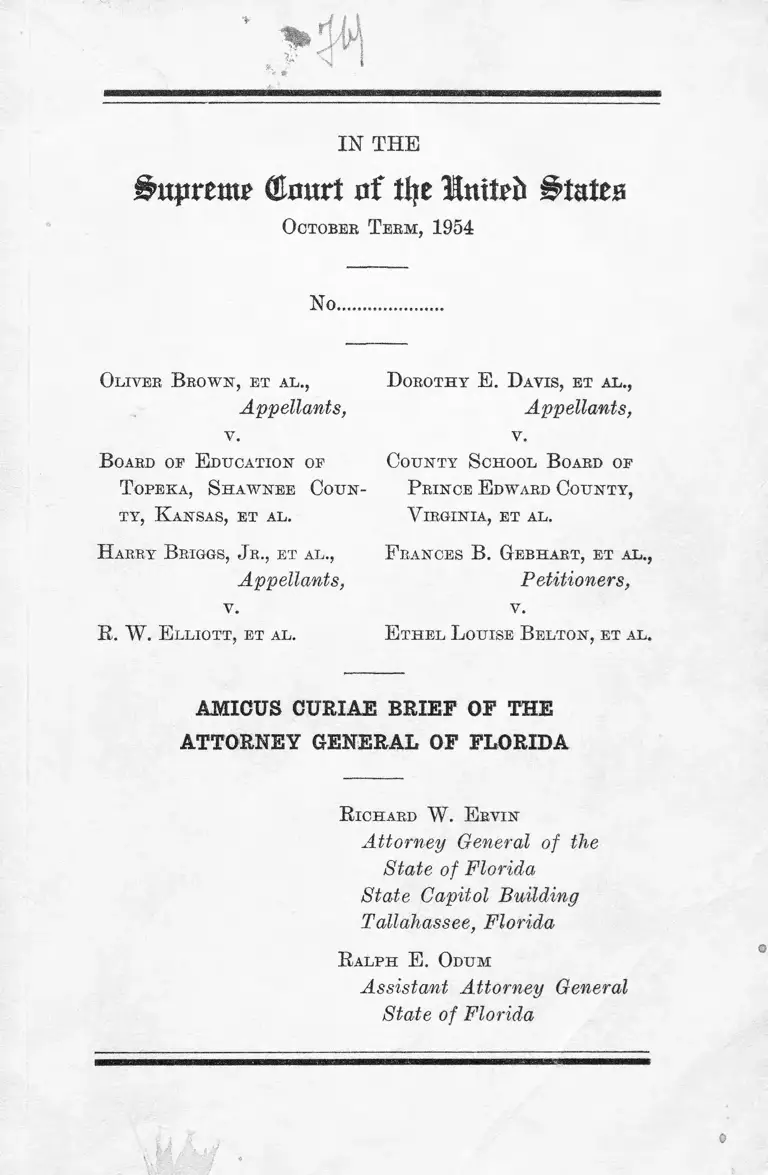

Brown v. Board of Education Amicus Curiae Brief of the Attorney General of Florida

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1954

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Board of Education Amicus Curiae Brief of the Attorney General of Florida, 1954. 953ae9db-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f6e41e77-67e0-4d76-b691-e007112f7cce/brown-v-board-of-education-amicus-curiae-brief-of-the-attorney-general-of-florida. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

j&tpremF (flourt xti tlje W nittb States

O ctober T e rm , 1954

No

O liver B r o w n , et a l .,

Appellants,

v.

B oard of E ducation op

T o pek a , S h a w n e e C o u n

ty , K ansas, et al .

H arry B riggs, J r ., et al .,

Appellants,

v.

R . W . E llio tt , et al .

D orothy E . D avis, et a l .,

Appellants,

v.

Co u n ty S chool B oard op

P rince E dward Co u n t y ,

V irgin ia , et a l .

F rances B . G ebh art , et a l .,

Petitioners,

v.

E t h e l L ouise B elto n , et .al.

AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF OF THE

ATTORNEY GENERAL OF FLORIDA

R ichard W . E rvin

Attorney General of the

State of Florida

State Capitol Building

Tallahassee, Florida

R a l p h E . O du m

Assistant Attorney General

State of Florida

o

IN THE

Supreme (to rt of tfye lnttr& States

O ctober T eem , 1954

No,

Oliver B ro w n , et a l .,

Appellants,

v.

B oard op E ducation op

T opeka , S h a w n ee C ou n

t y , K ansas, et al .

H arry B riggs, J r ., et a l .,

Appellants,

v.

E . W . E llio tt , et al .

D orothy E . D avis, et al .,

Appellants,

v.

Co u n ty S chool B oard op

P rince E dward Co u n t y ,

V irgin ia , et al .

F rances B. G ebh art , et al .,

Petitioners,

v.

E th el L ouise B elton , et al .

AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF OF THE

ATTORNEY GENERAL OF FLORIDA

R ichard W . E rvin

Attorney General of the

State of Florida

State Capitol Building

Tallahassee, Florida

R alph E . O dum

Assistant Attorney General

State of Florida

Subject Matter Index

Page

Preliminary Statement ............................ 1

PART ONE

A Discussion of the Reasons for a Period of Gradual

Adjustment to Desegregation to be Permitted in Florida

with Broad Powers of Discretion Vested in Local School

Authorities to Determine Administrative Procedures..... 3

A. The Need for Time in Revising the State Legal

Structure ... ................ 5

I. Examples of Legislative Problems ................. 7

(a) Scholarships ................................. 7

(b) Powers and Duties of County School

Boards ........................................................... 10

(c) State Board of Education and State Super

intendent ........... 12

II. Discussion of Legislative Attitudes................... 14

B. The Need for Time in Revising Administrative

Procedures .... 17

I. Examples ............................................................. 18

(a) Transportation ............................................. 18

(b) Redistricting ................................................ 19

(c) Scholastic Standards ............... 19

(d) Health and Moral W elfare......................... 20

C. The Need for Time in Gaining Public Acceptance.. 23

I. A Survey of Leadership Opinion....................... 23

II. General Conclusions ............................................ 24

Regional Variations ............................................ 32

A Note on Responses of Legislators.................. 33

III. The Dade County Report ..................................... 34

IV. Discussion ............................................................. 34

D. Intangibles in Education ........................................... 41

E. Reason for H ope........................................................ 43

F. Regional Variations .......................................... 53

G. Discussion ................ ........ ..... ................................ 55

PART TWO

Specific Suggestions to the Court in Formulating a

Decree .................................................................... 57

Introductory Note ........... 59

Specific Suggestions.................................................... 61

PART THREE

Legal Authority of the Court to Permit a Period of

Gradual Adjustment and Broad Powers of Administra

tive Discretion on the Part of Local School Authorities.. 67

A. Judicial Cases Permitting Time ............................. 69

I. United States v. American Tobacco C o ............. 69

II. Standard Oil v. United States..................... ....... 70

III. Georgia v. Tennessee Copper Co.......................... 72

State of Georgia v. Tennessee Copper Co., etc.... 72

IV. State of New York v. State of New Jersey, etc... 75

V. Martin Bldg. Co. v. Imperial Laundry .............. 75

B. Administrative Discretion Cases........ .................... 77

I. United States v. Paramount Pictures ................ 77

II. Alabama Public Service Commission v. Southern

Railway Co........................................................ 78

People of the State of New York v. United

States.................................. 79

III. Burford v. Sun Oil Co............................................ 80

Page

ii

IV. Far Eastern Conference, United States Lines

Co., etc. v. United States and Federal Mari

time Board ........................................................ 82

V. Minersville School District v. Grobitis................ 82

VI. Cox v. New Hampshire.......... .............................. 83

VII. Barbier v. Connolly.............................................. 84

VIII. Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co................................. 84

C. Remarks .................................................................... 85

PART FOUR

Considerations Involved in Formulating Plans for

Desegregation ..................................................... 87

A. Changes in the L aw .................................................. 89

B. Plans for Integration ................................................. 91

PART FIVE

Conclusion ....... 97

Page

iii

A ppendix A

Page

RESULTS OF A SURVEY OF FLORIDA LEADER

SHIP OPINION ON THE EFFECTS OF THE U. S.

SUPREME COURT DECISION OF MAY 17, 1954,

RELATING- TO SEGREGATION IN FLORIDA

SCHOOLS ........... 99

Introduction .......... 101

Attorney General’s Research Advisory Committee for

the Study of Problems of Desegregation in Florida

Schools ....................................................................... ..102

THE REPORT AND THE CONCLUSIONS ......... ....105

General Conclusions.................................................. 107

LEADERSHIP OPINION BY QUESTIONNAIRE—

AND CONCLUSIONS............................................... .....

The Questionnaires ................................................... .

Questionnaire Returns and Method of Analysis.........

Findings ................................................................. ......

Regional Variations ................................................... .

Responses of Legislators.......................................... .

Conclusions ..................................................................

Sample Questionnaire .............................................. .

Sample Questionnaire ............ ....................................

Table 1—Questionnaires Sent and Returned,

by Groups........................................................... .

Table 2—Per Cent Expressing Various Attitudes

Towards Decision, by Groups............................ 136,137

Table 3—Per Cent Agreeing or Disagreeing with

the Decision, by Groups ....................................... .....138

Table 4—Per Cent Willing or Unwilling to Comply

with Courts and School Officials ̂ by Groups.......... 139

.113

.115

.116

.118

,124

,126

,127

,129

132

135

iv

Table 5—Per Gent of Each Group Predicting Mob

Violence and Serious Violence ................ ....... .........140

Table 6—Per Cent of Each Group Doubting Ability

of Peace Officers to Cope with Serious Violence..........141

Table 7—Per Cent of Each Group Who Believe

Peace Officers Could Cope with Minor Violence......... 142

Table 8—Per Cent of Groups Polled Who Believe

Most of Other Specified Groups Disagree with the

Decision ...... 143

Table 9—Per Cent of Each Group Designating

Various Methods of Ending Segregation as Most

Effective ....................................................................... 144

Table 10-—Per Cent of Each Group Designating

Specified Grade Levels as Easiest Place to Start De

segregation ................................................................. 145

Table 11—Per Cent of Each Group Designating

Various Problems as Being Likely to Arise................146

Table 12—Confidence of Peace Officers in Ability

to Cope with Serious Violence, by Attitude Towards

Desegregation ..............................................................147

Table 13—Confidence of Peace Officers that Police

Would Enforce School Attendance Laws for Mixed

Schools, by Attitude Towards Desegregation...........147

Table 14—Per Cent of Peace Officers Expressing

Various Attitudes, by Region ................................... 148

Table 15—Per Cent of White Principals and Super

visors Agreeing or Disagreeing with the Decision,

by Region........... ......................................................... 149

Table 16—Per Cent of White Principals and Super

visors Willing or Unwilling to Comply, by Region....149

Table 17—Per Cent of Peace Officers Predicting

Mob Violence, by Region............................................ 150

Table 18—Number and Per Cent of Peace Officers

and White Principals and Supervisors Predicting

Serious Violence, by Region ..................................... 150

Page

v

Table 19—Number and Per Cent of Peace Officers

and White Principals and Supervisors Doubting

that Peace Officers Could Cope with Serious

Violence, by Region ............. ........................ ....... ...... 151

Table 20—hi umber and Per Cent of Legislators

Favoring Each of Five Possible Courses of Legisla

tive Action .................................................................. 152

Page

LEADERSHIP OPINION BY PERSONAL INTER.

VIEW—AND CONCLUSIONS..........................................153

Selection of Counties .......................................... .............153

Method of Study.......................................... .........154

Findings ................................................................... 155

The Personal Interview Schedule......................... 160

Personnel Interviewed...................................... 162

Reliability of Judgments in the Analysis of Recorded

Interviews on the Subject of the Supreme Court’s

Segregation Decision .......................... ............................164

Table 1—Per Cent Agreement Between Judges.....167

Table 2—Frequencies of Ratings of Interviewee

Feeling by Judges I & I I ................. .................. ........168

Table 3—Frequencies of Ratings of Interviewee

Feeling by Judges III & I V .......................................169

Table 4—Frequencies of Ratings of Interviewee

Feeling by Judges V & VI............................. .............170

Table 5—Frequencies of Ratings of Interviewee

Feeling by Judges VII & VTTT....................................171

Table 6—Frequencies of Classification of Interviews

by Judges I & I I ....................................... ................. 172

Table 7—Frequencies of Classification of Interviews

by Judges III & I V ............................................. .........173

Table 8—Frequencies of Classification of Interviews

by Judges V & V I ....................................................... 174

Table 9—Frequencies of Classification of Interviews

by Judges VII & V I I I ............................ ............... ....175

v i

ANALYSIS OF NEGRO REGISTRATION AND

Page

VOTING IN FLORIDA, 1940.1954................................... 177

Summary Sheet of Attorney General’s

Questionnaire, July 15, 1954......................... ...........180-184

EXISTING PUBLIC SCHOOL F A C I L I T I E S IN

FLORIDA AND FACTORS OF SCHOOL ADMINIS

TRATION AND IN S T R U C T IO N A L SERVICES

AFFECTING SEGREGATION ............... 185

Achievement Test Scores .............................................. 189

Counties with No Negro High Schools......................... 191

Examples of Inter-Racial Cooperation ...... 191

Table 1—Summary of Expenditures—all funds—

Both Races, 1952-53 ............ 193

Table 2—Significant Trends in the Growth of

Florida Schools under Dual System of Education

1930 to 1953 ............. ..194

Table 3—Enrollment ..... 195

Table 4—Comparison of Percentile Ranks for White

and Negro Examinees in the Florida Statewide

Twelfth-Grade Testing Program Spring 1949

through Spring 1953 ...................................................196

Table 5—Counties with No Negro High School

1952-53 .........................................................................197

Table 6—Status of Elementary Principals 1953-54....198

Map—Amount and Per Cent of Nonwhite Popu

lation: 1950 ........................... 199

Map—Proportion of Negro Enrollment to Total

Enrollment by Counties 1952-53 ............................... 200

AN INTENSIVE STUDY IN DADE COUNTY AND

NEARBY AGRICULTURAL AREAS — AND CON

CLUSIONS ...........................................................................201

General Conclusions..................................................... ...201

Factors Indicating a Gradual Approach as the So

lution to this Problem.................................................... 204

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................. 207

vii

A ppendix B

Page

EXAMPLES OF FLORIDA’S CONSTITUTIONAL,

STATUTORY AND STATE SCHOOL BOARD

REGULATORY PROVISIONS RELATING TO

SEGREGATION..................................................................211

Florida Constitution ............... 213

Florida Statutes.......... ................ 215-218

State School Board Regulations ............................219-243

Table of Authorities

Alabama Public Service Commission v. Southern Rail

way Company, 341 U.S. 341, 95 L. Ed. 1002, 71 S. Ct. 762

1951 ...................................................................................... 78

Barbier v. Connolly, 113 U.S. 27, 5 S. Ct. 357, 28 L. Ed.

923 (1885)....................................................................... 84

Burford v. Sun Oil Co., 319 U.S. 315, 87 L. Ed. 1424, 83

S. Ct. 1098 (1943) ............................................................ 80

Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 U.S. 569, 61 S. Ct. 762, 85

L. Ed. 1049 (1941) ...................................................... 83

Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U.S. 365, 47 S. Ct. 114,

71 L. Ed. 303 (1926) ........................................................... 84

vm

Far Eastern Conference, United States Lines Co., States

Marine Corporation, et al. v. United States and Federal

Maritime Board, 342 U.S. 570, 96 L. Ed. 576, 72 S. Ct.

492 (1952)............................................................................ 82

Georgia v. Tennessee Copper Co., 206 U.S. 230, 51 L. Ed.

1038, 27 S. Ct. 618 (1907) ......................................... .......... 73

Martin Bldg. Co. v. Imperial Laundry Co., 220 Ala. 90,

124 So. 82 (1929) ................................................................. 75

Minersville School Distict v. Gobitis, 310 U.S. 586, 60 S.

Ct. 1010, 84 L. Ed. 1375 (1940) .......................................56, 82

New York v. United States, 331 U.S. 284, 334-336 (1947).. 79

New Jersey v. New York, 283 U.S. 473, 75 L. Ed. 1176,

51 S. Ct. 519 (1931); 284 U.S. 585, 75 L. Ed. 506, 52 S. Ct.

120; 289 U.S. 712; 296 U.S. 259, 80 L Ed. 214, 56 S. Ct.

188 ............................................................................... 70,71,72

People of the State of New York v. State of New Jersey

and Passaic Valley Sewerage Commissioners, 256 U.S.

296, 65 L. Ed. 937, 41 S. Ct. 492 (1921)............................. 75

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537,16 S. Ct. 1138, 41 L. Ed.

256 (1896) .......... ..................................................................... ...6, 55

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649...................................... 177

Standard Oil Co. v. U.S., 221 U.S. 1, 31 S. Ct. 502, 55

L. Ed. 619 (1910)................................................................. 70

State of Georgia v. Tennessee Copper Co. and Ducktown

Sulphur, Copper & Iron Co., Ltd., 237 U.S. 474, 59 L. Ed.

1054, 35 S. Ct. 631 (1915); 237 U.S. 678, 59 L. Ed. 1173,

35 S. Ct. 752 (1915); 240 U.S. 650, 60 L. Ed. 846, 36 S. Ct.

465 (1916) ....... ......... ........................................................ 73, 74

United States v. American Tobacco Co., 221 U.S. 106, 31

S. Ct. 632, 55 L. Ed. 663 (1911)........................................ 69

United States v. Paramount Pictures, 334 U.S. 131, 92 L.

Ed. 1260, 68 S. Ct. 915 (1948) ........................................... . 77

Page

ix

UNITED STATES LAW

26 State at L., 209, Ch. 647, USC Title 15, §1

Page

(Anti-Trust Act) ............................. 70

FLORIDA CONSTITUTION AND STATUTES

Art. 12, Sec. 1, Florida Constitution................ ...............213

Art. 12, See. 12, Florida Constitution................ 5, 6,15, 213

Sec. 228.09, Florida Statutes.............................................215

Sec. 229.07, Florida Statutes................................... . . . . . . . . . .12, 215

Sec. 229.08, Florida Statutes........ ............................... ......12, 216

Sec. 229.16, Florida Statutes .......................... ....13, 216

Sec. 229.17, Florida Statutes..................................... 13, 217

Sec. 230.23, Florida Statutes............................................ 10, 217

Sec. 239.41, Florida Statutes ............................... 7, 8, 9, 218

Sec. 242.46, Florida Statutes............................................ 41

STATE SCHOOL BOARD REGULATIONS

The Calculation of Instruction Units and Salary

Allocations from the Foundation Program................13, 219

Administrative and Special Instructional Service.....13, 220

Units for Supervisors of Instruction............................13, 221

Establishment, Organization and Operation of Small

Schools ................................................................................225

School Advisory Committees............................................. 13, 226

Qualifications, Duties and Procedure for Employment

of Supervisors of Instruction.......................................... ....13, 228

Isolated Schools ............................................................13, 232

The Distribution of General Scholarships.........................13, 235

Scholarship Committee .....................................................240

x

Scholarship for Preparation of Teachers and House and

Page

Senatorial Scholarships...................................................... 241

State Supervisory Services.............................................13,242

Transportation of Pupils .................................................. 243

MISCELLANEOUS

Ashmore, Harry S., “ The Negro and the Schools” .......34, 39

Garter, Hodding, Reader’s Digest, September 1954, p. 53.. 20

Clark, Kenneth B., “ Findings,” Journal of Social Issues,

IX, No. 4 (1953), 50 .... .................................................25,109

Dietrich, T. Stanton, Statistical Atlas, Florida’s popula

tion; 1940 and 1950; Research Report No. 3, Florida State

University, June, 1954 ........................................................189

Emory University Law School, Joumal of Public Law,

Vol. 3, Spring 1954, No. 1............... ...........................37, 38, 89

Florida Facts, Florida State University, School of

Public Administration..................................................32,124

Florida State Board of Health, Annual Report 1953,

Supp. No. 1, Florida Vital Statistics............................... 21

Florida State Board of Health, Annual Report 1953,

Supp. No. 2, Florida Morbidity Statistics 1953, Table

No. 5, p. 2 5 .......................................................................... 21

Katz, Daniel and Hadley Cantril, “ Public Opinion

Polls,” Sociometry, I (1937), 155-179 ..............................116

Psychol. Bull., 1949, 46, 433-489 .......................................166

Semi-Weekly Floridan, Tallahassee, Florida, April 23,

1867, page 2 ........................................................................ 95

State of Florida, Biennial Report, Superintendent of

Public Instruction 1950-51 .......... 32

The Antioch Review, VIII (Summer 1948), 193-210...... 128

“ The Impending Crisis of the South,” New South, VTH,

No. 5, (May 1953) (Atlanta: Southern Regional Coun

cil^ ......................................................................................105

U. S. News & World Report, page 35, August 27, 1954..... 31

xi

Preliminary Statement

This amicus brief filed by the Attorney General of the

State of Florida pursuant to permission granted by the

Court in its decision of May 17,1954, in the above cases, con

tends that the Court should resolve its implementation de

cision in favor of the propositions stated in questions 4B

and 5D.

The Court will find from a study of this brief that a sin

cere and thorough effort has been made by the Attorney

General of Florida to present reasonable and logical an

swers to questions 4 and 5. These answers are respectfully

submitted by way of assistance to the Court and are based

upon a scientific survey of the factual situation in Florida,

embracing practical, psychological, economic and socio

logical effects, as well as an exhaustive research of legal

principles.

However, in filing this brief in answer to the hypothetical

questions propounded, the Attorney General is not inter

vening in the cause nor is he authorized to submit the State

of Florida as a direct party to the instant cases. Neither can

his brief preclude the Florida legislature or the people

of Florida from taking any legislative or constitutional ac

tion dealing with the segregation problem.

1

Part One

A discussion of the reasons for a period of

gradual adjustment to desegregation to

be permitted in Florida with broad pow

ers of discretion vested in local school

authorities to determine administrative

procedures.

3

A. The Need For Time

In Revising The State

Legal Structure

There is a need for reasonable time and planning by

State and local authorities in any revision of the existing

legal structure of the State of Florida, (which now provides

an administrative framework for the operation of a dual

system of public schools) in order to provide a legal and

administrative structure in which compliance with the

Brown decision can be accomplished in an orderly manner.

Examples of Florida constitutional, statutory, and state

school board regulatory provisions related directly or in

directly to segregated public schools are set forth in Ap

pendix B.

The basic change which must be made if Florida is to

comply with the non-segregation decision is either a repeal

or revision of Article XII, Section 12, of the Florida Con

stitution, which provides:

“ White and colored; separate schools.—White and

colored children shall not be taught in the same school,

but impartial provision shall be made for both.”

This provision in the basic law of Florida has been in

existence since 1885. During the past 69 years it has been

rigidly observed and has provided the foundation for an in

tricate segregated public school system, in accord with so

cial customs which cannot be changed overnight without

5

completely upsetting established school administrative pro

cedure in school planning, transportation, teacher employ

ment, capital outlay, districting, scholastic standards, pub

lic health, school discipline as well as many other facets of

the tremendously complicated school structure in Florida.

Assuming that the basic law of Florida pertaining to a

dual system of schools (Art. XII, Section 12, of the Florida

Constitution) is rendered nugatory by the decision of this

court in the Brown case, the Florida legislature must re

vise the entire School Code of Florida to the extent that the

present code is predicated upon a dual system of education,

and all administrative procedures which have developed

under said code are grounded on the fundamental principle

of a segregated system. A simple repeal of the various

statutory and administrative procedures now provided for

the operation of the school system (which may prove to be

in conflict with the Brown decision) could only result in the

creation of a vacuum in methods of school administration.

The consequent immediate inrush of turbulent ideas into

this vacuum without legal guidance or administrative regu

lation might well cause a tornado which would devastate

the entire school system.

This system has grown through the years since the es

tablishment of the “ separate but equal” doctrine by the

Court in the Plessy v. Ferguson case (163 U.8. 537), into

a mammoth and intricate system of public education in

Florida involving the annual expenditure of $138,895,123.15

and the welfare of 650,285 children. We do not believe that

this system, which took over half a century to develop, can

be transformed overnight.

The bare mechanical process of enacting legislation re

quires reasonable time for study by legislative committees,

the time depending upon the complexity of the problem, and

must conform to the legally established time for convening

the legislature. On a problem of the magnitude of the one at

6

issue, the study of legislative committees must be preceded

by exhaustive study on the part of school officials and citi

zens’ educational committees in order that the legislature

may have the benefit of their recommendations.

I. EXAMPLES OF LEGISLATIVE. PROBLEMS

(a) Scholarships

An example of the type of legislative problem which must

be considered by school officials and the legislature is con

tained in Section 239.41, Florida Statutes.1

This law at present provides for 1,050 scholarships of

$400 each year for students desiring to train for the teach

ing profession.1 2

According to the State Department of Education, award

ing of the scholarships is done on a basis of county repre

sentation, race, and competitive test scores of psychological

and scholastic aptitude. A compilation of the scores of the

740 white twelfth grade applicants in the Spring of 1954

yielded an average score of 340. Compilation of the 488

Negro twelfth grade applicants yielded an average score

of 237. In the previous year, 1953, 664 white applicants

made an average score of 342 while the Negro applicants

made an average score of 237. This difference is classified as

very significant, and should be interpreted as meaning that

factors other than chance explain the different results be

tween white and Negro scores.

In view of the wide divergence in achievement levels be

tween the white and Negro races, as demonstrated by the

scholarship examinations, and desiring to make these schol

arship opportunities available to students of both races, it

1. See page 218, Appendix B.

2. See page 235, Appendix B.

7

was recognized that provision would have to be made

whereby Negro students would not have to compete against

white students for these awards. Therefore, the legislature

of Florida provided that the scholarships should be ap

portioned to white and Negro applicants according to the

ratio of white and Negro population in the counties. Only

in this way can Negro students in this state be assured of

receiving a proportionate share of state scholarships

awarded on the basis of competitive examinations.

If the Court’s decision in the Brown case is to be inter

preted that no distinction can be made on the basis of race

in the operation of Florida’s school system, it is apparent

that Section 239.41, Florida Statutes, will have to be re

vised if the state is to continue its policy of encouraging

Negro as well as white students to enter the teaching field.

It is apparent that the overall problem of teacher short

ages cannot be solved immediately by law. It can be solved

eventually by provisions such as Section 239.41, Florida

Statutes, which is calculated to encourage a larger number

of people to qualify themselves as teachers. If Section

239.41, Florida Statutes, is revised, however, to preclude

immediately any recognition of a difference in scholastic

achievement between Negro and white applicants for teach

er scholarships, such revision would make it virtually im

possible for the great majority of Negro students in

Florida to receive scholarships, and from an economic stand

point they form the group of potential teachers who need

such assistance most.

The problem can be solved, however, by time, without

working an undue hardship on Negro students or creating

an even greater shortage of teachers in Florida.

Dr. Gilbert Porter, Executive Secretary of Florida State

Teachers Association had this to say on the subject in

addressing a meeting of Negro teachers in Tallahassee on

August 19, 1954:

8

“ It is of no avail to blind ourselves to tbe marked

difference in scholastic achievement between white and

Negro students. This difference is not our fault, but it

is there and must be recognized. I f the doors to the

state white universities were thrown open to Negro

students today, it would make little difference because

a great majority of Negro students could not pass an

impartial entrance examination. We, as Negro teach

ers, can provide the only solution to this dilemma if

given a reasonable amount of time, but it will mean an

absolute dedication to his work on the part of every

Negro teacher. Negro teachers can close the gap be

tween Negro and white students if they will work hard

enough. We have come a long way already in closing

that gap and it can be closed completely within the

foreseeable future if we will work hard enough. Any

Negro teacher who is not willing to dedicate himself to

this purpose should step out of the way because he is

standing in the way of the progress of our race. Either

we must remove this difference in scholastic standing

or admit that we are inferior—and I will die and go

to the hot place before I will ever admit that I am

inferior. ’ ’

Whatever is done by school officials and the Florida

legislature to fit the Florida teacher scholarship act (Sec.

239.41, Florida Statutes) into the framework of the new

concept of a non-segregated school system enunciated by

the Court, should take into consideration the human rights

and legal equities of members of the Negro race who would

like to enter the one professional field which is now open to

them on a large scale, and which they are now not only

invited but urged to enter on a basis of absolute economic

and professional equality. A strict legal application of the

principle that no distinction can be made on the basis of

race in public schools would necessarily have to ignore

practical and human factors as they now exist which are

of fundamental importance to the operation of a public

school system in Florida. One thing is apparent. No equi

9

table and workable solution can be found unless sufficient

time is permitted by tbe Court in the application of its

decree abolishing segregated schools, to allow for an abate

ment of the problems involved and an equitable adjustment

by the school system to so drastic a change in its basic

structure.

(b) Powers and. Duties of County School Boards

The problems which will necessarily confront the Florida

legislature in revising the provision of Section 230.23,

Florida Statutes,1 alone, are so involved and complicated

if practical questions of school administration are to be

considered, that no immediate solution is feasible.

Section 230.23, Florida Statutes, provides the powers and

duties of county school boards and establishes a framework

within which they may authorize schools to be located and

maintained. It provides in part:

“ Authorize schools to be located and maintained in

those communities in the county where they are needed

to accommodate as far as practicable and without un

necessary expense all the youth who should be entitled

to the facilities of such schools, separate schools to

be provided for white and Negro children; and approve

the area from which children are to attend each such

schools, such area to be known as the attendance area

for that school . . . ”

Bearing in mind that this provision of the law has been

followed throughout the development of the Florida school

system and the location of schools decided in accord with its

intent, a simple repeal of this provision would provide no

systematic guide or formula for local school boards to fol

low in attempting to redesign and reorganize the dual sys

1. See page 217, Appendix B.

10

tem now in operation, which at present involves real estate

estimated to he valued at $300,000,000 and a current build

ing program now under way involving from $90,000,000 to

$100,000,000/ into a single non-segregated system.

The conversion of this $300,000,000 school plant into a

non-segregated system will clearly take a great deal of

planning if the old primary factor of racial segregation is

removed in school location, construction and operation.

The State Department of Education reports1 2 that:

“ Florida provides annually $400 per instruction unit

for Capital Outlay needs which for the 67 counties

totaled $9,451,600 in 1953-54 and has been computed

at $10,199,448 for the 1954-55 estimate. This money is

spent in each county according to the needs recom

mended by a state-conducted school building survey.

With the help of these individual county surveys it was

estimated as of January, 1954 that $97,000,000 will be

needed to provide facilities for white children and

$50,000,000 will be needed to provide facilities for

Negro children. Since the activation as of the effective

date January 1, 1953 of a Constitutional Amendment

providing for the issuance of revenue certificates by

the State Board of Education against anticipated state

Capital Outlay funds for the next thirty years more

than $43,000,000 in state guaranteed bonds have been

issued to provide additional facilities for both races.

By the fall of 1954 there will have been a total of $70,-

000,000 of these bonds issued and in the foreseeable

future the total will be $90,000,000 to $100,000,000. At

the present time 2182 classrooms are under construc

tion as a result of the issuance of these bonds.”

The planning included in making necessary surveys, ac

quisition of sites, financing and engineering involved in the

present construction program, although performed at top

speed under the compulsion of a critical shortage of school

1. See page 188, Appendix A.

2. See page 187, Appendix A.

11

buildings in Florida, is a continuing process and requires

several years to carry out successfully.

Much of this school planning with regard to the allocation

and use of existing structures as well as new construction

will have to be re-evaluated and revised in accord with the

entirely new and basic change to a non-segregated system.

These facts, when considered in the light of the over

crowded conditions now prevailing in many Florida schools,

must be studied by the legislature and school officials in any

effort to provide adequate administrative means of comply

ing with the Court’s decision. According to the State De

partment of Education, during the school year 1953-54,

eighty-one schools in 18 Florida counties were forced to

operate double sessions because of the lack of classroom

space and trained teachers. In many instances to integrate

immediately in particular schools would mean overcrowd

ing of school facilities resulting in serious administrative

problems too numerous to detail.

When these problems are further complicated by the

drastic change in the legal framework of segregated schools

in Florida, it is apparent that such factors should be rec

ognized by the Court and sufficient time allowed for their

orderly solution.

(c) State Board of Education and State Superintendent

A third example of the complex problems which will con

front school officials and the Florida legislature in re

vising the framework of laws within which the school sys

tem can operate efficiently in compliance with the Brown

decision is found in Sections 229.07,1 229.08,1 2 Florida Sta

tutes, relating to the authority and rule-making powers

1. See page 215, Appendix B.

2. See page 216, Appendix B.

12

and duties of the State Board of Education; and Sections

229.16s and 229.173 4 relating to the duties of the State

Superintendent of Public Instruction.

Although these provisions may not directly relate to seg

regated schools, they have in each instance been enacted

and administered in accord with the basic provision of

Florida law requiring a dual school system, and some re

vision will be necessary in the administrative powers

granted therein in order to insure compliance with the

Court’s decree.

Specific problems in this regard are found in State Board

Regulations adopted April 27, 1954 (page 154, State Board

Regulations, page 219, Appendix B) related to the calcu

lation of instruction units and salary allocations from the

Foundation Program; State Board Regulation adopted

March 21, 1950 (page 164, State Board Regulations, page

220, Appendix B), related to Administrative and Special

Instructional Service; State Board Regulation adopted

March 21, 1950 (page 171, State Board Regulations, page

221, Appendix B), related to units for supervisors of in

struction; State Board Regulation adopted July 3, 1947

(page 28, State Board Regulations, page 226, Appendix

B), related to School Advisory Committees; State Board

Regulation adopted March 21, 1950 (page 148, State Board

Regulations, page 228, Appendix B), related to the quali

fications, duties and procedure for employment of super

visors of instruction; State Board Regulation adopted July

3, 1947 (page 156, State Board Regulations, page 232, Ap

pendix B), related to isolated schools, State Board Regu

lation adopted July 21, 1953 (page 225, State Board Regu

lations, page 235, Appendix B), related to the distribution

of general scholarships; State Board Regulation adopted

July 3, 1947 (page 229, State Board Regulations, page 242,

Appendix B), related to State Supervisory Services.

3. See page 216, Appendix B.

4. See page 217, Appendix B.

13

n . DISCUSSION OF LEGISLATIVE ATTITUDES

In setting out these examples of legislative problems

which will require reasonable time for solution, we do not

intend to imply that the members of the Florida legislature

are at present willing to accept a desegregated school sys

tem. In fact, from such information as is now available on

this point there is reason to believe that members of the

Florida legislature are to a large extent unsympathetic

to the Court’s decision in the Brown case. A survey of

leadership opinion regarding segregation in Florida con

ducted by the Attorney General included the following

statement in the survey report (page 126, Appendix A ) :

“ Although the 79 members of the state legislature who

returned questionnaires constitute almost 45% of the

176 legislators and legislative nominees, to whom the

forms were sent, generalizations as to the entire mem

bership of the legislature on the basis of their responses

are entirely unwarranted. Any attempt to predict the

action of the legislature at its next session would be

even more presumptuous. The responses of these legis

lators to two special questions asked of them are pre

sented below as a matter of interest, however.

“ The legislators were asked to indicate which of five

possible courses of action should be followed at the

next session of the legislature. The percentage check

ing each course, and the details of the five courses of

action, are shown in Table 20 (Appendix A). The legis

lators were also asked whether they believed that there

is any legal way to continue segregation in Florida

schools indefinitely. Of the 79 respondents, 34.20% re

plied ‘ yes’, 25.31% replied ‘ no’ and 39.32% answered

‘Don’t know’ or gave no answer.”

Table 20, Appendix A, indicates that 40.5% of the mem

bers of the legislature who responded to the questionnaire

wanted to preserve segregation indefinitely by whatever

means possible.

14

It is even more significant that the Florida legislature in

its 1951 session amended the appropriations act for the

State Universities to provide that in the event Section 12

of Article 12 of the Florida Constitution shall be held un

constitutional by any court of competent jurisdiction or in

the event the segregation of races as required by Section

12, Article 12 of the Florida Constitution should be dis

regarded, that no funds under the appropriations act shall

be released to the Universities (page 683, Journal of the

Florida House of Representatives, May 10, 1951). This

amendment contained in Chapter 26859, General Laws of

Florida, 1951, was vetoed by the Governor.

On the other hand, it is not our purpose to imply that the

Florida legislature will refuse to take any action to provide

a framework of laws designed to implement the Court’s

decision. Only the legislature itself under our form of gov

ernment can determine what course of action it will pursue

and we know of no way it can be coerced in making this

determination except through the will of a majority of the

people voiced through the ballot.

One thing seems apparent, however, under these cir

cumstances. The Court upon equitable principles ought to

extend to our legislature a reasonable period of forbearance

during which the normal processes of legislative authority

can be afforded time and opportunity to implement the

Court’s decision. The great multitude of problems the de

cision has created in the legal structure of our school system

should warrant the Court in granting our legislature full

opportunity to revise our school laws.

Such a period of forbearance is in keeping wuth the

spirit of confidence which, under our system of democracy,

is essential to maintain among the three branches of gov

ernment. It is in keeping with the spirit of confidence

which must be maintained between state governments and

the Federation of States which has delegated to this Court

15

its judicial authority. A fundamental precept in the prac

tical workings of this spirit of confidence is the use of per

suasion rather than coercion or compulsion. We believe

that this Court will not attempt to use its powers of coer

cion precipitately and prematurely against any state whose

legislature has not had time to revise its basic school laws

to meet the requirements of transition.

Our Florida legislature under our Constitution does not

convene again until April, 1955 for its biennial 60-day ses

sion.

Even at that session there may not be known the terms

of the implementation pattern, since they are dependent

upon whether the Court acts prior to April, 1955. Further

more, whether the necessary spade-work and drafting of

legislation to adequately provide for the transition can be

accomplished within said session is largely a matter of

conjecture, so multitudinous and complex are the problems.

We reiterate: the State, having so long relied on and lived

under the Plessy doctrine, should have no unseemly haste

visited upon its legislature in trying to meet the needs of

transition, especially when it is considered by many to be,

at best, a “ bitter pill” for the legislature to swallow.

Rather, the reasonable, considerate and tempered course

would be to allow our legislature a requisite and ample

period of time to study, debate and enact implementation

legislation. This we believe the court from innate principles

of equity will allow.

16

B. The Need For Time In

Revising Administrative

Procedures

In addition to the problem, of statutory revision, the

Court should consider the need for time in adjusting the

literally thousands of administrative policies and regula

tions of local school boards and school superintendents

which have been formulated within the framework of law

to meet local conditions in each of the 67 counties of Florida

which will have to be revised and reorganized to conform

to new legislative enactments resulting from the Brown

decision. It is apparent that considerable time must be al

lowed before workable administrative policies of this kind

can be evolved. Speaking to a group of Negro leaders in

Jacksonville on July 30, 1954, Florida State School Super

intendent Thomas I). Bailey, said:

“ As I see it, the ultimate problem is to establish a

policy and a program which will preserve the public

school system by having the support of the people. No

system of public education will endure for long without

public support. No program of desegregation in our

public schools can be effective, unless the people in

each community are in agreement in attempting it. ’ ’

School board members, school trustees and school super

intendents are elective officials in Florida. They are ob

viously well aware that any administrative policies they

adopt implementing state laws enacted pursuant to the

Brown decision must meet with at least some degree of ac

ceptance on the part of the people in the community if they

are to prove workable.

17

I. EXAMPLES

(a) Transportation

Perhaps the best example of this type of problem is the

practical difficulties which will be encountered in convert

ing the present dual school bus transportation system into

a single system.

During the school year 1953-54 Florida’s school system

operated 2212 buses. These buses traveled 30,910,944 miles

to transport 209,492 pupils at a cost of $4,506,667 (see page

186, Appendix A). These figures may be compared with

Florida Greyhound Lines, the largest motor bus common

carrier in Florida, which operates 175 buses in the state.

A court order merging Florida Greyhound Lines with a

competing line would necessarily allow a considerable pe

riod of time for revising routes and schedules to avoid dupli

cation and insure maximum service to the public, but such

a merger would be relatively uncomplicated compared to

the problems involved in merging Florida’s dual school bus

system.

The problems of merging what amounts to two bus sys

tems into one system without regard to race are obviously

complicated. Hundreds of bus routes and schedules will

have to be revised in line with the school redistricting which

must take place. In accomplishing such a drastic revision of

bus routes and schedules the paramount factor in school

bus transportation, i.e., safety, must be considered at all

times in the light of the fact that discipline among the pas

sengers is directly related to safety. Discipline on school

buses is maintained by one person, the driver. The ability

of the driver to maintain discipline and a reasonable degree

of safety while transporting mixed racial groups which

may be antagonistic must clearly be considered in rê

routing and re-scheduling school bus routes. Such consider

ation on the part of local school boards will require degrees

18

of time in direct ratio to the complexity of the local situa

tion in relation to the size and distribution of the Negro

population and the intensity of opposition to desegregated

schools on the part of the citizens.

(b) Redistricting

The redistricting of school attendance areas along normal

geographic lines on the basis of a single school system

rather than a dual system as it now exists is another prob

lem which will require a great deal of time in proper plan

ning and execution.

(c) Scholastic Standards

Perhaps an even greater problem which will confront

school officials on both the state and county level is the

maintenance of scholastic standards in the intermingling of

two groups of students so widely divergent on the basis of

achievement levels. According to the State Department of

Education (see page 190, Appendix A ) :

“ A comparison of the performance of white and

Negro high school seniors on a uniform placement-test

battery given each spring in the high schools through

out the State of Florida is shown in Table 4, page 196,

Appendix A. The number of participants corresponds

with the total twelfth grade membership during the

five-year period, 1949-1953. This table shows, for ex

ample, that on all five tests 59% of the Negroes rank

no higher than the lowest 10% of the whites. On the

general ability scale, the fifty percentile or mid-point

on the white scale corresponds with the ninety-five

percentile of the Negro scale. In other words, only 5%

of the Negroes are above the mid-point of the white

general ability level. Studies of grades at the Univer

sity of Florida indicate that white high school seniors

with placement test percentile ranks below fifty have

less than a 50% likelihood of making satisfactory

grades in college. While factors such as size of high

19

school, adequacy of materials, economic level, and home

environment are recognized as being contributing fac

tors, no attempt is made here to analyze or measure

the controlling factors.”

In some large schools it is possible to divide students in

the same age groups into different classes, taking into con

sideration their achievement level, but smaller schools do

not have sufficient classroom space or teachers to make

such a division possible. In the latter class of schools it is

clear that an immediate and arbitrary intermingling of

students falling into such widely divergent achievement

level groups could only result in lowering the scholastic

standards of the entire school and adding to the problems

of discipline and instructional procedures. The Negro stu

dents would suffer if compelled to compete against white

students of the same age but whose achievement level was

2 or 3 grades higher and the white students would be

seriously retarded.

This problem is not insoluble and it is not advanced as a

reason for permanent segregation in the schools. It is, how-

} ever, a problem which must be taken into consideration by

school officials in any attempt at integration of the races

in the schools and it is a problem which will require careful

planning, new techniques, and a great deal of time if it is

to be solved without doing serious harm to both races and

to the school system.

Still another example of school administrative problems

in achieving an integrated school system is related to

health and moral welfare. Writing in the Eeaders Digest,

September, 1954, page 53, Mr. Hodding Carter, Editor and

Publisher of the Delta Democrat Times, Greenville, Miss

issippi, said:

Health and Moral Welfare

20

“ If only because of economic inequalities, there is a

wide cultural gap between Negro and white in the

South, and especially in those states where dwell the

most Negroes. These heavily Negro states are also

largely agrarian. Among the rural and small-town Ne

groes, the rates of near-illiteracy, of communicable

diseases, of minor and major crimes are far higher

than among the whites. The rural Negro’s living stand

ards, though rising are still low, and he is still easy

going in his morals, as witness the five to ten times

higher incidence of extramarital households and ille

gitimacy among Negroes than among whites in the

South. The Southern mother doesn’t see a vision of a

clean scrubbed little Negro child about to embark on a

great adventure. She sees a symbol of the cultural lags

of which she is more than just statistically aware.”

Specifically, with regard to Florida, the State Board of

Health reports that during the year 1953 there was a total

of 58,262 white births in the state,* of which 1,111 were ille

gitimate. During this same period there was a total of

21,825 Negro births of which 5,249 were illegitimate. Per

centagewise, this means that 1.9% of white births in Florida

during 1953 were illegitimate and 24% of Negro births

were illegitimate1.

According to the State Board of Health there was a total

of 11,459 cases of gonorrhea reported in Florida during

1953 of which 10,206 were among the Negro population.1 2

We feel that this cultural gap should be honestly recognized

by both white and Negro leaders as a problem requiring

time for solution rather than an arbitrary and blind refusal

to admit that it exists or that it is related to public school

administration.

1. Annual Report, Florida State Board of Health for 1953, Sup

plement No. 1, Florida Vital Statistics.

2. Annual Report, Florida State Board of Health 1953, Supple

ment No. 2, Florida Morbidity Statistics 1953, Table No. 5,

page 25.

21

C. The Need For Time

In Gaining Public Acceptance

There is a need for time in gaming public acceptance of

desegregation because of the psychological and sociological

effects of desegregation upon the community.

I. A SURVEY OF LEADERSHIP OPINION

A sincere and exhaustive effort has been made by the

Attorney General of Florida to ascertain, as accurately as

possible, the feelings of the people of Florida with regard

to segregation in public schools. This survey was author

ized by the Florida Cabinet which allocated $10,000 for the

purpose. This effort was made primarily for the purpose

of obtaining information which would be of use to the

Court in formulating its final decree in the Brown case.

In making the survey and study, every possible precau

tion was taken to insure its impartiality and scientific ac

curacy. It was made with the advice and under the supervi

sion of an interracial advisory committee composed of in

dividuals chosen on the basis of their professional standing

in the field of education; specialized knowledge which would

be helpful in making such a study; reputation for civic

mindedness and impartiality and because they were will

ing to devote their time without pay in carrying out a task

so enormous in scope in the brief time available. A more

detailed explanation of the scientific methods and tech

niques employed in making this study is given with the

23

complete survey report itself, which is made a part of this

brief and included as Appendix A. The General Conclusions

of this report are as follows:

IL GENERAL CONCLUSIONS

1. On the basis of data from all relevant sources in

cluded in this study, it is evident that in Florida white lead

ership opinion with reference to the Supreme Court’s de

cision is far from being homogeneous. Approximately

three-fourths of the white leaders polled disagree, in prin

ciple, with the decision. There are approximately 30% who

violently disagree with the decision to the extent that they

would refuse to cooperate with any move to end segregation

or would actively oppose it. While the majority of white

persons answering opposed the decision, it is also true that

a large majority indicated they were willing to do what

the courts and school officials decided.

2. A large majority of the Negro leaders acclaim the

decision as being right.

3. Only a small minority of leaders of both races advocate

immediate, complete desegregation. White leaders, if they

accept the idea that segregation should be ended eventually,

tend to advocate a very gradual, indefinite transition period,

with a preparatory period of education. Negroes tend to ad

vocate a gradual transition, but one beginning soon and last

ing over a much shorter period of time.

4. There are definite variations between regions, coun

ties, communities and sections of communities as to whether

desegregation can be accomplished, even gradually, with

out conflict and public disorder. The analysis of trends

in Negro registration and voting in primary elections,

shows similar variations in the extent to which Negroes

have availed themselves of the right to register and vote. At

least some of these variations in voting behavior must be ac

24

counted for by white resistance to Negro political participa

tion. This indicates that there are regional variations not

only in racial attitudes but in overt action.

Eegional, county and community variations in responses

to questionnaires and interviews are sufficiently marked to

suggest that in some communities desegregation could be

undertaken now if local leaders so decided, but that in

others widespread social disorder would result from im

mediate steps to end segregation. There would be prob

lems, of course, in any area of the state, but these would

be vastly greater in some areas than in others.

5. While a minority of both white and Negro leaders

expect serious violence to occur if desegregation is at

tempted, there is a widespread lack of confidence in the

ability of peace officers to maintain law and order if serious

violence does start. This is especially true of the peace offi

cers themselves, except in Dade County. This has im

portant implications. While it is true that expressed

attitudes are not necessarily predictive of actual behavior,

there seems little doubt that there is a minority of whites

who would actively and violently resist desegregation,

especially immediate desegregation. It has been concluded

from the analysis of experiences with desegregation in

other areas, “ A small minority may precipitate overt re

sistance or violent opposition to desegregation in spite of

general acceptance or accommodation by the majority.” 1

6. Opposition of peace officers to desegregation, lack of

confidence in their ability to maintain law and order in the

face of violent resistance, and the existence of a positive

relationship between these two opinions indicates that less

than firm, positive action to prevent public disorder might

be expected from many of the police, especially in some

communities. Elected officials, county and school, also show

1. Kenneth B. Clark, “ Findings,” Journal of Social Issues, IX ,

No. 4 (1953), 50.

25

a high degree of opposition. Yet it has been pointed out,

again on the basis of experience in other states, that the

accomplishment of efficient desegregation with a minimnrn

of social disturbance depends upon:

A. A clear and unequivocal statement of policy by

leaders with prestige and other authorities;

B. Firm enforcement of the changed policy by author

ities and persistence in the execution of this policy

in the face of initial resistance;

C. A willingness to deal with violations, attempted

violations, and incitement to violations by a resort

to the law and strong enforcement action;

D. A refusal of the authorities to resort to, engage in

or tolerate subterfuges, gerrymandering or other

devices for evading the principles and the fact of

desegregation;

E. An appeal to the individuals concerned in terms of

their religious principles of brotherhood and their

acceptance of the American traditions of fair play

and equal justice.

It may be concluded that the absence of a firm, enthusi

astic public policy of making desegregation effective would

create the type of situation in which attitudes would be

most likely to be translated into action.1

7. In view of white feelings that immediate desegregation

would not work and that to require it would constitute a

negation of local autonomy, it may be postulated that the

chances of developing firm official and, perhaps, public sup

port for any program of desegregation would be maximized

by a decree which would create the feeling that the Court

recognizes local problems and will allow a gradual transi

tion with some degree of local determination.

8. There is a strong likelihood that many white children

would be withdrawn from public schools by their parents

1. Experience shows that where the steps listed above have been

taken, predictions of serious social disturbances have not been

borne out.

26

and sent to private schools. It seems logical, however, that

this practice would be confined primarily to families in the

higher income brackets. As a result, a form of socio

economic class segregation might be substituted for racial

segregation in education.

9. It is evident that a vast area of misunderstanding as

to each other’s feelings about segregation exists between

the races. White leaders believe Negroes to be much more

satisfied with segregation than Negroes are and Negro

leaders believe that whites are much more willing to accept

desegregation gracefully than whites proved to be. Hence

a logical first step towards implementing the principle set

forth by the Court, and one suggested by both whites and

Negroes, would seem, to be the taking of positive, coopera

tive steps to bridge this gap and establish better under

standing between the two groups.

10. Although relatively few Negro leaders and teachers

show concern about the problem, white answers indicate

that Negro teachers would encounter great difficulty in

obtaining employment in mixed schools. To the extent that

desegregation might proceed without parallel changes in

attitudes towards the employment of Negro teachers in

mixed schools, economic and professional hardships would

be worked on the many Negro teachers of Florida.

11. Since 1940, and particularly since 1947, the State of

Florida has made rapid and steady progress toward the

elimination of disparities between white and Negro edu

cational facilities as measured by such tangible factors as

teacher salaries, current expenditure per pupil, teacher

qualifications, and capital outlay expenditure per pupil.

12. In spite of the current ambiguity as to the future of

dual, “ separate but equal” school facilities the State is pro

ceeding with an extensive program of construction of new

school facilities for both white and Negro pupils, with a

27

recommended capital outlay of $370 per Negro pupil and

$210 per white pupil. Both this and the previous finding in

dicate that, while these steps have been taken within the

framework of a dual educational system, there is a sincere

desire and willingness on the part of the elected officials

and the people of Florida to furnish equal education for all

children.

13. Available achievement test scores of white and Ne

gro high school seniors in Florida indicate that, at least in

the upper grades, many Negro pupils placed in classrooms

with white pupils would find themselves set apart not only

by color but by the quality of their work. It is not implied

that these differences in scores have an innate racial basis,

but it seems likely that they stem from differences in eco

nomic and cultural background extending far beyond the

walls of the segregated school, into areas of activity not

covered by this decision.

14. Interracial meetings and cooperative activities al

ready engaged in by teachers and school administrators in

many counties demonstrate steps that can be, and are being

taken voluntarily and through local choice to contribute to

the development of greater harmony and understanding

between whites and Negroes in Florida communities.

The specific findings of this survey regarding leadership

opinion as expressed through mailed questionnaires are:

1. White groups differ greatly from each other in

their attitudes towards the Court’s decision, ranging

from nearly unanimous disagreement to a slight pre

dominance of favorable attitudes. (See Table 2, page

136, Appendix A)

2. White groups also differ from each other in will

ingness to comply with whatever courts and school

boards decide to do regardless of their personal feel

ings. (See Table 4, page 139, Appendix A)

3. Peace officers are the white group most opposed

to desegregation. (See Table 3, page 138, Appendix A)

28

4. Almost no whites believe that desegregation

should be attempted immediately. (Table 2, page 136,

Appendix A)

5. A large majority of both Negro groups are in

agreement with the Court’s decision declaring segre

gation unconstitutional. (Table 3, page 138, Appendix

A)

6. While only a small minority of both Negro groups

believe that desegregation should be attempted imme

diately, an even smaller minority would oppose at

tempts to bring about desegregation or refuse to co

operate. (Table 2, page 136, Appendix A)

7. Only a minority of whites in all groups believe

that opponents of desegregation would resort to mob

violence in trying to stop it. A larger proportion, but

still a minority, believe that serious violence would re

sult if desegregation were attempted in their commu

nity in the next few years. (Table 5, page 140, Ap

pendix A)

8. A yet smaller minority of both of the Negro

groups anticipate mob violence or serious violence as

a result of steps towards desegregation. (Table 5,

page 140, Appendix A)

9. The majority of all white groups are not sure that

peace officers could cope with serious violence if it

did occur in their communities, replying either “ no”

or “ don’t know” to the question. (Table 6, page 141,

Appendix A)

10. A much smaller proportion of both Negro groups

expresses doubt as to the ability of law enforcement

officials to deal with serious violence. (Table 6, page

141, Appendix A)

11. The majority of most of the white groups believe

that peace officers could maintain law and order if

minor violence occurred. (Table 7, Appendix A)

12. The Negro groups did not differ greatly from the

white groups in the proportion believing that police

could cope with minor violence. (Table 7, Appendix A)

29

13. Only 13.24 per cent of 1669 peace officers believe

that most of the peace officers they know would en

force attendance laws for mixed schools.

14. A majority of the members of all white groups

except peace officers, (who were not asked): radio sta

tion managers; and ministers, believe that most of the

people of Florida and most of the white people in their

communities disagree with the Court’s decision. (Table

8, Appendix A)

15. In the five white groups asked, from one-fourth to

one-half of the respondents believed that most of the

Negroes in their community were opposed to the de

segregation ruling. (Table 8, Appendix A)

16. A much smaller proportion of both Negro groups

believe that most of the people of Florida, most of the

whites in their community, and particularly the Negroes

in their communities are in disagreement with the prin

ciple of desegregation. (Table 8, Appendix A)

17. Only a small minority of all groups, white and

Negro believe that immediate assignment of children

to schools on the basis of geographical location rather

than race would be the most effective way of ending

public school segregation. (Table 9, Appendix A)

18. All groups think a gradual program of desegre

gation would be most effective. Negroes, however, pre

fer that the process start within the next year or two

with immediate, limited integration much more fre

quently than do whites. The whites prefer a very grad

ual transition with no specified time for action to begin.

(Table 9, Appendix A)

19. Whites who expressed an opinion believe that the

primary grades and the colleges are the levels on which

desegregation could be initiated most easily. On the

other hand, almost as many Negroes believed that

segregation should be ended on most or all grade levels

simultaneously as believed it should be ended first at

the lowest and highest grade levels.

20. The maintenance of discipline in mixed classes by

Negro teachers is regarded as a potential problem by a

30

majority of white principals, supervisors and FT A

leaders. A much smaller proportion of Negroes re

garded this as a problem, with a majority of Negro

principals believing that colored teachers could main

tain discipline in mixed classes. (Table 11, Appendix

A)

21. A majority of all white groups believe that white

people would resist desegregation by withdrawing

their children from the public schools, but a much

smaller proportion of Negroes, less than a majority

believe that this would happen. (Table 11, Appendix A)

22. Almost two-thirds of white school officials—su

perintendents, board members, and trustees—believe

that application of Negroes to teach in mixed schools

would be rejected. (Table 11, Appendix A)

It should be noted at this point that this opinion is sup

ported by the experience of other states where desegrega

tion of schools has already taken place. The August 27,1954,

issue of U. S. News and World Report, page 35, states,

“ In the north, protests from white parents tend to drive

Negro teachers out of the schools to which their children go.

The same thing is expected in the South when desegregation

comes to the schools there. An illustration of what happens

in the North is shown by the experience of Jeffersonville,

Indiana. The town lies in the southern part of the State,

just across the Ohio River from Kentucky. A great deal of

Southern tradition and many Southern customs have

reached across the river. Jeffersonville is just completing

desegregation of its schools. There have been few un

happy incidents. But there has been a greater problem with

teachers than with children in the schools. There were 16

Negro teachers in Jeffersonville when desegregation was

started in 194.8. By 1951 their number had dwindled to

11 as school enrollments were consolidated. For the school

year starting in autumn, 1951, only three Negro teachers

were retained. They had achieved permanent tenure under

State laiv, and could be discharged only for cause.”

31

Florida now employs 19,848 persons in instructional po

sitions not including supervisors. 4,721 of these teachers

are Negroes. (Biennial Report, Superintendent of Public

Instruction, State of Florida, 1950-51)

23. Nearly three-fourths of school officials believe

that it would be difficult to get white teachers for

mixed schools. (Table 11, Appendix A)

24. Almost half of school officials and a little over

40% of white PTA leaders believe that the people of

their communities would not support taxes for desegre

gated schools, but only about 20% of Negro PTA lead

ers believe that such support would not be forthcoming.

(Table 11, Appendix A)

25. In the case of all potential problems on rvhich

both Negroes and whites were questioned a smaller

proportion of Negroes than of whites indicate belief

that problems would arise as a result of desegregation.

(Table 11, Appendix A)

26. In the case of peace officers there is a positive

relationship between personal disagreement with the

decision and lack of confidence in the ability of peace

officers to cope with serious violence. There is an even

higher positive relationship between belief that segre

gation should be kept and belief that peace officers

would not enforce school attendance laws for mixed

schools. (Table 12, Appendix A)

Regional Variations. The responses to certain items of

the two largest groups polled, the peace officers and the

white school principals and supervisors, were analyzed by

region of the state in which the respondents lived. The 67

counties of Florida were grouped into 8 regions defined by

social scientists at the Florida State University in “ Florida

Facts” (Tallahassee, Florida; School of Public Adminis

tration, The Florida State University).

Clear-cut regional variations in attitudes and opin

ions are found to exist, as is indicated by the following

findings;

32

27. Although the majority of peace officers in all

regions feel that segregation should be kept, the per

centage feeling so varies from 83% in two regions to

100% in one region. (Table 14, Appendix A)

28. The percentage of white principals and super

visors who are in disagreement with the decision varies

from 20% to 60% in different regions. (Table 15, Ap

pendix A)

29. A large majority of white principals and super