Hopwood v. Texas Brief for Proposed Intervenors-Appellants

Public Court Documents

March 17, 1994

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hopwood v. Texas Brief for Proposed Intervenors-Appellants, 1994. 9a2f8e61-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f768027b-ddb6-4287-a9bd-073ce8e1daec/hopwood-v-texas-brief-for-proposed-intervenors-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

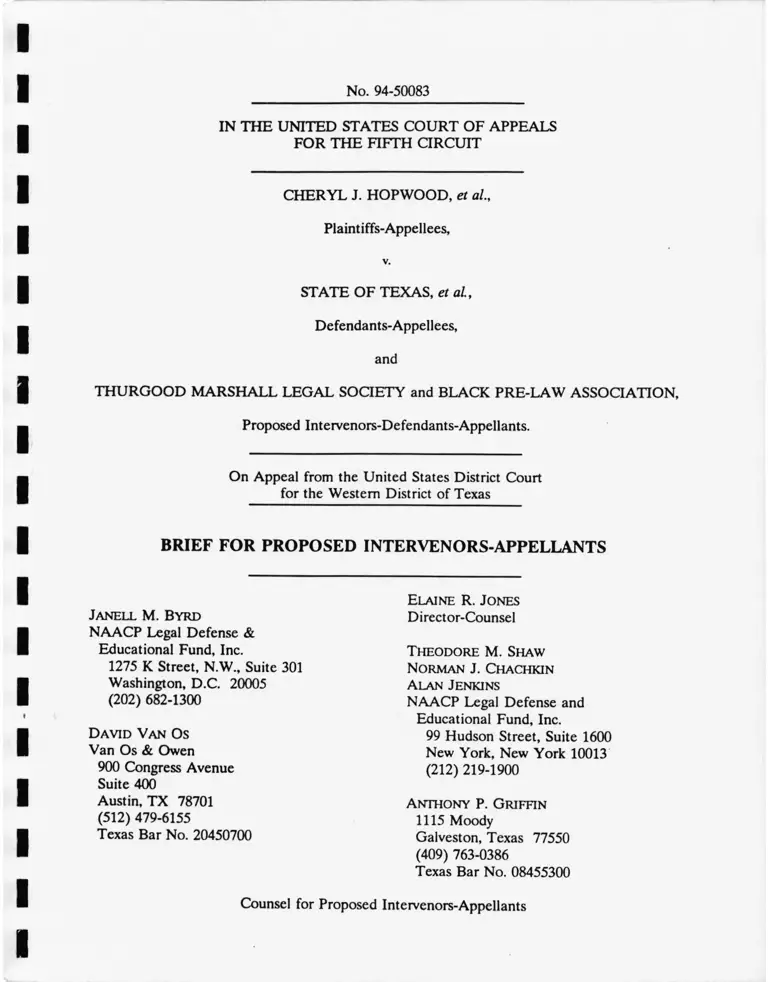

No. 94-50083

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

CHERYL J. HOPWOOD, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

V.

STATE OF TEXAS, et a l,

Defendants-Appellees,

and

THURGOOD MARSHALL LEGAL SOCIETY and BLACK PRE-LAW ASSOCIATION,

Proposed Intervenors-Defendants-Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Texas

BRIEF FOR PROPOSED INTERVENORS-APPELLANTS

Janell M. Byrd

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W., Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

D avid Van Os

Van Os & Owen

900 Congress Avenue

Suite 400

Austin, TX 78701

(512) 479-6155

Texas Bar No. 20450700

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Alan Jenkins

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Anthony P. Griffin

1115 Moody

Galveston, Texas 77550

(409) 763-0386

Texas Bar No. 08455300

Counsel for Proposed Intervenors-Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS.................................................................... i

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL A RG UM ENT............................................................. iii

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION .................................................................................... 1

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUE PRESENTED .................................................................. 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ............................................................................................. 1

I. Proceedings Below........................................................................................................ 1

II. Statement of Facts........................................................................................................ 4

A. The Proposed Intervenors............................................................................... 4

1. Black Pre-Law Association.................................................................. 4

2. Thurgood Marshall Legal Society...................................................... 5

B. History of Discrimination Against

African-American Students By the Defendants ........................................... 7

SUMMARY OF A RG U M EN T................................................................................. 10

ARGUMENT .......................................................................................................................... 13

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN DENYING THE MOTION TO

INTERVENE............................................................................................................... 13

A. The District Court Erred in Concluding that the Defendants Would

Adequately Represent the Proposed Intervenors’ In terests......................... 14

1. Proposed Intervenors’ Interests Are Adverse to Those of the

Defendants ........................................................................................... 15

a. Defendants Have a Long History of Adversity Against

African-American Students as to the Very Issues in

Question in This S u it................................................................. 15

b. Defendants’ Interests As Public Officials and Institutions

Differ From Those of African-American Students ............... 16

2. Denial of Intervention is Particularly Improper Where, As

Here, The Beneficiaries of a Remedial Affirmative Action

Policy Seek to Defend That Policy As a Lawful Response to

Past Discrimination by the Defendant............................................... 18

3. Proposed Intervenors’ Intend to Advance Important Arguments

in Defense of the Plan that the Defendants Will Not M ake............ 20

B. History of Discrimination Against African-American Students

By the Defendants ............................................................................................. 7

C. The Proposed Intervenors Established, and the District Court did Not

Challenge, the Other Requirements for Intervention as of Right .............. 21

1. The Proposed Intervenors Have a Direct Interest in the Law

School’s Admissions Policy .................................................................. 22

2. The Proposed Intervenors’ Ability to Protect Their Interests

will be Impaired if this Action is Allowed to Proceed Without

Their Participation............................................................................... 26

3. The Proposed Intervenors’ Application Was Timely ....................... 28

D. Considerations of Judicial Economy Dictate That TMLS and BPLA

Be Granted Intervention.................................................................................. 29

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ABUSED ITS DISCRETION IN DENYING

PERMISSIVE INTERVENTION............................................................................. 30

CONCLUSION........................................................................................................................ 32

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ............................................................................................. 33

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Adams v. Bell,

Civ. No. 3095-70 (D.D.C. Mar. 24, 1983) .................................................................. 3

Adams v. Hufstedler,

Civ. No. 70-3095 (D.D.C. Dec. 17, 1980) ......................................................... 3, 9, 27

Adams v. Richardson,

356 F. Supp. 92 (D.D.C.), modified and affid

en banc, 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir.

1973) ........................................................................................................................ 9, 10

Associated General Contractors v. City of New Haven,

130 F.R.D. 4 (D.Conn. 1990) .................................................................................... 20

Associated General Contractors v. San Francisco,

35 Empl. Prac. Dec. 34,919 (N.D.Cal. 1985)............................................................. 20

Associated General Contractors v. Secretary of

Commerce, 459 F. Supp. 766 (C.D.Cal 1978) . ! .................................................. 20

Atlantis Development Corp. v. United States,

379 F.2d 818 (5th Cir. 1967) ........................................................................ 11, 26, 31

In re Birmingham Reverse Discrimination Litigation,

833 F.2d 1492 (11th Cir. 1987).................................................................................... 24

Borders v. Rippy,

247 F.2d 268 (5th Cir. 1957) ........................................................................................ 7

Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954) ........................................................................................ 8, 16, 21

Bush v. Vitema,

740 F.2d 350 (5th Cir. 1984) ........................................................................ 13, 14, 15

Cascade Nat. Gas Corp. v. El Paso Nat. Gas Co.,

386 U.S. 129 (1967) .................................................................................................... 13

Chiles v. Thornburgh,

865 F.2d 1197 (11th Cir. 1989).................................................................................... 18

City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co.,

488 U.S. 469 (1989) ............................................................................................. 18, 19

24

Cohn v. EEOC,

569 F.2d 909 (5th Cir. 1978) ..................

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania,

Inc. v. Philadelphia,

No. 89-2737 (E.D.Pa. July 31, 1989) ........................................................................ 20

Diaz v. Southern Drilling Corp.,

427 F.2d 1118 (5th Cir.), cert denied, 400

U.S. 878 (1970) .......................................................................................................... 13

Dimond v. District of Columbia,

792 F.2d 179 (D.C. Cir. 1986) .................................................................................... 28

Federal Savings and Loan v. Falls Chase Special

Taxing District,

983 F.2d 211 (11th Cir. 1993) .................................................................................... 29

Feller v. Brock,

802 F.2d 722 (4th Cir. 1986) ...................................................................................... 27

Flax v. Potts,

204 F. Supp. 458 (N.D.Tex. 1962) ............................................................................... 7

Flax v. Potts,

725 F. Supp. 322 (N.D.Tex. 1989) ............................................................................... 7

Florida Gen. Contractors v. Jacksonville,

508 U.S.__ , 124 L. Ed. 2d 586 (1993)...................................................................... 23

Franklin v. Gwinnett County Public Schools,

503 U.S.__ , 117 L. Ed. 2d 208 (1992)...................................................................... 21

Havens Realty Corp. v. Coleman,

455 U.S. 363 (1982) .................................................................................................... 25

Henry v. First National Bank of Clarksdale,

595 F.2d 291 (5th Cir. 1979), cert denied,

444 U.S. 1074 (1980)................................................................................................... 29

Hines v. D’Artois,

531 F.2d 726 (5th Cir. 1976) ...................................................................................... 15

Hodgson v. United Mine Workers,

473 F.2d 118 (D.C. Cir. 1972) .................................................................................... 28

4

Houston Independent School District v. Ross,

282 F.2d 95 (5th Cir.), cert denied,

364 U.S. 803 (1960)........................................................................................................ 7

Howard v. McLucas,

782 F.2d 956 (11th Cir. 1986) .................................................................................... 24

Hunt v. Washington State Apple Advertising Commn.,

432 U.S. 333 (1977) .................................................................................................... 25

Jansen v. City of Cincinnati,

904 F.2d 336 (6th Cir. 1990) ............................................................................... 19, 20

Kneeland v. National Collegiate Athletic Assn.,

806 F.2d 1285 (5th Cir. 1987) .................................................................................... 18

Knight v. Alabama,

No. 92-6160 (11th Cir. Fed. 24, 1994) ............................................................... 11, 24

McDonald v. E. J. Lavino Co.,

430 F.2d 1065 (5th Cir. 1970) ............................................................................. 13, 31

Meek v. Metropolitan Dade County,

985 F.2d 1471 (11th Cir. 1993)...................................................................... 15, 18, 19

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc.,

426 F.2d 534 (5th Cir. 1970) ............................................................................... 13, 29

NRDC v. Costle,

561 F.2d 904 (D.C. Cir. 1977) .................................................................................... 28

New York Public Interest Research Group v. Regents

of the University of State of New York,

516 F.2d 350 (2d Cir. 1975) ......................................................................... 18, 25, 26

Nuesse v. Camp,

385 F.2d 694 (D.C. Cir. 1967) .................................................................................... 27

Piambino v. Bailey,

610 F.2d 1306 (5th Cir. 1980) ........................................................................ .. . 13, 28

Podberesky v. Kirwan,

838 F. Supp. 1075 (D.Md. 1993)........................................................................... 19, 21

Podberesky v. Kirwan,

956 F.2d 52 (4th Cir. 1992) .................................................................................. 19, 26

5

Ross v. Houston Indep. School Dist.,

699 F.2d 218 (5th Cir. 1983) ........................................................................................ 7

Sagebrush Rebellion, Inc. v. Watt,

713 F.2d 525 (9th Cir. 1983) ...................................................................................... 20

Scotts Valley Band of Pomo Indians v. United States,

921 F.2d 924 (9th Cir. 1990) ...................................................................................... 13

Sierra Club v. Robertson,

960 F.2d 83 (8th Cir. 1992) ........................................................................................ 29

Smith Petroleum Service, Inc. v. Monsanto Chemical

Co., 420 F.2d 1103 (5th Cir. 1970) ........................................................................ 28

Stallworth v. Monsanto Co.,

558 F.2d 257 (5th Cir. 1977) ............................................................................... passim

Sweatt v. Painter,

339 U.S. 629 (1950) .................................................................................... 7, 8, 21, 22

Tasby v. Edwards,

807 F. Supp. 421 (N.D.Tex. 1992) ...................................................................... ........ 7

Trbovich v. United Mine Workers,

404 U.S. 528 (1972) ............................................................................................. 14, 17

United Airlines, Inc. v. McDonald,

432 U.S. 385 (1977) .................................................................................................... 28

United States v. Fordice,

505 U.S.__ , 120 L. Ed. 2d 575 (1992)............................................................... 10, 24

United States v. Oregon,

839 F.2d 635 (9th Cir. 1988) ...................................................................................... 26

United States v. State of Texas,

321 F. Supp. 1043 (E.D.Tex 1970) ............................................................................... 7

United States v. State of Texas,

330 F. Supp. 235 (E.D.Tex. 1970), affid with

modifications, 447 F.2d 441 (5th Cir. 1971), cert

denied, 404 U.S. 1016 (1972) ........................................................................................ 7

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency (AISD),

467 F.2d 848 (5th Cir. 1972) ........................................................................................ 7

6

Women’s Equity Action League v. Cavazos,

906 F.2d 742 (D.C. Cir. 1990) ............................................................................... 9, 10

Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education,

476 U.S. 267 (1986) ................................................................................................... 19

Statutes and Rules: Pages:

28 U.S.C. § 1291 ........................................................................................................................ 1

28 U.S.C. § 1331(a) ................................................................................................................... 1

28 U.S.C. § 1343(3) ................................................................................................................... 1

28 U.S.C. § 1343(4) ................................................................................................................... 1

29 U.S.C. § 482(b) 17

29 U.S.C. § 483 ............................................................................................................ 17

34 C.F.R. § 100.3(b)(6)(i) ........................................................................................................ 9

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ................................................................................................................. 1, 4

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ................................................................................................................... 1, 4

42 U.S.C. § 2000d ...................................................................................................................... 1

Fed. R. Civ. P. 24 ................................................................................................................... 29

Fed. R. Civ. P. 24(a) .......................................................................................................... passim

Fed. R. Civ. P. 24(b), ...................................................................................................... 30, 31

Miscellaneous: Pages:

7C C. Wright, A. Miller & M. Kane, Federal

Practice and Procedure § 1904 (2nd ed. 1986) .................................................. 13, 25

A. Duren, Overcoming: A History of Black Integration

at the University of Texas at Austin 4 (1979) ......................................................... 8 ,9

No. 94-50083

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

CHERYL J. HOPWOOD, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

STATE OF TEXAS, et a l,

Defendants-Appellees,

and

THURGOOD MARSHALL LEGAL SOCIETY and BLACK PRE-LAW ASSOCIATION,

Proposed Intervenors-Defendants-Appellants.

On Appeal from the

United States District Court

for the Western District of Texas

BRIEF FOR PROPOSED INTERVENORS-APPELLANTS

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

The undersigned counsel certifies that the following listed persons have an interest in

the outcome of this case. These representations are made in order that the Judges of this

Court may evaluate possible disqualification or recusal.

1. The plaintiffs in this action: Cheryl J. Hopwood, Douglas W. Carvell, Kenneth

R. Elliott, and David A. Rogers.

2. Counsel for the plaintiffs: Terral R. Smith, Steven W. Smith, Michael P.

McDonald, Joseph A. Wallace, Paul J. Harris, and R. Kenneth Wheeler.

3. The defendants in this action: The State of Texas; The University of Texas

Board of Regents; Board of Regents members Bernard Rapopart, Ellen C. Temple, Lowell H.

Lebermann, Jr., Robert J. Cruikshank, Thomas O. Hicks, Zan W. Holmes, Jr., Tom Loeffler,

Mario E. Ramirez, and Martha E. Smiley, The University of Texas at Austin; Robert M.

Berdahl, President of the University of Texas at Austin; The University of Texas School of Law,

Mark G. Yudof, Dean of the University of Texas School of Law, and Stanley M. Johanson,

Assistant Dean of the University of Texas School of Law.

4. Counsel for the defendants: Harry M. Reasoner, Betty Owens, Barry D.

Burgdorf, R. Scott Placek, Samuel Issacharoff, Charles Alan Wright, and Javier Aguilar.

5. The proposed intervenors-appellants: The Thurgood Marshall Legal Society and

the Black Pre-Law Association of the University of Texas at Austin.

6. Counsel for the proposed intervenors-appellants: Elaine R. Jones, Theodore M.

Shaw, Norman J. Chachkin, Janell M. Byrd, Alan Jenkins, Anthony P. Griffin, and David

Van Os.

Attorney of Record for Proposed

Intervenor^A^pellants

u

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

Proposed intervenors-appellants hereby request that this case be set for oral argument

unless the Court summarily reverses the order entered below. This appeal affects the rights of

African-American students attending or seeking admission to the University of Texas School

of Law and presents important questions concerning the circumstances under which these

students may assert their rights and interests in the federal courts. Appellants believe that oral

argument will be valuable to the Court.

111

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

The Amended Complaint in this action states claims under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981,1983, and

2000d, and asserts subject matter jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331(a) and 1343(3) and (4).

This is an appeal from an order denying proposed intervenors’ motion for intervention on

Januaiy 19,1994. Proposed intervenors filed a timely notice of appeal from the order denying

their Motion to Intervene on January 27, 1994. This Court’s jurisdiction is conferred by 28

U.S.C. § 1291.

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUE PRESENTED

Was it proper to deny a timely motion for intervention filed by two organizations

representing African-American students at the University of Texas in an action brought by

white persons seeking to enjoin any consideration of race in the admissions process of the

University’s law school, where Texas for more than a century operated its entire educational

system on a de jure segregated basis and has never been found by any court or administrative

agency to have eliminated completely the vestiges of that segregation?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

I. Proceedings Below

In this case, unsuccessful white applicants to the University of Texas School of Law (the

"Law School") challenge the Law School’s admissions policy as racially discriminatory in

violation of 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983, and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VI),

42 U.S.C. § 2000d. Specifically, plaintiffs challenge the consideration of race by the Law School

as part of a remedial policy of affirmative action in admissions. Defendants are the State of

Texas, the Board of Regents of the University of Texas, University of Texas at Austin,

1

University of Texas School of Law, and various officials of those institutions and governing

bodies. Proposed intervenors-appellants Thurgood Marshall Legal Society ("TMLS") and Black

Pre-Law Association ("BPLA") are organizations of African-American students at the Law

School and undergraduate college of the University, respectively, who seek to intervene in this

action in order to protect their interest in an affirmative action admissions policy (collectively,

"proposed intervenors").

Plaintiffs filed their first complaints on September 29 ,19921 and April 23, 1993.2 After

limited discovery addressing only the issues of standing and ripeness, defendants moved for

summary judgment on those grounds on August 13,1993. The district court denied defendants’

motion on October 28,1993, and on November 18,1993 the district court authorized the parties

to begin discovery on the merits. The first exchange of documents on the merits phase of the

case did not begin until December 18, 1993.

Proposed intervenors filed a Motion to Intervene on January 5,1994. In support of the

motion, they described in detail their direct legal interest in the existing admissions program,

and in the elimination of the vestiges of past discrimination by the Law School and University.

[Memorandum in Support of Motion to Intervene at 8-11] Record ("R.") 642-5.3 Moreover,

proposed intervenors explained that their ability to protect their interests would be impaired

if this action were allowed to proceed without their participation, icL at 11-12, and stressed that,

given the defendants’ history of discrimination against African-Americans and continuing

adversity of interests with the proposed intervenor organizations and their members, the

'Complaint of Cheryl Hopwood and Stephanie C. Haynes.

2Complaint of Plaintiffs Carvell, Elliott, Arnold, Rogers and Armstrong.

References to the record ("R.") are derived from the civil docket sheet provided to

proposed intervenors by the Clerk of the United States District Court for the Western District

of Texas.

2

existing parties could not adequately represent proposed intervenors’ interests in this case. Id

at 13-15. Finally, proposed intervenors established that their application was timely (coming

immediately after denial of the motion for summary judgment and at the beginning of discovery

on the merits); that they would be well represented by counsel; and that, in addition to

intervention as of right, permissive intervention was appropriate. Id at 15-17.

Also in support of the motion, proposed intervenors included as exhibits: (1) the

declarations of the student officers of the proposed intervenor organizations; (2) the

constitutions and bylaws of those organizations; (3) excerpts from the University of Texas’

Educational Opportunity plans (compiled for the U.S. Department of Education/Health

Education and Welfare ("HEW") as part of the University’s desegregation obligations); (4) the

district court’s unpublished order in Adams v. Hufstedler, Civ. No. 70-3095 (D.D.C. Dec. 17,

1980), requiring HEW to issue orders of compliance or noncompliance with Title VI as to the

Texas System of Higher Education; and (5) the district court’s unpublished order in Adams v.

Bell, Civ. No. 3095-70 (D.D.C. Mar. 24, 1983), noting that Texas had failed to eliminate the

vestiges of its racially dual system and requiring the Department of Education to commence

formal Title VI proceedings against Texas. [Exhibits A-F, Memorandum in Support of Motion

to Intervene] (R. 654-725).

The Defendants filed a response stating that they did not oppose the motion to

intervene. On January 14, 1994, Plaintiffs filed a three-page "Response to Motion to

Intervene," opposing the motion. [Plaintiffs’ Response to Motion to Intervene at 1-2] (R. 739-

39). Plaintiffs’ Response did not include a brief and cited no legal authority in support of its

assertions. Nor did it include any supporting declaration or other factual proffer.

On January 19,1994, the district court issued an order denying the motion to intervene.

The court concluded that TMLS and BPLA could not intervene as a matter of right because

3

they failed to demonstrate that their legal interests would not be adequately represented by the

State Defendants. [Order Denying Motion to Intervene at 4] (R. 746). As to permissive

intervention, the district court did not dispute that proposed intervenors had shown an

independent ground for jurisdiction, that the motion was timely, or that proposed intervenors’

defenses and the main action have a question of law or fact in common; rather, the court

concluded that "adding the prospective intervenors as defendants at this juncture in the lawsuit

would needlessly increase cost and delay disposition of the litigation." Id. at 5.

Plaintiffs filed an amended complaint on February 1, 1994, adding several parties and

reasserting claims under Title VI and 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983. [First Amended Complaint]

(R. 785-808).

II. Statement of Facts

A. The Proposed Intervenors

1. Black Pre-Law Association

The Black Pre-Law Association of the University of Texas at Austin is an organization

of African-American undergraduate students with an interest in attending law school.4 The

organization was founded in 1987 and has approximately twenty members. BPLA’s chief

organizational goal is to increase the number of African-American students entering law school

by promoting African-American students’ interest in the law, assisting these students in the

application and admissions process, and preparing them for the rigors of law school and the

legal profession. Many of BPLA’s members have an interest in attending the University of

Texas School of Law and each year, some of its members apply to the Law School. [Exhibit

4The BPLA Constitution and the declaration of BPLA’s president, Suneese Haywood, were

before the district court as Exhibit B to the Memorandum in Support of Motion to Intervene.

(R. 669-78).

4

B, HH 4, 7, 9, 10 to Memorandum in Support of Motion to Intervene (Declaration of Suneese

Haywood)] (R. 671-2).

Each year BPLA dedicates its fall semester activities to the application and admissions

process and its spring semester activities to education about the legal profession. In the past

semester, BPLA’s admissions activities included organizing lectures by Law School Admissions

Test (LSAT) instructors, law school admissions officers, and law school students. BPLA seeks

to aid students interested in attending UT Law School by providing information about the Law

School’s admissions process. In the past semester, members of the Thurgood Marshall Legal

Society (also proposed intervenors in this suit) attended a BPLA meeting to provide

information and answer questions about the admissions process and the study of law at the

University of Texas. Id. UH 7-10.

Finally, as part of its effort to provide its members with insight into the legal profession,

BPLA sponsors discussions with attorneys and other professionals regarding the practice of law

and the role of law in society. Id. H 11.

2. Thurgood Marshall Legal Society

The Thurgood Marshall Legal Society is an organization of students at the Law School

dedicated to serving the needs of African Americans.5 Founded in 1983 as a chapter of the

National Black Law Students Association, TMLS is open to all students but is predominantly

African-American in its membership. Over 60 of the Law School’s 108 African-American

students are members of TMLS. [Exhibit A, HH 5, 6 to Memorandum in Support of Motion

to Intervene (Declaration of April Cheatham)] (R. 656).

5TMLS’s Constitution, and the Declaration of the organization’s president, April Cheatham,

were included as Exhibit A to the Memorandum in Support of Motion to Intervene. (R. 659-

68).

5

TMLS’s central goals are to encourage the admission, retention, and academic success

of greater numbers of African-American scholars at the Law School; to promote an academic

and social atmosphere that is both attractive and receptive to students of color, and to combat

discrimination and its effects on the Law School campus and elsewhere. Toward these ends,

TMLS engages in a wide range of activities on campus and in the community at large. Id 11

8-13.

In order to attract African-American students to the Law School, TMLS plays an

important role by answering African-American prospective students’ questions about the Law

School. In addition, TMLS has created the Heman Sweatt endowed scholarship to enable

economically disadvantaged African-American students to attend the Law School. Members

of the organization also serve as student participants on the admissions committee and actively

participate in the recruitment of African-American candidates through the Law School’s

"Project Info" and the Student Recruitment and Opportunities Committee. Id. HU 9, 10.

As part of its efforts to improve the retention of African-American students at the Law

School, and to foster academic excellence among these students, TMLS conducts extra

curricular academic sessions for first year students in which faculty and other students review

course work and mock examinations. TMLS is also actively involved in public service activities

for the benefit of African-American and low-income residents of the Austin, Texas community,

ranging from voter registration drives to canned food collections and meals for needy families.

Id. 11, 12.

Finally, as a major vehicle for communication and participation in campus issues, TMLS

attempts to participate in debate and policy making surrounding most issues of discrimination

and racial diversity that arise on the Law School campus, including such matters as faculty

diversity, cultural affairs and community awareness. Id U 14.

6

B. History of Discrimination Against African-American Students

By the Defendants

Educational segregation in Texas was pervasive, affecting both the State’s secondary and

elementary schools and its colleges and universities. See, e.g., Houston Independent School

District v. Ross, 282 F.2d 95, 96 (5th Cir.), cert denied, 364 U.S. 803 (1960); Borders v. Rippy,

247 F.2d 268 (5th Cir. 1957) (Dallas); United States v. Texas Educ. Agency (AISD), 461 F.2d 848

(5th Cir. 1972) (Austin); Flax v. Potts, 204 F. Supp. 458 (N.D.Tex. 1962) (Ft. Worth); United

States v. State o f Texas, 321 F. Supp. 1043 and 330 F. Supp. 235 (E.D.Tex. 1970), aff’d with

modifications, 447 F.2d 441 (5th Cir. 1971), cert denied, 404 U.S. 1016 (1972) (state-wide relief).

While some of these systems were declared unitary in the late 1980’s, this was after the period

when the proposed intervenors’ members were attending secondary school. See, e.g., Flax v.

Potts, 725 F. Supp. 322 (N.D.Tex. 1989) (Ft. Worth). Still, many Texas school districts have not

been declared unitary, see, e.g., Tasby v. Edwards, 807 F. Supp. 421 (N.D.Tex. 1992) (Dallas),

and those that have received such declarations not on the ground that no vestiges of the

invidious discrimination remained, but on the ground that no practicable remedy existed. See,

e.g., Ross v. Houston Indep. School Dist, 699 F.2d 218, 224, 228 (5th Cir. 1983); Flax v. Potts,

725 F. Supp. at 330.

The University of Texas School of Law operated from the mid-1800’s until the Supreme

Court’s decision in Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950), with official admissions policies and

practices that precluded the attendance of persons of African descent. The Texas Constitution

and state statutory provisions restricted the school to white students, id. at 631, and at the time

Heman Sweatt applied for admission to the Law School in 1946, no law school in the State of

Texas admitted African Americans. Ibid. The Law School was required to change its

admission practices only through the legal challenge brought by an African-American student.

7

Following the Sweatt decision in 1950, however, the racially exclusionary practices of the

State did not radically change. From 1950 through the 1960’s African Americans were admitted

to and graduated from the Law School in token numbers at best.6 Moreover, the University

continued to deny blacks admission to the University’s undergraduate college restricting them

to other, separate all-black Texas schools until the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board

o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). A. Duren, Overcoming: A History o f Black Integration at the

University o f Texas at Austin 4 (1979) (Hereinafter "Overcoming"). African-American

undergraduates were relegated to officially segregated and inadequate housing facilities at least

until 1964, ten years after the Brown decision. Overcoming at 6,8-10, 14. Extra-curricular

activities remained segregated during the same period. Id. at 8. The first African American

assistant professor was not appointed until 1961. Id. at 42. The first full professor in 1968.

Ibid.

In 1970, the Board of Regents eliminated two programs designed to facilitate the

admission and retention of African-American and Mexican-American students. The first was

the Program on Educational Opportunity which brought 25 minority undergraduate students

to UT in 1969. Overcoming at 20. The second was the Council on Legal Education

Opportunity (CLEO), a program specifically designed to bring meaningful numbers of

African-American and Mexican-American students to the Law School. Id at 22. Within a year

of the termination of the CLEO program at UT Law School, the Law School had no African

Americans in its entering class and only five Mexican Americans. Ibid The 1971 Law School

class contained "only two or three blacks and five or six Mexican Americans." Id at 27. The

6As late as 1972, there were only three black students in the Law School’s entering class.

Texas Educational Opportunity Plan for Public Higher Education, 1989-1994, University of

Texas at Austin, September 1, 1989, at 118. Excerpt attached to Memorandum in Support of

Motion to Intervene as Exhibit C. (R. 680, et seq.).

8

1973 class contained three African Americans. Texas Educational Opportunity Plan, 1989-1994

at 118. In a 1974 Law School class of about 1,600, there were only 10 African Americans.

Overcoming at 32.

In 1970, a class of African-American students in 17 Southern and border states,

including Texas, sued the United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare,

asserting that the federal government’s funding of state systems of higher education that

discriminated against African Americans by operating segregated institutions of higher

education violated the Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Federal Constitution.

Adams v. Richardson, 356 F. Supp. 92 (D.D.C.), modified and affd unanimously en banc, 480

F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973), dismissed sub nom Women's Equity Action League v. Cavazos, 906

F.2d 742 (D.C. Cir. 1990). The district court ordered the government to enforce Title VI in

higher education and other areas. Id., 356 F. Supp. at 94-100.

In 1980, the Adams plaintiffs sought further relief with respect to the higher education

systems in Texas and other states. In 1981 the Office for Civil Rights of the United States

Department of Education ("OCR") found that Texas had failed to eliminate the vestiges of its

former racially dual system. See Adams v. Bell, Civ. No. 70-3095, Order of March 24, 1983 at

5.7 Thereafter, Texas submitted desegregation plans to OCR in an effort to come into

compliance with Title VI, but OCR found those plans to be inadequate. On March 24, 1983,

the district court ordered OCR to commence formal enforcement proceedings against Texas

"within 45 days," unless OCR concluded that Texas had submitted a desegregation plan in full

conformity with governing law. Id. at 7. Governing law included the Education Department’s

’Exhibit D to Memorandum in Support of Motion to Intervene (R. 698, et seq.).

9

Title VI regulations, in particular 34 C.F.R. § 100.3(b)(6)(i),8 which required Texas to adopt

affirmative action measures to redress the effects of its racially discriminatory higher education

system. After the 1983 Adams order, Texas submitted an amended plan to OCR in which it

committed itself to improved measures to meet enrollment goals for black and Hispanic

students in its professional schools. OCR approved that plan on June 14, 1983.9

The affirmative action admissions program under which the Law School currently

operates is central to the State’s compliance with Title VI and the mandates of OCR. The

program was developed as a remedy for past discrimination against African-American students

and was adopted as a result of the legal challenges brought by these students. Plaintiffs in this

case seek a permanent injunction prohibiting the use of an affirmative action admissions policy

by the Law School. [First Amended Complaint at 23] (R. 808).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Proposed intervenors, organizations of African-American and other students at the

University of Texas at Austin and the University of Texas Law School, have demonstrated their

entitlement to intervention as of right under Fed. R. Civ. P. 24(a).

Proposed intervenors have a substantial interest in the continuation of the affirmative

action admissions program. As organizations of current and prospective students at the Law

School, they are entitled under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to the assurance that the opportunity to gain admission

8That subsection provides: "[i]n administering a program regarding which the recipient [of

federal funds] has previously discriminated against persons on the ground of race . . . the

recipient must take affirmative action to overcome the effects of prior discrimination."

’Texas Equal Educational Opportunity Plan for Higher Education, as amended through

May 16, 1983, at 151-52, relevant excerpt attached as Exhibit E to Memorandum in Support

of Motion to Intervene (R. 708, et seq.).

10

and enjoy fully the educational opportunities offered by the Law School is not impaired by the

continuing effects of the State’s former racially dual educational system. See United States v.

Fordice,__ U.S.___ , 120 L.Ed.2d 575, 592 (1992); Knight v. Alabama, No. 92-6160, Slip op.

at 5 (11th Cir. Fed. 24, 1994).

The relief plaintiffs seek would impair the ability of TMLS and BPLA to protect the

constitutional and statutory rights of their members by prohibiting the very relief obtained by

African-American students to remedy the vestiges of racial segregation and discrimination in

the Texas educational system. Thus, this case has not only the possibility of creating an adverse

stare decisis effect for TMLS and BPLA in any subsequent action — a circumstance which itself

demonstrates an impairment of rights sufficient to warrant intervention of right, see Atlantis

Development Corp. v. United States, 379 F.2d 818 (5th Cir. 1967); the immediate impact of a

ruling for plaintiffs on the admission, retention and graduation of African Americans at the

Law School also clearly infringes on BPLA’s and TMLS’s interests so as to warrant intervention

in this action.

The State of Texas does not adequately represent the interests of TMLS, BPLA or their

members, and the district court erred in concluding otherwise. First, there is a long history of

adversity between the State defendants and African-American students as to the central issue

involved in this case — the provision of educational opportunities free from the vestiges of the

racially dual educational system. Second, while the State defendants will defend their right to

operate an affirmative action admissions program at the Law School, as state officials and

public institutions, the defendants necessarily are required to serve broad, diffuse, and at times

conflicting interests. TMLS and BPLA directly represent the interests of African-American

students and others who seek to enhance the racial diversity of the Law School and the

representation of African Americans in the legal profession. Their interests are uniform and

11

focused on this goal. Third, the legal standard for permissive race-conscious remedies pits the

diverse legal interests of the State defendants, including the State’s interest in avoiding future

litigation by third parties, against those of TMLS and BPLA. Finally, because of these

divergent interests, it is expected that BPLA and TMLS will develop the record and advance

essential arguments that the State defendants will not make. For example, proposed

intervenors would offer evidence of recent discriminatory practices, evidence of a hostile racial

climate on campus, and evidence casting doubt on the predictive validity of the Texas Index (a

combination of undergraduate grades and LSAT scores) used in the admission process. The

State’s ability and willingness to advance such positions are at best severely constricted.

Finally, BPLA and TMLS moved in a timely fashion to seek intervention. Discovery was

bifurcated for procedural and merits issues. Prior to October 28, 1993, there was no need for

TMLS and BPLA to intervene because only the standing and ripeness issues were being

addressed and a decision on either of those bases could have eliminated the entire action.

After the October 28, 1993 denial of the State’s summary judgment motion, on November 18,

1993, the district court authorized the parties to proceed with discovery on the merits. The first

exchange of documents thereafter occurred on December 18, 1993. TMLS and BPLA filed

their motion for intervention on January 5, 1994. It was more than a month later before

depositions on the merits began.

It is important that TMLS and BPLA be allowed to intervene to protect their

constitutional rights and those of their members, to avoid potential collateral attack on the

district court judgment, and to save judicial resources by having all interested parties before the

court when these issues are resolved.

12

ARGUMENT

I.

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN DENYING THE MOTION TO INTERVENE

As this Court has observed, the rules governing intervention are to be construed broadly,

in favor of the proposed intervenor. Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d 534, 537

(5th Cir. 1970) (footnote omitted); see also Scotts Valley Band o f Porno Indians v. United States,

921 F.2d 924, 926 (9th Cir. 1990); 7C C. Wright, A. Miller & M. Kane, Federal Practice and

Procedure § 1904 (2nd ed. 1986). Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 24(a) provides in pertinent

part:

Upon timely application anyone shall be permitted to intervene in an

action . . . when the applicant claims an interest relating to the property or

transaction which is the subject of the action and the applicant is so situated that

the disposition of the action may as a practical matter impair or impede the

applicant’s ability to protect that interest, unless the applicant’s interest is

adequately represented by existing parties.

Thus, in order to merit intervention as of right under Fed. R. Civ. P. 24(a), a proposed

intervenor need only demonstrate (1) that it has an interest in the subject matter of the action,

(2) that disposition of the action may practically impair or impede the movant’s ability to

protect that interest, and (3) that the interest is not adequately represented by the existing

parties. Diaz v. Southern Drilling Corp., 427 F.2d 1118, 1124 (5th Cir.), cert denied, 400 U.S.

878 (1970). The application must also be timely under the circumstances of the case.

Stallworth v. Monsanto Co., 558 F.2d 257, 263 (5th Cir. 1977).10

“Ehe denial of a motion to intervene is appealable and is to be reviewed de novo by this

Court. Cascade Nat Gas Corp. v. El Paso Nat Gas Co., 386 U.S. 129, 135 (1967) (construing

both pre-1966 F. R. Civ. P. 24(a) and amended Rule); Bush v. Vitema, 740 F.2d 350, 355 n.8

(5th Cir. 1984); Piambino v. Bailey, 610 F.2d 1306, 1320 (5th Cir. 1980). The question of

timeliness, not reached by the district court in this case, is committed to the discretion of the

district court. McDonald v. E. J. Lavino Co., 430 F.2d 1065, 1071 (5th Cir. 1970).

13

In their filings below, proposed intervenors demonstrated each of these elements

through uncontroverted declarations, and public state and federal documents. The lower court

did not dispute that proposed intervenors had met the interest, impairment, or timeliness

requirements. Rather, the district court denied the motion on the sole ground that, in the

court’s view, proposed intervenors had failed to demonstrate inadequate representation by the

existing parties. [Order Denying Intervention at 4] (R. 746).

As proposed intervenors make clear below, the district court erred in concluding that

the State of Texas, Texas institutions of higher education and their officials who are named as

defendants in this suit adequately represent the distinct interests of the proposed intervenor

organizations and their members, who are primarily but not exclusively African-American.

Because proposed intervenors have interests that are adverse to those of the defendants, and

because the other requirements of Rule 24(a) are established, this Court should reverse the

district court’s denial of intervention.

A. The District Court Erred in Concluding that the Defendants Would Adequately

Represent the Proposed Intervenors’ Interests

The Supreme Court has made clear that the burden of demonstrating inadequate

representation is "minimal." Trbovich v. United Mine Workers, 404 U.S. 528, 538 n.10 (1972).

The requirement "is satisfied if the applicant shows that representation of his interest ‘may be'

inadequate . . . ." Ibid, (emphasis added). Thus, while the district court was correct that a

rebuttable presumption of adequate representation exists when proposed intervenors seek the

same ultimate objective as an existing party, Bush v. Vitema, 740 F.2d 350, 355 (5th Cir. 1984),

"[tjhis presumption, like any, serves to guide a court’s analysis of the facts. It is not a substitute

for facts, nor is it to be given any weight if the facts tend to contradict the presumed result."

14

Meek v. Metropolitan Dade County, 985 F.2d 1471, 1477 (11th Cir. 1993). Accordingly, this

Court has repeatedly held that the presumption of adequate representation is clearly rebutted

where, as here, the existing party has an interest that is potentially adverse to those of the

proposed intervenor. See, e.g., Bush, 740 F.2d at 355-56; see also Hines v. D Artois, 531 F.2d

726, 738 (5th Cir. 1976) (granting intervention to state examiner in municipal employment

discrimination suit where "[h]is interests . . . may not coincide completely with those of

defendants below").

In the instant case, the State defendants have legal interests that are unquestionably

adverse to those of TMLS, BPLA and their student members. This adversity arises from the

defendants’ status as governmental entities, from the continuing history of civil rights

enforcement by minority students against these defendants, and from the very nature of the

legal showing necessary to defend affirmative action programs. Because their interests are both

independent of and adverse to those of the defendants in several key respects, proposed

intervenors would advance several essential and independent arguments in support of the

admission plan that the existing defendants cannot or will not articulate. Proposed intervenors’

interests cannot, therefore, be adequately represented by these defendants.

1. Proposed Intervenors’ Interests Are Adverse to Those of the Defendants

a. Defendants Have a Long History of Adversity Against

African-American Students as to the Very Issues in Question in

This Suit

As described above, there has been a forty-year histoiy of legal adversity between the

State defendants and African-American students as to the precise subject of this litigation: the

elimination and remediation of racial exclusion and its continuing effects. It was an

African-American applicant, Heman Sweatt, who first challenged segregation at the University

15

of Texas Law School in 1946. It was African-American students who sued OCR to require

meaningful desegregation efforts by the University of Texas and other Southern educational

institutions in 1970, and it was African-American students who returned to court in 1980 to

obtain, inter alia, full relief against the State of Texas. Throughout this period, the University

of Texas vigorously opposed these students’ efforts to eliminate the vestiges of its formerly dual

system. It was not until Texas was threatened with an OCR enforcement action that might

have caused it to lose all of its federal funding that the State adopted a remedial plan that the

federal government found satisfactory.

The history of legal adversity between African-American students and the State’s

elementary and secondary educational system is equally long and contentious. Forty years after

Brown v. Board o f Education, many Texas schools that operated de jure segregated systems have

not yet been declared racially unitaiy. Other districts only achieved unitary status in the late

1980’s -- the period during which both the plaintiffs and the proposed intervenors’ members

were attending secondary schools. Still others were declared unitary because there was no

practicable remedy for the remaining vestiges. While some progress has been made in recent

years, in light of this pattern it defies reason to assert, as the district court did, that the interests

of African-American students seeking to reverse the effects of racial discrimination by the State

of Texas and its institutions will unquestionably be vigorously and adequately represented in

that endeavor by those very institutions.

b. Defendants’ Interests As Public Officials and Institutions Differ

From Those of African-American Students

As state officials and institutions, the existing defendants in this case are bound to serve

the public interest: a broad range of concerns, some of which conflict with the narrower

16

interests of proposed intervenors. The Supreme Court recognized in Trbovich v. United Mine

Workers, 404 U.S. 528 (1972), that this type of conflict requires that intervention be granted.

In Trbovich, a union member sought to intervene in a suit brought by the Secretary of Labor

to set aside a union election under the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act

(LMRDA).11 Although the LMRDA designates the Secretary as the sole entity authorized

to initiate such suits on behalf of union members,12 the Supreme Court found intervention as

of right to be required, rejecting the Secretary’s argument that he would adequately represent

the member’s interests. In so doing, the Court recognized the difference between the union

member’s interest in a lawful election and the broader "public interest" pursued by the

Secretary. In addition to protecting the rights of union members, "the Secretaiy has an

obligation to protect the vital public interest in assuring free and democratic union elections

that transcends the narrower interest of the complaining union member.. . . Both functions are

important, and they may not always dictate precisely the same approach to the conduct of the

litigation." 404 U.S. at 538-39 (internal quotations omitted).

The same dichotomy of interests exists in the instant case. While the existing defendants

seek in a broad sense to defend the Law School’s admissions policy, they are bound and limited

in doing so by a broad range of public interests and concerns. For example, defendants must

balance the competing interests of the student body, faculty, educational goals, fiscal

responsibilities, administrative concerns, and public opinion. In contrast, proposed intervenors’

interest in this case is sharply focused on preserving an admissions policy that remedies the

effects of past discrimination and fosters an atmosphere that is attractive and receptive to

African-American students and applicants. As this and other courts have recognized, this

n29 U.S.C. § 482(b).

“29 U.S.C. § 483.

17

divergence of interests presents an unacceptable risk that representation will be inadequate.

See, e.g., Kneeland v. National Collegiate Athletic Assn., 806 F.2d 1285, 1288 (5th Cir. 1987)

(recognizing adversity of interests arising from "conflicts between agency attempts to represent

the regulated parties and statutory mandates to serve the ‘public interest’") (citations omitted);

Chiles v. Thornburgh, 865 F.2d 1197, 1214-15 (11th Cir. 1989) (alien detainees have distinct

interest in conditions of confinement that may not be served by county government concerned

with effect of institution on outside community); Meek v. Metropolitan Dade County, Fla., 985

F.2d 1471, 1478 (11th Cir. 1993) (while voters sought to intervene in voting rights suit solely

to defend at large system, county commissioner defendants "had to consider the overall fairness

of the election system,. . . the expense of litigation,. . . and the social and political divisiveness

of the election issue"); New York Public Interest Research Group v. Regents o f the University o f

State o f New York, 516 F.2d 350, 352 (2d Cir. 1975) (putative intervenors, an association of

pharmacists, had a narrower, economic interest in regulatory statute than did the defendant

Regents). The existing defendants’ zone of interests in this case, including public and political

considerations and administrative costs, conflicts in important ways with those of the proposed

intervenors.

2. Denial of Intervention is Particularly Improper Where, As Here, The

Beneficiaries of a Remedial Affirmative Action Policy Seek to Defend

That Policy As a Lawful Response to Past Discrimination by the

Defendant

Race-conscious remedies such as the Law School’s admissions policy are lawful when

they are narrowly tailored to address the continuing effects of past discrimination. City o f

Richmond v. JA.. Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469, 491-92 (1989). Thus, a key element of the defense

in the instant case will be evidence of past racial discrimination by the defendant institutions

18

and continuing effects or vestiges of that discrimination, including the racial atmosphere and

reputation for discrimination currently existing at the institution. Although an institution need

not demonstrate that it is presently liable for unlawful racial discrimination in order to defend

a race-conscious remedial plan, Wygant v. Jackson Board o f Education, 476 U.S. 267, 286 (1986)

(opinion of O’Connor, J.), it must demonstrate a "strong basis in evidence for its conclusion

that remedial action was necessary." Croson, 488 U.S. at 500, quoting Wygant, 476 U.S. at 277

(plurality opinion); Podberesky v. Kirwan, 956 F.2d 52, 57 (4th Cir. 1992).

Clearly this standard pits the diverse legal interests of the defendants, including their

interest in avoiding future litigation by third parties, against those of affected African

Americans in preserving affirmative anti-discrimination remedies. See, e.g., Jansen v. City o f

Cincinnati, 904 F.2d 336, 343 (6th Cir. 1990) (where city and African-American putative

intervenors disagreed as to factual predicate for affirmative action plan, intervention, must be

granted).

In addition to the threat of subsequent litigation, the public airing of an institution’s

history of discrimination against particular groups is contrary to that institution’s political,

financial and reputational interests. See, e.g., Podberesky v. Kirwan, 838 F. Supp. 1075, 1082

n.47 (D.Md. 1993) (noting that a university defending an affirmative action program is put in

the "unusual position" of having "to engage in extended self-criticism in order to justify its

pursuit of a goal that it deems worthy"); see also Meek v. Metropolitan Dade County, Fla., 985

F.2d 1471, 1478 (11th Cir. 1983) (in defending at-large voting system, County Commissioners

"were likely to be influenced by their own desires to remain politically popular and effective

leaders" as well as "the social and political divisiveness of the election issue"). These factors are

likely to influence the defendants’ commitment to the litigation, the legal arguments adopted,

19

and the evidence produced at trial in a way that will prejudice proposed intervenors’ interest

in preserving a meaningful remedy for past discrimination.

In light of such considerations, courts have routinely granted intervention to the minority

beneficiaries of race-conscious anti-discrimination remedies seeking to defend such programs.

See, e.g, Jansen v. City o f Cincinnati, supra, Associated General Contractors v. San Francisco, 35

Empl. Prac. Dec. 34,919 (N.D.Cal. 1985) (allowing minority business concerns to intervene in

constitutional challenge to city’s race-conscious contracting ordinance); Associated General

Contractors v. City o f New Haven, 130 F.R.D. 4, 11 (D.Conn. 1990) (same); Contractors

Association o f Eastern Pennsylvania, Inc. v. Philadelphia, No. 89-2737, slip op. at 1 (E.D.Pa. July

31, 1989) (allowing minority contractors’ association to intervene to represent "private"

interests); Associated General Contractors v. Secretary o f Commerce, 459 F. Supp. 766, 771

(C.D.Cal 1978) (allowing civil rights organizations to intervene in challenge to federal

affirmative action program).

3. Proposed Intervenors’ Intend to Advance Important Arguments in

Defense of the Plan that the Defendants Will Not Make

Another consideration in assessing the adequacy of representation by existing parties is

"whether [the defendant] will undoubtedly make all of the intervenor’s arguments, whether [the

defendant] is capable of and willing to make such arguments, and whether the intervenor offers

a necessary element to the proceedings that would be neglected." Sagebrush Rebellion, Inc. v.

Watt, 713 F.2d 525, 528 (9th Cir. 1983) (citations omitted). If allowed to participate as parties

in this case, proposed intervenors would make essential arguments and introduce important

evidence that the defendants cannot or will not advance.

20

For example, proposed intervenors intend to present evidence of racial segregation and

discrimination by defendants from the period after the Sweatt and Brown decisions to the very

recent past. While such evidence is important to demonstrating the existing effects of past

discrimination, see generally Podberesky v. Kirwan, 838 F. Supp. 1075 (D.Md. 1993), defendants

are unlikely to produce such evidence due to the considerations of potential civil rights liability,

OCR compliance, and other constraints described above.

Proposed intervenors also will seek to demonstrate that a racially hostile environment

continues to exist at the University of Texas. See Podberesky, 838 F. Supp. at 1092-94 (racially

hostile campus a present effect of past discrimination). This showing also potentially implicates

Title VI liability, See Franklin v. Gwinnett County Public Schools,___U.S.___ , 117 L.Ed.2d 208

(1992) (damages available for sexual harassment under Title IX of Education Amendments of

1972, companion statute to Title VI), and the defendants cannot be expected to advance such

an argument. Additionally, proposed intervenors’ defense of the existing admissions program

may cast doubt on the predictive value of the Texas Index — a combination of undergraduate

grades and LSAT scores -- in the selection of applicants. Each of these arguments, and others

intervenors expect to advance, is important to this case yet contrary to the defendants’

institutional interests. Under the circumstances, proposed intervenors’ interests are plainly not

represented by the defendants.

C. The Proposed Intervenors Established, and the District Court did Not Challenge,

the Other Requirements for Intervention as of Right

The district court did not dispute that proposed intervenors had demonstrated the other

criteria for intervention as of right: an interest in the subject of the suit; impairment of their

ability to protect that interest absent intervention; and timely filing. Stallworth v. Monsanto, 558

21

F.2d 257,263,269 (5th Cir. 1977). Moreover, proposed intervenors demonstrated each of these

elements in the court below, supported by uncontroverted documentation. Proposed

intervenors continue to meet each of these requirements.

1. The Proposed Intervenors Have a Direct Interest in the Law School’s

Admissions Policy

Proposed intervenors have a significant, protectable interest in the subject matter of this

suit — the gravamen of which is an effort to enjoin permanently the Law School from operating

a race-conscious affirmative action admissions program. [First Amended Complaint at 23] (R.

808). Should plaintiffs prevail, the result would impede the proposed intervenors’ significant

interest in remedying the harm caused by the defendants’ dual educational system, and the

subsequent pattern of discrimination against African-Americans.

The affirmative action admissions program serves as a remedy for the State’s segregation

and discrimination against African Americans in several ways. As outright exclusion of African-

Americans from the Law School was the centerpiece of the dual system, the current admissions

policy facilitates the admission of meaningful numbers of black students to the Law School.

By attracting and matriculating more African-American students and, in particular, those who

are highly likely to be successful, the admissions policy creates a more receptive and less

isolating experience for black law students, thereby aiding long-term retention and graduation.

In addition, the policy aids the recruitment and retention of African-American law students by

sending a strong message to prospective and current students that the Law School of Sweatt v.

Painter is committed to reversing its past discriminatory practices. The affirmative action

admissions program is central to any effort to achieve these goals.

22

The State’s system of elementary and secondary education has a similar history of

separate and unequal operation. The discriminatory denial of equal educational opportunity

to African Americans during their formative academic years is directly related to the

underrepresentation of African Americans in the Law School applicant pool. The challenged

admissions policy also addresses the effects of that discriminatory pattern.

In addition to remedying the dearth of African-American legal scholars and attorneys

caused by past discrimination, the admissions policy also addresses other vestiges of the former

system. By attracting and admitting meaningful numbers of qualified African-American

students, the policy seeks to eliminate the institutional reputation for discrimination, the racially

hostile atmosphere and the stigmatic message of inferiority and exclusion that are part and

parcel of segregated systems. The program also increases ethnic and ideological diversity on

campus, to the benefit of all students. Each of these goals directly implicates the interests of

the proposed intervenor organizations and their African-American members.

BPLA’s central organizational objective is to increase the number of African-American

legal scholars entering the University of Texas and other law schools.13 This goal is furthered

significantly by the affirmative action admissions program at the Law School. Beyond its

organizational goals, the members of BPLA are primarily African-American undergraduates,

many of whom will apply and be considered under the Law School’s admissions policy. BPLA

members, therefore, have a direct interest in a program that will aid their admission to law

school. Cf. Florida Gen. Contractors v. Jacksonville, 508 U.S.__ , 124 L.Ed.2d 586, 599 (1993)

(where organization’s members regularly bid on defendant’s public contracts, organization has

standing to challenge impediments to successful bid). As the current admissions policy is

UBPLA Constitution, Art. I, II, Exhibit 1 to Exhibit B of Proposed Intervenors’

Memorandum in Support of Motion to Intervene (R. 674).

23

designed primarily to correct the former policy of whites-only admissions, BPLA members also

have an interest in being considered under a policy that addresses that past racial exclusion.

TMLS’s key organizational goals include encouraging a racially mixed student body and

eliminating racial discrimination at the Law School.14 Both of these goals are furthered by the

existing admissions program. Moreover, TMLS’s members are current students at the Law

School who will be affected directly by the institution’s success or failure in efforts to eliminate

the racially isolating and deleterious effects of past discrimination. There is no doubt that

African-American students have a direct and legally protectable interest in ensuring that an

institution of higher learning "has met its affirmative duty to dismantle its prior dual university

system." United States v. Fordice, 505 U.S.___, 120 L.Ed.2d 575, 592 (1992); see also id. at 590

(recognizing role of private plaintiffs); Knight v. Alabama, No. 92-6160, Slip op. at 5 (11th Cir.

Feb. 24, 1994) (recognizing interest identified in Fordice).

An adverse ruling in this case would have an immediate negative impact both on the

Proposed intervenors’ organizational interests and on the interests of their members because,

in all likelihood, it would decrease substantially the number of African Americans entering and

graduating from the Law School. Moreover, elimination of an affirmative action admissions

policy would greatly exacerbate the racial isolation, negative racial atmosphere, and other

remnants of past discrimination against African Americans by the defendants. Proposed

intervenors’ interests are directly implicated by this litigation. See Cohn v. EEOC, 569 F.2d 909

(5th Cir. 1978) (existing employees have interest in ensuring that anti-discrimination remedy

does not improperly displace them); In re Birmingham Reverse Discrimination Litigation, 833

F.2d 1492, 1496 n.13 (11th Cir. 1987) (same); Howard v. McLucas, 782 F.2d 956 (11th Cir.

14TMLS Constitution, Art. I, §B, Exhibit 1 to Exhibit A of proposed intervenors’

Memorandum in Support of Motion to Intervene (R. 659).

24

1986) (same); New York Public Interest Research Group, Inc. v. Regents o f Univ. o f New York,

516 F.2d 350, 351-52 (2d Cir. 1975) (per curiam) (pharmaceutical organization has interest in

enforcement of regulation from which its members benefit); 7C C. Wright, A. Miller, & M.

Kane, Federal Practice and Procedure: Civil 2d, § 1908 at 285 (1986) ("in cases challenging

various statutory schemes as unconstitutional or as improperly interpreted and applied, the

courts have recognized that the interests of those who are governed by those schemes are

sufficient to support intervention").

The Supreme Court has recognized that organizations such as TMLS and BPLA have

significant legal interests in their own right and as representatives of their members when their

organizational goals or interests are threatened. In Havens Realty Corp. v. Coleman, 455 U.S.

363, 379 (1982), for example, the Court recognized for standing purposes that a Virginia

nonprofit corporation whose purpose was to "make equal opportunity in housing a reality in

the Metropolitan Richmond Area" had a significant legal interest in challenging violations of

the Fair Housing Act by Richmond area realtors. Id. at 368. The Court found that there was

no question that the organization suffered a legal injury in fact by the alleged racial steering

practices that impaired its ability to accomplish its organizational goal. Id at 379. Similarly,

in Hunt v. Washington State Apple Advertising Commn., 432 U.S. 333, 342-45 (1977), the Court

recognized the standing of the State Apple Advertising Commission in a representational

capacity to protect the interests of the State’s apple growers. In this case, BPLA and TMLS

have a protectable legal interest both in their own right (in defending their organizational goals)

and on behalf of their members who are the beneficiaries of the challenged policy.

Moreover, proposed intervenors’ interest in the subject of this litigation is both

immediate and direct. If plaintiffs persuade the district court to enjoin the current admissions

25

policy, the resulting impediment to the admission of African Americans, decline in enrollment,

and increased racial isolation will be felt immediately by TMLS, BPLA and its members.

2. The Proposed Intervenors’ Ability to Protect Their Interests will be

Impaired if this Action is Allowed to Proceed Without Their Participation

If allowed to stand, the district court’s denial of leave to intervene will fundamentally

impair TMLS’s and BPLA’s ability to protect their interests. First, if TMLS and BPLA are

denied intervention, the negative stare decisis effect of an adverse decision in this case would

in all likelihood permanently prevent proposed intervenors’ from preserving the current

admissions policy through subsequent litigation. Potential adverse stare decisis effects are alone

sufficient to demonstrate impairment of interest so as to warrant intervention as of right.

Atlantis Development Corp. v. United States, 379 F.2d 818 (5th Cir. 1967); New York Public

Interest Research Group, 516 F.2d at 352; United States v. Oregon, 839 F.2d 635, 638 (9th Cir.

1988). In Atlantis, supra, this Court reversed a district court denial of intervention to a

development company that claimed ownership of coral reefs in a case in which the federal

government had sued other parties to protect the reefs from commercial development. The

Atlantis Court held that the potential application of stare decisis jeopardized the company’s

interests in the subject matter of the suit (title to the reefs) so as to require intervention as of

right. Id at 828-29.

The same result should obtain in the instant case. Key factual issues in this litigation

include whether there are present effects of past discrimination and whether the affirmative

action remedial program is appropriately tailored to address those present effects. See

Podberesky v. Kirwan, 956 F.2d 52, 55 (4th Cir. 1992). The predicate factual finding made by

OCR — that the Texas educational system has failed to eliminate the vestiges of its dual

26

system — was obtained through litigation and administrative advocacy by African-American

students, predecessors of the current members of TMLS and BPLA. Adams v. Hufstedler, Civ.

No. 70-3095, Consent Order (D.D.C. December 1980).15 A contraiy resolution of the question

of continuing vestiges, or of issues regarding the appropriate scope of a remedial plan will

clearly have a prohibitive stare decisis effect on any subsequent litigation proposed intervenors

could bring to eliminate the effects of past discrimination through race-conscious programs.

In addition to the adverse effect of stare decisis, the injunctive relief sought by plaintiffs

would immediately and detrimentally alter the process under which the applications of current

BPLA members and other African Americans will be considered. Elimination of the existing

admissions policy would also rapidly effect the African-American student body at the Law

School. Irrespective of the precedent created by this case, proposed intervenors would almost

certainly be unable to correct this immediate harm through collateral litigation.

Finally, participation by proposed intervenors in this case as amici curiae would not

provide sufficient protection against these practical impairments because it would not allow

them to participate fully in the case, to present evidence, to file motions, or to appeal a final

judgment in the litigation. See, eg., Feller v. Brock, 802 F.2d 722, 730 (4th Cir. 1986); Nuesse

v. Camp, 385 F.2d 694, 704 n.10 (D.C. Cir. 1967). In particular, TMLS and BPLA cannot

introduce the necessary evidence of past discrimination by the defendants, and its continuing

effects, without full participation as parties in this case.

“Exhibit F to Memorandum in Support of Motion to Intervene (R. 721).

27

3. The Proposed Intervenors’ Application Was Timely

Proposed intervenors’ motion was timely under Rule 24(a). The relevant inquiry for

timeliness purposes is the point at which the proposed intervenor knew or should have known

that its interests would not be adequately represented by the existing parties. See, e.g., United

Airlines, Inc. v. McDonald, 432 U.S. 385, 394 (1977) ("as soon as it became clear to the

[intervenor] that the interests of the unnamed class members would no longer be protected by

the named class representatives, she promptly moved to intervene to protect those interests");

Piambino v. Bailey, 610 F.2d 1306, 1321 (5th Cir. 1980) ("the question of timeliness is at least

partially linked to the question of adequate representation"); Stallworth v. Monsanto, 558 F.2d

257,264-65 (5th Cir. 1977) (timeliness determined based on time intervenor knew of its interest

in the case or that its interest might not be represented adequately). Applying this principle,

"courts have allowed intervention months or even years after the original filing of the suit where

the substantial litigation of the issues had not been commenced when the motion to intervene