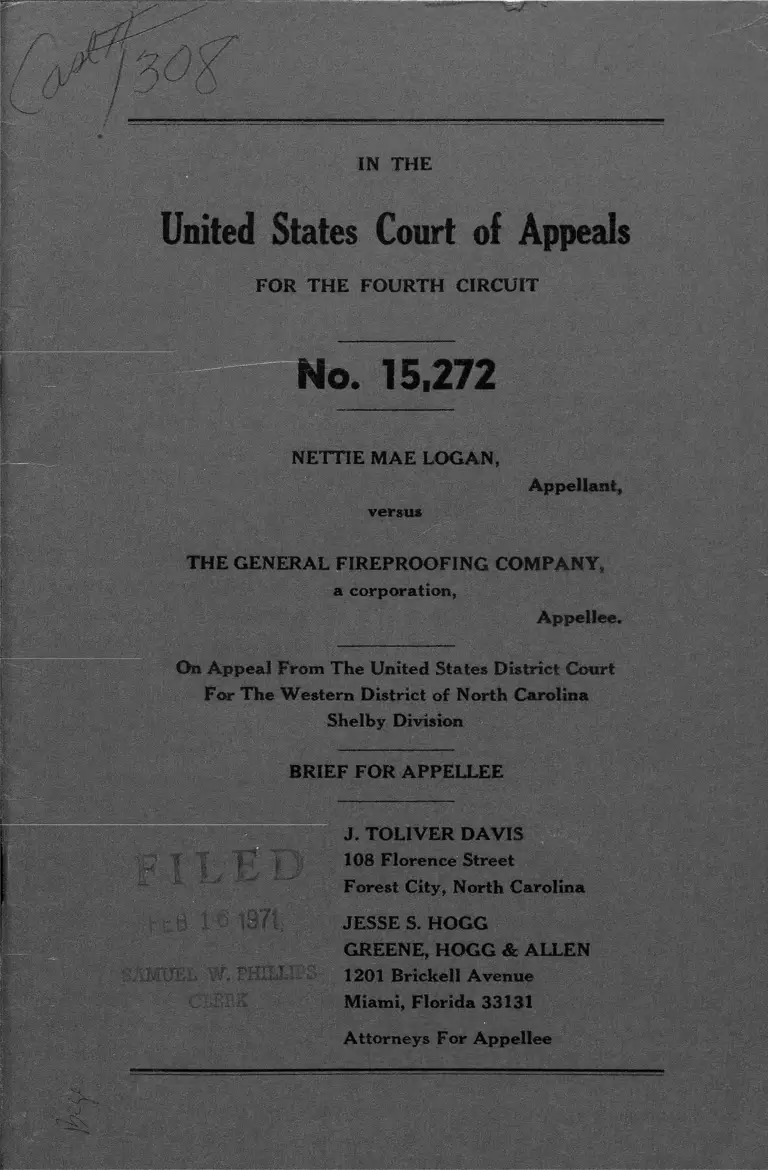

Logan v. The General Fireproofing Company Brief for Appellee

Public Court Documents

February 16, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Logan v. The General Fireproofing Company Brief for Appellee, 1971. aafd4785-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f493a41e-a321-4ad2-a040-5b0244745953/logan-v-the-general-fireproofing-company-brief-for-appellee. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 15.272

NETTIE MAE LOGAN,

Appellant,

versus

THE GENERAL FIREPROOFING COMPANY,

a corporation,

Appellee.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Western District of North Carolina

Shelby Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE

J. TOLIVER DAVIS

108 Florence Street

Forest City, North Carolina

JESSE S. HOGG

GREENE, HOGG & ALLEN

1201 Brickell Avenue

Miami, Florida 33131

Attorneys For Appellee

INDEX

Page

COUNTERSTATEMENT OF THE CASE ............... 1

1. Manifest Errors in Appellant’s Statement . . 1

2. Additional Relevant Facts .......................... 8

ARGUMENT

1. The United States Supreme Court Has

Not Established Extraordinary Stand

ards For Summary Judgments In Title

VII Cases, But Has Confirmed That

Ordinary Standards Are To Apply, And

Judicial Experience Has Confirmed That

Relief By Way of Summary Judgment

Is Peculiarly Appropriate To These

Cases, Because A Standard Practice Has

Arisen Whereby Individual Plaintiffs Al

most Always Bring Broad Class Actions,

Even When They Are In Truth Aware

Of No Class Discrimination; These Ac

tions Should Not Be Allowed To Proceed

If The Plaintiff, Given Ample Opportun

ity Through Discovery And Independent

Means, Cannot Show The Existence Of

A Real Issue ..................................................14

2. The Plaintiff And The E.E.O.C. Have

Resorted To Demonstrably Invalid Sta

tistical Methods In Interpreting The Sta

tistical Data In The Record, And The

Correct Application Of Valid Methods

Yields Conclusions Which Amply Sup

port The Summary Judgment Under Re

view ..................................................................20

INDEX (Continued)

II

Page

3. Where The Evidence Supports The Gen

eral Proposition That An Employer’s

Hiring and Internal Practices Are Non-

Racial, The Absence Of Negroes, In Ex

ecutive, Professional And Technical Po

sitions In A Relatively Small Plant In

Rural North Carolina Cannot Give Rise

To An Inference Of Discrimination, Es

pecially Where Such Absence Is Cogent

ly Explained By Sworn And Undisputed

Testimony......................................................... 27

4. Defendant Was Entitled To Summary

Judgment As To Individual Claim Of

Discriminatory Refusal To Hire, Where

Evidence Showed That Defendant’s Hir

ing And Internal Practices Were Non-

racial, Where Plaintiff Was Admittedly

Grossly Overweight And Unskilled,

Where Plaintiff Admitted Falsifying

Her Application, Admitted She Had Err

ed In Her Complaint Allegations, Adopt

ed Factual Information Which Contro

verted All But One Of Her Essential

Allegations, And Where The Remaining

Discrepancy Between Her Evidence And

The Defendant’s Created An Issue Which

Was Not Material ......................................... 38

5. Where There Was No Evidence That The

Defendant Had At Any Time Engaged In

R a c i a l l y Discriminatory Practices,

Plaintiff’s Invoking of 42 U.S.C. §1981 Did

Ill

INDEX (Continued)

Page

Not Render The Case Any Less Suitable

for Summary Judgment ................................ 46

CONCLUSION ............................................................... 46

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ................................... 47

AUTHORITIES

CASES:

Adickes v. S. H. Kress & Co., 1970, 398 U.S.

144, 90 S.Ct. 1598, 26 L.Ed. 2d 142 . . . . 14, 15, 16, 17

Clark v. American Marine Corporation, DC La

1969, 304 F. Supp. 603 2 FEP Oases 198 ........ 33

Dobbins v. Local 212, I.B.E.W., SD Ohio 1968,

292 F. Supp. 413 ............................................... 29, 30

Johnson v. Louisiana State Employment Service,

Inc., DC La. 1968, 301 F. Supp. 675 ............... 31, 35

Labit v. Carey Salt Co., 5 Cir. 1970, 421 F.2d 1333 . . . . 44

Lea v. Gone Mills, DCNC 1969, 300 F. Supp. 97 . . . . 28, 32

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Service,

Inc., DC La 1968, 301 F. Supp. 675 ............... 21, 31

Phoenix Savings & Loan, Inc. v. Aetna Casualty

& Sur Co., 4 Cir. 1967, 381 F.2d 245 ................... 17

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 5 Cir. 1970, 431

r .2d 1094 ................................................................ 46

Sexton v. Training Corp. of America, DC Mo.,

1970, ___F.Supp____ , 2 FEP Cases 682 ............ 45

AUTHORITIES (Continued)

U.S. v. Dillon Supply Co., 4 Cir. 1970, 429 F.2d

IV

Page

800 ........................................................................... 30

U. S. v. Hayes International Corporation, 5 Cir.

1969, 415 E.2d 1038, 2 FEP Cases 67 ................... 33

U.S. v. Sheet Metal Workers International Assn.,

Local 36, 8 Cir. 1969, 416 F.2d 123 ................... 32

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works, 7 Cir. 1970,

301 F.Supp. 663 ...................................................... 46

Williams v. Howard Johnson’s, Inc., 4 Cir. 1963,

323 F.2d 102, 105 ............................................... 18, 44

Miscellaneous:

1936 Literary Digest ........................................... 23, 24

6 Moore, Federal Practice 56.22 2, at 2824-2825

(2d. Ed. 1966) ...................................................... 16

Weinberg & Schumaker, Statistics: An Intuitive

Approach, 2d Ed. (Belmont, Calif., Wads

worth Publishing Co., Inc., 1969) .......... ........... 21

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 15,272

NETTIE MAE LOGAN,

Appellant,

versus

THE GENERAL FIREPROOFING COMPANY,

a corporation,

Appellee.

On Appeal From The United States District Court For

The Western District of North Carolina

Shelby Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE

COUNTERSTATEMENT OF THE CASE

1. Manifest Errors In Appellant’s Statement

The Appellant’s Statement of the Case1 Contains

numerous erroneous assertions of fact.

Hn this brief, the Appellant’s Brief will be desgnated “P.B.” ; the

Appellant will be referred to as the Plaintiff, and the Appellee

as the Defendant; the Appendix will be designated “A.” ; and

the Plaintiffs’s Deposition will be designated “P.D.” The amicus

curiae brief of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

will be designated “ C.B.”

2

At page 15 of the Appellant’s Brief, it is asserted,

without benefit of any citation, that 9% of the Defend

ant’s employees are black, as contrasted with an 18%

black population in Forest City. The City and County

Data Book, United States Census of Population, De

partment of Census, Table 22,2 gives the non-white fig

ure for Forest City as being 16.9%. Moreover, Table

28 shows that the black population percentage in the

county (Rutherford) where the plant is located is only

11.9%.3 We take it that no one will deny the proposition

that, if any figure is relevant, it is the county figure

and not the city figure. While the point is not expressly

taken up in the Defendant’s affidavits, it is incidentally

shown that the Defendant does not restrict employ

ment to residents of the small town of Forest City.

The description of the employment procedure, as given

by the personnel clerk and by both present and form

er personnel managers (A. 83, 87, 93), fully describes

the procedure and there is no mention of such a strange

limitation. On the contrary, these affidavits uniformly

show that the procedure is to accept applications from

all persons who appear and desire to apply, and the

only general qualification is that the applicant be 18

years of age and be able to read and write (A. 88).

The Plaintiff herself resides in Bostic, North Carolina,

5-1/2 to 6 miles from the plant (P.D. 51, A. 170), and

her application was accepted (A. 2). The personnel

2We presume that this Court will take judicial notice of the figures

appearing in the Census Report, as did the court in Parham

v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 8 Cir. 1970, ______.

F .2d_____

sThe plant property lies partially within and partially outside the

city limits.

3

manager lives at Spindale, North Carolina (A. 93), and

the personnel clerk at a rural address out of Forest

City (A. 83).

The Data Book, in Table 28, further shows that there

were 39,691 whites and 5391 non-whites in the county

as of the time of census, or a total of 45,082 persons.

In order to obtain a figure that would be meaningful

in terms of employment, it is further necessary to elim

inate those persons who were under 18 years of age,

or over 65. Table 27 shows that 14,094 whites were un

der 18, and 3571 were over 65, and that 3570 non-whites

were under 18, and 360 were over 65. Thus, there were

20,595 unemployables in the total figure, and 24,487 em

ployables. Dividing 24,487 into (5391-2930) it appears

that the percentage of non-whites in the employable

population of Rutherford County as of the time of cen

sus was almost exactly 10%.

The sworn answers to interrogatories filed by the

Defendant in this case show that the percentage of

blacks in the production work force is about 9.6% (41

out of 425)4 which is closer to 10% than to the 9% figure

stated by the Plaintiff.

Also, at page 15, the Appellant’s Brief states that

58% of black promotions and 31% of white promotions

have occurred since suit was filed in March, 1968, al

though it is plain in the record that suit was filed in

March, 1969, and not in 1968 (A. 1).

^The figure of 524 referred to in the E.E.O.C.’s brief (C.B. 5)

was a transpositional error.

4

The statistics that the Plaintiff cites, consisting of

Defendant’s answers to interrogatories 8 and 9 (A. 60-

80), actually reflect that the Defendant’s employees

on hand as of the time of answering had received a

total of 325 promotions. The 384 white employees had

received a total of 292 promotions, or a statistical aver

age of .76 per white employee. The 41 negro employ

ees had received a total of 33 promotions, or a statis

tical average of .89 per negro employee, demonstrat

ing that the negro employees actually were promoted

slightly more frequently than the whites.

The Plaintiff’s assertion (P.B. 15) that 58% of all

black male promotions occurred after suit was filed,

as compared with 31% of all white male promotions

is, of course, erroneous. First, the actual number of

black males listed in A. 60-80 who received promotions

after the correct date of suit, March 18, 1969, is 10

rather than 14, so that the percentage would be 41%

rather than 58%. Second, the data at A. 60-80 speaks

only with regard to employees on the payroll as of

the time of answering (A. 33-44, Interrogatories 8 and

9). There is no evidence whatever to show how promo

tions were distributed among blacks, whites, males

or females during 1963-1969. As of the time of answer

ing, the Defendant had from time to time employed

approximately 3000 persons other than those then on

the payroll (A. 45, Answer to Interrogatory No. 10).

It is also shown that it is not possible to determine

how promotions were actually distributed during the

six years in question among the more than 3400 em

ployees who are or have been in Defendant’s employ,

5

because the Defendant’s records do not identify ter

minated employees by race, and it does not otherwise

have this information (A. 45, last sentence, Answer

No. 10).

The Plaintiff next asserts that the Defendant has

two black supervisors whereas the information relied

upon states clearly that there are three, who' are Hor

ace Gerald Thompson, James Twitty and Richard Wil-

kerson (A. 45-46, Answer No. 11). Having gotten the

date of suit and the number of black supervisors

wrong, the Plaintiff next combines these errors to pro

duce a third erroneous assertion, that 100% of the De

fendant’s black supervisors were made supervisors af

ter suit was filed. The answers clearly show that two

of the three were made supervisors before March 18,

j(J 1969, and that Thompson has been a departmental fore

man since 1966.

Continuing, the Plaintiff erroneously asserts that the

blacks supervise a total of 12 men (P.B. 15). The an

swers to interrogatories (Answer 11, A. 45-46) show

clearly that Thompson supervises 12 men on the day

shift and Twitty supervises 3 others on the second shift,

Wilkerson being Thompson’s assistant foreman.

It is, of course, absurd to say, as the Plaintiff next

does (P.B. 16), that the white supervisors supervise

a total of 1692 men. The data cited shows clearly that

each department has from one to five supervisors, and

the Plaintiffs attorneys must surely realize that a de

partmental foreman and his assistant or assistants us

ually supervise the same people (A. 46-47, Answer No.

6

12). For instance, Billy Scruggs and his 16 employees

in Department A constitute the 17 employees super

vised by Fred McDowell in Department A. The em

ployees are all named in Answers 8 and 9, and the

total is 425.

/ 3 )/

Still further, the compilation does not, as the Plain

tiff asserts (A.B. 16), show that the only men ever

hired to fill janitorial positions were black. Again, the

3000 terminated employees have not been taken into

account. The compilation only shows, and can only

show, that 4 of the 41 negroes working at the time

of answering were originally hired as janitors, as well

as one white woman (A. 61). The four negroes have

all been promoted to other jobs, and the plant now

has its janitorial work done by a contractor (A. 48,

Answer No. 15). The elimination of the janitorial jobs

occurred long before this suit was filed.

The Plaintiff next makes a number of comparisons

between male and female employees (Second full para

graph P.B. 16 through first full paragraph P.B. 17).

A Defendant has not checked these comparisons for

j } j accuracy because they are all irrelevant to this case.

The Complaint sets forth no allegation of sex discrim

ination, but limits itself to a claim of racial discrimina

tion, both as to the Plaintiff and as to the class she

represents. She asks that the Defendant be enjoined

from “discriminating against Plaintiff and other Ne

gro persons in this class because of race or color”

(A. 2, 5). Indeed, the Plaintiff’s contention was that

the Defendant hired a number of white women while

/W denying her employment (P.D. 16, lines 17-22, A. 135).

7

The Plaintiff next asserts that the Defendant em

ploys 19 women who are “overweight”, weighing 150

pounds or more. The arbitrary assumption that 150

pounds is the dividing line for overweight women is

not supported, and the correct figure appears to be

18, both from the names in footnote 12 of the Plaintiff’s

brief, and from the data (A. 60-64). None of the 18

was as heavy as the 180 pounds that the Plaintiff listed

on her employment application (A. 177) and the Plain

tiff falsified the application, at least as to her height.3

While it may be true, as the Plaintiff states, that

a substantial number of the female employees have

more than 4 children, none has as many as the Plain

tiff, except for D. R. Thompson, who is a negro and

who was given special consideration because her hus

band worked at the plant (A. 86). Since the female

employee with the largest number of children, and oth

ers with four or more (E. M. Washburn, S. C. Church)

are negroes, the statistics will not support any claim

that any principle concerning children is applied in

a racially discriminatory manner. The ratio- of negro

females with 4 or more children to white females with

sThe application (A. 177) gives her weight as 180 lbs and her

height as 5’6” . She testified on deposition that she weighed

205 lbs and stood approximately 5’4” . She pleaded lack of

memory as to whether she had gained 25 lbs. or any weight at

all, since applying for employment. While it may be possible

that she gained the weight, it is certainly unbelievable that

she gained the 25 lbs. without knowing that she has gained

at all, and we may surely rest assured that she has not shrunk

two inches in height. She obviously falsified her application be

cause she knew that nobody would hire a 5’4” , 205 lb. woman

to do factory work, and nobody did until Burlington Industries

put her on the payroll rather than face litigation (A. 165, 172-

174, 178).

8

4 or more children (3 or 12% to 22 or 88%) of course

compares favorably with the ratio of employable ne

groes to employable whites in the county (1 to 9) or

even to the raw percentage of negroes in the county

(11.9%).

It is not accurate to say that the Defendant conducts

on the job training programs ait its plant (A.B. 18).

On the contrary, the plant does not advertise for train

ees or unskilled employees (A. 93), and the applicant

must be qualified for the job available unless the job

is that of unskilled laborer (A. 94). The company has

occasionally permitted prospective employees to learn

sewing on their own time, not on the job, with super

visory assistance, and has taught some limited weld

ing on a sporadic basis (A. 44, Answer 7). There was

no opportunity for the Plaintiff to be advised of because

she was otherwise disqualified, first on account of her

obesity and secondly on account of her 9 children at

home.

In summary, the Plaintiff’s Statement of the Case

is grossly in error, and is so with regard to almost

every significant point it mentions. The Defendant sub

mits that the Statement is so inaccurate as to be vir

tually worthless.

2» Additional Relevant Facts

The Plaintiff testified on deposition that she heard

a radio announcement, definitely in December of 1965,

that the Defendant wanted some trainees (A. 122). She

also testified that she had at some time seen an ad

in the Forest City Courier to the same effect, but that

9

she didn’t know when that was (A. 139). The Defend

ant’s past and present personnel managers both testi

fied that the Defendant did not, at any time, do any

recruiting, or advertise in newspapers or by radio

or television for any trainees or unskilled employ

ees, because there had always been an abundance

of walk-in applications (A. 87, 93). The same informa

tion appears in the answers to interrogatories (A. 48,

Answer 18). The present personnel manager further

affirms from a record search that no such ads have

been placed (A. 93). The plaintiff has failed to have

the E.E.O.C. “Memorandum for the File” (A. 25) re

produced in the Appendix, but it is a part of the Court’s

record, the Plaintiff has adopted it as being correct

(A. 25), and it contains the statement: “There was no

evidence to show that the Respondent company placed

an ad in the newspaper seeking employees.”6

6The E.E.O.C. nevertheless founded its “ reasonable cause” deter

mination as follows: “The Charging Party filed an application

with Respondent Company on December 27, 1965, and was in

formed by the personnel manager that there were no openings.

Two days later Respondent Company placed an ad in the paper

indicating that it was desirous of ’ hiring trainees for employ

ment.” (A. 103) The “Memorandum for the File” also takes pains

to point out that “The documentation obtained in this investi

gation shows that the Charging Party made application for em

ployment with the Respondent on March 16, 1966, rather than

December 27, 1965, as shown on the Commissioner’s Summary

of Investigation.” The Commission’s decision further stated that

“Respondent has assumed that Negro women have more chil

dren than white women.” (A. 103), and reasoned that this ad

mission by Defendant would support an inference of discrimi

natory intent. The “Memorandum for the File” says: “ In inter

view with the Respondent, the assumption that Negro women

had more children than white women was never discussed.”

Since the E.E.O.C. has been granted leave to participate in oral

argument, it will doubtless explain these matters to the Court

at that time.

The Plaintiff claims that the Defendant was engag

ing in discriminatory hiring practices as of the time

when she applied for a job in March of 1966. It is im

possible to determine exactly how many negroes or

whites were hired during March, 1966, or during the

entire year of 1966, since the Defendant has no records

showing the applicants for that year by race (A. 49,

Answer 28(a) ), showing terminated employees by

race (A. 45, Answer 10, last sentence), or identifying

employees referred by employment agencies and hired

or not hired, by race (A. 49, Answers 21, 22).

However, the roster of employees on hand as of the

time of answering interrogatories shows that none

were hired during March, 1966; that 17.3% (9 of 52)

of all current employees hired during the entire year

of 1966 were black; that 8.7% (2 of 23) of the females

were black; and that 22.6% (7 of 31) of the males were

black (A. 60-80). These percentages, of course, com

pare most favorably to the figure of 10%, representing

negroes available for employment in Rutherford Coun

ty-

The E.E.O.C..concedes that the Defendant pays ne

groes and whites the same pay for the same work,

and that negroes are not excluded from any jobs (C.B.

7).

The Defendant’s past and present personnel man

agers and its personnel clerk testified that no negro

had ever applied for an executive position at the plant;

that only a few had applied for clerical positions, and

that a few had been hired in clerical positions and

11

others actively sought; that negroes with needed skills

apparently did not exist in substantial numbers in the

Rutherford County area, because few had applied; that

no negro had ever applied for or claimed to have the

skills used in the maintenance department; that the

E.E.O.C. poster had been posted at all times, barring

times when it was temporarily defaced or torn down

by unknown persons; and, generally, that the plant

had never taken any personnel action of any kind on

account of racial considerations (A. 88, 89, 91, 94, 95,

96, 98, 99). The present personnel manager testified

that he had long made a special effort, at the Defend

ant’s request, to get more negroes in clerical positions,

but that negroes with such skills were scarce in the

area, so that he had eventually initiated correspond

ence with a negro girl from the area but working away,

with no success (A. 96).

The Plaintiff, on the other hand, testified affirma-

/). tively that she had no knowledge whatever concerning

the Defendant’s internal employment practices, as to

any of the matters mentioned in the Complaint (A.

139-143). In opposition to the Defendant’s motion for

summary judgment, the Plaintiff was unable to come

forward with evidence of any specific fact, as required

£}J°y Rule 56(e), creating an issue as to any of the facts

asserted and supported by Defendant. Aside from re

iterating the facts shown in her employment applica

tion, stating that her husband was retired and avail

able to care for her 9 children, and saying that she

has to stand on her feet in her job at Burlington, her

opposing affidavit merely says that she gave her at

torney, but not the trial court, the names of some ne*

zo

12

groes who, she “believed”, had sought employment

and not been hired. The Plaintiff submitted no other

evidence of any kind.

The Plaintiff herself is currently 67 to 97 pounds over

weight according to tables prepared by the Metropoli

tan Life Insurance Co. from data of the Build and Blood

Pressure Study, 1959, Society of Actuaries, and she

has no skills (A. 134).

Other pertinent aspects of the statistics are: The De

fendant has employed negro females in a variety of

clerical positions, including Traffic Clerk, Processing-

Customer Service Clerk, Accounts Payable Clerk, and

Key Punch Operator (A. 48, Answer 14). INTegroes have

been employed in every production department except

one, and, on the basis of the recollection of the per

sonnel manager and clerk, in all of the classifications

in those departments (A. 48, Answer 15).

Negro female J. G. Miller earns more than white

female B. K. Roane, for the same job, and was promot

ed much more quickly (A. 62-63). Miller is paid more

than any of the white women except one, P. J. Upton

(A. 63). Negro employee R. L. Miller, III, (A. 75) has

had three promotions and now earns more than white

employees J. A. Higgins and A. L. Rhodes, (A. 68)

who are in the same classification and who were hired

before Miller. Negro employee E. C. Ledbetter has

been promoted twice in little over a year and now earns

one of the better rates in the plant (A. 76). Negro disc

grinder D. Toms (A. 77) has been promoted once and

earns more than white disc grinder J. B. Beaver (A.

13

71), although he has less service. Negro disc grinder

F. L. Thompson, Jr., and Beaver were hired and pro

moted within 4 days of each other, and they earn the

same (A. 71). Thompson only worked a month before

being promoted. Negro employee H. Logan was pro

moted in one step from helper to heat treat operator,

and he earns within one cent of the top rate in the

plant (A. 77). Negro employee J. E. Smith was promot

ed after twio months, with a $.21 raise in apparent

preference to white employee J. R. Shaw, hired at the

same time and in a similar job (A. 72).

There are 17 negroes who have not been promoted.

Eight of these and 86 white employees who have not

been promoted either, are in the simple laboring class

ifications (A. 60-64). The ratio of unpromoted negroes to

unpromoted whites here is approximately 1 to 10, the

same as the ratio of employable negroes to employ

able whites in the county. Of the remaining 9 negroes

who had not been promoted as of the date of the an

swers, 3 were in a group of 36 employees hired since

August 1, 1969, containing 4 negroes and 32 whites,

from which 1 negro and 1 white had been promoted.

The other 6 unpromoted negroes are assemblers or

utility workers, and they compare to 63 unpromoted

whites (not counting the laboring jobs in A. 60-64 or

persons hired after August 1, 1969), Again, the approxi

mate 1 to 10 ratio holds true. It would be a herculean

task to compute the average waiting time between ap̂

plication and employment, but negro waiting periods

ranged from one day (G. W. Mills. A. 78) to a rare

time of nine months (E. M. Washburn, A. 61), while

14

white waiting periods have run much longer, such as

nineteen months in the case of M. J. Hamrick (A. 60).

ARGUMENT

1. The United States Supreme Court Has Not Estab

lished Extraordinary Standards For Summary

Judgments In Title VII Cases, But Has Confirmed

That Ordinary Standards Are To Apply, And Judi

cial Experience Has Confirmed That Relief By

W ay of Summary Judgment Is Peculiarly Appro

priate To These Cases, Because A Standard Prac

tice Has Arisen Whereby Individual Plaintiffs Al

most Always Bring Broad Class Actions, Even

When They Are In Truth Aware Of No Class Dis

crimination; These Actions Should Not Be Allow

ed To Proceed If The Plaintiff, Given Ample Op

portunity Through Discovery And Independent

Means, Cannot Show The Existence Of A Real

Issue.

><

The Plaintiff appears (P.B. 20) to concede that the

summary judgment procedure is appropriate in Title

VII cases, but the E.E.O.C. takes another stance, argu

ing that the procedurejs inappropriate (C.B. 11). The

cases cited do not so hold.

The E.E.O.C.’s statement (C.B. 8) that Adickes v.

S. H. Kress & Co., 1970, 398 U.S. 144, 90 S.Ct. 1598,

26 L. Ed. 2d 142, “established an extremely high stan

dard, for the grant of summary judgment. . . . in a

civil rights case” is a gross misrepresentation, and

it is wholly incompatible with the Commission’s sub-

15

sequent (C.B. 9) concession that Adickes merely re

stated the general rule governing summary judg

ments.

Adickes, which arose under a different statute, was

a case in which the Supreme Court reversed the Second

Circuit as to the propriety of a summary judgment

disposing of a two-count complaint, the Supreme Court

finding that the Second Circuit had erroneously inter

preted the substantive law as to one count, and erred

as to the nature of evidence necessary to support a

conspiracy claim as to the other count.

Far from setting any new standards for summary

judgment, the Supreme Court, in the majority opinion,

merely stated that summary judgment “was improper

here, for we think respondent failed to carry its burden

-of showing the absence of any genuine issue of fact.”

(26 L.Ed. 2d at 152). The Court affirmatively stated

that the movant’s burden is simply that of “showing

the absence of a genuine issue as to any material fact” ,

as in the usual case (26 L.Ed. 2d at 154). The Court

affirmed that Rule 56(e) means precisely what it says, .

that one opposing summary judgment cannot rest on

pleadings once the pleadings are controverted by af

fidavits, but held merely, that.the.burden does not shift Yv

to the opponent until the movant does in fact submit 5 ’

some evidence to controvert the opponent’s pleadings)

(26 L. Ed. 2d 155-156). The Adickes defendant’s affi- 1̂1..

davits had not fairly met the substance of the com

plaint. Considering the E.E.O.C.’s bland assertion as

to an “extremely high standard”, we are pleased to

note that the Supreme Court expressly .used the phrase

“ordinary standards applicable for summary judg

ment” in referring to the status of summary judgment

procedures, in civil rights cases or other cases, after

the 1963 amendments to the rules of procedure (26 L.

Ed. 2d at 155). The Court quoted the usual and ordinary

rule, as set forth in 6 Moore, Federal Practice jj56.22

[2], at 2824-2825 (2d. Ed. 1966), as being applicable

to civil rights cases, and that rule merely states that

the moving piarty is entitled to summary judgment if

he shows entitlement “under established principles”.

Although the case contained three minority opinions,

there is nothing in any of them to say, indicate or imply

that civil rights cases are due any special considera

tion in summary judgment proceedings. Mr. Justice

Black, concurring, quoted Rule 56(c) verbatim and left

it at that, although he said that a trial court ought

to permit cases to go to a jury, in jury cases, where

the facts will support different inferences. We take it

that the converse is indicated where the court, as here,

sits as finder of the facts.

Mr. Justice Douglas, dissenting in part, didn’t even

mention any summary judgment standards, apparent

l y assuming that ordinary standards apply, and the

same is true of Mr. Justice Brennan, who concurred

in part and dissented in part.

In view of the Supreme Court’s clear and careful

adherence to ordinary summary judgment concepts

in Adickes, we think it offensive for the E.E.O.C. to

otherwise represent that case to this Court.

17

Although the Adickes case, emanating from the Su

preme Court, sufficiently disposes of the Commission’s

contention, we note that none of the other cases cited

by the Commission purports to establish any new sum

mary judgment standards for civil rights cases.

Phoenix Savings & Loan, Inc. v. Aetna Casualty &

Sur. Co., 4 Cir. 1967, 381 F.2d 245, when it says that

the affidavits and other evidence must show that the

adverse party cannot prevail “under any circum

stances" quite obviously does not mean that the ad- | A

verse party need not show the existence of a material *

issue during summary judgment proceedings. This

Court, rather, was referring to the question whether

the facts could give rise to conflicting material infer

ences, as demonstrated by its further statement that

the issue was whether “there are ... genuine1 issues

°f or conflicting inferences deductible therefrom

• • •”> or whether “reasonable men might reach dif

ferent conclusions” from the facts (381 F.2d at 249).

It is clear that an adverse party cannot avoid sum

mary judgment merely by asserting that she can later

show circumstances supporting her claim:

• • • summary judgment cannot be prevented

merely by the claimed existence of a genuine

issue of material fact.” (L & E Co. v. U.S.A.,

Cal. Cir. 1965, 351 F.2d 880).

As another court has put it:

“The whole purpose of summary judgment

* 4

Of ^

18

procedures would be defeated if a case could

be forced to trial by mere assertions that a

genuine issue exists without any showing of

evidence”. (Winton v. Tempus Corp., DC

Tenn. 1968, 389 F. Supp. 863).

r

The fact that some circumstances justifying relief

for the Plaintiff could possibly exist is of no moment

in the absence of evidence:

“Intangible speculation does not raise an issue

of material fact.” (U.S. v. Mt. Vernon Mill Co.,

Ind. Cir. 1965, 345 F.2d 404).

“A party is not entitled to denial of a motion for

summary judgment on the basis of mere hope

that evidence to support his claims will de

velop at trial.” (Taylor v. Rederi A/S Volo, Pa.

Cir. 1967, 374 F.2d 545).

In consonance with this Court’s adjuration in Will

iams v. Howard Johnson’s, Inc., 4 Cir. 1963, 323 F.2d

102, 105, that summary judgment principles are to be

applied in a realistic and common sense manner, it

is also sound to say that an adverse party ought not

be able to avoid summary judgment by averring that

she has communicated some secret information to her

lawyer:

“. . . if a motion for summary judgment is to

have any office whatever, it is to put an end to

such frivolous, possibilities when they are the

19

only answer,” (L. Hand, J., in Deluca v. Atlan

tic Refining Co., 2 Cir. 1949, 176 F.2d 421).

As to the standard argument that civil rights cases i/f/ /

are important and that the courts ought to be careful

in granting summary judgments, we would merely re- K

ply that the courts are presumed to be careful in all i y

cases. '

As to the Commission’s assertion that the summary

judgment procedure is “inappropriate” in civil rights

cases, the cases, including those from the Supreme

Court, simply deny it, and experience teaches the con

trary. It is a matter of common knowledge that indi

vidual Title VII claims are consistently being used as

vehicles for the broadest possible class action suits,

and often in circumstances where the Plaintiff, as

here, has no case and possesses no evidence whatever

of class discrimination. If the E.E.O.C. has generally

been as unprofessional in rendering “reasonable cause”

decisions as it is shown to have been in this case,7 one

is warranted in concluding that Title VII has given rise

to a great deal of spurious litigation of a kind which is

most onerous and time consuming for the courts as

7The most casual comparison between the E.E.O.C.’s Decision (A.

102) and its Memorandum for the File (omitted from the Ap

pendix by Plaintiff, but attached to the Plaintiff’s Statement

of Sept. 24, 1969, in the record) shows glaring discrepancies

between the facts found during the investigation and the facts

recited in the Decision. The Decision states, and the Memoran

dum denies, that Defendant told Plaintiff it had no openings

at a time when it was advertising in the newspapers for

trainees; and that the Defendant admitted to an assumption

that negro women have more children than white women.

20

well as for defendants. When a plaintiff, as here, has

been given the full benefit of discovery, has had nearly

a year to scrape up independent evidence, and still can

not produce a single witness to substantiate any of her

charges, we submit that summary judgment is an

eminently appropriate method of concluding the case.

2. The Plaintiff And The E.E.O.C. Have Resorted To

Demonstrably Invalid Statistical M ethods In In

terpreting The Statistical Data In The Record, And

The Correct Application O f Valid Methods Yields

Conclusions Which Amply Support The Summary

Judgment Under Review.

The Plaintiff and the E.E.O.C., in regard to the

Plaintiffs class action, have almost completely aban

doned any contention that the Defendant has unlaw

fully discriminated against negroes except with regard

to hiring. The E.E.O.C. candidly admits the absence

of internal discrimination (C.B. 7) and only argues that

a statistical imbalance in the work force justifies an

inference that discrimination in hiring has occurred

and been perpetuated by the Defendant’s practice of

“walk-in” hiring. The Plaintiff makes the same argu

ment as to a statistical imbalance and perpetuation,

and she further contends that all black employees were

in the lowest paying jobs prior to suit, and that the

black supervisors were promoted, but only after suit

was filed (P.B. 27).

Since the Plaintiff had the date of suit wrong, and

since two of the three black supervisors were promoted

21

prior to suit, as shown in the Counterstatement, we

take it that the Plaintiff’s contention as to the super

visors may be dispensed with.

Since the data shows clearly that every one of the

black women was hired at exactly the same wage paid

to white women, and in the same jobs (A. 60-64), and H~r

since the same is true of the black men (A. 65-80),

the Defendant will rely upon the data as showing1 that

blacks have not been confined to the lowest paid jobs.8

When the Plaintiff’s obvious mistakes are recognized

and the assertions based upon them eliminated, then,

the only viable issue is whether the statistical data

contained in the record will support the inferences

claimed by the Plaintiff and the E.E.O.C.

The Defendant agrees with the Eighth Circuit Court

of Appeals, the Plaintiff and the E.E.O.C. that “statis-

tics often tell much and courts (should) listen” (Par

ham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 1970, 301

F.Supp. 675, 2 FEP Cases 1017). However, if a litigant

chooses to rely upon statistics, we suggest that that

litigant ought to apply valid statistical methods.

In support of this thesis, we submit the following

quotations from Weinberg & Schumaker, Statistics:

An Intuitive Approach, 2d Ed. (Belmont, Calif., Wads

worth Publishing Co., Inc., 1969), a textbook in current

use in colleges and universities across the country:

sThe E.E.O.C. concedes, that blacks are not excluded from any jobs

and that they are paid the same as whites (C.B. 7)

22

“ . . . distortions are . . . often carried out with

the aid of statistics, the fault is that of indi

viduals using inappropriate methods . . (p.

7 ).

“The abuses of statistics are many; insight in

to basic statistical concepts is the best defense

against them. Abuses are frequently found in

popular publications as well as in technical

journals.” (p. 6)

“ . . . like any powerful instrument, it may be

abused through conscious distortion for ulter

ior motive.” (p. 8).

“Thus one finds great distrust of statisti

cal methods expressed by college students and

by others, and no wonder.” (p. 8)

“ . . . where there are abuses, the situation is

not that figures lie but that liars are apt to

figure. The solution is for the intelligent reader

to be able to figure too.” (p. 8)

The Plaintiff and the E.E.O.C. have violated certain

basic principles of the science of statistics and have

therefore produced unreliable conclusions. The use of

proper methods will produce conclusions which are

valid and which are adversely decisive of their conten

tions.

23

Returning to Weinberg & Schumaker:

“Statistical methods are essential whenever

useful information is to be distilled from large

masses of data.” (p. 2)

“ . . statistical methods may be described

as an application of common-sense reasoning

to the analysis of data.” (p. 1-2)

“Where one has both integrity and knowledge

of correct procedures, the benefits are most

apt to be great.” (p. 10)

A discussion of the appropriate statistical methods

by which valid conclusions as to a given group of peo

ple, such as the Defendant’s work force, may be ob

tained is found at pages 2-8 of the quoted work.

The authors initially explain that the problem may

be approached through the use of descriptive statistics

or sampling statistics. Descriptive statistics utilizes

raw data derived from the entire population as

to which conclusions will be stated, whereas sampling

statistics?utilizes raw data drawn from, a representa

tive sample of that population. In either case, a “basic

concept is that of randomness___If we are to gen

eralize from a sample it must be representative...

(p.2).

As a famous illustration of fallacious sampling pro

cedures, the authors describe the 1936 Literary Digest

determination that a large majority of American vot

24

ers were Landon supporters and the consequent pre

diction that Landon would easily defeat Roosevelt for

president. The Literary Digest suffered a great loss

of status, and soon ceased to exist, after Roosevelt

carried 46 out of 48 states. The “statistical sample”

used by the Digest was taken from telephone listings

and from its own list of subscribers. The sample was

neither random nor representative because only those

persons with a good income .could afford telephones

or the Literary Digest in 1936.

The data from which the Plaintiff and the E.E.O.C.

in the present case have sought to draw statistical con

clusions consists solely of information as to those em

ployees who were actively employed by the Defendant

as of October 23, 1969, when the interrogatories were

served. Quite obviously, and as to these employees,

the data constitutes descriptive statistics, since it cov

ers all of them. The data, properly analyzed, would

support any number of conclusions, but only as to. em

ployees on hand as of October 23, 1969.

However, the data cannot constitute a statistical

sample of any group of Defendant’s employees for any

purpose. With reference to the October, 1969, employ

ees it is descriptive rather than a sample. With refer

ence to employees on hand at any other time, the data

cannot serve as a sample because it is not random

but is selected as of one point in time, and it therefore

cannot be assumed to be representative.

Moreover, it is shown that useful statistical data,

either descriptive or sampling, is not available for any

25

period of time prior to October, 1969, because the De

fendant’s closed personnel files do not identify termi

nated employees by race and the Defendant does not

otherwise have this information. In other words, if the

Defendant should run a compilation similar to that ap

pearing at A. 60-80 for all of the employees that it has

ever had, but without the N and W column, the data

would obviously be worthless.

The Defendant concludes and submits, then, that the

science of statistics has a limited role to play in the

particular circumstances of this case. And insofar as

statistical methods may properly be applied to the da

ta, the Counterstatement shows that they only support

the following generalizations; stated as of October 23,

1969:

1. The ja tio of negroes to whites in the Defendant’s

work force was approximately the same as the ratio

of employable negroes to employable whites in the

community (county) from which employees may rea

sonably be assumed to be available.

2. The negro employees on hand as of October 23,

1969, had been, promoted at a mean rate slightly higher

than that applicable to the white employees on hand.

3. 66-2/3% of the Defendant’s negro supervisors

were promoted before suit was filed.

4. The ratio of negro female employees with 4 or

more children to white female employees with 4 or

26

more children was 3 to 22, or favorably comparable

to community statistics.

5. None of the employees on hand had been hired

during the month when the Plaintiff applied.

6. Of the employees on hand who had been hired

during the year when Plaintiff applied 17.3% were

black, 8.7% of females hired that year were black,

and 22.6% of males hired that year were black, as

compared to the 10% of employable blacks in the com

munity.

7. As conceded by the E.E.O.C., the Defendant was

paying blacks and whites the same pay for the same

work.

8. As conceded by the E.E.O.C., the Defendant was

not excluding negroes from any jobs.

9. Of the employees on hand, many negroes had

been promoted more rapidly than similarly situated

whites, and many negroes were earning more than

whites employed in the same jobs.

10. Among the unpromoted employees on hand, the

percentage of negroes was less than the percentage

of employable negroes in the community or in the

plant, and the unpromoted negroes are not segregated

into deadend jobs but amount to less than 10% of the

persons in their job and seniority groups.

27

11. Of the employees on hand, the average waiting

time between application and employment for negroes

was apparently shorter than the average waiting time

for whites.

3. W here The Evidence Supports The General Prop

osition That An Employer’s Hiring and Internal

Practices Are Non-Racial, The Absence O f Ne

groes, In Executive, Professional And Technical

Positions In A Relatively Small Plant In Rural

North Carolina Cannot Give Rise To A n Inference

Of Discrimination, Especially W here Such Absence

Is Cogently Explained By Sworn And Undisputed

Testimony.

The overall valid conclusion to be drawn from these

•statistical generalizations is obviously that the Defend

ant was not discriminating against negroes in its em

ployment practices as of October 23, 1969, unless the

absence of negroes in executive positions, in the main

tenance department, or in certain departments requir

ing a high degree of skill or training such as Purchas

ing-Material Control, Industrial Engineering, Product

Engineering, Accounting or Electronic Data Process

ing justifies a contrary inference.

The absence of negroes, in a plant located in a .rural ̂'

area, from professional or technical positions cannot f J

statistic ally,; Justify such an inference, since the infer

ence would require an assumption that negroes quali

fied for such positions are available in significant num

bers and have applied.

28

A

We say that an orthodox statistical approach would

require the presence of rejected applications because

active discrimination cannot have occurred without op

portunity. Although the absence of applications has

been viewed as being without significance in cases

such as Lea v. Cone Mills, DCNC 19__.__, ___ that con

clusion has only been reached in cases where the em

ployer’s general and prevailing discriminatory prac

tices were held to have discouraged applications. That

cannot be said in the present case, where the employ

er’s general usage of negroes and practices with re

gard to them is shown to be excellent.

We say that a sound statistical approach would re

quire a showing, and would not permit a mere assump

tion, that negroes with the necessary skills or profes

sions exist in the community in significant numbers,

because statistical assumptions, to be permissible,

must coincide with common knowledge and human ex

perience. That which is known to be generally untrue

cannot be assumed.

In this connection, it is a fact of which judicial notice

can be taken that negroes have historically been ex

cluded from apprenticeship programs and member

ship in labor unions, and have otherwise been relegated

to menial employment, so that they have not had the

opportunity to acquire, and have infrequently ac

quired, trade skills. It is also common knowledge that

the most casual review of education statistics would

reveal that the percentage of negroes who have ac

quired professional or technical education or training

29

is nowhere near the percentage of their prevalence

in the population, albeit for unfortunate reasons.

It was manifestly upon this sound basis that the court

in Dobbins v. Local 212, I.B.E.W., SD Ohio 1968, 292

F. Supp. 413, cited with approval by the Plaintiff and

the E.E.O.C., held as we contend; where skills were

involved:

“It is one thing to presume or assume, prima

facie-wise or otherwise, that a significant num

ber of a group have the qualifications for

schooling or voting, or jury service. It is an

other thing to assume, prima facie-wise or

otherwise, that because a certain number of

people exist, be they white or negro, that any

significant number of them are lawyers or doc

tors, or merchants or chiefs — or to be con- /

\ Crete, are competent plumbers or electricians

or carpenters.” (292 F. Supp at 445).,....

and

“To make a prima facie case for class pur

poses .. . ., the p l a i n t i f f has the burden

of showing the existe_nce bf a significant numr

her, of members of the group possessing the

basic skill in the particular trade involved.”

(292 F. Supp. at 445-446).

Of course, the fact that the Defendant has not ac

tively recruited for skilled negroes, or run a school

to advance their skills, or offered to send negroes to

0-A

Sj

p

30

technical schools or universities, cannot support any-

finding of a violation (Dobbins, supra, at 292 F. Supp.

444-445).

In summary, the statistical data in the record cannot

furnish a valid basis for any generalizations as to the

Defendant’s employment practices prior to October of

1969. However, the statistical data, when interpreted

in accordance with valid statistical methods, does af-

;\ firmatively support the inference that the Defendant

J was not engaging in discriminatory employment prac

tices as of the time to which the data applies. Since

the statistics do not show any unexplained or.e-xtra-

' ordinary imbalance in the racial composition of the

Defendant’s work force, there can be no argument that

the Defendant perpetuates an imbalance by accepting

walk-in applications or applications from persons re

ferred by employees. Nor can the absence of negroes

from certain professional and skilled jobs alone give

rise to any inference of discrimination.

There is nothing in any of the cases cited by the

Plaintiff or the E.E.O.C. to deny these conclusions,

and the cases contain much in support of them.

In U.S. v. Dillon Supply Co., 4 Cir. 1970, 429 F.2d

800, this Court merely held that unexplained s^atisticat

< / evidence “cpupled with? independent evidence was.

sufficient to justify an inference of discrimination,

where both indicated a gross racial imbalance and job

segregation and this in a case where statistics as to

the racial composition of the employer’s work force

were available and in evidence for all relevant years.

31

Moreover, the statistics showed that negroes were not

present in “white” departments, even in unskilled clas

sifications. This case cannot stand as authority in re

spect to the present case, where the available statistics

militate against any inference of discrimination, where

statistics for earlier years are not available, and where

the only “imbalance” of negroes is in highly skilled

or professional jobs.

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 8 Cir.

1970, 301 F.Supp. 675, 2 FEP Cases 1017, again involved

a situation where the statistics were available for a

number of years and where they consistently showed

less than a 2% negro work force population, in un

skilled jobs as well as others, as compared to a 24%

figure for the community.

Johnson v. Louisiana State Employment Service,

Inc., DC La 1968, 301 F. Supp 675, did not turn on staiis--

tical evidence at all. On the contrary, the trial court

had granted a summary judgment in the face of direct

testimony by the plaintiff and three other negroes that

the employment service had for 6 years repeatedly

refused to refer the plaintiff for any job except that

of “yard cutter” although he lacked only 3 credits for

a college degree, that the defendant’s representative

had told him directly that the service could do nothing

for him unless he wanted to be a yard cutter, and that

the employment service would refer the three other

negroes, two of whom were college graduates and one

of whom had college training, to nothing but menial

jobs such as porter, grocery store checker and domes

tic. In addition, one testified that he had seen the serv-

32

ice interviewer tear up the plaintiff’s application. The

defendant claimed that it would not consider the plain

tiff for a clerical job with the service because he had

not passed the civil service test, but the direct testi

mony was that the plaintiff was never advised that

he could take the testf The defendant suggests that

there is no parallel between Johnson and the case at

bar in any respect. .. —

In Lea v. Cone Mills Corporation, DC NC 1989, statis

tical comparisons for the entire life of the company

were available, since the company admitted that it

had never hired a negro female prior to March 17,

1966, that it had hired only 7 at any time thereafter,

that it had 346 employees, including white females, in

various jobs, and that it hired inexperienced employ

ees both before and after the plaintiffs applied. There

was further direct testimony that the defendant’s rep

resentative had told the negro female plaintiffs direct

ly that the plant did not hire negro females, and that

the plaintiffs were not informed of a requirement that

they renew their applications every two weeks to keep

them alive. Thus, comprehensive statistics plus direct

evidence were available, and they validly demonstrat-

{ ed, rather than militated against, an inference of dis

criminatory practices.

U.S. v. Sheet Metal Workers International Ass’n.,

Local 36, 8 Cir. 1969, 416 F.2d 123, obviously has no

hearing whatever on the present case, since it deals

only with the use of ostensibly neutral present prac

tices which perpetuate the effects of past discrimina

tion; the court found that it was unlawful for two labor

33

unions to give preference in job referrals to persons

with pre-Civil Rights Act experience, regardless of

present qualifications. Consistent with the Defendant’s

contention that the de facto absence of negroes in high

ly skilled or professional categories is not evidence

of discrimination, the court only required the two un

ions to commence referring applicants on the basis

of qualifications.

Some of these are “pattern and practice” suits, and

the Attorney General has not taken the position in any

of them that an employer must have negroes in highly

skilled or professional categories or face an inference

of discrimination. In U.S. v. Hayes International Cor

poration, 5 Cir. 1969, 415 F.2d 1038, 2 FEP Cases 67,

the Attorney General was careful to allege discrimina

tion as between “similarly qualified” employees. This

was a case, as contrasted to ours, where present statis

tics were meaningful since they showed that practical

ly all of the unskilled negro hires were placed in men

ial jobs from which they could not progress to good

jobs under the collective bargaining agreement, unless

management transferred them, and management did

not transfer them, whereas unskilled white hires were

consistently placed in jobs where they could learn

skills and in seniority divisions in which they could

progress to skilled jobs.

The case of Clark v. American Marine Corporation,

DC La 1969, 304 F. Supp. 603, 2 FEP Cases 198, is simi

lar to Hayes in that present statistics showed that all

unskilled negro hires were classified as “laborers” and

placed in a line of progression leading only to three

[ f " * J

menial jobs, and that all white unskilled hires were

classified as “helpers” and placed in lines of progres

sion where they assisted semi-skilled and skilled em

ployees and could learn and progress into those jobs.

This evidence was “coupled with” direct evidence to

the same effect, since the company admitted that it

held classes to teach semi-skilled operations to whites

but not to blacks.

In summary, none of_the cases holds that statistics

derived solely from present employees can support in

ferences as to past discrimination; none of them holds

that the absence of negroes in highly skilled or profes

sional jobs justifies an inference of discrimination

where negroes are. widely utilized in the work force

generally; .and none of them holds that hiring by walk-

in applications is discriminatory in the absence

of proof of past discrimination resulting in an extreme-

ly high percentage of white employees.^/

The Defendant submits that the statistical evidence

in this case firmly supports an inference that the De

fendant was not engaging in discriminatory practices

as of the time when the data was collected; that all

of the independent evidence, which consists of sworn

affidavits of Defendant’s witnesses and the Plaintiffs

deposition, corroborates that inference and is to the

further effect that the Defendant had never engaged

in discriminatory practices; and that the Defendant

\yas therefore entitled to a summary judgment as to

/the Plaintiff’s class action pursuant to the plain man

date of Rule 56.

35

If this Court should disagree with the Dobbins opin

ion, and should somehow conclude that the absence

of negroes in executive, professional and highly skilled

classifications demonstrates the kind of “extraordi

nary’’ statistical imbalance referred to in its DiUon

opinion, or in the Parham case, the Defendant would

yet contend that this circumstance cannot give rise

to an inference of discrimination, because (any imbal

ance is explained and the explanation is not placed

in issue. fait?-'

The E.E.O.C., in its brief (p. 12) recognizes that lack ,J

of explanation for an imbalance is essential to an in

ference of discrimination, but the Plaintiff would con

tend that explanations are entitled to no considera

tion, even if the explanation stands firm and unscathed

by any evidence produced by her (P.B. 23).

The Plaintiff interprets Johnson v. Louisiana State

Employment Service, supra, as requiring the conclu

sion that the sworn testimony of the Defendant’s per

sonnel managers past and present that negroes with

the skills used at the plant simply are not extant in

the Forest City area and that neither of these ever

encountered such applicants, can simply be ignored,

even though she was not able to come forward with

one negro person who would claim to have such skills

or say that he had applied at the Defendant’s plant

and been rejected.

Johnson does not so hold. It merely holds that the

defendant there could not establish a basis for sum

mary judgment by producing testimony that blacks

36

were not in certain jobs because none were qualified

or had applied, in the face of direct testimony by four

college-trained blacks that they had applied.

In the present case, by way of contrast, the Defend

ant has produced much statistical and direct evidence9

sin addition to statistical data, the Defendant produced sworn an

swers to interrogatories and affidavits showing that: Although

it provides no pre-employment training courses, it has per

mitted persons who so desired to use its machines and have

help from supervisors in order to learn the skills required for

employment (A. 44, Answer No. 7); this accommodation has

been extended to negroes and whites alike (A. 92); two negro

women, Edna Washburn and Elizabeth Thompson, are in

cidentally shown to have acquired sewing skills and jobs in this

manner (A. 86). The Defendant does not have any arbitrary

and non-job related employment standards that could be used

to winnow out negroes, as in many of the cases cited by Plain

tiff, but merely requires that employees be 18 years old and

able to read and write (A. 47). Whereas the Plaintiff (P.B. 19)

and the E.E.O.C. (C.B. 6) imply that the Defendant’s individual

supervisors are permitted to reject employees for any reason

that appeals to them, the actual testimony is that the employee

merely has to satisfy the supervisor of his department that he

can actually perform the work that he has applied for or been

assigned to (A. 88, lines 6-12); the employment interview refers

to the ordinary considerations of ability to do the job (A. 88, last

paragraph); and the employee is given a probationary period

within which to show satisfactory work performance (A. 89,

first full paragraph). The plant has employed negro females

in clerical positions, including those of Traffic Clerk, Process

ing-Customer Service Clerk, Accounts Payable Clerk, and Key

Punch Operator (A. 48, Answer No. 14). While supporting docu

mentation is not available, the Personnel Manager and Per

sonnel Clerk state on the basis of their best recollection and

belief that negroes have from time to time been employed in

all production classifications outside of maintenance (A. 48,

Answer 15). The plant accepts applications from all persons

who wish to apply, at all times, whether jobs are available at

the time or not (A. 49, Answer 24; A. 84). The Personnel Clerk

has been told repeatedly that race is not to be a consideration in

hiring, and that the company would in fact like to have more

37

showing that blacks are widely employed,'without any

discrimination in hire or treatment, in every depart

ment and job in the plant, including supervisory, cleri

cal and some skilled jobs, except for a few calling

for high qualifications. As to these exceptions, the De

fendant has produced the only kind of evidence that

it or anyone possibly could produce, i.e., the sworn

testimony of its personnel agents that they simply have

not had the opportunity to hire negroes in these jobs,

and that, on the basis of their knowledge of the com

munity and their personal experience, the negro popu- '/

I A \ |

lation in the Forest City area, simply does not contain w' « /

persons with the necessary skills. “

This testimony is consistent with common knowl

edge, since few rural communities of the size of Rush-

erford County can boast of resident negro industrial

engineers, product engineers, or data programmers,

and the probability of its truth is greatly bolstered by

the fact that tihe Plaintiff could come forward with

nothing to dispute it. Why then can this testimony not

be accepted as explaining why a small plant in Forest

City, North Carolina, does not have any negro account-

negroes in clerical jobs; her best recollection is that very tew

negroes have applied for clerical jobs, but that all who have

applied have been offered such jobs (A. 85). A special effort

was made to recruit negro female Margaret Whiteside for a

clerical job, but without success (A. 85, 96). The Personnel

Clerk knows of no case in which race has been considered in

any personnel action, and has seen no record reflecting such

(A. 85). The plant maintains no segregated facilities (A. 98),

and there have been no complaints of racial discrimination

from negro employees (A. 95). No negroes have applied for

skilled jobs in the maintenance department, or claimed to

have those skills (A. 96, 89), and no negroes have applied for

executive positions (A. 99).

38

ants, engineers or programmers? We submit that it

obviously can be accepted, and that it would have been

manifest error for the trial court to have done other

wise.

In summary, the Defendant submits that the statis

tical evidence as a whole established that the Defend

ant was not engaging in any discriminatory practices

as of the time when the data was collected: that no

evidence was produced to show that the Defendant bad

ever so discriminated; that any absences of negroes

in particular job classifications is adequately ex

plained by competent testimony; that the Plaintiff pro

duced no evidence to dispute any of this; and that the

Defendant was therefore clearly entitled to a sum

mary judgment as to, the Plaintiff’s class action.

4. Defendant W as Entitled To Summary Judg

ment As To Individual Claim Of Discriminatory

Refusal To Hire, Where Evidence Showed That

Defendant’s Hiring And Internal Practices Were

Non-racial, Where Plaintiff Was Admittedly

Grossly Overweight And Unskilled, Where Plain

tiff Admitted Falsifying Her Application, Admit

ted She Had Erred In Her Complaint Allegations,

Adopted Factual Information Which Controvert

ed All But One Of Her Essential Allegations, And

Where The Remaining Discrepancy Between Her

Evidence And The Defendant’s Created An Issue

Which Was Not Material.

The Defendant submits that it has produced an abun

dance of affirmative evidence showing that it has op

39

erated as an equal opportunity employer, within the

spirit and letter of Title VII, since the day it opened

its plant. This being the case, the individual Plaintiff

cannot have the benefit of any inference that a general

policy of discrimination carried over and was applied

to her, as the Plaintiffs could in Lea v. Cone Mills

Corporation, supra.

Indeed, logic and reason suggest that the Defendant

is entitled to the contrary inference, that it did not

discriminatorily refuse to hire the Plaintiff individual

ly, on the basis of its showing that it accords nan-dis

criminatory treatment to negroes generally. As the

Eighth Circuit noted in the Parham case, supra:

“The very nature of a Title VII violation rests

upon discrimination against a class character

istic .. .” .

The Plaintiff here does not claim unintentional “ef

fect” discrimination arising out of some neutrally mo-

tivated personnel policy;/she claims that, the Defend

ant simply refused to hire her because she was a negro,

which claim necessarily subsumes a premeditated ait-

The Defendant’s showing that such antagonism does

not exist as to the race should give rise to a strong '

inference that its treatment of the Plaintiff’s individual

application was not racially motivated.

It appears that the E.E.O.C. itself concurs with this

general proposition. In case after case, where indivi-

40

dual claims of discrimination were denied, the Com

mission has heavily relied upon evidence of the em

ployer’s good faith compliance with the Act in general

(E.E.O.C. Decisions Nos. 7099, YAU 9-026, 70214, 70448,

70630, 70620, 70694, 70692).

Turning to the specific testimony concerning the

Plaintiff’s individual application for employment, the

record shows only one viable issue of fact between

the Plaintiff and the Defendant, i.e., whether the De

fendant’s personnel manager, when he talked to the

Plaintiff, told the Plaintiff that he could not use her

because he considered her too obese to stand up under

laboring work day in and day out, and expressed con

cern over the number of dependent children she had,

or whether he merely said that he had no openings

but would keep her in mind.

The Plaintiff’s deposition, standing alone, would in

dicate other disputes, since she testified that she read

newspaper ads and heard radio announcements for

trainees at the Defendant’s plant in December of 1965

(A. 122, 138), and since she claimed she made a third

visit to the plant, at which time the Personnel Clerk

said that there were no openings and that she didn’t

care who had told the Plaintiff to apply (A. 167-168).

However, any issue as to the existence of the advertise

ments would clearly not be material, first because ads

appearing in December of 1965 could have no bearing

on the Plaintiff’s application made in March of 1966,

and second, because the Defendant has made no claim

that openings never existed after the Plaintiff applied,

but has asserted that she was disqualified for employ-

41

ment on the independent grounds of obesity and an

excessive number of dependent children. Nor can it

be material whether the Plaintiff made a third unsuc

cessful visit to the plant, again because the Defendant

admits and insists that it would not have employed

her if she had made a dozen visits.

And even if these disputes could have been deemed

material, they were resolved prior to the Defendant’s

application for summary judgment. The Defendant re

peatedly stated that she had been “upset” and “con

fused” during the time in question, and pleaded that

her memory was unreliable as to the identity of com

panies where she had applied for work (A. 126), as

to whether the dates in her charge form were correct

(A. 39-40), as to the sequence of her various applica

tions (A. 123) and charges (A. 124-126), and, most sig

nificantly, as to what she was told by another pros

pective employer (A. 126-127). Finally, she filed

a Statement (A. 25) in which she simply stated that 0

her memory was “cloudy” and in which she formally

adopted the information contained in the E.E.O.C.’s

“Memorandum for the File” , which was attached to /&

the Statement, and appears in the record although the

Plaintiff, apparently through inadvertence, left it out-

of the Appendix.)

By adopting the information in this Memorandum

the Plaintiff agreed that there was no evidence of any

newspaper ads; that she had in fact applied in March,

1966, and not in December, 1965, when she said she

heard radio1 ads; and . that she only made two- visits

to the plant, the second of which occurred on April

42

20, 1966, so that the claimed June visit and conversa

tion with the personnel clerk did not occur.

Therefore, as of the time of the Defendant s applica

tion for summary judgment, the only viable issue be

tween the Plaintiff and the Defendant related to the

substance of the Plaintiff’s conversation with the De

fendant’s personnel manager on the occasion of her

second visit to the plant.

The personnel manager, Fred A. Powers, did not

see the Plaintiff when she first applied, because there

were no openings at that time, and in accordance with

the Defendant’s regular procedure, he did not conduct

interviews when there were no openings. However, he

saw the application, which did not show race (A. 177),

and he immediately decided that he would not employ

the person described there for either of two independ

ent reasons: (1) he thought she was too heavy, in pro

portion to her height, to stand up day in and day out

under laboring work, and she claimed nô skills, and

(2) he was of the opinion that a woman with 9 depend

ent children at home constituted a potential absentee

ism problem. He therefore told the personnel clerk that

they couldn’t use this woman (A. 90).

As to his subsequent conversation with the Plaintiff,

Powers testified that he told her he could not use her,

and had nothing for her at that time (A. 90). The Plain

tiff agrees in substance with this much of Powers’ af

fidavit, stating that Powers said that he had no open

ings, but would keep her in mind (A. 13-14). However,

she denies that Powers said anything more, while

43

Powers siays that he went on to express his opinion

that the Plaintiff was too heavy for laboring work, and

that he expressed concern about her large number oi

dependent children.

The Plaintiff’s position is that this minor discrep

ancy created a genuine issue as to a material fact, ^

and that the trial court resolved the issue by crediting

Powers, which would, of course, be improper, in a sum

mary judgment proceeding, as we recognize.

However, examination of the trial court s decision

(A. 114) shows that the court did not ma^eA^xgdifciMy

resolution. On the contrary, the court accepted the

Plaintiff’s testimony that she applied, that she was

told merely that there were no openings, and that she

was later told that there were openings for men but

not for women. The trial court considered these as

accepted facts together with the undisputed evidence

that there were no openings when Plaintiff first ap

plied, that the Plaintiff was very obese and did have

nine dependent children at home1, that Powers con