subsequently been vindi

cated by the Court. Berger v. New York,------ U. S .------- , 87 S. Ct.

1873 (1967) ; Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U. S. 479 (1965).

15

as the precondition of the exercise of these powers is

judicially reviewable.22 “ The rule of probable cause is

a practical, nontechnical conception affording the best

compromise that has been found for accommodating

these often opposing interests [of law enforcement and

personal liberty]. Requiring more would unduly hamper

law enforcement. To allow less would be to leave law-abid

ing citizens at the mercy of the officers’ whim or caprice.” 23

The Stop-Frisk Model

In theory, the Stop-Frisk Model differs from the Classical

Arrest-Search Model in that it recognizes at least three,

perhaps more, categories of police powers.24 First, police

may accost and question any person, so long as they do not

restrain or search him. Second, they may arrest him on

probable cause and search his person incident to that valid

arrest. The third category of powers is lodged between

these two. A law enforcement officer lacking probable cause

but having some state of mind (or encountering some cir

cumstances) which makes his focus upon a given individual

something other than random, something more particular

22 “ The requirement of probable cause has roots that are deep

in our history. The general warrant, in which the name of the

person to be arrested was left blank, and the writs of assistance,

against which James Otis inveighed, both perpetuated the oppres

sive practice of allowing the police to arrest and search on sus

picion. Police control took the place of judicial control, since no

showing of ‘probable cause’ before a magistrate was required.”

Henry v. United States, 361 U. S. 98, 100 (1959).

23 Brinegar v. United States, 338 U. S. 160, 176 [1949) (a case

of warrantless search), quoted in Beck v. Ohio, 379 U. S. 89, 91

(1964) (a case of warrantless arrest).

24 The conceptual basis for the Model may involve the repudia

tion of any attempt to categorize, leaving every individuated in

stance of police activity to be determined lawful or unlawful,

constitutional or unconstitutional, through a “balancing” of its

intrusiveness against its justification. See note 57 infra.

16

ized than whim, may “ stop” or detain the individual without

an “ arrest.” The nature of the prerequisite state of mind

(or set of circumstances) varies. The Uniform Arrest Act

uses the phrase “ reasonable ground to suspect.” 25 New

York Code of Criminal Procedure, § 180-a, employs “ reason

ably suspects.” The A. L. I. Model Code of Pre-Arraign

ment Procedure uses other formulations.26 The common

theme is something less than probable cause, but something

which purports to provide a judicial curb against wholly

indiscriminate police action.

The nature of the “ stop” that is not an arrest also varies.

The Uniform Arrest Act permits an officer, unsatisfied by

initial answers to questioning, to detain his suspect for two

hours. The A. L. I. Model Code limits the period to twenty

minutes, and expressly disallows the use of deadly force in

effecting a “ stop.” The New York statute is silent both on

the period of permitted detention and on the amount of

force which the officer may employ to enforce it. Specific

“ stop” authorizations also differ as to whether the “ stop

ping” officer is allowed to remove his detainee from the

25 Uniform Arrest Act, § 2. The Act is set out in Warner, The

Uniform Arrest Act, 28 V a . L. Rev. 315, 343, 344 (1942). Versions

of the Act (using the terms “reasonably suspects” or “reason to

suspect” ) are in effect in Delaware, New Hampshire and Rhode

Island. Del. Code Ann., tit. 11, §§ 1902-1903 (1953); N. II. Rev.

Laws, §§ 594:2-594:3 (1955) ; and Rhode Island, R. I. Gen. Laws,

§§ 12-7-1—12-7-12 (1956). The Act appears to have been gutted

by judicial construction at least in Delaware and Rhode Island,

see De Salvatore v. State, 2 Storey (Del.) 550, 163 A. 2d 244

(1960) ; Kavanaugh v. Stenhouse, 93 R. I. 252, 174 A. 2d 560

(1961) , appeal dismissed for want of a substantial federal ques

tion, 368 U. S. 516 (1962). These decisions appear to equate rea

sonable suspicion with the constitutional standard of probable

cause.

26 A merican Law Institute, Model Code of Pre-Arraignment

Procedure, § 2.02, Tentative Draft No. 1, March 1, 1966, at p. 6.

17

scene of their first encounter.27 They differ with regard to

the places in which and the circumstances under which the

“ stop” power is given. The Uniform Arrest Act allows

stops of persons “ abroad.” The A. L. I. Code has no such

restriction, but delimits the stop power by providing that it

shall not be used “ solely to aid in investigation or preven

tion o f” designated offenses. The New York statute uses

the term “ abroad in a public place” (which the Court of

Appeals in Peters construed to include the common hall

ways of apartment buildings, inconsistently with the con

struction previously put on the phrase in a circular pub

lished for police guidance by the New York State Combined

Council of Law Enforcement Officials),28 and also delimits

the “ reasonable suspicion” to suspicion of felonies and des

ignated misdemeanors.

Under the Btop-FrisJc Model, persons authorized to be

detained may also be “ frisked” or searched. (Undoubtedly,

a legislature might give the power to “ stop” without ac

companying power to “ frisk,” but all of the significant

pieces of legislation so far proposed or enacted couple

“ stop” with “ frisk,” and the proponents of stop and frisk

seem unanimous that “ frisk” is necessary if “ stop” is to

be effective.29 Frisk may be allowed whenever stop is al

27 The Uniform Arrest Act, §2 (2 ), (3) implicitly permits re

moval to a station house. The A. L. I. Model Code, § 2.02(1), (2),

(3) more or less explicitly disallows it. The New York Courts,

construing the New York statute, appear to permit it. People v.

Pugach, 15 N. Y. 2d 65, 204 N. B. 2d 176 (1964); People v. Hoff

man, 24 App. Div. 2d 497, 261 N. Y. S. 2d 651 (1965).

28 See pp. 54-55, infra.

29 E.g., A merican Law Institute, Model Code of Pre-Arraign-

ment Procedure, Commentary to § 2.02, Tent. Draft No. 1, March

1, 1966, at p. 102; Remington, supra,, note 15, at 391; Symposium

Note, supra, note 15, 59 Nw. U. L. Rev. at 652-653.

18

lowed; or it may be allowed only upon the fulfilment of

additional conditions, such as the existence of reasonable

grounds to suspect that the officer is in danger.30 It may be

allowed more or less extensively31 and more or less intru

sively.32 Its object may be limited or unlimited,33 and the

nature of the items discovered in the search which may be

30 The Uniform Arrest Act, § 3, allows search whenever the of

ficer “has reasonable ground to believe that he is in danger if the

person possesses a dangerous weapon.” (Emphasis added.) The

A. L. I. Model Code allows search if the officer “reasonably be

lieves that his safety so requires.” The New York statute purports

to limit the search power to situations in which the officer “rea

sonably suspects that he is in danger of life or limb,” but the

Court of Appeals in the Peters case appears to have read that re

striction out of the statute, by force of a presumption of law

that an officer making a stop is always ipso facto in danger of life

or limb.

31 The Uniform Arrest Act, § 3, and the New York statute au

thorize search of the “person” stopped. The New York courts

have extended the search power to packages carried by that person,

even though these might be put out of his reach during the period

of the stop. People v. Pugach, 15 N. Y. 2d 65, 204 N. Y. 2d 176

(1964) ; People v. Beason,------ Misc. 2 d ------- , 276 N. Y. S. 2d 196

(Sup. Ct. 1966) ; see People v. Cassesse, 47 Misc. 2d 1031, 263

N. Y. S. 2d 734 (Sup. Ct. 1965). The A. L. I. Model Code explicitly

allows the search of the stopped “person and his immediate sur

roundings, but only to the extent necessary to discover any dan

gerous weapons which may on that occasion be used against the

officer.”

32 See the provision of the A. L. I. Model Code quoted in the

preceding footnote. The Commentary to the section explains that

the “search envisaged here should not usually be more intensive than

an ‘external feeling of clothing,’ that is, the traditional ‘frisk.’ ”

A merican Law Institute, Model Code op Pre-Arraignment- P ro

cedure, Commentary on § 2.02, Tentative Draft No. 1, March 1,

1966, at p. 102. Neither the Uniform Arrest Act nor the New

York statute restrict the intrusiveness of searches, except perhaps

by implication in specifying a weapon as the object of search.

But see pp. 50-51, infra.

33 The Uniform Arrest Act, A. L. I. Model Code, and New York

statute alike specify a dangerous weapon as the object of per

mitted search.

19

seized may also be limited or unlimited.34 Tbe common

characteristic of the “ frisk” authorizations is that they

seek to delimit in some fashion the personal searches that

may be made incident to a “ stop,” but none apparently

include within the limitations any requirement of probable

cause (in the classical sense) to believe that the person

searched has a weapon.

It is relatively clear that the Classical Arrest-Search

Model was and is the common law of England, which

has never permitted detention for investigation nor on

less than probable cause.35 36 The same model has also been

34 Both the Uniform Act and the New York statute give the of

ficer power to seize a weapon. This might appear to exclude power

to seize other items found, hut of course the New York courts

have not given it this effect. The A. L. I. Model Code leaves the

question for later resolution.

36 This is the interpretation of the English law by such cele

brated scholars of that law as Sir Patrick Devlin and Glanville

Williams. See note 18 supra. We recognize that some American

commentators have purported to find a warrant for detention with

out probable cause in the old English books. E.g., Kuh, supra, note

15. But the authorities upon which they rely, principally Lawrence

v. Hedger, 3 Taunt. 14, 128 Eng. Rep. 6 (C. P. 1810) ; 2 H ale,

Pleas of the Crown 89, 96-97 (1st Amer. ed. 1847); 2 Hawkins,

Pleas oe the Crown 118-132 (8th ed. 1824), entirely fail to sup

port any such principle, as the more careful American studies

make clear. See Leagre, supra, note 15, at 408-411; Comment,

Police Power to Stop, Frisk and Question Suspected Persons, 65

Colum. L. Rev. 847, 851-852 (1965). The Americans who trace

stop-and-frisk to the English books have simply permitted them

selves to be confused by the English use of the term “reasonable

suspicion” which is not the equivalent of the same form of words

used in the Uniform Arrest Act and New York’s stop and frisk

legislation, but is the equivalent of American constitutional “prob

able cause.” Hale makes this clear enough. See 2 Hale, op. cit.

supra 76-86, 110. And see Thomas, Arrest; A General View,

(1966) Grim. L. Rev. 639, and comments following. There does

appear to be in English law some patchwork statutory authoriza

tion for stops and searches without warrant, rather in the nature

of the usual American game-law inspections. Whether probable

20

invariably assumed by this Court to describe the constitu

tional law of the Fourth Amendment.36 This is more than

historical happenstance. For the root notion of “probable

cause” which is mainstay of the model is not simply a long

cherished Anglo-American symbol of individual liberty.

It is, in view of the practical realities of criminal adminis

tration, an inevitable evolutionary product of our system’s

use of courts to confine police power within reasonable

bounds consistent with the conscience of a free people. * 36

cause is required for these is not wholly clear, but it seems to be,

see Thomas, The Law of Search and Seizure; Further Ground for

Rationalisation, (1967) Crim. L. Rev. 3, 11-18, and comments fol

lowing. In any event, the statutes are of very limited scope, as

Glanville Williams has noted. Williams, supra, note 18, at 414.

36 Brinegar v. United States, 338 U. S. 160 (1949); Henry v.

United States, 361 U. S. 98 (1959) ; Rios v. United States, 364 U. S.

253 (1960). Brinegar explicitly repudiates the grounds of deci

sion of the lower courts in that case, purporting to authorize an

automobile stop not amounting to a search on reasonable suspicion

not amounting to probable cause. The Henry decision is plainly

based on the same rejection of the same conception. (We can

hardly believe that the Solicitor General’s concession as to the

point of arrest in Henry was dispositive of the view the Court

took of the matter.) And Rios cannot possibly be read as anything

but a repudiation of stop and frisk. Although the force of the

decision has been slighted by some, e.g., A merican* Law Institute,

Model Code of Pre-Arraignment Procedure, Commentary on

§ 2.02, Tentative Draft No. 1, March 1, 1966, at p. 94, the Rios

opinion is not comprehensible on any other theory. The Govern

ment argued at length in Rios for the recognition of a power of

limited detention without arrest or probable cause. The Court’s

opinion was written to identify for the lower court on remand the

issues posed for its factual resolution. Those issues were, simply,

when there occurred an arrest and whether at that time the ar

resting officers had probable cause. These are the issues framed

by the Classical Arrest-Search Model, with its two categories of

police powers—those given officers with probable cause (including

arrest), and those given officers without. If the Court had

imagined that the Stop-Frisk Model presented an alternatively

permissible way of viewing the case, it is simply inconceivable

that its opinion would not have identified for the district court the

quite distinct issues (involving several degrees of detention, with

several accompanying states of justification) posed by that model.

21

II.

The Genius o f Probable Cause.

Whatever uncertainties there may he in the pre-Con-

stitutional history37 and the post-Constitutional evolution

of the Fourth Amendment, two core conceptions of the

Amendment emerge with indisputable clarity. First, the

Amendment’s purpose is to restrict the allowance of in

trusive police investigative powers to circumstances of

particularized justification, disallowing police discretion

to employ those powers against the citizenry in general.

Second, this restriction is enforced by the interposition

of judicial judgment between the police decision to intrude

and the allowability of intrusion.

The first conception is visible upon the face of the Amend

ment. It is the essential idea that gives meaning both to

the requirement of “ probable cause” and to the require

ment of warrants “particularly describing” the place to be

searched, and the things or persons to be seized. Concern

ing both the occasions and extent of police intrusion upon

the individual, “ nothing is left to the discretion of the

officer. . . . ” Berger v. New Y ork ,------U. S. --------, ------ ,

87 S. Ct. 1873, 1883 (1967), quoting Marron v. United

States, 275 TJ. S. 192, 196 (1927).

37 The history is canvassed in the Stanford and Marcus decisions

cited supra, note 6 , and in Landynski, Search and Seizure and

the Supreme Court: A Study in Constitutional Interpreta

tion (Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political

Science, ser. 84, no. 1) 19-48 (1966); Lasson, The H istory and

D evelopment of the F ourth A mendment to the United States

Constitution (Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and

Political Science, ser. 40, no. 2) 13-105 (1937) ; Fraenkel, Concern

ing Searches and Seizures, 34 Harv. L. Rev. 361 (1921).

22

History tells ns why. The general warrants and writs of

assistance against which the Fourth Amendment was

principally aimed were vicious precisely because they “per

mitted the widest discretion to petty officials.” 38 “ Armed

with their roving commission, they set forth in quest of un

known offenders; and unable to take evidence, listened to

rumors, idle tales, and curious guesses. They held in their

hands the liberty of every man whom they pleased to sus

pect.” 39 This practice was doubly damnable. In a society

profoundly committed to the liberty of the subject, the

notion that government should be given the power to in

trude indiscriminately and at the mere will of its officers

into the affairs of every citizen was wholly unacceptable.

Neither the random visitations of the King’s messengers

nor the practice in its more terrifying forms as an increas

ingly powerful bureaucracy might develop it—such as the

South African “ blitz” described in note 11 supra—were to

be countenanced in this free country. Government could

not invade the province of Everyman. To further its im

portant purposes, including criminal investigation, it might

invade the provinces of some individual men, but only

those whom circumstances sufficiently distinguished from

the generality of men so that the invasion could not be

broadside.40 The general warrant infringed this concern

38 Fraenkel, supra, note 37, at 362.

39 Stanford v. Texas, 379 U. S. 476, 483 (1965), quoting 2 Mat ’s

Constitutional H istory of E ngland 246 (Amer. ed. 1864).

40 See Patrick Henry in the Virginia Convention, 3 Elliot’s

Debates 588 (2d ed. 1836) :

“I feel myself distressed, because the necessity of securing

our personal rights seems not to have pervaded the minds of

men; for many other valuable things are omitted:—for in

stance, general warrants, by which an officer may search sus

pected places, without evidence of the commission of a fact,

23

and was accordingly denounced as a “ ‘ridiculous warrant

against the whole English nation.’ ” 11

In addition, the unbounded discretion allowed under the

general warrants and writs of assistance left government

officers free to heed every urging of personal spite, paltry

tyranny, arbitrariness and discrimination. “ In effect, com

plete discretion was given to the executing officials; in the

words of James Otis, their use ‘placed the liberty of every

man in the hands of every petty officer.’ ” 41 42 “ The right of

privacy was deemed too precious to entrust to the discretion

of those whose job is the detection of crime and the arrest of

criminals. Power is a heady thing, and history shows that

the police acting on their own cannot be trusted.” 43 So

the Fourth Amendment was designed both to delimit the

breadth of power and to constrain the possibility of

its abuse. Its language sometimes speaks obscurely in the

context of twentieth century circumstances, “but this much

is certain: there is no authority [in any American gov

or seize any person without evidence of his crime, ought to be

prohibited. As these are admitted, any man may be seized,

any property may be taken, in the most arbitrary manner,

without any evidence or reason. Every thing the most sacred

may be searched and ransacked by the strong hand of power.

We have infinitely more reason to dread general warrants

here than they have in England, because there, if a person

be confined, liberty may be quickly obtained by the writ of

habeas corpus. But here a man living many hundred miles

from the judges may get in prison before he can get that

writ.”

For a brilliant modern expression of the same concern, with par

ticular reference to police street interrogation, see Reich, Police

Questioning of Law Abiding Citizens, 75 Y ale L. J. 1161 (1966).

41 Stanford v. Texas, 379 U. S. 476, 483 (1965), quoting 2 Mat ’s

Constitutional H istory op England 247 (Amer. ed. 1864).

42 Marcus v. Search Warrant, 367 U. S. 717, 729 n. 2 2 (1961),

quoting Tudor, Life of James Otis 6 6 (1823).

43 McDonald v. United States, 335 U. S. 451, 455-456 (1948).

24

ernment] for the molestation of all those on whom the

long shadow of suspicion falls in the hope that something

damaging might turn up in the course of the search.” 44

Not surprisingly, these concerns of the Fourth Amend

ment converge with others that our society has found essen

tial and given enduring constitutional expression. They

deserve to be recalled here, because all are threatened by

the Stop-Frisk Model of criminal investigative process.

The Fifth Amendment Privilege also forbids government

to treat suspicion as guilt and to throw upon the citizen

the obligation to exculpate or explain himself to a govern

ment officer. Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U. S. 436 (1966).

It denies government power to employ coercive force of

any sort (be it brief or extended physical restraint or other

means of compulsion) to secure the cooperation of the

citizen in pursuing law enforcement efforts that may secure

his own criminal conviction. Ibid. Lessons to which the

First Amendment and the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth

and Fourteenth respond have taught us the impermissibility

of making law enforcement officers the unconstrained rulers

of the streets. Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382 IT. S. 87

(1965).45 And our especial national history has given

44 Landynski, op. cit. supra, note 37, at 46.

45 “Literally read, . . . the second part of this ordinance says

that a person may stand on a public sidewalk in Birmingham

only at the whim of any police officer of that city. The con

stitutional vice of so broad a provision needs no demonstra

tion. It ‘does not provide for government by clearly defined

laws, but rather for government by the moment-to-moment

opinions of a policeman on his beat.’ Cox v. Louisiana, 379

U. S. 536, 579 (separate opinion of Me. J ustice Black). In

stinct with its ever-present potential for arbitrarily suppress

ing First Amendment liberties, that kind of law bears the

hallmark of the police state.” Id. at 90-91.

See also Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496 (1939) ; Thornhill v. Ala

bama, 310 XL S. 8 8 (1940); Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536 (1965).

25

us the Equal Protection Clause as a bulwark both against

arbitrary and discriminatory abuses of our citizens by

government officials,46 and against the dangerous gener

ality of governmental authorizations rife with the potential

for such abuses.47

But the Fourth Amendment, most specifically addressed

to protecting these concerns where they may be threatened

by powers exercised in the investigative process, provides

its own singular procedural mechanism for the neces

sary accommodation of individual privacy and investiga

tion. That mechanism is judicial review of the police justi

fication offered to support an investigative intrusion. Time

and again this Court has repeated the theme:

“ The point of the Fourth Amendment, which often

is not grasped by zealous officers, is not that it denies

law enforcement the support of the usual inferences

which reasonable men draw from evidence. Its pro

tection consists in requiring that those inferences be

drawn by a neutral and detached magistrate instead