Harvis v. Roadway Express, Inc. Brief of Plaintiff-Appellant

Public Court Documents

August 12, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Harvis v. Roadway Express, Inc. Brief of Plaintiff-Appellant, 1991. 573d7a9b-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f5bf6611-eee8-44d9-a455-11fa3799c398/harvis-v-roadway-express-inc-brief-of-plaintiff-appellant. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

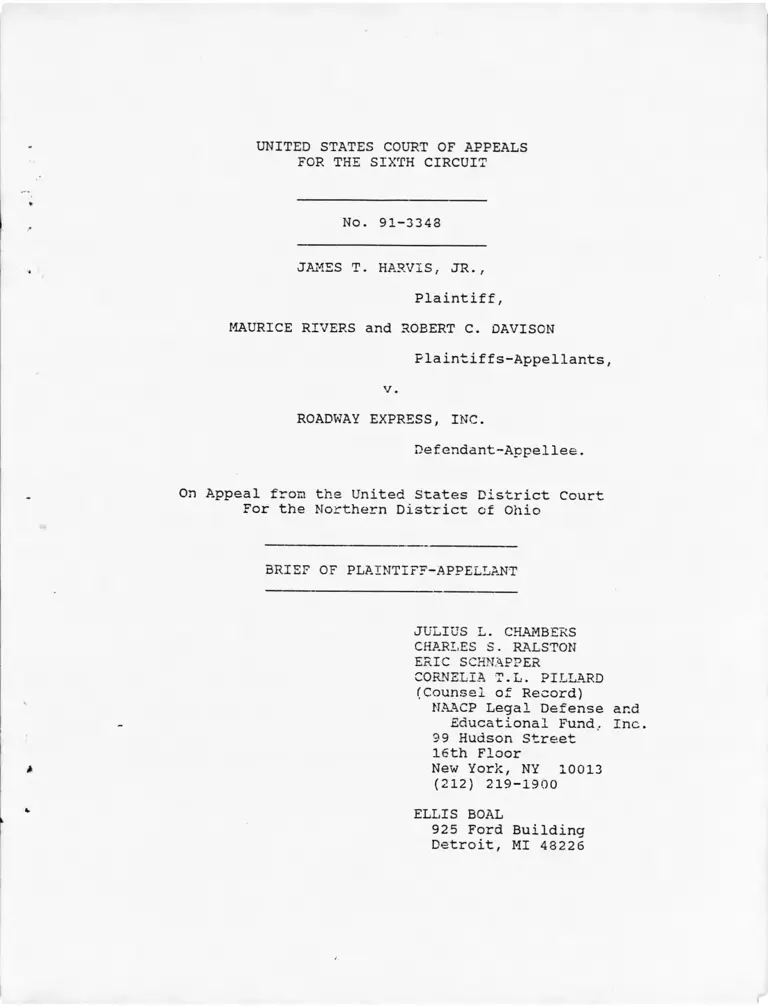

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 91-3343

JAMES T. HARVIS, JR.,

Plaintiff,

MAURICE RIVERS and ROBERT C. DAVISON

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

ROADWAY EXPRESS, INC.

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

For the Northern District of Ohio

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CHARLES S. RALSTON

ERIC SCHNAPPER

CORNELIA T.L. PILLARD

(Counsel of Record)

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

ELLIS BOAL

925 Ford Building

Detroit, MI 43226

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITES...........................................ii

DISCLOSURE OF COPORATE AFFILIATIONS AND FINANCIAL INTEREST . . V

ISSUE PRESENTED FOR REVIEW ................................ 1

STANDARD OF REVIEW ........................................ 3

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E ...................................... 3

Nature of the C a s e .................................... 3

Course of Proceedings ................................ 4

District Court Opinion ................................ 6

STATEMENT OF THE F A C T S .................................... 8

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT...........................................13

ARG U M E N T ..................................................... 14

ROADWAY VIOLATED PLAINTIFFS' § 1981 RIGHT TO ENFORCE

THEIR CONTRACT FREE FROM RACIAL DISCRIMINATION ........ 14

A. Roadway's Retaliation Against Plaintiffs for

Filing Grievances to Enforce Their Contract

Rigt^s, as Distinct From Rights Derived From Other

Sources, Remains Prohibited By Section 1981After Patterson.................................. 16

B. Roadway's Discharge of Rivers and Davison Even

After They Prosecuted Their Grievances Violates

Their Right to Enforce Their Contracts .......... 20

C. Roadway's Retaliatory Discharge Violates

Plaintiffs' § 1981 Right to Enforce Their

Contracts Even if Patterson Precludes Discharge

Claims Based on The Right to Make Contracts . . . . 22

CONCLUSION................................................ 2 6

ADDENDUM.................................................... 2 7

i

21

21

3

8

20

18

"3

22

22

14

21

22

20

18

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Carter v. South Central Bell.

912 F.2d 832 (5th Cir. 1990),

cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 2916 (1991) . . . .

Chambers v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co..

917 F.2d 5 (5th Cir. 1990),

petition for cert, filed

(May 14, 1991) (No. 90-1776) ....................

Conley v. Gibson.

355 U.S. 41 (1957) ............................

D. Federico Co. v. New Bedford Redevelopment Authority.

723 F.2d 122 (1st Cir. 1983) ....................

Danaerfield v. The Mission Press.

1989 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 8985 (N.D. 111. 1989)

Dash v. Equitable Life Assur. Soc. of U.S..

753 F. Supp. 1062 (E.D.N.Y. 1990) ................

Dugan v. Brooks.

818 F.2d 513 (6th Cir. 1987) ....................

Gersman v. Group Health Assoc..

931 F.2d 1565 (D.C. Cir. 1991) ................

Gonzalez v. Home Ins. Co..

909 F.2d 716 (2d Cir. 1L30) ....................

Goodman v. Lukens Steel.

482 U.S. 656 (1987) ............................

Harris v. Richards Mfq. Co..

675 F.2d 811 (6th Cir. 1982) ....................

Hicks v. Brown Group.

- 902 F.2d 630 (8th Cir. 1990),

overruled by Taggart. 935 F.2d 947 (8th Cir. 1991).

Hall v. County of Cook.

1989 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 9661 (N.D. 111. 1989)

Hill v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber, Inc..

918 F.2d 877 (10th Cir. 1990) ....................

ii

8

Jackson v. Havakawa.

605 F.2d 1121 (9th Cir. 1979),

cert. denied. 445 U.S. 952 (1980) .

Kozam v. Emerson Elec. Co..

739 F. Supp. 307 (N.D. Miss. 1990),

aff'd. 928 F.2d 401 (5th Cir. 1991) . . . . 19

Lvtle v. Household Manufacturing.

110 S. Ct. 1331 ( 1 9 9 0 ) ........................ 23

McKnight v. General Motors Coro..

908 F.2d 104 (7th Cir., 1990),

cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 1306 (1991) . . 17, 21, 22, 23

Moore v. City of Paducah.

790 F. 2d 557 (6th Cir. 1 9 8 6 ) .................... 8

Northern Pipeline Construction Co. v. Marathon Pipe Line Co.

458 U.S. 50 ( 1 9 8 2 ) ............................ 23

Overby v. Chevron U.S.A., Inc..

884 F.2d 470 (9th Cir. 1989)

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union.

491 U.S. 164 (1989)

18

passim

Prather v. Dayton Power & Light Co..

918 F.2d 1255 (6th Cir. 1990), petition for cert, filed.

59 U.S.L.W. 3687 (U.S. Mar. 26, 1991) . . . . 22

Russell v. District of Columbia.

747 F. Supp. 72 (D.D.C. 1990) . . . . . . 19

Sherman v. Burke Contracting. Inc..

891 F. 2d 1527 (11th Cir. 1 9 9 0 ) ................ 17, 21

Taggart v. Jefferson Ctv. Child Support.

935 F. 2d 947 (8th Cir. 1 9 9 1 ) .................... 22

Tompkins v. DeKalb County Hosp. Auth..

- 916 F. 2d 600 (11th Cir. 1990).................... 22

Trujillo v. Grand Junction Regional Center.

928 F. 2d 973 (10th Cir. 1991).................... 22

Von Zuckerstien v. Argonne National Lab..

760 F. Supp. 1310 (N.D. 111. 1991)................ 18

Williams v. First Union Nat'1 Bank of N.C..

920 F.2d 232 (4th Cir. 1990),

cert, denied. Ill S. Ct.2259 (1991) . . . . 18, 22

ill

Winston v. Lear Siegler Inc..

558 F.2d 1266 (6th Cir. 1977) . 21

STATUTES

1964 Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et sea. .

1866 Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1981 . . . .

Labor-Management Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. §§ 185, 159.

4

passim

4

IV

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

(This statem ent should be placed immediately preceding the statem ent of issues contained

in the brief of the party. See copy of 6th Cir. R. 25 on reverse side of this form.)

JAMES T. HARVIS, J R .;

P l a i n t i f f

MAURICE RIVERS; ROBERT C. DAVISON

P l a i n t i f f s - A p p e l la n t s

v.

ROADWAY EXPRESS, INC.

D e fe n d a n t - A p p e l le e

)

))

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

DISCLOSURE OF CORPORATE AFFILIATIONS

AND FINANCIAL INTEREST

JAMES T. HARVIS, JR , MAURICE RIVERS

Pursuant to 6th Cir. R. 25, __________AND ROBERT C. DAVISON

makes the following disclosure:

(name of party)

Is said party a subsidiary or affiliate of a publicly owned corporation?

If the answer is YES, list below the identity of the parent corporation or affiliate

and the relationship between it and the named party:

Is there a publicly owned corporation, not a party to the appeal, that has a

financial interest in the outcome? Mr>

If the answer is YES, list the identity of such corporation and the nature of the

financial interest:

A u g u st 1 2 , 1991

(Signature of Counsel) (Datej

6CA-1

7/86

Page 1 of 2

ISSUE PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

Whether the district court erred in dismissing two black

employees' claims that Roadway Express violated 42 U.S.C. § 1981

by discriminatorily retaliating against them for successfully

using the collective bargaining agreement's grievance procedure

to enforce their established contract rights against race-based

infringement.

STATEMENT IN SUPPORT OF ORAL ARGUMENT

Pursuant to 6th Cir. R. 9(d), oral argument should be heard

in this case because it presents an important legal issue of

first impression in this Circuit involving the scope of a major

federal civil rights law, 42 U.S.C. § 1981. While plaintiffs'

§ 1981 claims were awaiting trial, the Supreme Court in Patterson

v. McLean Credit Union. 491 U.S. 164 (1989), decided that the

§ 1981 "right ... to make and enforce contracts" on racially

neutral terms does not prohibit racial harassment during the

execution of a contract. The district court in this case

extended Patterson to hold that § 1981 categorically does not

prohibit retaliatory discharge in any circumstances.

This appeal is the first time since Patterson that a federal

court of appeals will review a claim of race-based retaliation

for enforcement of contract rights as such. Other circuit courts

have upheld dismissals of § 1981 retaliation claims under

Patterson when they involved retaliation against plaintiffs for

their enforcement of statutory or other non-contractual rights,

finding that such retaliation does not impair the "right ... to

... enforce contracts" on racially neutral terms. Courts

rejecting such claims have commented, however, that § 1981 claims

should be sustained where, as here, defendants discriminatorily

retaliate against plaintiffs specifically for enforcing their

contract rights.

2

STANDARD OF REVIEW

Because the district court dismissed plaintiffs' § 1981

claims for failure to state a legally sufficient claim, this

Court must review its judgment de novo. Moreover, all

plaintiffs' allegations must be taken as true and construed in

the light most favorable to them. Dugan v. Brooks. 818 F.2d 513,

516 (6th Cir. 1987). Remand is required unless "it appears

beyond doubt that plaintiff can prove no set of facts in support

of his claim which would entitle him to relief." Conley v.

Gibson. 355 U.S. 41, 45-46 (1957).

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Nature of the Case

Maurice Rivers and Robert C. Davison, experienced black

garage mechanics, appeal from the district court's Memorandum and

Order applying the Supreme Court's decision in Patterson to

dismiss their § 1981 claims against their font0 .* employer,

Roadway Express, Inc. ("Roadway," "the Company"). After the

conclusion of discovery and pretrial motions in this case, the

Supreme Court handed down its Patterson decision changing the law

governing § 1981 claims. The district court then dismissed

plaintiffs' retaliation claims as no longer covered by § 1981.

Plaintiffs seek reversal of that decision on the ground that

their § 1981 right to enforce their employment contract free from

discrimination encompasses their claims of discriminatory

retaliation for exercising their contract rights.

3

Course of Proceedings

Maurice Rivers and Robert C. Davison, together with a third

co-plaintiff James T. Harvis, Jr.,1 filed their Complaint against

Roadway on February 22, 1987 in the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Ohio, Western Division, alleging

that Roadway discharged them in violation of the Civil Rights of

1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981. They also asserted claims against

Roadway under the 1964 Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et

sea.. and under § 301 of the Labor-Management Relations Act

(LMRA), 29 U.S.C. § 185(a). Plaintiffs raised a hybrid § 301/

duty of fair representation claim against the Union (Local Union

20, International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs,

Warehousemen, and Helpers of America). Plaintiffs filed a First

Amended Complaint dated September 28, 1987. (R. 56: Motion; R.

218: First Amended Complaint). The district court has entered

final judgments on all claims of each plaintiff. Only the § 1981

claims of Rivers and Davison are the subject of this appeal.

The parties engaged in extensive discovery over several

months under the law as it stood prior to Patterson. On November

16, 1987, Roadway moved for summary judgment, (R. 88: Motion),

and on December 1, 1987, the Union also moved for summary

judgment on all claims. (R. 113-115: Motions). By Memorandum

and Order dated November 30, 1988, the district court dismissed

plaintiffs' claims that the Union violated its duty of fair

J Harvis was a co-plaintiff, but his case was severed

from that of Rivers and Davison and tried separately. His claims

are not at issue on this appeal.

4

representation, and also dismissed plaintiffs' related labor law

claims against Roadway. (R. 224: Memorandum and Order at 3-4).

The district court denied Roadway judgment, however, on

plaintiffs' race discrimination claims under Title VII and

§ 1981. The district judge "thoroughly reviewed the pleadings,

affidavits, depositions transcripts and other materials filed in

support of and in opposition to summary judgment," and determined

that "genuine issues of fact exist as to plaintiffs' claims under

Section 1981 and Title VII against defendant Company." (R. 224:

Memorandum and Order at 6).

Plaintiffs' case was awaiting trial when the Supreme Court

handed down its decision in Patterson v. McLean Credit Union. 491

U.S. 164. (R. 230: Pretrial Order). The district court, by

Order dated July 10, 1989, directed Rivers and Davison to show

cause why their § 1981 claims should not be dismissed in light of

the Supreme Court's decision. (R. 230: Order to Show Cause)

Plaintiffs argued that their § 1981 claims should survive because

they were not based exclusively on the right to "make ...

contracts," which Patterson confined to discrimination in

contract formation, but were based on the right to "enforce

contracts." (R. 259: Plaintiffs' Response to Patterson at 10-

11). The Patterson Court held that the § 1981 enforcement clause

continues to prohibit the kind of discriminatory interference

with "nonjudicial methods of adjudicating disputes about the

force of binding obligations" that occurred in this case. 491

U.S. at 177. The district judge disagreed, and dismissed

5

plaintiffs' § 1981 claims in an unpublished Memorandum and Order

dated January 19, 1990. (R. 266: Memorandum and Order). ^

District Court Opinion

The district court held that plaintiffs' § 1981 claims are

no longer covered by the statute after Patterson. (R. 266:

Memorandum and Order at 3 - 1 ^ The court quoted an extensive

passage of the Supreme Court's opinion construing the "right to

... make ... contracts" as not protecting an employee from the

employer's post-contract formation conduct relating to "the

conditions of continuing employment." Id. at 3. The district

court concluded that "§ 1981 does not apply to discriminatory

discharges since a discharge is conduct which occurs after the

formation of a contract." Id.

The district court held categorically that even where a

discharge is in retaliation for seeking to enforce contract

rights against racially discriminatory breach, it does not

violate § 1981. The court based this conclusion on the decisions

of "[o]ther district courts [which] have considered similar

issues and concluded that claims that a plaintiff was discharged

in retaliation for exercising rights still protected under § 1981

do not state a claim under § 1981 in light of Patterson." Id.

at 4.

The court acknowledged that the analysis whether § 1981

applies might differ where the right to enforce as opposed to

make contracts is concerned. If a plaintiff were denied access

6

to a grievance procedure, the court commented that he would have

been deprived of "precisely what is protected under the 'right to

... enforce contracts' provision of § 1981." Id. at 4. The

court distinguished, however, punishment that precedes and

forecloses a grievance from that which immediately follows and

nullifies it.

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS2

Roadway hired Robert Davison to work as a washer in its

Akron facility in 1972, and hired Maurice Rivers the following

year to work as a janitor at the same facility. (R. 192:

Appendix I of Plaintiff in Opposition to Summary Judgment

("Appendix"), Davison Dep. 7/15/87, at 44-45? Rivers Dep.1

In dismissing plaintiffs' § 1981 claims for failure to

"state a claim upon which relief can be granted in light of

Patterson," the district judge properly considered plaintiffs'

current factual contentions, rather than the undeveloped

allegations of the First Amended Complaint. (R. 266: Memorandum

and Order at 4). See. Jackson v. Havakawa. 605 F.2d 1121, 1129

(9th Cir. 1979), cert, denied. 4*5 U.S. 952 (1980) (holding that

plaintiffs may proceed with claim not asserted in pleadings

without amending complaint); D. Federico Co. v. New Bedford

Redevelopment Authority. 723 F.2d 122, 126 (1st Cir. 1983)

(holding that amendment of complaint to conform to evidence is

not necessary, and in any event should be liberally allowed);

Moore v. City of Paducah. 790 F.2d 557, 561 (6th Cir. 1986)

(reversing denial of leave to amend complaint on ground that

"cases should be tried on their merits rather than the

technicalities of pleadings"). The plaintiffs offered to amend

their complaint to articulate the discovered facts as they

related to the Patterson standard. (R. 263: Plaintiffs' Reply at

4). The district court, however, apparently viewed amendment as

unnecessary. If this Court narrowly reads the district court

opinion as having dismissed the § 1981 claims on the basis that

facts were inadequately pleaded, however, the proper course would

be to remand with directions to the district court to permit

amendment of the pleadings, con.-istent with Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 15(b).

7

Id. In 1975, both were transferred to work as mechanics in

Roadway's garage in Toledo, Ohio. Id.'/ For 10 years, both worked

capably in that job. (R. 192: Appendix I, Thompson Dep.

7/22/87, at 49-50)'.3

On August 22, 1986, Roadway required both Rivers and Davison

to attend disciplinary hearings on their accumulated work record

without proper notice. (R. 192: Appendix I, Guy Dep. 8/12/87, u

at 151; R. 218: Complaint, at 5 11). Although Roadway is

contractually required to provide prior written notice of such

hearings, and routinely did so for white employees, it did not

provide either Rivers or Davison with such notice. Davison was

simply called into the office at the end of his shift without any

prior notice, verbal or written, that a hearing would be held

that day. (R. 192: Appendix I, Davison Dep. 7/20/87, at 187-

88). He protested that he had not received proper notice. (R./

192: Appendix I, Guy Dep. 8/12/87, at 148). Rivers' foreman

verbally informed him during the early hours of August 22 that a

disciplinary hearing would be held for him later that morning.

(R. 192: Appendix I, Rivers Dep. 7/14/87, at 297-299; Guy Dep.

x/8/12/87, at 149). He also received no written notice. (R. 192:

Appendix I, Rivers Dep. 7/14/87, at 299)i

6/16/87, at 11). Each worked his way up to become a mechanic.

There were only four black employees working in the

Toledo garage in 1986: plaintiffs Rivers, Davison and Harvis,

and a black union steward who had been discharged in 1984 for

refusing to have his picture taken in circumsta* ces an arbitrator

described as showing "a callous disregard for the personal rights

of minority employees." That employee was reinstated.

8

The purpose of a disciplinary hearing is to give an

employee, represented by the union, an opportunity to respond to

the infractions with which Roadway has charged him. Notice of a

hearing is critical because it gives the employee time both to

prepare a defense and to reform his behavior.4 Because Rivers

and Davison had not received proper notice, neither of them

attended. The Company proceeded despite their absence. At the

conclusion of the hearings, Roadway suspended each employee for

two days for minor infractions, such as "wasting time" and

wearing improper shoes to work.

Both employees then filed grievances challenging their

l/'suspensions. (R. 218: Complaint, at f 11). The grievances were

heard by the Toledo Local Joint Grievance Committee (TLJGC) on

September 23, 1986. (R. 192: Appendix I, Rivers Dep. 7/14/87,

at 317— 18). The TLJGC was comprised of six members, three each

from union and management, including co-chairs. Rivers and

Davison contended that the Company failed to give proper notice,

and instead discriminatorily held prompt hearings for these black

employees but not for whites. (R. 192: Appendix I, Rivers Dep.

Under the collective bargaining agreement, the Company

may_consider only the cumulative disciplinary record of the

employee within the nine months immediately preceding the

hearing. (R. 192: Appendix II, Local 20/Harvis Ex B-63, Article

X; R. 192: Appendix I, O'Neill Dep. 8/13/87 at 74). Thus, as

time passes between a hearing request and the hearing itself,

some earlier disciplinary infractions may become time-barred and

therefore no longer be subject to discipline. If an employee's

disciplinary record is improving — such that old infractions

drop off his record at a greater rate than new ones accumulate -

- he will benefit from the passage of time before a hearing is

held. (R. 192: Appendix I, Toney Dep. 8/17/87, at 159).

9

They presented examples of white employees who were not hastily

brought in for hearings as they had been, notwithstanding that

Roadway's requests that the union agree to dates for hearings on

their disciplinary records had been pending for months. Id.5

The TUGC ruled in plaintiffs' favor, determining that

"[bjased on improprieties the claim of the union is upheld." (R.

192: Appendix II, Plaintiffs' Ex. 113, 114). The committee

reversed the suspensions and awarded them back pay for the two

days they were suspended. One of the committee co-chairs later

reported that the TLJGC had reversed the suspension based on the

plaintiffs' discrimination argument. (R. 192: Appendix I,

Rivers Dep. 7/14/87 at 335; Davison Dep. 7/15/87, at 114-15,^

Davison Dep. 7/20/87 at 220, 252; McCord Dep. 9/3/87 at 287)

Roadway Labor Relations Manager James O'Neill became enraged

upon hearing of the TLJGC determination, and vowed to hold

7/14/87 at 321-22, 324; McCord Dep. 9/3/87, at 285-86, 293).

While the Company precipitously convened hearings on

plaintiffs, it generally gave proper notice and scheduled

hearings for white employees on a more leisurely basis, with

weeks passing between a request for a hearing and the hearing

itself. Roadway first requested on August 1, 1986 that Rivers'

hearing be scheduled, (R. 192: Appendix II, Plaintiffs' Dep. Ex.

65), and first requested on July 14, 1986 that Davison's be

scheduled. (R. 192: Appendix II, Plaintiffs' Dep. Ex. 64). The

time between the request and the hearings was thus 22 and 39

days, respectively. In contrast, the time between the request

and the hearing of the eleven white employees for whom hearings

were held during 1986 and early 1987 averaged 99 days, with only

one white employee having a more prompt hearing than both

plaintiffs, and one other more prompt than Davison. See R. 192:

Appendix II, Plaintiffs' Exs. 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77,

78, 79, 80, 81. The hasty scheduling of plaintiffs' hearings

r’-»prived them of both the required notice and of the benefits of

later hearings that white employees routinely enjoyed.

■H< i (

10

vcw sc f

hearings on plaintiffs again within 72 hours. (R. 192: Appendix

\ \ /I, McCord 9/3/87 Dep. , at 256; Rivers 7/14/87 Dep. at'327; Guy

8/12/87 Dep., at 168-69). O'Neill was "hollering," and was

visibly upset. (R. 192: .Appendix I, McCord 9/3/87 Dep., at 286;

Guy 8/12/87 Dep., at 163—69). Plaintiffs contend that O'Neill

sought to retaliate against them for their success in the

grievance proceeding.

Roadway did in fact convene disciplinary hearings on Davison

and Rivers again within three days of the September 23, 1986

TLJGC decision with the discriminatory intention of discharging

them. This time Roadway attempted to notify them of the hearings

by leaving papers at their workstations. (R. 192: Appendix I,

'% y*\ ' j ' i 'ORivers Dep. 7/14/87, at 355—54). This notice fell short of the

standard procedure of sending the notice by certified mail, which . n ,

TcW'j . *7 nplaintiffs believed was required. (R. 192: Appendix I, Toney x \,uos-1 /

t>{_{>■ M / ( H , of f\'7dT ,1 aL ID 20, Rivers Dep. 7/14/87, at 347, 378-79).

Davison and Rivers again declined to attend the hearings on

grounds of improper notice, and again the hearings were held in

their absence. The second disciplinary hearings were conducted

by another member of Roadway management, Robert Kresge, but

O'Neill nonetheless personally attended. (R. 192: Appendix I,

[/ /O'Neill Dep. 8/13/87, at 63, 69). As a result of the hearings,

plaintiffs were discharged on/September 26, 1986. (R. 218:

Complaint, at fj[ 1, 7, 16)\/ Nobody informed either Rivers or

Davison that failure to attend the second disciplinary hearing

would cause his discharge. (R. 192: Appendix I, Davison Dep.

Y' v '

fe. \*?io

\A(â9 ft/'1 *S

11

7/20/87, at 227, 232; Davison Dep. 8/20/87, at 82-83). Yet the

Company asserted that the employees' failure to attend the

hearings in disobedience of what the Company characterizes as a

"direct order" was the basis for its decision immediately to

discharge them. Rivers and Davison contend that non-attendance

was a pretextual reason given for the discriminatory decision to

discharge them for their prior successful assertion of their

right to notice of hearings on an equal basis with white

employees.

12

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Retaliatory discharge under the particular factual

circumstances of this case violates the § 1981 right to "enforce

contracts" on racially neutral grounds.

A. Plaintiffs do not contend that all race-based

retaliatory discharge violates § 1981's enforcement clause, but

merely that discriminatory retaliation for enforcing contract

rights does. What plaintiffs here sought was enforcement of

rights created by contract, not of rights derived from other

sources. Patterson eliminates claims of retaliation for

exercising rights unrelated to the specific § 1981 rights to

"make and enforce contracts," not claims of discriminatory

retaliation for the exercise of those two rights.

B. The fact that Roadway's discriminatory retaliation,

calculated to punish and deter the racially neutral enforcement

of plaintiffs' contracts, took place after plaintiffs'

enforcement effort does not remove it from § 198r.'s coverage.

Discharging an employee for having engaged in protected conduct

is no less an infringement of that conduct than discharge in

anticipation of such conduct.

C. Moreover, retaliatory discharge is not immune from suit

under the enforcement clause simply because it does not also

violate the right to make contracts. Contract enforcement

necessarily takes place after the contract is made. Patterson's

limitation of the right to make contracts to the contract

formation stage expressly did not restrict the enforcement right

13

ARGUMENT

ROADWAY VIOLATED PLAINTIFFS' § 1981 RIGHT TO

ENFORCE THEIR CONTRACT FREE FROM RACIAL

DISCRIMINATION

Roadway's discriminatory punishment of plaintiffs Rivers and

Davison for attempting to enforce their contracts on an equal

basis with white employees violates plaintiffs' "right ... to ...

enforce contracts" under 42 U.S.C. § 1981.6 Plaintiffs' § 1981

enforcement claims are governed by Goodman v. Lukens Steel. 482

U.S. 656 (1987), and their viability is unaffected by Patterson

v. McLean Credit Union. 491 U.S. 164. In Goodman. the Court held

that allegations that the defendant union discriminatorily

refused to process black employees' discrimination grievances

stated a claim of violation of the § 1981 right to enforce

contracts. Goodman applies to employers as well as unions, and

prohibits interference with employees' efforts to enforce their

contract rights against discriminatory infringement.

Goodman's construction of the § 1981 enforcement right

remains controlling. Indeed, the Court in Patterson explicitly

reaffirmed Goodman's holding. The Court held that the § 1981

right to enforce contracts does not cover on-the-job racial

Section 1981 states:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal

benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of

persons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens,

and shall be subject to like punishment, pains,

penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every

kind, and to no other.

14

harassment, 491 U.S. at 180, but emphasized that the enforcement

right "covers wholly private efforts to ... obstruct nonjudicial

methods of adjudicating disputes about the force of binding

obligations." Id. at 177.

Roadway retaliated against Rivers and Davison in precisely

the way that § 198l's enforcement prong prohibits. Here, as in

Goodman, plaintiffs used the nonjudicial grievance arbitration

provided for under their collective bargaining agreement as a

means to enforce their contract rights.7 The rights they sought

to enforce were contract rights, and not rights established by

other sources not addressed by § 1981. They asserted their

contractual right to properly scheduled hearings with prior

written notice was violated on racially discriminatory grounds.

While Roadway gave timely and proper notice to white employees,

it precipitously convened disciplinary hearings for Rivers and

Davison in order to mete out swifter and harsher discipline

.•'gainst them than against white employees. As a result of their

successful efforts in the grievance proceeding, however,

plaintiffs were not rewarded with enjoyment of contract rights

equal to those of white employees, but instead were promptly

discharged. Because their discharge in retaliation for enforcing

their contract rights violates § 1981, the decision of the

district court must be reversed.

A labor-management arbitration panel is indisputably a

;;nonjudicial method[] of adjudicating disputes about the force of

binding obligations." Patterson. 491 U.S. at 177.

15

A. Roadway's Retaliation Against Plaintiffs for

Filing Grievances to Enforce Their Contract

Rights, as Distinct From Rights Derived From Other

Sources, Remains Prohibited By Section 1981 Even

After Patterson

The conduct discriminatorily penalized by Roadway's

retaliation was plaintiffs' enforcement, through arbitration, of

their equal contract rights. Courts since Patterson have

consistently distinguished retaliation claims based on

infringement of the right to enforce statutory rights, which are

not actionable, from those based on infringement of the right to

enforce contract rights, which are. The district court in this

case overlooked this crucial distinction in dismissing

plaintiffs' § 1981 enforcement claim.

Several courts of appeals have rejected § 1981 claims

because they did not allege the kind of retaliation involved

here. In Carter v. South Central Bell. 912 F.2d 832, 840 (5th

Cir. 1990), cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 2916 (1991), the Fifth

Circuit distinguished claims of retaliation for asserting

contract rights, which remain actionable under § 1981, from

claims of retaliation for filing EEOC charges, which the court

held may be pursued exclusively under Title VII. It was only

because the plaintiff in Carter "was asserting a right given to

him by the Civil Rights statutes, not by his employment contract

with SCB," that his "right to enforce his employment contract was

not impaired" by his subsequent discharge. In Chambers v.

Southwestern Bell Telephone Co.. 917 F.2d 5, 7 (5th Cir. 1990),

petition for cert, filed (May 14, 1991) (No. 90-1776), another

16

Fifth Circuit panel elaborated on Carter to hold that, under

Patterson. "[u]nlike constructive and discriminatory discharges,

retaliatory discharge may implicate the right to enforce

contracts. Retaliation or threats of retaliation calculated to

deter the legal enforcement of contractual rights falls within

the express ambit of $ 1981." (emphasis added).

In McKnight v. General Motors Coro.. 908 F.2d 104, 111 (7th

Cir., 1990), cert, denied 111 S. Ct. 1306 (1991), the Seventh

Circuit similarly commented that "[r]etaliation or a threat to

retaliate is a common method of deterrence, and if what is sought

to be deterred is the enforcement of a contractual right, then,

we may assume, the retaliation or threat is actionable under

section 1981 as interpreted in Patterson. provided that the

retaliation has a racial motive." The plaintiff in McKnight,

however, alleged that he had been discharged in retaliation for

having filed statutory race discrimination claims with the

Wisconsin Civil Rights Commission and the state court. The court

held that he therefore did not have a § 1981 enforcement claim

because "General Motors did not interfere with contractual

entitlements." Id. at 112 (emphasis added). Similarly, in

Sherman v. Burke Contracting, Inc.. 891 F.2d 1527, 1535 (11th

Cir. 1990), the Eleventh Circuit held that an employer's

retaliation against an employee for filing a charge with the EEOC

under Title VII did not violate the right to enforce contracts

17

because the discrimination was "unrelated to specific contract

rights."8

Thus, the court in Von Zuckerstien v. Argonne National Lab..

citing McKniaht and Sherman. permitted plaintiffs to proceed to

trial on their § 1981 claims that "defendants specifically-

retaliated against them for pursuing (or intending to pursue)

their contract claims in the internal grievance forum." 760 F.

Supp. 1310, 1318 (N.D. 111. 1991) (emphasis in original).9

Other Circuit court cases affirming dismissals of

retaliatory discharge claims have not specifically distinguished

interference with contract enforcement from interference with

statutory enforcement, but none has dealt with the former type

claim which plaintiffs here allege. The plaintiff in Williams v.

First Union Nat11 Bank of N.C.. 920 F.2d 232 (4th Cir. 1990),

cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 2259 (1991), asserted that his employer

subjected him to discriminatory working conditions in retaliation

for having filed EEOC charges.

The retaliation alleged in Hill v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber.

Inc.. 918 F.2d 877 (10th Cir. 1990), was in response to

plaintiff's having "complained to management ... about racial

slurs and other incidents of racial harassment in an attempt to

bring about a more harmonious relationship between the bargaining

unit employees and management." Id. at 880. The Court held that

"[s]ince plaintiff's advocacy was not protected under section

1981, his discharge, even if in retaliation for such advocacy,

was not actionable under section 1981." Id.

In Overbv v. Chevron U.S.A.. Inc.. 884 F.2d 470 (9th Cir.

1989), the plaintiff alleged that he was discharged in

retaliation for refusing to consent to a search of his person.

He filed an EEOC charge, which he concedes he then withdrew

voluntarily. The Court held that the employer had created no

impediment to Overby's right under § 1981 to enforce his

contract. Id. at 473.

Other district courts have articulated the same

standard, stating that § 1981 retaliation claims are subject to

dismissal only where they are not based on interference with

efforts to enforce contract rights. In Dash v. Equitable Life

Assur. Soc. of U.S.. 753 F. Supp. 1062, 1067 (E.E.N.Y. 1990), the

court dismissed the § 1981 retaliation claims only because

"plaintiff has not alleged that his discharge impaired his

18

Rivers and Davison, like the plaintiffs in Von Zuckerstein.

contend that they were retaliated against for enforcing their

contractual rights. Their claims are distinct from those based

on efforts to enforce statutory rights against nondiscrimination

by filing charges with state or federal agencies. Plaintiffs'

claims are also unlike claims of retaliation for exercising other

rights, such as First Amendment rights of association or

expression. Rivers and Davison contend that the abruptly

convened disciplinary sessions for black employees, carried on

without the contractually required prior written notice to

plaintiffs, constituted intentionally discriminatory breaches of

contract. When plaintiffs were deprived of the contract rights

to fair disciplinary procedures that white employees enjoyed,

they sought to enforce their rights through the grievance

procedures established for that purpose. Such efforts to enforce

contracts are precisely what § 1981 explicitly does protect.

ability to enforce contractual rights either through this court

or otherwise." The court emphasized, however, that retaliatory

discharge claims are actionable where "the discharge is alleged

to have actually obstructed plaintiff's access to the courts or

to some other process for the resolution of contract disputes."

See also. Russell v. District of Columbia. 747 F. Supp. 72

(D.D.C. 1990) (dismissing retaliation claim because plaintiff

"did not seek to enforce contractual rights ... rather, he sought

'to enforce his rights under antidiscrimination laws'") (quoting

McKniqht. 908 F.2d at 112); Kozam v. Emerson Elec. Co.. 739 F.

Supp. 307 (N.D. Miss. 1990), aff'd. 928 F.2d 401 (5th Cir. 1991)

(reading Sherman as "leav[ing] open the possibility of a

retaliation claim under § 1981 where the EEOC complaint

[triggering the discharge] involves a specific contractual right,

as where the contract of employment itself provides that the

employer will not discriminate on the basis of race," but

dismissing plaintiff's retaliation claim because "no right

arising from his contract" was involved).

19

Roadway's retaliation against plaintiffs for seeking racially

neutral contract enforcement thus falls squarely within § 1981.

Patterson's restriction of the contracts clause to the two rights

it explicitly provides — the right to make contracts, and the

right to enforce them — does not affect this aspect of the

statute's coverage.10

B. Roadway's Discharge of Rivers and Davison

Even After They Prosecuted Their Grievances

Violates Their Right to Enforce Their

Contracts

Roadway's discharge of Rivers and Davison violated their

right to enforce their contracts notwithstanding that it occurred

after they "successfully" prosecuted their grievance. The

district court correctly acknowledged that if a plaintiff were

denied access to a grievance proceeding, he would have been

deprived of "precisely what is protected under the 'right to ...

enforce contracts' provision of § 1981," (R. 266: Memorandum

and order, at 4). This description of the enforcement right is,

however, far too narrow. The court erred in distinguishing an

employer's refusal to allow presentation of a grievance from its

post hoc punishment of a plaintiff who has presented one.

In dismissing plaintiffs' retaliatory discharge claims,

the district court purported to act consistently with prior

decisions of other district courts. (R. 266: Memorandum and

Order at 4, citing, Danaerfield v. The Mission Press. 1989 U.S.y

Dist. LEXIS 8985 (N.D. 111. 1989); Hall v. Countv of Cook. 1989 /

U.S. Dist. LEXIS 9661 (N. D. 111. 1989)). The decisions the

district court relied on, however, did not involve dismissal of

retaliation claims based on efforts to secure non-discriminatory

enforcement of contract rights, and are thus inapposite to this case.

20

Discharging an employee as he walks out of his grievance hearing,

as opposed to on his way in, is equally effective punishment for

filing a grievance, and is therefore equally an infringement of

his right to grieve to enforce his contract.

Retaliation by its nature takes place in response to, and

therefore after, protected conduct such as the enforcement of

contract rights. Cases on retaliation prior to Patterson

authorized claims without regard to the timing of the

retaliation. See. e.q.. Harris v. Richards Mfg. Co.. 675 F.2d

811, 812 (6th Cir. 1982); Winston v. Lear Siealer Inc.. 558 F.2d

1266, 168-70 (6th Cir. 1977). Patterson did not affect this

aspect of § 1981 doctrine. Courts' repeated acknowledgements,

even after Patterson, that certain retaliation claims remain

viable is a clear repudiation of the district court's categorical

assumption that only preemptive, or anticipatory, obstruction of

contract enforcement is prohibited by § 1981. See Carter. 912

F.2d at 840, Chambers. 917 F.2d at 7, Sherman. 891 F.2d at 1535,

McKniaht. 908 F.2d at 111.

Affirmance of the district court's interpretation of § 1981

as prohibiting only successful efforts to bar initial access to

an adjudicative forum would yield unacceptable results. An

employer adopting a policy of promptly discharging any employee

who grieved a discriminatory denial of contract rights would

clearly violate the § 1981 enforcement guarantee. Yet under the

district court's standard, as long as the employer gives an

employee a pro fcnna grievance hearing, the employer escapes

21

§ 1981 liability. The right to enforce contracts is not a purely

formal right to go through the motions of judicial or non

judicial dispute resolution. If the right is to have meaning in

protecting employees' equal enforcement of their contracts,

interference with the enforcement of contracts on racially

neutral terms must be covered by the statute regardless of how or

when it is accomplished.

C. Roadway's Retaliatory Discharge Violates

Plaintiffs' § 1981 Right to Enforce Their

Contracts Even if Patterson Precludes Discharge

Claims Based on The Right to Make Contracts

If interference with contract enforcement is carried out by

means of discharge, it is no less actionable simply because that

discharge may not also violate the § 1981 right to make

contracts.11 The Patterson Court's limitation of the scope of

Plaintiffs remain convinced that the § 1981 right to

make contracts, correctly interpreted, does prohibit

discriminatory discharge. They acknowledge that a panel of this

Circuit, consistently with several other federal courts of

appeals, has ruled that Patterson precludes claims of

discriminatory discharge based on the § 1981 right to make

contracts. Prather v. Dayton Power & Light Co.. 918 F.2d 1255,

1256-58 (6th Cir. 1990), petition for cert, filed. 59 U.S.L.W.

3687 (U.S. Mar. 26, 1991); Taggart v. Jefferson Ctv. Child

Support. 935 F.2d 947 (8th Cir. 1991); Gersman v. Group Health

Assoc.. 931 F.2d 1565 (D.C. Cir. 1991); Trujillo v. Grand

Junction Regional Center. 928 F.2d 973, 976 (10th Cir. 1991);

Williams v. First Union National Bank. 920 F.2d 232, 233-34 (4th

Cir. 1990), cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 2259 (1991); Tompkins v.

DeKalb County Hosp. Auth.. 916 F.2d 600, 601 (11th Cir. 1990)

(per curiam); Gonzalez v. Home Ins. Co.. 909 F.2d 716, 722 (2d

Cir. 1990); McKnight v. General Motors Corp.. 908 F.2d 104, 108-

09 (7th Cir. 1990), cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 1306.

There is, however, some suppo-t in the law for the view that

these cases were wrongly decided. See Prather v. Dayton Power &

Light Co.. 918 F.2d at 1259 (Boggs, J., dissenting); Hicks v.

22

§ 1981 to discrimination at the contract-formation stage was a

construction of the right to make contracts, not of the right to

enforce them. 491 U.S. at 176. The district court's holding

that "§ 1981 does not apply to discriminatory discharges since a

discharge is conduct which occurs after the for ion of a

contract," (R. 266: Memorandum and Order at 3), is thus an

erroneous statement of the Supreme Court's holding. The Court

condemned only "[i]nterpreting § 1981 to cover postformation

conduct unrelated to an employee's right to enforce her

contract." 491 U.S. at 165. Contract enforcement necessarily

Brown Group. 902 F.2d 630 (8th Cir. 1990), overruled by Taggart.

935 F.2d 947; see id. at 949 (McMillian, Lay, Arnold,

dissenting); McKnight v. General Motors Coro.. 908 F.2d at 117

(Fairchild, J., dissenting). Plaintiffs therefore hereby

preserve their claim that their discharge violated their § 1981

right to make contracts in the event that a majority of the

judges in this Circuit, the Supreme Court, or Congress ultimately

agrees with them. This Court sitting en banc has not yet had an

opportunity to consider this question. The Supreme Court has

explicitly acknowledged that the question is an open one and was

not resolved by its decision in Patterson. See L\ ile v.

Household Manufacturing. 110 S. Ct. 1331, 1336 n. j (1990); id.

at 1338 (O'Connor, concurring). Moreover, Congress last term

enacted legislation stating that § 1981 prohibits discriminatory

discharge, Civil Rights Act of 1990, S. Con. Res. 2104, § 12,

101st Cong., 2d Sess. (1990), and although the President vetoed

the legislation, he did so on grounds unrelated to Congress'

interpretation of § 1981, stating that he, too, disagreed with

the Supreme Court's restriction of § 1981 to discrimination at

the contract formation stage. Text of Veto Message of President

Bush, Oct. 22, 1990, at 1. (Attachment A).

If this Court were inclined to determine that plaintiffs'

retaliatory discharge claim is no longer viable under Patterson.

it should at least hold the appeal in abeyance until Congress has

acted on the proposed Civil Rights and Women's Equity in

Employment Act of 1991, H.R. 1, § 110, 102d Cong., 1st Sess.

(1991). See Northern Pipeline Construction Co. v Marathon Pipe

Line Co.. 458 U.S. 50, 88 (1982).

23

occurs after the contract has been formed. Thus, whether or not

a discriminatory discharge violates the § 1981 right to make

contracts, using discharge as a means of penalizing employees who

seek to enforce their contracts is covered by § 1981.

The district court erroneously suggests that Patterson

eliminated § 1981 enforcement claims where plaintiffs also have

breach of contract claims. (R. 266: Memorandum and Order at

4) 1̂ /what the Supreme Court held in Patterson is that a

plaintiff cannot "assert, by reason of the breach alone. that he

has been deprived of the same right to enforce contracts as is

enjoyed by white citizens." 491 U.S. at 183 (emphasis added).

Breach of contract thus does not in itself amount to deprivation

of the right to enforce a contract. Rather, a § 1981 enforcement

claim depends on precisely the kind of additional facts present

here: discriminatory adverse action by the employer hindering

the employee's ability to rectify the breach through arbitration.

The only reason that it is important to be protected in enforcing

contract rights is that they may be breached. Section 1981

provides a specific remedy, in addition to those provided by

contract law, for cases such as this one where an employer

The district court held that "'bootstrapping' of the

actual breach of contract claim into a claim that plaintiffs were

deprived of the right to enforce the contract was rejected in

Patterson." The Supreme Court's reference to "bootstrapping" had

nothing to do with the enforcement right: the Court rejected as

strained an attempt to convert a challenge to the continuing

conditions of employment into a claim that the employer refused

at the outset to make a contract on neutral terms. 491 U.S. at 184.

24

discriminatorily breaches contract rights, and then, in a further

attempt to

employee's

effectuate its discrimination, interferes with the

grievance seeking to redress that breach.

25

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the decision below should be

vacated and the case should be remanded to the district court for

further proceedings and a jury trial on the merits of plaintiffs'

§ 1981 claim.

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

ERIC SCHNAPPER

CORNELIA T.L. PILLARD

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

ELLIS BOAL

925 Ford Building

Detroit, MI 48226

August 12, 1991

26

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This will certify that I have this date served counsel

for defendant in this action with true and correct copies of the

foregoing Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellants by placing said copies

in the U.S. Mail at New York, New York, First-Class postage

thereon fully prepaid addressed as follows:

John Landwehr

800 United Savings Building

Toledo, Ohio 43604-1141

Executed this day of August, 1991 at New York, New

York.

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 91-3348

JAMES T. HARVIS, JR.,

Plaintiff.

MAURICE RIVERS and

ROBERT C. DAVISON

Plaintiffs-Appellants.

v.

ROADWAY EXPRESS, INC.

Defendant-Appellee.

APPELLANT'S DESIGNATION

OF APPENDIX CONTENTS

Appellant, pursuant to Sixth Circuit Rule 11(b), her-acy designates

the following filings *in the district court's record as items to

be included in the joint appendix:

DESCRIPTION OF ENTRY DATE RECORD ENTRY NO.

1. Docket Sheet for Action

No. C 86-7955

12/22/86 N/A

2 . First Amended Complaint 9/28/87 218

3 . Memorandum and Order 1/19/90 266

4 . Notice of Appeal --■1/3T/-6HD 4| 111̂11 N/A

5. Order to Show Cause 7/10/89 257

27

DESCRIPTION OF ENTRY DATE RECORD ENTRY NO.

6. Appendix I of Plaintiff in 8/29/88 192

Opposition to Summary

Judgment ("Appendix"),

Davison Dep. 7/15/87 .

at 44-45, €-20-,—€52;

7/20/87 at 187-88, 220,

227, 232, 252; 8/20/87

at 82-83.

7. Appendix I, Rivers Dep.

6/16/87 at 11; 7/14/&Z

at 297-99, -SaaggSB ,-'"321- 3m

322, 324, 327, 335, 347,

353-54, 378-79.

8. Appendix I, Thompson Dep.

7/22/87 at 49-50.

9. Appendix I, Guy Dep.

8/12/87 at 148-49, 151,

168-69.

10. Appendix I, O'Neill Dep.

8/13/87 at 63, 69, 74.

11. Appendix I, McCord Dep.

9/3/87 at 285-87, 293.

12. Appendix I, Toney Dep.

10/1/6-7 at -19-3-0. i r -

13. Appendix II, Local 20/

Harvis Ex. B-63.

8/29/88 192

8/29/88 192

8/29/88 192

8/29/88 192

8/29/88 192

8/29/88 192

8/29/88 192

28

ATTACHMENT A

TO THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES:

I am today returning without ay approval S. 2104, the

"Civil Rights Act of 1990." I deeply regret havihg to take this

action with respect to a bill bearing such a titli, especially

since it contains certain provisions that I strongly endorse.

Discrimination, whether on the basis of race* national

origin, sex, religion, or disability, is worse than wrong. It

is a fundamental evil that tears at the fabric of our society,

and one that all Americans should and must: oppose. That

requires rigorous enforcement of existing antidiscrimination

laws, it also requires vigorously promoting new measures such

as this year's Americans with Disabilities Act, ^ich for the

first time adequately protects persons with disabilities against

invidious discrimination.

one step that the Congress can taka to fight discrimination

right nav iS to act promptly on the civil rights bill that I

transmitted on October 20, 1990. This accomplishes the stated

purpose of S. 2104 in strengthening our Nation's laws against

employment discrimination- Indeed, this bill contains several

important provisions that are similar to provisions in S. 2104:

o Both shift the burden of proof to the employer on the issue

iof "business necessity" in disparate impact'cases.

Both create expanded protections against on-the-job racial

discrimination by extending 42 U.S.C. 1981 io the

performance as well as the making of contracts.

Both expand the right to challenge discriminatory seniority

systems by providing that suit may be brougjit when they

cause harm to plaintiffs.

Both have provisions creating new monetary remedies for

the victims of practices such as sexual harassment.

(The Administration bill allows equitable awards up to

$130,000.00 under m i s new mor-tary provision, in addition

-o existing remedies under Title VII.)

Both have provisions ensuring that employees can be held

liable if invidious discrimination was a motivating factor

in an employment decision.

2

Q Both provide Cor plaintiffs in civil rights cases to

receive expert witness fees under the ssiae standards that

apply to attorneys fees.

o Both provide that the Federal Government, wWen it is a

defendant under Title VII, will have the sane obligation to

t I

pay interest to compensate for delay in payment as a

nonpublic party. The filing period in ;*uch 'actions is also

lengthened,

o Both contain a provision encouraging th3 use of alternative

i

dispute resolution mechanisms.

The congressional majority and I are on common ground regarding

these important provisions. Disputes about other, controversial

provisions in S. 2104 should not be allowed to impede the

enactment of these proposals.

Along with the significant similarities between my

Administration's bill and s. 2104, however, there are crucial

differences. Despite the use of the term "civil rights" in the

!

title of S. 2104, the bill actually employs a maze of highly

legalistic language to introduce the destructive force of quotas

into our Nation's employment system. Primarily through

provisions governing cases in which employment pfcactices are

alleged to have unintentionally caused the clj.spreporticnate

exclusion of members of certain groups, S. 2104 fcreates powerful

incentives for employers to adopt hiring and promotion quotas.

These incentives are created by the bill1s new and very

technical rules of litigation, which will it difficult for

employers to defend legitimate employment practices. In many

cases, a defense against unfounded allegations will be

impossible. Among other problems, the plaintiff often need not

even show that any of the employer's practices caused a

significant statistical disparity, in other cades, the

employer's defense is confined to an unduly narrow definition of

3

"business necessity" that is significantly more restrictive than

that established by the Supreme Court in Griggs ind in two

decades of subsequent decisions. Thus, unable t4 defend

legitimate practices in court, employers will be I driven to adopt

quotas in order to avoid liability.

proponents of S. 2104 assert that it is needed to overturn

the supreme Court's wards Cove decision and restore the law that

had existed since the Griggs case in 1971. S. 2io4, however,

does not in fact codify Griggs or the Court's subsequent

decisions prior to Wards Cove. Instead, S. 2104 engages in a

sweeping rewrite of two decades of Supreme Court jurisprudence,

using language that appears in no decision cf the Court and that

is contrary to principles acknowledged even by Justice Stevens'

dissent in Wards Cove; "The opinion in Griggs made it clear

that a neutral practice that operates to eweludaiminorities is

nevertheless lawful if it serves a valid buaines^ purpose.”

I am aware of the dispute among lawyers aboit the proper

interpretation of certain critical language used in this portion

of S. 2104. The very fact of this dispute suggests that the

bill is not codifying the law developed by the Supreme Court in

Griggs and subsequent cases. This debate, moreover, is a sure

sign that £. 2104 will lead to years -- perhaps decades — of

uncertainty and expensive litigation. It is neither fair nor

sensible to give the employers of our country a difficult choice

between using quotas and seeking a clarification of the law

through costly and very risky litigation.

£. 2104 contains several other unacceptable: provisions

as well. One section unfairly closes the court*’, in many

instances, to individuals victimized by agreements, to which

they were not a party, involving the use of guotias. Another

section radically alters the remedial provision^ in Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, replacing measured designed to

foster conciliation and settlement with a naw sclheme modeled ou

a tort system widely acknowledged to be in a st^te of crisis.

I

Th* bill also contains « number of provisions that will craate

unnecessary and inappropriate incentives for litigation. These

include unfair retroactivity rules; attorneys fee provisions

that will discourage settlements; unreasonable new statutes of

limitation; and a -rule of construction" that will make it

extremely difficult to know how courts ean be expected to apply

the lav. in order to assisrtj the Congress regarding legislation

in this area, I enclose herewith a memorandum from the Attorney

General explaining in detail, the defects that make S. 2104

unacceptable.

Our goal and our promise has been equal opportunity and

equal protection under the Law. That i s a bedrock p rin cip le

from which we cannot m treaL The temptation to support a

b i l l - any b i l l - simply because i t s t i t l e includes the words

" c iv il rights" i s very strbLg. This impulse i s not e n tire ly

bad. Presumptions have tetj often run the other way, and our

Nation's h istory on ra c ia l questions cautions against

complacency. But when our e ffo r ts , however w ell in ten tions* ,

r esu lt in quotas, equal opportunity i s not advanced but

thwarted. The very commitment to ju s t ic e and equality that is

offered as the reason why |h i s h i l l should be signed requires me

to veto i t .

Again, I urge the comjress to act on my legislation b*f<

adjournment. In order truly to enhance equal opportunity,

however, the Congress must also take action in several related

areas. The elimination ofl employment discrimination is a vital

element in achieving the American dream, but it is not enough-

The absence of discrimination will have little concrete meaning

and the members of all groups have the

id to qualify for those jobs. Nor can

unless jobs are availab le

s k i l l s and education need*

the future if they grow

hopelessness•

we expect th at our young people w il l work hard to prepara for

in a climate of violence, drugs, and

In order to address these problems, attention

to measures that promote accountability and parentu

the schools; that strengthen the fight against, vioL

and drug dealers in our inner cities; and that; hel;?

poverty and inadequate housing. We need initiative

empower individual Americans and enable them to re

of their lives, thus helping to make our country's

opportunity a reality for all. Enactment of *uch

along with my Administration's civil rights bill,

real advances for the cause of equal opportunity.

must be given

.1 choice in

ent criminals

to combat

:s that will

ijslaim control

promise of

initiatives,

will achieve

the white h o u s e,

October 22, 1990.