Parrish v. Board of Commissioners of the Alabama State Bar Supplemental Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

July 7, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Parrish v. Board of Commissioners of the Alabama State Bar Supplemental Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1975. 7f71fd93-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f8290233-f057-4dd9-9635-6d12315c17b8/parrish-v-board-of-commissioners-of-the-alabama-state-bar-supplemental-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

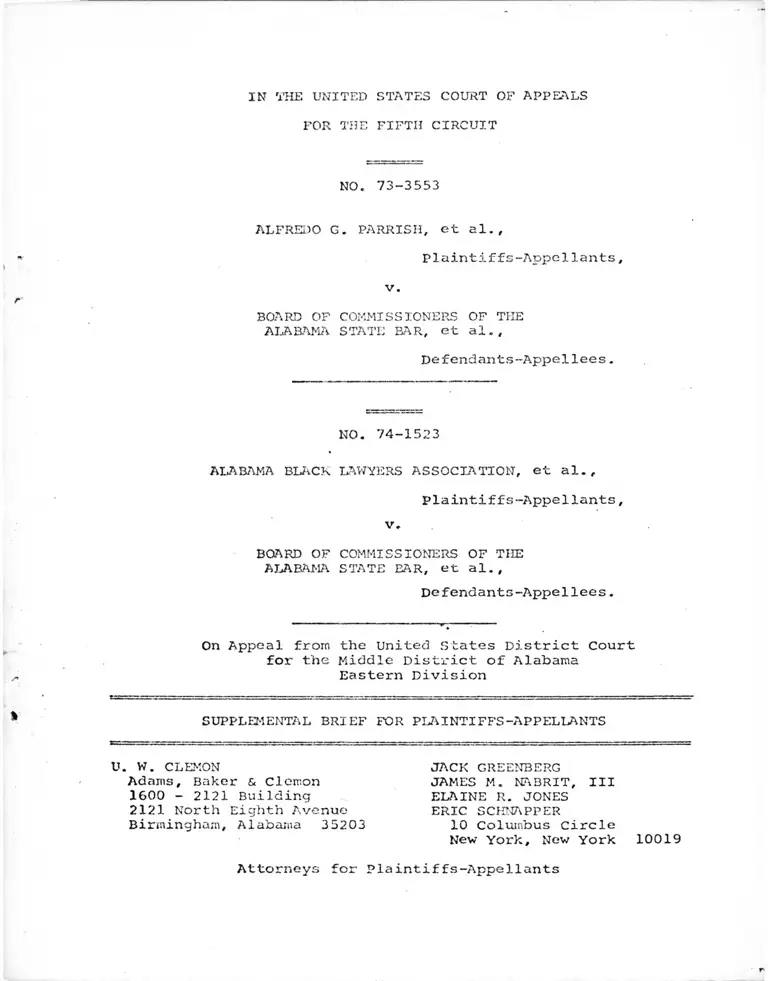

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 73-3553

ALFREDO G. PARRISH, et al. ,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS OF THE ALABAMA STATE BAR, et ai.,

Defendants-Appellees.

NO. 74-1523

ALABAMA BLACK LAWYERS ASSOCIATION, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS OF THE ALABAMA STATE EAR, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Alabama

Eastern Division

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

U. W. CLEMON

Adams, Baker & demon 1600 - 2121 Building 2121 North Eighth Avenue

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

JACK GREENBERG JAMES M. NABRIT, III ELAINE R. JONES ERIC SCKNAPPER10 Columbus CircleNew York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

IN THE UlTITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 73-3553

ALFREDO G. PARRISH, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS OF THE ALABAMA STATE BAR, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

♦

NO. 74-1523

ALABAMA BLACK LAWYERS ASSOCIATION, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS OF THE ALABAMA STATE BAR, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama

Eastern Division

CERTIFICATE

The undersigned counsel of record for plaintiffs-appellants,

Alfredo G. Parrish, et als., certifies that the following listed

parties have an interest in the outcome of this case. These

representations are made in order that judges of this Court may

evaluate possible disqualification or recusal pursuant to Local

Rule 13 (a).

1. Alfredo G. Parrish

2. Prentis Cook

3. Henry L. Thompson

4. Henry C. Tribbitt

5. Charles Robinson

6. Eddie Jones

7. Thomas Gray

8. Alabama Black Lawyers' Association

9. The foregoing plaintiffs-appellants bring

this action individually and on behalf of all blacks who are

or have been applicants to the Alabama State Bar who are

similarly situated.

10. The Board of Commissioners of the Alabama

State Bar and the Board of Examiners on admission to the

Alabama State Bar and their members are defendants-appellees.

ii

r -

page

Certificate Required by Local Rule 13(a) .................... i

List of Authorities......................................... iv

Questions Presented for Review.......... ................... viii

Statement of the Case....................................... 1

Statement of the Facts.................. ................... 3

ARGUMENT:

I. THIS COURT HAS JURISDICTION OF THIS APPEAL

OVER THE EIGHT NAMED PLAINTIFFS AND THE

ALABAMA BLACK LAWYERS' ASSOCIATION.................. 4

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FINDING THERE WAS NO GENUINE ISSUE AS TO ANY MATERIAL

FACT AND AS A MATTER OF LAW GRANTING SUMMARY JUDGMENT FOR DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES

ON ALL ISSUES....................................... 5

A. Denial of Discovery............................. 5

B. The District Court Erred By Granting Summary Judgment for the Defendants

On the Testing Issue...... ..................... 10

C. Summary Judgment is an Inappropriate

Method of Disposing of a Case Such as

the One At Bar.................................. 18

III. THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN HOLDING THAT CODE

OF ALABAMA, TITLE VII, SECTIONS 26 AND 36

BAR THE CLAIMS OF PLAINTIFFS EDDIE JONES AND THOMAS GRAY AND DISMISSING THEM AS

PARTY PLAINTIFFS.................................... 22

IV. THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN DISMISSING THE

ORGANIZATIONAL PLAINTIFF, THE ALABAMA BLACK

LAWYERS' ASSOCIATION, AS A PARTY PLAINTIFF

FOR LACK OF STANDING................................ 24

V. ON RELAND THIS CASE MUST BE HEARD BY ADIFFERENT JUDGE..................................... 25

CONCLUSION .......................... 55

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE...................................... 56

TABLE OF CONTENTS

iii

TABLE OF CASES

Abbott v. Thetford, No. 3847-N (M.D. Ala. 1972).............. 42Adams v. United States, 302 F.2d 307 (5th Cir. 1962)..29,30,44,49

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, __ U.S. __ , 43 U.S.L.W.

4880 (June 25, 1975)....... ............................ 14,15

Allen v. Mobile, 466 F.2d 122 (5th Cir. 1972),cert, denied 412 U.S. 909 (1973)........................ 13Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness Society,

43 U.S.L.W. 4561 (1975)............... ................... 45Antonello v. Wunsch, 500 F.2d 1260 (10th Cir. 1974).......... 32

Armstead v. Starkville Municipal Separate School

District, 461 F.2d 276 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 2 . 11/15

Baker v. Columbus Municipal Separate SchoolDistrict, 462 F.2d 1112 (5th Cir. 1972)............. 11,15,17-

Beland v. United States, 117 F.2d 958 (5th Cir. 1941)........ 29Berger v. United States, 255 U.S. 22 (1921)...... 26,27,28,29,3132,33,34,42

Botts v. United States, 413 F.2d 41

(9th Cir. 1969)............................................ 31Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond,

416 U.S. 696 (1974)........ ............................... 41Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Civil Service Commission,

482 F. 2d 1333 (2nd Cir. 1973)............. 13Broome v. Simon, 255 F. Supp. 434 (W.D. La. 1965)........ 51

Burns v. Thiokol, 483 F.2d 30 (5th Cir. 1973),reh. denied 485 F.2d 687 (5th Cir. 1974)................... 7

California Bankers Assn. v. Shultz, 416 U.S. 21 (1974)..... 24

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971)............ 13Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972).......... . 11

Chachas Petition, In re, 369 P.2d 455 .......... ............. 7Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.£d 1167 (2d Cir. 1972).... 11

Chaney v. California, 386 F.2d 962 (9th Cir. 1967)........... 7

Commonwealth Coatings Corp. v. Continental CasualtyCo., 393 U.S. 145 (1968)...................... 36,37,38,46,51

Croley v. Matson Navigation Co., 434 F.2d 73

(5th Cir. 1970)............................................ I9

Davis v. Washington, 512 F.2d 956..................... ....... 13Doe v. Bolton, 410 U.S. 179 (1973)............................ 24Douglas v. Hampton, 512 F.2d 976 (D.C. Cir. 1975).......... 12,13

Edwards v. United States, 334 F.2d 369 (5th Cir. 1964)..... 40,42

Gallarelli v. United States, 260 F.2d 259 (1st Cir. 1958).... 31

Gay v. United States, 411 U.S. 974 (1973)..................... 39

Gibson v. Berryhill, 411 U.S. 564 (1973).... ................. 51Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar, ___ U.S. ___, 43 U.S.L.W.

4723 (1973) 13

Page

iv

Page

Government of Virgin Islands v. Gereau, 502 F.2d 914

(3rd Cir. 1974)............................................ 31Greenberg v. General Mills Fun Group, Inc.,

478 F. 2d 254 (5th Cir. 1973).............................. 19Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).............. 11,13

Henry v. Speer, 201 Fed. 869 (5th Cir. 1913).............. 28,29

Heyward v. Public Housing Administration, 238 F.2d 689

(5th Cir. 1956)............................................ 21Hodgson v. Liquor Salesman's Union, 444 F.2d 1344

(2nd Cir. 1971)............................................ 32

Johnson v. Mississippi, 403 U.S. 212 (1971)................... 36

Kennedy v. Silas Mason Co., 334 U.S. 290 (1948)................ 21

Laird v. Tatum, 409 U.S. 824 (1972)........................ 40,49Lanza, In re, 104 So.2d 342 (Fla. 1958)....................... 8

Loer, Application of, 226 P.2d 272........................... 7

Mayberry v. Pennsylvania, 400 U.S. 455 (1971).............. 31,36

Miles, In re, 180 P.2d 99 ................... ................ 7Mitchell v. Sirica, 502 F.2d 375 (D.C. Cir. 1974),

cert, denied __ U.S. __ (1974)............................. 31Morrow v. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir. 1972)............. 13

Murchison, In re, 349 U.S. 133 (1955)...................... 35,48

N.A.A.C.P. v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir. 1974) ........ 11,13

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963)................... 24

Parrish v. Board of Commissioners, 505 F.2d 12(5th Cir. 1974) , opinion withdrawn, Feb. 20, 1975......... 26

Pfizer v. Lord, 456 F.2d 532 (7th Cir. 1972) ................ 32Public Utilities Commission v. Poliak, 343 U.S. 451 (1952).... 35

Rauls v. Daughters, 491 F.2d 141 (5th Cir. 1974).......... . 19Relf v. Montgomery Community Action Committee, No.

4099-N, July 3, 1973........................................ 42Riley-Stabler Construction Co. v. Westinghouse,

401 F. 2d 526 (5th Cir. 1968) ............. ............... . 19

Roberson v. United States, 249 F.2d 737 (5th Cir. 1958)...... 49

Simmons v. United States, 89 F.2d 591 (5th Cir. 1937)...... . 29

Sinderman v. Perry, 430 F.2d 939 (5th Cir. 1970), aff'd

408 U.S. 593 ....................................... 18,20

Staley v. California, 109 P.2d 667 (1941)..... ................ 7

Toebelman v. Missouri-Kansas Pipeline Co., 130 F.2d 1016

(3rd Cir. 1942) 9Turney v. Ohio, 273 U.S. 510 (1927) ........................ 34,46Tyler v. Vickery, N.D. Ga., Aug. 14, 1972, 5th Cir.

No. 74-3413 ............................................... 8

v

Page

Union Leader Corp., In re, 292 F.2d 381 (1st Cir. 1961)...... 31

United States v. Bell, 351 F.2d 868 (6th Cir. 1965)......... .. 32

United States v. Columbia Broadcasting System,

497 F. 2d 107 (5th Cir. 1974)............................... 30United States v. Indrelunas, 411 U.S. 216 (1973)............. 4United States v. Jacksonville Terminal, 451 F.2d 418

(5th Cir. 1971)............................................ 6United States v. Ming, 466 F.2d 1000 (7th Cir. 1972)......... 31

United States v. Roca-Alvarez, 451 F.2d 843 (5t.h Cir. 1971),

reh. granted on other grounds, 474 F.2d 1274 (5th Cir.

1973)...................................................... 29United States v. Students Challenging Regulatory AgencyProcedures (SCRAP), 412 U.S. 669 (1973)........... 24United States v. Thompson, 479 F.2d 1072 (3rd Cir. 1973).. 31United States v. Tropiano, 418 F.2d 1069 (2nd Cir. 1969).. 31

United States v. Womack, 454 F.2d 1337 (5th Cir. 1972)....... 29

Upper Dublin v. Germantown, 2 Dallas (2 US) 213 (1793)....... 34

Whitaker v. McLean, 118 F.2d 596 (D.D.C. 1941)............... 31

XRT, Inc. v. Krellenstein, 448 F.2d 772 (5th Cir. 1971)...... 8

References

Note, Disqualification of a Federal District Judge for Bias - the Standard Under Section 144,

57 Minn. L. Rev. 749 (1973).

Note, Disqualification of Judges for Bias in the

Federal Courts, 79 Harv. L. Rev. 1435 (1966).

Frank, Disqualification of Judges: In Support of the

Bayh Bill, 35 Law & Contemp. Probs. 43 (1940).

Wright & Miller, Federal Practice & Procedure

(Civil) § 2732.

vi

Federal Statutes

1 Stat. 279, ch.36, §11

3 Stat. 643, ch.51

62 Stat. 898

28 U.S.C. §144

28 U.S.C. §455, as amended by Pub.L.93-512, 88

. Stat. 1609 (1974)

State Statutes ,

Code of Alabama, Title 46, §26 (1940)

Statutes

Administrative Regulations

Testing Guidelines of the EEOC, 29 CFR §1607.5 (a)

Authorities

ABA Opinions of the Committee on Professional Ethics,

Formal Opinion 200, Jan.27, 1940.

Canons of Judicial Ethics

Code of Judicial Conduct

Congressional Record

42 Cong. Rec. 262943 Cong. Rec. 306 (1910)

120 Cong. Rec. 10729 daily ed., Nov.18, 1974)

Hearing on S.1064 Before the Subcommittee on Improvements in Judicial Machinery of the Senate Judiciary

Committee, 93rd Cong., 1st Sess. (1973).

Reports

S. Rep. 93-419, 93rd Cong., 1st Sess. (1973)

H. Rep. 93-1453, 93rd Cong., 2nd Sess. (1974)

Reporter's Notes to the Code of Judicial Conduct

vii

Questions Presented for Review

I. Whether this Court has jurisdiction over all the

issues raised by plaintiffs-appellants in these cases.

II. Whether the district court improperly granted

summary judgment for the defendants in this case where

A. Discovery was incomplete,

B. The defendants administer an unvalidated

test having a disproportionate adverse

effect on blacks, and

C. Conflicting inferences may be drawn from the evidence; questions of motivation, intent, and credibility are involved; and novel constitutional issues of substantial

public import are raised.

III. Whether'"the district court erred by dismissing the

claims of plaintiffs-appellants Eddie Jones and Thomas Gray.

IV. Whether the district court erred by dismissing the

plaintiff-appellant, Alabama Black Lawyers' Association, for

lack of standing.

V. Whether this case must be assigned to a different

judge on remand.

viii

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 73-3553

ALFREDO G. PARRISH, et al. ,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS OF THE ALABAMA STATE BAR, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

NO. 74-1523

ALABAMA BLACK LAWYERS ASSOCIATION, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS OF THE

ALABAMA STATE BAR, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama

Eastern Division

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

Plaintiffs-appellants herein incorporate the Statement of

the Case in the Opening Brief at pp. 1-12 and the Restatement of

the Case in the Reply Brief at pp. 1-3. The Opening Brief of

plaintiffs-appellants was filed on or about December 16, 1973;

the Reply Brief, on or about January 29, 1974.

On February 7, 1974, the district judge complied with the

"separate document" requirement of F.R.C.P. 58 and entered a

final judgment in the case below. Plaintiffs-appellants then

on or about February 13, 1974 filed a notice of appeal individ

ually naming all eight named plaintiffs and the Alabama Black

Lawyers' Association as appellants. This appeal was docketed

as No. 74-1523 in this Court and was consolidated with No. 73-

3553.

This case was fully argued on the merits and submitted to

a panel of this Court of Judges Tuttle, Wisdom, and Gee on June

11, 1974. On December 2, 1974, this panel of judges issued an

opinion in this case which opinion and judgment was withdrawn by

order dated February 20, 1975. By Order dated June 5, 1975,II

this Court on its own motion vacated the submission of the cause

to the panel of judges and determined to hear this case en banc

on briefs without oral argument. Plaintiffs-appellants, pursuant

to the Court's direction, serve this Supplemental Brief on July

7, 1975.

-2-

Statement of the Facts

The facts are the same as those set forth in the

"Statement of Facts" at pps. 13-23 of the Opening Brief of

Plaintiffs-Appellants and at pps.4-5 of the Reply Brief.

Plaintiffs-Appellants herein adopt and incorporate by refer

ence those statements of fact.

-3-

ARGUMENT

I

THIS COURT HAS JURISDICTION OF THIS APPEAL

OVER THE EIGHT NAMED PLAINTIFFS AND THE

ALABAMA BLACK LAWYERS 1 ASSOCIATION.

All eight named plaintiffs and the organizational plaintiff

the Alabama Black Lawyers' Association, are properly before this

Court on this appeal.

The district court issued a memorandum opinion which was

filed on August 21, 1973 granting summary judgment against the

plaintiffs-appellants on all issues (App. 456). However, the

court below failed to comply with the "separate document" require

ment of F.R.C.P. 58 and the pronouncement of the United States

Supreme Court in United States v. Indrelunas, 411 U.S. 216 (1973)

See Reply Brief at pp. 2-3. Plaintiffs-appellants then prema

turely filed a notice of appeal (R. 586) and an amended notice

of appeal (R. 592), which appeal was docketed in this Court as

No. 73-3553. By those notices, appellants clearly intended to

appeal on behalf of all of the plaintiffs, including the Alabama

Black Lawyers' Association. See Reply Brief at pp. 20-22.

In filing their brief in No. 73-3553 on or about January

14, 1974, defendants-appellees asserted that the notice and

amended notice of appeal were technically defective and failed

to comply with FRAP 3(c). Appellees' Brief at pp. 10-13. It

then came to the attention of plaintiffs-appellants who promptly

notified the district court that the district judge had not

entered a final judgment in the cause below as required by the

-4-

separate document provision of F.R.C.P. 58. On February 7,

1974, the district court complied with the separate document

requirement and entered a final judgment in the case below.

Plaintiffs thereupon filed a timely notice of appeal on or about

February 13, 1974, individually naming all parties to the appeal.

See Reply Brief at p. 3 (filed on or about January 28, 1974).

The appeal was docketed in this Court as case No. 74—1523. The

cases, Nos. 73-3553 and 74-1523, were consolidated in February,

1974.

Plaintiffs-appellants are, therefore, in compliance with

FRAP 3(c) and all jurisdictional prerequisites have been met.

The notice of appeal filed in No. 74-1523 individually names all

the parties to the appeal including those named in No. 73-3553.

XI

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FINDING THERE WAS NO GENUINE ISSUE AS TO ANY MATERIAL

FACT AND AS A MATTER OF LAW GRANTING SUMMARY JUDGMENT FOR DEFENDANT-APPELLEES

ON ALL ISSUES.

A. Denial of Discovery

The single most relevant matter of discovery sought by

appellants in the court below was the graded examination papers.

The motion to compel production of these graded papers was one

of the outstanding discovery motions at the time the district

court granted summary judgment for the defendants. See Appellees'

Opening Brief, Statement of the Facts at p. 11, Argument at pp.

29-31, and Reply Brief at pp. 7-9.

-5-

One of the very critical issues in this case is appel

lants' claim that appellees restrict the number of blacks

admitted to the Alabama State Bar through a policy and practice

of discriminatorily assigning grades to the papers of applicants

to the bar examination (Complaint, pp. 7-8).

The graded papers constitute the "proof of the pudding,"

for an analysis of them would reveal whether in fact the papers

of black examinees were graded differently than those of white

examinees. If such analysis reflected that substantially identi

cal responses of black and white examinees were graded in a

similar manner, then the self-serving declaration of nondiscrim

ination in assigning grades to examination papers by the

individual bar examiners would be firmly established. If, on

the other hand, the analysis revealed that similar responses of

black and white examinees were graded differently, then conceiv

ably appellants could establish a prima facie case of racial

idiscrimination in the grading process, and the burden of proof

would then shift to the bar examiners. United States v.

Jacksonville Terminal, 451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971). In any

event, it is clear that the most promising approach to contro

verting the bar examiners' denial of a policy of racially diŝ -

criminatory grading procedures is to look to the papers actually

graded by the examiners. The actual graded examination papers

would provide the best evidence as to whether the bar examination

papers are graded fairly, without racial bias. In this area of

the law, documentary and statistical evidence mean much more

than ex parte affidavits.

-6-

Of course, the graded examination papers are most relevant

to a resolution of the claim of discrimination with respect

thereto, and any assertion to the contrary cannot stand under

clearly established legal principles. Cf. Burns v. Thiokol,

483 F. 2d 30 (5th Cir. 1973), reh. den. 485 F.2d 687 (5th Cir.

1974). Besides, under Rule 26(b)(1) a party is entitled to

discover any information, not privileged, which "... appears

reasonably calculated to lead to the discovery of admissible

evidence."

The district court's failure to consider appellants'

motion to compel the production of the graded examination papers

was effectively a denial of the motion. Opening Brief at p. 11,

R. 355, 480, 545. Appellees in their brief concede that the

appellants were denied discovery "of the answers to the 1973

examinations by all examinees, the grades assigned to each

examinee, and any examiner's grading notes" (Appellees' Brief

at p. 3).

None of the cases cited by the defendants, in support of

their non-production of examination papers, actually stand for

the proposition cited. We have discussed the Chaney case, 386

F.2d 962 (9th Cir. 1967), in our reply brief at pp. 8-9. In

Staley v. California, 109 P.2d 667 (1941), cited at pp. 24, 29

of Appellees' Brief, as the dissent clearly points out, the

applicant actually was given his examination paper, and they

were regraded by a law professor. In the Miles, 180 P.2d 99,

Loer, 226 P.2d 272, and Chachas, 369 P.2d 455 cases, cited by

the defendants at pp. 24, 25 of their original brief, the

-7-

petitioning bar applicant was permitted to review his examina

tion paper. In the Tyler v. Vickery case (N.D. Ga., decided

Aug. 14, 1972, 5th Cir. No. 74-3413), the district court initially

denied summary judgement for precisely the reason that the

examination papers had not been made available to the plaintiffs

for their analysis.

See also, In re Lanza, 104 So.2d 342 (Fla. 1958), cited

by the defendants at p. 29 of their original brief, where the

Florida Supreme Court specifically examined the Florida bar

exam questions and "... selected at random and examined numerous

papers and grades given by individual examiners ...." Id. at 344.

As a result of its independent examination, the court found:

The failure to pass the subject examination is

by no means an indication that all of such

applicants are not qualified for admission to

the Bar ...." Id.

Appellants have earlier cited a host of cases for the

proposition that in passing on a motion for summary judgment,

a court must carefully consider whether the party opposing the

motion has had access to proof; and where the proof is peculiarly

within the knowledge or control of the defendants, plaintiffs

should be afforded every opportunity to proceed with discovery.

See citations. Opening Brief at p. 31. The denial of the motion

precluded appellants from controverting the declaration of non

discrimination by the bar examiners, and in these circumstances,

a grant of summary judgment for the defendants, examiners, and

Others was manifest error. XRT, Inc, v. Krellenstein, 448 F.2d.

772 (5th Cir. 1971), is but one of the many authorities holding

that where, as here, the party opposing summary judgment is

-8-

unable to controvert the supporting affidavits therefor without

access to relevant papers in the possession of the movants, a

grant of summary judgment constitutes reversible error. See

also Toebelman v, Mlssouri-Kansas Pipe Line Co., 130 F.2d 1016

(3rd Cir. 1942) .

At the time the motion for summary judgment was granted

to the defendants there were also outstanding motions to compel

answers to interrogatories. Appellants' Opening Brief at pp.

10-11, Reply Brief at pp. 1-2. This denial of discovery was

discussed in both briefs filed earlier by appellants and will

not be further discussed here.

The district court clearly erred in granting summary judg

ment without a prior disposition of the outstanding discovery

motions.

IIh

-9-

B. The District Court Erred Bv Granting Summary

Judgment for the Defendants On The Testing Issue.

Traditionally, the vast majority of the Alabama lawyers

have been graduates of the University of Alabama's law school.

1/ . ^As such, they were exempt by statute from taking a bar examina

tion. This practice prevailed until four years or so after the

famous Autherine Lucy case — which first opened the doors of the

University of Alabama to black citizens of the State. In 1961,

for the first time, all persons who wished to practice law in

Alabama were required to take a bar examination.

There is no contention that the diploma privilege in

Alabama resulted in an incompetent or marginally competent bar.

Quite to the contrary, many of the leading practitioners in the

state have never taken a bar examination. Indeed, the trial

judge himself is a product of the diploma privilege; seven of.

the twelve incumbent defendant bar examiners are beneficiaries

* — — |7 "

of the diploma privilege. Any conclusion that the State of

1/ Title 46 §26 of the Code of Alabama of 1940 provided:Whenever the president and dea'n of the law department

of the University of Alabama shall certify to the

secretary of the board of commissioners that the university has conferred the degree of bachelor of law

upon a graduate in that department, it shallbe the duty 'of such secretary upon presentment within twelve months of such certificate to enter the name of such graduate upon the rolls of the state bar, and such graduate upon

complying with the other terms of this article shall without further examination become a member of the state

bar, with a i f The rights, duties and privileges of the

other members thereof, (emphasis supplied).

This section was abolished, effective in 1961. Id.

u Examiners Frank Donaldson, Bob Kendall, Vivian Johnston, M

Clinton McGee, L. Tennant Lee, Knox McMillan, and Philip Shank have never taken a bar examination. (A .37 b, JO J , ,

427, 435, 443, 448) .

-10-

Alabama has a "compelling state interest" in administering a bar

examination particularly one which has a disparate effect on

blacks, is simply unsupported by history and the experience of

a long period of time during which nearly all of the lawyers in

the State never took a bar examination without any noticeable

adverse effect on the public at large.

Where employment tests are shown to have a disparate

effect on the employment opportunities of blacks, the Constitution

of the United States and applicable statutes require that such

tests be validated, i.e., that they be shown by professional

testing standards actually to measure an applicant's ability

to perform the job he seeks. Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S.

424 (1971); Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir., 1972);

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167 (2d Cir., 1972) .

In NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir., 1974) this Court

affirmed a district court's conclusion that where a written test

and an oral interview had disqualified blacks from employment as

Alabama State Troopers, and neither was validated to correlate

successful scores with successful job performance, affirmative

remedial relief in the form of quotas is warranted. Id.

The arguments of the defendant bar examiners - that Griggs

does not apply to "professional tests" administered by bar asso

ciations and, alternatively, that since the Alabama bar association

is not an employer, it is free to administer invalidated tests

having disparate effects on blacks - overlook the relevant

authorities to the contrary. Baker v. Columbus Municipal Separate

School District, 462 F.2d 1112 (5th Cir., 1972) and Armstead v.

Starkvi1le Municipal Separate School District, 461 F.2d 276 (5th

Cir., 1972) both involved the use by school boards of unvalidated,

professional examinations (The National Teachers Examination and

the Graduate Record Examination) which were shown to have a

disparate impact on black teachers. This Court sanctioned an

. . i/injunction against their further use. In reaching its decision

in Baker, this Court specifically relied on the undisputed facts

that there, as here,

. . . NTE cut-off score requirement was set byappellants without any investigation or study of

the validity and reliability of the examination or the cut-off score as a means of selecting teachers for hiring or re-employment. Id., at 1114.

The District of Columbia Court of Appeals, in the recent case of

Douglas v. Hampton, 512 F.2d 976, (D.C. Cir. 1975), held that

where the Federal Service Entrance Examination - the primary

avenue of entry into professional jobs with the federal government

was shown to have a disproportionately adverse effect on black

_3/ In Armstead, Judge Dyer observed:

The use of the GRE test has operated to exclude

more blacks than whites from the teaching pro

fession in Starkville. Starkville asserts that the reductions occurred because it desired to

improve the faculty and the appellees were not

among those who met the minimum standards esta

blished . A school board's desire to employ ‘the best teachers available is both legitimate

and commendable. However, in attempting to attain this laudatory objective, Starkvxllc

must not deny to any person the equal protection of the lawsJ

. . . Those who attain a minimum score on the GRE

are classified as suitable for employment while

those who fail to meet this mark are automatically

rejected. Although Starkville may have some

discretion to establish an appropriate classifica

tion, the classification must not be an arbitrary

one. Id. 279, 280. (emphasis supplied).

12

employment, the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments require that

the examination must be validated. Citing such cases as Davis

v. Washington, 512 F.2d 976, (D.C. Cir., 1975), Bridgeport

Guardians, Inc, v. Civil Service Commission, 482 F.2d 1333

(2nd Cir., 1973), Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir.

1971), and Allen v. Mobile, 466 F.2d 122 (5th Cir., 1972), cert,

denied, 412 U.S. 909 (1973), the Douglas court properly noted

that " . . . the applicability of the Griggs standard has also

been recognized in numerous cases involving public employees not

grounded in Title VII." Id_. , at 981

It is settled then, that bar associations are not immune

from the relevant authorities requiring validation of examinations

which have a disparate effect on blacks, just as the United States

Supreme Court recently held that such associations enjoy no special

immunity from the antitrust laws because of their asserted status

as a "learned profession." Goldfarb et al. v, Virginia State Bar

et al. , _____U.S. _____, 43 U.S.L.W. 4723 (1975).

Criterion-related empirical studies have been recognized

as the best means of validating employment tests having a disparate

4/impact. Testing Guidelines of the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission, 29 C.F.R. §1607.5(a). NAACP v. Allen, supra. Morrow

v. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053, 1056 (5th Cir., 1972).

4/ Criterion related validity is demonstrated by comparing test

scores with one or more external criteria to provide a direct

measure of the job behavior which the test is intended to

predict. Critcria-related validity may be predictive (i.e.,

testing job applicants and comparing their test scores with

some criteria data of job performance collected at a later

date) or concurrent (i.e., testing present employees and

comparing their test scores with criteria collected con

currently with the testing).

13

In Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, _____U.S. ______ (Slip

Opinion dated June 25, 1975), the United States Supreme Court

reasoned that the question of "job relatedness" should bo

determined by reference to the EEOC Guidelines on Testing,

29 C.F.R. 1607(1974), for the Guidelines constitute ”'[t]he

administrative interpretation of the Act by the enforcing agency',

and consequently they are 'entitled to great deference'." Mr.

Justice Stewart, in writing the 7-1 opinion for the court, re

affirmed the law as earlier pronounced by this and other circuits:

. . . discriminatory tests [i.e., tests having a

racially disparate impact] are impermissible unless shown, by professionally acceptable methods,

to be predictive of or significantly correlated

with important elements of work behavior which

comprise or are relevant to the job or jobs for

which candidates are being evaluated. Id_. , Slip

Opinion at p.24. (emphasis supplied).

The court then proceeded to set aside a purported validation study

because, inter alia,1) the study did not contain an analysis of the

5/attributes of, or the particular skills needed in, the studied

job groups, (Id., p.25); and 2) the criteria of job performance

utilized by the study was not shown .to be sufficiently related

to specific job ability so as to justify a testing system with

5/ The defendants seemingly admit in their original brief that

the Alabama bar examination does not purport to be pre

dictive of job performance as a lawyer:"Far too many factors are operative in the practice

of law to measure success on any examination. The bar examination simply seeks to protect the public

from the admission to practice law of persons who on examination are found not to possess the minimal

knowledge and skill reasonably required to practice

law." Original Brief of Defendants-Appellees, p.31.

14

a racially discriminatory impact. Id., p.26.

The latter two considerations of the court in Albemarle

carry particular significance in the case at bar. First, the

Alabama Bar Association, when confronted with a test having a

disparate impact, has never undertaken, or, for that matter,

considered, any kind of validity studies. The cut-off score

of 70 on the bar examination was established without reference

to any job analyses or criteria of job performance. The defend

ants apparently feel that they have relatively unbridled dis

cretion to set the cut-off score on the examination at any point 6/

they so desire - without consideration of whether the cut-off

score bears any demonstrable relationship to the actual practice

of law. If this is their position, then they are surely mistaken.

Cf. Baker, supra at 1114; Armstead, supra, at 279-280.

Of course, the question of the arbitrary setting of a

cut-off score on the bar examination is reached only after it is

determined that the test is otherwise validated. As hereinbefore

explained, the Alabama bar examination has not been so validated.

It has yet to be shown, for example, that a prospective civil

6/ "It can always be argued that an applicant should

pass with a 69 rather than a 70, but if it is conceded that the public is entitled to some protection

as to who is qualified to hold himself out as a

lawyer, then it becomes a matter of degree — of

drawing a line. Under Alabama law the discretion

is placed in the Alabama Bar Commission under the review of the Alabama Supreme Court." Original

Brief of Appellees, p.31.

15

rights lawyer will likely be unsuccessful in his practice

because he performs poorly on business corporations, taxation,

the uniform commercial code, and wills and trusts sections of

the bar examination. The more relevant concern here should be

that such a hypothetical applicant would not be examined, under

current policies of the defendant bar commissioners, in the one

field in which he intends to specilize. Any attempt, therefore,9/

to establish that the Alabama bar examination is content valid

must fall, for content validity studies" . . . should be accom

panied by sufficient information from job analyses to demonstrate

the relevance of the content." 29 C.F.R. §1607.5(a). No such

job analyses have been made by the defendants in this case.

The defendants' contention that the number of blacks taking

the Alabama bar examination is statistically insignificant to

establish its racially disparate impact is totally devoid of

support in the record of this case. For their responses to

2/

1/ Most of the bar examiners are themselves specialists in one or more fields of law. Many of them limit their practice to various phases of commercial/property/probate law.

(A.370, 398, 378, 444, 391, 437, 402). As such they seldom have professional contacts with black lawyers. Id.

8/ if such a hypothetical applicant scored less than seventy

in these four areas of the Alabama bar examination, he

would fail the exam. (A . 84j .

9/ Content validity is established by showing that the test

is composed on items which are relevant to and representative

of the field which it is supposed to cover.

16

requests for admissions reflect that in the two year period

preceding the commencement of this action (June 1970-June 1972),

wsome forty (40) blacks took the Alabama bar examination. (A.144)

Only ten of those (25%) passed the examination. Id. The pass

rate for whites during the same period was 74.7%. (A.119-128) .

In fact, the defendants have admitted that the pass rate for

whites on the bar examination is three times that of blacks.

(A.143-144) .

In summary, the district court erred by granting summary

judgment to the defendants on the testing issue, because they

were not "entitled to judgment as a matter of law." In point

of fact, the relevant decisional law, to the extent that discovery

had been completed, the facts were otherwise undisputed, and the

permissible inferences to be drawn from the undisputed facts

were non-conflicting in nature, then summary judgment on the

testing issue should have been granted for plaintiffs-appellants.

10/ Compare, for example, Baker, supra, where this Court upheld

a trial court's finding of disparate impact arising out of an examination administered to only eighteen blacks.

17

C. Summary Judgment Is An Inappropriate Methodof Disposing of a Case Such as the One At Bar.

In Sinderman v. Perry, 430 F.2d 939 (5th Cir. 1970), aff'd 408

U. S . 593 , Judge Clark stated the relevant consider a t ions with respect to

summary judgment:

"Summary judgment should be granted only when the

truth is clear, where the basic facts are undisputed

and the parties are not in disagreement regarding material factual inferences that may be properly

drawn from such facts." Id_. , at 943

Judge Clark further observed that while this Circuit has, on occasion

" . . . affirmed the use of summary judgment to dispose of con

stitutional issues, [citing cases] this form of disposition is

often inappropriate in cases involving issues of far-flung import."

Id. On each of the considerations referred to by the Sinderman

court, summary judgment must fail in the instant case. The trial

judge candidly conceded in his memorandum opinion that he was un

certain of ". . . what the factual allegations are and what the

*2/denials are." (A .458) . This realization alone should have moved

the court to deny summary judgment - or at the very least, to

postpone it until a pretrial could be'had and the issues delineated.

Had the latter procedure been followed, for example, the district

court may well have passed, favorably or otherwise, on plaintiffs’

claim that the bar examiners arbitrarily grade papers (A.9, }[2 5D) -

which was not disposed of in the district court's summary judgment

opinion. In a situation where a trial court is unfamiliar with

all of the claims of the parties, a summary procedure which disposes

iy The defendants never filed an answer to the complaint.

18

of the entire case is, at best, ill-advised.

This case is one in which states of mind— intent, motiva

tion, design must be taken into account. This is particularly

true of the allegations of racial discrimination in the adminis

tration and grading of bar examinations. The evidence indicated

that bar examiners, despite their affidavits attesting to a policy

of anonymity, are amply possessed of the opportunity to dis

criminate, (A.93). In fact, one of the bar examiners has ad

mitted that on two occasions, he has known both the name and the

identification number of examinees whose papers he had yet to

grade. (A.370). A resolution of whether the bar examiners have

ever utilized this opportunity to discriminate necessarily re

quires inquiry into their state of mind, their intent, motivation

and, additionally, it may require credibility assessments.

The decisional law applicable to a grant of summary judg

ment under these facts is plain and unamibiguous:"Where state of

mind is to be measured it cannot be resolved on summary judgment.

Riley-Stabler Construction Co. v. Westinghouse, 401 F.2d 526

(5th Cir., 1968); Accord, Rauls v. Daughters, 491 F.2d 141 (5th

Cir., 1974); Greenberg v. General Mills Fun Group, Inc., 478 F.2d

254 (5th Cir., 1973).

I t

"The court should be cautious in granting a motion

for summary judgment when resolution of the dispositive issue requires a determination of state of mind.

Much depends on the credibility of witnesses testifying as to their own states of mind. In these circum

stances, the [court] should be given an opportunity

to observe the demeanor, during direct and cross

examination, of the witnesses whose states of mind

are at issue." Croley v. Matson Navigation Co., 434

F .2d 73, 77 (5th Cir., 1970).

19

See also, 10 Wright and Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure

(Civil) §2732.

Moreover, summary judgment is a singularly inappropriate

means of disposing of the case at bar because of the multitude

of conflicting inferences which may be drawn from such undisputed

facts as may be found in the record. By way of example, the

fact is undisputed that all applicants for the bar examination

are required to submit photographs along with their applications.

It is also undisputed that these photographs have never been used

to identify the persons who actually sit for the examination.

One might just as easily infer 1) that the photograph require

ment serves no valid purpose, 2) that the photograph requirement

enables the bar secretary to identify black applicants and there

after to assign certain identification numbers to them, or 3) that

the mere existence of the requirement deters non-applicants from

taking the examination in the name of applicants. The trial

court reversibly erred by choosing between these conflicting

inferences in granting summary judgment. We have discussed in

our original brief, at pp.32-35 the misuse of other inferences

by the district court, and that discussion is incorporated herein

by reference.

In addition to the considerations hereinbefore outlined, the

present case obviously raises constitutional and novel legal issues

of substantial public import. Sinderman, supra. In Alabama,

where one out of every four citizens is black, less than one out

of every 100 lawyers is black. For whatever reason, usually only

two blacks, per semi-annual examination,are rated by the all-white

20

board of bar examiners as being qualified to practice law in

Alabama. In the meanwhile, hundreds of new white lawyers enter

the profession annually. When blacks were precluded by law from

securing a legal education in Alabama, the graduates of the

University of Alabama's law school were exempt from taking a

bar examination. In short, this case is pregnant with live

constitutional issues of greatest public importance, and the

district court's resort to summary procedures to preclude an

airing of these issues invites reversal by this court. Kennedy

v. Silas Mason Co., 334 U.S. 290, 256-57 (1948); Heyward v. Public

Housing Administration, 238 F.2d 689, 698 (5th Cir., 1956).

- 21 -

Ill

THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN HOLDING THAT CODE OF

ALABAMA, TITLE VII, SECTIONS 26 AND 36 BAR

THE CLAIMS OF PLAINTIFFS EDDIE JONES AND

THOMAS GRAY AND DISMISSING THEM AS PARTY

PLAINTIFFS.

Plaintiffs-Appellants in the Opening Brief and Reply Brief

have fully set forth the legal and factual bases in support of the

argument that the district court erred in dismissing Eddie Jones

and Thomas Gray as party plaintiffs. Opening Brief; Statement

of Facts at pps. 4-6; Argument at pps. 46-51; Reply Brief at

pps. 11-19.

Since this issue has been extensively briefed, appellants

need here simply point out the gross factual misrepresentation

made by appellees as to the claim of appellant Gray at pps. 48-49

of Appellees brief. Appellee therein asserts that the unsuccessful

application filed by plaintiff Gray for a fourth sitting on the

bar examination in February 1972 (within the one year statutory

period applied to this case, Reply Brief at p.46), "was not

presented to or considered by the trial court" (Appellees Br.

at 48). Appellees then go on for one and a half pages to assert

that the dismissal of Gray [although he applied as did Jones to

sit for the examination within the period of limitations] "cannot

now be urged as error . . . for the first time on this appeal"

(Appellees br. at 48). Quite the contrary. Plaintiffs-appellants

did specifically bring to the district court's attention by way

of a formal motion filed on March 29, 1973 to reconsider the

dismissal of Gray as a party plaintiff, that plaintiff-appellant

Qray had petitioned the Board of Examiners for a fourth sitting

22

on the February 1972 bar examination, which petition was denied

on February 10, 1972, a point in time within the one year statute

of limitations applied to this case (R.236-37). The motion was

specifically denied by the district court in an order filed

April 23, 1973 (App.254; R.359). Appellees are wrong when they

represent to this Court that Plaintiffs-Appellants failed to so

inform the district court. The record before this Court is

also clear that plaintiff-appellant Jones was denied a fourth

' sitting on the bar examination within the one year statutory

period and these facts by formal motion were brought to the

attention of the district judge who denied the motion to reconsider

his dismissal as party plaintiff (R. 146,229).

Jones and Gray contend that their petitions were arbitrarily

denied. It was clear error for the district court to dismiss

them as not having standing to raise the issue of whether the

defendants act arbitrarily and capriciously in deciding who will

be permitted a fourth sitting on the bar examination. (App.463-64) .

23

IV

THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN DISMISSING THE ORGANIZATIONAL PLAINTIFF, THE ALABAMA BLACK LAWYERS’ ASSOCIATION, AS A PARTY

PLAINTIFF FOR LACK OF STANDING.

The allegations in the Complaint and amendments thereto

as to the Alabama Black Lawyers' Association ("ABLA") are set

forth in the Statement of the Facts. Appellants' Opening Brief

at pp. 6-8 . The organizational interest of the "ABLA" in this

litigation and arguments in support of standing are set forth

at Appellants' Opening Brief at pp. 42-45. Additionally, since

there are at least five named plaintiffs who have standing to

raise the issues in this litigation, the "ABLA" also has standing

since its dismissal in no way avoids the resolution of any of

the constitutional issues herein raised. California Bankers

Assn, v. Shultz, 416 U.S. 21, 44-45 (1974); Doe v. Bolton, 410

U.S. 179 (1973); N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963).

The "ABLA" through discriminatory practices of the appellees

has its membership limited and suffers a loss of revenue, which

restricts its efforts to further the programs of the organization.

The organization seeks to aid its members in developing partner

ships, firms, and professional associations. The practice of

defendants-appellees in severely restricting the number of black

attorneys in the State of Alabama has a significant if not

determinative effect on the ability of the "ABLA" to continue

to exist as a viable organization. United States v. Students

Challenging Regulatory Agency Procedures (SCRAP), 412 U.S. 669

(1973).

24

V

ON REMAND THIS CASE MUST BE HEARD

BY A DIFFERENT JUDGE

Since further proceedings will be necessary on remand

with regard to the merits of this action, this Court must

determine whether the case on remand should be heard by a

different district judge.

In deciding whether a new judge should be directed to

hear this case on remand, the Court must look to five sources

involving somewhat different standards — 28 U.S.C. § 144, 28

U.S.C. § 455, the Code of Judicial Conduct, the constitutional

requirement of due process, and this Court's supervisory powers.

Plaintiffs maintain that, under each and every one of these

standards, it would be inappropriate for the further proceedings

in this case to be conducted by the district judge to whom it

was originally assigned. Inasmuch as the decision below must

in any event be reversed and remanded on other grounds, this

Court should apply to the question of recusal a more liberal

standard than might be appropriate in a case in which an other

wise valid judgment is attacked solely because of a judge's

failure to disqualify himself.

(1) Section 144

Section 144, 28 U.S.C., provides in pertinent part:

Whenever a party to any proceeding in a district court makes and files a timely and sufficient affidavit that the judge before whom the matter is

pending has a personal bias or prejudice either

against him or in favor of any adverse party, such

judge shall proceed no further therein, but another

25

judge shall be assigned to hear such proceeding.

The affidavit shall state the facts and the

reasons for the belief that bias or prejudice

exists, ....

As the original panel in this appeal noted, there is a wide

spread controversy among the circuits as to when the contents

of an affidavit are legally sufficient. See Parrish v. Board

of Commissioners, 505 F.2d 12 (5th Cir. 1974). The Courts of

Appeals are now divided as to whether section 144 requires (a)

that the facts alleged demonstrate that the judge is biased in

fact, or (b) that the alleged facts create an appearance of bias

rendering reasonable the affiant's belief. See generally Note,

Disqualification of Judges for Bias in the Federal Courts, 79

Harv. L. Rev. 1435 (1966); Note, Disqualification of a Federal

District Judge for Bias— The Standard Under Section 144, 57

Minn. L. Rev. 749 (1973); Frank, Disqualification of Judges: In

Support of the Bayh Bill, 35 Law and Contemp. Probs. 43, 58-60

(1970).

This question was raised and resolved over half a century

ago in Berger v. United States, 255 U.S. 22 (1921). Berger

recognized that the provision that the affidavit must state

"the facts and the reasons for the belief" entailed an enforce

able requirement that the contents of the affidavit bear some

minimal relation to the affiant's belief that the judge is biased.

Upon the making and filing by a party of an

affidavit under the provisions of section [144], of necessity there is imposed upon the

judge the duty of examining the affidavit to

determine whether or not it is the affidavit specified and required by the statute and to determine its legal sufficiency. 255 U.S. at

32.

But the requireqment of "legal sufficiency" did not mean the

affidavit must prove the judge to be biased, for nothing in

section 144 requires that the judge actually be biased. Section

144 requires, rather, a good faith belief by the party, and it

is to substantiate the existence of this belief that the affi

davit is required. Accordingly, the standard set by Berger is

that the affidavit

must give fair support to the charge of a bent

of mind that may prevent or impede impartiality

of judgment. The affidavit of defendants has

that character. The facts and reasons it states are not frivolous or fanciful, but substantial and formidable, and they have relation to the attitude of Judge Landis's mind towards the

defendants. 255 U.S. at 33-34.

Thus the Supreme Court sustained the affidavit in Berger without

deciding, or considering, whether the challenged judge was

biased in fact.

The Court noted a variety of reasons for this affidavit

procedure and its construction of section 144. Congress, it

reasoned, was concerned

that the tribunals of the country shall not only be

impartial in the controversies submitted to them,

but shall give assurance that they are impartial

___ 255 U.S. at 35-36.

The Court repeatedly emphasized that the statute did not permit

the judge to pass on "the reality and sufficiency" of the facts

alleged in the affidavit, "the truth of its statements," or

"the question of his own disqualification." 255 U.S. at 32-33.

This limitation clearly makes no sense if the judge is to decide

whether the affidavit proves he is actually prejudiced. The

Court expressly approved the actions of a district judge in an

27

earlier case in deciding to recuse himself under section 144

"without reference to the merits of the charge of bias." 255

U.S. at 31. Justice McReynolds, although dissenting on the

facts, agreed with the majority as to the purpose and procedures

under section 144. The affidavit, he explained, must state

facts and reasons "in order that the judge or any reviewing

tribunal may determine whether they suffice to support honest

belief in the disqualifying state of mind." 255 U.S. 42.

Section 144 was intended to go beyond merely barring judges who

were actually biased.

Of course, no judge should preside if he entertained actual personal prejudice towards any

party, and to this obvious disqualification

Congress added honestly entertained belief of

such prejudice when based upon fairly adequate

facts and circumstances. 255 U.S. at 43.

(Emphasis added)

So long as the facts alleged are sufficient to render reasonable

the party's belief that the judge is biased, recusal is mandatory.

The history of recusal motions in this Circuit does not

reveal any deliberate departure from Berger. This Court's

decision in Henry v. Speer, 201 Fed. 869 (5th Cir. 1913), pre

saged Berger and adopted a similar standard. The Court there

held that the alleged facts need only be the type which "tend

to show the existence of a personal prejudice or bias." Section

144 was said to relieve the judge "from the delicate and trying

duty of deciding upon the question of his own disqualification,"

i.e., of whether he was actually biased. 201 Fed. at 872. The

next decision, some 26 years later, stated two apparently

inconsistent standards— that the facts alleged must "show good

28

cause for recusation within the letter and intent of the statute

and "[show] the personal prejudice of the judge against the

defendants." Simmons v. United States 89 F.2d 591, 592-3 (5th

Cir. 1937). Simmons, which referred to Berger but not Speer,

was followed by Beland v. United States, 117 F.2d 958 (5th Cir.

1941), which made no pretense of following or reference to either.

Beland asserted the affidavit must state facts "showing the

personal bias or prejudice of the judge." 117 F.2d at 960.

The more recent decisions of the Court give little guidance

as to the standard under section 144, but articulate more

clearly the underlying policies regarding recusal. In United

States v. Womack, 454 F.2d 1337 (5th Cir. 1972), the Court held

an affidavit legally sufficient under section 144, but did not

hold that the district judge was actually biased or that the

affidavit had proved that he was. In United States v. Roca —

Alvarez, 451 F.2d 843 (5th Cir. 1971), rehearing granted on other

grounds 474 F.2d 1274 (5th Cir. 1973), the Court held an affi

davit legally insufficient because the facts alleged gave "no indi

cation" of bias. Whether the facts alleged need only "indicate"

bias, 474 F.2d at 848, or whether this term was mere hyperbole,

is not apparent from the court's opinion.

While these decisions leave unclear the legal standard

set by section 144, the applicable policies has been unambiguously

announced in other contexts. In Adams v. United States, 302

F. 2d 307 (5th Cir. 1962), the defendant sought to set aside a

verdict on the ground that the judge had served as the United

States Attorney during a time when defendant's case was being

29

-*uS

investigated, a fact apparently unknown to the judge and defen

dant during the trial. The issue arose under § 455, which does

not limit the judge's role in the manner of § 144 and which

then set a less demanding substantive standard. Despite this,

the majority in Adams concluded that, had he actually known

the facts, recusal would have been appropriate "in the interest

of making absolutely certain that the trial judge acts with

complete impartiality." 320 U.S. at 310. Judge Brown, dis

senting, adopted a similar prophylactic approach, insisting

that the defendant was entitled to "a trial by a judge who not

only is_ fair and impartial, but who meets the requirements of

the statutory policy designed to assure impartiality and the

appearance of it.“ 302 F.2d at 314 (Emphasis added). Neither

the majority nor the dissenting judge expressed any concern

that the district court judge was biased in fact.

Similarly in United States v. Columbia Broadcasting System,

497 F.2d 107 (5th Cir. 1974), a contempt proceeding, the Court

concluded that the judge against whom the alleged contempt

occurred "may well have had the unique ability to be an impartial

judge in the circumstances." 497 F.2d at 110. The Court con

cluded, however, that the contempt charges should be tried

before a different judge in order "to protect the judicial pro

cess from any suspicion of bias." Id.

The recondite niceties of contempt law coupled

with the strange milieu of a judge passing on the

clarity of his own orders, which had to be substantiated largely by his own legal staff, should

make us particularly sensitive to the demands of

justice, and more particularly, to the appearance

of justice. The guarantee to the defendant of a

30

totally fair and impartial tribunal, and the pro

tection of the integrity and dignity of the judicial process from any hint or appearance of

bias is the palladium of our judicial system.

497 F.2d at 109. This conclusion was reached, not because of

the special procedural protections of section 144, but under

the court's supervisory powers and by analogy to the constitutional

guarantee of a fair trial. See Mayberry v. Pennsylvania, 400

U.S. 455 (1971).

The other circuits are widely divided on this question,

a problem complicated by a paucity of discussion as to the

differences in the standards and a certain variation over time.

Judged by their latest decisions, six circuits appear to adhere

to the Berger standard. The Second, Third, Seventh, and Ninth

Circuits, quoting Berger, have held an affidavit to be suffi

cient if it gives "fair support to the charge of a bent of mind

1 2 /

that may prevent or impede impartiality of judgment." The

Third Circuit expressly noted that this was different than

11/requiring that the affidavit prove actual bias. The First and

District of Columbia Circuits have rephrased Berger in their

own language, clearly rejecting any requirement that prejudice14/

be actually proven. The Sixth, Eighth, and Tenth Circuits

12-/ United States v. Tropiano, 418 F.2d 1069, 1077 (2d Cir. 1969);

United States v. Thompson, 479 F.2d 1072, 1073—4 (3d Cir. 1973);

United States v. Ming, 466 F.2d 1000, 1004 (7th Cir. 1972); Botts

v. United States, 413 F.2d 41 (9th Cir. 1969).

13/ Government of Virgin Islands v. Gereau, 502 F.2d 914, 932

(3d Cir. 1974).

14/ In re Union Leader Corporation, 292 F.2d 381, 389 (1st Cir. 1961) (affidavit need only "indicate" possible bias); Gallarclli

V. United States, 260 F.2d 259, 261 (1st Cir. 1958) (facts need only be of the sort which "tend to show" bias); Whitaker v.

McLean, 118 F.2d 596 (D.D.C. 1941) (Judge's remarks need only "evidence" bias); Mitchell v. Sirica, 502 F.2d 375, 381-3 (D.C.

Cir. 1974) (MacKinnon, J. dissenting) cert, den. __ U.S. __ (1974).

- 31 -

r

have chosen to disregard Berger and now require that the affiant

15/allege facts which demonstrate that bias exists. The majority

view, however, is that articulated by the Second Circuit in

Hodgson v. Liquor Salesmen's Union, 444 F.2d 1344, 1348 (2d Cir.

1971), that "the purpose of the section is to avoid the appearance

as well as the actual existence of bias or prejudice."

Plaintiffs maintain that Berger was correctly decided

and is still good law. Section 144 was adopted in 1911 as part

of the Judiciary Act of that year. Prior to 1911 the question

of recusal was largely in the discretion of the judge, who was

only obliged to act if facts were adduced proving disqualifica-

16/tion. Congressman Cullop, the author of section 141, explained

that it was intended to serve two purposes. First it was to

prevent any litigant from having his case tried before a judge

whom he honestly believed to be biased.

[T]he litigant ought to have an opportunity to

have his case tried before a court that he believes to be fair and impartial. It is unfair to litigants to be compelled to come at any time

before a court where they think they cannot have

a fair trial. It is a reproach to the admini

stration of justice to require them to do so ....

I can conceive no greater wrong imposed upon a

citizen, however high or humble, than to compel him to submit his case, an important matter to him, to a court in which he fears justice will

not be administered to him. 42 Cong. Rec. 306

(1910).

JL 5/ United States v. Bell, 351 F.2d 8 6 8, 879 (6th Cir. 1965) (affidavit must "show that there exists bias and prejudice");

Pfizer v. Lord, 456 F.2d 532, 537 (7th Cir. 1972) (affidavit must "demonstrate this bias or prejudice" and show the "validity

of petitioner's conclusion of bias"); Antonello v. Wunsch, 500

F.2d 1260, 1260 (10th Cir. 1974) (affidavit must "state facts

showing personal bias and.prejudice").

16/ See 1 Stat., ch. 36, p. 279, § 11; 3 Stat., ch. 51, p. 643.

32

Second, section 141 was designed to take from the judge involved

the discretion he had hitherto enjoyed to decide whether he

was qualified.

[W]here it is a personal matter to the judge, a

charge against him, it ought not be left to his

discretion, and I submit that if he is a conscientious man, he does not want it left to him.It ought to be taken away from him and taken away from him by the lav/. When a charge is made against the qualification of any judge that he is biased,

that he is taking sides one way or the other, that question ought not be left to him to be passed upon.

Judges are heirs to the same frailties that other men are, and they ought not be required to pass upon and decide questions personal to themselves, and as a delicate question they ought not want to

pass upon such a question as that. Id.

Representative Cullop later expressly rejected the suggestion

that the allegedly biased judge would be able to decide if the

reasons stated in the affidavit proved he was prejudiced.

Mr. MANN. It has been suggested here by Members

that under this amendment offered by the gentleman,

the judge would have a discretion in passing upon the matter, and he would have the right to examine and ascertain whether the reasons were sufficient.

Now, that is plainly not the purpose of the gentle

man from Indiana. is there any reason why it should

be left in uncertainty?

Mr. BENNETT of New York. Not at all.

Mr. MANN. When you undertake to say that a man shall file an affidavit of prejudice, and give

the reason for his prejudice, is there not some

question as to whether that does not permit the judge to pass upon the reasons? Otherwise, what is

the object of giving the reason?

Mr. CULLOP. No; because the very provision of the statute is that he shall proceed no further. 42

Cong. Rec. 2629.

In the light of this legislative history, Berger correctly con

cluded that a mere appearance of bias was sufficient under

section 144.

31

Nothing that the Supreme Court has said since Berger

■*»calls into question the vitality of that decision. In the

intervening years the constitutional standard has grown prog

ressively more strict, and now requires recusal under circum

stances far short of actual bias. See pp. 34—37, infra.

Nor has Congress given any indication that it thought Berger

erroneous or prefers a more lax approach; on the contrary, ^ ^

Congress readopted section 144 in 1948 in the face of Berger,

and last year amended section 455 to set disqualification

standards far more strict than had hitherto existed under that

provision. See pp. 37-41, infra.

(2) The Constitutional Standard

At least since Upper Dublin v. Germantown, 2 Dallas (U.S.)

213 (1793), the Supreme Court has enforced certain minimal

constitutional standards as to when due process requires that

a judge not sit in a proceeding. /

The seminal case in modern times is Turney v. Ohio, 273

U.S. 510 (1927). In Turney, the defendant in a criminal case

was tried before a judge who received, as part of his compensa

tion, a portion of all fines collected. The Court held that due

process of law guaranteed the defendant a trial before a judge

who had no such interest in the outcome of the proceeding. The

Court did not rest its decision on a finding that the judge

was actually prejudiced, but on the ground that the procedure

offered "a possible temptation to the average man." 273 U.S. at

u T 62 Stat. 898

34

532. 349 U.S. 133 (1955),In re Murchlson/held that a judge who had sat as a one-

man grand jury could not also try a case of alleged contempt of

that grand jury, since there was a danger that his responsi

bilities as judge would be tainted by his interest as grand

juror. In reversing Murchison's conviction, the Supreme court

did not rule the judge had been biased in fact, but reasoned

"[a] fair trial in a fair tribunal is a basic Requirement of

due process. Fairness, of course, requires an absence of actual

bias in the trial of cases. But our system has always endeavored

to prevent even the probability of unfairness," 349 U.S. at 133.

The first enunciation of the "appearance of bias" test

came in a non-constitutional decision, Public Utilities Com

mission v. Poliak, 343 U.S. 451 (1952). That case involved a

challenge to the practice of playing radio programs over loud

speakers in public buses in Washington, D. C. Mr. Justice

Frankfurter, declaring himself "strongly enraged as a victim"

of the practice, declined to participate in the case. He

explained, "when there is ground for believing that such uncon

scious feelings may operate in the ultimate judgment, or may

not unfairly lead others to believe they are operating, judges

should recuse themselves. They do not sit in judgment. They

do this for a variety of reasons. The guiding consideration

is that the administration of justice should reasonably appear

to be disinterested as well as to be so in fact." 343 U.S. at

466-67.

35

This principle found its first constitutional application

in Commonwealth Coatings Corp. v. Continental Casualty Co.,

393 U.S. 145 (1960). In that case, an arbitrator, unbeknownst

to one of the parties, had had substantial business dealings

with the other party prior to hearing the case. Inasmuch as

the arbitration had occurred pursuant to a federal statute,

due process was at issue, and the Supreme Court held that as

a matter of "constitutional principle" such a financial relation

ship with a party precluded an arbitrator from adjudicating a

case just as it would bar a judge or a juror. The Court found

its decision in part "on the premise that any tribunal permitted

by law to try cases and controversies not only must be unbiased

but also must avoid even the appearance of bias." 393 U.S. at

150.

Three years later the same principle was applied to the

evolving standards of fairness regarding summary contempt

proceedings. In Mayberry v. Pennsylvania, 400 U.S. 455 (1971),

the defendant was held in contempt by a judge whom he had

personally attacked throughout the course of the trial. Noting

the possibility that the attacks might have influenced the

judge's attitude toward Mayberry, the Supreme Court held that

the case had to be retried before a new judge since "justice

must satisfy the appearance of justice," 400 U.S. at 465. See

also Johnson v. Mississippi, 403 U.S. 212 (1971).

This guiding constitutional principle that a judge must

not sit where there is a mere appearance of bias applies a_

fortiori to federal judges over whom the appellate courts have

36

special supervisory responsibilities.

(3) The Code of Judicial Conduct and 5 455

That this case should be heard on remand by a new district

judge is also dictated by the Code of Judicial Conduct and by

28 U.S.C. § 455.

Both the Code and section 455 expressly adopt an "appear

ance of bias" standard similar to that applied by several

circuits under section 144 and enunciated in Commonwealth Coatings.

The original Canons of Judicial Ethics, first adopted in 1924,

called on judges not to participate in certain specified circum-

18/stances and further provided in Canon 4 that "[a] judge's

official conduct should be free from impropriety and the appear

ance of impropriety." The A.B.A. Committee on Professional

Ethics construed Canon 4 to apply to decisions by a judge whether

to sit in a particular case, and stated:

A judge should studiously avoid wherever possible

every situation that might reasonably give rise to

the impression on the part of litigants or the public that his decisions were influenced by favoritism ....

The responsibility is on the judge not to sit in a case unless he is both free from bias and from the

appearance thereof. 1 9 /

This construction of Canon 4 was expressly adopted by the new

Code of Judicial Conduct approved by the A.B.A. House of Delegates

in 1972. Canon 3(C)(1) of the Code provides: that "[a] judge

shall disqualify himself in a proceeding in which his impartiality

18/ see, e.g.. Canon 13 (near relative a party). Canon 29 (case

in which judge has a personal interest).

ISl/ Formal Opinion 200, January 27, 1940, published in A.B.A. Opinions of the Committee on Professional Ethics.

might reasonably be questioned." The Reporter's Notes state;

The disqualification section begins with a

general standard that is the policy for dis

qualification— that is, "A judge should

disqualify himself in any proceeding in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned."The general standard is followed by a series of

four specific disqualification standards that the Committee determined to be of sufficient importance to be set forth in detail. Although

the specific standards cover most of the situations

in which the disqualification issue will arise, the general standard should not be overlooked.Any conduct that would lead a reasonable man

knowing all the circumstances to the conclusion

that the judge's "impartiality might reasonably be questioned" is a basis for the judge's dis

qualification. Thus, an impropriety or the appearance of impropriety in violation of Canon

2 that would reasonably lead one to question the judge's impartiality in a given proceeding clearly falls within the scope of the general

standard, as does participation by the judge in

the proceeding if he thereby creates the appear

ance of a lack of impartiality. 2 0/

The Reporter's Notes expressly indicate that this "appearance

21/of bias" standard also derives from Commonwealth Coatings. The

decision to include this language appears to stem in part from

the contemporaneous legislative proposals of Senator Bayh, which

in turn were an outgrowth of the Seriate's refusal to confirm

the nomination of Judge Haynsworth. See Frank, Disqualification

of Judges: In Support of the Bayh Bill, 35 Law and Contemp.

227Probs. 43, 64 (1970)'.

The new Canon 2, in language similar to the original Canon

4, provides in more general terms that "A judge should avoid

2Sl/ Reporter's Notes to Code of Judicial Conduct, pp. 60-61.

21/ Id.

2 2/ The background and importance of the "appearance of bias"

standard is discussed at pp. 58-60.

30

impropriety and the appearance of impropriety in all his activ

ities." The Supreme Court apparently regards the enforcement

of Canon 3 as within the supervisory powers of the appellate

courts. See Gay v. United States, 411 U.S. 974 (1973) (Opinion

of Justice Douglas).

The "appearance of bias" standard of Canon 3(C)(1) was

incorporated by Congress in 28 U.S.C. § 455, as amended in 1974,

Public Law 93-512; 88 Stat. 1609. Section 455(a) provides:

Any justice, judge, magistrate, or referree in

bankruptcy of the United States shall disqualify

himself in any proceeding in which his imparti

ality might reasonably be questioned.

Both the House and Senate reports stated that the purpose of the

1974 amendment was to "conform" section 455 to the standard of

the new Code of Judicial Conduct and to render "the statutory23/

and ethical standard virtually identical." The House and

Senate reports explained subsection (a) as follows:

Subsection (a) of the amended section 455 con

tains the general, or catch-all, provision that a

judge shall disqualify himself in any proceeding

in which "his impartiality might reasonably be questioned." This sets up'-an objective standard, rather than the subjective standard set forth in

the existing statute through use of the phrase

"in his opinion." This general standard is designed to promote public confidence in the impar

tiality of the judicial process by saying, in

effect, if there is a reasonable factual basis for doubting the judge's impartiality, he should

disqualify himself and let another judge preside

over the case. 24/

22/ S. Rep. 93-419, 93rd