NAACP v. St. Louis-San Francisco RY. Co. Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1954

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. St. Louis-San Francisco RY. Co. Brief Amicus Curiae, 1954. ac9f8946-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f85ca4e3-093e-4019-a776-21822665c8f0/naacp-v-st-louis-san-francisco-ry-co-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

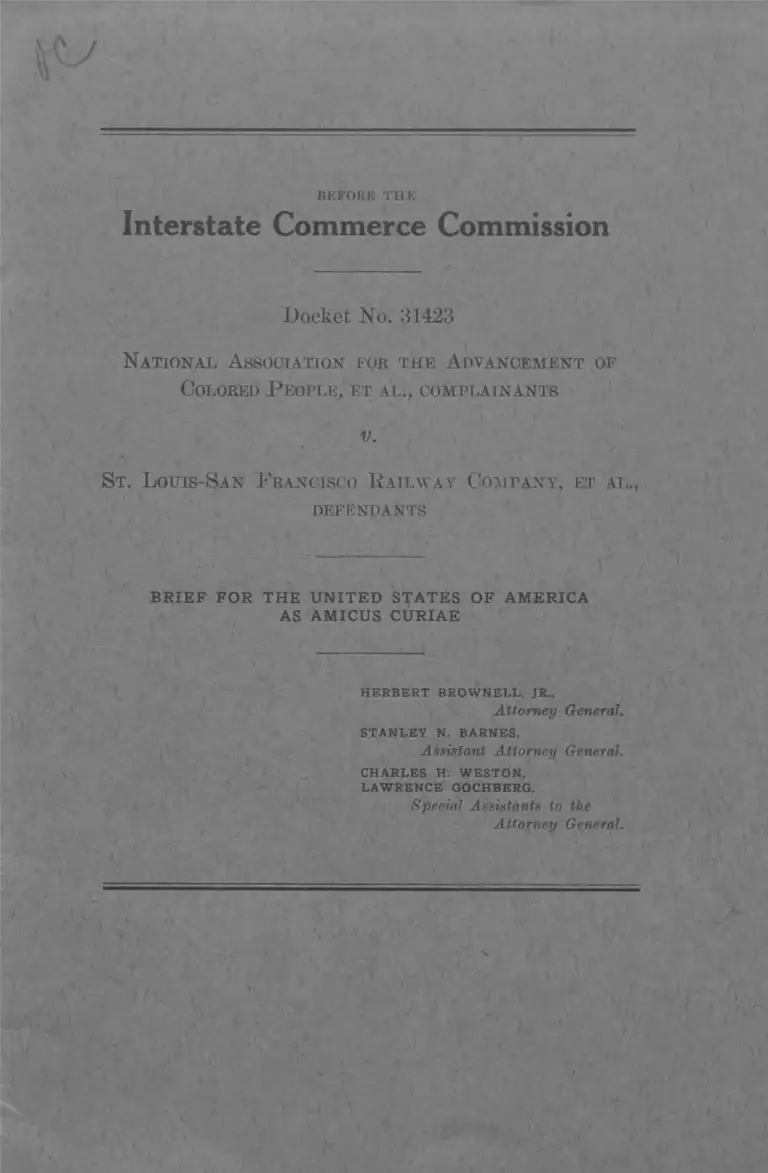

B E F O R E T H E

Interstate Commerce Commission

Docket No. 31423

N a t io n a l A s s o c ia t io n f o r t h e A d v a n c e m e n t of

C o lo re d P e o p l e , e t a l ., c o m p l a in a n t s

v.

S t . L o u is - S a n F r a n c is c o R a i l w a y C o m p a n y , e t a l

d e f e n d a n t s

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

AS AMICUS CURIAE

H E R B E R T B R O W N E L L , JR.,

Attorney General.

S T A N L E Y N. B A R N E S ,

Assistant Attorney General.

C H A R L E S H . W E S T O N .

L A W R E N C E G O C H B E R G ,

Special Assistants to the

Attorney General.

Statement of Tacts

I N D E X

Page

2

Argument:

I. The railroads’ regulations and practices requiring racial

segregation of interstate passengers violate Section 3(1)

of the Interstate Commerce A ct........................................... 4

A. Section 3(1) prohibits any form of discrimination

between interstate passengers the basis of which

is race ...................................................................... 4

B. Requiring Negro interstate passengers to occupy

coaches or portions of coaches set apart solely for

them is a discrimination prohibited by Section

3(1) ......................................... 5

C. No prior Supreme Court decision is controlling on

the question of the validity under the Interstate

Commerce Act of the carriers’ segregation rules

and practices ........................................................ 8

D. The segregation regulations offend against the due

process requirements of the Fifth Amendment,

and thereby violate Section 3(1) of the A ct........... 11

II. The carriers’ practices in imposing segregation constitute a

forbidden interference with interstate commerce................ 12

Conclusion .............................................................................................. 16

Cases:

CITATIONS

Atlantic Coast Line R. Co. v. Chance, 341 U.S. 941................. 15

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497..................................................... 11

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483................................ 6, 7,10

Carolina Coach Co. v. Williams, 207 F. 2d 408 (C.A. 4 ) .......... 15

Chance v. Lambeth, 186 F. 2d 879 (C.A. 4 ) .................................. 14-15

Chiles V. Chesapeake & Ohio Railway, 218 U.S. 71.............8, 9,11,15

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 ........................................................ 12

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U.S. 485.......................................................... 8,13

Henderson V. Southern Ry. Co., 284 I.C.C. 161......................... 16

Henderson v. United States, 339 U.S. 816....................................5, 9,12

Holcombe v. Beal, 347 U.S. 974..................................................... 10

Housing Authority of San Francisco v. Banks, 347 U.S. 974. . . 10

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637................. 6

Missouri v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337................................................. 6

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U.S. 80......................................4, 5, 7, 9

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373................................................... 13,14

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Assn., 347 U.S. 971............. 10

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537........................................ 7, 8, 9,10,16

Public Utilities Commission v. Poliak, 343 U.S. 451................... 12

Shelley v. Kracmer, 334 U.S. 1 ..................................................... 12

(i)

Cases— Continued

ii

Page

Solomon v. Pennsylvania R. Co., 96 F.Supp. 709 (S.D.N.Y.) 15

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629..................................................

The Shreveport Case, 234 U.S. 324...............................................

United States v. Pennsylvania R. Co., 323 U.S. 612................... 16

Whiteside v. Southern Bus Lines, 177 F. 2d 949 (C.A. 6 ) .......... 15

Miscellaneous:

Executive Order 10479,18 F.R. 4899 ........................................... 2

H. Rept. No. 2480, 83d Cong., 2d Sess., p. 2 ............................... 9

Official Guide of the Railways, August 1954, pp. 510-511, 576,

632-633, 938-939 ........................................................................ 13

CO

BEFORE THE

Interstate Commerce Commission

Docket No. 31423

N a t io n a l A s s o c ia t io n f o r t h e A d v a n c e m e n t o f

C o lo re d P e o p l e , e t a l ., c o m p l a in a n t s

v.

S t . L o u is - S a n F r a n c is c o R a i l w a y C o m p a n y , e t a l .,

DEFENDANTS

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

AS AMICUS CURIAE

The United States, through its Attorney General, con

siders it appropriate to file this brief as amicus curiae

because of the national importance of the questions of

federal law raised in this proceeding. These questions

deal with the right of a group of American citizens,

Negroes, to travel on trains in interstate commerce

free from the restraints now placed on such movement.

These rights consist of nothing more and nothing less

than those now enjoyed by all other interstate rail pas

sengers, citizen or non-citizen.

This proceeding against twelve rail carriers is not

merely local in scope and significance. The transpor

tation systems of the twelve railroads before this Com

mission link the South to the rest of the Nation. They

(1)

o

run from New York to Florida; from Illinois to Lou

isiana; from Georgia to California. In thus linking

North to South and East to West, they impose a sys

tem of segregation which arbitrarily creates for pur

poses of interstate rail travel two classes of citizens—

“ W hite” and “ Colored” .

It is the policy of the Federal Government, within the

limits of power vested in it, to put an end to racial seg

regation. The President has stated:

W e have used the power of the Federal Govern

ment, wherever it clearly extends, to combat and

erase racial discrimination and segregation— so

that no man of any color or creed will ever be able

to cry, “ This is not a free land.” 1

The United States contends that the practice of divid

ing passengers into two classes based solely on race

violates the Interstate Commerce Act. It is also the

position of the United States that segregation of this

kind, under and pursuant to this Commission’s sanction,

violates the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution.

S T A T E M E N T O F FA C T S

This is a proceeding against twelve rail carriers insti

tuted by the National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People, a non-profit corporation, and a num

ber of individual complainants. The amended com

plaint alleges that the defendant carriers require segre

1 “ Report to the Nation,” a radio address delivered from the

White House on August 6, 1953.

See also, the President’s Executive Order 10479, August, 1953,

18 F.R. 4899, establishing a Government Contract Committee to

eliminate racial discrimination in concerns working under Govern

ment contract.

3

gation of Negro interstate passengers from other in

terstate passengers solely on the basis of color or race;

and that by virtue of such practice, complainants have

been “ subjected to discriminatory and unequal treat

ment and to embarrassment and humiliation solely be

cause of race and color * * * ” (pars. 7, 8). Numerous

specific instances of the imposition of this system of seg

regation are cited. It is further alleged that the prac

tices, rules, or regulations under which the defendants

require segregation violate Sections 1(5), 2, and 3(1)

of the Interstate Commerce Act, the commerce clause

of the Constitution, and the Fifth and Fourteenth

Amendments (pars. 28-32).

The answers filed by the defendant carriers generally

deny any violation of the foregoing statutory and con

stitutional provisions. As to five of the defendants, an

evidentiary hearing was held to determine the nature of

their practices. As to the other seven defendants,2

separate stipulations of fact were entered into with

the complainants. These stipulations all set forth sub

stantially the following:

(1) Each carrier, as to certain or all of its trains

operating in interstate and intrastate commerce, desig

nates, assigns and sets aside specific coaches or portions

of coaches for exclusive occupancy by Negro pas

sengers.

(2) The coaches or portions thereof designated for

occupancy by Negro passengers are “ substantially

2 The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Co.; Atlantic

Coast Line Railroad Co.; Gulf, Mobile and Ohio Railroad Co.;

Kansas City Southern Railway Co.; Louisville and Nashville Rail

road Co.; St. Louis-San Francisco Railway Co.; and Southern Rail

way Co.

4

equal” to those designated for occupancy by passengers

not of the Negro race.

(3) The rates and fares charged Negro passengers

are the same as those charged all other passengers.

(4) The carrier’s practice of segregating Negro pas

sengers has existed continuously for more than fifty

years, pursuant to the public opinion, customs and

usages of some or all of the states through which the

carrier operates.

(5) All facts relevant to the Commission’s decision

are set forth in the stipulation.

Since the interest of the United States is in the broad

question of the legality of segregation rather than in

whether any specific defendant practices segregation,

this brief will deal with the legal issues as framed by

the stipulated facts.

A R G U M E N T

I

The Railroads’ Regulations and Practices Requiring Racial

Segregation of Interstate Passengers Violate Section 3 ( 1 )

ol' the Interstate Commerce Act

A. Section 3(1) Prohibits any Form of Discrimination

between Interstate Passengers the Basis of Which

is Race

Section 3(1) of the Interstate Commerce Act, 49

U. S. C. 3 (1 ), declares that it shall be unlawful for any

common carrier subject to the Act “ to subject any par

ticular person * * * to any undue or unreasonable preju

dice or disadvantage in any respect whatsoever.” It is

settled that this prohibition, which embraces all dis

criminations “ which it was within the power of Con

gress to condemn” ( The Shreveport Case, 234 U. S. 342,

356), bans any kind of discriminations the basis of

which is the race of the passenger. Mitchell v. United

5

States, 313 U. S. 80, 94-95; Henderson v. United States,

339 U. S. 816, 823. Indeed, this Commission from its

inception has recognized that the section applies to dis

crimination between white and Negro passengers. See

cases cited in Henderson case, supra, p. 823.

The equality of treatment required hy Section 3(1)

creates a right personal to the individual passenger.

Invasion of this right is not condoned by the fact that

disadvantages imposed on Negro passengers may be

likewise imposed on white passengers; and it is equally

unavailing that a disadvantage imposed by reason of

race may not adversely affect every passenger of that

race. Henderson case, supra, pp. 824-825; Mitchell case,

supra, p. 97.

B. Requiring Negro Interstate Passengers to Occupy

Coaches or Portions of Coaches Set Apart Solely

For Them is a Discrimination Prohibited by Sec

tion 3(1)

In the cases in which the Supreme Court has found

that discriminations based on race violate Section 3(1)

of the Interstate Commerce Act it was unnecessary to

decide more than that denial to one race of accommoda

tions available to the other ( Mitchell case), or postpon

ing for members of one race service currently aATailable

to members of the other (Henderson case), constitutes

undue “ prejudice” or “ disadvantage” within the mean

ing of Section 3(1) of the Interstate Commerce Act.

Here, where it is stipulated that the physical character

istics of the coaches to which Negro passengers are as

signed are substantially equal to those designated ex

clusively for non-Negro passengers, the issue is pre

sented whether enforced separation of the races is of

itself a prohibited discrimination.

6

The evolution of decision in the Supreme Court cases

dealing with segregation in the field of public education

is of great significance. First, it was held that to provide

for Negroes opportunity for education availalfle only

in an institution beyond the borders of a State, when

white students could attend an institution within the

State, offended against the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment. Missouri v. Canada, 305

U. S. 337. Later it was held that, as to a professional

school, factors “ incapable of objective measurement” ,

such as reputation of the faculty, position and influence

of the alumni, standing in the community, traditions

and prestige, must be taken into consideration in deter

mining whether substantial equality in educational op

portunity is afforded. Siveatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629.

Likewise it wTas held that equal protection is denied to a

Negro, who, although admitted to the same university as

wdiite students and accorded the same instruction and

physical facilities, is required to sit apart from others

in classroom, library and cafeteria. McLaurin v. Ok

lahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637. Finally, it was

held in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 495,

that “ in the field of public education, the doctrine of

1 separate but equal ’ has no place. Separate educational

facilities are inherently unequal.” Enforced separa

tion of white children and colored children in grade and

high schools was held to be inherently unequal pri

marily because such separation “ generates [in the lat

ter] a feeling o f inferiority as to their status in the

community” or, as stated in a district court finding

adopted by the Supreme Court, “ the policy of separat

ing the races is usually interpreted as denoting the in

feriority of the negro group.” Id., p. 494. And the Court

7

expressly rejected any language in Plessy v. Ferguson,

163 U. S. 537, contrary to such finding. Id. 494-495.

The Court in the Brown case was dealing with the

effect on colored children of segregated public schools.

But the factors which make such segregation “ inher

ently unequal” for them—that they understand segre

gation to signify their inferior status and are adversely

affected by being thus stigmatized—make segregation

in public transportation inherently unequal. In the

Brown case the Court relied upon psychological knowl

edge, as “ amply supported by modern authority,” for

the findings which were made the basis of decision. 347

U. S. at 494. Under the authorities which the Court

cited (id., fn. 11), it cannot be disputed that Negro rail

passengers are seriously and deeply affected when they

are separated from others solely because of their race,

and deem it a badge of inferiority when they are rele

gated to what have long been invidiously known as

“ Jim Crow” accommodations.

The “ separate but equal” doctrine having now been

repudiated in the field of public education, we submit

that this doctrine no longer retains vitality or authority

in the field of public transportation. By the same token

that segregation in schools, under the command of a

state, is a denial of the “ equal” protection of the laws

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment, segregation

in interstate travel is a denial of the “ equality of treat

ment” required by Section 3(1) of the Interstate Com

merce A ct.3

3 In the Mitchell case the Court said that Section 3(1) requires

“ equality of treatment,” and that a person denied such equality

because of his race is subjected to “ unreasonable prejudice or dis

advantage” within “ the purview of the sweeping prohibitions” of

Section 3(1). 313 U.S. at 94-95.

8

C. No prior Supreme Court Decision is Controlling on

the Question of the Validity under the Interstate

Commerce Act of the Carriers’ Segregation Rules

and Practices

Three Supreme Court adjudications are usually cited

in support o f the legality o f carrier rules providing for

segregation in interstate commerce. They are: Hall v.

DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485; Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537;

and Chiles v. Chesapeake & Ohio Railway, 218 U. S. 71.

None of them dealt specifically with the Interstate Com

merce Act, and the two former involved only constitu

tional questions. The holding in Hall v. DeCuir w7as

that a state statute outlawing segregation of interstate

passengers infringes on federal commerce power, and

in Plessy what the Court held was that a state statute

providing for segregation in intrastate transportation

is not invalid under the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Chiles case held that, in the absence of congres

sional legislation dealing with segregation in interstate

transportation, a carrier could lawfully require racial

segregation of interstate passengers. Although the Su

preme Court decided the case after the adoption of the

Interstate Commerce Act, the Court’s opinion does not

mention the Act and the briefs filed by the parties do

not even refer to Section 3 of the Act. Indeed, the

Court’s conclusion as to “ the inaction of Congress” re

specting segregation was rested upon its holding in

Hall v. DeCuir, 4 a case which was decided some ten

years before the enactment of the Interstate Commerce 4

4 The Court said (218 U.S. at 77): “ We have seen that it was

decided in Hall v. DeCuir that the inaction of Congress was

equivalent to the declaration that a carrier could by regulations

separate colored and white interstate passengers.”

9

Act. Therefore, whatever else the Chiles case deter

mined, it leaves undetermined the scope and effect of

Section 3. And the premise of decision in that case,

complete absence of federal legislation touching on seg

regation in interstate travel, has now been swept aside;

the later Mitchell and Henderson cases establish that

Section 3 does apply to and does ban any form of dis

crimination on the basis of race.5

W e submit, therefore, that the Chiles case is neither

controlling nor pertinent on the question now submitted

to this Commission, the effect and scope o f Section 3(1)

of the Interstate Commerce Act. W e submit further

that, even on the basis on which Chiles was decided, an

essential ground of decision has been undermined.

In Chiles the Court held (1) that, if Congress has not

spoken in the matter, an interstate carrier is free to

adopt regulations for the government of its business

provided such regulations are “ reasonable” , and (2)

that, in view of the holding in the Plessy case that it

is a reasonable exercise of a state’s police power to re

quire railroads to provide separate accommodations for

the white and colored races, regulations of a carrier

5 The recent congressional action regarding various bills designed

to make segregation in interestate travel illegal does not suggest

that segregation is not already illegal under the Interstate Com

merce Act. For the House Committee Report, which approved

a bill designed to outlaw segregation in interstate travel, states:

“ This bill does not establish a new policy but simply re

affirms and clarifies the general policy already adopted by Con

gress in several statutes, and implicit in common law, against

discrimination with respect to travel on common carriers operat

ing in interstate transportation.

“ This general congressional nondiscrimination policy con

cerning interstate transportation is present in section 3 (1)

of the Interstate Commerce Act * * *.” H. Rept. No. 2480,

83d Cong., 2d Sess., p. 2.

10

which so provide “ cannot be said to be unreasonable.”

218 U. S. at 76-77. But the bolding in Plessy which was

thus relied upon was bottomed upon the proposition

that laws requiring separation of the white and colored

races do not “ imply the inferiority of either race” (163

XL S. at 544). The Court there further emphasized this

point by saying (id., at 551) :

We consider the underlying fallacy of the plain

t iff ’s argument to consist in the assumption that the

enforced separation of the two races stamps the

colored race with the badge of inferiority.

This cornerstone of the Plessy decision has now been

swept aside. In the recent school segregation cases the

Court held that to separate colored children from white

solely because of race “ generates a feeling of inferiority

as to their status in the community” ; found that “ the

policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as

denoting the inferiority of the negro group” ; and “ re

jected” any “ contrary” language in Plessy. 6 347 U. S.

at 494-495. Clearly carrier regulations, such as those

o f the present defendants, which denote the inferiority

of a racial group and serve no legitimate transporta

6 The Supreme Court’s rulings immediately following its decision

in the school segregation cases make it clear that the principles

there applied are not confined solely to segregation in public edu

cation, but must be given consideration when segregation is en

forced in other fields. The Court vacated a judgment upholding

segregation in a privately-operated municipal amphitheater and

remanded the case “ for consideration in the light of the Segrega

tion Cases” (Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Assn., 347 U.S.

971); denied certiorari to review a judgment striking down segre

gation in public housing (Housing Authority of San Francisco v.

Ba,vks, 347 U.S. 974); and denied certiorari to review a judgment

prohibiting exclusion of Negroes from a municipal golf course (Hol

combe v. Beal, 347 U.S. 974).

11

tion purpose, cannot be deemed “ reasonable” regula

tions. They thus can claim no sanction under the

Court’s holding in Chiles.

D. The Segregation Regulations Offend Against the

Due Process Requirements of the Fifth Amend

ment, and Thereby Violate Section 3(1) of the Act

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497, held that to refuse

to admit Negro children, solely because o f their race,

to public schools in the District of Columbia attended

by white children is a denial of the due process of law

guaranteed by the Fifth Amendment. The Court said

(p. 499) that “ discrimination may be so unjustifiable

as to be violative of due process,” and that “ [C la ssi

fications based solely upon race must be scrutinized with

particular care, since they are contrary to our tradi

tions and hence constitutionally suspect.” The Court

further declared (p. 500) :

Segregation in public education is not reasonably

related to any proper governmental objective, and

thus it imposes on Negro children of the District

o f Columbia a burden that constitutes an arbitrary

deprivation of their liberty in violation of the Due

Process Clause.

Segregation in public transportation, that is, by com

mon carriers under duty both at common law and by

Federal statute to serve all persons without discrimina

tion, “ is not reasonably related to any proper govern

mental objective.” It follows that the segregation

which the defendant carriers impose on Negro pas

sengers “ constitutes an arbitrary deprivation of their

liberty in violation of the Due Process Clause.”

12

While the Fifth Amendment interdicts only action

by the Federal Government, the regulations of the de

fendant carriers are not exclusively the acts of private

parties. These regulations, now under challenge before

this Commission, can be maintained only with its sanc

tion. Henderson x. United States, 339 U. S. 816. Con

gress has clothed the Commission with wide regulatory

authority over the defendant carriers, and if the Com

mission should uphold the challenged regulations, this

would amount to action by the Federal Government

sufficient to make applicable the prohibitions of the

Fifth Amendment. See Public Utilities Commission v.

Poliak, 343 IT. S. 451, 462-463. It is settled that the

Fourteenth Amendment applies to “ State action of

every kind,” including state authority manifested by

“ judicial or executive proceedings.” Shelley v.

Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 14; Civil Fights Cases, 109 IT. S.

3,11,17. Certainly no narrower test is to be applied in

determining what constitutes Federal action for the

purposes of the Fifth Amendment.

Obviously, any segregation which operates to in

fringe constitutional rights subjects the persons whose

rights are infringed to “ undue or unreasonable prej

udice or disadvantage” , in violation o f Section 3(1) of

the Interstate Commerce Act.

I I

The Carriers’ Practices in Imposing Segregation Constitute a

Forbidden Interference With Interstate Commerce

The carriers involved in this proceeding do not rep

resent small local lines. They represent an entire sys

tem of transportation linking the South with the rest

of the country. The Atlantic Coast Line has a total

13

of 5,353 miles of track linking the East Coast to the

South and F lorida.7 The Southern Railway runs

through Ohio, Virginia, District of Columbia, Ken

tucky, and other Southern states.8 The Santa Fe op

erates in California, Arizona, New Mexico, Illinois,

Kansas, Colorado, and also Texas and Oklahoma.9 The

Gulf, Mobile and Ohio operates, inter alia, in Missouri,

Illinois, as well as Alabama and Louisiana.10 In short,

these carriers operate in states which by law require

segregation, others which by law forbid segregation,

and still others which have no laws on the subject. Cf.

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373, 382.

It is settled that a state may not either enforce or

forbid segregation for interstate passengers. In Hall

v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485, which dealt with a state statute

requiring public carriers to accord accommodations to

passengers “ without distinction or discrimination on

account of race,” the Court said (p. 489) that such a

statute would be “ productive of great inconvenience

and unnecessary hardship” since it would mean that,

under divergent state laws, ‘ ‘ on one side of a State line

its [the carrier’s] passengers, both white and colored,

must be permitted to occupy the same cabin, and on

the other be kept separate.” In Morgan v. Virginia,

328 U. S. 373, which involved a state statute requiring

the separation of white and colored passengers, the

Court said (p. 385) that the statute “ so burdens inter

state commerce or so infringes the requirements of na

7 Official Guide of the Railways, August, 1954, p. 576.

8 Id. (map), pp. 510-511.

9 Id. (map), pp. 938-939.

10Id. (map), pp. 632-633.

14

tional uniformity as to be invalid.” It also said (p.

386) :

It seems clear to us that seating arrangements

for the different races in interstate motor travel

require a single, uniform rule to promote and pro

tect national travel.

With one exception,11 each of the stipulations filed

in this proceeding states that the segregation enforced

by the carrier is pursuant to the public opinion, cus

toms or laws of one or more of the states through which

its trains operate. The effect is that, with reference

to the coaches or portions thereof which they may

occupy, interstate passengers are subjected to the local

mores or laws of the states through which they travel.

In short, as stated in Justice Frankfurter’s concurring

opinion in the Morgan case (328 U. S. at 388), inter

state commerce is unreasonably burdened by the “ im

position upon national systems of transportation of a

crazy-quilt of State laws,” some prohibiting and some

requiring racial segregation.

There is the same burden on interstate commerce, and

the same interferences with the Federal Government’s

paramount power over such commerce, whether en

forced separation of the races in interstate travel is

state-required or carrier-required. Indeed, it would be

a curious result i f private carriers were free to com

mand what a state, in the exercise of its broad police

power, is powerless to command. In fact, carrier rules

requiring segregation have been held invalid as applied

to interstate passengers, upon the ground that they un

reasonably interfere with interstate commerce. Chance

11 Louisville & Nashville Railroad’s stipulation.

15

v. Lambeth, 186 F. 2d 879 (C.A. 4), certiorari denied,

sub. nom., Atlantic Coast Lines, 341 U. S. 941; White-

side v. Southern Bus Lines, 177 F. 2d 949 (C.A. 6 ) ;

Carolina Coach Co. v. Williams, 207 F. 2d 408 (C.A. 4 ) ;

Solomon v. Pennsylvania R. Co., 96 F. Supp. 709 (S.D.

N .Y .). In the Chance case Judge Soper, speaking for

the court, said (186 F. 2d at 883) :

It is true that the regulation of the carrier was not

enacted by state authority, although the power of

the state is customarily invoked to enforce i t ; but

we know of no principle of law which requires the

courts to strike down a state statute which inter

feres with interstate commerce but to uphold a

railroad regulation which is infected with the

same vice.

A carrier’s power to promulgate regulations for the

carrying on of its business is limited to regulations

which are reasonable. Chiles v. Chesapeake & Ohio

Railway, 218 U. S. 71, 76. The defendant carriers’

regulations cannot be deemed reasonable since they de

stroy the uniformity held to be essential for the promo

tion and protection of interstate travel.

The defendants’ segregation regulations, being ob

structive of freedom of interstate travel, do not promote

“ efficient service.” But under the National Transpor

tation Policy declared by Congress this Commission is

required to administer the Interstate Commerce Act so

as to promote “ efficient service” in interstate transpor

tation. 12 Therefore, even apart from the requirements

of Section 3(1) of the Act, the Commission, in further

ance of the national policy which it is directed to en-

12 54 Stat. 899, 49 U.S.C., note preceding Section 1.

16

force, should strike down the segregation regulations.

Cf. United States v. Pennsylvania R. Co., 323 IT. S. 612,

616-617.

C O N C L U S IO N

The United States is of the view that “ the race of a

passenger may not legally constitute a basis for any d if

ferentiation or segregation in the course of interstate

travel upon a carrier subject to the provisions of the

Interstate Commerce A ct.” 13

As the Supreme Court has so recently ruled, enforced

separation of the white from the colored is generally

interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the latter.

Just as our “ Constitution is color-blind, and neither

knows nor tolerates classes among citizens,” 14 so too

is the Interstate Commerce Act. The time has come

for this Commission, in administering that Act, to de

clare unequivocally that a Negro passenger is free to

travel the length and breadth of this country in the

same manner as any other passenger.

H e r b e r t B r o w n e l l , J r .,

Attorney General.

S t a n l e y N. B a r n e s ,

Assistant Attorney General.

C h a r l e s H . W e s t o n ,

L a w r e n c e G o c h b e r g ,

Special Assistants to

the Attorney General.

13 Commissioners Aitchison, Cross, Lee and Mahaffie dissenting

in Henderson v. Southern Ry. Co., 284 I.C.C. 161, 165.

14 Mr. Justice Harlan, dissenting in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S.

537, 559.

☆ U. S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICEt I9B4 S 17515 411

'