Georgia v. Ross Brief for Appellant in Forma Pauperis

Public Court Documents

November 23, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Georgia v. Ross Brief for Appellant in Forma Pauperis, 1976. d547e22e-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f3f018d5-b88d-40d8-948c-0b3234e67385/georgia-v-ross-brief-for-appellant-in-forma-pauperis. Accessed February 26, 2026.

Copied!

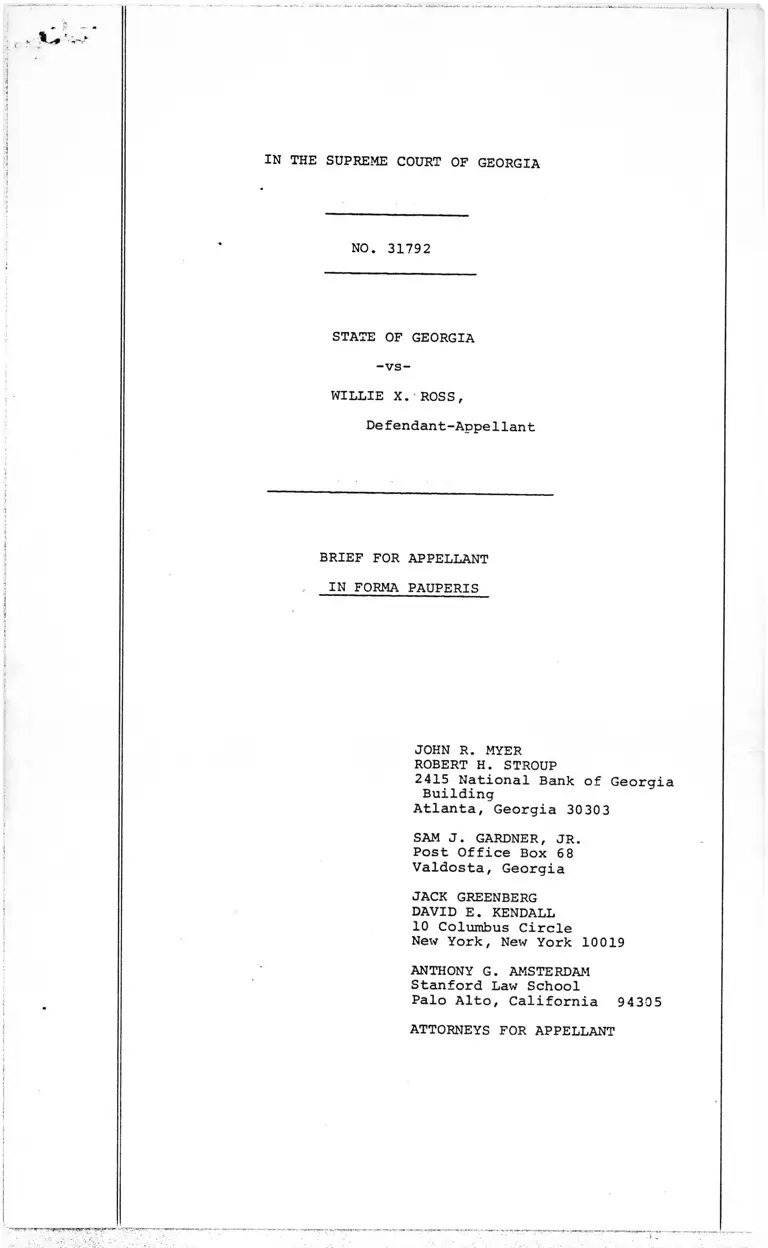

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

NO. 31792

STATE OF GEORGIA

-vs-

WILLIE X.ROSS,

Defendant-Appellant

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

IN FORMA PAUPERIS

JOHN R. MYER

ROBERT H. STROUP

2415 National Bank of Georgi Building

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

SAM J. GARDNER, JR.

Post Office Box 68

Valdosta, Georgia

JACK GREENBERG

DAVID E. KENDALL

10 Columbus Circle New York, New York 10019

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAMStanford Law School

Palo Alto, California 94305

ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLANT

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

XSTATE OF GEORGIA XX-vs- X NO. 31792XWILLIE X. ROSS, XXDefendant-Appellant. XX_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ X

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

PART ONE

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Defendant WILLIE X. ROSS was convicted on March 13, 1974

in the Superior Court of Colquitt County of the following three

offenses: murder of T. J. Meredith, armed robbery of Robert Lee

and Kidnapping of Wandell Normal. By a final judgment entered

on the same date, he was sentenced to death, life imprisonment,

and twenty years imprisonment, respectively, upon these three

convictions.

On November 18, 1974, this Court affirmed defendant's

convictions and sentences, and on December 17, 1974, this Court

denied the rehearing petition. Ross v. State, 233 Ga. 361, 211

S. E. ed 356 (1974). On March 17, 1975, defendant filed a

petition for writ of certiorari in the Supreme Court of the

United States, Ross v. Georgia, No. 74-6207. On July 6, 1976,

that Court denied certiorari. Ross v. Georgia, 49 L. Ed. 2nd

1217 (1976) and on October 4, 1976, that court denied a re

hearing petition (45 U.S.L.W. 3255) which petition defendant had

filed on July 20, 1976.

On October 8, 1976, this Court issued remittitur in this

case to the Superior Court of Colquitt County, and on October

25, 1976, that Court set November 12, 1976 as the date for

defendant's execution.

On October 14, 1976, defendant filed in the Superior Court

of Colquitt County a"Petition for a Declaratory Judgment and

Motion for a New Presentence Hearing" (R. 5). In that petition,

defendant asserted that his "death sentence was imposed on March

13, 1974, at a time when the constitutionality of the 1973

death penalty statute was in question, and the jury which

sentenced petitioner to death may have been influenced by its not

unreasonable belief at that time, that this sentence could not

in fact be "constitutionally executed" (R. 6). In that motion,

defendant prayed that the Superior Court "afford defendant a

presentence hearing, as authorized by Ga. Code Ann. §§27-2503 (b) ,

27-2534.1 (1975 Supp.), at which either the court polls the

original penalty jury on the issue of sentence in light of the

supervening legal developments or at which the question of

defendant's sentence may be redetermined by defendant's original

jury, a new jury, or the Court, in light of the fact that the

Supreme Court of Georgia and the Supreme Court of the United

States have upheld the constitutionality of the Georgia death

penalty statute" (R. 6). On the same date, defendant also filed

a Motion for Hearing on his petition "to assure that the setting

of such execution date would be conformable to equitable and

constitutional requirements" (R. 3).

By order of the Superior Court of Colquitt County entered

October 18, 1976, defendant's Motions were denied, including

defendant's motion for a hearing (R. 8-9). The trial court

stated in denying both the petition and the hearing, that "The

Georgia Death Penalty Act, Ga. Laws 1973, pp. 159-172, was held

to be constitutional and valid prior to the date (March 13,

1974) upon which the jury in this case imposed the death penalty

in the case of Coley v. State, 231 Ga. 829" (R. 8). On October

21, 1976, defendant filed a Notice of Appeal from the order of

October 18, 1976 (R. 1). This appeal to this Court follows.

-2-

PART TWO

ENUMERATION OF ERRORS

1. The trial court erred in denying defendant's Petition

for a Declaratory Judgment and Motion for a New Presentence

Hearing in violation of defendant's rights to due process

guaranteed by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

United States Constitution, and the Constitution of the State of

Georgia.

2. The trial court erred in denying defendant's motion for

hearing on his Petition for a Declaratory Judgment and Motion

for a New Presentence Hearing in violation of defendant's rights

to due process guaranteed by the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment, United States Constitution and the Consti

tution of the State of Georgia.

PART THREE

ARGUMENT

I. THE TRIAL COURT ERRED IN DENYING DEFENDANT'S

MOTION TO CONSIDER WHETHER THE LEGAL UN

CERTAINTY OF THE GEORGIA DEATH PENALTY STATUTE IMPROPERLY INFLUENCED THE SENTENCE OF DEATH

The issue presented in this appeal is whether the trial

court erred in denying defendant's motion for hearing on the

question whether the jury which originally imposed the sentence

of death firmly believed that such sentence would in fact be

carried out. Only the sentencing phase of his case is at issue

in this appeal.

In Gregg v. Georgia, ____ U. S. ____, 96 S. Ct. 2909

(1976), the United States Supreme Court held that the Georgia

capital punishment statute, Ga. Code Ann. §27-2534.1, on its

face for the crime of murder, did not violate cruel and unusual

punishment prohibition of the Eighth Amendment, United States

Constitution. However, in upholding the Georgia statute, the

-3-

United States Supreme Court also recognized the unique consti-

1/tutional role of the sentencing jury in capital cases. Mr.

Justice Stewart's opinion states, "Jury sentencing has been

considered desirable in capital cases in order to 'maintain a

link between contemporary community values and the penal system -

a link without which the determination of punishment could hard

ly reflect 'the evolving standards of decency that mark the

progress of a maturing society.'" But it creates special

problems." 98 S. Ct. at 2933 (Emphasis added).

One important element of the "special problems" of

jury sentencing in capital cases is the total lack of experience

of such juries to perform the awesome responsibility which the

Georgia legislature has given to them. Mr. Justice Stewart's

opinion in Gregg explicitly recognized this lack of experience:

"Since the members of a jury will have had little, if any,

previous experience in sentencing, they are unlikely to be

skilled in dealing with the information they are given" 96 S.Ct.

at 2934.

Mr. Justice Stewart's opinion concluded that the

2/

Georgia statute passed Furman v. Georgia muster because "the

concerns expressed in Furman that the penalty of death not be

imposed in an arbitrary or capricious manner can be met by a

T7Historically, at common law, the jury acted solely as the findex

of fact and the sentencing function was performed by the judge

in all cases. The same rule prevails in most American juris

dictions for non-capital sentencing. However, states which

retain the death penalty have generally provided for jury sen

tencing in capital cases. See H. Kalver & H. Zeisel, The American Jury, 301 n. 1 (1966),Comment, Jury Sentencing m

Virginia, 53 Va. L. Rev. 968 (1967).

408 U. S. 238 (1972).2/

-4-

carefully drafted statute that ensures that the sentencing

authority is given adequate information and guidance." 96 S. Ct.

2935 (Emphasis added).

The constitutional uniqueness of the death penalty was

similarly recognized by the Court in Woodson v. North Carolina,

U. S. ___, 96 S. Ct. 2978 (1976), where Mr. Justice Stewart's

opinion stated, "This conclusion rests squarely on the predicate

that the penalty of death is qualitatively different from a

sentence of imprisonment, however long. Death, in its finality,

differs more from life imprisonment than a 100 year prison term

differs from one of only a year or two. Because of that

qualitative difference, there is a corresponding difference in

the need for reliability in the determination that death is the

appropriate punishment in a specific case" 96 S. Ct. at 2992

(Emphasis added). See also, Mario v. Beto, 434 F. 2d 29, 33

(5th Cir. 1970) ("the magnitude of a decision to take a human

life is probably unparalled in the experience of a member of a

civilized society").

The Gregg and related decisions place a heavy emphasis

on the fact that because the jury is the link with the standards

of society, the sentencing jury must be given adequate informa

tion and guidance to minimize the special problems which

capital sentencing poses. In light of the constitutional re

quirement of certainty and reliability, defendant was entitled

to be heard on his motion to determine whether the sentence im

posed on him by this jury was so chosen by a jury which believed

the sentence would not in fact be carried out. Defendant sub

mits that the.uncertainty surrounding the constitutionality of

the Georgia statute at the time of his sentence prevented the

jury from possessing the full guidance of certainty required.

There can be no dispute that following the decisions

-5-

of the United States Supreme Court in Furman v. Georgia, et al.,

substantial widespread uncertainty existed as to whether any

death sentence would be permissible, and if so, what types of

sentencing schemes. When the State of Georgia adopted

§27-2534.1, this uncertainty existed among lawyers, judges and

commentators. Indeed, several commentators had expressed the

opinion, see, e^ g_̂ , Note. Furman v. Georgia and Georgia's

Statutory Response, 24 MERCER L. REV. 891, 936 (1973); Note,

Discretion and the Constitutionality of the New Death Penalty

Statutes, 87 HARV. L. REV. 1690, 1704 (1974), that the new Geor

gia capital punishment statute was invalid under the Furman 3/ ------

test. In this state of affairs, it is likely that defendant's

jury condemned him without believing that his sentence would

actually be executed.

4/There is evidence from other states that in the period

before the Supreme Court of the United States upheld the per se

constitutionality of the death penalty on July 2, 1976, some

juries imposed the death penalty while firmly believing that the

sentence would never be executed. This so-called "Private

Slovik" syndrome was noted by Mr. Justice Stewart during the

argument of a recent death case (Fowler v. North Carolina) in the

United States Supreme Court:

3 ^ — -----------------------

Similar uncertainty prevailed concerning the constitutionality

??.death Penalty statutes in other states. Cf., Comment, The New Illinois Death Penalty: Double Constitutional Trouble, 5 Loyola Univ. (Chi.) lT 351 (1974) which stated:

"Since the Furman decision was shrouded

with such undertainty, some legislative grouping for the constitutional answers -is to be expected. Hopefully, much of

the haze surrounding the issue of capital

punishment in the United States will'be removed when the United States Supreme

Court grapples with post-Furman death

penalty statutes" at 392.

1/See, e. g., Leavy, Mamie Lee Ward on Death Row. 5 M.S. 70. 106 (19 75) ------------------------

-6-

Mr. Justice Stewart said that failures

[of responsibility] were nonetheless

possible. . .and he referred to the

case of the sole U. S. soldier executed

for desertion in World War II. Everyone

who could have stopped that prosecution, he said, failed to do so.

43 U.S. L. W. 3578 (U. S. April 29, 1975).

This "Slovik syndrome" takes its name from the following

account of the execution of the only American soldier executed

during World War II by the United States. Compare, HUIE, THE

EXECUTION OF PRIVATE SLOVIK 169 (5th Dell ed. 1974):

"I think every member of the court thought

that Slovik deserved to be shot; and we

were convinced that, for the good of the division, he ought to be shot. But in

honesty — and so that people who didn't

have to go to war can understand this thing — this must be said: I don't think a

single member of that court actually be

lieved that Slovik would ever be shot. I know I didn't believe it. . . . 1 had no

reason to believe it. . . .1 knew what the

practice had been. I thought that the

sentence would be cut down, probably not

by General Cota, but certainly by Theater

Command. I don't say that this is what I

thought should happen; I say it is what I felt would happen. I thought that not

long after the war ended — two or three

years maybe — Slovik would be a free man."

Under these circumstances, inquiry should now be had

into the question whether the death penalty was properly imposed

upon the defendant. The existence of such legal uncertainty

amounts to a usurpation of the jury function - the responsi

bility to impose the sentence of death upon a defendant only if

the jury truly knows that such sentence will be carried out. As

the Court states in the original appeal from this defendant's

conviction, "It is the reaction of the sentencer to the evidence

before it which concerns this Court and which defines the limits

which sentences in past cases have tolerated, whether before or

after Furman v. Georgia. When a reaction is substantially out

of line with reaction of prior sentences, then this Court must

set aside the death penalty as excessive." Ross v. State, 233

-7-

361, 211 S. E. ed 356, at 360. The true "reaction of the

sentencer" insofar as it serves the link with the community can

be assayed only from a jury acting with firm knowledge that its

sentence is capable of execution.

In an analogous context, this Court ruled that comments

of the district attorney to the jury that this Court had power

to reverse and set aside death sentences constituted reversible

error as to the sentence. Prevatte v. State, 233 Ga. 929, 214

S. E. 2d 365 (1975). In Prevatte, this Court stated. ". . .the

inevitable effect of the prosecutor's remarks to the judge in

the jury's presence was to encourage the jury to attach diminish

ed consequence to their verdict, and to take less than full

responsibility for their awesome task of determining life or

death for the prisoners before them" 214 S. E. 2d at 367 (Empha

sis added). The legal uncertainty of the constitutionality of

the Georgia death penalty statute may have had the inevitable

effect of encouraging the jury to attach diminished consequence

to their sentence of defendant and encouraging them to take less

than full responsibility for the awesome decision of condemning

Willie Ross to die.

Similarly, the lack of certainty about the statute's

constitutionality may have influenced the decision to impose the

sentence as the jury weighed the imponderables of whether to give

defendant life or death. Compare Prevatte, supra, at 368, "Where

one of the jury's functions is to impose punishment for crime,

a reference by the prosecutor to the defendant's right to appeal

is more likely to be considered reversible error if a death

penalty is subsequently imposed, no doubt for the reason that in

weighing of imponderables it cannot be concluded that the jury

were not influenced by such statements to impose more severe

punishment than their unbiased judgment would have given."

The trial court's denial of a hearing to permit

-8-

defendant to establish whether this uncertainty improperly

influenced the sentencing decision of the jury denied him due

5/

process of law.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, this Court should reverse

the decision of the trial court and order that defendant be

permitted a hearing on the motion.

Respectfully submitted,

— * --------------------------------------------

ROBERT H . STROUP2415 National Bank of Georgia Bldg.

Atlanta,Georgia 30303

(404) 522-1934

SAM J. GARDNER, JR.

P. 0. Box 6 8

Valdosta, Georgia

JACK GREENBERG

DAVID E. KENDALL

10 Columbus Circle New York, New York 10019

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford Law School Palo Alto, California

ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLANT

Morrisey v. Brewer, 408 U. S. 471 (1972); Bell v. f. 422n s 535 (19 71) ; Groppi v. Wisconsin, 400 U. S. 505 (1971);

Goldberg v. Kelly, 39 7 U. S. 25 4 (iT/O) ; Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 u.""s. 371 ("1970) ; Sniadach v. Family Finance Corp., 395 U.~.

337 (1969); North Georgia Finishing, Inc, v. Di-Chem, Inc^, 419

U. S. 601 (1975). Thp Supreme Court recognized in Gregg the

great importance of procedural safeguards, "[w]hen a defendant s

life is at stake." 96 S. Ct. at 2932, citing Powell v. Alabama,

287 U. S. 45,71 (1932), and Reid v. Covert, 354 U. S. 177 (1957)

-9-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I HEREBY CERTIFY that I have this day served copies of

the foregoing Brief for Appellant upon:

Honorable H. Lamar Cole

District Attorney P. 0. Box 99

Valdosta, Georgia 31601

and

Honorable Arthur K. Bolton Attorney General

132 Judicial Building

Atlanta, Georgia 30334

by depositing copies of same in the United States Mail, first-

class postage prepaid.

This day of November, 1976.

'R© fencer

JOHN R. MYER /