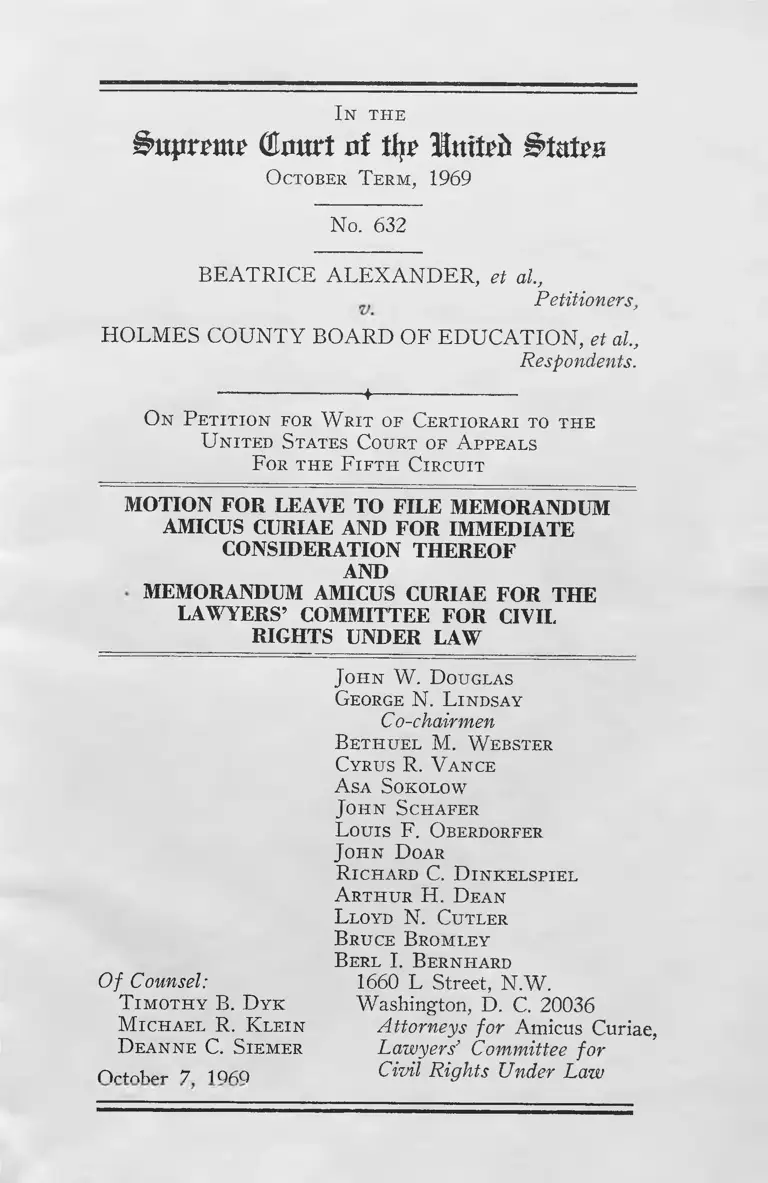

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education Motion for Leave to File Memo Amicus Curiae and Memo for Amicus Curiae the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education Motion for Leave to File Memo Amicus Curiae and Memo for Amicus Curiae the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, 1969. cdb0ed8b-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f59028d6-c8b2-4e75-bbe4-51700e07f51e/alexander-v-holmes-county-board-of-education-motion-for-leave-to-file-memo-amicus-curiae-and-memo-for-amicus-curiae-the-lawyers-committee-for-civil-rights-under-law. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

0ttpmtu' (Emtrt at tip? United States

O ctober T e r m , 1969

No. 632

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, et al,

Petitioners,

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al,

Respondents.

------------------------♦------------------------

O n P e t it io n for W r it of Certio rari to t h e

U n it ed S tates C ourt of A ppea ls

F or t h e F if t h C ir c u it

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE MEMORANDUM

AMICUS CURIAE AND FOR IMMEDIATE

CONSIDERATION THEREOF

AND

MEMORANDUM AMICUS CURIAE FOR THE

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW

J o h n W . D ouglas

George N. L indsay

Co-chairmen

B e t h u e l M. W ebster

C yrus R. V a n c e

A sa S okolow

J o h n S c h a fe r

L o u is F . O berdorfer

J o h n D oar

R ich a rd C. D in k e l s p ie l

A r t h u r H. D ea n

L loyd N. Cu tler

B ruce B rom ley

B erl I. B ern h a r d

1660 L Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae,

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

Of Counsel:

T im o t h y B. D y k

M ic h a e l R. K l e in

D e a n n e C. S ie m e r

OrtnKpr 7 1 Q fiQ

I n t h e

©curt nt tip TUnxtvb

O ctober T e r m , 1969

No. 632

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, et al,

Petitioners,

v.

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Respondents.

--------------------------<.--------------------------

O n P e t it io n for W r it of Certio rari to t h e

U n it ed S tates C ourt of A ppea ls

F or t h e F if t h C ir c u it

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE MEMORANDUM

AMICUS CURIAE AND FOR IMMEDIATE

CONSIDERATION THEREOF

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

hereby respectfully moves for leave to file the attached

Memorandum Amicus Curiae in the above-entitled case.

Petitioners have consented to the filing of this memoran

dum. Respondent United States of America (a plaintiff

below) has also consented. Consents have been requested

from the respondents who are defendants below in the

fourteen cases, but as yet consents from these respondents

have not been received.

Since the responses in this case are due to be filed this

Wednesday, October 8, 1969, and since this Court may

consider this case at this week’s Conference, this motion

and the attached Memorandum Amicus Curiae cannot be

considered by the Court if the non-consenting respondents

are afforded time to respond to this motion under Rule

35(4). Moreover, we believe that their positions on the

merits may be adequately presented in their responses to

the petition for certiorari. Accordingly, applicant respect-

2

fully requests that this motion and the attached Memoran

dum Amicus Curiae be considered together with the pe

tition for certiorari and the responses to the petition, and

that, pursuant to Rule 35(4), consideration of this motion

and the attached Memorandum Amicus Curiae not be post

poned pending receipt of papers in opposition from the non

consenting respondents.

Applicant respectfully submits that the attached Mem

orandum Amicus Curiae will be of assistance to this Court.

The reasons that applicant believes its motion should be

granted are as follows:

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized on June 21, 1963, following a conference of

lawyers at the White House called by President John F.

Kennedy. The formal organization of the Lawyers’ Com

mittee for Civil Rights Under Law is that of a non-profit

private corporation whose principal purpose is to involve

private lawyers throughout the country in the struggle to

assure all citizens their civil rights. The membership of

the Committee includes eleven past presidents of the

American Bar Association and two former Attorneys

General.

Since 1964, the Committee has operated a law office in

Jackson, Mississippi, which has handled more than 2,000

civil rights cases. Over 150 attorneys from all parts of the

United States have served as unpaid volunteers in the Jack-

son office in aid of the permanent staff there. The Com

mittee’s national and local offices have actively engaged the

services of the private bar in addressing a range of legal

problems in such areas as education, housing, employment,

economic development, and the administration of justice.

In the field of education, both the national staff and the local

committees have undertaken well over a score of projects to

promote quality education and to assure its availability to

all citizens, regardless of income level or race. The Com

mittee has recently renewed its offer to assist the Depart

ment of Justice in carrying out national objectives in the

civil rights area.

3

In the two weeks which have passed since the filing of

the petition for certiorari, federal officials charged with

enforcement responsibilities in this field have placed in ques

tion the capacity of the federal government to enforce an

order for immediate desegregation. The Lawyers’ Com

mittee for Civil Rights Under Law, in the attached memo

randum, deals directly with this most relevant issue which

is not presented in the petition for certiorari. Moreover,

applicant deals with an additional question—not fully

treated in the petition—-whether community opposition is an

adequate ground for delay in enforcement.

Accordingly, the Committee respectfully requests that

this Court grant leave to file the attached Memorandum

Amicus Curiae, and consider this motion and the Memoran

dum together with the petition and responses.

Respectfully submitted,

J o h n W . D ouglas

George N. L indsay

Co-Chairmen

B e t i-iu e l M. W ebster

Cyrus R. V a n c e

A sa S okolow

J o h n S c h a fe r

L o u is F. O berdorfer

J o h n D oar

R ich ard C. D in k e l s p ie l

A r t h u r H. D ean

L loyd N. Cu tler

B ruce B rom ley

B erl I. B ern h a rd

1660 L Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

Of Counsel:

T im o t h y B. D y k

M ic h a e l R. K l e in

D e a n n e C. S ie m e r

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae,

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

October 7, 1969

I n t h e

OXrrurt of tljo H&txxtvb &t<xhss

O ctober T e r m , 1969

No. 632

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, et al,

Petitioners,

v.

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Respondents.

.---------- ---------- ♦------------------------

O n P e t it io n for W r it of Certio ra ri to t h e

U n it ed S tates Court of A ppeals

F or t h e F if t h C ir c u it

------------------------ * ---------------------- —

MEMORANDUM AMICUS CURIAE'

FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether, fifteen years after this Court’s decision in

Brown v. Board of Education, enforcement of elementary

school desegregation in the State of Mississippi should be

further delayed.

INTEREST OF THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized on June 21, 1963, following a conference of

lawyers at the White House called by President John F.

Kennedy. The formal organization of the Lawyers’ Com

mittee for Civil Rights Under Law is that of a non-profit

private corporation whose principal purpose is to involve

private lawyers throughout the country in the struggle to

assure all citizens of their civil rights. The membership of

the Committee includes eleven past presidents of the Amer

ican Bar Association and two former Attorneys General.

Since 1964, the Committee has operated a law office in

Jackson, Mississippi, which handled more than 2,000 civil

2

rights cases. Over 150 attorneys from all parts of the United

States have served as unpaid volunteers in the Jackson

office in aid of the permanent staff there. The Committee’s

national and local offices have actively engaged the services

of the private bar in addressing a range of legal problems in

such areas as education, housing, employment, economic

development, and the administration of justice. In the field

of education, both the national staff and the local com

mittees have, undertaken well over a score of projects to

promote quality education and to assure its availability to

all citizens, regardless of income level or race. The Com

mittee has recently renewed its offer to assist the Depart

ment of Justice in carrying out national objectives in the civil

rights area.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

The Time for Additional Delay in

School Desegregation Is At An End.

This is not the first time elements of the school system

of the State of Mississippi have appeared before the federal

courts in matters of school segregation. In the fifteen years

since the first Brown decision, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), at

least fourteen decisions involving- Mississippi school segre

gation have been rendered by federal courts.1 Nearly all

1United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate School Dist., 410

F. 2d 626 (5th Cir. 1969) ; Anthony v. Marshall County Bd. of

Educ., 409 F. 2d 1287 (5th Cir. 1969) ; Henry v. Clarksdale Muni

cipal Separate School Dist., 409 F. 2d 682 (5th Cir. 1969) ; United

States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School Dist., 406 F. 2d

1086 (5th Cir. 1969) ; Adams v. Mathews, 403 F. 2d 181 (5th Cir.

1968) ; United States v. Hinds County School Bd., 402 F. 2d 926

(5th Cir. 1968) ; Singleton v. Jackson Muncipal Separate School

Dist., 348 F. 2d 729 ( 5th Cir. 1965) ; United States v. Madison

County Bd. of Educ., 326 F. 2d 237 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 379

U. S. 929 (1964) ; Meredith v. Fair, 313 F. 2d 532 (5th Cir. 1962),

cert, denied, 372 U. S. 916 (1963) ; Meredith v. Fair, 313 F. 2d

534 (5th Cir. 1962) ; Coffey v. State Educational Finance Comm’n,

296 F. Supp. 1389 (S. D. Miss. 1969) ; Franklin v. Quitman County

Bd. of Educ., 288 F. Supp. 509 (N. D. Miss. 1968) ; United States

v. Natchez Special Municipal Separate School Dist., 267 F. Supp.

614 (S. D. Miss. 1966); United States v. Biloxi Municipal School

Dist., 219 F. Supp. 691 (S. D. Miss. 1963), aff’d, 326 F. 2d 237

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 379 U. S. 929 (1964).

3

have issued the same unmistakable declarations: Segrega

tion must end, good faith compliance with this Court’s

decision in Brown—which as an interpretation of the

Fourteenth Amendment is “the supreme law of the land”2-—

is constitutionally required.

As the record painfully reveals, however, good faith

compliance h^notbegm forthcoming. Five thousand six

hundred and /days have passed since this Court’s

landmark decision in 1954. For those fifteen years the

school systems in Mississippi have failed to effect good

faith compliance. If one lesson has been learned during

these past fifteen years, it is that the ingenuity of the

officials of the Mississippi school system should not be

underestimated. Now, on the eve of the first meaningful

elementary school desegregation in the State’s history, the

defendants have apparently succeeded in convincing the

Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, who in turn,

has convinced the District Court, that further delay should

be afforded because:

“The administrative and logistical difficulties which

must be encountered and met in the terribly short

space of time remaining must surely . . . produce

chaos, confusion and catastrophic educational set

back___ ”3

The ring is familiar if the source is not.

The Secretary’s reference is to the defendant’s assertion

that the petitioners’ constitutional rights must await (1)

the redrawing of bus routes, (2) the reassignment of

teachers, (3) the conversion of classrooms and (4) a pro-

2Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 18 (1958).

3Letter of Secretary Finch to the Court of Appeals and the judges

of the District Court. Transcript of Record in the Court of Appeals,

Vol. IV, Document No. YY, Exhibit 2.

4

gram of preparation of the teachers and students involved.4

This fourth ground appears to be a euphemism for over

coming community resistance.

The supposed administrative and logistical difficulties

asserted in support of the request for a further delay are

wholly inadequate, particularly in the light of the long

delay already encountered.5 There is nothing in the record

to demonstrate that the redrawing of bus routes could take

more than a few days. Even assuming that the second and

third reasons (reassignment of teachers and the conversion

of classrooms) will involve difficulties of substance for the

school boards involved, it is scarcely credible that they out

weigh the long overdue promise of equality or that these

supposed difficulties cannot be adequately resolved after

desegregation has been achieved.

4Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law of the District Court

(Aug. 26, 1969), as reproduced by Petitioners in Appendix D at p. 65a

of their Petition for Writ of Certiorari.

BAs this Court noted in Watson v. Memphis, 373 U. S. 526, 529-30

(1963), in ordering immediate desegregation of the Memphis city

parks:

“In considering the appropriateness of the equitable decree

entered below inviting a plan calling for an even longer delay in

effecting desegregation, we cannot ignore the passage of a sub

stantial period of time since the original declaration of the

manifest unconstitutionality of racial practices such as are here

challenged, the repeated and numerous decisions giving notice of

such illegality, and the many intervening opportunities hereto

fore available to attain the equality of treatment which the Four

teenth Amendment commands the States to achieve. These

factors must inevitably and substantially temper the present

import of such broad policy considerations as may have

underlain, even in part, the form of decree ultimately framed

in the Brown case. Given the extended time which has

elapsed, it is far from clear that the mandate of the second

Broivn decision requiring that desegregation proceed with ‘all

deliberate speed’ would today be fully satisfied by types of plans

or programs for desegregation of public educational facilities

which eight years ago might have been deemed sufficient.

Brown never contemplated that the concept of ‘deliberate speed’

would countenance indefinite delay in elimination of racial bar

riers in schools. . . .”

5

Recent statements on behalf of the Department of Jus

tice, if accurately reported,6 would suggest that the request

of the United States for additional delay, which was con

vincing to the District Court, is based, in significant part,

upon the fourth ground—community resistance—and upon

an asserted lack of adequate manpower in the Civil Rights

Division to enforce immediate desegregation. The Depart

ment’s reliance on these factors is, in our view, unwarranted

since neither of these arguments is sufficient or even cogniz

able by the courts.

1. This Court Has Specifically Held That Desegregation Must

Not Be Delayed Because of Community Resistance.

From the beginning of the battle for equality of educa

tional opportunity this Court has made it clear that com

munity resistance is not an accepted basis for delay. As

early as 1917 this Court in Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S.

60, 81, invalidating a zoning ordinance enforcing separa

tion of the races, held that the avoidance of “race conflicts”

was not an adequate reason for continued segregation. In

the second Brown decision itself, 349 U. S. 294, 300

(1955), this Court declared:

“ [I]t should go without saying that the vitality of

these constitutional principles cannot be allowed to

yield simply because of disagreement with them.”

Three years later, when faced with the spectre of co

ordinated state resistance to the enforcement of desegrega-

6“Nixon Aide Warns Quick Integration Can’t Be Enforced,”

The New York Times, p. 1, col. 3 (Sept. 30, 1969) ; “Leonard De

fends U. S. School Policy,” The New York Times, p. 25, col. 1

(Oct. 3, 1969). (The full text of these articles is set forth as

Appendix A to this Memorandum.) In a September 30, 1969, state

ment the Department conceded that, if the Supreme Court reversed

the decision below, the Department would enforce the order entered

pursuant to the Supreme Court’s mandate.

6

tion, the decision in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958),

was no less emphatic. Specifically rejected there was the

very concept upon which respondents’ contentions are, in

large part, premised: the capacity of opposition to create

practical difficulties in enforcement and then to successfully

offer those difficulties as proof of the prematurity of a decree

to desegregate now.7

2. The Alleged Inadequacy of the Enforcement Resources of

the United States Department of Justice Is No Ground for

Further Delay.

As we have noted, the United States Department of

Justice has publicly suggested that delay is in order because

the Department lacks adequate resources to enforce immedi

ate desegregation. But “it is an ‘inadmissible suggestion’

that action might be taken in disregard of a judicial deter

mination.” Powell v. McCormack, 395 U. S. 486, 549 n.

86 (1969).

“ [T]he Attorney General of the United States, has a

constitutional obligation to eliminate racial discrim

ination. . . . Failure on the part of any of these

Government officials to take legal action in the event

that racial discrimination does exist . . . would con

stitute dereliction of official duty.” United States v.

Fraser, 297 F. Supp. 319, 323 (M.D. Ala. 1968).

Moreover, the Department’s contentions are without

factual foundation. The Department has great flexibility

in allocating resources. If, at any given time, there is an

insufficient number of attorneys in the Civil Rights Divi

sion, the Attorney General may delegate civil rights

functions to attorneys from other divisions within the

7See also Watson v. Memphis, 373 U. S. 526, 535-37 (1963);

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284, 293 (1963) ; Taylor v. Louisiana,

370 U. S. 154 (1962) ; Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 (1961) ;

Brown v. Board of Educ., 349 U. S. 294, 300 (1955).

7

Department. 28 U. S. C. § 510 (Supp. I l l 1965-67).

Should there be insufficient manpower within the Depart

ment, the Attorney General is authorized to specially

appoint any attorney to assist him in any proceedings, civil

or criminal, whether or not the attorney is a resident of the

district in which the proceeding is brought. 28 U. S. C.

§515 (Supp. I l l 1965-67). The Lawyers’ Committee stands

ready to assist in the recruitment of the services of as many

volunteer attorneys as may be needed by the Department for

the purpose of enforcement of desegregation orders in these

and other cases.8

8The Lawyers’ Committee volunteers would offer their services

without compensation, but token payment is required by statute. 31

U. S. C. § 665(b) (1964).

8

CONCLUSION

Certiorari should be granted; the order of the Court of

Appeals of August 28, 1969, should be summarily reversed;

the order of the Court of Appeals of July 3, 1969, should

be reinstated; and the case remanded for immediate appro

priate action in order that desegregation may be immedi

ately effected.

Respectfully submitted,

J o h n W . D ouglas

George N. L indsay

Co-chairmen

B e t h u e l M . W ebster

Cyrus R. V a n ce

A sa S okolow

J o h n S c h a fer

L o u is F . O berdorfer

J o h n D oar

R ich a rd C. D in k e l s p ie l

A r t h u r H. D ean

L loyd N. C u tler

B ruce B rom ley

B erl I. B ern h a rd

1660 L Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae,

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

Of Counsel:

T im o t h y B. D y k

M ic h a e l R. K l e in

D e a n n e C. S ie m e r

October 7, 1969

A1

APPENDIX A

The New York Times, September 30, 1969NIXON AIDE WARNS QUICK INTEGRATION CAN’T BE ENFORCED

Rights Chief Says “Nothing Would Change”1

If Court Told South to Act Now

By F red P. Gr a h a m , Special to The New York Times

WASHINGTON, Sept. 29—-The chief of the Justice

Department’s Civil Rights Division said today that if the

Supreme 'Court should rule in a pending case that schools

must integrate immediately throughout the South the order

could not be enforced.

Referring to an appeal that the Court has already agreed

to consider on an accelerated schedule, Jerris Leonard, an

Assistant Attorney General, declared that “if the Court

were to order instant integration nothing would change.

Somebody would have to enforce that order.”

“There just are not enough bodies and people” in the

Civil Rights Division “to enforce that kind of a decision,”

Mr. Leonard said at a news conference.

Appeal in Mississippi

The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund

Inc. has asked the Supreme Court to discard its “all delib

erate speed” formula for school desegregation and to de

mand immediate abolition of racially identifiable schools

across the South.

The request was made in an appeal of a desegregation

delay that was granted to 30' Mississippi school districts at

the behest of the Nixon Administration.

A2

Mr. Leonard’s remarks raised the possibility that the

Supreme Court could find itself, for the first time since it

declared public school segregation unconstitutional in 1954,

in the position of issuing a school desegregation order with

out full expectation that it could or would be enforced by

the executive branch.

Mr. Leonard called the news conference to respond to a

group of dissident lawyers on his staff who have protested

that the Nixon Administration has softened civil rights

enforcement.

The dissident group released today the text of a state

ment of protest that they delivered last month to Mr.

Leonard, Attorney General John N. Mitchell and President

Nixon.

The statement charged that the Government’s action in

granting the Mississippi desegregation delay indicated “a

disposition on the part of responsible officials of the Federal

Government to subordinate clearly defined legal require

ments to nonlegal considerations when formulating the en

forcement policies of this division.”

The lawyers charged that by basing civil rights deci

sions on “other considerations” than the law, the Admin

istration “will seriously impair the ability of the Civil Rights

Division, and ultimately the judiciary, to attend to the

faithful execution of the Federal civil rights statutes.”

The statement reportedly bore the signatures of 65 of

the 74 nonsupervisory “line” attorneys in the Civil Rights

Division.

Seeks Court Compliance

Attorney General Mitchell was asked about the state

ment today at a news conference in Miami, where he is

attending the meeting of the International Association of

Chiefs of Police.

A3

He denied published reports that one of the “other con

siderations” that prompted the delay was a hint by Senator

John C. Stennis of Mississippi that he would not give the

Administration’s antiballistics missile project his full sup

port unless the delay were granted.

“That is completely false,” Mr. Mitchell said. He added

that “the objective of the Justice Department is to comply

with the Court decision and statutory requirements.”

Mr. Mitchell said he did not “presume that there would

be any need to take action” against the dissident lawyers.

Mr. Leonard said he had not been embarrassed by the

ferment within his division and said he was confident that

the line attorneys would cease their protests now that the

Government’s policy has been clarified.

Sources within the dissident group said that their state

ment was released today after having been kept secret for

a month because the group believed that Mr. Leonard had

not given assurances that the Justice Department would

push school desegregation vigorously. But the lawyers said

they did not know what further protest action, if any, their

group would take.

Request by Finch

Mr. Leonard stressed repeatedly throughout his 45-

minute news conference that the threat of school boycotts

and school-closings by diehard whites in the South could

retard the pace of school desegregation. The dissident at

torneys have charged that this official attitude could en

courage Southern whites to defy the law.

Mr. Leonard disclosed that Robert H. Finch, Secretary

of Health, Education and W elf are, asked the Federal

judges who had jurisdiction over the Mississippi case for

the delay last month without first consulting Mr. Leonard,

who had ultimate responsibility for the handling of the case.

A4

But Mr. Leonard agreed with Mr. Finch’s opinion that

the time was too short to implement the desegregation plans

in the few days that remained before the start of the school

year. The judges granted the delay, which would put off

major integration moves in the schools for at least a year.

If the delay had not been obtained, Mr. Leonard said,

“I think we would have been faced with massive litigation

efforts, school closings, and massive boycotting. It would

have taken years and years to bring these districts back into

line.”

He predicted that with a year in which to lay the ground

work for desegregation, it will be accomplished smoothly

in 1970.

In their appeal to the Supreme Court, the legal defense

fund’s lawyers contend that the possibility of delay has

encouraged Southern school officials to make no plans for

desegregation and then to plead at the last moment that

there is inadequate time to prepare for desegregation with

out disrupting the schools.

The defense fund asked the Justices to give the appeal

a speedy hearing and to order immediate desegregation of

all Southern schools. The Court promptly announced that

it will decide soon after the new Court term begins on

Oct. 6 whether or not it will hear the appeal.

In the past, when the Court has agreed to accelerate its

normal procedures, it has often developed that the justices

were impressed with the contentions of the party seeking

the speedy hearing.

A5

The New York Times, October 3, 1969LEONARD DEFENDS U. S. SCHOOL POLICY

Says Critics ©f Rights Stand

‘Run Off at the Mouth5

WASHINGTON, Oct. 2 (A P)—Assistant Attorney

General Jerris Leonard defended the Nixon Administra

tion’s school desegregation policy today, calling its critics

“a lot of people who are frankly running off at the mouth.”

Mr. Leonard, chief of the Justice Department’s Civil

Rights Division, also said he had no intention of quitting

because of dissension among his lawyers over Administra

tion policies.

Llis comments came at an impromptu news conference

after Garry J. Greenberg, who resigned yesterday at the re

quest of Mr. Leonard, said, he “would not and could not

defend the Government’s position.”

Insisting that there had been no slowdown in school

desegregation, Mr. Leonard said, “take the Mississippi

situation out and give me one example where we have not

vigorously enforced the civil rights laws.”

In order to accomplish what some critics propose, Mr.

Leonard said, “no one could make a statement that didn’t

advocate immediate, strict compliance with the law with

out regard to educational factors.”

“I reject that 1,000 per cent,” he said. “You cannot

desegregate a school district that is presided over by re

calcitrant school board members by simply issuing an

edict.”

Cites Times Editorial

Such a situation, he said, would put “school board mem

bers in the jail houses and kids in segregated schools.”

A6

Asked about statements by Federal judges who charged

that a July policy statement was “a red herring across the

path of progress toward desegregation,” Mr. Leonard said,

“I don’t care if its judges, lawyers, legislators or whoever

disagrees.”

He took particular issue with The New York Times,

saying an editorial yesterday was “picayunish and pusillani

mous and written by someone uninformed.

Asked about critical statements by the Commission on

Civil Rights and some Congressmen, Mr. Leonard re

marked, I think you’ve got a lot of people who are frankly

running off at the mouth who don’t know what the facts