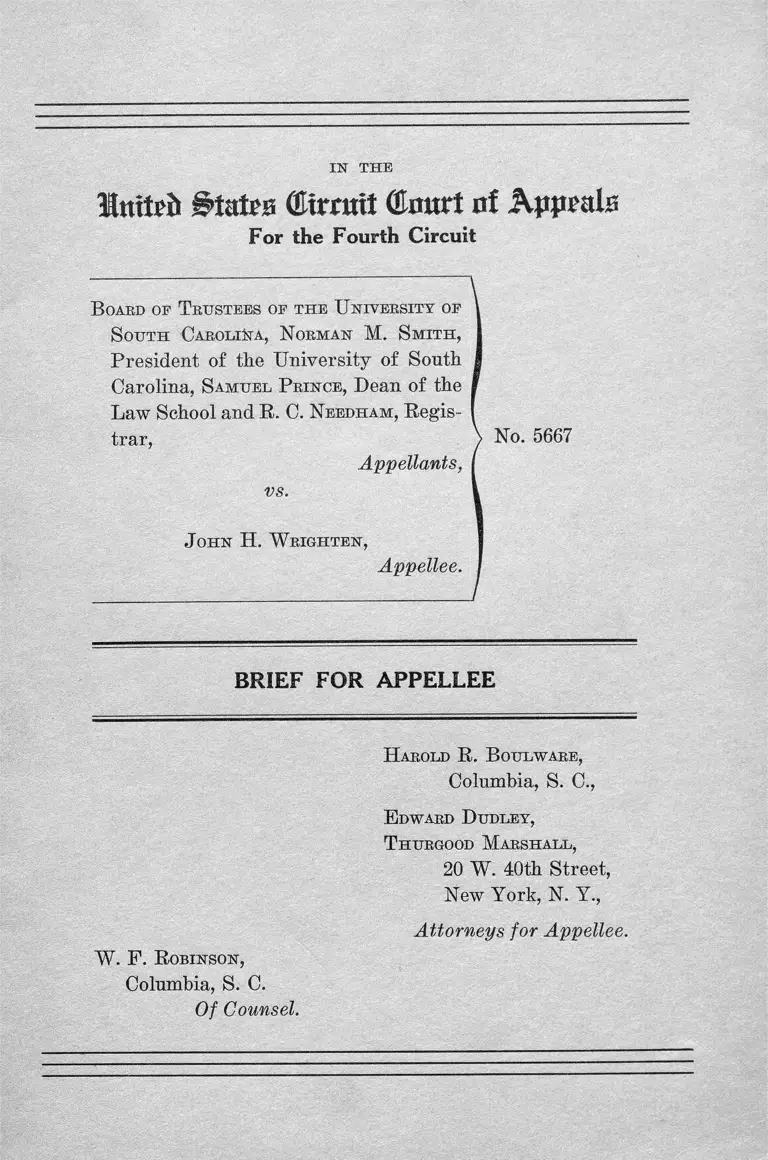

University of South Carolina Board of Trustees v. Wrighten Brief of Appellee

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. University of South Carolina Board of Trustees v. Wrighten Brief of Appellee, 1974. 93eb23f2-c79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f590d056-4a3a-4e85-8484-ad64890fcfa0/university-of-south-carolina-board-of-trustees-v-wrighten-brief-of-appellee. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

1ST T H E

Stall's (Eirotit (Erntrt nf Kppmlz

B oaed of Trustees op the U niversity op

South Carolina, Norman M. Smith,

President of the University of South

Carolina, Samuel P bince, Dean of the

Law School and R. C. Needham, Regis-

For the Fourth Circuit

trar,

J ohn H. W righten,

vs.

Appellants,

Appellee.

No. 5667

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE

H arold R. B oulware,

Columbia, S. C.,

E dward Dudley,

T hurgood Marshall,

20 W. 40th Street,

New York, N. Y.,

Attorneys for Appellee.

W . F. R obinson,

Columbia, S. C.

Of Counsel.

PAGE

1Statement of Case

Statement of Facts__________________________________ 2

Question Involved

Is the refusal to admit a qualified Negro to the Uni

versity of South Carolina Law School on the basis

of race a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the United State Constitution where said insti

tution is the only place offering legal training by

the state ________________________________________ 4

Conclusion___________________________________________ 11

Table of Cases.

Alston v. Norfolk School Board (C. C. A. 4th), 112 F.

(2d) 992 (1940) certiorari denied, 311 U. S. 693

(1940) ----------------------------------------------------------------- 9

Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339 (1879)__________ _ 9

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U. S. 390 (1923)_______________ 10

Missouri ex rel. Caines v. Canada, 307 U. S. 337

(1938) -------------------------------------------------------5, 7, 9,10,11

Pearson, et al. v. Murray, 169 Md. 478 (1936)______8,10,11

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886)____________ 9

IN' T H E

Inttefc States Ctrrmt (&nwt of Appeals

For the Fourth Circuit

Board oe Trustees of the University of

South Carolina, Norman M. Smith ,

President of the University of South

Carolina, Samuel P rince, Dean of the

Law School and R. C. Needham, Regis

trar,

Appellants,

vs.

No. 5667

J ohn H. W righten,

Appellee.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE

Statement of Case

On January 4, 1947, appellee, plaintiff below, filed in the

District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina

a complaint against appellants, defendants below, for refus

ing to admit him to the first-year class of the School of Law

of the University of South Carolina (A-17).

Following a pre-trial conference held on May 15, 1947,

the Court announced that the equitable issues involved

would be tried first before the Court without a jury. The

Court’s order on the pre-trial conference entered May 20,

1947, establishes that an agreement had been reached be-

2

tween opposing parties that the broad question of the right

of segregation and education according to races is not be

fore the Court but that the issue here is whether the plain

tiff-appellee is given law school facilities by the State of

South Carolina comparable to those afforded white students

(A-13).

Defendants-appellants appealed from the judgment of

the United States District Court for the Eastern District

of South Carolina entered on July 12, 1947, granting an

injunction against appellants restraining them from exclud

ing from admission to the Law School of the University

of South Carolina plaintiff-appellee and any person or per

sons by reason of race or color unless legal education on

a complete equality and parity is offered and furnished

to the appellee and other persons in like plight upon the

same terms and conditions by some other institution estab

lished, operated or maintained by the State of South Car

olina.

It is the judgment from this trial in appellee’s favor

that appellants now appeal.

Statement of Facts

Appellee, John H. Wrighten, is a Negro over the age

of 21, a citizen and resident of the State of South Carolina

and has all of the lawful qualifications necessary for admis

sion to the Law School of the University of South Carolina

(A-98). Wrighten made application for admission to the

Law School of the University of South Calorina first on

July 2, 1946 and again on August 17, 1946 but was refused

admission by the officials in charge of the said Law School

because of his race (A-98). He did not make application

to State College where there was no law school in existence

(A-98).

3

Under the Constitution and Laws of the State of South

Carolina, the University, including its Law School, is main

tained solely for persons of the white race (A-98). The

appellants are the Board of Trustees of the University

of South Carolina, Norman M. Smith, President of the

University of South Carolina, Samuel Prince, Dean of the

Law School, and R. C. Needham, Registrar of the same

(A-98). The University of South Carolina (commonly

called The University) is an institution maintained by the

State for the purpose of providing higher education (in

cluding the maintenance of the Law School) for qualified

persons of the white race and its control is vested in the

Board of Trustees named in accordance with the statute

laws of the State (A-98). The Colored Normal, Industrial,

Agricultural & Mechanical College of South Carolina (com

monly called State College) is an institution maintained by

the State for the higher education of Negroes and its con

trol is vested in the Board of Trustees, which is independent

of the Board of Trustees of the University. The Governor

of South Carolina is an ex-officio member of both Boards

(A-98-99).

The General Assembly of the State of South Carolina,

in its annual Appropriation Act for the year 1945 authorized

the establishment of the Law School at State College but

left it to the discretion of the Trustees and President who

considered the matter but did not establish such a school

and the appropriation available for the same was used for

other purposes (A-9.9). Similar action occurred in 1946.

Similarly, the General Assembly of the State of South

Carolina in its Appropriation Act for the year 1947, adopted

after this case was filed, authorized the Board of Trustees

of State College to establish and maintain a graduate law

department and made an appropriation for that purpose

(A-99).

4

The present action is brought in the nature of a class

suit to determine whether defendants’ policy, custom and

usage in denying plaintiff and other qualified Negroes ad

mission to the Law School of the University of South

Carolina pursuant to the Constitution and Laws of the

State of South Carolina violates the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Question Involved

Is the refusal to admit a qualified Negro to the Uni

versity of South Carolina Law School on the basis of

race a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution where said institution is the

only place offering legal training by the state.

It is submitted that the only question before this Court

at this time is whether or not, in the light of the facts in

this case, appellants’ refusal to admit appellee into the

University of South Carolina Law School in the absence

of a showing that equal facilities were provided elsewhere

within the State of South Carolina is a violation of the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States.

The President of State College at Orangeburg testi

fied that there was no law school available which admitted

Negroes in South Carolina prior to or at the time of the trial

of this case (A-17). This fact has never been disputed by

anyone. At the time of the trial o f this case the only law

school maintained by the State of South Carolina was at the

University of South Carolina. The only place appellee

could obtain a legal education in South Carolina was at the

University of South Carolina. He has been refused ad

mission to this school solely because of his race or color.

5

Had he been white, there is no question that he would have

been admitted.

Appellants contend that the segregation laws of South

Carolina justify their refusal to admit Negro students. In

doing so they completely ignore the decision of the United

States Supreme Court in Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

305 U. S. 337, at page 349 (1938) on this question:

“ * * * The admissibility of laws separating the races

in the enjoyment of privileges afforded by the State

rests wholly upon the quality of the privileges which

the laws give to the separated groups within the

State. * * * ”

Appellants in their brief have raised the arguments

concerning the duty of appellee to apply for admission to

an imaginary law school at State College located at Orange

burg, South Carolina. The lower Court’s order on pre-trial

conference set the pattern and conduct in the trial of this

case, it was stipulated as follows:

“ It was agreed that without any general admis

sions and limited solely to the issues to be tried in

this case the broad question of the right of segrega

tion and education according to races is not before

the Court but that the issue here is whether the plain

tiff is given law school facilities by the State of South

Carolina comparable with those afforded white stu

dents; Provided of course that if it be shown that

opportunities are given, the parties may go into the

sufficiency and the quality of the same” (A-13).

Whether or not appellants have complied with the re

quirements of the Fourteenth Amendment as presented in

the order of the lower Court (A-100-101), in alternative

manner is another question that may come before this

Court at some future time. The following testimony by

Miller F. Whittaker, President of State College at Orange

6

burg, 8. C. (A-17), conclusively shows that there was no law

school within the State of South Carolina prior to or at the

time of the trial of this action. In answer to questions con

cerning State College, Mr. Whittaker gave the following

testimony:

“ Q. Do you have a law school there? A. No, no

law school.

“ Q. As of June of the year 1946, did you have a

law school there ? A. We did not.

“ Q. Did you have one as of January of this year?

A. We did not.

“ Q. Do you have one now? A. We do not.

“ Q. Is there any law school operated by the State

of South Carolina to which Negroes are at present

admitted if you know? A. There is none as far as

I know.

“ Q. Do you know of any other school or uni

versity in the State of South Carolina for the educa

tion of Negroes beyond the high school level other

than the school that you are president of? A. There

is none, no.

“ Q. So, at the present time there is no law school

at your school? A. That is right.

“ Q. There is no setup at the present time in

existence for the training of the Negro in the field of

law at your institution? A. There is none.”

In spite of this testimony from the President of the only

institution in South Carolina where Negroes were admitted

to higher education, appellants insist that the language of

the 1945 and 1946 Appropriation Act (44 Stat. 401, 1605,

A-106), “ authorized” the establishment of a law school at

State and that this language must be construed as manda

tory in the light of South Carolina law requiring segrega

7

tion. (These statutes are set out in full in Appellants’ Ap

pendix, pp. 92-94.) Provisions similar to those in the Acts

of 1945 and 1946 were on the statute books of Missouri at

the time the suit against the University of Missouri arose

in the case of Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, supra.

The Supreme Court of the United States stated as to this

defense in that case:

# * it appears that the policy of establishing the

law school at Lincoln University has not yet ripened

into an actual establishment and it cannot be said that

a mere declaration of purpose still unfulfilled is

enough. The provision for legal education at Lin

coln at present is entirely lacking. Respondents’

counsel urge that if on the date when petitioner ap

plied for education to the University of Missouri he

had instead applied to the curators of Lincoln Uni

versity, it would have been their duty to establish a

law school; and that this agent of the state, to which

he should have applied, was specifically charged with

the mandatory duty to furnish him what he seeks.

We do not read the opinion of the Supreme Court as

construing the state statute to impose such a manda

tory duty as the argument seems to assert * *

Even assuming that the appropriation by the State of

South Carolina to State College for all graduate work, in

cluding law, medicine, pharmacy and out-of-state scholar

ships (A-36) will be available to set up a future law school

for Negroes, we must rely upon the testimony of President

Whittaker in giving his opinion as to the physical possibil

ity of accomplishing such an act.

“ Q. President Whittaker, I want your opinion

as to whether or not in your mind, bearing in mind

the difficulty in getting law books, the lack of an

adequate building space, the fact that you do not

have a faculty member yet, nor a dean, nor a librar

ian, do you in your own mind believe that you can

8

set up a law school by September that would be the

full and complete equal of the law school at the Uni

versity of South Carolina? A. No, I do not think

so. That is my opinion” (A-37).

In the case of Pearson, et al. v. Murray,1 which was a

mandamus action to compel the admission of a qualified

Negro to the University of Maryland Law School, the

Court of Appeals of Maryland in granting the requested

relief stated:

“ The method of furnishing the equal facilities

required is at the choice of the State now or at any

future time. At present it is maintaining only the

one law school . . . no separate school for colored

students has been decided upon and only an inade

quate substitute has been provided. Compliance

with the Constitution cannot be deferred at the will of

the state. Whatever system it adopts for legal educa

tion now must furnish equality of treatment now. . . .

in Maryland now the equal treatment can be fur

nished only in the one existing law school, the peti

tioner, in our opinion, must be admitted there.”

The Court then concluded:

“ . . . The state has undertaken the function of

education in the law but has omitted the students of

one race from the only adequate provision made for

it and omitted them solely because of their color.

If those students are to be offered equal treatment

. . . they must, at present, be admitted to the one

school provided. And as the officers and Regents

are the agents of the state intrusted with the con

duct of the school, it follows that they must admit

. . . there is identity in principle and agent for the

application of the constitutional requirement.”

1 169 Md. 478 (1936).

9

The Gaines case has provided a clear principle for the

decision of the basic rights of the parties in this case. In

that case, Gaines, a Negro citizen and resident of the State

of Missouri, attempted to obtain entrance to the Law

School of Lie University of Missouri, which was maintained

solely for whites. There was another institution (Lincoln

University) maintained by the State of Missouri for the

higher education of Negroes. It had no law school, though

there had been appropriations and authorizations to its

officials to establish a law school when deemed advisable.

After denial of the relief in the state court and upon ap

peal to the United States Supreme Court, that Court held

in unmistakable terms that a Negro was entitled to the

same educational facilities as a white person within the

state.

It is our contention, therefore, that the Gaines case,

supra, sets forth the law which is controlling in this case.

This Court is asked by appellees to merely sustain the prin

ciple, at this time, that the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution requires the State of South

Carolina in furnishing legal education to qualified white

students at the University of South Carolina to admit

qualified Negroes into the University of South Carolina

in the absence of equal facilities elsewhere in the state.

A long list of cases has sustained the principle that no

state shall deny to any of its citizens the equal protection

of the laws on account of race or color.2 3 *

When appellee applied to enter the law school at the

University of South Carolina it was the only law school

2 E x Parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339 (1879) ; Yick W o v. Hopkins

Ug S' 356 ( 1886) 5 Alston v. Norfolk School Board, 112 F. (2d)

992 (C. C. A. 4th, 1940) Certiorari denied 311 U. S. 693 (1940) •

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, supra. ’

1 0

maintained and operated by the state for the legal education

of its citizens (A-17).

Appellants admittedly denied him the right to attend

solely on account of his race and color (A-98).

The equal protection of the laws is denied where the

state maintains a law school from which Negro students,

otherwise qualified, are excluded because of their race, and

at the same time does not provide a law school within the

state which Negroes may attend.3 Missouri ex rel. Gaines

v. Canada, supra; Pearson, et al. v. Murray, supra.

The fact that there is a limited demand within the state

for the legal education of Negroes does not excuse this

discrimination. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, supra;

Pearson, et al. v. Murray, supra. As an individual this ap

pellee is entitled to the equal protection of the laws, and the

state is bound to furnish him within its borders facilities for

legal education equal to those which the state affords for

persons of the white race, whether or not other Negroes

seek the same opportunity Missouri ex rel. Gaines v.

Canada, supra. This discrimination is not excused because

3 Appellee is also deprived of his liberty without due process of

law through this denial of equal protection by the State of South

Carolina as the right “ to acquire useful knowledge” is one of those

liberties long recognized at common law as essential to the orderly

pursuit o f happiness by free men.

As stated by the U. S. Supreme Court in M eyer v. Nebraska, 262

U. S. 390, 399: “ ‘No state shall * * * deprive any person of

life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.’ While this

Court has not attempted to define with exactness the liberty thus

guaranteed, the term has received much consideration, and some of

the included things have been definitely stated. Without doubt, it

denotes not merely freedom from bodily restraint, but also the right

of the individual to contract, to engage in any of the common occu

pations of life, to acquire useful knowledge, to marry, establish a

home and bring up children, to worship God according to the dictates

of his own conscience, and, generally, to enjoy those privileges long

recognized at common law as essential to the orderly pursuit of happi

ness of free men.” (Citing cases.)

1 1

it may be termed temporary pending the establishment of

a law school for Negroes within the state Missouri ex rel.

Gaines v. Canada, supra; Pearson, et al. v. Murray,

supra.

Conclusion

In considering this question, appellee respectfully re

quests this Court to examine carefully the violation of the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment by

appellants in refusing to accept appellee into the only law

school maintained by the State of South Carolina solely

because of appellee’s race and color. The right violated is

an individual one which the agents of the State of South

Carolina acting under color of law within the State of South

Carolina cannot justify. Equal protection and due process

cannot be satisfied by continuously pointing to imaginary

equality. As a matter of fact, the lower Court could have

issued a permanent injunction at the time of the hearing

admitting appellee into the only law school in the State of

South Carolina.

It is respectfully submitted that the appeal be dismissed.

Respectfully submitted,

Harold R. B oulware,

Columbia, S. C.,

T hurgood Marshall,

E dward R. D udley,

20 West 40th Street,

New York City,

Attorneys for Appellees.

«̂ |gĝ >212 [6276]

L aw yers P ress, I n c ., 165 William St., N. Y. C. 7; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300