Stockham Valves and Fittings, Inc. v. Howard Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Stockham Valves and Fittings, Inc. v. Howard Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1977. d47aa235-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f3dbc2f7-be33-4097-901a-6154e981611a/stockham-valves-and-fittings-inc-v-howard-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

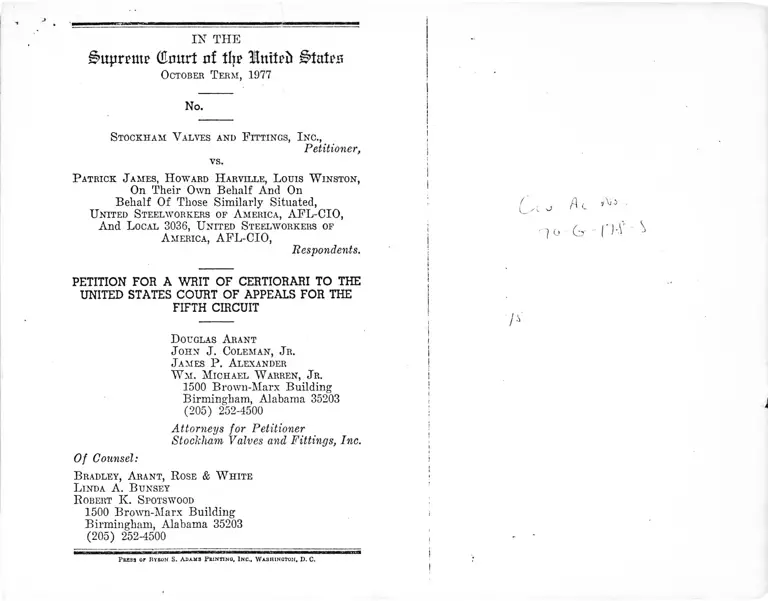

IN THE

^uprrrnr (Enurt of tlj? Mntteii States

October T erm, 1977

No.

Stockham V alves and F ittings, I nc.,

Petitioner,

vs.

P atrick James, H oward H arville, L ouis W inston,

On Their Own Behalf And On

Behalf Of Those Similarly Situated,

U nited Steelworkers of A merica, AFL-CIO,

And Local 3036, U nited Steelworkers of

A merica, AFL-CIO,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

FIFTH CIRCUIT

D ouglas Arant

John J. Coleman, Jr.

James P. Alexander

W m . M ichael W arren, Jr.

1500 Brown-Marx Building

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

(205) 252-4500

Attorneys for Petitioner

Stockham Valves and Fittings, Inc.

Of Counsel:

B radley, A rant, R ose & W hite

L inda A. B unsey

R obert K. Spotswood

1500 Brown-Marx Building

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

(205) 252-4500

P r£3 3 or Byron S. Aham3 P rinting, Inc., W ashington, D. C.

\

*<- ,X,J ■

j o G - ( 'M ’

/* '

I

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

I. O pin io n s B elow ..................................

I I . J urisdiction .......................... ^

III. Q uestions P resented ......................... g

IV. S ta tu tes I nvolved .............................. 3

V. S ta tem en t of th e C a s e ................. ^

Tile District Court Decision....... 7

2. The Court of Appeals Opinion .................. 9

VI. R easons for G rantin g t h e W r i t ....... ............... 10

1. The . Decision of the Fifth Circuit Court of

Appeals Conflicts in Principle With Recent

Decisions of the United States Supreme Court

and Directly Conflicts With Decisions of the

h ourth Circuit Court of Appeals on an Im-

portant Recurring Issue Regarding the Proper

Use of Statistical Evidence in Litigation Under

Iitle VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964___ 10

2. The Court of Appeals So Far Departed From

tlie Accepted Scope of Judicial Review By

Reevaluating Findings of Fact Below, By Re-

weighmg the Evidence, By Substituting Its

Judgment as to Facts For That of the Trial

Court, and By Rigidly Confining the Trial

Court s Discretion Regarding Appropriate

Relief, as to Call For an Exercise of this

Courts lowers of Supervision .............. . lg

3. Evidence of Quantitative Differences in Edu

cational Attainment, Universally Recognized

lo Influence Earnings, Cannot Be Rejected

When Comparing the Earnings of White and

Black Employees..................“ ......... 25

VII. C on clusion .............................................

ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases:

Alabama Power Co. v. Ickes, 302 U.S. 4G4 (1938) .. 22, 23

Albemarle Paper Co. v. bloody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) 1G, 23

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .. 25

Busey v. District of Columbia, 319 U.S. 579 (1943) .. 22

Commissioner v. Duberstein, 363 U.S. 278 (19G0) . . . . 17

Croker v. Boeing Co., ----- F. Supp. ----- , 15 F.E.P.

Cases 1G5 (E.D. Pa. June 20, 1977) .................... 12

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, ----- U.S.

----- , 53 L. Ed. 2d 851 (June 27, 1977) . . . . 16, 23, 24

Dobbins v. Local 212, 1BEW, 292 F. Supp. 413 (S.D.

Ohio 19G8) ........................................................... 12

EEOC v. Eagle Iron Works, 424 F. Supp. 240 (S.D.

Iowa 1976) ........................................................... 12

EEOC v. United Virginia Bank, ----- F.2d ----- , 15

F.E.P. Cases 1257 (4th Cir. May 10, 1977) ....... 14

Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. v. Grosjean, 301

U.S. 412 (1937) ....................................................... 22

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) . . . . 27, 29

Hazelwood School District v. United States,----- U.S.

----- , 53 L. Ed. 2d 768 (June 27, 1977) .. 10,11,14,16,

22, 26

Hester v. Southern Ry. Co., 497 F.2d 1374 (5th Cir.

1974) ..................................................................... 14

Hill v. Western Electric, 12 F.E.P. Cases 1175 (E.D.

Va. 1976), appeal docketed, (4th Cir. No. 76-2439) 15

International Salt Co. v. United States, 332 U.S. 392

(1947) .................................................................... 23

Mayor v. Educational Equality League, 415 U.S. 605

(1974) 12,16

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 535 F.2d 257 (4th

Cir.), cert, denied, 429 U.S. 920 (1976) .............. 13,14

Roman v. ESB, Inc., 550 F.2d 1343 (4th Cir. 1976). 12,13

Swint v. Pullman-Standard, ----- F. Supp. ------, 15

F.E.P. Cases 145 (N.D. Ala. July 5, 1977) ........... 12

Teamsters v. United States,----- U.S.-------, 52 L. Ed.

2d 396 (May 31, 1977) ........................................ 10,14

Uebersee Finanz-Korporation v. McGrath, 343 U.S.

205 (1952) ............................................................. 22

United States v. Greater Buffalo Press, Inc., 402 U.S.

549 (1971) ........... 23

Table of Authorities Continued iii

United States v. National Ass’n of Real Fstate

Boards, 339 U.S. 485 (1950) ...... [ .. . * 1 -m

United States v. Yellow Cab Co., 338 U.S. 338 (1949) 18,

Washington v. Shell Research d> Development Co

17821 <SD- T« -

Z ‘ niv ‘s Em a %&V- nazeltinê

....................17,19, 22

S ta tu tes :

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ..................

42 U.S.C. U0S1 ........................................................... 3 2

“ Eights J M o f i m ' Secti0” ?03(a) of the Civil ^° ts Act or 1964, as amended.......................passim

R u l e s :

Rule 52(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 3,17, 24

O th e r A u th o rities :

w' L Hr w "^ ^ ? l6o ? ,? oj?Iingand, E‘ ™îview 409 (1970)’ ^ n c a n Economic Re-

F. C. Morris, Jr., Current Trends In The Use ( And

f r \ K ° f S.iatlstlcs In Employment Discrimina-

Counn J f X ° n . . (EqUal E" Pl0yment*************••••••», 15 16

B. R. Schiller, The Economics of Poverty and Die crimination (1973) ___ wcriy ana Dis-

L. C. Tliurow, Poverty and Discrimination (1969) .. 28

& “(f 9? 3)Human The ^

Action Programs W yants for Affirmative

...................................................................5 ,1 9

IN THE

&ttpr*m* (Erntrt o f % Itttfrft States

O ctober T erm, 1977

No.

S tockham V alves and F ittings, I nc.,

Petitioner,vs.

P atrick J ames ̂ H oward H arville, L ouis W inston

On Their Own Behalf And On ’

Trmfr? eiQlf Ttose Similarly Situated

UAnrLocALLW K nS °F AJierica- AFL-CIO, And L ocal 3036, U nited Steelworkers of

A merica, AFL-CIO,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO tttp

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

FIFTH CIRCUIT

,.«Tlle*?enlti0Iler Stockham Valves alKi Fittings Ine

view y -P7 yS ‘ !lat 3 WrH of 4 u e to

An™ l / o f the Uniteci States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit entered in this action

on September 19, 1977.

I. OPINIONS BELOW

forT tte °F m nc°f “ •! Y " “ ed States Court »f Appeals toi the Fifth Circuit dated September 19, 1977 is re

ported at 559 F.2d 310 and appears in the separate

2

Appendix to the petition at pages 2-99. The Findings

of Fact and Conclusions of Law of the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Alabama

dated March 19, 1975 are reported at 394 F. Supp. 434

and appear in the separate Appendix at pages 100-22 .

II. JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered

September 19, 1977. (App. 1). On October 13, 1977,

the Court of Appeals stayed its mandate to and includ

ing November 12,1977. (App. 224-25). Jurisdiction of

this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

III. QUESTIONS PRESENTED

The questions presented for review are:

1. Whether an employer of blacks in numbers

which far exceed their representation in the relevant

labor market is obligated 'as a matter of law to insure

that blacks are distributed among jobs at all skill

levels at a percentage equal to black participation in

the employer’s total work force without regard for the

qualifications required for various jobs.

2. Whether the Court of Appeals invaded the prov

ince of the trial court by substituting its judgment as

to facts for the trial court’s findings of fact and by

•precluding the trial court on remand from making its

own findings of fact and exercising its own discretion

with respect to appropriate relief.

3 Whether an inference of employment discrimina

tion may be premised on earnings disparities between

blacks and whites without regard for quantitative

differences in educational attainment, a productivi y

factor universally recognized to affect employee earn

ings.

3

IV. STATUTES INVOLVED

1. 42 U.S.C. §1981:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State

and Territory to make and enforce contracts, to

sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the full and

equal ̂benefit of all laws and proceedings for the

security of persons and property as is enjoyed by

white citizens, and shall be subject to like punish

ment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and exac

tions of every kind, and to no other.

2. Section 703(a) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a):

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for

any employer—

( 1 ) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any

individual, or otherwise to discriminate against

any individual with respect to his compensation,

terms, conditions, or privileges of employment,

because of such individual’s race, color, religion,

sex, or national origin; or

( 2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees

or applicants for employment in any way which

would deprive or tend to deprive any individual

of employment opportunities or otherwise ad

versely affect his status as an employee, because

of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or

national origin.

3. Rule 52(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Pro

cedure :

. . . Findings of fact shall not be set aside unless

clearly erroneous, and due regard shall be given

to the opportunity of the trial court to judge of

the credibility of the witnesses. . . .

!

V. STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This petition raises ^uestionso^natiom

tance as to the proper use of statistical data as evi-

dence of racial discrimination in job assignments and

as to the appropriate role of a court of appeals in re

viewing district court Endings of fact and in fashion-

ing relief at the appellate level.1

The individual respondents (plaintiffs below), three

long-service black production and maintenance em

ployees of Stockham Yalves and Fittings, Inc., com

menced this action individually and on behalf of other

black production and maintenance employees similarly

situated for claimed violations of Title Y II of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, and 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981. (App. 3).

Stockham employs more than 1,800 production and

maintenace employees at its Birmingham valves and

fittings manufacturing facilities.2 Down through the

years at least two-thirds of these employees have been

black (App. 105), although the Birmingham Stand

ard Metropolitan Statistical Area ( “ SMSA” ) in

4

1 The Union respondents, defendants below, at all times material

to this action were the bargaining representatives for the individual

plaintiffs and Stockham’s hourly production and maintenance em

ployees. (App. 103).

! Jobs at Stockham are divided according to the complexity of the

job and skills required into Job Classes 2 through 13. (App. 1G6).

High skilled production and craft jobs fall within Job Classes 10-13.

Although the base pay rate of a job increases as the job class

increases, actual earnings of workers are not determined by job

class because virtually all of Stockham’s production employees

receive incentive pay (which averages approximately 25 percent of

base pay). (App. 10G). High skilled and craft jobs are non-incentivo

jobs. (App. 116).

5

which they reside is only 25 percent black. (App.

161). Each of the plaintiffs left previous employment

with other Birmingham employers because of the su

perior work opportunities available to him at Stock

ham. (App. 199, 201). Many of the black employees

at Stockham are relatively unskilled; but for their

positions with Stockham they would otherwise be con

sidered “ hard core unemployables” .’ (App. 129).

Plaintiffs claimed in their complaint and at the trial

that plaintiffs as a class were the subject of discrimi

nation by Stockham, inter alia, in the allocation of

jobs, but plaintiffs proffered no^evidence that Stock

ham had, in fact, discriminated in initial assignments

o,.]:i.P.I-2IJl0ti°ns against any black employee vis-a-vis any

white employee with equal or poorer qualifications.4

* Stockham’s black work force was so characterized by Dr Rich-

ard Barrett a witness for plaintiffs on the testing issue, when he

visited Stockham s Birmingham plant in 19G8. In 1974 Stockham

received an award from the Birmingham Urban League referable

to the fact that it had hired more minority referrals durirm the

preceding year than any other employer. (App. 129).

‘ Although Stockham employed Wonderlic tests as a factor in the

evaluation of its employees for hiring and promotion purposes

betueen 1965 and 1971, plaintiffs proffered no proof whatever to

reflect that the black employees at Stockham scored worse than the

white employees on the tests; instead plaintiffs relied upon a publi-

cation entitled Negro Norms: A Study of 38,452 Job Applicants for

Affirmative Action Programs, prepared by E. P. Wonderlic & Asso-

and dcfIn d f q 1?' Expert testing Psychologists for plaintiffs and defendant Stockham were in total agreement that Negro Norms

offered no reliable information with respect to test scores referable

to tho black popu ation at Stockham. (App. 184). While it is true

that one of Stockham s expert witnesses recalled some incomplete

ata with respect to Wonderlic test scores at Stockham, the same

ltness further expressed her uncontradicted judgment that such

data was so inadequate that no reliable conclusion could be reached

6

Furthermore, plaintiffs introduced no “ pattern” evi

dence as to the relative qualifications of blacks and

whites at Stoekham and chose to rely instead upon

statistical evidence to support their claim that because

of race, blacks, as a class, were allocated the poorer

paying, hot and dusty jobs and whites the better pay

ing jobs with less onerous working conditions.5 Ac

cording to plaintiffs, Stoekham discriminated against

blacks in job assignments and promotions because (i)

only 5 percent of the employees in the relatively few

high skilled and journeyman craft jobs at Stoekham

are black; and (ii) average hourly earnings of blacks

at Stoekham are 91 percent of average hourly earn-

with respect to the racial impact of the tests. (App. 185). The Dis

trict Court found, predicated upon these facts, that there was no

proof that the Wonderlic test had a racially disproportionate im

pact on blacks at Stoekham in violation of Title VII. (App. 186).

• Statistical references to the high proportion of black employees

at Stoekham whose jobs involve hot and dirty working conditions

seemingly create a “ straw” issue. Working conditions are immut

able, and working conditions in foundries are by nature hot and

dusty. (App. 114). The conception that blacks in substantial num

bers gravitate to foundry jobs because of their qualifications for

such jobs is surely more acceptable evidence of nondiseriminatory

employment policies, in the absence of contradictory evidence, than

the conception that an employer contrary to his economic interests

deliberately assigns blacks to hot and dusty jobs merely because

they are black. Furthermore, plaintiffs’ claims must be considered

in light of the following facts of record: (i) a great majority of all

production and maintenance employees at Stoekham are black

(App. 105); (ii) hot and dusty working conditions are a character

istic of many of the high skilled jobs held predominately by white

employees at Stoekham (App. 130); and (iii) there was no evidence

that any black employee at Stoekham was exposed to more onerous

conditions on his job than any white employee at Stoekham in the

same job, or, indeed, more onerous conditions than those of any

white employee at Stoekham in any job for which a black employee

was qualified. (App. 115).

7

ings of whites (without adjustments to take account

of productivity factors such as absenteeism, job skills

education, etc.). ’ J ’

1* * The District Court Decision

The District Court, viewing plaintiffs’ statistical

evidence in the context of other salient facts of record,

concluded that it did not support the claims of dis

crimination by Stoekham against blacks in either ini

tial job assignments6 or promotions.7

T h eD isln d Court, after hearing the witnesses, judging their

credibility and reviewing the documentary evidence of record,

expressly found, inter alia, that since the effective date of Title VII ■

(i) there was no evidence that any black applicant at Stoekham had

S I S and / ■•wJiemcA 3 j °b in favor of a white applicant at Stoekham; (n) there were virtually no black applicants for em-

ployment in the greater Birmingham area who possessed the high

skills needed for craft jobs at Stoekham (App. 128) • (iii) the 5

percent representation of blacks in high skilled jobs at Stoekham

compared favorably with the representation of blacks possessing

such skills who live in the Birmingham SMSA, according to U.S°

Census statistics (App. 128); (iv) without exception every black

employee at Stoekham possessing skills of a journeyman or the

equna ent was employed by Stoekham in a job commensurate with

( PP‘ 128,} : (V) the earuil>gs of black applicants

lured by Stoekham since the effective date of Title VII are sta

tistically identical to those of post-Act white hirees (App 163) ■

A T 7 0f, St0ckhara’3 black employees are relatively un

skilled; but for the work opportunities offered at Stoekham to

blacks, a substantial portion of its black employees would be “ hard

core unemployables.” (App. 129).

. T The tD'strict Court’s ultimate conclusion on this issue, adverse

o p aintiffs, was predicated upon, inter alia, the following facts:

(i) plaintiffs failed to produce any evidence that Stoekham had

discriminated against any black employee by failing to pro,noS him

to a job for which he was qualified or for which he possessed quali-

c m p lo jit S , lhM' by WhUc inCUmb“ t

8

The District Court, on the basis of these facts,

reached the judgment that “ [t]he relatively small

number of blacks in certain high skilled and craft jobs

at Stockham is due not to any discriminatory prac

tices at Stockham but due instead to the absence of

qualified blacks.” The Court added:

An employer is entitled to insist that his workers

be qualified and as long as the qualifications, as in

this case, are not artificial or established with an

intent to discriminate, the employer is not required

to place individuals of any race who lack such

qualifications on the job. Plaintiffs have failed to

establish racial stratification, through either ini-

(ii) there were no lines of progression at Stockham and no on-the-

job training programs pursuant to which an employee automatically

became qualified for a higher rated job by virtue of performing the

duties of his current position (App. 123);

(iii) any Stockham employee may file a “ timely application”

for a desired job at any time whether or not the job is vacant, and

mav maintain applications on file for several jobs at once (App.

123);

(iv) during the relevant period nearly 1,200 timely applications

were filed, 609 of which were filed by black employees; 27 percent

of the timely applications filed by blacks, as compared with a

statistically commensurate 31 percent of timely applications filed

by whites, were granted (App. 124);

(v) there are equal earnings opportunities in almost all of the

departmental seniority units (i.e., in ten of the twenty-two seniority

units unadjusted black gross earnings exceeded unadjusted white

gross earnings, and in nine of the seniority units the unadjusted

black hourly earnings exceeded unadjusted white hourly earnings)

and there was no showing that black employees were denied jobs

either within departmental seniority units or across departmental

lines (App. 125, 166) ; and

(vi) plaintiffs’ average hourly earnings as a class in proportion

to white average hourly earnings at Stockham had increased from

85 percent to 91 percent since the effective date of Title VII. (App.

162).

9

tial job assignments or promotion and transfer

decisions, in the job classification system at Stock

ham. (App. 213).

2. The Court of Appeals Opinion

The Court of Appeals reversed. The Court concluded

statistics alone in the case sub judice “ establish

a clear prima facie case of purposeful discrimination.”

(App. 35). According to the Court, it was not material

that black representation in high skilled and craft

jobs at Stockham compares favorably with local and

national labor markets. “ The relevant work force for

comparison purposes is Stockham where 66 percent of

all maintenance and production workers are black”

(App. 59) and “ [bjlacks earn, on the average, $0.37

less per hour than whites.” (App. 35). The Court did

not consider other highly relevant statistical evidence

introduced by Stockham; indeed, it even disregarded

evidence as to the earnings of Stockham employees

hiied after the effective date of the Act stating that

“ relative changes” in earnings of such employees “ re

cently hired” (i.e., hired since the effective date of Title

V II ) are “ irrelevant to the question of discrimination

at Stockham.” (App. 39). The Court also rejected

Stockham s multiple regression analysis which an

alyzed black earnings relative to white earnings in

terms of various productivity factors. The Court chal

lenged the use of education as a productivity factor

to explain earnings differences between whites and

blacks. White employees at Stockham have more edu

cation than blacks and education “ is not a job require

ment at Stockham hence, the Court declared, educa

tion is irrelevant to adequate job performance.”

(App. 41). In so concluding, the Court ignored Dis

trict Court findings predicated upon expert testimony

10

that an individual’s educational level, regardless of

race, impacts earnings.8 (App. 41).

VI. REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

There are three special and important reasons why

the writ should be granted:

1. The Decision of lhe Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Conflicts In

Principle With Recent Decisions of the United Stales Supreme

Court and Directly Conflicts With Decisions of the Fourth

Circuit Court of Appeals On An Important Recurring Issue

Regarding the Proper Use of Statistical Evidence In Litigation

Under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Court of Appeals failed to apply the princi

ples recently mandated by this Court on the^projDe^

use of statistical evidence in Title V II cases, in

Teamsters v. United State s ,------ U .S .------- , 52 L. Ed.

2d S9(>, 4iT (T lay 31, 1977), this Court acknowledged

that statistics play an important role in employment

discrimination cases but admonished that “ statistics

are not irrefutable . . . their usefulness depends on all

of the surrounding facts and circumstances.” Writing

for the majority in Hazehvood^School v.

United States,------U .S .------- , 53 U F U 2cl fm t vVV-78

n.12 (June 27, 1977), Mr. Justice Stewart recognized

that “ when special qualifications are required to fill

particular jobs, comparisons to the general population

(rather than to the smaller group of individuals who

possess the necessary qualifications) may have little

probative value.” The Fifth Circuit failed to consider

* 8 The superficiality of the Fifth Circuit’s statistical analysis

may explain why the Court thereafter (App. 35, 37) attempted to

premise an inference of racial discrimination in job assignments

upon the fact that until early 1974 some Stockham facilities were

segregated.

■ 14 7 7

i i

the “ necessary qualifications” for the effective per

formance of the various jobs at Stockham. Instead,

that Court relied on undifferentiated statistics reflect

ing the racial composition of Stockham’s entire pro

duction and maintenance work force as the basis for

its erroneous conclusion that Stockham discriminates

against blacks by placing them in less desirable jobs.

In effect, the Fifth Circuit’s decision is premised on

the irrational assumption that each Stockham em

ployee is presumptively . qualified for eveiy job at

Stockham regardless of the skills required for success

ful performance of that job.

The Fifth Circuit held that Stockham discriminated

against blacks because blacks did not occupy craft and

high skilled jobs in percentages comparable to the

percentage of blacks in its entire production and

maintenance work force. Conversely, the District

Court concluded that the five percent representation

of blacks in craft jobs at Stockham was not an under

representation of blacks compared to the percentage

of blacks with the necessary qualifications for those

jobs in the local and national labor markets. (App.

128). The Court of Appeals reversed this finding as

‘ 1 clearly erroneous” :

The relevant work force for comparison purposes

is Stockham where 66 percefit of all maintenance

and production workers are black. When com

pared with that figure, 5 percent looks paltry in

deed. (Footnote omitted; App. 59).

The Fifth Circuit’s analysis fails to conform to the

mandates of this Court. First, contrary to Hazelwood,

it ignores the unrebutted evidence credit.erj hv thp. Pis-

trict Court that special skills are muiired- for the ef

fective performance -of many jobs held by Stockham

employees. (App. 134-56). Due to job requirements at

12*

Stockham, “ this is not a case fn which it can be as

sumed that all [employees] are fungible for purposes

of determining whether members of a particular class

have been unlawfully excluded.” Mayor v. Educational

Equality League, 415 U.S. 605, 620 (1974). See Sivint

v. Pullman-Standard,------ F. Supp. ------ , 15 F.E.P.

Cases 145, 150 (X.D. Ala. July 5, 1977); Croker v.

Boeing C o .,------F. S upp .--------, 15 F.E.P. Cases 165,

203 (E.D. Pa. June 20, 1977); Washington v. Shell

Research & Development C o .,------F. S u pp .------- , 14

EPD H 7821 (S.D. Tex. March 17, 1977); EEOC v.

Eagle Iron Works, 424 F. Supp. 240, 14 F.E.P. Cases

536, 543 (S.D. Iowa 1976); Dobbins v. Local 212,

IB E W , 292 F. Supp. 413, 445-46 (S.D. Ohio 1968).

Second, the credited and unrebutted evidence is, and

the District Court so found, that every black employee

at Stockham who is qualified for a high skilled job

already works in a position commensurate with his

qualifications. (App. 128, 134). Absent evidence that

each employee in a low skilled job could obtain the

necessary qualifications for a high skilled position

through on-the-job experience, the only valid bench

mark for assessing whether an employer’s policies

and practices have a discriminatory impact on blacks

seeking high skilled jobs is the percentage of blacks in

the relevant labor market possessing the qualifications

needed for the effective performance of the high

skilled jobs.

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal’s reliance on an

undifferentiated comparison between the racial com

position of the entire production and maintenance

work force and that of the high skilled jobs as proof

of racial discrimination conflicts_with several decisions

ytu* by the Fourth Circuit Court o f Appeals. In Roman v.

V - ESB, Inc.. 550 F.2d 1343 (4th Cir. 1976) (en banc),

13

plaintiffs charged their employer with, among other

mgs, racial discrimination in job assignments in

violation of Title V II. In concluding plaintiffs failed

to establish that blacks were underrepresented in

craft, managerial, and clerical positions, the Fourth

Circuit repeatedly compared the percentage of blacks

in those positions to the pmuai£nge of blacks in the

relevant labor mnrVAt “ gualifiedfSTsiieh wnrlr » JT**

at 1354-55. By failing to follow "the statistical meth-

odology used by the Fourth Circuit in Roman and

thereby comparing the percentage o f blacks in craft

and high skilled positions at Stockham to the percent

age of blacks in the relevant labor market qualified

for such work, the Fifth Circuit ignored the proscrip

tions of this Court concerning the use of statistics

m the context of self-evident facts of industrial life.

The conflict therefore, between the Fifth Circuit and

e Fourth Circuit is fundamental and irreconcilable.

This conflict between the Fifth Circuit and the

Fourth Circuit on the use o f comparative work force

statistical evidence m employment discrimination

cases is again apparent in Patterson v. Amp.n'mv To-

' P f denied, 429

. ; 920 (1976)- Patterson involved the Fourth Cir-

cmt s review of a trial court’s order mandating pref

erential promotions for women and blacks until their

percentages in the employer’s supervisory work force

equaled their percentages in the general Richmond

SMSA work force. The Fourth Circuit determined

that the proper comparison was between the percent

ages o f women and blacks in the Richmond SMSA

supervisory work force and the percentages of women

and blacks promoted since 1965 by the employer since

[t]hose percentages furnish a more realistic mcas-

14

ure of the company’s conduct.” 535 F.2d at 275.

is difficult to imagine a less realistic benchmark o

Stockham’s treatment of its minority _ employees than

the Fifth Circuit’s simplistic statistical work force

comparison utilized in this case.

The issue presented on the proper use of compara

tive work force statistics arises in jO illiaill evei7 Ŝ'

t.inn under Title V II . involving claims of racial dis-

/.riTninnt.inn in job assignments and iiupromotions. The

recent opinions'in Teamsters and Hazelwood provide

considerable direction on the proper use of statistical

work force comparisons as evidence of racial discrim

ination in hiring; this Court’s review of the decision

of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in this case

would clarify the role of statistical evidence m Title

•Accord EEOC v. United Virginia Bank, ------ P-2d , 15

F E P Cases 1257, 1259 n.7 (4th Cir. May 10, 1977) (“ Where the

work requires special qualifications, it is proper to. consider the ratio

of qualified blacks and whites in the appropriate work force rather

than the ratio of the gross percentage of blacks and women in the

whole work force, including, unskilled labor.” )

>» See also Hester v. Southern By. Co., 497 F.2d 1374 (5th Cir.

1974) where the Fifth Circuit refused to find pi’oof of racial

discrimination in hiring for a data typist job based on a comparison

between the percentage of blacks in the general SMSA and the

employer’s work force:

\C]omparison with general population statistics is of question

able value when we are considering positions for which, as here,

the general population is not presumptively qualified Data

Typist applicants were required to prove their ability to type

at a minimum speed of sixty corrected words per minute as a

prerequisite to consideration by Southern for employment . . .

A more significant comparison might perhaps be between tho

percentage of blacks in the population consisting of those able

to type GO wpm or better and, the percentage hired into the

Data Typist position by Southern. (Italics supplied; Id. at

1379 n.6.)

15

Y II cases involving claims of discrimination in ini

tial job assignments and in promotions.

The statistical methodology mandated by the Fifth

Circuit in this case requires an inference of discrimi

nation when blacks are not equally represented at all

levels of an employer’s work force, without regard for

qualifications. The anomalous result of the Fifth Cir

cuit’s rule is to penalize an employer, such as Stock-

ham, who has attracted to its work force a large num

ber of blacks, including many of the “ hard core un

employed.” (App. 129). See Hill v. Western Electric,

12 F.E.P. Cases 1175, 1179 n.4 (E.D. Va. 1976), ap

peal docketed, (4th Cir. No. 76-2439). It is more likely

that such an employer will be found guilty of unlaw

ful discrimination in job assignments than the em

ployer whose job opportunities for blacks are limited

to the percentage of blacks in the relevant labor

market."

The decision of the Fifth Circuit in this case illus

trates the uncertainty presently surrounding the

proper manner to prove racial discrimination in job

assignments thrnmrh ;------' ri:

forces. This uncertainty obviously impedes the effec

tive implementation of the equal employment oppor

tunity laws and the attempts of employers to identify

and comply with the mandates of such laws. See, e.g.,

F. C. Morris, Jr., Current Trends In The Use (And

Misuse) Of Statistics In Employment Discrimination

11 As the District Court found, based upon unrebutted expert

testimony, the proper inference to be drawn from statistics showing

a significant over-representation of blacks is that Stockham offers

superior job opportunities to blacks and that blacks migrate to

Stockham jobs. (App. 161-G2).

16

Litigation (Equal Employment Advisory Council

1977). Proper resolution of the issue by this Court is

necessary to bring order to the chaotic state of em

ployment discrimination case law.

2. The Court of Appeals So Far Departed From the Accepted

Scope of Judicial Review By Reevaluating Findings of Fact

Below, By Reweighing the Evidence, By Substituting Its Judg

ment As To Facts For That Of The Trial Court, and By Rigidly

Confining the Trial Court's Discretion Regarding Appropriate

Relief, As To Call For An Exercise Of This Court's Powers Of

Supervision.

This Court has become increasingly concerned with

encroachment of appellate courts upon district courts,

particularly in cases that may turn upon statistical evi

dence and the credibility of witnesses or that may re

quire injunctions of broad impact affecting opportuni

ties and expectations of a large group of people. In

deed, this Court has said that the proper allocation of

functions between district courts and courts of appeals

raises issues “ every bit as important” as the issues

raised by an appeal on the merits, including issues

raised in a racial discrimination case. Dayton Board,

of Education v. Brinkman, ------U .S .--------, 53 L. Ed.

2d 851, 857, 862 (June 27, 1977); Hazelwood School

District v. United States, supra, 53 L. Ed. 2d at 780;

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) ;

Mayor v. Educational Equality League, 415 U.S. 605,

621 (1973).

In the case at hand the Court of Appeals engaged

in a de novo fact-finding process, disregarding the

weight the trial court accorded the evidence. There

after, it substituted its judgment second hand for

that of the trial court and fashioned its own remedies.

17

Such an invasion of the trial court’s functions war-

rants the exercise bv this Court of its supervisory

not merely because it permeates the entire

appellate opinion in this case, thus vitiating its legiti

macy as an appellate decision, but more significantly

because it impugns the integrity of trial courts gen

erally and undermines the established, efficient, and

oiderly allocation of functions in the federal judiciary

Pair employment statutes have resulted in a prolifera

tion of complex and lengthy lawsuits, won or lost by

means of documentary evidence, statistical proof, and

conflicting testimony. I f courts of appeals are per

mitted to reevaluate evidence, determine anew the

weight and credibility of witnesses’ testimony, and

adjudicate relief, the value of a trial court’s intimacy

with the facts over a long period will be forfeited and

replaced by the dangers attendant to the necessarily

circumscribed vision of an appellate court, straining

to see the evidence itself from afar.

+. ^ acknowledging the clearly.ermncnn. r u ]^

the rifth Circuit reweighed items of evidence bearing

on critical issues and, after overturning factual find-

mgs below, utilized its own substituted factual findings

to pyramid and overturn still other trial court findings

By reference to its own findings, it thus boot-strapped

reversals of factual findings by the trial court. For

example, the Court of Appeals extracted testimony of

one witness regarding two medical dispensary rest-

12 Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a). The rule forbids setting aside factual

findings on appea! unless they are clearly emmeou. and, as inter-

p eted by this Court, prohibits de novo determination of factual

95 USnia0P0PT 3 n t i Rao i i0 Cr • V- JIazMne K s e a lc tZ • . V " ? ( M * ) - The rule applies to all factual finding

eluding factual inferences from undisputed facts or documents’

Commissioner v. Duberstein, 3G3 U.S. 278, 289-91 (19G0).

18

rooms, construed that witness’ testimony directly con

trary to the trial court’s own construction and credi

bility judgment, and thereby changed the facts con

cluding that the two restrooms were segregated at the

time of trial. This independent appraisal of oral testi

mony contravenes the rule requiring that due regard

be given to the trial court’s opportunity to assess testi

mony of witnesses. United States v. 1 elloxo Cab Co.,

338 U.S. 338, 341-342 (1949).

The Court of Appeals next overturned the trial

court’s finding that a dispute over alleged segregation

of facilities had been resolved by a 1974 conciliation

agreement between Stockham and the EEOC, predi

cating its reversal on the proximity of that agreement

to trial time. According to the Fifth Circuit, the evi

dence” of the racially separate dispensary restrooms

and the company’s “ intransigent resistance” to de

segregation of plant facilities indicate that the Dis

trict Court ‘ 1 over-relied on the conciliation agreement

(App. 19), despite the explicit, unchallenged findings

below of Stockham’s efforts over a period of several

years to resolve the facilities issues with the EEO

( App. 180-81) ; efforts which were directly frustrated

by that agency’s failure to perform its statutorily di

rected conciliation role. The finding of Stockham s

“ intransigent resistance” , repeated throughout the

Fifth Circuit’s opinion, was totally without eviden

tiary support and directly contrary to the District

Court’s finding of Stockham’s good faith attempts to

comply with the Act which was neither noted nor over

turned by the Court of Appeals. The Fifth Circuit

thus ignored the prohibition against de novo fact-find

ing on review. It also breached the rule that a finding

is not clearly erroneous merely because the reviewing

19

court gives the facts another construction, resolves am

biguities differently, or attributes a more sinister cast

to actions deemed innocent by the trial court. Zenith

Radio Corp. v. IlazeUine Research, Inc., 395 U.S. 100,

123 (19G9) ; United States v. National Ass’n of Real

Estate Boards, 339 U.S. 485, 495-96 (1950).

Moreover, these invasions of the trial court’s func

tions were aggravated when the Fifth Circuit utilized

its own findings regarding the dispensary restrooms

and the “ intransigent resistance” to desegregation to

fashion, at least in part, its independent findings of

discrimination in initial job assignments (App. 43)

and in promotions (App. 68), despite the total absence

of evidence that any purported segregation of em

ployee facilities ever affected job assignments. The con

clusions of job discrimination are thus fatally flawed

because they are premised on invalid (as well as irrele

vant) findings made by the Court of Appeals in dero

gation of the District Court.

Invasions of the trial court’s traditional province

so permeate the Fifth Circuit’s opinion that it reads

like a district court’s findings of fact. Indeed, the

District Court and Court of Appeals opinions appear

to address entirely different lawsuits. The disparity is

not due to clearly erroneous findings by the trial court

but, in large part, to independent findings by the Fifth

Circuit conjured from non-existent evidence and in dis

regard of unrefuted evidence below," or premised on

" The Pifth^Circuit made findings contrary to the., undisputed

evidence when it :

(i) based its conclusion that the Wonderlic test adversely impacts

black Stockham employees in part upon a nationwide study, (Negro

Norms), not involving Stockham. (App. 47, 51). The only testimony

regarding this study was'that of experts for both parties who agreed

20

credibility judgments contrary to those made by the

trial court,” or developed de novo after reversals o

that no inference of adverse impact at Stockham may be predicated

uron such evidence. The irrelevance of this study to Stockham is

confirmed by the EEOC’s “ Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures” , 29 C.F.R. §§ 1607.0, et seq.;

(ii) concluded that the trial court “ gave too much we,0ht to

plaintiffs’ failure to offer evidence of actual scores blacks and

whites achieved on the Wonderlic test because accumidatmn of the

evidence would have been too burdensome on plaintiffs. (App.

& n 391 The Court’s finding of burdensomeness, which has its

^ in plaintiffs’ appellate'brief, teas made without any si,«w »*

that a survey of at least a representative sample of scores at Stoe

ham was impossible or unrealistic (App. 185 H (e )) and is unsup-

P°(iii) based^itTconclusion of discriminatory job allocations in part

upon its independent finding that the “ vast majority of blacks

work in undesirable (particularly hot and dusty) working condi-

tions (App. 35, 75). The Court ignored but left in tact findings

below, based on unrebutted evidence and made on a.J°b-hy-Job

basis, that many high skilled jobs occupied Prf ° “ n ly ^

whites have onerous working conditions (App. 130 (HI 6 & 7, 134-50,

especially ^ 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 37) and that some of the jobs in.

which blacks predominate and which are associated with hot and

dusty conditions are “ more desirable” skilled jobs and, ironica v,

historically have been considered “ white jobs” at other employers

in the southeastern United States. (App. 114, 127 ). i oreovcr,

the Court ignored the obvious reality that since blacks constituted

two-thirds of all production and maintenance employees at Stoclc-

ham even if blacks were evenly distributed through all job classes

as the Court suggests, blacks would continue to predominate in all

jobs with “ undesirable” working conditions; and

(iv) remanded the issue on whether the seniority system is bona

fide (App. 85, 91), despite the District Court’s express, undisturbed

factual finding that the system was “ developed because of func

tional, nonracial reasons.” (App. 127 (16). The District Court s

finding, which constitutes a conclusion that the system is bona fide,

was entirely ignored by the Fifth Circuit despite the fact that the

Court of Appeals seemingly accepted Stockham’s departmental

seniority system as bona fide to the extent that it was utilized by

plaintiffs as a productivity factor favorable to blacks in plaintiffs

statistical presentations.

11 The Court of Appeals accorded no deference to the trial court s

21

legal standards utilized by the District Court, which

thus never had the opportunity to make factual find

ings in accordance with the legal standards enunciated

by the Court of Appeals."

Such appellate fact-finding represents a drastic de

parture from fundamental principles of appellate re

view. These principles dictate that a reviewing court * (i)

opportunity to observe the demeanor of witnesses and to evaluate

their testimony when it :

(i) believed Jack H. Adamson’s testimony that Stockham does

not utilize the Tabaka tests in making employee selection decisions

(App. 54), whereas the District Court believed the same witness’

testimony, not referred to in the Fifth Circuit's opinion, that the

tests were utilized (App. 191);

(ii) credited the testimony of plaintiffs’ statistician, Martin

Mador, who made a poor impression at trial, admitted to numerous

errors on cross-examination, and whose mathematics the district

court considered “ simple” and questionable “ ‘ statistics.’ ” (App.

156). The trial court attached greater weight to the testimony of

defendant’s expert Dr. Gwartney and to his unrefuted testimony

regarding the need to adjust an earnings comparison to take into

account productivity factors;

(iij) reversed the District Court’s finding that Stockham had not

discriminated against the named plaintiffs, although the record

lacked substantive evidence of discriminatory acts, or of their quali

fications for any jobs they were purportedly denied. In particular

the District Court attached little weight to plaintiff James’ testi

mony, partly because of his audacious exaggeration of his educa

tional accomplishments which were impeached by a sealed tran

script, showing a majority of failing grades and many fewer course

hours than he represented, which was included in the record on

appeal; and

(iv) extracted, out of context, Dr. Haworth’s testimony in foot

note 39. See note 13 ( i ), supra.

" For example, the Fifth Circuit rejected as “ legally irrelevant”

the trial court’s finding of no discrimination in craft positions,

premised on absence of evidence that any qualified black had been

rejected for a craft job. (App. 58). After five.pages of appellate

fact finding, the Court concluded that Stockham had discriminated

against blacks in selection and training of craftsmen.

22

must not substitute its judgment as to facts for that of

the trial court by deciding whether it would have

found otherwise, but must confine its review to deter

mining whether the trial court could permissibly find

as it did. Zenith Radio Corp. v. Hazel tine Research,

Inc., supra. Accordingly, “ where the evidence would

support a conclusion either way but where the trial

coui’t has decided it to weigh more heavily for the de

fendants . . . [s]uch a choice between two permissible

views of the weight of the evidence is not ‘ clearly er

roneous’.” United States v. Yellow Cab Co., supra, 338

U.S. at 342. Findings which have substantial support

in the evidence will be accepted by the reviewing court

as unassailable. Alabama Poiver Co. v. Iclces, 302 U.S.

464, 477 (1938); Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. v.

Grosjean, 301 U.S. 412, 420 (1937). The Fifth Circuit

abrogated these established principles by weighing

testimony and other evidence anew.

Moreover, the Court of Appeals’ reversal of the

legal standards employed below without a remand to

enable the trial court to reevaluate the evidence

against the revised legal standards exhibited disregard

for proper distribution of judicial functions in the

federal judicial system. That distribution represents

a deliberate judgment that trial courts are better

equipped than appellate courts to evaluate evidence

and to make factual findings. Hazelwood School Dis

trict v. United States, supra, 53 L. Ed. 2d at 781. See,

e.g., Uebersee Finanz-Korporation v. McGrath, 343

U.S. 205, 212-13 (1952); Busey v. District of Columbia,

319 U.S. 579 (1943).

The Fifth Circuit invaded the trial court’s domain

not only by making de novo factual findings but also

by restricting the trial court’s discretion to fashion

23

appropriate relief. Once a plaintiff has established a

violation of Title V II, the selection of remedies and

framing of decrees become the duty of the trial court

which is vested with discretion to model its judg

ment to fit the exigencies of the particular case. Dayton

Board of Education v. Brinkman, ____ U.S ___ 1 53

L. Ed. 2d 851, 862 (June 27, 1977); Albemarle Paper

Co. v Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 421-22 (1975); Interna

tional Salt Co. v. United States, 332 U.S. 392 (1947)

See also United States v. Greater Buffalo Press Inc

402 U.S. 549, 556-57 (1971).

Contrary to this fundamental principle, the Fifth

Circuit on two separate occasions directed that plain

tiffs are entitled” to equitable relief,,<l on two sep

arate occasions stated the District Court “ must” issue

particular injunctions or that an injunction is “ neces

sary” ,17 on seven occasions directed that the District

Court “ should” issue particular injunctions,18 and on

four separate occasions so strongly suggested, in in

creasingly imperative terms, that the District Court

grant certain relief as to afford the trial court no re

alistic choice or room for discretion.19 Moreover, on one

occasion the Fifth Circuit in effect issued its own in

junction when it directly ordered Stockham to as-

16 App. 51 (Wonderlic test); App. 67 (age requirements).

. ” App- 88 ( s e d a t e d restrooms) ; App. 89 (selection and train-

ing lor craft and supervisory positions).

18 App 89 (high school and age requirements for apprenticeship

training); App. 90 (written guidelines for use by supervisors in

selecting apprenticeship candidates; development of apprentice se

lection procedures; development of guidelines for supervisor selec-

tion; restructure of supervisor selection process; recruitment at

black schools; posting job vacancies and qualifications).

19 App. 88-90 (segregation of facilities); App. 91-93 (type of

seniority relief); App. 93-96 (backpay); App. 96-97 (front pay).

24

certain and publicize objective qualifications for ap

prenticeships. (App. 90).

The task of a court of appeals is limited:

I f [the Court of Appeals] concludes that the find

ings of the District Court are clearly erroneous, it

may reverse them under Fed. Rules Civ. Proc.

52(a). I f it decides that the District Court has

misapprehended the law, it may accept that Court’s

findings of fact hut reverse its judgment because

of le°-al errors. Dayton Board of Education v.

Brinkman,------U .S .------- , 53 L. Ed. 2d 851, 862

(June 27, 1977).

The Fifth Circuit neither undertook nor understood

either function. While giving lip service to the

clearly erroneous rule, it reevaluated evidence de novo

and substituted its intuitive judgment for that of the

trial court. After overturning legal standards, it de

veloped its own findings of fact to which it applied

the revised legal standards. Though it remanded the

case to the District Court for “ framing” of relief, that

task seemingly would be ministerial rather than dis

cretionary because of the Court of Appeals ligid di

rections.

In the context of unequivocal usurpation of trial

court functions, the decision herein of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit pre

sents the clearest kind of case for the application of

the supervisory powers of this Court in the interest of

preserving orderly and efficient operation of the fed

eral judiciary. By granting this petition, this Court

can eliminate needless anneals with, duplicitous re

views of fact, minimize incorrect appellate disposi

tions, and definitively clarify the role of trial courts

in evaluating statistics and other evidence.

25

3' m^n?nS ? - ° f Q “ an,“ aUve Differences In Educalional Attain-

ment. u nXverSdJy Recognized To Influence Earnings, Cannot

Employees ComP ^ 9 Earnings of White and Black

Job applicants of whatever race bring with them to

their employment cognitive skills and other

mtics over which t ~ ' employer has no control and

which may have nothing whatever to do with nn

pjover s job i B M f c for selection but neverthe-

• j— iT ‘ dj ect an<* mwirnlilf imijS Z t E T r

cTuTiT^ 1 g, \ mamifacturiug plant such pro

ductivity characteristics may wholly explain differ

ences m earnings between black employees and white

employees winch might otherwise erroneously be at-

Fonllfed raCiaIly discriminatory policies. This

taneeVf1 othergettings, has acknowledged the irnnor-

tance o f one of these factors, education, as an influ-

ence in all aspects of life. In Brown v. Board of Edi

luffed 7 U‘S- 483’ 493 (1954)’ this Court c o t

h Vi i \S a p,rinciPal instrument in awaken- ng the child to cultural values, and in preparing

him for later professional training and in helm

mg him to adjust normally to his’ environment

In these days, it is doubtfiil that a i ^ X d ^ y

reasonably be expected to succeed in fife if he is

denied the opportunity of an education

Using a multiple regression statistical technique

similar to that utilized by plaintiffs in Wade v Mis-

m x Cir S T l T ? Xtension 528 F.2d 508

• f C ^ 191 6 ’̂ Dr* James Gwartney, a labor econo-

mist on the faculty of Florida State University, iden-

V L i10SC f,actors suscePtible to measurement which

affected employee earnings at Stockham and reached

26

the conclusion that there was no statistically signifi

cant difference between the compensation received by

white and black employees with similar productivity

characteristics. The trial court relied on Dr. Gwart-

ney’s study which was not challenged by opposing ex

pert testimony and concluded that Stoclcham provided

equal earnings opportunities to both races in its work

force.

The Fifth Circuit, while not rejecting the validity

of the analytical technique, dismissed Dr. Gwartney’s

study as “ factually inadequate” and criticized his

choice of productivity determinants. Among the fac

tors rejected, the Court of Appeals concluded that Dr.

Gwartney improperly considered educational attain

ment in assessing productivity. In cavalierly dismiss

ing the Gwartney study demonstrating the impact of

productivity factors on earnings at Stockham, the

Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals committed the same

error as did the Eighth Circuit in Hazelwood School

District v. United States, supra, by totally disregard

ing the possibility that prirna facie statistical proof

can be rebutted at the trial level.

In making its intuitive determination, the Court of

Appeals casually rejected a widely-observed and doc

umented phenomenon that, on average, a higher edu

cational level will yield higher earnings regardless of

race. The Fifth Circuit discarded educational attain

ment for two reasons:

The fallacy in this conclusion [i.e., that education

impacts earnings] stems from two facts: ( 1 )

as the defendant concedes, education is not a job

requirement at Stoclcham, and (2) white employ

ees at Stockham have more education than blacks.

Thus, adjusting for education in a regression an

27

alysis of earnings where education is not related

to job performance and where one race is more

educationally disadvantaged than another, masks

racial differences in earnings that may be ex

plainable on the basis of discrimination. Certainly

such differences cannot fairly be explained on the

basis of a factor, such as education, concededly ir

relevant to adequate job performance. (App. 41).

The Fifth Circuit’s error evolves from the sophistry

of its argument: education is not a requirement for

employment (or placement on a job) and, therefore,

it is irrelevant” to adequate job performance. Logi

cally, tlm conclusion does not necessarily follow from

the premise. For example, an employer may not have

a policy that dictates an “ acceptable” maximum level

of employee absenteeism. Yet excessive absenteeism

adversely affects productivity on the job without ref

erence to the employer’s general policy requirements

on absenteeism.

Embracing a “ warm body” hypothesis, the Court of

Appeals categorizes employees as either “ qualified”

or “ not qualified.” Within each group, in the Court’s

view, employees are fungible. The Court’s analysis

does not acknowledge that employees typically exhibit

a spectrum of competencies, or the statistically-sup

ported observation that education favorably influences

earnings.

Although not articulated, the Court confused the

mandate of Griggs v. Duke Poiver Co., 401 U.S. 424

(1971), that employee selection devices have a demon

strable relationship to job performance with widely-

held economic principles that productivity factors

have a statistically significant impact upon employee

28

earnings. The two concepts are logically independent

and not inconsistent.

The economic literature, without important excep

tion, acknowledges the premise that on average edu

cational attainment favorably influences earnings. One

authority observes:

The conviction that more education leads to

higher income finds extensive support in statis

tical data. The simple correlation between educa

tional attainment is very strong and consistent:

more years of education do lead to higher income.

B. R. Schiller, The Economics of Poverty and

Discrimination 98-99 (1973).

See also, e.g., L. C. Thurow, Poverty and Discrimina

tion 70-71 (1969); W . L. Hansen, et al., “ Schooling

and Earnings of Low Achievers” , 60 The American

Economic Review 409 (1970). This is so largely be

cause level of education serves as a proxy for a measure

of cognitive skills and motivation attributes. See B. A.

Weisbrod, “ Investing in Human Capital” , The Daily

Economist 149 (1973). The fact that a specified educa

tion level is not a job entrance requirement is not rele

vant to productivity.80

The common-sense recognition that educational at

tainment increases earnings in the workplace escaped

the Court of Appeals, despite uncontradicted expert

testimony in the record. I f the Fifth Circuit s rejec

tion of education as a matter of law as a factor in

fluencing earnings is permitted to stand, the conse-

i° The Fifth Circuit’s opinion suggests that seniority, which

“ favors” blacks in Dr. Gwartney’s study, is a permissible produc

tivity factor despite the fact that there are no seniority or tenure

requirements for jobs at Stockham. (App. 40-42).

29

quences for future employment discrimination litiga

tion will be dramatic. The Court, without anv regard

for the community of professional knowledge, rejects

weighing a factor which demonstrably impacts earn

ings. By precedent, the Court of Appeals forecloses

future litigants from exploring the productivity char

acteristics of their work forces.

The Fifth Circuit’s approach is justified in a voter

registration or jury selection case where voters, or

jurors, are fungible as citizens. However, the ana

lytical framework is illogical and inappropriate in the

employment context. Economists conclude that many

characteristics influence employment productivity;

some characteristics may not be distributed in a ra

cially balanced fashion in a particular employment

environment. The Court of Appeals precluded, as a

matter of law, consideration of productivity factors

in general, and education in particular, as a possible

explanation of earnings differentials.

The importance of this issue cannot be overstated.

I f the inflexible approach of the Court of Appeals

survives, then employers will be required to compen

sate employees according to race rather than produc

tivity- That result has national implications which

undermine this Court’s rationale in Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971), that employee quali

fications must serve as the determinants of job success.

The intervention of this Court is necessary to assure

that differences evolving from objective productivity

characteristics will not, in and of themselves, consti

tute evidence of a violation of Title Y II of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964.

30

vn. CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the petition for a writ

of certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

D ouglas A rant

John J. Coleman, Jr.

James P. Alexander

W m . M ichael W arren, Jr.

1500 Brown-Marx Building

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

(205) 252-4500

Attorneys for Petitioner

Stockham Valves and Fittings, Inc.

Of Counsel:

B radley, A rant, R ose & W hite

L inda A. B unsey

Robert K . Spotswood

1500 Brown-Marx Building

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

(205) 252-4500