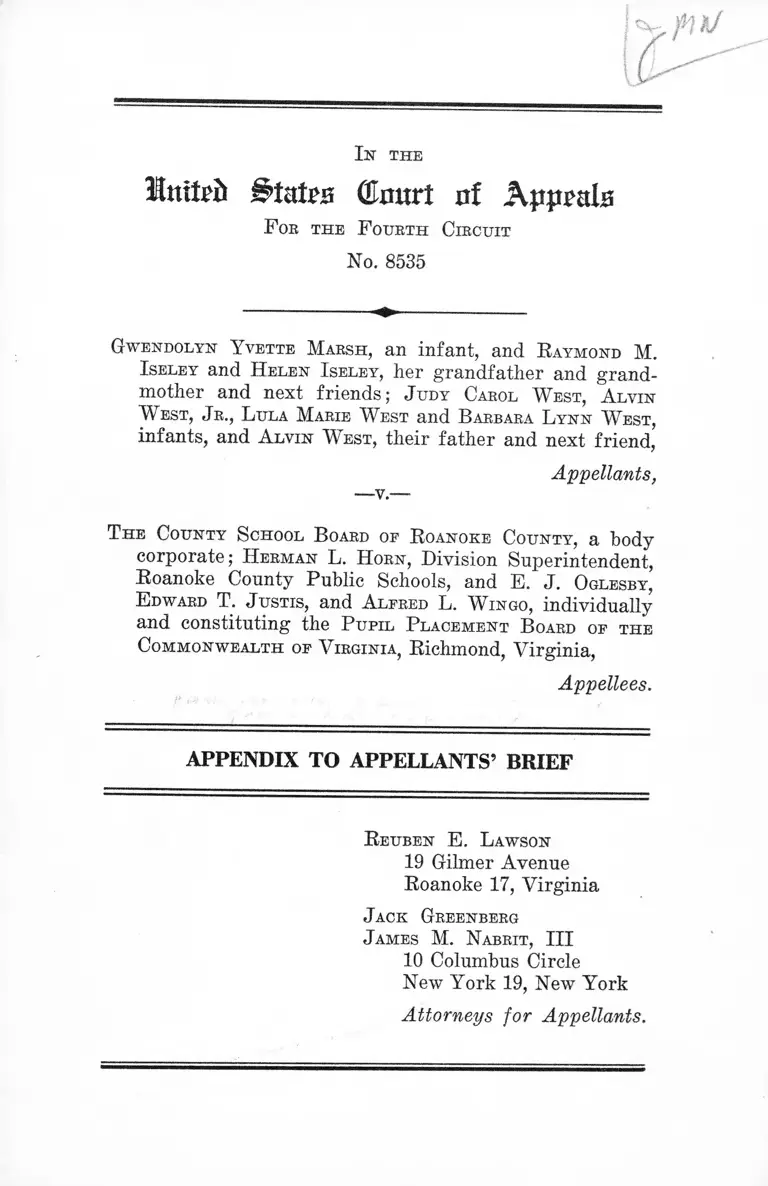

Marsh v The County School Board of Roanoke County Appendix to Appellants Brief

Public Court Documents

November 30, 1961

135 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Marsh v The County School Board of Roanoke County Appendix to Appellants Brief, 1961. cc306b0e-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f7fbf289-4868-471a-bd71-d44dd357aff5/marsh-v-the-county-school-board-of-roanoke-county-appendix-to-appellants-brief. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

S t a t e s (E n u rt u f A p p e a l s

F oe t h e F o u rth C ir cu it

No. 8535

G w en d o lyn Y vette M arsh , an in fa n t, and R aym ond M .

I seley and H elen I seley , h er g ra n d fa th e r and g ra n d

m oth er and n ext fr ie n d s ; J udy C arol W est , A lvin

W est, J r ., L u la M arie W est and B arbara L y n n W est ,

in fa n ts , and A l v in W est , th e ir fa th e r and n ext fr ien d ,

Appellants,

T h e C o u n ty S chool B oard of R oanoke C o u n t y , a body

corporate; H erm an L. H orn , Division Superintendent,

Roanoke County Public Schools, and E . J . O glesby,

E dward T. J u stis , and A lfred L. W ingo , individually

and constituting the P u p il P lacem en t B oard of th e

C o m m o n w e a lth of V irgin ia , Richmond, Virginia,

Appellees.

APPENDIX TO APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

R euben E. L aw son

19 Gilmer Avenue

Roanoke 17, Virginia

J ack G reenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellants.

I N D E X

PAGE

Relevant Docket Entries ................................. ........... la

Complaint ..................................................................... 3a

Motion to Dismiss and Answer of Defendants, The

County School Board of Roanoke County and Her

man L. Horn, Division Superintendent of Schools 15a

Answer of the Pupil Placement B oard...................... 21a

Excerpts From Transcript of Trial, May 24, 1961 .... 25a

Plaintiffs’ Witnesses:

Herman L. Horn

Direct ...................................................... 28a

Cross ........................................................ 58a

Recalled—

Redirect ...................... 94a

Arthur G. Trout

Direct ...................................................... 60a

B. S. Hilton

Direct .................................................... - 64a

Ernest J. Oglesby

Direct ....................... 81a

Cross ........................................................ 89a

Redirect.................................................... 91a

11

PAGE

Exhibits Introduced at T ria l....................................... 99a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 6 to Deposition of Dr. Horn .. 99a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 6 ..................................... 100a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 8 to Deposition of Dr. Horn .. 108a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 4 ............................................... 111a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 5H to Deposition of Dr. Horn 112a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 7A ........................................... 113a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 7B ........................................... 114a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 7C ................................ 115a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 5 ............................................... 116a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 9 ............... 117a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 3 ............................................... 118a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1 (Horn) ............................... 120a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 4 (Horn) ............................... 121a

Memorandum Opinion, filed July 10,1961 .................. 122a

Judgment, Oct. 4, 1961 ................................................ 129a

Notice of Appeal, filed November 1, 1961.................. 131a

Relevant Docket Entries

1960

Aug. 31

Sept. 14

Sept. 16

Sept. 20

Sept. 23

1961

May 22

May 24

Filed Complaint, Motion for Interlocutory In

junction, and Plaintiff’s Statement of Points and

Authorities in Support of Motion for an Inter

locutory Injunction.

JJ. -u.*<V ~7C *Jk*

Filed Designation of District Judge for Service

in another District within his Circuit, signed by

Simon E. Sobeloff, Chief Judge, Fourth Circuit,

assigning and designating Oren R. Lewis, United

States District Court, Eastern District of Vir

ginia, to hold and hear case No. 1095 on such

date as he may determine.

Filed copy of minutes with exhibits taken in

Eastern District at hearing 9-15-60.

Filed Motion to Dismiss and Answer of Defen

dants, The County School Board of Roanoke

County and Herman L. Horn, Division Super

intendent of Schools, with certificate of service

noted thereon.

Received Answer of the Pupil Placement Board,

and marked same “proffered for filing” .

* * #

Filed depositions of Herman L. Horn, Arthur G.

Trout, and B. S. Hilton, taken on behalf of

plaintiffs. Same opened in open court and marked

“proffered for filing May 24, 1961, Leigh B.

Hanes, Jr., Clerk.

Filed Motion of plaintiffs to Amend and Correct

Caption of Complaint and Style of Case to read:

2a

Relevant Docket Entries

“ Gwendolyn Yvette Marsh, an infant by Ray

mond M. Iseley and Helen Iseley, her grand

father and grandmother and next friend.”

# * *

May 24 Trial by Court—summary order entered thereon.

(Plaintiffs’ exhibits filed.)

July 10 Filed Memorandum Opinion—copies certified to

counsel of record.

Oct. 4 Entered and filed order of judgment (civil order

book #18, page 45), sustaining defendants’ mo

tions to dismiss and dismissing complaint herein

at the plaintiffs’ costs—with objection of counsel

for plaintiffs noted. Copies certified to counsel

of record.

Nov. 1 Filed plaintiffs’ notice of appeal from final judg

ment entered October 4, 1961. * * *

# * #

3a

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F oe th e W estern D istrict of V irgin ia

R oanoke D ivision

Civil Action No. 1095

Complaint

G w endolyn Y vette I seley , an infant b y Raymond M . Iseley

and Helen Iseley, her grandfather and grandmother and

next friend,

J ean M illice n t F erguson and G regory M orris F erguson ,

infants by Jacqnelin Ferguson, their mother and next

friend,

J udy C arol W est , A lvin W est , J r ., L u la M arie W est and

B arbara L y n n W est, in fan ts b y A lv in W est , th eir fa th er

and next fr ien d ,

— and—

R aymond M. I seley , H elen I seley ,

J acquelin F erguson , A lvin W est,

Plaintiffs

T h e C o u n ty S chool B oard of R oanoke C o u n ty ,

a body corporate, Salem, Virginia

— and—

H erm an L. H orn , Division Superintendent,

Roanoke County Public Schools,

— and—

E. J. O glesby, E dward T . J u stis , and A lfred L . W ingo ,

in d iv id u a lly and con stitu tin g the P u pil P lacem en t

B oard of T h e C o m m o n w ealth of V irgin ia , R ic h m o n d ,

V irgin ia .

4a

1. (a) Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title

28, United States Code, Section 1331. This action arises

under Article 1, Section 8, and the Fourteenth Amendment

of the Constitution of the United States, Section 1, and

under the Act of Congress, Revised Statutes, Section 1977,

derived from the Act of May 31, 1870, Chapter 114, Sec

tion 16, 16 Stat. 144 (Title 42, United States Code, Section

1981), as hereafter more fully appears. The matter in

controversy, exclusive of interest and cost, exceeds the sum

of Ten Thousand Dollars ($10,000.00).

(b) Jurisdiction is further invoked under Title 28,

United States Code, Section 1343. This action is au

thorized by the Act of Congress, Revised Statutes, Sec

tion 1979, derived from the Act of April 20, 1871, Chapter

22, Section 1, 17 Stat. 13 (Title 42, United States Code,

Section 1983), to be commenced by any citizen of the

United States or other person within the jurisdiction

thereof to redress the deprivation under color of state law,

statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or usage of rights,

privileges and immunities secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States and

by the Act of Congress, Revised Statutes, Section 1977,

derived from the Act of May 31, 1870, Chapter 114, Sec

tion 16, 16 Stat. 144 (Title 42, United States Code, Section

1981), providing for the equal rights of citizens and of all

persons within the jurisdiction of the United States as

hereafter more fully appears.

2. Infant plaintiffs are Negroes, are citizens of the

United States and of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and

are residents of and domiciled in the County of Roanoke.

They are within the age limits of eligibility to attend the

public schools of the said County and possess all qualifica

Complaint

5a

tions and satisfy all requirements for admission to the

public schools of said County.

3. Adult plaintiffs are Negroes, are citizens of the

United States and of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and

are residents of and domiciled in the County of Roanoke.

They are parents or guardians of the infant plaintiffs,

and are taxpayers of the United States and of the said

Commonwealth and County. All adult plaintiffs having con

trol or charge of any unexempted child who has reached

his seventh birthday and has not passed his sixteenth

birthday are required to send said child to attend school

or to receive instruction (Code of Virginia, 1950, Title 22,

Chapter 12, Article 4, Sections 22-251 to 22-256).’

4. Plaintiffs bring this action in their own behalf and,

there being common questions of law and fact affecting

the rights of all other Negro children attending the public

schools of the County of Roanoke and their respective

parents and guardians, similarly situated and affected

with reference to the matters here involved, who are so

numerous as to make it impracticable to bring all before

the Court, and a common relief being sought, as will here

inafter more fully appear, being this action, pursuant to

Rule 23(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, as a

class action also on behalf of all other Negro children at

tending the public schools of the County of Roanoke and

their respective parents and guardians similarly situated

and affected with reference to the matters here involved.

5. Defendant The County School Board of The County

of Roanoke, Virginia, exists pursuant to the Constitution

and laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia as an adminis

Complaint

6a

trative department of the Commonwealth of Virginia, dis

charging governmental functions (Constitution of Virginia,

Article IX, Section 133, Code of Virginia, 1950, Title 22,

Chapter 1, Sections 22-1, 22-2, 22-5 to 22-9.3, Chapter 6,

Article 1, Sections 22-45 to 22-50, Chapter 6, Article 2,

Sections 22-59 to 22-79, Chapters 7 to 15, Sections 22-101

to 22-330); and is declared by law to be a body corporate

(Code of Virginia, 1950, Chapter 6, Article 2, Section

22-63).

6. Defendant Herman L. Horn is Division Superin

tendent of Schools for Roanoke County, Virginia. He

holds office pursuant to the Constitution and laws of the

Commonwealth of Virginia as administrative officer of the

public free school system of Virginia (Constitution of

Virginia, Article IX, Section 133; Code of Virginia, 1950,

Title 22, Chapter 1, Sections 22-1, 22-2, 22-5 to 22-9.3,

Chapter 4, Sections 22-31 to 22-40, Chapters 6 to 15, Sec.

tions 22-45 to 22-330). He is under the authority, super

vision and control of, and acts pursuant to, the orders,

policies, practices, customs and usages of defendant The

County School Board of the County of Roanoke. He is made

a defendant herein in his official capacity.

7. The Commonwealth of Virginia has declared public

education a state function. The Constitution of Virginia,

Article IX, Section 129, provides:

“ Free schools to be maintained. The General As

sembly shall establish and maintain an efficient system

of public free schools throughout the State.”

Pursuant to this mandate, the General Assembly of

Virginia has established a system of public free schools

Complaint

7a

in the Commonwealth of Virginia according to a plan

set out in Title 22, Chapters 1 to 15 inclusive, of the Code

of Virginia, 1950. The establishment, the maintenance and

administration of the public school system of Virginia is

vested in a State Board of Education, a Superintendent

of Public Instruction, Division Superintendent of Schools,

and County, City and Town School Boards (Constitution

of Virginia, Article IX, Sections 130-133; Code of Vir

ginia, 1950, Title 22, Chapter 1, Section 22-2).

8. On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court of the United

States declared the principle that State-imposed racial

segregation is violative of the Fourteenth Amendment of

the Constitution of the United States. Pursuant to said

decision, as recognized and applied by this Court, formal

applications have heretofore been made to defendants in

behalf of infant plaintiffs for admission, enrollment and

education in designated public free schools under the juris

diction and control of defendants, to which said infant

plaintiffs, but for the fact that they are Negroes, in all

other respects are qualified for admission and enrollment.

However, defendants and each of them, have failed and

refused to act, favorably upon these applications and pur

posefully, wilfully, and deliberately continue to pursue

and enforce the aforesaid policy, practice, custom and

usage of racial segregation against infant plaintiffs and

all other children similarly situated and affected.

9. Defendants will continue to pursue and enforce

against plaintiffs, and all other children similarly situated,

the policy, practice, custom and usage specified in Para

graph 8, supra, and will continue to deny to infant Negro

Plaintiffs admission, enrollment or education in any public

Complaint

8a

school under defendants’ supervision and control operated

for children who are not Negroes, unless restrained and

enjoined by this Court from so doing.

10. The public schools of the County of Roanoke, Vir

ginia are under the control and supervision of defendants

acting as administrative agencies of the Commonwealth

of Virginia. Defendant, The County School Board of the

County of Roanoke, Virginia, is empowered and required

to establish and maintain an efficient system of public free

schools in said County (Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended,

Sections 22-1, 22-5); to provide suitable and proper school

buildings, furniture and equipment, and to maintain, man

age and control the same (Code of Virginia, 1950, as

amended, Section 22-97); to determine the studies to be

pursued, the methods of teaching, and the government to

be employed in the schools (Code of Virginia, 1950, as

amended, Sections 22-97, 22-233 to 22-240.1); to employ

teachers (Code, 1950) to provide for the transportation

of pupils (Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended, Sections

22-276 to 22-277, 22-282 to 22-294) ; to enforce the school

laws (Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended, Section 22-97);

and to perform numerous other duties, activities and func

tions essential to the establishment, maintenance and op

eration of the schools of said County (Code of Virginia,

as amended, Sections 22-1 to 22-10, 22-30 to 22-44, 22-45

to 22-55, 22-57 to 22-58, 22-89 to 22-100, 22-101 to 22-166,

22-188.3 to 22-210, 22-212 to 22-246, 22-248 to 22-77, 22-279

to 22-330).

11. Defendants E. J. Oglesby, Edward T. Justis and

Alfred Wingo, constituting the Pupil Placement Board

of the Commonwealth of Virginia, purportedly are in

Complaint

9a

vested with all power of enrollment or placement of pupils

in, and determination of school attendance districts for,

the public schools in Virginia (Code of Virginia, 1950, as

amended, Section 22-232.1), and to perform the numerous

other duties, activities and functions pertaining to the

enrollment or placement of pupils in, and the determina

tion of school attendance districts for, the public schools

of Virginia (Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended, Sections

22-232.3 to 22-232.4).

12. Each school child who has heretofore attended a

public school and who has not moved from a county, city

or town in which he resided while attending such school

is required to attend the same school which he last at

tended until graduation therefrom unless enrolled in a

different school by the Pupil Placement Board (Code of

Virginia, 1950, as amended, Section 22-232.6). This pro

vision perpetuates the pre-existing requirement, policy,

practice, custom and usage of the Commonwealth of Vir

ginia of racial segregation in the public schools thereof

save as to such children as may be able, for good cause

shown, to establish an exception thereto by pursuing the

procedure specified in Sections 22-232.8 to 22-232.14.

13. Any child desiring to enter a public school for the

first time, and any child who is graduated from one school

to another within a school division or who transfers to

or within a school division, or any child who desires to

enter a public school after the ending of the session, is

required to apply to the Pupil Placement Board for en

rollment and is required to enroll in such school as the

Board deems proper (Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended,

Section 22-232.8), and if aggrieved thereby is required to

Complaint

10a

pursue the procedure specified by law (Code of Virginia

1950, as amended, Sections 22-232.8 to 22-232.14).

14. The procedure specified in Sections 22-232.8 to

22-232.14 is expensive prolix and inadequate to secure and

protect the rights of plaintiffs, and others similarly situ

ated, seeking relief from the imposition of segregation re

quirements, policies, practices, customs and usages based

on race or color.

15. Defendants endorse, maintain, operate and perpetu

ate separate public schools for Negro and white children,

respectively and deny infant plaintiffs and all other Negro

children because of their race or color, assignment, enroll

ment and admission to an education in any public school

operated for white children, and compel infant plaintiffs

and all other Negro children, because of their race or color,

to attend public schools set apart and operated exclusively

for Negro children, pursuant to a policy, practice, custom

and usage of segregating, on the basis of race or color, all

children attending the public schools of said County.

16. Timely application on behalf of each infant plain

tiff was made to defendants for admission for the 1960-61

school session to a public school in the County of Roanoke,

Virginia heretofore and now maintained for and attended

by white persons only, but defendants, acting pursuant to

a policy, practice, custom and usage of segregating school

children on the basis of race or color, denied the applica

tion of each on account of race or color.

16. (a) The defendant, Pupil Placement Board, acting

in concert with the defendants has refused to this date, to

Complaint

11a

take any action on the applications which effectively denies

pupils of their Constitutional rights,

17. The aforesaid action of defendants denies infant

plaintiffs and each of them, and others similarly situated,

their liberty without due process of law and the equal pro

tection of the laws secured by the Fourteenth Amendment

of the Constitution of the United States, Section 1, and

the rights secured by Title 42, United States Code, Section

1981.

18. Defendants will continue to pursue against plain

tiffs, and all other Negro children similarly situated, the

policy, practice, custom, and usage hereinbefore specified

and will continue to deny them assignment, admission, en

rollment or education to and in any public school operated

for children residing in said County who are not Negroes

unless plaintiffs are afforded the relief sought herein.

19. Plaintiffs and those similarly situated and affected

are suffering irreparable injury and are threatened with ir

reparable injury in the future by reason of the policy, prac

tice, custom and usage and the actions of the defendants

herein complained of.

W hereof , plaintiffs respectfully pray that, upon the

filing of this complaint, as may appear proper and con

venient to the Court:

(A) This Court enter judgment declaring that:

(1) The enforcement, operation or execution of Sec

tion 22-232.6, Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended, which

by its terms and in its operation perpetuates the pre

existing requirement, policy, practice, custom and

Complaint

12a

usage of the Commonwealth of Virginia of segregating,

on the basis of race or color, children attending the

public schools of the Commonwealth, deprives infant

plaintiffs of their rights to non-segregated education

secured by the Due Process and Equal Protection

Clauses of Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment of

the Constitution of the United States;

(2) The enforcement, operation or execution of Sec

tions 22-232.8 to 22-232.14, Code of Virginia, 1950, as

amended, which by their terms and in their operation

require incoming, graduating and transfering public

school children to pursue the procedure thereby

specified, deprives infant plaintiffs of their rights to

non-segregated education secured by the Due Process

and Equal Protection Clauses of S ection 1 of the Four

teenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United

States;

(3) The procedure prescribed by Sections 22-232.8 to

22-232.14, Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended, is in

adequate to secure and protect the rights of infant

plaintiffs to non-segregated education and need not

be pursued as a condition precedent to judicial relief

from the imposition of segregation requirements based

on race or color; and

(4) The action of defendants E. J. Oglesby, Edward T.

Justis, and Alfred L. Wingo, in administering and en

forcing the provisions of Sections 22-232.5 to 22-232.14,

Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended, so as to preserve,

perpetuate and effectuate the policy, practice, custom

and usage of assigning children, including infant

plaintiffs, to separate public schools on the basis of

their race or color, dejirives infant plaintiffs of their

Complaint

13a

liberty without due process of law and equal protection

of the laws secured by Section 1 of the Fourteenth

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States.

(B) This Court enter a temporary and permanent in

junction restraining and enjoining the defendant

County School Board of the County of Roanoke and

defendant Herman L. Horn, Division Superintendent

of Schools of the County of Roanoke, Virginia and each

of them, their successors in office, and their agents

and employees and all persons in active concert and

participation with them, forthwith, from any and all

action that regulates or affects, on the basis of race

or color, the admission, enrollment or education of the

infant plaintiffs, or any other Negro children similarly

situated, to and in any public school operated by the

defendants.

(C) In the event defendants request any delay in ef

fecting full and immediate compliance with Paragraphs

(a) and (b), supra, and for bringing about a transi

tion to a school system not operated on the basis of

race, direct defendants to present to this Court, within

ten (10) days a complete and comprehensive plan,

adopted by them which is designed to effect compliance

with Paragraphs (a) and (b), supra, at the earliest

practicable date; and which shall provide for a prompt

and reasonable start toward desegregation of the pub

lic schools under defendants’ jurisdiction and control

and a systematic and effective method for achieving

such desegregation with all deliberate speed; and that

following the filing of such plan with this Court, a fur

ther hearing will be held in this cause, at which time

defendants shall have the burden of establishing that

Complaint

14a

such delay as is requested is necessary in the public

interest and is consistent with good faith compliance

at the earliest practicable date.

(D) Allow plaintiffs their costs herein, and reasonable

attorney’s fee for their counsel, and grant such fur

ther, other, additional, or alternative relief as may

appear to the Court to be equitable and just in the

premises.

G w en d o lyn Y vette I seley ,

an infant by Raymond M. Iseley and

Helen Iseley, her grandfather and

grandmother and next friend,

J ean M illice n t F erguson and

Gregory M orris F erguson ,

infants by Jacquelin Ferguson,

their mother and next friend,

J udy Carol W est , A lv in W est, J r .,

L u la M arie W est and

B arbara L y n n W est ,

infants by Alvin West, their

father and next friend,

R aym ond M. I seley , H elen I seley,

J acquelin F erguson , A lvin W est

B y / s / R euben E . L aw son

Counsel for Plaintiffs

Reuben E. Lawson

19 Gilmer Avenue, Northwest

Roanoke, Virginia

Complaint

15a

Motion to Dismiss and Answer of Defendants, The

County School Board of Roanoke County and

Herman L. Horn, Division Superintendent

of Schools

[ c a pt io n o m it t e d ]

N o tice to D ism iss

These Defendants, The County School Board of Roanoke

County, Virginia, and Herman L. Horn, Division Superin

tendent of Schools for said County, jointly and severally,

move the Court to dismiss the Complaint filed in this case

on the following grounds:

(1) The Complaint fails to state a case upon which re

lief may be granted in that there are no allegations of

fact in said Complaint supporting the pleader’s conclusion

that the denial of the individual plaintiffs’ applications for

school assignment, transfer, enrollment and admission was

on account of their race or color.

(2) The individual plaintiffs have failed to comply with

the requirements of law as set forth in Chapter 12, Article

1.1 of the Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended, and the rules

and regulations of the Pupil Placement Board of the Com

monwealth of Virginia, adopted pursuant to the provisions

of said State Statute, relative to school assignment, trans

fer, enrollment and admission; especially have said in

dividual Plaintiffs failed to make proper, timely and legal

application for assignment, transfer, enrollment or admis

sion to any school in Roanoke County for the 1960-61 school

year, other than Carver School to which each of the infant

Plaintiffs has been properly, timely and legally assigned,

enrolled and admitted for said school year.

16a

(3) If the individual Plaintiffs considered themselves ag

grieved by any action taken by said Pupil Placement Board

on their applications for assignment, transfer, enrollment

and admission from Carver School to Clearbrook School

for the 1960-61 school year they should have taken the steps

set forth in said State Statute for administrative relief of

such action. This they have failed to do. Their right to

so do still exists. The procedure and remedies provided by

said State Law (Chapter 12, Article 1.1 of the Code of

Virginia, 1950, as amended) are fully adequate for deter

mination and adjudication of Plaintiffs’ rights, and the

Plaintiffs should be required to follow the procedure set

forth in said State Law for administrative relief, unless

and until it becomes apparent that such procedure and

remedies therein provided are adequate to protect Plain

tiffs Constitutional rights.

A n sw er

Without waiving their Motion to Dismiss, these Defen

dants, The County School Board of Roanoke County,

Virginia, and Herman L. Horn, Division Superintendent

of Schools of Roanoke County, jointly and severally, an

swer said Complaint with specific reference to the num

bered paragraphs thereof as follows:

1. The allegations of Paragraph l.(a ) and l.(b) are

denied.

2. These Defendants are without knowledge as to the

truth of the allegations of Paragraph 2 and call for proof

thereof.

Motion to Dismiss and Answer of Defendants

County School Board and Herman L. Horn

17a

3. These Defendants are without knowledge as to the

truth of the allegations of Paragraph 3 and call for proof

thereof.

4. The allegations of Paragraph 4 are denied.

5. Paragraph 5 containing only constitutional and statu

tory citations and legal conclusions, no answer is made

thereto.

6. Except that these Defendants admit that Herman L.

Horn is Division Superintendent of Schools for Roanoke

County, Virginia, the remainder of Paragraph 6 contain

ing only constitutional and statutory citations and legal

conclusions, no answer is made thereto.

7. Paragraph 7 containing only constitutional and statu

tory citations and legal conclusions, no answer is made

thereto.

8. Applications for transfer of infant Plaintiffs from

Carver School, to which each infant Plaintiff had been

legally assigned, to Clearbrook School, for the 1960-61

school year were received by Defendant, Herman L. Horn,

Division Superintendent of Schools of Roanoke County,

on July 16,1960, and by him presented to the County School

Board at its next regular meeting on August 9, 1960, and

thence forwarded by said School Board to the Virginia

Pupil Placement Board, all as provided by law. At the

times alleged in the Complaint and at the present time the

Plaintiffs have failed to take those steps before the Virginia

Pupil Placement Board required by law for a final deter

mination of their applications, and especially have said

Motion to Dismiss and Answer of Defendants

County School Board and Herman L. Horn

18a

Plaintiffs further failed to follow the procedure for ad

ministrative relief of any action taken by said Pupil Place

ment Board if they are aggrieved thereby, as they are re

quired by law to so do. All allegations of Paragraph 8 not

herein referred to are denied.

9. The allegations of Paragraph 9 are denied.

10. Paragraph 10 containing only statutory citations and

legal conclusions, no answer is made thereto.

11. These Defendants admit that E. J. Oglesby, Elwood

T. Justis and Alfred L. Wingo are members of the Pupil

Placement Board of the Commonwealth of Virginia. The

remainder of Paragraph 11 containing only statutory cita

tions and legal conclusions, no answer is made thereto.

12. The allegations of the first sentence of Paragraph

12 are admitted. The allegations of the second sentence of

such paragraph are denied.

13. The allegations of Paragraph 13 are admitted.

14. The allegations of Paragraph 14 are denied.

15. The allegations of Paragraph 15 are denied.

16. The allegations of Paragraph 16 are denied.

16(a). The allegations of Paragraph 16(a) are denied.

17. The allegations of Paragraph 17 are denied.

18. The allegations of Paragraph 18 are denied.

Motion to Dismiss and Answer of Defendants

County School Board and Herman L. Horn

19a

19. The allegations of Paragraph 19 are denied.

A nd doe F txktheb A n sw eb to th e C o m plain t filed against

them, these Defendants, jointly and severally, further an

swer and say:

A. That for a period of many years prior to the filing

of the applications for transfer of infant Plaintiffs from

Carver School to Clearbrook School the County School

Board of Roanoke County had devoted itself to a concerted

policy and effort of maintaining good race relationships

in the Public School System of the County, and, pursuant to

that policy and effort, had desegregated school teachers

meetings and other school functions and activities. Prior

to the filing of the applications for transfer of infant plain

tiffs from Carver School to Clearbrook School no applica

tion had theretofore been submitted to said School Board by

any negro pupil requesting admission to any school pre

dominantly attended by white children.

B. At no time has the County School Board of Roanoke

County or the Division Superintendent of Schools of

Roanoke County adopted a policy by resolution or other

wise requiring the continued segregation of the races in

the Public Schools of Roanoke County.

C. That The County School Board of Roanoke County

is now engaged in a general County wide school improve

ment and construction program, which program specifically

includes the construction of a new school for Elementary

children to be erected in the immediate neighborhood in

which the Plaintiffs reside, which new school will be con

structed and available for occupancy by pupils at the be

ginning of the 1961-62 school year, to which new school

Motion to Dismiss and Answer of Defendants

County School Board and Herman L. Horn

20a

each infant plaintiff will definitely be assigned and trans

ferred for said 1961-62 school year.

D. That all legal power and authority of assignment,

transfer, enrollment and admission of pupils in the public

schools of Roanoke County is vested in the Defendant,

Virginia Pupil Placement Board, and any relief sought

by individual plaintiffs should be directed only against

that Defendant and not against these Defendants.

Respectfully submitted this 20th day of September, 1960.

T h e Co u n ty S chool B oard

o r R oanoke Co u n t y , V irgin ia

and

H erm an L. H orn ,

Division Superintendent of Schools

of Roanoke County,

By /s / B e n j . E. Ch a pm a n

Benj. E. Chapman, Their Counsel.

Motion to Dismiss and Answer of Defendants

County School Board and Herman L. Horn

Benj. E. Chapman,

Counsel for these Defendants,

216% E. Main Street,

Salem, Virginia.

[ CERTIFICATE OMITTED]

21a

[ c a p t io n o m it t e d ]

For their joint and several answer to the Complaint in

these proceedings, in so far as advised material and proper,

the defendants E. J. Oglesby, Edward T. Justis and Alfred

L. Wingo say:

1— Strict proof of all of the allegations of paragraphs

1, 2, 3 and 4 of the Complaint is called for.

2— That Herman L. Horn is Division Superintendent of

Schools for the County of Roanoke, Virginia, and that these

defendants constitute the Pupil Placement Board of the

Commonwealth of Virginia, is admitted.

3— All of the other allegations of the Complaint are

denied or constitute a recital of laws and legal conclusions

as to which no answer is required.

F u rth er A n sw e r in g :

4— These defendants denied the specific request of the

plaintiffs for enrollment in or transfer to Clearbrook School

and continued their enrollment in Carver School purely

in strict accordance with the Rule and Regulation of the

Pupil Placement Board requiring the submission of such

a request sixty (60) days prior to the commencement of

any school session. At the same time the plaintiffs were

expressly advised that such action was without prejudice

to their right to make new application at least sixty (60)

days prior to the opening date of the 1961-1962 school

session if they desire to do so.

5— Another Rule and Regulation of the Pupil Placement

Board, also generally applicable in all cases and duly

Answer of tlie Pupil Placement Board

22a

adopted without regard to race, color or creed, is to the

effect that no pupil shall be transferred from one school

to another in the absence of a favorable recommendation

by local school officials, such rule also resting upon the

necessity for attaining, as between these defendants and

the local school officials, orderly administrative proceedings

in the operation of the public schools. There has been no

such recommendation in the ease of any of the plaintiffs.

6— These defendants deny that they have enrolled or

placed any of the plaintiffs in, or denied requested transfer

to, public schools on the sole ground of race or color in

contravention of any constitutional rights. These defen

dants aver, on the contrary, that they have attempted to

enroll each pupil so as to provide for the orderly adminis

tration of public schools, the competent instruction of the

pupils enrolled and the health, safety and general welfare

of such pupils, in strict accordance with law governing

and controlling their actions.

7— They further aver that they are under no obligation

or compunction to promote or to accelerate the mixing of

the races in the public schools; that no court is constitu

tionally empowered to direct the mixing of the races in the

public schools; that no negro child or white child or child

of any other race has the right to attend a specific school

merely because he is negro or white of a member of any

other race; that in the placing of over 500,000 pupils in

the public schools of the Commonwealth of Virginia, an

infinitesimal number of complaints has been made to this

Board by any person on the ground of racial discrimina

tion; that voluntary segregation of the races is lawful and

Answer of Pupil Placement Board

23a

the normal wish of the parents and children of the over

whelming majorities of both the negro and white races is,

in general, in accord with the welfare of the children of each

race, is not the proper concern of any court, and that until

appealed to in a specific case, this Board should not as

sume the contrary.

8—F u rth er A n sw erin g , that it is also provided by law

that any party aggrieved by a decision of the Pupil Place

ment Board may file with it a protest, pursuant to which

the Board shall conduct a hearing, consider and decide each

case separately on its merits, which decision enrolling such

pupil in the school originally designated or in such other

school as shall be deemed proper, shall set forth the find

ing upon which such decision is based. That the burden

of proving discrimination in the placement of pupils on

the sole ground of race or color rests upon the one alleg

ing discrimination; that the welfare of each child, regard

less of race or color, is a factual question to be considered

and decided by this Board after complaint is made, hear

ing held and full evidence concerning all surrounding cir

cumstances is made available; and that until such proce

dure is pursued no person should be in a position to chal

lenge the action of this Board on the ground that it has

discriminated on the sole ground of race or color. That

notwithstanding ability, readiness and willingness to af

ford a prompt and full hearing in accordance with law as

to any specific complaint or grievance, none of the plaintiffs

has filed any protest with the Pupil Placement Board or

any of these defendants with respect to any action taken

by it or them.

Answer of Pupil Placement Board

24a

W herefore , the p la in tiffs sh ou ld be den ied re lie f on the

p en d in g com pla in t and the sam e sh ou ld be d ism issed .

Answer of Pupil Placement Board

A . B. S cott

E . J . O glesby

E dward T . J ustis

A lfred L . W ingo

Constituting the Members of the

Pupil Placement Board of the

Commonwealth of Virginia

By Counsel

A. B. Scott, of

Christian, Marks, Scott & Spicer,

Counsel for Pupil Placement Board

1309 State-Planters Building

Richmond 19, Virginia.

^CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE OMITTED]

25a

—2—

Excerpts From Transcript of Trial, May 24, 1961

* # # * #

Mr. Lawson: Yes, sir. May it please the Court, I would

like to file the motion to amend the complaint, correcting

the name of the first-named Plaintiff from that of Gwen

dolyn Yvette Iseley to that of Gwendolyn Yvette Marsh

and by Emmy and Henry, her grandfather and grand

mother and next friend.

The Court: Is there any objection to that!

Mr. Chapman: No objection, Your Honor.

The Court: Let the motion be granted.

—3—

Mr. Lawson: May it please the Court, I should also

like to move the Court that stipulations in paragraphs 2

and 3 be admitted; namely, that infant Plaintiffs are Ne

groes, are citizens of the United States and of the Com

monwealth of Virginia and are residents and domiciled in

the County of Eoanoke; that they are within the age limit

of eligibility to attend the public schools of the said County

and possess all qualifications and satisfy all requirements

for admission to the public schools of said County. Fur

ther, that adult Plaintiffs are Negroes, are citizens of the

United States and the Commonwealth of Virginia and are

residents and domiciled in the County of Eoanoke; that

they are parents or guardians of the infant Plaintiffs and

are taxpayers of the United States and of the said Com

monwealth and County.

The Court: Now I will ask if they agree to that stipula

tion which is, technically, slightly different than what we

took up in chambers. The only difference is that you are

asking them to stipulate that they possess all of the quali

fications and requirements for admission to the schools.

I am sure that they will agree to the stipulation that they

26a

Motions

are residents of the County of Roanoke and that they are

members of the Negro race.

Mr. Lawson: They are attending the schools in the

—4—-

County.

The Court: And that they are attending the schools in

the County.

Mr. Lawson: As of now; yes, sir.

The Court: Without asking them to stipulate that they

have all of the qualifications and requirements; is that

correct?

Mr. Lawson: That is correct.

The Court: Stipulation so granted and made part of

the record in this case.

Mr. Lawson: Tour Honor, I should also like to move

the Court that all exhibits be admitted without formal

proof.

The Court: Exhibits that we exchanged in chambers

between Counsel for all parties will be admitted without

formal proof subject, however, to either side, when they

are entered individually, objecting on the ground of rele

vancy if they are so advised.

Mr. Chapman: That is my understanding.

Mr. Lawson: If Your Honor please, I should also move

the Court to admit the depositions of witnesses B. S. Hilton,

Herman L. Horn and Arthur G. Trout under Rule 26.

The Court: On what ground?

Mr. Lawson: On the ground, sir, that these are the

depositions of parties to the cause and, therefore, he an

—5—

exception under the other rules.

The Court: Are these witnesses available and have been

subpoenaed?

27a

Motions

Mr. Lawson: Yes, sir. They are here and we intend to

call them.

The Court: And the depositions are the depositions

taken prior to the hearing of this case under what is

commonly referred to as the discovery process in Federal

procedure ?

Mr. Lawson: Yes, sir.

The Court: The purpose is to entitle each side to ex

amine witnesses to determine in advance of trial what

they do or do not know. And they are generally not taken

for the purpose of introducing them in evidence in sub

stitution for the testimony of those witnesses in open

court. The purpose of the rule is that it is always an ad

vantage to the Court and the jury, if a jury is impanelled,

to see and hear the witnesses so that they may determine

their credibility based upon their actions on the stand and

everything instance thereto. The motion is denied.

Mr. Lawson: If Your Honor please, we would like to

state for the record that the purpose was to supplement

live testimony. We thought, under the rule, it was perfectly

proper.

— 6—

The Court: The motion is denied.

Mr. Scott: In dealing with the parties to the suit, in

order that the record and Your Honor may have it straight,

one of those witnesses, B. S. Hilton, while Executive Secre

tary of the Pupil Placement Board, is not a former party

to the suit and I wrnuld like to straighten that out.

The Court: That is all right. It doesn’t make any dif

ference to this Court "whether they are former or other

parties. The motion is denied as to all depositions, if they

are available in court and will testify in court.

# # # # #

28a

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs Direct

—7—

* * * * *

P l a in t if f s ’ E v id e n c e

H e r m a n L. H o r n , called as a witness for the Plaintiffs,

having been dnly sworn, testified as follows.

Direct Examination by Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Will you state your full name and your position

with the County School Board? A. Herman L. Horn. I

am Superintendent of the Roanoke County Schools.

Q. How long have you held that position, sir? A. Six

years.

Q Hid you have a previous position in the County School

— 8—

system? A. Yes, sir. I was principal of the William Burt

High School in 1930 to 1940. I was Director of Instruc

tion of Roanoke County Schools from 1940 to ’42,

Q. You are one of the parties, defendant, in this case?

A. Yes, sir.

Mr. Nabrit: Your Honor, we request permission

to examine the witness further as an adverse party.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. I would like to obtain general facts about your

school system. Would you tell me, first, how many ele

mentary schools you have in the County? A. We have

23 schools that are purely elementary. And then we have—

Q. How many high schools? A. Five high schools. One

of those is combined—one through twelve. And we have

29a

two other high schools that have the seventh grade through

the twelfth.

Q. How many of the elementary schools serve only

Negro pupils and what are their names! A. There are

two elementary schools in which, presently, only Negro

children attend—Harlond and Gregg* Avenue.

Q. There is a high school which serves only Negro pupils!

—9—

A. Carver High School serves only Negroes and serves

elementary and high school. It is combined—grades one

through twelve.

Q. Are there other schools in the system attended only

by white pupils! A. Yes, sir.

Q. Is this true with respect to the staffs and teachers

and principals at these various schools: in the white

schools they are all white teachers and in the Negro, the

principals and teachers— A. Yes, sir.

Q. Staff and so forth! A. Well, the County Staff has

one Negro coordinator.

Q. I was speaking of the staff at the schools. A. Yes,

sir.

Q. Who is this last person you mentioned! A. We have

a Negro coordinator of elementary education.

Q. He is assigned to a particular school! A. He serves

all of the three elementary schools—Carver, Harlond and

Cregg Avenue.

Q. He coordinates the three Negro elementary schools!

A. Yes, sir.

Mr. Nabrit: Now, at this time, Your Honor, I

would like to introduce or offer Plaintiffs’ Exhibits

1 and 2, previously discussed in the stipulation.

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs—Direct

30a

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs—Direct

— 10—

The Court: Counsel for the Defendant have any

objection?

Mr. Chapman: May I see them, Tour Honor?

The Court: Yes. Show them to Counsel.

Mr. Chapman: No objection, Tour Honor.

The Court: They may be admitted as Plaintiffs’

Exhibits 1 and 2.

Mr. Nabrit: Your Honor, if I may state briefly

what they are. Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1 is a tape listing

the names of the schools in the County and the

grades they serve and the capacity of the various

schools.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2 is a map of the County which,

unfortunately, is on a rather small scale. Marked

on the map by the school authorities are schools’

zone lines. And there may be some other markings

on there which I cannot see.

The Court: All right.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Doctor Horn, approximately how many pupils do

you have in your County School system? A. Total en

rollment runs something over 14,000 at the present.

Q. And about how many of these pupils are Negroes?

A. There are about—total enrollment—950.

— 11—

Q. 950? A. Out of the 14,000, yes, sir.

Q. Out of 1400? A. 14,000. I am sorry; 14,000.

Q. So, less than one out of 14 students in the County

is Negro—one out of 14 or slightly less? A. Well, three

out of 28—would be about one out of every nine. I ’d say

31a

one out of about every nine are Negroes. See, we have

there three Negroes and 28 schools.

Q. No, no. I was not talking about schools. I was talk

ing about pupil ratio to Negroes.

The Court: Isn’t that a mathematical calculation?

I can figure that out.

Mr. Nabrit: Very well, sir.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Now, about how many teachers do you have—white

and Negro—and supervisors and so forth? A. We have,

1 believe, 535 teachers and 37 of them, I believe, are in

the schools attended by Negroes.

Q. Now, will you describe to the Court what the schools’

zoning situation is, what that Exhibit No. 2 indicates? A.

Well, in Roanoke County the population is growing rapidly,

and we, of course, are constantly building school build

ings, and we zone the areas to try to divide the children

among the schools where we have space.

Q. Do you have a zone for each school? A. Yes. We

- 12-

set up each year a zone for each school for—well, I ’d say

each year. Of course, some of them continue year after

year in areas where the population is not growing. But

in some of the areas where the population is growing

rapidly, we build new schools and we have to change the

lines as we build new schools to provide new space, to

shift children from one school to the other, to take care

of our crowded conditions. Our schools are crowded in

our area here.

Q. Well, is it generally true that the students are as

signed to schools in accordance to the zones that are set

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs-—Direct

32a

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs—Direct

up and that are indicated on that map? A. Those zones

represent the areas that were assigned the schools for this

present school year—1960-61.

Q. And the children are assigned in accordance with

those zones? A. Yes.

Q. Are there exceptions to that? A. Oh, there may be

a few occasions where there may be exceptions because

of health conditions of the child. The parents in some

instances—the children are transferred from a school to

a school that is some distance away. I think probably in

the case of one or two where the parents have taken the

child from school where the child has been ill.

Q. Except for this type of individual exception, the

C€>W . . .students are assigned m accordance with these zones? A.

Yes, the zones for this present year.

Q. Now, is it true that the zones for the three Negro

schools in the County are separate zones in the sense that

they overlap zones established for white schools? A. Yes.

The three Negroes’ serve the entire County. The zones

overlap.

Q. You have one Negro high school and four white high

schools? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now, do the four white high schools have separate

geographic areas that they serve in the County? A. Yes.

Q. And the Negro high school—Carver—serves Negroes

living everywhere? A. Yes.

Q. And for the elementary schools, the same type of

thing would he true; that is, the Negro school zones es

tablished on the map overlap the white schools? A. Yes,

sir. They do.

Q. Do you recall Exhibit 2? Do you recall correctly that

it shows the Negro school zones in crayon in one color

V

33a

and the white schools in another color? A. I believe it

does. But I believe they are on different colors. i

—14—

Q. Now, I believe you indicated that you became Super

intendent back in 1956? A. 1955.

Q. 1955? A. This is my sixth year.

Q. Was this type of zoning system in use when you

became Superintendent? A. Yes.

Q. The same type of map? A. Yes. The zones have

been changed as the community has grown.

Q. Same pattern? A. And the school serves a certain

area.

Q. How far does that go back in your experience in the

County—that system? A. I frankly do not recall. I was

here in 1930—’42—I believe there were different areas

that each school served. But it was not—I don’t know

whether they were definite—any rigid regulations or not

—concerning the zoning, the school zones at that time.

Q. You were away from the County between ’42 and

’55? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Are you able to tell, when you came here in 1955,

that this was the existing system? A. Was I able to tell?

I am not sure that I understand your question.

—15—

Q. When you came here to the County in 1955, did you

find this system in use when you got here? A. Yes.

Q. Now, are your three Negro schools located in the

principal centers of Negro population in the County or

are there considerable groups of Negroes living in other

areas? A. Well, there are several instances of reason

able size groups living in other areas.

Q. So, that there are Negro pupils who are in the County

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs—Direct

34a

in some numbers that are not located in the neighborhood

where these three schools are? A. Yes, there are.

Q. Now, has your School Board or have you or any of

your assistants ever made any announcements to the public

or to parents or teachers or pupils to indicate to them that

racial segregation was no longer required in your County

School system? A. Would you repeat your question,

please?

Q. Yes. My question was whether you have made any

announcements—

Mr. Chapman: I would like to—

Mr. Nabrit: Let me finish the question.

The Court: Go ahead and repeat the question.

— 16—

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. My question is : whether you—when I say you, I mean

you and your Board and your Staff—have ever issued

any announcements to the public to let the public know

that racial segregation was not going to be a require

ment in the County in the future there from that time? Had

you made any such announcement to the County?

Mr. Chapman: We object to that question. Any

answer to it would be irrelevant. The School Super

intendent and the School Board is not charged with

any duty of making any such announcement.

The Court: Your point is well taken. I don’t

know if they are charged. Will you limit your an

swer to any official act on your part, as Superin

tendent of the Schools, and any official act that you

know of covered by the minutes of the corporate

body known as the School Board?

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs—Direct

35a

Mr. Nabrit: I so limit my question, Your Honor.

The Court: As stated from what you might or

might not know.

A. The answer is no. There has been no announcement

from me as an official or by the School Board.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. The Board. I take it that yoiir answer includes that

—17—

there has been no desegregation plan or anything like

that announced officially by the Board or by you, by the

official office?

The Court: I didn’t get the question.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. No plan or plans for desegregation or ending segre

gation announced? A. No.

Q. By the previous question, I mean plans relating to

ending segregation. A. That is the way I understood your

question, sir.

Q. Would you corroborate the fact that there has been

no actual desegregation of schools in the County? By that

I mean there has been no case where Negroes and white

children attended school together? A. No, they have not

attended school together.

Q. That is true as far as teachers are concerned; that

teachers are also segregated: Negro teachers only for

Negro students; white teachers only for white pupils? A.

That is true.

Q. Now, what normally happens when a first-grade child

is to enter school? Do you have a Spring enrollment pro-

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs—-Direct

36a

gram? What does a parent do to get his child into school

when he is entering the first grade? A. We have prelimi-

—18—

nary enrollment day or days in each school in Roanoke

County, usually by the first of April, sometime latter

part of March, where announcements are usually made in

the newspapers. The parents are requested to bring their

children to the school to enroll them for the coming ses

sion.

Q. Is this a fair summary of what they do when they

get there: They show proof of the child’s age. They fill

out a State Pupil Placement Form. Is that part of the

procedure at that time? A. Yes, sir.

Q. What else goes on, anything else? A. Well, they

usually explain to the parents the procedure for the first

day of school and the children are usually shown the room

that they were probably assigned to—generally an orienta

tion period for the children and the parents.

Q. Now, how does the parent find out if he doesn’t know

what school to take his child for this? Is it announced in

the neighborhood or in the newspapers or what? A. Well,

usually, if the existing lines of the previous year are

not changed, why, parents are usually aware of the school

to which the children are to go in. If there are any change

in the lines of the school, we usually publish those in the

newspapers and announce to the children, to those who

—1 9 -

are in school, and, of course, people move into communi

ties who haven’t been there before, why, they probably

call the school or my office to inquire where they should

go for the preliminary enrollment.

Q. And when these people make telephone inquiries, to

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs—Direct

37a

find out where to go, they are advised in terms of the

zones to go to school in their zones? A, That is right.

Q. Now, what percentage, if you know, of your children

go to attend these preliminary enrollments? A. The num

ber will vary in the different schools, but it probably runs

90 per cent.

Q. 90 per cent. Do you have approximately 10 per cent

of the children enrolled or indicate that they wmnt to

enroll at a later time? A. Well, they enroll continually

from the preliminary day on up. Some people move into

the community just a few days before the school but,

usually, they—

Q. Even after the school starts, people move in and

are enrolled? A. Yes.

Q. Routinely correct? A. Yes. They move in and they

are enrolled.

Q. Now, when a parent fills out the State Pupil Place-

— 20—

ment form—he fills it out at the school, I think you in

dicated. Now, what happens to the form then? There is

a recommendation made or what? A. The form comes to

my office. The principal or teacher will check to see that

it is filled out correctly. The form comes to my office and

some of my staff will go over all of these forms, verify

and check to see if they are correct, and place on the form

the school which the child is recommended for admission.

And then they are forwarded to the Pupil Placement Board

in Richmond.

Q. Now, I take it that your recommendations, from what

you tell me, are in general accordance with your zones?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And, now, I take it also, from the facts, that most

of the students are assigned in consistent with the zones;

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiff s—Direct

38a

that the Pupil Placement Board approves these recom

mendations routinely! A. I assume that they do.

Q. How long has your system been functioning under

the Pupil Placement Board! A. From the beginning of

the Pupil Placement Board, I am not sure of the date.

Q. From 1956, ’57, something like that! A. I don’t

know the date the Pupil Placement Board was—

— 21—

Q. Is it your impression that it is three or four years,

several years! A. Yes, several years.

Q. Now, during that period has the Pupil Placement

Board ever rejected one of your recommendations for the

assignment of a pupil or have they accepted all of them!

A. I don’t know whether they all have been accepted or

not. There may have been some rejections. I don’t recall

of any instances right now. But, of course, there are thou

sands of placement forms. I do not recall at present of

any rejections.

Q. So, it is your recollection that the Board has uni

formly accepted your recommendations. That is your best

recollection!

Mr. Chapman: I object to that question on the

ground to get the witness to say what the Pupil

Placement Board policy is.

The Court: Objection sustained. The Pupil

Placement Board is the best evidence of that. You

are not a member of the Board. You were not a

member were you!

A. No, sir.

The Court: Objection sustained.

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs—Direct

39a

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs—Direct

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Do you have much moving of pupils within the

County or any degree of that? A. Yes. There is some

moving.

— 22—

Q. What happens when a child moves from one area,

from one zone, shall we say, to another school zone? Is

he transferred immediately or later or what happens? A.

Well, when the parents move, they have to file an applica

tion blank for transfer. But, usually, when a child’s parents

move within the County, if it is possible for the child to

continue in that school for the remaining part of the year,

we prefer that he remain in that school rather than move

to another school. I believe that in the great majority of

the cases, why, the children remain through the school

session and transfer during the summer. Of course, if

there is a move, they fill out an application blank for trans

fer to another school.

Q. And subsequently they are transferred? A. Yes.

Q. Now, do you have any specialized high schools or are

they all general schools? A. All of the high schools in

Boanoke County—what is termed in Virginia—are com

prehensive high schools.

Q. Would it be true that you have no high schools set

aside for any pupils with special qualifications, different

from the qualifications of the other high schools? I mean,

do you have, for example, a trade school or vocational

school, economic school? A. No.

—23—

Q. None of that. You don’t have any school for smarter

students or average students? A. No, sir.

Q. Or slower students? You don’t have anything like

that? A. No, sir.

40a

Q. Do you have any appropriate program of grouping

by ability in the school! I don’t mean the grade. I mean

the— A. According to ability?

Q. Within grades. A. A few of our schools usually have

ability grouping, elementary school. But it is not a County

wide practice.

Q. This is left to the principal? A. The principal and

the teachers.

Q. Now, will this discussion also apply to elementary

schools? There are no specialized schools in the County?

A. No specialized schools.

Q. They take all of the people living in the zones, who

ever that happens to be; is that correct? A. In the zones;

yes, sir, if they are in the age limit.

Q. So, the basic qualification to get into a school is that

you live in a zone and that you be in the proper grade

and you have to be promoted to whatever grade you are

" —24—

trying to get into; is that correct? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now, do you recall that these Plaintiffs applied to

enter previously all-white schools or presently all-white

schools last summer—the summer of 1960? A. I think I

recall; yes, sir.

# # # * *

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs—Direct

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Before I present this, can you tell the Court what

happened when these pupils applied, what form the events

took? Did you get a letter of petition? A. Well, the ap

plications with seven children were delivered to my office.

The Court: How many children?

41a

A. Seven; on Saturday, July the 16th, with a letter ad

dressed to me and the School Board. I presented the seven

applications to the School Board at its next regular session

which was the first of August. In accordance with the

State law, they were forwarded then to the Pupil Place

ment Board in Eichmond.

—25—

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. What, if anything, occurred when you presented these

applications to your local Board! Did they take any ac

tion on them! A. The only action the Board took was to

send them to the Pupil Placement Board. Of course, they

were addressed to the Pupil Placement Board.

Q. These are the Pupil Placement forms you mean! A.

Yes.

Q. This was a letter to you, was it not, from Counsel for

these students, Mr. Lawson, enclosing the applications. Do

you have that with you! A. I think it was addressed to

me and the School Board.

Q. Do you have that with you! A. I am not sure whether

I have or not.

Mr. Nabrit: May it please the Court, I don’t

know whether this is one of the exhibits.

The Court: You ask him if he has the letter and

he will answer it. Let him look through there.

Mr. Chapman: It is one of the exhibits, Your

Honor.

The Court: I am not sure that wasn’t the letter

that was introduced on the preliminary motion. You

referred to it.

—26—

The Witness: I have a copy—a photostatic copy

of the letter.

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs—Direct

42a

The Court: There were some letters or exhibits

used on that preliminary motion.

The Witness: Here it is.

The Court: He has it there.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Did something else accompany this? What were the

enclosures with this letter? A. The seven applications and

the—

Q. There is a petition. A. And a petition to the Board.

The Court: They may have taken them out. My

recollection is that they had some of these forms at

the preliminary motion.

Mr. Scott: That is my recollection.

Mr. Chapman: Yes.

* * # * *

—27—

* * * * *

Mr. Nabrit: Your Honor, all of the documents

that we suppose to have introduced seem to be in

this group already in.

The Court: Let me have them. I assume they are

marked.

Mr. Nabrit: Should those be remarked or re

numbered, as a matter of mechanics? What is your

pleasure ?

The Court: They are already marked. They are

identified sufficiently.

The Court will consider these exhibits as part of

the record in this case.

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs—Direct

43a

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs—Direct

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Mr. Horn, did yonr County School Board take any

action, formal action, on the petition that came with the

applications of these pupils? A. I think that a copy of the

minutes of the School Board action is in the record. I think

that will speak for itself.

Q. Did you make any recommendations on these with

respect to these seven pupils when you sent them along

to the Pupil Placement Board? A. Yes, sir, I did.

—28—

Q. Did you recommend that their requests be denied?

A. I recommended that they attend Carver School.

Q. Carver School being the all-Negro school that six of

them were already attending previously? A. Yes, sir.

Q. And the seventh child was a beginner; is that cor

rect? A. That is correct.

Q. Did you state any reasons for your recommendations

or communicate them in any way to the Pupil Placement

Board when you forwarded— A. No.

Q. You did not? A. No.

Q. What did the Pupil Placement Board inform you

about their action? Did the Pupil Placement Board subse

quently tell you that these applications should be denied or

were denied? A. I received a letter, the letter saying that

—I think a copy of the letter is in the record. Let’s see if

I have a copy of it.

Q. Well, perhaps we can save time by introducing this

in exhibit form, Doctor Horn.

Mr. Nabrit: Your Honor, I would offer Plaintiffs’

Exhibit 5 to the deposition of Doctor Horn.

The Court: Show it to Mr. Chapman.

44a

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs—Direct

—29—

J{. -Sfe St; -5fc SkW W W w IP

The Court: Let it be admitted.

Mr. Nabrit: Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 5 to the depo

sition of Doctor Horn.

I also offer, Your Honor, Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No.

8 to Doctor Horn’s deposition which was an extract

from the minutes of the meeting of the County

School Board of Eoanoke County held on August 4,

1960.

Mr. Chapman: Let me see it, please.

Mr. Nabrit: This is the document that was re

ferred to.

Mr. Chapman: No objection.

—30—

The Court: Let it be admitted.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Can you tell the Court the substance of the answer

that you got back from the Pupil Placement Board on this

application?

The Court: Is the answer available ?

Mr. Nabrit: Yes, sir; one of the documents that

I just introduced.

The Court: It is already in the record. No need

for him to tell the subject of it. I will read it myself.

Mr. Nabrit: Very well, sir.

The Court: In other words, there is no secret

about the fact that the Pupil Placement Board re

fused to consider these applications because they

contend they were not filed within the period required

45a

by the rules of the Pupil Placement Board; isn’t

that right ?

Mr. Nabrit: That is our understanding, sir.

The Court: I don’t think there is any dispute

about that fact.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Doctor Horn, with respect to this 60-day rule, if we

may call it that, this is a rule adopted by your local Board

or the Pupil Placement Board? A. 60-day rule?

—31—

Q. That is correct. A. It is a Pupil Placement—adopted

by the Pupil Placement Board.

Q. Does your local Board have any or did it at that

time have any similar rule or anything like that, adopted

locally as to when the time limit of the pupil is to apply

to enter school the next year?

The Court: What difference does that make

whether they did or not if they are under the Pupil

Placement Board? He can answer the question. But

what difference does it make whether the local Board

had a different rule, if they are bound. And, of

course, that is one of the questions before the Court.

If they are bound by the Pupil Placement Board and

they make all of the rules they want, it wouldn’t

have any bearing on it if the Pupil Placement Board

is the legal body to assigning pupils. I don’t know

whether it is relevant. But to save time, do you have

any local rules on that subject?

Mr. Chapman: You are asking him?

The Court: Does the local Board have any local

rules on when pupils should apply for transfer?

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs—Direet

46a

The Witness: No, sir. The only rule that the

School Board adopted was with regard to the divid

ing line and the new North High School and the

lines were withdrawn and we wouldn’t consider any

requests to transfer from one school to another.

But, other than that, I know of none.

—32—

The Court: He said the School Board doesn’t

have any rules.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. As I understood your previous testimony, you recom

mended that these transfers be denied when you trans

mitted them to the Pupil Placement Board, but you did not

indicate any reasons to the Pupil Placement Board for

your recommendation; is that correct? A. That is correct.

Q. Hid you at any subsequent time before they were or

any subsequent time tell the Pupil Placement Board your

reasons? A. No, sir.

Q. Did you have any formal or informal conferences

with the Board or its staff about these pupils? A. No, sir.

Except the applications were presented to the Board. That

is in the minutes.

Q. Presented to your local School Board? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you or any of your assistants or staff have any

conferences with the State Pupil Placement Board or any

of its Staff about these pupils or send them any memoran

dum or anything like that? A. No, sir.

—33—

Q. Before they acted? A. No, sir.

Q. Did you do anything after they acted? A. No, sir.

Q. What was your reason for recommending—did you

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs—Direct

47a

have a reason for recommending that these transfers be

denied! A. Yes, sir.

# # # # *

—37—

The Court: What reason did you have? First let

me ask you: These recommendations are signed by

E. B. Broadwater, Assistant Superintendent. That

is not you?

The Witness: No, sir.

The Court: Bid you make any written recom

mendations?

The Witness: No. Mr. Broadwater signed them

at my request.

The Court: As an assistant?

The Witness: My responsibility. I made the deci

sion.

—38—

The Court: You told him, in other words, what

to put in there ?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: For what reason did you recommend

that these applicants should be assigned to Carver

School? That is the question.

The Witness: For the reason that we had the

space for these children at Carver School and we

did not have the space for them at Clearbrook

School. And these children, regardless of what race

or creed they would have been, I would have made

the same recommendation.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Now, with reference to the space, how did you de

termine that? Did you make an investigation? What did

Herman L. Horn—for Plaintiffs—Direct

48a

you do? A. No, I didn’t have to make an investigation.

I had the facts that the schools had been organized, the