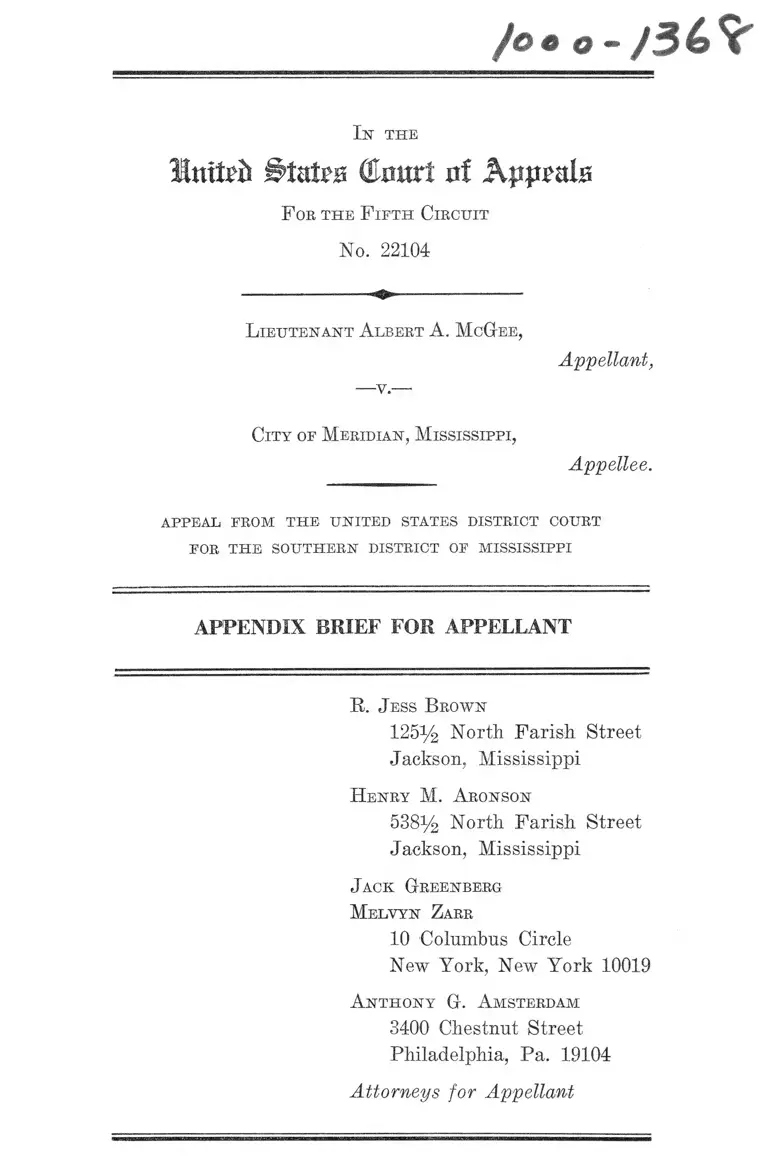

McGee v. City of Meridian, Mississippi Appendix Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McGee v. City of Meridian, Mississippi Appendix Brief for Appellant, 1965. c42d9590-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f743d1fb-240f-4144-a235-58f855e7fd62/mcgee-v-city-of-meridian-mississippi-appendix-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

/ o * o - /3 6 %

I n th e

Initio lytatrs Court of Appals

F oe t h e F if t h Circu it

No. 22104

L ie u ten an t A lbert A . M cG ee ,

C it y of M eridian , M ississippi,

Appellant,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

APPENDIX BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

R. J ess B row n

125% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

H en ry M. A ronson

538% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

J ack G reenberg

M elvyn Z arr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A n t h o n y G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

Attorneys for Appellant

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

I. T he B ackground op 28 U. S. C. §1443 .... ........... . 1

A. Legislative Background .............. ..... .............. - 1

B. Judicial Background ........ 39

II. T he Construction op 28 U. S. C. §1443 ............... 52

A. “ Law Providing for Equal Bights” ................. 53

B. Subsection 1443(1): A “ Bight” Which a Per

son Is “Denied or Cannot Enforce” ............... 68

C. Subsection 1443(2): An Act “ Under Color of

Authority Derived From” a “ Law Providing

for Equal Bights” ................................................. 83

D. The Bationale of Federal Civil Bights Be-

moval Jurisdiction ............................................. 91

T able of Cases

Alabama v. Allen, S. D. Ala., C. A. No. 3385-64, April

16, 1965 .............................................................................. 79

Alabama v. Boynton, S. D. Ala., C. A. No. 3560-65, April

16, 1965 .............................................................................. 79

Anderson v. Elliott, 101 Fed. 609 (4th Cir. 1900), dism’d

22 S. Ct, 930 (1902)......................................................... 6

Arceneaux v. Louisiana, 376 U. S. 336 (1964) ............... 93

Arkansas v. Howard, 218 F. Supp. 626 (E. D. Ark.

1963)......................................... 58,83

Arnold v. North Carolina, 376 U. S. 773 (1964) .... ....... — 41

11

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 IT. S. 360 (1964)...........................81, 92

Barr v. City of Columbia, 378 U. S. 146 (1964) ............... 93

Bigelow v. Forrest, 76 U. S. (9 Wall.) 339 (1869) ....... 64

Birsch v. Tumbleson, 31 F. 2d 811 (4th Cir. 1929) ....... 7

Blyew v. United States, 80 U. S. (13 Wall.) 581 (1871) 30

Board of Educ. v. City-Wide Comm, for the Integration

of Schools, 2d Cir., No. 29501, Feb. 18, 1965 ............... 83

Boynton v. Clark, U. S. D. C. (S. D. Ala.), No. 3559-65,

Jan. 23, 1965 ............................................................... 71

Brazier v. Cherry, 293 F. 2d 401 (5th Cir.), cert, denied,

368 U. S. 921 (1961) ....................................................... 36

Brown v. Cain, 56 F. Supp. 56 (E. D. Pa. 1944) ............. 6, 7

Brown v. City of Meridian, No. 21730 (5th Cir.) ........... 74

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U. S. 110 (1883) .........................45, 47

California v. Lamson, 12 F. Supp. 813 (N. D. Cal. 1935),

petition for leave to appeal denied, 80 F. 2d 388 (W il

bur, Circuit Judge, 1935) ................................................ 51

Castle v. Lewis, 254 Fed. 917 (8th Cir. 1918).................... 7

City of Birmingham v. Croskey, 217 F. Supp. 947 (N. D.

Ala. 1963) .......................................................................... 51

City of Clarksdale v. Gfertge, 237 F. Supp. 213 (N. D.

Ala. 1964) ........................................................................ 51, 83

Cohens v. Virginia, 19 U. S. (6 Wheat.) 264 (1821) ....... 4

Dilworth v. Riner, 5th Cir., No. 22008, March 18, 1965

68, 69, 78

Dombrowski v. Pfister, ------ - U. S .------ , 33 U. S. L. Wk.

4321, April 26,1965 .............................................74, 80, 81, 94

Douglas v. City of Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157 (1943) ....55, 63

Dresner v. City of Tallahassee, 375 U. S. 136 (1963) .... 93

PAGE

I l l

PAGE

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 (1963) ........... 92

Egan y . City of Aurora, 365 U. S. 514 (1961) ............... 55

England v. Louisiana State Board of Medical Examin

ers, 375 U. S. 411 (1964)................................................... 91

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584 (1958) ................... 41

Ex parte Bridges, 4 Fed. Cas. 98 (No. 1862) (C. C. N. D.

Ga. 1875) ..................... ..................................................... 61

Ex parte McCardle, 73 U. S. (6 Wall.) 318 (1868) .......6,19

Ex parte McCready, 15 Fed. Cas. 1345 (No. 8732) (C. C.

E. D. Va. 1874).................................................................. 61

Ex parte Royall, 117 U. S. 241 (1886) ............................... 61

Ex parte Tilden, 218 Fed. 920 (H. Ida. 1914) ............. ..... 7

Ex parte United States ex rel. Anderson, 67 F. Supp.

374 (S. D. Fla. 1946) ...................................................... 7

Ex parte Warner, 21 F. 2d 542 (N. D. Okla. 1927) ....... 6

Farmer v. State,------ Miss. -------, 161 So. 2d 159 (1964),

rev’d , ------ IT. S .------- , April 26, 1965 ........................... 92

Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391 (1963)....................................... 20

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315 (1951) ....................... 92

Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S. 44 (1963) ............... 92

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U. S. 51 (1965) ................... 92

Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565 (1896) .......45, 47, 63, 75

Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496 (1939)...........................55, 67

Henry v. Mississippi, 379 U. S. 443 (1965) ................... 93

Henry v. Rock Hill, 376 U. S. 776 (1964) ....................... 92

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U. S. 475 (1954) ....................... 41

Hill v. Pennsylvania, 183 F. Supp. 126 (W. D. Pa.

1960) ................................................................................51,55

IV

Hornsby v. Allen, 326 F. 2d 605 (5th Cir. 1964), rehear

ing denied, 330 F. 2d 55 (5th Cir. 1964) .............. ......... 66

Hull v. Jackson County Circuit Court, 138 F. 2d 820

(6th Cir. 1943) ................................................................... 51

In re Fair, 100 Fed. 149 (C. C. D. Neb. 1900)................... 6

In re Kaminetsky, 234 F. Supp. 991 (E. D. N. Y. 1964) 51

In re Matthews, 122 Fed. 248 (E. D. Ky. 1902) ............... 7

In re Miller, 42 Fed. 307 (E. D. S. C. 1890) ................... 7

In re Neagle, 135 U. S. 1 (1890) ...................................6, 8, 20

Kelley v. Page, 335 F. 2d 114 (5th Cir. 1964)................... 69

Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1 (1906) ...................26, 48, 49

Knight v. State, —■— M iss.------ , 161 So. 2d 521 (1964) 92

Lefton v. Hattiesburg, 333 F. 2d 280 (5th Cir. 1964) ....36, 92

Lewis v. Bennett, 337 F. 2d 579 (4th Cir. 1964) ............... 93

Lima v. Lawler, 63 F. Supp. 446 (E. D. Ya. 1945)........... 6, 7

Louisiana v. Murphy, 173 F. Supp. 782 (W. D. La. 1959) 51

McCoy v. Louisiana State Bd. of Educ., 332 F. 2d 915

(5th Cir. 1964) ................................................................... 93

McFarland v. American Sugar Ref. Co., 241 U. S. 79

(1916) .................................................................................. 66

McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U. S. 420 (1961)................... 66

McNeese v. Board of Educ., 373 U. S. 668 (1963).........33, 92

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 (1946) ........................... 79

Maryland v. Kurek, 233 F. Supp. 431 (D. Md. 1964) ....51, 55

Metropolitan Cas. Ins. Co. v. Stevens, 312 U. S. 563

(1941) .................................................................. 43

Monroe v. Pape, 365 H. S. 167 (1961) ...............33, 55, 64, 92

Murray v. Louisiana, 163 U. S. 101 (1896)....................... 45

PAGE

V

Neal y . Delaware, 103 U. S. 370 (1881) ....... 42, 43, 46, 47, 75

New Jersey v. Weinberger, 38 F. 2d 298 (D. N. J. 1930) 51

New York v. Galamison, ------F. 2 d --------, 2d Cir., Nos.

29166-75, Jan. 26, 1965, cert. den. ------ U. S. ------ ,

April 26, 1965 ...................................53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 60,

61, 62, 63, 66, 83, 87

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254 (1964) .... 79

Norris v. Alabama, 294 IT. S. 587 (1935)........................... 41

North Carolina v. Alston, 227 F. Supp. 887 (M. D. N. C.

1964).................................................................................... 51

North Carolina v. Jackson, 135 F. Supp. 682 (M. D.

N. C. 1955) ...................................................................... 52, 73

People v. McLeod, 25 Wend. 482 (Sup. Ct. N. Y. 1841) 7

Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U. S. 158 (1944) ............... 79

Pritchard v. Smith, 289 F. 2d 153 (8th Cir. 1961)........... 36

Rachel v. Georgia, —— F. 2 d ------ , 5th Cir., No. 21354,

March 5,1965 .......................................... 54, 55, 58, 68, 74, 81

Rand v. Arkansas, 191 F. Supp. 20 (W. D. Ark. 1961) .... 51

Reece v. Georgia, 350 IT. S. 85 (1955) ............................... 41

Reed v. Madden, 87 F. 2d 846 (8th Cir. 1937) ............... 6

Saia v. New York, 334 L. S. 558 (1948) ........................... 79

Scott v. Sandford, 60 U. S. (19 How.) 393 (1857) ........... 21

Smith v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 592 (1896) ................. 45

Snypp v. Ohio, 70 F. 2d 535 (6th Cir. 1934) ................... 52

Steele v. Superior Court, 164 F. 2d 781 (9th Cir.), cert.

den., 333 IT. S. 861 (1948)...............................................55, 63

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1880)

39, 43, 64, 67, 73, 74

Swain v. Alabama,------ IT. S .------- , 33 IT. S. Law Week

4231 (decided March 8, 1965)

PAGE

41

VI

Tennessee v. Davis, 100 U. S. 257 (1880) ....................... 6

Texas v. Dorris, 165 F. Supp. 738 (S. D. Tex. 1958) .... 51

Thomas v. State,------ M iss.------- , 160 So. 2d 657 (1964) 92

Townsend v. Sain, 372 U. S. 293 (1963) ........................... 91

United States v. Clark, S. D. Ala., C. A. No. 3438-64,

April 16, 1965 ...................................................................72, 79

United States ex rel. Drury v. Lewis, 200 U. S. 1 (1906) 7

United States ex rel. Flynn v. Fuellhart, 106 Fed. 911

(C. C. W. D. Pa. 1901) ................................................... 6

United States v. Lipsett, 156 Fed. 65 (W. D. Mich. 1907) 6

United States v. Wood, 295 F. 2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961) .... 68

Van Newkirk v. District Attorney, 213 F. Supp. 61

(E. D. N. Y. 1963) ............................................................. 51

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313 (1880) ...............26,39,40,

42, 43, 76

West Virginia v. Laing, 133 Fed. 887 (4th Cir. 1904) .... 6

Williams v. Mississippi, 170 U. S. 213 (1898) ............... 46

Williams v. Wallace, U. S. D. C., M. D. Ala., No. 2181-N,

March 17, 1965 ......................................

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963)

PAGE

71

93

Co n stitu tion al and S tatutory P rovisions

vii

page

U. S. Const., Amend. I .............................................55, 74, 79

U. S. Const., Amend. X III ............................................... 57

U. S. Const., Amend. X I V .....................32, 33, 55, 57, 58, 61,

64, 67, 74, 79

U. S. Const., Amend. X V ................................................ 57

18 U. S.

28 U. S.

28 IT. S.

28 U. S.

28 U. S.

28 U. S.

28 U. S.

28 U. S.

28 U. S.

28 U. S.

28 U. S.

28 U. S.

28 U. S.

28 U. S.

28 U. S.

28 U. S.

42 U. S.

42 U. S.

42 U. S.

42 IT. S.

42 U. S.

42 IT. S.

C. §242 ........................

C. §74 (1940) ....... .

C. §1331 (1958) ......... .

C. §1343(3) (1958) ....

C. §1441 (1958) .........

C. §1442(a)(1) (1958)

C. §1443 (1958) ........

C. §1443(1) (1958) ....

......................................22,54

....................................30, 36

................ 34

...................................... 33

......................................2, 34

......................................6, 85

.............. 1, 20, 36, 52, 55, 56,

57, 58, 60, 62, 63

25, 26, 38, 39, 42, 43, 47, 51,

52, 53, 68, 73, 78, 82, 86, 89

C. §1443(2) (1958).............23,25,39,52,53,54,64,

83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90

C. §1444 (1958) .................................................. 2

C. §1446 (1958) ................................................ - 43

C. §1446 (c) (1958) ............................................. 39

C. §1447 (1958) .................................................. 43

C. §1447(d) ........................................................ 38

C. §2241(c)(2) (1958) ....................................... 6

C. §2251 (1958) ................................ 18

C. §1971 (1958) ...........................................55,68,69

C. §1971(c) .......................................................... 69

C. §1981 (1958) .......................................... 30, 90, 91

C. §1983 (1958) .......30, 33, 53, 54, 55, 58, 66, 67, 68

C. §1985 (1958) ..................... 56

C. §1988 (1958) .............................. 36

V l l l

PAGE

42 U. S. C. A. §1971 (1964) ........................................... 53

42 U. S. C. §2000a-3(a) ..................................................... 69

42 U. S. C. A. §2000a (1965 Supp.) ............................... 53

42 U. S. C. §2000a-2c ......................................................... 69

Rev. Stat. §563, twelfth (1875) .................................... 62

Rev. Stat. §629, sixteenth (1875) ................................. 62

Rev. Stat. §641 (1875) ....................................30,35,36,40,

43, 44, 53, 60, 84, 85, 91

Rev. Stat. §722 (1875) ................................................. 36

Rev. Stat. §1977 (1875) ................................................ 30,67

Rev. Stat. §1979 (1875) .................................30, 33, 53, 61, 67

Rev. Stat. §1980 (1875) ..................................................... 56

Judicial Code of 1911, ch. 231, §31, 36 Stat. 1096

30, 35, 43, 53, 84

Judicial Code of 1911, ch. 231, §297, 36 Stat. 1168 35

Act of September 24, 1789, ch. 20, 1 Stat. 73 ............... 3

Act of September 24, 1789, ch. 20, §11, 1 Stat. 7 8 ........ 3

Act of September 24, 1789, ch. 20, §12, 1 Stat. 79 ...... 4

Act of September 24, 1789, ch. 20, §14, 1 Stat. 8 1 ........ 4

Act of February 13, 1801, ch. 4, §11, 2 Stat. 89, 92,

repealed by Act of March 8, 1802, ch. 8, 2 Stat. 132 .. 3

Act of February 4, 1815, ch. 31, §8, 3 Stat. 198 ........... 5

Act of March 3, 1815, ch. 93, §6, 3 Stat. 233 .............. 5

Act of March 3, 1817, ch. 109, §2, 3 Stat. 396 ............ 5

Act of March 2, 1833, ch. 57, §1, 4 Stat. 632 ................ 5

Act of March 2, 1833, ch. 57, §2, 4 Stat. 632 ................ 5

Act of March 2, 1833, ch. 57, §3, 4 Stat. 633 ............. .. 5

Act of March 2, 1833, ch. 57, §5, 4 Stat. 634 ................ 5

Act of March 2, 1833, ch. 57, §7, 4 Stat. 634 ................ 6

Act of August 29, 1842, ch. 257, 5 Stat. 539 ................... 7

Act of March 3, 1863, ch. 81, 12 Stat. 755 ..................... 8

Act of March 3, 1863, ch. 81, §5, 12 Stat. 755 ............. 39, 57

IX

Act of March 7, 1864, ch. 20, §9, 13 Stat. 17 ............... 9

Act of June 30, 1864, ch. 173, §50, 13 Stat. 241 ........... 9

Act of March 3, 1865, ch. 90, 13 Stat. 507 .............58, 59, 64

Act of March 3, 1865, ch. 90, §1, 13 Stat. 507 . 59

Act of March 3, 1865, ch. 90, §4, 13 Stat. 508 . 59

Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, §1, 14 Stat. 27 .... .......... 22, 30

Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, §2, 14 Stat. 27 ................... 22

Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, §3, 14 Stat. 27 ....11,14, 20, 21,

22, 29, 36, 56, 57, 58, 64, 84, 91

Act of May 11, 1866, ch. 80, 14 Stat. 46 ......... ......... ....13,14

Act of May 11, 1866, ch. 80, §3, 14 Stat. 46 ...............40, 41

Act of July 13, 1866, ch. 184, 14 Stat. 9 8 .... 9

Act of July 13, 1866, §67, 14 Stat. 171 ............... 9

Act of July 13, 1866, §68, 14 Stat. 172 ....................... 9

Act of July 16, 1866, ch. 200, 14 Stat. 173 ................... 59

Act of July 16, 1866, ch. 200, §1, 14 Stat. 173 ............... 59

Act of July 16, 1866, ch. 200, §§6-7, 14 Stat. 174-175 .. 59

Act of July 16, 1866, ch. 200, §14, 14 Stat. 176 ....11, 29, 59

Act of February 5, 1867, ch. 27, 14 Stat. 385 ...............13,14

Act of February 5, 1867, ch. 28, 14 Stat. 385 ......... .....18, 61

Act of February 5, 1867, ch. 28, §1, 14 Stat. 386 .........18, 37

Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, 16 Stat. 140 .......32, 56, 59, 60

Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §1, 16 Stat. 140 ............... 32

Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §§2-7, 16 Stat. 140 .... 32

Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §8, 16 Stat. 142 ............... 32

Act of May 31, 1870, §16, 16 Stat. 144 .........................30, 32

Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §17, 16 Stat. 144 ........... 32

Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §18, 16 Stat. 144 ...........30, 32

Act of February 28, 1871, ch. 99, §16, 16 Stat. 438 ....... 34

Act of April 20, 1871, ch. 22, 17 Stat. 13 ...... ...32, 56, 64, 85

Act of April 20, 1871, ch. 22, §1, 17 Stat. 13 ....30, 33, 36, 53,

56, 57, 60, 61, 67

PAGE

5

PAGE

Act of April 20, 1871, ch. 22, §2, 17 Stat. 13 ............. . 56

Act of March 1, 1875, ch. 114, 18 Stat. 335 ................. 34, 61

Act of March 3, 1875, ch. 137, §§1-2, 18 Stat. 470 ....... 34

Act of March 3, 1887, ch. 373, §2, 24 Stat. 553, as

amended, Act of August 13, 1888, ch. 866, 25 Stat.

435 ...................................................................................... 48

Civil Eights Act of 1957, §131, 71 Stat. 637 ................... 53

Civil Eights Act of 1960, §601, 74 Stat, 90 .................... 53

Civil Eights Act of 1964, Title II, 78 Stat. 241 ....53, 54, 55,

68,79

Civil Eights Act of 1964, §101, 78 Stat. 241 .................. 53

Civil Eights Act of 1964, §901, 78 Stat. 241 .................. 38

Miss. Laws, 1st Extra. Sess. 1962, ch. 6 ....................... 93

Acts of Virginia, 1865-1866 (Act of Jan. 15, 1866) .... 28

O th e r S ources

9 Cong. Deb. (1833)........................................................ 7

Cong. Globe, 27th Cong., 2d Sess. (1942) .................. 8

Cong. Globe, 37th Cong., 3d Sess. (Jan. 27, 1863) .... 9

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1866) ....10,11,12,13,

15,16,17,18,19, 23, 24, 26,

27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 87, 94

110 Cong. Eec. (1964) ...................................................... 38, 77

H. E. Eep. No. 308, 80th Cong., 1st Sess. (1947) ............. 36

Eeviser’s Note to 28 U. S. C. §1443 ................................... 36

ALI Study of the Division of Jurisdiction Between

State and Federal Courts, Commentary, General

Diversity Jurisdiction (Tent. Draft No. 1, 1963) .... 3

X I

PAGE

Amsterdam, Criminal Prosecutions Affecting Federally

Guaranteed Civil Rights: Federal Removal and Ha

beas Corpus Jurisdiction to Abort State Court Trial,

113 U. Pa. L. Rev. 793 (1965)......................................... 19

3 Blackstone, Commentaries 129 (6th ed., Dublin 1775) 36, 37

2 Commager, Documents of American History 2-7 (6th

ed. 1958)............................................................................... 26

Dunning, Essays on the Civil War and Reconstruction

147 (1898) .......................................................................... 11

3 Elliot’s Debates 583 (1836) ............................................. 4

1 Farrand, The Records of the Federal Convention of

1787 (1911) ........................................................................ 2

The Federalist, No. 80 (Hamilton) (Warner, Philadel

phia ed. 1818).................................................................... 2, 4

1 Fleming, Documentary History of Reconstruction

273-312 (photo reprint 1960) ........................................... 26

Frankfurter & Landis, The Business of the Supreme

Court (1927) .................................................................. 36,63

Freed & Wald, Bail in the United States: 1964—A Re

port to the National Conference on Bail and Criminal

Justice (1964) ............................................. -................... 92

Galphin, Judge Pye and the Hundred Sit-Ins, The New

Republic, May 30, 1964 .................................................. 92

Hart & Wechsler, The Federal Court and the Federal

System (1953) ................................................................1> 2, 3

Lusky, Racial Discrimination and the Federal Law: A

Problem in Nullification, 63 Colum. L. Rev. 1163

(1963) ................................................................................ 92

McKay, The Preference for Freedom, 34 N. Y. U. L.

Rev. 112 (1959) ................................................................. 80

McPherson, Political History of the United States

During the Period of Reconstruction 29-44 (1871) ....26, 28

Mishkin, The Federal “ Question” in the District Courts,

53 Colum. L. Rev. 157 (1953) ....................................... 34

1 Morison & Commager, Growth of the American Re

public (4th ed. 1950) ....................................................... 4, 5

1 Warren, The Supreme Court in United States History

(rev. ed. 1932) ................................................................... 4

Wechsler, Federal Jurisdiction and the Revision of the

Judicial Code, 13 Law & Contemp. Prob. 216 (1948) 96

I n the

Itu fr ft States GInurt flf A p p a l s

F oe th e F if t h C ircuit

No. 22104

L ie u ten an t A lbert A. McGee,

Appellant,

—v.—

C it y of M eridian , M ississippi,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

I.

The Background of 28 U. S. C. §1443.

A. Legislative Background

Increasingly since the inception of the Government, fed

eral removal jurisdiction has been expanded by Congress1

to protect national interests in cases “ in which the State

tribunals cannot be supposed to be impartial and un~

1 See H art & W echsler, The Federal Courts and the Federal

System 1147-1150 (1953). Before 1887, the requisites for removal

jurisdiction were stated independently of those for original federal

jurisdiction; since 1887, the statutory scheme has been to author

ize removal generally of cases over which the lower federal courts

have original jurisdiction and, additionally, to allow removal in

special classes of cases particularly affecting the national interest:

suits or prosecutions against federal officers, military personnel,

persons unable to enforce their equal civil rights in the state courts,

2

biassed [sic],” 2 for history has increasingly taught the

wisdom of Hamilton’s insight: “ The most discerning can

not foresee how far the prevalency of a local spirit may be

found to disqualify the local tribunals for the jurisdiction

of national causes . . . ” 3 In the Constitutional Convention

Madison pointed out the need for such protection just be

fore he successfully moved the Committee of the Whole to

authorize the national legislature to create inferior federal

courts :4

Mr. [Madison] observed that unless inferior tri

bunals were dispersed throughout the Republic with

final jurisdiction in many cases, appeals would be multi

plied to a most oppressive degree; that besides, an

appeal would not in many cases be a remedy. What

was to be done after improper Verdicts in State tri

bunals obtained under the biased directions of a depen

dent Judge, or the local prejudices of an undirected

jury? To remand the cause for a new trial would an

swer no purpose. To order a new trial at the supreme

bar would oblige the parties to bring up their wit

nesses, tho’ ever so distant from the seat of the Court.

An effective Judiciary establishment commensurate to

persons acting under color of authority derived from federal law

providing for equal rights or refusing to act inconsistently with

such law, the United States (in foreclosure actions), etc. 28 TJ. S. C.

§§1441-1444 (1958); see H akt & W echsler, supra, at 1019-1020.

2 The F ederalist, No. 80 (Hamilton) ('Warner, Philadelphia ed.

1818), at 429.

3 Id., No. 81, at 439.

4 1 F arrand, T he Records of the F ederal Convention of 1787,

at 125 (1911). Mr. Wilson and Mr. Madison moved the matter

pursuant to a suggestion of Mr. Dickinson.

3

the legislative authority, was essential. A Government

without a proper Executive & Judiciary would be the

mere trunk of a body without arms or legs to act or

move.5

The early Congresses made very sparing use of the power

which was thus given them by the Constitution; during

nearly three quarters of a century following the Judiciary

Act of 1789,6 they acted largely on the principle “ that pri

vate litigants must look to the state tribunals in the first

instance for vindication of federal claims, subject to limited

review by the United States Supreme Court.” 7 The fed

eral trial courts were employed only for the limited federal

specialties; no general federal question jurisdiction was

created.8 Original civil diversity jurisdiction was given9

— responding then, as today, to “ the possible shortcomings

of State justice,” particularly the localization of trial in

parochial communities where “ justice is likely to be im

peded by the provincialism of the local judge and jury, the

tendency to favor one of their own against an outsider, and

the machinations of the local ‘court house gang’ ” 10— and

5 Id. at 124.

6 Act of Sept. 24,1789, ch. 20,1 Stat. 73.

7 H akt & W eclisler, The F ederal Courts and the F ederal

System 727 (1953).

8 Except by the federalist Act of Feb. 13, 1801, ch. 4, §11, 2

Stat. 89, 92, quickly repealed by the Act of March 8, 1802, eh. 8,

2 Stat. 132.

9 Act of Sept. 24,1789, ch. 20, §11,1 Stat. 78.

10 ALT Study of the D ivision of Jurisdiction Between State

and F ederal Courts, Commentary, General Diversity Jurisdic

tion, at 41 (Tent. Draft No. 1, 1963).

4

civil removal jurisdiction was given in three sorts of cases11

where it was particularly feared that local prejudice might

impair national concerns. In criminal cases, however, the

federal trial courts were entirely excluded from incursion

into state proceedings;12 section 14 of the Judiciary Act

expressly excepted state prisoners from the federal habeas

corpus authority.13

Experience seen showed, however, the potential of the

state criminal process for destruction of vital national con

cerns. Congress responded with limited grants of federal

trial court jurisdiction, in removal and habeas corpus. In

1815, confronted by New England’s resistance to the War

of 1812,14 Congress in a customs act allowed removal of suits

or criminal prosecutions

11 The Act of Sept. 24, 1789, ch. 20, §12, 1 Stat. 79, authorized

removal in the following classes of cases where more than $500

was in dispute: suits by a citizen of the forum state against an

outstater; suits between citizens of the same state in which the

title to land was disputed and the removing party set up an

outstate land grant against his opponent’s land grant from the

forum state; suits against an alien. The first two classes were

specifically described by Hamilton as situations “ in which the state

tribunals cannot be supposed to be impartial,” The Federalist

No. 80, at 432 (Warner ed. 1818). Madison speaking of state

courts in the Virginia convention, amply covered the third: “We

well know, sir, that foreigners cannot get justice done them in

these courts. . . . ” 3 Elliot’s Debates 583 (1836).

12 The jealousy of the States as regards their criminal process

is indicated by the furor aroused by Supreme Court assumption

of jurisdiction to review federal questions in state criminal cases

as late as 1821. Cohens v. Virginia, 19 U. S. (6 Wheat.) 264

(1821); see 1 W arben, The Supreme Court in United States

H istory 547-59 (rev. ed. 1932).

13 Except where it was necessary to bring them into court to

testify. Act of Sept. 24, 1789, ch. 20, §14, 1 Stat. 81.

14 See 1 Morison & Commager, Growth of the American Republic

426-29 (4th ed. 1950).

5

against any collector, naval officer, surveyor, inspector,

or any other officer, civil or military, or any other per

son aiding or assisting, agreeable to the provisions of

this act, or under colour thereof, for any thing done,

or omitted to be done, as an officer of the customs, or

for any thing done by virtue of this act or under colour

thereof.15

In 1833, confronted by South Carolina’s opposition to the

tariff,16 Congress enacted the famed Force Act, giving the

President extensive power to use the military forces of the

United States to protect federal customs officers and sup

press resistance to the customs laws;17 extending the civil

jurisdiction of the federal courts to all cases arising under

the revenue laws;18 authorizing removal of any suit or

prosecution

against any officer of the United States, or other per

son, for or on account of any act done under the rev

enue laws of the United States, or under colour there

of, or for or on account of any right, authority, or title,

set up or claimed by such officer, or other person under

any such law of the United States ;19

15 Act of Feb. 4, 1815, ch. 31, §8, 3 Stat. 198; Act of March 3,

1815, ch. 93, §6, 3 Stat. 233. Both enactments were temporary

legislation. Their removal provisions were extended four years

by Act of March 3, 1817, eh. 109, §2, 3 Stat. 396.

16 See 1 Morison & Commager, op. cit., supra,, note 14, 475-85.

17 Act of March 2,1833, eh. 57, §§1, 5, 4 Stat. 632, 634.

18 Act of March 2,1833, ch. 57, §2, 4 Stat. 632.

19 Act of March 2, 1833, ch. 57, §3, 4 Stat. 633. Section 2 of the

act envisioned that under certain circumstances private individ

uals, as well as federal officers, might take or hold property pur

suant to the revenue laws.

6

and adding to the federal habeas corpus jurisdiction

power to grant writs of habeas corpus in all cases of

a prisoner or prisoners, in jail or confinement, where

he or they shall be committed or confined on, or by any

authority or law, for any act done, or omitted to be

done, in pursuance of a law of the United States, or

any order, process, or decree, of any judge or court

thereof.20

The act’s evident purpose was to exclude state court juris

diction in cases affecting the tariff,21 and to give the federal

20 Act of March 2,1833, eh. 57, §7, 4 Stat. 634.

21 This purpose is apparent as respects the removal jurisdiction,

which was sustained in Tennessee v. Davis, 100 U. S. 257 (1880),

against constitutional complaints that “ it is an invasion of the

sovereignty of a State to withdraw from its courts into the courts

of the general government the trial of prosecutions for alleged

offenses against the criminal laws of a State.” Id. at 266. The

revenue officer removal provisions were continued in successive

judiciary acts until 1948, when they were extended to encompass

all federal officers and persons acting under them. 28 U. S. C.

§1442(a)(l) (1958). As for the habeas corpus grant, continued

in substance in present 28 U. S. C. §2241 (c )(2 ) (1958), this has

always been construed as directing the federal courts to entertain

petitions for the writ in advance of state trial in cases where

federal officers are prosecuted, see the authorities collected in the

briefs and opinion in In re Neagle, 135 U. S. 1 (1890) • e.g., Reed

v. Madden, 87 F. 2d 846 (8th Cir. 1937) ; In re Fair, 100 Fed. 149

(C. C. D. Neb. 1900); United States ex rel. Flynn v. Fuellhart,

106 Fed. 911 (C. C. W. D. Pa. 1901); United States v. Lipsett,

156 Fed. 65 (W. D. Mich. 1907); Ex parte Warner, 21 F. 2d 542

(N. D. Okla. 1927); Brown v. Cain, 56 F. Supp. 56 (E. D. Pa.

1944); Lima v. Lawler, 63 F. Supp. 446 (E. D. Va. 1945), or

where private citizens acting under federal officers are prosecuted,

Anderson v. Elliott, 101 Fed. 609 (4th Cir. 1900), dism’d 22 S. Ct.

930 (1902) ; West Virginia v. Laing, 133 Fed. 887 (4th Cir. 1904).

Discharge of federal officers has sometimes been denied after evi

dentiary hearing where the evidence did not preponderantly show

that the officer was acting within the scope of his federal authority.

7

courts plenary power to enforce the tariff against concerted

state resistance, including state judicial resistance: it was

“ apparent that the constitution of the courts in South Caro

lina makes its necessary to give the revenue officers the

right to sue in the federal courts.” 22

The federal habeas corpus jurisdiction was extended

again in 1842 to authorize release of foreign nationals and

domiciliaries held under state law or process on account of

any act claimed to have been done under color of foreign

authority depending on the law of nations.23 This extension

was occasioned by the McLeod case,24 in which the New

York courts nearly provoked an international incident by

refusing to relinquish jurisdiction over a British subject

held for murder who claimed that the acts with which he

was charged were done under British authority. McLeod

was acquitted at his trial, but the need for an expeditious

federal remedy to short-cut the state court process in such

United States ex rel. Drury v. Lewis, 200 U. S. (1906); Birsch

v. Tumbleson, 31 F. 2d 811 (4th Cir. 1929); Castle v. Lewis, 254

Fed. 917 (8th Cir. 1918) ; Ex parte Tilden, 218 Fed. 920 (D. Ida.

1914). The evidentiary standard is discussed in Brown v. Cain

and Lima v. Lawler, supra. These cases do not reflect hesitation

to use the federal writ to abort state trial in any case in which

the interests of the federal government are affected; they indicate

only that, in each case, the federal interest was not sufficiently

shown on the facts. See In re Matthews, 122 Fed. 248 (E. D. Ky.

1902), and particularly In re Miller, 42 Fed. 307 (E. D. S. C.

1890); cf. Ex parte United States ex rel. Anderson, 67 F. Supp.

374 (S. D. Fla. 1946), decided on same grounds without a hearing.

22 9 Cong. Deb. 260 (Jan. 29, 1833). The speaker is Senator

Wilkins, who reported the bill, id. at 150 (Jan. 21, 1833), and

managed it in the Senate, id. at 246 (Jan. 28, 1833). See also,

id. at 329-32 (Feb. 2, 1833) (remarks of Senator Frelinghuysen).

23 Act of August 29,1842, eh. 257, 5 Stat. 539.

24 See People v. McLeod, 25 Wend. 482 (Sup. Ct. N. Y. 1841).

8

cases was strongly felt: “ If satisfied of the existence in

fact and validity in law of the [plea in] bar, the federal

jurisdiction will have the power of administering prompt

relief.” 25 Again, as in 1815 and 1833, the scope of federal

intrusion was narrow.

But the Civil War and its aftermath changed the con

gressional temper sharply. During and after the War, Con

gress multiplied the uses of the federal courts and, in par

ticular, their uses to anticipate the state criminal process.

By the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act of 186326 it immu

nized from state civil and criminal liability persons making

searches, seizures, arrests and imprisonments under presi

dential orders during the existence of the rebellion; to in

sure this protection, it provided in section 5 of the act for

removal of all suits and criminal prosecutions

against any officer, civil or military, or against any

other person, for any arrest or imprisonment made, or

other trespasses or wrongs done or committed, or any

act omitted to be done, at any time during the present

rebellion, by virtue or under color of any authority de

rived from or exercised by or under the President of

the United States, or any act of Congress.27

The debates preceding passage of the act reflected congres

sional concern that federal officers could not receive a fair

25 Senator Berrien, at Cong. Globe, 27th Cong., 2d Sess. 444

(4/26/42). Mr. Berrien, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Com

mittee, reported and managed the bill which became the act. Id.

at 443. See the discussion of the act in In re Neagle, 135 U S 1

71-72, 74 (1890).

26 Act of March 3,1863, ch. 81,12 Stat. 755.

2712 Stat. 756.

9

trial in hostile state courts, and that the appellate super

vision of the Supreme Court of the United States would

be inadequate to rectify the decisions of lower state tri

bunals having the power to find the facts.28

In 1864 and 1866,29 Congress also extended the customs-

officer removal provisions of the 1833 Force Act to cover

civil and criminal cases involving internal revenue collec

tion. In their final 1866 form, these provisions authorized

federal removal of suits and prosecutions “ against any

officer of the United States appointed under or acting by

authority of [the revenue laws] . . . or against any person

acting under or by authority of any such officer on account

of any act done under color of his office,” or against persons

claiming title from such officers, where the cause concerned

the property and affected the validity of the revenue laws.

During the first months of the Thirty-Ninth Congress,

Union military commanders in the defeated South trans

28 Cong. Globe, 37th Cong., 3d Sess. 534-38 (Jan. 27, 1863).

29 Act of March 7, 1864, ch. 20, §9, 13 Stat. 17; Act of June 30,

1864, ch. 173, §50, 13 Stat. 241; Act of July 13, 1866, eh. 184, 14

Stat. 98. By the 1866 act Congress (a) generally amended the

revenue provisions of the act of June 30, 1864; (b) in §67, 14

Stat. 171, authorized removal of any civil or criminal action

against any officer of the United States appointed under or

acting by authority of [the Act of June 30, 1864, and amend

ments thereto] . . . or against any person acting under or

by authority of any such officer on account of any act done

under color of his office, or against any person holding prop

erty or estate by title derived from any such officer, con

cerning such property or estate, and affecting the validity

of [the revenue laws] . . . ;

and (c) in §68, 14 Stat. 172, repealed the removal provisions

(§50) of the Act of June 30, 1864, and provided for the remand

to the state courts of all pending removed cases which were not

removable under the new 1866 removal provisions.

1 0

ferred from the state courts to national military tribunals

civil and criminal jurisdiction over cases involving Union

soldiers, loyalists and Negroes.30 Recognizing the wisdom

of this transfer, and intensely aware of the hostility and

anti-Union prejudice of the Southern state courts,31 whose

process was being used to harass the unionists and freed-

men,32 that Congress took four important steps to curb

the state courts.

30 See General Sickles’ order, set out at Cong. Globe, 39th Cong.,

1st Sess. 1834 (April 7, 1866), providing that military courts

“shall have, as against any and all civil courts, exclusive juris

diction in all cases where freedmen and other persons of color

are directly or indirectly concerned, until such persons shall be

admitted to the State courts as parties and witnesses with the same

rights and remedies accorded to all other persons,” unless the

Negroes concerned filed a written stipulation submitting the pro

ceeding to the state court. Cf. id. at 320 (Jan. 19, 1866) (General

Grant’s order).

31E.g., id. at 1526 (March 20, 1866) (remarks of Representative

McKee, of Kentucky), 1527 (remarks of Representatives Garfield

and Smith, of Kentucky), 1529 (remarks of Representative Cook,

who reported the bill and was its floor manager, see note 117

supra), 2054, 2063 (April 20, 1866) (remarks of Senator Clark).

Clark pointed out that hostile state legislatures could not be looked

to for redress of the discriminations practiced by hostile state

judges. Id. at 2054. The only relief for the Union men was access

to the federal courts: “ There is where they are most likely to

have their rights protected. There is where local prejudices are

frowned down.” Id. at 1526 (March 20, 1866) (remarks of Rep

resentative McKee, of Kentucky); see id. at 1528 (remarks of

Representative Smith, of Kentucky), 1529-30 (remarks of Rep

resentative Cook) ; cf. id. at 1387 (March 14, 1866) (remarks of

Representative Cook). See also the debates on the amendatory

freedmen’s bureau bills: id. at 320 (Jan. 19, 1866) (remarks of

Senator Trumbull), 339 (Jan. 22, 1866) (remarks of Senator

Cresswell), 744 (Feb. 8, 1866) (remarks of Senator Sherman),

941 (Feb. 20, 1866) (remarks of Senator Trumbull), 657 (Feb. 5,

1866) (remarks of Representative Eliot), 2774-77 (May 23, 1866)

(remarks of Representative Eliot).

32 See text and notes at notes 40-46, infra.

11

First, by the Amendatory Freedmen’s Bureau Act,33 it

approved and expressly authorized the supersession of

state courts by Union military tribunals throughout the

South until the rebellious States were restored to order and

their representatives readmitted to Congress.34 In this, the

33 Act of July 16, 1866, eh. 200, §14, 14 Stat. 176. Concerning

supersession of state civil and criminal jurisdiction by military

tribunals under the act, see D unning, Essays on the Civil W ar

and Reconstruction 147, 156-63 (1898).

34 Section 14 of the Amendatory Freedmen’s Bureau Act, note 33

supra, provided that in every State where “the ordinary course of

judicial proceedings has been interrupted by the rebellion,” or

where the State’s “constitutional relations to the government have

been practically discontinued by the rebellion,” certain enumerated

rights—an enumeration substantially identical to that of §1 of the

Civil Rights Act—should be secured to all citizens without respect

to race or color. Where the course of judicial proceedings had

been interrupted, the President through the Freedmen’s Bureau

was to “ extend military protection and have military jurisdiction

over all cases and questions concerning the free enjoyment of such

immunities and rights,” this jurisdiction to cease in every State

when the state and federal courts therein were no longer disturbed

in the peaceable course of justice, and after the State was re

stored to its constitutional relations and its representatives seated

in Congress. The jurisdiction appears of slightly different scope

than that given by the first amendatory freedmen’s bureau bill,

S. 60 of the Thirty-ninth Congress, a companion bill to the civil

rights bill, infra, which failed of passage over President

Johnson’s veto. The predecessor bill authorized military jurisdic

tion over all eases affecting the Negroes, but only when in a State

the ordinary course of judicial proceedings had been interrupted

by the rebellion and the same enumerated rights were discrimina-

torily denied to Negroes; this jurisdiction to cease “whenever the

discrimination on account of which it is conferred ceases,” and

in any event so soon as the state and federal courts were no longer

disturbed and the State’s constitutional relations were restored.

In debate on the first bill, Senator Trumbull, who introduced,

reported and managed it, Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 129

(Jan. 5, 1866), 184 (Jan. 11, 1866), 209 (Jan. 12, 1866), resisted

attacks on the jurisdiction by repeated insistence that the bill

operated only where the civil courts were overthrown. Id. at 320-22

(Jan. 19, 1866), 347 (Jan. 22, 1866), 937-38 (Feb. 20, 1866). In

12

Thirty-Ninth Congress—like the military commanders be

fore it—intended that nationally responsible courts should

sit at the trial level, so that the unionists and freedmen

might be protected not only against explicitly discrimina

tory Southern state statutes, but also against Southern

state judicial maladministration of statute law apparently

fair on its face.35

this he manifested no deference to the state courts, for the principal

attack was upon the institution of military tribunals, as distin

guished from federal civil tribunals, see, e.g., the President’s veto

messages set out id. at 915-17 (Feb. 19, 1866), 3849-50 (July 16,

1866), and it was to this attack that Trumbull replied. See id. at

322 (Jan. 19, 1866), 937-38 (Feb. 20, 1866). He explained that

the civil rights bill applied, and could be enforced, only in parts

of the country where the civil courts were functioning; that the

amendatory freedmen’s bureau bill applied only where they were

not. Id. at 3412 (June 26, 1866) (debate on the second bill). See

also id. at 2773 (May 23, 1866) (remarks of Bepresentative Eliot,

who reported and managed the second bill, id. at 2743 (May 22,

1866), 2772 ̂ (May 23, 1866)). And in a speech concerned with

both the civil rights and first amendatory freedmen’s bureau bills,

Trumbull appears to view them as having substantially similar

scope. Id. at 322-23 (Jan. 19, 1866).

_35 Particularly significant is an order of General Terry in Vir

ginia, March 12, 1866, set out at Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st

Sess. 1834 (April 7, 1866). The Virginia legislature on February

28, 1866, had passed a statute providing that all laws respecting

crimes, punishments, and criminal proceedings should apply equally

to Negroes and whites, and that Negroes should be competent wit

nesses in all cases in which Negroes were involved. General Terry’s

order thereupon restored to the civil courts the jurisdiction there

tofore exercised by the military tribunals in all criminal matters

affecting the freedmen, but provided an elaborate system of pro

tection to assure that the Virginia laws would be fairly admin

istered as they were written. Under part III of the order, assistant

superintendents of the Freedmen’s Bureau were required to attend

in person all criminal trials or preliminary hearings in which

Negroes were parties or witnesses. Under part IV, the duties of

the assistants were spelled out: they were not to interfere with

the court, or act as attorneys, although they might make friendly

suggestions to the Negroes concerned. “ They will, however, make

13

Second, the same Congress substantially amended the

removal procedures under the Habeas Corpus Suspension

Act of 1863, supra, in order to prevent their obstruction by

the state courts. The Act of May 11, 1866, chapter 80,* 36

facilitated removal practice ;37 the Act of February 5, 1867,

immediate report of any instance of oppression or injustice against

a colored party, whether prosecutor or defendant, and also in

case the evidence of colored persons should be improperly rejected

or neglected.” Under part Y, the assistants were to examine and

report if in any instance a prosecutor, magistrate, or grand jury

had refused justice to a colored person by improperly neglecting

a complaint or refusing to receive a sworn information, so that

by reason of partiality a trial or prosecution was avoided. Part VI

required the assistants to make monthly detailed reports con

cerning the effect of the order on the interests of Negroes, “whether

they have been treated with impartiality and fairness, and the

law respecting their testimony carried out in good faith or other

wise.” General Grant’s order of January 12, 1866, had directed

the commanders to protect Negroes from prosecution in the rebel

States “ charged with offenses for which white persons are not

prosecuted or punished in the same manner and degree.” Id. at 320

(Jan. 19, 1866). Senator Trumbull, questioned concerning Grant’s

order, said that he did “ indorse the order and every word in it.”

I bid.

3614 Stat. 46.

37 Section 1 of the Act of May 11, 1866, declared that any act or

omission under authorized military order came within the purview

of the sections of the act of 1863 which made acts or omissions un

der presidential order immune from civil and criminal liability and

allowed removal to the federal courts by defendants charged in

state courts in respect of such acts. 14 Stat. 46. The section was

responsive to state court decisions requiring that a defendant pro

duce an order from the President himself in order to come within

the 1863 act. Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 1387 (March 14,

1866) (remarks of Representative Cook, who reported the bill, id.

at 1368 (March 13, 1866), and was its floor manager, id. at 1387

(March 14, 1866)). Section 2 of the 1866 act specified the means

by which the military order relied on might be proved. Section 3

extended the time for removal up to the point of empaneling a jury

in the state court, and eliminated the 1863 requirement of a removal

bond. Section 4 directed that upon the filing of a proper removal

14

chapter 27,38 authorized the issuance of writs of habeas

corpus cum causa by the federal courts to bring before

them any imprisoned defendants whose cases had been re

moved.39 The debates on the first of these remedial enact

ments are particularly revealing: they demonstrate be

yond peradventure Congress’ distrust of, and unwilling

ness to leave the vindication of federal interests to, the

state judiciary. “ Now, it so happens, as the rebellion is

petition all state proceedings should cease, and that any state court

proceedings after removal should be void and all parties, judges,

officers, or other persons prosecuting such proceedings should be

liable for damages and double costs to the removing party. 14 Stat.

46. Section 5 directed the clerk of the state court to furnish copies

of the state record to a party seeking to remove, and permitted that

party to docket the removed ease in the federal court without at

taching the state record in case of refusal or neglect by the state

court clerk. 14 Stat. 46-47. These latter provisions were intended

to alter procedural requirements upon which the state courts had

seized to obstruct removal. E.g., Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess.

1387-88 (March 14, 1866) (remarks of Representative Cook), 2054

(remarks of Senator Clark, who reported the bill, id. at 1753

(April 4, 1866), and was its floor manager, id. at 1880 (April 11,

1866)).

3814 Stat. 385.

39 The act was reported by the Judiciary Committee in each

house. Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 4096 (July 24, 1866)

(House), 4116 (Senate). Its purpose was to take from state cus

tody defendants whose cases had been removed into the federal

courts, id. at 4096 (July 25, 1866) (remarks of Representative Wil

son, who reported the bill and was its floor manager, ibid.) • Cong.

Globe, 39th Cong., 2d Sess. 729 (Jan. 25, 1867) (remarks of Sena

tor Trumbull, chairman of the Judiciary Committee, who reported

the bill, Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 4116 (July 24, 1866),

and was it floor manager, Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 2d Sess. 729

(Jan. 25, 1867)), and thereby to permit the federal court to de

termine the validity of the defendant’s detention under arrest, ibid.

(remarks of Senator Johnson).

The civil rights removal provisions of the Act of April 9, 1866,

ch. 31, §3, 14 Stat. 27, infra, adopted the procedures of the 1863 re

moval sections “and all acts amendatory thereof.”

15

passing away, as the rebel soldiers and officers are return

ing to their homes, that I may say thousands of suits are

springing up all through the land, especially where the

rebellion prevailed, against the loyal men of the country

who endeavored to put the rebellion down.” 40 “ [Sjuits are

springing up from one end to the other; and these rebel

courts are ready to decide against your Union men and

acquit the rebel soldier.” 41 A great many vexatious suits

have been brought, and they are still pending, and instances

have been known—they exist now—where Federal officers

have been pushed very hard and put to great hardships

and expense, and sometimes convicted of crime, for doing

things which were right in the line of duty, and which they

were ordered to do and which they could not refuse to

do.” 42 In Kentucky, “ they are harassing, annoying, and

40 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2021 (April 18, 1866) (re

marks of Senator Clark). Senator Clark reported and managed the

bill which became the act. Note 37 supra.

The oppressive volume of state litigation against Union men was

frequently noted in debate. E.g., Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess.

1880 (April 11, 1866) (remarks of Senator Clark), 1983 (April 17,

1866) (remarks of Senator Trumbull, Chairman of the Judiciary

Committee) : It was said that there were over 3000 cases pending

in Kentucky alone. Id. at 1526, 1529 (March 20, 1866) (remarks of

Representative McKee, of Kentucky), 1983 (April 17, 1866) (re

marks of Senator Clark), 2021 (April 18, 1866) (remarks of Sena

tor Clark), 2054 (April 20, 1866) (remarks of Senator Wilson).

41 Id. at 2021 (April 18, 1866) (remarks of Senator Clark).

42Id. at 1880 (April 11, 1866) (remarks of Senator Clark).

Recognition that the cost of defending suits and prosecution might

itself be ruinous to defendant Union men found strong expression

in the comments of Senators Edmunds, id. at 2063, 2064 (April 20,

1866), and Howe, id. at 2064, in debate of an amendment offered

by Edmunds providing that the Secretary of War should defend

all actions within the scope of the bill at government expense, and

should indemnify the individual defendant for damages, costs, fines

and expenses. The amendment was opposed on the ground that it

1.6

even driving ont of the State the men who stood true to

the flag by suits under the legislation and judiciary rulings

would overburden the Government’s financial resources, encourage

litigation, encourage collusive actions, result in larger jury verdicts

in damage actions, and that defendants could be adequately pro

tected by private indemnifying bills. Both Edmunds’ amendment

and one by Howe providing for government defense of removed

actions, were defeated. Id. at 2064-66. Apart from questions of

expense, the injury to state-court defendants resulting from delay

in the vindication of their federal rights was pointed up by the

debate between Senators Doolittle and Hendricks, who opposed the

provision making state judges civilly liable for proceeding after

removal of a cause to the federal court, and Senators Stewart and

Clark, who supported it. Senator Doolittle said that it should not

be presumed state judges would flout the federal removal statute.

Senator Stewart asked, in effect, what relief there was for an in-

dieted defendant if the state court did flout removal, pointing out

that a state judge could force an indictment to trial even without

the cooperation of the state prosecutor.

Me. H endricks. The Senator as a lawyer knows that this

will be the effect of i t : if the application takes away the juris

diction of the State courts then the remedy, of course, if the

plaintiff persists in the case, is in the appellate courts, and

finally, on an appeal, in the Supreme Court of the United

States, inasmuch as the validity of this law, an act of Congress,

would be in question.

Me. Stewaet. But suppose the judge goes on and convicts

the man and sends him to the penitentiary, he must lie there

until the case can be heard in the Supreme Court, three or four

years hence.

Me . D oolittle. How can he send him to the penitentiary?

No officer is allowed to do it. Will the judge put him there

himself ?

Me. Stewaet. The judge can order the officer to put him

there.

Me. Doolittle. What if he does if the officer cannot put

him there? If every officer to execute a decree of the court

is made responsible, how can the judge do it?

Mr. Stewaet. The judge has jurisdiction over the officer,

and he can order him to do it, and if he does not do it the

judge can call upon the power of the State if he has juris

diction.

Mr. Clark. I desire to make but one suggestion in answer

to the Senator from Wisconsin, and that is one of fact. He

17

of Kentucky. There no protection is guaranteed to a Fed

eral soldier.” * 43 “ [I]n another county of that State the

grand jury indicted every Union judge, sheriff, and clerk

of the election of August, 1865. In addition to that every

loyal man who had been in the Army and had, under the

order of his superior officer, taken a horse, was indicted.” 44

Discrimination against the Union men “ is the rule in Ken

tucky, except in one solitary district, and the Legislature

at its last session inaugurated means of removing that

judge, simply because he dared to carry out this act of the

Federal Congress [the 1863 removal statute].” 45 “ There

must be some way of remedying this crying evil, and these

men who have been engaged in the defense of the country

cannot be permitted to be persecuted in this sort of way.

Their life becomes hardly worth having, if, after having

driven the rebels out of their country and subdued them,

says if it were necessary that these judges should be proceeded

against he would not object. I hold in my hand a communica

tion from a member of the other House from Kentucky, in

which he says that all the judicial districts of Kentucky, with

the exception of one, are in the hands of sympathizing judges.

They entirely disregard the act to which this is an amendment.

They refuse to allow the transfer, and proceed against these

men as if nothing had taken place. Here is not the assumption

that these judges will not do this; here is the fact that they do

not do it, and it is necessary that these men should be pro

tected.

Id. at 2063 (April 20, 1866). Senators Stewart and Clark prevailed

in the vote on an amendment seeking to strike the provision making

the state judges liable. Ibid.

43 Id. at 1526 (March 20, 1866) (remarks of Representative

McKee, of Kentucky).

44Id. at 1527 (remarks of Representative Smith, of Kentucky).

See id. at 1526 (remarks of Representative McKee, of Kentucky).

45 Id. at 1526 ; see id. at 2063 (April 20, 1866) (remarks of Sena

tor Clark).

18

those rebels are to be permitted to return and harass them

from morning until night and from night till morning, and

make their life a curse for that very defense which they

have given your country.” 46

Third, the Thirty-Ninth Congress extended the federal

habeas corpus jurisdiction to “ all cases where any person

may be restrained of his or her liberty in violation of the

constitution, or of any treaty or law of the United

States . . . , ” 47 made elaborate provision for summary

hearing and summary disposition by the federal judges,

and provided that:

pending such proceedings or appeal, and until final

judgment be rendered therein, and after final judgment

of discharge in the same, any proceeding against such

person so alleged to be restrained of his or her liberty

in any State court, or by or under the authority of any

State, for any matter or thing so heard and deter

mined, or in process of being heard and determined,

under and by virtue of such writ of habeas corpus,

shall be deemed null and void.48

46 Id. at 2054.

47 Act of February 5, 1867, ch. 28, 14 Stat. 385.

48 Act of February 5, 1867, ch. 28, §1, 14 Stat. 386. The successor

to this provision is present 28 U. S. C. §2251 (1958), which au

thorizes any federal justice or judge before whom a habeas corpus

proceeding is pending, to “stay any proceeding against the person

detained in any State court or by or under the authority of any

State for any matter involved in the habeas corpus proceeding,”

before judgment, pending appeal, or after final judgment of dis

charge in the habeas case. State proceedings after granting of a

stay are declared void, but if no stay is granted state proceedings

are “as valid as if no habeas corpus proceedings or appeal were

pending.”

19

This statute was designed “ to enlarge the privilege of the

writ of habeas [sic] corpus, and make the jurisdiction of

the courts and judges of the United States coextensive with

all the powers that can be conferred upon them,” 49 to give

any person “ held under a State law in violation of the

Constitution and laws of the United States . . . recourse to

United States courts to show that he was illegally impris

oned in violation of the Constitution or laws of the United

States.” 50 It was “ legislation . . . of the most comprehen

sive character [bringing] . . . within the habeas corpus

jurisdiction of every court and of every judge every pos

sible case of privation of liberty contrary to the National

Constitution, treaties, or laws. It is impossible to widen

this jurisdiction.” 51 Recent exhaustive study of the his

tory of the 1867 habeas corpus statute confirms that its

purpose was to give a summary and imperious federal

judicial procedure for the pretrial abortion of state crimi

nal proceedings,52 and fully supports the Supreme Court’s

observation that “ Congress seems to have had no thought

. . . that a state prisoner should abide state court deter-

49 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 4151 (July 25, 1866) (re

marks of Representative Lawrence, who reported the bill and was

its manager in the House).

50 Id. at 4229 (July 27, 1866) (remarks of Senator Trumbull,

Chairman of the Judiciary Committee, who reported the bill and

was its manager in the Senate, id. at 4228).

51Ex parte McCardle, 73 U. S. (6 Wall.) 318, 325-26 (1868).

52 Amsterdam, Criminal Prosecutions Affecting Federally Guar

anteed Civil Bights: Federal Removal and Habeas Corpus Jurisdic

tion to Abort State Court Trial, 113 U. Pa. L. Rev. 793 (1965).

This article is concerned with the federal civil rights removal juris

diction as well as with federal habeas corpus power to anticipate

state criminal trials. The historical materials and some of the argu

ments in this brief are supported by the article.

20

initiation of his constitutional defense—the necessary pred

icate of direct review by [the Supreme Court] . . . —before

resorting to federal habeas corpus. Rather, a remedy al

most in the nature of removal from the state to the federal

courts of state prisoners’ constitutional contentions seems

to have been envisaged.” Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391, 416

(1963). See also, In re Neagle, 135 IJ. S. 1 (1890).

Fourth, and most significant, on April 9, 1866, Congress

enacted the first major civil rights act.53 Its third section,

the ancestor of the present 28 U. S. C. §1443 (1958), on

which appellants rely to sustain removal, provided:

Sec. 3. And be it further enacted, That the district

courts of the United States, within their respective

districts, shall have, exclusively of the courts of the

several States, cognizance of all crimes and offences

committed against the provisions of this act, and also,

concurrently with the circuit courts of the United

States, of all causes, civil and criminal, affecting per

sons who are denied or cannot enforce in the courts

or judicial tribunals of the State or locality where

they may be any of the rights secured to them by the

first section of this act; and if any suit or prosecution,

civil or criminal, has been or shall be commenced in

any State court, against any officer, civil or military,

or other person, for any arrest or imprisonment, tres

passes, or wrongs done or committed by virtue or under

color of authority derived from this act or the act estab

lishing a Bureau for the relief of Freedman and Refu

gees, and all acts amendatory thereof, or for refusing

63 Act of April 9,1866, ch. 31,14 Stat. 27.

2 1

to do any act upon the ground that it would be incon

sistent with this act, such defendant shall have the

right to remove such cause for trial to the proper

district or circuit court in the manner prescribed by

the “ Act relating to habeas corpus and regulating

judicial proceedings in certain cases,” approved March

three, eighteen hundred and sixty-three, and all acts

amendatory thereof. The jurisdiction in civil and

criminal matters hereby conferred on the district and

circuit courts of the United States shall be exercised

and enforced in conformity with the laws of the United

States, so far as such laws are suitable to carry the

same into effect; but in all cases where such laws are

not adapted to the object, or are deficient in the pro

visions necessary to furnish suitable remedies and

punish offences against law, the common law, as modi

fied and changed by the constitution and statutes of

the State wherein the court having jurisdiction of the

cause, civil or criminal, is held, so far as the same is

not inconsistent with the Constitution and laws of the

United States, shall be extended to and govern said

courts in the trial and disposition of such cause, and,

if of a criminal nature, in the infliction of punishment

on the party found guilty.54

The purpose of this 1866 act—“An Act to protect all

Persons in the United States in their Civil Rights and to

furnish the Means of their Vindication”—was to upset

the Dred Scott decision55 by declaring the Negroes citizens,

54 Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, §3, 14 Stat. 27.

55 Scott v. SandforcL, 60 U. S. (19 How.) 393 (1857).

22

to establish as an incident of that citizenship “ the same

right” to contract, hold property, etc., and “ to full and

equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security

of person and property” as enjoyed by whites (section l ) ,56

to deter by criminal penalties the deprivation of that

“ right” (section 2),57 and to give the Negroes access to

federal courts for protection of the right (section 3).58 The

structure of section 3 was: (1) to create original federal

jurisdiction in the case of persons who were denied or could

not enforce their §1 rights in the state courts; (2) to create

removal jurisdiction in cases where any “ such person” was

sued or prosecuted in a state court; and (3) to create addi

tional removal jurisdiction over suits or prosecutions

56 Act of April 9,1866, ch. 31, §1,14 Stat. 27, provided:

That all persons born in the United States and not subject to

any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby

declared to be citizens of the United States; and such citizens,

of every race and color, without regard to any previous condi

tion of slavery or involuntary servitude, except as a punish

ment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly con

victed, shall have the same right, in every State and Territory

in the United States, to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, and give evidence, to inherit, purchase, lease, sell,

hold and convey real and personal property, and to full and

equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of

person and property, as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall

be subject to like punishment, pains, and penalties, and to none

other, any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, to the

contrary notwithstanding.

57 Act of April 9, 1866, eh. 31, §2, 14 Stat. 27, made it criminal

for any person, acting under color of law, to subject another to

deprivation of any right secured or protected by the act (see §1,

note 56, supra), or to different punishments, pains, or penalties by

reason of race, color, or previous servitude. The section is the fore

bearer of present 18 U. S. C. §242 (1958).

58 Act of April 9,1866, ch. 31, §3,14 Stat. 27.

23

against persons on account of alleged wrongs committed

under color of the 1866 act or the Freedmen’s Bureau Acts.

Little appears in the legislative history, however, that is

helpful in precise construction of any of these jurisdic

tional grants.59 Since the basic substantive right given by

section 1 of the act was a right of equal treatment under

state laws and proceedings, it was an obvious shorthand

description of the scope of section 3 to say that it covered

“ the cases of persons who are discriminated against by

State laws or customs,” 60 persons “ whose equal civil rights

are denied . . . in the State courts,” 61— and these were the

expressions used by Senator Trumbull, who more than any

other one man was the guiding force behind the Civil Rights

59 Except for the words which now appear as the last clause of

28 U. S. C. §1443(2) (1958), allowing removal of actions or prose

cutions “for refusing to do any act on the ground that it would be

inconsistent with [federal] . . . law [providing for equal civil

rights].”

The language “or for refusing to do any act on the ground that

it would be inconsistent with this act” was added to the Senate bill

by a House amendment. Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., 1366

(March 13, 1866) ; see id., at 1413 (March 15, 1866). Compare id.

at 211 (Jan. 12, 1866) (original Senate bill). The purpose of the

amendment was stated by Representative Wilson, House Judiciary

Committee chairman and floor manager of the bill, in reporting it

from his committee, as follows:

Mr. Wilson, of Iowa.

I will state that this amendment is intended to enable State

officers, who shall refuse to enforce State laws discriminating

in reference to these rights on account of race or color, to re

move their cases to the United States courts when prosecuted

for refusing to enforce those laws . . .

Id. at 1367 (March 13, 1866). There was no other pertinent discus

sion of the provision.

60Id. at 475 (Jan. 29, 1866) (remarks of Senator Trumbull).

61 Ibid.

Act,62 and who gave the only systematic exposition of its

judiciary provisions found in the debates.63 In the con-

62 Senator Trumbull, who was Chairman of the Judiciary Com

mittee, introduced the bill (S. 61), and had it referred to his com

mittee. Id. at 129 (Jan. 5, 1866). He reported the bill from com

mittee, id. at 184 (Jan. 11, 1866), and managed it on the Senate

floor, see id. at 474 (Jan. 29, 1866). Throughout the debates he

played a leading role, fully commensurate with his moral and

political ascendancy over the Thirty-Ninth Congress.

63 See Senator Trumbull’s key speech urging the bill’s passage

over veto, Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 1759 (April 4, 1866):

The President objects to the third section of the bill . . .

[H]e insists [that it] gives jurisdiction to all eases affecting

persons discriminated against, as provided in the first and

second sections of the bill; and by a strained construction the

President seeks to divest State courts, not only of jurisdiction

of the particular case where a party is discriminated against,

but of all cases affecting him or which might affect him. This

is not the meaning of the section. I have already shown, in

commenting on the second section of the bill, that no person

is liable to its penalties except the one who does an act which

is made penal; that is, deprives another of some right that he

is entitled to, or subjects him to some punishment that he

ought not to bear.

So in reference to this third section, the jurisdiction is given

to the Federal courts of a case affecting the person that is dis

criminated against. Now, he is not necessarily discriminated

against, because there may be a custom in the community dis

criminating against him, nor because a legislature may have

passed a statute discriminating against him; that statute is

of no validity if it comes in conflict with a statute of the

United States; and it is not to be presumed that any judge of

a State court would hold that a statute of a State discrimi

nating against a person on account of color was valid when

there was a statute of the United States with which it was in

direct conflict, and the case would not therefore rise in which

a party was discriminated against until it was tested, and

then if the discrimination was held valid he would have a right

to remove it to a Federal court— or, if undertaking to enforce

his right in a State court he was denied that right, then he

could go into the Federal court; but it by no means follows

that every person would have a right in the first instance to

go to the Federal court because there was on the statute-book

25

text of Congress’ concern with, the substantive question of

denials of equality, this language plainly does not mean

that the removal jurisdiction depended upon a showing of

actual denial or discrimination by the state courts: the

very text of the statute reaches prosecutions both against

persons “ who are denied” and those who “ cannot enforce”

their rights in the state tribunals. In any event, it is plain

that Trumbull was summarizing only part of the jurisdic

tion granted by section 3: the jurisdiction under the clauses

affecting persons “ who are denied or cannot enforce” their

federal claims (now 28 U. S. C. §1443(1) (1958) ).64 The

jurisdiction over persons acting “ by virtue or under color

of authority” of the 1866 Act or the Freedman’s Bureau

Acts (now 28 U. S. C. §1443(2) (1958)), remains unillumi

nated.