Former Churchill Area School District v. Hoots Brief in Opposition

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Former Churchill Area School District v. Hoots Brief in Opposition, 1981. 280ce933-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f71d44be-e03a-4fc3-a125-214be3375c13/former-churchill-area-school-district-v-hoots-brief-in-opposition. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

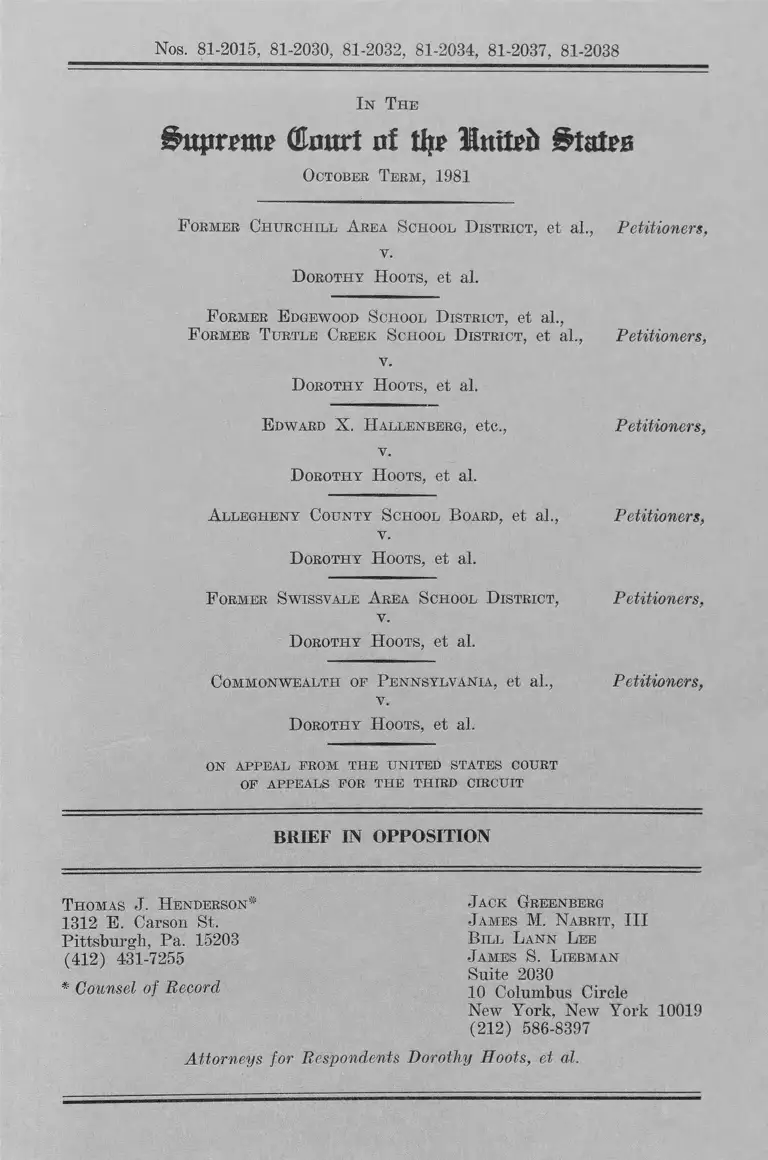

Nos. 81-2015, 81-2030, 81-2032, 81-2034, 81-2037, 81-2038

I n T h e

GJmtrt of tfj? lotted Stairs

October Teem, 1981

F ormer Churchill Area School D istrict, et al,,

v.

Dorothy H oots, et al.

F ormer E dgewood School D istrict, et al.,

F ormer Turtle Creek School D istrict, et al.,

v.

Dorothy H oots, et al.

E dward X. IIallenberg, etc.,

v .

D orothy H oots, et al.

Allegheny County School Board, et al.,v.

D orothy H oots, et al.

F ormer Swissvale Area School D istrict,v.

Dorothy H oots, et al.

Commonwealth of P ennsylvania, et al.,

v.

D orothy H oots, et al.

on appeal from t h e u n ited states court

of appeals for t h e th ird circuit

Petitioners,

Petitioners,

Petitioners,

Petitioners,

Petitioners,

Petitioners,

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

Thomas J. H enderson*

1312 E. Carson St.

Pittsburgh, Pa. 15203

(412) 431-7255

* Counsel of Record

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, I I I

B ill Lann Lee

J ames S. L iebman

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys for Respondents Dorothy Hoots, et al.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether factfindings of the two

courts below that state officials drew

boundary lines with the intent to create

separate racially segregated school dis

tricts — findings based on an extensive

evidentiary record developed during eleven

years of litigation — are clearly errone

ous?

2. Whether the lower courts abused

their discretion in ordering the consolida

tion into a single desegregated district of

five small, contiguous and segregated

school districts, when: (i) each of the

five former districts was found, a decade

before, to have been unconstitutionally

created and isolated from the others by

state, county and local officials; (i i)

the responsibile officials failed, over

the course of eight years, to present any

1

adequate alternative desegregation plan to

cure the constitutional violation; and

(iii) both courts below found that a

five-district consolidation would indis-

putedly provide students with a more

comprehensive and efficient — as well as a

desegregated -- educational program?

3. Whether the courts below abused

their discretion by initially not forcing

the former school districts to join as

defendants, against their wills, when the

districts were at all times provided a

meaningful opportunity to participate in

the proceedings, and in fact did partici

pate in the proceedings by presenting evi

dence, without limitation, on both liabil

ity and relief?

- 1 1 -

Questions Presented ................ i

Table of Authorities ............... iv

Statement .......................... 2

Reasons to Deny the Writ ........... 24

1. Findings of Intentional

Segregation ............ 25

2. The Remedy ................ 40

3. Meaningful Opportunity to

Participate ............ 54

Conclusion ......................... 60

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

- i i i -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases

Berenyi v. Information Director,

385 U.S. 630 (1 967) .......... . 38

Blau v. Lehman, 368 U.S. 403

( 1962) ......................... 38

Brown v. Board of Education,

349 U.S. 294 (1955) .......____ 37

Chartiers Valley Joint Schools v.

County Board, 418 Pa. 520,

211 A.2d 487 (1967) ............ 9,56

Columbus Board of Education v.

Penick, 443 U.S. 449

( 1979) ................... 35,37,40

Commissioner v. Duberstein, 363

U.S. 278 (1960) ................ 38

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872

(S.D. Ala.), aff'd, 336 U.S.

933 (1949) ..................... 31

Dayton Board of Education v.

Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526

(1979) ........................ 35,38

Engle v. Isaac, U.S. ,

71 L.Ed.2d 783 (1982) .......... 58

iv -

Page

Evans v. Buchanan, 582 F.2d 750 (3d

Cir. 1978) (en banc), cert, denied,

446 U.S. 923 (1980); 555 F.2d 373

(3d Cir. 1977)(en banc), cert.

denied, 434 U.S. 934 (1978); 393

F. Supp. 428 (D. Del.) (3-judge

court), aff'd, 423 U.S. 963 (1975) .................. 39,46,47

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976) ............ 51

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S.

339 ( 1960) .................... 33

Graver Mfg. Co. v. Linde Co., 336

U.S. 271 (1979) ............... 38

Green v. County School Board, 391

U.S. 430 (1968) ............... 43

Griffin v. Board of Education, 239

F. Supp. 560 (E.D. Va.

1965) ......................... 57

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Penn

sylvania (Hoots I), 334 F. Supp.

820 (W.D. Pa. 1972) ..... 3,10,28,55,56,57,58

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Penn

sylvania (Hoots II), 359 F. Supp.807 (W.D. Pa. 1973) ...... passim

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Penn

sylvania (Hoots III), 495 F.2d 1095 (3d Cir.), cert, denied,

419 U.S. 884 ( 1974) ......... passim

v

Page

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Penn

sylvania (Hoots IV), 587 F.2d

1340 (3d Giro 1978) .......... 3,6,26

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Penn

sylvania (Hoots V), 639 F.2d

972 (3d C ir. ), cert, denied,

101 S.Ct. 3113 (1981) ........ 3,17,27

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Penn

sylvania (Hoots VI), 510 F. Supp.

615 (W.D. Pa. 1981) passim

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Penn

sylvania (Hoots VII), No. 71- 538 (W.D. Pa. April 16,

1981 ) ............ 3,18,19

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Penn

sylvania (Hoots VIII), No. 71-

538 (W.D. Pa. April 28,

1981) ..................... passim

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Penn

sylvania (Hoots IX), 672 F.2d 1107 (3d Cir. 1982)........ passim

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Penn

sylvania, No. 71-538 (W.D.

Pa. May 12, 1982) .............. 53

Hoots v. Weber, No. 79-1474 (3d

Cir. May 2, 1979) .............. 4

Hoots v. Weber, No. 80-2124 (3d Cir.

Sept. 9, 1 980) ....... ......... 4

Husbands v. Commonwealth of Penn

sylvania, 359 F. Supp. 925

(E.D. Pa. 1973) ________....... 57

vi

57

Lee v. Macon County, 268 F.2d 458

(M.D. Ala.), aff'd, 389 U.S.

215 (1967) ................

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 617

(1974) ................. 39,46,47,61

Morrilton School Dist. No. 32 v.

United States, 606 F.2d 222

(8th Cir. 1979), cert, denied,

444 U.S. 1071 (1980) ___ 38,46,47

Personnel Administrator v. Feeney,

442 U.S. 256 (1979) ........... 35

Pullman Standard v. Swint, ___ U.S.

, 50 U.S.L.W. 4425 (April

27, 1982) ..................... 37

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369

(1967) ........................ 31

Rogers v. Lodge, ___ U.S. ___,

No. 80-2100 (July 1,1982) ................... 32,36,37,38

State Board of Education v. Franklin

Township School District, 209

Pa. Super. 410, 228 A.2d 221

(Pa. Super. 1967) ............. 9

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1

( 1971) ...................... 44,50

Swissvale Area School District v.

Weber, No. 73-1849 (3d Cir.

Oct. 12, 1973) ................ 26

United States v. Board of School

Commissioners, 573 F.2d 400

(7th Cir.), cert, denied,

439 U.S. 824, on remand,

456 F. Supp. 183 (1978) .... 31,34,35,

39,45,47

United States v. Johnston, 268 U.S.

220 (1925) ..................... 26

United States v. Missouri, 363 F.

Supp. 739 (E.D. Mo. 1973),

aff'd, 515 F.2d 1365 (8th

Cir.), cert, denied, 423

U.S. 951 (1975) ........ 31,39,47

United States v. United States Gypsum

Co., 333 U.S. 364 (1948) ........ 36

United States v. Yellow Cab Co.,

338 U.S. 338 (1949) ............ 38

Village of Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Develop

ment Corp., 429 U.S. 252

M977) ................ 31,33,34

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229

( 1976) ......... 35

v m

Page

Statutes and Rules

Act of September 12, 1961, P.L.

1283, No. 561, 24 P.S.

§ 2-281, et_ seq. (Act 561) .... 6

Act of August 8, 1963, P.L. 564,

No. 299, 24 P.S. §

2-290, et seq. (Act 299) ..... 6

Act of July 8, 1968, P.L.

299, No. 150, 24 P.S. § 2400-1

(Act 150) ..................... 6

Rule 24, Fed. R. Civ. Pro........... 10

Rule 52, Fed. R. Civ. Pro........... 35

Other Authorities

3A MOORE'S FEDERAL PRACTICE ........ 57

IX

Nos. 81-2015, 81-2030, 81-2032,

81-2034, 81-2037, 81-2038

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1981

FORMER CHURCHILL AREA SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

DOROTHY HOOTS, et al.

FORMER EDGEWOOD SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

FORMER TURTLE CREEK SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

DOROTHY HOOTS, et al.

EDWARD X. HALLENBERG, etc.,

Petitioners,

v.

DOROTHY HOOTS, et al

ALLEGHENY COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al

Petitioners,

v.

DOROTHY HOOTS, et al.

FORMER SWISSVALE AREA SCHOOL DISTRICT,

DOROTHY HOOTS,

Petitioners,

V.

et al.

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, et al.,

DOROTHY HOOTS,

Petitioners,

V.

et al.

On Appeal From the United States Court

Of Appeals For The Third Circuit

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

3

Statement 1/

The various petitioners are asking

this Court to review the ninth reported

2/decision in a longstanding litigation.

J_/ Citations are to the Appendix to the

Petition filed by the Commonwealth of

Pennsylvania, No. 81-2038 (hereinafter

"A." ) and portions of the Record on

Appeal set forth in the Joint Appendix in

the court of appeals (hereinafter "R.").

2/ Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylva

nia, 672 F. 2d 1107 (3d Cir. 1982) ("Hoots

IX"), A. 86a-87a n.1. The other decisions

are: Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania , 334 F. Supp. 820 (W.D. Pa. 1972)

("Hoots I" ); Hoots v._Commonwealth of

Pennsylvania, 359 F. Supp. 807 (W.D. Pa.1973) ("Hoots II"); Hoots v. Commonwealth

of Pennsylvania, 495 F.2d 1095 (3d Cir.),

cert, denied, 419 U.S. 884 (1974)("HootsIII"); Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylva

nia, 587 F. 2d 1340 (3d Cir. 1978) ("Hoots

IV" ) ; Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylva-

nia, 639 F.2d 972 (3d Cir.), cert, denied,

101 S.Ct. 3113 (1981) ("Hoots V"); Hoots v.

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 510 F. Supp. 615 (W.D. Pa. 1981) ("Hoots VI"); Hoots v.

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, No. 71-538

(W.D. Pa. April 16, 1981) ("Hoots VII");

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, No.

71-538 (W.D. Pa. April 28, 1981) ("Hoots

VIII" ).

(footnote continued on next page)

4

Plaintiffs are a class of black and

white parents of school-aged children

living in the former General Braddock Area

School District (hereinafter "General

Braddock"). Prior to 1981, General Brad-

dock was a predominately (63%) black school

district, which, together with the sur

rounding former all- or nearly all-white

districts of Churchill (99.2% white),

Edgewood (97.8% white), Turtle Creek (98.1%

white), and Swissvale (83.7% white), was

created by state and county officials

during Pennslyvania's statutorily mandated

2/ continued

In addition, the court of appeals

denied plaintiffs' applications for writs

of mandamus on two occasions. Hoots v.

Weber, No. 79-1474 (3d Cir. May 2, 1979);

Hoots v. Weber, No. 80-2124 (3d Cir. Sept.

9, 1980).

5

school district reorganizations of the

1960's.-

3/ General Braddock was created in the

1960's by combining the only preexisting

majority-black municipal school districts

in the area, Braddock (72% black) and

Rankin (51% black), with North Braddock

(16% black). Hoots II, A. 17a, 20a-21a

(1970 figures). In its first year of

operation, 1971, General Braddock was 44.5% black. By 1980-81 , the last year of its

existence, General Braddock's black pupil

population had increased to 63%. I<3. , A.

77a. After the reorganization process was

complete, no other district in the violation area — i.e. , the area consistently

referred to in the opinions below as

"central eastern Allegheny County" --

had a black pupil population approaching

General Braddock's.

"Central eastern Allegheny County"

was defined by the district court in 1973

as the area lying

east of the City of Pittsburgh and

north of the Monogahela River, [in

which] the County and State Boards

established [General Braddock] ;

the School Districts of Turtle Creek,

Swissvale Area, Churchill Area and East Allegheny which border on [Gen

eral Braddock]; and the Edgewood

School District which is situated within approximately one mile of

[General Braddock]. I_d. , A. 12a-13a.

See also, id., A. 13a-14a, 20a-22a,

6

Plaintiffs commenced this action on

June 9, 1971. The complaint alleged that

the Pennsylvania State Board of Education

and Allegheny County School Board (now the

Allegheny Intermediate Unit) (hereinafter,

"the state and county boards") deliber

ately created General Braddock, Churchill,

Edgewood, Swissvale and Turtle Creek as

separate racially segregated school dis

tricts during three statutorily mandated

school district reorganizations in the

4/1960!s. Specifically, the complaint al-

3/ continued

27a, 40a; Hoots III, 43a; Hoots IV,

supra, 587 F.2d at 1343-44; Hoots VI,

51a-53a, 55a, 62a-63a; Hoots VIII ,

73a, 76a-79a, 80a; Hoots IX, 90a-92a,

10 0 a-101 a, 105a, 108a-109a, 112a.

4/ See Act of September 12, 1961, P.L.

1283, No. 561 , 24 P.S. § 2-281, et. seq.

(Act 561); Act of August 8, 1963, P.L. 564,

No. 299, 24 P.S. § 2-290, et. seq. (Act

299); Act of July 8, 1968, P.L. 299, No.

150, 24 P.S. § 2400-1 (Act 150).

7

leged that the state and county boards,

in exercising their power to reorganize

school districts, had "compelled the for

mation of school districts which concen

trate and contain blacks in one school

district and whites in the other school

districts so as to create racially iden

tifiable school districts ... not only to

segregate [General Braddock] but the ad

joining [districts] as well." The com

plaint requested that school district

boundaries in the affected area be "al

ter [ e d ] and revise [d] " to establish a

desegregated system of schools. R. 35a,

37a. Churchill, Edgewood, Swissvale and

Turtle Creek were specifically named as the

"adjoining," or "surrounding," school

, . 5/districts. .Id. The complaint named as

5/ Petitioners have stated that the

complaint (i) made no allegation that each

of these districts was racially segregated

8

defendants the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

the state and county boards and certain of

their officers. It alleged that defen

dants unconstitutionally created General

5/ continued

(Churchill Petition, No. 81-2015, p. 6);

(ii) requested no alteration of these

school districts' boundaries (Edgewood/

Turtle Creek Petition, No. 81-2030, pp. 3,

14-15); and (iii) provided no notice of the

requested alteration of these school

district boundaries (Churchill Petition,

No. 81-2015, p. 24; Edgewood/Turtle Creek

Petition, No. 81-2030, pp. 14-15 & n.10).

Each of these statements is erroneous.

The amended complaint described

General Braddock and each of the former

white districts, R. 27a-29a, and clearly

identified all five districts as "segre

gated" and "racially identifiable school

districts" created in order to segregate

black students in General Braddock and

white students in Churchill, Edgewood,

Swissvale and Turtle Creek, R. 30a-35a.

See R. 2 0 a-3 7 a. Plaintiffs accordingly

requested injunctive relief "altering and

revising or ordering defendants to alter

and revise the school reorganization plans

..." and to "adopt immediately plans that

will create racially . . . balanced school

systems to serve the residents of [General

Braddock] and the surrounding communities."

R. 37a, 22a.

9

Braddock and the surrounding former white

districts pursuant to power conferred on

g /them by the reorganization statutes- --

specifically, their power to prepare,

review, amend, approve, and effectuate

reorganization plans, including those which

created General Braddock and the surround

ing districts. R. 21a, 26a-29a, 31a.

In December 1971, the district court

denied defendants' motions to dismiss.

The court held that plaintiffs' allegations

that, "[i]n preparing and adopting the

school reorganization plans, the defendants

intentionally and knowingly created ra-

6/ See Chartiers Valley Joint School v.

County Board, 418 Pa. 520, 21 1 A.2d 487,

491-495 (1965) (the reorganization acts

delegated legislative power to define the

geographic boundaries of school districts

to the state and county boards); State

Board of Education v. Franklin Township

School District, 209 Pa. Super. 410, 228

A.2d 221, 223-24 (1967).

10

cially segregated school districts" stated

a cause of action under the Fourteenth

Amendment. Hoots I, A. 1a™2a. At the same

time, the court declined to join General

Braddock and the former white districts as

defendants against their wills, Hoots I, A.

5a, but held that it would permit the dis

tricts to "intervene in this action under

Fed. R. Civ. P. 24 if they so desire." Id.

Although the court "instructed the [Common

wealth] to give notice" of the action to

all five former districts, and the Attorney

General of Pennsylvania thereupon directed

written and later telegraphic notices to

the five districts (with copies of the

amended complaint attached) "urg[ing each]

to intervene in this action immediately,"

the districts informed the court that they

were "deliberately not intervening in this

case" and "had no interest in being" a

- 11 -

7/party to the trial.- As Churchill states

in its petition, the districts' failure to

participate in the initial violation trial

was a considered strategic decision to stay

8/out of the litigation as long as possible.—

, , . . 9/Following trial,- on May 15, 1973, the

2/ R. 56a-61 a, 614a-18a, 272a, 3338a,

3389a. See Hoots II, A. 33a-35a; Hoots

III, A. 45a-46a.

8_/ Churchill Petition, No. 80-2015, p.

23. In its petition, Churchill quotes part of the following explanation of the dis

tricts' actions as summarized at a 1973

hearing by counsel for the Commonwealth:

There is no doubt that prudent lawyer

ing dictates what the school districts

are presently doing. Were I to be in

that situation, I think I would do the

exact same thing. I would sit back

and wait hopefully ... that the

Court's opinion ... would be to their

favor ... and, if not, at the later

date, to seek some way to attack

it .... R. 316a.

2/ At trial, plaintiffs introduced the

testimony of lay witnesses, local school

authorities, state officers and expert

witnesses. In addition, 63 documentary,

summary and graphic exhibits were intro

duced pursuant to stipulation. R. 55a-

748a.

12

district court found that the state and

county boards' intentionally segregative

creation of General Braddock as a predomi

nantly black district, and of Churchill,

Edgewood, Swissvale and Turtle Creek as

virtually all-white districts, "constituted

an act of de jure discrimination in violat

ion of the Fourteenth Amendment. " The

court concluded that "a violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment ha [d ] occurred"

because "public school authorities ... made

educational policy decisions which were

based wholly or in part on considerations

of the race of the students and which

contributed to increasing racial segrega

tion in the public schools." Hoots II,

A. 37a, 35a.

The court ordered defendants to

"prepare and submit to this Court within 45

days ... a comprehensive plan of school

desegregation for the central eastern area

13

of Allegheny County [that would] remedy

the constitutional violations found by this

Court" by "alter[ing] the boundary lines of

General Braddock ... and, as appropriate,

of adjacent and/or nearby school dis

tricts." Hoots II, A. 40a.

None of the defendants appealed.

After the May 1 973 opinion was issued,

however, Churchill and Turtle Creek re

versed their pretrial opposition to inter

vention, and attempted to intervene, asking

the court to set aside its May 1973 opin

ion. The district court denied the motions

as "untimely" insofar as they sought retro

active intervention but granted prospective

intervention, R. 966a, and the court of

appeals affirmed. Hoots III, A. 44a-46a.~'/

10/ Churchill and Turtle Creek filed a

writ of certiorari, R. 2577a, which was

denied. Churchill Area School District

v. Hoots, 419 U.S. 884 (1974).

(footnote continued on next page)

- 14 -

Defendants filed no "comprehensive

plan of desegregation" within 45 days.

Indeed, no remedy was forthcoming for the

next eight years, despite lengthy hearings

conducted by the district court and (on

remand from the district court) by the

state board. During the 1973-1981 period,

the district court not only heard evidence

and argument on remedy, but also, as the

court of appeals found, Hoots IX, A. 102a,

specifically permitted all of the peti

tioner districts to reopen and present

additional evidence on the violation

10/ continued

Contemporaneously, the former white

districts initiated several extended state court proceedings seeking to prevent

the state defendants from proposing and submitting remedial plans to the federal

district court in the instant litigation. R. 2504a, 2730a-31a.

15

issue.— ^ E . g . , R. 1486a-1506a, 2684a-

2766a, 2829a-3015a, see Hoots IX, A.

101a-02a. On each such occasion, the

district court reaffirmed its 1973 finding

of intentional segregation. R. 1031a-32a

(May 1975), 2761a-62a (October 1975), 841a

(November 1977), 3201a-02a (October 1980);

Hoots VI, A. 49a, 59a (March 1981); Hoots

VIII, A. 77a (April 1981). See Hoots IX,

A. 101a-102a.

]_ }_ / Swissvale and Churchill formally

intervened and participated fully in all of

the proceedings in this case from October

1973 to the present. Other school dis

tricts, including Edgewood and Turtle

Creek, in the district court's words,

actually "participated," but "did not [for

mally] intervene because they wished to protect their position on the record...."

R. 1031a. See n.8, supra and accompanying

text. General Braddock voluntarily inter

vened in February 1979, R. 2588a, and the

court mandatorily joined Edgewood and

Turtle Creek in May 1979. R. 853a.

During the 1973-1975 period, the

district court thrice remanded the case to

the state board for remedial hearings, the

16

The district court heard and con

sidered extensive evidence on three plans

submitted by the State and various plans

submitted by the districts -- including

Plans 22W, A, B, Z, the Tuition Plan, the

Upgrade Plan, and variations of these

, 12/plans.—

During the course of the 1973-1981 pro

ceedings in the district court and the

11/ continued

transcripts of which were made part of the

record by the district court. See R .

1128a-29a, 3194a-95a. All the petitioner

school districts participated actively in

the state board hearings. E.g., 9/10/73

St. Bd. Tr. ; 3/6/75 St. Bd. Tr.

1 2/ All six of the plans proposed by

petitioners (notably, by the Commonwealth,

Churchill, Swissvale, and Turtle Creek)

were interdistrict in nature, and all but

one of those plans included the five

former districts presently before this

Court. Similarly, all but one of peti

tioners' plans involved the consolidation

of existing districts into larger units. Hoots IX, A. 93a.

17

court of appeals, General Braddock became a

majority, and then a two-thirds, black

district. Finally, in 1981, the court of

appeals directed the district court to

complete "scope of the violation" and

remedial proceedings within three months,

and to enter a final order granting appro

priate relief beginning with the 1981-1982

school year. Hoots V, supra, 639 F.2d at

980-91. This Court denied certiorari.

Swissvale Area School District v. Hoots,

101 S.Ct. 3113 ( 1981).

On remand, the district court recon

sidered the evidence on violation adduced

not only at the initial liability trial in

1 972, but also at the numerous subsequent

hearings held between 1973 and 1981. Hoots

VI, A. 50a-56a. Based on that evidence,

the court reaffirmed that "racially dis-

criminat[ory] acts of the state ha[d] been

18

a substantial cause of interdistrict

segregation," and concluded "that a multi

district remedy" involving some or all

of seven districts (including General

Braddock and the four petitioner districts)

was "appropriate" to cure the segregative

effects of the unconstitutional "redrawing

of [those] school district boundaries in

that [central eastern] part of Allegheny

13/County." Hoots VI, A. 50a-56a.~“

Turning to the question of remedy, the

district court rejected the plans submitted

by the state and the petitioner districts,

13/ Specifically, the court reaffirmed

that " [t]he State and County Boards

violated the Constitution in the manner

in which the [se] school district lines

were drawn." Hoots VI, A. 58a. The court

expressly implicated all of the former

districts in this conclusion. I_d. , A. 62a;

see Hoots VII, A. 79a; Hoots IX, A. 111a.

The court further found that public school

and municipal officials in what became the

petitioner districts were not "innocent" in

the decade-long reorganization process

19

finding all of them incapable of achieving

any effective desegregation. Based on all

"of the hearings held," the court concluded

that "only a single district formed from the

consolidation" of school districts whose

lines had been drawn as a part of the vio

lation would solve the "many difficulties"

identified in past hearings on prior plans.

Hoots VII, R. 65a-66a. See Hoots VIII, A.

71a-72.

Hearings were scheduled to determine

which districts were "to be consolidated

for the purpose of remedying the constitu

tional violations found." Hoots VII, A.

67a. See Hoots VIII, A. 72a-73a. Plain-

13/ continued

during which those districts' boundaries

were drawn or redrawn," but rather that

the desire of those officials to avoid

including their communities in a school

district with black students caused the

"elimination [of General Braddock] from

consideration for merger with those dis

tricts." Ijl. , A. 59a-60a.

20

tiffs presented expert testimony recommend

ing a consolidation of the Churchill,

Edgewood, General Braddock, Swissvale and

Turtle Creek districts. General Braddock

supported plaintiffs' position. Hoots

VIII, A. 73a. The other districts opposed

their inclusion in plaintiffs' plan, but

presented no evidence designed to establish

that they were not involved in, or affected

by, the underlying constitutional violation.

On April 28, 1981 -- nearly eight years

after the original finding of a constitu

tional violation — the district court for

the first time ordered that defendants take

specific, affirmative steps to remedy that

violation. Reaffirming once again its

finding that the "intentional creation fof

General Braddock] as a racially identifia

ble black district constituted the consti

tutional violation in this case," the court

ordered the consolidation of five of the

21

districts "involve [d] in the violations"

into a single district. The court found

"that a [n]ew [sjchool [djistrict composed

of the [former] school districts of Church

ill, Edgewood, Swissvale, General Braddock,

and Turtle Creek would achieve desegrega

tion ... and would achieve the highest

beneficial results over and above the

results of any other plan submitted to

this Court by any party during the whole

period of this litigation." Hoots VIII, A.

73a, 77a, 79a.

On February 1 , 1 982 , the court of

appeals unanimously concluded that the

district court's finding of intentional

discrimination was supported by substantial

evidence and was not clearly erroneous, and

that the consolidation remedy was well

within the court's equitable discretion.

Hoots IX, A. 86a.

22

The court determined that the finding

of a constitutional violation "was fully

supported by the record," which contained

"specific pieces of direct evidence of

segregative intent" as well as "circumstan

tial or 'objective' evidence." Hoots IX,

A. 108a-09a. Relying on contemporaneous

documents and testimony from both the

1 972 violation trial and from the many

subsequent proceedings, the court found a

substantial body of evidence demonstrating

that the state and county boards intention

ally segregated General Braddock and the

former white districts in order "to sat

isfy" public officials and residents of

neighboring white communities, who admitted

opposing inclusion in a district with

General Braddock expressly because of "the

black issue," "the non-white population ...

factor," the "black-white factor," and the

desire to shield white children from

23

"colored people [of] the kind that live in

North Braddock, Braddock and Rankin!"

Hoots IX, A. 105a-08a.

In addition, the court found that the

intentional-discrimination finding was un

dergirded by substantial objective evi

dence, including: the boards' violation

of almost all the applicable statutory and

administrative reorganization standards,

(such as the criteria requiring a 4000-per

son minimum student population in each dis

trict, the use of existing facilities, ra

cial and cultural diversity, and compre

hensive educational program); the severe

and maximally segregative impact of the

line drawing; the foreseeability — indeed,

the responsible officials' admitted aware

ness — ■ of that segregative result and of

the certain financial insolvency of the

one black district they created; and

the absence of any legitimate purpose or

- 24 -

valid state interest in the reorganization

plans adopted. Hoots IX, A« 108a.

Likewisef the court of appeals found

that "the district court did not abuse its

discretion" in ordering a multi-district

consolidation, since the line-drawing vio

lation was "itself ... interdistrict in

nature" and was properly "located and

defined" by the district court, and since

the remedy was "tailored ... to fit the

actual showing of de jure discrimination by

all of the districts involved" and was

"supported by more than enough evidence."

Hoots IX, A. 111a-13a, 121a-22a (emphasis

in original}.

As of July 1, 1981, the former dis

tricts ceased to exist as legal entities,

and the Woodland Hills School District

(hereinafter "Woodland Hills"), composed of

all the former districts, began to function

as a single desegregated school district.

25

Presently in its second year of operation

under a locally elected board of school

directors, Woodland Hills has a student

population of approximately 8,000, 81.3%

white and 18.7% black. It has graduated

students, adopted budgets, incurred debts

and obligations, levied and collected

taxes, and engaged in long range develop

ment and planning for further desegrega-

tion and other educational programs.

REASONS TO DENY THE WRIT

Respondents Dorothy Hoots, et al. ,

respectfully submit that the petitions for

certiorari should be denied for the reasons

that follow.

Initially, we note that none of the

six petitions asserts that the decision

below conflicts in any way with the deci

sion of any other court of appeals on any

of the numerous questions presented.

26

Nor is any substantial federal ques

tion presented. As we demonstrate below,

petitioners merely seek "certiorari to

review evidence and discuss specific

facts." United States v. Johnston, 268

U.S. 220 , 227 ( 1 925). Indeed, this is

the eighth time over the last nine years

that petitioners have asked a federal

appellate court "to review [the same]

evidence and dicusss [the same] specific

14/facts." Id.- *

1. Findings of Intentional Segrega

tion

Five of the six petitions argue that

14/ See Swissvale Area School District v.

Weber, No. 73-1849 (3d Cir. Oct. 12, 1973);

Hoots v ._Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

(Hoots III), 495 F.2d 1095 (3d Cir. 1974);

Churchill Area School District v. Hoots,

419 U.S. 884 (1974); Hoots v. Commonwealth

of Pennsylvania (Hoots IV), 587 F.2d 1340

(3d Cir. 1978); Hoots v. Commonwealth of

Pennsylvania (Hoots V ), 639 F.2d 972 (3d

Cir. 1981); Swissvale Area School District

v. Hoots, 101 S.Ct. 3113 (1981); Hoots v.

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (Hoots IX),

672 F.2d 1107 (3d Cir. 1982).

27

no findings of fact of purposeful segrega

tion were made and affirmed by the courts

below and, in the alternative, that the

findings of intentional segregation made

and affirmed below are supported by insuf

ficient evidence. E.g., Churchill Peti

tion, No. 81-2015, pp. 6, 11-13. The sixth

petition concedes and does not challenge

that: "The court of appeals, in affirming

the trial court's judgments, held that the

trial court had made the required findings

of segregative intent and that these

findings were not clearly erroneous."

Swissvale Petition, No. 81-2037, p. 11

(emphasis in emphasis).

In point of fact, precisely the same

arguments on sufficiency of the findings

and evidence have been considered and

rejected by both courts below. Hoots IX,

A. 96a-103a; 49a-63a. Indeed, this Court

28 -

itself has previously refused to review the

same claims. See Churchill Area School

D s t_ r _i c t__ v̂ _Hoots , No. 73-2039, cert .

denied, 419 U.S. 884 (1974), R. 2577a.

With respect to the absence of appro

priate findings, the court of appeals

reviewed the record and concluded that de

jure segregation was expressly alleged

by the plaintiffs and repeatedly found by

the district court. Thus, in denying the

motion to dismiss in 1971, the district

court held plaintiffs' complaint to

allege that "defendants intentionally and

knowingly created racially segregated

school districts." Hoots I, A. 1a. And,

in ruling favorably on that complaint in

1973, the district court found that state

officials made "educational policy deci

sions which were based wholly or in part

on considerations of the race of the

29

students." Hoots IX, A. 99a.

The court of appeals then analyzed the

preliminary factual determinations of the

district court that supported its final

intentional-discrimination determination in

1973 (as reiterated and reaffirmed on

1 5(several occasions between 1975 and 1981). '

The court of appeals concluded that appro

priate findings had been made concerning

15/ In March 1981, the district court

undertook a careful and extensive "review

[of] the facts of this case to determine

whether an interdistrict remedy is appro

priate. " Hoots_VI, A. 49a. The court

reviewed both the original 1973 liability

record and subsequent evidence on viola

tion, much of it presented by the petitioner former districts, jLd_. A. 56a, and

concluded that: the reorganization plan was

devised by state officials to satisfy the

wishes of surrounding municipalities not to

be placed in a district with black stu

dents; the districting was not ration

ally related to any legitimate purpose;

the boundaries promote no valid state

interest; and public officials in the

districts created by the reorganization

plan were not "innocent," but rather were

themselves guilty of injecting racial

animus into the reorganization process.

Id. A. 54a-55a, 59a.

30

the racial motives of the state and county

officials who created the five former

districts, as well as the foreseeably and

advertently segregative consequences of

those line-drawing decisions, and the

absence of any valid state interest served

by those lines. Hoots 1_X , 1 0 0 a - 0 2 a .

Similarly, the claim that there was

insufficient evidence to support the

intentional-segregation findings of the two

courts below is without foundation. As the

court of appeals concluded, "the district

court's constitutional violation finding

was not clearly erroneous and, indeed, was

fully supported by the record." Hoots IX,

A. 109a; see id. ; A. 103a-09a; Hoots VI,

50a-62a.

Moreover, the categories of proof

relied upon by the courts below comport

fully with the evidentiary standards

established by this Court for determining

31

the existence of intentional segregation in

school desegregation cases. First/ as

directed by this Court's prior decisions,

the courts below relied on various "spe

cific pieces of direct evidence of segrega

tive intent or purpose" (see pp. 21-22,

16/supra). Hoots IX, A. 108a. That evi

dence convincingly established that state

and county officials intentionally created

General Braddock as a predominantly black

school district in order to accommodate the

racial antagonism of officials and parents

in the surrounding white districts and

16/ See Village of Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 429

U.S. 252, 260, 267 (1977), citing with ap

proval Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369,

373-76 (1967) and Davis v. Schnell, 81 F.

Supp. 872, 875, 880-81 (S.D. Ala.), aff'd,

336 U.S. 933 (1949). See_also United

States v. School Commissioners, 573 F.2d

400, 405-08 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 439

U.S. 824, on remand, 456 F. Supp. 183,

187-89 (1978); United States v. Missouri,

363 F. Supp. 739, 745-46 (E.D. Mo. 1973),af f 'd, 515 F . 2d 1 365, 1367 (8th Cir.)

cert, denied, 423 U.S. 951 (1975). r

32 -

communities, who did not want their child

ren to attend school with blacks. Thus,

unlike this Court's recent decision in

Rogers v. Lodge, ___ U.S. __No. 80-2100

(July 1, 1982), in which the Court held that

"discriminatory intent need not be proved

by direct evidence," slip op. at 5 (major

ity opinion), both courts here relied

primarily on "direct, reliable, and un

ambiguous indices of discriminatory

intent," slip op. at 4 (Powell, J., dis

senting) (emphasis in original).

Second, the courts also "relied

on circumstantial or 'objective' evidence."

Hoots IX, A. 108a. Such evidence included

(i) the repeated rejection by state and

county officials, over a period of several

years, of desegregative reorganization

proposals and the substitution of boundary

lines that conformed to "the desires of as

33

many of the surrounding municipalities as

possible to be placed in a school district

which did not include" blacks, Hoots II, A.

17/32a; Hoots VI, A. 55a; Hoots IX, A. 108a;—

(ii) those officials' thoroughgoing "dis

regard [for] statutory and administrative

reorganization standards, e.g., the statu

tory 4,000 pupil minimum guideline, the

requirement that existing facilities be

used where possible, ... and the require

ment that each district be capable of

providing a comprehensive educational

program," Hoots IX, A. 108a; Hoots VI, A.

54a; Hoots II, A. 28a-30a; 1 8/ ( iii )

17/ See Village of Arlington Heights,

supra, 429 U.S. at 264-65 ("historical

background of the decision is one eviden

tiary source" of intentional segregation

and the "specific sequence of events leading up to the challenged decision also

may shed some light on the decisionmaker's

purposes").

18/ See Village of Arlington Heights,

supra, 429 U.S. at 267 ("substantive de-

34

those officials' consistent rejection

of desegregative redistricting plans (which

would have complied with the reorganization

standards) in favor of alternatives that

maximized racial segregation, Hoots IX,

A. 108a; Hoots VI, A. 54a-55a; Hoots II, A.

1 9/21a-22a, 27a-28a, 31a-32a;~~ (iv) the

knowing, indeed admittedly advertent, crea

tion by state and county officials of ra

cially segregated school districts, Hoots

IX, A. 106a, 108a; Hoots VI, A. 54a; Hoots

18/ continued

partures [from applicable standards] may be

relevant, particularly if the factors

usually considered important by the desi-

cionmaker strongly favor a decision con

trary to the one reached").

19/ See Village of Arlington Heights,

supra , 429 U . S . at 264; G o m 1̂ _1 _i C3 ri_ v .

L ightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 ( 1 960 ); United

States v. Board of School Commissioners,

supra, 573 F.2d at 413.

35

11, A . 2 6a-2 7a; (v) the foreseeability

of the reorganization plan's harmfully seg

regative consequences, Hoots IX, A. 108a;

Hoots VI, A. 53a; Hoots II, A. 26a-28a,

2 1 /31a; and (vi) the fact that no other

comb ination of school districts in the

central eastern area would have as success

fully isolated black students in one

district (General Braddock) and white

students in the surrounding districts.

20/ See Columbus Board of Education v.

Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 465 (1979) ("Adher

ence to a particular policy or practice

with full knowledge of the predictable

effects of such adherence upon racial

imbalance in a school system is one factor

among many others which may be considered

by a court in determining whether an

inference of segregative intent should be

drawn").

2 1 / See Dayton Board of Education v.

Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526, 536 n. 9 ( 1 979)

("proof of foreseeable consequences is one

type of quite relevant evidence of racially

discriminatory purpose"); Personnel Adminis

trator v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256, 279 n.25(1979); United States v. Board of School

Commissioners, supra, 573 F.2d at 413.

36

Hoots III, A. 22a-25a; Hoots IX, 108a.'—

Petitioners, therefore, are plainly

wrong that evidence of purposeful segrega-

, ' . 23/tion was lacking. As the court of ap

peals concluded, the findings of fact that

the district court originally made in 1973

and that it supplemented in March 1981 are

not "clearly erroneous." Rule 52(a), Fed.

R. Civ. Pro.; see United States v. United

States Gypsum C o 333 U .S . 364, 395

(1948). The findings of a trial judge who

22/ See Rogers v. Lodge, supra, slip. op.

at 5 (majority opinion); Washington v.

Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 242 (1976) ("it is ...

not infrequently true that the discrimina

tory impact ... may for all practical

purposes demonstrate unconstitutionality").

23/ Their claim, in any event, rests

on no more than inaccurately selective

references to individual aspects of

the comprehensive findings and evidence

below. E .g ., Churchill Petition, No.

81-2015, p. 11 (only finding or evidence

discussed concerns racial disparity);

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Petition, No. 81-2038, pp. 11-12 (only findings or

evidence discussed concerns racial dispar

ity and foreseeability).

37

had a full opportunity to examine the credi

bility of the witnesses over the course of

eleven years are entitled to substantial

deference, as, indeed, are the conclusions

of a court of appeals that has gained

familiarity with the litigation in the

course of reviewing various matters on

six occasions over the last nine years.

See notes 2, 14, supra.

Such "deference" is especially appro

priate because of the trial court's "proxi

mity to local [school] conditions," Brown

v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 299

(1955), and because the issue of "whether

... differential impact of [a practice]

resulted from an intent to discriminate on

racial grounds 'is a pure question of fact,

subject to Rule 52's clearly erroneous

standard.'" Rogers v. Lodge, supra, ___

U . S . ___, slip. op. at 9-10 (majority

opinion) , quoting P^l^maan- S^ajidard_v .

38

Swint, ___ U.S. y 50 U.S.L.W. 4425r 4429

(April 27, 1982); Dayton Board of Education

v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526 , 534 ( 1 979);

Commissioner v. Duberstein, 363 U.S. 278,

286 (1960); United States v. Yellow Cab

Co.f 338 U.S. 338, 341 (1949).

Moreover, " [tjhe Court of Appeals

did not hold any of the District Court's

findings of fact to be clearly erroneous,

and this Court has frequently noted its

reluctance to disturb findings of fact

concurred in by two lower courts. See,

e.g. , Berenyi v. Information Director, 385

U.S. 630, 635 (1967); Blau v. Lehman, 368

U.S. 403 (1962); Graver Mfg. Co. v. Linde

Co., 336 U.S. 271, 275 (1979)," Rodgers v.

Lodge, supra, __ U.S. , slip, op. at 10

(majority opinion); cjE. Columbus Board of

Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 468

(Burger, C.J., concurring); _id. at 470-79

(1979) (Stewart, J., concurring).

39

Nor are novel or significant legal

issues presented. As indicated above,

the evidentiary sources utilized by the

lower courts conform perfectly to the

Court's directives on the proper method of

proving intentional segregation. See nn.

16-22, supra, and accompanying text. The

courts below did no more than conscien

tiously apply the well-established and

noncontroversial requirements of Milliken

v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 617 (1974), to the

24/facts at hand. This, accordingly, is

not a case in which the finding of a

24/ Accord, Evans v. Buchanan, 582 F. 2d

750 (3d Cir. 1978)(en banc), cert, denied,

446 U.S. 923 (1980); 555 F.2d 373 (3d Cir.

1977)(en banc), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 934

(1978); 393 F. Supp. 428 (D. Del.), (3-

judge court), af f'd, 423 U.S. 963 ( 1975);

Morrilton School District v. United States,

606 F.2d 222 (8th Cir. 1979), cert, denied,

444 U.S. 1071 (1980). United States v.

Board of Commissioners, su£ra; United

States v. Missouri, 515 F.2d 1365 (8th

Cir.), cert, denied, 423 U.S. 951 (1975).

40

constitutional violation presses the

limits of any doctrine of liability.

Rather, the key violation found, the

"[gerrymandering of boundary lines,"

Columbus Board of Educat ion v. Penick,

supra, 443 U.S. at 462 n„10, is a classic

example in the school context of intention-

ally segregative state action.

Moreover, the record on violation is

unequivocal. For example, the chairman of

the state board of education admitted under

oath that, had reorganization criteria been

properly applied and had racial factors not

been improperly considered, the board

"wouldn't have done it" — e.g. , would not

have created General Braddock and insulated

its predominantly white neighbors. R .

2 702a-*03a (T. Christman). Moreover,

another state official testified that, had

reorganization criteria, rather than racial

biases, been followed in the reorganization

41

process, none of the districts in central

eastern Allegheny County would have been

created as racially segregated units. R.

254a, 260a (T. Anliot).—

2 5/ While conceding that the district

court applied proper standards and relied

on sufficient evidence in finding a consti

tutional violation and that the two courts

below found that all of the petitioner

districts' boundaries were drawn as a

result of their racially motivated efforts

to avoid a merger with any black districts,

Swissvale nevertheless argues that the

matter should be remanded to provide

yet another opportunity for the districts

to present evidence that they would have

been created as they were regardless of the

constitutional violation. Swissvale

Petition No. 81-2037, at pp. 11, 18-19.

This argument simply ignores substantial

record evidence (including the Christman

and Anliot testimony noted in text) and

repeated findings establishing that: none

of the petitioner districts would

been created as they were

constitutional violation;

districts' boundary lines were ally related to any legitimate

"did not promote any valid state interest;"

and that there was no explanation apart

from race that could possibly account for

the configuration of districts actually

created by state and county officials.

Hoots IX, A. 100a; Hoots VI, A. 55a, Hoots

II, A. 32a-33a.

have

absent the

that those

not "ration-

purpose" and

42

2. The Remedy

Five of the six petitions seek certi

orari to review the exercise of discretion

by the courts below in ordering consolida

tion of General Braddock and the four

surrounding white districts into one de

segregated district. The Commonwealth does

26/not oppose the remedy.— Commonwealth

of Pennslyvania Petition, No. 81-2038,

p. 16 n. 9. These identical arguments have

been fully considered and rejected by both

courts below, Hoots VI, A. 56a-62a; Hoots

VIII, A. 79a; Hoots IX, A. 115a-16a, and

this Court has previously declined to

review these claims. Churchill Area School

26/ Indeed, in September 1980, the Common

wealth informed the district court that the

consolidation of these five districts

was a feasible and efficacious remedy

considering educational, administrative and

desegregation criteria. Relying on the

same criteria, the Commonwealth warned the

court against a consolidation of fewer than

these five districts. R. 2644a-45a.

43

District v._Hoots, No. 73-2038, cert.

denied, 419 U.S. 889 (1974), R. 2577a.

In order to assess the district

court's exercise of discretion on remedy,

it is first necessary to note that fully

eight years passed between the time the

district court first found that state,

county and local officials had committed

a constitutional violation and the imposi

tion of any remedy. Notwithstanding the

patient efforts of the district court

during those years, petitioners defaulted

completely on their affirmative duty to

provide an expeditious and adequate remedy

, ,,2 7/to eliminate "root and branch"— the

effects of the violation found, i.e., the

racially motivated drawing of segregative

district boundary lines. Accordingly, it

was only because of petitioners' default

27/ Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S.

430, 439 (1968).

44

that the district court was forced to frame

2 8/a remedy itself.—

The court devised the remedy, however,

only after holding numerous hearings at

which expert and lay testimony and docu

ments were received. The district court,

as discussed above, reviewed the entire

record on violation before considering any

remedy and gave each surrounding district a

full opportunity to prove that it was not

affected by or guilty of any specific vio-

lational act and that it could not be in

volved in any remedy. See Hoots VI, A. 56a.

The district court concluded that Gen

eral Braddock and each of the four peti

tioner districts could properly be included

in an interdistrict remedy for two indi

vidually sufficient reasons. First, the

district court concluded that, since "[t]he

28/ See Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 15 (1971).

45

State and County Boards violated the con

stitution in the manner in which the school

district lines were drawn ... [in] all [of

the] surrounding districts," Hoots VI, A.

58a (emphasis added), "racially discrimi-

nat[ory] acts of the state have been a sub

stantial cause of interdistrict segrega

tion," id. , A. 56a, and "the effects of

[that] unconstitutional state action are

felt in [ a_l _1 of the surrounding] dis

tricts," id., A. 57a. Accordingly, follow

ing the unanimous rule of this Court and

the courts of appeals, the district court

held that "[a] multidistrict remedy can be

applied to surrounding districts that have

not been found to have committed a consti

tutional violation themselves [because]

their boundaries were drawn or redrawn

during the course of the ... violat ion

46

committed by other state actors. Id. ,

A 29/A. 56a.

Second, the court reiterated that, in

any event, public officials in each of

the petitioner districts (or their prede

cessor districts) were actually at fault,

because they "continually sought to avoid

being included in a school district with

[General Braddock] due to the high con-

29/ Accord, Milliken v. Bradley, supra,

418 U.S. 746 (interdistrict remedy appro

priate where "racially discriminatory

acts of state ... officials have been a

substantial cause of interdistrict segrega

tion," particularly "where district lines

have been deliberately drawn on the basis

of race" by those officials; _i d . a t 755 (Stewart, J., concurring) ( interdis

trict "restructuring of district lines"

appropriate where "state officials had

contributed to the separation of the races

by drawing or redrawing school district

lines" ); Morrilton School District No. 32

v. United States, supra; United States v.

Board of School Commissioners, supra, 573

F .2 d at 4 10; Evans v. Buchanan, 416 F.

Supp. 328 (D. Del. 1976), aff1 d, 555 F.2d

373 (3d Cir. 1977)(en banc), cert, denied,

434 U.S. 934 ( 1978).

47

centration of blacks." Hoots VI, A. 59a.

30/See also Hoots IX, A. 114a.—

On appeal, the petitioner districts'

claims of insufficient factfinding and

evidence on their involvement in, and

responsibility for, the unconstitutional

reorganizations were fully briefed and

again rejected. Hoots IX, A. 109a-22a.

The court of appeals concluded that

the evidence relied on by the district

30/ Accord, Milliken v. Bradley, supra,

418 U.S. at 744-45 (interdistrict remedy

appropriate where "racially discriminatory

acts of ... local school officials have

been a substantial cause of interdistrict

segregation," particularly where, as a

result of those acts, "district lines have

been deliberately drawn on the basis of

race"); Morrilton School Dist. No. 32 v.

United States, supra, 606 F.2d at 226-29;

Evans v. Buchanan, 582 F.2d 750, 762-67 (3d

C i r . 1 9 7 8); Dn_ited_States_v_._Board of

School Commissioners, supra, 573 F. 2d at

407-08, 410; United States v. Missouri,

supra, 515 F.2d at 1369-71 , af f1 g 388 F.

Supp. 1058, 1059-60 (E.D. Mo. 1978), and

363 F. Supp. 739, 745-46, 747-50 (E.D. Mo.

1973).

48

court made out an "actual showing of de

jure discrimination by [and affecting] all

of the districts involved" in the remedy.

Hoots IX, A. 111a (emphasis in the origi-

31/ In view of the two-court conclusion

that respondents made out an "actual

showing ... [that] all of the [petitioner]

districts" were (i) affected (indeed

created) by the state and county boards’

invidious actions, and (ii) were themselves

guilty of racially motivated segregative

acts, Hoots IX, A. 111a (emphasis in

original), Swissvale's argument, joined by no

other petitioner, that its inclusion in the

remedy was solely the function of having

some burden of proof allocated to i_t is

completely misdirected. See Swissvale

Petition, No. 81-2037, p. 18. The only

"burden" allocated to Swissvale and the

other districts was the traditional defen

dant’s burden (more accurately, oppor

tunity) to rebut the otherwise legally

sufficient proof of intentional discrimina

tion by and affecting each district that

was introduced by plaintiffs. Like the

other petitioner districts, Swissvale

failed to meet that "burden" because it

failed, despite numerous opportunities, to

adduce any evidence tending to rebut plain

tiffs' showing that Swissvale's boundaries

were the product of the state's, county's

and its own officials' intentionally

segregative acts and decisions.

49

Indeed, even the court of appeals'

summary review of "some of [the] evidence"

relied upon by the district court squarely

implicates each of the four petitioner

districts in the violation — for example,

through (i) the admissions under oath of an

area municipal official that he and his

counterparts in the predecessor districts

of Swissvale and Turtle Crrek "pressured

State and County Board members in the

1960's to insulate their municipalities ...

from merger with [General Braddock] because

of ... the bitterness felt by 'whites'

towards 'blacks' in the area;" (ii) the

contemporary statements of other area

officials involved in the reorganization

process charging Churchill with refusing to

merge with neighboring districts in 1964

for reasons of "'race'" and "'color,'" and

(iii) the state and county boards' creation

of the sub-1000-pupil Edgewood district in

50 -

1969, in stark contravention of the applic

able guidelines' 4000-pupil minimum. Hoots

IX, A. 105a, 106a-07a, 108a, quoting R.

118a-126a, 588a.

The rejection — by both courts below,

after plenary consideration -- of the

claim of each of the petitioner districts

that it should not be included in any

remedy is entitled to substantial defer

ence. For factual and evidentiary claims

on remedy that have been rejected by two

courts below are no more appropriate for

further review than similar issues going to

violation. See pp. 36-38, supra. Indeed,

a "district court's equitable power to

remedy past wrongs is broad, for breadth and

flexibility are inherent in equitable

remedies," Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 15 (1971),

and because breadth is necessary "to allow

the most complete achievement of the

51

[remedial] objectives ... attainable under

the facts and circumstances of the specific

case." Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

424 U.S. 747, 770-71 (1976).

The intimate knowledge and experience

of the trier of fact — and of the court of

appeals — with the circumstances of the

case, as well as the long course of pro

ceedings and the careful and deliberate

framing of relief below even more tho

roughly undermine petitioners' claim of

abuse of discretion. This, after all, is a

case in which the Commonwealth and peti

tioner districts themselves proposed

various interdistrict consolidation

remedies. See n.12, supra. It is hardly

an abuse of discretion for the trial judge

to select from among the available remedial

52

alternatives the remedy that long expe

rience dictated would most effectively cure

the underlying violation and provide

equitable relief.

Furthermore, no petitioner disputes

the express findings of the district court,

Hoots VIII, A. 73a, concurred in by the

court of appeals, Hoots IX, A. 116a-19a,

that the consolidation of the former

districts into the Woodland Hills School

District is the bejs;t remedy in terms

of desegregation, enhanced educational

32/program and administrative efficiency:-—

The consolidation results in an economically

and demographically stable district, with a

32/ In reaching this conclusion, the

courts below relied on the same reorganiza

tion guidelines and criteria that should

have been, but were not, followed by the

state and county boards in the 1 960's,

including racial and cultural diversity,

geographic size, contiguity, transporta

tion, pupil population, economic efficiency

and financial stability. See pp. 23, 33,

supra.

53

racial distribution comparable to that in

the neighboring areas of Allegheny County.

Notwithstanding the consolidation, Woodland

Hills is smaller in size than the average

school district in Allegheny County.

Moreover, the new district's roughly

circular shape lends itself to increased

administrative and transportation efficien

cies — since no point in the district lies

more than 2.5 miles from the center. As a

result, the preexisting transportation

facilities of the merged districts are

adequate to serve the transportation

needs of the new district, and the merger

has accordingly resulted in no increase in

the number of students bused to school.

Hoots v. Commonwealth, No. 71-538 (W.D. Pa.

May 12, 1982).

54

Because of declining enrollment in

all the former districts, consolidation and

desegregation also promotes educational

efficiency and economy. Thus, not only

does the merger place the new district's

student population above the 4000-person

statutory minimum in Pennsylvania (previ

ously, all five former district were below

that minimum), but it also allows for the

closing of old and underutilized facilities

and for a better organized comprehensive

educational program without additional

costs. Indeed, as the courts below found,

e _j_c[. , Hoots IX, A . 118a, there is the

possibility of very substantial monetary

savings as a result of the merger. In any

event, Woodland Hills is financially

viable, having a higher tax base per

student than the state average. Hoots IX,

A. 116a-119a, 73a-75a.

55

In sum, there is no reason to unravel

a constitutionally mandated and effective

remedy that has provided the central

eastern portion of Allegheny County with

equal educational opportunity for the first

time since the 1960's.

3. Meaningful Opportunity to Par

ticipate

Petitioner districts also seek review

of the district court's decision not to

join them as defendants, against their

express wishes, prior to the initial

violation trial in 1973. The Commonwealth

— which failed to appeal the nonjoinder

issue in 1 972 or thereafter, and which

itself submitted proposals for interdis

trict relief that included all four peti

tioner districts, see n.12, supra -- now

also seeks review of the nonjoinder

question. Both the district court and

court of appeals have rejected petitioners'

56

contention on numerous occasions, Hoots I,

A. 4a-5a; Hoots II, A. 33a-~35a? Hoots III,

A. 42a; Hoots IX, A. 111a, and this Court

itself has previously declined to review

the matter. See Church ill Area School

D _i ssJL£jL£ Hoot_s r n o . 73-2038, cert .

denied, 419 U.S. 884 (1974), R. 2578a-79.

In any event, it is clear that petitioner

districts were not in fact denied a mean

ingful opportunity to participate in any

stage or aspect of this litigation.

The original motions to dismiss for

failure to join mandatory parties were

correctly denied in 1972, under Rule 19,

Fed. R. Civ. P., because Pennsylvania law

does not afford local school districts any

legally cognizable interest in their

33/boundaries sufficient to make them man-

33/ See Chartiers Valley Joint Schools v. County Board, 418 Pa. 250, 21 1 A.2d 487,

501 (1965).

57

datory parties in a suit against the state

regarding those boundaries. Hoots I, A.

„ . 34/4a-5a; Hoots II, A. 33a-35a: >phe dis

trict court nevertheless went beyond the

dictates of Rule 19, and directed the par

ties to notify the surrounding districts

that their boundaries might be changed and

to invite them to intervene. See Hoots II,

A. 33a-35a. Indeed, the court stated in a

published order that it would look favor

ably on intervention motions from the

34/ Accord, Husbands v. Commonwealth of

Pennsylvania, 359 F. Supp. 925, 937

(E.D. Pa. 1973)(Pennsylvania reorganization

statutes deprive school districts of

an interest in their boundaries sufficient

to make those districts mandatory parties

in a suit similar to the present one); 3A

MOORE'S FEDERAL PRACTICE M 19.07-1[2] &

n.4, at 129-30 (citing with approval the

district court's joinder ruling in Hoots

II). See also Lee v. Macon County, 268

F.2d 458, 479 (M.D. Ala.)(3-judge court),

aff'd, 389 U.S. 215 (1967); Griffin v.

Board of Education, 23 9 F. Supp. 560, 566(E.D. Va. 1965).

- 58 -

neighboring districts. Hoots X, A. 5a.

See pp. 10-11, supra.

In short, from the very beginning, the

petitioner districts had full notice of,

and a meaningful opportunity to participate

in, the proceedings in this case. Indeed,

it is conceded by the petitioner districts

that their failure to participate in the

original trial was not the result of some

action or inaction on respondents' or the

district court's part, but instead was the

result of a studied decision on their

parts, dictated by considerations of

so-called "prudent lawyering," to "'sand

bag' -- to gamble on [a favorable ruling]

while saving [another] claim in case the

gamble doesn't pay off." Engle v. Isaac,

U.S. 71 L . Ed „ 2d 783, 80 1 n.34

(1982). See n.8, supra, and accompanying

text. If the districts' interests were in

59

any way prejudiced, therefore, it was no

one's fault but their own.

In any event, petitioner district's

interest were not adversely affected

by their deliberate nonparticipation at the

1 972 trial, for, as the court of appeals

found in its most recent discussion of this

issue, Hoots IX, A. 102a, the district

court actually permitted those districts,

following their post-1973 intervention and

joinder, to reopen the violation finding and

to adduce whatever evidence they chose on

the matter — which they did. For in

stance, the chairman of the State Board of

Education, who testified about the reorgan

ization process in central eastern Alle

gheny County and admitted that his agency

knowingly segregated the school districts

there, see p. 40, supra, R. 2702a-03a, was

expressly called in 1 975 by the former

districts to testify as .t h e_ i_ .r witness

60 -

on the issue of the existence and scope of

the violation. R. 2673a, 2799a. At no

time, in fact, have any of the petitioner

districts identified or proffered any

evidence that they were prevented from

presenting on any issue relevant to this

litigation.

Having had formal notice from the

outset about the pendency, substance, and

implications of this litigation, having

been expressly invited by the district

court to participate in it if they so

chose, and having in fact participated

fully on all issues over the course of the

last nine years, see pp. 14-15 & n.11,

supra, the petitioner districts have no

basis in fact or law for asking this Court

to review the district court's exercise of

its discretion not to force them, against

their wills, to participate in a single

61

hearing held more than nine years 35/ago.—

CONCLUSION

The petitions for writs of certiorari

should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

THOMAS J. HENDERSON*

1312 E. Carson St.

Pittsburgh, Pa. 15203

(412) 431-7255

*Counsel of Record

35/ The claim that the surrounding dis

tricts were denied a meaningful opportunity

to participate can only be made by ignoring

that this case is completely unlike Milliken

v. Bradley, supra, 418 U.S. at 730-3 1 ,

752, where the surrounding districts

did not have formal notice of, were not

invited to participate in, and in fact did

not participate in, any; proceedings.

Milliken, moreover, did not involve either

segregative redistricting by state offi

cials, or state school-district-reorganization statutes under which local districts

were expressly divested by the state

legislature of any legal interest in their

boundaries.

- 62 -

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

BILL LANN LEE

JAMES S. LIEBMAN

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys for Respondents Dorothy Hoots, et al.

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C 219