Chisom v. Roemer Reply Brief for Petitioners Ronald Chisom, et al

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Chisom v. Roemer Reply Brief for Petitioners Ronald Chisom, et al, 1990. 19dd427a-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f525874f-ddb0-4091-bd1e-01c6f26e7619/chisom-v-roemer-reply-brief-for-petitioners-ronald-chisom-et-al. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

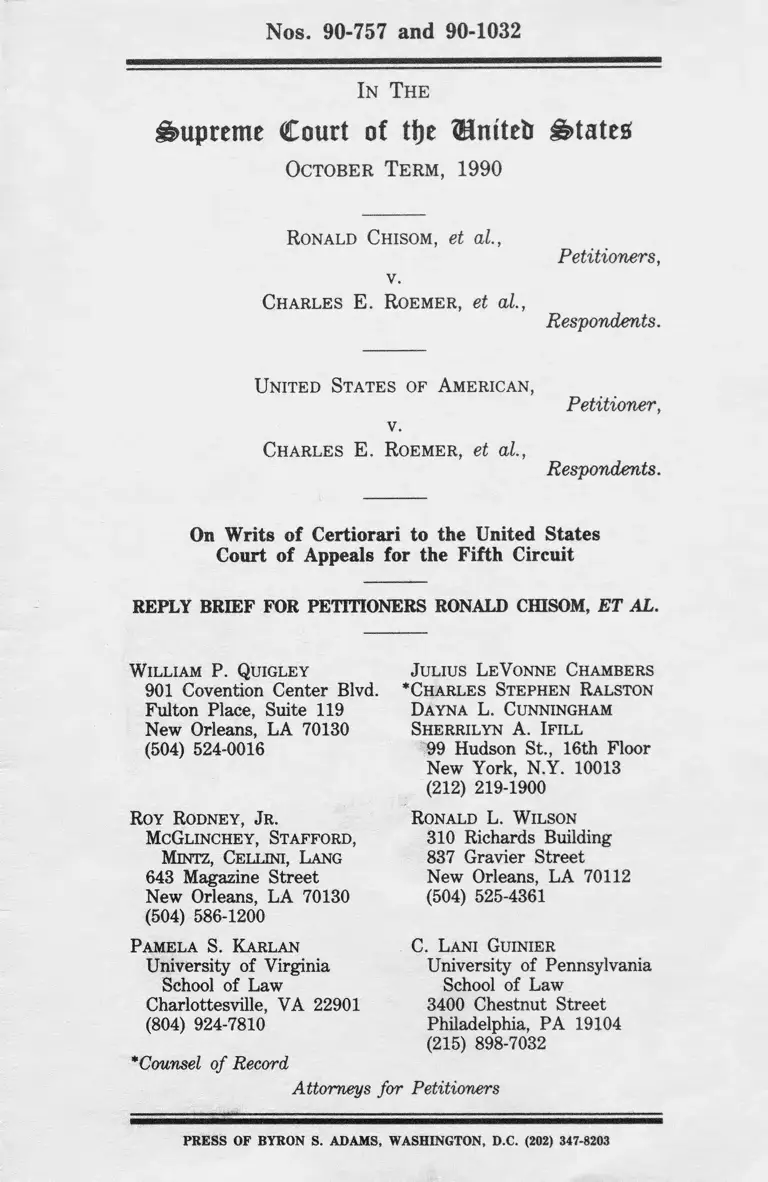

Nos. 90-757 and 90-1032

In The

Supreme Court of ttje ®mte& States

October Term, 1990

Ronald Chisom, et a l,

v.

Charles E. Roemer, et al.,

Petitioners,

Respondents.

United States of American,

v.

Petitioner,

Charles E. Roemer, et a l,

Respondents.

On Writs of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS RONALD CHISOM. ET AL.

William P. Quigley

901 Covention Center Blvd.

Fulton Place, Suite 119

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 524-0016

Roy Rodney, Jr.

McGlinchey, Stafford,

Mintz, Cellini, Lang

643 Magazine Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1200

Pamela S. Karlan

University of Virginia

School of Law

Charlottesville, VA 22901

(804) 924-7810

*Counsel of Record

Julius LeVonne Chambers

’Charles Stephen Ralston

Dayna L. Cunningham

Sherrilyn A. Ifill

99 Hudson St., 16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Ronald L, Wilson

310 Richards Building

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 525-4361

C. Lani Guinier

University of Pennsylvania

School of Law

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

(215) 898-7032

Attorneys for Petitioners

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

1

Table of Contents

Page

Table of Contents ........................................... i

Table of Authorities ......................................... iii

Introduction ...................................................... 1

I. Congress Has Decisively Rejected

Respondents’ Distinction Between

Purposeful and Nonpurposeful

Discrimination ...................................... 2

II. The Language and Structure of the

Voting Rights Act, Taken as a

Whole, Compel the Conclusion

that Section 2 Covers Judicial

Elections ................................... 4

III. Section 2’s Use of the Word

"Representatives" Does Not

Exclude Judicial Elections .................. 5

A. Elected State-Court Judges Can

Reasonably Be Viewed as

"Representatives" .................... 5

11

Page

B. Congress’ Use of the Word

"Representatives" Was Not

Intended to Exempt Judicial

Elections from Section 2 . . . . . 9

C. Congress’ Expressed Intentions

Are Fully Consistent with

Including Judicial Elections

Within the Scope of Section 2 . 12

IV. Respondents Fundamentally Misconstrue

the First Prong of Thornburg v.

Gingles .................................................... 14

V. Respondent’s Brief Advances Arguments

Irrelevant to the Question Presented

in this Case ...................................... 18

Conclusion 23

Ill

T a b l e o f A u t h o r it ie s

Page

Cases

Batson v. Kentucky, 478 U.S. 79 (1986) . . . . 22

City of Mobile v. Bolden, 445 U.S, 55

(1980) 2

City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S.

156 (1980) 15

LULAC v. Clements, 914 F.2d 620 (5th Cir.

1990) (en banc), cert, granted sub nom.

Houston Lawyers’ Ass’n v. Attorney

General of Texas, No. 90-813 3,5,7

Powers v. Ohio, 59 U.S.L.W. 4268

(1991) 13,22

Sugarman v. Dougall, 413 U.S. 634 (1973) . . 6

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30

(1986) 2,12,14-15,16

West Virginia University Hospital v. Casey,

59 U.S.L.W. 4180 (1991) 4,12

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973) 9

Statutes Page

Age Discrimination in Employment Act,

42 U.S.C. § 630 ................. .. 7

Voting Rights Act of 1965, § 2, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973 passim

Voting Rights Act of 1965, § 11, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973i 4-5

Voting Rights Act of 1965, § 14, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973/ 8,10,11

Other Materials

Brief for Respondents, Gregory v. Ashcroft,

No. 90-50 .................................. ......... . . . . 7

S. Rep. No. 97-417 (1982) 12,18,19

Transcript of Oral Argument, Gregory v.

Ashcroft, No. 90-50 8

iv

No. 90-757

In The

Supreme Court o( tfte ®mtcb States

October Term , 1990

Ronald Chisom , et al. ,

Petitioners,

v,

Charles E. Roemer, et al.,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Introduction

The wisdom of Louisiana’s decision to select the

members of its Supreme Court by popular election is not

subject to review by this Court. What is subject to federal

judicial oversight is the process by which that election

occurs. The sole question presented by this case is

whether section 2 permits African-American voters to

2

challenge judicial election systems that deny them an equal

opportunity to participate in the process of choosing

judges, even when that denial is not the consequence of

purposeful discrimination.

I. C o n g r e s s H a s D e c i s i v e l y R e j e c t e d

R e s p o n d e n t s ’ D i s t i n c t i o n B e t w e e n

P u r p o s e f u l a n d N o n p u r p o s e f u l

D is c r im in a t io n

As this Court recognized in Thornburg v. Gingles, 478

U.S. 30, 43-44 (1986), the 1982 amendment to section 2

"[fjirst and foremost . . . dispositively rejects the position

of the plurality in Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980),

which required proof that the contested electoral practice

or mechanism was adopted or maintained with the intent

to discriminate against minority voters." Respondents’

argument to the contrary-that under subsection 2(a), the

intent requirement "remains unchanged," Brief for

Respondents at 17-goes beyond even the bounds of

overzealous advocacy. The so-called "results" test is

expressly contained in subsection 2(a), as amended in

3

1982.1 The placement of the "results" language in

subsection 2(a) also undermines completely another

suggestion advanced by the court of appeals and

respondents: that section 2 can be disaggregated into two

separate tests, one of which governs judicial elections and

the other of which does not. See LULAC v. Clements, 914

F.2d at 625 & 628-29; Brief for Respondents at 17-19.

The language of section 2 provides no warrant for holding

a particular practice vulnerable to attack if it is

purposefully discriminatory but immune from attack if it is

not. Both the court below and respondents concede, as

they must, that section 2 bars Louisiana from adopting or

maintaining a judicial election system for the purpose of

diluting the voting strength of Orleans Parish’s African-

American citizen. See LULAC v. Clements, 914 F.2d 620,

625 & n. 6 (5th Cir. 1990) (en banc); Brief for

Respondents at 1, n.l, and 16. Given that concession and

the structure of section 2, they have absolutely no basis for

'indeed, the word "results" does not even appear in subsection

2(b), where respondent suggests it is located. Brief for Respondent

at 17.

4

claiming that the results test is not similarly broad in its

coverage.

II. T h e L a n g u a g e a n d St r u c t u r e o f t h e V o t in g

R ig h t s A c t , T a k e n a s a W h o l e , C o m p e l t h e

C o n c l u s io n t h a t Se c t io n 2 C o v e r s Ju d ic i a l

E l e c t io n s

The language of section 2 is unconditional in its

prohibition of practices that result in a denial or

abridgement of minority voting rights:

"No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting

or standard, practice, or procedure shall be

imposed or applied by any State . . . in a manner

which results in a denial or abridgement of the

right of any citizen of the United States to vote

on account of race or color . . . ."

42 U.S.C. § 1973(a) (emphasis added). When a statute

contains such unambiguous language, courts construing the

statute’s reach must not contract its scope. See West

Virginia University Hospitals v. Casey, 59 U.S.L.W. 4180,

4184 (1991) (No. 89-994). Had Congress meant to confine

section 2’s reach to certain elective offices only, it certainly

knew how to do so. Section 11(c) of the Act, for example,

is limited to elections held solely or in part to fill seven

5

expressly enumerated positions. 42 U.S.C. § 1973i(c).

Section 2, by contrast, contains no such exclusion.

III. Se c t io n 2 ’s U s e o f t h e W o r d

"Re p r e s e n t a t iv e s " D o e s N o t Ex c l u d e

Ju d ic i a l E l e c t io n s

The linchpin of respondents’ argument lies in their

claim that Congress used the word "representatives"

intentionally to exempt judicial elections from scrutiny

under section 2. That argument fails for two independent

reasons: first, the word "representatives" can permissibly

be read to include elected state-court judges; second, there

is no evidence, either in the statute itself or in the

legislative history that Congress chose the word

"representatives" to restrict section 2’s scope.

A. Elected State-Court Judges Can Reasonably Be

Viewed as "Representatives"

Contrary to the assertion made by the court below

and respondents, see, e.g., LULAC, 914 F.2d at 628; Brief

for Respondents at 23-29, the word "representatives" does

6

not unambiguously exclude elected state-court judges.

That the word "representative" is not equivalent to the

term "servant of a constituency" is clear. Jurors, as we

have already pointed out, are "representatives" of the

community, even though they are sworn to be impartial.

See Brief for Petitioners at 56-62.

Moreover, this Court has recognized that state-court

judges perform a central function in representative

government. In Sugarman v. Dougall, 413 U.S. 634 (1973),

Justice Blackmun, writing for eight members of the Court,

recognized that "persons holding state elective or

important nonelective executive, legislative, and judicial

positions . . . perform functions that go to the heart of

representative government." Id. at 647 (emphasis added).2

Thus, this Court should construe the word

"representatives" in subsection 2(b) to refer to officials who

exercise a function central to the administration of a

2Although then-Justice Rehnquist dissented from the Court’s

holding in Sugarman-that a New York statute barring nonresident

aliens from civil services jobs was unconstitutional-he, too, recognized

that "policy-making for a political community” involved, among other

people, "judges," Sugarman, 413 U.S. at 661 (emphasis added).

7

representative form of government.

Finally, the states themselves have acknowledged that

the function state-court judges perform is in many relevant

respects identical to the functions performed by officials in

the other branches of government. A particularly salient

example is presented by the position taken by the state of

Missouri (with the support of 15 other states as amici

curiae) in Gregory v. Ashcroft, No. 90-50. In that case,

Missouri has argued that its judges, who are subject to

retention elections, are policy-making officials within the

meaning of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act, 29

U.S.C. § 630(f): "Judicial decision making . . . is an

expression of public policy, no less, and perhaps more,

compelling than the modes of expression available to the

legislative and executive branches of government." Brief

for Respondent at 19, Gregory v. Ashcroft, No. 90-50;3 see

3Ironically, in Houston Lawyers’ Ass’n v. Attorney General of Texas,

Missouri and many of the same states that supported its claims that

judges were clearly elected officials and state policy-makers, take the

position as amici supporting the state of Texas that judges are not

"really" elected, or are not "really" policy-making officials. It is hard

to know what sense to make of this abrupt about-face, but it certainly

casts substantial doubt on the importance of the states’ interests in

8

also, e.g., Transcript of Oral Argument at 30 ("The list of

decisions from [Missouri] courts that have outlined and

defined the common law and set the policy for the State

of Missouri is endless"); id. at 38 (explaining that the

judges involved are also "elected officials" within the

meaning of the ADEA because they "do answer to the

voters").4 In light of the day-to-day functions performed

by state-court judges, respondents’ reliance in this case on

statements by various courts and commentators regarding

the nonrepresentative role played by federal courts, see,

e.g., Brief for Respondents at 25 & 32 (quoting Northern

Pipeline Co. v. Marathon Pipe Line Co., 458 U.S. 50, 58, 60

(1982), Mistretta v. United States, 488 U.S. 361, 407 (1989),

the late Alexander Bickel, and Robert Bork), is sadly off

retaining at-large election systems for judges when such systems would

be subject to attack if they involved any other office when the states

cannot even agree whether judges are in fact different from other

officials. Quite frankly, it suggests the states’ purported interests are

rather tenuous or pretextual.

4Every court to have addressed the question has held that judges

who initially obtain office through popular elected are exempted from

the ADEA because they are "persons elected to public office," 29

U.S.C. § 630(f), a phrase whose language tracks in pertinent part the

language of section 14(c)(1) of the Voting Rights Act.

9

the mark.

B. Congress’ Use of the Word "Representatives"

Was Not Intended to Exempt Judicial Elections

from Section 2

Petitioners recognize, of course, that although the

word "representatives" clearly can include judges, there are

circumstances under which it might be used in a more

restrictive fashion. For example, large parts of Title 2 of

the United States Code use the word "Representatives" to

refer solely to members of the lower house of the United

States Congress or in contrast to "Senators." No one,

however, contends that Congress used the word

"representatives" in section 2 to restrict its scope to

members of the United States House of Representatives,

or even to members of the lower house of bicameral

legislative bodies. Everyone agrees that county

commissioners and school board members are covered by

section 2. Indeed, Congress’ use of the word

"representatives" rather than the word used by this Court

in White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973)-"legislatorsM-

10

shows that Congress intended for section 2 to reach more

than simply elections for members of the legislative branch

of state governments.

Congress’ express intention, therefore, was to cover

elections beyond those for legislators. The interchangeable

words used by Congress, in the statute and in the

legislative history, to refer to the positions within the

purview of section 2--"representatives," "candidates,"

"elected officials," "officeholders," and the like, see Brief for

Petitioners at 41-42; Brief for the United States at 27-30-

provide no basis for distinguishing those non-legislative

offices that are primarily executive in nature and those

that are predominantly judicial. Section 2’s language

tracks precisely the terminology used in the definitional

provision of the Act-section 14(c)(l)-which, as we

explained in our opening brief, unambiguously includes

judges. Section 14(c)(1) extends the Act’s reach to

elections for all "candidates for public . . . office." 42

U.S.C. § 1973/(c)(l) (emphasis added). Similarly, section

2 provides, in delineating the results test, that "[t]he extent

11

to which members of a protected class have been elected

to office" is one circumstance to be considered in deciding

whether the plaintiffs’ voting rights have been violated. 42

U.S.C. § 1973(b) (emphasis added). It would have made

no sense for Congress to have viewed the extent to which

minority group members have been elected to judicial

office as a relevant circumstance5 in assessing a section 2

claim if such elections were not covered by the statute.

Moreover, the immediate juxtaposition of the words

"representatives" and "office" shows how Congress used

these terms interchangeably to refer to all officials holding

elective positions.

Given the categorical language used both in section 2

and in section 14(c)(1), this Court should be especially

reluctant to imbue the word "representatives" with a

restrictive meaning in the complete and utter absence of

5That Congress saw minority electoral success in judicial elections

as a significant indicator is shown by its repeated references to the

number of elected African-American and Hispanic jurists in the

legislative history of the 1970, 1975, and 1982 amendments and

extensions of the Voting Rights Act. See Brief for Petitioners at 37-

39; Brief for the United States at 31.

12

any explicit or implicit indication of a congressional

purpose to adopt such a meaning. That various policy

concerns might have led Congress to have exempted

judicial elections from coverage under section 2 "had it

thought about it," West Virginia University Hospital, 59

U.S.L.W. at 4184, cannot justify this Court’s judicial

construction of such an exemption through a tortured

reading of the statutory language.

C. Congress’ Expressed Intentions Are Fully

Consistent with Including Judicial Elections

Within the Scope of Section 2

The central goal of the Voting Rights Act and its

extensions and amendments has been "to create a set of

mechanisms for dealing with continuing voting

discrimination, not step by step, but comprehensively and

finally." S. Rep. No. 97-417, p. 5 (1982) [hereafter cited as

"Senate Report"].6 Any comprehensive and final

resolution of the problem of race discrimination in voting

"This Court has recognized the "authoritative" nature of the 1982

Senate Report in discerning Congress’ intent. Thornburg v. Gingles,

478 U.S. 30, 43 n. 7 (1986).

13

must reach race discrimination in the mechanisms used to

elect judges for, as this Court reiterated a fortnight ago,

"[t]he Fourteenth Amendment’s mandate that race

discrimination be eliminated from all official acts and

proceedings of the State is most compelling in the judicial

system." Powers v. Ohio, 59 IJ.S.L.W. 4268, 4272 (1991)

(No. 89-5011).

As Powers recognized, the two "most significant

opportunities] to participate in the democratic process"

enjoyed by most citizens are voting and jury service. Id. at

4270. But just as racial discrimination in the selection of

jurors "offends the dignity of persons and the integrity of

the courts," id. at 4269, so, too, with racial discrimination

in the election of judges. To permit states to use systems

for electing judges that deny African-Americans an

effective voice tells African-American citizens that their

views regarding who should sit in judgment over the entire

community are not worthy of the respect accorded the

views of white voters, thereby denying African-Americans

equal dignity. Moreover, it cannot help but breed cynicism

14

regarding the fairness of the judicial system as a whole to

have a bench so overtly unrepresentative of the community

whose power it exercises.

Nothing in the language or legislative history of the

Voting Rights Act supports excluding judicial elections

from coverage under section 2. In light of the

unconditional ban on discriminatory voting mechanisms,

the inclusionary language, and the clear congressional

purpose to abolish all racial discrimination in voting, the

most logical and defensible reading of section 2 would

reach the kind of discrimination alleged in this case.

IV. R e s p o n d e n t s F u n d a m e n t a l l y M is c o n s t r u e

t h e F ir s t P r o n g o f T h o r n b u r g v . G in g l e s

In Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. at 48 (emphasis

added), this Court identified three circumstances which

"generally'' must be shown to prove a claim of "vote

dilution through submergence."7 The first of these factors

7Nothing in the Gingles opinion suggests that these three factors

must be established to prove every claim under section 2’s "results"

test. For example, even in a community where there is no racial bloc

voting, the use of registration practices that disproportionately prevent

15

is that "the minority group must be able to demonstrate

that it is sufficiently large and geographically compact to

constitute a majority in a single-member district. If it is

not, . . . the multimember form of the district cannot be

responsible for minority voters’ inability to elect its [y/c]

candidates." 478 U.S. at 50 (emphasis in original). Read

in context, what the first prong of the Gingles test requires

is that plaintiffs challenging a scheme as dilutive show a

causal link between the election practice they challenge

and their inability to elect the candidates of their choice.

Contrary to respondents’ assertion, Brief for

Respondents at 41, the test set out in the first prong of

Gingles does not invariably require presentation of a

hypothetical single-member district complying with

principles of one-person, one vote. Rather, the first prong

African-Americans from voting and thus participating in the political

process is subject to challenge under section 2. Similarly, even in a

community where African-Americans could not form a majority in a

single-member district, the use of an anti-single-shot rule, see, e.g., City

of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156, 184 (1980) (explaining single

shot voting), might be subject to attack under section 2 if the

interaction of that rule with racial bloc voting resulted in the defeat

of African-American candidates who might otherwise win election.

16

of Gingles requires plaintiffs simply to show the existence

of a constitutionally acceptable alternative to the existing

scheme that would provide them with a more equal

opportunity to participate and elect the candidates of their

choice. This is a case-specific question "peculiarly

dependent on the facts in each case," Gingles, 478 U.S. at

79 (internal quotation marks omitted); its contours depend

on the precise aspects and consequences of the election

structure challenged by plaintiffs in their complaint. In the

case of petitioners’ to the scheme for electing the

Louisiana Supreme Court, such an alternative can be

demonstrated by showing that African-American voters are

sufficiently numerous and geographically compact to form

a majority in a district equivalent in population to already

existing Louisiana Supreme Court districts. Thus,

petitioners showed that it would be possible to create a

majority African-American supreme court district that

would be more populous than two of the five existing

single-member Supreme Court Districts. See Pet. App. at

10a. Respondents’ suggestion that without the constraints

17

of one-person, one-vote, there is no judicially discernible

and manageable standard for assessing claims of racial

vote dilution, Brief for Respondents at 43, ignores this

obvious method for assessing plaintiffs’ ability to establish

dilution through submergence.8 Even if states are not

obligated to develop equipopulous districts as a remedy for

racial vote dilution in judicial elections, certainly a showing

that an identifiable group of minority voters has less

opportunity to elect the candidates of its choice than a

similarly numerous group of white voters should satisfy the

first prong of Gingles. See Brief for the United States as

Amicus Curiae Supporting Reversal in Houston Lawyers’

Ass’n v. Attorney General of Texas at 18 ("Group vote

dilution occurs when the practical operation of an electoral

system effectively erases or minimizes the voting strength

of a particular group, such as a racial minority."). As we

discuss in the following section, the remedy issue does not

define the violation, but should be addressed by the trial

sSee infra note 9.

18

court only after a finding of liability.

V. R e s p o n d e n t ’s B r ie f A d v a n c e s A r g u m e n t s

Ir r e l e v a n t t o t h e Q u e s t io n P r e s e n t e d in t h is

Ca s e

Respondents devote a substantial part of their

argument to issues connected with developing a remedy

for a violation of section 2. See Brief for Respondents at

34-39. Those concerns are irrelevant to the question

before this Court: the scope of section 2’s coverage.

First, Congress has clearly provided that a state’s

nondiscriminatory interests cannot trump the compelling

constitutional aim of the Voting Rights Act: to eradicate

racial discrimination in voting. See Senate Report at 29 n.

117 ("even a consistently applied practice premised on a

racially neutral policy would not negate a plaintiffs

showing through other factors that the challenged practice

denies minorities fair access to the process"); id. at 195

(additional views of Sen. Robert Dole, sponsor and drafter

of amended subsection 2(b)) (rejecting the suggestion that

"defendants be permitted to rebut a showing of

19

discriminatory results by a showing of some

nondiscriminatory purpose behind the challenged voting

practice or structure").

That is not to say, of course, that a state’s legitimate

interests are wholly irrelevant to a section 2 case. But the

proper occasion for accommodating those interests is in

fashioning a remedy, not in determining liability. In its

current posture, this case does not present the question

whether any particular remedy is required. Should

petitioners prevail on remand in proving that their voting

rights are being diluted by the present election scheme,

Louisiana will, in the first instance, have the opportunity to

propose a new system that both remedies the denial of

petitioners’ voting rights and serves the state’s legitimate

interests. Such a remedy "necessarily dependfs] upon

widely varied proof and local circumstances," and Congress

has eschewed "prescribing in the statute mechanistic rules

for formulating remedies . . . ." Senate Report at 31.

Thus, remedial concerns cannot form the basis for a

categorical exclusion of judicial elections from coverage

20

under section 2.

Second, the remedial concerns identified in

respondents’ brief are an utter makeweight in this case,

further showing why such concerns cannot justify a

categorical exclusion of judicial elections. For example,

respondents identify as "[pjossibly the most difficult"

problems to solve those related to the creation of

additional judgeships and population changes. Brief for

Respondents at 37. But Louisiana has not added

judgeships to its Supreme Court in this century. Nor has

it changed the judicial election districts for the Supreme

Court since at least 1921. Thus, neither of these

"problems" has any bearing whatsoever on this case.

Louisiana is entirely free to retain its seven-member

Supreme Court. And the inapplicability of one-person,

one-vote to judicial districts frees the state from the need

to redraw its supreme court districts decennially.9

9As we have already explained, the feasibility of creating a majority

African-American district whose population is equivalent to the so-

called "ideal” district size may be relevant to establishing liability, for

it is one way of satisfying the causal nexus test delineated in Gingles.

But it is by no means required that the state’s remedy, should liability

21

The problem of actual or perceived bias if justices are

elected from "much smaller" districts, Brief for

Respondents at 38, is an equally flimsy concern. The

division of the existing First Supreme Court District used

by petitioners at trial to show how the current district

submerged Orleans Parish’s African-American majority in

an overwhelmingly white multimember district would

result, if it were adopted as a remedy, in the creation of

two districts, each have a population of well over half a

million persons, and each having over 100,000 more

residents than one of the existing single-member Supreme

Court Districts. See Pet. App. at 10a.

At their core, the assertions about impartiality

advanced by respondents, see, e.g., Brief for Respondents

at 38 7 49-50, and by the Solicitor General at the tail end

of his brief, see Brief for the United States at 35, are

deeply racially insulting. They suggest implicitly that

supreme court justices selected by African-American voters

be proven, comport with one-person, one-vote. The state remains free

to accommodate other goals, so long as a complete remedy for the

violation of section 2 has been provided.

22

will somehow be less impartial than justices selected by

white voters. Permitting states to defend their existing

judicial election systems by relying on such a pernicious

stereotype is utterly unacceptable. Cf. Powers v. Ohio, 59

U.S.L.W. at 4271 (the equal protection clause forbids using

race as a "proxy for determining juror bias or

competence"); Batson v. Kentucky, 478 U.S. 79, 97 (1986)

(prosecutors may not strike jurors based "on the

assumption . . . or intuitive judgment. . . that they would

be partial to the defendant because of their shared race").

The central premise of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments, as well as of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,

especially as it was amended in 1982, is that African-

American voters are as qualified as white voters to

participate in the process of choosing public officials and

that African-American jurists are are able as their white

counterparts to fulfill their oath of office.

23

C o n c l u s io n

For the foregoing reasons, this Court should reverse

the judgment of the court of appeals and remand this case

for further proceedings consistent with its opinion.

Respectfully submitted,

W illiam P. Quigley

901 Convention Center

Blvd.

Fulton Place, Suite 119

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 524-0016

Roy Rodney, Jr .

McGlinchey, Stafford, '

Mintz, Cellini, Lang

643 Magazine Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1200

Pamela S. Karlan

University of Virginia

School of Law

Charlottesville, VA 22901

(804) 924-7810

*Counsel of Record

Julius LeVonne Chambers

*Charles Stephen Ralston

D ayna L. Cunningham

Sherrilyn A. Ifill

99 Hudson St., 16th Floor

New York. N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Ronald L. W ilson

310 Richards Building

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 525-4361

C. Lani Guinier

University of Pennsylvania

School of Law

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

(215) 898-7032

Attorneys for Petitioners