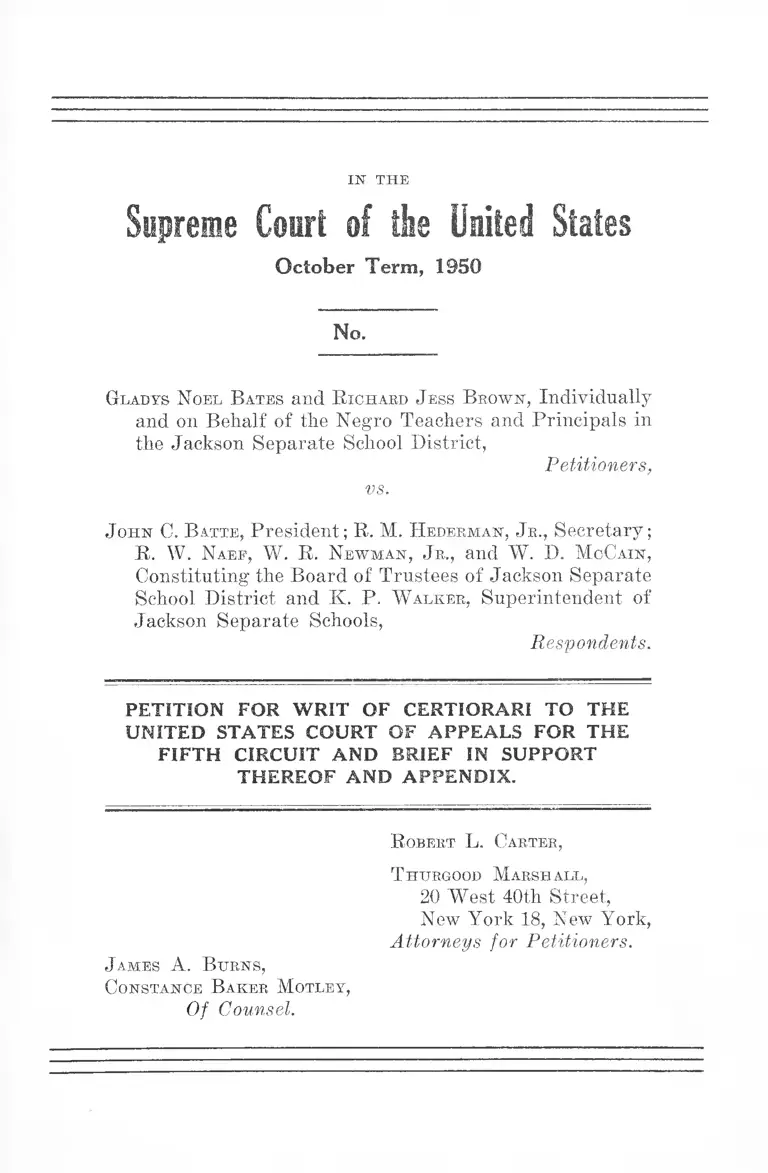

Bates v. Batte Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and Brief in Support Thereof and Appendix

Public Court Documents

May 15, 1951

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bates v. Batte Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and Brief in Support Thereof and Appendix, 1951. 9300c2ed-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f89b2d25-9b33-420c-ba39-98d23fcac180/bates-v-batte-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit-and-brief-in-support-thereof-and-appendix. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

IN TH E

Supreme Court of the United States

O ctober Term, 1950

No,

G ladys N oel B ates and R ichard J ess B ro w n , Individually

and on Behalf of the Negro Teachers and Principals in

the Jackson Separate School District,

Petitioners,

vs.

J o h n C. B a tte , President; R. M. H edekm an , J r ., Secretary;

R. \Y. N a ef , W . R. N e w m a n , J r,, and W . I). M cCa in ,

Constituting the Board of Trustees of Jackson Separate

School District and K. P. W a lk er , Superintendent of

Jackson Separate Schools,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

FIFTH CIRCUIT AND BRIEF IN SUPPORT

THEREOF AND APPENDIX.

R obert L. Carter ,

T htjrgood M arshall ,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, New York,

Attorneys for Petitioners.

J ames A. B u r n s ,

C onstance B aker M otley ,

Of Counsel.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

P etitio n for W r it op Certiorari

Summary Statement of the Matter Involved______ 2

Statement of F acts_________________________ 5

The Opinion of the Court of Appeals___________ 6

Jurisdiction ______________________________ 7

Questions Presented_________________________ 7

Reasons Relied Upon for Allowance of Writ------- 8

Conclusion ________________________________ 19

B r ie f in S u ppo rt T h er eo f

Opinion of the Courts Below---------------------------- 21

Jurisdiction ______________-________________ 22

Statement of the Case______________________ 22

Statement of the Facts_______________________ 22

Errors Relied Upon________________________ 22

A r g u m en t

I. The rule of exhaustion of administrative rem

edies was improperly applied to this case

A. It was not the intent of Congress that an

administrative agency have primary and

exclusive jurisdiction_______________ 23

B. The question to be decided is not one

which is within the peculiar competence

of an established administrative agency— 26

C. No jurisdictional prerequisites were pre

scribed by Congress________________ 27

11

PAGE

D. Exhaustion of the state administrative

remedies is not mandatory___________ 28

E. The state administrative agencies are

without authority and lack the power of

remedy___________________________ 28

II. This case is not governed by Cook v. Davis

(C. A. 5), 178 F. (2d) 595 (1949), cert, denied

340 U. 8. 811

A. The material facts in the Cook case____ 33

B. The material facts in the instant case____ 34

Conclusion________________________________ 37

Statutory A u th orities

U nited S tates C ode

Title 8, Section 43______________2, 8, 9,10,11,13,14,

15,16,17,18, 25, 29, 36

Title 28, Section 1254 ______________________ 7, 22

Title 28, Section 1343(3)____________ 2,8,9,10,11,15,

16,17,18, 25, 36

G eorgia C ode A nnotated

32-613 ____________________________________ 11

M is s issippi C ode (1942)

Section 6219 ______________________________ 34

Section 6234 ___________________________ 18, 29, 35

Section 6240-07 ____________________________ 35

Section 6261 ----------------------------------------- 18,29,35

Section 6423 _________________________ 35

Ill

O ther A u th orities

PAGE

Berger, Exhaustion of Administrative Remedies, 48

Yale L. J. 981 (1939)_______________________ 23

Congressional Globe, 42nd Congress, 1871, First Session,

Part 1, and Part 2, Appendix________________ 14, 25

Davis, Administrative Law Doctrines of Exhaustion of

Remedies, Ripeness for Review, and Primary Jur

isdiction, 28 Texas L. Rev. 168, 376 (1949)______23, 26

C aces C ited

Aaron, et al. v. Cook, U. S. D. C., N. D., Ga__________ 16

Aircraft & D. Equipment Corp. v. Hirsch, 331 U. S. 752

(1947) ___________________________________ 8,24

Alston v. School Board (C. A. 4), 112 F. (2d) 992

(1940), cert, denied 311 IT. S. 693_____________ 15, 32

Armour & Co. v. Alton R. R., 312 U. S. 195 (1941)

10,13, 24, 27

Bates & Batte (C. A. 5), 187 F. (2d) 142 (1951)______ 6

Board of Railroad Com’rs v. Great N. Ry., 281 IT. S.

412 (1930) __________________________ 10,13, 24, 27

Bottone v. Lindsley (C. A. 10), 170 F. (2d) 705 (1948)

10,14,15, 27

Briggs v. Elliott, U. S. D. C., E. D., S. C____________ 16

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, U. S, D. C.,

F. D., Kansas_____________________________ 16

Burt v. City of New York (C. A. 2), 156 F. (2d) 791

(1945) ___________ 14,16,17,25,27

Carter et al. v. School Board (C. A. 4), 182 F. (2d)

531 (1950) _____________________________16,17,27

Clark et al. v. Bd. of Trustees, 117 Miss. 234 (1918)......18, 28

IV

PAGE

Cook v. Davis (C. A. 5), 178 F. (2d) 595 (1949), cert.

den. 340 U. S. 811 (1950) ___ 3, 5, 6,11,12,13,16,17, 23,

33, 34, 35, 36

Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157 (1943)______10,15, 27

Federal Power Commission v. Arkansas Power & Light

Co., 330 U. S. 802 (1947)_____________________8, 24

Federal Power Commission v. Panhandle Eastern Pipe

Line Co., 337 U. 8. 496 (1949) _______________ 19, 29

First Iowa Hydro-Electric Cooperative v. Federal

Power Commission, 328 TJ. S. 152 (1946)______9,18, 28

First National Bank v. Albright, 208 U. S. 548 (1908)_ 23

Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U. S. 147 (1948)_______________ 17

Georgia v. Penn. R. B. Co., 324 U. S. 439 (1945)_____9,15,

19 24 26 29 39

Glicker v. Michigan (C. C. A. 6), 160 F. (2d) 96 (1947)

10 15 27

Great N. Ry. v. Merchants Elevator Co., 259 H. 8. 285,

290 (1922) -------------------------------------- 10,13,24,27

Hague v. C. I. O., 307 U. S. 496 (1939)__10,14,15, 25, 27, 29

Heard v. Ouachita Parish School Board (D. C. La.),

94 F. Supp. 897 (1951)________________________ 16, 27

Hillsborough v. Cromwell, 326 U. S. 620 (1946)._19, 24, 29

Hobbs v. Germany, 94 Miss. 469 (1909)______________ 18, 28

Johnson v. Board of Trustees (D. C. Ky.), 83 F. Supp.

707 (1949) _______________________________ _ 16

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 (1939)______________ 11

Cf. Levers v. Anderson, 326 U. 8. 219 (1945)______ 18, 28

Lopez v. Secumbe (D.C. Col.), 71 F. Supp. 769 (1944)_„_. 16

Maeauley v. Waterman Steamship Corp., 327 U. S.

540 (1946) ________________________________ 8, 24

Manchester v. Leiby, 117 F. (2d) 661 (1941) (C. C.

A. 1st) ------------------------------------------------10,16, 27

V

PAGE

Mitchell v. Wright (C. A. 5), 154 F. (2d) 924, cert. den.

329 U. S. 733 (1945) ________________________ 10

Moreau v. Grandich, 114 Miss. 5160 (1917)________ 18, 28

Moore v. Illinois Central Railway, 312 U. S. 630

(1941)__________________ _________________18, 28

Morris v. Williams, 149 F. (2d) 703 (1945)________ 14,15

Myers v. Bethlehem Shipbuilding, 303 U. S. 41 (1938)

8,10,13, 23, 24, 27

Natural Gas Pipeline Co. v. Slattery, 302 U. S. 300

(1938) ___________________________________ 23

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 (1927)___________ 14

Order of Railway Conductors v. Pitney, 326 U. S. 561

(1946) _____ 8,24

Pacific Tel. & Tel. Co. v. Seattle, 291 U. S. 300 (1934)_ 23

Picking v. Penn. R. Co. (C. A. 3), 151 F. (2d) 240

(1945) ________________ „_________________14,29

Prendergast v. N. Y., 262 U. S. 43 (1923)__________ 18, 28

Prentis v. Atlantic Coast Line Co., 211 TJ. S. 210 (1908) 23

Pusey & Jones Co. v. Hanssen, 261 U. S. 491________ 23

Rice v. Elmore (C. C. A. 4), 165 F. (2d) 387 (1947)__14,15

Rice v. Santa Fe Elevator Corp., 331 U. S. 218 (1947)_8, 24

Robert v. Lowndes, TJ. S. 1). C. List. Md_______ ___ 16

Robinson v. Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, 222 TJ. S. 506

(1912) ______________ ______________ 10,13,24,27

Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91 (1945)________ 14

Securities & Exchange Commission v. Otis, 338 TJ. S.

843 (1949) ________________________________ 8, 24

Shannahan v. United States, 303 U. S. 296 (1938)____ 23

Shelley v. Kramer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948)______________ 26

Sipuel v. Bd. of Regents, Univ. of Oklahoma, 332 U. S.

631 (1948) _______________________________ 17

Slocum v. Delaware, Lackawanna & Western R. Co.,

339 U. S. 239 (1950) _______________ 10,13, 26, 27

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 (1944)___ 10,14,15, 27, 29

VI

PAGE

State ex rel. Plunkett v. Miller, 162 Miss. 149 (1931) 18, 28

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville E. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192

(1944) ___________________________________ 9

Texas & P. Ry. v. Abilene Cotton Oil Co., 204 U. S.

426 (1907) ----------------------------------------10,13,24,28

Thomas v. Gray, U. S. D. C., M. D., N. C .__________ 16

Thomas v. Hibbitts (D. C. Tenn.), 46 F. Supp. 368

(1942)------------------------------------------------------- 16

Thompson v. Gibbes (D. C. S. C.), 60 F. Supp. 872

(1945) ----------------------- ,----------------------------- 16,27

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and

Enginemen, 323 U. S. 210 (1944) _____________ 9

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U. S. 75 (1947) 9

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299 (1944)_______ 14

United States v. Sing Tuck, 194 U. S. 161 (1904)__ 8, 23, 24

United States Alkali Export Ass’n Inc. v. United

States, 325 U. S. 196 (1945)______9,18,19, 24, 28, 29, 32

Vandalia Railroad Co. v. Public Service Comm., 242

U. S. 255 (1916) ___________________________ 23

Westminster School District v. Mendez (C.C.A. 9), 161

F. (2d) 774 (1947) ________________________14,15

Whitmyer v. Lincoln Parish School Bd. (D. C. La.), 75

F. Supp. 686 (1948) ________________________ 16

Wrighten v. Board of Trustees (D.C.S. C.), 72 F. Supp.

948 (1947) 16

Vll

A p p en d ix

Mississippi Code, 1942 and 1948 Supplement

Section 6217

Section 6218

Section 6219

Section 6232.11

Section 6232.12

Section 6232.13

Section 6232.14

Section 6232.15

Section 6234

Section 6235

Section 6236

Section 6237

Section 6238

Section 6245.01

Section 6245.02

Section 6245.03

Section 6245.04

Section 6411

Section 6416

Section 6418

Section 6245.05

Section 6245.07

Section 6245.08

Section 6258

Section 6259

Section 6260

Section 6261

Section 6262

Section 6263

Section 6264.5

Section 6281

Section 6282

Section 6283

Section 6284

Section 6290

PAGE

.38, 81

Vlll

PAGE

Mississippi Code, 1942 and 1948 Supplement______38, 81

Section 6295

Section 6422

Section 6423

Section 6527

Section 6528

Section 6541

Section 6542

Section 6543

Section 6558

Section 6569

Section 6570

Section 6571

Section 6572

Section 6574

Mississippi Senate Bill No. 500__________________ 82

Mississippi Senate Bill No. 501__________________ 84

Georgia Code Annotated

Section 32-613 _____________________________ 90

IN' THE

Supreme Court of the United States

O ctober T erm , 1950

No.

G ladys N oel B ates and R ichard J ess

B row n , Individually and on Behalf of

the Negro Teachers and Principals in

the Jackson Separate School District,

Petitioners,

vs.

J o h n C. B atte , President; R. M. H eder-

m a n , J r ., Secretary; R. W . N a ef , W . R.

N e w m a n , J r ., and W . D. M cCa in , Con

stituting the Board of Trustees of

Jackson Separate School District and

K. P. W alker , Superintendent of Jack-

son Separate Schools,

Respondents.

PETITIO N FO R W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO

TH E UNITED STATES COURT OF A PPEALS

FOR TH E FIFTH CIRCUIT.

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of

the United States:

Petitioners respectfully pray that a writ of certiorari

issue to review the judgment of the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit affirming the judgment of

the District Court of the United States for the Southern

2

District of Mississippi dismissing this action on the ground

that petitioners had failed to exhaust administrative reme

dies provided by the laws of the State of Mississippi.

Summary Statement of the Matter Involved.

This suit was filed in the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Mississippi on March 4, 1948.

The suit was originally brought by Gladys Noel Bates,

individually, and on behalf of the Negro teachers and prin

cipals in the Jackson Separate School District. The grava

men of her complaint was that the respondents were dis

criminating against her and all other Negro teachers and

principals similarly situated in the fixing and payment of

teachers’ salaries solely because of race and color in viola

tion of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution (R. 3-15).

This suit was brought pursuant to the provisions of

Title 8, United States Code, Section 43, and the jurisdiction

of the District Court was invoked pursuant to the pro

visions of Title 28, United States Code, Section 1343(3)

(R. 3-4).

On February 7, 1948, prior to filing suit in the District

Court, petitioner Gladys Noel Bates filed a petition with

the respondents on behalf of herself and other Negro

teachers and principals in the public school system of Jack-

son, Mississippi, alleging unconstitutional discrimination

in the fixing and payment of teachers ’ salaries and petition

ing for an abandonment and cessation of such practices (R.

66-67). Respondents in reply to this petition advised the

original plaintiff by letter that they had no knowledge of

any such discrimination (R. 89).

On May 5, 1948, the respondents, defendants in the Dis

trict Court, moved to dismiss the complaint on the ground,

3

inter alia, that the plaintiff, petitioner Gladys Noel Bates,

had failed to exhaust administrative remedies provided by

the laws of the State of Mississippi (R. 16-17). This mo

tion was denied on December 20, 1948 (R. 18). On Febru

ary 15, 1949, respondents filed their answer (R. 19-38) and

moved for summary judgment (R. 19), which motion was

denied on July 15, 1949 (R. 61).

In the interim, respondents refused to renew their con

tract with Mrs. Bates because of her participation in this

suit (R. 163, 244). On May 9,1949, petitioner Richard Jess

Brown filed a motion to intervene as party-plaintiff in the

District Court which was granted on December 12, 1949

(R. 66).

This cause came to trial on December 12, 1949. Before

proceeding with the taking of testimony, the trial court

again ruled that the defense of failure to exhaust adminis

trative remedies was insufficient in law, that the adminis

trative remedies provided were inadequate and had ref

erence only to those controversies arising under the school

laws of the State of Mississippi; that this controversy arose

not under the school laws of Mississippi, but under the

Constitution of the United States and that, therefore, the

statutory provisions on which respondents relied need not

have been pursued before bringing this action (R. 63-64).

After trial, but before judgment, the United States Court,

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, decided the case of Cook

v. Davis, 178 F. (2d) 595 (1949), cert, denied, 340 U. S.

811 (1950). In that case, the court below reversed a judg

ment of the United States District Court for the Northern

District of Georgia, which had entered judgment enjoining

and restraining the defendants from paying to the plaintiff

and other Negro teachers and principals in the public

schools of Atlanta, Georgia, less salaries than was paid to

4

white teachers and principals of equal qualifications and

experiences and performing substantially the same duties

solely because of race and color in violation of the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, on the

ground that state administrative remedies had not been

exhausted.

On February 22, 1950, the District Court rendered an

opinion dismissing the complaint herein without prejudice

on the ground that the plaintiff had failed to exhaust ad

ministrative remedies (R. 253, 256). The trial court stated

that it did so reluctantly but felt that it was bound by the de

cision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit in the Co oh case. The trial court stated that it was

still of the opinion that the administrative remedies pro

vided by the laws of the State of Mississippi were inade

quate (R. 253), and made findings of fact and conclusions

of law in its opinion in order that the appellate court might

have before it the whole case (E. 253).

It found that the wide differential between the salaries

paid to Negro teachers and principals and those paid to

white teachers and principals could only have resulted from

racial discrimination in violation of the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (E. 248). It further

found that as to petitioners Gladys Noel Bates and Richard

Jess Brown less salary was being paid to them than was

being paid to white teachers of equal qualification and ex

perience and performing substantially the same functions

(R. 247). The trial court held, however, that the failure of

respondents to renew the contract of Mrs. Bates was not

illegal (R. 256-257) in spite of the fact that evidence was

produced at the trial to show that Mrs. Bates had not been

reemployed solely because of her participation in this ac

tion (R. 136, 137, 159, 162, 163, 164). Final judgment was

5

entered March 22, 1950. Notice of Appeal was filed on

March 20, 1950 (R. 258).

The argument before the United States Court of Ap

peals took place on January 24, 1951 (R. 296). That court

affirmed the judgment of dismissal of the District Court on

February 15, 1951. In affirming the judgment of the Dis

trict Court, it ruled that this case was governed by Cook v.

Davis, supra (R. 298). Whereupon, petitioners bring the

cause here by this petition for writ of certiorari.

Statem ent of Facts.

Petitioners do not set forth a detailed statement of the

factual evidence produced at the trial showing the existence

of discrimination in the payment of teachers salaries. The

inclusion of this matter petitioners deem immaterial for the

reason that that issue is not before this court. Howrever, a

brief resume of the essential facts follows in order to give

this Court a more complete picture of the entire case.

The respondents, upon the trial, freely admitted that

Negro teachers were paid less salary than white teachers

(R. 69, 79, 106, 208, 210, 212). Witnesses for respondents

testified that as to character, professional qualifications and

academic training, there was no difference between Negro

and white teachers (R. 113-114). In summary, the respon

dents attempted to justify the higher pay to white teachers

on the ground that such teachers were better able to use

their training and organize their work and were further

advanced culturally than were the Negro teachers and prin

cipals (R. 100-154).

Petitioners engaged the services of a professional statis

tician who made a statistical analysis of all of the records

of the respondents with respect to salaries. This analysis

is contained in Exhibit #9 which has been transmitted to

6

this court in its original form as a part of the record. This

study shows that although Negro teachers and principals

compared favorably with white teachers and principals in

training and experience and types of certificates held, their

rate of compensation was far below that of white teachers

and principals in every category and at every level in the

public school system. For example, as between white prin

cipals and Negro principals at the senior high school level,

there was a salary differential of 110 percent (R, 187); at

the .junior high school level, 111.54 percent (R. 187); at the

elementary school level, 81.32 percent (R. 187). As between

white and Negro teachers at the senior high school level,

the differential was 57.65 percent (R. 187); at the junior

high school level, 46.40 percent (R. 187); and at the elemen

tary school level, 53.30 percent (R. 187). These facts were

not disputed by appellees.

The trial court found that petitioners and other Negro

teachers and principals were being discriminated against

in the payment of salaries and, except for the decision in

Cook v. Davis, would have entered judgment for petitioners.

The Opinion of the Court of Appeals.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir

cuit in affirming the judgment of the trial court relied on

its own decision in the case of Cook v. Davis, supra (R.

298). Without going into the similarities and dissimilari

ties between the Georgia and Mississippi statutes, the Court

simply stated that “ the statutes of the two states are suffi

ciently alike to make the decision in Cook’s case dispositive

of the appeal.” The Court affirmed the judgment of dis

missal for failure to exhaust administrative remedies. The

opinion of the Court of Appeals is reported. Bates v.

Batte, 187 Fed. (2d) 142 (1951) (Adv. Op.).

7

Jurisdiction.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to the

provisions of Title 28, United States Code, Section 1254.

This is a case arising under the Constitution and laws of

the United States and involves rights secured by the Four

teenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution, and was

brought to enforce a right conferred by act of Congress.

In the original complaint filed by petitioner Gladys Noel

Bates and in the complaint filed by the intervenor-plaintiff,

Bichard Jess Brown, and throughout the entire proceed

ings, petitioners have maintained that the action of re

spondents in paying them and the other Negro teachers

and principals in the Jackson, Mississippi, Separate School

District less salaries than is paid to white teachers and

principals of equal qualifications and experience is a denial

of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution.

Questions Presented.

I.

Whether the rule which requires that administrative

remedies be exhausted before seeking relief from a federal

court is properly invoked in an action brought pursuant to

Act of Congress where the Congress has not conferred on

an administrative agency primary exclusive jurisdiction to

hear and determine such cases?

II.

Whether the rule which requires that administrative

remedies be exhausted before seeking relief from a federal

court is properly invoked in an action in a federal district

court which has been brought to redress the deprivation

8

under color of state statute, regulation, custom and usage

of a right, privilege or immunity secured by the Consti

tution and laws of the United States as provided by Title

8 U. S. C. § 43 and Title 28 U. S. C. § 1343(3) ?

III.

Whether the State of Mississippi has provided an ad

ministrative remedy which must be pursued by a teacher

complaining of unconstitutional discrimination in the fixing

and payment of teachers’ salaries before seeking the aid

of a federal district court to enjoin such discrimination in

accordance with the provisions of Title 8 U. S. C. § 43 and

Title 28 U. S. C. §1343(3)?

Reasons Relied Upon for Allowance of Writ.

I.

The rule which requires that administrative remedies

be exhausted prior to resorting to a federal court for relief

is a rule which is applied by this Court in cases involving

Acts of Congress only where there is clearly expressed or

implied a legislative intent or design to confer on an ad

ministrative agency, whether state or federal, primary

exclusive jurisdiction to hear and determine certain mat

ters, with express power to remedy, Securities & Exchange

Commission v. Otis, 338 U. S. 843 (1949), Rice v. Santa Fe

Elevator Corp., 331 U. 8. 218 (1947), Aircraft <& D. Equip

ment Corp. v. Eirsch, 331 U. S. 752 (1947), Federal Power

Commission v. Arkansas Power & Light Co., 330 U. S. 802

(1947), Macauley v. Waterman Steamship Corp., 327 U. S.

540 (1946), Order of Railway Conductors v. Pitney, 326

U. S. 561 (1946), Myers v. Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corp.,

303 U. S. 41 (1938), United States v. Sing Tuck, 194 U. S.

161 (1904); and when this Court has found no such Con-

9

gressional intent or design or agency power, pleas for

application of the rule have been denied. United Public

Workers v. Mitchell, 330 XL S. 75 (1947), First Iowa Hydro-

Electric Cooperative v. Federal Power Commission, 328

U. 8. 152 (1946), Georgia v. Penn. R. R. Co., 324 U. S. 439

(1945), United States Alkali Export Ass’n Inc. v. United

States, 325 XJ. 8. 196 (1945), Tunstall v. Brotherhood of

Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen, 323 XI. S. 210 (1944),

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R. R. Co., 323 XT. 8. 192

(1944).

In providing by Title 8 XT. S. C. §43 for the right of

redress, in law or equity or other proper proceeding,

against “ Every person who, under color of any statute,

ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any state or

Territory, subjects or causes to be subjected a citizen of

the XTnited States, or other persons within the jurisdiction

thereof, to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or

immunities secured by the Constitution and laws”, the

Congress of the XTnited States did not, either expressly or

impliedly, confer on an administrative agency, whether

state or federal, primary exclusive jurisdiction to hear and

determine whether such deprivation had occurred, with

power to remedy, but conferred upon the district courts of

the XTnited States, by the express provisions of Title 28

XT. 8. C. §1343(3), original jurisdiction in such cases with

out attaching thereto any jurisdictional prerequisites.1

1 Title 28 U. S. C. § 1343(3) provides:

“The district courts shall have original jurisdiction of any civil

action authorized by law to be commenced by any person:

* * *

“ (3) To redress the deprivation under color of any State law,

statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or usage, of any right, privi

lege or immunity secured by the Constitution of the United States

or by any Act of Congress providing for equal rights of citizens or

of all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States.” (June

25, 1948, c. 646, § 1, 62 Stat. 932.)

10

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 (1944), Douglas v. Jean

nette, 319 U. S. 157 (1943), Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496

(1939), Bottone v. Lindsley (C. A. 10), 170 F. (2d) 705

(1948), Glicker v. Michigan (C. A. 6), 160 F. (2d) 96 (1947),

City of Manchester v. Leihy (C. A. 1), 117 F. (2d) 661

(1941).

The decision of the court below is, therefore, not in ac

cord with the decisions of this Court in cases involving

Acts of Congress.

II.

The rule of exhaustion of administrative remedies was

applied for the first time by a federal court of appeals in

a case of this kind, as far as counsel for petitioners have

been able to ascertain, in Cook v. Davis (C. A. 5), 178 F.

(2d) 595 (1949), cert, denied 340 U. S. 811, a case decided

after trial in the instant case but just prior to the district

court’s decision herein and relied on by the district court

and the court below in dismissing this action. A jurisdic

tional prerequisite to bringing a case pursuant to Title 8

U. S. C. § 43 and Title 28 U. S. C. § 1343(3) has thus been

added by judicial fiat. cf. Slocum v. Delaware, Lackawana &

Western R. Co., 339 U. S. 239 (1950), Armour & Co. v.

Alton R. R., 312 IT. S. 195 (1941), Myers v. Bethlehem

Shipbuilding Corp., 303 U. S. 41, 52 (1938), Board of Rail

road Com’rs v. Great, N. Ry., 281 U. S. 412 (1930), Great

N. Ry. v. Merchants Elevator Co., 259 U. S. 285, 290 (1922),

Robinson v. Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, 222 U. S. 506

(1912), Texas <& P. Ry. v. Abilene Cotton Oil Co., 204 U. 8.

426 (1907).

Thus the judgment of the court below, affirming the

judgment of the district court reluctantly rendered after

petitioners succeeded on the merits, that this action must

11

be dismissed for failure of petitioners to exhaust state

administrative remedies is not in accord with the intent

of Congress that the district courts of the United States

have original jurisdiction of civil actions brought to en

force the right conferred by Title 8 U. S. C. §43.

III.

This Court denied a petition for writ of certiorari in

the Cook case, Davis v. Cook, cert, denied 340 U. S. 811

(1950), but the petition therein did not present for con

sideration the questions here presented—the major one

being whether the rule of exhaustion of administrative

remedies is properly invoked in an action brought pursuant

to Title 8 U. S. C. §43 in a district court of the United

States pursuant to Title 28 U. S. C. §1343(3). Therefore,

the main question here presented is squarely before this

Court for the first time. See, Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S.

268, 274 (1939); Mitchell v. Wright (C. A. 5), 154 F. (2d)

924, 928, cert, denied 329 U. S. 733 (1945).

IV.

The facts in this case are materially different from the

facts in the Cook case. In the latter case, the defendant

local Board of Education, after the institution of the action

in the federal court, adopted a new salary schedule. The

court below was of the opinion that unconstitutional dis

crimination had been eliminated from the new schedule

and that the discrimination which still existed resulted

from the dual salary schedule established by the State

Board of Ediication. The State Board in that case had the

power, Georgia Code Ann. 32-613, to fix a schedule of

minimum salaries to be paid to teachers out of the public

school funds of the state, and although the local boards

could supplement this salary, they were bound to pay

12

every teacher this minimum. In addition, the State Board in

Georgia was empowered to determine the minimum number

of teachers which each local board might employ and to

classify such teachers. It disbursed school funds to the

various local boards on the basis of the minimum stand

ards which it established. The State Board was not made

a party defendant, although it was an indispensable party

to the action because of the power it exercised with respect

to teachers ’ salaries. Without having jurisdiction over the

State Board, the issue of salary discrimination could not

have been completely determined by the court in the Cook

case.

In the instant case, the State Board has no power to fix

teachers’ salaries. The trial court found that it was the

exclusive duty of the respondent board to select teachers

and fix their salaries (R. 249, 250). The State Board has

only general supervisory powers over the schools and dis

perses the school funds on a per capita basis. It does not

even have power to determine what portion of the funds

so dispersed may be used for teachers’ salaries. There

fore, the determination as to salaries made by the respon

dent board in this case is final. The State Board in this

case was therefore not a necessary defendant or a proper

agency to which to appeal. Even if petitioner appealed to

the State Board, that agency could take no action deter

minative of the issues herein presented.

The court below did not direct the district court to re

tain jurisdiction of this cause until the alleged administra

tive remedies had been exhausted, as was done in the Cook

case. Instead, the court below affirmed the judgment of

dismissal, thus indicating that the district court had no

jurisdiction until the alleged remedies had been exhausted.

The material and controlling facts in the Cook case are

therefore entirely different from those in the instant case

13

and, therefore, the Cook decision, contrary to the decision

of the court below, cannot govern the disposition of this

case.

V .

On motion for rehearing which was denied, the court

below in the Cook case held that the rule of exhaustion of

administrative remedies “ is a rule of self-restraint formu

lated by the federal courts and is not influenced by state

practice”. This reasoning was relied on by the district

court in the instant case. In cases arising under Acts of

Congress, this Court has looked to the statute passed by

the Congress to determine whether the Congress intended

exhaustion of administrative remedies to be a jurisdic

tional prerequisite. Slocum v. Delaware, Lackawanna &

Western R. Co., supra; Armour & Co. v. Alton R. R., supra;

Roard of Railroad Com’rs v. Great N. Ry., supra; Great N.

Ry. v. Merchants Elevator Co., supra; Myers v. Bethlehem

Shipbuilding Corp., supra; Robinson v. Baltimore & Ohio

Railroad, supra; Texas P. Ry. v. Abilene Cotton Oil Co.,

supra. Therefore, with respect to cases involving Acts of

Congress, as in the instant case, the rule of exhaustion of

administrative remedy is not applied by this Court as a

matter of judicial self-restraint, especially when Congress

has indicated specifically that jurisdiction is in federal

courts, but is applied only where there is clearly expressed

or implied a legislative intent or design to confer on an

administrative agency, whether state or federal, primary

exclusive jurisdiction to hear and determine certain matters

before invoking the jurisdiction of a federal court.

VI.

Title 8 U. S. C. §43 is one of the Civil Eights Acts

passed by the Congress immediately after adoption of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution pursu-

14

ant to the provisions of Section 5 of the Amendment which

specifically empowered the Congress “ to enforce, by ap

propriate legislation” the provisions of the Amendment.2

This Act granted “a right of action sounding in tort to

every individual whose federal rights are trespassed upon

by an officer acting under pretense of state law” .8 In other

words, “a field was created upon which a state officer could

not tread without being guilty of trespass and liable in

damages” 4 in action at law, Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S.

536 (1927); Smith v. Allwright, supra; see, United States

v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299, 323-324 (1941) and Screws v.

United States, 325 U. S. 91, 99 (1945); Picking v. Penn. R.

Co. (C. A. 3), 151 F. (2d) 240 (1945); Burt v. City of New

York (C. A. 2), 156 F. (2d) 791; Bottone v. Lindsley, supra;

or without subjecting himself to an injunction in a suit in

equity, Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496 (1939); Morris v.

Williams (C. A. 8), 149 F. (2d) 703 (1945); Westminster

School District, etc. v. Mendez (C. A. 9), 161 F. (2d) 774

(1947); Rice v. Elmore (C. A. 4), 165 F. (2d) 387 (1947).

Title 8 IT. S. C. § 43 therefore conferred a right. It

conferred a right to bring an action either in law or in

equity to redress the deprivation, under color of state law,

custom, or usage, of rights, privileges, and immunities se-

2 The legislative history of this act is found in Congressional

Globe 42nd Congress, 1871, First Session, Part 1, report on H.R.

No. 320, p. 317 and debate pp. 385, 395, 461 and 495, and Part 2,

Appendix, pp. 86, 113, 209 and 217, 217.

The Act provides: “Every person who, under color of any stat

ute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory,

subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United States

or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of

any rights, privileges or immunities secured by the Constitution and

laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in

equity, or other proper proceeding for redress.” Act of April 20,

1871, Chap. 22, 17 Stat. at L. 13, Revised Statutes, § 1979.

3 Picking v. Penn R. Co. (C. A. 3), 151 F. (2d) 240, 249 (1945).

4 Ibid.

15

cured by the Federal Constitution. The right not to have

race discrimination play a part in the fixing and payment

of teachers’ salaries is a right secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution. Alston v. School

Board (C. A. 4), 112 F. (2d) 992 (1940), cert, denied 311

U. S. 693. Protection of this right does not involve a de

termination of the salary which should be paid to an indi

vidual teacher or even a class of teachers. Alston v. School

Board, supra; Morris v. Williams (C. A. 8), 149 F. (2d) 703.

An action such as this, which is brought in equity to pro

tect this right with respect to the future, is thus not an

action which requires that the court be substituted for an

administrative agency—it is one brought to eliminate from

the administrative determination unconstitutional discrimi

nation in the future, cf. Georgia v. Penn. R. R., 324 IT. S.

439 (1945). The right to bring such an action initially in

a federal court is specifically authorized by Act of Con

gress. Title 28 U. S. C. § 1343(3).

Once these rights are established, the whole concept of

exhaustion of administrative remedies is inapplicable for

the simple reason that no administrative determination is

involved.

VII.

Since the enactment of Title 8 U. S. C. § 43, numer

ous actions have been successfully brought via Title 28

IT. S. C. §1343(3) in the federal district courts without

the necessity of meeting any jurisdictional prerequisites

other than those set forth in said statutes. Smith v.

Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 (1944); Douglas v. Jeannette, 319

IT. S. 157 (1943); Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 IT. S. 496 (1939);

Bottone v. Lindsley (C. A. 10), 170 F. (2d) 705 (1948);

Glicker v. Michigan (C. A. 6), 160 F. (2d) 96 (1947); West

minster School District v. Mendez (C. A. 9), 161 F. (2d)

774 (1947); Rice v. Elmore (C. A. 4), 165 F. (2d) 387

(1947); Morris v. Williams (C. A. 8), 149 F. (2d) 703

16

(1945); City of Manchester v. Leiby (0. A. 1), 117 F. (2d)

661 (1941); Johnson v. Board of Trustees, (D. C.-Ky.), 83

F. Supp. 707 (1949); Whitmyer v. Lincoln Parish School

Bd. (D. C.-La.), 75 F. Supp. 686 (1948); Wrighten v. Board

of Trustees (D. C.-S. C.), 72 F. Supp. 948 (1947); Thompson

v. Gibbes (D. C.-S. C.), 60 F. Supp. 872 (1945); Lopes v.

Seccombe (D. C.-Col.), 71 F. Supp. 769 (1944); Thomas v.

Hibbitts (D. C.-Tenn.), 46 F. Supp. 368 (1942). This prac

tice and the authority of district courts to proceed in these

cases without prior resort to other remedies, Carter v.

School Board (C. A. 4), 182 F. (2d) 531 (1950); Burt v.

City of New York (C. A. 2), 156 F. (2d) 791, semble;

Thompson v. Gibbes, supra; see Heard v. Ouachita Parish

School Board (D. C.-La.), 94 F. Supp. 897 (1951), is thus

firmly established in our jurisprudence.

Several cases brought to enforce the right conferred by

Title 8 U. S. C. § 43 pursuant to Title 28 U. S. C. § 1343(3)

are presently pending in federal district courts throughout

the United States.5 In several of these cases the defendant

state officers have already raised the objection that plain

tiffs have failed to exhaust administrative remedies, rely

ing on Cook v. Davis (C. A. 5), 178 F. (2d) 595 (1949),

cert, denied 340 U. S. 811.8 These cases involve not only

complaints of unconstitutional discrimination in the fixing

and payment of teachers’ salaries but involve cases com

plaining of unconstitutional discrimination in providing

public education. In the latter kind of case, this Court has

already rejected the plea that a prior demand must first be

5 E. g. Briggs v. Elliott, U. S. D. C., E. D., S. C .; Aaron v. Cook,

U. S. D. C., N. D., Ga.; Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka,

U. S. D. C., First Dist., Kansas; Roberts v. Lowndes, U. S. D. C.,

Dist. M d.; Thomas v. Gray, U. S. D. C., M. D., N. C .; Heard v.

Ouachita Parish School Bd. (U. S. D. C., W. D., La.), 947 F. Supp.

897 (1951).

6 Briggs v. Elliott, supra, note 5; Aaron v. Cook, supra, note 5.

17

made on state officials before relief can be sought in the

courts, Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of Okla

homa, 332 U. S. 631 (1948); Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U. S. 147

(1948).

For the foregoing reasons, and for the reason that the

rights which were intended to be granted or secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution, for

the infringement of which the Congress has provided a

right of action, are presently subject to such infringement

by persons acting under color of state law in open and ex

press defiance of recent decisions of this Court,7 this peti

tion should be granted in order to put an end to the uncer

tainty which now exists with respect to the intent of Con

gress in enacting Title 8 U. S. C. § 43 and Title 28 U. S. C.

§1343(3) and to the uncertainty for both litigants and

federal courts which ensues since Cook v. Davis, supra,

VIII.

The judgment of the court below is in conflict with the

judgment of other circuits, Carter, et al. v. School Board

(C. A. 4), 182 F. (2d) 531 (1950) and Burt v. City of New

York (C. A. 2), 156 F. (2d) 791 (1945), semble, cases

7 In February, 1951, the Georgia Legislature passed a bill author

izing withdrawal of school funds from any white school to which a

court might order a Negro admitted. See N. Y. Times for February

11, 15, 18, 1951.

On September 28, 1950, the N. Y. Times reported that Gov.

Herman Talmadge of Georgia had asserted that the United States

does not have enough troops or police to enforce a court order for

Negro and white students to sit in the same class rooms.

On May 11, 1951, the N. Y. Times reported that the legislature of

the State of Florida was contemplating legislation similar to that

passed by the State of Georgia.

On January 25, 1951, and on March 17 and 19, 1951 the New

York Times reported that Gov. James Bums of South Carolina

threatened action similar to that taken in Georgia and generally

threatened to defy anti-segregation rulings.

18

brought to enforce the right conferred by Title 8 U. S. C.

§ 43 pursuant to the provisions of Title 28 U. 8. C.

§1343(3).

IX.

Even if this Court should decide that the rule requiring

exhaustion of administrative remedies is properly invoked

in an action in a federal district court to redress the depri

vation under color of state law of a right secured by the

federal constitution, the State of Mississippi has not pro

vided an administrative remedy which must be exhausted

by a teacher complaining of unconstitutional discrimination

in the fixing and payment of teachers’ salaries since ex

haustion of this remedy is not mandatory, cf. First Iowa

Hydro-Electric Cooperative v. Federal Power Commission,

328 U. S. 152 (1946); United States Alkali Export Assn. Inc.

v. United States, 325 IT. S. 196 (1945), cf. Levers v. Ander

son, 326 U. 8. 219 (1945) and Prendergast v. New York,

262 U. S. 43 (1923), Moore v. Illinois Central Railway, 312

U. 8. 630 (1941), having been so construed by the highest

court of the State of Mississippi, State ex rel. Plunkett

v. Miller, 162 Miss. 149 (1931), Clark, et al. v. Board of

Trustees, 117 Miss. 234 (1918), Moreau v. Grandich, 114

Miss. 560 (1917), Hobbs v. Germany, 94 Miss. 469 (1909).

In addition, the agencies to which petitioners might

have appealed are without the authority or power to

remedy the discrimination. The sole power and authority

of the county superintendent is to render a decision and

give advice in all controversies arising under the school

law. Miss. Code (1942) § 6261. The sole power and author

ity of the State Board is to render a decision on a written

statement of facts in appeals from the decisions of the

county superintendent or the state superintendent. Miss.

Code (1942) §6234. Neither agency has power to enforce

19

its decisions, cf. Federal Power Commission v. Panhandle

Eastern Pipe Line Co., 337 U. S. 496 (1949); Hillsborough

v. Cromwell, 326 U. S. 620 (1946); Georgia v. Penn. R. R.

Co., 324 U. S. 439 (1945); United States Alkali Export

Assn., Inc. v. United States, supra.

The judgment of the Court below is thus not in accord

with the decisions of this Court in cases where the admin

istrative remedy has been found to be not mandatory and

in cases where it was found that the administrative agency

lacked the power of remedy.

Conclusion.

W h er efo r e , it is respectfully submitted that this peti

tion for writ of certiorari to review the judgment of the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit should be granted.

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood M arshall ,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, New7 York,

Attorneys for Petitioners.

J am es A. B u r n s ,

C onstance B aker M otley ,

Of Counsel.

Dated: May 15, 1951.

1ST T H E

Supreme Court of the United States

O ctober T erm , 1950

No.

G ladys N oel B ates and R ichabd J ess

B row n , Individually and on Behalf of

the Negro Teachers and Principals in

the Jackson Separate School District,

Petitioners,

vs.

J ohn C. B atte , President; R. M. H edeb-

m a n , J b., Secretary; R. W. N aee, W. R.

N ew m a n , J b., and W. D. M cCa in , Con

stituting the Board of Trustees of

Jackson Separate School District and

K. P. W alk eb , Superintendent of Jack-

son Separate Schools,

Respondents.

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR WRIT OF

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT

OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT.

Opinion of the Courts Below.

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit is found on page 296 of the record in this

ease. The opinion is officially reported in the advanced

opinions of the Federal Reporter, Second Series, Bates v.

21

22

Batte, 187 F. (2d) 142 (1951). The opinion of the United

States District Court for the Southern District of Missis

sippi may he found on page 245 of the record. That opin

ion is not officially reported.

Jurisdiction.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

the provisions of Title 28, United States Code, Section

1254. The United States District Court for the Southern

District of Mississippi entered a final judgment in this

cause dismissing the action for failure to exhaust state

administrative remedies on March 22, 1950. That judg

ment was affirmed by the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit on February 15, 1951. This is a case

arising under the Constitution and laws of the United

States. In this action petitioners have consistently main

tained that rights secured to them by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution have been violated.

Statement of the Case.

The Statement of the Case is contained in the Summary

Statement of the Matter Involved in the Petition for Writ

of Certiorari herein.

Statement of the Facts.

A brief statement of the facts is made in the Petition

for Writ of Certiorari and therefore will not be repeated

here.

Errors Relied Upon.

The Court below erred in applying the rule of ex

haustion of administrative rem edies to this case.

23

The Court below erred in affirming the judgment

of dismissal on the ground that state administrative

remedies had not been exhausted.

The Court below erred in holding that this case is

governed by Cook v. Davis (C. A. 5 ), 178 F. (2d) 595

(1949), cert, denied 340 U. S. 811.

A R G U M E N T .

I.

The rule of exhaustion of administrative remedies

was improperly applied to this case.

A . It w a s not th e in ten t o f C ongress th a t an adm in istrative

a g en cy h a v e prim ary and exc lu sive jurisd iction .

The rule which requires that administrative remedies

be exhausted before invoking the jurisdiction of a federal

court is unusually broad in its scope.1 Its application to

varying circumstances2 has been so wide that it now ap

pears that the rule is not one rule but an unconscious

assimilation of several ancillary rules or rules having a

similar effect in application.3 Nevertheless, whenever a

1 Berger, Exhaustion of Administrative Remedies, 48 Yale L. T.

981 (1939).

2E. g. Prentis v. Atlantic Coast Line Co., 211 U. S. 210 (1908);

United States v. Sing Tuck, 194 U. 8. 161 (1904); First National

Bank v. Albright, 208 U. S. 548 (1908) ; Pacific Tel. & Tel. Co. v.

Seattle, 291 U. S. 300 (1934) ; Natural Gas Pipeline Co. v. Slattery,

302 U. S. 300 (1938) ; Pusey & Jones Co. v. Hanssen, 261 U. S. 491

(1923); Myers v. Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corp., 303 U. S. 41

(1938) ; Vandalia Railroad Company v. Public Service Commission,

242 U. S. 255 (1916); Shannahan v. United States, 303 U. S. 296

(1938).

8 Davis, Administrative Law Doctrines of Exhaustion of Reme

dies, Ripeness for Review, and Primary Jurisdiction, 28 Texas L.

Rev. 168, 376 (1949). Professor Davis intimates that courts have,

in applying this rule, assimilated the equity rule of not lending its

aid where there was an adequate remedy at law, the rule that a court

should not intervene until the matter is ripe for judicial review, the

rule of primary jurisdiction.

24

ease has come before this Court which is the subject of

Congressional legislation, this Court has looked at the

statute passed by the Congress to determine whether the

Congress has conferred on an administrative agency pri

mary exclusive jurisdiction to hear and determine certain

matters before providing for judicial review. Securities

& Exchange Commission v. Otis, 338 U. S. 843 (1949); Rice

v. Santa Fe Elevator Corp., 331 IT. S. 218 (1947); Aircraft

& D. Equipment Corp. v. Hirsch, 331 IT. S. 752 (1947);

Federal Power Commission v. Arkansas Power & Light

Co., 330 IT. S. 802 (1947); Macauley v. Waterman Steam

ship Corp., 327 IT. S. 540 (1946); Order of Railway Con

ductors v. Pitney, 326 IT. S. 561 (1946); Myers v. Bethlehem

Shipbuilding Corp., supra; United States v. Sing Tuck, 194

U. S. 161 (1904). In other words, this Court must find

that the Congress intended that certain matters should be

first determined by an administrative tribunal as a pre

requisite to the court’s jurisdiction. Armour <& Co. v.

Alton R. R., 312 IT. 8. 195 (1941); Myers v. Bethlehem Ship

building Corp., supra; Board of Railroad Com’rs. v. Great

N. Ry., 281 U. 8. 412 (1930); Great N. Ry. v. Merchants

Elevator Co., 259 IT. S. 285, 290 (1922); Robinson v. Balti

more & Ohio Railroad, 222 IT. 8. 506 (1912); Texas <& P.

Ry. v. Abilene Cotton Oil Co., 204 IT. S. 426 (1907).

In addition, this Court must find that the administrative

agency has been granted the power of remedy and has the

authority to act. Federal Power Commission v. Panhandle

Eastern Pipe Line Co., 337 IT. S. 496 (1949); Hillsborough

v. Cromwell, 326 IT. S. 620 (1946); Georgia v. Penn. R. R.

Co., 324 IT. S. 439 (1945); United States Alkali Export

Ass’n, Inc. v. United States, 325 IT. S. 196 (1945).

In providing that there shall be a right of redress

against every person who, acting under color of state stat

ute, ordinance, regulation, custom or usage, subjects or

25

causes to be subjected a citizen of the United States, or

other persons within the jurisdiction thereof, to the depri

vation of any right, privilege, or immunity secured by the

Constitution and laws,4 the Congress of the United States

did not confer on an administrative agency primary exclu

sive jurisdiction to hear and determne certain matters

before the matter might be reviewed by the courts. On the

contrary, it expressly conferred original jurisdiction in such

cases on the district courts of the United States.5 The rea

sons for so doing are obvious. The purpose of the legis

lation wTas to curb the acts of state officers6—including the

judiciary, see, Burt v. City of New York (C. A. 2), 156 P.

(2d) 791 (1945). The fact that the southern states had

passed discriminatory legislation directed at the ex-slaves

and that officials of these states were openly depriving the

new citizens of their rights—especially those which the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution was

designed to protect—and the impossibility of receiving

adequate protection within the state from such acts, was

placed squarely before the Congress at the time that this

legislation was before it for consideration.7 The Congress

therefore conferred original jurisdiction on the federal dis

trict courts to hear and determine these cases.8 Other

wise the very purpose of the legislation would have been

defeated.

Title 8 U. S. C. § 43 in and of itself conferred a right.

It conferred a right to bring an action. This Court must

therefore look at the statutes to see whether the Congress

4 Title 8 U. S. C. § 43, Revised Statutes, § 1979.

5 Title 28 U. S. C. § 1343(3).

6 Congressional Globe, 42nd Congress, 1871, First Session, Part 1,

report on H.R. No. 320, p. 317 and debate pp. 385, 395, 461 and 495,

and part 2, Appendix, pp. 86, 113, 209, and 216, 217.

7 Ibid.

8 Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496, 508-510 (1939).

26

intended to confer primary exclusive jurisdiction on an

administrative agency, whether state or federal, before

bringing such action. In answer to this, the Court will

find that at the time that Congress conferred this right it

expressly provided that the federal courts should have

original jurisdiction in such cases.9 The jurisdiction of

district courts was then as now very limited.10 The Con

gress therefore made such action a special exception or a

special case for district court jurisdiction. It is therefore

clear that the Congress did not intend that a state adminis

trative agency should have primary jurisdiction in these

cases.

B. T h e question to be d ec id ed is not one w h ich is w ith in

th e p ecu liar co m p eten ce o f an estab lish ed ad m in istra

tive agen cy .

The question to be decided in these cases is not one which

is peculiarly susceptible of administrative determination.11

cf. Slocum v. Delaware, Lackawanna & Western R. Co., 339

U. S. 239 (1950). This is an action in which the relief

sought is a declaratory judgment and injunction (E. 13-14).

The question to be decided by the trial court in the instant

case, and which was decided by it in favor of these peti

tioners, is whether there is unconstitutional discrimination

in the salary fixing process which must be enjoined as to the

future, cf. Georgia v. Penn. R. Co., supra. This is a ques

tion which this Court has held is within the special com

petence of federal courts. Shelley v. Kramer, 334 U. S. 1

(1948).

The entire doctrine of exhaustion of administrative

remedies is thus inapplicable to this case.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Davis, supra, note 3 at 402.

27

C. N o ju risd iction a l p rereq u isites w ere p rescribed by

C ongress.

In providing that the district courts of the United States

shall have original jurisdiction in such cases, the Congress

did not attach thereto the usual jurisdictional prerequisites

for invoking the jurisdiction of district courts. Smith v.

Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 (1944); Douglas v. Jeannette, 319

U. S. 157 (1943); Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496 (1939);

Bottone v. Lindsley (C. A. 10), 170 F. (2d) 705 (1948);

Glicker v. Michigan (C. A. 6), 160 P. (2d) 96 (1947); City

of Manchester v. Leiby (C. A. 1), 117 P. (2d) 661 (1941).

Neither did it provide for preliminary administrative de

termination of certain matters with subsequent review by

the federal district courts. Carter v. School Board (C. A.

4), 182 P. (2d) 531 (1950); Burt v. City of New York,

supra, semble; Thompson v. Gibbes (D. C.-S. C.), 60 P.

Supp. 872 (1945); see, Heard v. Ouachita Parish School

Board (D. C.-La.), 94 P. Supp. 897 (1951). By requiring

that this action be dismissed and that administrative reme

dies be exhausted before resorting to a federal district

court, the court below prescribed a jurisdictional require

ment which has not been decreed by the Congress in a

matter about which Congress has legislated and a matter

which it has expressly brought within the original juris

diction of the district courts. When the Congress intends

exhaustion of administrative remedies as a jurisdictional

prerequisite to invoking the jurisdiction of federal courts,

this intention is clearly expressed or it may be readily

inferred. Slocum v. Deleware, Lackawanna & Western R.

Co., 339 U. S. 239 (1950); Armour & Co. v. Alton R. R.,

312 U. 8. 195 (1941); Board of Railroad Com’rs v. Great N.

Ry., 281 U. S. 412 (1930); Great N. Ry. v. Merchants Eleva

tor Co., 259 U. S. 285, 290 (1922); Myers v. Bethlehem Ship

building Corp., 303 U. S. 41, 52 (1938); Robinson v. Balti-

28

more & Ohio Railroad, 222 U. S. 506 (1912); Texas <& P. Ry.

v. Abilene Cotton Oil Co., 204 U. S. 426 (1907).

D. E xhaustion o f th e sta te ad m in istrative rem ed ies is not

m andatory.

The state statutory provisions on which respondents

and the courts below relied are set forth in the Appendix

to this brief.

The highest court in the State of Mississippi has con

strued these statutes. That court has consistently held

that the remedies provided are not exclusive but alterna

tive, and need not in any case be exhausted before resort

to the courts. State ex rel. Plunkett v. Miller, 162 Miss. 149

(1931); Clark, et al. v. Roard of Trustees, 117 Miss. 234

(1918); Moreau v. Grandich, 114 Miss. 560 (1917); Hobbs

v. Germany, 94 Miss. 469 (1909).

Whenever this Court has found that exhaustion of the

administrative remedy was not mandatory, application of

the rule has been denied. First Iowa Hydro-Electric Co

operative v. Federal Power Commission, 328 U. S. 152

(1946); United States Alkali Export Ass’n, Inc. v. United

States, 325 U. S. 196 (1945); Moore v. Illinois Central Rail

way, 312 U. 8. 630 (1941); cf. Levers v. Anderson, 326 U. S.

219 (1945) and Prendergast v. New York, 262 U. S. 43

(1923).

E. T h e sta te ad m in istrative agen cies are w ith ou t authority

and lack th e p ow er o f rem edy.

A reading of the state statutes reveals that the adminis

trative agencies to which petitioners might have appealed,

i. e., the county superintendent and the State Board of

Education, are without authority or power to decide the

question decided by the district court in favor of these

petitioners. They are not empowered to decide federal

29

constitutional law questions, cf. Hillsborough v. Cromwell,

supra. They are empowered to decide only questions of

school law. The State Board of Education has only the

power to render a decision in an appeal from a decision

of the county superintendent or the state superintendent.

Miss. Code (1942) § 6234. Decisions rendered by this Board

are final, but the Board has not been granted any power to

enforce its decisions, cf. United States Alkali Export

Ass’n, Inc. v. United States, supra. The county superin

tendent has similar limited authority. Miss. Code (1942)

§ 6261. These agencies are not granted the power to award

damages against school officials for unlawful or tortious

acts and are not granted power to enjoin unlawful conduct,

even when such conduct is violative of the school laws of

the state, cf. Federal Power Commission v. Panhandle

Eastern Pipe Line Co., supra; Georgia v. Penn. R. Co.,

supra. The right to bring a tort action is conferred by

Title 8 U. S. C. § 43. Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649

(1944) ; Picking v. Penn. R. Co. (C. A. 3), 151 F. (2d) 240

(1945) , as well as the right to bring an action for an in

junction, Hague v. C. I. 0., supra.

Georgia v. Penn. R. R. Co., supra, presents a case closely

analogous to the instant case. In that case, the plaintiff

was the State of Georgia. The defendants were some

twenty railroad companies. The complaint charged a con

spiracy among defendants in restraint of trade and com

merce among the states—alleging that defendants had fixed

arbitrary and noncompetitive rates and charges for trans

portation of freight by railroads to and from Georgia so

as to prefer the ports of other States over the ports of

Georgia. The complaint alleged that Georgia had no ad

ministrative remedy, the I. C. C. having no power to afford

relief against such a conspiracy. The prayer was for dam

ages and for injunctive relief.

30

Defendants, in their return to the rule to show cause

why Georgia should not be permitted to file its bill of com

plaint, alleged failure to state a cause of action because no

prior resort to I. C. C.

The Court held:

(1) “ This is a suit in which Georgia asserts claims

arising out of Federal laws—the gravamen of which run

far beyond the claim of damage to individual shippers

(452).

(2) “ Georgia does not seek in this action to enjoin

any tariff or to have any tariff provision cancelled. She

merely asks that the alleged rate-fixing combination and

conspiracy among the defendant-carriers be enjoined.

As we shall see, that is a matter over which the Com

mission has no jurisdiction (455). Congress has not

given the Commission * * * authority to remove rate

fixing combinations from the prohibitions contained in

the anti-trust laws (456). It has not placed these com

binations under the control and supervision of the Com

mission. Nor has it empowered the Commission to

proceed against such combinations and through cease

and desist orders or otherwise to put an end to their

activities.

(3) “ The present bill does not seek to have the

Court act in the place of the Commission. It seeks to

remove from the field of rate-making the influence of

a combination which exceeds the limits of the collabo

ration authorized for the fixing of joint through rates

(459). It seeks to put an end to discriminatory and

coercive practices. The aim is to make it possible for

individual carriers to perform their duty under the Act,

so that whatever tariffs may be continued in effect or

superseded by new ones may be tariffs which are free

31

from the restrictive, discriminatory, and coercive in

fluences of the combination. That is not to undercut

or impair the primary jurisdiction of the Commisson

over rates. It is to free the rate-making function of the

influences of a conspiracy over which the Commission

has no authority but which if proven to exist can only

hinder the Commission in the tasks with which it is

confronted (460).

“ What we have said disposes for the most part of

the argument that recognized principles of equity pre

vent us from granting the relief which is asked (460).

(4) “ Georgia alleges, ‘No administrative proceeding

directed against a particular schedule of rates would

afford relief to the State of Georgia so long as the

defendants remain free to promulgate rates by col

lusive agreement. Until the conspiracy is ended, the

corrosion of new schedules, established by the collusive

power of the defendant carriers acting in concert would

frustrate any action sought to be taken by adminis

trative process to redress the grievances from which

the State of Georgia suffers.’ Eate-making is a con

tinuous process. Georgia is seeking a decree which will

prevent in the future the kind of harmful conduct which

has occurred in the past. Take the case of coercion.

If it is shown that the alleged combination exists and

uses coercion in the fixing of joint through rates, only

an injunction aimed at future conduct of that character

can give adequate relief. Indeed, so long as the col

laboration which exists exceeds lawful limits and con

tinues in operation, the only effective remedy lies in

dissolving the combination or in confining it within

legitimate boundaries. Any decree which is entered

would look to the future and would free tomorrow’s

32

rate-making from the coercive and collusive influence

alleged to exist. It cannot of course be determined in

advance what rates may be lawfully established. But

coercion can be enjoined. And so can a combination

which has as its purpose an invidious discrimination

against a region or locality (461-462).

“ * * * There is no administrative control over the

combination. And no adequate or effective remedy

other than this suit is suggested which Georgia can em

ploy to eliminate from rate-making the influences of

the unlawful conspiracy alleged to exist here” (462).

In this case, the petitioners do not deny the power of

the respondent Board of Trustees to fix teachers’ salaries.

The trial court found that exclusive power to fix teachers’

salaries in the Jackson Separate School District is vested

in respondent Board of Trustees (R. 249, 250). As in

the case of Georgia v. Penn. R. Co., supra, the petitioners

do not seek to substitute the court for the Board of

Trustees. What they seek is to have unconstitutional

discrimination eliminated from the salary fixing process

in the future. Alston v. School Board (C. A. 4), 112

F. (2d) 992 (1940), cert, denied 311 U. S. 693. The

State Board in this case could not enjoin future discrimi

nation. Its only function is to render an opinion on a

written statement of facts. At best it has only the power

to recommend. In the words of this Court in United States

Alkali Export Ass’n v. United States, supra, at 210: “ It

can give no remedy. It can make no controlling findings of

law or fact. Its recommendations need not be followed by

any court or administrative or executive officer.”

33

II.

This case is not governed by Cook v. Davis (C. A. 5 ),

178 F. (2d) 595 (1949), cert, denied 340 U. S. 811.

A . T h e m a te r ia l f a c ts in th e C o o k ca se .

As pointed out in the petition for writ of certiorari

herein, the facts in this case are materially different from

the controlling facts in the Cook case. The crucial fact in

the Cook case was the role played by the State Board.

There the State Board, unlike the State Board in the in

stant case, had the power to fix teachers’ salaries, deter

mine the number of teachers to be employed by a local

board, and to classify all teachers. The local board was

compelled to pay the teachers employed by it the minimum

salary fixed in the State schedule and with the money paid

to it for that purpose by the State Board. The State Board

in that case had two schedules, one for Negro teachers and

one for white teachers. The schedule adopted by said

Board for Negro teachers had uniformly lower rates of pay

than the schedule adopted for white teachers.

The local board could supplement the salaries fixed by

the State Board. This was done by the local board in adopt

ing a new salary schedule after the suit was instituted in

that case. The new schedule was one of the most com

plicated teacher salary schedules ever devised. It estab

lished four categories of teachers. In each category there

were three to four so-called “ Tracks”. On each “ Track”

there were sixteen to nineteen steps. The system could not

even be explained with sufficient clarity by those who de

vised it. Despite this, however, the new schedule, in the

opinion of the court below, was free of the unconstitutional

discrimination which previously existed under a supple

mentary dual schedule. The court below was therefore of

34

the opinion that the discrimination which existed at the

time the district court issued its decree resulted from the

discrimination by the State Board which was not a party

to the proceeding.

After the new schedule was adopted in the Cook case,

a procedure was instituted whereby a teacher aggrieved by

the action of the Superintendent in placing such teacher on

a particular “ Track” could appeal to the local board and

then to the State Board. This procedure had specific refer

ence to grievances concerning the new schedule. The plain

tiff in the Cook case had been placed on a “ Track” by the

superintendent. He did not allege that he was aggrieved

thereby, nor did he appeal to the local board or the State

Board. It therefore appeared that that particular plain

tiff had no cause to complain. And since the remaining

general discrimination against the other members of the

class which the plaintiff represented resulted from the

action of the State Board, the court below was of the opin

ion that the district court should retain jurisdiction until

the State Board had been asked to cease its discriminatory

practice or until the State Board would be brought in as

a party defendant for refusing to do so.

B. T h e m a te r ia l f a c ts in th e in s ta n t case .

In this case, the State Board of Education gives to the

local board a sum determined on a per capita basis. Miss.

Code (1942) § 6219. This applies also to the appropriations

made in 1950 to help equalize Negro teachers’ salaries (Ap

pendix, pp. 84-90). Once this amount has been transmitted,

the State Board has no authority to say what portion shall

be paid in salaries. The State Board, with respect to the

respondent Board, has no power with respect to the teacher

salary scale and had no salary schedule of its own applicable

to the Separate School District involved in this suit. The

35

exclusive power to determine teachers ’ salaries is vested in

the respondent local board and the trial court so found

(E. 249).

The statutes on which respondents rely are, by their

own terms, inapplicable. The appeal to the State Board,

Miss. Code (1942) § 6234, is from the decision of the county

superintendent or the state superintendent. The county

superintendent, however, has no control over the school

matters of a separate school district, such districts being

autonomous, especially with respect to the teachers it em

ploys and the salaries fixed. Miss. Code (1942) § 6423.

Therefore, the provision relating to appeals to the county

superintendent would not be available to petitioners. Miss.

Code (1942) §6261. The provision relating to the advise

of the state superintendent may be invoked only by the

county superintendent. Miss. Code § 6240-07. And, unlike

the Cook case, there is no appeal procedure which is spe

cifically applicable to teacher salary disputes.

After this suit was instituted, the respondent local board

did not adopt a new salary schedule. The salary schedule

which was then in existence was a very simple one in opera

tion. A stipulated salary was usually recommended by the

respondent Superintendent of Schools along with his gen

eral recommendation to the respondent board. Both recom

mendations were generally approved by the respondent

board (E. 250).

When a teacher was dissatisfied with the salary recom

mended by the Superintendent or approved by the board,

there was no appeal procedure which was specifically ap

plicable to teacher salary grievances. The reason for this

was, undoubtedly, that the decision of the board was final.

A teacher who felt that the salary offered was insufficient

could decline to enter into the contract.

36

Before commencing the instant suit, petitioner Gladys

Noel Bates, petitioned the respondent board on behalf of

herself and all other Negro teachers and principals in the

Jackson Separate School District who were similarly situ

ated (R. 89), In reply, the respondent board said that no

such discrimination existed. An appeal was therefore

taken to the only administrative agency which had juris

diction with respect to the salaries of teachers in the Jack-

son Separate School District. And since the action of this

board is final, petitioner could only resort to a court for

relief. Petitioner chose to resort to the federal district

court to enforce the right conferred on her by Title 8

U. S. C. § 43 inasmuch as her complaint was not one limited

to her individual salary, but a complaint of unconstitutional

discrimination against a class of teachers of which she was

a member. The right to bring an action to enjoin such

discrimination initially in a federal district court is spe

cifically and unequivocally provided by Title 28 U. S. C.

§1343(3).

In affirming the judgment of dismissal, the court below

did not direct the district court to retain jurisdiction as was

done in the Cook case, until the alleged administrative

remedy had been exhausted, thus indicating that the district

court was without jurisdiction until the so-called adminis

trative remedies had been exhausted.

The Cook case, contrary to the decision of the court

below, is not “ dispositive” of this case, the material and

controlling facts being substantially different.

37

Conclusion.

"Wh er efo r e , i t is re s p e c tfu lly su b m itte d th a t th is p e t i