Memorandum for the United States

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1969

10 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Alexander v. Holmes Hardbacks. Memorandum for the United States, 1969. a490554e-cf67-f011-bec2-6045bdffa665. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f5445087-2627-45a8-a8cc-38a74785afb5/memorandum-for-the-united-states. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

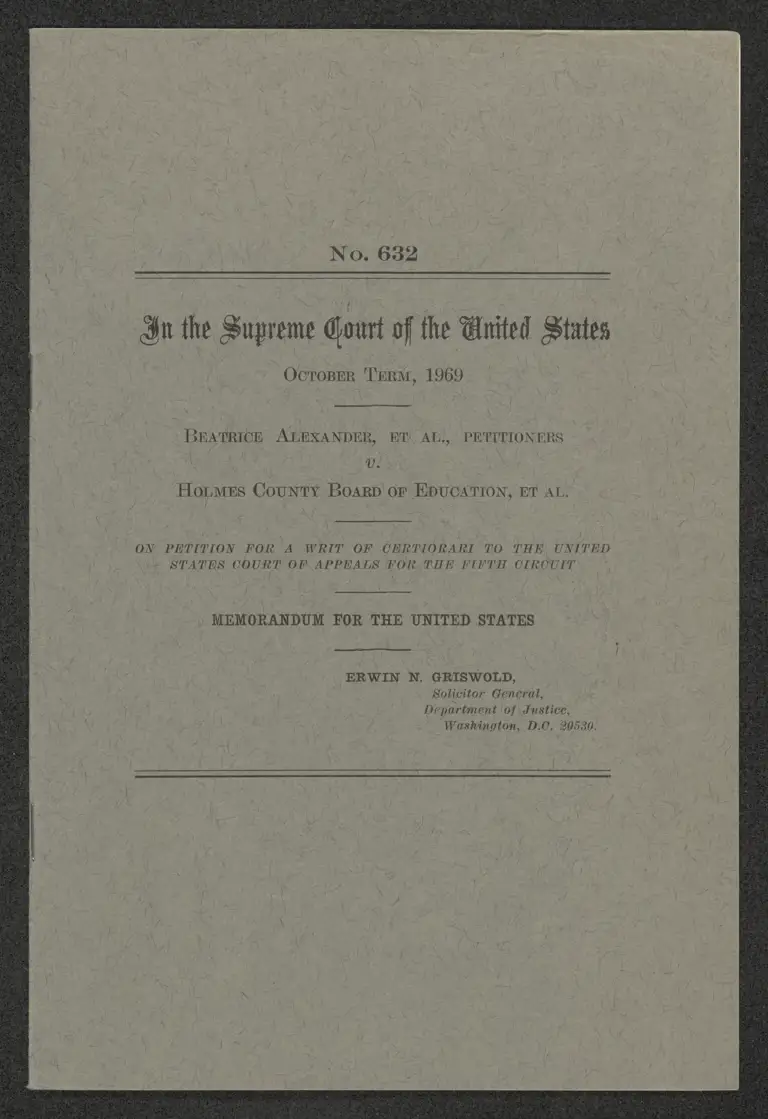

No. 632

Jn the Supreme Gourt of the @nited States

OcToBER TERM, 1969

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, ET AL., PETITIONERS

| v.

HormEs CouNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL.

ON. PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

MEMORANDUM FOR THE UNITED STATES

ERWIN N. GRISWOLD,

: Solicitor General,

Department of Justice,

Washington, D.C. 20530.

/

/

\

} { |

J

i i /

{ ‘J

1

4

q

/ |

|

1

” { {

|

|

\

{

(

Ll

H }

In the Supreme Court of the Wnited States

OctoBER TERM, 1969

No. 632

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, ET AL., PETITIONERS

9,

Hor.mes CouNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL.

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

MEMORANDUM FOR THE UNITED STATES

1. Following this Court’s decision in Green v. Coun-

ty School Board, 391 U.S. 430, these cases, involving

some thirty-three school districts in Mississippi, were

before the United States Court of Appeals for the

Kifth Circuit, in Adams v. Mathews, 403 KF. 2d 181.

Prior to that the district court had approved “freedom

of choice” plans. In the Adams decision, all of these

cases, and others, were reversed, and sent back to dis-

trict courts to determine whether the plans would lead

to “a unitary system in which racial diserimination

would be eliminated root and branch,”” and whether

the proposed changes would produce “a desegregation

plan that ‘promises realistically to work now’ ” (403

HK. 2d at 188).

365-139—69 (1)

2

On remand, the district court again approved the

“freedom of choice’ plans (Pet. App. 1a-23a). The

United States again appealed to the court of appeals,

and an expedited procedure was followed in that

court. The United States asked for orders which

would lead to desegregation in most of the schools

beginning in the fall of 1969. In the proceedings be-

fore the court of appeals, the United States stated its

belief that such plans could be developed and put into

effect within the time available, and the United States

proposed a timetable for the development and imple-

mentation of the plans.

In these proceedings in the court of appeals, the

United States also suggested that the Department of

Justice was not expert in educational administration,

and that better progress might be made if experienced

educators from the Department of Health, Education

and Welfare were brought into the picture.

The court of appeals adopted all of the recom-

mendations of the United States (Pet. App. 28a-37a).

It ordered the district court to formulate plans which

would “disestablish the dual school systems in ques-

tion”’ (Pet. App. 36a). It also ordered the district court

to request “that educators from the Office of Kduca-

tion of the United States Department of Health, Edu-

cation and Welfare collaborate with the defendant

school boards in the preparation of plans” which

would carry out the court’s order (Pet. App. 35a-36a).

Finally, it set up a timetable—admittedly a very tight

one—under which plans should be presented to the

district court by August 11, 1969, for hearing on

August 21, 1969, and to be implemented by the district

3

court no later than August 25, 1969—a date which

was later changed by the court of appeals to Sep-

tember 1, 1969 (Pet. App. 38a).

The Department of Health, Education and Welfare

filed plans by August 11, 1969 (Pet. App. 40a-52a).

On August 19, 1969, Robert H. Finch, Secretary of

Health, Education and Welfare of the United States,

sent a letter to Chief Judge Brown of the court of

appeals, and to the three district judges involved in

the case, requesting the court to grant an extension of

time until December 1, 1969, for the filing of plans

after more thorough study (Pet. App. 53a-54a). The

court of appeals directed the district court to con-

sider this request, and a motion filed by the United

States based on the request, and to make recom-

mendations with respect to it. The distriet court held

a hearing, and recommended that the Secretary’s re-

quest be granted (Pet. App. 56a-70a). This has been

approved by the court of appeals, which has amended

its earlier order, by eliminating the September 1,

1969, deadline, and fixing a new deadline of Decem-

ber 1, 1969 (Pet. App. 71a-78a). The court, at the

suggestion of the Department of Justice, also ordered

each of the Boards, in conjunction with the Office of

Education, to “develop a program to prepare its

faculty and staff for the conversion from the dual to

the unitary system” and to do this by October 1,

1969 (Pet. App. 77a). Finally, also at the suggestion

of the Department of Justice, the Boards were or-

dered not to construct any new facilities “until a

terminal plan has been approved by the Court’ (Pet.

App. 78a).

4

On August 30, 1969, petitioners applied to Mr. Jus-

tice Black for an order vacating the court of appeals’

modification of its previous order. On September 5, 1969,

Mr. Justice Black denied the application (Pet. App.

79a-83a). The petition for a writ of certiorari followed.

2. We agree with much that is said in the petition

for certiorari, and we have no quarrel with the state-

ment in Mr. Justice Black’s opinion in Chambers that

“the phrase ‘with all deliberate speed’ should no

longer have any relevancy whatsoever in enforcing the

constitutional rights” of students to education in a

unitary, desegregated school system (Pet. App. 8la).

The United States did not rely on a concept of “deli-

berate speed” in seeking the extension of time granted

by the court below, and there is nothing in the court of

appeals decision, the district court opinion, or the

motion of the United States that condones any delay

past December 1, 1969, in formulating a terminal de-

segregation plan. Indeed, it has been, and remains, our

understanding that this Court has already indicated

that the “deliberate speed” formula 1s no longer appro-

priate to the remedial aspects of school desegregation

suits and that, instead, school boards today are con-

stitutionally obligated to devise and implement plans

that will accomplish, both “realistically” and “now”,

the conversion of dual, segregated school systems into

unitary, desegregated school systems. Green v. County

School Board, 391 U.S. 430, 438-439, and cases there

cited.

While we believe that it might be useful for this

5

Court to reiterate these governing prineiplesin-anap-—

propriate case, we fail to perceive what relief petition-

erg are seeking from this Court in the present posture

of this matter. The Office of Education of the Depart-

ment of Health, Education and Welfare, in its capac-

ity as a sort of collective “Special Master” assisting

the courts below, is presently proceeding, not with

‘“deliberate speed,” but with dispatch, to formulate the

plans for converting the thirty-three school systems

involved in these consolidated cases to unitary, deseg-

regated systems. In compliance with the order of

the court of appeals, these plans will be submitted

as quickly as possible, In no event later than De-

cember 1, 1969, and will include provisions for “sig-

nificant action toward disestablishment of the dual

school systems during the school year September

1969-June 1970” (Pet. App. 78a).' It cannot now be

_known whether petitioners will deem any of the pro-

visions of these plans to be unsatisfactory in any re-

spect. If they should, they would be entitled to

file their objections or suggested amendments within

fifteen days of the submission of the plans to the dis-

trict court and that court would be required to act

thereon and approve a plan conforming to constitu-

tional standards during the next ensuing fifteen days

(Pet. App. 76a-77a). In the meantime, the Office of

Kduecation has, in compliance with the order of the

The steps which might be taken during the present school

year could include for example, the pairing or zoning of schools

at midterm, teacher reassignments, use of team teaching, imte=

gration of athletic programs and adoption of a midterm pro-

gram to prepare students and the community for total dises-

tablishment of the dual system in the 1970-1971 school year.

6

court below (Pet. App. 77a), reported to that court on

October 1, 1969, with respect to the program which

has been developed to prepare the faculty and staff of

rach school district for conversion from the dual to

the unitary system.

Petitioners do not claim that any of the above-

described provisions of the order of the court of ap-

peals are inappropriate in the present posture of these

ases. They complain, instead, that that court erred in

oranting the government’s request for an extension of

time for the filing of the plans by the Office of Edu-

cation and thereby permitting the current school year

to begin in these districts under constitutionally in-

adequate ‘‘freedom of choice” plans. Obviously, Tiow-

ever, the clock cannot be turned back so as to begin

the school year in any—other—way- The pertine :

tion now, we submit, is not whether, in the extremely

difficult circumstances of late summer, the court be-

low should or should not have granted the extension of

time deemed necessary by the Secretary of Health,

Education and Welfare in order to enable his Depart-

ment realistically and responsibly te make up for the

tragic and frustrating default of the local school offi-

cials in these districts by doing the work which it was

their obligation under the Constitution to have done.”

2 Petitioners correctly state that “the school boards had made

no attempt to solve [the administrative difficulties] in the fif-

teen years since Brown” (Pet. 10). Undeniably, the obligation

to solve those difficulties is immediate and absolute, and the

school boards involved may not profit from their own intransi-

gence. But school systems are run for children, not boards or

courts. If genuine requirements of educational administration

were to be disregarded in providing the remedies for school

boards’ neglect of their duties, the resulting harm would fall on

the very pupils for whom better education through equal oppor-

tunity is sought.

7

The question now is how, in the present circumstances,

the overriding objective of these lawsuits, to which the

United States is firmly dedicated, can be successfully

and expeditiously achieved. We believe that the order

of the court of appeals—formulated in the light of

that court’s close familiarity with these cases and dis-

tinguished experience in this field constitutes an ap-

propriate answer to this question. Petitioners do not

suggest how the order could be improved or how, in

any other respect, the objectives of these lawsuits

would be furthered by this Court’s review of the order

—— nl

at the present stage of these cases.

Accordingly, we suggest the Court should deny EAE 55

certiorari or, alternatively, withhold action on the peti-

tion until the situation Corition, after the scheduled

filing of the plans in December. Si

Respectfully submitted.

Erwin N. GRISWOLD,

Solicitor General.

OCTOBER 1969.

U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1969

J