Brown v Leake County School Board Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

May 1, 1964

38 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v Leake County School Board Brief for Appellant, 1964. 662307e8-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f4d3587c-54fc-40ca-b60e-2885fd67a07a/brown-v-leake-county-school-board-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

/ S '</o

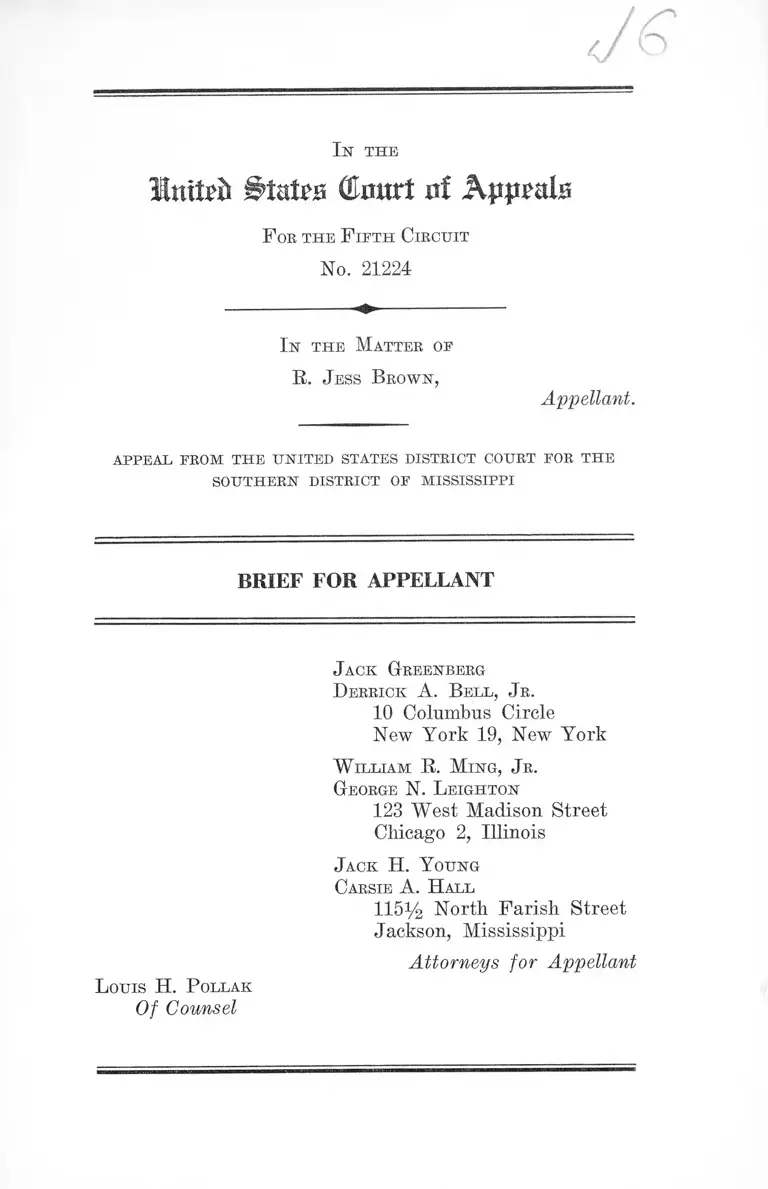

I n t h e

llttttpfr States (tort 0! Appeals

F oe t h e F i f t h C ir c u it

No. 21224

I n t h e M a t t e r of

E. J e ss B r o w n ,

Appellant.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Louis H. P o l l a k

Of Counsel

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

D e r r ic k A . B e l l , J r .

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

W il l ia m R . M in g , J r .

G eorge N. L e ig h t o n

123 West Madison Street

Chicago 2, Illinois

J a c k H . Y o u n g

C a r s ie A . H a l l

115% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

Attorneys for Appellant

I N D E X

Statement of the Case......................................................... 1

Negro Parents Retain Appellant.............................. 1

The Filing of the Suit ............................................... 4

The McBeth Motion and Affidavit .......................... 5

The Citation Order ................................................... 5

Appellant’s Return to the Citation O rder............... 7

Hearings on Citation O rder...................................... 8

The District Court’s Finding........................ ........... 11

Specification of Errors ..................................................... 13

A r g u m e n t

Preliminary Statement .......................... -........ ,........ 14

I. There Was No Professional Misconduct by the

Appellant and Therefore No Justification for

the Imposition of a Fine Under the Guise of

Costs ...———......................... -............................. — 15

1. The Method Employed to Challenge Appel

lant’s Authority as Counsel for One of His

Clients Was Im proper.................................. 15

2. Judge Cox Was Responsible for the Hear

ings ....................... 18

3. The Allegation Concerning the Shootings

Was Proper ................................................... 19

4. The Order Assessing Costs Exceeded the

Lower Court’s Authority Under 28 U. S. C.

§1927 ........ 20

PAGE

XI

5. Appellant in This Situation Was Entitled

to Judicial Protection Rather Than Pun

ishment ........................................................... 22

II. The Vindication of Civil Rights Through

Legal Processes Will Be Seriously Restricted

Unless the Unreasonable Standard of Profes

sional Conduct Imposed by the Court Below

Is Set Aside ......................................................... 24

C o n c l u s i o n .......................................................................... 30

A u t h o r it ie s C it e d

Cases:

Bailey v. Patterson, 199 F. Supp. 595 (S. D. Miss.

1961), 368 U. S. 346, 369 U. S. 1; 323 F. 2d 201 (5th

Cir. 1963) ......................................................................... 1

Beckley v. Newcomb, 24 N. H . 359 (1852) ...................... 16

Bone v. Walsh Construction Co., 235 Fed. 901 (S. D.

Iowa 1916) ....................................................................... 21

Brislin v. Killanna Holding Corporation, 85 F. 2d 667

(2d Cir. 1936) ................................................................. 21

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia, 32 U. S.

Law Week 4374 (April 20, 1964) .................................. 14

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) .... 24

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917) ...................... 19

Cammer v. United States, 350 U. S. 399 (1956)............... 22

Commonwealth v. Serfass, 5 Pa. Co. 139 (1888) 16

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) ........................... . 19

Coyne and Delaney Co. v. G. W. Onthank Co., 10

F. R. D. 435 (S. D. Iowa 1950) ...................................... 21

Darby v. Daniel, 168 F. Supp. 170 (D. Miss. 1958) ____ 2

PAGE

I l l

Enochs v. Sisson, 301 F. 2d 125 (5th Cir. 1962) ........... 16

Evers v. Jackson Mun. Sep. School Disk, 328 F. 2d 408

(5th Cir. 1964) .... ...... ............................ ........... . .49. 24, 27

Ex Parte Secombe, 19 How. 9 (1857) ....- ........................ 22

Farmer v. Arabian American Oil Co., 324 F. 2d 359 (2d

Cir. 1963), cert, granted March 10, 1964 ..................... 15

Farrington v. Wright, 1 Minn. 241 (1856) ...................... 16

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Sep. Seh. Hist., Civ. No.

BC 6428 (N. D. Miss.) ......_............................................ 2

Henry v. Coahoma County Board of Education, 8 Race

Eel. Law Rep. 1480 (1963)............................................. 2

Herron v. Herron, 255 F. 2d 589 (5th Cir. 1958) ........ . 16

Hudson, et al. v. Leake County School Board, Civil No.

3382 .................................... .................. .......... ............ .1,4, 27

Kemart Corp. v. Printing Arts Research Laboratories,

232 F. 2d 897 (9th Cir. 1956).................................... 15

Kennard v. State of Mississippi, 128 So. 2d 572 (Miss.

1961), cert, den., 368 U. S. 869 (1961) ...................... 2

Lichter Foundation Inc. v. Welch, 269 F. 2d 142 (6th

Cir. 1959) .......................................- ............ .......... ........ 15

Mason v. Biloxi Muni. Sep. Sell. Hist., 328 F. 2d 408

(5th Cir. 1964) ............. ...... ....... .................................... 1-2

McDowell v. Fair, 8 Race Rel. Law Rep. 459 (1963) .... 1

Meredith v. Fair, 298 F. 2d 696, 305 F. 2d 343 (5th

Cir. 1962)............................................. .......................1, 24, 28

Motion Picture Patents Co. v. Steiner, 201 Fed. 63 (2d

Cir. 1912)

PAGE

2 1

IV

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) ...........14, 24, 28, 29

In Re Stern, 121 N. Y. S. 948 (1910) .............................. 22

Toledo Metal Wheel Co. v. Foyer Bros. & Co., 223

Fed. 350 (6th Cir. 1915) ................................................ 21

United States ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F. 2d

71 (5th Cir. 1959) .....................................................2,14, 25

Weiss v. United States, 227 F. 2d 72 (2d Cir. 1955) .... 21

Statutes:

7 U. S. C.

§901 et seq................... 26

28 U. S. C.

§1291 ......................................................................... 15

§1927 .............................................. 20,21,22

Miss. Code 1942 Annot.

§3841(3) ................. 4

§4065.3 ...........................................................................4, 24

§6220.5 .......................................................................... 24

§6334-11 ...... 24

F. R. C. P., Rule 6(d) .................................................. 16

Other Authorities:

Campbell, The Lives of The Lord Chancellors, Vol. VI,

pp. 390-97 (1847)............................................................. 20

7 C. J. S. 884-85 ............................................................. 16

1963 Report of the United States Commission on Civil

Rights, pp. 117-119......................................................... 14, 25

PAGE

V

PAGE

6 Moore’s Federal Practice 1309 (1953) ------ --------- ---- 15

Opinions of Committee on Professional Ethics and

Grievances, p. 89 (American Bar Assoc., Op. 17) ....... 17

Parry, The Seven Lamps of Advocacy, p. 30 (1923) .... 23

Canon 25, American Bar Association ..................... .... 16

In the

Hutted States (Enurt uf Appeals

F ob t h e F i f t h C ir c u it

No. 21224

I n t h e M a t t e r o f

R . J e ss B r o w n ,

Appellant.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Statement of the Case

Negro Parents Retain Appellant

Appellant is a Negro attorney duly licensed and a prac

ticing member of the Mississippi Bar. He is also a member

of the Bar of the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Mississippi.1 In 1961, he was retained

1 Appellant is 51 years old and was admitted to practice in 1954,

after two years of law school at Texas Southern University in

Houston (R 39-40). Prior to that time, he had been a school

teacher in Mississippi, Texas and Kentucky (R 41).

Since his admission to the Mississippi bar, appellant has been

involved in many of the civil rights cases filed in that state, in

cluding Meredith v. Fair, 298 F. 2d 696, 305 F. 2d 343 (5th Cir.

1962); McDowell v. Fair, 8 Race Rel. Law Rep. 459 (1963) (Uni

versity of Mississippi desegregation); Bailey v. Patterson, 199 F.

Supp. 595 (S. D. Miss. 1961), 368 U. S. 346, 369 U. S. 1, 323

F. 2d 201 (5th Cir. 1963) (public travel desegregation); Hudson

v. Leake County School Board and Mason v. Biloxi Muni. Sep.

2

by a group of Negro parents to assist them in efforts to

desegregate public schools of Leake County, Mississippi.

A dozen of these parents had come to Jackson during

the summer of 1961 to request lawyers to help them de

segregate their schools, and met appellant during this visit

(R 46, 48). They explained that a Negro school in their

community, the Harmony School, had been closed, and they

had made unsuccessful efforts to have it reopened, but

were now abandoning such efforts in favor of desegregating

all schools (R 51). No retainers were prepared, but the

group was promised legal assistance (R 52).

Subsequently, a petition requesting the Leake County

School Board to desegregate its schools was prepared and

Sch. Dist., 328 F. 2d 408 (5th Cir. 1964) ; Henry v. ClarJcsdale

Municipal Sep. Sch. Dist., Civ. No. BC 6428 (N. D. Miss.) (public

school desegregation); Henry v. Coahoma County Board of Edu

cation, 8 Race Rel. Law Rep. 1480 (1963) (right of public school

teacher and husband to take part in civil rights activity); United

States ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F. 2d 71 (5th Cir. 1959);

Kennard v. State of Mississippi, 128 So. 2d 572 (Miss. 1961),

cert, den., 368 U. S. 869 (1961) (jury discrimination); Darby v.

Daniel, 168 F. Supp. 170 (D. Miss. 1958) (voting discrimination).

In addition to the above cases, appellant has participated in the

defense of approximately 1500 persons arrested in Mississippi as

a result of protest demonstrations against racial segregation, in

cluding more than 300 “ freedom riders” who tested public trans

portation facilities in 1961, 1,000 persons arrested during protest

demonstrations in Jackson in 1963, and approximately 125 arrested

in similar demonstrations in Biloxi, Greenville, Canton, Clarks-

dale, Greenwood, Winona, Indianola and Lexington, Mississippi.

Appellant has raised the issue of jury discrimination or other

similar constitutional issues in more than 8 felony cases including

cases of Negroes charged with raping white women. Convictions

in 2 of these cases have been reversed on this point. One client,

Mack Charles Parker, was lynched in April, 1959, a few days

before his trial for rape of a white woman, and a few days after

appellant had moved to quash the indictment based on jury

discrimination (April Term 1959, Cir. Ct., Pearl River Co., Miss.).

While appellant is now one of three Mississippi attorneys who

handle “ civil rights” cases, from 1954 until about 1961 he was

the only Mississippi attorney who did so.

3

signed by 53 parents (E 56-57). This petition was mailed

to appellant who then prepared retainer forms authorizing

him to bring a school desegregation suit, and went to Leake

County, a rural farming community 50 miles from his office

in Jackson (E 183). Appellant met with a group of parents,

explained that he needed their authorization to file the peti

tion and if necessary a lawsuit (E. 75), obtained signatures

of those present on retainers and left blank retainer forms

with leaders of the group who promised to obtain the signa

tures of the other parents who wished to join in the suit

(E 76).

In February 1962, appellant forwarded this petition to

the Leake County Board of Education, and while he re

ceived no response from the Board (E 65), the principal

of the Negro high school wrote each of the petitioners ad

vising against desegregation (E 6). Two white men, the

game warden and the owner of a local milk dairy, visited

the Negro community to persuade persons to withdraw their

names from the petition (E 261-62).

Following submission of the petition to the Board, ap

pellant learned through newspaper reports that several

petitioners had withdrawn their names (E 58, 63). They

were, in general, sharecroppers living on land owned by

whites, and according to one witness, withdrew under pres

sure (E 245). None of these persons personally reported

to appellant their decision to withdraw, but as he learned

of their decisions, he ceased including them in the desegre

gation effort (E 58, 65).

Eeceiving no response to the original petition, appellant

in August 1962 prepared and filed a second petition re

questing the Board to desegregate the public schools (E

65, 83). Appellant heard nothing from the Board. How

ever, in October 1962, appellant was informed that several

homes in the area where petitioners live were shot into

(E 96-97). This information was deemed sufficiently con-

4

nected to the school desegregation efforts to justify men

tion in the complaint (E 98-100).

Because he had learned that many of the persons who

originally signed retainers had withdrawn, appellant made

another trip to Leake County prior to filing suit to ascer

tain which persons wished to continue (E 83-84).

The Filing of the Suit

In March 1963, appellant filed in the United States Dis

trict Court for the Southern District of Mississippi, Hudson,

et al. v. Leake County School Board, Civil No. 3382, on

behalf of 13 parents who represented 28 minor children.

In response, the Leake County Board of Education filed a

motion to dismiss alleging that the plaintiffs had failed to

exhaust administrative remedies under the Mississippi

Pupil Assignment Law. The Board noticed its motion for

April 5, 1963 and hearing was set for that date (SE 301).

The Board was represented by its attorneys J. E. Smith

and H. W. Davidson and by Will S. Wells, an assistant to

the State Attorney General, who, in accordance with state

law joined with the school board attorneys in defending

this suit.2

2By State Statute, enacted in 1958 (§3841(3), Miss. Code

1942 Annot.), the Attorney General is authorized to represent any

school official in suits challenging the constitutional validity of

state law determining inter alia which person shall attend or be

enrolled in state colleges and schools.

In addition, §4065.3 Miss. Code 1942 Annot., requires the entire

executive branch of the state government:

“ to prohibit, by any lawful, peaceful and constitutional means,

the implementation of or the compliance with the integration

decisions of the United States Supreme Court of May 17,

1954 (347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. ed. 873) and of

May 31, 1955 (349 U. S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99 L. ed. 1083),

and to prohibit by any lawful, peaceful and constitutional

means, the causing or mixing or integration of the white and

Negro races in public schools, . . . by any branch of the fed

eral government. . . . ”

5

The McBeth Motion and Affidavit

At the conclusion of the hearing and with no prior no

tice to appellant, Assistant Attorney General Wells filed

a second motion to dismiss the suit, or in the alternative

to remove the name of Gwennell McBeth, a minor by Ruthie

Nell McBeth (R 10, 102). The motion alleged that Mrs.

McBeth did not authorize appellant to bring suit in her

name, and that she has no complaint with the operation of

the schools. The motion also stated that the allegation in

the complaint that Mrs. McBeth’s home was shot into was

“wholly and utterly false.” The motion was supported by

an affidavit by Mrs. McBeth swearing that statements in

the motion were true and made by her “ freely and volun

tarily and without any undue influence” (R 12).

Appellant was “ shocked” and “ completely amazed” when

he heard this motion (R 103). He did not have plaintiffs’

retainers with him, but in accord with his policy of immedi

ately releasing those who decided to withdraw, readily con

sented to striking Mrs. McBeth’s name from the complaint

because he did not desire her to be a party if she wished to

withdraw (R 102-03, 129). Therefore, with appellant’s full

acquiescence, District Judge Mize granted the motion and

struck the name of Ruthie Nell McBeth from the complaint

(R 13).

After the hearing, appellant checked his records and

found a retainer signed by Ruthie Nell McBeth (R 104,110)

which authorized him to take any action he deemed neces

sary including the filing of petitions and institution of liti

gation, to desegregate the public school system in Leake

County (R 23, SR 346-47).

The Citation Order

The following day, April 6, 1963, appellant met with

Judge William Harold Cox, Southern District, Mississippi,

6

in Ms chambers on another matter. During the course of

their conversation Judge Cox informed appellant that the

McBeth affidavit had been brought to his attention and that

based on its allegations, he was in the process of preparing

a citation order (E 107). Judge Cox did not solicit any

information from appellant about the validity of the charges

made in the affidavit, and gave appellant to understand

that he would take up the whole matter later (E 108-109).

For this reason, appellant did not seek to explain why he

had been unable to contradict the allegations in the affidavit

on the preceding day and did not produce the McBeth re

tainer. It was his belief that Judge Cox did not want to

hear anything on the matter at that time (E 107-09). As

appellant explained on the stand:

“ Now, if he had a said to me at that time uh in talk

ing he usually refers to me as Jess he says well, Jess,

what happened on that thing yesterday, what was the

situation, what was it about, but he didn’t do that be

cause at least if he did I didn’t get the understanding

that he did, let’s put it that way, I don’t want to say

what he didn’t do but I want to say what I didn’t under

stand. If I had of understood it that a way I would

have been happy to explain it in his chambers uh and

showed him everything that I had with that respect.

That’s the reason why I didn’t do it it didn’t appear

to me that the door was open at that time to explain

it to him in his chambers” (E 108-09).

Later during the same day, appellant was served with

an order for citation for contempt issued by District Judge

Cox. The order recited that there were probable irregu

larities on the part of appellant in the institution of the

Leake County school suit. Specifically, the order referred

to the circumstances surrounding the employment of appel

lant as counsel by Euthie Nell McBeth and “ serious charges

7

made [in the complaint] against an entire community in

this sta ted irectin g appellant, in this regard:

[T ]o show the Court the factual foundation of para

graph 5(e) of the complaint to the effect that “during

the nights of October 4th and 5th, 1962, the homes

of Plaintiffs Mr. James Overstreet and Mrs. Ruthie

Nell McBeth and other [N]egroes, were shot into by

parties whose identity local law enforcement authorities

have failed to ascertain” and as to the intended rele

vancy and pertinency and purpose of said charge in

this suit (R 14).

The citation was returnable on April 20, 1963. On April

12th the Court asked appellant to decide whether or not

he wanted a jury because the matter was thought to be in

the nature of a criminal contempt procedure. However,

at the outset of the hearing on April 20th, Judge Cox stated

that the proceeding was not for contempt, but was a pro

ceeding for the discipline of an attorney at the bar of the

court (SR 295).

Appellant’s Return to the Citation Order

Appellant prepared a sworn return to the order of cita

tion for contempt which he filed at the April 20th hearing

(B 16-19). The return averred that all the named plaintiffs

in the case had duly retained appellant to represent them

and their children in an effort to desegregate the public

school system of Leake County, Mississippi, and to take

any and all steps available to that end (R 16). With re

spect to the factual foundation of the allegation of para

graph 5(e) of the complaint, appellant averred (R 18):

[T]here are numerous witnesses to the fact that some

person or persons did on or about October 4-5, 1962,

shoot into buildings and structures used and occupied

8

by the plaintiffs named in paragraph 5(e) of the com

plaint and other Negro citizens of Leake County. So

far as [appellant] was informed at the time of the

filing of the complaint, local law enforcement authori

ties had not ascertained the identity of the persons

responsible for these attacks on Negro residents of

Leake County. These allegations are deemed by [ap

pellant] and other counsel for plaintiffs to be relevant

to the issue of necessity for prior exhaustion of admin

istrative remedies of plaintiffs raised by defendants.

But defendants have raised no issue as to the relevancy

of these allegations so that [appellant] respectfully

urges that any inquiry by this court at this time as to

their relevancy is premature.

Appellant’s return prayed the court to discharge the cita

tion or, in the alternative, grant him notice and hearing

of any charges of improper conduct (R 19).3

Hearings on Citation Order

At the April 20th hearing, appellant’s counsel attempted

to postpone the proceeding pending disposition of the main

case explaining that Judge Mize had entered an order strik

ing Ruthie Nell McBeth’s name from the complaint and

that appellant’s willingness to have this done was based on

the fact that he had no notice of the motion and that Mrs.

McBeth could withdraw from a lawsuit at anytime (SR

301-02). Judge Cox responded that he had not heard those

facts before but:

3 Appellant also urged the Court to exercise its supervisory

power over members of the bar to inquire into the relationship,

if any, between counsel for the defendants and Mrs. McBeth

(R 18-19). A t the April 20th hearing, appellant questioned the

propriety of the introduction of the McBeth affidavit to the court

by counsel for the defendant (SR 308-09). Judge Cox replied that

in the absence of a charge o f impropriety, he was not “ looking for

any trouble” (SR 309).

9

“That is something I think I ought to hear on a hearing

of all the facts and all the evidence in its proper setting

and perspective” (SR 303).

Later Judge Cox stated:

“ . . . let’s try this thing and if Jess is innocent and I

hope he is let’s find out that from the evidence” (SR

305-06).

Appellant’s counsel suggested that the return fully an

swered the citation order and that the citation should be

discharged.

Judge Cox replied:

“ I don’t know what you have got in your response to

the citation but I will let you file it but I want to hear

a full development on the facts . . . ” (SR 306).

Judge Cox then refused to discharge the citation but

amended it to direct appellant to “ show cause why he should

not be disciplined by this Court for any impropriety or

impermissible irregularity” (R 21, SR 304).

At the outset of the hearing on May 11, 1963, counsel for

appellant again moved the court to discharge the citation

order on the ground that the return is sufficient so as to

require no further proceedings by the court (SR 316-17).

Judge Cox promptly overruled the motion.

Counsel for the Court rested after calling Ruthie Nell

McBeth, her mother Bertha Kirkland, and the appellant.

Based on their testimony which fully supported the allega

tions in appellant’s return to the citation order, appellant

moved the Court to find “ that the respondent had not been

guilty of any improper conduct as a member of the Bar of

this Court” (R 157). However, the Court stated:

10

I am going to let you put your evidence on and I will

hold your motion. I want to hear everything that there

is to be said in connection with a matter of this kind

and I will just reserve ruling on your motion (R 158).

Appellant’s counsel then introduced testimony from seven

witnesses and various documents which detailed the first

steps of a small group of Negro parents to implement the

Supreme Court’s school desegregation decision in a rural

Mississippi county, and appellant’s good faith efforts to

help them attain this goal.

As to the allegations in the affidavit of Ruthie Nell Me-

Beth, the testimony showed that Mrs. McBeth, despite her

sworn motion, had signed a retainer in December 1961,

authorizing appellant to bring a school desegregation suit

on her behalf (SR 346-47). On the stand, she testified that

she had not read the retainer before signing it and thought

it merely another petition to the school board to win re

opening of the Harmony School (SR 361, 372), but there

was ample testimony that she carefully read and understood

the petition and the retainer (R 165-66, 246-47), and that

she and her mother, Mrs. Bertha Kirkland, who attended

NAACP meetings on the school desegregation problem

when her daughter couldn’t come (SR 400) were quite aware

of, and in accord with, the group’s goal of desegrated

schools. Ruthie Nell McBeth in signing the petition re

portedly stated with reference to her child: “ . . . I don’t

mind Pun kin going to a white school because I know she

will have plenty of protection . . . ” (R 189). Her mother

at one point volunteered to sign for her daughter (R 85),

and later indicating impatience at the delay in filing the

suit, suggested that perhaps another attorney should be

hired because, “ Jess Brown ain’t got sense enough to file

the suit” (R 217)

11

Their positions changed, however (R 250), although they

did not report to appellant their decision not to go further

(R 120). When the suit was filed listing Mrs. McBeth as a

plaintiff, and listing her home as one of those shot into in

October 1962, her mother reading a newspaper story of the

suit, and making no effort to contact appellant at the

address he had given her (E 205), went to the newspaper

office to inquire how her daughter’s name could be removed

from the suit (SR 326-27). Called by an employee of the

newspaper, school board attorney J. E. Smith came im

mediately to the newspaper office and conferred with Mrs.

Kirkland (SR 391), with the result that two weeks later

she and Ruthie Nell McBeth returned to Attorney Smith’s

office and signed the motion and affidavit prepared by him

(SR 353, 363). Neither woman knew or was told by At

torney Smith that he represented the school board in this

case (SR 384, 426, 432), or that the motion and affidavit

would be filed in the case (SR 420). Moreover, while he

had knowledge of the facts contained in the motion on

March 9, 1963, two days after the suit was filed (SR 363),

and two weeks before the motion and affidavit were signed

on March 23, 1963, he made no effort to inform appellant

of the information concerning one of the plaintiffs which

he possessed.

It also appeared that while Mrs. McBeth’s home was

not shot into as alleged in the complaint, the allegation

was not ‘■'wholly and utterly false,” in that her cafe located

some 400 yards from her home had been shot into (SR 338,

370, 410), as were the homes of at least six of her neigh

bors (SR 370-71), including her brother who lives only

200 yards from her cafe (SR 357).

The District Court’s Findings

On August 20, 1961, Judge Cox submitted his Findings

of Fact and Conclusions of Law. He found that appellant

“ in good faith understood and actually intended the instru

12

ment [executed by Euthie Neil McBeth] to employ bim

as her attorney in this case” (R 24). Judge Cox failed to

find any “ causal connection” between the complaint’s al

legations that homes of the plaintiffs had been shot into and

the subject matter of the case, but regarded the allegations

as innocuous under the circumstances (R 24).

Nevertheless, Judge Cox assessed appellant with all costs

of the disciplinary proceeding. Judge Cox assigned the

following reason for assessment of costs (R 24):

[T]he respondent was advised by the Court on April

6,1963, that he was being citated to explain his conduct

in the instances mentioned to the Court prior to the

signing of the order therefor, but he made no attempt

to make any explanation, or showing to the Court at

the time although he had his brief case with him.

Judge Cox concluded that “ Forthrightness and candor

and honesty” required appellant “ to voluntarily explain

his action in instituting this suit in the name of this woman

after she presented her affidavit and motion to the effect

that she had not authorized him to include her name in this

suit” (emphasis added, R 24-25). It was appellant’s failure

to explain this situation that necessitated two and a half

days hearing in this matter, Judge Cox found and while

he ordered the citation discharged because “ . . . it is not

shown by a preponderance of the evidence that the respon

dent is guilty of any wanton impropriety in the respects

in question;” appellant was assessed with all costs (R

25-26).

Pursuant to the Court’s order of August 20, the bill of

costs in the amount of $263.87 was filed on September 17

(R 27). Thereupon, appellant moved to vacate the order

assessing the taxing of costs contending “that there is

no basis in fact or law for assessing the taxing of costs

upon respondent” (R 28).

13

On October 25, 1963, Judge Cox overruled appellant’s

motion. Reviewing Ms earlier action, be reported “ that

this Court had no intention of completely, fully and finally

exonerating the respondent, R. Jess Brown, from any im

propriety or wrong doing. . . . ” (R. 29). He again found

that the failure to promptly report that he had a retainer

for Ruthie Nell McBeth violated appellant’s duty of “ forth

rightness, candor and honesty” owed the court, and this

failure impelled the court to spend two and a half days

hearing this matter (R 30).

Notice of appeal to this Court from the denial of ap

pellant’s motion to vacate the order assessing costs was

filed on October 28, 1963 (R 31). Appellant’s motion for

stay of the order assessing costs pending appeal was sus

tained by Judge Cox on that date (R 33).

Specification of Errors

1. The court below erred in finding that appellant’s

conduct constituted a breach of duty to the court.

2. The court below erred in assessing costs upon ap

pellant on the ground that appellant’s conduct necessitated

two and one half days of hearings.

3. The court below erred in assessing a fine under the

guise of costs in this case, which assessment violates ap

pellant’s right to due process under the Fifth Amendment.

4. The court below erred in holding appellant to a stand

ard of conduct which is unreasonable as applied to Mm and

restrictive of the constitutional right of association to vindi

cate legal rights by litigation.

14

A R G U M E N T

Preliminary Statement

While the question before this Court may be framed in

terms of whether the District Court abused its discretion in

assessing appellant with the $263.87 costs in the discipli

nary proceeding, this Court’s decision will determine

whether Negroes in Mississippi who associate for the pur

pose of vindicating legal rights through litigation may be

deprived of the constitutional protection in such activities

set. forth by the Supreme Court of the United States.

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963); cf. Brotherhood

of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia, 32 U. S. Law Week 4374

(April 20, 1964). Moreover, this case poses the issue of

the integrity of that small segment of the Southern bar

that will handle civil rights issues. See, 1963 Report of the

United States Commission on Civil Rights, 117-119; United

States ex rel. Goldshy v. Harpole, 263 P. 2d 71, 82 (5th

Cir. 1959).

Therefore, appellant contends that his conduct in repre

senting Negro parents who sought his professional help in

their efforts to desegregate the Leake County, Mississippi,

public schools was entirely proper. Indeed, he rendered his

duty to the district court with as much forthrightness,

candor, and honesty as his information and the situation

would allow. And he submits that to hold him, and those few

Mississippi attorneys willing to represent Negroes in civil

rights cases, to the unreasonable standard set by the court

below, will greatly increase the difficulty of an already ex

tremely hazardous area of practice, seriously restricting

15

efforts of Mississippi Negroes to seek judicial protection

of their constitutional rights.4

I.

There Was No Professional Misconduct by the Appel

lant and Therefore No Justification for the Imposition

of a Fine Under the Guise of Costs.

The court below abused its discretion in taxing costs

upon appellant for failing to explain his employment by

Ruthie Nell McBeth to the court on April 5-6, 1963. The

court found this failure was a breach of appellant’s duty of

forthrightness, candor, and honesty with the court which

necessitated two and one half days of hearings.

Appellant submits, however, that his inability to explain

his employment by Ruthie Nell McBeth on April 5-6, 1963,

was not a breach of duty and neither necessitated two and

one half days’ hearings, nor justified imposition of a fine

under the guise of costs.

1. The method employed to challenge appellant’s

authority as counsel for one of his clients

was improper.

Appellant committed no breach of duty on either April

5th or 6th. The motion presented to the court on April 5th

by an assistant attorney general of the State of Mississippi,

took appellant entirely by surprise (R 102, 103, 129).

4 This Court has jurisdiction of this appeal, from a final judg

ment for costs under 28 U. S. C. §1291. The issue presented is not

whether the district judge should have allowed or disallowed par

ticular items of costs, but is rather whether he exceeded, and there

fore abused, his discretion. Farmer v. Arabian American Oil Co.,

324 F. 2d 359 (2d Cir. 1963), cert, granted March 10, 1964;

Lichter Foundation Inc. v. Welch, 269 F. 2d 142 (6th Cir. 1959);

Kemart Corp. v. Printing Arts Research Laboratories, 232 F. 2d

897 (9th Cir. 1956) ■ 6 Moore’s Federal Practice 1309 (1953).

16

The motion was offered in direct violation of Rule 6(d),

F. R. C. P., which required a minimum of five days notice

to appellant of Mrs. McBeth’s motion and affidavit. Herron

v. Herron, 255 F. 2d 589 (5th Cir. 1958); Enochs v. Sisson,

301 F. 2d 125 (5th Cir. 1962).

Appellant suffered here the very harm which this Court

has found Rule 6 was intended to prevent. Herron v. Her

ron, supra, at 593. Nor are the federal rules unique in the

requirement of notice, particularly in motions questioning

an attorney’s right to represent a client. Indeed, applicable

and ancient authority holds that the failure to give notice

of a motion objecting to an attorney’s right to appear is

of itself grounds for reversing an adverse order on such

motion. Thus, it was held in Beckley v. Newcomb, 24 N. H.

359 (1852), the presumption that an attorney is authorized

to appear may not be rebutted without previous notice to

the attorney, and in Farrington v. Wright, 1 Minn. 241

(1856), an order compelling an attorney to file evidence of

his authority was held void as obtained without notice.

Cf. Commonwealth v. Serfass, 5 Pa. Co. 139 (1888). See

generally, 7 C. J. S. 884-85.

But the Assistant Attorney General’s failure to give no

tice of the McBeth motion not only disregarded the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure, but also violated the Canons of

Ethics of the American Bar Association. Canon 25 of the

American Bar Association admonishes:

“ A lawyer should not ignore known customs or prac

tice of the Bar or of a particular Court, even when the

law permits, without giving timely notice to the oppos

ing counsel.”

The American Bar Association’s Committee on Ethics

found that adherence to Canon 25 is “ . . . the invariable

practice of the Bar, in all courts of this county . . . ” and

17

“any other practice would defeat that fair impartial ad

ministration of justice for which our courts are instituted

and which the members of the Bar are sworn to uphold.”

The failure to give notice of a motion to substitute attor

neys to the attorney sought to be displaced, irrespective of

rules of court and irrespective of the movant’s belief that

the attorney was guilty of negligence in his handling of the

case and would demand an unreasonable fee which would

delay settlement was deemed unprofessional conduct.

American Bar Association, Opinions of Committee on Pro

fessional Ethics and Grievances, p. 89 (opinion 17).

The record reveals no reason why counsel for the school

board failed to notify appellant either that one of the

plaintiffs did not desire to be a party in the suit, which

knowledge he obtained on March 9, 1963 (SB 391), or that

he intended to file Mrs. McBeth’s motion and affidavit which

he prepared and had signed on March 23, 1963. But what

ever their reasons, the opposing counsel’s omission vio

lated the federal rules, generally accepted rules of court

conduct, and professional ethics. I f the time of the district

court was misspent in this inquiry, appellant respectfully

submits that it was because of the opposing counsel’s failure

to notify appellant by motion or otherwise of his intended

inquiry into appellant’s right to represent one of the peti

tioners.

Nevertheless, at the April 5th hearing, appellant was as

candid as it was possible for him to be under the circum

stances. Appellant’s first concern was that Ruthie Nell

McBeth’s name be stricken from the suit if she no longer

wished to be a party. Since appellant had received no ad

vance warning of the McBeth motion, he did not have the

McBeth retainer in court at the time and thus could not

present it to the court. Appellant did the only thing he

could d o : he returned to his office and verified the existence

of the retainer.

18

By the following day, April 6th, appellant knew that he

had a retainer for Mrs. McBeth which appeared to contain

her signature (E 110). He had not yet been able to check

the matter with Mrs. McBeth or the Leake County parents

(E 112), when Judge Cox advised him that he had just

learned about the matter and was preparing a citation order

(E 107).

Appellant, concluding from this statement that an ex

planation was neither expected nor desired, testified:

“ . . . I got the understanding that at that time I was

not supposed to explain to him [Judge Cox] what had

happened because the first thing that he mentioned in

regard to the affidavit was that he was preparing a

. . . citation order for me. . . . ” (E 108).

In short, appellant submits that he was not attempting to

be evasive with Judge Cox, but was merely attempting to

be as responsive to the Judge’s wishes as the situation into

which he was thrust by opposing counsel’s motion would

permit.

2. Judge Cox was responsible for the hearings.

Appellant’s failure to explain his employment by Euthie

Nell McBeth to the court on April 5th and 6th did not

necessitate two and one half days of hearings. Appellant

did explain his employment by Euthie Nell McBeth to the

court in his sworn return to the order of citation. There,

appellant showed that he had been duly retained by all of

the named plaintiffs, including of course, Euthie Nell Mc

Beth (E 16).

Judge Cox permitted appellant to file the return but said

(SE 306):

“ I don’t know what you have got in your response to the

citation, but I will let you file it. But I want to hear

a full development of the facts . . . ”

19

Appellant was prepared and attempted several times at

the April 20th hearing to offer exculpatory evidence, but

was given no opportunity to do so (SR 301-02). At the

outset of the hearing on May 11th, appellant moved the

court to discharge the citation order (SR 316-17), and re

newed this motion after counsel for the court rested (R

157), but to no avail.

Thus, in the face of the showing, under oath, that appel

lant had been properly retained by all the named plaintiffs,

Judge Cox refused to discharge the citation insisting:

“ I want to hear everything that there is to be said in con

nection with a matter of this kind. . . . ” (R 158).

3. The allegation concerning the shootings was proper.

In addition to the matter of his employment by the peti

tioners, the citation order required appellant to explain

the allegation that petitioners’ homes were shot into, which

allegation the district court reviewed as a serious charge

against an entire community in the state (R 14, 20). While

appellant subsequently proved that several homes in the

community where petitioners live had been shot into

(R 225-29; SR 338, 370), and explained that the incident

was thought to be one of a series of efforts to intimidate

petitioners from seeking their constitutional rights which

would affect the issue of exhaustion of administrative reme

dies (R 18, 98-99), the district court concluded that “ No

causal connection between the shooting and the subject

matter of the complaint is shown by the evidence” , dis

missing it as “ an innocuous statement under the circum

stances” (R 24).

But far from “ innocuous”, the allegations in the com

plaint illustrating the determination of the state and com

munity to retain segregated schools was not only relevant

and material, see Evers v. Jackson Mun. Sep. School Dist.,

328 F. 2d 408 (5th Cir. 1964), Cooper v. Aaron, 358 IJ. S. 1

(1958), and Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917), but

20

in the highest traditions of onr jurisprudential system,

performed the service of calling the court’s attention to

actions intended to dissuade petitioners from even bringing

their constitutional claims to the federal court.5

4, The order assessing costs exceeded the lower court’s

authority under 28 U. S. C., §1927.

Appellant’s liability for costs is controlled by 28 U. S. C.,

§1927 which provides:

“Any attorney or other person admitted to conduct

cases in any court of the United States or any Territory

thereof who so multiplies the proceedings in any case

as to increase costs unreasonably and vexatiously may

be required by the court to satisfy personally such ex

cess costs.” (Emphasis added.)

5 See, Campbell, The Lives of The Lord Chancellors, Yol. VI,

pp. 390-97 (1847), where Lord Thomas Erskine (1750-1823) de

scribed by Campbell, p. 368 as “ the brightest ornament of which

the English Bar can b oastrep resen ted a Captain Baillie in a

situation analogous to aj)pellant’s. Captain Baillie, a veteran sea

man, was appointed director of a naval hospital. Appalled by the

abuses he found there, Captain Baillie tried in vain to obtain

reforms, from his superiors. Finally he published a statement of

the hospital’s case detailing the real facts without exaggeration,

which facts reflected rather severely on one Lord Sandwich, First

Lord of the Admiralty, who had been using the hospital facilities

to further his personal ambitions. Captain Baillie was suspended

and, at the prompting of Lord Sandwich, who took no active part,

was charged with criminal libel by the Board of Admiralty.

Erskine in addressing the Court not only argued his client’s

innocence of the charges, pointing out that it was the Captain’s

duty to expose the corruption he found, but named Lord Sandwich

as the real wrongdoer. One of the judges, Lord Mansfield, observed

that Lord Sandwich was not before the Court. Erskine replied:

“ I know that he is not formally before the Court, but for that

very reason I will bring him before the Court. . . . I will drag

him to light, who is the dark mover behind this scene of

iniquity.”

The libel charges were dismissed and Captain Baillie was even

tually reinstated.

21

Under this section, the lower court is empowered to tax

costs against appellant only upon a proper finding that

he so multiplied the proceedings as to increase costs “unrea

sonably and vexatiously.” But courts have applied the sec

tion rarely and only when the attorney’s conduct in the

litigation was found to be intentionally vexatious.

In Weiss v. United States, 227 F. 2d 72 (2d Cir. 1955),

an attorney who brought four similar and unsuccessful ac

tions to collect the proceeds of government life insurance

policies, was merely warned by the Court that “ further

vexatious litigation to reopen this hopeless case will sub

ject the counsel personally to the cost thereof, as provided

in 28 U. S. C., §1927.” Similarly in Coyne and Delaney Co.

v. G. W. Onthank Co., 10 F. R. D. 435 (S. D. Iowa 1950),

the court construed §1927 as requiring a clear showing of

an intent “ to knowingly and deliberately” increase costs.

In Brislin v. Killanna Holding Corporation, 85 F. 2d 667

(2d Cir. 1936), the court affirmed the trial judge’s refusal

to award costs against an attorney who extended the rec

ord to an “ inordinate length.” Even where an attorney de

layed dismissal until the eve of trial, a court refused to

construe the predecessor of §1927 to permit assessing de

fendant’s costs of procuring expert witnesses. Bone v.

Walsh Construction Co., 235 Fed. 901 (S. D. Iowa 1916).

In Toledo Metal Wheel Co. v. Foyer Bros. <& Co., 223

Fed. 350 (6th Cir. 1915), costs were permitted against

an attorney, but only on a finding that his conduct during

the taking of depositions was “ obnoxious to the orderly,

reasonable, and proper conduct of an examination” ; and in

Motion Picture Patents Co. v. Steiner, 201 Fed. 63 (2d Cir.

1912) costs were allowed defendant in a patent suit pro

longed several months after the plaintiff’s attorney had

officially surrendered his interest in the patent.

22

There is simply no reasonable relationship between the

standards set by §1927, the facts in the cases where the

section has been applied, and the appellant’s conduct. Com

parison accentuates the appropriateness of appellant’s con

duct, emphasizes his innocence of any impropriety or wrong

doing, and compels the conclusion that the order of the court

below should be reversed.

5. Appellant in this situation was entitled to judicial

protection rather than punishment.

The order assessing costs denies to appellant the pro

tection of the court to which appellant acting properly under

difficult conditions was entitled. While appellant owes and,

respectfully submits, performed the duties of honesty and

candor to the court, it is equally the duty of the court to pro

tect appellant’s independence in this case. In Cammer v.

United States, 350 U. S. 399, 407 (1956) the court stated:

“ The public have almost as deep an interest in the inde

pendence of the bar as of the bench.”

This is no new principle. A century earlier, the Supreme

Court in Ex Parte Secombe, 19 How. 9, 13 (1857), speak

ing through Chief Justice Taney, made clear that the power

of the Court to determine the qualifications of attorneys:

“ . . . is not an arbitrary and despotic one, to be exer

cised at the pleasure of the Court, or from passion, prej

udice, or personal hostility; but it is the duty of the

Court to exercise and regulate it by a sound and just

judicial discretion, whereby the rights and indepen

dence of the bar may be as scrupulously guarded and

maintained by the Court, as the right and dignity of

the Court itself.”

In short, the duty of the court toward members of the

bar as stated in In Be Stern, 121 N. Y. S. 948 (1910), “ is not

only to administer discipline to those found to be guilty

23

of unprofessional conduct, but to protect the reputation of

those attacked upon frivolous or malicious charges.”

Applying these principles here imposes on the court be

low the duty to recognize that appellant is representing

a difficult and unpopular cause, that most members of the

Bar of Mississippi will not take such cases, and that if un

checked by the courts the hostility of the state and the com

munity toward those who do is likely to result in situations

similar to the one in which appellant now finds himself.

Appellant seeks here no special privilege or favor because

he represents civil rights litigants. He fully realizes and

accepts the problems inherent in such litigation in Missis

sippi. In a similar situation, great public indignation was

expressed against Erskine in 1762 for daring to defend

Thomas Paine for publishing the Rights of Man. Erskine

said:

“ In every place where business or pleasure collects the

public together, day after day, my name and character

have been the topics of injurious reflection. And for

what? Only for not having shrunk from the discharge

of a duty which no personal advantage recommended,

and which a thousand difficulties repelled.” Parry,

The Seven Lamps of Advocacy, p. 30 (1923).

Appellants suggests that it is the duty of the court to

recognize his position, and to protect him from the malicious

harassment of those who would see the cause he represents

fail.

24

II.

The Vindication of Civil Rights Through Legal Proc

esses Will Be Seriously Restricted Unless the Unreason

able Standard of Professional Conduct Imposed by the

Court Below Is Set Aside.

To tax costs for this disciplinary proceeding on the

grounds of the order below would be unreasonable and an

abuse of judicial discretion in the ordinary case. But a

Mississippi Negro attorney who serves as counsel in a

public school desegregation suit in a rural county, does

not have just an ordinary case. The failure of the court

below to recognize the exceptional nature of the litigation

in which appellant is involved not only magnifies the un

fairness of the decision as to him, but imposes a standard

of professional conduct which in the field of civil rights

can be met only at the expense of rights which litigants

were found to have in NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415

(1963).

The State of Mississippi, 10 years after the Supreme

Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S.

483 (1954), remains committed to a policy of complete

racial segregation in its public schools. Evers v. Jackson

Municipal Separate School District, 328 F. 2d 408 (5th Cir.,

1964); Meredith v. Fair, 298 F. 2d 696 (5th Cir., 1962). The

State’s Constitution requires school segregation, its stat

utes forbid enrollment of any child in a school unless assign

ment is in accord with state statutes (§6334-11 Miss. Code

1942 Annot.), make attendance at an integrated school a

crime (§6220.5 Miss. Code 1942 Annot.), and demand that

the entire executive branch of government prohibit school

desegregation by any “ lawful, peaceful and constitutional

means” (§4065.3 Miss. Code 1942 Annot.).

25

Undoubtedly because of the state’s policy, appellant is

one of the few attorneys licensed to practice in the State of

Mississippi who will accept a “ civil rights” case.6 An addi

tional factor might well be the tremendous pressures ex

erted on persons who seek through litigation the vindication

of legal rights to desegregated public schools and the re

sulting difficulties for any attorney representing them. Such

pressures and difficulties are amply set forth in the record

of this proceeding:

1. In February 1962, 53 Negro parents residing deep in

a rural section of Mississippi petitioned the Board of Edu

cation to assign their children to schools without regard to

race (R 6). The Board failed even to acknowledge receipt

of their petition (R 65, 83), but many of the petitioners who

were sharecroppers living on land owned by whites were

pressured into withdrawing their names from the petition

(R 245). One petitioner who worked for a white woman

withdrew, reportedly under similar pressure (R 245).

2. The principal of the Negro high school in Leake

County personally wrote each petitioner warning them that

the white community would react adversely to continued

efforts to desegregate the system (R 6), a warning proved

prophetic on the nights of October 4th and 5th when the

homes and buildings of several persons in the Negro com

munity, including some of the plaintiffs, were shot into

(R 225-29; SR 338, 370).

3. The local game warden and the owner of a milk dairy,

two white men with obvious standing in the community,

made efforts to get petitioners to withdraw from the de

6 See generally, 1963 Report of the United States Commission

on Civil Rights pp. 117-119. Also see United States ex rel. Goldsby

v. Harpole, 263 F. 2d 71 (5th Cir. 1959) where this Court noted

that Mississippi lawyers seldom if ever raise the question of racial

discrimination in the selection of Juries. Significantly, appellant

assisted out of state counsel for petitioner in the Goldsby case.

26

segregation effort. These men spoke to Mrs. MeBeth who,

at the time, took comfort in her belief that the two men did

not know who she was (R 261-62).

4. Even after the suit was filed, the pressures did not

stop. Three employees of the R. E. A. (Rural Electrifica

tion Administration, see 7 U. S. C. §901 et seq.), which sup

plies electric power in the area, came to the community

and organized a committee of Negroes, all of whom were

related to Ruthie Nell McBeth’s step-father, to determine

whether the real purpose of the desegregation suit was to

win the return of the Negro school (SR 246-49).

Appellant was well aware of these pressures and exer

cised as much care as he reasonably could to insure that

each individual understood the true nature of the suit, and

that those wishing to withdraw be permitted to do so. There

was never any doubt in the minds of petitioners that they

had abandoned hope of getting Harmony School back, and

were determined to desegregate the schools (R 51,167, 247-

48). All had signed the first petition (R 56-57), and the

retainer agreement (R 76, 178), and all those who chose to

continue were well aware of the object of their efforts and

the difficulties likely to be encountered before their aims

could be achieved.

This was, as far as appellant knew, true in the case of

Ruthie Nell MeBeth. While appellant had not personally

met her, he knew her mother as one of the more militant

members of the Leake County group who had to be per

suaded from signing the retainer form on behalf of her

daughter’s children (R 85). The petitioners who obtained

Mrs. McBeth’s signature on the petition and the retainer

agreement knew that she had read them carefully and that

her comments indicated that she understood and agreed

with the idea of desegregating the schools (R 165-66, 189,

246-47). Her mother, Mrs. Kirkland, was displeased when

27

one of her sharecroppers decided to withdraw (R 243), and

at another point indicated displeasure with appellant’s fail

ure to get the suit filed more quickly (R 217). It is not

surprising then that when Mrs. Kirkland, a few days before

the suit was filed, indicated to a few of the petitioners

that her daughter had decided not to go on, they did not take

her comment seriously and did not report it to appellant.

But, in spite of his care, appellant on April 5, 1963 was

“ shocked” (R 103) and “ embarrassed” (R 129) by the affi

davit of his client denying that he represented her. Obvi

ously, appellant’s predicament that he had tried so hard to

avoid (R 71, 113), was not caused by any lack of diligence

on his part; nor did the uncommunicated decision by Ruthie

Nell McBeth and her mother, Bertha Kirkland, not to pro

ceed further in the desegregation effort lead to this pro

ceeding, for several of the original petitioners reached simi

lar decisions and appellant dropped their names as soon as

he learned of their withdrawal (58, 65). Even after suit

was filed the voluntary dismissal of a plaintiff in a school

desegregation suit is not unique.7 What made the dismissal

of Ruthie Nell McBeth crucial was not her belated decision

to withdraw but the supporting affidavit prepared by the

School Board attorney and moved in open court without

prior notice to appellant. Nevertheless, the effect of the

lower court’s findings that appellant had a duty to volun

teer a complete explanation of the affidavit in court on

April 5th when he had no notice, and in chambers (where he

was on another matter) on April 6th when he was unaware

than an explanation was in order, imposes on an attorney

in a civil rights case the duty of being ever ready to fully

explain, without notice, the professional relationship be

J A plaintiff in Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, Civ._ No. 3379, a companion suit to Hudson v. Leake County,

was dismissed on motion of plaintiff’s counsel a few days before

the McBeth motion was filed.

28

tween himself and each of his clients, even where a client

at the instance of an attorney representing the state has

signed charges which prove to be misleading and false. In

Mississippi, persons involved in civil rights are given

ample opportunity by state officials to sign affidavits dis

claiming such activity.8 It is thus not unreasonable to pre

dict that the duty to explain immediately such affidavits is

likely to reduce rather than increase the number of Missis

sippi attorneys willing to represent clients with cases in the

civil rights field.

Appellant suggests that it was the likelihood of similar

interference in Virginia civil rights cases that led the Su

preme Court in NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) to

strike down laws of that state which, as applied to attorneys

representing civil rights cases, threatened to unreasonably

restrict rights which the Court found to be constitutionally

sanctioned.

The procedures of instituting a school desegregation case

as shown in NAACP v. Button were quite similar to the

procedures followed by appellant here. There was even

evidence in the Button record of persons who had been

plaintiffs in public school suits and who testified that they

were unaware of their status as plaintiffs and ignorant

of the nature and purpose of the suits to which they were

parties. 371 U. S. at 422. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court

concluded that in the civil rights field, “ litigation is not a

technique of resolving private differences; it is a means for

achieving the lawful objectives of equality of treatment by

_ 8 State attorneys produced five affidavits prepared by them and

signed by Negroes alleging that James Meredith in requesting them

to certify as to his character had not told them that such cer

tificates would be used to help obtain his admission to the Uni

versity of Mississippi. The affidavits were introduced at the trial

without notice to Meredith’s counsel, but were given little weight

by this Court. Meredith v. Fair, 305 F. 2d 343, 358-59 (5th Cir.

1962).

29

all government, federal, state and local, for the members

of the Negro community in this country.” 371 U. S. 429.

Civil rights litigation is thus a form of political expres

sion in that “while serving to vindicate the legal rights of

members of the American Negro community, at the same

time and perhaps more importantly, makes possible the

distinctive contribution of a minority group to the ideas

and beliefs of our society. For such a group, association

for litigation may be the most effective form of political

association.” 371 U. S. 431.

Applying these principles to the record here must lead

to a conclusion that the standard of conduct imposed by

the court below will restrict the exercise of constitutional

rights as effectively as the solicitation statutes under review

in NAACP v. Button. And for similar reasons, the order

of the court below punishing appellant by assessing him

with costs for failing to adhere to this unreasonable stand

ard should be reversed.

30

CONCLUSION

W h e r e f o r e , f o r a l l th e f o r e g o i n g r e a s o n s , a p p e l la n t s u b

m its th a t th e o r d e r o f th e c o u r t b e lo w r e f u s in g to s e t a s id e

a n o r d e r a s s e s s in g h im w ith c o s t s in th is p r o c e e d in g s h o u ld

b e r e v e r s e d .

Respectfully submitted,

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

D e r r ic k A. B e l l , Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

W i l l i a m R. M in g , J r .

G eorge N. L e ig h t o n

123 West Madison Street

Chicago 2, Illinois

J a c k H . Y o u n g

C a r s ie A. H a l l

115% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

Attorneys for Appellant

Louis H. P o l l a k

Of Counsel

31

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that I have this day of May, 1964

served three copies of the foregoing Brief for Appellant

upon the Honorable L. Arnold Pyle, Counsel for the court

below, Suite 1347, Deposit Guaranty Bank Building, Jack-

son, Mississippi, by depositing same in the United States

mail, airmail, postage prepaid, addressed to him as shown

above.

Attorney for Appellant

38