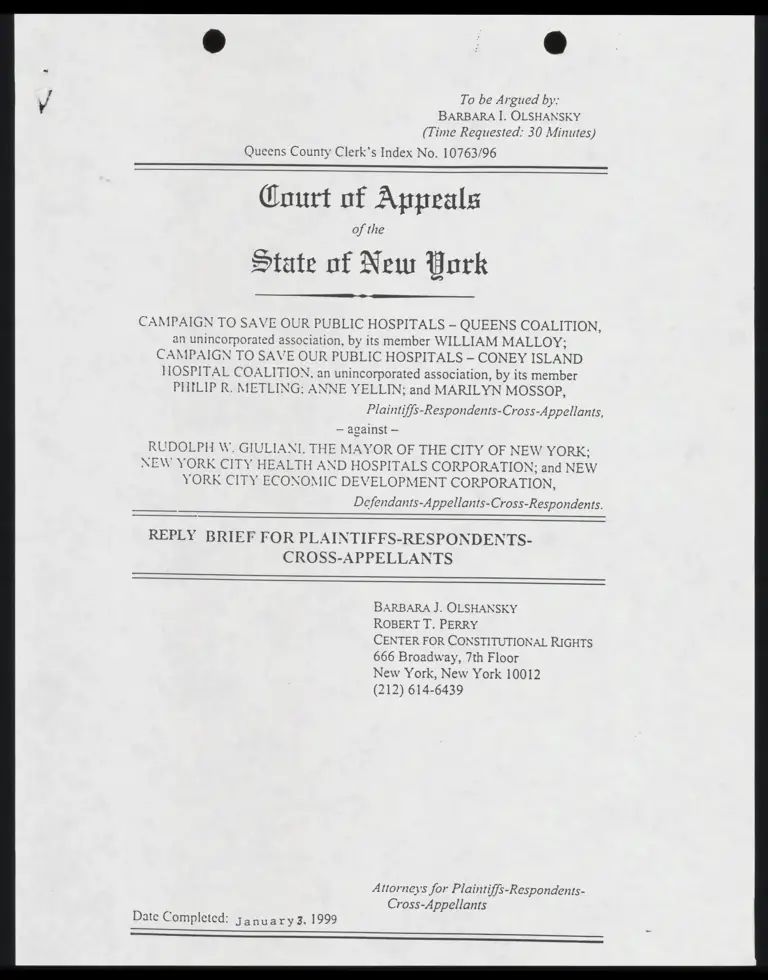

Reply Brief for Plaintiffs-Respondents-Cross-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 3, 1999

22 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Campaign to Save our Public Hospitals v. Giuliani Hardbacks. Reply Brief for Plaintiffs-Respondents-Cross-Appellants, 1999. ca5d874f-6835-f011-8c4e-0022482c18b0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f4201609-833d-48a9-955a-0bb37dd26a72/reply-brief-for-plaintiffs-respondents-cross-appellants. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

To be Argued by:

BARBARA I. OLSHANSKY

(Time Requested: 30 Minutes)

Queens County Clerk’s Index No. 10763/96

Court of Appeals

of the

State of New York

CAMPAIGN TO SAVE OUR PUBLIC HOSPITALS — QUEENS COALITION

an unincorporated association, by its member WILLIAM MALLOY:

CAMPAIGN TO SAVE OUR PUBLIC HOSPITALS — CONEY ISLAND

HOSPITAL COALITION, an unincorporated association, by its member

PHILIP R. METLING: ANNE YELLIN; and MARILYN MOSSOP,

Plaintiffs-Respondents-Cross-Appellants,

— against —

RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI. THE MAYOR OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK;

NEW YORK CITY HEALTH AND HOSPITALS CORPORATION; and NEW

YORK CITY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION,

Defendants-Appellants-Cross-Respondents.

:

REPLY BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-RESPONDENTS-

CROSS-APPELLANTS

BARBARA J. OLSHANSKY

ROBERT T. PERRY

CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS

666 Broadway, 7th Floor

New York, New York 10012

(212) 614-6439

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Respondents-

Cross-Appellants

Date Completed: January 3, 1999

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .ococitietsrniseessssscessncssrsssssavssrsssssssnssens ii

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT ....00tcctrsosnniresnsosinimennssssinsenesrssnsnees 1

ARGUMENT . vnsniamrnssninsssnsssrosssnssvrssssonosesinsssresasnnsosgsnnssses 1

I. APPELLANTS’ CLAIM THAT THE HHC ACT AUTHORIZES HHC TO

II.

UNDERTAKE THE CONEY ISLAND HOSPITAL TRANSACTION IS

WITHOUT BASIS AND MUST BE REJECTED ........cooiiiiiiiiiinnnn, 1

A. The Transfer Of Operational Control Over A Health Facility To A Private,

For-Profit Corporation Would Contravene The HHC Act .............. 1

B. The Terms of the Proposed Sublease of Coney Island Hospital Violate The

HHC Act and Contravene HHC’s Corporate Purpose .................. 7

APPELLANTS’ CLAIMS THAT ULURP DOES NOT APPLY TO THE CONEY

ISLAND HOSPITAL TRANSACTION AND THAT CONSENT OF THE CITY

COUNCIL IS NOT REQUIRED ARE MERITLESS .......ceviivviivinnnn. 14

CONCLUSION 7 sioner sss nis vininie das rnnsesivnssevnsssasnsnissnsionsoions seve vinaessies 17

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

FEDERAL CASES

Meriwether v. Garret, 1021.S.472, 26 L.Ed. 1971880) «isc vc obvi sini a dunn vunn'nins 14

STATE CASES

American Dock Co. v. City of New York, 174 Misc. 183, 21 N.Y.S.2d 943

(Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co. 1940), aff'd., 261 A.D. 1063, 26 N.Y.S.2d 704,

affd., 286 N.Y. 658, 36 N.E.2d 696 (1941) ee ay Ny SN ESE LS a i wih 14

Branford House, Inc. V. Michetti, 81 N.Y.2d 681, 603 N.Y.S.2d 290 (1990) ............... 4

Cotrone v. City of New York, 38 Misc. 2d 580, 237 N.Y.S.2d 487

(Sup: Ct. RINGS CE, 1000) or, us iets inins » sine of whe a 4 uiein ow wihAEr bin 5 hw a Hin arian a bn s 14

Council of City of New York v. Giuliani, 231 A.D.2d 178, 662 N.Y.S.2d 516

(2d Dept. 1907) os cir civic sd vin se ssn i is thie niet nae nn abet ea a Sn 3.5.7

Ellington Construction Co. v. Zoning Board Of Appeals

of Incorporated Village of New Hempstead, 77 N.Y.2d 114, 564 N.Y.S.2d 1001 (1990) ...... 4

Ferres v. City of New Rochelle, 68 N.Y.2d 446, 510 N.Y.S.2d 57 (1986) ................. 3

I ake George Steamboat v. Blais, 30 N.Y.2d 48, 281 N.E.2d 147, 330 N.Y.S.2d 336 (1972) .. 14

Long v. Adirondack Park Agency, 76 N.Y.2d 419, 559 N.E.2d 635,

55 N.Y. S. 204] (1000) is. i in iat a BN pn wan me or RAR Te Wr 4

Majewski v. Broadalbin-Perth Central School District, 91 N.Y.2d'577,

673 N.Y.S.2d4 966 (1998) ..... PE Re SER TREE SN JOPLIN OF JEN gg NCS 7

Matterof OnBank & Trust Co.. 90 N.Y.2d 725,663 N.Y. S.2d 389 (1998)... ... cvs sn sven 3

New York City Health and Hospitals Corp. - Goldwater Mem. Hospital v. Gorman,

113 Misc. 2d 33, 448 N.¥.S.2d 623 (Sup. CL. NY. Co. 1983) tevic c vais te svn svat adhe nine 2

Patrolmen’s Benevolent Ass’n v. City of New York, 41 N.Y.2d 205,

SOI N.Y. S20 8441070). cess ay vie sas a eB pe sen Te as amie a 7

Rodriguez v. Perales, 36 N.¥.2d 361,633 N.Y.S.2d232(1993) .......0viieeervivnnninny 3-4

Tribeca Community Assoc. Inc. v. New York State Urban Development Corp.,

ii

Index No. 20355/92 (April 13, 1993 Sup. Ct. N.Y"), aff’d,

300A D2dS36, 607 NY.S.2d 18(1% Dept. 1994) . . ... ..en 4 sts esse nde dais cna nd 15

Wavbro Corp. v. New York City Board of Estimate, 67 N.Y.2d 349, 493 N.E.2d 931,

SONY S270 C1980) i. arn ois on in i Vw hate aie ye ar A 4 Ca se 15

STATE STATUTES

New York State Constituhion, Article XVII... . ioe vc vinaivanide san srniiiv sins vies passim

New York City Charter Section 197... 0. ofl sd viteins sv rdnernina®s suva sas amass 16

New York City Charter Section 384... ch ceva divs sive srs dala nein vd salaries 16

New York Clty Charter SECHOM TIS2 ... 0 ui cv cv sn von wa sivvhieis svi visitas o Faine + 4 16, 17

Unconsolidated Laws BS 7B ESO. vo. feria ire dis nisin Seles iy Se passim

MISCELLANEOUS

Final Report of the City Charter Revision Commission 'v. ....cv va vere vanes nnns 15,17

New York City Commission on Delivery of Personal Health Services,

Comprehensive Community Health Services for New York City (Dec. 1967) .............. 3

New York City Comptroller Alan Hevesi, Analysis of Fundamental Issues

That Have Yet To Be Resolved (November 7,'1996) ...... cvs. rivivanenan passim

Eleventh Annual Report of the Temporary Commission of Investigation

of the State of New York to the Governor

and the Legislature of the State of New York (1969) .......... (din nmin en an ale a Reig 6

111

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

There is no dispute among the parties regarding the nature of New York City’s

constitutional obligation to provide comprehensive health care services for its indigent and

uninsured residents, or the New York City Health and Hospital Corporation’s (HHC) statutory

obligations to fulfill this mandate through its operation of the municipal hospital system. The

public hospital system operated by HHC exists to fulfill the essential public and governmental

function of providing critical physical and mental health care services for City residents who

cannot afford to be cared for by private hospitals. Ca 590. The proposed sublease of Coney

Island Hospital to PHS-NY, a private, for-profit corporation, begins the dismantling of this

constitutionally and statutorily mandated system.

Appellants have again failed to proffer any persuasive argument for their twice-rejected

position that the HHC Act provides HHC with the authority to undertake the Coney Island

Hospital transaction. Rather, the arguments presented in their reply brief rest on both a

misrepresentation of the factual basis of the transaction and a misapprehension of the HHC Act,

and therefore must be rejected.

ARGUMENT

I. APPELLANTS’ CLAIM THAT THE HHC ACT AUTHORIZES HHC TO

UNDERTAKE THE CONEY ISLAND HOSPITAL TRANSACTION IS

WITHOUT BASIS AND MUST BE REJECTED

A. The Transfer Of Operational Control Over A Health Facility To A Private,

For-Profit Corporation Would Contravene The HHC Act

Appellants’ claim that the Coney Island Hospital transaction is consonant with the

mandates of the HHC Act completely ignores Respondents’ argument as well as the language

and the structure of the Act. Under no credible interpretation does the statute permit the

transaction at issue.

Adding little, if any, new analysis, Appellants merely reiterate the argument that §

7385(6) of the Act, which provides that HHC may acquire and dispose of real property,

including a health facility, "for its corporate purpose" after it holds a public hearing and obtains

the consent of the Board of Estimate, provides HHC with the authority to undertake the proposed

sublease of Coney Island Hospital. See App. Reply at 2-5. As Respondents’ noted in their

opening brief, however, that overbroad reading of § 7385(6) is belied by the HHC Act’s plain

statement of HHC’s “corporate purpose” and the clear delineation of the limited circumstances

in which HHC may delegate its operational and management authority over a public health

facility.

The HHC Act’s “Declaration of Policy and Statement of Purposes” (“Declaration of

Policy”) states, in particular, that the City’s hospitals:

are of vital and paramount concern and essential in providing comprehensive care and

treatment for the ill and infirm, both physical and mental, and are thus vital to the

protection and promotion of the health, welfare and safety of the inhabitants of the state

of New York and the city of New York.

HHC Act § 7382. The Declaration of Policy further states that HHC’s exercise of its functions,

powers and duties “constitutes the performance of an essential public and governmental

function.” Id. (emphasis supplied). The Declaration of Policy specifically charges HHC with

[4 the duties of operating and maintaining the public hospitals “in all respects for the benefit of the

people of the state of New York and the city of New York.” Id. (emphasis supplied); New York

City Health and Hospitals Corp. - Goldwater Mem. Hosp. v. Gorman, 113 Misc.2d 33, 448

N.Y.S.2d 623 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co. 1982). Finally, the Declaration of Policy specifies that the

HHC-run hospitals must provide “high quality, dignified” care to “those who can least afford

such services.” HHC Act § 7382; New York State Constitution, Article XVII.

To ensure that HHC had the requisite authority to fulfill the City’s constitutional

obligation to provide indigent care, the Legislature mandated that the City enter into an

agreement with HHC “whereby [HHC] shall operate the hospitals then being operated by the city

for the treatment of acute and chronic diseases . . ..” HHC Act § 7386(1)(a) (emphasis

supplied). Plainly, the Legislature intended that the governmental function of, and responsibility

for operating the municipal hospitals would be vested in HHC. See Council of City of New

York v. Giuliani, 231 A.D.2d 178, 181, 662 N.Y.S.2d 516, 518 (2d Dept. 1997) (“The

Legislature clearly contemplated that the municipal hospitals would remain a governmental

responsibility and would be operated by HHC as long as HHC remained in existence.”).

Appellants similarly ignore the redundancy problem created by their overbroad

construction of § 7385(6). As Respondents observed in their opening brief, Appellants’

expansive interpretation of § 7385(6) as providing HHC with the authority to transfer operational

control over a public hospital to a private entity, would render superfluous § 7385(20), which

permits HHC to perform all or part of its functions through a wholly-owned subsidiary public

benefit corporation, so long as the subsidiary is subject to the same statutory limitations as those

imposed upon HHC. See Resp. Br. at 34-35. The implicit authority to undertake such a

delegation created by § 7385(6) would obviate the need for the Hotels authority delineated in §

7385(20), rendering § 7385(20) superfluous. The State Legislature could hardly have intended to

include a provision that “would be superfluous and could serve no purpose.” Ferres v. City of

New Rochelle, 68 N.Y.2d 446, 452, 510 N.Y.S.2d 57, 61 (1986). Appellants’ proposed

construction thus unequivocally contravenes the well-established principle that a statute must not

be construed a manner which would render any section mere surplusage. See, e.g., Matter of

OnBank & Trust Co., 90 N.Y.2d 725, 731, 665 N.Y.S.2d 389, 391 (1997); Rodriguez v. Perales,

3

86 N.Y.2d 361, 366, 633 N.Y.S.2d 252, 254 (1995); Branford House, Inc. v. Michetti, 81 N.Y.2d

681, 688, 603 N.Y.S.2d 290, 293-94 (1990).

Appellants likewise fail to address the anomalous effect created by their overbroad

construction of § 7385(6). On one hand, HHC would need Mayoral approval to transfer

operational control over a public hospital to a wholly-owned, subsidiary public benefit

corporation; on the other hand, it could transfer such control to a private, for-profit corporation

without Mayoral approval. Compare HHC Act § 7385(20) with HHC Act §§ 7385(6) and

7385(8). This Court has repeatedly rejected statutory interpretations which produce such an

“unreasonable” result. Ellington Constr. Corp. v. Zoning Bd. Of Appeals of Incorporated Village

of New Hempstead, 77 N.Y.2d 114, 124-25, 564 N.Y.S.2d 1001, 1007 (1990) (“Under

established rules, we must presume that the Legislature could not have intended respondent’s

interpretation of the statute which produces such unreasonable . . . consequences’); see Long v.

Adirondack Park Agency, 76 N.Y.2d 416, 420, 559 N.Y.S.2d 941, 942-43 (1990) (holding that a

“practical” approach to statutory construction is preferred “especially when an opposite

interpretation would lead to an absurd result that would frustrate the statutory purpose”).

As Appellants seemingly acknowledge, the State Legislature did not specifically grant

HHC the power to undertake a transaction like the one at issue. See App. Reply at 3-4 (“it

cannot be said that the Legislature had a specific intent to approve any particular type of

transaction”). Nor did it contemplate that HHC would effectively sell off the public hospitals.

Indeed, contrary to Appellants’ contention, see App. Reply at 3, the Legislature had “good

reason” to deny HHC the broad powers it currently claims, since it created HHC to fulfill a

critical public mission — the provision of comprehensive, quality health care services to the poor

and uninsured residents of the City. The legislative history shows that in doing so, it intended

4

only to establish a “mechanism” by which the City would meet its constitutional obligation to

provide care for the needy, not to divest the City of that obligation. See Letter of Mayor John V.

Lindsay to Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller, Governor's Bill Jacket, L. 1969, ch. 1016 (stating

that “in establishing a public benefit corporation, the City is not getting out of the hospital

business. Rather it is establishing a mechanism to aid it in better managing that business for the

benefit not only of the public served by the hospitals but the entire City health service system);

Ca 860. If HHC were permitted to delegate those responsibilities to a private, for-profit

corporation such as PHS-NY, it would be able to shift “the performance of an essential public

and governmental function,” HHC Act § 7382, to a non-public entity that would be neither

accountable to the public, nor constitutionally or statutorily mandated to operate the municipal

hospitals for the benefit of the public. Such a result would be plainly inconsistent with the Act

and the Legislature’s intent. HHC Act §§ 7382, 7385, 7386(1)(a); see Council of City of New

York v. Giuliani, 231 A.D.2d 178, 182, 662 N.Y.S.2d 516, 518 (noting that HHC was created “to

establish one entity accountable to the public to operate the municipal hospitals for the benefit of

the public.”). Both the language of the Act and the legislative history make clear that the

legislature intended that HHC itself perform the “essential public and governmental function” of

operating the municipal hospitals, and that the corporation “exercise its powers to provide and

deliver health and medical services to the public in accordance with policies and plans”

formulated by the City. HHC Act § 7386(7).

Given the clearly stated purposes of the HHC Act, Appellants’ argument that the

Legislature’s awareness of the privatization option, coupled with the absence of a specific

provision in the Act expressly forbidding the acquisition of a public hospital by a private, for-

profit corporation, indicates the Legislature’s implicit approval for such a transaction, see App.

5

Reply at 4 n.3, is simply ludicrous. To the contrary, the corporate purpose language of the Act

contains an express restriction upon the powers of HHC and provides a clear indication of the

Legislature’s intent in this regard:

[T]hat the creation and operation of the New York city health and hospital corporation, as

hereinafter provided, is in all respects for the benefit of the people of the state of New

York and of the city of New York, and is a state, city and public purpose; and that the

exercise by such corporation of the functions, powers and duties hereinafter provided

constitutes the performance of an essential public and governmental function.

HHC Act § 7382. Furthermore, the concerns about privatization expressed immediately prior to

the enactment of the HHC Act contextualizes Mayor Lindsay’s statement about the City’s

commitment to delivering health care to its citizens. See, e.g., Health Services Administration

Commission, Alternative Organizational Frameworks for the Delivery of Health Services in New

York City 4, 57 (Sept. 1967) (noting that the establishment of a public "Authority" to run the

public hospitals would not absolve the City of its responsibility to plan health services and to

ensure that comprehensive, quality care is available to all citizens); Commission on Delivery of

Personal Health Services, Comprehensive Community Health Services for New York City 51, 70

(Dec. 1967) (stating that the provision of health services was a “responsibility that belongs

inescapably to local government”).

Plainly, the operation of the public hospitals by HHC was intended to remain a

governmental responsibility because such an arrangement would ensure: (I) the continued

provision of comprehensive quality care to all City residents regardless of their ability to pay for

such services; (ii) the City’s continued responsibility for planning health services for its citizens;

and (iii) the continued accountability of the municipal hospitals to the public — the intended

beneficiaries of the public health care system. The Act makes clear that HHC was created to

assume responsibility for fulfilling the City’s constitutional obligation, and that HHC would

6

retain this function with respect to each health facility so long as the facility was needed to

provide health care services. See HHC Act § 7382; HHC Act § 7387(4) (providing that HHC

may surrender a health facility to the City if it determines that it is no longer required for its

corporate purposes and powers); Council of City of New York v. Giuliani, 231 A.D.2d 178, 181,

652 N.Y.S.2d 516, 518 (2d Dept. 1997).

In light of the clear articulation of these principles, Appellants’ contention that the

transfer of administrative, operational and managerial control over Coney Island Hospital to a

private, for-profit corporation is consistent with HHC’s corporate purposes and the legislature’s

express intentions in enacting the statute simply cannot be credited. See Majewski v.

Broadalbin-Perth Central School Dist., 91 N.Y.2d 577, 583, 673 N.Y.S.2d 966, 968 (1998) (“It is

fundamental that a court, in interpreting a statute, should attempt to effectuate the intent of the

Legislature.”); Patrolmen’s Benevolent Ass’n v. City of New York, 41 N.Y.2d 205, 208, 391

N.Y.S.2d 544, 546 (1976) (same).

B. The Terms of the Proposed Sublease of Coney Island Hospital Violate The

HHC Act and Contravene HHC’s Corporate Purpose

Respondents are compelled to correct Appellants’ characterization of the proposed

sublease which merely glosses over the salient aspects of the transaction in an obvious endeavor

to avoid addressing its patent conflict with HHC’s statutory mandate and New York City’s

constitutional obligations.

Appellants’ proclamation that PHS-NY will provide more care for the uninsured than

HHC currently provides,” App. Reply at 5, simply cannot be supported. Under the proposed

sublease, PHS-NY has agreed to spend 115 percent of the amount that HHC spent on indigent

care services in the base year. This means that PHS-NY has promised to provide health care

services to indigent and uninsured persons up to a specific charity care expense level. Proposed

Sublease § 28.05; Ca 473. The pertinent provision of the sublease thus establishes a cap on PHS-

NY's obligation to serve indigent and uninsured patients and defines PHS-NY's level of

obligation in terms of a fixed dollar amount. Id. It does not guarantee that PHS-NY will treat

every patient who needs care regardless of his or her ability to pay, nor does it even require that

PHS-NY treat a specific number of uninsured patients. In this regard, the proposed sublease

plainly represents a complete departure from HHC's mandate of providing care to all patients

without regard to insurance status or ability to pay.

PRE UE in the absence of any specified method for calculating the costs that will be

allocated to PHS-NY’s charity care obligation,’ one can only speculate about the level of services

that will be provided and the actual number of people that will be treated under the proposed

sublease. However, if, as Appellants’ example demonstrates, see App. Reply at 7, PHS-NY

calculates its charity care expenses allocable to the cap based on its charges (as opposed to

HHC’s method of calculating expenses based on its actual costs), then PHS-NY will incur higher

charity care expenses than that incurred by HHC for the same level of service. Ultimately, the

volume of service provided by PHS-NY may in fact be even lower than that currently provided

by HHC. See Hevesi, Fundamental Issues at 1-2; Ca 606-07.

Appellants’ apparently now contend that PHS-NY will not allocate the full fee that would

be charged to a paying patient to its charity care obligation, but rather only a percentage of this

'The proposed sublease does not specify how PHS-NY will calculate its charity care expense.

Thus, any calculation proffered by Appellants is purely speculative, since PHS-NY does not

appear to be bound under any agreement to a particular expense calculation methodology. See

Comptroller Alan Hevesi, Analysis of Fundamental Issues That Have Yet To Be Resolved

(November 7, 1996) (hereinafter “Fundamental Issues’) 1-2; Ca 606-07.

8

fee. See App. Reply at 7-8. However, while the use of this ratio may effect the rate at which

PHS-NY’s obligation is fulfilled (or the cap is met), it does not rebut the Comptroller’s

conclusion regarding the volume of service that will be provided given the traditional

discrepancy between fees charged and the actual costs of providing care. See Hevesi,

Fundamental Issues at 2; Ca 607. Moreover, without critical information such as PHS-NY’s

actual cost-fee ratio, the only conclusion that can be reached at this juncture is that PHS-NY’s

calculation of its charity care expense will be based on some portion of the fees it charges, not

the actual costs it incurs as is HHC’s current practice.

Furthermore, Appellants’ statement regarding the adequacy of the 115 percent cap to

meet the indigent care needs of the Coney Island community is seriously undermined by the

sublease provision that permits PHS-NY to avoid providing indigent care services above the cap

after the first year the cap is exceeded. Proposed Sublease § 28.01. This provision explicitly

permits PHS-NY to "manage access to health care in such a manner as it may deem appropriate

so as to avoid "Excess Incurrence" of indigent care costs if these costs exceed PHS-NY's cap in

any given year. Id. Moreover, the provision states that after the first year in which PHS-NY

reaches the cap, HHC cannot require PHS-NY to provide indigent care beyond that point:

"[N]othing herein shall give Landlord [HHC] the right to require Tenant [PHS-NY] to provide

Indigent Care in excess of such amount." Id.

In addition, even though HHC recognizes in the Environmental Assessment Form

(“EAF”)* that certain factors (that it labels "unanticipated") may increase the uninsured

’The Environmental Assessment Form was published by the City pursuant to the City

Environmental Quality Review (“CEQR”), 62 Rules of the City of New York ("RCNY") §§ 5-01

et seq. & Appendix A. Ca 517-584.

population in the Coney Island community, and create a need that may exceed PHS-NY's

contractual obligation, it does not analyze the effects of such increases upon access to health care

for this population, but instead merely maintains that the cap on PHS-NY's indigent care

obligations is sufficient to meet the health care needs of all indigent and uninsured persons.’

EAF, Part III, C-21; Ca 562. Furthermore, HHC reaches this conclusion without adequately

considering a number of critical factors, such as the actual number of uninsured residents in the

Coney Island Hospital catchment area, and the predicted growth of the medically indigent

population in this area as a result of the enactment of the Personal Responsibility Act and Work

Opportunity Reconciliation Act.*

Appellants’ contention that the concerns raised prior to the adoption of the HHC Act

The sublease of Coney Island Hospital to PHS-NY has an initial term of 99 years, with a

renewal option for an additional 99 years. In its assessment of Probable Impacts of the Proposed

Action on the delivery of health care, HHC examines the effects of the plan only until the year

2000 -- less than three years from the date of execution of the agreement and 195 years before the

potential end of the PHS-NY's tenure. EAF, Part III, C-16; Ca 556-57.

*For example, HHC projects that the number of uninsured, medically indigent persons in the

Coney Island Hospital catchment area will grow by 37,100 persons by the year 2000. EAF at C-

22. That number, however, is based on population growth data from 1995, Table 7, EAF at C-5,

and thus does not take into account the effects of the Personal Responsibility Act -- enacted in

1996 -- upon Medicaid eligibility. Under the Personal Responsibility Act, immigrants who enter

the country after August 22, 1996 are ineligible for Medicaid for the first five years after entry

unless they meet certain conditions. Moreover, citizens who fail to satisfy the work requirements

of New York's proposed implementing p.ogram may be ineligible for Medicaid for a period of

up to six months. HHC's projection of tae growth in the number of uninsured persons does not

include persons who will be rendered ineligible for Medicaid by the Personal Responsibility Act

or New York State's proposed implementing legislation.

Even without the profound impact of the Personal Responsibility Act, HHC's projection

of the growth in the number of uninsured persons in Coney Island would still be wrong because

it is not based on an actual count of the number of uninsured persons in the catchment area.

Rather, it is based upon the erroneous assumption that the number of uninsured in New York

City can be evenly allocated among specific boroughs and communities based on the proportion

of the total population living within that area. However, people's income and insurance levels

vary markedly by borough and community.

10

regarding private operation of the municipal hospitals are irrelevant because the proposed

sublease provides HHC with certain remedies, see App. Reply at 4-5, fares no better. While

purporting to address Respondents’ arguments regarding the scope and effectiveness of the

sublease remedies, Appellants, in fact, do not confront them at all. First, as Respondents

observed in their opening brief, the terms of the proposed sublease severely restrict the bases

upon which HHC may claim a breach and invoke the specified remedies. In fact, PHS-NY is

granted wide latitude on all of the key issues regarding the provision of health care services.

Thus, under the sublease, PHS-NY: (1) cannot be required to provide indigent care above the

trigger point (cap) after the first year in which it is reached; (2) cannot be required to provide

indigent care services to a specific number of individuals; (3) can close a "core" department

altogether without getting HHC's approval for certain articulated reasons -- i.e. changes in

government reimbursement mechanisms; and (4) can transfer responsibility for performing

inpatient and outpatient "non-core" services to other providers without ensuring that such

providers will accept referred patients without regard for their ability to pay. Proposed Sublease

§ 28.01; Ca 473c.

Second, with regard to the few areas in which HHC retains some measure of oversight

authority, the remedies available to the corporation are quite fnited For example, the proposed

sublease circumscribes the scope of information that H'IC can request, and states that PHS-NY’s

concurrence that the information is “reasonably needed” is a prerequisite to access. Moreover,

even if HHC uncovers a problem, its ability to enforce the contract would be severely

constrained. For example, if HHC determines that there are problems with the quality of care, it

would have no recourse unless the problems are so great that the hospital loses its accreditation.

See Hevesi, Fundamental Issues at 11; Ca 616. Similarly, HHC would have very little influence

11

over PHS-NY’s decision to institute any changes in the services offered at Coney Island

Hospital. Indeed, PHS-NY can close a “core” department without HHC approval, and can

successfully rebut any HHC challenge by showing that the closure is a “reasonable” response to

“changes in health care practices, changes in the need of the Coney Island community,” or

“fundamental changes which materially affect the delivery of health care services.” Proposed

Sublease, § 28.01(b); Ca 473d. With regard to all “non-core” departments, such as cardiology,

urology, pulmonary care, anesthesiology, endocrinology, oral surgery, orthopedic surgery, and

special hematology, PHS-NY can make changes without any effective limitation. Id. at 7-8;

Proposed Sublease § 28.01(a) and (c); Ca 473d.

Third, and most importantly, any attempt by HHC to invoke the remedies provided to it

will trigger an arbitration process during which the patients served by Coney Island Hospital will

be denied the services or treatment discontinued or altered by PHS-NY. While HHC indeed

may “retain the traditional authority of a landlord to enforce the sublease terms,” App. Reply at

5, the disputes that will arise under the proposed sublease will not involve the status of a parcel

of real property, but rather the provision of critical health care services to the City’s most

vulnerable citizens. Appellants have made no attempt to address the problem of the suspension

of these services during the pendency of the parties’ disputes.

Finally, while Appellants’ statement that the Coney Island Hspital transaction involves

the disposition of only one hospital is accurate, see App. Reply at 5, their characterization of the

ramifications of the transaction is not. Appellants conveniently ignore the fact that HHC was

created by the Legislature to be an integrated system of hospitals, operating under the auspices of

a single corporation. See HHC Act § 7832. The Act provides for central administration to be

provided by HHC, and specifically delineates a centralized role for HHC to play in the operation

12

of the municipal hospitals.’

There can be no dispute that HHC now unquestionably functions as a consolidated

network with centralized management and regional networking and planning. The effect of the

removal of one hospital from this network has not been assessed. For example, while it is clear

that HHC will incur the expense of reimbursing PHS-NY for its charity care costs for one year if

those costs rise above the trigger point, see Proposed Sublease § 28.05(c); Ca 473k, there has

been no analysis of how this expense will affect HHC, nor of how HHC will meet either the

service or the financial obligations if the trigger point is exceeded in future years. In this regard,

the EAF states that:

It can be expected that the City and HHC would provide care for any remaining

portion of the indigent and uninsured population and could meet this need through

other resources, including other hospitals, or by creating new health care centers

or funding additional care through PHS-NY at CIH.

EAF at C-22; Ca 563. If PHS-NY turns away patients to avoid exceeding the contractual cap,

HHC will still be required to fund the costs of such care at other municipal facilities. This would

require HHC to divert resources from those institutional facilities, which would in turn affect

their ability to carry out their stated missions of delivering care to all regardless of ability to pay.

Appellants’ attempt to brush aside the fact that the proposed transfer of operational

control over Coney Island Hospital to PHS-NY fundamentally conflicts with HHC’s public

purpose by denoting this problem an “ideological” issue is nonsense. See App. Reply at9. The

principle is well-established that public assets, such as health facilities, are held in trust by the

3 Section 7385 of the HHC Act describes the general powers of the corporation and lists

specific instances where the corporation is to provide centralized administration of the HHC

hospitals. For example, in describing one of its powers, subdivision 7 states [HHC shall have the

power "[t]o operate, manage, superintend, and control any health facility under its jurisdiction . .

"

13

government “for public use,” and that such assets cannot be transferred to any other use without

“special legislative sanction.” See Meriwether v. Garrett, 102 U.S. 472, 513, 26 L. Ed. 197

(1880); Cotrone v. City of New York, 38 Misc. 2d 580, 581, 237 N.Y.S.2d 487, 489 (Sup. Ct.

Kings Co. 1962); accord American Dock Co. v. City of New York, 174 Misc. 183, 21 N.Y.S.2d

943, 957 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co. 1940), aff'd, 261 A.D. 1063, 26 N.Y.S.2d 704, aff'd, 286 N.Y. 658,

36 N.E.2d 696 (1941); see also Lake George Steamboat Co. v. Blais, 30 N.Y.2d 48, 51, 281

N.E.2d 147, 148, 330 N.Y.S.2d 336, 338 (1972) ("It has long been the rule that a municipality,

without specific legislative sanction, may not permit property acquired or held by it for public

use to be wholly or partly diverted to a possession or use exclusively private") (citations

omitted). Appellants fail to address this rule and cite no support whatsoever for their bald claim

of authority to undertake the Coney Island Hospital transaction. Coney Island Hospital

“performs an essential public and governmental function,” HHC Act § 7382, and is clearly

dedicated to public use. Because there is no “clear and certain” legislative authority permitting

the sale or lease of the Hospital, the proposed sublease to PHS-NY is ultra vires. See Lake

George Steamboat Co., 30 N.Y.2d at 52, 281 N.E.2d at 149, 330 N.Y.S.2d at 339 (the legislative

authority authorizing the diversion of public land to a private entity must be "clear and certain");

see also American Dock Co., 174 Misc. at 824, 21 N.Y.S.2d at 957 (legislative authority must be

"special").

II. APPELLANTS’ CLAIMS THAT ULURP DOES NOT APPLY TO THE CONEY

ISLAND HOSPITAL TRANSACTION AND THAT CONSENT OF THE CITY

COUNCIL IS NOT REQUIRED ARE MERITLESS

Appellants’ argument that the Supreme Court’s decision regarding the applicability of

ULURP and the City Council’s role in reviewing the Coney Island Hospital transaction amounts

to a “radical” restructuring of City government simply falls flat. See App. Reply at 10-11. The

14

lower court’s decision logically analyzes the language of the HHC Act and ULURP and reaches

the correct conclusion: the Mayor is authorized to review the business implications of any real

property transaction, and the City Council is granted the authority, formerly vested in the Board

of Estimate, to be the final decisionmaker under ULURP to review the land use implications of

such transactions. New York City Charter § 384(a) & (b)(5); City Charter Revision Commission

Final Report at 19; see also Tribeca Community Assoc. Inc. v. New York State Urban

Development Corp., Index No. 20355/92 (April 13, 1993 Sup. Ct. N.Y"), aff’d, 200 A.D.2d 536,

607 N.Y.S.2d 18 (1% Dept. 1994) (holding that under revised § 384, the Mayor approves the

business terms of a sale or lease of city property, and the land use impacts are subject to

ULURP).

The plain language of § 7385(6) of the HHC Act states that there must be a formal

review of the disposition of any “health facility or other real property acquired or constructed by

, J the corporation...”. Similarly, ULURP clearly applies to "any disposition of the real property of

the City" by "any person."® New York City Charter § 197-c (emphasis supplied). The only

issue — to the extent that one exists at all -- is whether it is the City Council or the Mayor that

Appellants provide no additional support for their bald claim that ULURP does not apply to

decisions regarding the disposition of HHC property. See App. Reply at 13. First, section 197-c

in no way limits land use review to specific property interests; it plainly encompasses subleases,

given that a sublease is clearly one way a "person" could dispose of City property. Second, there

is nothing in the HHC Act that exempts the City properties operated by HHC from the

requirements of ULURP. Appellants’ reliance on Waybro Corp. v. New York City Board of

Estimate, 67 N.Y.2d 349, 493 N.E.2d 931, 502 N.Y.S.2d 707 (1986), as support for this theory is

therefore entirely misplaced. As Respondents observed in their opening brief, Waybro involved

the interpretation of the New York State Urban Development Corporation ("UDC") Act which

preempted local land use regulations. The UDC Act expressly grants UDC the authority to

override the local charter; there is no such provision in the HHC Act. As the court below

appropriately noted, "[t]he HHC Act, by requiring consent of the Board of Estimate under §

7385(6) for dispositions of property, expresses, if anything the contrary intent." Opinion at 15;

Ca 855.

15

succeeds to the Board of Estimate’s role in undertaking the required land use review. This

matter is easily resolved by a review of the applicable provisions of the City Charter.

Section 1152(e) of the Charter provides that upon dissolution of the Board of Estimate,

the powers it exercised "set forth in any state or local law that are not otherwise devolved by the

terms of such law[,]" are to "devolve upon the body, agency or officer of the city charged with

comparable and related powers and responsibilities under" the Charter. New York City Charter,

§ 1152(e) (emphasis supplied). The revised Charter divides the Board of Estimate's powers

concerning the disposition of City property between the Mayor and City Council. As to the

Mayor’s powers, section 384 provides:

Disposal of property of the city. a. No real property of the city may be sold, leased,

exchanged or otherwise disposed of except with the approval of the mayor. . ..

As to the City Council, section 384 provides:

b.(5) Any application for the sale, lease (other than lease of office space), exchange or

other disposition of real property of the city shall be subject to review and approval

pursuant to sections one hundred ninety-seven ¢ [ULURP] and one hundred ninety-seven-

d. Such review shall be limited to the land use impact and implications of the proposed

transaction.

New York City Charter § 384. Because the approval process required under ULURP

unequivocally places land use review authority under the auspices of the City Council, see City

Charter § 197-d,” the powers of review over dispositions of the City’s real property are clearly

"Section 197-d of the City Charter provides in pertinent part:

Council Review. a. The city planning commission shall file with the council and with the

affected borough president a copy of its decisions to approve or approve with

modifications (1) all matters described in subdivision a of section one hundred ninety-

seven-c, (2) plans pursuant to section one hundred ninety-seven-a, and (3) changes in the

text of the zoning resolution pursuant to sections two hundred and two hundred one.

e. All actions of the council pursuant to this section shall be filed with the mayor prior to

the expiration of the time period for council action . . . [and] . . . shall be final unless the

16

a : : Ey

divided between the Mayor and the City Council. See Final Report of the City Charter Revision

Commission, at 20; Appendix A at 6 ("The basic change made by the 1989 charter amendments

was to substitute the Council for the Board as the final decisionmaker in land use"). The 1989

Charter Amendments provide the City Council with the power to consider land use effects, and

thus the Council clearly has powers “comparable” to the role given the Board of Estimate in the

HHC Act. Accordingly, under § 1152 of the City Charter, the City Council must approve the

Coney Island Hospital transaction.

CONCLUSION

The proposed sublease of Coney Island Hospital to PHS-NY, a private, for-profit

corporation, disavows the City’s constitutional mandate to provide quality and dignified care to

indigent and uninsured New Yorkers, contravenes the New York City Health and Hospitals

Corporation Act, and undermines HHC’s corporate purpose and public mission. For these

reasons, Respondents respectfully request that the Court uphold the judgment of the Appellate

Division, Second Department in so far as it affirmed that portion of the decision of the Queens

County Supreme Court holding that the HHC Act precludes the dismantling of the HHC system

generally, and the long-term sublease of Coney Island Hospital to PHS-NY, specifically; and

reverse that portion of the judgment deleting the Supreme Court’s decision holding that any lease

of an HHC facility must be approved pursuant to ULURP, and that any such lease must be

mayor within five days of receiving a filing . . . files with the council a written

disapproval of the action. Any mayoral disapproval under this subdivision shall be

subject to override by a two-thirds vote of all of the council members within ten days of

such filing by the mayor.

17

approved by the City Council as well as the Mayor.

Dated: New York, New York

January 3, 1998

Respectfully submitted,

CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS

By: 4 [nen 7. { ! 2 bing le ]

Barbara J. Olshansky’ gil

i.

Robert T. Perry

666 Broadway, 7th Floor

New York, New York 10012

(212) 614-6439

18