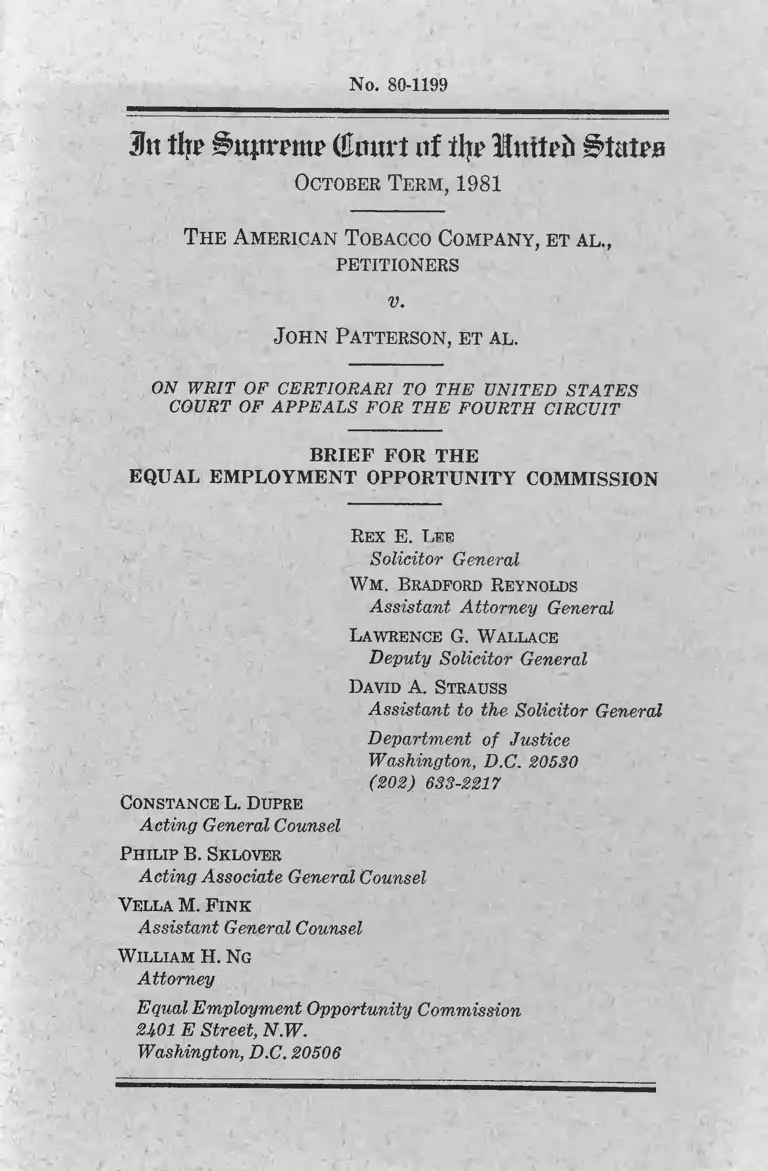

The American Tobacco Company v. Patterson Brief for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

Public Court Documents

November 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. The American Tobacco Company v. Patterson Brief for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 1981. aae0beb0-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f4859e25-68ff-4e18-b658-794910725172/the-american-tobacco-company-v-patterson-brief-for-the-equal-employment-opportunity-commission. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

No. 80-1199

3tt % ^itprrntp (Court of % lu ttr i itatrn

October Term , 1981

T h e A m erican T obacco Com pany , et al.,

PETITIONERS

V.

J o h n P atterson , et al .

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION

Rex E. Lee

Solicitor General

W m . Bradford Reynolds

Assistant Attorney General

Lawrence G. Wallace

Deputy Solicitor General

David A. Strauss

Assistant to the Solicitor General

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 633-2217

ConstanceL. Dupre

Acting General Counsel

P h il ip B. Sklover

Acting Associate General Counsel

Vella M. F in k

Assistant General Counsel

W illiam H. Ng

Attorney. . . "

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

2401 E Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20506

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether Section 703(h) of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 protected petitioners’ decision to adopt

racially discriminatory lines of employee progression

from a timely challenge.

0 )

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Opinions below...................... -..............................-.......... - 1

Jurisdiction. ....................... -.......... -....... - ......—------------- 2

Statement .......................................................................... 2

Summary of argument -....................................... 11-

Argument :

I. Section 703(h) does not bar a timely challenge

to the post-Act adoption of an aspect of a senior

ity system ..................................... 15

A. This case presents a challenge to the adop

tion, not the operation, of the lines of pro

gression ......................-.... - ................. -... -...... 15

B. By its terms, Section 703 (h) does not exempt

the decision to adopt an aspect of a seniority

system from Title VII ..................................— 19

C. Immunizing the decision to adopt an aspect

of a seniority system from timely challenge

would not serve the purposes of Section

703(h) and would thwart the central pur

poses of Title V I I ............-............... -.............. 22

II. Petitioners’ lines of progression are not a bona

fide aspect of a seniority system .......... - ............ 35

Conclusion ......................... ............................. .................. I 2

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Alabama Power Co. V. Davis, 431 U.S. 581 ........... 30

Albemarle Paper Co. V. Moody, 422 U.S. 405.......21, 27, 41

Alexander V. Aero Lodge No. 735, 565 F.2d 1364,

cert, denied, 436 U.S. 946 .......... ......... -.............. 18

(III)

IV

Cases—Continued Page

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36..... 27

Alexander V. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 .................... 38

Bartmess V. Drewrys U.S.A., Inc., 444 F.2d 1186.... 20

California Brewers Association V. Bryant, 444 U.S.

598 _________ __ ________ 26, 30, 31, 33, 34-35, 36, 37

Carson V. American Brands, Inc., No. 79-1236

(Feb. 25, 1981) ...... .................... ..... ....... .... ...... 27

Chardonw. Fernandez, No. 81-249 (Nov. 2, 1981).. 19

Christiansburg Garment Co. V. EEOC, 434 U.S.

412 .......................................... ............. ....... ..... . 17

Chromocraft Corp. V. EEOC, 465 F.2d 745 .......... . 27

Dandridge V. Williams, 397 U.S. 471 ....................... 37

Dayton Board of Education V. Brinkman, 443 U.S.

526 ........... ............ ............... ........ ...... ......... ......... 37

Delaware State College V. Ricks, 449 U.S. 250...... . 18, 20

Dothard V. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321 ............ .......... 17, 41

Emporium Capwell Co. V. Western Addition Com

munity Association, 420 U.S. 5 0 -------- ---- ------- 20

Ford Motor Co. V. Hoffman, 345 U.S. 330 ------- ..... 31

Franks V. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S.

747 .................... ......... ....... ........ - ...... ...17, 21, 23, 26, 28

Fumco Construction Corp. V. Waters, 438 U.S.

567 ......................... .. .............. ........ ........ 33-34

Griggs V. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424....11-12, 17,19, 29,

33, 34, 41

Hameed V. International Association of Bridge

Workers, Local 396, 637 F.2d 506 —__ _____ ... 37

Hankerson V. North Carolina, 432 U.S. 233 ........... 37

Humphrey V. Moore, 375 U.S. 335 __ ___ __ ____ 30

Hunter V. Westinghouse Electric Corp., 616 F.2d

267 .......... ............... ____ ____ _ _ ________ 16

International Brotherhood of Teamsters V. United

States, 431 U.S. 324...—.9 ,18, 22, 23, 25, 30, 33, 35, 36,

37, 41

International Union of Electrical Workers V. Rob

ins & Myers, Inc., 429 U.S. 229 _____ _________ 16

Jersey Central Power & Light Co. v. Local 327,

IBEW, 508 F.2d 687 .+ ,H.V................................ . 31

V

Cases—Continued Page

Laffey V. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 567 F.2d 429,

cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1086 .......... ...... ..... -.......... 18

Local Lodge No. 1&24, International Association of

Machinists V. NLRB, 362 U.S. 411 ........... ......... 21

McDonnell Douglas Cory. V. Green, 411 U.S. 792.... 39, 41

Mohasco Cory. V. Silver, 447 U.S. 807 ............. ..... 16

Nashville Gas Co. V. Satty, 434 U.S. 136........ ...... 19

Newman V. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390

U. S. 400 .................................... .............. .............. 17

Occidental Life Insurance Co. V. EEOC, 432 U.S.

355 .... - ........ ....... .................... ,...... -.... ............... 27-28

Old Colony Trust Co. V. Commissioner, 301 U.S.

379 ..................... .................. -....... ...................... - 20

Personnel Administrator of Massachusetts v.

Feeney, 442 U.S. 256 ............................ -.... . 39,40

Pettway V. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d211 .......................... ............ ;....,.... ....... :--- ------- 29

Rosen V. Public Service Electric & Gas Co., 477

F.2d 9 0 ....... ....................... - ....... ............... —----- 20

Rowe V. General Motors Corp., 957 F.2d 348 ------- 38

Sears V. Bennett, 645 F.2d 1365, petition for cert,

pending sub nom. United Transportation Union

V. Sears, No. 81-221......................... ........ ........... 40

Trans World Airlines, Inc. V. Hardison, 432 U.S.

63 ........................................................... -......... ~~~ 30,37

United Air Lines, Inc. V. Evans, 431 U.S. 553----- 18

United States V. Georgia Power Co., 634 F.2d 929,

petition for cert, pending sub nom. Local 8U,

IBEW V. United States, No. 80-2117 _____ .____ 36, 37

United States V. Hayes International Corp., 456

F.2d 112 ............ ........................... ... - ........ - - - - - 29

United States V. N.L. Industries, Inc:, 479 F.2d

354 ........... -................... - ...................... - - ............ 27

United Steelworkers of America V. Weber, 443 U.S.

193 —.......... ....... -.................... .......... ..... ............. - 35

Village of Arlington Heights V. Metropolitan Hous

ing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252 ---- -------- 39, 40

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 ....................... 39

VI

Statutes and rule: Page

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII, 42 U.S.C.

2000e et seq...... .......... .............................. ....... . 2

Section 703(a) (2), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(a) (2).. 12,19,

21

Section 703 (c) (2), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(c) (2).. 19

Section 703(c) (3), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(c) (3).. 19, 21

Section 703(h), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2 (h) ........... passim

Section 706(b), 2000e-5(b) .... ................. ...... 27

Section 706(e), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-(5) (e)..... . 16

Section 713(b), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-12(b) ____ 39

78 Stat. 260...... .................. ........................................ 15

Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(5) ....................................... 9

Miscellaneous:

Aaron, Reflections on the Legal Nature and En

forceability of Seniority Rights, 74 Harv. L.

Rev. 1532 (1962) ............... .......... ............ ..... . 30

110 Cong. Rec. (1964) :

p. 486 ........ ........................................................ 24

p. 1518__________ ____ _____ ________ __ 24

p. 2726 .... ............ ................... ....... - ................ 21, 24

p. 2804 ......... ............. ......... ................... ........... 23

p. 5094 ..................... ....... ....... ......... ................ 32

p. 5423 ................ ......... - .......... ............... ........ 32

p. 6549 ........ ............ ........................... ........ ...... 25, 32

pp. 6553-6554 ______ _____ _______ ____ ___ 32

p. 6564 ....... ..... .. .................... ....... ....... ........... 25

p. 6566 ____ ___ ___ ____ ____ _____ - ........ 14

p. 7206 .......... ............ ................ -........... - ......... 23

p. 7207 ....... 25

p. 7213_________ 25

pp. 7266-7267 „„_______ ____ ~~~............... . 21

p. 9111..... ........ - ...... -......... .......... -.............. . 24

p. 9113 ......... 24

p. 11471 24

p. 11486 .................... - ..... ........ ................ ........ 38

p. 11848 ............ ............. -----....... ....... ............ 32

p. 11931 _______ 23

p. 12723 ____ ___ ______ -.................... -.......... 18, 23

VII

Miscellaneous—Continued Page

Cooper & Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under Fair

Employment Laws: A General Approach to Ob

jective Criteria of Hiring and Promotion, 82

Harv. L. Rev. 1598 (1969) ..... ........... ...... .......... 31,36

EEOC, Legislative History of Titles VII and XI

of Civil Rights Act of 1964 (1964) .......... .......... 21

31 Fed. Reg. 10270 (1966) ...................................... 39

H.R. 7152, 88th Cong., 2d Sess. (1964) ............... 23

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963).... 24, 30,

32

Vaas, Title VII: Legislative History, 7 B.C. Indus.

& Com. L. Rev. 431 (1966) .................................. 21

1\\ tip &xx$xm? (to rt rtf tip Httltrb dtatrjs

October T erm , 1981

No. 80-1199

T h e A m erican T obacco Com pany , et al .,

PETITIONERS

V.

J o h n P atterson , et al .

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION

OPINIONS BELOW

The en banc decision of the court of appeals (App.

135-184) is reported at 634 F.2d 744. The decision

of the panel of the court of appeals (App. 112-134)

is reported at 586 F.2d 300. The decision of the

district court (App. 109-111) is unofficially reported

at 18 Fair Empi. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 371. An earlier

decision of the court of appeals (App. 70-107) is re

ported at 535 F.2d 257. Earlier opinions of the

district court (App. 2-49, 50-69) are unofficially re

ported at 11 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 577 and

8FairEmpl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 778.

( 1)

2

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court of appeals was entered

on November 18, 1980. The petition for a writ of

certiorari was filed on January 16, 1981, and granted

on June 15, 1981. The jurisdiction of this Court rests

on 28 U.S.C. 1254(1). ‘

STATEMENT

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

and the private respondents brought these actions,

which were consolidated for trial in the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of

Virginia in 1973. Both suits alleged that petitioners’

promotion and seniority practices had confined blacks

to low-paid, segregated jobs, in violation of Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000e et

seq. (App. 2-3) J

1. Petitioner American Brands, Inc., and its sub

sidiary, the American Tobacco Company, operate two

plants—the “Virginia branch” and the “Richmond

branch”—in Richmond, Virginia. Each branch is di

vided into a prefabrication department, which blends

and prepares tobacco for further processing, and a

fabrication department, which manufactures the fin

ished product (App. 16, 75). Petitioner Tobacco

Workers’ International Union and its affiliate, Local

182, are the collective bargaining agents for hourly-

paid production workers at both branches (App. 17).2

1 “App.” refers to the Joint Appendix filed in this Court.

“J.A.” refers to the Joint Appendix filed in the court of

appeals. “Exh. App.” refers to the Exhibits Appendix filed in

the court of appeals.

2 The international union was named as a defendant only

in the private action (App. 3).

3

Both the company and the union concede that until

at least 1963, they engaged in open race discrimina

tion involving every aspect of employment at the two

plants—jobs, cafeterias, lockers, and plant entrances

(App. 75). Petitioner union maintained two segre

gated locals; blacks were represented by all-black

Local 216, while whites were represented by all-

white Local 182 (App. 19). Black employees were

assigned to jobs in the “historically black” prefabri

cation departments and were generally not assigned

to jobs in the “historically white” fabrication de

partments (App. 77, 78, 33). Jobs in the prefabrica

tion departments pay less than jobs in the fabrication

departments (App. 33-34). The small proportion of

blacks in the fabrication departments generally held

manual labor or cleaning jobs (Exh. App. 46-48;

App. 33).

Seniority governed layoffs and promotions (App.

75). Under the seniority system maintained by pe

titioners until 1963, the prefabrication departments

each constituted one seniority unit and the fabrica

tion departments constituted separate seniority units

(App. 75). Thus an employee could transfer from

one of the predominantly black prefabrication depart

ments to one of the predominantly white fabrication

departments only by forfeiting his seniority.

In 1963, petitioners came under pressure from gov

ernment procurement agencies enforcing the anti-

discrimination obligations of government contractors

(App. 75; J.A. 202). They dropped departmental

seniority; instead, employees forfeited seniority only

when they transferred between the Richmond branch

and the Virginia branch (App. 75).3 At the same

3 The union locals were also merged in 1963, with the 350

members of the black local absorbed into the 1400-member

white local. None of the officers of the black local retained

his position (J.A. 202-203, 247, 500).

4

time, however, petitioners stopped using seniority

alone to determine who would be promoted. Instead,

employees had to apply for openings, and the openings

were not posted; employees learned of them only by

being canvassed by supervisors (App. 76, 28)—vir

tually all of whom were white.4 Promotions were

then awarded to the most senior “qualified” employee

who applied. The company did not maintain writ

ten job descriptions; “qualified” meant that an em

ployee “had filled a particular job before and was,

in the opinion of supervisory personnel, familiar with

it” (App. 28). Between 1963 and 1968, when this

promotions policy was in force, virtually all the va

cancies in the fabrication departments were filled by

white employees. Many of these employees had less

plant seniority than blacks (App. 32). The fabri

cation departments thus remained predominantly

white.® The district court held that this promotion

4 At the Virginia branch, the first black supervisor was

appointed in 1963. By 1969, only three of the 71 supervisory

employees were black (App. 34). The first black supervisor

at the Richmond branch was appointed in 1966, and by 1969

there remained one black supervisor among a total of approxi

mately 30 supervisory employees (App. 35). Between 1963

and 1969 there appear to have been more than 30, and per

haps more than 40, vacancies in supervisory jobs (compare

Exh. App. 130-131 with App. 96).

6 In the Virginia branch there were 82 blacks in the fabri

cation department in 1963 and 88 in 1968 (Exh. App. 47). The

Virginia branch fabrication department appears to have in

cluded approximately 660 employees (see Exh. App. 57). In

the Richmond branch there were six blacks in 1963 and 12 in

1968 in the fabrication department (Exh. App. 48) ; that de

partment included approximately 60 employees (see Exh. App.

58). The prefabrication departments, by contrast, were pre

dominantly black (see App. 77-78). Most of the blacks in

the fabrication departments continued to hold manual labor

or cleaning jobs (Exh. App. 33, 48).

5

policy was racially discriminatory (App. 8, 32), and

the court of appeals agreed (App. 75, 78).

In January 1968, the company began posting va

cancies, although it continued not to provide written

job descriptions (App. 21, 76). Then, according to

the company, on November 14, 1968,6 it developed

and proposed the establishment of nine lines of pro

gression. The union accepted and ratified the lines of

progression in 1969 (J.A. 246-247). Six of these

lines of progression are at issue before the Court.7

Each line of progression consisted of only two jobs.

Apparently no employee was eligible for the “top”

job in a line until he had worked at least one day

in the “bottom” job.8 According to the company,

8 Stipulations of fact adopted by the district court specify

that the posting system was instituted on January 15, 1968

(App. 21). The stipulation does not identify the date on

which the company proposed the nine lines of progression.

In his opening statement at trial, counsel for the company

said that “the[ ] lines of progression * * * were finally

set up at a meeting in November 1968 * * *” (Tr. 34). Russell

Penn Truitt, a member of the company’s board of directors

and director of manufacturing (Tr. 786, 789), testified at

trial that the “lines of progression Were established” (J.A.

570) at a meeting that was held on “November 14, 1968”

(J.A. 571).

The court of appeals stated that the lines of progression

were instituted in January 1968 (App. 143), but the court

made no reference to the company’s statements, and it was

immaterial to the court’s holding whether the lines were

adopted in January or November of 1968.

7 The district court held that the others did not violate

Title VII (App. 31-32) and respondents do not now challenge

this ruling.

8 Two lines appear to have had alternative bottom jobs. See

page 6, note 9 infra.

6

among employees who had worked in the “bottom”

job the one with the most seniority within the plant

would receive# the “top” job (App. 142-143 n.3).

Of the six lines at issue here, four consisted of nearly

all-white “top” jobs from the fabrication depart

ments linked with nearly all-white “bottom” jobs

from the fabrication departments; the other two con

sisted of all-black “top” jobs from the prefabrication

departments linked with all-black “bottom” jobs from

the prefabrication departments.9 The top jobs in the

“white” lines of progression were among the best

paying jobs in the plants (Exh. App. 155-163). While

it appears that more than two-thirds of the em

ployees in the two plants were in a line of progres

sion,10 very few of these employees were in the

9 The lines of progression at issue here are (App. 21-22,

31-32) :

1. Learner-adjuster (top)

Packing or making machine operator, Schmermund

boxer operator (bottom)

2. Examiner-making (top)

Catcher (bottom)

3. Examiner-packing (top)

Line searcher—Schmermund boxers (bottom)

4. Turbine operator (top)

Boiler operator (bottom)

5. Adt dryer operator (top)

Assistant adt dryer operator (bottom)

6. Textile dryer operator (top)

Assistant textile dryer operator (bottom)

Both jobs in lines 5 and 6 were in theffabri cation departments

(Plaintiffs’ Exh. 1), and both were all black (Exh. App. 160,

161, 171-172). All jobs in the remaining lines were located in

the fabrication department and were nearly all white (Exh.

App. 25-37, 46-48, 158-160).

10 In 1973, 646 of the 952 hoursly-paid workers in the two

branches were in the lines of progression. Only five of these

employees were in the “black” lines. Exh. App. 158-162.

7

“black” lines (Exh. App. 158-161). At the Virginia

branch, which was only 15% black (App. 34-35),

approximately four times as many black employees

as white employees were outside the lines of progres

sion entirely. At the Richmond branch, which was

one-third black (App. 35), approximately six times

as many blacks as whites were outside the lines (see

Exh. App. 158-162).

Between 1968, when the lines of progression were

instituted, and 1973, when these actions were brought,

there were approximately 30 vacancies in top jobs

in the “white” lines of progression (Exh. App. 38-

47). One of those vacancies was filled by a black;

the other 120 top positions continued to be held by

whites (see Exh. App. 158-161). The bottom jobs in

these lines were also predominantly white, despite

numerous vacancies (see Exh. App. 38-47, 158-161).

No whites held jobs in the “black” lines (see Exh.

App. 160-162). Segregation continued in other re

spects as well; in the two plants’ prefabrication de

partments, for example, approximately 81% and 92%

of the hourly-paid production workers were blacks

(App. 19, 77).

2. On January 3, 1969, 50 days after the company

proposed the establishment of the lines of progres

sion, three black employees (including one of the pri

vate respondents) filed charges with the EEOC, al

leging that they had been denied seniority and wage

benefits because petitioners discriminated on the basis

of race.11 Copies of these charges were served on pe-

11 App. 102, 6-7. Exhs. A-l to A-20 attached to the

Commission’s first request for admissions; company’s re

sponse to the EEOC’s first request for admissions.

8

titioners on February 19, 1969.12 The Commission

found reasonable cause to believe that petitioners’

seniority, wage, and job classification practices had

discriminatorily restricted blacks to low paying seg

regated jobs in violation of Title VII. When con

ciliation efforts failed, the Commission brought this

action.13

After an extensive trial, the district court held that

petitioners’ seniority, promotion, and job classifica

tion practices violated Title VII (App. 8-9). The

court found that petitioners maintained seniority and

other employment practices which continued the seg

regation that had been explicitly enforced until 1963

(App. 32). In particular, the court ruled that the

six lines of progression “perpetuated past discrimina

tion on the basis of * * * race” (App. 32), and be

cause petitioners offered no business justification for

the six lines, the district court held that they violated

Title VII and enjoined the company and union from

using them further (App. 31-32, 57).

In 1976, the court of appeals affirmed.14 It ex

pressly endorsed the district court’s finding that

“after the effective date of Title VII the company and

the union discriminated in the promotional policies

12 Exhs. B-l to B-7 of Commission’s first request for

admissions; company’s response to EEOC’s first request for

admissions; union’s response to EEOC’s first request for

admissions.

13 The EEOC also charged petitioners with sex discrimina

tion. The district court upheld this charge (App. 8) and

the court of appeals affirmed (App. 74). There is no need

to consider the claim of sex discrimination in connection with

the lines of progression at issue here.

14 The court of appeals modified the district court’s remedy

(see App. 83, 91) in ways that are not relevant here.

9

of their bargaining agreements” (App. 78). In par

ticular, the court agreed with the trial court that

the six lines of progression, the rule requiring

employees to forfeit their senority if they transferred

between branches, the reliance on the subjective eval

uations of white supervisors, and the failure to post

written job descriptions all violated Title VII. With

respect to jobs in the six lines of progression enjoined

by the district court, the court of appeals noted that

“ [mjost of these jobs were in the fabrication depart

ments. Since black employees had been largely ex

cluded from the fabrication departments, they held

few jobs in most of these lines and could not advance

despite their seniority” (App. 78-79). In this re

spect, the court of appeals ruled, the lines of progres

sion operated “in a manner similar to the [pre-1963]

segregated departmental seniority rosters” (App.

79), permitting the company to carry forward segre

gated employment patterns. This Court denied a pe

tition for a writ of certiorari. See 429 U.S. 920

(1976).

3. In 1977 petitioners moved to vacate the dis

trict court’s 1974 decree.1* Petitioners relied pri

marily on International Brotherhood of Teamsters

v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 353-354 (1977),

which held that Section 703(h) of the Civil Rights

Act, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(h), exempts certain bona fide

seniority systems from the provisions of Title VII.

Petitioners argued, among other things, that their

seniority systems, including the six lines of progres

sion, were bona fide and therefore not in violation of

16 The company and the union did not identify the basis for

their motion. The court below treated petitioners’ application

as a motion under Rule 60(b) (5) of the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure (App. 187 n .l).

10

Title VII. The district court declined to modify its

order, holding that petitioners’ “seniority system

* * * is not a bona fide system under Teamsters

* * * because this system operated right up to the

day of trial in a discriminatory manner * * * [and]

had a discriminatory genesis” (App. 110).

A panel of the court of appeals agreed that

“Teamsters requires no modification of the relief

we approved with regard to job descriptions, lines of

progression * * * or supervisory appointments” be

cause those employment practices were not part of a

seniority system and therefore did not fall within

Section 703(h) (App. 116). The court of appeals

then reheard the case en banc and held that Ҥ 703

(h) * * * has no application to [petitioners’] job

lines of progression policy, whether or not it be

considered a ‘seniority system’ * * * ![because] [ t] his

policy was not in effect at American in 1965 when

Title VII went into effect” (App. 142-143). The

court of appeals concluded that the “legislative his

tory of § 703(h) * * * demonstrates that Congress

intended the immunity accorded seniority systems by

§ 703(h) to run only to those systems in existence at

the time of Title VII’s effective date, and * * * to

routine post-Act applications of such systems” (App.

143-144). Because the lines of progression were

instituted in 1968 and thus did not create any pre-

Act expectations, the court of appeals did not disturb

the district court’s injunction against the six lines of

progression.16

16 The en banc court remanded for a hearing on, among

other things, the bona tides of the rule that seniority was

forfeited when an employee transferred between branches

(App. 145-146, 147-154).

In dissent, Judge Widener, joined by Judge Russell, asserted

that the lines of progression were established before the

11

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. The court of appeals’ judgment is correct, but

in our view its rationale is too broad. The court

overlooked the distinction between the decision to

adopt an aspect of a seniority system and the sub

sequent employment decisions made in implementing

the system. Unlike the court of appeals, we believe

that Section 703(h) protects applications of a sen

iority system even if the system, or the challenged

aspect of the system, was instituted after the effec

tive date of Title VII.

Respondents, however, filed a timely challenge to

the adoption of petitioners’ lines of progression. Sec

tion 703(h) does not immunize the decision to adopt

an aspect of a seniority system, when that decision

is properly challenged. By interpreting Section 703(h)

to protect the application of a seniority system but

not the decision to adopt an aspect of a seniority sys

tem, the Court can give full force to the language and

policies of that Section without undermining the cen

tral purpose of Title VII—something Section 703(h)

was never intended to do.

1. When petitioners instituted the lines of progres

sion, they established a newT qualification for the

“top” jobs; no matter how senior he might be, an

employee seeking a “top” job had to have served

in a “bottom” job. Because the “bottom” jobs in the

most desirable lines of progression had been deliber

ately reserved to whites, the decision to adopt the

lines of progression “operate[d] to ‘freeze’ the status

quo of prior discriminatory employment practices”

{Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 430

effective date of Title VII (App. 161-177) and that Section

703(h) immunizes the post-Act establishment of seniority

systems in any event (see App. 160 n .l).

12

(1971)), ensuring that virtually no blacks would

be promoted to “top” jobs. Moreover, the lines of

progression now at issue were not justified by a busi

ness necessity. It follows that permitting the lines of

progression to be instituted would have been incon

sistent with a central prohibition of Title VII—that

employers and unions may not “limit * * * or clas

sify” employees “in any way which would deprive or

tend to deprive any individual of employment op

portunities * * * because of * * * race” (42 U.S.C.

2000e-2(a) (2)).

2. At the same time, neither the language nor the

purposes of Section 703(h) require that the decision

to adopt the lines of progression be immunized. Al

though the distinction between adopting and imple

menting a provision of a collective bargaining agree

ment was established under the National Labor

Relations Act, on which Title VII was modeled,

Congress drafted Section 703(h) to protect only em

ployment decisions made “pursuant to” a seniority

system; the language of Section 703(h) does not cover

the decision to adopt an aspect of a seniority system.

The legislative history demonstrates that the prin

cipal purpose of Section 703(h) was to protect em

ployees’ seniority “rights”—that is, the expectations

employees acquire on account of having worked for a

period of time under a seniority system. A timely

challenge to the decision to adopt a new aspect of a

seniority system, such as respondents’ challenge to

petitioners’ decision to institute the lines of progres

sion, in no way threatens these expectations, for it

occurs before legitimate expectations can develop.

Indeed, it was the decision to adopt the lines of

progression which prevented employees from using

their seniority “rights” to obtain top jobs; in this

way, respondents’ challenge to the lines of progression

13

actually vindicated expectations based on the seniority

system.

Petitioners assert that unless they are free to

adopt such measures as the lines of progression policy

without regard to the prohibitions of Title VII, they

will be unable to adapt to changing circumstances.

But the courts below did not impose any extraordi

nary limitation on petitioners. They merely required

that petitioners justify the additional employment

qualifications imposed by the lines of progression

policy in the same way they would justify any other

employment qualifications that served the same pur

pose of filling jobs with properly trained and experi

enced employees. Because employees had developed

no expectations in the continued operation of the lines

of progression policy, the circumstance that that

policy was part of a seniority system should not ex

cuse petitioners from having to show that the lines

are not an artificial and unnecessary barrier to em

ployment with a discriminatory effect on blacks.

There is, to be sure, substantial basis for conclud

ing that Congress considered it inappropriate to re

quire employers and unions to show a business neces

sity for using the seniority principle to reconcile

members’ conflicting interests and otherwise to or

ganize the workplace. But the lines of progression

at issue here do not serve any of these functions;

rather, as petitioners acknowledge, they qualify the

use of seniority in order to serve the same manage

ment needs as other employment practices that would

undoubtedly be subject to the prohibitions of Title

VII. There is, therefore, no reason to exempt the

decision to adopt the lines of progression from those

prohibitions.

II. The Court may also affirm the judgment of

the court of appeals on the alternative ground that

14

the lines of progression policy is not bona, fide and

therefore not within Section 703(h). The district

court, on the basis of its extensive familiarity with

the case, held that the lines of progression policy

was not bona fide; this holding was not questioned

by the court of appeals and is strongly supported by

the record.

Petitioners maintained explicit segregation until

at least 1963. Under pressure from government agen

cies, they then modified their promotion practices,

ostensibly giving black employees the opportunity to

obtain jobs previously reserved for whites; but the

new system they adopted depended heavily on the

standardless, subjective evaluations of white super

visors. Consequently, the jobs previously reserved to

whites continued to be held by whites. The district

court and the court of appeals held that this promo

tion practice was racially discriminatory.

In 1968, petitioners, again under pressure from

the government, shifted to the lines of progression

policy. This policy had the predictable effect of con

tinuing the same segregated employment patterns

that had previously existed, essentially excluding

blacks from the better jobs. In view of both the

company’s and the union’s previous explicit com

mitment to segregation, and their previous choice of

practices that would continue segregation in effect,

there is a substantial basis for inferring that peti

tioners adopted the lines of progression practice at

least in part because it would continue the segre

gated employment patterns.

Moreover, petitioners were unable to identify the

business purposes served by the six lines of progres

sion at issue here—despite having an opportunity,

and every incentive, to do so at the first trial. Be

cause the lines did not serve a business purpose, and

15

did serve an objective the company and union had

long and persistently pursued—reserving the best

jobs for whites—the district court was justified in

concluding that the latter objective at least partially

motivated the decision to adopt the lines of progres

sion, rendering them not bona fide.

ARGUMENT

L SECTION 703(h) DOES NOT BAR A TIMELY CHAL

LENGE TO THE POST-ACT ADOPTION OF AN

ASPECT OF A SENIORITY SYSTEM

A. This Case Presents a Challenge to the Adoption,

Not the Operation, of the Lines of Progression

1. While the judgment of the court of appeals was

correct, its rationale, in our view, is too broad. Spe

cifically, the court of appeals overlooked the distinc

tion between a challenge to the adoption of a sen

iority system and a challenge to the system’s operation.

Contrary to the court of appeals, we believe that

Section 703(h) applies to a challenge to the opera

tion of an aspect of a seniority system, even if that

aspect was instituted after the effective date of Title

VII. But Section 703(h) should not apply to a timely

challenge to the post-Act adoption of an aspect of a

seniority system.

Respondents’ claim is properly seen as a challenge

to the adoption, not the operation, of the lines of

progression. The company asserted that the lines

were adopted on November 14, 1968, and the private

respondents filed a charge with the EEOC before

the statutory charging period elapsed.17 Until the

17 Respondents filed their charge within 50 days. At the

time the private respondents filed their charge, Title VII

generally required charges to be filed within 90 days of an

alleged violation. 78 Stat. 260. Section 706(e), added in 1972,

16

district court enjoined their operation, the lines were

applied in making various employment decisions, but

those applications merely furnished additional evi

dence in support of the claim that the decision to

institute the lines violated Title VII.

If respondents had not filed a timely challenge to

the adoption of the lines of progression, and had

instead challenged only subsequent promotion deci

sions made pursuant to the lines of progression policy,

Section 703(h) would, in our view, apply to their

claim. Such a claim could succeed only if the lines

of progression were not part of a seniority system 18

or were not bona fide, even though the lines were

adopted after the effective date of Title VII. But to

interpret Section 703(h) to bar a timely challenge

to the adoption of the lines of progression would

thwart the basic purpose of Title VII without any

sufficient justification in the language of Section

703(h) or the policies underlying that Section. Be

cause respondents made a timely challenge to the

now generally requires aggrieved persons to file a charge

with the EEOC “within one hundred and eighty days after

the alleged unlawful employment practice occurred.” 42 U.S.C.

2000e-5(e). See generally Mohasco Corp. V. Silver, 447 U.S.

807 (1980). This period should also apply here, because the

private respondents’ charge was pending with the EEOC on

March 24, 1972, the effective date of the 1972 amendment.

See, e.g., Hunter v. Westinghouse Electric Corp,, 616 F.2d

267 (6th Cir. 1980). See also International Union of Elec

trical Workers v. Robbins & Myers, Inc., 429 U.S. 229, 241-243

(1976).

18 In our view, the court of appeals panel was correct in its

conclusion that the lines of progression policy was not an

aspect of petitioners’ seniority system. See pages 35-37, note

31 infra. Throughout this discussion, however, we shall, like

the en banc court of appeals, assume arguendo that the lines

of progression are part of a “seniority * * * system” within

the meaning of Section 703(h).

17

adoption of the lines of progression, Section 703(h)

does not require modifying the district court’s in

junction against the use of the lines.

2. By adopting the lines of progression, petitioners

instituted a new qualification that had to be met by

employees seeking one of the high paying “top” jobs

formerly confined to whites. Irrespective of his sen

iority, and whatever his other qualifications, an em

ployee had to have served in one of the “bottom”

jobs. Because the “bottom” jobs were historically

confined to whites as well, the new qualification im

posed by the lines of progression predictably “op

erate [d] to ‘freeze’ the status quo of prior discrimi

natory employment practices” (Griggs v. Duke Power

Co., 401 U.S. 424, 430 (1971)); practically no blacks

were promoted to the “top” jobs. This new qualifica

tion was “not justified by any business necessity”

(App. 31-32).

These facts were found by the district court in

1974 and affirmed by the court of appeals in 1976,

and petitioners do not appear to take issue with them

here. It is a central policy of Title VII—“ ‘a policy

that Congress considered of the highest priority’ ”

(Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S. 412,

418 (1978), quoting Newman v. Piggie Park Enter

prises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968); see Franks v.

Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 763

(1976) )—that an employer or union may not impose

job qualifications which perpetuate the effects of past

discrimination without serving a busines necessity.

See Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321, 328-332

(1977) ; Griggs v. Duke Power Co., supra.

Petitioners nonetheless assert that they should be

allowed to reinstate the additional qualification im

posed by the lines of progression policy. In par

ticular, they claim that the lines of progression are

18

an aspect of a seniority system and are therefore

protected by Section 703(h). But the language of

Section 703(h) does not compel the result petitioners

seek; moreover, no purpose of Section 703(h) would

be served—and the central purpose of Title VII would

be disserved—by permitting this result. Congress

enacted Section 703(h) not to “narrow [the] ap

plication of * * * [TJitle [VII]” or undermine its

basic objectives but only to “clarif [y] its * * * intent

and effect.” 110 Cong. Rec. 12723 (1964) (remarks

of Sen. Humphrey) ; see International Brotherhood of

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 352

(1977). Here Section 703(h) can be fully reconciled

with the central purposes of Title VII by sustaining

our challenge to the adoption of the lines of progres

sion while not endorsing the court of appeals’ more

far-reaching assertions that Section 703(h) is inap

plicable to the operation of any aspect of a seniority

system if that aspect was instituted after the effec

tive date of Title VII.1'9

1,9 If a seniority system is not bona fide, then not only its

adoption but its application is unprotected by Section 703(h).

See, e.g., International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, supra, 431 U.S. at 353; Alexander v. Aero Lodge No.

735, 565 F.2d 1364, 1378 (6th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 436

U.S. 946 (1978). The application of such a discriminatory

system is a continuing violation which may be challenged as

long as the violation persists. See United Air Lines, Inc. V.

Evans, 431 U.S. 553, 560 (1977). See also Delaware State

College V. Ricks, 449 U.S. 250, 256-257 (1980) ; Laffey v.

Northwest Airlines, Inc., 567 F.2d 429, 473 (D.C. Cir. 1976),

cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1086 (1978). But if a seniority system

is bona fide, then in our view Section 703(h) protects the

application of the system, even if the system was instituted

after the effective date of Title VII. In other words, because

of Section 703(h), the application of a bona fide seniority

system is not a continuing violation.

19

B. By Its Terms, Section 703(h) Does Not Exempt

the Decision to Adopt an Aspect of a Seniority

System from Title VII

1. Under the terms of Section 703(a)(2), 42

U.S.C. 2000e-2 (a) (2), petitioners’ adoption of the

lines of progression was clearly an unlawful employ

ment practice. That section makes it illegal for an

employer “to limit * * * or classify his employees

* * * in any way which would deprive or tend to de

prive any individual of employment opportunities or

otherwise adversely affect his status as an employee,

because of such individual’s race * * Section

703(c)(2), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(c) (2), applies es

sentially the same prohibition to unions. See also

42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(c) (3). Petitioners restricted

eligibility for top jobs to those employees who had

held the bottom jobs; in this way they “limit[ed]”

employees and “classif [ied] ” them in ways that di

rectly “deprive[d] [and] tend[ed] to deprive” many

of them of certain “employment opportunities.” Be

cause petitioners’ decision to limit and classify em

ployees in this way gave effect to past intentional

discrimination, and served no business necessity, it

was racially discriminatory under Griggs v. Duke

P-ower Co., supra.20 See Nashville Gas Co. v. Satty,

434 U.S. 136, 141-143 (1977).

20 It is very likely that at the time the private respondents

challenged the adoption of the lines of progression policy,

that policy only limited their prospects and had not yet had a

concrete effect on their wages or conditions of employment.

But this did not bar their claim. Section 703(a) (2) refers to

“classifications]” or “limit[ations]” which affect employ

ment “opportunities” ; it is not confined to employment prac

tices or decisions which immediately affect wages or other

specific benefits. “ [T]he proper focus is on the * * * discrimi

natory act, not the point at which the consequences of the act

become painful.” Chardon v. Fernandez, No. 81-249 (Nov. 2,

1981) slip op. 2 (emphasis in original). Thus, for example, an

20

2. By contrast, the terms of the Section 703(h)

exemption do not cover petitioners’ decision to adopt

the lines of progression. Section 703(h) provides that

“it shall not be an unlawful employment practice for

an employer to apply different standards of compen

sation, or different terms, conditions or privileges of

employment pursuant to a bona fide seniority

system * * *.” This language addresses only decisions

made “pursuant to” a seniority system; here, it would

cover, at most, a decision not to promote a particular

employee to a top job because he had not worked in

a bottom job. The decision to adopt a sonority sys

tem is, plainly, not a decision made “pursuant to”

that system. See generally Old Colony Trust Co. v.

Commissioner, 301 U.S. 379, 383 (1937). Moreover,

in order to challenge the decision to adopt the lines of

progression, we need not claim that petitioners were

“apply [ing] different standards of compensation, or

different terms [and] conditions * * * of employ

ment” ; under Section 703(a) (2), it suffices that the

lines of progression policy classified and limited em

ployees in a way that adversely affected their

opportunities.

Congress could have drafted Section 703(h) to re

fer to decisions to adopt a seniority system, had it

employee can—and sometimes must—challenge a decision de

nying him tenure even while he continues to work for his

employer. See Delaware State College V. Dicks, supra. Simi

larly, active employees may challenge a discriminatory retire

ment plan. See, e.g., Bartmess V. Drewrys U.S.A., Inc., 444

F.2d 1186, 1188-1189 (7th Cir. 1971). See also Rosen V. Public

Service Electric & Gas Co., A ll F.2d 90, 94 (3d Cir. 1973). In

any event, the adoption of a seniority system in a collective

bargaining agreement binds employees in the bargaining unit,

and in that sense has an immediate impact on them. See gen

erally Emporium Capwell Co. V. Western Addition Community

Association, 420 U.S. 50 (1975).

21

wished to do so. The National Labor Relations Act

was the model for much of Title VII (see, e.g.,

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S.

747, 768-770 (1976); Albemarle Paper Go. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405, 419 & n .ll, 420 & n.12 (1975) ),'21

and the NLRA distinguishes between the adoption of

an unlawful term in a collective bargaining agree

ment and its subsequent implementation; the Court

has held that the adoption may be an unfair labor

practice, challengeable only within the statutory

charging period, while its implementation is not. See

Local Lodge No. 14.24, International Association of

Machinists v. NLRB, 362 U.S. 411 (1960). More

over, members of Congress pointed out that the lan

guage of Section 703(a)(2) referring to the

“limit [ing]” and “classify [ing]” of employees would

cover seniority systems (see, e.g., 110 Cong. Rec.

2726 (1964) (remarks of Rep. Dowdy)), but Con

gress did not extend Section 703(h) to “limitations”

and “classifications”—only to differences in employ

ment conditions that were the result of the applica

tion of seniority systems.22

21 See also 110 Cong. Rec. 7266-7267 (1964) (remarks of

Sen. Ellender) ; EEOC, Legislative History of Titles VII and

X I of Civil Rights Act of 1964, at 7-9 (1964); Vaas, Title VII:

Legislative History, 7 B.C. Indus. & Com. L. Rev. 431, 431 &

n.2 (1966).

22 By its terms Section 703(h) applies only to employers,

not to unions. In practice, Section 703(h) can operate to im

munize unions as well; for example, Section 703(c) (3) makes

it unlawful for a union “to cause or attempt to cause an em

ployer to discriminate against an individual in violation of

this section,” so union involvement in a practice protected by

Section 703(h) cannot by itself give rise to liability under

Section 703(c) (3).

But it is nonetheless significant that Congress referred only

to employers in drafting Section 703(h). The application of

a seniority system, especially insofar as it affects terms and

22

Thus while Section 703(h) exempts actions taken

in implementing a seniority system, nothing in Sec

tion 703(h) refers to the adoption or institution of

a seniority system. Petitioners themselves emphasize

(e.g., Union Br. 11) Senator Dirksen’s statement

that the language of Title VII “received meticulous

attention. We have tried to be mindful of every

word, of every comma, and of the shading of every

phrase” (110 Cong. Rec. 11935 (1964)). For these

reasons, the only conclusion to be drawn from the

language is that “the unmistakable purpose of

§ 703(h) [is] to make clear that the routine applica

tion of a bona fide seniority system would not be

unlawful under Title VII.” International Brother

hood of Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324,

352 (1977) (emphasis added).

C. Immunizing the Decision to Adopt an Aspect of

a Seniority System from Timely Challenge Would

Not Serve the Purposes of Section 703(h) and Would

Thwart the Central Purposes of Title VII

1. The distinction between the adoption and the

application of an aspect of a seniority system reflects

important congressional policies. The legislative his

tory shows that the central purpose of Section 703(h)

was not to ensure that employees and unions could

design and adopt whatever sort of seniority system

they desired; rather, Section 703(h) was intended to

protect the expectations employees acquired in the

continued operation of a seniority system. In other

words, Section 703(h) rests on a “congressional judg-

conditions of employment, is the responsibility of the em

ployer. By contrast, the decision to adopt a seniority system,

or a particular aspect of it, is jointly made by the employer

and the union. Thus Congress’s reference to employers alone

is further evidence that Section 703(h) was intended to cover

only the application, not the adoption, of a seniority system.

23

ment * * * that Title VII should not * * * destroy or

water down the vested seniority rights of employees

simply because their employer had engaged in dis

crimination prior to the passage of the Act.” ln-

ternational Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, supra, 431 U.S. at 353. A timely challenge to

the adoption of a seniority system does not endanger

this congressional policy, for it occurs before such

expectations can develop.

Section 703(h) was added to the Civil Rights Act

in response to criticism by opponents of the Act. See

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, supra, 431 U.S. at 352.2S Those opponents

repeatedly argued that “Title VII would undermine

the vested rights of seniority” (110 Cong. Rec. 7206

(1964) (statement of Sen. Clark, quoting Sen. Hill)).

The minority report of the House Committee that

favorably reported the bill became the Civil Rights

Act charged that Title VII would “seriously im-

2:3 Section 703 (h) was not part of the bill passed by the

House, H.R. 7152, 88th Cong., 2d Sess. (1964). See 110

Cong. Rec. 2804 (1964) ; Franks v. Bowman Transportation

Co., 424 U.S. 747, 759 (1976). That bill was sent directly to

the Senate floor where it was filibustered; Senators Mansfield

and Dirksen eventually submitted a substitute bill that broke

the filibuster. See Vaas, Title VII: Legislative History, supra,

7 B.C. Indus. & Com. L. Rev. at 445. Section 703 (h) first ap

peared as part of this substitute bill. 110 Cong. Rec. 11931

(1964). Senator Humphrey, one of the drafters of the substi

tute, explained that Section 703(h) did not alter the meaning

of Title VII but “merely clarifie[d] its present intent and

effect.” 110 Cong. Rec. 12723 (1964) ; see Franks v. Bowman

Transportation Co., supra, 429 U.S. at 761. Thus, as petition

ers implicitly acknowledge, statements of House proponents

of Title VII about its effects on seniority, and statements made

by Senate proponents before Section 703 (h) was proposed, are

evidence of the meaning of Section 703(h).

24

pair * * * [t]he seniority rights of employees in cor

porate and other employment * * H.R. Rep. No.

914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. 64-65 (1963). Another

opponent argued that under Title VII “benefits which

organized labor has attained through the years would

no longer be matters of ‘right’ * * 110 Cong.

Rec. 486 (1964). Title VII, opponents charged,

would “destroy union seniority” which was a “most

valuable asset” (H.R. Rep. No. 914, supra, at 71;

emphasis in original) and would undermine “estab

lished seniority” (110 Cong. Rec. 2726 (1964)). Op

ponents of Title VII outside Congress claimed that it

would “placet] in jeopardy” the “seniority rights of

union members.” See 110 Cong. Rec. 9111 (1964).

The bill’s defenders answered these charges in the

same vein; they focused on employees’ expectations

about the continued operation of seniority systems.

Thus the bill’s supporters accused their opponents of

attempting to “put [people] in fear about * * * sen

iority” by falsely suggesting that under Title VII

“seniority systems would be abrogated and * * *

white men’s jobs would be taken and turned over to

[blacks].” 110 Cong. Rec. 11471 (1964). This was

“a cruel hoax * * * [that] generates unwarranted

fear among those individuals who must rely upon

their job or union membership to maintain their ex

istence.” 110 Cong. Rec. 9113 (1964). The chair

man of the House committee that reported the bill

said: “It has been asserted * * * that the bill would

destroy * * * employee rights vis-a-vis the union and

the employer. This again is wrong.” 110 Cong. Rec.

1518 (1964) (statement of Rep. Celler). Other House

proponents explained that “ [T]itle VII * * * does not

permit interferences with seniority rights of em

ployees or union members.” 110 Cong. Rec. 6566

(1964). The Senate managers, Senators Humphrey

25

and Kuchel, explained that “ [t]he full rights * * * of

union membership * * * will in no way be impaired”

(110 Cong. Rec. 6549 (1964) (Sen. Humphrey))

and that “seniority rights [would not] be affected by

this act” (110 Cong. Rec. 6564 (1964) (Sen.

Kuchel)).

Perhaps the most “authoritative indicators of [the]

* * * purpose [of Section 703(h)]” (International

Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States, supra,

431 U.S. at 352) are memoranda submitted during

the Senate debate by Senators Clark and Case. The

theme of those memoranda was that Title VII would

not interfere with seniority “rights” or expectations

based on seniority systems already established and in

operation (110 Cong. Rec. 7207, 7213 (1964)):

[I] t has been asserted that title VII would un

dermine vested rights of seniority. This is not

correct. Title VII would have no effect on sen

iority rights existing at the time it takes effect.

* * * * *

Title VII would have no effect on established

seniority rights. Its effect is prospective and

not retrospective.

Thus it seems clear that the principal purpose of

Section 703(h) was to make explicit Congress’s in

tention not to “destroy” the “rights” that employees

acquired under seniority systems. That is, Title VII

was not to interfere with employees’ expectations

that a seniority system, once lawfully instituted,

would continue to operate.

This conclusion is subject to two qualifications.

First, as we will explain (pages 30-31, infra), it

cannot fairly be said that this was the only purpose

of Section 703(h) ; Congress also recognized the im

portant role that seniority plays in collective bargain

ing, and its historic importance to workers. Second,

26

while Section 703(h) did protect employees’ seniority

expectations to some degree, it did not insulate those

expectations entirely from adjustment. It is well

established, for example, that a violation of Title VII

may be remedied by an “award of the seniority credit

[a victim of discrimniation] presumptively would

have earned but for the wrongful treatment” even if

“such relief diminishes the expectations of other,

arguably innocent, employees * * Franks v. Bow

man Transportation Co., supra, 424 U.S. at 767, 774.

Nonetheless, the legislative history shows that in

passing Section 703(h) Congress’s primary concern

was with employees’ expectations under seniority sys

tems that were in operation. A timely challenge to

the adoption of an aspect of a seniority system—

such as respondents’ challenge to the lines of progres

sion—in no way impairs these expectations. Respond

ents challenged the lines of progression soon after

they were established.24 Petitioners were notified of

124 Judge Widener, dissenting from the en banc decision of

the court of appeals, argued that the lines of progression

were adopted before 1965. But Judge Widener made no

reference to the company’s explicit statement that the lines of

progression were “set up” and “established” on November 14,

1968. See page 10, note 16 supra. In any event, Judge Widen-

er’s argument was simply that between 1963 and 1968, when

company supervisors were using their discretion to decide

whether an applicant for a job was “qualified,” they would

consider, together with a variety of other factors, the appli

cant’s experience in other jobs in the plant (App. 162, 169).

This cannot be enough to show that there were defined lines of

progression that were an aspect of a seniority system. See

California Brewers Association V. Bryant, 444 U.S. 598, 609-

610 (1980) (“ [A] standard that gives effect to subjectivity”

“depart [s] significantly from commonly accepted concepts of

27

the challenge within six weeks.25 Thus employees

could not have justifiably relied on the continued ex

istence of the lines of progression and developed

legitimate expectations based on the lines.26 See Oc-

‘seniority.’ ”). If Judge Widener’s approach were correct, an

employer could extend Section 703(h) immunity to any cri

terion simply by showing that it had previously entered into

discretionary employment decisions in some way.

25 Under Section 706(b) of Title VII (42 U.S.C. 2000e-

5(b) ), added in 1972, notification of a charge must be served

on the employer and union within 10 days of its receipt by

the EEOC. Before 1972, the EEOC was only required to serve

notice within a reasonable time. See Chromocraft Corp. V.

EEOC, 465 F.2d 745 (5th Cir. 1972).

26 Some expectations based on the lines of progression may,

of course, have arisen between the challenge and the con

clusion of the litigation. But this is an unavoidable risk ; until

the litigation runs its course, timely notification of the chal

lenge to the lines of progression is the only possible means of

preventing employees from acquiring unjustified expectations.

The Court has held that Congress relied on such notification

to ensure that litigation delays would not be unfair. See

Occidental Life Insurance Co. V. EEOC, 432 U.S. 355, 372-

373 (1977).

Moreover, Congress intended the EEOC to delay initiating

litigation until it had investigated the charge and attempted

conciliation. See Occidental Life Insurance Co. V. EEOC,

supra, 432 U.S. at 359-360, 368. Voluntary settlement and

conciliation are “the preferred means’’ of resolving employ

ment discrimination claims (Alexander v. Gardner-Denver

Co., 415 U.S. 36, 44 (1974); see Carson v. American Brands,

Inc., No. 79-1236 (Feb. 25, 1981), slip op. 8 n.14), and a

principal objective of Title VII is to “ ‘spur * * * employers

and unions to self-examine and to self-evaluate their employ

ment practices * * *.’ ” Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422

U.S. 405, 417-418 (1975), quoting United States V. N.L. Indus

tries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354, 379 (8th Cir. 1973). Had petitioners

done so, or had they been willing to conciliate with the

28

cidental Life Insurance Co. v. EEOC, 432 U.S. 355,

371-372 (1977).

In fact, when the lines of progression were estab

lished they interposed additional qualifications which

had to be met by employees seeking to use their sen

iority to obtain a better job. Before the lines were

instituted, employees with plant seniority could look

forward to obtaining one of the top jobs; when the

lines of progression were adopted, employees—black

and white alike—found that less senior employees

who had served in bottom jobs would obtain the top

jobs instead. In this way, the decision to adopt lines

of progression frustrated existing seniority expecta

tions. Respondents’ challenge to that decision ac

tually helped restore previously existing expectations.

Thus once respondents’ claim is seen as a challenge to

the adoption, not the operation, of the lines of

progression policy, there is no basis for suggesting

that it is inconsistent with the purpose of Section

703(h).

2. Petitioners assert (e.g., Union Br. 31; Com

pany Br. 30, 32) that unless Section 703(h) is inter

preted to permit them to reinstate the lines of pro

gression, their ability to determine who should be

respondents, no unwarranted expectations would have de

veloped.

In any event, the danger that employees acquired unwar

ranted expectations in the continued operation of petitioners’

lines of progression is far less than the danger that a seniority

system that is not bona fide will create such expectations,

since such a system may operate for years without being

challenged; yet Congress clearly intended to permit challenges

to aspects of seniority systems that were not bona fide. More

over, courts retain the power to shape seniority relief in a

way that avoids inequity. See Franks V. Bowman Transporta

tion Co., swpra, 424 U.S. at 770.

29

promoted—and otherwise to alter plant operations in

response to changing circumstances—will be exces

sively and unjustifiably restricted. But the courts be

low did not impose any extraordinary or unprece

dented limitation on petitioners.

Petitioners’ lines of progression policy specifies

that, as an additional prerequisite or qualification for

holding a “top” job, an employee must have held the

designated “bottom” job. The effect of denying peti

tioners the benefit of Section 703(h) was only to

require that they justify this policy in the same way

they would justify any other employment qualifica

tion—by showing, under Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

supra, 401 U.S. at 431, that that qualification is not

an “artificial, arbitrary, and unnecessary barrier []

to employment * * * which operates to exclude

[blacks and] cannot be shown to be related to job

performance.''

For example, in order to serve the same purposes

as the lines of progression policy, petitioners might

have specified that as a prerequisite to obtaining

certain jobs an employee must have experience in a

designated job outside the company, or must have

completed a training program, or must demonstrate

certain aptitudes, or must have a vocational school

diploma. All of these requirements would be subject

to Griggs. See, e.g., Pettway v. American Cast Iron

Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211, 221-222 (5th Cir. 1974)

(high school diploma); United States v. Hayes Inter

national Corp., 456 F.2d 112, 118 (5th Cir. 1972)

(prior experience). Petitioners do not explain why it

is unreasonable, or in conflict with a purpose of Title

VII or Section 703(h), to require the same justifica

tion for the employment qualifications established by

the lines of progression policy.

It is not a sufficient answer that the lines of pro

gression policy is an aspect of a seniority system.

eo

We can discern only two reasons Congress might have

had for requiring a weaker justification for an em

ployment practice that is an aspect of a seniority

system, and neither of those reasons is applicable

here.

First, as we have explained, Congress did not want

Title VII to “destroy or water down the vested sen

iority rights of employees simply because * * * [the]

seniority system * * * perpetuate [d] [past] discrimi

nation.” International Brotherhood of Teamsters v.

United States, supra, 431 U.S. at 353. Congress

may have been concerned about the employee who

worked for years in a bottom job with the expecta

tion that by doing so he would improve his chances

of obtaining a top job. But, as we have said, this

concern is not material here, for petitioners’ lines of

progression were challenged when they were adopted,

before any such expectations could develop.

The second possible reason for requiring a lesser

justification for an aspect of a seniority system is

that the seniority principle—That preferential treat

ment is dispensed on the basis of some measure of

time served in employment” (California Brewers As

sociation v. Bryant, supra, 444 U.S. at 606) and that

“longevity with an employer” is “reward [ed]” (Ala

bama Power Co. v. Davis, 431 U.S. 581, 589

(1977))—is of “overriding importance” in collective

bargaining and in the organization of the workplace.

Humphrey v. Moore, 375 U.S. 335, 346 (1964); see

Trans World Airlines, Inc. v. Hardison, 432 U.S. 63,

79 (1977); Aaron, Reflections on the Legal Nature

and Enforceability of Seniority Rights, 75 Harv. L.

Rev. 1532, 1534 (1962). In considering Title VII

and Section 703(h), Congress recognized that unions

almost universally use seniority to allocate scarce

benefits among their members. See, e.g., H.R. Rep.

31

No. 914, supra, at 71. The seniority principle is thus

often vital to a union’s efforts to aggregate and rec

oncile the conflicting interests of those it represents

(see, e.g., Cooper & Sobol, Seniority and Testing

Under Fair Employment Laws: A General Approach

to Objective Criteria of Hiring and Promotion, 82

Harv. L. Rev. 1598, 1604 (1969))—a central aspect

of a union’s role under the federal labor laws. See

Ford Motor Co. v. Huffman, 345 U.S. 330, 338-339

(1953).

Accordingly, Congress may well have believed

that to require a union to show that seniority serves

a business necessity would undermine one of the

central institutions of collective bargaining. Specifi

cally, the business necessity requirement is not

well suited to justifying the use of the seniority prin

ciple itself—that is, length of service—as a criterion.

See generally Jersey Central Power & Light Co. v.

Local 327, IBEW, 508 F.2d 687, 705-710 (3d Cir.

1975). The principal justification for using seniority

as a criterion lies in tradition, and in employees’ gen

eral willingness to accept it as a fair basis for allo

cating scarce benefits. See, e.g., Cooper & Sobol,

supra, 82 Harv. L. Rev. at 1604-1605.

This case, however, does not concern a union’s role

in reconciling employees’ conflicting interests by us

ing a measure that is generally accepted as legiti

mate; nor does it involve dispensing preferential

treatment “on the basis of * * * time served in em

ployment,” California Brewers Association v. Bryant,

supra, 444 U.S. at 606. The lines of progression are

a constraint that was imposed on the use of seniority

in order to serve management objectives. Petitioners

virtually concede as much, arguing that the “narrow-

ling]” of seniority by such means as the lines of

progression policy is needed to achieve management’s

32

goal of promoting the more qualified employees (see

Union Br. 30; Company Br. 28-29); it is in any

event obvious that any justification for the lines of

progression must invoke management’s needs for

qualified employees, not the union’s interests.

We know of nothing suggesting that Section 703(h)

was intended to allow a policy that limits the use

of seniority in order to serve the same management

objectives as other employment qualifications to be

justified more easily than other qualifications.27 In

deed, it is fair to say that in enacting Section 703(h)

Congress was almost exclusively concerned with the

importance of seniority to unions and employees, and

scarcely mentioned employers’ interests in incorporat

ing rules into seniority systems. See, e.g., 110 Cong.

Rec. 6549, 6553-6554, 11486, 11768, 11848 (1964);

H.R. Rep. No. 914, supra, at 71.

We recognize, of course, that “ [sjeniority systems,

reflecting as they do, not only the give and take of

27 The legislative history includes such statements as “noth

ing in the bill would affect any seniority plan which was not

a cloak for racial or religious discrimination” (110 Cong.

Rec. 5423 (1964) (remarks of Sen. Humphrey), quoted at

Union Br. 16), but it is clear that by “discrimination” the

proponents of the Act meant the sort of discrimination out

lawed by Griggs. For example, in the same speech in which

he made the statement just quoted, Senator Humphrey said

that the bill “does not limit the employer’s freedom to hire,

fire, promote, or demote for any reason * * *—so long as his

action is not based on race” (110 Cong. Rec. 5423 (1964)).

Indeed, the proponents of the Act often linked management

practices to seniority systems, explaining that both would be

unlawful if discriminatory and lawful if nondiscriminatory.

See, e.g., 110 Cong. Rec. 5094 (1964) (“An employer will re

main wholly free to hire on the basis of his needs and of the

job candidate’s qualifications. What is prohibited is the re

fusal to hire someone because of his race or religion. Simi

larly, the law will have no effect on union seniority rights.”) .

33

free collective bargaining, but also the specific char

acteristics of a particular business or industry, in

evitably come in all sizes and shapes,” and that

“ [significant freedom must be afforded employers

and unions to create differing seniority systems”

(California Brewers Association v. Bryant, 444 U.S.

598, 608 (1980)). When employees have developed

expectations based on “those components of [a] * * *

seniority scheme that, viewed in isolation, [do not]

embody or effectuate the principle that length of em

ployment will be rewarded,” there is good reason to

“exempt [those components] from the normal opera

tion of Title VII * * Id. at 607. Thus to the

extent that petitioners’ lines of progression are bona

fide, and are an aspect of their seniority system,

the “routine application” (International Brotherhood

of Teamsters v. United States, swpra, 431 U.S. at

352) of the lines of progression will be protected by

Section 703(h), because those lines of progression

may have given rise to employees’ expectations. More

over, even when the adoption of a seniority system

is challenged, there may be aspects of the system—

notably the very use of the seniority principle—to

which it would be inappropriate to apply the “busi

ness necessity” requirement as it has been developed

in other contexts.

Here, however, respondents have challenged the

adoption of an aspect of a seniority system that re

sembles any other job qualification and that gave rise

to no legitimate expectations. If the six challenged

lines of progression are “related to job performance”

('Griggs v. Duke Power Co., supra, 401 U.S. at 431),

petitioners should be able to show that they are—just

as they were able to show that the other three lines

served a business necessity (App. 31-32). See Furnco

34

Construction Corp. v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567, 577

(1978). But there is no reason to allow employees

and unions to adopt “artificial, arbitrary, and un

necessary barriers to employment” (Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., supra, 401 U.S. at 431) merely because

those barriers “have some nexus to an arrangement

that concededly operates on the basis of seniority”

0California Brewers Association v. Bryant, supra,

444 U.S. at 608).

3. Petitioners (e.g., Union Br. 28-31; Company

Br. 27-31) and amicus (Am. Br. 15, 20 n.18)28 also

argue that unless the lines of progression are im

munized from Title VII, employers and unions will

be unable to adopt any change in their seniority prac

tices, even a change that would favor minorities, for