Harrison v. NAACP Motion to Affirm

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1957 - January 1, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Harrison v. NAACP Motion to Affirm, 1957. ca426689-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f616e319-123d-4001-9a59-7c263d22fcba/harrison-v-naacp-motion-to-affirm. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

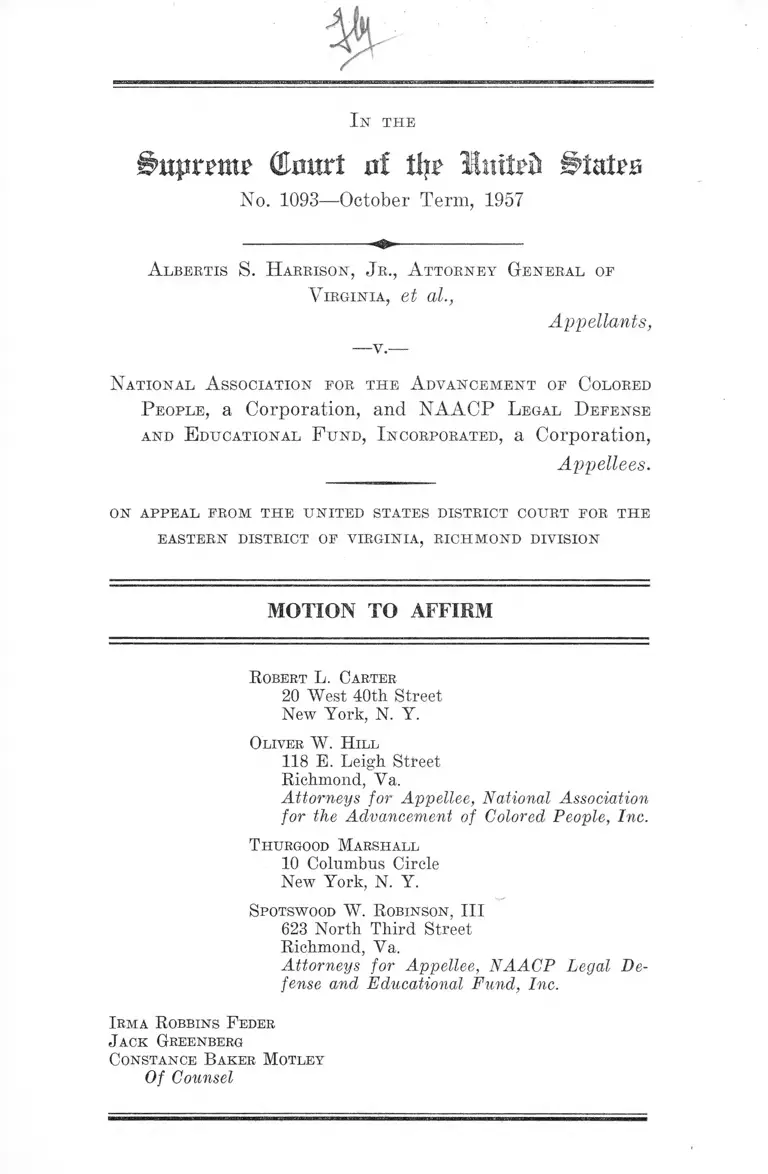

I n t h e

Bnpmm (Emirt of the Hutted Utatpa

No. 1093—October Term, 1957

A lb er tis S. H a rrison , J r., A tto rn ey G en er a l of

V ir g in ia , et al.,

Appellants,

N a tio n a l A ssociation for t h e A d v a n cem en t of C olored

.Pe o pl e , a Corporation, and NAACP L egal D e f e n s e

and E d u cational F u n d , I ncorporated , a Corporation,

Appellees.

on a ppea l from t h e u n it e d states d istr ic t court for t h e

E A ST E R N D IST R IC T OF V IR G IN IA , R IC H M O N D D IV ISIO N

MOTION TO AFFIRM

R obert Ij . Carter

20 West 40th Street

New York, N. Y.

Oliver W. H ill

118 E. Leigh Street

Richmond, Va.

Attorneys for Appellee, National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People, Inc.

T hurgood Marshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y.

Spotswood W. R obinson, III

623 North Third Street

Richmond, Va.

Attorneys for Appellee, NAACP Legal De

fense and Educational Fund, Inc.

I rma R obbins F eder

J ack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

Of Counsel

INDEX TO MOTION

Opinion Below................................. ..................... .........

Jurisdiction ................ ........... .......................... ..............

Questions Presented ....... .............. ......................... ......

Statement of the Case................. ..................... ............

Statement of the Facts .................. ...............................

R eason fo e G r a n t in g t h e M o t io n : T h e

Q u e st io n s P r esen ted A re U n su b st a n t ia l

I. The Court below was unquestionably correct

in holding Chapters 31, 32, and 35 unconsti

tutional as they clearly violate the Fourteenth

Amendment and Article III, Section 2 of the

Constitution of the United S tates_______

II. The Court below did not abuse its equitable

discretion in entertaining the instant suits for

declaratory judgments and injunctive relief

or in restraining the enforcement of the

criminal statutes involved ........... ................

III. The Court below did not abuse its equitable

discretion in enjoining the enforcement of the

state statutes involved although they had not

been authoritatively construed by the state

courts.................... .................... ...... ...............

C o n c lu sio n

T able of C ases

page

Adkins v. School Board of City of Newport News, 148

F. Supp. 430 (E. D. Va. 1957), aff’d 246 F. 2d 325

(4th Cir. 1957), cert. den. 355 U. S. 869 ______.___17

Aiken v. Insull, 122 F. 2d 746, 749 (7th Cir. 1941),

cert. den. 315 U. S. 806 ............................................. 9

Alabama Public Service Commission v. Southern Ry.,

341 U. S. 341....................... .................... .................... 16

Albertson v. Millard, 345 U. S. 242 _____ ___________ 16

American Federation of Labor v. Watson, 327 U. S.

582 ......... ............... ....................................................12,16

Barbier v. Connally, 113 U. S. 27 ................... 8

Bartels v. Iowa, 262 U. S. 404 ___ 10

Beal v. Missouri Pacific R. Corp., 312 U. S. 45 .......... 13

Bryan v. Austin, 148 F. Supp. 563 (E. D. S. C. 1957),

vacated as moot 354 U. S. 933 .......... 15

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 6 0 ...... 6

Burford v. Sun Oil Co., 319 U. S. 315 __ ______ ____ 16

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 138 F. Supp. 337

(E. D. La. 1956), aff’d 242 F. 2d 156 (5th Cir. 1957)

16-17

Carter v. Carter Coal Co., 298 U. S. 238 ____________ 13

Chicago v. Fieldcrest Dairies, 316 U. S. 168 16

City of Birmingham v. Monk, 185 F. 2d 859 (5th Cir.

1950), cert. den. 341 U. S. 940 ...... ............................ 6

Consumers’ Gas Co. v. Quimby, 137 F. 882 (7th Cir.

1905), cert. den. 198 U. S. 585 .................................... 9

Cotting v. Kansas City Stock Yards Co., 183 U. S. 79 .... 11

Crandall v. Nevada, 73 U. S. (6 Wall.) 35....... ........... 8

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S. D. Ala. 1949),

aff’d 336 U. S. 933 ..................................................... 16

ii

Doud v. Hodge, 350 U. S. 485 ....................................... 15

Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157........... .......... .......... 12

Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U. S. 365 ............ ..... 12

Ex parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283 ........................ ........... . 6

Ex parte Young, 209 U. S. 123................... ................... 13

Fenner v. Boykin, 271 U. S. 240 ................... ...... ......... 12

First Congregational Church v. Evangelical & R. Ch.,

160 F. Supp. 651 (S. D. N. Y. 1958) ________ ___ 9

Follet v. McCormick, 321 U. S. 573 ........... ............ ........ 8

Gibbs v. Buck, 307 U. S. 66___ _____________ ____ _ 13

Government & Civic Employees Organizing Committee

v. Windsor, 353 U. S. 364 .................................. ......15,16

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 287 U. S. 233 .............. 7

Gunnels v. Atlanta Bar Ass’n, 191 Ga. 366, 12 S. E.

2d 602 .................................... ..... ............. .......... ........ 9

In re Ades, 6 F. Supp. 467 (D. Md. 1934) .............. ...... 9

Irving v. Neal, 209 F. 471 (S. I). N. Y. 1913) ................. 9

Jahn v. Champagne Co., 157 F. 407 (W. D. Wise. 1908),

aiF.I 168 F. 510 (7th Cir. 1909) ......................... 9

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341

U. S. 123 ............................... ............................. ........ 8

Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 353 U. S. 252 .... 10

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214..... ........... - 6

Lonesome v. Maxwell, 220 F. 2d 386 (4th Cir. 1955),

aff’d 350 U. S. 877 ..................................... .. ............ - 6

Ludley v. Board of Supervisors, 150 F. Supp. 900

(E. D. La. 1957) .................................. ....................... 17

McCloskey v. Tobin, 252 U. S. 107.......................... -.... 10

IV

PAGE

Meredith v. Winter Haven, 320 U. S. 228 ..................... 15

Mexican Nat. Coal, Timber & Iron Co. v. Frank, 154

F. 217 (C. C. S. D. Tex. 1907) ........ ........................... 9

Meyers v. Nebraska, 262 U. S. 390 .................. .......... 10

Missouri P. R. Co. v. Tucker, 230 U. S. 340 ...... .......... 13

Morey v. Bond, 354 U. S. 457 ........................... ..... ...... 11

Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 .... 6

Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U. S. 105.......... .............. 8

National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People v. Alabama,-----U. S .------ , 26 L. W. 4489,

decided June 30, 1958 .................... ............................. 5, 7

Oklahoma Operating Co. v. Love, 252 U. S. 331 .....— 13

Pennsylvania v. Williams, 294 U. S. 176 ...... .............. . 16

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510 ................ ..10,12

Propper v. Clark, 337 U. S. 472 .................................. 15

Hhiblic Utilities Co. v. United Fuel Gas Co., 317 U. S.

456 ....................... ...................................................... 13

Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman Co., 312

U. S. 496 ..... ................... .......... ................................. 16

Rice v. Elmore, 165 F. 2d 387 (4th Cir. 1947), cert. den.

333 U. S. 875 ....................... .................... ..... ............. 16

Rinderknecht v. Toledo Association of Credit Men, 13

F. Supp. 555 (N. D. Ohio 1936) ............. ............. ..... 9

Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U. S. 232 .... 10

Slaughter House Cases, 83 U. S. (16 Wall.) 36 .......... 8

Slochower v. Board of Education, 350 U. S. 551......... . 10

Spector Motor Co. v. McLaughlin, 323 U. S. 101 16

Speiser v. Randall,-----U. S. ------, 26 L. W. 4479, de

cided June 30, 1958 ------------------- ............................ 7

Spielman Motor Sales Co. v. Dodge, 295 U. S. 89.......... 12

Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234 ................... . 5, 8

V

PA G E

Terrace v. Thompson, 263 U. S. 197................. ..........-13,14

Terral v. Burke Construction Co., 257 U. S. 529 ........ - 8

Thallheimer v. Brinckerhoff, 3 Cow. 623, 15 Am. Dec.

308 (N. Y. Court of Errors 1824) ................... ......... 10

Toomer v. Witsell, 334 U. S. 385 .................................. 15

Truas v. Corrigan, 257 U. S. 312 .................................... 8

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33 ............................. -............ 12

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U. S. 75 ........... 12

United States v. CIO, 335 U. S. 106..... .....— .............. - 8

United States v. Rumley, 354 U. S. 41........ .................. 5, 8

Wadley S. R. Co. v. Georgia, 235 U. S. 651 ................. 13

Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178 ..................... 5, 8

^Watson v. Buck, 313 U. S. 387 ............... ....................... 12

Wheeler v. Denver, 229 U. S. 342 ......... ~.........—- ........ 9

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183 ..... ........... .......5, 8,10

-Yakus v. United States, 321 U. S. 414 ........... ....... 13

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 ..... ............ ...... .... 11

Isr t h e

S u p r e m e (f lm ir t o f tbi* M uitrJi S t a t e s

No. 1093—October Term, 1957

A lb er tis S. H a rrison , J r., A tto rn ey G en er a l oe

V ir g in ia , et al.,

Appellants,

N atio n a l A ssociation for t h e A d v a n cem en t of C olored

P e o pl e , a Corporation, and NAACP L egal D e f e n s e

and E ducational F u n d , I ncorporated , a Corporation,

Appellees.

ON A P P E A L FR O M T H E U N IT E D STA TES D IS T R IC T CO U RT FO R T H E

E A ST E R N D IST R IC T OF V IR G IN IA , R IC H M O N D D IV ISIO N

MOTION TO AFFIRM

Appellees in the above-entitled case move to affirm on

the ground that the questions presented are so unsub

stantial as not to need further argument.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the three-judge United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond

Division, is reported at 159 F. Supp. 503 (1958), sub nom.

National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People v. Patty, and is printed in Appellants’ Appendix

in their Statement of Jurisdiction at pages 1-95.1

1 Appellants’ Appendix in their Statement of Jurisdiction is

hereafter referred to as J.S., App.

2

Jurisdiction

Appellees adopt the section on “The Jurisdiction of the

Court” in appellants’ Statement of Jurisdiction at page 1.

The three statutes involved are printed verbatim at J.S.,

App. page 95.

Questions Presented

Appellees adopt the “Questions” as presented by appel

lants at page 3 of their Statement of Jurisdiction.

Statement of the Case

Appellees, the National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People (the Association) and the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund (the Fund) filed separate

complaints in the district court against the Attorney Gen

eral of Virginia and five Commonwealth’s Attorneys who

are charged by law with the enforcement of one or more

of the various provisions of certain legislation enacted by

the General Assembly of Virginia at the 1956 Extra Ses

sion. Both complaints sought judgment declaring the

invalidity of Chapters 31, 32, 33, 35 and 36 of the Act of

said Extra Session of the General Assembly on the ground

that they abridged rights secured under the equal protec

tion and due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, the First Amendment and the Commerce Clause of

the Federal Constitution. The complaints also sought in

junctions restraining defendants from enforcing these

statutes.

On April 30, 1958 the court below entered its judgment

declaring Chapters 31, 32 and 35 unconstitutional and en

joined their enforcement on the ground that they violated

the requirements of equal protection and due process.

3

Chapters 33 and 36 were retained on the docket for a rea

sonable time to allow plaintiffs an opportunity to proceed

in the state courts to secure an interpretation of these two

statutes.

Statement of the Facts

Appellees disagree with the facts recited in appellants’

Statement of Jurisdiction and adopt the statement of facts

set forth in the opinion of the court below at J.S., App.

pages 1-10.

“ T he S ta tu tes”

The three statutes involved in this appeal may be sum

marized as follows: Chapter 31 prohibits a corporation

from soliciting or expending funds to commence or con

tinue proceedings to which it is not a party and in which

it has not a pecuniary right or liability unless it annually

files with the State Corporation Commission the names

and addresses of its members; also, detailed information

must be filed with respect to its income, expenditures and

activities, including a certified statement showing the

source of every contribution or other items of income dur

ing the preceding calendar year plus, if requested, the

name and address of every contributor. Noncompliance

subjects a corporation to a $10,000 fine, for which each

director, officer, or other person responsible for the man

agement or control of appellee’s affairs may be held per

sonally liable; to revocation of its authority to do business

in Virginia; and to a court order enjoining its activities.

Moreover, any individual acting as an agent or employee

of the corporation is deemed guilty of a misdemeanor and

fined $500 or sentenced to 12 months imprisonment or both.

Chapter 32 requires annual registration of any corpo

ration which has as one of its principal functions or activi

4

ties the advocating of racial integration or which raises

or expends funds for the employment of counsel or pay

ments of costs in connection with litigation in Virginia

on behalf of any race or color. In order to register, each

such corporation (save those which conduct their activi

ties solely through the mails or other media for interstate

communications and those which engage in a political

campaign or political activities connected with it) must

supply for public inspection detailed data itemizing, inter

alia, the names and addresses of its members, the source

of each contribution or other income received during the

preceding calendar year, and the object of each expendi

ture for the same period. Noncompliance with these

requirements subjects corporations and individuals to the

penalties and liabilities imposed by Chapter 31; in addi

tion, this statute provides that each day’s failure to register

is a separate offense punishable as such.

Chapter 35 creates and punishes the offense of barratry.

Barratry is defined as instigating litigation, i.e., bringing

about a suit at law or in equity in which all or part of the

expenses of the litigation are defrayed by a “nonparty,”

i.e., a person or corporation which has no direct interest

(personal right or pecuniary right or liability) in the sub

ject matter of the litigation, and occupies no position of

trust in relation to the plaintiff, and is not duly consti

tuted as a legal aid society approved by the Virginia State

Bar. The Act also provides that it does not apply to con

tingent fee contracts, and excepts from its provisions in

effect all suits challenging state action save those involving

the civil or constitutional rights of Negroes. The punish

ment provided for barratry is $500 fine or a year’s im

prisonment, or both; if the barrator is a corporation, a

$10,000 fine and revocation of its authorization to do busi

ness in Virginia as a foreign corporation applies.

5

REASON FOR GRANTING THE MOTION: THE

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ARE UNSUBSTANTIAL

I.

The Court below was unquestionably correct in hold

ing Chapters 31, 32, and 35 unconstitutional as they

clearly violate the Fourteenth Amendment and Article

III, Section 2 of the Constitution of the United States.

It cannot be gainsaid that in advocating and seeking the

betterment of the Negro’s status in America, appellees’

members and contributors are invoking their constitution

ally protected rights of free speech and free association

guaranteed under the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People v. Alabama,----- U. 8 .------ , 26 L. W. 4489,

decided June 30, 1958. Nor are appellees’ activities outside

the area of state restriction or prohibition absent some

overriding valid interest of the State. National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People v. Alabama, supra;

See Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234, 265, 266;

Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178, 250-251; United

States v. Rumley, 354 U. S. 41; Wieman v. Updegraff, 344

U. S. 183,196.

Appellants’ justification for requiring a list of appellees’

members and contributors under Chapter 32 is as follows:

(1) to help in law enforcement (Tr. 422, 426, 446, 468) ;

(2) to help in the selection of deputies, and prevent deputiz

ing a person participating actively in an organization

agitating violence (Tr. 431, 452-453, 469, 475); (3) to

identify certain known troublemakers and their associates

(Tr. 468, 502) ; (4) to keep a check on agitators from outside

the community (Tr. 452, 468, 474); (5) to possibly deter

agitators from coming in the community (Tr. 469); (6) to

6

curb race tension that might ultimately lead to violence

(Tr. 502); (7) to deter the breach of public or private

rights (Tr. 502) ; (8) to make the names a matter of public

record so that direct responsibility could be placed on the

organizations and the individuals engaging in any of the

activities they undertook to do (Tr. 521).

Chapter 31’s demand for a list is justified as an aid in

detecting those persons who are engaging in barratry,

maintenance, unauthorized practice of law, and related

offenses (Tr. 558-559).

Desirable as it may be for the state to be able to detect

law violators, to suppress racial violence and tensions, and

to avoid racial antagonisms, such ends may not be achieved

by denying rights secured by the Constitution. Morgan v.

Commonwealth of Virginia, 328 U. S. 373, 380; Ex parte

Endo, 323 U. S. 283, 302; see Korematsu v. United States,

323 U. S. 214, 216; Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 81;

Lonesome v. Maxwell, 220 F. 2d 386 (4th Cir. 1955) aff’d,

350 U. S. 877; City of Birmingham v. Monk, 185 F. 2d 859

(5th Cir. 1950), cert. den. 341 U. S. 940.

Also, the record discloses an uncontroverted showing

that persons identified with or dedicated to appellees’

causes have been subjected to harassment, intimidation,

loss of employment, and other manifestations of public

hostility (Tr. 171, 173, 176-8, 184-7, 193-201, 205, 209-212,

218-225, 229-232). Under circumstances similar to these,

this Court upheld the right to preserve from disclosure

the names and addresses of persons dedicated to appellees’

aims:

We think that the production order, in the respects

here drawn in question, must be regarded as entailing

the likelihood of a substantial restraint upon the exer

cise by petitioner’s members of their right to freedom

of association. Petitioner has made an uncontroverted

7

showing that on past occasions revelation of the iden

tity of its rank-and-file members has exposed these

members to economic reprisal, loss of employment,

threat of physical coercion, and other manifestations

of physical coercion, and other manifestations of public

hostility. Under these circumstances we think it appar

ent that compelled disclosure of petitioner’s Alabama

membership is likely to affect adversely the ability

of petitioner and its members to pursue their collective

effort to foster beliefs which they admittedly have the

right to advocate, in that it may induce members to

withdraw from the Association and dissuade others

from joining it because of fear of exposure of their

beliefs shown through their associations and of the con

sequences of this exposure. National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People v. Alabama, supra,

at 4493.

Thus, the court below, appellees submit, was eminently

correct in striking down legislation which would produce

the same reprisals and impinge the same First Amendment

rights.

Moreover, the list of exceptions set forth in §9 of Chapter

32 excludes from the operation of the statute every con

ceivable group but those (like appellees) involved in the

field of racial discrimination. To make the statute appli

cable only to persons who engage in advocating racial

integration is in effect to penalize them for such advocacy

in violation of First Amendment protections. See Speiser

v. Randall,----- U. S. ------ , 26 L. W. 4479, 4480, decided

June 30, 1958.

There can be no question that corporate businesses may

be formed not only for the purpose of engaging in free

speech, Grosjean v. American Press Co., 287 U. S. 233, but

also for the purpose of aiding others through the extension

8

of charity, Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. Mc

Grath, 341 U. S. 123.

The crime of barratry is so defined in Chapter 35, how

ever, that appellees’ activities, which are essential to the

exercise of their members’ and contributors’ basic First

Amendment freedoms, are thereby made criminal. When

appellees take concerted action in the form of sponsorship

of litigation by furnishing counsel and sharing expenses,

these organizations are exercising the rights of their mem

bers and contributors to freedom of expression on public

issues and the right to pool their resources for their

mutual benefit. Cf. Sweezy v. New Hampshire, supra; see

Watkins v. United States, supra at pp. 250-251; Wieman v.

Updegraff, supra; United States v. Rumley, supra, at 46;

Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U. S. 105; Foiled v. McCor

mick, 321 U. S. 573; cf. United States v. C. I. 0., 335 U. S.

106, 143-144 (concurring opinion).

In Virginia, since both the legislative and executive branch

of the government oppose elimination of state enforced

racial restrictions, the only avenue of redress for one seek

ing to remove such restrictions is access to the courts.

The primary right of Virginia residents to resort to the

federal courts for relief from state imposed racial segre

gation stems from the Constitution itself. See Article III,

Section 2, Clause 1. The right of persons to resort to

federal courts for protection against unlawful state action

has been recognized and applied by this Court in a long line

of cases, including Terral v. Burke Construction Co., 257

U. S. 529; Truax v, Corrigan, 257 U. S. 312, 334; Barbier

v. Connally, 113 U. S. 27, 31; Slaughter House Cases, 83

U. S. (16 Wall.) 36; and Crandall v. Nevada, 73 U. S. (6

Wall.) 35, 44. Moreover, this right was specifically and ex

pressly secured by the Civil Eights Acts2 which give a right

2E.g., Title 42, United States Code, §§1971, 1981, 1982, 1983.

9

of action at law or in equity to every person deprived of a

Constitutional right by one acting under color of state law,

and confer jurisdiction upon the federal district courts to

hear and determine such cases. Title 28 U. S. C. §1343 (3).

Implied in this right of access to the federal courts is the

right to assist, and the right to accept assistance, when

necessary to adequately present the issues to these courts.

The question of state imposed racial segregation is of great

public interest, and litigation attacking such discrimination

is too costly for the average individual litigant to bear. By

the provisions of Chapter 35, Negroes are denied the right

to obtain financial or legal assistance in this kind of litiga

tion. To leave the federal courts open only to litigants able

to finance such cases is to effectively close the door to the

great majority of aggrieved Negro citizens.

It has long been recognized that charitable or nonprofit

organizations may proffer legal assistance to persons un

able to bear the costs of litigation or where important public

issues are involved. See In re Ades, 6 F. Supp. 467, 478 (D.

Md. 1934); Gunnels v. Atlanta Bar Assn., 191 Ga. 366, 12

S. E. 2d 602; Irving v. Neal, 209 F. 471, 475 (S. D. N. Y.

1913); Wheeler v. Denver, 229 U. S. 342, 351. See also

Canon 35, Canons of Professional Ethics of the Ameri

can Bar Association; Opinion of A. B. A. Committee on

Professional Ethics and Grievances, Opinion 148 (1935);

First Congregational Church v. Evangelical & R. Ch., 160

F. Supp. 651 (S. D. N. Y. 1958); Aiken v. Insull, 122 F. 2d

746, 749 (7th Cir. 1941), cert. den. 315 U. S. 806; Rinder-

knecht v. Toledo Association of Credit Men, 13 F. Supp. 555,

557 (N. D. Ohio 1936); John v. Champagne Co., 157 F. 407,

418 (W. D. Wise. 1908) aff’d 168 F. 510 (7th Cir. 1909);

Mexican Nat. Coal, Timber & Iron Co. v. Frank, 154 F. 217,

224 (C. C. S. D. Tex. 1907); Consumers’ Gas Co. v. Quinby,

137 F. 882, 893 (7th Cir. 1905), cert. den. 198 IJ. S. 585;

10

Thallhimer v. Brinckerhoff, 3 Cow. 623, 15 Am. Dec. 308

(N. Y. Court of Errors, 1824).3 By failing to recognize

this well settled rule, Chapter 35 establishes prerequisites

and requirements for the conduct of litigation which are

contrary to one of the basic tenets upon which our legal

system is predicated. The action of the state, therefore,

in denying appellees the right to pursue their normal

and lawful activities is patently arbitrary and dis

criminatory in contravention of the due process clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment. See Schware v. Board of Bar

Examiners, 353 IT. S. 232; Konigsberg v. State Bar of Cali

fornia, 353 U. S. 252; Sloehower v. Board of Education,

350 U. S. 551; Wieman of Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183; Pierce

v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510.

Attorneys who cooperate with appellees are engaged

in the lawful and legitimate pursuit of their professions.

Cf. Meyers v. Nebraska, 262 U. S. 390; Bartels v. Iowa,

262 U. S. 404; Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, supra;

Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, supra. In the

Schware case, supra, this Court said at pages 238-239:

A state cannot exclude a person from the practice of

law or from any other occupation in a manner or for

reasons that contravene the Due Process and Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

A fortiori, a state cannot impose restrictions on the prac

tice of law or prohibit practice in certain cases in a manner

or for reasons inconsistent with the guarantees of due

process and equal protection.

Furthermore, Chapter 35 exempts from its operation a

large number of groups which similarly engage in collec

3 Of course these principles do not apply where a sharing of

profit is involved. See McCloskey v. Tobin, 252 U. S. 107.

11

tive activities to secure rights through litigation and whose

activities in this regard do not differ from the activities

of appellees. The effect of the discrimination is to designate

as criminal the activities of these organizations in sponsor

ing litigation while permitting the identical activity by

others, thus denying to the appellees the equal protection

of the laws. Cotting v. Kansas City Stock Yards Co., 183

U. S. 79. Cf. Morey v. Bond, 354 IT. S. 457; Yick Wo v.

Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356.

For these reasons it is clear that Chapters 31, 32 and 35

violate the equal protection and due process clauses of the

14th Amendment as well as Article III, Section 2 to the

federal Constitution.

II.

The Court below did not abuse its equitable discretion

in entertaining the instant suits for declaratory judg

ments and injunctive relief or in restraining the enforce

ment of the criminal statutes involved.

Appellees, their members, contributors, employees, and

lawyers to whom they may contribute money toward defray

ing fees and expenses incident to litigation involving the

legality of racial discrimination clearly violate Chapters

31, 32, and 35 in the course of their routine day to day

activities. These statutes prohibit the continuance of ap

pellees’ business by (1) declaring illegal “non-party” aid

to litigants seeking to secure constitutional rights against

racial discrimination, and (2) requiring disclosure of mem

bers’ and contributors’ names and addresses as a pre

requisite to any and all activities concerning racial integra

tion, including solicitation of funds from the public to defray

the costs of litigation involving the legality of racial dis

crimination. Appellees of necessity rely upon public sup

port and contributions for their continued existence.

12

Not only do these statutes place a “cloud of illegality”

over all of appellees’ activities, but also (in view of the

present climate of opinion in Virginia) compliance would

expose appellees’ members and contributors to harassment,

abuse and economic reprisals (J.S., App. pp. 20-22). Thus,

even in the absence of enforcement of these “emergency”

statutes by state officials, the statutes visit great and im

mediate danger of irreparable loss upon appellees by de

priving them of public support, contributions and members,

seriously impairing the organizations and threatening their

destruction. Cf. Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510;

Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U. S. 365, 386.

It is therefore clear that the complaints herein requesting

declaratory judgments on constitutional questions involve

“ ‘concrete legal issues, presented in actual cases, not

abstractions,’ . . . [where complainants] require[d] the

use of . . . judicial authority for their protection against

actual interference.” United Public Workers v. Mitchell,

330 U. S. 75, 89, 90. Moreover, injunctive relief restraining

the enforcement of the criminal statutes herein was in

dicated and properly granted in view of the “ ‘exceptional

circumstances’ and ‘great and immediate’ danger of ir

reparable loss” as alleged in the complaints and shown

at the hearing. See Watson v. Block, 313 U. S. 387, 401;

see also American Federation of Labor v. Watson, 327

U. S. 582, 593, 595; Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157, 164;

Spiehnan Motor Sales Co. v. Dodge, 295 U. S. 89, 95;

Fenner v. Boykin, 271 U. S. 240, 243; Truax v. Raich, 239

U. S. 33, 37-38.

“Exceptional circumstances” are present in addition to

those previously discussed. First, since the statutes cover

numerous activities and classifications of persons, a multi

plicity of suits would be required to determine their con

13

stitutionality if the complaints in the case at bar had been

dismissed. See Beal v. Missouri Pacific R. Corp., 312 U. S.

45, 49. Secondly, members and contributors could not liti

gate the validity of the registration requirements without

revealing their identity. Thirdly, the heavy penalties pro

vided by the statutes inhibit access to the courts for ju

dicial determination of the constitutionality of the statutes

by placing such a high price on inviting or awaiting actual

prosecution. See Ex parte Young, 209 U. S. 123, 147-148;

see also Missouri P. R. Co. v. Tucker, 230 U. S. 340, 347;

Wadley S. R. Co. v. Georgia, 235 U. S. 651, 661-666; Okla

homa Operating Co. v. Love, 252 U. S. 331, 336-338; Carter

v. Carter Coal Co., 298 U. S. 238, 287-288; Terrace v.

Thompson, 263 U. S. 197, 216; Gibbs v. Buck, 307 U. S.

66, 76-78; Public Utilities Co. v. United Fuel Gas Co., 317

U. S. 456, 468-469; Yakus v. United States, 321 U. S. 414,

437-438. Indeed the whole panoply of state government is

arrayed against appellees and their members and contribu

tors (J.S., App. pp. 12-20).

The court below, therefore, was eminently correct in its

disposition of appellants’ argument in the following man

ner :

The defendants also invoke the familiar rule that

ordinarily a court of equity will not restrain a criminal

prosecution based on a state statute, even if the con

stitutionality of the statute is involved, since this

question can be raised and settled in the criminal case

with review by the higher court as well as in a suit

for an injunction, Douglas v. City of Jeannette (Penn

sylvania), 319 U. S. 157, 163, 164, 63 S. Ct. 877, 87

L. Ed. 1324, and this is especially true where the only

threatened action is a single prosecution of an alleged

violation of state law. However, it is also well recog

nized that a criminal prosecution may be enjoined

u

under exceptional circumstances where there is a clear

showing of danger of immediate irreparable injury,

Spielman Motor Sales Co. v. Dodge, 295 L. S. 89, 95,

55 S. Ct. 678, 79 L. Ed. 1322, Beal v. Missouri Pacific

B. Corp., 312 U. S. 45, 49, 61 S. Ct. 418, 85 L. Ed.

577. It is obvious that the present case falls in the

latter category. The penalties prescribed by the

statutes are heavy and they are applicable not only

to the corporation but to every person responsible

for the management of its affairs, and under Chapter

32 of the statutes each day’s failure to register and

file the required information constitutes a separate

punishable offense. The deterrent effect of the statutes

upon the acquisition of members, and upon the activities

of the lawyers of the plaintiffs under the threat of

disciplinary action has already been noted, and the

danger of immediate and persistent efforts on the part

of the state authorities to interfere with the activities

of the plaintiffs has been made manifest by the re

peated public statements. The facts of the cases

abundantly justify the exercise of the equitable powers

of the court. Ex parte Young, 209 U. S. 123, 147, 28

S. Ct. 441, 52 L. Ed. 714; Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S.

33, 36 S. Ct. 7, 60 L. Ed. 131; Western Union Telegraph

Co. v. Andrews, 216 U. S. 165, 30 S. Ct. 286, 54 L. Ed.

430; Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U. S. 378, 53 S. Ct,

190, 77 L. Ed. 375 (J.S., App. pp. 31-32).

It is submitted that there is no merit in appellants’ con

tentions and that the facts and applicable law in the in

stant cases amply warranted the district court’s granting

the injunctive relief requested. Terrace v. Thompson,

263 U. S. 197, 214.

15

III.

Tlie Court below did not abuse its equitable discretion

in enjoining the enforcement of the state statutes in

volved although they had not been authoritatively con

strued by the state courts.

The District Court was plainly right in deciding the

constitutional issues presented by Chapters 31, 32, and 35

without previous construction of these statutes by the state

courts.

This appeal does not derive substance from the doctrine

of abstention, recently restated in Government and Civic

Employees Organizing Committee v. Windsor, 353 U. S.

364, 366, that:

In an action brought to restrain the enforcement of

a state statute on constitutional grounds, the federal

court should retain jurisdiction until a definitive de

termination of local law questions is obtained from the

local courts.

This doctrine is a principle of judicial self-limitation

rather than a rule enervating jurisdiction. Doud v. Hodge,

350 U. S. 485. As such, its application is confined to the

situations justifying its existence. See Propper v. Clark,

337 U. S. 472; Meredith v. Winter Haven, 320 U. S. 228.

And it has no application where, as here, “there is neither

need for interpretation of the statutes nor any other special

circumstance requiring the federal court to stay action

pending proceedings in State courts.” Toomer v. Witsell,

334 U. S. 385, 392 note. See also Bryan v. Austin, 148 F.

Supp. 563, 567-568 (E. D. S. C. 1957, dissenting opinion),

vacated as moot 354 U. S. 933.

This case does not present any “special circumstance”

warranting state court proceedings within the abstention

16

rationale as applied by the cases from which it developed.

Unlike Burford v. Sun Oil Co., 319 U. S. 315, and Pennsyl

vania v. Williams, 294 U. S. 176, the District Court was not

called upon to address itself to “a specialized aspect of a

complicated system of local law outside the normal compe

tence of a federal court,” Alabama Public Service Commis

sion v. Southern Ry., 341 U. S. 341, 360 (concurring

opinion), but rather to an issue which by Congressional

enactments the district courts are peculiarly endowed to

entertain. 28 U. S. C. §1343. It is not a case involving any

special application of local law to be preliminarily resolved

before the Federal constitutional questions are reached.

Cf. American Federation of Labor v. Watson, 327 U. S.

582; Spector Motor Co. v. McLaughlin, 323 U. S. 101; Rail

road Commission of Texas v. Pullman Co., 312 U. S. 496.

Consideration of the statutes here involved did not in any

way necessitate “a tentative answer which may be displaced

tomorrow by a state adjudication.” Railroad Commission

of Texas v. Pullman Co., supra, 312 U. S. at 500.

Nor is this a case where a constitutional adjudication

can be avoided by a definitive construction of the statutes

involved. Cf. Albertson v. Millard, 345 U. S. 242; Chicago

v. Fieldcrest Dairies, 316 U. S. 168; Government and Civic

Employees v. Windsor, supra; Spector Motor Co. v. Mc

Laughlin, supra. Their language occasions no uncertainty

as to what they undertake to prohibit or as to whom their

prohibitions are directed, and their unconstitutional pur

pose is unequivocally established by their legislative his

tory and effect recited in the majority opinion below.4

4 Although inquiry into the motivation of legislators is pro

hibited, the intent or purpose of the legislation (as well as its

effects) is relevant in determining constitutionality. Rice v.

Elmore, 165 F. 2d 387, 388-389 (4th Cir. 1947), cert. den. 333 U. S.

875; Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872, 878 et seq. (S. D. Ala.

1949), aff’d 336 U. S. 933; see also Bush v. Orleans Parish School

17

(J.S., App. pp. 12-22.) The District Court was not left

in doubt as to the statutes’ reach and impact in respect to

their application to these appellees. Appellants have

not been able to support any reasonable interpretation of

the statutes that could render them valid, and it is incon

ceivable that a state court could so construe them as to

avoid their legal infirmities. In sum, the District Court

was not presented with an alternative to adjudication of the

constitutional issues thus developed. As Judge Soper

stated:

We are advised that Virginia is not alone in enacting

legislation seriously impeding the activities of the

plaintiff corporations through the passage of similar

laws. (43 Va. L. Rev. 1241.) As heretofore noted, the

problem for determination is essentially a federal

question with no peculiarities of local law. Where the

statute is free from ambiguity and their remains no

reasonable interpretation which will render it consti

tutional there are compelling reasons to bring about

expeditious and final ascertainment of the constitution

ality of these statutes to the end that the multiplicity

of similar actions may, if possible, be avoided. (J.S.,

App. p. 36.)

Appellees submit this conclusion is a wise exercise of

judicial administration,5 and that no other course was

open.

Board, 138 P. Supp. 337, 341 (E. D. La. 1956), aff’d 242 F. 2d

156 (5th Cir. 1957) ; Ludley v. Board of Supervisors, 150 F. Supp.

900, 902-903 (E. D. La. 1957) ; Adkins v. School Board of City of

Newport News, 148 F. Supp. 430, 433-439 (E. D. Va. 1957), aff’d

246 F. 2d 325 (4th Cir. 1957), cert. den. 355 U. S. 869.

6 The care with which the District Court treated the abstention

rule under consideration is evidence of the fact that it declined

to pass upon the constitutionality of the 2 other statutes attacked

in the Complaints in this case.

18

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the questions presented by

appellants are clearly unsubstantial and this motion to

affirm should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

R obert L. C arter

20 West 40th Street

New York, N. Y.

O liv er W. H il l

118 E. Leigh Street

Richmond, Va.

Attorneys for Appellee, National

Association for the Advancement

of Colored People, Inc.

T hurgood M arshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y.

S potswood W, R o b in so n , III

623 North Third Street

Richmond, Va.

Attorneys for Appellee

NAACP Legal Defense and

Education Fund, Inc.

I rma R obbins F eder

J ack Gr een berg

C o n sta n ce B a ker M otley

Of Counsel

38