Abernathy v. Alabama Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Abernathy v. Alabama Brief for Petitioners, 1964. 41e31aba-ab9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f398f83c-997d-4ade-8d6d-cfc53024c034/abernathy-v-alabama-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

T /L

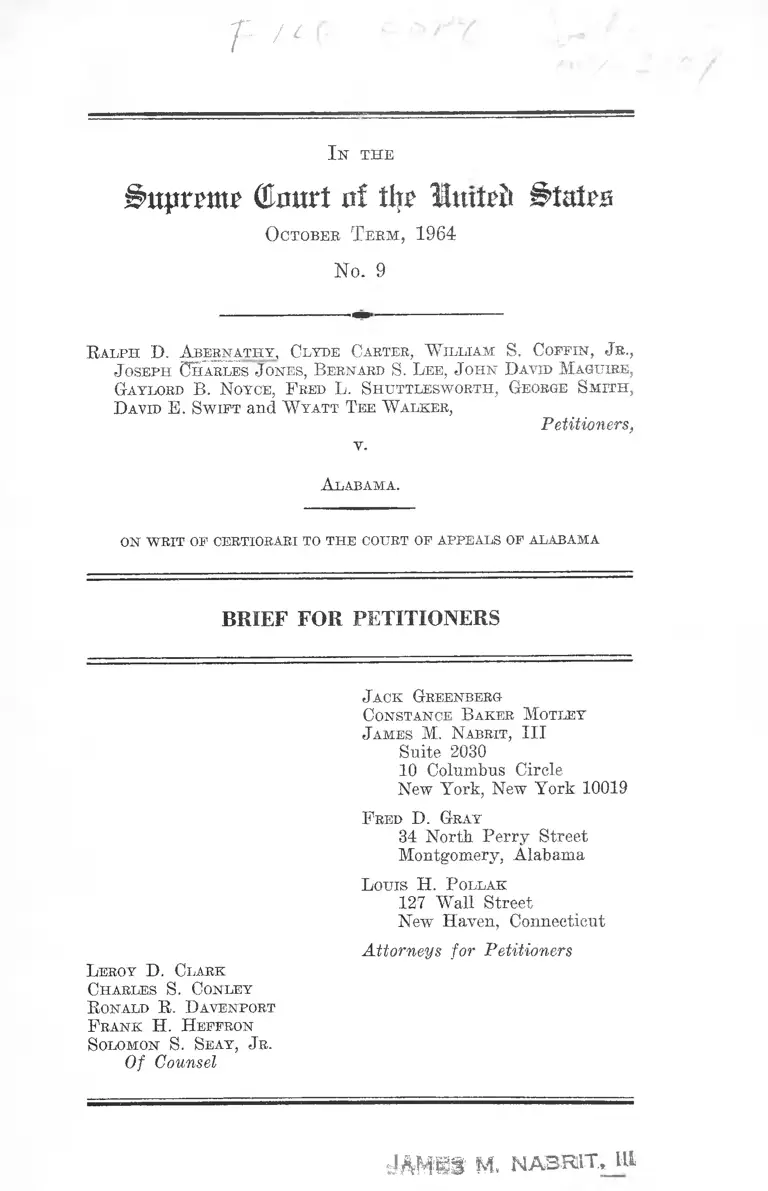

I n th e

i^uprmT (to rt of tip Utttfrik &Mzb

O ctober T erm , 1964

No. 9

Ralph D. Abernathy, Clyde Carter, W illiam S, Coffin, J r.,

J oseph Charles J ones, Bernard S. Lee, J ohn David Maguire,

Gaylord B. Noyce, F red L. Shuttlesworth, George Smith ,

David E. Swift and W yatt Tee Walker,

Petitioners,

v.

Alabama.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE COURT OF APPEALS OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

J ack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

F red D. Gray

34 North Perry Street

Montgomery, Alabama

Louis H. P ollak

127 Wall Street

New Haven, Connecticut

Attorneys for Petitioners

Leroy D. Clark

Charles S. C-onley

Ronald R. Davenport

F rank H. H effron

Solomon S. Seay, J r.

Of Counsel

WAMBi' M. NABRIT.* Ills

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion Below ...... ..........................-.........................—- 1

Jurisdiction ...................- ....-..................................-...... 1

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved...... 2

Questions Presented .............. ..... ............ -...................... 3

Statement ................................................. -................—- 4

Summary of Argument .............................. - .................. H

A rgum ent :

I. Petitioners’ Criminal Convictions Were Based

on No Evidence of Guilt....................................... 12

II. The Conviction of the Petitioners on the Basis of

State Statutes Which, as Construed and Applied,

Are Vague, Indefinite, and Uncertain, Violates

the Petitioners’ Bights Under the Due Process

^Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment ............... 16

III. The Arrests and Convictions of Petitioners Con

stitute Enforcement by the State of the Practice

of Bacial Segregation in Bus Terminal Facilities

Serving Interstate Commerce, in Violation of the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment, and 49 U. S. C. §316(d), and a Bur

den on Commerce in Violation of the Commerce

Clause ................................................................... 21

IV. The Decision Below Conflicts With Decisions of

This Court Securing the Fourteenth Amendment

Bight to Freedom of Expression, Assembly and

Beligion....... ...................................-...................... 23

11

PAGE

V. The Court Below Deprived Petitioners of Due

Process and Violated the Supremacy Clause by

Refusing to Accept the Federal District Court

Determination That Petitioners Were Arrested

to Enforce Racial Segregation ............................ 25

Conclusion ....................................................................................... 27

T able oe C a ses :

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31 ............................ -12, 22

Barr v. City of Columbia, —— U. S. ——, 12 L. ed. 2d

766 .............................................................................. 14,15

Bigelow v. Old Dominion Copper, 225 U. S. I l l .......... 26

Bouie v. City of Columbia, -----U. S. —— , 12 L. ed.

2d 894 ........................................................................... 17

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454 ................. 12, 22, 23, 25

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 .............................. 14

Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495 .............................. 23

Connally v. General Const. Co., 269 U. S. 385 .......... 17

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ....................................... 14

Deposit Bank v. Board of Councilmen of Frankfort,

191 U. S. 499 ............................................................ 27

EdwTards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 ................. 24

Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S. 4 4 ........................ 24

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 ................. 14,15, 23, 24

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 ................................12, 22

Henry v. Rock Hill,------ II. :S. ----- , 12 L. ed. 2d 79 .... 24

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 ............................ 18

Hoag v. New Jersey, 356 U. S. 464 ............................ 26

U1

PAGE

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451 ..................— 17

Lewis v. Greyhound Corp., 199 F. Supp. 210 (M. D.

Ala. 1961) .................................. ...............6,12,21,25,27

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 IT. S. 267 ............. .... ........... 22

Mitchell v. State, 41 Ala. App. 254, 130 So. 2d 198 (Ala.

App. 1961), cert, denied, 130 So. 2d 205 (Ala. Sup.

Ct.) ........................ - ........................................ ........... 16

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. -S. 373 ............... ................ 23

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 IT. S. 449 ............................ 23

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 ....... ................. 22

Pierce v. United States, 314 U. S. 306 ........ ..... ... ....... 18

Raley v. Ohio, 360 U. -S. 423 ......................................... 17

Rochin v. California, 342 U. S. 165............................. . 20

Sherman v. United States, 356 U. S. 369 ................. 20

Southern Pacific Railroad v. United States, 168 U. S.

1 ......... ............................................ ........................... 26

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ...................19, 24

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154 ............................15, 22

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 ........... .................. . 19

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199.........................14,15

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 ............................ 23

United States v. L. Cohen Grocery, 255 U. S. 81.......... 17

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 ........... 14

Williams v. North Carolina, 317 U. S. 287 ............ 19

Wolfe v. North Carolina, 364 U. S. 177 ......................... 25

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 ................. —.14,15,18, 22

Yates v. United States, 354 U. S. 298 ........................ 26

IV

S ta tu t e s :

PAGE

U. S. Const., Art. 1, Sec. 8 ................................... 2, 21, 23

TJ. S. Const., Art. 6, par. 2 .......................................... 2, 25

IJ. S. Const., Amendment 1 .................................... 2,4, 23

U. S. Const., Amendment 14 ............................ 2, 3,15,16,

21, 22, 23, 25

28 IT. S. C. §1257(3) .................................................... 1

28 IT. S. C. §2283 ........................................................6,11

49 U. S. C. §316 (d) ..............................................3,21,23

Ala. Code, Tit. 14, §119(1) (Supp. 1961) ...... 2,4,12,13,16

Ala. Code, Tit. 14, §407 (1958) ................................2, 4,14

Ala. Code, Tit. 15, §363 (1958) ................................... 9

Ot h e r A u t h o r it y :

Restatement of Judgments, Section 68(1) ................. 25

I n t h e

kapron* ©curt of % lotted l̂ fatFB

O ctober T erm , 1964

No. 9

R a lph D. A bernathy , Clyde Carter, W illiam S. Co e fin ,

J r ., J oseph Charles J ones, B ernard S. L ee , J ohn D avid

M aguire, Gaylord B. N oyce, F red L . S hu ttles w orth ,

George S m it h , D avid E. S w ift an d W yatt T ee W alker,

Petitioners,

Alabama.

O N W R IT OF CERTIO RA RI TO T H E COU RT o f A PPEA LS o f ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

O pin ion B elow

The opinion of the Court of Appeals of Alabama in

Abernathy v. Alabama (R. 237) is reported at 155 So. 2d

586. The Court of Appeals rendered no opinion in the

other ten cases but affirmed the convictions on the authority

of the Abernathy case (R. 288, 329, 372, 666, 415, 458, 499,

541, 583, 624).

Jurisd iction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals of Alabama in

each of these cases was entered on October 23,1962 (R. 236,

288, 329, 372, 666, 415, 458, 499, 541, 583, 624). Rehearing

was denied on November 20,1962 (R. 248, 289, 330, 373, 667,

2

416, 459, 500, 542, 584, 625). The Supreme Court of Ala

bama denied certiorari on July 25, 1963 (R. 254).

The jurisdiction of this Court in each of these cases is

invoked pursuant to Title 28, United States Code, Section

1257(3), petitioners having asserted below and asserting

here deprivation of rights secured by the Constitution of

the United States.

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved

Each of these cases involves Article I, Section 8 (com

merce clause) and Article VI, paragraph 2 (supremacy

clause), of the Constitution of the United States. Each

case also involves the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

Each petitioner was convicted under Code of Alabama,

Title 14, Section 407 (1958):

If two or more persons meet together to commit a

breach of the peace, or to do any other unlawful act,

each of them shall, on conviction, be punished, at the

discretion of the jury, by fine or imprisonment in the

county jail, or hard labor for the county, for not more

than six months.

Every petitioner except Walker was also convicted un

der Code of Alabama, Title 14, Section 119(1) (Supp.

1961):

Any person who disturbs the peace of others by vio

lent, profane, indecent, offensive or boisterous conduct

or language or by conduct calculated to provoke a

breach of the peace, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor,

and upon conviction shall be fined not more than five

hundred dollars ($500.00) or be sentenced to hard

labor for the county for not more than twelve (12)

months, or both, in the discretion of the Court.

3

Each case also involves Title 49, United States Code,

Section 316(d):

. . . It shall be unlawful for any common carrier by

motor vehicle engaged in interstate or foreign com

merce to make, give, or cause any undue or unreason

able preference or advantage to any particular person,

port, gateway, locality, region, district, territory, or

description of traffic, in any respect whatsoever; or

to subject any particular person, port, gateway, lo

cality, region, district, territory, or description of

traffic to any unjust discrimination or any undue or

unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage in any respect

whatsoever: . . . .

Q uestions Presented

I. Were petitioners denied due process of law under the

Fourteenth Amendment in that their criminal convictions

for breach of the peace and unlawful assembly were based

on no evidence of guilt f

II. Were petitioners’ rights under the due process clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment denied because their convic

tions for breach of the peace and unlawful assembly were

based on state statutes which, as construed and applied, are

vague, indefinite, and uncertain!

III. Did the arrest and conviction of petitioners on

charges of breach of the peace and unlawful assembly con

stitute enforcement by, the state of the practice of racial

segregation in bus terminal facilities serving interstate

commerce, thus violating petitioners’ rights under the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the com

merce clause, and 49 U. S. C. §316 (d) ?

4

IV. Were the petitioners denied their rights under the

due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, as that

clause incorporates the First Amendment’s protection of

freedom of expression, assembly, and religion?

V. Were the petitioners denied their rights under the

supremacy clause of the Constitution in that the courts of

Alabama tried and convicted petitioners on charges which

a United States District Court had already determined were

intended to perpetuate racial segregation ?

Statement

In the spring of 1961 a wave of civil rights demonstra

tions known as ‘‘Freedom Rides” swept the south. Their

purpose was to demonstrate to the country that Negro trav

elers very often did not enjoy equal rights secured by the

law (R. 36, 185). The “Freedom Riders” were in a number

of places greeted with violence, intimidation and arrest.

Seven of the petitioners in the case at bar were “Freedom

Riders” (R. 185). The remaining four petitioners sat with

the seven, their friends, at a lunch counter in the Trailways

Bus Terminal in Montgomery, Alabama (R. 188).

Petitioners were arrested and convicted for (1) conduct

calculated to provoke a breach of the peace (Ala. Code,

Tit. 14, §119(1) (Supp. 1961)) and (2) unlawful assembly

(Ala. Code, Tit. 14, §407 (1958)). Five petitioners, William

S. Coffin, Jr., University Chaplain of Yale University, John

Maguire, Professor of Religion at Wesleyan University,

Professor Gaylord Noyce of Yale University, David Swift,

Professor of Religion at Wesleyan University, all of whom

are white, and George Smith, law student at Yale Uni

versity, a Negro, left New Haven, Connecticut for New

York on May 23, 1961 (R. 180-82, 184). From New York

they took a flight to Atlanta, Georgia and spent the night

5

in Atlanta (E. 182, 184). The following morning they took

the Greyhound Bus to Montgomery, Alabama (R. 184). The

five were joined in this trip by petitioners Clyde Carter and

Joseph Charles Jones, theological students from North

Carolina, both of whom are Negroes (R. 184). All seven

arrived in Montgomery on Wednesday, May 24th (R. 184).

Upon, arrival they proceeded directly to the home of

petitioner Rev. Ralph D. Abernathy (R. 206). Although

there was a large crowd gathered when they arrived at the

Greyhound Bus Terminal, there wms very little disturbance

as they drove from the Terminal to his home (R. 206). The

next morning, Thursday, May 25th, the seven decided to go

on to Jackson, Mississippi (R. 184) and were accompanied

to the Trailways Bus Terminal by petitioners Abernathy,

Wyatt Walker, Fred Shuttlesworth, all ministers, and Ber

nard Lee, a theological student; all of these petitioners are

Negroes (R. 186). By prearrangement they contacted the

state military authorities before leaving (R. 143). Peti

tioners were escorted by heavily armed state military con

voy to the rear of the Trailways Bus Terminal, where they

were ushered into the white waiting room by military

guards standing at the door (R. 186). Upon entering the

white waiting room petitioners planning to travel to Jack-

son immediately went to the ticket window and purchased

tickets (R. 188). Petitioner Walker went to make a phone

call (R. 131). After the tickets were purchased, several of

the petitioners sat down at the lunch counter located in the

white waiting room (R. 188). Sheriff Mac Sim Butler there

upon arrested petitioners because he was instructed to do so

by Colonel Poarch, Staff Judge Advocate, 31st Division of

the Alabama National Guard (R. 91, 96).

At the time of arrest, according to Sheriff Butler, some

four to five hundred persons were outside the terminal and,

not counting the petitioners, approximately 30 persons were

6

inside—12 of whom were law enforcement officials (R. 84).

Butler did not ask the petitioners to leave or to refrain

from any alleged provocative conduct, nor did he hear any

one else ask the petitioners to leave (R. 103). He did not

see petitioners engage in obscene, boisterous, or indecent

conduct (E. 105, 106). And he knew that two previous

“Freedom Rider” groups had used the facilities of the

terminal without being arrested (R. 102).

On the day of the petitioners’ arrests, Rev. Abernathy,

along with several others, instituted an action seeking to

enjoin the arrest of persons using interstate transportation

facilities in Montgomery on a desegregated basis (R. 35,

36). The Attorney General of Alabama and the Circuit

Solicitor for the Fifteenth Judicial Circuit (encompassing

Montgomery) were defendants (R. 35). Immediately after

their arrests, the other ten petitioners filed a motion to

intervene in the federal court action, which was granted

May 26, 1961. Lewis v. Greyhound Corp., 199 F. Supp. 210,

213. Petitioners sought an injunction against the state

court criminal proceedings arising out of their arrest, but

Judge Johnson dismissed the action as to the arrests of

petitioners on the ground that 28 U. S. C. §2283 “precludes

the granting of such relief.” He stated:

. . . I want you to understand that the court does not

find or believe that the arrest of these individuals

against whom these criminal proceedings are now land

ing was for any purpose other than to enforce segrega

tion. As a matter of fact, in the posture of the case,

the court is of the opinion that the arrest of those indi

viduals was for the purpose of enforcing segregation

in these facilities (R. 14).

At petitioners’ trial, Sheriff Butler testified that a riot

had occurred when the first group of “Freedom Riders”

7

arrived in Montgomery, May 20, 1961. On the day follow

ing, May 21, 1961, the Governor declared martial law (R.

86). That same day a hostile, predominantly white crowd

of well over a thousand persons congregated near the

church of petitioner Abernathy (R. 89).

Floyd Mann, the Director of Public Safety for the State

of Alabama, testified that on Saturday, May 20th, when the

first group of Freedom Riders arrived, he saw fist fights

between members of the press and private persons and

between white and colored persons (R. 121). Between the

date of the first riot and the arrest, a Negro minister was

shot (R. 124). However, when the petitioners arrived at

the Trailways Terminal, there were at least a hundred or

more soldiers outside the terminal as well as thirty-five

members of Mann’s department along with several motor

cycle officers of the local police department (R. 129). The

Director of Public Safety was of the opinion that the crowd

outside the terminal was under control at the time of the

arrest (R. 130).

Colonel Poarch estimated the number of persons within

the terminal at thirty-five to fifty and the crowd outside at

three hundred (R. 139, 140). After the military had es

corted petitioners to the terminal, he noticed three white

“toughs” pouring coffee on the seats of the luncheon coun

ter. As they were not interstate or intrastate travelers, he

ordered them out of the station, but he did not arrest them

even though their conduct was in his opinion, “calculated to

provoke a breach of the peace” (R. 140, 147). Poarch

thought it was necessary to arrest the petitioners “Because,

as I have stated, the air was electric with excitement and

tension, there were three hundred people outside the sta

tion who were hostile to these persons.” But he admitted

that he had not attempted to determine the mood of the

crowd outside (R. 154).

8

General Graham of the Alabama National Gnard ordered

Colonel Poarch to order the arrest of the petitioners be

cause they were acting contrary to community custom (R.

219). He also testified that there were several hundred mil

itary personnel on duty outside the terminal (R. 228).

After the arrest Sheriff Butler swore out a warrant and

affidavit which alleged that each petitioner

. . . did disturb the peace of others by violent, profane,

indecent, offensive or boisterous conduct or language

or conduct calculated to provoke a breach of the peace

in that he did come into Montgomery, Alabama, which

was subject to martial rule and did wilfully and inten

tionally attempt to test segregation laws and customs

by seeking service at a public lunch counter with a

racially mixed group, during a period when it was

necessary for his own safety for him to be protected

by military and police personnel and when the said

lunch counter building was surrounded by a large num

ber of hostile citizens of Montgomery (emphasis sup

plied) (R. 1).

and that each petitioner

. . . did meet with two or more persons to commit a

breach of the peace or to do an unlawful act, against

the peace and dignity of the State of Alabama. (Ibid.)

The eleven petitioners were tried and convicted on Sep

tember 15, 1961, in the Court of Common Pleas of Mont

gomery County for both breach of the peace and unlawful

assembly (R. 3). Walker was sentenced to 90 days in jail,

and the others were sentenced to 15 days in jail with fines of

$100 and costs (R. 594).

9

An appeal was taken to the Circuit Court of Montgomery

County1 where the petitioners were tried on the basis of

the Solicitor’s Complaint which charged that each peti

tioner2

. . . did disturb the peace of others in Montgomery,

Alabama, at a time when said city and county were

under martial rule as a result of the outbreak of racial

mob action, by conduct calculated to provoke a breach

of the peace, in that he did wilfully and intentionally

seek or attempt to seek service at a public lunch coun

ter with a racially mixed group, at which time and place

the building housing said lunch counter was surrounded

by a large number of hostile citizens of Montgomery,

Alabama, and it was necessary for his own safety for

him to be protected by military and civil police per

sonnel (emphasis supplied) (R. 4).

and that each petitioner

. . . did meet with two or more persons to commit a

breach of the peace or to do an unlawful act, in that

he did meet with two or more persons in Montgomery,

Alabama, at a time when said city and county were

under martial rule as a result of the outbreak of racial

mob action, for the purpose of wilfully and intention

ally seeking or attempting to seek service at a public

lunch counter with a racially mixed group at which

time and place the building housing said lunch counter

was surrounded by a large number of hostile citizens

of Montgomery, Alabama, and it was necessary for his

1 Under Alabama procedure, trial in the Circuit Court is de novo,

and proceedings are begun bv a Solicitor’s Complaint (Ala. Code,

Tit. 15, §363) (1958).

2 In the Circuit Court petitioner Walker was charged only with

unlawful assembly (R. 594).

10

own safety for him to be protected by military and

police personnel, against the peace and dignity of the

State of Alabama (emphasis supplied) (Ibid.).

The eleven cases were consolidated for trial, but a sepa

rate judgment was entered in each (R. 81), Each peti

tioner was convicted, fined $100 and sentenced to 30 days

at hard labor (R. 234). Appeal was taken to the Court of

Appeals of Alabama. Only the Abernathy record contained

the transcript of trial in the Circuit Court, but pursuant to

stipulation (R. 59) the Court of Appeals considered the

transcript a part of the record in each of the other cases.

The Court of Appeals, by a two to one decision, affirmed

each judgment of conviction and rehearing was denied.

Judge Cates, in dissent, stated that the State failed to prove

beyond a reasonable doubt a “clear and imminent danger

of breach of the peace,” because there was no proof to his

satisfaction that the sitting down at the lunch counter

caused the crowd to gather. Nor was there any evidence

of an assault upon a militiaman (R. 246). The Supreme

Court of Alabama denied certiorari (R. 254).

The Trailways Bus Terminal in Montgomery is “leased

by several interstate carriers including Capitol Motor

Lines and is subleased by them to an ‘agent,’ R. E. McRae,

executive official of Capitol Motor Lines. The lunch coun

ter portion of the terminal is leased by the . . . carriers to

the Interstate Co., a Delaware Corporation, which in turn

leases the lunch counter portion of the terminal to Southern

House, Inc., which operates the lunch counter portion of the

terminal . . . ” (R. 61).

11

Sum m ary o f Argum ent

The convictions of the petitioners for breach of the peace

and unlawful assembly were based on no evidence of guilt.

Petitioners were at all times polite, quiet, and peaceful.

There is no evidence of any wrongdoing on their part.

A breach of peace conviction cannot be sustained merely

because hostile observers are present. As the convictions

for breach of the peace must fail for lack of evidence, so

too must the convictions for unlawful assembly based on

the alleged breach of the peace.

The breach of the peace and unlawful assembly statutes,

as construed and applied to petitioners, are unconstitution

ally vague. The breach of the peace statute afforded peti

tioners no fair warning that it proscribed their acts. As

applied to petitioners the statute punishes constitutionally

protected conduct, and allows the police unfettered discre

tion to determine when an offense has been committed.

For the same reasons the unlawful assembly statute, as

construed and applied, deprives petitioners of due process

of law.

The act of police and military authorities of escorting

petitioners to the terminal and then arresting them without

warning constitutes an entrapment.

Petitioners were arrested to enforce the state’s custom of

segregation. Their right to use the facilities of the termi

nal free of state enforced racial discrimination was pro

tected by the commerce clause and 49 U. S. C. §316(d), as

well as by the Fourteenth Amendment. Therefore the deci

sion of the lower court cannot stand.

The conviction of the petitioners of breach of the peace

and unlawful assembly conflicts with previous decisions of

this Court protecting the right of freedom of expression,

12

assembly, and religion. The petitioners believed in the

right of all persons to travel without discrimination; while

peacefully expressing this belief they were arrested. Their

protest is constitutionally protected and therefore their

convictions must fail.

In Lewis v. Greyhound Corp., 199 F. Supp. 210, Judge

Johnson determined that petitioners were arrested to en

force the state’s custom of segregation. Since that deter

mination was made prior to the trial of the petitioners in

the state Circuit Court, the state court was estopped from

reaching a different conclusion.

A R G U M E N T

I. P etition ers’ Crim inal C onvictions W ere Based on

N o Evidence o f Guilt.

A. Breach o f the Peace

The Solicitor’s Complaint filed in the Circuit Court of

Montgomery charged, under Title 14, Section 119(1) of the

Alabama Code, that each petitioner engaged in “conduct

calculated to provoke a breach of the peace, in that he did

wilfully and intentionally seek or attempt to seek service

at a public lunch counter with a racially mixed group . . . ”.

However, “It is settled beyond question that no state may

require racial segregation of interstate or intrastate trans

portation facilities. The question is no longer open; it is

foreclosed as a litigable issue.” Bailey v. Patterson, 369

U. S. 31; Boynton v. Virginia, 364 IT. S. 454; Gayle v.

Browder, 352 U. S. 903.

The State argued that the use of the facilities by peti

tioners in the “explosive” situation that existed in Mont

gomery was an abuse of the petitioners’ constitutional

rights and therefore subject to criminal sanctions. It in-

13

traduced testimony that hostile observers presented a

threat of violence (R. 117, 139), that violence had occurred

within the previous week (E. 84, 85), that the air was elec

tric with excitement (R. 141), that a few white “toughs”

had poured coffee on the counter seats (R. 140), that an

“outburst” was heard when petitioners sat down (R. 105),

and that military and civilian authorities believed that

arrests were necessary to preserve the peace (R. 141, 147).

However, this evidence even when viewed most favorably to

the State, did not establish that petitioners had committed a

breach of the peace.

The breach of the peace statute, Tit. 14, §119(1), con

demns conduct which disturbs the peace of others and is

‘“violent, profane, indecent, offensive or boisterous” or

J “calculated to provoke a breach of the peace.” The State

did not contend that petitioners were violent, profane, or in

any way offensive (R. 105). Nor did the testimony elicited

by the State support its contention that the sitting of peti

tioners at the lunch counter either disturbed the peace of

anyone or was calculated or designed to provoke a breach

of the peace.

Although violence had ensued upon the arrival of the

first group of Freedom Riders on May 20th, two groups

of Freedom Riders used the facilities of the Trailways

terminal without interference from the police on the day

before petitioners’ arrests (R. 102). The petitioners were

provided with an armed military escort to the terminal

(R. 185). Approximately eighteen soldiers inside and over

one hundred outside controlled the crowd which, under the

most generous estimates, did not exceed five hundred (R.

129, 84). With the exception of an alleged “outburst” (R.

105), there was not a single incident of violence or unruly

conduct outside the terminal.

14

In these circumstances, petitioners were justified in be

lieving that their right to request service at the lunch coun

ter would be protected. The record establishes without con

tradiction that petitioners were orderly at all times and

innocent of any wrongful conduct. They were not warned

to remain away from the counter. When they sat down,

they were not even asked to withdraw, but were summarily

arrested.

Thus the conviction of petitioners for breach of the peace

is based on no evidence of guilt and Thompson v. Louis

ville, 362 U. S. 199, applies. Mere evidence that the pres

ence of peaceful Negro and white persons sitting at a lunch

counter might move onlookers to commit acts of violence

is insufficient to support a conviction for breach of the

peace. Barr v. City of Columbia,----- U. S. •—-—, 12 L. ed.

2d 766.

Even assuming that a volatile situation did exist, peti

tioners cannot be punished for the innocent assertion of

fundamental constitutional rights. “ [T]he possibility of

disorder by others cannot justify exclusion of persons from

a place if they otherwise have a constitutional right

(founded upon the Equal Protection Clause) to be pres

ent.” Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284, 293. See also

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 27; Buchanan v. Warley, 245

U. S. 60; Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157; cf. Watson

v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526, 535 (“constitutional

rights may not be denied simply because of hostility to their

assertion or exercise”).

B. Unlawful Assem bly

Title 14, Section 407 of the Alabama Code makes it a

crime when “two or more persons meet together to com

mit a breach of the peace, or to do any other unlawful

act. . . . ” Clearly, there is no evidence that petitioners

15

met together to commit a breach of the peace, as that term

is normally understood.3 Petitioners were at all times or

derly and did no more than exercise an undisputed con

stitutional right. Moreover, there is no evidence whatever

of the commission of any other unlawful act. Thus the ap

plicability of Thompson v. Louisville, supra, seems undeni

able.

For the same reasons that the breach of peace conviction

must fall, the convictions for unlawful assembly are vulner

able. There simply is no evidence of wrongdoing. As this

Court said in Barr v. City of Columbia,----- U. S. ------ ,

12 L. ed. 2d 766, 769:

. . . [T]he only possible relevant evidence which we

have been able to find in the record, is a suggestion

that petitioners’ mere presence seated at the counter

might possibly have tended to move onlookers to com

mit acts of violence. , . . [BJecause of the frequent

occasions on which we have reversed under the Four

teenth Amendment convictions of peaceful individuals

who were convicted of breach of the peace because of

acts of hostile onlookers, we are reluctant to assume

that the breach-of-peace statute covers petitioners’

conduct here.

See also Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157; Taylor v.

Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154; Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S.

284.

3 The Alabama Court of Appeals’ expansion of the meaning of

“breach of the peace” is challenged infra, Argument II, as a denial

of due process of law.

16

II. The Conviction of the Petitioners on the Basis of

State Statutes Which, as Construed and Applied, Are

Vague, Indefinite, and Uncertain, Violates the Peti

tioners’ Rights Under the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

A. Breach o f the Peace

The breach of the peace statute which was the basis for

the conviction of petitioners provides in part:

Any person who disturbs the peace of others by vio

lent, profane, indecent, offensive or boisterous conduct

or language or by conduct calculated to provoke a

breach of the peace, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor

. . . (Ala. Code, Tit. 14, §119(1) (Supp. 1961)).

In affirming petitioners’ convictions the Alabama Court of

Appeals held, “No specific intent to breach the peace is

essential to a conviction for a breach of the peace. . . .

Nor is it necessary to constitute the offense of a breach

of the peace that the proof show the peace has actually

been broken . . . (R. 245). This holding is contrary to the

plain language of §119(1). No Alabama decisions were

cited in support of this construction of the statute and,

indeed, there were none.4

The Court of Appeals also held that petitioners’ convic

tions could be sustained without any proof of “violent,

profane, indecent, offensive or boisterous” conduct (R.

246). However, the phrase “conduct calculated to provoke

4 The only Alabama ease approaching a construction of the 1959

statute (Tit. 14, §119(1)) is Mitchell v. State, 41 Ala. App. 254,

130 So. 2d 198 (Ala. App. 1961), cert, denied, 130 So. 2d 205

(Ala. Sup. Ct.). In that case a conviction was reversed because

the complaint, which alleged merely that the defendant engaged in

“conduct calculated to provoke a breach of the peace,” was held

to be too vague.

17

a breach of the peace” is extremely difficult to define, and

criminal statutes should be construed narrowly. Any in

terpretation of that phrase that is not closely related to the

types of conduct specifically described is both unreason

able and unforeseeable.

■Criminal laws must explicitly define crimes sought to be

punished so as to give fair notice as to what acts are pro

hibited. As was held in Lametta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S.

451, 453, “no one may be required at peril of life, liberty

or property to speculate as to the meaning of penal stat

utes. All are entitled to be informed as to what crimes are

forbidden.” See also United States v. L. Cohen Grocery,

255 U. S. 81, 89; Connolly v. General Const. Co., 269 IT. S.

385; Raley v. Ohio, 360 IT. S. 423.

Section 119(1), as construed and applied, did not afford

petitioners fair warning. Petitioners did not actually dis

turb the peace of others, as a sound reading of the statute

would require, nor is there any proof that they intended

to do so. Moreover, it was neither alleged nor proven that

petitioners were “violent, profane, indecent, offensive or

boisterous.” Disregarding the fact that petitioners were

engaged in innocent conduct, the Court of Appeals of Ala

bama upheld their convictions by a broad and indefinite

expansion of the phrase “conduct calculated to provoke a

breach of the peace.”

Petitioners had no way of knowing that the statute would

be extended to include their actions. The statute as nar

rowly drawn by the Legislature, lulled them “into a false

sense of security.” Bouie v. City of Columbia,----- U. S.

----- , 12 L. ed. 2d 894, 899. To allow this construction of

the act to cover conduct which a normal reading of it would

not reveal as being violative of its provisions, would be

like applying a new act retroactively.

18

There can be no doubt that a deprivation of the right

of fair warning can result not only from vague statu

tory language but also from an unforeseeable and

retroactive judicial expansion of narrow and precise

statutory language. As the Court recognized in Pierce

v. United. States, 314 TJ. S. 306, 311, “judicial enlarge

ment of a criminal act by interpretation is at war with

a fundamental concept of the common law that crimes

must be defined with appropriate definiteness.” Id. at

899.

Not only did the court surprise defendants by giving the

law a new and broad construction, it also gave the act an

interpretation of undue elasticity. The statutory language

“conduct calculated to provoke a breach of the peace” can

now be used to justify conviction for entirely innocent

conduct whenever others threaten to act unlawfully in re

sponse to that conduct. Where a statute is so vague and

uncertain as to make criminal an utterance or an act which

may be innocently said or done with no intent to induce

resort to violence, a conviction under such a law cannot

be sustained. Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242.

Thus, “this case falls within the rule that a generally

worded statute which is construed to punish conduct which

cannot constitutionally be punished is unconstitutionally

vague to the extent that it fails to give adequate warning

of the boundary between the constitutionally permissible

and constitutionally impermissible applications of the stat

ute.” Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284.

B. U nlawful A ssem bly

The same reasoning and authorities apply to the con

victions for unlawful assembly. Count 2 of the Solicitor’s

Complaint charges that petitioners “did meet with two or

19

more persons to commit a breach of the peace or to do

an unlawful act . . . ” As the petitioners were charged

under the alternative words of the statute, they cannot

know whether the State claims that they met to commit a

breach of the peace or met to commit some other unlawful

act. Assuming for sake of argument, as the petitioners

were convicted of a breach of the peace, that the gravamen

of the crime charged to the petitioners is that they met to

commit a breach of the peace, the conviction for unlawful

assembly still cannot be sustained. Normally breach of the

peace, as is evident from the original affidavit filed by the

sheriff (E. 1) and the complete text of the breach of the

peace statute in Alabama, refers to “violent, profane, in

decent, offensive or boisterous conduct.” There were no

prior constructions of this statute which would have placed

the petitioners on notice that the statute applied to inno

cent activity which might provoke others to unlawful acts

of opposition. Certainly the text of the statute would not

inform petitioners that it was subject to such a construc

tion.

If it is assumed that the gravamen of the petitioners’

crime was that they met to commit some unlawful act, then

the conviction certainly must fall. At all times the acts of

the petitioners were constitutionally protected and therefore

not subject to criminal sanctions. The charge of meeting

to commit any unlawful act fails to provide any warning

that a legally and Constitutionally protected activity—sit

ting in an integrated group at a lunch counter—can be

punished as unlawful.

If either of the statutory clauses is unconstitutionally

vague, the conviction under it must be reversed for it can

not be known which part was relied upon by the trial or

appellate courts. Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359;

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516; Williams v. North Caro

lina, 317 U. 'S. 287.

20

C. E ntrapm ent

Moreover, the conviction of the petitioners on both

charges is further impaired by the fact that their acts were

induced by the authorities. Petitioners were escorted to

the terminal by the military authorities. They were al

lowed to purchase their tickets and to use the “white”

waiting room. They were not warned that their subsequent

act of using the facilities of the lunch counter would pro

voke the crowd outside to violence. Nor were they asked

to leave the counter after they sat down. The military au

thorities’ attitude and actions manifested absolute control

of the situation both inside and outside the terminal. For

the police and military authorities to induce, suggest, or

tacitly approve conduct, and then deem it illegal is in the

nature of an entrapment. Sherman v. United States, 356

U. S. 369. It “offends a sense of justice,” Bochin v. Cali

fornia, 342 U. S. 165, 173, to allow prosecution to follow

in such a situation. “To determine whether entrapment

has been established, a line must be drawn between the

trap for the unwary innocent and the trap for the unwary

criminal.” Sherman v. United States, supra. It is clear

that in the instant ease the court below has so drawn the

line as to include the innocent petitioners who were at all

times engaged in constitutionally protected conduct.

21

III. T he Arrests and Convictions o f P etition ers Con

stitute E nforcem ent by the State o f the Practice o f

R acial Segregation in Bus T erm inal Facilities Serving

Interstate Com m erce, in V iolation o f the Equal Protec

tion Clause o f the Fourteenth A m endm ent, and 4 9

U. S. C. § 3 1 6 ( d ) , and a Burden on Com m erce in V io

la tion o f the Com m erce Clause.

Petitioners were arrested to enforce the state “custom”

of segregation. Judge Johnson so concluded in Lewis v.

Greyho'imd Corp., 199 F. Supp. 210 (M. I). Ala. 1961), and

the record here is clear. The testimony of Sheriff Butler

and General Graham leads unquestionably to the conclu

sion that the law enforcement officials’ act of arresting the

petitioners was part and parcel of the pre-existing state

practice of racial segregation. Both indicated in their tes

timony that the motivating factor in the decision to arrest

petitioners was that the petitioners dared challenge the

state “custom” of segregation.5 And certainly it stretches

5 At the trial of the petitioners in the Circuit Court, Sheriff Mac

Sim Butler, when asked on cross-examination whether or not he

had seen the petitioners do anything, testified:

A. Yes, sir, I did. I saw them do something that 1 thought

might cause a riot.

Q. What was it? A. They came in as a mixed crowd and

immediately sat down and ordered coffee at a white lunch

counter. At that time they were arrested (R. 97).

Later in the cross-examination, counsel questioned the sheriff

about the warrant which was the basis of conviction of the peti

tioners in the lower court.

Q. And just one other question about the warrant. You

further say in this warrant he did wilfully and inten

tionally attempt to test the segregation laws and customs by

seeking service at a public lunch counter with a racially mixed

group. As the chief law enforcement officer of this county, sir,

can you tell us what particular laws you had in mind, if any ?

A. I don’t know what particular code it would be, but I am

sure, lawyer, that you know our lunch stands, cafes and other

places are segregated (R. 106). (continued)

22

the limits of credulity to explain the arrest of peaceful per

sons whereas the white “toughs” who poured the coffee on

the seats of the counter were merely removed from the

station without charges being brought against them.

There can be no question that petitioners were within

their rights in seeking service at the bus terminal lunch

counter. Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31; Boynton v.

Virginia, 364 U. S. 454; Browder v. Gayle, 352 XJ. S. 903;

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154. A state cannot require

eating establishments to segregate or enforce its own pol

icy of segregation by prosecution of those who would chal

lenge segregation. Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244;

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267. Where interstate

transportation facilities are involved, the state’s intrusion

is particularly indefensible. As in Wright v. Georgia, the

command of General Graham to arrest the petitioners was

doubly a violation of petitioners’ Fourteenth Amendment

rights:

It was obviously based, according to the testimony of

the questioning officers themselves, upon their intention

to enforce racial discrimination in the park. For this

reason the order violated the Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment . . .

General Graham, who ordered the arrest of the petitioners, when

asked why he so acted testified as follows:

Q. What was it, General, that led you to conclude that these

defendants should be arrested! A. Well, it was the act of

sitting together as a group contrary to the custom, long estab

lished custom here in this community under the circumstances.

Q. What custom had you in mind, General Graham! A.

White people eat one place and colored eat another, which is

a long established custom pretty well recognized by both

parties here in Montgomery.

Q. And it was the violation by these defendants of that

custom! A. Under these circumstances (R. 219).

23

The command was also violative of petitioners’ rights

because as will be seen, the other asserted basis for the

order—the possibility of disorder by others—could not

justify exclusion of the petitioners from the park (373

U. S. at 292).

This use of the state’s machinery also conflicts with the

statute forbidding discrimination in facilities operated by

interstate motor carriers, 49 U. S. C. §316(d); Boynton- v.

Virginia, supra, and constitutes an unlawful burden on

commerce in violation of Article I, Section 8 of the Con

stitution, Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373.

IV. T he D ecision B elow C onflicts W ith D ecisions o f

T his Court Securing the Fourteenth A m endm ent Right

to Freedom o f E xpression , Assem bly and R elig ion .

The decision below contravenes petitioners’ rights of

freedom of expression, assembly and religion. Their act

of sitting together at the lunch counter in the Trailways

Terminal, was an expression of their moral and religious

belief that segregation is inconsistent with the Christian

ethic (R. 183). It was an entirely peaceful demonstration

of this view as well as an attempt to secure a cup of coffee.

It thus falls within the protection of the First Amendment.

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157; Burstyn v. Wilson,

343 U. S. 495; NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449; Thorn

hill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88.

The conduct of petitioners is analogous to the acts of the

defendants in Garner v. Louisiana, who were convicted of

disturbing the peace for conducting a peaceful sit-in at a

white lunch counter. Recognizing the breadth of the First

Amendment, Justice Harlan, concurring, wrote:

24

We would surely have to be blind not to recognize that

petitioners were sitting at these counters, where they

knew they would not be served, in order to demonstrate

that their race was being segregated in dining facili

ties in this part of the country. Such a demonstration,

in the circumstances of these two cases, is as much a

part of the “free trade” in ideas . . . thought of as speech.

# # # # #

If the act of displaying a red flag as a symbol of

opposition to organized government is a liberty en

compassed within free speech as protected by the

Fourteenth Amendment, Stromberg v. California, 283

U. S. 359, the act of sitting at a privately owned lunch

counter with the consent of the owner, as a demonstra

tion of opposition to enforced segregation, is surely

within the same range of protections (368 U. S. at

201, 202).

And see Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 IT. S. 229; Fields

v. South Carolina, 375 IT. S. 44; Henry v. Rock H ill,-----

U. S.----- -, 12 L. Ed. 2d 79.

25

V. T he Court B elow D eprived P etitioners o f D u e

Process and V iolated the Suprem acy Clause by R efus

ing to A ccept the Federal D istrict Court D eterm ination

That P etition ers W ere Arrested to E n force Racial Seg

regation.

Judge Johnson, in a case involving all of the parties in

this case and the incident involved here, Lewis v. Greyhound

Corp., 199 F. Supp. 210 (M. D. Ala. 1961), concluded as

a matter of fact that petitioners were arrested to enforce

the state’s custom of segregation.6 Although he so con

cluded he refused to grant petitioners’ motion to enjoin

the criminal prosecutions in the state courts. The state

court, completely ignoring Judge Johnson’s conclusion, con

victed petitioners of breach of the peace and unlawful as

sembly. The refusal of the trial court to admit the deter

mination by Judge Johnson that petitioners were arrested

to enforce the state custom of segregation violated peti

tioners’ rights under the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment, and the supremacy clause (Article VI)

of the United States Constitution. If the arrest of the

petitioners was to enforce the state’s custom of segrega

tion, this would be, even in the state courts, a complete

defense to the charges. Boynton v. Virginia, supra; Wolfe

v. North Carolina, 364 U. S. 177, 197 (dissenting opinion

of Chief Justice Warren). The essential question is, there

fore, whether or not the state courts were estopped from

reaching a different conclusion as to the reason for the

arrest of the petitioners.

The Restatement of Judgments, Section 68(1), on the

question of collateral estoppel states: “ . . . where a ques

tion of fact essential to the judgment is actually litigated

6 The Federal Court record was introduced at trial and is a part

of the record on file in this Court although it was not printed in

this Court.

and determined by a valid and final judgment, the deter

mination is conclusive between the parties in a subsequent

action on a different cause of action.” Nor is it important

that the proceedings were criminal in nature. Although the

rule was originally developed in connection with civil liti

gation, it has been widely used by the state and federal

courts in criminal cases. See Hoag v. New Jersey, 356

U. S. 464. As was said by this Court in Yates v. United

States, 354 U. S. 298, 335, “the doctrine of collateral

estoppel is not made inapplicable by the fact that this is a

criminal case, whereas the prior proceedings were civil in

character.” The judgments and decrees of a federal court

are entitled to the same force and effect, so far as res

judicata and collateral attack are concerned, as would be

accorded the judgment of record of a state court under

similar circumstances. Bigelow v. Old Dominion Copper

Co., 225 U. S. 111.

In Southern Pacific Railroad v. United States, 168 U. S.

1, Justice Harlan reviewed the decisions of this Court on

the doctrine of res judicata. His opinion summarizes the

governing law in this ease:

The general principle announced in numerous cases

is that a right, question, or fact, distinctly put in issue

and directly determined by a court of competent juris

diction as a ground of recovery, cannot be disputed in

a subsequent suit between the same parties or their

privies; and even if the second suit is for a different

cause of action, the right, question, or fact once so

determined must, as between the same parties or their

privies, be taken as conclusively established, so long

as the judgment in the first suit remains unmodified.

Id. at 48.

The fact that the state rather than private persons was

involved is unimportant. A federal court judgment which

27

operates as a bar against a subsequent suit in the state

court as to private parties would operate as a bar against

the state as well. Deposit Bank v. Board of Councilman

of Frankfort, 191 U. S. 499.

Thus the factual determinations of the federal court in

Lewis v. Greyhound Corp., supra, precluded the state court

from reaching a different conclusion.

CONCLUSION

W herefore, fo r th e fo reg o in g reaso n s, th e ju d g m en t

below shou ld be rev ersed .

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

C onstance B aker M otley

J ames M. R abbit, III

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

F red D. Gray

34 North Perry Street

Montgomery, Alabama

Louis H . P ollak

127 Wall Street

New Haven, Connecticut

Attorneys for Petitioners

L eroy D. Clark

Charles S . Conley

F rank H. I I effron

R onald R . D avenport

S olomon S. S eay, J r.

Of Counsel

m

m

m

m

HnnlJl LiigiM iliiiitfSatf'i? I IliaEwi

i- n **% a g

P f | i f p §|fj 3 ~ s 2* p t ?

38

t