Monroe v. City of Jackson, TN Board of Commissioners Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

April 25, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Monroe v. City of Jackson, TN Board of Commissioners Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1977. 70b1c717-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f6763e45-a6a2-4dd0-b317-18ae7f05936d/monroe-v-city-of-jackson-tn-board-of-commissioners-brief-of-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

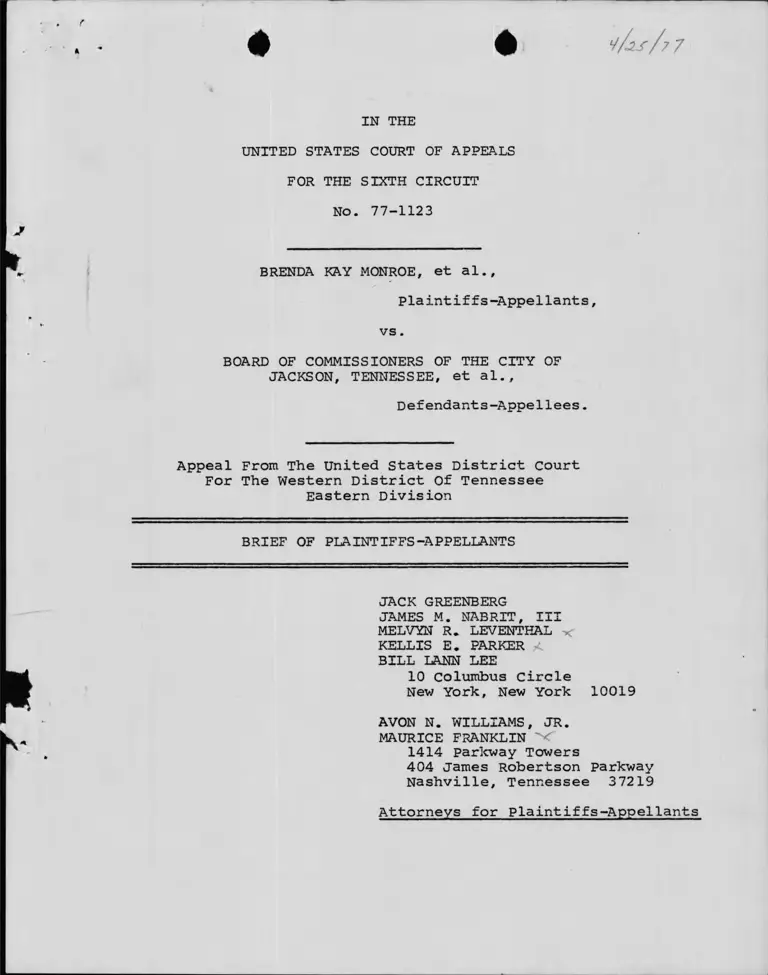

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 77-1123

BRENDA KAY MONROE, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS OF THE CITY OF

JACKSON, TENNESSEE, et al..

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Western District Of Tennessee

Eastern Division

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

KELLIS E. PARKER

BILL LANN LEE

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

MAURICE FRANKLIN X'

1414 Parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Table of Contents

Page

Table of Contents .............................. i

Table of Cases ..................... ii

Statement of Questions Presented ............. 1

Statutory Provisions Involved ........ 2

Statement of Case .................................. 3

Statement of Facts ................................. 9

ARGUMENT

Introduction ...................................... 11

Summary of Argument ........................... 14

I. The Lower Court Misapplied Proper Legal

Standards In Determining Attorneys' Fees

For Legal Representation Since July 1,

1972......................................... 15

A. Prevailing Upon Every Issue ..... 17

B. Application of Factors ............... 21

II. The Lower Court Erred In Denying Attorneys'

Fees For Legal Representation From January

1971 To July 1, 1972 24

III. The Lower Court Erred In Denying Attorneys'

Fees For Legal Representation From January

8, 1963 to July 1, 1972 27

Conclusion ...................................... 32

Appendix .......................................... a -1

Certificate of Service ................. ....... .

• #

Table of Cases

Ace Heating & Plumbing Co., Inc. v. Crane, 453 F.2d

30 (3rd Cir. 1971) ................................. 20

Alyeska Pipeline Serv. v. Wilderness Society,

421 U.S. 240 (1975) ................................ 28,2

Armstrong v. Bd. of Education of City of Birmingham, 30

C.A. 9678 (N.D. Ala. Sept. 14, 1976...... ..........

Aspira of New York, Inc. v. Board of Education of

New York, 394 F.Supp. 1161 (S.D. N.Y. 1975) ...... 20

Bell v. School Bd. of Powhatan Cty., 321 F.2d

494 (4th Cir. 1963) ................................ 12

Bradley v. Richmond School Board, 416 U.S. 696

(1974) 21,17,14,13

29,26,25,24

Brewer v. School Board of the City of Norfolk,

500 F. 2d 1129 (4th Cir. 1974) ...................... 29,25

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)..... 13

Davis v. County of Los Angeles, 8 EPD f4444

(C.D. Cal. 1974) 18,24

Davis v. Pontiac School Dist., 443 F.2d 255

(6th Cir. 1971) 15

F.D. Rich Co., Inc. v. Industrial Lumber Co.,

417 U.S. 116 (1974) 12

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 488 F.2d

714 (5th Cir. 1974) ................................ 24,22, 17

Lafferty v. Humphrey, 248 F.2d 82 (D.C. Cir. 1957)

cert.denied, 355 U.S. 869 (1957) ................. 20

Maddox v. Gulf States Paper Corp., Civil No. 69-M-628

(N.D. Ala. October 18, 1974) 20

Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375 (1970).. 17

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the City of

Jackson, 453 F.2d 259 (6th Cir. 1972) ............ 16,8,4

Monroe v. Bd. of Comm. City of Jackson, 505

F. 2d at 109 21,11,3

Monroe v. County Board of Education of Madison County,

Sixth Cir. No. 76-2389, appeal pending ............ 4

- ii -

Page

Northcross v. Board of Education, 412 U.S. 427

(1973) .......................................... 23,14,13

Norwood v. Harrison, 410 F.Supp. 133 (N.D. Miss.

1976) 25

Palmer v. Rogers, 10 EPD ^[10,499 (D.D.C. 1975) .... 17

Ramey v. The Cincinnati Enquirer, Inc., 508

F. 2d 1188 (6th Cir. 1974) ....................... 20

Robinson v. Shelby County Board of Education,

442 F. 2d 255 (6th Cir. 1971) ................... 15

Sprague v. Ticonic Nat'1 Bank, 307 U.S. (1935) ... 25,12

Stanford Daily v. Zurcher, 64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D.

Cal. 1974) 18,19,24

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) 19,15

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

66 F.R.D. 483 (W.D. N.C. 1975) ................. 24,19, 17

Torres v. Sachs, 538 F.2d 10 (2d Cir. 1976) ..... 20

United States v. Texas, 495 F.2d 1250 (5th Cir. 1974) 28

Wade v. Mississippi Cooperative Extension Serv.,

378 F.Supp. 1251 (N.D. Miss. 1975) ............ 19

Statutes

20 U.S.C. § 1617 ................................ in passim

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ..................................... 3

42 U.S.C. § 1982 3

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ............................. ...... 3

42 U.S.C. § 1985 3

42 U.S.C. § 1986 3

42 U.S.C. § 1988 ........................... . in passim

x n -

Page

Other Authorities

Hearings Before The Senate Selection Committee

on Equal Educational Opportunity, 91st Cong.

Part 3B ......................................... 12

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558, The Civil Rights Attorney's

Fees Awards Act of 1976, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1976) 16,14,13

25,23

S. Rep. No. 74-1011, 1976 Attorneys' Fees Awards

Act, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976) 15,14,15

24,23,24

Subcomm. on Constitutional Rights of the

S. Comm, on the Judiciary, Civil Rights Attorneys'

Awards Act of 1976, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (Comm.

Print 1976) 25'13

114 Cong. Rec...................................... 13

117 Cong. Rec...................................... 13

122 Cong. Rec....................................... 29

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 77-1123

BRENDA KAY MONROE, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS OF THE CITY OF

JACKSON, TENNESSEE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Western District Of Tennessee

Eastern Division

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Statement Of Questions Presented

In a pending school desegregation action in which

plaintiffs, as prevailing party, seek an award of attorney's

fees pursuant to § 718 of the Emergency School Aid Act of

1972, 20 U.S.C. § 1617, and the Civil Rights Attorneys Fees

Award Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. § 1988:

1. Whether the lower court erred in applying the stand

ards of the Emergency School Aid Act of 1972 and the

Civil Rights Attorneys Fees Award Act of 1976 to determine

the attorney's fees for legal representation since July 1,

1972, the effective date of the School Aid Act?

2. Whether the lower court erred in denying any

attorney's fees for legal representation prior to July 1, 1972

pursuant to the Emergency School Aid Act of 1972 and the

Civil Rights Attorneys Fees Award Act of 1976

a) For the period from January 6, 1971 to

July 1, 1972 for which no prior attorney's fees

was determined?

b) For the period prior to January 6, 1971

for which attorney's fees under the "obdurate

obstinacy" standard had been previously determined?

Statutory Provisions Involved

Section 718 of the Emergency School Aid Act of 1972,

20 U.S.C. § 1617, provides:

"Upon the entry of a final order by a court of

the United States against a local educational

agency, a State (or any agency thereof), or the

United States (or any agency thereof), for failure

to comply with any provision of this chapter or

for discrimination on the basis of race, color, or

national origin in violation of title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, or the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States as

they pertain to elementary and secondary education,

the court, in its discretion upon a finding that

the proceedings were necessary to bring about com

pliance, may allow the prevailing party other than

the United States, a reasonable attorney's fee as

part of the costs."

2

The Civil Rights Attorneys Fees Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1988, provides:

"In any action or proceeding to enforce a

provision of sections 1977, 1978, 1979, 1980

and 1981 of the Revised Statutes, 1/ title IX of

Public Law 92-318, or in any civil action pro

ceeding, by or on behalf of the United States

of America, to enforce or charging a violation

of, a provision of the United States Internal

Revenue Code, or title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, the court, in its discretion, may

allow the previaling party, other than the

United States, a reasonable attorney's fee as

part of the costs. "

Statement Of The Case

Appeal is sought from the order on attorney fees

(J.A. 283) and judgment on court decision (J.A. 296) entered

by U. S. District Court Judge Harry W. Wellford, Western

District of Tennessee, Eastern Division, on, respectively,

November 18th and November 29th, 1976. This is the second

appeal from the lower court's determination of attorney's

fees originally sought in June 1973. in 1974, the issue was

whether the $1,500 fees awarded bore any relation either to

the time and effort of counsel or to any other relevant

considerations which ought to govern a district court's

execuse of discretion in setting the amount where district

court failed to articulate the basis for its award or to

permit the parties to introduce evidence, Monroe v. Board

of commissioners of city of Jackson, 505 F.2d 105, 106

(6th cir. 1974). This Court held that, " [b]ecause our

l/ Presently codified as 42 U.S.C. §§ 1983, 1985-1986.

3

review is dependent upon some sort of record of the basis

for the decision below, we vacate the judgment insofar as

it relates to the attorneys' fee and remand the cause to

the district court for findings of fact and conclusions of

law as to the amount of any attorneys' fees awarded under

the standards of Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond,

416 U. S. 696 (1974)." 505 F.2d at 109. The basic issue

now is whether the district court correctly followed this

Court's mandate in accordance with prevailing law.

All told, this is the sixth time that this action has

come before this court. The action was filed on January 8,

1963 originally as a single school case against both the

Board of Commissioners of the City of Jackson and the

Madison County Board of Education to disestablish the dual

system of public education, and has been vigorously litigated

2/

ever since. Because of the limited nature of the appeal,

we do not state the detailed history of the litigation which

is summarized in Monroe v. Board of commissioners of the

City of Jackson, Tennessee, 453 F.2d 259 (6th Cir. 1972)

and 505 F.2d 109 (6th Cir. 1974).

The January 1963 complaint concludes, "[p]laintiffs

further pray that the Court will allow them their costs

2/ The two cases have been separately litigated. Monroe

v. County Board of Education of Madison county, Sixth

Circuit No. 76-2389, also is presently pending on appeal on

questions arising from separate attorneys fees award

proceedings.

- 4

herein and such further, other or additional relief as may

appear to the court to be equitable and just," Complaint at

p. 18. In a motion for further relief and to add parties

as additional and/or intervening plaintiffs filed September

4, 1964, plaintiffs requested:

"That the Court award reasonable fees to

plaintiffs’ attorneys for their services rendered

to them, including the intervening and/or additional

plaintiffs, in this cause, and allow plaintiffs

their reasonable costs and grant such further,

other, additional or alternative relief as may

appear to the court to be equitable and just."

Motion For Further Relief at p. 13. Every motion filed

bY plaintiffs to date contains a similar express request

for an award of attorney’s fees. With respect to the 1964

request, the lower court granted an interim award of $1,000

"for the handling of that aspect of the litigation pertaining

to the application of the intervening plaintiffs in the

summer of 1964 to transfer to schools outside of their zones

and the defendants' denial of said application in clear

violation of the constitutional rights of these plaintiffs"

(J.A. 10).

On January 6, 1971, plaintiffs "move [d] the Court to

allow them attorneys fees for their attorneys" for the then

entire period of the litigation (J.A. 11). The accompanying

affidavit of counsel lists in detail the hours worked

with respect to proceedings (j .a . 13). The district court

awarded only fees from the period from May 1968 under the

non-statutory "obdurate obstinacy" exception to the American

rule (J.A. 33).

"The conduct of the defendant, Board of Com

missioners of the City of Jackson, Tennessee, in

s^snce to the city School System after the

decision of the Supreme Court of the united States

this case in May 1968, in failing and refusing

to adopt and propose a plan for meaningful and

prompt desegregation of the City School System, was

unreasonable and obdurate with regard to its

affirmative duty, and said counsel for the plaintiffs

are entitled to a reasonable attorney fee for the

period commencing after the remand of the case from

the Supreme Court in 1968 and continuing through

aPPeal of this Court's ruling by the defendant,

Board of Commissioners of the City phase of the case

to the court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit,

decided June 19, 1970. The sum of Five Thousand

Dollars ($5000.00) is set as this fee and said defend

ant, Board of Commissioners, will pay said sum

forthwith to said counsel for plaintiffs as an

afforney fee, and not as part of the costs, covering

said period of time in the city phase of the case

only. The Court will not attempt to allocate

proportions of said fee as between said two counsel

for plaintiffs and the entire amount thereof will

be paid to Avon N. Williams, Jr., Esquire, for

appropriate allocation between them according to their agreement and consent."

(J.A. 36). The court added:

"It appearing to the court that the amount of the

costs to be paid by the defendants is disputed and has

never been concluded, the undersigned Judge of the

Court hereby reserves _ for his individual determination

all questions pertaining to payment of court costs

to ̂ and including the date of this order upon appro

priate application to the Clerk and the Court."

Id. To date the question of costs is still pending.

The district court had previously explained its reasoning

at the conclusion of a hearing January 14, 1971 (J.A. 25).

6

"The Court's ruling is going to be based upon

the Court's conception of the law that the fee in

a case of this sort is not a fee as a matter of

right for all services rendered from the time of

the inception of the case. The court doesn't

understand that to be the law.

"Of course, there is a strong and convincing

appeal to the moral right for a fee. When we

look back at the history of this case, we see a

sight that isn't pleasant for the white race, of

which I am a member, of course. It is not a

panorama of something of which we should be proud.

It took courage to file this suit, and it took

courage for people like Brenda K. Monroe to want

to break the system that was so basically unfair

and was ingrained into the school systems not

only in Jackson and Madison County but other places.

"Based on objective fairness in the community

one hundred thousand dollars would be a modest

fee, but we cant take that into consideration in

awarding a fee, nor those matters included in the

remarks by Mr. Ballard. I am sure he has been

severely criticized and it did come at some cost

to his position in the community.

"I don't conceive the law to be for this court

to try to penalize the defendant because it has

undertaken to follow its concept of the law from

the beginning. The law is slow — slower than it

should have been. When you stop and look back

on this era of history the fact that 'due

deliberate speed' or 'deliberate speed' was

interpreted to mean fifteen years doesn't look

very pretty. The Court doesn't believe that it

should use the awarding of a fee as a penalty

for the defendants because they haven't done what

the Constitution requires.

"The Court has also taken into consideration

that Judge Brown has considered the matter of a

fee in earlier proceedings.

"It is my conclusion that a fee should be awarded

in this case based upon the phase of the case that

commenced after the remand of the Supreme Court."

(J.A. 27-28). Plaintiffs appealed the question whether

7

"the award should not have been limited as it was to the

period of the time from the remand from the Supreme Court

to the time of the issuance of this Court's most recent

ruling in June 1970. " Monroe v. Board of commissioners

of City of Jackson, supra, 453 F.2d at 263. This Court

affirmed that, "the determination as to the lack of

unreasonably obstinacy as to this earlier period to have

been proper," id. A subsequent rehearing petition was

3/ ~

denied.

Thereafter, on June 5, 1973, plaintiffs moved for an

award of counsel fee for the entire litigation pursuant

to § 718 of the Emergency School Aid Act of 1972, 20 U.S.C.

§ 1617, supra, which went into effect July 2, 1972 (J.A. 39).

The district court awarded an attorney's fee of $1,500 "in

the exercise of equitable discretion" (J.A. 71, 73). As

noted above, this court vacated the judgment and remanded

for "findings of fact and conclusions of law as to the

amount of any attorney's fee awarded," 505 F.2d at 109.

On remand, plaintiffs renewed their request for fees for the

entire period and for the intervening additional time

(J.A. 74 et_ seq. and 119 et seq.) . An evidentiary hearing

was held April 8, 1976 (J.A. 141) and the court issued its

3/ Defendant school board unsuccessfully appealed on the

merits. its petition for rehearing and latter petition for

a writ of certiorari also were denied (J.A. 38).

order on attorney fees November 18th (J.A. 283) and

judgment on court decision November 29th (J.A. 296). In

the interim, Congress enacted and the President signed the

Civil Rights Attorneys' Fees Award Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1988, which went into effect October 19th.

The lower court's order, inter alia, (a) denied any

award for the period before July 1, 1972, including both

the period from 1963 to January 1971 which had been earlier

determined under the "obdurate obstinacy" standard, and the

interim period for which prior determination had been made;

and (b) conferred an award of $5,000 for plaintiffs' legal

representation since July 1, 1972. A timely notice of

appeal was filed (J.A. 297).

1/Statement of Facts

Counsel for plaintiffs have a distinguished record as

practicing lawyers, having been members of the Bar of

Tennessee for a combined total of 71 years. Together, they

spent an approximate total of 672 hours on the case from

January 8, 1963 to April 8, 1976 of which, at least 40

4/ The facts of this case are those presented by plaintiffs

at the hearing on April 8, 1976 (J.A. 141) and in the

affidavit of plaintiffs' counsel (J.A. 120). Although the

three witnesses who testified at the trial were cross-

examined by defendants, the defendants made no affirmative

presentation of facts.

hours were in court. Plaintiffs have not received reasonable

compensation for services of their counsel.

10

ARGUMENT

Introduction

In the 1974 opinion, this Court stated the rule that,

"ftjhere is a strong policy in favor of awards of attorneys'

fees in school desegregation cases, and plaintiffs ''should

ordinarily recover an attorney's fee unless special circum

stances would render such an award unjust.'' Northcross v.

Memphis Board of Education, 412 U.S. 427, 428 . . . (1972),

quoting Newman v. piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S.

400, 402 . . . (1968). Although it is within the district

court's discretion to determine whether or not to award

attorneys' fees, this court may review the reasonableness of

any award." Monroe v. Board of commissioners of city of

Jackson, supra, 505 F.2d at 109. Upon remand, the lower

court merely reinstated the $1,500 award for fees through

1973, reversed by this Court, as "fair and reasonable" (with

only an increase of $1,000 "[s]ince there has been a delay

in the payment"), (J.A. 294), and allowed an additional

$2,500 amount for legal services since 1973 under a narrow

and erroneous legal standard, id. The district court also

refused to consider any award of fees for legal representation

prior to July 1, 1972, the effective date of the Educational

Amendments. The latter consists of two periods: the first

from January 6, 1971 to July 1, 1972 for which no prior

11

j

award was ever sought or determined; the second from the

filing of the lawsuit in 1963 to January 6, 1971 for which

a prior award under the "obdurate obstinacy" exception to the

American rule was sought and determined.

] Plaintiffs-appellants Brenda K. Monroe, et al. submit

i -

that the lower court erred in its determination of attorney's

j . fees for each period, in each instance misapplying legal

-i

standards of § 718 of the Emergency School Aid Act of 1972,

20 U.S.C. § 1617 (hereinafter "1972 Educational Amendments")

and the Civil Rights Attorneys Fees Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1988 (hereinafter "1976 Attorneys Fee Act"). Initially,

i

however, we note that the two statutory provisions are an

j

intentional Congressional departure from the traditional

American rule that counsel fees are not included as part of the

recoverable costs of litigation. See, e.g., Alyeska Pipeline

Serv. v. Wilderness Soc.. 421 U.S. 240 (1975); Sprague v. Ticonic

Nat11 Bank, 307 U.S. 161 (1939); F. D. Rich Co., Inc, v. Industrial

Lumber Co., 417 U.S. 116 (1974). The statutes were intended

to enlarge the circumstances in which federal district courts

would exercise their inherent equitable power to award fees,

Sprague, supra, 307 U.S. at 164, beyond the traditional

formulation requiring "obdurate and obstinate" conduct by

school boards, e.g.. Bell v. School Bd. of Powhatan county,

321 F.2d 494 (4th Cir. 1963). For 1972 Educational Amendments,

see Hearings Before The Senate Selection committee on Equal

12

Educational Opportunity. 91st Cong., Part 3B, pp. 1516-34;

114 Cong. Rec. 10760-64, 1139-45 (Sen. Mondale); 117 Cong.

Rec. 11343, 11521 (Sen. Cook). For 1976 Attorneys' Fees

Act, see S. Rep. No. 74-1011, 1976 Attorneys' Fees Awards Act,

94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976), pp. 2-4; H. R. Rep. No. 94-1558,

The Civil Rights Attorney's Fees Awards Act of 1976, 94th Cong.,

5/2d Sess. (1976), pp. 2-3. Indeed, a specific purpose of the

broader 1976 Attorney's Fees Act was to redress the irony

that "in the landmark Brown [v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

483 (1954)] case challenging school segregation, the plaintiffs

could not recover their attorney's fees, despite the signifi

cance of the ruling to eliminate officially imposed segre-

Vgation."

"The plaintiffs in school cases are 'private attorneys

general' vindicating national policy" who should "'ordinarily

recover an attorney's fee unless special circumstances would

render such an award unjust,'" Northcross v. Board of

Education. 412 U.S. 427, 428 (1973) (construing 1972 Educa-

5/ The committee reports, debates and other legislative

history of the 1976 Attorney's Fees Act are set forth in one

volume in Subcomm. on Constitutional Rights of the S. Comm,

on the Judiciary, Civil Rights Attorney's Fees Awards

Act of 1976, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (Comm. Print 1976).

6/ H. R. Rep. No. 94-1558, supra, at pp. 4-5.

Z./ Compare Bradley v. Richmond School Board. 416 U.S. 696,

719 n. 27 (1974) ("It is particularly in the area of desegre

gation that this Court. . . recognized that, by their suit,

plaintiffs vindicated a national policy of high priority.")

13

tional Amendments). Furthermore in Bradley v. Richmond

School Board, 416 U. S. 696, 710 (1974), the Court decided

that in a pending case '"§ 718 authorizes an award of

attorneys' fees insofar as those expenses were incurred

fi/prior to the date that that section came into effect.1"

Summary of Argument

First, the lower court correctly held that plaintiffs

were "prevailing party" in determining the attorney's fees

awarded for the period since 1972. However, the district

court incorrectly applied appropriate standards to determine

the amount of the award contrary to the statutes and appli

cable caselaw. Second, the per se denial of an award of

fees for legal work prior to the effective date of the 1972

Educational Amendments in a pending case for which no prior

determination had ever been made was in express violation

of the statutes as authoritatively construed in Bradley v .

Richmond School Board, supra. Third, the denial of statutory

attorney's fees for legal services prior to January 1971 "as

part of costs" is not precluded by a prior determination under

the non-statutory "obdurate obstinacy" exception to the

American rule.

8/ Northcross and Bradley are incorporated by reference

m the legislative history of the 1976 Attorneys' Fees Act,

see H. R. Rep. No. 94-1558, supra; S. Rep. No. 1011, supra.

14

I.

THE LOWER COURT MISAPPLIED PROPER LEGAL

STANDARDS IN DETERMINING ATTORNEYS FEES

FOR LEGAL REPRESENTATION SINCE JULY 1,

1972._____________________________________

The district court held that, " [p]laintiffs are . . .

entitled to an award based upon attorney fees and expenses

incurred after July 1, 1972, because at least to some extent,

plaintiffs have been the prevailing party, and proceedings

were necessary to bring about further compliance in light of

Swann fv. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402

U. S. 1 (1971)]; Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of Ed., 442

F.2d 255 (6th Cir. 1971), and Davis v. Pontiac School Dist.,

443 F.2d 255 (6th Cir. 1971)" (J. A. 285) and that, " [t]he

Court has determined that plaintiffs were 'prevailing parties'

in the proceedings since the 1972 remand," id. The district

court which had heard all the proceedings in the case after

remand, specifically found that plaintiffs were successful

as an overall matter even though not "entirely successful."

The finding of fact of overall success in court was unappealed

by defendant Board, and is not clearly erroneous. Indeed,

the finding of the district court was altogether too stinting

since the proper inquiry was whether plaintiffs were "pre

vailing party" for the entire litigation, S. Rep. No. 94-1011,

9/ Plaintiffs believe that it is not necessary to the issue

whether plaintiffs were not "entirely successful", see infra.

15

supra, at pp. 5-6; H. R. Rep. No. 94-1558, supra, at pp. 7-8,

and numerous authorities cited. On this, the record is clear

and it is the law of this case that, plaintiffs' action has

10/

successful desegregated the public schools of Jackson.

However, the district court went further and ruled that it

would "award [ ] fees only to the extent it can fairly be

determined that plaintiffs' efforts were prevailing and

10/ In the 1972 opinion, this Court found that:

"To the credit of all concerned, certainly

including the District Judge, it is observed

that at long last Jackson has made some very

substantial progress toward the desegregation

of its school system. For example, we note

that although Jackson once maintained a dual

school system, as of October, 1971, all of

its schools were integrated to some degree;

that there is now one high school comprised

of 843 white and 643 black students; that

there are now three junior high schools inte

grated in ratios running from to-40 to 50-50;

that four of the nine elementary schools were

integrated in ratios similar to those just

cited for the junior high schools; but that in

the five remaining elementary schools, three

are over 90% black and two are over 90% white.

Integration in these five schools is minimal

because the location in the city is such that

no conceivable zoning change would produce

any substantially greater integration.

"Regardless, however, of these salutary

evidences of accomplishment, the possibility

exists that even greater accomplishment might

result from a further study of the situation

in the light of Swann, and of Robinson and

Davis. The cause will therefore be remanded

to give the District Court opportunity for

such consideration."

453 F.2d at 262.

16

successful towards further desegregation" (J.A. 286). This

was legal error. In addition, the lower court erred in

applying various factors of Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express,

Inc., 488 F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974).

A. Prevailing Upon Every Issue

Plaintiffs are not required to "prevail" on every issue.

In Bradley v. Richmond School Board, supra, 416 U. S. at 710,

plaintiffs were fully compensated even though the district

court rejected their plan and accepted that of the defendants.

1976 Attorney's Fees Act legislative history is clear that,

"[i]n appropriate circumstances, counsel fees under [the Act]

may be awarded pendente lite. See Bradley, fsupra]. Such

awards are especially appropriate where a party has prevailed

on an important matter in the course of litigation, even when

he ultimately does not prevail on all issues. See Bradley,

supra; Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375 (1970)"

S. Rep. No. 94-1011, supra, at p. 5 (emphasis added). Thus,

in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education. 66 F.R.D.

483 (W.D. N.C. 1975) plaintiffs were awarded fees for the

entire litigation "as the winners rather than the losers of the

litigation," even though plaintiffs did not "prevail" on every

issue because, as here, "the result has been the complete

desegregation of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school system,"

69 F.R.D. at 484. Compare Palmer v. Rogers, 10 EPD ^10,499

at pp. 6130-6131 (D.D.C. 1975). The civil rights attorney's

17

provisions, in short, are result-oriented.

The formulation of Swann was specifically approved in-

the 1976 Attorney's Fee Actr "The appropriate standards . . .

are correctly applied in such cases as Stanford Daily v .

Zurcher. 64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D. Cal. 1974); Davis v. County of

Los Angeles. 8 EPD 59444 (C.D. Cal. 1974); and Swann v .

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education fsupra]. . . . In

computing the fee, counsel for prevailing parties should be

paid, as is traditional with attorneys compensated by a fee

paying client, 'for all time reasonably expended on a matter'

Davis, supra; Stanford Daily, supra." S. Rep. No. 94-1011,

supra, at p. 6.

Davis expressly states that, "plaintiffs' counsel are

entitled to an award of fees for all time reasonably expended

in pursuit of the ultimate result achieved."

"It also is not legally relevant that plain

tiffs ' counsel expended a certain limited amount

of time pursuing certain issues of fact and law

that ultimately did not become litigated issues

in the case or upon which plaintiffs ultimately

did not prevail. Since plaintiffs prevailed on

the merits and achieved excellent results for the

represented class, plaintiffs' counsel are

entitled to an award of fees for all time reasonably

expended in pursuit of the ultimate result achieved

in the same manner that an attorney traditionally

is compensated by a fee-paying client for all time

reasonably expended on a matter."

8 EPD 59444 at p. 5049. The district court's issue-by-issue

parsing was specifically rejected in Zurcher, supra, 64 F.R.D.

at 684.

18

"However, several recent decisions, adopting a

different tack, deny fees for clearly meritless

claims but grant fees for legal work reasonably

calculated to advance their clients' interests.

These decisions acknowledge that courts should not

require attorneys (often working in new or changing

areas of the law) to divine the exact parameters of

the courts' willingness to grant relief. See, e.g.,

Trans World Airlines v. Hughes, 312 F. Supp. 478 (s.D. N.Y. 1970), aff*d with respect to fee award,

449 F.2d 51 (2d Cir. 1971), rev1d on other grounds,

409 U.S. 363, 93 S. Ct. 647, 34 L.Ed. 2d 577 (1973).

One Seventh Circuit panel, for example, allowed

attorneys' fees for legal services which appeared

unnecessary in hindsight but clearly were not

'manufactured.' Locklin v. Day-Glow color Corporation,

429 F.2d 873, 879 (7th Cir. 1970) (concerning fees

for antitrust counterclaims)."

Of course the defendant's attorneys have not billed their

client for only those services as to which they prevailed

and we preceive no reason for disparate treatment of plaintiffs'

counsel.

"Defendants next urge that since the plain

tiffs did not obtain all relief sought, they

may not be said to have prevailed in the

litigation. . . . The Court's failure to sustain

plaintiffs on all points is of no consequence

in our consideration that plaintiffs were the

prevailing party within the criteria for judg

ing the propriety of assessing counsel fees."

Wade v. Mississippi Cooperative Extension Serv., 378 F. Supp.

1251, 1254 (N.D. Miss. 1975) (Title VII action). In a suit

on behalf of Puerto Rican students in New York which was

settled by consent decree, the district court also awarded

counsel fees, making the following comment about the

19

prevailing party" language of the 1972 Education Amendments:

' Plaintiffs are, in any apposite and meaningful

sense, the 'prevailing party.' The decree gives

the relief they sought, consented to only after

more than a year and a half of bitter resistance

that began with a contention that the action

should be rejected out of hand as insufficient on its face."

Aspira of New York , Inc, v. Board of Education of New York.

394 F.Supp. 1161 (S.D. N.Y. 1975). Cf. Torres v.

Sachs, 538 F.2d 10 (2d cir. 1976). Similarly, in a stock

holders' derivative action which was terminated by settlement,

this court upheld a counsel fee award based upon the obvious

benefits to the corporation incurred as a result of the litiga-

tion* R_amey v. The Cincinnati Enquirer, Inc.. 508 F.2d 1188,

1196 (6th cir. 1974)7“

It is clear that the lower court's erroneous issue—by—

issue analysis, alone, requires reversal. "This Court took

into account in awarding the $1500 fee in 1973 that plaintiffs

had unsuccessfully challenged the inte [ ]grated Senior High

and Junior High student and teacher assignments as well as

administrative assignments." (j. a . 287). The court subse-

sfe ^lso' Lafferty v. Humphrey. 248 F.2d 82 (D.C. Cir.1957), cert, denied, 355 U.S.869 (1957) (awarding fees in case

rendered moot by compliance, in which original decision was

vacated on certiorari by Supreme court for this reason);

Ace Heating & Plumbing Co., Inc, v. Crane. 453 F.2d 30 (3d

Cir. 1971) (awarding fees to attorney for antitrust claimant

whose claim to share in settlement was disallowed); Maddox

O cto b er f 8 ? t i '9 7 4 f r r C° r P " C iV il N° ' 6 9 - M“628 ( N - D . T l a . ,

20

brought the amount up to $2,500 solely because of the passage

of time (J. A. 294). "For services since that time, again.

having in mind the limited results attained because of plaintiffs'

counsels' unsuccessful contentions in issue finally ruled upon,

the Court would allow an additional $2,500 for this services,

a total of $5,000.00," id. (emphases added).

B. Application of Factors

The attorney fee issue raised by plaintiffs on appeal in

1974 was that:

"[t]he $1,500 attorney's fee awarded them bears

no relation either to the time and effort of

counsel or to any other relevant considerations

which ought to govern a district court's exercise

of discretion in setting the amount of the award.

Plaintiffs also point out that the district court

failed to articulate the basis for its award or to

permit the parties to introduce evidence on this

matter. The latter fact makes it impossible for

this court to determine the propriety of the award

as such."

Monroe v. Board of commissioners of City of Jackson, supra,

505 F.2d at 108. This Court held that " [b]ecause our review

is dependent upon some sort of record of the basis for the

decision below, we vacate the judgment insofar as it relates

to the attorney's fee and remand the cause to the district

court for findings of fact and conclusions of law as to the

amount of any attorney's fee awarded under the standards

of Bradley v. School Board of city of Richmond, 416 U. S.

696, 94 S. Ct. 2006, 40 L.Ed. 2d 476 (1974)," 505 F.2d at 109.

21

On remand, the lower court wholly evaded the Court's

instructions, while the district court listed the

Johnson v . Georgia Highway Express factors (J.A. 292-294),

these factors are wholly ignored and the original $1,500

fee simply reannounced; " [a]t the time of the original award,

1973, $1,500 for fees was considered fair and reasonable, and

in line with what had previously been allowed in this case

and in similar cases" (A.A. 294). For the period since 1973,

the district court simply announced, without any reference

to the factors, "an additional $2,500." At no point does the

lower court opinion indicate how the review of the factors

had any effect on the outcome, much less offer a precise

statement of the hours in issue, hours added or subtracted,

or other effective and meaningful consideration of the factors

in determining the attorney's fees award. clearly, the lower

court had a sufficient factual record upon which to do so.

On the basis of the lower court opinion on remand, however,

this Court still does not have "findings of fact and con

clusions of law as to the amount of any attorney's fee awarded"

necessary for review as to the reasonableness of the award.

Furthermore, the lower court's opinion reveals apparent

errors in the existing discussion of factors (J.A. 292-294).

Thus, as to "novelty and difficulty of question" (J.A. 292),

the district court was of the view that "[t]his was not a

22

case of first impression on any issue and did not, or should

not have presented any special difficulty," and that as to

"undesirability of case and reputation of attorneys," that

Mr. Williams is well-known civil rights lawyer whose reputation

would not be adversely affected (J.A. 292-293). While

difficulty and novelty, and undesirability are certainly

factors to be weighed in giving an additional or bonus award,

they should not diminish an award. The rule is that, " [t]he

plaintiffs in school cases are 'private attorneys general'

vindicating national policy," Northcross v. Board of Education,

supra, 412 U. S. at 428. " [A]warding counsel fees to prevail

ing plaintiffs in such litigation is particularly important

and necessary if federal, civil and constitutional rights are

to be adequately protected," H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558, supra,

at p. 9. As to "preclusion of other employment," the lower

court misconceived that this litigation obviously did preclude

other employment for Mr. Williams as the extensive record

makes clear. Throughout its discussion of these factors, the

lower court failed to follow fundamental congressional

intent "that the amount of fees awarded under [the 1976

Attorney's Fees Act] be governed by the same standards which

prevail in other types of equally complex federal litigation,

such as antitrust cases and not reduced because the rights

involved may be nonpecuniary in nature," S. Rep. No. 94-1011,

supra, p. 6. This intent is borne out by the cases the Senate

23

Report chooses to endorse as those in which Johnson v.

Georgia Highway Express standards are "correctly applied":

Davis v. County of Los Angeles, supra, 8 EPD 59444 (65.24/hour

reasonable); Stanford Daily v. Zurcher, supra, 64 F.R.D. 680

(63.33/hour reasonable); Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, supra, 66 F.R.D. 483 (64.81/hour reasonable).

12/S. Rep. No. 94-1011, supra, p. 6. This should certainly be

the case where the " [ajbility and competency of counsel is

not questioned" and [c]ertainly plaintiffs' counsel possessed

abundant skill and experience in handling a case and pro

ceedings attendant thereto without difficulties" (J.A. 292,

293) .

II.

THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN DENYING ATTORNEYS

FEES FOR LEGAL REPRESENTATION FROM JANUARY

1971 TO JULY 1, 1972._______________________

Unlike the fees sought, infra, in part III, no prior

application of fees was made for the period from January

1971, when the request under the "obdurate obstinacy"

standard was sought, to July 1972 when § 718 of the Emergency

School Act became effective. As to the denial of these

fees, reversal is required by the holding of Bradley v .

Richmond School Board, supra, 416 U. S. at 710, that "'§ 718

12/ The lower court stated that, "[i]t is not unreasonable

for plaintiffs' counsel to expect $50 per ho [u]r or $350

a day for court time" (J.A. 294).

24

authorizes an award of attorneys' fees insofar as those

expenses were incurred prior to the date that the section

came into effect'" in a pending case. The district court,

however, first, sought to confine Bradley to its specific

situation of a pending fee application. Nothing in the

reasoning of Mr. Justice Blackmun's opinion for a unanimous

Court permits such a construction, which turns not on a

pending fee application but a pending action, see 416 U. S.

at 710-721. This was certainly the understanding of Con

gress; "[i]n accordance with applicable decisions of the

Supreme Court, the bill is intended to apply to all cases

pending on the date of enactment as well as all future cases.

Bradley v. Richmond School Board, [suprah" H.R. Rep. No. 94-

1558, supra, p. 4 n. 6 (emphasis added). Lower courts have

so held, see, e.g. Norwood v. Harrison, 410 F. Supp. 133,

141 n. 11 (N.D. Miss. 1976); Brewer v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 500 F.2d 1129 (4th cir. 1974). Moreover,

nothing requires that fees be sought prior to the end of

litigation; the Supreme Court, for instance, approved an

award of fees that was not sought until the end of the

litigation in the venerable Sprague v. Ticonic National

Bank, supra, 307 U. S. at 168-169. Second, the lower

.13/ See also legislative history set forth infra at p. 29.

14/ The lower court also cited several pre-Bradley decisions

wKose utility is questionable (J.A. 284) / see Brewer v. School

Board of the City of Norfolk, 500 F. 2d 1129 (4th Cir. 1974).

25

court states that, 11 [t]here was no claim for fees pending

■when this section became law on July 1, 1972" (J.A. 284).

Judge Wellford, who was not the trial judge through most

of the proceedings, is clearly in error as to the contents

of the record. The original complaint, filed January 8,

1963, concludes with the request "that the Court will allow

them their costs herein and such further, other or additional

relief as may appear to the Court to be equitable and just,"

Complaint at p. 18 (emphasis added), and all motions of

plaintiffs since the September 1964 motion for further relief

have consistently sought both fees and costs.

Thus, neither legal nor factual circumstances suffice

to rebut the application of Bradley to reverse the denial

of fees for the pre-July 1, 1972 period in question in the

15/

instant pending case.

15/ if the Court concludes that the retroactivity issue

must be reached in order to decide the question, we rely on

the discussion of retroactivity in part III, infra.

26

Ill

THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN DENYING ATTORNEYS

FEES FOR LEGAL REPRESENTATION FROM JANUARY

8 , 1963 TO JULY 1, 1972____________________

Fully eight years of lawyer services incurred by plain

tiffs' counsel will not be covered by the lower court's award

of counsel fees. The lower court rejected "'re-opening' the

case for further award from 1963 to 1971" because " [t]he prior

decision of the Court of Appeals precludes any further such

allowance of fees or costs prior to consideration of matters

presented to this Court during 1972" (J.A.284). in reaching

this decision, the trial court read the previous Court of

Appeals decision too broadly and the Emergency School Act too

narrowly, errors which unjustly deprived plaintiffs of com

pensation for virtually 60% of the case.

In effect, the lower court has concluded that the January

3, 1972 Court of Appeals affirmation of the 1971 district court

award of $5,000 counsel fees for the period of 1968 to January

6, 1971 is res judicata with regard to the question of counsel

fees. But that doctrine applies to bar relitigation of matters

which were raised or should have been raised. Plaintiffs did

not nor could they have sought entitlement to counsel fees based

on the Emergency School Aid Act and the later 1976 Fees Act

since that statute had not been enacted at the time of the Court

of Appeals affirmance. The doctrine of res judicata is no

defense to relitigation where, after the rendition of a judg

ment, a statute is enacted defining new rights and remedies.

See, lB Moore, Federal Practice § 2055 (1976) and cases cited

therein.

- 27

The counsel fee issue presented and previously decided

in 1971 and 1972 differed substantially from the counsel fees

issue presented to the court below. Prior to the enactment of

the Emergency School Aid Act, parties had no statutory

right to counsel fees covering the duration of the case. As the

district court stated in 1971 "the fee in a case of this sort is

not a fee as a matter of right for all services rendered from

the time of the inception of the case" (J.A. 27). Absent a

statute, a fee could be obtained only if the defendant's con

duct was "unreasonable, obdurate and obstinate" (J.A. 30).

Thus, the Emergency School Aid Act and 1976 Attorney's

Fees Act create a right by which prevailing parties may be com

pensated for engaging counsel in the public interest. The

difference between the two standards translated in this case

into years of uncompensated services for plaintiffs' counsel

because of the absence of "obdurate obstinacy" by the defendant,

without which plaintiffs had no right to counsel fees. See,

Alyeska pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness Society, 421 U.S. 240,

258 (1975). In United States v. Texas, 495 F.2d 1250, 1251

(5th Cir. 1974) the court observed that the standard of obstinate

noncompliance "is separate, apart from, and in addition to the

counsel fee remedy specifically provided by Congress in § 718 of

Title VII of the Emergency School Aid Act. . . . "

This is not to say that res judicata has no effect. Rather

it is to the new statute that one must look for the extent and

limitations of the right created. We now refer this Court

28

to the clarifying legislative history of the 1976 Fees Act,

confirming intent to make the right retroactive. Repre

sentative Drinan, one of the sponsors of the 1976 Fees Act,

stated:

"I should add also that, as the gentleman from

Illinois (Mr. Anderson) observed during con

sideration of the resolution on S.2278, this

bill would apply to cases pending on the date

of enactment. It is the settled rule that a

change in statutory lav? is to be applied to cases

in litigation. In Bradley versus Richmond SchooT

Board, the Supreme Court expressly applied that

longstanding rule to an attorney fee provision,

including the award of fees for services rendered

prior to the effective date of the statute"

(emphasis added).

Subcomm. of S . Comm, on the Judiciary, Civil Rights Attorney's

Fees Awards Act of 1976, supra, pp. 255-256, see also 202

("The Civil Rights Attorneys' Fees Award Act authorizes

federal courts to award attorneys' fees to a prevailing

party in suits presently pending in the federal courts.")

(Rep. Abourezk). See also H. R. Rep. No. 94-1558, supra.

Caselaw is consistent with this construction of the

statute, in Brewer v. School Board of Norfolk, supra, the

Fourth Circuit, prior to the enactment of the Emergency

Aid Act, had ordered the district court to award

fees based on a common fund theory. The district court

complied. After the enactment of the Emergency School

Aid Act, however, the Fourth Circuit vacated the district

court's award and commanded that court to determine plaintiffs'

- 29

eligibility for attorneys' fees under the new statute. The

lower court's narrow reading of retroactivity would not permit

a similar application of statutory standards in this case. See

also Finney v. Hutto. 548 F.2d 740 (8th Cir. 1976).

Moreover, the record is clear that counsel fee issues

were "pending" at the time the Emergency School Aid Act was en

acted. The district court, in 1971, expressly refrained from

16/

ruling on matters regarding plaintiffs' entitlement to "costs."

Thus, all questions regarding "costs" were pending when the

Emergency School Aid Act was subsequently enacted in 1972 and

the Attorney's Fees Act in 1976. Both statutes state, in

pertinent part, that a court may allow "the prevailing party

. . . a reasonable attorney's fee as part of the costs11

(emphasis added). The broad significance of counsel fees as

part of costs is that the statutory fees issue could not be

pinned on the conduct of the losing party, a punitive test,

but must be based on all the case-related services rendered by

counsel, a compensatory standard. The pendency of the issue

of "costs" satisfies even the lower court's narrow reading

12/of retroactivity.

Finally, the equities favoring an award of counsel fees

16/ "The Court would like to make one more observation and that

is that the Court wishes to assure counsel that this Court

stands ready to rule upon any dispute over the costs and thinks

that this matter should be taken up as soon as possible"

(J.A. 31).

17/ For a school desegregation case in which counsel fees were

awarded from 1963 to 1976, see Armstrong v. Bd. of Educ.,

infra at A-l.

30

so far outweigh any illusion of res judicata or a narrow

construction of the retroactivity of the pertinent legis

lation that counsel fees for the entire period should be

18/

awarded. Again, the equitable justifications for full

compensation are on record. The trial court in 1971 recognized

some of these factors:

"Of course, there is a strong and convin

cing appeal to the moral right for a fee. When

we look back at the history of this case, we

see a sight that isn't pleasant for the white

race, of which I am a member, of course. It

is not a panorama of something of which we

should be proud. It took courage to file this

suit, and it took courage for people like Brenda

K. Monroe to want to break the system that was

so basically unfair and was ingrained into the

school systems not only in Jackson and Madison

County but other places (J.A. 27).

"Based on objective fairness in the community

one hundred thousand dollars would be a modest

fee but we cant take that into consideration in

awarding a fee" (J.A. 27-28).

The time omitted from the lower court's award includes

all the time spent by counsel to obtain the Supreme Court's

decision that the defendants were perpetuating an unconsti-

18/ Equitable factors have been used to overcome the basic

policies of res judicata. See, e.g., Adams v. Pearson,

411 111. 431, 104 N.E. 2d 267 (1952). A long line of cases

have recognized that the Emergency School Aid Act should be

read liberally in favor of awarding fees, see e.g., Norwood

v. Harrison, 410 F. Supp. 133 (N.D. Miss. 1976), the purpose

being "'to encourage individuals injured by racial discrimi

nation to seek judicial relief.'" Northcross v. Bd. of Educ..

supra, p. 13, 412 U.S. at 428.

31

tutional dual school system. Despite their protestations,

defendants benefited from the efforts of plaintiffs, through

their counsel, to move their school system from a dual to a

unitary one.

CONCLUSION

For above stated reasons, the order on attorney's fees

and judgment on the decision should be vacated, and the case

remanded with directions for proceedings under proper standards

required by § 718 of the Emergency School Aid Act of 1972,

20 U.S.C. § 1617, and the Civil Rights Attorney's Fees Act

of 1976, 42 U.S.C. § 1988.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

KELLIS E. PARKER

BILL LANN LEE

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

MAURICE FRANKLIN

1414 parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

32

A P P E N D IX

IN T H E U N IT E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T COURT

F O R T H E NO RTH ERN D I S T R I C T OF ALABAM A

SO U TH ERN D I V I S I O N

D W IG H T A RM STRO N G , e t a l . ,

P l a i n t i f f s ,

*

*

•k

*

k

BOARD OF E D U C A T IO N OF T H E *

C I T Y OF B IR M IN G H A M , A LA B A M A ,*

e t a l . , *

*

D efendan ts . *

C I V I L A C T IO N NUM BER

967 8

;?! CLsax’s o?.-ics

riDHTHinn titrn icT or Alabama

6up 1 4 i975

F IN D IN G S O F F A C T AND

C O N C LU S IO N S OF LAW

T h i s c a u s e cam e o n f o r a h e a r i n g o n p l a i n t i f f s '

M o t io n f o r A w a rd o f C o u n s e l F e e s . B a s e d o n a t w e n t y - s e v e n

p a g e d o c u m e n t s u b m it t e d b y p l a i n t i f f s ' c o u n s e l , e n t i t l e d ,

" S t a t e m e n t o f T im e E x p e n d e d b y A t t o r n e y s f o r t h e P l a i n t i f f s

a n d T h e i r A s s o c i a t e C o u n s e l F ro m M a y , 1 9 6 3 t o J u l y , 1 9 7 6 " ,

a n d b a s e d o n t h e o r a l t e s t i m o n y o f p l a i n t i f f s ' c o u n s e l b e f o r e

m e , t h e C o u r t ' s r e v i e w o f t h e f i l e i n t h i s c a u s e , a n d t h e

C o u r t ' s own p e r s o n a l a c q u a i n t a n c e w i t h t h e s e r v i c e s o f

p l a i n t i f f s ' a t t o r n e y s s i n c e 1 9 7 5 , a n d t h e a r g u m e n t s o f c o u n s e l

f o r t h e p l a i i n t i f f s a n d t h e d e f e n d a n t S c h o o l B o a r d , t h e C o u r t

m a k e s t h e f o l l o w i n g f i n d i n g s o f f a c t a n d c o n c l u s i o n s o f l a w :

1 . C o u n s e l f o r p l a i n t i f f s a r e e n t i t l e d t o a n a w a rd

o f a r e a s o n a b l e a t t o r n e y s ' f e e i n t h i s c a u s e , p u r s u a n t t o

2 0 U . S . C . § 1 6 1 7 , a n d B r a d l e y v . S c h o o l B o a r d o f t h e C i t y o f

R ic h m o n d , 94 S . C t . 2 0 0 6 ( 1 9 7 4 ) . T h e C o u r t h a s m ade t h e

d e t e r m i n a t i o n o f t h e a m o u n t o f a t t o r n e y s ' f e e s a p p l y i n g t h e

s t a n d a r d s s e t f o r t h b y t h e F i f t h C i r c u i t C o u r t o f A p p e a l s i n

J o h n s o n v . G e o r g i a H ig h w a y E x p r e s s , 4 88 F . 2 d 7 1 4 .

2 . C o u n s e l f o r p l a i n t i f f s h a v e c o l l e c t i v e l y

e x p e n d e d 2 ,1 4 0 h o u r s i n t h e p r o s e c u t i o n o f t h i s c a u s e f o r

t h e y e a r s 1 9 6 3 t h r o u g h 1 9 7 6 , i n c l u d i n g t h r e e s u c c e s s f u l a p p e a l s

2

t o : t h e . F i f t h C i r c u i t C o u r t o f A p p e a l s . T h e C o u r t f i n d s t h a t .

c o u n s e l p r o b a b l y e x p e n d e d m o re t h a n t h e 2 ,1 4 0 h o u r s t h a t

t h e y s e t f o r t h i n t h e i r S t a t e m e n t , s i n c e m e t i c u l o u s r e c o r d s

w e r e n o t k e p t b y c o u n s e l i n t h e e a r l y s t a g e s o f t h i s l i g i -

g a t i o n a n d o n l y a f t e r 1 9 6 8 w e re m o re m e t i c u l o u s r e c o r d s k e p t .

H o w e v e r , a f t e r r e v i e w i n g t h e v o lu m in o u s R e c o r d i n t h i s c a s e ,

a n d . c o n s i d e r i n g sam e i n t h e l i g h t o f t h e C o u r t ’ s own e x p e r i e n c e

i n .t h e t r i a l o f h o t l y c o n t e s t e d c a s e s , i t i s t h e C o u r t ' s f i n d i n g

t h a t 2 , 1 4 0 h o u r s i s a m o d e s t s t a t e m e n t o f t h e t im e e x p e n d e d b y

a t - . l e a s t s i x a t t o r n e y s o v e r a p e r i o d o f 13 y e a r s o f l i t i g a t i o n .

Som e o f t h e h o u r s f o r c e r t a i n w o r k w e re e x p e n d e d s e p a r a t e l y ,

a n d som e h a v e b e e n lu m p e d t o g e t h e r .

3 . P l a i n t i f f s k e p t n o a c c u r a t e r e c o r d s o f c o s t

e x p e n d e d i n h o t e l , t r a n s p o r t a t i o n a n d m e a l s , a s w e l l a s l o n g

d i s t a n c e t e l e p h o n e c a l l s . C o n s i d e r i n g t h e v e r y l e a s t t h a t

c o u l d b e e x p e n d e d , t a k i n g i n t o c o n s i d e r a t i o n t h a t t h r e e

a p p e l l a t e a p p e a l s w e r e m a d e , a n d som e o f t h e l a w y e r s i n t h i s

c a s e r e s i d e d i n New Y o r k C i t y , $ 3 , 5 0 0 . 0 0 i s a m o d e s t a m o u n t

t o a w a rd a s c o s t s f o r t h e s e i t e m s i n t h i s c a s e . T h e C o u r t

s o f i n d s t h a t p l a i n t i f f s i n c u r r e d $ 3 , 5 0 0 . 0 0 i n c o s t s i n

m a i n t a i n i n g t h i s a c t i o n .

4 . T h e r e p u t a t i o n , e x p e r i e n c e a n d s k i l l o f p l a i n t i f f s '

c o u n s e l f o r w o r k i n t h e f i e l d o f c i v i l r i g h t s i s i m p r e s s i v e .

R e c e n t l y , t h e F i f t h C i r c u i t C o u r t o f A p p e a l s co m m e n te d o n t h e

s k i l l o f t h e s e a t t o r n e y s , i n t h e c a s e o f U n it e d S t a t e s v .

U n it e d S t a t e s S t e e l , 5 2 0 , F . 2 d 1 0 4 3 . A l t h o u g h p l a i n t i f f s '

a t t o r n e y s c l a i m f o r t h e i r s e r v i c e s , $ 7 5 .0 0 a n h o u r a n d t h i s

f i g u r e d o e s n o t a p p e a r t o b e a n u n r e a s o n a b l e c h a r g e , t h e

C o u r t r e c o g n i z e s t h a t som e o f t h e s e r v i c e s p e r f o r m e d b y

p l a i n t i f f s ' c o u n s e l w e re p e r f o r m e d m o re t h a n 12 t o 13 y e a r s

a g o . T a k i n g i n t o c o n s i d e r a t i o n t h a t a f e e o f l e s s e r a m o u n t

m ig h t h a v e b e e n r e a s o n a b l e i n t h e e a r l y y e a r s o f t h i s l i t i g a t i o n ,

A - 2

(

3

c e r t a i n l y $ 7 5 . 0 0 a n h o u r o r p e r h a p s m o r e , w o u ld b e r e a s o n a b l e

d u r i n g t h e l a t t e r s t a g e s o f t h i s l i t i g a t i o n . F o r t h i s r e a s o n ,

t h e C o u r t f i n d s t h a t t h e r e a s o n a b l e v a l u e o f t h e h o u r l y s e r v i c e s

J

t o t a l l y r e n d e r e d b y p l a i n t i f f s ' c o u n s e l s h o u l d b e f i x e d a t

$ 6 0 - 0 0 p e r h o u r . B a s e d o n h o u r l y r a t e s , p l a i n t i f f s w o u ld b e

e n t i t l e d t o a n a t t o r n e y s ' f e e o f $ 1 2 3 ,4 0 0 1 0 0 . H o w e v e r , t h e

t e a c h i n g o f J o h n s o n v . G e o r g i a H ig h w a y E x p r e s s i s t h a t h o u r l y

c o n s i d e r a t i o n s a r e n o t t h e s o l e c r i t e r i a o n w h ic h a t t o r n e y s '

f e e s s h o u l d b e a w a r d e d . S e e a l s o B i r d i e Mae D a v i s v . M o b i le

C o u n t y B o a r d o f E d u c a t i o n , 5 2 5 F . 2 d 8 6 5 . T h e n a t u r e o f t h e

p l a i n t i f f s ' l e g a l s e r v i c e s w e r e i n v a l u a b l e t o t h e c l a s s t h e y

r e p r e s e n t e d a n d t o t h e C i t y o f B i r m in g h a m , a s w e l l a s t o p r o t e c t

a n d i n s u r e r i g h t s g u a r a n t e e d b y t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n o f t h e U n i t e d

S t a t e s , a n d T i t l e V I o f t h e C i v i l R i g h t s A c t o f 1 9 6 4 . D u r i n g

t h e p e r i o d o f t im e t h a t p l a i n t i f f s ' a t t o r n e y s h a v e b e e n i n

t h i s c a s e , t h e i r f e e , t o som e e x t e n t h a s b e e n o f a c o n t i n g e n t

n a t u r e . T h e r e f o r e , t h e C o u r t f i n d s t h a t i n a d d i t i o n t o t h e

h o u r l y r a t e h e r e t o f o r e d e t e r m in e d , p l a i n t i f f s a r e a l o s e n t i t l e d

t o a n a d d i t i o n a l $ 1 8 , 0 0 0 . 0 0 b y r e a s o n o f t h e r e s u l t s o b t a i n e d ,

a s w e l l a s b y r e a s o n o f t h e c o n t i n g e n t n a t u r e o f t h e i r p r o

f e s s i o n a l r e l a t i o n s h i p .

t h e C o u r t i s o f t h e o p i n i o n t h a t t h e f a i r a n d r e a s o n a b l e v a l u e

o f t h e s e r v i c e s o f A d a m s , B a k e r a n d C le m o n , a n d t h e NAACP

L e g a l D e f e n s e F u n d , s i n c e 1 9 6 3 , i s $ 1 5 0 , 0 0 0 . 0 0 , w h ic h a m o u n t

t h e y a r e e n t i t l e d t o r e c o v e r f r o m t h e d e f e n d a n t s .

5 . T h e r e f o r e , i n c o n s i d e r a t i o n o f t h e f o r e g o i n g .

DONE a n d O RD ER

7 r/i

A -3

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned certifies on this 25th day of April

1977 that copies of the foregoing Brief Of plaintiffs-

Appellants were served on counsel for all parties by U. S.

mail, first class, postage prepaid, addressed to:

Sidney W. Spragins, Esq.

P. 0. Box 2004

Jackson, Tennessee 38301

Mr. Nat Douglas, Esq.

Ms. Kaydell Wright, Esq.

U. S . Department of Justice

Civil Rights Division

Education Section

Washington, D. C. 20530

Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants