Giarratano v. Procunier Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

April 10, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Giarratano v. Procunier Brief for Appellant, 1989. b9550e59-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f61fd22b-6c6d-4c6f-80d3-99448566b957/giarratano-v-procunier-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

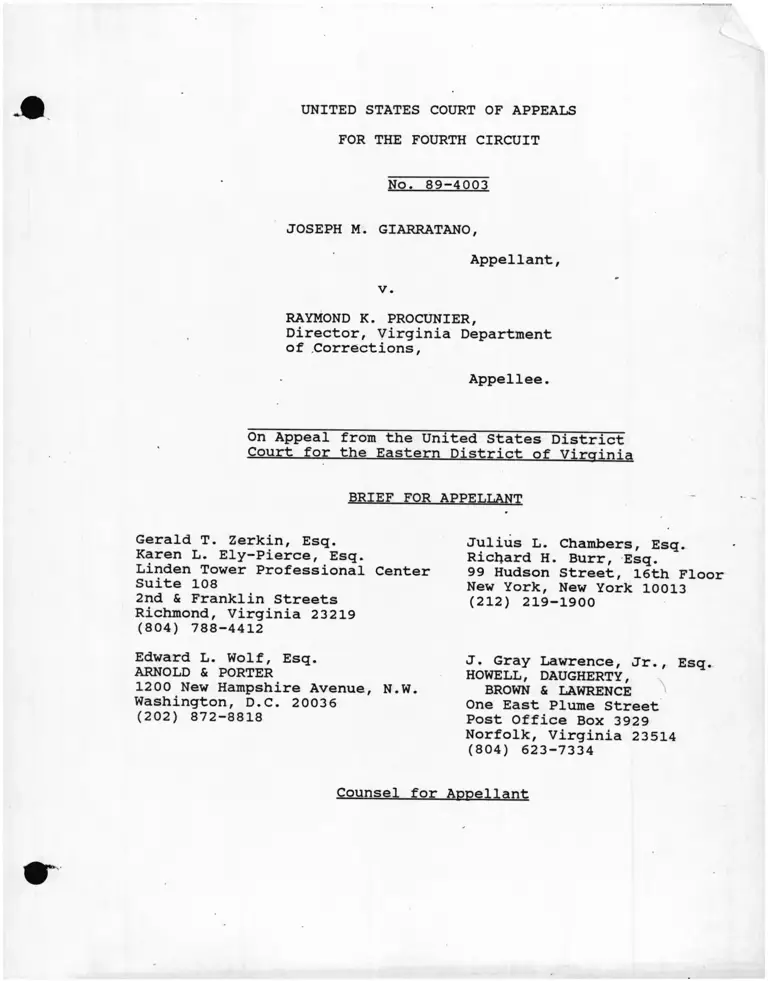

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 89-4003

JOSEPH M. GIARRATANO,

Appellant,

v.

RAYMOND K. PROCUNIER,

Director, Virginia Department

of Corrections,

Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Virginia

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Gerald T. Zerkin, Esq.

Karen L. Ely-Pierce, Esq.

Linden Tower Professional Center

Suite 108

2nd & Franklin Streets

Richmond, Virginia 23219

(804) 788-4412

Edward L. Wolf, Esq.

ARNOLD & PORTER

1200 New Hampshire Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 872-8818

Julius L. Chambers, Esq.

Richard H. Burr, Esq.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

J. Gray Lawrence, Jr., Esq.

HOWELL, DAUGHERTY,

BROWN & LAWRENCE

One East Plume Street

Post Office Box 3929

Norfolk, Virginia 23514

(804) 623-7334

Counsel for Appellant

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

STATEMENT OF ISSUES ..................... 1

COURSE OF PRIOR PROCEEDINGS............................ 2

STATEMENT OF MATERIAL FACTS................. 4

A. Facts Underlying the Claims

Pertaining to Competence to

Stand Trial and the Unconsti

tutional Consideration of

Aggravating and Mitigating

Circumstances................................. 4

(i) Introduction....................... 4

(ii) Mr. Giarratano's confessions....... 8

(iii) Pretrial psychiatric

evaluation and the

emergence of an

unswerving desire to

be convicted and sentenced

to death......................... 1q

(iv) The guilt-innocence phase of

Mr. Giarratano's trial............ 14

(v) The sentencing phase of

Mr. Giarratano's trial............. 16

(vi) Death row, 1979-1983: a

period of torment followed

by a metamorphosis........ :........ 18

(vii) The first, limited recognition

that Mr. Giarratano was incompetent

during his trial proceedings...... 21

(viii) The full recognition that

Mr. Giarratano was incompetent

in relation to every aspect

of his trial proceedings......... 2 3

(ix) The fundamental absence of

evidence establishing that

Mr. Giarratano is guilty or

that he poses a threat of

dangerousness in the future........ 28

1

(x) Mr. Giarratano's inability to

disclose the information that was

necessary to construct his defense

was the product of mental and

physical disabilities.............. 33

B. Facts Underlying the Estelle v.

Smith Claim............................. 36

ARGUMENT

I. MR. GIARRATANO HAS ALLEGED FACTS WHICH

DEMONSTRATE (A) THAT HE WAS INCOMPETENT

TO STAND TRIAL SINCE HE COULD NOT CONSULT

WITH COUNSEL IN THE WAY THE CIRCUMSTANCES

OF HIS CASE REQUIRED THAT HE BE ABLE TO,

AND (B) THAT HIS COMPETENCE TO STAND TRIAL

WAS NOT ADEQUATELY EXPLORED — DUE TO THE

DEFAULTS OF THE PERSONS CHARGED WITH

EVALUATING HIS COMPETENCE, OR OF DEFENSE

COUNSEL, OR BOTH — AND THUS, THE DISTRICT

COURT'S SUMMARY DISMISSAL OF THESE CLAIMS

CANNOT BE SUSTAINED.........................

A. The Claim That Mr. Giarratano Was

Tried When He Was Incompetent..........

B. The Claim That Mr. Giarratano's Right

to an Adequate Inquiry Into

Competency Was Violated By The

Defective Inquiry in His Case..........

C. The Errors in the District Court's

Judgment................................

II. PSYCHIATRIC TESTIMONY INTRODUCED AGAINST MR.

GIARRATANO AT THE SENTENCING PHASE OF HIS

TRIAL TO PROVE HIS "FUTURE DANGEROUSNESS"

WAS CONSTITUTIONALLY INADMISSIBLE, AND THIS

COURT SHOULD ADDRESS THIS CLAIM ON ITS MERITS

NOTWITHSTANDING TRIAL COUNSEL'S FAILURE TO

OBJECT.......................................

A. Affirmative prosecutorial use of

statements elicited from a defen

dant during a pretrial mental

evaluation, and of opinions based

on such statements, for the purpose

of proving an aggravating

circumstance at a capital

s e n t e n c i n g proceeding, is

prohibited by the Fifth and

Fourteenth Amendments..................

3 8

40

45

48

54

54

11

B. Psychiatric testimony offered in

mitigation by Mr. Giarratano did

not open the door to the

prosecution's affirmative use of

Dr. Ryans' testimony..............

C. Even if Dr. Ryans' testimony was

not barred by the Fifth Amendment,

it w a s c o n s t i t u t i o n a l l y

inadmissible under the Sixth

Amendment.........................

D. This Court should address

Giarratano's constitutional

objection to Dr. Ryans' testimony

on its merits because he has shown

both "cause" for, and prejudice

resulting from, the procedural

default in state court......... ........

III. THE FINDING OF "FUTURE DANGEROUSNESS' AS THE

SOLE AGGRAVATING CIRCUMSTANCE IN MR.

GIARRATANO'S CASE FAILED TO SUITABLY DIRECT

AND LIMIT HIS SENTENCER'S DISCRETION........

A. The Constitutionally Necessary

Narrowing Function of Aggravating

Circumstances...................... .

B. The Failure of Virginia's "Future

Violent Crimes" Aggravating

Circumstance to Suitably Direct and

Limit the Sentencer's Discretion.......

C. The Egregious Failure of the Future

V iolent Crimes Aggravating

Circumstance to Suitably Direct and

Limit the Sentencing Court's

Discretion in Giarratano's Case........

IV. THE SENTENCER UTILIZED THE INDISPUTABLY

MITIGATING EVIDENCE OF MR. GIARRATANO'S

MENTAL AND PHYSICAL ILLNESS AS AGGRAVATING

EVIDENCE TO SUPPORT THE FINDING OF FUTURE

DANGEROUSNESS, IN VIOLATION OF THE EIGHTH AND

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS..................

A. The Death Penalty May Not Be

Imposed Based Upon A Finding Of

56

61

64

70

70

72

79

83

i n

Future Dangerousness Where The

Factual Predicate Of That Finding

Lies In The Defendant's Mental

Illness, Disorder Or Defect, Or In

His History Of Substance Abuse.......... 84

B. The Penalty Of Death Is Excessive

And Disproportionate In Relation To

Petitioner's Degree Of Culpability....... 90

CONCLUSION.............................................. 91

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE.................................. 93

xv

Ake v. Oklahoma, 470 U.S. 68 (1985) ....................... 41,59,61

Barefoot v. Estelle, 463 U.S. 880 (1983) .................. 73

Bassett v. Commonwealth, 222 Va. 844 (1981) ............... 75,78

Beaver v. Commonwealth, 232 Va. 521 (1987) ............... 77,78

Blackledge v. Allison, 431 U.S. 63 (1977) ................ 48

Briley v. Commonwealth, 221 Va. 532 (1980) ............... 78

Briley v. Commonwealth, 221 Va. 563 (1980)................. 78

Briley v. Bass, 750 F.2d 1238 (4th Cir. 1984).............. 78

Buchanan v. Kentucky, 107 S. Ct. 2906 (1987) .............. 57,62

California v. Brown, 479 U.S. 538 (1987) ................. 90

Caudill v. Peyton, 368 F.2d 563 (4th Cir. 1966) ........... 48

Clanton v. Muncy, 845 F.2d 1238 (4th Cir. 1988)........... 77

Clanton v. Commonwealth, 223 Va. 41 (1982) . .*............ 78

Clark v. Commonwealth, 220 Va. 201 1979) ................. 75,78

Clozza v. Commonwealth, 228 Va. 124 (1984) ............... 78

Coleman v. Commonwealth, 226 Va. 31 (1983) ............... 78

Coley V. State, 231 Ga. 829 204 S.E.2d 612 (1974) ........ 7

Collins v. Auger, 577 F.2d 1107 (8th Cir. 1978) ........... 60

Cuevas v. State, 742 S.W. 2d 331

(Tex. Cr. App. 1987) .................................. 81

Delong v. Commonwealth, 234 Va. 357 (1987) ............... 78

Drope v. Missouri, 420 U.S. 162, 171 (1975) .............. 40,42,

............. ..................................... 45,47,49

Dugger v. Adams, 57 U.S.L.W. 427 (Feb. 28, 1989) ......... 68

TABLES OF AUTHORITIES

CASES PAGES

v

CASES PAGES

Dusky v. United States, 362 U.S. 402 (1962)

Eddings v. Oklahoma, 455 U.S. 104 (1982)...

Edmonds v. Commonwealth, 229 Va. 303 (1985)

Estelle v. Smith, 451 U.S. 454 (1981)___

Evans v. Lewis, 855 F.

(11th Cir. 1988) .

2d 491

Evans v. Commonwealth, 222 Va. 766 (1981)

Evans v. Commonwealth, 228 Va. 468 (1984)

Fisher v. Commonwealth _____ Va. ____,

374 S.E. 2d 46 (1988) ...................

Frye v. Commonwealth 231 Va. 370 (1986) ......

Giarratano v. Commonwealth, 220 Va. 1064 (1980)

Gibson v. Zahradnick, 581 F.2d 75

(4th Cir. 1978) cert denied.

439 U.S. 996 (1979) ......................

Godfrey v. Georgia, .446 U.S. 420 (1980) ......

Gray v. Commonwealth, 233 Va. 313 (1987) .....

Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976) ........

Hoke v. Commonwealth, ___ Va. __, S.E. 2d ____,

No. 880268 (Va., Mar. 3, 1989) ...........

Ingram v. Peyton, 367 F.2d 933 (4th Cir. 1966)

Jurek v. Texas, 428 U.S. 262 (1970) ..........

Jurek v. Texas, 428 U.S. 262 (1976) ..........

Kibert v. Peyton, 383 F.2d 566,

(4th Cir. 1967) ............. .............

LeVasseur v. Commonwealth, 225 Va. 564 (1983) .

Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586 (1978) .........

Lowenfield v. Phelps, ___ U.S. ___, 108”

S.Ct. 546 (1988)..........................

...... 40,52-52

..... 86

..... 76,78

..... 54,56,58,

59,60,61,62,63,65

..... 86,88

...... 78

78

..... 78

..... 78

..... 2,78-79

..... 54,56,59,65

..... ■ 77,79,90

..... 78

..... 70,77

..... 78

...... 4

..... 73,76

..... 58

..... 48

..... 76,78

..... 86

..... 72

vx

CASES PAGES

Machibroda v. United States, 368 U.S. 487

(1962) ................................................ 48

Mackall v. Commonwealth, ____ Va. ___,

372 S.E. 2d 759 (1988) ............................... 78

Mason v. Commonwealth, 219 Va. 1091 (1979) ............... 78

Mathis v. Zant, 704 F. Supp. 1062

(N.D.Ga. 1989) ........................................ 87,88

Maynard v. Cartwright, ___ U.S. ____, 108

S. Ct. 1853 (1988) Passim

McCleskey v. Georgia, ___U.S. ___, 107

S.Ct. at 1756 (1987) .................................. 71

Middleton v. Dugger, 849 F.2d 491

(11th Cir. 1988) ................................ 86-87

Miller V. Florida, 373 So. 2d 882 (Fla. 1979)............. 85-86,88

O'Dell v. Commonwealth, 234 Va. 672 (1988) ................ 78

Owsley v. Peyton, 368- F. 2d 1002 (4th Cir. 1966) ........... 48

Pate v. Robinson, 383 U.S. 375 (1966) ..................... 45,59

Payne v. Commonwealth, 233 Va. 460 (1987) ................ 78

Peterson v. Commonwealth, 225 Va. 289 (1983) ............. 78

Pope v. Commonwealth, 234 Va. 114 (1987) ...... ........... 78

Pouncey v. United States, 349 F.2d 699

(D.C. Cir. 1965) ...................................... 43

Poyner v. Commonwealth, 229 Va. 401 (1985) ............... 78

Pulley v. Harris, 465 U.S. 37 (1984) ...................... 71

Quintana v. Commonwealth, 224 Va 127 (1982) ............... 6,7,13

Rees v. Peyton, 384 U.S. 312 (1966) .............. ........ 50

Roberts v. Louisiana, 431 U.S. 633 (1977) ................ 88

Rougeau v. State 738 S.W. 2d 651

(Tex. Cr. App. 1987) ................................... 81

- vii -

CASES PAGES

Satterwhite v. Texas ______ U.S. ________,

108 S. Ct. 1792 (1988) ................................. 64

Skipper v. South Carolina, 476 U.S. 1 (1986) .............. 61

Smith v. Commonwealth, 219 Va. 455 (1978) ................ 73,74,78,79

Smith v. Murray, 477 U.S. 527 (1986) ...................... 64,65,67

Smith v. Estelle, 445 F. Supp. 647

(N.D. Tex 1977) . ....................................... 65

Stamper v. Commonwealth, 220 Va. 260 (1979) .............. 75,78,81

Stockton v. Commonwealth, 227 Va. 124 (1984) ............. 78

Stout v. Commonwealth, ___Va. _____,

376 S.E.2d 288 (1988) ................................. 78

Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. (1984) ................ 42,67

Townes v. Commonwealth, 234 Va. 397 (1987) ................ 78

Townsend v. Sain, 372 U.S. 293, (1963) ................... 48

Tuggle v. Commonwealth, 230 Va. 99 (1985) ................ 7 8

Tuggle v. Commonwealth, 230 Va. 313 (1987) ................ 78

Turner v. Bass, 753 F.2d 342, 351 (4th Cir. 1985) ......... 77

Turner v. Commonwealth, 221 Va. 513 (1980)................ 78

United States v. Leonard, 609 F.2d 1163

(5th Cir. 1980) ....................................... 60

United States ex rel. Brown v. Fogel

395 F. 2d 291 (4th Cir. 1968) ........................ 4

Wainright v. Sykes, 433 U.S. 72 (1977) ................... 64,67

Watkins v. Commonwealth, 229 Va. 469 (1985) ............... 78

Williams v. Commonwealth, 234 Va. 168 (1987) ............. 78

Williams v. Lynaugh, 809 F.2d 1063 (5th Cir. 1987) ........ 57

Wilson v. United States, 391 F.2d 460 (D.C. Cir. 1968) .... 43

Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280 (1976) ........... 6

Zant v. Stephens, 462 U.S. 862 (1983) .................... 70,77,84,85

- viii -

Statutes

Va. Code Ann. § 19.2 - 264.2 ........ 72,75,79,80

Va. Code Ann. § 19.2 - 264.3:1 (G).......................... 60

Va. Code Ann. § 19.2 - 264.4 (c).................. ......... 72,75,79

Virginia Acts of Assembly, Ch. 492 (1977)................... 73

Other Authority

Bedau and Radelet, Miscarriages of Justice

in Potentially Capital Cases, 40 Stan. L

Rev. 21 (Nov. 1987) .................................... 7,49

Bennett and Sullwold, Competence to Proceed:

A Functional and Context-Determinative

Approach, 29 J For Sci, 1119

(Oct. 1984) ............................................ 42,47

Black, Capital Punishment: The Inevitability

of Caprice and Mistake (1974) ................. ........ 84

Note, Incompetency to Stand Trial,

81 Harv. L. Rev. 455 (1967) ............................... 41

Note, Mental Illness as Aggravating

Circumstances in Capital Sentencing,

89 Colum. L. Rev. 291 (1989) ...... 84,86

IX

STATEMENT OF ISSUES

1(a). Whether a person whose mental and physical dis

abilities prevented him at trial from disclosing to his attorney

how he came to believe that he committed two murders despite the

absence of any memory for the crime, how and why he confessed

thereafter, and why he became so driven to kill himself or be

executed — in a case where there is almost no independent

evidence corroborating the confessions — is entitled to an

evidentiary hearing on his claim of incompetence to stand trial?

1(b). Whether a pretrial inquiry into competence to stand

trial is adequate under the Due Process Clause where there is

evidence not taken into account by the evaluating psychiatrist

of the defendant's inability to remember the events of the crime

and of the defendant's overwhelming suicidal thinking and

behavior, and where defense counsel's difficulties in obtaining

information and cooperation from his client are never revealed

and evaluated by the court or the court's appointed expert?

2. Whether psychiatric opinion tending to establish

"future dangerousness," developed on the basis of an interview

with the defendant without appropriate warnings or notice to

counsel, can be constitutionally admissible where the defendant's

psychiatrist offers mental disability evidence solely as a

mitigating circumstance and not as rebuttal of "future dangerous

ness?"

1

3. Whether Virginia's unlimited and unconstrained

application of the "future dangerousness" aggravating cir

cumstance violates the principles of Maynard v. Cartwright and

leads to the unguided and arbitrary capital sentencing of someone

like petitioner?

4. Whether utilization of the indisputably mitigating

evidence of petitioner's mental and physical illness as aggravat

ing evidence to support the finding of "future dangerousness"

comports with the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments?

COURSE OF PRIOR PROCEEDINGS

On May 22, 1979, • the petitioner Joseph Giarratano was

convicted in a bench trial in the Circuit Court for the City of

Norfolk, Virginia of capital murder in the death of Michelle

Kline and of first degree murder in the death of Barbara Kline.

On August 13, 1979, Mr. Giarratano was sentenced to death.

Thereafter, the Virginia Supreme Court affirmed the conviction

and sentence. Giarratano v. Commonwealth. 220 Va. 1064, 266

S.E.2d 94 (1980).

A State habeas corpus proceeding was then undertaken. The

Circuit Court denied relief in two separate orders, entered May

26, 1981 and November 13, 1981. The Virginia Supreme Court found

"no reversible error" in the Circuit Court's judgment and denied

Mr. Giarratano's petition for appeal on November 30, 1982.

Federal habeas corpus proceedings were begun thereafter in

the United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Virginia. The habeas petition was amended twice, and the "Second

2

Amended Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus" became the operative

pleading for Mr. Giarratano. On October 1, 1985, the District

Court denied relief on all claims except the claim that Mr.

Giarratano was incompetent to participate in the sentencing

portion of his capital trial. Thereafter, on June 25, 1986, the

court denied relief on this claim as well and entered final

judgment on the petition. Entry of the final judgment was

stayed, however, to permit Mr. Giarratano to present his

competency claim to the state courts.

A second state habeas corpus proceeding was then pursued by

Mr. Giarratano. On July 9, 1987 the Circuit Court denied the

petition summarily, and on June 17, 1988, the Virginia Supreme

Court refused the petition for appeal.

Mr. Giarratano then sought leave to amend his federal

petition in order to present to the District Court his fully

developed claims concerning his competence to be tried — not

limited to his sentencing trial but focused upon his entire

trial. By order of December 6, 1988, the District Court denied

Mr. Giarratano leave to amend on the ground that there was no

merit to the claims he sought to have amended into the petition.

Final judgment was entered, a certificate of probable cause was

granted, and a timely notice of appeal was filed.

3

STATEMENT OF MATERIAL FACTS

A. Facts Underlying the Claims Pertaining to Competence to

Stand Trial and the Unconstitutional Consideration of

Aggravating and Mitigating Circumstances^

(i) Introduction

The case of Joe Giarratano is by no means typical. It is a

case which, at trial, was "open and shut." There was a detailed

confession, there was physical evidence that seemed to cor

roborate the confession, and while there was some question about

Mr. Giarratano's impulsiveness and impaired self-control due to

some mental disorder and the longstanding and acute effects of

alcohol and drug consumption, the question did not rise to the

level of a substantial defense. Personally, Mr. Giarratano was

depressed and suicidal. However, his history appeared to be one

of violence, and his threats to the staff at Central State

Hospital, where he was sent for pretrial evaluation, confirmed

that he posed a threat of dangerousness for the future.

In the ten years since his trial, Mr. Giarratano's case has

become anything but an open and shut case. The first four-and-

one-half years on death row were tumultuous for him. During

those years, he continued to be very suicidal, he was tormented

1 As we explain, infra at 48-49, the District Court denied

Mr. Giarratano's competency claims without an evidentiary

hearing. Accordingly, this Court must treat the allegations of

fact pertaining to this claim as true. See United States ex rel.

Brown v. Fogel. 395 F.2d 291 (4th Cir. 1968); Ingram v. Pevton.

367 F.2d 933 (4th Cir. 1966).

4

by psychotic hallucinations and delusions and bizarre thinking,

and was torn apart by profound anger at himself and feelings of

worthlessness. In late 1983, however, with the therapeutic

intervention and counseling of Marie Deans, a very different Joe

Giarratano began to emerge. The torment of psychotic processes

subsided, feelings of self-worth began to grow, and — most

important for purposes of his case — he began to develop some

perspective on his life and, thereafter, on the crime for which

he had been convicted and sentenced to death.

Gradually, Mr. Giarratano began to talk about things that

were important. First, he began talking about his life: about

the unspeakable horrors inflicted upon him by his mother and

stepfather from early childhood through late adolescence, about

the drug trafficking and drug traffickers that infested his

childhood home, about the ridicule and abuse inflicted upon him

by his mother's drug trafficking friends with his mother's

consent, about the gnawing feelings of loneliness and isolation

and worthlessness, which first led him to consume alcohol and

drugs at the age of eleven and which pushed him to abuse these

substances continually for the next ten years of his life, and

about his first suicide attempt at the age of fifteen. In the

course of talking about his life, he also began to talk about the

people who knew him — adolescent friends in Jacksonville and

adult friends in Norfolk and elsewhere. Contact with these

people confirmed Mr. Giarratano's extraordinary drug usage, but

it also revealed something else: that Mr. Giarratano was not a

5

violent person, that he was instead a "really good person," who

"would reach out to help other people," and who was "a good

friend."

Finally, Mr. Giarratano began to talk about things that he

had never been able to talk about before: what his actual

memories were of the crime and why he confessed to it. His

actual memory was of "waking up" in the murder victims' apartment

and finding them dead. Frightened, in a drug and alcohol stupor,

unable to think what else might have happened, Mr. Giarratano

came to believe that he had killed Michelle and Barbara Kline.

He had no memory of killing them, but in his damaged mental and

physical state, he was especially vulnerable to blaming himself

for the murders and for coming to believe that he had committed

them. What followed thereafter was a period of consolidation,

during which he became absolutely certain that he was the

murderer, that he was irredeemably evil, and that he should die.

He gave a detailed confession to the Norfolk police, in which he

accepted the detail of the crime as they suggested them, and he

thereafter did all he could to assure that he would be convicted

and sentenced to death. He revealed none of his thought proces

ses to his lawyer, because he had no ability to take a step back

and see what was happening. He was totally immersed in his own

irrational processes. He was, in short, "'the deluded instrument

of his own conviction."' Culombe v. Connecticut. 367 U.S. 568,

581-582 (1961) (quoting 2 Hawkins, Pleas of the Crown 595 (8th

ed. 1824)).

6

With these revelations, Mr. Giarratano's counsel began for

the first time to examine the other components of the state's

case of guilt against Mr. Giarratano. What was found was at

first astounding, and then shocking. The state's evidence apart

from Mr. Giarratano's confessions was virtually non-inculpatory,

even when subjected to cursory examination. When examined

critically and subjected to investigation, the state's evidence

lost all of its inculpatory gloss. In short, counsel for Mr.

Giarratano have found that, apart from his own confession, there

is no evidence tending to show that Mr. Giarratano killed

Michelle and Barbara Kline.

It is against this background that the Court must evaluate

Mr. Giarratano's claims related to his competence to stand trial.

As implausible as it may seem at first blush, the facts suggest

quite strongly that because of incompetency, an innocent person

has confessed to crimes he did not commit. Such a thing is, to

be sure, exceedingly rare, but it has happened in at least a

handful of other cases. See. e.g.. Bedau & Radelet, Miscarriages

of Justice in Potentially Capital Cases. 40 Stanford L. Rev. 21,

116, 140, 160, (Nov. 1987) (cases of John Fry, Camilo Leyra, and

Joseph Shea).

In sum, the case of Joe Giarratano is truly a modern-day

odyssey, and like the odyssey of Ulysses, it is not a simple

story. It is, however, unlike the story of Ulysses, a true

story, which deserves a fair hearing.

7

(ii) Mr. Giarratano1s confessions

At 3:20 a.m. on February 6, 1979, Joe Giarratano walked up

to Deputy Sheriff Charles Wells in the Greyhound station in

Jacksonville, Florida. Wells, who was a deputy in the Jackson-

ville-Duval County Sheriff's Department, was providing security

in the bus terminal and at that time was eating breakfast. JA

203. Mr. Giarratano asked Deputy Wells if he' could talk with

him, Wells said that he could, and Giarratano then said "that he

had killed two women in Norfolk, Virginia, and wanted to turn

himself in." JA 203-204. Mr. Giarratano "appear[ed] to be

rational" at that moment to Deputy Wells. JA 207. On further

questioning, Mr. Giarratano told Deputy Wells that "the lady in

Norfolk . . . owed him a thousand dollars and she refused to pay

and an argument ensued and he killed her." JA 206. He also told

Deputy Wells that "after he had killed the lady ... her daughter

became excited and started to scream, so he strangled her and

raped her." JA 207.

Within the next hour, Mr. Giarranto was questioned by two

other Jacksonville deputies, Mooneyham and Baxter. He gave the

same explanation of why he killed Barbara Kline which he had

given to Deputy Wells (an argument over $1,000), JA 209, but he

also told Deputies Mooneyham and Baxter how he killed Barbara

Kline: by "pick[ing] up [a] kitchen knife and stabb[ing] her

three or four times." Id. Mr. Giarratano then explained that

"Michelle Kline was there and began to scream, and he strangled

her." JA 210. He mentioned nothing about sexually assaulting

her. Id.

Mr. Giarratano's most detailed confession was given two days

later, on February 8, 1979, to Norfolk detectives Mears and

Whitt. JA 455-461. In this confession, Mr. Giarratano explained

that he had lived with Barbara Kline in her apartment in Norfolk

for three or four weeks, but that he had moved out three days

before the murders. JA 456-457. He said that Michelle admitted

him into the apartment at about 8:00 p.m. on Sunday night

(February 4, 1979). JA 457. He was under the influence of four

grams of Dilaudid. Id. He and Michelle talked for a while and

then Michelle began massaging his neck and "rubbing up against"

him. JA 458. They went into the bedroom, Mr. Giarratano tried

to persuade Michelle to have sex with him, but she refused. Id.

Thereafter,

[S]he started to leave the room and I grabbed

her and jerked her back in there and threw

her on the bed and she thought I was just

joking around. She unbuttoned her top. I

started taking off her pants. She started

fighting and resisting me and screamed. I

told her to shut up and I raped her. After I

finished she started hollering and screaming

and I told her to shut up, she wouldn't so I

strangled her with my hands.

Id. Mr. Giarratano then threw a blanket over Michelle and left

the apartment. Id. He returned, however, because he "noticed

the lights were on in the house." Id. While he was still in the

apartment, Barbara returned. JA 459. Mr. Giarratano heard her

banging on the door. Id. Thereafter,

9

I grabbed a knife out of the kitchen and I

waited by the wall in the living room and she

unlocked the door and came up and I jumped

out and was going to run down the stairs [.]

[S]he started screaming and I stabbed her.

Id.2 Mr. Giarratano then left the apartment, locking the "bottom

door" (the ground level entry door, which led to the stairs to

the Klines' second floor apartment). JA 460. After walking a

considerable distance, he took a taxi to the bus station, where

he boarded a bus to Jacksonville at 6:00 a.m. Id.

(iii) Pretrial psychiatric evaluation and the emergence of

an unswerving desire to be convicted and sentenced to

death

Approximately one week after he gave this confession,

following his return to Norfolk from Jacksonville, Mr. Giarratano

tried to hang himself in the Norfolk jail. Shortly thereafter,

on the prosecutor's motion, Judge McNamara found "reason to

believe that the mental condition of the defendant and his

competency to stand trial should be examined." JA 548 (record of

competency inquiry). He appointed Dr. J. S. Santos to examine

Mr. Giarratano. Id. On February 17, 1979, after Dr. Santos had

seen Mr. Giarratano and concluded that he "is in need of emer

gency hospitalization at CSH [Central State Hospital] for his

mental difficulties," JA 551, Judge McNamara ordered that Mr.

Giarratano be hospitalized and evaluated at Central State

Hospital. JA 549.

2 At another point in the written statement, the officer

asked Mr. Giarratano why he stabbed Barbara Kline, and he

responded, "I stayed there because I knew Barbara would know I

was the one that killed Michelle and I wanted to keep her from

telling." JA 461.

10

In the course of Mr. Giarratano's ten-day hospitalization at

Central State Hospital, from February 17-26, 1979, the staff who

evaluated him were continually presented with suicidal ideation

and behavior, and with his overwhelming conviction that he must

die because he had killed the Klines:

(a) On February 22, Mr. Giarratano attempted to hang

himself again. As the note from his medical record recounts,

Pt. Giarranto [sic] was discovered in the

patients bathroom with his shirt tied tightly

around his neck. He was attempting suicide

and also stated that he 'would have been

gone' if it had not been for another patient.

He also stated that he 'had to pay for the

crimes' that he committed.

JA 566.

(b) The next day he again said that he had to kill

himself because he had killed two people. JA 568.

(c) On February 26, Mr. Giarratano became very

agitated and was placed in restraints "for the protection of

himself and others." Throughout the day, his behavior was noted

as follows: "hostile, threatening," "behind gate cursing the

aides and other patients," "still hostile and cursing and

threatening the aides and other patients," and "[rjemains hostile

and uncooperative, arrogant and belligerent." JA 572.

In the course of an interview with Dr. Miller Ryans, the

person who headed the evaluation team, Mr. Giarratano was asked

about the details of the murders. Notwithstanding his

intervening statement to Detectives Mears and Whitt, Mr.

Giarratano relapsed into a version of events which he had earlier

11

recounted to the Jacksonville officers, prior to his

interrogation by Detectives Mears and Whitt. As Dr. Ryans

reported,

[Mr. Giarratano] admits that he was upset

because the alleged victim 'did me an

injustice. She lied to me about what had

happened to my fifteen hundred dollars so I

kicked the door down, cut her throat and

choked her fifteen year old daughter to

death. ' He denies the rape and burglary

charges.

JA 550.3

Notwithstanding these experiences with Mr. Giarratano, the

Central State staff reported to the trial court that he was

competent to stand trial:

3 At trial, Dr. Ryans acknowledged that Mr. Giarratano had

"his temporal sequence reversed" when he talked with him about

the crime. Joint Appendix on direct appeal to Supreme Court of

Virginia, No. 791619 [hereafter referred to as "JA/DA"], at 98.

His explanation for this was the following:

I would attribute it to the combination of

the drugs. Now, as I said, he admitted to

being high on cocaine and Dilaudid and

inferred that he was also a heavy user of

alcohol. Now, there is an entity called

Korsakoff's syndrome in which a person has

peripheral neuropathy, loss of recent memory

„ and they confabulate. That is, under the

influence of these various medications and

beverages they are aware of what happened,

but they can't get it straight in their mind

so they confabulate by saying what makes

sense, what should have happened here and

then they say, well, most likely this is what

happened and they make up things and they

confabulate consistent with what we call a

Korsakoff's syndrome. They are not doing it

on purpose, but they simply can't remember,

so they will say this is what most likely

happened so this is what I will say.

JA/DA 98-99.

12

Our evaluation of this young man reveals him

to be in good contact with his environment,

alert, coherent and relevant and free of any

evidence of mental disorganization. There is

no evidence of brain damage, mental illness

(insanity) or feeblemindedness. Mr.

Giarratano is aware of the charges pending

against him, the seriousness of his legal

situation and the possible outcome of a

trial. This man is considered to be mentally

competent and capable of participating in the

proceedings pending in your Court.

JA 554.

Mr. Giarratano's first contact with his attorney took place

after his return to the Norfolk jail from Central State. JA 145-

146. From early on, Mr. Giarratano informed his attorney that he

wanted to die:

[T]here had been between Joe and I a

longstanding discussion of his ambivalence,

whether or not he wished to live or die.

That ambivalence had been with him ever since

I started talking with him.

JA 150-151 (state habeas corpus hearing testimony of Albert

Alberi, Mr. Giarratano's trial counsel). Mr. Giarratano's

"ambivalence" about living or dying interfered with his lawyer's

representation of him, because he freguently failed to assist his

lawyer and at times even worked against him:

His ambivalence and his state of mind made it

difficult for me to do it [the presentation

of evidence or the handling of hearings]

right, because I had the feeling that he and

I at times were working, at cross purposes to

each other. I did the best that I ... could

do. I tried to put out everything that I

could. I tried to find everything that there

was to say. It troubled me at times that I

knew that he was there and he didn't seem to

want to give me any great help.

13

information his attorney asked him to provide:

He was difficult for me to fathom because in

questioning him he would give very flat

answers to my questions. If I'd ask him why

he did something, he'd give an answer which

in my estimation was not very well developed

or amplified.

JA 152.

Despite these difficulties, Mr. Alberi continued to believe

that Mr. Giarratano was competent, and thus he raised no question

with the court about competence. JA 154. Nevertheless every

decision made by Mr. Giarratano, every action taken, and every

front on which he failed to assist in his attorney's efforts to

defend him, seemed calculated to assure his conviction and

sentence of death. Thus,

(a) he rejected a plea bargain offered by the state

which would have resulted in a sentence of imprisonment rather

than a sentence of death, JA 440-441;

(b) he decided to pursue an insanity defense against

his lawyer's advice that the defense could not succeed since

there was no evidence of insanity, id.; and

(c) he wrote to Judge McNamara just before sentence

was imposed urging him to impose a death sentence "to end my

pain," Circuit Court file, No. F1144-79, Circuit Court of the

City of Norfolk.

(iv) The guilt-innocence phase of Mr. Giarratano's trial

The case against Mr. Giarratano in the guilt phase of his

trial rested upon his confession to Detectives Mears and Whitt on

JA 155. Moreover, Mr. Giarratano was not forthcoming with

14

February 8, 1979, JA 178-184, and upon several items of physical

evidence which were presented as corroborative of his confession:

(a) a single pubic hair, consistent with but not

necessarily identical to Mr. Giarratano's pubic hair, which was

found among a number of hairs collected from Michelle Kline's

"left hand, stomach, and pubic area," JA/DA, at 82-83;

(b) the presence of type 0 human blood on the front

and left side of the right boot apparently worn by Mr. Giarratano

on the night of the homicides, JA/DA 83 ;4

(c) the blood type of Michelle Kline, which was type

0, JA/DA 83 (referring to lab report containing this

information);

(d) the presence of "intact spermatozoa" in Michelle

Kline's vaginal tract, which was indicative of sexual intercourse

within twenty-four hours of her death, JA/DA 83-84, 85-86;

(e) the finding during the autopsy of Michelle Kline

of "lacerations of the vaginal wall" and "bleeding from the

vagina," which were "consistent with sexual abuse," JA/DA 23;

(e) the medical examiner's finding that Michelle Kline

died as a result of asphyxia from strangulation, JA/DA 26; and

(f) the medical examiner's finding that Barbara Kline

died as a result of bleeding from stab wounds to the neck and

abdomen, JA/DA 20.

4 This boot was from the pair taken from Mr. Giarratano by

the Norfolk police. See JA 185.

15

At the sentencing phase of Mr. Giarratano's trial, the

Commonwealth presented the testimony of Dr. Miller Ryans, who had

evaluated Mr. Giarratano before trial at Central State Hospital,

JA/DA 152-167, and the testimony of probation officer John

Jacknik, who testified about the presentence investigation report

he prepared, JA/DA 138-151. A copy of his report was made a part

of the record, JA/DA 151, and it is included in the state

appellate record, at JA/DA 278-287. The defense presented the

testimony of Dr. Robert Showalter, who evaluated Mr. Giarratano

at the request of the defense between the guilt and sentencing

phases of the trial. JA/DA 168-200. The court's findings

reflect the evidence presented.-

The sole aggravating circumstance found by the trial judge

was "that there is a probability that the defendant would commit

criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing

serious threat to society." JA 214. The evidence found to

support this conclusion was the following:

(a) Mr. Giarratano's prior convictions — for "drug

abuse, grand larceny[,] possession of a concealed weapon[,]

battery of a law enforcement officer, aggravated assault[,] and

escape," JA 214;5

5 The charges of grand larceny and possession of a

concealed weapon arose from the same incident, when Mr.

Giarratano was a juvenile. JA/DA 286. The escape was from a

juvenile institution. Id. The battery and aggravated assault

charge arose from the same incident, when Mr. Giarratano was

twenty years old. Id.

, (v) The sentencing phase of Mr. Giarratano1s trial

16

(b) Mr. Giarratano's history of heavy drug usage and

involvement in his family's illegal activities, JA 215;

(c) Mr. Giarratano's threats of future violence which

were expressed to Dr. Ryans, and Mr. Jacknik, id.;6

(d) Mr. Giarratano's stated motives for committing the

murders, which reflected a need to prevent arrest or the view

that the victims "'deserved to die,'" JA 215-216;

(e) the commission of a second murder — of Barbara

Kline — after the first, JA 216; and

(f) medical opinion, from both Dr. Ryans and Dr.

Showalter, which expressed the view that Mr. Giarratano suffered

mental and emotional disorders which made him vulnerable to

committing violent acts in the future, JA 216-220.

The mitigating circumstances considered by the trial court

were based on the same evidence underlying the "medical opinion"

component of the findings in support of future dangerousness.

Compare JA 221-227 with JA 216-220. According to the trial court

this evidence established:

(a) That the defendant was suffering from

severe emotional damage inflicted during his

childhood by abusive treatment and

environment[,] resulting in repressed anger

and hatred toward his mother and sister which

surfaced during his association with the

mother and daughter victims in this case, and

became directed toward them symbolically; ...

6 "To Dr. Ryans: 'I am going to kill myself, but I will

take your aide with me.' To Mr. Jacknik: 'Imprisoned for 40

years, sooner or later I would fight, kill someone instead of

getting beaten.'" JA 215.

17

(b) That the defendant was heavily under the

influence of drugs and alcohol at the time of

the offense and has a history from childhood

of excesses and abuse of these substances

evidenced by actual physical damage to his

liver; [and]

(c) That the combination of these factors

caused extreme emotional stress and a low

threshold of self control.

JA 221-222.

The trial court imposed the sentence of death, despite these

mitigating circumstances, on the basis of the following

reasoning:

[T]he evidence of emotional stress and

reduced control[,] while admissible by

statute and carefully considered by the Court

is not of such nature as to mitigate the

penalty in this case. By becoming an

habituate of drugs and alcohol[,] one does

not cloak himself with immunity from penalty

for his criminal acts.

JA 221.

(vi) Death row, 1979-1983: a period of torment followed by

a metamorphosis

On August 13, 1979, the trial court sentenced Mr. Giarratano

to death. JA 212-229. For the next four-and-one-half years, Mr.

Giarratano suffered immensely from the disorders which had been

identified by Dr. Showalter and Dr. Ryans in the trial court

proceedings. Periodically between August, 1979, and December,

1983, he continued to experience episodes of intense suicidal

depression. During those times he would sometimes decide to drop

further legal proceedings and to seek his execution. See

18

In such periods, he would also experienceAppendix to brief.7

excruciating psychotic processes similar to those he experienced

during the trial proceedings — sometimes auditory or visual

hallucinations, sometimes less distorted misperceptions of

reality. See JA 534-535 (letter from Dr. Miller Ryans, August

19, 1980); JA 537-542 (psychological report by Brad Fisher,

Ph.D., December, 1983).8 Typical of these experience is one Mr.

Giarratano reported in August, 1980 to one of his counsel: "'The

voices are laughing at me ... and I want to hurt myself to stop

it.... The medicine [800 mg. Thorazine daily] doesn't seem to be

doing any good....'" Appendix to brief, at 8 .

In the earlier part of this four year post-trial period, Mr.

Giarratano's day-to-day emotional life was still a tormented one,

often alternating between bizarre out-of-touch thought processes

7 In the appendix, we have excerpted a portion of Mr.

Giarratano's Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of

Petitioner's Claims Under Hearing XI of the Second Amended

Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus. See JA 5 (docket no. 34) .

This portion recounts in greater detail Mr. Giarratano's torment

during this period of time.

8 Dr.. Showalter had observed Mr. Giarratano's vulnerability

to psychotic processes during his evaluation between the guilt

and sentencing phases of the trial:

Mr. Giarratano reflected some distorted

perceptions of reality which suggestprepsychotic

processes. At times there seemed to be a fusion

of fantasy and reality. He seemed to be of

average intelligence, an impression confirmed by

the psychological tests. His thinking, however,

was unsophisticated and childlike, and he appeared

to have difficulty in abstracting.

JA/DA 296.

19

and jailhouse bravado. See JA 544-546 (affidavit of Michael

Hardy, July 7, 1988, recounting an interview with Mr. Giarratano

in May, 1980) . Toward the latter part of this period, he began

to be "able to reason in a more coherent and rational manner...."

JA 514 (letter from Dr. Showalter).

Since the fall of 1983, Mr. Giarratano has improved

enormously. The dynamics underlying his improvement have been

twofold: he has developed a therapeutic relationship with Marie

Deans (from the Virginia Coalition on Jails and Prisons), which

has begun to heal the deep, lifelong wounds of abuse and

deprivation inflicted upon him by his mother and stepfather, and

he has finally been freed from the residual effects of drug

abuse. JA 514-515 (letter from Dr. Showalter). Dr. Showalter

has been in a position to observe Mr. Giarratano's healing:

I most recently interviewed Mr. Giarratano at

the Mecklenburg Correctional Center on May

28, 1988. During this interview he presented

himself as a relaxed, fully rational and

psychologically well integrated man. I was

very impressed by the remarkable change that

had taken place in Mr. Giarratano's psycho

logical functioning during the five year

period since I last saw him in the fall of

1983. It is my opinion that during this five

year period his ongoing positive and

consistent relationships with individuals who

demonstrated a sincere care for him and his

abstinence from drugs and alcohol have

combined to produce a striking level of

psychological rehabilitation.

JA 514-515.

It is this "striking level of psychological rehabilitation"

which began to suggest to his counsel that he was far more

debilitated during trial proceedings than anyone had realrzed.

20

(vii) The first, limited recognition that Mr. Giarratano

was incompetent during his trial proceedings

When Mr. Giarratano gradually emerged from the shadows of

psychological disability in the fall of 1983, he began to

disclose facts about himself which he had never disclosed before.

These facts revealed in extraordinary detail the crippling

environment in which Mr. Giarratano was raised. While there were

hints in the sentencing phase of his trial that Mr. Giarratano

had a bad relationship with his mother, and that she might have

abused him, no evidence ever came close to revealing the

nightmarish truth which he was first able to reveal, beginning in

late 1983 and continuing through 1984. The District Court

summarized this evidence well in its order of June 25, 1986:

Joseph M. Giarratano wanted to die. His

first attempt at suicide came when he was

approximately 15 and followed the death of

his stepfather, Albert Parise. As noted

above, Giarratano was very close to his

stepfather during his early childhood and,

for reasons made clearer below, saw him as

the only positive adult figure in his life.

What was apparently unknown, to either judge

McNamara or Giarratano1s counsel, was that

this relationship changed in a most fundamen

tal respect when Giarratano was approximately

10 years old. Parise began sodomizing

Giarratano, with his mother's knowledge and

tacit approval according to the petitioner.

These rapes occurred repeated until the

stepfather died. As time went on, Parise

also forced Giarratano to engage in inter

course with his sister to satisfy his own

voyeuristic desires.

If Giarratano's relationship with his

stepfather was debasing, his relationship

with his mother was no better according to

him. When he was three or four years old,

she would leave him alone for days at a time

in their New York apartment. Drug dealers

21

and other felons were frequent visitors in

their home and a frequent source of

"amusement" for his mother and her "friends"

was to beat Giarratano with broom handles,

baseball bats and other weapons. His life

was threatened by both his mother and her

visitors. He was burned. He was shocked

with a cattle prod. He was locked in a tool

shed overnight. He was handcuffed to a fence

at night. Surrounded by this inhuman

environment, Giarratano latched on to drugs,

which were ever-present in the household, at

a very early age. His drug use was

encouraged by his mother.

During the sentencing hearings, Judge

McNamara learned that Giarratano had an

"extremely difficult" relationship with his

mother and that she had abused him. Nothing

was presented to indicate the extent of the

depravity Giarratano now claims he suffered

at the hands of his mother.

Giarratano's early reliance on drugs and the

hellish circumstances of his childhood took

their toll. He began hearing voices at a

very early age. At first, the voices

comforted him and kept him company.

Gradually, however, they became more

threatening. Ultimately, they mocked him,

urging him to murder his mother.

JA 359-360.

Dr. William Lee, the psychologist who participated in the

pretrial evaluation of Mr. Giarratano with Dr. Ryans at Central

oState Hospital, was so moved by the revelation of these new facts

that he expressed the view that "psychological factors" operative

during the trial proceedings had "the effect of precluding the

disclosure of childhood experiences and resultant emotional

reactions that would have been pivotal to understanding his

character formation or socialization." Memorandum of Points and

Authorities, supra (JA 5, docket No. 34), at 17. Dr. Lee also

22

concluded "with reasonable professional certainty," that these

same "psychological factors" also impaired Mr. Giarratano's

ability to consult with counsel: "indications are that his

responsiveness to advice of counsel and communication between

client and attorney would have been contaminated." Id. at 18.

Had Dr. Lee known of the "childhood experiences and resultant

emotional reactions" which Mr. Giarratano had been unable to

disclose during trial court proceedings, this knowledge

would have substantially altered formulations I

held at the time of his examination concerning

mitigation and future dangerousness.

Id., at 17.

These are the underlying revelations which led to the

assertion of the first claim that Mr. Giarratano was incompetent

during his trial. Because the revelations were limited in their

impact to sentencing issues, however, the claim -- raised under

heading XI in the Second Amended Petition for Writ of Habeas

Corpus, JA 257-258 — asserted only that Mr. Giarratano was

incompetent to participate in the sentencing phase of his trial.

(viii) The full recognition that Mr. Giarratano was

incompetent in relation to every aspect of his

trial proceedings

From 1984 through 1988, Mr. Giarratano's mental health

continued to improve. See JA 514-515 (letter of Dr. Showalter

noting Mr. Giarratano's marked improvement between late 1983 and

1988). With his improvement, he gained enough perspective to be

able to explore matters which he had not previously explored:

for the first time during this period, "in various discussions

23

with my lawyers and Marie Deans about the case, ... I began

remembering that I really did not know what occurred that night

in the apartment." JA 447 (affidavit of Mr. Giarratano, July 5,

1988). Mr. Giarratano explained how this process occurred:

In discussions about the various events I would

recall certain events that I had apparently

forgotten.... None of these facts caused me to

doubt that I had murdered Toni and Michelle. The

only significance they held for me was that I

remembered that I really did not know what

happened that night; and forced me to look closer

to distinguish what I actually remembered from

what I was told by the Norfolk police, what I

remembered from the trial, or had rationalized in

my own mind for myself.

JA 447-448.

This process of reflection led Mr. Giarratano to piece

together what he actually remembered from the night of February

4, 1979, and to be able to explain for the first time, how he

came to believe that he had murdered the Klines, how and Why he

confessed, and why he became so driven to kill himself or be

executed — and why he was unable to reveal any of this to his

lawyer or anyone else during his trial. What he has only

recently been able to piece together is the following:

(a) After consuming alcohol and injecting Dilaudid for

several hours on February 4, 1979, Mr. Giarratano remembers that

he went to the apartment of Barbara (Toni) and Michelle Kline to

pick up some of his personal belongings, and he "thinks" he was

let in by Michelle. JA 444.

(b) The "next actual memory" he had was of "waking up"

on the sofa in the apartment, finding Barbara Kline laying on the

24

floor in the bathroom in a large pool of blood, and then finding

Michelle laying naked across the bed in the bedroom across from

the bathroom, with her face "swollen . . . and discolored." Id.

(c) After discovering the bodies, he "kept asking

myself if I could have done this, but I just didn't know." He

then became confused and afraid, and all "I could think to do was

run." Id.

(d) He then remembered leaving the apartment, walking

around, and finally getting a taxi to the bus station in Norfolk,

where he purchased a ticket to Jacksonville (the town in which he

had grown up). Id.

(e) Just before or just after boarding the bus to

Jacksonville, Mr. Giarratano injected what remained of his

Dilaudid. JA 444-445. During the trip to Jacksonville, he

remembers

feeling crazy — like I was going out of my

mind. I kept telling myself that I could not

have killed them, but I really couldn't

convince myself that I hadn't. Nothing was

making sense to me.

Id.

(f) By the time he got to Jacksonville, he had become

convinced that he must have killed Barbara and Michelle, and that

is when he approached Deputy Wells. Id.

(g) On questioning by Deputy Wells and thereafter by

Deputies Mooneyham and Baxter, Mr. Giarratano was asked why he

had killed the women. He told the officers that he "really didn't

know why" but that he was certain that he had killed them. Id.

25

The officers kept pushing him for an explanation, however, so he

made up one. Id.

(h) Two days later while he was still in Jacksonville,

Mr. Giarratano was interviewed by Detectives Mears and Whitt from

the Norfolk Police Department. He confirmed for them his belief

that he had killed Barbara and Michelle Kline, but he changed his

account of the murders in response to information they provided

him. As Mr. Giarratano explained in his affidavit of July 5,

1988,

They asked me if I had killed Toni and

Michelle, and why. I told them that I had

killed Toni and Michelle, and apparently I

gave the[m] the same statement that I had

given to the Jacksonville officer. They told

me that it could not have happened like that.

After further questioning about the statement

I gave to the Jacksonville police, the

Norfolk detective told me that he believed me

when I said that I had murdered Toni and

Michelle, but . that he needed to know the

actual truth about what had happened. He

then informed me that Toni had been murdered

after Michelle, and that Michelle had been

raped; and that my statement to the Jackson

ville officer could not be right. I remember

telling the detective's [sic] then that I

really couldn't remember what had happened

because I was high, but that I had to have

murdered them because I was the only one at

the apartment. I told the officer that I

would tell him what happened, but that I

really could not remember. Eventually after

going back and forth for several minutes the

detective began asking me, 'could it have

happened like this, is this what happened?'

And, I would say 'yes'. The detective would

then ask me to put it into my own words, and

I would comply. After I would do that the

other detective would write down what I had

stated. He would repeat it back to me after

he was finished, and ask me if that was

correct. When the statement was finished

26

they asked if I would sign and, initial each

page, and I agreed.

JA 445-446.

(i) Even after his interrogation by the Norfolk

police, Mr. Giarratano still felt bewildered. "I did not want to

believe that I killed them, but I couldn't be sure that I didn't

— could not convince myself that I hadn't killed them." JA 446.

Any uncertainty was resolved shortly after he arrived at the

Norfolk city jail:

After I was processed and placed in the cell

I noticed a couple of spots that appeared to

be blood on my shoe. When I arrived at the

Norfolk jail I was still wearing the same

clothes from the night I left the apartment,

and until this time I had not noticed any

blood on my person or clothing. I immedi

ately contacted a jailer and requested to

speak with one of the detectives. Shortly

thereafter I turned my shoes over to them.

After seeing those specks of blood there

wasn't a doubt in my mind that I had murdered

Toni and .Michelle: even though I couldn't

remember actually killing them.

JA 446-447.

(j) With this discovery, Mr. Giarratano no longer felt

bewildered. Nagging doubt gave way to self-hatred and despair:

I was convinced that I was evil and that I

had to be punished for what I did. I

couldn't sleep, I couldn't keep any food

down, I knew I was sick, and all I wanted to

do was die. I attempted to hang myself, but

failed. Soon after that I was transferred to

Central State Hospital. It is hard for me to

recall all that occurred during this period.

Looking back to that time is confusing

because the only thing that seemed real to me

was that I had murdered Toni and Michelle. I

was evil and had to be punished for what I

did.

27

JA 447.

(ix) The fundamental absence of evidence establishing that

Mr. Giarratano is guilty or that he poses a threat of

danaerousness in the future

These revelations by Mr. Giarratano have provided

substantial reason to re-examine the Commonwealth's evidence

against him in both phases of his trial.

As noted, supra at 14-15, the guilt phase evidence consisted

of Mr. Giarratano's confessions and various pieces of physical

evidence, which purported to corroborate the confessions. When

Mr. Giarratano's confessions and the physical evidence are

examined closely, as Mr. Giarratano urged the District Court to

do, it is plain that there is no corroboration of his confessions

by the physical evidence, and there is pervasive internal

inconsistency within his confessions. The result is that there

is no reliable evidence of Mr. Giarratano's guilt. He could have

been convicted only if one presumed his confessions' to be

accurate.

There is an assumption that a detailed confession can be

given only by one who knows the details of the crime. Thus, when

sufficient details are provided in a confession, we have a sense

that the confession is self-corroborative. This can be so,

however, only if the confession is internally consistent and if

the confession is not contradicted by the crime scene evidence.

These indicia are strikingly absent in Mr. Giarratano's confes

sions, as shown by the facts proffered to the District Court.

28

(a) There is an absence of fundamental internal

consistency in Mr. Giarratano's confessions: He ascribes to

contradictory versions of the basic facts in his confessions. He

says that he killed Barbara Kline in an argument over money, then

killed Michelle because she was screaming. In one version

setting forth this sequence of events, he says he raped Michelle

after killing Barbara; in the other, he says he only killed

Michelle and did not rape her. In a very different version of

events, he says that he first killed Michelle after raping her,

then killed Barbara after she discovered him in the apartment.

Inconsistencies like this can sometimes be reconciled because one

version seems "worse" than the other, and the confessor might be

seen as trying to mitigate his culpability. However, an equally

plausible reason can be that the person suffers from mental or

physical disabilities that either prevent him from remembering

events at all or cause him to fill in memory gaps with various

plausible explanations. Mr. Giarratano and the experts who have

evaluated him over the years — including, significantly, Dr.

Ryans from Central State Hospital — provide substantial factual

support for this explanation. Indeed, Dr. Ryans testified at

trial that the inconsistencies in Mr. Giarratano's confessions

were due to "Korsakoff's syndrome," an organic brain disorder

caused by Mr. Giarratano's ingestion of alcohol, cocaine, and

Dilaudid over long periods of time, in which the person suffers

"loss of recent memory" and "confabulate[s]," or "make[s] things

up," to fill in the memory gaps. JA/DA 98-99.

29

(b) The other reason proffered to the District Court

for finding that the confessions are of very questionable

accuracy is that they are contradicted in substantial ways by the

crime scene evidence. Thus, there is a high probability that

Michelle Kline was not strangled with the use of hands, as Mr.

Giarratano said she was, but with the use of a "chokehold" or a

"ligature". See Motion for Relief from Judgment and Memorandum

in Support Thereof, at 9-10 and Exhibits 6-8 (filed in the

District Court on April 7, 1989).9 There is evidence that

Michelle was dragged to the bedroom, that she did not go

voluntarily as Mr. Giarratano said. See JA/DA 72. There is

evidence that Michelle had her underpants and pants on at the

moment she died — not, as Mr. Giarratano said, that her pants

were off prior to the rape and murder. See JA 472-473 (referring

to the odor of urine in Michelle's clothing). There is evidence

that Barbara Kline was killed from behind by someone hiding in

the bathroom, see Rule 60 motion, at 9 and Exhibits 3 and 4, and

that the killer likely used his right hand, id.. Exhibit 3. Mr.

9 Mr. Giarratano filed this motion under Rule 60(b) of the

Rules of Civil Procedure on the basis of newly-discovered facts.

He realizes that it is not a part of the appellate record herein.

However, he believes that the facts contained in the 60(b) motion

are highly material to the issues before this Court on appeal.

For this reason, he has filed a motion in this Court asking that

the appeal be continued until the District Court has resolved the

60(b) motion. A copy of the 60(b) motion has been included with

the motion for continuance. At the time this brief was due,

neither motion had been decided. Because the 60(b) motion is

properly before the District Court, and the facts contained

therein are material to this- Court's resolution of Mr.

Giarratano's appeal, however, reference will be made herein to

the facts alleged in the 60(b) motion.

30

Giarratano said that he was waiting for Barbara "by the wall in

the living room" and attacked her from there, but in fact she was

killed in the bathroom. JA 459. Moreover, Mr. Giarratano is

left-handed and has neurological deficits which diminish his

ability to use his right arm and hand. JA 523. Finally, Mr.

Giarratano said that he locked the exterior door to the apartment

when he left (after the stabbing of Barbara) , but it was found

unlocked. Rule 60 motion, at 11.

The remaining physical evidence relied on by the state does

not establish in any way, certainly not beyond a reasonable

doubt, that Mr. Giarratano was the killer-rapist:

(a) One of twenty-one hairs recovered from or near

Michelle's body for analysis was found to be consistent with, not

identical to, Mr. Giarratano1s pubic hair. JA/DA 82-83 and Trial

Ex. C-23 (admitted at 83) . No pubic hair sample was obtained

from Michelle Kline or Barbara Kline. JA 464. Thus, no

comparison of the unknown hairs to their pubic hairs could be

made. Mr. Giarratano had lived in the apartment, so even if this

was his hair, the presence of it does not suggest that he was

Michelle's assailant. JA 471.

(b) The presence of type 0 human blood on one of Mr.

Giarratano's boots — which happened to match Michelle's blood in

this respect — does not suggest that Mr. Giarratano was her or

her mother's assailant. Rule 60 motion, at 4-8. There was no

blood on Mr. Giarratano' s clothing or property when he was

arrested in Jacksonville. Rule 60 motion, Exhibit 5. There was

31

no evidence that Michelle, whose blood was type 0, had bled

sufficiently from her vaginal lacerations to have deposited blood

anywhere outside her body. Rule 60 motion, at 6 n. 2. Barbara

Kline's blood type was never determined. Id. at 5. Even if it

had been type 0, however, the nature of Barbara Kline's wounds

and the amount of bleeding which followed would have left far

more blood on Mr. Giarratano's boot than was found by the State's

serologist. Rule 60 motion, at 5-8. Thus, it is unreasonable to

believe that the blood on the boot was related to the crime

scene.

(c) The presence of ''intact spermatozoa" in Michelle

Kline's vaginal tract establishes at most that she had sexual

intercourse within twenty-four hours of her death, and the

finding of vaginal lacerations establishes at most that this

intercourse was rape. Neither of these facts in any way

identifies Mr. Giarratano as the rapist. See JA 472-473.

Finally, in support of its burden to show that death was the

proper sentence, the state relied upon the evidence introduced in

support of its case on guilt or innocence, the testimony of Dr.

Ryans, and upon facts developed in a presentence investigation.

See JA/DA 138-151, 152-167, 278-287. The presentence

investigation relied heavily upon information provided by Mr.

Giarratano's mother, Carol Parise, or at her request, by her

friends and associates. The picture created by Ms. Parise was

that her son was a violent young man, who posed a danger to those

around him and who lied to counselors and mental health

32

professionals regarding his family situation during his childhood

and teenage years. See Rule 60 motion, at 15-19. Thus, the

presentence report provided powerful corroboration for Dr. Ryans'

views that Mr. Giarratano was a dangerous person. Post-trial

investigation of Mr. Giarratano's history and of Ms. Parise and

her associates has revealed that this picture of Mr. Giarratano

was a manifestly false impression, and that Ms. Parise

intentionally fabricated the factual basis for much of the

presentence report. Id. Mr. Giarratano was neither violent nor

a liar. Id.

(x) Mr. Giarratano's inability to disclose the information

that was necessary to construct his defense was the

product of mental and physical disabilities

Mr. Giarratano's inability to disclose necessary information

was not a "chosen" incapacity. It was not a form of repentance

by one who, knowing he "has committed a heinous crime may be

truly repentant and feel that the only absolution would be to

submit himself to, and accept, the maximum punishment." JA 680

(District Court's order of December 6, 1988). Mr. Giarratano's

certainty, despite his absence of knowledge, that he committed

the crime, his unrelenting desire to be punished, and his failure

to reveal his thought processes about these matters to anyone,

were a product of disability, not rationality.

Mr. Giarratano was suffering from the combined effects of

three crippling disabilities. Dr. Jack Mendelson, one of the

nation's leading experts on the psychiatric consequences of drug

abuse, has explained that Mr. Giarratano's many years of drug

33

abuse likely produced a chronic psychotic illness, in which he

periodically suffered delusions and hallucinations. JA 421-

422. Dr. Robert Showalter has further explained that Mr.

Giarratano's drug-created vulnerability to psychosis was enhanced

by the schizoaffective disorder which he suffered, which also

periodically produced delusions and hallucinations. JA 423-424.

In addition, the schizoaffective disorder caused him to suffer

profound periods of depression, characterized by feelings of

worthlessness, self-hatred, and suicidal thoughts and behavior.

Id. Finally, as a University of Virginia neuropsychologist, Dr.

Jeffrey Barth, has found, Mr. Giarratano suffered organic brain

damage at the time of his arrest and trial, and this damage

impaired "his ability to grasp the essential nature of new and

unfamiliar problems and situations." JA 518. When thrust into

such situations, "[h]is ability to engage in abstract thinking, 10

10 According to the American Psychiatric Association's

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3d ed.,

Rev., 1987),

[a delusion is a] false personal belief

based on incorrect inference about external

reality and firmly sustained in spite of what

almost everyone else believes and in spite of

what constitutes incontrovertible and obvious

proof or evidence to the contrary. The

belief is not one ordinarily accepted by

other members of the person's culture or

subculture (i.e., it is not an article of

religious faith). . . . [It] should be

distinguished from a hallucination, which is

a false sensory perception (although a

hallucination may give rise to the delusion

that the perception is true).

Id. at 395.

34

to be flexible in his thinking, and to think efficiently is

significantly impaired." Id.

Together, these disabilities explain why Mr. Giarratano came

to believe that he killed Barbara and Michelle Kline. Most

people who would find themselves in Mr. Giarratano's circum

stances when he regained consciousness in the Klines' apartment

would not come to believe that they had killed the Klines. Logic

would tell them that someone else must have committed the crimes

while they were passed out. However, Mr. Giarratano's dis

abilities led him to the opposite conclusion. Subject to

delusional thinking — to developing false impressions and

holding fast to false ideas about reality — and to thinking the

worst about himself, Mr. Giarratano was more likely to infer, as

he did, that he was the killer. JA 515 (letter of Dr.

Showalter). With only a limited ability "to grasp the essential

nature of new and unfamiliar problems and situations," JA 518

(affidavit of Dr. Barth), he was peculiarly vulnerable to his

delusional, self-deprecating thought processes in these

circumstances. He did not have the ability to step back,

consider the possibility that someone else may have killed the

Klines, and give at least as much credence to that theory as to

the theory that he was the killer. Id.

Once he came to this conclusion, his vulnerability to

feelings of worthlessness and self-hatred impelled him to commit

suicide, either by his own hand or through the processes of the

criminal justice system. With significant impairment in his

35

ability to engage in abstract thinking or to be flexible in his

thinking, JA 518, Mr. Giarratano could not distance himself

enough from his suicidal compulsion to be able to tell anyone why

he was so driven to self-destruction. Id.

In sum, as Dr. Showalter has explained:

Contrasting his cognitive and affective

processes as assessed in May 1988 with the

observation of the level of compromise of

these functions noted in June 1979 strongly

suggests that in the spring of 1979 Mr.

Giarratano's capacity for rational decision

making, as it related to adequately assisting

counsel in developing his defense, may have

fallen below the required statutory standard

necessary to establish, competency to stand

trial. Specifically, Mr. Giarratano believed

that he had killed the victims as accused and

both consciously and unconsciously used this

belief to further activate and intensify his

suicidal drives. Inviting execution by the

state, through administration of the death

penalty, therefore became a very appealing

way to end for Mr. Giarratano in 1979 and

several years thereafter, a life of isolation

and misery. These ideas were very strongly

influenced by the symptoms Mr. Giarratano was

experiencing in 1979 as a result of the

symptoms of the schizoaffective process,

which in turn was augmented by a combination

of persisting toxic sequela related to his

long drug abuse history and the emerging

symptoms of an abstinence syndrome.

JA 515.

B. Facts Underlying the Estelle v. Smith Claim

As noted, in response to Mr. Giarratano's attempted suicide

in the Norfolk jail on February 16, 1979, the trial court ordered

that Mr. Giarratano be evaluated at Central State Hospital. At

the same time, the court appointed Albert Alberi to represent Mr.

Giarratano on the charges arising from the Kline homicides. JA

36

146. According to his testimony during the state habeas

proceeding, Alberi played no role whatsoever in his client's

transfer to Central State. Id.

Alberi testified that when he was notified of his

appointment to represent Mr. Giarratano he was simultaneously

told that his client had already been "dispatched to Central

State Hospital because he had attempted suicide." 'Id. Alberi