Abrams v. Johnson Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

August 7, 1996

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Abrams v. Johnson Brief of Appellants, 1996. fd501ac0-ab9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f88b7d8c-0b61-4c49-a3ec-9a6c4d78a71d/abrams-v-johnson-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

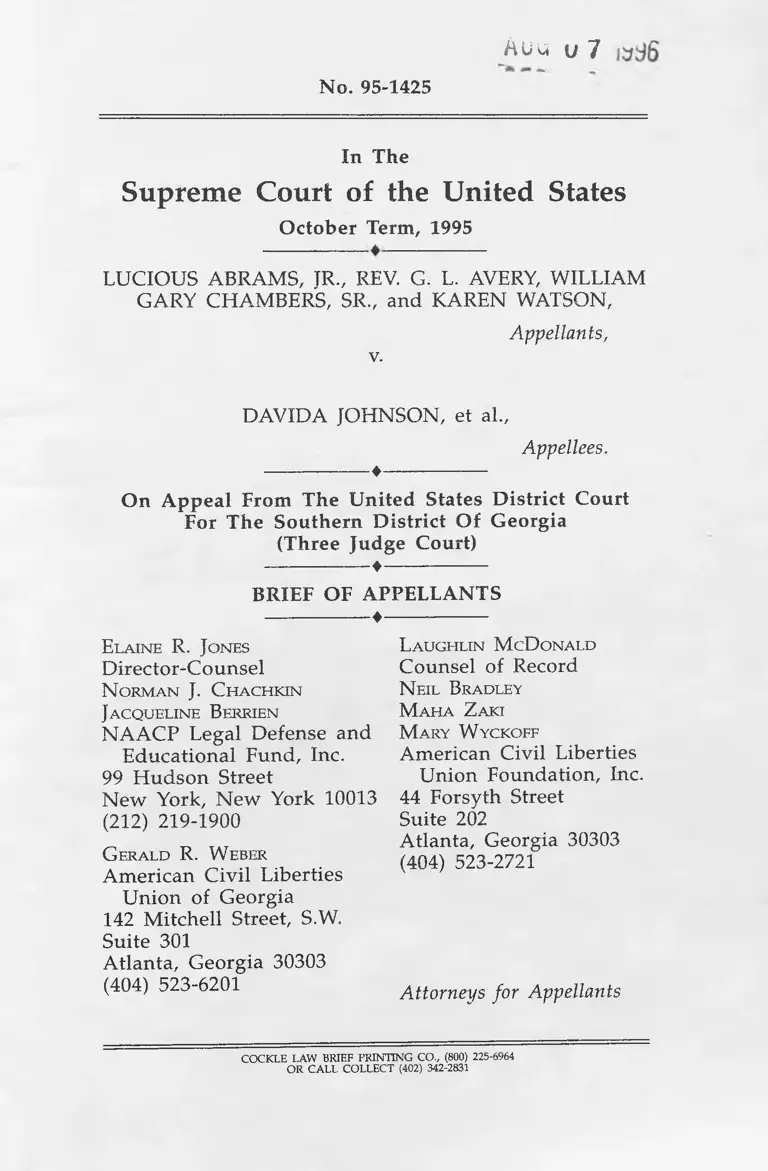

No. 95-1425

Auu u 7

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1995

LUCIOUS ABRAMS, JR., REV. G. L. AVERY, WILLIAM

GARY CHAMBERS, SR., and KAREN WATSON,

Appellants,

v.

DAVIDA JOHNSON, et al.,

Appellees.

-----------------♦ -----------------

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District Of Georgia

(Three Judge Court)

-----------------♦ -----------------

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

-----------------♦ -----------------

E la in e R. J o n es

Director-Counsel

N o rm a n J . C h a ch kin

J a cq u elin e B errien

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

G era ld R. W eber

American Civil Liberties

Union of Georgia

142 Mitchell Street, S.W.

Suite 301

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

(404) 523-6201

L a u gh lin M cD onald

Counsel of Record

N eil B ra dley

M a h a Z aki

M ary W ycko ff

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation, Inc.

44 Forsyth Street

Suite 202

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

(404) 523-2721

Attorneys for Appellants

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO., (800) 225-6964

OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the district court, in drawing a remedial

congressional redistricting plan, erred in disregarding the

state's legislative policy choices and making changes that

were not minimally necessary to cure the constitutional

defects in the existing plan?

2. Whether the court ordered plan, which frag

mented the black population in two majority black dis

tricts and dispersed it throughout the state, dilutes

minority voting strength in violation of Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act?

3. Whether the court ordered plan, which reduced

the number of majority-minority districts from three to

one, is retrogressive under Section 5 of the Voting Rights

Act?

4. Whether the court ordered plan, which contains

unnecessary population deviations, complies with the

one person, one vote standard of Article I, Section 2 of the

Constitution?

5. Whether the court erred in peremptorily barring

private intervention to defend the constitutionality of the

Second Congressional District although state officials did

not seriously contest plaintiffs' claims of invalidity nor

did they or the United States appeal the court's finding

that the Second District was unconstitutional?

ii

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING

The appellants are Lucious Abrams, Jr., Rev. G. L.

Avery, William Gary Chambers, Sr., and Karen Watson.

The appellees are Davida Johnson, Pam Burke, Henry

Zittrouer, George L. DeLoach, and George Seaton. The

defendants below were Zell Miller, Governor of Georgia,

Pierre Howard, Lieutenant Governor of Georgia, Thomas

Murphy, Speaker of the House of Representatives of

Georgia, and Max Cleland, Secretary of State of Georgia.

Max Cleland has been succeeded as Secretary of State by

Lewis Massey. The United States of America was a defen

dant intervenor.

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Pagc

Questions Presented i

Parties to the Proceeding ............... ............................... ii

Table of Authorities ......................................... ............... v

Opinions Below . ................ 1

Jurisdiction.................................................... 1

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved.. . . . . 1

Statement of the Case ................................. .................... 2

A. The Parties Below ........................- ........................ 2

B. Miller v. Johnson and Its Aftermath......... 2

C. The Remedy Phase ......................... 5

1. Appellants' Proposed Plans .............. 7

2. Other Proposed Plans. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

D. History of Discrimination.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

E. Racial Bloc Voting ......................................... • • • • 16

F. The Decision of the District Court ................... 19

Summary of Argument ............................................ 24

Argument............................................... 27

I. The District Court Abused Its Equitable

Powers.............................................................. 27

A. Ignoring District Cores . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

B. Maximum Disruption................. ........ . • • • 34

C. Destroying Majority Black Districts . . . . . 34

D. Unnecessary Speculation....................... 37

IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

Page

II. The Court's Plan Violates Section 2 ............... 40

A. No Deference Is Due the Court's Ruling .. 44

III. The Plan Is Retrogressive in Violation of Sec

tion 5 .............................................. ............. . 46

IV. The Plan Does not Comply with One Person,

One Vote ............................................................. .. 48

Conclusion ............................................... 50

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

C a ses :

Abrams v. Johnson, 116 S.Ct. 899 (1996)....................... 24

Abrams v. Johnson, No. 94-797................... 15, 17, 19, 21

Abrams v. Johnson, A-982 ................................................. 24

Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130 (1976).......... .46, 48

Burton v. Sheheen, 793 F.Supp. 1329 (D.S.C. 1992) . . . . 49

Bush v. Vera, 64 U.S.L.W. 4452 (1996) .................... 38, 42

Chapman v. Meier, 420 U.S. 1 (1975)............................. 28

City of Lockhart v. United States, 460 U.S. 125

(1983)................................. .......... ..................... .46, 47

Clark v. Roemer, 500 U.S. 646 (1991)........................... 48

Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407 (1977) .............28

DeWitt v. Wilson, 856 F.Supp. 1409 (E.D.Cal. 1994) . . . . 38

DeWitt v. Wilson, 115 S.Ct. 2637 (1995)......................... 38

Edge v. Sumter County School District, 775 F.2d

1509 (11th Cir. 1985)........................................................ 43

Growe v. Emison, 113 S.Ct. 1075 (1993) ....................... 28

Hastert v. State Board of Elections, 777 F.Supp. 634

(N.D.I11. 1991) ................................ ................................49

Holder v. Hall, 114 S.Ct. 2581 (1994)..................... . 47

Inwood Laboratories v. Ives Laboratories, 456 U.S.

844 (1982).........................................................................-45

Johnson v. De Grandy, 114 S.Ct. 2647 (1994)............... 44

Johnson v. Miller, Civ. No. CV194-008 (S.D.Ga.) . . . . . . 3

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Johnson v. Miller, 864 F.Supp. 1354 (S.D.Ga. 1994) passim

Jordan v. Winter, 541 F.Supp. 1135 (N.D.Miss.

1982).................................................. ................................. 43

Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725 (1983) . . . . . . 47, 48, 49

McDaniel v. Sanchez, 452 U.S. 130 (1981)............. . 46

Miller v. Johnson, No. 94-631 .......................................... 35

Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. 2475 (1995) . . . . . . . . . passim

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974)......... .27

Missouri v. Jenkins, 115 S.Ct. 2038 (1995)............... 27

Roman v. Sincock, 377 U.S. 695 (1964)............28, 33, 34

Shaw v. Reno, 113 S.Ct. 2816 (1993)............................. 31

SRAC v. Theodore, No. 92-155 (S.Ct.)............... 43

SRAC v. Theodore, 113 S.Ct. 2954 (1993)......... .43, 44

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) 41, 42, 43, 44

United States v. Johnson, No. 95-1460..................... 14, 49

Upham v. Seamon, 456 U.S. 37 (1982)

............... ............................................. 28, 29, 30, 37, 39, 48

Voinovich v. Quilter, 113 S.Ct. 1149 (1993).................. 42

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971)........27, 33, 39

White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783 (1973)............... 28, 29, 33

Winter v. Brooks, 461 U.S. 921 (1983)........................... 43

Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535 (1978)............... .......... 48

Zenith Radio Corp. v. Hazeltine Research, Inc.,

395 U.S. 100 (1969) ......................................................... 45

vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

C o n stitu tio n a l P ro v isio n s :

Article I, Section 2, Constitution of the United

States............................................................................... 1, 48

Article I, Section 4, cl. 1, Constitution of the

United States............................... 28

S tatutory P ro v isio n s :

28 U.S.C. §1253............................. 1

42 U.S.C. §1973, Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

............................ .................. . 1, 40, 42, 43, 45

42 U.S.C. §1973(b), Section 2(b) of the Voting

Rights Act ....................... 40

42 U.S.C. §1973c, Section 5 of the Voting Rights

A ct,.............................................. ........................ 1, 46, 48

O th er A u th o r ities :

Ga. Laws 1995, Ex. Sess., p. 1 .......................................... 2

S.Rep. No. 295, 94th Cong. 18-9 (1975)........... ........... 46

S.Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 28-9 (1982)..40, 41

Mike Christensen, "Reactions to the plan are all

over the map," Atlanta Journal Constitution,

December 14, 1995 ....................................................... 29

Jeff Dickerson, "At Christmas, black party loyalty

doesn't pay off," The Atlanta Journal, Decem

ber 20, 1995..................... .......... ................................... 29

Kevin Merida, "ACLU to Appeal Decision Remap

ping Ga. Districts," Washington Post, December

15, 1995 . ............................................................................ 29

V l l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Jeff Dickerson, "At Christmas, black party loyalty

doesn't pay off," The Atlanta Journal, Decem

ber 20, 1995 ...................................... . ............................ .29

Kevin Merida, "ACLU to Appeal Decision Remap

ping Ga. Districts," Washington Post, December

15, 1995 .............. .......................................... ............... 29

1

OPINIONS BELOW

The December 13, 1995 opinion of the three-judge

court for the Southern District of Georgia implementing a

court ordered redistricting plan for Georgia's congres

sional districts is unreported and appears at J.S.App. 1.

The August 22, 1995 order of the district court denying

intervention to defend the constitutionality of Georgia's

Second Congressional District is unreported and appears

at J.S.App. 42. The January 8, 1996 order of the district

court denying appellants' motion for a hearing and

reconsideration is unreported and appears at J.S.App. 44.

-----------------♦ -----------------

JURISDICTION

The opinion and order of the three-judge court for

the Southern District of Georgia was entered on Decem

ber 13, 1995. Appellants filed their notice of appeal on

January 11, 1996. J.S.App. 46. Probable jurisdiction was

noted on May 20, 1996. 64 U.S.L.W. 3773. The jurisdiction

of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. §1253.

---------------- ♦ -----------------

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The constitutional and statutory provisions involved

in the case are Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution of

the United States, and Sections 2 and 5 of the Voting

Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §§1973 and 1973c, the pertinent texts

of which are set out at J.S.App. 49-52.

---------------- ♦ -----------------

2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. The Parties Below. Appellants, who were defen

dant intervenors below ("Abrams interveners"), are a

group of black and white registered voters and residents

of Georgia's Eleventh Congressional District. Appellees,

plaintiffs below, are white residents of Georgia who chal

lenged the state's 1990 congressional redistricting on con

stitutional grounds. The defendants below were Zell

Miller, Governor of Georgia, Pierre Howard, Lieutenant

Governor of Georgia, Thomas Murphy, Speaker of the

House of Representatives of Georgia, and Max Cleland,

Secretary of State of Georgia. Max Cleland has been suc

ceeded as Secretary of State by Lewis Massey. The United

States of America was also a defendant intervenor.

B. Miller v. Johnson and Its Aftermath. In Miller v.

Johnson, 115 S.Ct. 2475 (1995), this Court held that Geor

gia's Eleventh Congressional District was unconstitu

tional because the state, absent a compelling reason for

doing so, had relied upon race as a predominant factor in

redistricting in substantial disregard of customary and

traditional districting practices. The redistricting plan

contained three majority black districts out of eleven, the

Second, the Fifth, and the Eleventh, but only the Eleventh

was challenged in the district court. Johnson v. Miller, 864

F.Supp. 1354 (S.D.Ga. 1994) (Johnson I), aff'd sub nom.

Miller v. Johnson. Blacks are 27% of the population of the

state of Georgia. J.S.App. 39.

After the decision in Miller v. Johnson the Governor

called the general assembly into special session to redis

trict the state's congressional districts. Ga. Laws 1995, Ex.

Sess., p. 1. The three-judge court conducted a hearing on

3

remand on August 22, 1995. It ruled that "Georgia has

until October 15th to enact a congressional reapportion

ment plan and have it precleared before this Court will

become vigorously active in handling the matter of rem

edy." Johnson v. Miller, Civ. No. CV194-008 (S.D.Ga.) Tran

script of Hearing, August 22, 1995, p. 110 ("T., Aug. 22,

1995").

The court also allowed the plaintiffs to amend their

complaint to add additional plaintiffs and to challenge

the constitutionality of the state's majority black Second

Congressional District. The court refused, however, to

allow appellants to defend the constitutionality of the

Second District and barred in advance any further inter

vention by private parties. The court ruled that:

The Abrams interveners will not participate

. . . in the evidentiary proceedings on the matter

of the constitutionality of the Second Congres

sional District of Georgia. It is our view that

there is no need for intervenors in this litigation.

The record is that the State of Georgia and its

elected officials will defend the congressional

districts that were enacted by the legislature to

the full extent of the law. We have seen that and

we expect that they will do that again and there

fore we see no need to have intervenors.

J.S.App. 42-3.

The general assembly remained in special session for

approximately a month. Defendant Murphy took the

position that "you ought to have two majority minority

seats in Georgia." Johnson v. Miller, Trial Transcript, Octo

ber 30, 1995, p. 433 (Testimony of Linda Meggers) ("T.,

Oct. 30, 1995"). The house, in fact, adopted a plan at the

4

special session that included two majority black districts,

the Fifth located in the metropolitan Atlanta area and

which had a 51.3% black voting age population (BVAP),

and the Eleventh (50.1% BVAP) located in the east central

part of the state. Status Report, Aug. 29, 1995 (Plan

MSLSS, August 25, 1995).

The senate passed a plan that contained only one

majority black district, the Fifth (51.5% BVAP). Status

Report of Defendants Miller, Howard, and Cleland. The

house and senate were unable to resolve their differences

in conference committee, and on September 13, 1995 the

defendants notified the court that the general assembly

had been unable to enact a congressional redistricting

plan and had adjourned. J.S.App. 2.

The court held a trial on the issue of the constitu

tionality of the Second Congressional district on October

30, 1995.1 Immediately after the trial, the court conducted

a hearing as to remedy instructing the parties "to assume,

arguendo at least, that the Second District may be

declared unconstitutional." T., Oct. 30, 1995, p. 5.

Prior to the October 30, 1995 trial, defendant Murphy

stipulated that the Second District "fails the constitu

tionality test as articulated by the Supreme Court." Joint

Stipulations of Fact and Statement of Issues Pertaining to

Plaintiffs' Challenge to Georgia's Second Congressional

District, stip. 108. The remaining state defendants did not

vigorously defend the constitutionality of the Second Dis

trict.

1 Appellants did not participate in that trial.

5

The state did not argue that a majority black Second

District was needed to eliminate the effects of past dis

crimination in voting, nor to comply with Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act. Johnson v. Miller, Order of December 1,

1995, slip. op. at 10, 12 ("Order, Dec. 1, 1995"). By their

own admission, "the State Defendants presented no wit

nesses and asked no questions of other witnesses at the

liability hearing." Response of Defendants Miller, How

ard and Cleland to 'Plaintiffs' Second Interim Petition for

Fees and Expenses/ p. 5.

The state's defense was that the Second District dif

fered from the Eleventh because the Second had always

existed in the southwestern corner of the State, there was

a greater community of interest in the Second District,

and the Second District had a lower percentage of black

voters. Order, Dec. 1, 1995, slip. op. at 10-1. The court

rejected these defenses concluding that "race was the

overriding and predominant motivating factor in design

ing the Second Congressional District," and the state

"fails to meet its burden under the strict scrutiny anal

ysis." Id. at 12.

The United States did not contest liability. The dis

trict court found that "[t]he Department of Justice con

tended that, as a matter of law, the Second District was

unconstitutional" in light of Miller v. Johnson. Order, Dec.

1, 1995, slip op. at 3 n.l.

The three-judge court declared the Second District

unconstitutional on December 1, 1995. J.S.App. 1-2. None

of the state defendants appealed the decision.

C. The Remedy Phase. Prior to the October 30, 1995

trial, the court entered two orders. The first instructed the

6

parties to submit "a plan that makes the least changes, in

terms of line drawing, in Georgia's present congressional

plan but at the same time brings the Eleventh and the

Second Congressional Districts . . . into compliance with

the United States Constitution." Order, October 17, 1995,

slip op. at 2-3. The second order directed the parties to

"further submit a plan based on the first plan that Geor

gia submitted to the Department of Justice [following the

1990 census] for preclearance." Order, October 20, 1995,

slip op. at 1. Despite the submission of least-change alter

natives by the parties and amici, the district court com

pletely redrew the congressional map of Georgia.

State defendants Miller, Howard, and Cleland

refused to submit or sponsor any plans, advising the

court that:

the Defendants do not know what the Constitu

tion now requires in terms of remedy. They do

not have a view of what plan might satisfy the

particular criteria set forth in the Court's orders.

For that reason, they are unable to submit what

the Court directs.

Submission of Defendants Miller, Cleland and Howard in

Connection with the Issue of Remedy, p. 2. Defendant

Howard, however, provided the court a copy of the redis

tricting plan that had passed the senate. Id.

Defendant Murphy submitted a plan which he said

"represents only his own opinion and beliefs as an indi

vidual public officer and not necessarily those of any

other member of the House of Representatives or the

House Democratic Caucus." Defendant Murphy's Rem

edy Submission in Response to Orders of October 17 and

20, 1995, p. 3. His plan created only one majority black

7

district, the Fifth (54% VAP). The Second District had a

black VAP of 36.8%, and the Eleventh District a black

VAP of 36.1%. Id.

Appellants, the United States, and amici incumbent

members of Congress (including Representatives John

Lewis and Newt Gingrich) submitted various remedial

plans. They are discussed below.

1. Appellants' Proposed Plans. Appellants submit

ted four plans prepared by their expert Selwyn Carter.2

One of the plans was a least-change plan (referred to as

ACLU1A), submitted at the direction of the district court,

designed to cure the constitutional defects in the existing

plan but at the same time make no more changes than

were necessary to accomplish that purpose. J.App.*

198-99.

In Miller v. Johnson this Court identified the manner

in which the state had unconstitutionally subordinated its

traditional redistricting principles to race in the construc

tion of the Eleventh District, i.e., "by extending the Elev

enth to include the black populations in Savannah;" by

splitting "Effingham and Chatham Counties . . . to make

way for the Savannah extension, which itself split the

City of Savannah;" by "splitting eight counties and five

municipalities along the way;" and, by using "narrow

corridors" to link "the black neighborhoods in Augusta,

Savannah and southern DeKalb County." 115 S.Ct. at

2484. The district court, in its December 1, 1995 opinion,

2 Mr. Carter, a specialist in redistricting, is the director of

voting rights programs for the Southern Regional Council, a bi-

racial organization in Atlanta, Georgia. T., Oct. 30, 1995, p. 294.

8

identified features of the Second District which it found

rendered it unconstitutional, i.e., "the sole reason for

splitting precincts was racial and . . . the predominant

reason for splitting . . . counties and cities was racial as

well;" and, the district "makes use of narrow land bridges

to connect parts of the district and involves a number of

irregular appendages." Order, Dec. 1, 1995, slip op. at 6.

In preparing appellants' least-change plan, Mr. Car

ter proceeded in light of this Court's findings with regard

to the Eleventh District and in anticipation of the findings

of the district court with regard to the Second District.

His "overriding methodology . . . was to correct the

constitutional defects in the Eleventh Congressional Dis

trict and assume that the Second Congressional District

was unconstitutional and correct . . . [the] assumed defect

in that district and to maintain the remaining districts

with as little change as possible." J.App. 161. He also

applied the redistricting principles embodied in the

state's prior plans, particularly the 1970 and 1980 plans.

Those principles included constructing districts with a

substantial number of counties, and which contained

both rural and urban areas. J.App. 165.

Mr. Carter removed the extensions of the Eleventh

District through Effingham and Chatham Counties

because they were identified by the Court as being

"examples of racial gerrymandering of the district."

J.App. 161. He regularized the configuration of Richmond

County "by bringing in a considerable number of white

voters previously in the Tenth District and transferring

them to the Eleventh District." J.App. 161. Richmond

County, an urban county, remained split under the least-

change plan but the split was not along racial lines. Id.

9

He reaggregated Baldwin, Twiggs, and Wilkes Coun

ties, portions of which had been placed in the Eleventh

District, and placed them in other districts. The reason for

the reaggregation was to "restore the integrity of those

rural political subdivisions and make the integrity of

those subdivisions predominant. Clearly here . . . an

attempt was made to draw a plan in which race was not

the predominant factor." J.App. 162.

He eliminated the narrow land corridor through

Henry County and included the county in its entirety in

the Eleventh District. J.App. 166. He also removed por

tions of DeKalb County from the Fifth District and placed

them in the Eleventh District so that the boundary

between the Fifth and the Eleventh Districts would be the

county line. J.App. 162-63, 170.

Under appellants' least-change plan, the Eleventh

District has a black VAP of 52.8%. J.App. 198. It is com

posed of 14 whole counties, and only the urban counties

of Richmond and DeKalb are split. J.App. 163.

A number of changes were similarly made in the

Second District. In Miller, this Court noted the criticism of

the district court that "[t]he black population of Mer

iwether County was gouged out of the Third District and

attached to the Second District by the narrowest of land

bridges." 115 S.Ct. at 2484. Accordingly, Mr. Carter reag

gregated Meriwether County and placed the county in its

entirety in the Seventh District. J.App. 174. Other coun

ties which had been split by the Second District - Low

ndes, Colquitt, Dougherty, Lee, Crisp, Dooly, Houston,

Bleckley, Twiggs, and Crawford - were also reaggregated.

10

Lowndes, Colquitt, Lee, Crisp, Houston, Bleckley, and

Twiggs were placed in the Eighth and Dougherty, Dooly,

and Crawford were placed in the Second. Again, the

reason for the reaggregation was to restore the integrity

of the rural counties and make their preservation a pre

dominant redistricting criterion. J.App. 168.

In order to comply with one person, one vote, Mr.

Carter moved Talbot County from the Second District to

the Third. J.App. 167, 170. The only counties split by the

Second District are Bibb and Muscogee, both of which are

urban. The county governments of both counties passed

resolutions requesting that the two counties be split

under any remedial plan to increase their representation

in Congress, a non-racial factor which Mr. Carter took

into account in drawing the Second District. J.App. 169.

In splitting Bibb County, Mr. Carter sought to elimi

nate a narrow land bridge into the city of Macon by

including a substantial number of white residents of the

city in the Second District. J.App. 168. The existing Sec

ond District also contains other urban areas, i.e., Col

umbus and Valdosta. Because the state "had historically

linked rural and urban areas together to form congres

sional districts," he kept these areas in appellants' least

change plan. J.App. 168, 170.

The changes in the remaining districts were those

minimally required by the changes in the Second and

Eleventh Districts. Because Effingham and Chatham

Counties were placed in the First District, Montgomery,

Tattnall, and Toombs Counties were taken out of the First

11

and placed in the Eighth District to comply with one

person, one vote. Clinch County was moved from the

Eighth to the First, also to comply with one person, one

vote. J.App. 166-67. There are no split counties in the First

District. Id.

Baldwin County was reaggregated and added to the

Third District, together with Talbot County, to comply

with one person, one vote. J.App. 170. Portions of Clay

ton County that had been in the Third were, as noted

above, placed in the Fifth District to comply with one

person, one vote, and to avoid retrogression. J.App. 170.

There are eleven intact counties in the Third, and the only

split counties are the urban counties of Bibb, Muscogee,

and Clayton. J.App. 170-71. Maintaining the integrity of

counties was the predominant factor in the construction

of the district, as it was in the construction of the plan as

a whole. J.App. 171.

Changes in the Fourth District were minimal. They

involved switching precincts between the Fourth and

Tenth Districts and precinct changes in DeKalb County to

comply with one person, one vote. J.App. 171.

In the Fifth District, portions of Clayton County were

added to compensate for the portions of DeKalb County

previously in the Fifth that were moved to the Eleventh

to make the DeKalb/Fulton County line the boundary

between the two districts. J.App. 172-73. The part of

Clayton County that was added contained enough black

population to avoid retrogression in the majority black

Fifth District, but was whiter overall than the part of

DeKalb County that was taken out. J.App. 170, 173. Por

tions of northern Fulton County were moved to the

12

Fourth District to comply with one person, one vote, and

also to avoid retrogression in the Fifth District. J.App.

173.

The changes in the Sixth District were also minor.

They involved a handful of precinct changes in Gwinnett

and Cobb Counties to comply with one person, one vote.

J.App. 173.

The principal change in the Seventh was the addition

of Meriwether County from the Second District, along

with minor precinct changes involving Cobb County,

again to comply with one person, one vote. J.App. 174.

In the Eighth District changes were made because of

changes in other districts, to comply with one person, one

vote, and to keep counties intact. J.App. 174-75. Mont

gomery, Toombs, and Tattnall Counties, formerly in the

First District, were added to the Eighth. Clinch County

was excluded, as was the previous extension into Bibb

County. J.App. 175.

There were no changes in the Ninth District. J.App.

175. In the Tenth District, Wilkes County was reaggre

gated and added. A portion of Richmond County, which

was heavily white, was moved to the Eleventh District,

and there were a few precinct changes in Gwinnett

County. All of these changes were made to comply with

one person, one vote. J.App. 175-76.

None of the rural counties outside the metropolitan

Atlanta area were split in the least-change plan. J.App.

176. A total of nine counties were split, all in urban areas

of the state. The court ordered plan split six urban

counties. J.S.App. 15. As the district court found, "[gjiven

13

the population density of those counties, it would be

impossible to avoid splitting any counties." J.S.App. 15

n.12.

Under appellants' least-change plan the Fifth District

contained a black VAP of 54.3%, and the Second a black

VAP of 45.5%. All the districts were contiguous, were

based upon the state's traditional redistricting principles,

were reasonably compact, and cured the constitutional

defects identified by this Court.

The total deviation among districts in appellants'

least-change plan was 0.93%, but the deviation could

have been lowered with the splitting of additional coun

ties. According to Mr. Carter, "if you draw a plan at a

lower level of geography you can get more precise and

bring the deviations down to almost zero if you want."

J.App. 164.

Appellants also tendered three other plans. J.App.

141-51. One of the plans, designated as Plan A, contained

three majority black districts, had a total deviation among

districts of 0.29%, but split more counties that ACLU1A.3

J.App. 194-95. Plan C, which contained two majority

black districts, split fewer counties than Plan A but as a

result contained a greater total deviation, i.e., 0.99%.

J.App. 197.

3 In preparing the joint appendix, appellants discovered

that in Plan A a small area in the Ninth District was misallocated

to the Tenth District. The misallocation can be easily corrected

and the correction does not affect the total deviation among

districts.

14

2. Other Proposed Plans. A plan containing two

majority black districts, known as Amicus R, was submit

ted by Congressmen John Lewis and Newt Gingrich.

J.App. 204. It made minimal changes in the First, Third,

Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, Ninth, and Tenth Districts,

and only those required to comply with one person, one

vote, and cure the constitutional defects identified in the

Second and Eleventh Districts. T., Oct. 30, 1995, pp.

356-57. Counties were reaggregated (seven remained

split) and appendages were removed. The Amicus R plan

was also designed to be a minimal disruption plan in the

sense that it did not create "any incumbent contest and it

leaves an identifiable representative in each district." T.,

Oct. 30, 1995, p. 360. The plan was a "consensus" plan

and had the support of ten of the eleven members of the

state's congressional delegation. T., Oct. 30, 1995, p. 364.

The United States also submitted a plan, known as

the Illustrative Plan, to show that a remedial plan could

be drawn which created two compact majority black dis

tricts and contained minimal population deviations.

United States v. Johnson, No. 95-1460, J.S.App. 44a. The

plan split only two counties outside the metropolitan

Atlanta area, Bibb and Muscogee, and contained a total

deviation of 0.19%, the lowest deviation of any of the

plans submitted to the district court. The black VAP in

the Second District was 42%, the black VAP in the Fifth

District was 53.7%, and the black VAP in the Eleventh

District was 51%. United States v. Johnson, J.S.App. 45a.

D. History of Discrimination. The record of the trial

in Johnson I involving the Eleventh District was made part

of the record of the trial involving the Second District.

Order, Dec. 1, 1995, slip op. at 4 n.2. In Johnson I the

15

district court found that the history of discrimination in

voting and other areas "against black people in the State

of Georgia need not be presented for purposes of this

case." Abrams v. Johnson, No. 94-797, J.S.App. 119; Johnson

I, Trial Transcript, Volume V, p. 142 (Johnson I, T.Vol.). The

court took judicial notice that:

Georgia's history on voting rights includes

discrimination against black citizens. From the

state's first Constitution - which barred blacks

from voting altogether - through recent times, the

state has employed various means of destroying

or diluting black voting strength. For example,

literacy tests (enacted as late as 1958) and prop

erty requirements were early means of exclud

ing large numbers of blacks from the voting

process. Also, white primaries unconstitu

tionally prevented blacks from voting in pri

mary elections at the state and county level.

Even after black citizens were provided

access to voting, the state used various means to

minimize their voting power. For example, until

1962 the county unit system was used to under

mine the voting strength of counties with large

black populations. Congressional districts have

been drawn in the past to discriminate against

black citizens by minimizing their voting poten

tial. State plans discriminated by packing an

excessive number of black citizens into a single

district or splitting large and contiguous groups

of black citizens between multiple districts.

Abrams v. Johnson, No. 94-797, J.S.App. 119-20 (emphasis

added).4 See also Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. at 2500-02

4 This history and its continuing effects are set out in

greater detail in the stipulations of the parties. See, e.g., Johnson

16

(noting the history of discrimination and denial of "equal

voting rights" in Georgia) (Ginsburg, J., dissenting).

E. Racial Bloc Voting. There was substantial evi

dence of racial bloc voting. The experts who testified

were in agreement that voting in Georgia is racially

polarized. Dr. Allan Lichtman, an expert for the United

States, examined more than 300 elections spanning an

approximately 20-year period. Johnson I, T.Vol.V,200. He

used the standard statistical techniques of ecological

regression and extreme case analysis, and examined four

sets, or levels, of black/white contests: (1) county level

contests throughout the state; (2) county level contests

within the Eleventh and Second Districts; (3) six state

wide elections partitioned within the boundaries of the

Eleventh and Second Districts; and, (4) the 1992 Eleventh

and Second District elections. Johnson I, Department of

Justice Exhibits 24, 41 (Johnson I, DOJ Ex.); T.Vol.V,199.

As for level one, Dr. Lichtman's analysis showed

"strong" patterns of racial bloc voting, with blacks and

whites voting " overwhelmingly" for candidates of their

own race. Johnson I, DOJ Ex. 24 at 7-8. Level two and

three analysis also showed "strong" patterns of racial

bloc voting. Id. at 8-9; T.Vol.V,202-03. In five of the six

statewide contests in the Eleventh District, at least 89% of

I, Stips. 5 (whites registered in 1992 at 70.2% of voting age

population; blacks at 59.8%), 76-103 (detailing the history of

discrim ination in voting), 104-129 (describing segregation in

educational institutions), 130-134 (noting other forms of racial

d iscrim ination), 135-55 (stip ulating to racial d isparities in

in com e, ed u catio n , u nem p loym ent, and p ov erty sta tu s).

Abrams v. Johnson, No. 94-797, J.App. 9-33.

17

blacks voted for black candidates, and at least 74% of

whites voted for white candidates. Johnson I, DOJ Ex. 24,

at 9. The exception to the pattern was the 1992 Demo

cratic primary for labor commissioner in which the black

candidate got 45% of the white vote, and 96% of the black

vote. In the ensuing primary runoff the black candidate

got only 26% of the white vote, and 92% of the black vote.

Id. at 14; J. App. 66-71.

The 1992 primary and runoff in the Eleventh District

were also racially polarized. In the primary, which

involved one white and four black candidates, the white

candidate, DeLoach, was the first choice among whites

with 45% of the white vote. Cynthia McKinney, who was

the leading vote getter over all, was second among whites

with 20% of the white vote. Johnson I, DOJ Ex. 24 at 17;

Abrams v. Johnson, No. 94-797, J.App. 22. In the run-off,

whites increased their support of DeLoach to 77%.

McKinney's white vote support increased to just 23%. Id.

Dr. Lichtman found voting patterns to be different in

statewide non-partisan judicial elections in which

appointed blacks ran as incumbents. He included these

contests in his report but treated them as having "mini

mal relevance." Johnson I, T.Vol.V,228.

With the exception of judicial elections in which

blacks were first appointed and ran as incumbents, no

black has ever been elected to a statewide office in Geor

gia. Johnson I, T.Vol.VI,77. No black, other than Andrew

Young, has ever been elected to Congress from Georgia

from a majority white district. Johnson I, Stip. 241.

Dr. Lichtman also testified that blacks have a lower

socio-economic status than whites which was a barrier to

18

blacks' participation in the political process. Johnson I,

T. Vol.V,206. In the 1988 and 1992 presidential elections,

black turnout was 14-15% lower than white turnout. Id. at

208. In the 1992 elections in the Eleventh District, blacks

were 51.5% of all voters in the primary, but only 46-47%

of voters in the runoff. Id. at 212-13; J. App. 77-8.

The state's expert, Dr. Joseph Katz, performed an

independent homogeneous precinct analysis to estimate

"average racial voting patterns." Johnson I, Defendants

Exhibit 170; T.Vol.V,48,81. He agreed that "[wjhites tend

to vote for white candidates and blacks tend to vote for

black candidates." Johnson I, T.Vol.V,84. He concluded

that whites vote for white candidates in the range of

71-73%. Id. He did not believe a black candidate had an

even (50%) chance to win until a district contained at

least 50% of black registered voters. Id. at 84-5. Dr. Katz

also found judicial elections to be "materially different"

and that it would be "inappropriate" to use them in

determining voting patterns in congressional elections.

Id. at 74, 83.

The plaintiffs' expert, Dr. Ronald Weber, agreed there

was "some evidence" of racial polarization in voting.

Johnson I, T.Vol.IV,259. Taking into account judicial elec

tions involving appointed black incumbents, he did not

think the racial bloc voting was "very strong." Id. at 324.

Of the 40 black members of the Georgia general

assembly, only one was elected from a majority white

district. Johnson I, T.Vol.IV,236; J.A. 26-7. Of the 31 black

members of the house, 26 were elected from districts that

were 60% or more black. Of the nine black members of

the senate, eight were elected from districts that were

19

60% or more black. Johnson I, Abrams Exhibits 23-4;

T.Vol.VI,208; DOJ Ex. 57; T.Vol.VI,204. While only one

black was elected from a majority white district, whites

won in 16 (29%) of the 55 majority black house and senate

districts. Abrams v. Johnson, No. 94-797, J.App. 26-7.

F. The Decision of the District Court. The court

issued its plan on December 13, 1995 (Judge Edmondson

dissenting). The district court, in its own words, pro

ceeded as if the state had adopted "no plans." J.S.App. 7.

According to the court,

Georgia's current congressional plan cannot

form the basis for the remedy we now construct

because it does not represent the goals of Geor

gia's historic policies nor the state legislature's

true intent.

J.S.App. 4. Also see J.S.App. 5 ("we cannot use Georgia's

current plan as a surrogate for the legislature's reappor

tionment policies and goals"), J.S.App. 6 ("we are unable

to use Georgia's current plan as the basis for a remedy"),

J.S.App. 7 ("the Court's task is akin to those cases in

which states had no plans").

The district court was of the view that no deference

was due the existing plan because it was the product of

"Department of Justice [interference." J.S.App. 4. The

court said that "DOJ basically used the preclearance pro

cess to force Georgia to adopt the ACLU redistricting

plan and, in the process, subvert its own legislative pref

erences to those of the DOJ." J.S.App. 5. Accordingly, the

court was "not bound by Upham to make only minimal

changes to the current plan in fashioning a remedy."

20

J.S.App. 5-6. Adopting a remedy that would be "mini

mally disruptive to Georgia's current plan was not an

option." J.S.App. 29. Any remedy "would necessarily

have resulted in drastic changes." J.S.App. 6.

The court's plan eliminated two of the three majority

black districts in the existing plan, reducing the black

VAP in the Second District from 52.3% to 35.1%, and in

the Eleventh from 60.4% to 10.8%. Johnson I, 864 F.Supp.

at 1366 n.12. The black VAP in the remaining majority

black district, the Fifth, was increased from 53% to 57.2%.

J.S.App. 16.

The court refused to draw a second majority black

district because in its view "Georgia's minority popula

tion is not geographically compact." J.S.App. 22. The

court conceded, however, that:

If Georgia had a concentrated minority popula

tion large enough to create a second majority-

minority district without subverting traditional

districting principles, the Court would have

included one since Georgia's legislature proba

bly would have done so.

J.S.App. 22 n.16.

In concluding that blacks were not geographically

compact, the court failed to discuss the remedial plans

proposed by appellants and the amici. The court dis

missed the Illustrative Plan proposed by the United

States because it allegedly split "numerous counties out

side the metropolitan Atlanta area." J.S.App. 8, n.4. As

noted supra, the Illustrative Plan in fact split only two

counties outside the metropolitan Atlanta area.

21

The court's findings regarding the existence of racial

bloc voting were contradictory. On the one hand, the

court held that "while some degree of vote polarization

exists, it is 'not in alarming quantities.' Johnson I, 864

F.Supp. at 1390." J.S.App. 23. For that reason, "the rem

edy we now impose meets the requirements of Section 2

without containing two majority-minority districts."

J.S.App. 24.

On the other hand, the court held that "Section 2 of

the VRA required the Court to maintain the Fifth District

as a majority-minority district." J.S.App. 18. Because of

racial bloc voting "based on statewide figures," J.S.App.

26 n.18, a district containing "the percentage of black

registered voters as close to fifty-five percent as possible

was necessary . . . to avoid dilution of the Fifth District

minorities' rights." J.S.App. 26. The plan adopted by the

court thus preserved the Fifth District as a majority-

minority district. At the same time, the black population

in the Second and Eleventh Districts was dispersed

throughout the state into other districts. The black VAP

was increased in the First District from 20.3% to 27.7%, in

the Third from 16.3% to 22.5%, in the Fourth from 10.8%

to 32%, in the Eighth from 18.4% to 28.3%, and in the

Tenth from 16.5% to 34.5%. Abrams v. Johnson, No. 94-797,

J.App. 20; J.S.App. 39.

The court's plan relocated the Eleventh District,

which under all its prior configurations ran from South

DeKalb County to the southeast, and put it "in the North

east Atlanta corridor" where it would have an "urban/

suburban flavor," J.S.App. 13-4, and be "a 'radius' district

reaching from suburban Atlanta to the state line."

J.S.App. 14. The justification for the relocation was that

22

this was an area containing a "community of interests"

and "where future growth is anticipated." J.S.App. 13-4.

The Eleventh District was also structured around "Inter

state Eighty-Five as a very real connecting cable."

J.S.App. 14.

The court substantially reconfigured the Third,

Eighth, and Tenth Districts as well. Under the prior plan

the Third District was located essentially in the center of

the state. Abrams v. Johnson, No. 94-797, J.App. 51. The

court's plan moved it to the western edge of the state.

J.S.App. 41. The new Tenth District was relocated south to

fill the void left by moving the Eleventh to the northeast

Atlanta corridor. Id. Under the court's plan the Eighth

District runs from the Florida line north to metropolitan

Bibb County and thence further north to the suburbs of

Atlanta, including in a single district the metropolitan

hub counties of Lamar, Upson, and Monroe with the

rural, south Georgia counties of Echols, Clinch, and

Charlton. Id.

The court's plan moved a total of 2,020,820 people -

31.2% of the state's population - into new congressional

districts. Abrams Intervenors' Motion for Hearing and for

Reconsideration, Declaration of Linda Meggers. By con

trast, appellants' proposed least-change plan (ACLU1A)

moved only 784,531 people into new districts, or 12.1% of

the population of the state. Abrams Intervenors' Mem

orandum in Response to Submission of Additional Demo

graphic Evidence by Defendants Miller, Howard &

Cleland, November 27, 1995 letter from Linda Meggers.

23

In devising its plan the court, by its own admission,

"subordinated" protection of incumbents "to other con

siderations." J.S.App. 18. It moved the incumbent in the

Eleventh District to the Fourth District, the incumbent in

the Second District to the Third District, and the incum

bent in the Eighth District to the Second District. The

effect of these changes was to create potential contests

between incumbents in Districts Three and Four. J.S.App.

18-9. Two of the three dislocated incumbents were black,

and only these two were placed in new districts with

other incumbents.

The court's plan contained a total deviation among

districts of 0.35%. J.S.App. 39. As noted supra, alternative

plans proposed by the parties contained lower devia

tions, i.e., the Illustrative Plan proposed by the United

States with a deviation of only 0.19%, and appellants'

ACLU1A plan with a deviation of 0.29%.

The district court justified the deviation in its plan by

deferring to the state's preference "for not splitting coun

ties outside of the metropolitan area," J.S.App. 8, and

because it wished to maintain "communities of interest."

J.S.App. 11. In addition, the court noted that "no precise

count of a district's population can be made using 1900

data." J.S.App. 12.

Judge Edmondson did not file a written dissenting

opinion. During the August 22, 1995 hearing, however, he

indicated in comments from the bench that the duty of a

federal court was "in each instance to make the least

amount of changes, the fewest amounts of changes, and

the least dramatic changes, possible" to bring a plan into

compliance with the Constitution. T., Aug. 22, 1995, p. 29.

24

In his view, the court did not have a license to "just

redraw Georgia." Id. at 36.

On January 8, 1996 the court denied appellants'

motion for reconsideration and an evidentiary hearing to

challenge the court ordered plan. Appellants filed their

notice of appeal on January 11, 1996. J.S.App. 46. The

district court denied appellants' application for a stay

pending appeal on January 26, 1996. This Court denied

appellants' application for a stay on February 6, 1996.

Abrams v. Johnson, 116 S.Ct. 899 (1996). After noting prob

able jurisdiction, the Court denied appellants' renewed

application for a stay on June 7, 1996. Abrams v. Johnson,

A-982.

-----------------♦----------- -

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The district court abused its equitable powers in

completely redrawing the congressional map of Georgia.

The powers of the federal courts must be adequate to the

task of fashioning remedies for violations, but those

powers are limited. Any remedy must be related to the

conditions that are found to offend the Constitution.

In the area of redistricting, deference by federal

courts to state policy choices is especially compelling.

That is true because the states have primary respon

sibility for apportionment. When a district court must act

in the legislature's stead, it must accomplish its task

circumspectly, and in a manner that is free from any taint

of arbitrariness or discrimination.

25

The district court ignored the state's traditional inter

est in preserving the core of existing districts. It com

pletely relocated the Eleventh District and placed it in the

northeast Atlanta corridor because it felt that was a better

location for the district. The court also drastically recon

figured other districts, including the Third, the Eighth,

and the Tenth.

The court's plan moved incumbents and pitted them

against each other in a number of districts in disregard

for the state's traditional policy of avoiding contests

between incumbents. Two of the three dislocated incum

bents were black, and only these two were placed in new

districts with other incumbents.

The court's plan shifted nearly a third of the state's

population into new districts. Least-change plans pro

posed by the parties and amici showed that it was possi

ble to draw far less disruptive plans that at the same time

cured the constitutional defects in the prior plan.

The court eliminated two of the three majority black

districts in the existing plan, despite its acknowledgment

of the legislature's decision to create a second majority

black district after the 1990 census. The court's justifica

tion for refusing to draw a second majority black district

was that Georgia's minority population was not geo

graphically compact. The legislature, however, in enact

ing its first plan was of the view that the black population

was sufficiently compact to constitute a majority in a

second congressional district.

Proposed remedial plans were also submitted by the

parties and amici which showed that a compact second

majority black district can be drawn in Georgia while

26

adhering to the state's traditional districting principles.

As long as a state does not subordinate traditional redis

tricting principles to race, it may intentionally create

maj ority-minority districts, and may otherwise take race

into consideration, without being subjected to strict scru

tiny.

The court's plan violates Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act. Blacks in Georgia are geographically compact.

As appears from various plans submitted to the district

court, it is clearly possible to draw two reasonably com

pact majority black congressional districts in the state.

Blacks are also politically cohesive, while their preferred

candidates are usually defeated by whites voting as a

bloc. As the lower court found, a district containing

approximately 55% of black registered voters was neces

sary to avoid dilution of minority voting strength.

The district court's plan is retrogressive in violation

of Section 5. The court's plan reduced the number of

majority black districts from the levels in the third legis

lative plan (which had three of eleven) and the first

legislative plan (which had two of eleven), to only one of

eleven in a state that is 27% black. Minorities admittedly

have fewer electoral opportunities under the court

ordered plan than under any of these pre-existing plans.

The court used the 1982 plan as a benchmark for

measuring retrogression. The 1982 plan was not only

malapportioned but contained ten districts while the 1992

plan contains eleven. The ten seat 1982 plan by definition

cannot serve as a reasonable benchmark by which to

evaluate the court's eleven seat plan. The most appropri

ate benchmarks for determining retrogression are either

27

the state's initial eleven seat plan containing two majority

black districts, or the state's policy and goal of creating

two majority black districts. Using either of these

benchmarks, the court ordered plan would violate the

retrogression standard of Section 5.

The court's plan does not comply with one person,

one vote. Congressional redistricting is held to even stric

ter standards than legislative redistricting. The total devi

ation among districts in the district court's plan is 0.35%.

Plans with lower overall deviations were submitted to the

court by the United States (0.19%) and by appellants

(0.29%). Other district courts have had no difficulty in

drafting or approving plans with zero deviations.

-----------------+-----------------

ARGUMENT

I. The District Court Abused Its Equitable Powers

The powers of the federal courts must be adequate to

the task of fashioning remedies for constitutional viola

tions, but those powers "are not unlimited." Whitcomb v.

Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 161 (1971). Any remedy must be

related to "the condition alleged to offend the Constitu

tion." Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 738 (1974). See

Missouri v. Jenkins, 115 S.Ct. 2038, 2058 (1995) (federal

courts do not have "a blank check to impose unlimited

remedies upon a constitutional violator") (O'Connor, J.,

concurring).

In the area of redistricting, deference by federal

courts to state policy choices is especially compelling.

That is true because "the Constitution leaves writh the

28

States primary responsibility for apportionment of their

federal congressional and state legislative districts."

Grows v. Emison, 113 S.Ct. 1075, 1081 (1993). See Art. I, § 4,

cl. 1, Constitution of the United States ("[t]he Times,

Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and

Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the

Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by

Law make or alter such Regulations"). See also Chapman v.

Meier, 420 U.S. 1, 27 (1975).

While an elected legislature is situated to identify

and reconcile traditional state policies, "[t]he federal

courts by contrast possess no distinctive mandate to com

promise sometimes conflicting state apportionment poli

cies in the people's name." Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407,

415 (1977). When a district court must act in the legisla

ture's stead, its "task is inevitably an exposed and sensi

tive one that must be accomplished circumspectly, and in

a manner 'free from any taint of arbitrariness or discrimi

nation.' " Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. at 415, quoting Roman v.

Sincock, 377 U.S. 695, 710 (1964).

A court

should follow the policies and preferences of the

State, expressed in statutory and constitutional

provisions or in reapportionment plans pro

posed by the state legislature, whenever adher

ence to state policy does not detract from the

requirements of the Federal Constitution.

White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783, 795 (1973). Because states

derive their reapportionment authority from independent

provisions of state and federal law, "federal courts are

bound to respect the States' apportionment choices unless

those choices contravene federal requirements." Voinovich

29

v. Quilter, 113 S.Ct. 1149, 1157 (1993). The decisions and

judgments of a state legislature "in pursuit of what are

deemed important state interests . . . should not be

unnecessarily put aside in the course of fashioning

relief." White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. at 796.5

These principles are exemplified by Upham v. Seaman,

456 U.S. 37 (1982). There, the Attorney General objected

under Section 5 to two congressional districts in Texas.

The district court proceeded to resolve the objections to

the districts but in addition devised its own plan for four

5 One of the reasons federal courts should act

circumspectly and adhere to state legislative policy choices

where possible is to avoid even the appearance of partisan or

other bias. The "drastic changes" approach of the district court

in this case has, unfortunately, given rise to speculation that the

plan was driven by partisan bias favoring Democrats at the

expense of Republicans. J.S.App. 6. See Jeff Dickerson, "At

Christmas, black party loyalty doesn't pay off," The Atlanta

Journal, December 20, 1995 ("The judges - both appointed by

Democrats, coincidentally - did away with two of the state's

three majority black districts, balkanizing the black vote in a

way that benefits white Democrats"); Kevin Merida, "ACLU to

Appeal Decision Remapping Ga. Districts," Washington Post,

December 15,1995 (quoting the chair of the Georgia Democratic

Party that "[tjhe changes that were made favored us in virtually

every district"); Mike Christensen, "Reactions to the plan are all

over the map," Atlanta Journal Constitution, December 14,1995

(quoting Rep. John Linder that " ' [i]t appears that the two

Democratic judges tried to draw a map for white

Democrats . . . [wjhat [Georgia House Speaker] Tom Murphy

couldn't get done on the floor of the Legislature he got the

judges to do for him' "). Public trust and confidence in the

impartiality of the judiciary cannot but be undermined by the

unnecessary breadth of the redistricting by the district court in

this case.

30

other districts as to which there had been no objection.

456 U.S. at 40. In vacating the decision, the Court noted

that "[t]he only limits on judicial deference to state

apportionment policy . . . were the substantive constitu

tional and statutory standards to which such plans are

subject." 456 U.S. at 42. In fashioning a court ordered

remedy, therefore, a district court may not reject state

policy more than is necessary "to meet the specific consti

tutional violations involved." Id. In remanding the case

for further proceedings, the Court concluded that:

Whenever a district court is faced with entering

an interim reapportionment order that will

allow elections to go forward it is faced with the

problem of 'reconciling the requirements of the

Constitution with the goals of state policy.' Con

nor v. Finch, supra, at 414, 97 S.Ct. at 1833. An

appropriate reconciliation of these two goals can

only be reached if the district court's modifica

tions of a state plan are limited to those neces

sary to cure any constitutional or statutory

defect. Thus, in the absence of a finding that the

Dallas County reapportionment plan offended

either the Constitution or the Voting Rights Act,

the District Court was not free, and certainly

was not required, to disregard the political pro

gram of the Texas State Legislature.

456 U.S. at 43.

In light of Upham, the district court's remedial

powers in this case were limited to curing any constitu

tional defects in the Second and Eleventh Districts. Far

from following Upham, the district court redrew the entire

congressional map for the state of Georgia, proceeding by

31

its own admission as if the state had adopted "no plans."

J.S.App. 7.

A. Ignoring District Cores. The district court

ignored the state's traditional, longstanding, and explic

itly articulated interest of "preserving the core of existing

districts." Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. at 2483. It completely

relocated the Eleventh District and placed it "in the

Northeast Atlanta corridor out to the northeast Georgia

state line," where it would have an "urban/suburban

flavor." J.S.App. 13-4. The court justified this new loca

tion of the district on the grounds that it was in an area of

anticipated future growth, and "[t]he road net, the area's

commerce, its recreational aspect, and other features pro

duce a district with a palpable community of interests."

J.S.App. 14. Even assuming all of that to be true, it

provides no basis for the court substituting its own judg

ment for that of the legislature about where the district

should be located in the state, particularly where a dis

trict can be drawn southeast from South DeKalb County

that cures the constitutional defects identified by the

Court and which is based upon the state's traditional

redistricting principles.

Elaborating on its "road net" rationale for relocating

the Eleventh District, the district court explained that the

new district follows a progression of counties that "have

Interstate Eighty-Five as a very real connecting cable."

J.S.App. 14. Ironically, it was the configuration of the

Twelfth Congressional District in North Carolina along

the very same interstate that drew the sharpest criticism

of that district. See Shaw v. Reno, 113 S.Ct. 2816, 2821,

2825, 2832 (1993) (describing the Twelfth District as being

"unusually shaped," "bizarre on its face," and "irrational

32

on its face" because for much of its length it closely

followed "the 1-85 corridor"). Constructing a district

along a major highway can, therefore, depending on the

redistricting outcome one favors, be evidence of bizarre

ness and irrationality, or "a very real connecting cable."

J.S.App. 14.

As the court's "road net" analysis demonstrates, a

resourceful map maker can justify any plan, particularly

one drawn at the congressional level, based upon "com

munities of interests," including those similar to or differ

ent from the ones identified by the district court. It would

be quite impossible to draw a district in Georgia contain

ing some 589,000 people without including a substantial

number - or an infinity - of communities of interests, e.g.,

business people, working class families, poor people,

members of the middle class, church goers, sports fans,

high school graduates, high school dropouts, people and

neighborhoods concerned about crime prevention and

improving public education, or individuals and groups

concerned about the national debt, the space program,

international terrorism, and ethnic cleansing and geno

cide, etc. Certainly these "communities of interest" have

as much claim to congressional representation as an

area's "road net," or its "commerce," or its "recreational

aspect," communities of interest relied upon by the dis

trict court to justify its relocation of the Eleventh District.

J.S.App. 22.

In reality, "community of interests" is an amorphous

and illusive concept. One can define it in any way one

chooses, which is one reason why the federal courts

should leave the definition to state legislatures. Certainly

a federal court, whose equitable powers properly extend

33

only to curing identifiable constitutional and statutory

defects, has no warrant gratuitously to substitute its own

definition of what a community of interests is for that of

the legislature. White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. at 795 ("[i]n

fashioning a reapportionment plan or in choosing among

plans, a district court should not pre-empt the legislative

task nor 'intrude upon state policy any more than neces

sary' "), quoting Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. at 160. The

district court's choice of communities of interest was

exactly the arbitrariness that Roman v. Sincock, 377 U.S. at

710, forbade.

The district court also drastically reconfigured the

Third and Tenth Districts. It moved the Third District

from the center of the state to its western edge. It relo

cated the Tenth District, moving it south to fill the void

created by moving the Eleventh District to the Northeast

Atlanta corridor.

The court created an Eighth District that runs from

the Florida line to the metropolitan hub counties of

Lamar, Upson, and Monroe, and included in one sprawl

ing district the smallest county in the state, Echols (popu

lation 2,334), with one of the largest metropolitan

counties in the state, Bibb (population 149,967). To use the

words of this Court in invalidating the Eleventh, the

Eighth District includes areas that are "miles apart in

distance and worlds apart in culture." Miller v. Johnson,

115 S.Ct. at 2484. The Eighth is the kind of "geographic

monstrosity" criticized by the majority in Miller. Id.

The willingness of the district court to draw the kind

of districts in its own plan that both it and this Court

condemned in the plan drawn by the state indicates that

34

the district court applied a dual standard in redistricting.

Moreover, it is a dual standard that is impermissibly

based upon race, for it measures majority black districts

by one set of size and compactness criteria and majority

white districts by another. The use of such a dual stan

dard inevitable calls into question the "arbitrariness" of

the district court's plan, Roman v. Sincock, 377 U.S. at 710,

and contravenes the assurance given by this Court that

majority-minority districts are not to be treated "less

favorably" than those that are majority white. Miller v.

Johnson, 115 S.Ct. at 2497 (O'Connor, J., concurring).

B. Maximum Disruption. The court's plan moved

incumbents and pitted them against each other in a

number of districts, again in disregard for the state's

traditional and stated policy of "avoiding contests

between incumbents." Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. at 2483.

Two of the three dislocated incumbents were black, and

only these two were placed in new districts with other

incumbents.

The court's plan shifted nearly a third of the state's

population into new districts. Least-change plans pro

posed by the parties and amici showed that it was possi

ble to draw far less disruptive plans that at the same time

cured the constitutional defects in the prior plan. Abrams

Intervenors' Memorandum in Response to Submission of

Additional Demographic Evidence by Defendants Miller,

Howard & Cleland, November 27, 1995 letter from Linda

Meggers. Under appellants' ACLU1A plan, only 12.1% of

the state's population was placed in a different district.

C. Destroying Majority Black Districts. The court

also eliminated two of the three majority black districts in

35

the existing plan, despite its acknowledgment of the legisla

ture's decision to create a second majority black district after

the 1990 census. J.S.App. 22 n.16. The first plan enacted by

the legislature prior to any involvement by the Department of

Justice contained a second majority black district (the Elev

enth) running Southeast from DeKalb County. Miller v. John

son, 115 S.Ct. at 2483. That plan necessarily reflected the

legislature's, not DOJ's, reapportionment policies and goals.

In their brief in this Court in Miller v. Johnson, the state

repeatedly stressed "the undisputed consensus of all the

legislators involved - both white and black, Republican and

Democrat - that the first plan was reasonable." Miller v.

Johnson, No. 94-631, Brief of Appellant Miller et al., p. 18.

There is no evidence that the first plan was based predomi

nantly upon race or that the state subordinated its traditional

redistricting principles to race in the construction of the plan.

Again, in its brief, the state said that:

It is undisputed that the General Assembly as a

whole found the initial [1991 congressional redis

tricting] plan enacted to be reasonable. It was not

perceived as a 'racial gerrymander.' . . . There is, in

fact, no evidence that any legislator or reapportionment

staffer ever believed the initial plan to be offensive as a

racial gerrymander.

Miller v. Johnson, No. 94-631, Brief of Appellants Miller et al,

p. 49 (emphasis in original).

In addition, the plaintiffs in Miller v. Johnson, never

contended in the district court that the first or second con

gressional redistricting plans were unconstitutional, and

introduced no evidence that they were. In response to a

question from the district court, the plaintiffs' lawyer

responded that "I don't think that we have a position on the

36

first two plans because they never went to law." Johnson I,

T.Vol.11,23. Nor was there any finding by the district court

that the first plan enacted by the legislature was unconstitu

tional.

The record itself refutes any contention that the Eleventh

District was initially drawn "solely" on the basis of race. The

first plan excluded "a sizable black population in Baldwin

County," Johnson I, T.Vol.11,21 (Testimony of Linda Meggers),

as well as "a sizable black population of Chatham [County]".

Id. at 25. Had the construction of the Eleventh District been

driven solely by race it would have included these areas.

The speaker of the house said that the Eleventh District

as drawn in the first plan "suited me," was "obviously"

acceptable, and denied that it was "a racial gerrymander."

Johnson I, T.Vol.II,81. The chair of the house reapportionment

committee similarly testified that in enacting the first con

gressional plan, "[we] thought we had done pretty well."

Johnson I, T.Vol.HI,252 (Testimony of Bob Hanner). The state

complied with the Voting Rights Act, as well as followed its

traditional redistricting principles, i.e., "we kept cities and

counties intact." Id.

The court's justification for refusing to draw a second

majority black district was that "Georgia's minority popula

tion is not geographically compact." J.S.App. 22. The legisla

ture, however, in enacting its first plan was obviously of the

view that the black population was sufficiently compact to

constitute a majority in a second congressional district.

The state's demographer also testified that the Eleventh

District in the first plan contained fewer counties than many

other Georgia congressional districts, and in terms of its size

and length was "within the range of districts that the state

37

has created in the past." T., Oct. 30, 1995, p. 444. Proposed

remedial plans submitted by the parties and amici, e.g., the

Illustrative Plan, ACLU1A, and Amicus R, also showed that

a compact second majority black district can be drawn in

Georgia while adhering to the state's traditional districting

principles.

While this Court held in Miller that the legislature's third

post-1990 plan - adopted after the Attorney General refused

to preclear the first two plans - is unconstitutional, the Court

never held or suggested that the first plan is unconstitu

tional. The first plan enacted by the state was based upon the

state's traditional districting principles and would not trigger

strict scrutiny under Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. at 2497 ("[t]o

invoke strict scrutiny, a plaintiff must show that the State has

relied on race in substantial disregard of customary and

traditional districting practices") (O'Connor, J., concurring).

It was error for the district court to ignore the judgment of

the legislature, especially when, as noted infra, doing so

diluted the voting strength of a "community defined by

actual shared interests." Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. at 2475.

D. Unnecessary Speculation. The district court

attempted to distinguish Upham by claiming that the existing

plan "does not represent the goals of Georgia's historic

policies nor the state legislature's true intent." J.S.App. 4.

However, the "policies" and "true intent" of the state

were represented in the first plan enacted by the legisla

ture prior to any involvement by the Department of Jus

tice.

The district court's defense of its "drastic changes"

approach based upon speculation about what "the legis

lature might have done had it not been for the DOJ's

38

subversion of the redistricting process," J.S.App. 13, is

therefore misplaced. One does not have to resort to spec

ulation; in enacting the first plan, we know what the

legislature actually did. Unless the state's legislative pol

icy and goal of a second majority black district was

unconstitutional, the district court was not free to ignore