Fields v. City of Fairfield Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

September 24, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Fields v. City of Fairfield Brief for Appellants, 1963. edf443a2-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f465be8d-019b-46d7-b94b-ea78591d8927/fields-v-city-of-fairfield-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

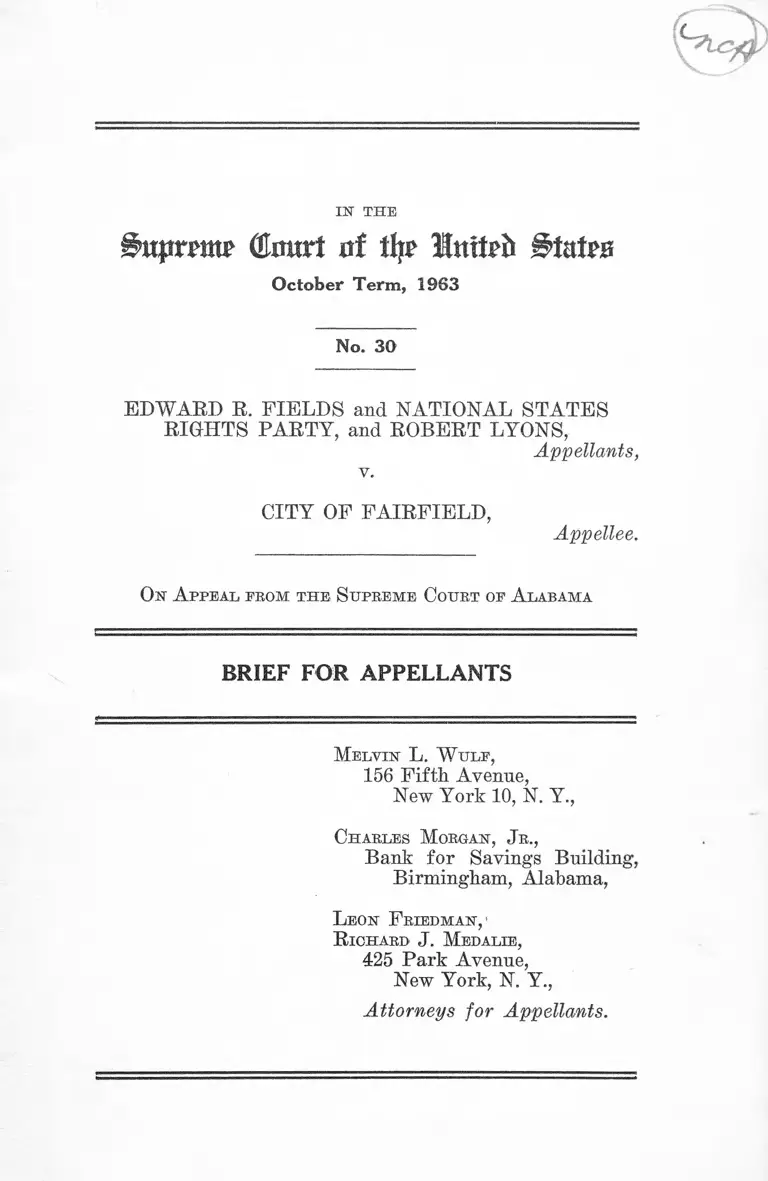

IN THE

©Hurt at % Hmteb States

October Term, 19S3

No. 30

EDWARD E. FIELDS and NATIONAL STATES

EIGHTS PARTY, and EOBEET LYONS,

Appellants,

v.

CITY OF FxlIEFIELD,

Appellee.

O n A ppeal prom th e S uprem e C ourt op A l abama

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

M elvin L . W u l p ,

156 Fifth Avenue,

New York 10, N. Y.,

Charles M organ, J r .,

Bank for Savings Building,

Birmingham, Alabama,

L eon F riedman /

R ichard J . M edalie,

425 Park Avenue,

New York, N. Y.,

Attorneys for Appellants.

I N D E X

Opinions Below ............................................. 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................... 1

Constitutional Provisions Involved ............................ 2

The Statutes In volved ................................................... 2

Questions Presented....................................................... 3

Statement of the C a se ............................................ 4

Summary of Argument ................................................. 6

A rgument :

I. The sections of the Code of Fairfield involved

herein are unconstitutional and void on their

face ...................................................................... 9

A. Sections 3-4 and 3-5 of the City Code . . . 9

B. Section 14-53 of the City Code ................. 12

II. The ordinances and the injunction issued

pursuant to them are unconstitutional as

app lied ................................................................ 16

A. Sections 3-4 and 3-5 of the City Code . . . . 16

B. Section 14-53 of the City C o d e ................. 18

III. Appellants were not foreclosed from testing

the injunction’s constitutionality by violating

its terms ............................................................. 21

A. The Mine Workers doctrine does not

apply to First Amendment cases............... 22

B. The primacy of First Amendment rights

requires this Court to hold that the in

junction’s constitutionality may be tested

by violating its terms ....... ..................... 27

PAGE

IV. The convictions violated the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because

there was no evidence tending to prove the

offenses charged ..................................... 36

A. There was no evidence tending to prove

that petitioners violated the injunction as

it related to Sections 3-4 and 3-5 of the

Fairfield City C o d e ..................... 37

B. There was no evidence tending to prove

that petitioners had violated the injunc

tion as it related to Section 14-53 of the

Fairfield City Code .................................... 38

Conclusion ..................................................................... 40

Table of Cases Cited

Ayers, Ex Parte, 123 U. S. 443 (1887) ....................... 25n

Bantam Books v. Sullivan, 9 L. Ed. 2d 584 (1963) . . 13

Building Service Employees v. Gazzam, 339 U. S.

532 (1950) ..................' ............................................... 23n

u Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 (1940) . . 7,13,15, 21

Carpenters and Joiners Union v. Ritter’s Cafe, 315

U. S. 722 (1952) ......................................... ............ 23n

Congress of Racial Equality v. Douglas, 318 F. 2d

95 (C. A. 5, 1963) ..........‘ .........................................27, 36n

Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 U. S. 569 (1941) ............ 15

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 (1937).................. 7,19, 20

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315 (1951) . . 9, 29n, 34, 35

Fisk, Ex Parte, 113 U. S. 713 (1885) ....................... 25n

v"' Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 (1961 ).................. 9, 36

Giboney v. Empire Storage & Ice Co., 336 U. S. 490

(1949) .......................................................................... 23n

- Green, In the Matter of, 369 U. S. 689 (1962 )..........8, 24, 25

PAGE

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U. S. 498 (1939) ........................ 15

Henry, Ex Parte, 147 Tex. 315, 215 S. W. 2d 588

(Tex. Sup. Ct. 1948) ............................................... 33n

Hughes v. Superior Court, 339 U. S. 460 (1960) . .. 23n

Jameson v. Texas, 318 U. S. 412 (1943) ..................... 6,10

Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495 (1952)

7,13,16,17

Kasper v. Brittain, 245 F. 2d 92 (C. A. 6 195 7 )........ 9, 35n

Kingsley Books, Inc. v. Brown, 354 U. S. 436

(1957) ......................................... .......................... 18,19, 32n

Kovacs v. Cooper, 336 IT. S. 77 (1949) ...................... 15

Kunz v. New York, 340 U. S. 290 (1951)........7,12,13,17,19

Local Union 10 v. Graham, 345 IT. S. 192 (1953) .. 23n

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444 (1938)..............6, 7,11,13,15

Masses Pub. Co. v. Patten, 244 Fed. 535 (S. D. N. Y.

1917) rev. 246 Fed. 24 (2d Cir. 1917) .................. 35

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 (1958) .............. 25

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697 (1931) ..........7,13,16,17

Niemotka v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268 (1961). . .7 ,12n, 13,15

Poulos v. New Hampshire, 345 U. S. 395 (1953) . . . . 33n

Rockwell, Matter of v. Morris, 12 A. D. 2d 272 (1st

Dept. 1961) a ff’d 2115 N. Y. S. 2d 502 (1961)

cert. den. 368 U. S. 913 (1961) ................................. 9, 34

Rowland, Ex Parte, 104 U. S. 604 (1882) .................. 25n

Saia v. New York, 334 U. S. 558 (1948) ...................... 7,13

Sawyer, In Re, 124 U. S. 200 (1888) ....................... 25n

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147 (1939 )..................6,10,13

State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U. S. 624

(1943) .......................................................................... 22

State ex rel. Liversey v. Judge of Civil District

Court, 34 La. Ann. 741 (La. Sup. Ct. 1882) . . . . 33n

State of Alabama v. Arthur D. Gray, et al., Circuit

Court of Talladega County, in Equity, No. 9760 . . 3Qn

IV

State v. Morrow, 57 Ohio App. 30, 11 N. E. 2d 273

(Ohio Ct. of App. 1937) ........................................ 33n

Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313 (1958). .7 ,12n,13,15, 29, 32, 33

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 (1931) .......... 11

Talley v. California, 362 U. S. 60 (1960) .................. 6,10

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 ............................ 11,12

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 (1945 )........7,16,19, 20, 32

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 (1960) .......... 9, 36

Times Film Corp. v. Chicago, 365 U. S. 43 (1961) . . . 13

Tucker, Ex Parte, 110 Tex. 335, 220 S. U. 75 (Tex.

Sup. Ct. 1920) ....................................... 33n

United Gas, Coke & Chemical Workers v. Wisconsin,

Employment Relations Board, 340 U. S. 383

(1941) ......................................................................... 8,24,25

United Mine Workers v. United States, 330 U. S. 258

(1947) .........................................7, 8, 21, 22, 23, 23n, 24, 25,

25n, 26, 27, 27n, 28, 31, 32

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357 (1927) .......... 29n

PAGE

Other Authorities Cited

Chafee, Free Speech in the United States (Harvard

University Press, 1946), 326, 342 ........................... 31n

Chafee, Some Problems of Equity (Univ. of Mich.

Law School, 1950) Chapters V III and IX .......... 28n

Cox, The Void Order and the Duty to Obey, 16 Univ.

of Chicago Law Rev. 86 (1948) ............................. 28n

Emerson, The Doctrine of Prior Restraint, 201 L. and

Contemp. Prob. 648 (1955) .............................. 7,13,14,15

General City Code of Fairfield, Alabama:

Section 3-4 ..................................................2,3,6,9,16,18

Section 3-5 ..................................... 2, 3, 6, 9,10,16,18, 37

Section 14-53 ...............................3, 6, 7,12,15,18, 21, 38

V

New York Times:

October 30, 1962 .....................................................

November 10, 1962 .................................................

November 30, 1962 .................................................

April 23, 1963 .........................................................

May 31, 1963 ...........................................................

June 7, 1963 .............................................................

The Norris-LaGuardia Act, 47 Stat. 70, e. 90, 29

U. 8. C. § 101 .................................................. .

The Supreme Court and Civil Liberties, 4 Vanderbilt

Law Rev. 533 (1951) .................................................

United States Constitution:

Amendment 1 ................................... 2, 3, 8, 20, 21, 27, 28,

29, 30n, 32, 33, 33n

Amendment 14 ......................................... 2, 3,19, 33n, 36

Watt, The Devine Right of Government, by Judi

ciary, 14 Univ. of Chicago Law Rev. 409 (1947) .. 28n

28 U. S. C. § 1257(2) ..................................................... 2

PAGE

30n

30n

30n

30n

31n

3 In

22n

28n

IN T H E

g>ujxrottp (tort uf tip TUnxUb States

October Term, 1963

No. 30

E dward E. F ields and N ational S tates E ights P arty

and E obert L yons,

Appellants,

against

C ity of F airfield ,

Appellee.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama affirming

appellants’ convictions is reported at—Ala.— , 143 So. 2d

177 and is contained in the Eecord at pp. 86-90. No opinion

was written by the Circuit Court of Jefferson County, but

its oral opinion rendered at the time of conviction is con

tained in the Eecord at pp. 71-73.

Jurisdiction

Appellants Fields and Lyons were adjudged guilty of

criminal contempt on October 12, 1961. The judgment was

affirmed and entered by the Alabama Supreme Court on

June 14, 1962 (E. 91) and a timely application for rehearing

denied on July 12, 1962 (E. 93). Notice of Appeal to the

Supreme Court of the United States was filed with the Su

preme Court of Alabama on September 10, 1962 (E. 95-97),

2

and an amendment to the Notice was tiled September 18,

1962 (R. 98-99). Execution of sentence was stayed by the

Alabama Supreme Court until final disposition by this

Court (R. 93-94). Probable jurisdiction was noted on March

18, 1963 (R. 99).

Jurisdiction of this Court rests on 28 U. S. C. § 1257(2).

Constitutional Provisions Involved

U nited S tates C onstitution

Amendment 1:

“ Congress shall make no law * '* * abridging the

freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the

people peaceably to assemble and to petition the Gov

ernment for a redress of grievances.”

Amendment 14, Section 1:

“ * * * No State shall * * * deprive any person of

life, liberty or property, without due process of law.”

The Statutes Involved

General C ity C ode op F airfield , A labama

Sec. 3-4. Handbills, etc.—Distribution on streets.

It shall be unlawful for any person to distribute or cause

to be distributed on any of the streets, avenues, alleys,

parks or any vacant property within the city any paper

handbills, circulars, dodgers or other advertising matter.

[Ord. No. 354, §4 (1957).]

Sec. 3-5. Same—Placing or throwing in automobiles.

It shall be unlawful for any person to distribute in the

city any handbill or other similar form of advertising by

throwing or placing the same in any automobile or other

vehicle within the city. [O'rd. No. 354, §5 (1957).]

3

Sec. 14-53. Public meetings; permit required.

It shall be unlawful for any person or persons to hold

a public meeting in the city or its police jurisdiction with

out first having obtained a permit from, the mayor, to do so.

[Ord, No. 184, §4, 11-9-32.]

Questions Presented

1. Whether Sections 3-4 and 3-5 of the General City

Code of Fairfield, Alabama, upon which appellants’ con

tempt convictions rest, on their face or as construed and

applied in this case, abridge appellants’ rights of free

speech, press and assembly in violation of the due jjrocess

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and the First Amend

ment to the United States Constitution.

2. Whether Section 14-53 of the General City Code of

Fairfield, Alabama, upon which appellants’ contempt con

victions rest, on its face or as construed and applied in this

case, abridges appellants’ rights of free speech, press and

assembly in violation of the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment and the First Amendment to the United

States Constitution.

3. Whether consideration by the Supreme Court of the

United States of a challenge on federal grounds to the

validity of a municipal ordinance on its face, or as con

strued and applied, may be precluded where appellants

are found in contempt of an ex parte temporary injunction

which purports to enforce compliance with the ordinance,

and the state court refuses to entertain the merits of the

challenge on the procedural ground that appellants “ chose

to disregard the temporary injunction rather than contest

ing it by orderly and proper procedure,” where the conse

quence of the state procedural rule is to nullify appellants’

rights of free speech, press and assembly in violation of

the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and

the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

4

4. Whether appellants’ convictions for contempt, being

unsupported by any evidence of guilt, constitute wholly

arbitrary official action and thereby violate the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution.

Statement of the Case

Appellant Fields is Information Director of the Na

tional States Eights Party. Appellant Lyons is Youth Or

ganizer of the Party (R, 58). The Party, which stands

for white supremacy and segregation (R. 53), has been on

the ballot in Alabama (R. 60).

Sometime prior to Wednesday, October 11, 1961 (R. 44),

the Party had handbills distributed in Fairfield which con

tained the following announcement (R. 42):

W h ite W orkers

M eeting

* N iggers A re T akin g O ver U n io n s !

*N iggers W an t Ou r P arks A nd P oods!

•Niggers D em and M ixed S chools !

Communists in NAACP and in Washington say

Whites Have No RIGHTS !

The Nigger gets everything he DEMANDS!

White Supremacy Can be saved

WHITES CAN STOP this second Reconstruction!

Hear Important Speakers From 4 States

Time—8 P. M. Date—Wed. Oct. 11

Place—5329 Valley Road

In Downtown Fairfield, Alabama

A bove th e Car W ash

T hunderbolt Mobile Unit Will be Parked Out

Front Sponsored by National States Rights Party

Box 786, Birmingham, Alabama

P ublic I nvited

Come and Bring Your Friends

5

At about 5:00 P. M., Tuesday, October 10, 1961, tbe

day before the scheduled meeting, the Mayor of Fairfield

sent a notice to appellant Fields that he had violated a

city ordinance which prohibited the distribution of hand

bills. The Mayor also informed Fields that another ordi

nance forbade public meetings without a permit (E. 43).

At about 6:00 P. M. the same evening, Fields phoned

the Mayor at his home to discuss the issuance of a permit

for the meeting (R. 36-38). Fields called the Mayor’s

office the morning of the following day and made an ap

pointment for 2:00 P. M. that afternoon for further dis

cussion (R. 55). Around noon of that day, however, Fields

was served with an injunction (R. 25) forbidding him, the

National States Rights Party, their servants, agents and

employees, from holding the scheduled meeting and from

distributing any handbills announcing the meeting. Fields

did not keep his 2 :00 P. M. appointment.

The injunction (R. 5-6) was issued on the ex parte

application of the City of Fairfield. The Bill of Complaint

(R. 1-4) alleged, among other things, that the appellants

were “ distributing’ handbills of an inflammatory nature

designed to create ill will and disturbances between the races

in the City of Fairfield,” that the purpose of the announced

meeting “ is to create ill will, disturbances, and disorderly

conduct between the races,” and that the meeting “ will

constitute a public nuisance, injurious to the health, com

fort, or welfare of the City of Fairfield and * * # is calcu

lated to create a disturbance, incite to riot, disturb the

peace, and disrupt peace and good order in the City of

Fairfield. ’ ’

About 7 :30 P. M. on the evening of the scheduled meet

ing, appellants Fields and Lyons arrived at the meeting

place to announce that the meeting site had been trans

ferred to the city park at Lipscomb, a nearby town (R. 18,

6

26, 28, 49, 54, 60, 62, 63).1 Subsequent to the service of

the injunction, no meeting was held in Fairfield (R. 20,

48, 56), no handbills were distributed (R. 20, 24, 28, 44,

47, 54, 64, 72),2 nor was there any disturbance whatsoever

(R, 14, 26-30, 54).

Appellants were arrested for violating the injunction.

On the following day, October 12, 1961, after a hearing,

each was found in contempt and sentenced to serve 5 days

in jail and pay a $50 fine.

The Alabama Supreme Court affirmed the convictions

on the ground that the question of a statute’s constitu

tionality may not be raised “ in collateral proceedings on

appeal from a judgment of conviction for contempt of

the order or decree * *

Summary of Argument

I.

A. Sections 3-4 and 3-5 of the Code of Fairfield, which

impose an absolute ban upon the distribution of handbills

and circulars, are unconstitutional on their face. Lovell v.

Griffin, 303 U. S. 444 (1938); Schneider v. Stale, 308 IT. S.

147 (1939); Jamison v. Texas, 318 U. S. 412 (1943);

Talley v. California, 362 U. S. 60 (1960).

B. Section 14-53 of the City Code, which makes it un

lawful for anyone to hold a public meeting in Fairfield

“ without first having obtained a permit from the Mayor to

do so,” is likewise unconstitutional on its face. Lovell v.

1 Earlier the same day, appellant Lyons and another person were

prohibited by the police from entering the meeting place (R . 34, 50).

2 Some copies of the Party’s newspaper, Thunderbolt, were dis

tributed near the original meeting place, but it contained no notice

of the Fairfield meeting, nor had its distribution been enjoined.

A copy of the newspaper is contained at R. 21.

7

Griffin, supra; Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 (1940);

Saiav. New York, 334 U. S'. 558 (1948); NiemotJco v. Mary

land, 340 U. S. 268 U. S. (1961) ;Kunz v. New York, 340 U. S.

290 (1951); Stauib v, Baxley, 355 U. S. 313 (1958). Section

14-53, on its face, is a prior restraint, “ a form of infringe

ment upon freedom of expression to be sepecially con

demned.” Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 II. SI 495, 504. Emerson,

The Doctrine of Prior Restraint, 20 L. and Contemp. Prob.

648 (1955). The ordinance does not embody “ narrowly

drawn, resonable and definite standards for the officials to

follow” and has no “ definite standards or other controlling

guides governing the action of the Mayor # * * in granting

or withholding a permit.” Niemotko v. Marylond, supra;

Stauh v. Baxley; supra.

II.

A. The injunction and ordinances, as applied against the

distribution of appellants’ handbills, violated the rule of

law established in Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697 (1931).

In addition, the appellants were convicted not for violating

the explicit terms of the injunction but rather for distribut

ing copies of their newspaper which had not been expressly

enjoined.

B. The injunction and ordinances, as applied against the

appellants ’ meeting, even if valid as to a meeting to be held

in the street or a public park, are clearly invalid when ap

plied against a meeting to be held in a private hall. DeJonge

v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 (1937); Kunz v. New York, supra;

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 (1945).

III.

A. The decision of the Alabama Supreme Court that, on

the authority of United Mine Workers v. United States,

330 U. S. 258 (1947), the appellants were foreclosed from

challenging the constitutionality of the injunction against

8

them “ in collateral proceedings on appeal from a judgment

of conviction for contempt of the * * * decree,” is in error.

The Mine Workers doctrine does not apply where First

Amendment rights are concerned. That case revolved

around the question of conduct subject to statutory regula

tion rather than conduct fully protected by the Constitu

tion. Second, it involved the complex problems of statutory

interpretation in a factual setting that had not previously

received judicial consideration. Third, it was concerned

with the problem that arose in the context of an industrial

dispute. In addition, United Gas, Coke & Chemical Work

ers v. Wisconsin Employment Relations Board, 340 U. S.

383 (1941), and In the Matter of Green, 369 U, S. 689 (1962),

further support the view that appellants may not be fore

closed from testing the underlying validity of the injunction

simply because they have asserted the right in the course

of contempt proceedings.

Even in Mine Workers own terms, the injunction in this

case was clearly frivolous and could be violated with im

punity. All of the Justices in the Mine Workers case,

except two, expressed the belief that there were circum

stances where an order of the court was so frivolous that

its violation could not be punished. The facts of this case

come within that explicit exception.

B. As an original proposition, the primacy of First

Amendment rights requires this Court to hold that the in

junction’s constitutionality may be tested by violating its

terms. Failure to so hold will inevitably result in the sup

pression of First Amendment rights in a wide variety of

circumstances heretofore fully protected. This rule must

be adopted both in cases where the injunction and the

ordinances on which they are based are clearly invalid, such

as here, and in cases where their validity are open to ques

tion. No other rule will allow that “ free and open en

counter” which must be permitted immediately when con

cern for an issue of public importance is high.

9

That the municipal authorities thought that violence

might erupt were appellants ’ meeting allowed to take

place, does not change the situation. No one can be sure

that a scheduled speech will go forward in the manner con

templated or that it will have the effect predicted. When a

speaker “ passes the bounds of argument or persuasion and

undertakes incitement to riot” it is clear that the police can

“ prevent a breach of the peace.” Feiner v. New York, 340

IT. S. 315 (1951); Rockwell v. Morris, 12 A. D. 2d 272, af

firmed 215 N. Y. S. 2d 502, cert, denied 368 U. 8. 913. Com

pare Kasper v. Brittain, 245 F. 2d 92 (C. A. 6, 1957).

IV.

The convictions violated the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment because there was no evidence tend

ing to prove the offense as charged. Thompson v. Lomsville,

362 IT. 8. 199 (1960); Garner v. Louisiana, 368 IT. S. 157

(1961). There is not a shred of evidence in the record to

show that any of the handbills against which the injunction

was directed were distributed. Likewise, there is no evi

dence that the appellants violated the order enjoining them

from holding a public meeting in the City of Fairfield. The

record clearly shows that “ there was no meeting held.”

ARGU M ENT

i

The sections of the Code of Fairfield involved

herein are unconstitutional and void on their face.

A. Sections 3-4 and 3-5 of the City Code.

Section 3-4 of the Code of Fairfield declares it “ unlaw

ful for any person to distribute or cause to be distributed

on any of the streets, avenues, alleys, parks or any vacant

property within the city any paper handbills, circulars,

dodgers or other advertising matter” . Section 3-5 simi

larly bans distribution of handbills by placing them in

10

automobiles. These statutes are almost identical to the

statutes passed by the cities of Los Angeles, California,

Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Worcester, Massachusetts, and

held unconstitutional in Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147

(1939). Each of the statutes there involved also placed an

absolute prohibition upon the distribution of handbills on

streets, sidewalks or parks of each of the respective muni

cipalities. The Los Angeles Muncipal Code eaxmined in

Schneider also forbade the placing of handbills in auto

mobiles or vehicles just as § 3-5.

The Court through Justice Roberts declared that the

statutes were unenforceable against the petitioners, each of

whom had distributed leaflets on the public streets of the

municipalities involved. The Court dismissed the respond

ents’ argument that the statutes were a valid exercise of

police power to prevent littering of the streets:

“ We are of opinion that the purpose to keep the

streets clean and of good appearance is insufficient

to justify an ordinance which prohibits a person

rightfully on a public street from handing literature

to one willing to receive it. Any burden imposed

upon the city authorities in cleaning and caring for

the streets as an indirect consequence of such dis

tribution results from the constitutional protection

of the freedom of speech and press. This constitu

tional protection does not deprive a city of all power

to prevent street littering. There are obvious meth

ods of preventing littering. Amongst them is the

punishment of those who actually throw papers on

the streets.” 308 U. S. at 162.

Similarly, in Jamison v. Texas, 318 U. S. 412 (1943),

an absolute prohibition against the distribution of hand

bills was held unconstitutional as applied to a member of

Jehovah’s Witnesses who distributed handbills announcing

a meeting of her group to hear an address by one of its

leaders; and in Talley v. California, 362 U. S. 60, 65 (1960),

a municipal ordinance which forbade the distribution of

11

handbills which did not bear the names of the persons who

prepared, distributed or sponsored them was also held

unconstitutional and “ void on its face.”

A statute is void on its face if it is so comprehensive

that it forbids or punishes the normal and ordinary dissemi

nation of information or is “ not limited to ways which

might be regarded as inconsistent with the maintenance of

public order, or as involving disorderly conduct, the moles

tation of the inhabitants, or the misuse or littering of the

streets.” Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444, 451 (1938).

There is ample justification for declaring unconstitu

tional under all circumstances sweeping prohibitions

against free speech and any punishment for violating these

prohibitions. In one of its earlier free-speech cases, this

Court said:

“ The maintenance of the opportunity for free

political discussion to the end that government may

be responsive to the will of the people and that

changes may be obtained by lawful means, an oppor

tunity essential to the security of the Republic, is

a fundamental principle of our constitutional system.

A statute which on its face, and as authoritatively

construed, is so vague and indefinite to permit the

punishment of the fair use of this opportunity is re

pugnant to the guaranty of liberty contained in the

Fourteenth Amendment.” Stromberg v. California,

283 TJ. S. 359, 369 (1931).

Similarly, this Court stated in Terminiello v. Chicago, 337

U. S. 1, 4-5 (1949):

“ A function of free speech under our system

of government is to invite dispute. It may indeed

best serve its high purpose when it induces a condi

tion of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions

as they are, or even stirs people to anger. Speech

is often provocative and challenging. It may strike

at prejudices and preconceptions and have profound

unsettling effects as it presses for acceptance as

an idea. That is why freedom of speech * * * is * * *

12

protected against censorship or punishment, unless

shown likely to produce a clear and present danger

of a serious substantive evil that rises far above

public inconvenience, annoyance or unrest. * * *

There is no room under our constitution for a more

restrictive view. For the alternative would lead to

standardization of ideas either by legislature, courts

or dominant political or community groups.”

The limited areas in which restrictions on free speech

are constitutionally permitted are more adequately covered

by specific statutes dealing with specific evils which can

be constitutionally restricted. ‘ ‘ There are appropriate pub

lic remedies to protect the peace and order of the commu

nity if appellant’s speeches should result in disorder or

violence.” Kwnz v. New York, 340 U. S. 290 (1951). Thus

it follows that any comprehensive statute absolutely for

bidding the dissemination of information must fall even

without an inquiry as to its application in a particular case.

I f construed to cover only obscene literature and disorderly

conduct, it is unnecessary.3 If construed to cover more

than these areas, it is invalid because of its repressive effect

on constitutionally protected activity.

B. Section 14-53 of the City Code.

Section 14-53 of the General City Code of Fairfield

makes it “ unlawful” for anyone “ to hold a public meet

ing” in Fairfield “ without first having obtained a permit

from the mayor to do so.” A cursory examination of the

ordinance shows quite clearly that it also “ is invalid on its

3 It is clear that it is the function of the state courts to construe

such statutes as being so limited. Unless the state court has restricted

the application of the statute to these situations, this Court will

assume that it is to be applied as written ( i . e to cover all dissemina

tion of information). See Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268

(1951); Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313 (1958). No restrictive

limitations have been read into the Fairfield code by the Alabama

courts. To the contrary, the Alabama Supreme Court, in this case,

found them constitutional as written (R . 88).

13

face” (.Stcmb v. Baxley„ 355 IT. S. 313, 321 (1958)) since it

“ makes the peaceful enjoyment of freedoms which the Con

stitution guarantees contingent upon the uncontrolled will

of an official * * * by requiring a permit or license, which

may be granted or withheld in the discretion of such offi

cial” (id. at 322). It therefore imposes “ an unconstitu

tional censorship or prior restraint upon the enjoyment

of those freedoms.” Ibid.; accord, e.g. Cantwell v. Com-,

necticut, 310 U. S. 296, 305 (1940); Kims v. New York, 340

U. S. 290, 293 (1951); Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444, 451

(1938) ; Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268, 273 (1951) ;

Saia v. New York, 334 U. S. 558, 559-60 (1948).

This Court has consistently considered a system of prior

restraint as a more serious violation of the First Amend

ment than a system of subsequent punishment. As the

Court stated in Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U. S.

495, 504 (1952): “ This Court recognized many years ago

that such a previous restraint is a form of infringement

upon freedom of expression to be especially condemned.

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697 (1931).” See also Kun-z

v. New York, 340 U. S. 290, 294-95 (1951). And as it further

stated in Bantam Books v. Sullivan, 9 L. Ed. 2d 584, 593

(1963): “ Any system of prior restraints of' expression

comes to this Court bearing a heavy presumption against

its constitutional validity.” Accord, e.g., Schneider v.

State, 308 U. S. 147, 164 (1939).

The reasons why prior restraints have received special

constitutional condemnation have been eloquently discussed

by members of this Court on previous occasions and need

not be elaborated upon in any great detail. See, e.g., Times

Film, Corp. v. Chicago, 365 U. S. 43, 50 (1961) (dissenting

opinion). Suffice it merely to quote a few select passages

from the landmark article on the subject—Emerson, The

Doctrine of Prior Restraint, 20 L. & Contemp. Prob. 648

(1955) :

“ [1] A system of prior restraint * * * subjects

to government scrutiny and approval all expression

14

in the area controlled—the innocent and borderline

as well as the offensive, the routine as well as the

unusual [p. 656].”

“ [2] Under a system of prior restraint, the

communication, if banned, never reaches the market

place [of ideas] at all [p. 657].”

“ [3] A system of prior restraint is so con

structed as to make it easier, and hence more likely,

that in any particular case the government will rule

adversely to free expression [ibid.].”

“ [4] Under a system of prior restraint, the issue

of whether a communication is to be suppressed or

not is determined by an administrative rather than

a criminal procedure [ibid.].”

“ [5] A system of prior restraint usually operates

behind a screen of informality and partial conceal

ment that seriously curtails opportunity for public

appraisal and increases the chances of discrimina

tion and other abuse [p. 658].”

“ [6] Perhaps the most significant feature of

systems of prior restraint is that they contain with

in themselves forces which drive irresistibly toward

unintelligent, overzealous, and usually absurd ad

ministration [ibid.].”

“ [7] [A] system of prior restraint * * * means,

under most circumstances, less rather than more

communication of ideas; it leaves out of account those

bolder individuals who may wish to express their

opinions and are willing to take some risk; and it

implies a philosophy of willingness to conform to

official opinion and a sluggishness or timidity in

asserting rights that bodes ill for a spirited and

healthy expression of unorthodox and unaccepted

opinion [p. 659].”

“ [8] A system of prior restraint is, in general,

more readily and effectively enforced than a system

of subsequent punishment. * * * A penal proceeding

to enforce a prior restraint normally involves only

a limited and relatively simple issue—whether or

15

not the communication was made without prior ap

proval [ibid.].”

This Court has recognized, however, that a general and

nondiscriminatory piece of legislation which merely regu

lates ‘ ‘ the times, the places, and the manner of soliciting

upon streets, and of holding meetings thereon” (Cantwell

v. Connecticut, supra at 304) will be upheld as a valid

regulatory statute (see, e.g., Cox v. New Hampshire, 312

U. 8. 569 (1941); Kovacs v. Cooper, 336 U. 8. 77 (1949)).

The general theory behind the upholding of this type of

statute is that streets, parks and other public places may

be reasonably regulated for the general interest, comfort

and convenience of all the citizenry or in consonance with

the peace, good order and public safety of the community.

See, e.g., Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U. S. 496, 515 (1939); Lovell

v. Griffin, supra at 451.

If, however, a statute does not embody “ narrowly drawm,

reasonable and definite standards for the officials to fol

low” (Niemotko v. Maryland, supra at 271), if a statute

has no “ definitive standards or other controlling guides

governing the action of the Mayor and Council in granting

or withholding a permit” (Staub v. Baxley, supra at 322),

it does not come within the exception to the general rule

and must be struck down as an unconstitutional prior re

straint. Since Section 14-53 of the Fairfield Code prohibits

the holding of public meetings “ of any kind at any time,

at any place, and in any manner without a permit from

the * * * [mayor]” (Lovell v. Griffin, supra at 451), it

cannot be saved from unconstitutional invalidity. More

over, since “ the ordinance is void on its face, it was not

necessary for appellant to seek a permit under it.” Lovell

v. Griffin, supra at 452-53.

16

I 1

The ordinances and the injunction issued pursuant

to them are unconstitutional as applied.

What is particularly aggravating about the present

case is that, not only were the defendants absolutely pro

hibited by Section 3-4 and 3-5 of the Fairfield Code from

distributing their handbills announcing the meeting and

prohibited by Section 14-53 from holding the meeting with

out permission from the mayor, but they were also en

joined in advance by the issuance of a temporary injunc

tion “ from holding a public meeting # * # as announced, and

from distributing further * * # handbills announcing such

meeting such as were [previously] distributed * * * ”

(R. 6).

We have already noted (supra, Part IB) that, with

j certain limited exceptions, administrative prior restraints

| are unconstitutional, being considered “ as a form of in

fringement upon freedom of expression to be especially

; condemned” (Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, supra at

504). Judicial prior restraints are to be sanctioned no

more than administrative ones. See, e.g., Near v. Minne

sota, supra; Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 (1945).

A. Sections 3-4 and 3-5 of the City Code.

The injunction against the distribution of the handbills

was a particularly noxious constitutional violation in view

of the rule of law established in Near v. Minnesota, supra.

In that case, the state court enjoined the defendants from

issuing “ any publication whatsoever which is a malicious,

scandalous or defamatory newspaper, as defined by law”

(283 U. S. at 706). The Supreme Court held the statute

and injunction to be a prior restraint abridging the free-

j dom of the press. Chief Justice Hughes, speaking for the

majority, stated that “ the statute in question does not

' deal with punishments; it provides for no punishment, ex

17

cept in cases of contempt for violation of the court’s order,

but for suppression and injunction, that is, for restraint

of publication” (id. at 715). The Chief Justice went on to

enunciate the doctrine of prior restraint as applied to the

freedom of the press (id. at 716):

“ The exceptional nature of its limitations places

in a strong light the general conception that liberty

of the press, historically considered and taken up by

the Federal Constitution, has meant principally, al

though not exclusively, immunity from previous re

straints and censorship.”

See Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, supra at 504. The

Court further noted that “ the immunity of the press from

previous restraint” was not made less necessary by the

fact that “ miscreant purveyors of scandal” may abuse

the freedom of the press. Quite the contrary, “ subsequent

punishment for such abuses as may exist is the appropriate

remedy, consistent with constitutional privilege” (id. at

720). Cf. Kunz v. New York, supra at 294-95. When, as

in the present case, an injunction issues to prevent the dis

tribution of literature, and especially when that injunc

tion is pursuant to an unconstitutional statute, the in

junction must be considered invalid as a prior restraint

unconstitutionally infringing on the appellants’ freedom

of press.

Indeed, in the present case, the violation is all the more

serious since the trial court explicitly found that there was

“ no evidence that the pamphlet was distributed” (R. 72).

What the court in fact acknowledged was that the defendants

had distributed copies of their newspaper, The Thunderbolt

(see R. 21), which had not been expressly enjoined. Al

though it was admitted that there was no announcement

of the meeting in the issue distributed (see E. 23, 25), the

court held that the newspaper “ was an artifice on the part

of someone to bring home the fact that the meeting was

going to be held while artfully evading the exact language

of the handbill that had been previously distributed” (R.

18

72). Thus, the high order of protection conferred by the

Constitution on the freedom of the press was arrantly dis

regarded. Indeed, even if Sections 3-4 and 3-5 had been

constitutional on their face and even if the injunction against

the original handbills had been valid, the Statute and in

junction would have had to be declared unconstitutional as

applied in the present case since, unlike even the statute

in Kingsley Books, Inc. v. Brown, 354 U. S. 436, 445 (1957),

they failed to withhold “ restraint upon matters not al

ready published and not yet found to be offensive.”

B. Section 14-53 of the City Code.

The reasons for invalidating Section 14-53 of the Fair-

field Code as an unconstitutional prior restraint (see supra,

part I B ) are equally applicable for purposes of invalidat

ing the injunction issued pursuant to the ordinance.

The record here is barren of evidence of any danger of

violence, even is such evidence were relevant. See Part III

(B) (3), infra. The plaintiff’s bill of complaint contains

no factual allegations to support its conclusions that the

purpose of the meeting was “ to create ill will and disturb

ances between the races,” and that it “ will constitute a

public nuisance, injurious to the health, comport, or welfare

of the City of Fairfield and * * * is calculated to create a

disturbance, incite to riot, disturb the peace, and disrupt

the peace and good order in the City of Fairfield” (R. 2).

The record clearly shows that a meeting held by the de

fendants on the previous evening had been “ a very peace

able, normal meeting” (R. 47). Moreover, the police officer

who arrested appellant Fields admitted that there was no

disturbance of any kind at the site of the scheduled meeting

either before or at the time of the arrest. He further testi

fied that he did not see Dr. Fields fight with anyone, that

there was “ no trouble at all” and that the entire situation

was “ very peaceful” (R. 19).

Even if the prior restraint had been valid as to a meeting

held in the street or a public park it could hardly have been

19

applicable to a meeting of the National States Rights Party

—a political party—which was to be held in a private hall,

“ above the Car Wash” (R. 4). See Kunz v. New York,

supra at 307 (Jackson, J., dissenting). This Court has con

sistently circumscribed the power asserted by a State to

prohibit a peaceful public meeting held in a private hall

merely because the purpose of the meeting was disagreeable,

to the government.

Thus, for example, in De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353

(1937), De Jonge’s “ sole offense as charged # * * was that

he had assisted in the conduct of a public meeting, albeit

otherwise lawful, which was held under the auspices of the

Communist Party” (299 U. S. at 362). The Court, holding

the conviction repugnant to the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment, said (id. at 365) :

“ The holding of meetings for peaceable political

action cannot be proscribed. Those who assist in the

conduct of such meetings cannot be branded as crimi

nals on that score. The question, if the rights of free

speech and peaceable assembly are to be preserved, is

not as to the auspices under which a meeting is to be

held but as to its purpose; not as to the relations of

the speakers, but whether their utterances transcend

the bounds of the freedom of speech which the Con

stitution protects. If the persons assembling have

committed crimes elsewhere, if they have formed or

are engaged in a conspiracy against the public peace

and order, they may be prosecuted for their con

spiracy or other violation of valid laws. But it is a

different matter when the State, instead of prosecut

ing them for such offenses, seizes upon mere partici

pation in a peaceable assembly and a lawful public

discussion as the basis for a criminal charge.”

Similarly, in Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 (1945), an

official of a labor union was held in contempt of a restraining

order—issued ex parte, as here— that forbade him from vio

lating a Texas statute regulating the solicitation of member

ship in trade unions. The order was issued in anticipation

20

) of a meeting at which the appellant was scheduled to speak.

He appeared and spoke at the meeting, and was held in

contempt. The Court, holding that the statute contravened

the First Amendment, stated, (323 U. S. at 536):

“ The assembly was entirely peaceable, and had

no other than a wholly lawful purpose. The state

ments forbidden were not in themselves unlawful,

had no tendency to incite to unlawful action, involved

no element of clear and present, grave and immediate

danger to the public welfare. * * * We have here

nothing comparable to the case where use of the word

‘ fire’ in a crowded theater creates a clear and present

danger which the State may undertake to avoid or

against which it may protect. Schenck v. United

States, 249 U. S. 47.”

i What was thus involved was the basic right of freedom of

expression which could not be circumscribed. As the Court

explained (id. at 540) :

“ If the exercise of free speech and free assembly

cannot be made a crime, we do not think this can be ac

complished by the device of requiring previous reg

istration as a condition for exercising them and mak

ing such a condition the foundation for restraining in

advance their exercise and for imposing a penalty for

violating such a restraining order. So long as no

more is involved than exercise of the rights of free

speech and free assembly, it is immune to such a

restriction. * * * We think that a requirement that

one must register before he undertakes to make a

public speech to enlist support for a lawful movement

is quite incompatible with the requirements of the

First Amendment.”

The holdings in Be Jonge and Thomas have direct ap

plicability here. The sentencing court revealed quite can

didly the true purpose for issuing the restraining order.

As it stated (R. 72):

“ Back several years ago we did have a movement

to move into one of our public parks here but that

21

was straightened out within a matter of a few weeks.

* * * And it is the intention, I know, of the public

officials * * # that we are going to do everything we

can to maintain that status quo. We are going * # *

to do everything that we can to keep people from

agitating trouble.”

Since, however, a State “ may not suppress free communi

cation of views # # * under the guise of preserving desirable

conditions” (Cantwell v. Connecticut, supra at 308), the

court order, pursuant to Section 14-53, enjoining the meet

ing from taking place, was clearly an unconstitutional prior

restraint. We believe that a municipality has no power to

grant or deny the right to meet on private property except

as to non-discriminatory regulations intended to control

structural or fire hazards—which is not to say it has not

the power to invoke the criminal law for valid offenses

committed on the private premises. See Part 111(B)(3),

infra.

I l l

Appellants were not foreclosed from testing the

injunction’s constitutionality by violating its terms.

It was the view of the Alabama Supreme Court that, on

the authority of United Mine Workers v. United States, 330

U. S. 258 (1947), the appellants were foreclosed from chal

lenging the constitutionality of the injunction against them

“ in collateral proceedings on appeal from a judgment of

conviction for contempt of the * * * decree” (R. 89). The

court’s reliance on Mine Workers is misplaced.

Although Alabama may, if it chooses, adhere to Mine

Workers as a matter of state law in a variety of cases, its

reliance on the doctrine of that case where First Amendment

rights are concerned cannot be sustained. We point out

below (A) that the Mine Workers doctrine, by its own

terms, has no application to free speech cases in general,

22

and (B) that Mine Workers aside, this Court must find that

appellants have the right to attack the constitutionality of

both the ordinances and injunction in the course of contempt

proceedings.

A. The Mine Workers doctrine does not apply to First

Amendment cases.

Mine Workers involved at least three essential elements

which are absent here. First, Mine Workers revolved

around a question of conduct subject to statutory regula

tion rather than conduct fully protected by the Constitution.

Second, it involved a complex problem of statutory inter

pretation4 in a factual setting that had not previously re

ceived judicial consideration. Third, it was concerned with

a problem that arose in the context o f an industrial dispute.

In the instant case, the subject matter of the dispute

is plainly protected by the Constitution—more particularly,

the First Amendment which deals with “ preferred rights.”

The qualitative distinction between conduct which may be

regulated by statute and conduct which is specially pro

tected by the Constitution, is pointed out in West Virginia

State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U. S. 624, 639

(1943) :

“ The right of a State to regulate, for example,

a public utility may well include, so far as the due

process test is concerned, power to impose all of the

restrictions which a legislature may have a ‘ rational

basis’ for adopting. But freedoms of speech and of

press, of assembly, and of worship may not be in

fringed on such slender grounds. They are suscept

ible of restriction only to prevent grave and immedi

ate danger to interests which the state may lawfully

protect.”

Second, there is no substantial doubt to be resolved

either about the scope of the rights asserted here or about

4 The Norris-LaGuardia Act, 47 Stat. 70, c. 90, 29 U. S. C. § 101.

23

the invalidity of the ordinances in question. The rights are

clearly protected and the ordinances patently unconstitu

tional. See Parts I and II, supra. Although this case, like

Mine Workers, has evoked “ extended argument, lengthy

briefs, [and] study and reflection,” to use Mr. Justice

Frankfurter’s words (330 U. S. at 310), those exertions

have been forthcoming not because they are necessary “ be

fore final conclusions could be reached regarding the proper

interpretation of the legislation controlling this case,” hut

merely to demonstrate that those conclusions regarding the

First Amendment have been reached by this Court long

ago.5

Third, where industrial conflicts are concerned, this

Court has frequently set such cases apart from the main

stream of First Amendment cases even though, in one

respect or another, they contain elements of speech,

assembly or press.6 But where political liberty is con

cerned—and we remind the Court that the. association which

is one of the appellants here is a political party—the limita

tions that may be imposed on union activity have no appli

cation whatsoever. This is particularly the case where

5 Compare Mr. Chief Justice Vinson's observation that:

“ We insist upon the same duty of obedience where, as here,

the subject matter of the suit, as well as the parties, was

properly before the Court; where the elements of federal juris

diction were clearly shown; and where the authority of the

Court of first instance to issue an order ancillary to the main

suit depended upon a statute, the scope and applicability of

which were subject to substantial doubt.” 330 U. S. at 294

(emphasis supplied)

Mr. Justice Frankfurter described the issue in the case as

“ complicated and novel.” 330 U. S. at 310.

6 See, for example, Local Union 10 v. Graham, 34S U.S. 192

(1953) ; Hughes v. Superior Court, 339 U. S. 460 (1950) ; Building

Service Employees v. Gazzam, 339 U. S. 532 (1950) ; Giboney v.

Empire Storage & Ice Co., 336 U. S. 490 (1949) ; Carpenters and

Joiners Union v. Ritter’s Cafe, 315 U. S. 722 (1942).

24

the rights asserted by the party are not only of constitu

tional dimension, but where they are without question fully

protected by the Constitution as well.

In addition, two cases decided since Mine Workers

further support the view that appellants may not be fore

closed from testing the underlying validity of the injunc

tion simply because they have asserted the right in the

course of contempt proceedings.

In United Gas, Coke and Chemical Workers v. Wisconsin

Employment Relations Board, 340 U. S. 383 (1951), peti

tioners had been prohibited from striking by an ex parte

restraining order under the terms of the Wisconsin Public

Utility Anti-Strike Law, and found in contempt.

This Court reversed. It found that Congress, under the

National Labor Relations Act of 1935 as amended, had

occupied the field of peaceful strikes for higher wages in

the industry the state sought here to regulate. Mine

Workers is not to be found in the majority or dissenting

opinions.

In In the Matter of Green, 369 U. S. 689 (1962), Green

was an attorney representing a labor union. A labor-

management controversy arose and the employer obtained

an injunction from the Ohio state courts forbidding union

members from picketing. The injunction was issued ex

parte. Green believed the order was invalid because issued

without a hearing required by state statute and because the

controversy was properly one for the National Labor Rela

tions Board. Consequently, he advised the union officials

that the restraining order was invalid and that the best way

to contest it was to continue picketing and, if the pickets

were held in contempt, to appeal and test the order of

commitment by habeas corpus.

The plan was followed and four pickets were arrested.

At the hearing on the contempt charge, Green informed the

25

court that it was he who had advised the union to test the

injunction by risking contempt. He was held in contempt

for disobeying “ a lawful writ, process, order, rule, judg

ment, or command, of the court under the Ohio statutes.”

This Court reversed. It held that “ a state court is

without power to hold one in contempt for violating an

injunction that the state court had no power to enter by

reason of federal preemption.” 369 U. S. at 692. The case

was remanded for a hearing to determine whether the state

court was acting in a field reserved exclusively by Congress

for the federal agency. Mine Workers was distinguished

on the ground that it ‘ ‘ involved a restraining order of a

federal court and presented no question of preemption of

a field by Congress where, if federal policy is to prevail,

federal power must be complete.” Id. note l .7

United Gas and Green both indicate that when a state

court’s power to issue an injunction in a labor dispute has

been withdrawn by Congress, which vested an administra

tive agency and the federal courts with authority to act in

that area, an injunction issued by a state court which has

presumed to exercise its jurisdiction may be disobeyed.

A fortiori, when the power of a state court to act is fore

closed by the Constitution as in this case, any injunction

which it issues may likewise be disobeyed with impunity.8

1. Even in Mine Workers own terms, the injunction in

this case was clearly frivolous and could he violated with

impunity.

Although Mr. Chief Justice. Vinson’s opinion in Mine

Workers nominally held that even if the restraining order

7 Cf. N A A C P v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 (1958).

8 Prior to Mine Workers, o f course, this Court had held that

the validity of judicial orders could be collaterally tested by violating

them. E x Parte Rowland, 104 U. S. 604 (1882) ; E x Parte Fisk,

113 U. S. 713 (1885); E x Parte Ayers, 123 U. S. 443 (1887);

In Re Sawyer, 124 U. S. 200 (1888).

26

were found invalid, its validity could not be tested by

violating its terms,9 he added that, “ A different result would

follow were the question of jurisdiction frivolous and not

substantial * * * ” 330 U. S. at 293.

Mr. Justice Frankfurter, who held that the restraining

order in Mine Workers could not be disobeyed even though

invalid (as he believed it to be), also declared that a

different result would follow if the question of jurisdiction

were frivolous. He compared the questions presented in

the. case before him with “ a question so frivolous that any

judge should have summarily thrown the Government out

of court without delay” 330 U. S. at 309.

“ Only when a court is so obviously traveling out

side its orbit as to be merely usurping judicial forms

and facilities may an order issued by a court be

disobeyed and treated as though it were a letter to

a newspaper. Short of an indisputable want of

authority on the part of a court, the very existence

of a court presupposes its power to entertain a con

troversy, if only to decide after deliberation that

it has no power over the particular controversy.

“ To be sure, an obvious limitation upon a court

cannot be circumvented by frivolous inquiry into

the existence of a power that has unquestionably

been withheld. Thus, the, explicit withdrawal from

federal district courts of the power to issue injunc-

9 The Chief Justice and the two Justices who joined in his opinion,

believed the order valid. Though they went on to declare that even

if the order were void the defendants were none the less required to

obey it, that much of their opinion was unnecessary to their decision

and therefore not binding. Justices Black and Douglas likewise

found the order valid, but therefore thought it unnecessary to decide

the academic problem of a void order. Justices Murphy and Rutledge

concluded both that the order was void and the contempt conviction

therefore invalid. Only Justices Frankfurter and Jackson held

the contempt conviction valid even though the order on which it

was based was, in their opinion, invalid. Thus, of nine Justices

writing five opinions, only Justices Frankfurter and Jackson squarely

adopted the proposition relied upon by the Alabama Supreme Court.

27

tions in an ordinary labor dispute between a private

employer and his employees cannot be defeated, and

an existing right to strike therefore impaired, by

pretending to entertain a suit for such an injunction

in order to decide whether a court has jurisdiction.

In such a case, a judge would not be acting as a

court. He would be a pretender to, not a wielder

of, judicial power.” 330 U. S. at 309-310 10

No member of the Mine Workers Court undertook to

supply a precise definition of a frivolous void order. It

is enough for the purposes of this case that the injunction

under scrutiny, being so patently violative of appellants’

First Amendment freedoms, be declared a nullity from

start to finish. The injunction was an assertion of power

based upon ordinances which, as we have shown above, are

not arguably constitutional. In addition, the power not

only was asserted to intrude upon the preferred constitu

tional rights of free speech, free press and free assembly,

it presumed to do so in the form of a prior restraint, a

particularly objectionable kind of censorship. See Congress

of Racial Equality v. Douglas, 318 F. 2d 95 (C. A. 5, 1963).

B. The primacy of First Amendment rights requires this

Court to hold that the injunction’s constitutionality may

be tested by violating its terms.

1. The injunction lays a forbidden burden on First

Amendment Rights.

Although we have discussed Mine Workers in order to

meet the Alabama Supreme Court on its own ground, we

10 All the Justices except two expressed the belief that there were

circumstances where an order of a court was so frivolous that its

violation could not be punished. Justices Black and Douglas, the

exceptions, expressed no view because, believing the Mine Workers

order valid, they declined to speculate on the consquences of violating

a void order.

28

believe as an original proposition that the doctrine of that

case has no place in First Amendment cases.11

Professor Paul Freund, in discussing the differences

(and similiarities) between prior restraint and subsequent

punishment, notes one particularly crucial difference where

restraining orders or temporary injunctions are concerned:

“ If disobedience of the interim order is ipso

facto contempt, with no opportunity to escape by

showing the invalidity of the order on the merits,

the restraint does indeed have a chilling effect beyond

that of a criminal statute.12

It is precisely that “ chilling effect” which is at stake in

this case.

The consequence of investing court orders, no matter

how void or oppressive, with impenetrable sanctity,13 is

11 The three principal commentators on Mine Workers think it

unworkable in any case. Watt, the Divine Right of Government by

Judiciary, 14 Univ. of Chicago Law Rev. 409 (1947); Cox, The

Void Order and the Duty to Obey, 16 Univ. of Chicago Law Rev.

86 (1948) ; Chafee, Some Problems of Equity (Univ. of Mich. Law

School, 1950) Chapters V III and IX.

12 The Supreme Court and Civil Liberties, 4 Vanderbilt Law

Rev. 533, 539 (1951). Professor Freund goes on to say:

“ To the extent, however, that local procedure allows such a

defense to be raised in a contempt proceeding, the special objec

tion to prior restraint growing out of the problem of interim

activity is obviated.”

W e agree, but it is our fundamental thesis that the question of

collateral attack is not just a matter of “ local procedure.”

13 To the extent that Mine Workers may be based upon the re

spect due the courts, that consideration must give way under the

circumstances of this case. This is the very situation anticipated by

Mr. Justice Frankfurter when he spoke of a court “ so obviously

traveling outside its orbit that it is merely usurping judicial forms

and facilities.”

The “orbit” referred to is the traditional function of courts, but

the acts of the Circuit Court in this case clearly go beyond that

29

made plain in this case. It is beyond question that the

appellants could not have been punished for distributing

their newspaper and holding their meeting if they had been

prosecuted directly under the ordinances in issue; and the

unconstitutionality of those ordinances could have properly

been raised as a defense. Staub v. Baxley, supra. But the

City of Fairfield, by interposing a temporary injunction

between appellants and the same ordinances, has devised

a method that, if ratified by this Court, will allow circum

vention of the Staub doctrine and confer on the states a

technique to nullify the precise purpose the First Amend

ment is intended to serve—full discussion of all matters of

public concern, which Mr. Justice Brandeis called “ a po

litical duty. ’ ’ 14

Public issues are frequently short run, and if the govern

ment were empowered to suppress discussion by the use of

an injunction, issued as here on the flimsiest grounds, the

purpose of the discussion may wTell have passed by the time

the appellate remedies were exhausted. For example, it

would enable a political candidate to be enjoined from

speaking during the campaign period preceding the day of

election. I f he violated the injunction he would be impris

oned ; if he bowed to the injunction and tested its validity in

“ orderly and proper proceedings,” the election will have

long been over. In either case, the electorate would not

function. That is, the decision by the Circuit Court— that the state

of events was such that public order would best be maintained by

prohibiting appellants’ meeting— is a decision to be made, if ever,

by the police. See, e.g., Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315 (1951).

But conceding that the States may empower their courts to make such

police-type decisions (see Kingsley Books v. Brown, 354 U. S. 436

(1957) ), the States must also be prepared to have the decisions

of their courts subject to the same scope of review as the decision

of the police in Feiner.

14 Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357, 376 (1927) (concurring

opinion ).

30

have heard him and the electoral process—perhaps the

raison d ’etre of free speech—would be crippled.15

15 The increasing reliance on ex parte preliminary injunctions—

and the threat they pose to the First Amendment— is indicated by

the following examples.

In April 1962, an Alabama Circuit Court Judge issued a tem

porary injunction against the President, student body and faculty

of Talladega College, members o f the Student Non-Violent Co

ordinating Committee, the Congress of Racial Equality, and several

individuals, forbidding the respondents from “ engaging in, sponsoring

or encouraging unlawful street parades, unlawful demonstrations,

unlawful boycotts, unlawful trespass, and unlawful picketing.”

State o f Alabama v. Arthur D. Gray, et al., Circuit Court of

Talladega County, in Equity, No. 9760.

A few days before election day in 1962, a judge of the California

Superior Court issued a temporary restraining order prohibiting

the distribution of a booklet which “ implied that Governor Edmund

G. Brown and other Democratic incumbents were soft on com

munism.” A hearing on the injunction was set for November 7th,

the day after election day. New York Times, October 30, 1962,

p. 22. On November 9th, the Democratic State Committee, the

plaintiffs, agreed to the dissolution of the restraining order. At the

same time Mr. Richard Nixon’s campaign manager asked for the

dissolution of a restraining order that had been issued prohibiting

distribution of two anti-Nixon pamphlets. New York Times, No

vember 10, 1962.

On November 29, 1962 a Justice of the New York State Supreme

Court issued a temporary restraining order prohibiting Plerbert

Aptheker from addressing the student body of the University of

Buffalo on the ground that Aptheker was a member o f the National

Committee of the Communist Party, New York Times, November

30, 1962.

On April 10, 1963, an Alabama Circuit Court Judge issued a

temporary injunction prohibiting anti-segregation demonstrations in

Birmingham. Dr. Martin Luther King and others were arrested

two days later for violating the injunction. New York Times, April

23, 1963, p. 20. Their convictions are now on appeal to the Alabama

Supreme Court.

In Tallahassee, Florida, a Circuit Court Judge issued a tem

porary restraining order on May 29, 1963 prohibiting anti-segrega

tion demonstrations. Two hundred and fifty-seven demonstrators

31

It was danger of this magnitude that Mr. Justice Rut

ledge foresaw in his prophetic dissent in Mine W orkers:

“ It would also be in practical effect for many

cases to terminate the litigation, foreclosing the sub

stantive rights involved without any possibility for

their effective appellate review and determination.

“ This would be true, for instance, wherever the

substantive rights asserted or the opportunity for

exercising them would vanish with obedience to the

challenged order. Cf. Ex Parte Fisk, 113 U. S'. 713.

The First Amendment liberties especially would be

vulnerable to nullification by such control. Thus the

constitutional rights of free speech and free assembly

would be brought to naught and censorship estab

lished widely over those areas merely by applying

such a rule to every case presenting a substantial

question concerning the exercise of those rights.

This Court has refused to countenance a view so

destructive of the most fundamental liberties. Thomas

v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516. These and other constitu

tional rights would be nullified by the force of invalid

orders issued in violation of the constitutional pro

visions securing them, and void for that reason. The

same thing would be true also in other cases involv

ing doubt, where statutory or other rights asserted

or the benefit of asserting them would vanish, for

practical purpose, with obedience.” 330 U. S. at 352.

# # #

were arrested on May 30 for violating the order. New York Times,

May 31, 1963, p. 1.

On June 6, 1963, a Mississippi Chancery Court Judge issued a

temporary injunction barring civil rights demonstrations in Jackson.

Thirteen local and national civil rights leaders, the NAACP, CORE,

and the trustees of Tougaloo Christian College were specifically

named in the order. New York Times, June 7, 1963, p. 14.

For an account of the destruction by injunction of a dissident

political movement, the International Workers of the World, see

Chafee, Free Speech in the United States (Harvard University

Press, 1946) 326-342.

32

“ Then also the liberties of our people would be

placed largely at the mercy of invalid orders issued

without power given by the Constitution and in con

travention of power constitutionally withheld by Con

gress.” 330 U. S. at 354.

By obtaining an ex parte injunction, and punishing for

contempt, the respondents have attempted to convert other

wise unconstitutional and void statutes into ones which can

successfully restrain and punish activities which would be

protected in the other situations described. However in

genious the City of Fairfield may be, it cannot punish

appellants’ constitutionally protected behavior. See Thomas

v. Collins, 323 U. S. at 540.16

2. Even if the ordinances or injunction here were argu

ably constitutional, their validity could be tested in con

tempt proceedings.

We urge, of course, that the ordinances in issue are

undeniably invalid on their face. But even if the ordinances

or injunction were arguably constitutional, that would not

alter appellants’ right to test their validity in a contempt

proceeding. In any case involving the First Amendment

it is irrelevant how the municipal authorities presume to

suppress speech or assembly. Whether it be by punishment

for not seeking a permit if one is ostensibly required (Staub

v. Barley, supra), or by contempt for violating an injunc

tion against such speech or dissemination (Thomas v. Col

lins, supra), the result must be the same. The focus must

be upon the activity sought to be engaged in, not the state’s

procedural scheme.

The only restrictions on speech or assembly which a

state or municipality can impose in consonance with the 18

18 Kingsley Books v. Brown, 354 U. S. 436 (1957) is not to

contrary. Though it upheld an injunctive scheme for the suppression

of obscene publications, it expressly left open the question whether

the issue of obscenity could be tested by violating the injunction.

354 U. S. at 443, n. 2.

33

preferred status of the First Amendment freedoms are

general and non-discriminatory regulations dealing with

soliciting and holding meetings upon the streets, parks and

public places of a town or city. The most that a municipality

can require even in this area is that an individual or group

request a permit for use of the public street or parks so that

the authorities can determine whether a conflicting meeting

was scheduled. See Parts I and II, supra.

If a permit is wrongfully refused, the meeting or solici

tation must be allowed notwithstanding, and a plenary

examination of the basis of the refusal—including the con

stitutionality of applicable statutes—will subsequently be

allowed in the courts. See the cases related in Staub v.

Baxley, supra at 323-324, notes 6-12.17 18 A fortiori, no injunc

tion can be issued which would force a postponement of the

speech or solicitation until the validity of the injunction has

been determined. To proceed in the face of an injunction

or a refusal to issue a. permit is the only way to prevent

circumvention of First Amendment privileges by over-

zealous officials bent on “ maintain[ing] the status quo”

(R. 72).18

Milton wrote in Areopagitica:

“ And though all the winds of doctrine were let

loose to play upon the earth, so Truth be in the fields,

17 Insofar as Poulos v. New Hampshire, 345 U. S. 395 (1953)

suggests the contrary, it has been overruled by Staub. Any rule that

would permit municipalities to forbid a speech or assembly and force

prior adjudication of the right, is inconsistent with the Fourteenth

Amendment.

18 See State ex rel. Liversey v. Judge o f Civil District Court, 34

La. Ann. 741 (La. Sup. Ct., 1882) ; E x Parte Tucker, 110 Tex. 335,

220 S. W. 75 (Tex. Sup. Ct., 1920) ; State v. Morrow, 57 Ohio

App. 30, 11 N. E. 2d 273 (Ohio Ct. of App., 1937) ; E x Parte

Henry, 147 Tex. 315, 215 S. W . 2d 588 (Tex. Sup. Ct., 1948), each

of which recognizes that the First Amendment can be served only

by allowing an injunction to be attacked in the course of contempt

proceedings.

34

we do injuriously by licensing and prohibiting to

misdoubt her strength. Let her and Falsehead

grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse in

a free and open encounter?”

If these words are to have any force in the present day,

the ‘ ‘ free and open encounter” must be permitted immedi

ately when public concern is high and can be directed against

the falsehood or injustice revealed by the speech. The