Pegues v. Mississippi State Employment Service Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

July 21, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Pegues v. Mississippi State Employment Service Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1981. ecb682fb-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f75ce94f-d4c2-4bee-904a-bfb805f04214/pegues-v-mississippi-state-employment-service-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

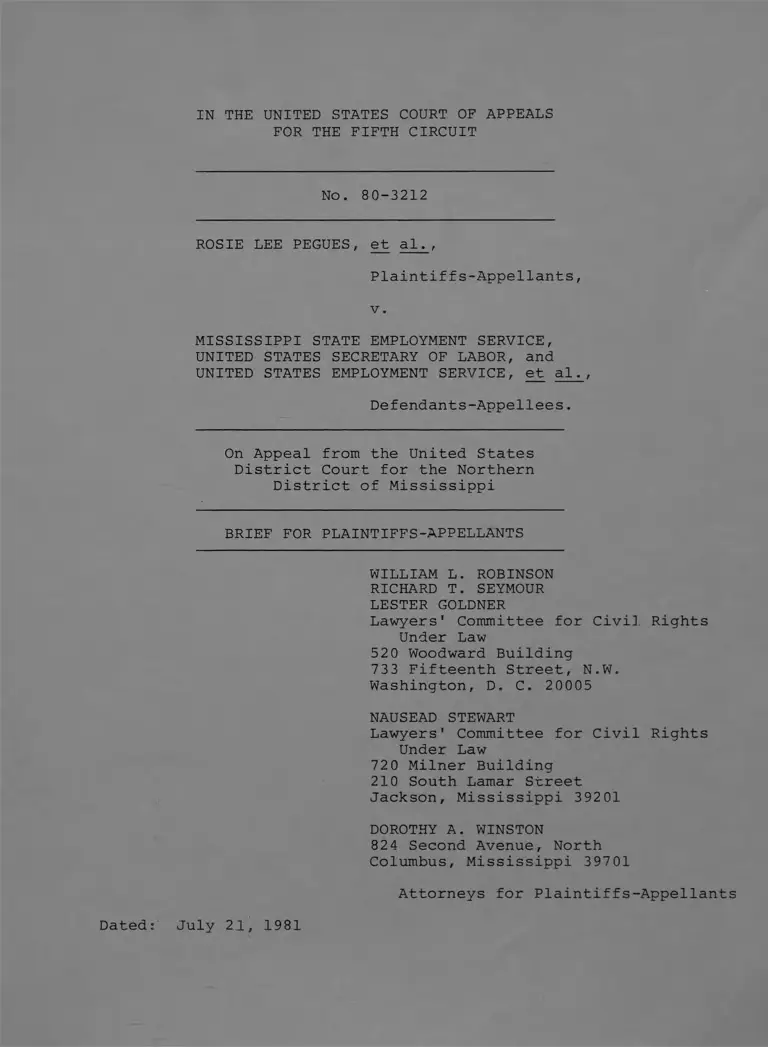

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 80-3212

ROSIE LEE PEGUES, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

MISSISSIPPI STATE EMPLOYMENT SERVICE,

UNITED STATES SECRETARY OF LABOR, and

UNITED STATES EMPLOYMENT SERVICE, et al■,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States

District Court for the Northern

District of Mississippi

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

RICHARD T. SEYMOUR

LESTER GOLDNER

Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights

Under Law

520 Woodward Building

733 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20005

NAUSEAD STEWART

Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights

Under Law

720 Milner Building

210 South Lamar Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

DOROTHY A. WINSTON

824 Second Avenue, North

Columbus, Mississippi 39701

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Dated: July 2.1, 1981

Pegues v. Mississippi State Employment Service, No. 80-3212:

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

The undersigned, counsel of record, certifies that the fol

lowing listed persons and agencies have an interest in the outcome

of this case. These representations are made in order that the Judges

of this Court may evaluate possible disqualification or recusal.

Plaintiffs: and Plaintiffs-Intervenors:

Rosie Lee Pegues

Rebecca Gillespie

Mary Boyd

Robert Williams

Percy Bell

Sletta D. Brown

Mary Hervey

Christine Hodges

Phillip Milan

Pauline Willis

Minority Peoples Council on the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway

Defendants:

Mississippi State Employment Service of the Mississippi Employment

Security Commission

Ernest Lindsey

John Aldridge

United States Secretary of Labor

United States Employment Service

Class Members:

All black, and all female, past, oresent, and future applicants for

employment referrals through the Bolivar County branch office of

MSES (certified class)

All black, and all female, past, present, and future applicants for

employment referrals through MSES (proposed Statewide class for

injunctive purposes only)

RICHARD T. SEYMOUR

Attorney of Record for Plaintiffs-

Appellants

STATEMENT CONCERNING ORAL ARGUMENT

Plaintiffs-appellants request the Court to hold an oral

argument in this case. This appeal comes to the Court after a three-

week trial, in the course of which some hundreds of exhibits were

received and numerous witnesses testified. The opinion below did

not go into the facts in detail, and plaintiffs believe that oral

argument would be of substantial assistance to the Court in coming

to grips with the record. Moreover, the testing issues in this

case are complex, and oral argument may well help clarify them for

the Court,

INDEX

Page

Table of Authorities vi

Statement of Issues 1

Statement of the Case 2

A. Course of Proceedings and Disposition in the Court Below 2

B. Statement of the Facts 5

1. The Parties 5

2. The Importance of the Functions Performed by MSES 6

3. Stipulated Practices of MSES in Classifying and

Referring Applicants 8

4. Evidence of Discrimination in Referrals 9

a) The Acceptance and Servicing of Job Orders

with Stated Sex Preferences 9

b) Racially and Sexually Segregated Referrals

on Job Orders 11

c) Selecting Applicants for Referrals on the

Basis of Unvalidated Educational Requirements 15

d) Selecting Applicants for Referrals on the

Basis of Unvalidated Experience Requirements 18

e) Comparison of Classifications and Referrals

in 1970 19

f) Sharp Increases in the Rates of Black Referrals

After the Filing of Suit 21

g) Sharp Increases in the Rates of Black Referrals

to Material Handler Jobs, After the Cessation

of Business with Travenol Laboratories Made it

a Lower-Paid Job Area 23

h) Racial and Sexual Differences in the Rates of

Pay for Jobs to Which Referrals Were Given,

1970-1978 24

i) Racial and Sexual Differences in Rates of

Referrals 27

j) Referrals Out-of Code 27

-i-

k) Other Classwide Evidence of Discrimination

in Referrals 28

1) Dr. Malone's Analysis 30

m) The Defense that Job Openings Were Scarce 34

5. Evidence of Discrimination in the Classification

of Applicants 35

a) The Relationship Between Classification

and Referral 35

b) The Process by Which Occupational Codes

Are Assigned 36

c) Classifications and Referrals in Service

and Farmwork Occupations 40

d) Sharp Increases in the Numbers of Black

Women Assigned to Clerical and Sales Codes

After the Filing of Suit 43

e) Racial and Sexual Differences in the Class

ification of Female Applicants with a Seventh-

Grade or Lower Level of Education, 1974 44

f) Other Evidence of Discrimination in Class

ification 44

6. Discrimination in Testing 47

a) Evidence of Disproportionately Adverse Impact

of the Challenged Tests on Blacks 48

b) Evidence as to Validation 53

1) Evidence Other Than Dr. Hunter's

Testimony 53

2) Dr. Hunter's Testimony 58

7. The Named Plaintiffs and Class Member Witnesses 63

8. Evidence on Class Determination 65

Summary of Argument 66

Argument 67

A. Plaintiffs Established a Prima Facie Case of Discrimination

Which Has Not Been Rebutted 67

-11-

72

B. Plaintiffs Have Shown That the Challenged Tests Had a

Racially Disparate Inpact and the Defendants Have Not

Shown That They Were Valid

C. The District Erred in Granting Summary Judgement for the

Federal Defendants 75

D. The District Court Erred in Failing to Certify a State

wide Class 77

Conclusion 78

-in-

8

12

13

21

22

23

23

24

25

26

26

33

32

34

LIST OF TABLES

Percentage of Non-agriculture Referrals Resulting

in Hire, as Shown on the State Defendants' Self-

Appraisal Forms

Referrals to Travenol on Material Handler and

Assembles Job Orders (Plaintiffs' Exhibit 1,

Volume III)

Standard-Deviation Analysis of Referrals of

Women on Material Handler and Assembler Job

Orders frcm December 1969 through May 1970

(Travenol laboratories)

Rates of Classification and of Referral,

by Race and Sex in 1970

Standard Deviation Analysis of Rates of

Classification and of Referral in 1970

Proportions of Referrals Given to Blacks,

1970-1973

Proportions of Male Referrals to Structural

Work Jobs Other than Construction labor, and

to Construction labor Jobs, Given to Blacks,

1970-1973

Proportions of Referrals to Material Handler

Jobs Given to Blacks, 1970-1973

Average Hourly Pay Rates Per Referral Given,

1970-1973

Average Hourly Pay Rates Broken Down by

Applicants' Level of Education, per Referral

Given, 1975-1976

Average Hourly Pay Rates, Broken Down by Status

as Veteran or Nonveteran, per Male Referral

Given, 1975-1976

Percent of Job Orders Falling Within Dr. Malone's

Group 2 or Group 3 (Questionable Probability or

High Probability That More Referrals to the Job

Order in Question Should Have Been Given)

No. of Job Orders Closed. Without Referrals, or

Closed With One Referral

Numbers of Referrals Made on Job Orders, 1970-1972

-IV-

41

Table 15 Referrals of Black Women to Service Occupations,

1970-1973 41

Table 16 Results of Efforts to Upgrade the Codes of Male

Applicants With an 8th-Grade or Better Level of

Education, Classified in Service or Farmwork

Codes, 1970-1976 43

Table 17 Increases in the Numbers of Black Women Assigned

to Clerical and Sales Codes, FY 1972 to FY 1974 43

Table 18 Standard-Deviation Analysis of the Referrals to

the Nurse's Aide Training Program at East Bolivar

County Hospital 48

Table 19 Test Results fot the Licensed Practical Nurse

SATB Reported on Application Forms 51

Table 20 Standard-Deviation Analysis of the Test Results

for the Licensed Pratical Nurse SATB Reported on

Application Forms 52

-v-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

A. Cases

Pages

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975) 74,75

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp.,

495 F.2d. 437 (5th Cir.), cert. den.

419 U.S. 1033 (1974) 71

Boston Chapter NAACP v. Beecher,

504 F.2d 1017 (1st Cir., 1974), cert,

den., 421 U.S. 910 (1975) 74-75

Burns v. Thiokol Chemical Corp.,

483 F .2d. 300 (5th Cir., 1973) 74

Corley v. Jackson Police Dept.,

566 F .2d. 994 (5th Cir., 1978) 68

Davis v. Califano,

613 F .2d. 957 (D.C. Cir., 1979) 69

Diaz v. Pan American World Airways,

442 F.2d. 385 (5th Cir.,), cert, den.,

404 U.S. 950 (1971) 69

Dothard v. Rawlinson,

433 U.S. 321 (1977) 69,72

EEOC v. United Virginia Bank,

615 F-2d 147 (4th Cir., 1980) 68

Ensley Branch of NAACP v. Seibels,

616 F.2d. 812 (5th Cir.), cert, den.,

66 L.Ed.2d 603 (1980) 73,75

Falcon v. General Telephone Co. of the Southwest,

626 F.2d. 369 (5th Cir., 1980), vacated

and remanded on other issue, 49 U.S. Law

Week 3743 (1981), opinion reinstated in

relevant part, 647 F.2d. 663 (5th Cir.,

1981) 69

Geller v. Markham,

635 F .2d. 1027 (2nd Cir., 1980) 73

Grant v. Bethlehem Steel Corp.,

635 F.2d 1007 (2nd Cir., 1980), cert, den.,

49 U.S. Law Week 3926 (1981) 69

- vx-

Pages

Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971) 70

Hameed v. Int'l Ass'n of Bridge Workers,

637 F .2d 506 (8th Cir., 1980) 68

Interstate Circuit v. United States,

306 U.S. 208 (1939) 73

Int'l Bhd. of Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 (1977) 68,71,72

James v. Stockham Valves & Fittings Co.,

559 F.2d. 310 (5th Cir., 1977) , eert.

den., 434 U.S. 1034 (1978) 69,71,72,75

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.,

491 F .2d. 1364 (5th Cir., 1974) 70

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 (1973) 71

Parson v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp.,

575 F.2d. 1374 (5th Cir., 1978), cert.

den., 441 U.S. 968 (1979) 70,71

Payne v. Travenol Laboratories,

565 F.2d. 895 (5th Cir.), cert. den..

439 U.S. 835 (1978) 77

Phillips v. Joint Legislative Committee,

637 F.2d. 1014 (5th Cir., 1981) 69

Rogers v. Int'l Paper Co.,

510 F.2d. 1340 (8th Cir.), vacated

on other grounds, 423 U.S. 809 (1975),

modified in other respects, 526 F.2d.

722 (8th Cir., 1975) 74,75

Rowe v. General Motors Corp.,

457 F .2d. 348 (5th Cir., 1972) 68,75

Shelak v. White Motor Co.,

581 F .2d. 1155 (5th Cir., 1978) 73,74

Sledge v. J.P. Stevens & Co.,

585 F .2d 625 (4th Cir., 1978), cert.

den., 440 U.S. 981 (1979) 70,72

Swint v. Pullman-Standard,

539 F .2d. 77 (5th Cir., 1976) 69

Pages

Texas Dept, of Community Affairs v. Burdine,

U.S. , 67 L .Ed.2d 207 (1981) 71

United States v. City of Chicago,

59-9 F.3d. 415 (7th Cir.), cert, den.,

434 U.S. 875 (1977) 74,75

United States v. County of Fairfax,

629 F .2d. 932 (4th Cir., 1980) 69

United States v. Georgia Power Co.,

474 F .2d. 906 (5th Cir., 1973) 70,74

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co.,

451 F .2d. 418 (5th Cir., 1971), cert,

den., 406 U.S. 906 (1972) 74

Vulcan Society of N.Y.C. Fire Dept. v. Civil

490 F .2d. 387 (2nd Cir., 1973)

Service Comm’n,

72

Vuyanioh v. Republic Nat'l Bank of Dallas,

505 F. Supp. 224 (N.D. Tex., 1980) 68,72

Ward v. Apprice,

6 Mod. 265 (Q.B., 1705) 73

Weeks v. Southern Bell Telephone & Telegraph

408 F.2d. 228 (5th Cir., 1969)

Co.,

69

B. Constitution. Statutes, Regulations and Rules

Constitution, Fifth Amendment 4

Constitution, Thirteenth Amendment 4

Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment 4

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972,

Pub.L. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103 4,75,76,77

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq. passim

§701 (c) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

78 Stat. 253-54 75,76

42 U.S.C. §1981 4

42 U.S.C. §1983 4

EEOC Guidelines,

29 C.F.R. §§ 1607.1 et seq. (1972),

reprinted in relevant part at 2a 75

-viii-

Pages

Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures,

29 C.F.R. §§ 1607.1 et seq. (1980)

reprinted in relevant part at

Rule 52(a), F.R.Civ.P.

C. Other Authorities

American Psychological Association,

Standards for Educational & Psychological

Tests (1971+)

2 Conrad, Modern Trial Evidence

§960 (1956)

Senate Subcommittee on Labor of the Committee on Labor and

Public Welfare, "Proposed Equal Employment

Opportunities Enforcement Act of 1971, S.2515,

S.2617, and H.R.17M-6, Bill Texts, Section by

Section Analyses, Changes in Existing Law,

Comparison of Bills Introduced" (1971) (Reprinted

in Legislative History of the Equal Employment

Opportunity Act of 1972 (1972))

2 Wigmore, A Treatise on the Anglo-American System of Evidence

§291 (3rd ed., 191+0)

67 ,73,7i+,75

68

57,74

73

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 80-3212

ROSIE LEE PEGUES, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

MISSISSIPPI STATE EMPLOYMENT SERVICE,

UNITED STATES SECRETARY OF LABOR, and

UNITED STATES EMPLOYMENT SERVICE, et al.

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States

District Court for the Northern

District of Mississippi

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF ISSUES

1. Did the district court err in finding that the State and the Federal

defendants had not discriminated against black, and against female, applicants

for employment referrals at the Bolivar County branch office of the Mississippi

State Employment Service ("MSES") and at other branch offices across the State?

2. Did the district court err in allowing the Federal defendants to

present surprise expert testimony on test validation at the trial, where the

expert propounded novel theories on which the Court relied, and where the

effect of this surprise manuever was to deprive plaintiffs of any effective

opportunity either to discover any problems which may have existed in the

research on which he based his theories, or to prepare for effective cross-

examination?

3. Did the district court err in holding that the 1972 amendments to

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964- withdrew that Act's coverage of the

United States Employment Service?

<4. Did the district court err (a) in denying the applications of a

number of blacks, harmed by the identical practices of MSES in other counties,

to intervene as plaintiffs in this case, and (b) in denying plaintiffs' motion

to certify a Statewide class for the purposes of injunctive relief?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Course of Proceedings and Disposition in the Court Below

The plaintiffs filed their original EEOC charges in March 1970, and

timely filed the Complaint after receipt of Notices of Right to Sue. They

filed supplemental charges in 1973 and 1974, and timely moved to amend the

Complaint after receipt of additional Notices. The motions were granted.

1/

(Stipulation, 59 2-5; stipulation exhibits 2-6, 10-13, 16-19, 21-24; R. 1,

2/

862, 866, 1497, 1609.

The original and amended Complaints in this action alleged across-the-

board classwide discrimination against blacks and against women who applied to

MSES for referrals to employers with available job vacancies. (R. 4-6, 129-33)

The original Complaint alleged a countywide class, and the Amended Complaint

1/ The stipulation and the stipulation exhibits were received in

evidence at trial. (Tr. 45.) All "Tr." references are to the trial transcript.

2/ The original and Amended Complaints alleged both racial discrimina

tion against blacks and sexual discrimination against women. (R. 4-6, 129-33.)

One of the original plaintiffs, Willie Mae Payne, had alleged both race and

sex discrimination in her 1970 EEOC charge. (R. 154). On January 10, 1974---

while the Order has a typed 1973 date, this is clearly In error--she was

dropped as a named plaintiff. (R. 544) . The EEOC charges filed in January

and March, 1974, by plaintiffs Pegues, Gillespie and Boyd alleged both race

and sex discrimination. (Stipulation, 99 2-5; stipulation exhibits 4, 12

and 23) .

-2-

alleged a Statewide class. (R. 3, 128) . On April 3, 1974-, plaintiffs moved to

certify such a Statewide class. (R. 633). On November 16, 1977, six unsuccess

ful black applicants for employment referrals at the Aberdeen, Amory, Green

ville, Picayune, Tupelo, and West Point offices of MSES, as well as the

Minority Peoples Council on the Tenessee-Tombigbee Waterway, applied for

leave to intervene as plaintiffs and additional class representatives, to

strengthen class representation and to support certification of a Statewide

class. (R. 1561-63). On February 6, 1978, the named plaintiffs modified their

197M- motion to seek certification of a Statewide class solely for purposes of

obtaining a declaration on liability and for injunctive relief. (R. 1671).

At a hearing held on February 27, 1978, the district court announced

that it would not certify a Statewide class, but would grant Statewide

injunctive relief if plaintiffs proved Statewide discrimination, arising from

practices similar to those followed in the Bolivar County office. (February

27, 1978 Hearing Tr. 253-56, App. 93-96). The orders denying the applications

for leave to intervene, and certifying a countywide class of blacks and of

women seeking employment referrals at the Bolivar County branch office of MSES,

were entered on March 8, 1979. (R. 1782A, App. 59; R. 1788, App. 61).

The defendants are described in Stipulation 6-21, and the claims

against them were set forth in the Amended Complaint (R. 125). Mr. Lindsey has

been Manager of the Bolivar County branch office of MSES since November 1968,

and Mr. Aldridge was Executive Director of the Mississippi Employment Security

Commission, which operates MSES, from July 1960 until February 1978. The State

defendants have asserted a cross-claim against the Secretary, alleging that any

liability on their part was "was the result of policies the U.S. Secretary of

3/ The Minority Peoples Council alleged that it had 800 members in

Mississippi alone, and that some of its members had claims against MSES.

-3-

Labor has required. MSES to follow." (R. 610; R. 2035, App. 70) .

On March 28, 1978, the district court entered summary judgment on all

claims raised by plaintiffs against the Federal defendants, holding that the

1972 amendments to Title VII withdrew the United States Employment Service

from the reach of Title VII, that the United States was immune from suit under

42 U.S.C. §1981 and the Thirteenth Amendment, and that the pleadings and the

record did not show intentional conduct in violation of the Fifth Amendment.

The State defendants' cross-claim against the Secretary was allowed to stand.

(R. 1791, App. 63) .

On December 27, 1978, the district court entered the agreed Pretrial

Order, to which witness lists were then attached. Paragraph 18 of the Order

recited that it would control the course of trial, and that "it may not be

amended except by consent of the parties and the Court, or by order of the

Court to prevent manifest injustice." (R. 2034B, 204-2, App. 69, 77).

Six days before the start of trial, the Federal defendants notified

plaintiffs of their intention to call an expert witness, John Hunter, Ph.D., to

testify on the test validation issues. (R. 2076). These issues had been

present in this case since the filing of the original Complaint. (R. 5).

Plaintiffs took a hurried deposition of Dr. Hunter on July 5 and 6, 1979. The

Federal defendants moved on the first day of trial for leave to call Dr. Hunter,

i+/ The original Complaint alleged violations of Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq.,_and of 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and

1983 (R 2). The Amended Complaint alleged violations of these provisions,

and 'also alleged violations of the Fifth, Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments.

(R. 134, 137). Allegations of claims arising under other provisions have been

dismissed, (R. 1240; R. 1791, App. 63), and are not involved on this appeal.

5/ Fourteen months before the entry of this ruling, plaintiffs had^

filed their Second Motion to Compel Discovery, seeking to obtain information

bearing on this question (R. 1287). The district court denied the discovery

motion a month before it entered summary judgment against plaintiffs because

of their failure to produce such information. (R. 1790, App. 62) .

4/

-4-

(R. 2075), and plaintiffs opposed the motion on the grounds that Dr. Hunter

was being called to support a novel approach to test validation which was radi

cally different from the work previously done in the field, that he was going to

rely on 26 articles which he had published or which were in the process of being

published, that plaintiffs had received only 16 of the 26 articles by the Friday

evening before the start of trial, that the subject matter of Dr. Hunter’s

testimony was very involved, and that it would be extremely difficult for

plaintiffs’ counsel to be able to check his work and to conduct an effective

cross-examination. (Tr. 14— 16). The Court granted the Motion. (Tr. 16-18;

6/

R. 2080, App. 78) .

Trial was held from July 9 through July 26, 1979. The district court

entered its decision on March 10, 1980, finding all issues in favor of the

defendants. (Decision, R. 2110, App. 79) . Judgment was entered against

plaintiffs on their claims against the defendants, and was entered against the

MSES defendants on their third-party claim against the Federal defendants. (R.

2174, App. 137) . Plaintiffs filed their Notice of Appeal on March 14-, 1980.

(R. 2175) .

B. Statement of the Facts

1. The Parties

The four named plaintiffs are black residents of Bolivar County who

attempted to obtain employment through the services of the Bolivar County branch

office of MSES. Three are female, and one is male. They did not seek employ

ment with MSES, but sought referrals to employers with jobs available to be

6/ While plaintiffs were also allowed to call an additional expert, they

did not do so because there was not sufficient time for such an expert to study

Dr. Hunter's research and to prepare meaningful testimony. Thus, the research

predicates of Dr. Hunter's opinion, on which the trial court placed heavy

reliance, were never subjected to any verification.

-5-

filled by hire. (Stipulation, 59 2-5; stipulation exhibits, 1, 7-9, 14—15,

and 20). Their claims are discussed at 63, infra.

2. The Importance of the Functions Performed by MSES

The primary functions of MSES are to help job applicants to find employ

ment, and to help employers with job openings to fill their jobs. (Stipula

tion, 5 22) . One of the ways in which MSES is to serve its primary function

is to inform qualified applicants of job opportunities they had not known

existed, and thus may not have discovered on their own, and by referring them

to such vacancies. (Stipulation, 5 23). Providing information about such

job opportunities can be extremely important to black applicants, who may have

no other practical means of finding out about job vacancies for many local

7/

employers.

By agreement with local employers, MSES sometimes pre-screens all ap

plicants for production jobs and decides which applicants to refer. In such

cases, the employer will not consider any applicant who has not been referred

by MSES. From February 1965 to November 1971, for example, the Baxter

("Travenol") plant in Cleveland refused to consider applicants for its major

entry-level jobs-- Assembler and Material Handler-- unless those applicants

had first been referred by the Cleveland branch office. (Testimony of Olin

Taylor, the former Baxter personnel manager, Tr. 276-78; testimony of Mr.

Lindsey, Tr. 980-81). Mr. Lindsey thought that similar arrangements may have

existed with respect to two other large local manufacturers although he was

somewhat uncertain in his testimony, but he was convinced that MSES pre-screened

7/ Testimony of Rebecca Gillespie, Tr. 65-66; testimony of Mary Boyd,

Tr. 14-0-4-1. Both of these plaintiffs live in Mound Bayou. (Id.) . Mound Bayou

is an all-black city, and most job opportunities are in other parts of the

county. (Testimony of Calvin Jones, Tr. 1894-95, 1910).

-6-

all of the applicants for the Licensed Practical Nurse training program at

East Bolivar County Hospital. (Tr. 993-95) . Where an employer will only con

sider an applicant who has been referred by MSES, a refusal by MSES to refer an

applicant will bar that applicant from consideration for hire.

Referrals by MSES account for a substantial share of the hires by lar

ger local employers. Mr. Lindsey prepared an analysis of hires by the 85 or 90

8/

local employers with ten or more employees. In the time periods covered by

his analysis, the Bolivar County branch office was responsible for filling up to

43.9% of the new hires of these "major market" employers. From January 1969

through December 1970, a period which includes the filing of EEOC charges herein

the Bolivar County branch office placed 1,030 of the 3,356 new hires of these

"major market" employers, or 30,7% of the total. From January 1976 through

August 1978, the Bolivar County branch office placed 732 of the 3,421 new hires

of such employers, or 21.4% of the total. (Calculation of counsel from State

defendants' exhibit 32) .

While giving a referral to an employer with a job vacancy does not

guarantee that the person referred will be hired, the vast majority of persons

referred are in fact hired. This is true for all applicants in general, for

black applicants, and for female applicants. State defendants’ exhibits 44

through 52, and 55, contain monthly year-to-date statistics on nonagricultural

referrals and placements from 1973 through late 1978. They show the following:

8/ Testimony of Mr. Lindsey, Tr. 2226-27. Mr. Lindsey’s analysis did

not include placements with, or new hires of, the several hundred local employ

ers with fewer than ten employees. Tr. 2227-28.

-7-

Table 1. Percentage of Non-agricultural Referrals Resulting in Hire,

as Shown on the State Defendants’ Self-Appraisal Forms_____

Percentage of Non-Agricultural

State Referrals Resulting in Hire

Defendants’ Date of All Black 9/ Female

Exhibit No. Appraisal Form Applicants Applicants Applicants

55 11/9/73 93.1% 93.6% N.A.

94 7/5/74 75.2% 73.7% 70.3%

45 10/10/74 72.9% 70.7% 69.5%

46 6/26/75 71.4% 98.1% 69.8%

48 10/24/75 72.2% 64.7% 70.5%

49 6/8/76 76.2% 71.6% 73.2%

47 10/18/76 73.1% 68.5% 68.1%

50 6/10/77 67.5% 61.2% 77.8%

51 2/23/78 69.1% 63.8% 55.7%

52 8/16/78 67.7% 63.3% 61.8%

Thus, the decision whether or not to give a referral to an applicant

have a substantial effect on that applicant's chances of obtaining employment.

3. Stipulated Practices of MSES in Classifying and Referring

Applicants

The general operations of the Bolivar County branch office of MSES are

set forth in some detail in Stipulation 59 22-61. In summary, applicants for

employment referrals come to the office, are interviewed and occupational codes

are assigned to them. The code is supposed to represent the type of work for

which the applicant is best qualified. The actual practices of MSES in classi

fying applicants are described at 35-47̂ infra.

When a job order is received from an employer, the employer’s job is also

assigned an occupational code. MSES then makes referrals by matching the occu

pational codes of active applications with the occupational codes of active job

orders, and by matching the education, experience, and other requirements set

by the employer with the characteristics of the applicants being considered.

The actual practices of MSES in selecting applicants for referral are discussed

at 9-35, infra.

9/ Data for "Minorities" was used where data for blacks was not stated.

-8-

4-. Evidence of Discrimination in Referrals

a) The Acceptance and Servicing of Job Orders with

Stated Sex Preferences

Plaintiffs' exhibit 57 is a list of job orders, accepted and serviced

by the Bolivar County branch office of MSES from November 1969 through June

1973, which contained specifications that only men, or only women, be referred

on the job order. (Testimony of Linda Thome, Tr. 635-39) . The exhibit shows

that MSES honored the employers’ sexual preferences, referring only males on

job orders specifying an employer preference for males, and referring only

females on job orders specifying an employer preference for females.

The U.S. Department of Labor had cautioned all State Employment Services

in 1965, 1966, 1967, and 1970 that accepting and servicing such sex specifica

tions on job orders was unlawful under Title VII except where sex Is ”a bona

fide occupational qualification reasonably necessary to the normal operation

of that particular business or enterprise." (Stipulation 5 74, stipulation

exhibits 51, 52; Federal defendants’ exhibits 11, 17; State defendants’ exhibits

23, 26 (both documents)) . Stipulation exhibit 52 expressly cautioned State

Employment Services that they will "share responsibility with the employer" if

they service such sex preferences without evidence that they are a BFOQ, and

caution that a written record must be kept whenever a sex specification is

accepted as a BFOQ. On June 29, 1968, the U.S. Department of Labor wrote to

the defendant Aldridge, informing him that a review of the Cleveland (Bolivar

County) and other branch offices of MSES had shown that all of the offices in

vestigated were accepting and servicing discriminatory sex specifications on

job orders. (Plaintiffs’ exhibit 114, p. 10, part VI). In his August 19, 1968

response, Mr. Aldridge did not quarrel with the Department’s findings as to the

Cleveland office, and promised to institute a compliance review process.

-9-

(Plaintiffs’ exhibit 158 at p. 5). The problem was again brought to Mr.

Aldridge’s attention in an interoffice memorandum dated May 5, 1969. (Plain

tiffs’ exhibit 115, p. 3). Nevertheless, plaintiffs' exhibit 57 showed that

the problem continued in the Cleveland office for more than four years after

the date of this memorandum.

When questioned about this practice, Mr. Aldridge stated that he thought

"the sex part of the Act came along a little bit later", that "the Department

of Labor and the others were not quite as quick to tackle it", and that the

question was in "a transitory period for a while as to just what to do ... .’’

"And in the South we, some people just didn’t think that a woman ought to be in

certain things." Tr. 1226. Although plaintiffs' exhibit 114- had put Mr.

Aldridge on notice that the Cleveland office had engaged in this discriminatory

practice and that it should not be continued, Tr. 1227-28, he stated that he

"had no reason" to inquire thereafter whether the Cleveland office had stopped

the practice, and was not aware that it had continued until 1973. (Tr. 1229-30).

Mr. Lindsey also testified that he thought that "they didn’t start at the same

time. I think the sex came along later.” (Tr. 956-57). He testified that he

was unsure whether he had known in 1969 that the prohibition of sex discrimina

tion was in effect, but he thought he did. (Tr. 961). He had no personal

knowledge of the job orders listed on plaintiffs’ exhibit 57, and could not say

whether there was any investigation into the question whether those sex pre

ferences were justified as BFOQ’s; if there had been such an investigation and

it was not recorded on the job order, he knew of no place where it could have

been recorded. (Tr. 959-60). A Bulletin sent to MSES local office managers on

September 8, 1969, required any such investigations to be recorded on the job

order. (State defendants' exhibit 25, first document p. 2). The bulk of the

job orders in question were included in plaintiffs’ exhibits 1, 2, and 3, and

-10-

none of them show any sign of such an investigation.

Louis Beverly, Jr., the Equal Employment Opportunity officer for MSES

(Tr. 2239), agreed on cross-examination that State Defendants' exhibits 23 and

26 should have alerted the staff of the Cleveland office in 1966 and 1967 that

it was unlawful to engage in such practices. (R. 2289-91).

At trial, Mr. Lindsey was asked whether his office now accepted the

types of job orders shown on plaintiffs’ exhibit 57. He answered: "We do not.

I think our improvement, if that is what you want to call it, has gotten to

the point that we do not." (Tr. 963).

The trial court’s decision did not mention the evidence as to this prac

tice, but stated only that ”[l]ocal offices are prohibited from processing job

orders that contain unlawful sex specifications." (R. 2142, App. 108).

b) Racially and Sexually Segregated Referrals on Job Orders

Mr. Lindsey testified at trial that Travenol Laboratories required

applicants to its Cleveland plant to be referred by MSES before they would be

considered by the company, that this continued from at least 1965 through

November 1971, that he had never seen any sex specification on the master job

order forms for the Assembler and Material Handler jobs, and that he did not

remember any instructions from Travenol’s Personnel Manager as to the sex of

the referrals to be made on these two different jobs. (Tr. 980-85) . Travenol’s

former Personnel Manager, Mr. Taylor, also testified that he did not recall

authorizing MSES to refer only males on the Material Handler job orders and

10/ There can be no contention that the defendants were surprised by the

listing of job orders on plaintiffs’ exhibit 57, or that they had not had suf

ficient time to inquire into those job orders. Pursuant to the pretrial pro

cedure followed in the trial court, the parties exchanged exhibits prior to the

Pretrial Conference in October 1978 (see R. 2034B, 2038-40, App. 69, 73-75),

and Mr. Lindsey and Mr. Aldridge had thus had copies of this exhibit nine months

before the start of trial. (Plaintiffs’ exhibits 1 through 117 were included in

this exchange).

10/

-11-

11/

only females on the Assembler job orders. (Tr. 280, 285-86).

Plaintiffs' exhibit 1, volume III, shows referrals to Travenol on

Material Handler and Assembler job orders. The Material Handler job then paid

$2.21 an hour to start, and the Assembler job then paid $1.97 an hour to start.

(Id., pp. 31, 38) . Disregarding referrals for part-time positions, fid.. p.

46) , referrals marked "FWD" ("foreward") indicating the recordation of hires

of persons previously referred, and using MSES's own counts of referrals when

ever possible (e ,g,, p. 4) , it is clear that MSES referred only males on Materi

al Handler job orders in the six months ending in May 1970, and referred only

females on Assembler job orders in the same period of time:

Table 2. Referrals to Travenol on Material Handler and Assembler

Job Orders (Plaintiffs' Exhibit 1, Volume III)_________

Page No. in Referrals of Referrals of

PX-1, Vol. Ill Date of Job Order Males Females

Material Handlers:

14-15 12/1/69 39 0

16-17 1/2/70 41 0

22-23 2/2/70 21 0

29-30 3/2/70 24 0

-31-32 5/5/70 23 0

33 4/1/70 4 0

34-35 4/21/70 21 0

48 1/20/70 10 0

Total 183 0

Assemblers:

1-2 11/3/69 0 45

3-5 12/1/69 0 42

6-7 12/22/69 0 43

8-9 2/2/70 0 45

10-13 3/2/70 0 63

38-39 4/1/70 0 18

40-43 5/5/70 0 45

Total 0 301

11 / Stipulation exhibits 59 and 60 show that MSES used the occupational

titles "Packager, Solutions and Syringes" and "Table Worker" to describe the

lower-paid Assembler job, and the occupational titles "Material Coordinator”

and "Fork-Lift Truck Operator" to describe the higher-paid Material Handler

job. Mr. Lindsey agreed. (Tr. 986) . The exhibits show that neither of these

job categories required any prior experience, and that on-the-job training

would be provided in each.

-12-

(A table covering referrals for a shorter period of time was introduced as

plaintiffs’ exhibit 156).

37.9% of the 485 referrals were male, and 62.1% were female. Using

these proportions to indicate the availability of applicants of each sex for

these entry-level production jobs, Table 3 shows that it would be extremely

difficult to explain this result by chance:

Table 3. Standard-Deviation Analysis of Referrals of Women on Material

Handler and Assembler Job Orders from December 1969 through

May 1970 (Travenol Laboratories)_____________________________

Material Handler

Job Orders

Assembler

Job Orders

Availability of Women in Total Group

Referred for Both Jobs 62.1% 62.1%

Sample Size (No. of Referrals) 183 301

Expected No. of Female Referrals 114 187

Observed No. of Female Referrals 0 301

Difference - 114 + 114

Standard Deviation 6.6 •

00

No. of Standard Deviations Between Expected

and Observed Nos. of Female Referrals -17.3 +13.6

Mr. Lindsey was shown the job orders in plaintiffs’ exhibit 1, volume

III, and was asked to explain the sexually segregated referrals when the employ

er had not given MSES a sexual preference to follow. He said that he could not

explain it, that he thought there were sexually integrated referrals on later

job orders, and that he did not know what brought about that change. (Tr. 986-

12/

88, 992).

12/ One month after the last of the job orders reflected in Table 2, the

MSES defendants were served with copies of the plaintiffs’ EEOC charges.

(Plaintiffs’ exhibits 97, p. 1, and 101, p. 1). Some of the post-service-of-

charges job orders in plaintiffs’ exhibit 2, volume III, show both males and

females referred for the Assembler job (Id,, pp. 10 (a)-13 (c) , 15(a)-15(f), 17(a)

17 (i)) , although only males were referred on Material Handler job orders.

(Id., pp. 7 (a)-7 (c) , 19). MSES staff at State headquarters were aware of these

patterns of segregated referrals. (Plaintiffs’ exhibit 116).

-13-

A manual analysis of MSES referral records for the Bolivar County branch

office for the period from November 1969 through December 1970, the period in

which the initial EEOC charges in this case were filed, show that there were

185 job orders on which two or more applicants were referred. Of these, 175

job orders__ 94.6% of the total---resulted in either all-male or all-female re

ferrals, and H O -- 59.5% of the total---resulted in either all-white or all

black referrals. (Plaintiffs1 exhibit 58, p. 1; testimony of Linda Thome, Tr.

639-M-l, 681). Mr. Lindsey was asked for an explanation, but said that he

13/

could give no answer. (Tr. 992-93) .

The trial court did not address this evidence in its decision. Instead,

the court found nondiscrimination in reliance on Mr. Lindsey's testimony,

"based on random examination of referrals on job orders", that referrals "were

made without regard to the race or sex of the applicants referred", and on the

basis of its view that MSES performed nondiscriminatorily, within the limita

tions under which it labored. (R. 2123, 2125-26, App. 91-93).

The "random examinations" of job orders mentioned by the court below were

reflected in the "self-appraisal" forms introduced as State defendants' exhibits

14/

44-55. Typically, the self-appraisal forms in evidence recite that a "random

sample" of ten or so job orders was pulled from the file and found to be non-

discriminatory. However, Mr. Lindsey testified that he did not pull any

13/ This was not an isolated phenomenon. Calculations of counsel from

the 1972 job orders in evidence as plaintiffs' exhibit 3 show that there were

427 job orders with two or more referrals. Sex was identified for all refer

rals on 424 job orders. Of these, 402 or 94.8% of the total resulted in

referrals only of males, or only of females. There were 407 job orders with

race identified for all referrals. Of these, 214 job orders 52.6% of the

total resulted in referrals only of whites, or only of minorities.

14/ There was no self-appraisal form for 1970 or for 1971, and the

district court's rationale is therefore inapplicable to the situation at the

time the charges of discrimination were filed, or to the exhibits and testimony

concerning the Travenol job orders.

-14-

"random samples" from the files; he asked the interviewers whose conduct he

was examining to pull a "random sample" of the job orders they had handled.

(Tr. 2233-34-) . He admitted that he gave them no instructions to follow in

picking job orders for his review, because he believed that that would destroy

the randomness of the sample. (Tr. 24-58-59) . He further admitted that the

interviewers pulling out job orders for his review were probably aware that it

was for the purpose of filling out a civil rights self-appraisal form. (Id.)

The lower court sustained an objection to the question whether Mr. Lindsey

actually knew if the job orders he reviewed were being pulled by interviewers

on a random basis (Tr. 24-59) . Counsel for plaintiffs then asked the following

question:

Q. Did you ever take any steps to find out whether

the interviewers in fact had pulled out the best possible

job orders in terms of minority referrals?

The MSES defendants objected on the basis that this constituted "harassment of

the witness." The lower court sustained the objection. (Tr. 24-60).

Subsequently, Mr. Lindsey admitted, as to the format of the self-ap

praisal reports: "It just sort of lends itself to showing a satisfactory

15/

situation, just on the face of it.” (Tr. 24-78) .

c) Selecting Applicants for Referral on the Basis of Unvalidated

Educational Requirements ___________ _______________________

Mr. Lindsey testified that it was the policy of his office to accept

whatever an employer sets down as its educational requirement, and to refer

only applicants meeting the requirement, unless there were too few applicants

15/ Compare, for example, State defendants' exhibit 53, p. 2, the self-

appraisal form dated August 30, 1972, which says "All orders for the six-month

evaluation period were checked and no discriminatory specifications found as

to age and sex", with plaintiffs’ exhibit 57, p. 3.

-15-

with that level of education. If that occurred, his office would then try to

obtain some leeway from the employer with respect to the requirement. He could

not recall any specific instance in which his office had in fact been short of

people with the requisite level of education. (Tr. 976-78) . Lane Hart, the

Director of MSES from November 1957 through August 1, 1975 (plaintiffs'

exhibit 19-9, Dep.Tr. 66; plaintiffs’ exhibit 150, Dep.Tr. 5), and Charles

Ballard, chief of the Programs and Methods Branch of MSES from 1956 through

1976 and thereafter Assistant Director of MSES, (Tr. 2520-21) , testified that

efforts to negotiate an employer's educational requirement downward, or to seek

waivers of the requirement on behalf of particular applicants, were not made

when the local office had enough applicants with the requisite level of educa

tion available for referral. (Plaintiffs’ exhibit 150, Dep.Tr. 24-25). MSES

does not require the local office manager to obtain any facts from the employer

indicating that the educational requirement can be validated. (Id., Dep.Tr. 29).

Plaintiffs' exhibits 5 and 56 show a number of job orders with educa

tional requirements serviced by the Cleveland branch office in 1970 and in 1976.

Many of them are for ordinary clerical positions, or positions as waitress,

cook, sales clerk, and so forth. Mr. Lindsey testified that his office had

accepted basically the same types of educational requirements, and has serviced

them, throughout the period of time he has been Manager of the local office.

(Tr. 974-76).

Census statistics show that educational requirements in Bolivar County

and in the State of Mississippi have a disproportionately adverse effect on

blacks. (Stipulation ?*[ 68, 69; stipulation exhibits 47, 48). Dr. Linda Malone,

a statistician called by the State defendants, testified that black applicants

in the Bolivar County branch office had a lower level of education than white

applicants, that female applicants had a lower level of education than male

-16-

applicants, and that the differences were statistically significant. (Tr. 1429-

36; State defendants' exhibit 71). Plaintiffs' exhibit 8 shows that the propor

tions of blacks among the applicants referred declines sharply as the level of

the educational requirement or preference increases.

16/

There is no evidence of any business necessity for this practice.

Even in the absence of an educational requirement set by an employer,

MSES interviewers may decide to select one applicant for referral, instead of

another, based in part upon the applicant's level of education. (Testimony of

Mr. Lindsey, Tr. 1022-23).

The district court found that acceptance by the MSES defendants of

Travenol Laboratories' tenth-grade requirement discriminated against black appli

cants, but that Travenol's use of MSES had ended in November 1971, prior to the

judicial Complaint, and that plaintiffs and their class were accordingly not

17/

entitled to any relief on this issue. (R. 2168-69, App. 130-31). The court

did not discuss the large number of similar job orders accepted and serviced by

the MSES defendants after the filing of the judicial Complaint, but observed

that regulations prohibited the local office from accepting employer requirements

which result in the exclusion of applicants of a particular race. (R. 2140,

App. 106) .

16/ Mr. Lindsey testified that employers would be generally receptive to

some extent, if he called them and said that he did not have enough applicants

meeting their educational requirements and asked permission to refer persons

with a lesser level of education. He did not know whether employers would be

any less receptive if he informed them that MSES would like to refer applicants

whom MSES thought capable of doing the job, without regard to educational require

ments. (Tr. 978-79). y

17/ Plaintiffs had filed their EEOC charges in March 1970, and the EEOC

had also investigated the matter in 1970. (Plaintiffs' exhibits 96, 97, 101, 103)

-17-

d) Selecting Applicants for Referral on the Basis of Unvalidated

Experience Requirements______________________________________

The evidence at trial established that MSES policies with respect to the

servicing of experience requirements set by employers were identical to its

policies with respect to the servicing of educational requirements set by em

ployers. (Testimony of Mr. Lindsey, Tr. 979-80; testimony of Mr. Ballard,

plaintiffs’ exhibit 150, Dep. Tr. 59-60; Stipulation 5 70); plaintiffs' exhibit

5) .

The evidence at trial showed that there are substantial racial and sex

ual differences in the types of previous employment experience possessed by

applicants. Mr. Lindsey testified that, at least through the mid-1960's, the

traditionally-black jobs in Bolivar County for males were service station

attendant, cook, and general labor. The traditionally-black jobs for females

were maids, cooks, restaurant cooks, char workers in motels, and industrial

maids. The traditionally-white jobs were everything else. (Tr. 822-23). He

further testified that, for the entire period of time covered by State defend

ants' exhibits 49— 55-- the self-appraisal forms from 1972 through 1978-- blacks

in Bolivar County had had less experience and training than whites. (Tr. 2465-

66). Mr. Jones, the Superintendent of the part of the local school district

in Mound Bayou, testified that the background of the black population in Mound

Bayou had essentially been farm labor, that the mechanization of farms had

thrown them out of work, that they did not have the experience or skills for

other work, and that, while some progress had been made, the continuing high

rate of black unemployment indicated that the problem was still present. (Tr.

1894-98, 1908-09, 1918-19). Mr. Beverly testified that he had become familiar

with the fact that a previous-experience requirement for a relatively high-

paying job in the Mississippi Delta could have a disproportionately adverse

-18-

effect on blacks, and that for this reason he had included such situations in

the civil rights training manual for local MSES staff. (Tr. 2281; State de

fendants' exhibit 43 at pp. 44-46). Stipulation 72 and 73, and Stipulation

exhibit 50, show 1970 Census statistics indicating substantial differences be

tween the occupations held by blacks and those held by whites, and between

those held by women and those held by men.

The defendants did not introduce any evidence of business necessity for

this practice. Mr. Lindsey testified that he had no basis for knowing whether

employers would be unreceptive if his office informed them that it would refer

applicants MSES thought could do the job, without regard to prior experience.

(Tr. 980) .

Even where employers have not specified an experience requirement, MSES

relies heavily on the previous employment experience of applicants in deciding

which applicants to refer to the employer. (Testimony of Mr. Lindsey, Tr. 1022;

testimony of George Nash, Tr. 2077) .

The district court did not address this issue in its decision, except by

noting that employment service offices were prohibited from processing facially

neutral orders with racially exclusionary effects. (R. 2140, App. 106).

e) Comparison of Classifications and Referrals in 1970

Under MSES policy, an applicant with an occupational code identical or

similar to the occupational code of a job order should be referred on the job

order before other applicants are referred. (Stipulation, 15 38, 57-59). Mr.

Lindsey testified that there was quite a bit of leeway within each code "family"

or group of jobs with the same initial digit; if a job order had the initial

digit 1', indicating a professional, technical, or managerial job, MSES would

probably refer only persons whose occupational codes also began with "1". Ex

ceptions were sometimes made, but this was the general rule. (Tr. 808-09; sti

-19-

pulation exhibit 36, vol. II, p. 1). The MSES defendants have sought to estab

lish that the classificaticrB of applicants into various occupational codes

reflect the qualifications, abilities, and interests of applicants, (Stipula

tion, 39; testimony of Mr. Lindsey, Tr. 2166-67; decision, R. 2135-39, App.

102-05). Putting aside for the moment plaintiffs’ contention that there has

been discrimination in the discharge of this function, a comparison of the rates

at which blacks have been classified into particular code "families" with the

rates at which blacks have been referred on job orders for the same "families"

should show whether MSES has made racial distinctions in the referrals of

applicants it had previously decided to be similarly qualified.

Plaintiffs’ exhibit 80 shows the classification of applicants in 1970,

and plaintiffs' exhibit 80 shows the classification of applicants in 1970, and

plaintiffs' exhibits 61 and 62 show their referrals in 1970, by occupational

codes. Table M- shows that there are substantial differences between the

classification rates and the referral rates of black applicants to various

code "families". An asterisk indicates that the difference is statistically

significant, as indicated in table 5 on page 22.

-20-

Table 4. Rates of Classification and of Referral, by Race and Sex,

in 1970 __________________________________________

Mean Black Males, as Per- Black Females, as Per-

Hourly centage of All Males centage of All Females

Code Description Wage Coded Referred Coded Referred

0-9 All Jobs — 57.2% 38.0%* 61.0% 48.7%*

0,1 Professional,

Technical &

Mgr. Jobs $1.96 34.1% 7.7%* 38.5% 0%*

2 Clerical and

Sales Jobs $1.95 37.2% 19.8%* 32.5% 18.5%*

3 Service Jobs $0.93 82.9% 77.3% 83.7% 87.0%

1+ Farmwork Jobs $1.37 79.5% 58.6%* 94.1% 100 %

5 Processing

Jobs $1.56 60.0% 42.9% 37.5% —

6 Machine

Trades Jobs $1.72 52.5% 12.5%* 25.0% 100 %

7 Bench Work

Jobs $1.59 38.7% 28.6% 35.1% 66.7%*

8 Structural

Work Jobs $1.77 62.7% 55.1% 33.3% —

9 Miscellaneous

Jobs $1.84 58.6% 65.9% .65.3% 23.6%*

f) Sharp Increases

Filing of Suit

in the Rates of Black Referrals After the

Plaintiffs introduced manual analyses of referrals to various types of

occupations, broken down by race and sex. (Plaintiffs1 exhibits 61, 62, 65,

66, 69, 70, 73, and 74). The proportions of all referrals given to blacks in

creased after service of the EEOC charges in mid-1970, and increased substan

tially again in the year suit was filed; the proportions of referrals to other

traditionally-white jobs went up markedly after suit. Table 6 on p. 23 shows

the details.

-21-

-22

-

Table 5. Standard Deviation Analysis of Rates of Classification

and of Referral in 1970 _______

Males All Codes

Prof., Tech.

& Mgr. Codes

Clerical &

Sales Codes

Farmwork

Codes

Mach. Trades

Codes

Availability: Blacks as Pro

portion of Applicants With

This Code .572 .341 .372 .795 .525

Sample Size: No. of Referrals

to Jobs With This Code 505 13 253 29 8

Expected No. of Black Referrals 288.9 4.4 94.1 23.1 4.2

Observed No. of Black Referrals 192 1 50 17 1

-- Difference -96.9 -3.4 -44.1 -6.1 -3.2

Standard Deviation 11.1 1.7 7.7 2.2 1.4

No. of Std. Dev1ns Between Ex

pected and Observed Values -8.7 -2.0 -5.7 -2.8 -2.3

Females All Codes

Prof., Tech.

& Mgr. Codes

Clerical &

Sales Codes

Bench Work Miscellaneous

Codes Codes

Availability: Blacks as Pro

portion of Applicants With

This Code .61 .385 -325 .351 .653

Sample Size: No. of Referrals

to Jobs With This Code 759 9 124 48 297

Expected No. of Black Referrals M-63.0 3.5 40.3 16.8 193.9

Observed No. of Black Referrals 370 0 23 32 70

--Difference -93.0 -3.5 -17.3 +15.2 -123.9

Standard Deviation 13.4 1.5 5.2 3.3 8.2

No. of Std. Dev’ns Between Ex

pected and Observed Values -6.9 -2.3 -3.3 +4.6 -15.1

Table 6. Proportions of Referrals Given to Blacks, 1970-73

Type of Job

% Black

in 1970

% Black

in 1971

% Black

in 1972

% Black

in 1973

All Jobs

- Males 38.0% 59.2% 67.3% 78.7%

- Females 48.7% 52.7% 68.9% 64.2%

Clerical and

- Males

Sales

19.8% 25.5% 34.3% 52.7%

- Females 18.5% 10.6% 28.8% 44.7%

Professional,

- Males

Technical, Managerial

7.7% 32.3% 28.6% 58.4%

- Females 0% 36.8% 27.8% 67.6%

Plaintiffs’ exhibit 76 shows that the qualifications of many of the whites re

ferred to Professional, Technical and Managerial jobs in 1970 were minimal.

Until suit was filed, black male applicants received a disproportionately small

number of referrals to structural work occupations other than construction

labor (codes 80-85 and 87-89) , and a disproportionately large number of re

ferrals to the lower-paid construction labor occupations (code 86):

Table 7. Proportions of Male Referrals to Structural Work Jobs

Other than Construction Labor, and to Construction

Labor Jobs, Given to Blacks, 1970-1973_______________

Year

Range of Pay Rates_____

Other Than

Construction Construction

Labor Labor __

Male Referrals

To Structural

Jobs Other Than

Construction Labor

-- % Black________

Male Referrals

To Construction

Labor Jobs

--% Black_____

1970 $1,94-$2.50 $1.60

1971 $1.71-$2.35 $1.69

1972 $1.87-$3.28 $1.82

1973 $1.68-$2.43 $1.77

32.6%

50.8%

75.4%

70.4%

87.5%

77.8%

78.9%

76.3%

g) Sharp Increases in the Rates of Black Referrals to Material

Handler Jobs, After the Cessation of Business with Travenol

Laboratories Made it a Lower-Paid Job Area_________________

The Material Handler job at Travenol was much more highly-paid than

other Material Handler jobs in the area which, from an examination of job orders

18/

seem to have involved manual labor loading and unloading trucks. In

18/ See, e,g., plaintiffs’ exhibit 1, vol. II, pp. 260, 264, 266, 268

and 272.

-23-

November 1971, Baxter Laboratories stopped, using MSES as its sole source of

referrals, and the average hourly pay rate on Material Handler job orders

declined accordingly. Plaintiffs' exhibits 61, 62, 65, 66, 69, 70, 73 and 74-

show that, as the average pay rate of the Material Handler job orders declined,

MSES increased substantially the proportions of blacks it referred on such job

orders:

Table 8. Proportions of Referrals to Material Handler Jobs

Given to Blacks, 1 9 7 0 - 1 9 7 3 ____________________

Year

Overall Average

Hourly Pay Rate

Male Referrals

To Material

Handler Jobs

-- % Black

Female Referrals

To Material

Handler Jobs

-- % Black

1970 $1.89 60.4% 23.6%

1971 $2.06 55.3% 56.6%

1972 $1.79 84.5% 100% (only 1 woman)

1973 $1.57 84.1% 86.7%

The district court did not address this evidence in its decision.

h) Racial and Sexual Differences in the Rates of Pay for Jobs

to Which Referrals Were Given, 1970-1978__________________

The U.S. Department of Labor has established a method of analyzing the

activities of local employment service offices from the standpoint of civil

rights compliance. Called "PEER” , it compares the average wage rates of the

jobs to which applicants of each race and sex were referred, and compares the

services provided to them with their representation in the population. Mr.

Beverly testified that it was a very useful approach which might require him to

take much harder looks at some things now than he would have earlier. (State

defendants’ exhibit 80 at pp. 4-5; Tr. 2272-74, 2294— 95, 2312).

From 1970 through July 1978, there were strong racial and sexual dis

parities in the pay rates of jobs to which referrals were given:

-24-

Table 9. Average Hourly Pay Rates Per Referral Given, 1970-1978

White Male Black Male White Female Black Female

Time Period Referrals Referrals Referrals Referrals

1970 $2.05 $1.67 ’$1780 $1.18

1971 1.98 1.78 1.96 1.70

1972 1.87 1.80 1.65 1.10

1973 1.96 1.73 1.70 1.42

1/74 to 6/74 2.26 2.13 1.86 1.58

7/74 to 6/75 2.36 2.19 2.11 2.09

7/75 to 6/76 2.64 2.41 2.32 2.27

10/76 to 9/77 2.80 2.57 2.56 2.40

10/77 to 7/78 3.05 2.77 2.78 2 .62

(Plaintiffs’ <exhibits 117, 119 at p. 7, 123 at p. 1) . Plaintiffs’ exhibit

at p. 1 shows the levels of statistical significance for various comparisons

for the period from 1974 to 1978; most of the differences are significant at

19/

the .0001 level.

Plaintiffs’ exhibit 19(b) is a much more extensive analysis of referrals

by each MSES office in the State for a period of approximately a year ending in

20/

March 1976. Although Dr. Malone had found statistically significant differ

ences between the levels of education of blacks and whites and of males and

females, pp. 369-76 of this exhibit show that any large overall racial or

sexual differences remain even when comparing referrals of persons with the

same levels of education:

19/ Because the statistics for the period 1970-1973 were calculated by

hand rather than by computer, no calculations of significance were done for

this period.

20/ Plaintiffs’ exhibit 19(b) at p. 369 shows that the tape reflects

data for 5,785 separate applicants at the Bolivar County branch office, and

plaintiffs’ exhibit 153 shows that there were 5,566 new or renewed applica

tions filed in FY 1975. The MSES defendants supplied this tape to plaintiffs,

bud did not inform plaintiffs of the data it covered. (Tr. 265-66) . Mr.

Frodyma testified that data on the tape ended in March 1976. (Tr. 263-66).

-25-

Table 10- Average Hourly Pay Rates Broken Down by Applicants'

Level of Education, per Referral Given, 1975-76

Educational

Level of

Applicants

All Applicants

1-6 Years

7-9 Years

10-11 Years

12 Years

13-15 Years

16 or More Yea

White Males

$2.61

2.36

2.30

2.61

2.73

2.70

3 3.02

Black Males

$2.39

2.31

2.37

2.38

2.37

2.53

2.92

White Females

$2.26

2.10

2.12

2.15

2.27

2.31

2.46

Black Females

$2.22

2.15

2.11

2.20

2.21

2.30

2.44

MSES is required to give veterans preference in referrals, 20 C.F.R

§ 653.221(a) (7) (1980), a provision primarily of benefit to men but not chal

lenged in this case. Plaintiffs’ exhibit 19(b) at pp. 377-78 shows that white

men who were not veterans fared substantially better than black men who were

veterans:

Table 11. Average Hourly Pay Rates, Broken Down By Status as

Veteran or Nonveteran, per Male Referral Given, 1975-76

Status White Males Black Males

Hourly

Difference

Annual

Difference

(2080 Hours)

All Applicants $2.61

Veterans 2.72

Non-veterans 2,57

$2.39 22d $457.60

2.42 30d $624.00

2.39 18d $374.40

Mr. Nash was asked whether he could explain these racial disparities

between black males and white males. He stated that he could not. (Tr. 2086-

87). The district court did not address this evidence in its findings, but its

conclusions stated that "the human elements involved in affording a job appli

cant an opportunity of gainful employment ... cannot be inserted into a compu

ter" to show a true picture, and stated that plaintiffs’ charts and schedules

did not reflect "all of the relevant and available information". (R. 2167, App.

130) .

-26-

i) Racial and Sexual Differences in Rates of Referrals

Plaintiffs' exhibit 123 shows that, for the period from 1974 through

1978, whites have received a substantially higher rate of referrals than blacks,

and that the disparity is generally statistically significant.

In addition to comparing rates of referral for applicants generally,

plaintiffs also compared rates of referrals for applicants in "available appli

cant pools", i,e., applicants with the same occupational code as a job order or

the same occupational code as someone actually referred on the job order. These

are the same applicant pools used by the State defendants' expert. (Testimony

of Michael Frodyma, Tr. 243-44). Thus, use of these "available applicant pools"

compares applicants whom MSES has, in its assignment of occupational codes, con

sidered comparably qualified. Plaintiffs' exhibit 123 shows the same pattern of

statistically significant racial disparities in rates of referral for persons in

"available applicant pools" as was shown for the general population.

j) Referrals Out-of-Code

When MSES referred an application to a job category with an occupa

tional code outside the same initial-digit code "family" as the applicant's

occupational code, the referral was to a job for which MSES had not considered

the applicant best suited. Plaintiffs' exhibit 107 shows that 68 applicants

were referred out-of-code to Clerical and Sales jobs in 1970, and that 85.3% of

them were white. Mr. Lindsey testified that he did not know why, when blacks

constituted more than 60% of the applicants in the office, 85.3% of the re

ferrals out-of-code to Clerical and Sales jobs had been received by whites.

(Tr. 1016-17).

Plaintiffs' exhibit 108 shows that 68 applicants were referred out-of-

code to Service jobs in 1970, and that 64.7% of them were black. Fifteen white

women, and 18 black women, were referred to Service jobs despite having been

-27-

classified in Clerical and Sales codes. Plaintiffs' exhibit 109 focuses on the

women referred out-of-code to Service jobs, and shows that only black women

were referred out-of-code to the traditionally-black Domestic, Cook or Kitchen

Helper jobs. Thirteen of the 15 white women--86.7%---with Clerical and Sales

codes were referred to Waitress positions. Of the 18 black women with Clerical

and Sales codes, however, 14--77.8% of the total-- were referred to Domestic

or Cook positions.

Plaintiffs' exhibit 75 shows that there were 113 parsons referred out-of-

code to Domestic positions in 1971, and that 110 of them 97.3% of the total--

were black women. Two of them had been given Clerical and Sales codes.

The district court did not address this evidence in its decision.

k) Other Classwide Evidence of Discrimination in Referrals

"Job development" is "the process of soliciting an employer's order for

a specific applicant for whom the local office has no suitable opening currently

on file." A local Employment Service office is supposed to engage in job

development activities for applicants with unusual skills or training and for

applicants who are hard to place, because few orders are received for the kinds

of work they can do. (Federal defendants' exhibit 51, §§ 1685, 1687). Most of

State defendants’ exhibits 44 through 52 contain racial breakdowns df job

development activity; they show that the proportion of placements resulting

from job development activities undertaken on behalf of black applicants is far

lower than the proportion of applicants who are black. (Plaintiffs' exhibit

170) . Mr. Beverly testified that he would not have looked at these figures as

indicating any cause for concern as late as 1977, but his office had become more

sophisticated with the introduction of the "benchmark" analysis in the USES PEER

program, and he would now look at it "a whole lot different". (Tr. 2294-95) .

Mr. Lindsey testified on direct examination that job developments were

-28-

used for both skilled and unskilled jobs, and that such efforts should be under

taken for applicants "who are hard to place because few orders are received for

the kinds of work they can do", as well as for highly skilled applicants. (Tr.

2445). When confronted with the racial disparities shown on his own self

appraisal forms and reflected in plaintiffs' exhibit 170, he changed his testi

mony and explained them by saying that blacks had less experience and less

training than whites, and job developments were undertaken only for persons with

specific qualifications. He admitted that the decision whether to undertake job

development efforts for a particular applicant was subjective, and that he had

not always made specific inquiries of interviewers to find out whether they

21/

had been discriminating in job developments. (Tr. 2465-67, 2*478) .

In theory, Federal regulations prohibit Employment Service offices from

processing job orders from local employers known to be discriminatory. (Federal

defendants' exhibit 51, § 1294; State defendants’ exhibit 8, § 1294; decision,

R. 2140, App. 106). The district court found that these regulations were "legal

and effective." (R. 2132, App. 98-99). Nevertheless, MSES's own investigation

of the EEOC charges filed by the plaintiffs herein show that no black applicants

referred to Baxter (Travenol Laboratories) would be hired unless they knew, and

were recommended by, three particular black individuals:

This is common knowledge in the community and anyone

with whom you talk is knowledgeable about the procedures

used to get employment at Baxter.

21/ Freddie Funchess, a black applicant, had taken accounting courses

in high school and had finished two years of college in Business Administration.

He had had jobs and training in a wide variety of occupational areas. (Tr.

486-500). Plaintiffs' exhibit 40, p. 1, shows that he visited the Bolivar

County branch office on February 26, 1974, and was not given a referral then or

later. Plaintiffs’ exhibit 4, vol. I, pp. 402-03, shows that a job development

was successfully undertaken on behalf of a white applicant two days later, for

a job as Manager Trainee for the Sonic Drive-In. The job required a high school

degree, and did not require any previous experience. Mr. Lindsey did not know

why a job development contact had not been made for Mr. Funchess. (Tr. 1033-37)

-29-

... Applicants who exceed the norms and are other

wise qualified for work are denied employment at Baxter

simply because they are not known by the three men

mentioned above.

(Plaintiffs’ exhibit 116, p. 2; Tr. 2285-87). Despite this knowledge by MSES

that Baxter imposed a condition on black applicants which it did not impose on

white applicants, MSES continued to service job orders from Baxter.

In its most recent investigation of record into the actions of the

Bolivar County branch office, the Secretary's Office found on June 29, 1968,

that the Cleveland branch office and eight other MSES offices had discriminated

against blacks in making referrals to positions which had traditionally been

closed to blacks:

Each of these studies revealed patterns of white

applicants being referred to public contact posi

tions, in many cases with no related codes or

experiences, over better qualified Negroes who

were available for referral during the time that

the orders were being serviced.

(Plaintiffs’ exhibit llM- at p. 7) . The Department of Labor also found that the

Bolivar County branch office of MSES had discriminated against blacks in refer

ring applicants to summer employment positions at Baxter Laboratories. (Id.

at p. 8). In his response, the defendant Aldridge did not dispute the general

finding of discrimination in referrals but stated that the situation was

improving. (Plaintiffs' exhibit 158 at p. 3).

The district court did not address any of this evidence in its decision.

1).Dr. Malone’s Analysis

Dr. Linda Malone, the State defendants’ statistician, testified that her

analysis of referrals by the Bolivar County branch office for the period from

1974 through 1978 showed no discrimination. Her analysis was on a job-order-

by-job-order basis; for each, she did separate analyses for each race, each sex,

and each race/sex group. In each analysis, she examined each job order to

-30-

determine whether she would place it in Group 1, meaning that there is a low

probability of doing better for the group in question, in Group 2, meaning that

there is some chance of discrimination against the group in question but that it

is unclear, or in Group 3, meaning that there is a high probability that more

referrals should have been given to the group in question. In performing her

analysis for each job order, she used "available applicant pools”, defined as

described at 27, supra. For each of the groups she studied, and for each time

period, she found that her analysis placed most jobs in Group 1 and only a very

small number of jobs in Group 3. She accordingly concluded that there was no

discrimination. (Testimony of Dr. Malone, Tr. 1390-99, 14-36-39; State defend-

22/

ants’ exhibits 63-68) .

An unusual feature of Dr. Malone’s approach is that some job orders wind

up in Group 1 for all of the groups being examined. (Tr. 14-96) . However, if

all of the job orders falling within Groups 2 or 3-- i.e., those with a

questionable probability or high probability that more of the group in question

should have been referred-- it is apparent that even Dr. Malone's analyses show

strong racial and sexual differences. For example, in the period of time from

October 1977 through July 1978 for long-term jobs, there was a possible ques

tion of discrimination against white males with respect to only 6.1% of job

orders; for black males, there was such a question with respect to 10.4-% of

22/ Dr. Malone’s analysis resulted in comparing a group plaintiffs con

tended to be discriminated against with another group containing persons who

were also contended to be victims of discrimination. Thus, in assessing whether

there was discrimination against black males, she did not compare their refer

rals with those given to white males; she compared black male referrals with

the combined referrals of a group consisting of black women, white women, and

white males. She never compared the actions of MSES as between black females

and either white males or white females; she compared the referrals given to

black females with the combined referrals given to a group consisting of black

males, white males, and white females. (Tr. 1393-94-, 14-88-90). Of necessity,

such an approach would tend to conceal whatever racial or sexual disparities

in referrals may exist.

-31-

job orders; for black females, 27.8%; for all blacks, 24.8%; and for all women,

23.0%. Table 12 on the next page provides the details.

The essence of Dr. Malone’s analysis is that she looked at each job

order separately. She admitted that her analysis would not detect discrimina

tion if an "available applicant pool" was 50% black, and if MSES processed a

hundred job orders for that pool, each time referring one white male for a

total of 100 white males and no others referred. (Tr. 1524-25). If only one

applicant were referred on a job order, that order would of necessity have been