Nash v. Sharper Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1956

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Nash v. Sharper Brief of Appellants, 1956. 5c08a509-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f60bf815-6a63-4a17-9b58-5089f1f9d407/nash-v-sharper-brief-of-appellants. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

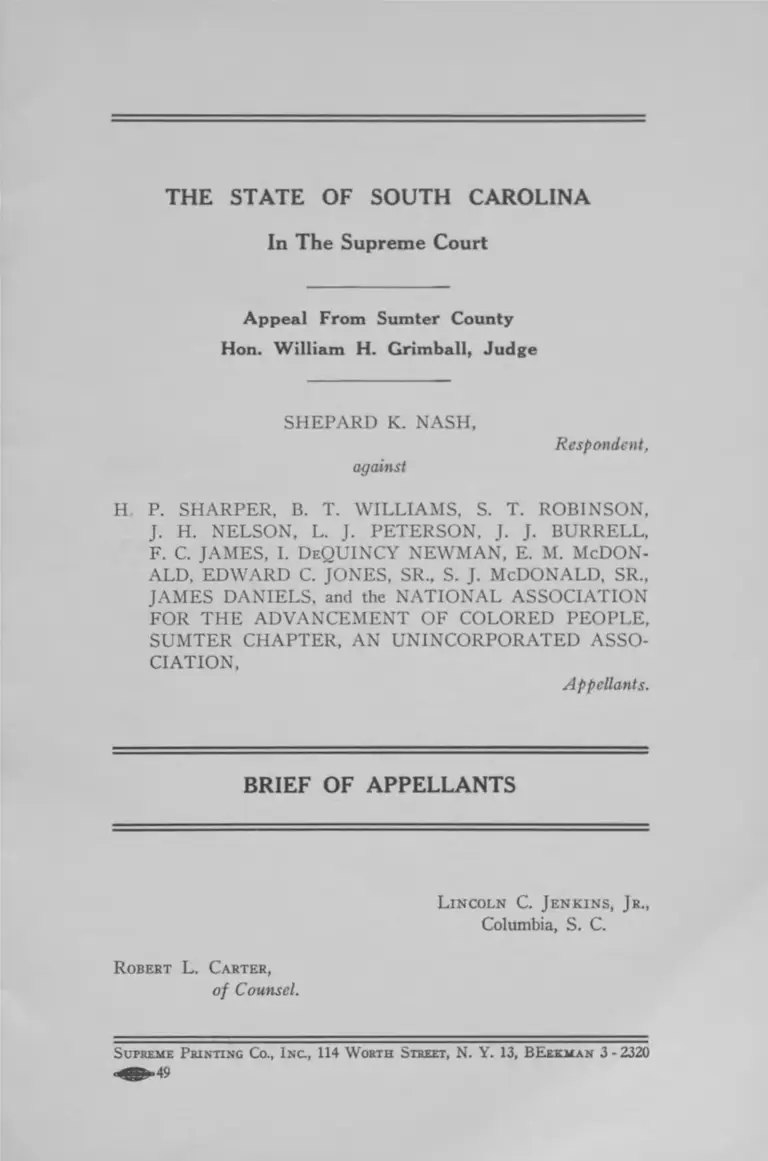

THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA

In The Supreme Court

Appeal From Sumter County

Hon. William H. Grimball, Judge

SHEPARD K. NASH,

against

Respondent,

H P. SHARPER, B. T. WILLIAMS, S. T. ROBINSON,

J. H. NELSON, L. J. PETERSON, J. J. BURRELL,

F. C. JAMES, I. DeQUINCY NEWMAN, E. M. MCDON

ALD, EDWARD C. JONES, SR., S. J. McDONALD, SR„

JAMES DANIELS, and the NATIONAL ASSOCIATION

FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE,

SUMTER CHAPTER, AN UNINCORPORATED ASSO

CIATION,

Appellants.

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

L incoln C. Jenkins, Jr.,

Columbia, S. C.

Robert L. Carter,

o f Counsel.

Supreme Printing Co., In c , 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BEekman 3-2320

Questions Involved

Whether Judge Grimball erred in overruling the

demurrer of the defendants on the grounds that:

(1) the complaint failed to set forth facts sufficient to

constitute a cause of action for the reason that the alleged

libelous statement is stated in the alternative;

(2) it does not appear upon the face of the complaint

that the alleged libelous statement was published of and

concerning the plaintiff;

(3) it does not appear upon the face of the complaint

that the alleged libelous statement is capable of being

construed as libelous;

(4) it does not appear upon the face of the complaint

that the alleged libelous statement was published of and

concerning the plaintiff in his professional capacity as an

attorney at law.

2

BRIEF OF ARGUM ENT

1. The demurrer should have been sustained for

the reason that the alleged libelous statement is stated

in the alternative.

The outstanding authorities on the law of libel and

slander concur in holding that an alleged libelous state

ment in the alternative is not actionable unless both alter

natives are defamatory. Perhaps the leading authority on

libel is Newell. In his 4th edition, section 234, page 273,

he states the rule as follows:

“ Where a charge is made in the alternative, ordinar

ily both alternatives must be defamatory to render

the charge actionable.”

Cases cited in support thereof are Blackwell v. Smith, 8

Mo. App. 43 and Lukehart v. Byerly, 53 Pa. 418. These

cases involve such statements as “ you are either a thief

or you got the book from a thief” (Blackwell v. Smith,

supra), and “ the said Blackwell had ‘ taken apples’ or

had ‘ stolen apples’ or had ‘ taken apples without asking

for them’ ” (Lukehart v. Byerly, supra). Both cases, of

course, hold that the statements made in the alternative

are not actionable.

Other eminent authority on general American law,

Corpus Juris Secundum holds: “ Generally an imputation

in alternative form is actionable only when both alterna

tives are defamatory, and if either alternative statement

is harmless the charge is not actionable.” In Atkinson v.

Hartley, 1 McCord 203, 12 S. C. L. 203 this Court held:

“ To render words actionable they must be spoken affirma

tively and import a direct charge . . . It follows, therefore,

that those that are equivocal and spoken adjectively are

not so.” That case involved equivocal evidence as to

whether the defendant had made a charge against plaintiff

3

which was actionable or had made a charge in somewhat

different terms which would not be actionable. Bull v.

Collins, 54 S. W. 870 (Texas) holds as do the above cases.

The record, on the face of the complaint clearly shows

that the statement does not import a direct charge. The

statement is:

“ ‘ He not only signed after reading the peti

tion, but on one occasion directed others how to

sign them. Either he is double-talking or the officials

who released his statements to the press are word

ing these retroactions to fit the Citizens’ Commit

tees’ ” (E. 3).

It thus says of one Blanding (who is not a party herein)

that he is “ double-talking” and then states in the alter

native that if he is not, certain “ officials” (in which cate

gory plaintiff seeks to include himself) are wording “ these

retroactions (sic) to fit the Citizens’ Committee.” There

fore, the alleged defamatory statement is in the alterna

tive. One alternative is not even alleged to be actionable

by plaintiff. The case falls squarely within the general

American rule that statements in the alternative are not

actionable unless both alternatives are actionable. It is

appellants’ position that neither alternative herein is ac

tionable, but certainly both alternatives can hardly be

actionable as to the plaintiff herein.

2. The demurrer should have been sustained for

the reason that it does not appear upon the face of the

complaint that the alleged statement was published of

and concerning the plaintiff.

The complaint, of course, contains an averment and

certain allegations which purport to identify the plaintiff

as the person concerning whom the allegedly libelous state

ment was made.

4

But a mere conclusion, even if supported by allega

tions which purport to support it, cannot make a case of

actionable wrong where this Court can clearly see on the

complaint’s face that no reasonable man could determine

that the allegedly libelous remarks were made of and

concerning plaintiff. As this Court held in Oliveros v.

Henderson, 116 S. C. 77, 106 S. E. 865:

“ The demurrers admit the facts alleged in the

complaint, but do not admit the inferences drawn

by plaintiffs from such facts, and it is for the Court

to determine as to whether or not such inferences

are justifiable; that is, to determine if the language

used in the publication can fairly and reasonably

be construed to have the meaning attributed to it

by the plaintiff.” (Italics added.)

In Phillips v. Union Indemnity Company, 28 F. 2d 701, it

was held that on demurrer it is for the court to determine

whether the innuendo is fairly warranted by the language

declared in it. See also Stokes v. Great Atlantic and Pacific

Tea Company, 202 S. E. 24. Here that alternative which

supposedly refers to plaintiff is “ or the officials who

released his statements to the press are wording these

retroactions to fit the Citizens’ Committee” (R. 3).

The complaint itself does not allege that plaintiff is an

“ official” of the School Board of School District # 2 or

School District #17. It does not allege that he is an

official of anything. On the contrary, it alleges that his

relation with these School Boards was that of counsel.

“ The relationship of attorney and client is that of prin

cipal and agent or master and servant; that is, apart from

his connection with existing litigation, an attorney is a

mere agent. An attorney is not, however, completely sub

ordinate to his client as the ordinary agent is to his prin

cipal. . . . ” 5 Am. Jur. 286. It would be laboring the

obvious before any Court to elaborate on the proposition

5

that counsel employed by a School Board cannot even

remotely be considered an official of that Board.

Moreover, the allegedly libelous statement speaks in

the plural of “ officials” , a large class of persons, at least

extending to the members of the School Boards mentioned

in the complaint and their executive officers. The com

plaint attempts to fly in the face of the obvious facts ap

pearing upon it by attempting to stretch the word “ offi

cials” to include plaintiff; and by attempting to narrow

a general class of which plaintiff is not a member, down

to a single individual.

If this complaint is permitted to stand then any obvi

ously non-applicable statement can be set before a jury

despite the fact that the statement as it appears in the

complaint flatly contradicts the interpretation placed upon

it by the plaintiff.

3. The demurrer should have been sustained be

cause it does not appear upon the face of the complaint

that the allegedly libelous statement is capable of being

construed as libelous.

Granting arguendo, for the moment, that a case can be

made out for the proposition that (a) a statement in the

alternative where one alternative is not even alleged to be

libelous, can be made actionable and (b) that a statement

made clearly not of and concerning the plaintiff can be

made actionable in the face of the plain unequivocal lan

guage of the statement, appellants submit that the state

ment itself is innocuous.

The alleged libelous statement as it purportedly refers

to plaintiff is that “ the officials who released the statements

to the press are wording these retroactions to fit the Citi

zens’ Committee.” In this age of widely disseminated

news and great public interest in public affairs all parties

6

to issues of public interest seek to win its favor. Press

releases, press conferences, interviews, letters to the edi

tor, have perhaps unfortunately, perhaps fortunately,

found a permanent place in American life. Everyone

realizes perfectly well that statements issued to the press

are made to “ put one’s best foot forward.” The language,

the timing, the balance, are all designed to present a point

of view. To state that anyone who participates in the

wording of a statement which may be released to the press

has slanted it to fit a point of view is to state something

at which no one would be surprised. No one would dream

of alleging that it is libelous to state that James Hagerty,

has worded a statement to suit the Republican Party or

that Paul Butler, the Democratic National Chairman has

worded a statement to suit the Democratic Party. Of

spokesmen on any issue, great or small, national or local,

to state that they have worded statements to suit those

with whom they are associated or with whom they sym

pathize, is to state something entirely natural and accepta

ble. Surely the allegedly libelous statement in this case

states nothing other than what all Americans would accept

today and is not capable of being construed as libelous.

4. The demurrer should have been sustained for

the reason that it does not appear upon the face of the

complaint that the allegedly libelous statement is

capable of being construed as libelous concerning the

plaintiff in his professional capacity as attorney at law.

Quite apart from the fact that the allegedly libelous

statement does not even refer to the plaintiff it clearly

appears that it does not refer to him or, indeed, to anyone

else in the capacity of attorney at law. This statement

merely refers to someone who worded a statement which

was released to the press. If anything, it may taken to

refer to a public relations or public information official or

7

to some kind of school board functionary. It is not the

duty or employment of an attorney at law to release state

ments, and it cannot be considered harmful for an attorney

(surely one never identified as such) to receive comment

on something allegedly done not in the capacity of attorney.

Conclusion

Here we have a statement made in the alternative with

out it even being alleged (it could not be) that both alterna

tives are libelous. It nowhere appears on the face of the

complaint that the alleged libelous statement was published

of and concerning the plaintiff; indeed the plain language

of the complaint indicates it was made concerning a num

ber of persons with characteristics plaintiff clearly does

not possess. The allegedly libelous alternative is on its

fact innocuous and harmless. It was not made concerning

anyone in the capacity of attorney at law.

The complaint is composed of hypothesis upon hypothe

sis, each without substance. Such a tenuous concatenation

of assumptions does not merit the sustaining of the com

plaint or submission of the cause to a jury.

Wherefore appellants respectively submit that the

demurrer should have been sustained.

Respectfully submitted,

R obert L. Carter,

Of Counsel.

L incoln Jenkins,

Columbia, S. C.