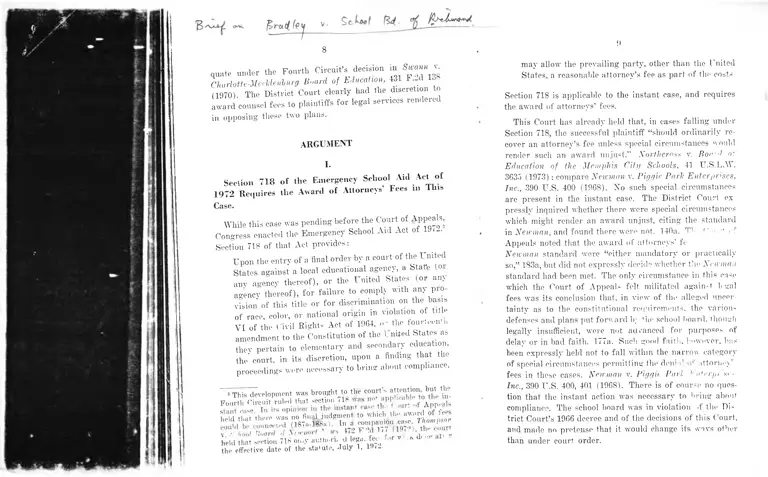

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond Brief, 1972. 043aaeba-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f7f376af-f586-4e5e-833c-4ab51cb79673/bradley-v-school-board-of-the-city-of-richmond-brief. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

% n ik < j v-

8

fOj^kuMt-

quate under the Fourth Circuit’s decision in Swami v.

Chadotte-Mecldenburg Board of Education, 431 F d lo,

(1970) The District Court clearly had the discie ion o

award counsel fees to plaintiffs for legal services rendered

in opposing these two plain.

argument

I.

Section 7 1 8 o f the E m ergency School Aid Act o f

1 9 7 2 R equ ires the Award o f A ttorneys’ Fees m T his

Case.

While this case was pending before the Court of Appeals,

Congress enacted the Emergency School Aid Act of 19(2.

Section 718 of that Act provides:

Upon the entry of a final order by a court of the United

States against a local educational agency, a State (oi

anv agencv thereof), or the United States (or am

agency thereof), for failure to comply with any pio-

vision of this title or for discrimination on the basis

of race, color, or national origin in violation of title

VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. o • the fourteenth

amendment to the Constitution of the United States as

they pertain to elementary and secondary education,

the court in its discretion, upon a finding that the

proceedings w ere necessary to bring about compliance.

3 This development was brought to the court’s attention but the

Fourth C i r c u i t e d that section 718

heldthaTtlun-c1w aTnoW Judgment to‘which the award of fees

16 i i i „ , n 87 a 188a') In a companion case. Tliompsor

held that section 718 omy aiulw ri, U lega. fee

the effective date of the statute, -July 1, l 9 ' -

«)

may allow the prevailing party, other than the United

States, a reasonable attorney’s fee as part of the costs

Section 718 is applicable to the instant case, and requires

the award of attorneys’ fees.

This Court has already held that, in cases falling under

Section 718, the successful plaintiff “should ordinarily re

cover an attorney’s fee unless special circumstances would

render such an award unjust." Northcross v. Bor'd oi

Education of the Memphis City Schools, 41 U.S.L.A.

3635 (1973) ; compare Newman v. Biggie Park Enterprises,

Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968). Xo such special circumstances

are present in the instant case. The District Court ex

presslv inquired whether there wrere special circumstances

which might render an award unjust, citing the standard

in Newman, and found there were not. 140a. T1- < '■•urt rf

Appeals noted that the award of attorneys’ tV

Newman standard were “either mandatory or practically

so,” 183a, but did not expressly decide whether the A ewman

standard had been met. The only circumstance in this case

wdiich the Court of Appeals felt militated again-t legal

fees was its conclusion that, in view of the alleged uncer

tainty as to the constitutional requirements, the various

defenses and plans put forward b; the school board, though

legally insufficient, were not advanced for purposes of

delay or in bad faith. 177a. Such good faith, however, has

been expressly held not to fall within the narrow category

of special circumstances permitting the denial attorney

fees in these cases. Newman v. Biggie Bari. I n*i>rpi s e

ine., 390 U.S. 400, 401 (1968). There is of course no ques

tion that the instant action was necessary to bring about

compliance. The school board was in violation -f the DU

trict Court’s 1966 decree and of the decisions of this Court,

and made no pretense that it would change its wavs other

than under court order.

10

Section 718 further requires that legal fees may be

awarded “upon the entry” of a final order against a de

fendant school board based on a violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment or certain statutes. The quoted phrase does

not require, of course, that the award of legal fees be

simultaneous with the entry of such an order, but makes

the existence of such a final order a prerequisite to the

award of attorneys’ fees. Several such orders had been

entered and became final prior to the award of attorneys’

fees in this case on May 26, 1971.4 Where, as here, the

course of litigation in a district court involves the entry

of several orders over a period of months or years, neither

section 718 nor sound judicial administration require that

the question of legal fees be litigated separately and repe-

titiously upon the occasion of each such order. A request

for fees may present difficult questions of fact or require

tm- :ai.nig of evidence which might interfere with a court’s

simultaneous efforts to dismantle a dual school system.

Costs, of which attorneys’ fees are made a part by section

718, are normally imposed after the final disposition of

the case. Doubtless a District Court has discretion to

award costs and attorneys’ fees incident to the disposition

of interim lelief matters, 6 Moore’s Federal Practice

TJ54. /0 T5], and it would be particularly desirable to exercise

that discretion where, as is common in litigation under

Brown, the fashioning of effective relief occurs over a

period of years and delay in awarding fees and costs may

work hardship on plaintiffs or their counsel. That discre-

On June 20, 1970, the District Court ordered a suspension of

all school construction in Richmond pending the approval of a

final plan. On August 17, 1970. the District Court ordered into

operation an interim plan for the 1970-71 school year. On April 5,

1971. Me District Court ordered into operation the plan under

which the Richmond schools are now operating. Each of these

orders had become final when the attorneys’ fees were awarded on

May 26, 1970.

11

tion, however, exists for the protection of the plaintiff and

his attorney; a defendant cannot be heard to complain if

it is not so exercised.5

The defendant school board maintains, however, that

section 718 should not be applied to the instant case because

the legal services for which fees are sought were rendered

piioi to July 1, 1972, the date on which section 718 became

effective.6 'Plaintiffs contend that section 718 should be

applied to any case in which the propriety of an award

of legal fees was still pending resolution on appeal as of

July 1, 1972, regardless of when the services were per-

foimed. This case does not present the question of whether

section 718 should be applied, retroactively, to cases in

v hich the question of legal fees had been presented and

been resolved by a final order prior to July 1, 1972.

Since United States v. Schooner Peggy, this Court has

i ecognized that “if, subsequent to the judgment, and before

the decision of (he appellate court, a law intervenes and

positively changes the rule which governs, the law must

be obeyed, or its obligation denied.” 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 103,

D The Court of Appeals refused to apply section 718 to the in

stant case on the ground, inter alia, that on the effective date of

the Act there was no final order regarding the substantive claim

qt discrimination pending on appeal (187a-188a). This standard,

m the sense it was used, could never be met, for no order could

be both final and also pending on appeal. If, as plaintiffs contend,

section 718 should apply to services performed prior to July 1

1<<2. there is no precedent for requiring that such fees be arbi

trarily denied because of the date on which an order was entered

directing the desegregation of a defendant school district.

6 The date on which a law becomes effective is not the same

thing as the date from which the law shall apply. The former date

describes the time at which the courts will begin to invoke the

law in dealing with events or transactions; the latter date delimits

the class of events or transactions as to which that law may be

invoked. For an example of a statute specifying both effective

hate and the transactions to which it applied, see section 104 of

the Jury .Selection Act of 1968, Pub L 90-274

12

106 (1801). This Court has applied on appeal intervening

changes in the law under a wide variety of circumstances.

In Thorpe v. Housing Authority of Durham, 393 U.S. 268

(1969), after the plaintiff public housing authority had

won an eviction order in state courts, the Department of

Housing and I rban Development altered the procedural

prerequisites to such evictions. This Court held that the

defendant could not be evicted unless the new procedures

were followed. “The general rule . . . is that an appellate

coui t must apply the law in effect at the time it renders

its decision.” 393 U.S. at 281. In United States v. Alabama,

362 U.S. 602 (I960), the district court dismissed an action

brought by the United States under the 1957 Civil Rights

Act against the state of Alabama on the ground that the

State could not be sued under that statute. While the case

was pending on appeal Congress passed the 1960 Civil

A,-t expressly authorizing suits against a state, and

tin.- Court applied the new statute. “Under familiar prin

ciples, the case must be decided on the basis of law now

controlling, and the [new provisions] are applicable to this

litigation.” 362 U.S. at 604. In Ziffrin v. United States,

after a company seeking permission to operate as a con

tract carrier had filed its application with the Interstate

Commerce Commission, the Interstate Commerce Act was

amended to bar such operation by an applicant who was

controlled by a common carrier serving the same territory.

This Court upheld the application of the new law to the

pending request. “A change in the law between a nisi prius

and an appellate decision requires the appellate court to

apply the changed law. A fortiori, a change of law pending

an administrative hearing must be followed in relation to

permission for future acts.” 318 U.S. 73, 78 (1943). See

also Vanderhark v. Owens-Illinois Glass Company, 311 U.S.

538 (1941); Carpenter v. Wabash Raihvay Co., 309 U.S. 23,

27 (1940), and cases cited; American Steel Foundries v.

13

Tri-City Cent. Trades Council, 257 U.S. 184, 201 (1921);

Reynolds v. United States, 292 U.S. 443, 449 (1934).

Except where the statute involved expressly purports

to be of exclusively prospective application, see e.g. Gold

stein v. California, 41 U.S.L.W. 4829, 4830 (1973), this

Court has routinely applied new laws to all cases pending

on appeal, v ithout reference to legislative history and

without rerfuiring express statutory language that they be

so applied. When Congress has concluded that greater

justice would be done if a new and different legal principle

were applied to some recurring circumstances, Congress

must be presumed to have intended that that new standard

and .the more equitable result entailed be applied to all

eases, including those pending on appeal. Compare John

son v. United States, 163 F.2d 30, 32 (1st Cir. 1908)

(Holmes, J.).

A narrowly drawn exception to this practice has been

sanctioned by this Court where, under the facts of a par

ticular case, application of a new law to a matter arising

before its enactment would work an unfair hardship on one

of the parties. In such a situation this Court has, where

possible, sought to construe the statute to avoid such an

inequitable result. The precise category of cases to which

this exception applies has never been clearly defined. In

United States v. Schooner Peggy, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 103

(1801), this Court urged such a rule of construction “in

mere private cases between individuals.” 5 U.S. at 106.

In Union Pacific Railroad Co. v. Laramie Stock Yards Co.,

this Court explained the rule applied to statutes which

might interfere with “antecedent rights,” 231 U.S. 190,

199 (1913). Cox v. Hart defined a “retroactive” statute as

one which impaired a vested right or imposed a new obli

gation on a private interest, and indicated that statutes

should not readih lie construed as “retroactive” in this

14

sense. 260 TJ.S. 427, 435 (1922). In Claridge Apartments

Co. v. Commissioner, 323 U.S. 141 (1944), the Court de

liberately construed a new tax law so as not to retroac

tively increase the taxes on “closed transactions.” 323 U.S.

at 164. In Greene v. United States, 376 U.S. 149 (1963),

this Court refused to apply new and more strenuous ad

ministrative procedures for obtaining remuneration to a

claimant who had already obtained a “final” and favorable

determination under the old procedures. 376 U.S. at 161.

Most recently, in Thorpe v. Housing Authority of Durham,

this Court characterized Greene and its predecessors, more

simply and more cogently, as exceptions “made to prevent

manifest injustice.” 393 U.S. at 282.7

The application of section 718 to the instant case would

work no injustice such as that threatened in Greene. Sec-

18 did not alter the defendant school board’s consti-

tiiimnal responsibility to provide an education free of the

' The difference between the rule reaffirmed in Thorpe and the

exception applied in Greene is well illustrated by the facts in those

cases. Both <-ases involved disputes between a private citizen and

a government agency. In Thorpe a city public housing authority

had sued to evict the defendant tenant; in Greene a private citizen

who had been discharged when the Department of the Navy re

voked his security clearance brought an action for lost wages.

In both, while the litigation was still pending and before Mr.

Greene had received reimbursement or Mrs. Thorpe been evicted,

the procedures for reimbursement and eviction, respectively, were

changed. However, in Thorpe the application of the new rule

accrued to the benefit of the private citizen, whereas in Greene

this Court refused to apply the change where the beneficiary would

have been the government not the individual litigant. In Greene

the application of the new rule would have interfered with a right

to reimbursement which had been established and became final,

37G U.S. at 161; in Thorpe the Housing Authority had no com

parable rights to infringe, 393 U.S. at 283. And, while in Thorpe

the tenant had insisted throughout the litigation that she was

entitled to procedural protections guaranteed b}r the new provision,

in Greene the government had never questioned the procedures

H ing followed until seven years after the litigation began, those

procedures were altered by administrative regulations. Compare

Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe, 401 U S 402 418-

419 (.19711.

15

stigma of segregation, and plaintiffs do not seek to apply

retrospectively any new standard of conduct first estab

lished in 1972. The school board’s substantive obligations

are those of the Constitution, as announced by this Court;

section 718 only elaborates the remedy available to a pri

vate citizen when local officials have violated the law. As

Senator Cook remarked during the debate on section 718: \

The 14th amendment to the Constitution of the

United States was there long before we [Congress]

came to a conclusion that something should be done

in the field of discrimination in the school system of

the United States. We are not talking about some

thing that was born yesterday.8

The school board in the instant case does not claim it would

have acted any differently between 1966 and 1972 had sec

tion 718 been in effect at that time. Under such circum

stances;' the application of section 718 to litigation occur

ring before its effective date can hardly be said to be

unfair. The only relevant right which existed prior to the

enactment of section 718 was the right of the instant plain

tiffs to an education in a unitary school system; applica

tion of section 718 to this case serves not to impair that

right but to vindicate it. Plaintiffs’ assertion that they are

entitled to attorneys’ fees is not a new claim suddenly

asserted in the light of section 718; such fees were asked

in the original complaint filed in 1961,9 and have repeatedly

been sought in the proceedings since that time.

That legal fees should be awarded under section 718 for

work done before its effective date is supported by the

” 117 Cong. R pc 11528.

9 See 4a.

16

legislative history of the Emergency School Aid Act of

1972.10

Section 718 grew out of a provision contained in a

bill sponsored by Senator Mondale in 1971. The statute

proposed by Senator Mondale would have authorized the

payment of counsel fees out of federal funds specially

set aside for that purpose, $5 million for the first year

and $10 million for the second. That proposal, included

in the committee bill presented to the Senate, expressly

stated that the award would be “for services rendered, and

costs incurred, after the date of the enactment of this

Act . . .”n (Emphasis added) On the floor of the Senate,

10 The predecessor to section 718 was first proposed by Senator

Mondale. S. 683, 92nd Cong., 1st Sess., §11. It was reported out

of committee as section 11 of S.1557. See Sen. Rep. No. 92-61,

12116 ( ug.. 1st Sess. On April 21, 1971, at the urging of Senators

I)":.1:1 irk and Cook, section 11 was stricken from the proposed

bill. 117 Cong. Rec. 11338-11345. The next day, on an amendment

sponsored by Senator Cook, section 718 in its present form was

inserted in the bill. 117 Cong. Rec. 11521-11529, 11724-26. The

House amended the bill passed by the Senate, striking everything

after the enacting clause and inserting a new text which, inter aim,

deleted any mention of counsel fees. The provision for legal fees

was restored in conference. Conference Rep. No. 798, 92nd Cong.,

2nd Sess. (1972). The only debate on the subject of attorneys’

fees occurred in the Senate on April 21 and 22, 1971.

11 Section 11(a) of Senator Mondale’s bill, S.683, 92nd Cong.,

1st Sess., provided in fu ll:

Upon the entry of a final order by a court of the United States

against a local educational agency, a State (or any agency

thereof), or the Department of Health, Education, and Wel

fare for failure to comply with any provision of this Act,

title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of

1965 or discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national

origin in violation of title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

or of the fourteenth article of amendment to the Constitution

of the United States as they pertain to elementary and sec

ondary education, such court shall award, from funds reserved

pursuant to section 3 (b )(1 )(e ), reasonable counsel fee, and

costs not otherwise reimbursed, for services rendered, and

17

Senator Dominick, with the support of Senator Cook, suc

cessfully amended the bill to delete this proposed section

in its entirety.12 The next day, however, Senator Cook

proposed to substitute new provisions authorizing the

award of such attorneys’ fees against the defendant.13

This new provision deleted the language in Senator Mon

dale’s version which had limited the section to services

rendered after its enactment. This Court should not read

back into section 718 the very limitation regarding appli

cation to services performed prior to enactment which was

deliberately removed from the statute by Congress.

The application of section 718 to cases pending when it

was enacted serves to carry out the purposes of that pro

vision ,as expressed in the congressional hearings and

debates leading to its enactment. Senator Mondale, who

first urged a statutory authorization of legal fees in these

cases, argued that his proposal and that of Senator Cook

were needed to encourage more private litigation,14 and to

equalize the legal resources available to litigants in such

cases.15 If, however, such fees are only awarded for work

done after July 1, 1972, and after the entry of a final order

resulting from and subsequent to those services, substantial

additional funds under this section for the increase of

costs incurred, after the date of enactment of this Act to the

party obtaining such order.

Similarly, the Committee Report states that the federal funds

are available “for services rendered, and costs incurred, after the

date of enactment of the Act,” Sen. Rep. No. 92-61, 92nd Cong.,

1st Sess., pp. 55-56 (1971).

12117 Cong. Rec. 11345.

13117 Cong. Rec. 11520-21.

14114 Cong. Rec. 10760, 10761, 10762-3. 10764, 11339-40, 11343,

11344, 11345.

'J Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Education of the Senate

Labor and Public Welfare Committee, 92nd Cong., 1st Sess. 99

(1971); 114 Cong. Rec. 10762.

18

private litigation will not be available for years.16 It is

hardly likely that Senator Mondale envisioned or desired

such a delay when he called for a statutory right to legal

fees to meet the “urgent need” for vigorous private litiga- |

tion to resolve the “major crisis in the enforcement of con

stitutional protections affecting civil rights in this land.”17

Senator Cook, the draftsman and sole spokesman for

section 71S as finally enacted, emphasized an additional

reason for his amendment. Senator Cook opposed Senator

Mondale’s proposal on the ground that it failed to require

that the school system which had violated the law pay the

costs incurred in rectifying that violation. He urged:

[M ]e can solve the problem by merely inserting the |

language that the costs and attorneys’ fees will be

nraetieal realities of school litigation are such that the

-hit by Senator Mondale will be substantially delayed if

attorneys fees are not awarded for services performed prior to the

effective date of the statute. The vast majority of school deseg

regation cases have in the past been, and will continue to be,

brought by a handful of private attorneys supported in many in

stances by national organizations concerned with such litigation.

The costs and salaries of the attorneys must be paid by those

organizations or sacrificed by those attorneys from the moment a

case is begun, but such costs and fees are only available under

section 718 after a final judgment has been entered in the case.

The delay between the commencement of an action and the entry

of any final judgment will often be substantial. In the cases de- ’

eided sub nom. Thompson v. School Board of the City of Newport

hews, 472 F.2d 177 (1972), in which the Fourth Circuit refused to

apply section 718 to work done before its effective date, the com

plaints initiating those actions had first been filed in 196l( 1965,

1969 and 19/0. If section 718 is limited to work done after ju lv l ’

1972, it will be years before that statute yields sufficient legal fees

to enable private attorneys and their organizational sponsors to

increase the number of school desegregation cases they are finan

cially able to handle. On the other hand, if such fees are made

available now in appropriate pending cases for work done before

July 1. 1972, the resources will be available at once to make pos

sible the increase in such litigation sought by Congress.

17 117 Cong. Rec. 10760, 10762. See also 117 Cong. Rec. 11339

11342, 11343, 11344.

19

charged against the losing litigant. . . . We can even

charge those expenses and make them a debt against

the Title I funds, so that we are penalizing the person

who violates the law; tve are penalizing the person

who decides the 14th amendment is for someone else

and not for him. We are then imposing the cost on

that individual who saiv fit to commit an act that the

court concluded was in violation of the law, or in viola

tion of the proper utilization of Title I funds and

that, as an indirect result thereof, that person shall

suffer.18

In the debates on his own amendment, Senator Cook re

iterated his desire to place the cost of litigation on the

“guilty party”,19 to assure that a school board violating the

law will “pay for it”,20 and to provide that those who have

disobeyed the constitution “should have to make recom

pense for that mistake.” 21 Senator Cook also referred, as

had Senator Mondale,22 to the inequity of paying with edu

cation funds for the lawyers who unsuccessfully opposed

integration, but not using those funds for attorneys who

achieved an end to segregation.23

1S117 Cong. Rec. 11343 (Emphasis added). See also 117 Cone

Rec. 11341, 11342.

19117 Cong. Rec. 11725.

20117 Cong. Rec. 11527.

21 117 Cong. Rec. 11528.

22 Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Education of the Senate

Labor and Public Welfare Committee, 92nd Cong., 1st Sess. 99

(1971) “Now, most of the money today being spent publicly

m school desegregation cases is public money which is being spent

for lawyers and legal fees to resist the reach of the 14th amend

ment, So why would it not be fair to set aside a modest amount to

pay lawyers who are successful in enforcing the Constitution for

legal fees and costs.”

23117 Cong. Rec. 11527, 11528.

20

It is reasonable to assume that Congress contemplated

that the injustices discerned by Senator Cook would be

righted in cases still pending when section 718 became

effective. It cannot plausibly be maintained that Senator

Cook intended that, months or years after the enactment

of section 718, school boards which had violated the law

would be able to avoid recompensing those who corrected

their mistakes merely because the plaintiffs’ attorneys were

diligent enough to bring that violation to an end prior to

July 1,1972.21 The statute involved here is not one intended

merely to shape future events by encouraging.the initiation

of litigation under the Fourteenth Amendment, compare

Linkletter v. Walker. 381 U.S. 618 (1965), but was designed

to effectuate Congress’ judgment that a serious injustice

is worked when, in a case such as this, the offending school

board pays no price for its years of ignoring Brou n, while

"svate plaintiff must look to himself and the generosity

ol his counsel or the public to meet the costs of enforcingO

the constitution. Compare Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368

(1964). In deciding who shall ultimately bear the cost of

litigation to end discrimination in the public schools, this

-4 Both Senator Mondale and Senator Cook explained that their

"oal was to provide the same right to attorneys’ fees in school

discrimination cases as exist for discrimination in housing. 42

U.S.C. §3G 12(c), in employment, 42 U.S.C. $2000e-5(A), and^pub-

hc accommodations, 42 U.S.C. §2000a-e(b). 117 Cong. Rec. 11339.

(Remarks of Senator Mondale), 11521 (Remarks of Senator Cook)

See North cross x. Board of Education of the Memphis City Schools,

41 L.S.L.W. 3635 (1973). In the absence of special circumstances,

a successful plaintiff in a housing, employment or public accom

modations case would be entitled to attorneys’ fees for all the legal

services performed in connection with a ease won on April 5, 1972

(the day final relief was awarded here) or July 1, 1972 (the day

section 718 became effective). Because the substantive rights and

counsel fee provisions were created by the same statute, sections

2000a-3(b), 2000e-5(k) and 3612(c), 42 U.S.C., apply to all actions

described therein, regardless of when commenced. Congress pre

sumably intended to create a similarly broad right covering all

work done in all school cases.

21

Court should give full effect to the standards and values

established by Congress in section 718 in all cases in which

the question of attorneys’ fees has not been finally resolved

before July 1, 1972.

II.

A ttorneys’ Fees Must Be Awarded Because This

Litigation B enefited O lliers.

In the absence of an express statutory requirement of

attorneys’ fees, federal courts in the exercise of their

equitable powers may award such fees where the interests

of justice so require. Their authority to do so derives

from Article I I I25 of the Constitution and, in cases such

as this, section 1983, 42 U.S.C.26 As Justice Frankfurter

noted a generation ago, the power to award such fees “is

part of the original authority of the chancellor to do equity

in a particular situation.” Sprague v. Ticonic National

Bank, 307 U.S. 161, 166 (1939). Federal courts do not

hesitate to exercise this inherent equitable power wherever

“overriding considerations indicate the need for such a

recovery.” Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375,

391-92 (1970).

One well-established case in which such fees are awarded

is where a plaintiff’s successful litigation confers “a sub

stantial benefit on the members of an ascertainable class,”

and where the court’s jurisdiction over the subject matter

of the suit makes possible an award that will operate to

spread the costs proportionately among them. Mills v.

25 “Section 2. -Jurisdiction. The judicial power shall extend to all

Cases, in law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws

of the United States, and Treaties made . . .” (Emphasis added.)

26 Section 1983 authorizes “an action at law, suit in equity, or

other proper proceeding for redress.” (Emphasis added.)

^6 <£>-** . U/A . (, A>-<- ^ ^ ^