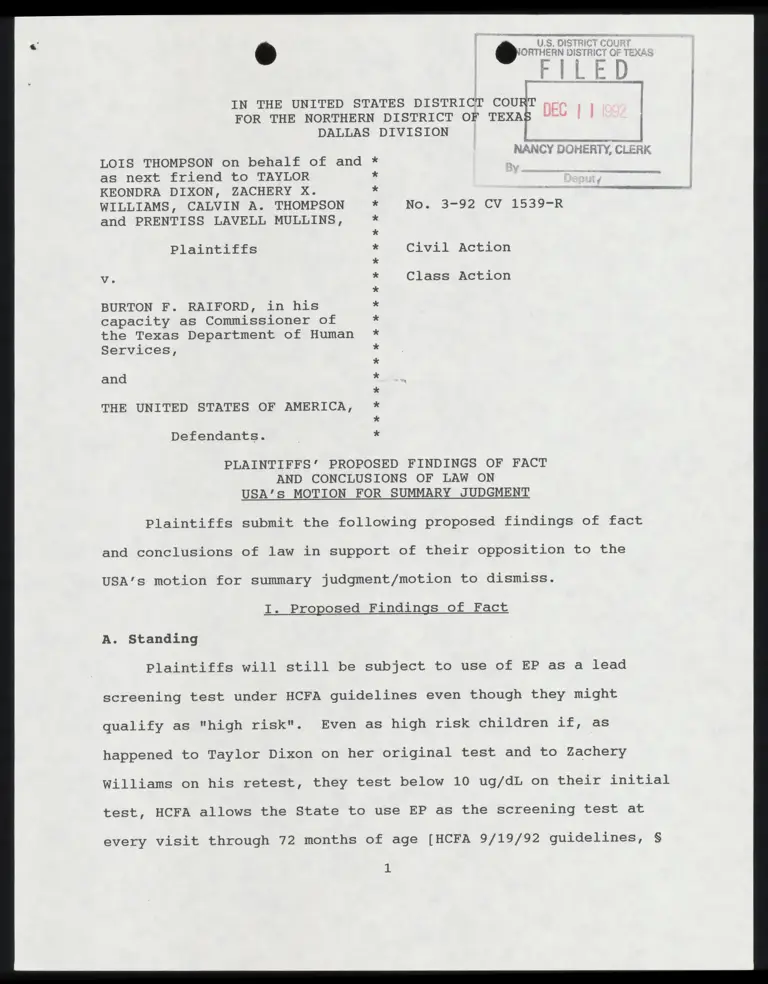

Plaintiff's Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law on USA's Motion for Summary Judgement

Public Court Documents

December 11, 1992

21 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thompson v. Raiford Hardbacks. Plaintiff's Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law on USA's Motion for Summary Judgement, 1992. 031318e7-5c40-f011-b4cb-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f8a66d97-0586-4326-ad83-c5bb2799b195/plaintiffs-proposed-findings-of-fact-and-conclusions-of-law-on-usas-motion-for-summary-judgement. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS “~~ | |

DALLAS DIVISION

I.

NANCY DOHERTY, CLERK

LOIS THOMPSON on behalf of and

as next friend to TAYLOR

KEONDRA DIXON, ZACHERY X.

WILLIAMS, CALVIN A. THOMPSON

and PRENTISS LAVELL MULLINS,

A —— i.

No. 3-92 CV .1539~R

Plaintiffs Civil Action

Vv. Class Action

BURTON F. RAIFORD, in his

capacity as Commissioner of

the Texas Department of Human

Services,

and

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

%

%

%

%

%

%

N

O

X

%

%

%

OX

%X

%

¥

¥

X

¥

%*

*

Defendants.

PLAINTIFFS’ PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT

AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW ON

USA’s MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

Plaintiffs submit the following proposed findings of fact

and conclusions of law in support of their opposition to the

USA’s motion for summary judgment/motion to dismiss.

I. Proposed Findings of Fact

A. Standing

Plaintiffs will still be subject to use of EP as a lead

screening test under HCFA guidelines even though they might

qualify as "high risk". Even as high risk children if, as

happened to Taylor Dixon on her original test and to Zachery

Williams on his retest, they test below 10 ug/dL on their initial

test, HCFA allows the State to use EP as the screening test at

every visit through 72 months of age [HCFA 9/19/92 guidelines, §

1

5123.2 D.1.c.(2)]. Using the HCFA guidelines, Taylor Dixon will

be screened using the admittedly ineffectual EP test during the

period of her life when the most rapid rate of increase in blood

lead levels will occur. "Blood lead concentrations increase

steadily up to at least 18 months of age. The most rapid rate of

increase occurs between 6 and 12 months of age." [CDC 1991, page

42]

The USA’s argument that the HCFA guidelines clearly require

the use of the blood lead test is contradicted by the plain

wording of the HCFA guidelines.

The Sept. 19, 1992 HCFA guidelines for "High Risk" children

specifically distes: "If the initial blood lead level test

results are less than (<) 10 micrograms per deciliter (ug/dL), a

screening EP test or blood lead test is required at every visit

prescribed in your EPSDT periodicity schedule through 72 months

of age." [HCFA 9/19/92 guidelines 5132.2 c. Screening Blood

Tests. (2) High Risk].

The HCFA guidelines plainly state :"States continue to have

the option to use the EP test as the initial screening blood

test."

"As part of the nutritional assessment conducted at each

periodic screening, an EP blood test may be done to test for iron

deficiency. This blood test may also be used as the initial

screening blood test for lead toxicity."

These statements are completely consistent with the position

that the States are still allowed to use the EP test even for

high risk children.

The HCFA guidelines do not support a finding that plaintiffs

will not still be subject to the use of the EP test as a lead

screening blood test.

The USA also argues that there has been a change in the

Texas procedures for lead screening which demonstrates

plaintiffs’ lack of standing. The State’s memorandum in opposi-

tion to the class motion alleges that EP was discontinued as a

screening device as of Oct. 23, 1992. Therefore, the USA argues,

plaintiffs have lost standing if they ever had it. The State has

not introduced any evidence that EP will not be used as screening

device. The only evidentiary material filed by the State is the

Cook affidavit filed with the opposition to motion for class

certification. That affidavit says only that the State of Texas

has obtained and put into use, as of Oct. 23, 1992, the equipment

to conduct blood lead tests on all specimens received for blood

lead testing. The State introduced no evidence to show that the

EP test has been eliminated or under what circumstances even high

risk children will receive blood lead tests.

Plaintiffs introduced the State of Texas January 1992 EPSDT

Screening Manual [copy attached to Beshara declaration]. If the

State follows the periodicity schedule or the follow-up care

guidelines in that manual, then neither Taylor Dixon nor Zachery

Williams will receive another blood lead test as part of their

EPSDT screening. The other two plaintiff children will only be

considered for rescreening. All four plaintiffs will receive EP

tests at every screening interval.

Plaintiffs also introduced the State of Texas "Laboratory

Screening Services" publication [copy attached to Beshara decla-

ration]. The State of Texas January 1992 EPSDT Screening Manual

refers to the Laboratory Screening Services publication stating

"The Handbook provides supplementary information on required

laboratory test procedures, interpretation of lab test results,

guidelines and criteria for referral and follow-up and instruc-

tions on specimen collection and handling." The Handbook re-

quires the use of the EP test as the "primary screening test for

lead" [page 6]. The Handbook provides for the use of a blood lead

test only if the EP level is greater than 35 ug/dL. This is

exactly the procedure that the State of Texas has been following

even though the January 1992 EPSDT Screening Manual has required

at least one blood lead test [Kelley letter, copy attached to

Beshara Declaration, page 2 and attachment "Lead Blood Tests"].

The State’s evidence that it has its own blood lead testing

equipment and that it will use it on all specimens marked for

blood lead testing does not negate or contradict the proposition

that plaintiffs will receive only one blood lead test if that

initial test results in a blood lead level < 10 ug/dL. If the

periodicity schedule and follow-up care guidelines are followed,

the only specimens which will be marked for blood lead testing

will be the initial test. If that test result is < 10 ug/dL, no

subsequent specimens will be marked for blood lead testing.

The summary judgment evidence demonstrates that at least two

of the plaintiffs, Taylor Dixon and Zachery Williams, will

continue to be subject to the use of the EP test as a screening

test for lead poisoning.

B. Merits

The USA argues that its new HCFA guidelines comply with the

CDC guidelines and therefore comply with the Medicaid Act provi-

sion at issue, 42 U.S.C. 1396d(r)(1)(B)(iv). Even if this was a

good legal argument, the facts do support the assertion. There

are substantial differences between the relevant CDC childhood

lead poisoning prevention and treatment provisions and the HCFA

guidelines.

The chart attached to these findings compares the CDC, HCFA,

Texas January 1992 EPSDT Medical Screening Manual, and the Texas

"Laboratory Screening Services" handbook provisions on the timing

and type of blood test for children under 72 months of age shows

that there are considerable differences between the CDC screening

guidelines and the screening which children such as plaintiffs

will receive under either the HCFA or the Texas EPSDT guidelines.

There are other critical differences between the CDC State-

ment and the HCFA guidelines.

The USA alleges that the HCFA guidelines are compatible with

the CDC’s 1991 position on the use of verbal questions to deter-

mine whether a child is at high or low risk. The USA then uses

this fact to imply that the HCFA guidelines allowing the use of

the EP test for "low risk" children are also compatible with the

1991 CDC statement. This implication is false. The CDC 1991

statement allows the use of verbal questions to determine high or

low risk only if the child is given a blood lead level test no

matter what the risk characterization.

Page 42 of the October 1991 CDC statement unequivocally

states "The questions are not a substitute for a blood lead

test." (emphasis in the original).

HCFA itself has recognized the need to confirm the verbal

screening with a blood lead test no matter what category of risk

the answers would seem to justify. "We agree that responses to

questions are not a substitute for a blood lead test." [Aug. 6,

1992 letter from Christine Nye, Director Medicaid Bureau, to

Julius Chambers, Director-Counsel NAACP Legal Defense and Educa-

tional Fund, Inc. attached to interveners’ complaint].

The Federal Centers for Disease Control states "Screening

should be done using a blood lead test. Since erythrocyte proto-

porphyrin (EP) is not sensitive enough to identify more than a

small percentage of children with blood lead levels between 10

and 25 ug/dL and misses many children with blood lead levels > 25

ug/dL (McElvaine et al., 1991), measurement of blood lead levels

should replace the EP test as the primary screening method."

[CDC, "Preventing Lead Poisoning in Young Children", 1991, page

417+

The new HCFA guidelines allow the use of EP testing for the

follow up screening of high risk children whose initial blood

lead level test results in a finding < 10 ug/dl. "If the initial

blood lead test results are less than (<) 10 micrograms per

deciliter (ug/dL), a screening EP test or blood lead test is

required at every visit prescribed in your EPSDT periodicity

schedule through 72 months of age." [HCFA 5123.2.D.c(2) High

Risk]. CDC 1991 requires all subsequent screening to be done

using the blood lead test [CDC 1991 page 44].

The EP test does not provide for the assessment of blood

lead levels.

The USA alleges as a fact that the continued use of the EP

test is based on the USA’s taking into account the current

advances in scientific knowledge about lead screening procedures.

This allegation is disputed by the significant sources of scien-

tific knowledge about the use of EP as a lead screening procedure

which contradict the USA’s position. One of these scientific

sources is a study and report authored in part by the USA’s

affiant, Sue Binder, MD.

Dr. Binder is an author of the article "Evaluation of the

erythrocyte protoporphyrin test as a screen for elevated blood

lead levels" October 1991, Journal of Pediatrics, 548-550 [copy

attached to Declaration of Laura Beshara]. Dr. Binder’s study

reported that the EP test was able to detect only 26% of the

children with elevated blood lead levels > 10 ug/dL [table page

549]. The report concludes "For identification of the children

with BPb levels of 10 to 24 ug/dl, another screening method,

probably BPb measurement, will be needed" [page 550].

The federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry

[ATSDR] filed its "The Nature and Extent of Lead Poisoning in

Children in the United States: A Report to Congress" in 1988. The

Report analyzed the existing research on the reliability of the

EP test as a screening test for lead poisoning. "Analysis of data

from the second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

(NHANES II) by Mahaffey and Annest (1986) indicates that Pb-B

levels in children can be elevated even when EP levels are

normal. Of 118 children with Pb-B levels above 30 ug/dl (the CDC

criterion level at the time of NHANES II), 47% had EP levels at

or below 30 ug/dl, and 58% (Annest and Mahaffey, 1984) had EP

levels less than the current EP cutoff value of 35 ug/dl (CDC,

1985)". HHS concluded "This means that reliance on EP level for

initial screening can result in a significant incidence of false

negatives or failures to detect toxic Pb-B levels."[copy attached

to Beshara Declaration page II-9].

The 1991 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

"Strategic Plan for the Elimination of Childhood Lead Poisoning"

correctly forecast the 1991 CDC actions lowering the level of

blood lead which should be taken as a symptom of lead poisoning.

"In 1991 CDC will likely issue new recommendations suggesting

that screening programs attempt to identify children with blood

lead levels below 25 ug/dL." HHS, "Strategy", 1991, page 23. The

HHS "Strategic Plan" correctly stated that the CDC action should

mean an end to the use of EP testing for childhood lead screen-

ing. "This change will mean that blood lead measurements must be

used for childhood lead screening instead of EP measurements."

HHS, "Strategy", 1991, page 23 (emphasis added) [attached to

Declaration of Laura Beshara].

The USA knows that the EP test is not an appropriate lead

blood level assessment for any age and risk factors. The 9/19/92

HCFA amendment acknowledges this. "The erythrocyte protoporphyrin

(EP) test is not sensitive for blood lead levels below 25 ug/dL."

The HHS "Strategic Plan for the Elimination of Childhood

Lead Poisoning", 1991 states "At present it is much cheaper and

easier to perform an EP test than a blood lead measurement;

however, the EP test is not a useful screening test for blood

lead levels below 25 ug/dL." [Page 40, attached to Beshara

Declaration]. The USA’s affiant, Sue Binder, MD., is a principal

author of the "Strategic Plan".

The Hiscock Geciavaiicn admits that the EP test does not

measure blood lead levels and that only the blood lead test

directly measures blood lead levels [Hiscock Declaration q 9.,

page 5]. The EP test measures only the level of erythrocyte

protoporphyrin in the blood [Hiscock Declaration { 9; Binder

Declaration q 14].

If the EP test is used as an assessment of blood lead

levels, only 27% of the children whose actual blood lead levels >

10 ug/dL will be identified [Binder study table page 549, at-

tached to Beshara declaration].

The EP test does not provide an assessment of blood lead

levels at any level [Rosen affidavit pages 8-9]. The EP test

discovered only 73% of the high risk children with blood lead

levels > 25 ug/dl in the Binder study area. The EP test accurate-

ly assessed only 26%, 42%, and 50% of the high risk children with

elevated lead levels in other national and local studies [Binder

study page 549, results of NHANES II overall and high risk

subset, and Oakland study [attached to Beshara Declaration].

C. Capacity

The USA argues that an alleged lack of capacity to conduct

blood lead testing by some unspecified number of unnamed states

justifies its continued support for the use of the EP test.

Whether or not such a lack of capacity would legally justify the

violation of the Medicaid Act, there is no evidence to support a

finding that there is any such lack of capacity.

The USA’s only evidence are the general allegations in its

pleadings and affidavits that there is a lack of capacity. The

plaintiffs’ and interveners’ evidence in response to this allega-

tion furnishes specific and concrete evidence that there is ample

blood lead testing laboratory capacity throughout the country.

For any location without inhouse capacity for blood lead testing,

the current nationwide laboratory testing services provide the

capacity for the blood lead level testing. These laboratories

are available to any location with express mail service [Nicar

Declaration; Rosen affidavit].

Plaintiffs also introduced, in support of their class

certification motion, a federal "OSHA List of Laboratories

Approved for Blood Lead Analysis Based on Proficiency Testing"

[plaintiffs’ class certification exhibit #11]. This list pro-

vides the name and address of CDC certified proficient blood lead

10

testing laboratories in 46 states and Washington, D.C.

There is no lack of "capacity" if HCFA is really willing to

pay for blood lead level testing for all Medicaid eligible

children.

II. Proposed Conclusions of Law

A. Standing

At least two of the plaintiffs will continue to be subject

to the use of the EP test as part of the EPSDT lead poisoning

screening procedures. This satisfies the injury in fact element

of standing.

There is no doubt that the USA’s support for the use of the

EP test is a factor in the States continued use of the test. The

structure of the Medicaid Program is such that if the USA had

disapproved of the EP test and refused to reimburse the States

for its use, the States would not use EP in the Medicaid EPSDT

program. The causation element is satisfied.

Here the redressability and causation requirements are

corollaries. Just as the USA’s continued support for the EP test

has been a causal factor in the States’ use of the test, if the

USA would cease its support for the EP test and pass regulations

requiring the use of the blood lead test for childhood lead

poisoning screening, the injury to the plaintiffs and the plain-

tiff class would be remedied. The injunctive relief requested

seeks such a remedy.

B. Adequate Remedy Under APA

The USA argues, for the first time in its reply to

11

plaintiffs’ response to the motion for summary judgment, that the

APA, 5 U.S.C. § 704, prohibits this action against the USA

because the plaintiffs have an adequate remedy against the State

in a § 1983 claim. The reply was not received by plaintiffs

until December 9, 1992 when plaintiffs’ counsel called and asked

for a copy to be FAXed. The mailed copy was received on December

10, 1992. The reply to a response to a motion for summary

judgment filed less than a week before argument on the motion is

not the appropriate time to raise an entirely new legal argument.

The USA’s reply should have been just that, a reply brief, not a

new basis alleged at a time when plaintiffs have no opportunity

to research, brief and respond. If the USA wants to make this

argument, it must do so in the proper procedural framework.

In at least one area of the relief requested, the retesting

and follow-up treatment for children screened by use of the EP

test, the remedy against the State defendant will not be ade-

quate. Plaintiffs have requested that the federal government

finance the retesting, using the blood lead test, of all Medicaid

children who have been $1legally screened using the EP test. The

federal government’s financial support for such retesting would

be required in order for such relief to be granted. A suit only

against the state would provide no basis to compel the federal

government to provide this support.

C. Does the statute require a blood lead test?

The Medicaid Statute Prohibits any use of the EP test.

The Medicaid Act requires "lead blood level assessment

12

appropriate for age and risk factors" for children who are

screened under the EPSDT program. 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(r)(1)(B) (iv).

The statute’s plain and unambiguous language requires the

use of "lead blood level assessment." No where in the statute or

in the legislative history does Congress express an intention for

the states to use the Erythrocyte Protoporphyrin (EP) test. As

plaintiffs’ response indicates and as defendant USA admits, the

EP test does not measure the lead in a child’s blood at all.

The USA’s policy argument is that the states should be

allowed to use the EP test as a device for lead poisoning screen-

ing for the poor children of our country until some unknown

future date. The policy argument of the USA acting through HCFA

must be rejected. Administrative interpretation of a statute

contrary to the plain language of the statute is not entitled to

deference by the courts. Demarest v. Manspeaker, __ U.S. 184,

112 L.Ed.2d 608, 616 (1991); see Public Employees Retirement

System of Ohio v. Betts, = U.S. _ , 106 L.Ed.2d 134, 150-151

(1989). If Congress had wanted to the states to use a test that

did not detect for levels of lead in the blood Congress could

have said so in the statute. Congress did not choose to do that.

Instead, Congress made a policy decision to have EPSDT children

screened with a blood lead level test. The policy decision has

been made by Congress and defendant USA should not be allowed to

change it.

when the language of the statute is unambiguous, judicial

inquiry is complete except in rare and unusual circumstances.

13

Demarest v. Manspeaker, U.S. _ , 112 L.Ed.2d 608, 616 (1991);

Burlington Northern R. Co. v. Oklahoma Tax Comm’n, 481 U.S. 454,

461 (1987); Rubin v. United States, 449 U.S. 424, 430 (1981).

The language of the Medicaid Act is unambiguous. It states that

"laboratory tests (including lead blood level assessment appro-

priate for age and risk factors)" are required for EPSDT chil-

dren. 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(r)(1)(B)(iv). From the face of the

statute, a laboratory test that detects levels of lead in the

blood is required and not a test that does not even detect levels

of lead such as the EP test.

The USA contends that EP is "appropriate for age and risk"

and that it therefore is consistent with the statute. The record

of the EP test, as set out in plaintiffs’ response, shows that it

is not an appropriate test for any person at risk. There is more

to the statute than that selective phrase. The entire statute

states that EPSDT screening must provide for "laboratory tests

(including lead blood level assessment appropriate for age and

risk factors)." 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(r)(1)(B)(iv). The entire

statute makes it clear that blood lead tests are required.

This is not one of those rare circumstances as in Griffin v.

Oceanic Contractors, Inc., 458 U.S.564, 571 (1982), where the

literal or usual meaning of the statute would thwart the purpose

of the statute. The literal or usual meaning of the statute at

issue here would require a blood lead level assessment that would

detect the level of lead in a child’s blood in order to determine

14

if that child had lead poisoning.? The purpose of the EPSDT

statute and the 1989 amendments is to provide health care to poor

children. 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396d(r); Report of the House Budget

Committee, Explanation of the Energy and Commerce and Ways and

Means Committees Affecting Medicare-Medicaid Programs, 101 Cong.

1st. Sess., p. 398 (September 20, 1989). The literal or usual

meaning of the statute is consistent with that purpose and would

require a blood lead test that could detect levels of lead so

that poor children with lead poisoning could be diagnosed and

treated. The EP test is inappropriate with the overall purpose

of the Medicaid Act and the EPSDT scheme. The EP test does not

detect levels of lead in the body and as is evident through

defendant ’s many admissions, is a useless screening test for

childhood lead poisoning.

The USA contends that since the legislative history of the

Medicaid Act is silent on the issue of whether a blood lead test

or EP should be required then this silence supports its argument

that the USA can allow the use of the EP test by the states.

Legislative history, however, is irrelevant where the language of

the statute is plain. While "legislative history can be a

legitimate guide to a statutory purpose obscured by ambiguity, in

the absence of a clearly expressed legislative intention to the

contrary, the language of the statute itself must ordinarily be

1 The definition of lead poisoning has been recently changed

by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). The new level of

concern is 10 ug/dL of lead in the blood for even at this low

level adverse health effects can occur in young children.

15

regarded as conclusive." Burlington Northern R. Co. v. Oklahoma

Tax Comm’n, 481 U.S. 454, 461 (1987). Lack of legislative

history does not prevent the Court from applying the plain

language of the statute and requiring the USA to support a blood

lead test for EPSDT children.

Congress enacted amendments to the Medicaid Act in 1989.

Those amendments included the addition of blood lead testing for

EPSDT children. OBRA ‘89 § 6403, now 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(r). The

addition of a "lead blood level assessment" was made after the

1998 Report to Congress, "The Nature and Extent of Lead Poisoning

in Children in the United States," by the U.S. Dept. of Health

and Human Services Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease

Registry, which indicated that EP was not a useful screening

device for detecting levels of lead in the blood of children.

The USA now argues that the statute does not have the "narrow,

technical meaning" of a blood lead test in spite of the plain

words of the statute. The USA would like to ignore the plain

language of the 1989 amendment in favor of the earlier version of

the statute that does not have the language requiring "lead blood

level assessment." It is not the function of the courts,

however, to decide whether or not the amendment is better. The

plain language of the statute controls. West Virginia Univ.

Hospitals, Inc. v. Casey, U.S. , 113 L.E4.2d 68, 84 (1991).

As Justice Brandeis has explained, the expansion of a

statute beyond its plain language is not a role for the courts:

[The statute’s] language is plain and unambiguous. What the

Government asks is not a construction of a statute, but, in

16

effect, an enlargement of it by the court, so that what was

omitted, presumably by inadvertence, may be included within

its scope. To supply omissions transcends the judicial

function.

Iselin v. United States, 270 U.S. 245, 250-51 (1926). The USA

should not be allowed to expand the clear language of the statute

requiring a blood lead test to include a useless test that does

not detect lead.

D. Lack of Capacity

The lack of capacity argument by the USA is both a factual

argument and a legal argument. The USA argues that there are

states that do not have the capacity to perform blood lead

testing. The argument never proceeds beyond the statement of the

ultimate cohcludion: The USA provides no particulars. The USA

names no specific states without "capacity." The USA does not

explain why any state cannot or does not have this "capacity."

This bald, unsupported general allegation does not prove, or tend

to prove, any facts.

The USA's legal argument is not made but must rather be

implied from the factual argument. Assume that there are,

somewhere, states without the capacity to draw small amounts of

blood from little children, put it in a tube, and deliver it to a

laboratory inside or outside the state. The USA must be arguing

that this lack of capacity excuses performance from the statute.

It is a lame excuse for noncompliance with the statute. The

U.S. Congress, in 1989, told each state that if it was going to

participate in the federal Medicaid/EPSDT program that it had to

provide such blood lead testing in return for the federal funds

17

necessary to do the testing. 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(r)(1)(B)(iv). A

state’s refusal to provide the capacity to collect and analyze

blood samples for lead content should not be a defense to a clear

violation of the statute. This is the last decade of the twenti-

eth century. We have put persons on the moon. The USA is not a

third world country which needs to import United Nations medical

teams to test its children for lead poisoning.

Unwillingness or self-imposed inability to provide a re-

quired service does not excuse a state from compliance with the

Medicaid statute. "Texas, like most states, has taken a bite out

of the carrot of cooperative federalism and is, accordingly,

subject to the federal stick -- the minimum mandatory require-

ments set forth in the Medicaid legislation." Mitchell v. Johnst-

on, 701 F.2d 337, 340 (5th Cir. 1983) (state could not limit

EPSDT dental care to checkups every three years).

The lack of capacity argument also fails as an argument

against plaintiffs having standing. The USA argues that if the

requested relief is granted (blood lead tests for all regardless

of high or low risk) then the lack of capacity means that high

risk kids will be delayed in getting the blood lead tests because

they may be behind low risk kids waiting for the tests. The lack

of capacity argument really boils down to the USA not wanting to

follow the statute.

If the USA wanted poor children to have the benefit of a

blood lead test then there are several national laboratories

willing and available to do such analysis. See Declaration of Dr.

18

Michael J. Nicar; affidavit of Dr. Rosen. The lack of capacity

is a camouflage for the federal government’s real interest in

promoting the use of the EP test -- saving money. See Dr. Bind-

er’s article [copy attached to Beshara declaration].

The capacity argument, if accepted, would also negate the

other part of the USA’s argument -- the states must use blood

lead testing for high risk children. If a state lacks capacity

to perform blood lead tests for low risk children and that lack

is excused, the same lack of capacity would prevent the use for

high risk children and would also be excused. The USA should not

be allowed to hide behind the ambiguities of the word "capacity"

to avoid the statute’s mandate.

E. HCFA guidelines and CDC

The United States says in its brief that the delay in the

HCFA guidelines for a "transition" period for the states to

change over to blood lead testing is consistent with the October

1991 CDC statement.

Plaintiffs have a simple reply. To the extent that the

October 1991 CDC statement calls for a transition period then the

CDC statement is inconsistent with the Medicaid statute. The

statute mentions nothing about a transition period. 42 U.S.C. §

1396d(r)(1)(B) (iv). The statute mentions nothing about allowing

a transition period for these poor children because this would be

a good area for the federal government and the states to save

some money by using a useless screening test. The CDC statement

is an official publication of defendant United States. The

19

extent to which the CDC statement is inconsistent with the

statute is simply more evidence that the United States continues

to harm the plaintiffs and the class.

III. Conclusion

The USA has failed to show that it is entitled, as a matter

of law, to a judgment dismissing the case. The motions for

summary judgment and to dismiss should be denied.

Respectfully Submitted,

MICHAEL M. DANIEL, P.C.

3301 Elm Street

Dallas, Texas 75226-1637

(214) 939-9230

(214) 939-9229 (FAX)

oo) on /

| \ 4

By: am Uo. Nero oo”

Michael M. Dani@l

State Bar No. 05360500

) ¢ ATR TH 3 By: XNA (SNR

“Laura B. Beshara

State Bar No. 02261750

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that a true and correct copy of the above doclment

A

was served upon counsel for defendants by FAX on this the //Aday

of December, 1992.

Suna Fin} Kehaia

““T,aura B. Beshara

20

CDC October 1981 Screening requirements * HCFA 9/19/92 guidelines * Texas January 1992 EPSDT Medical Screening * Texas "Laboratory Screening Services"

[plaintiffs' exhibit #14, page 44] * [plaintiffs' exhibit #3] * [plaintiffs' exhibits # 10—10C] * [plaintiffs’ exhibit #5, pages 5—13]

I. High risk according to questions * |. High risk according to questions * |. High risk according to questions * Primary screening test for lead is EP.

= - - : mk . - - - - 4 = - -* A blood lead level is run only when

Initial blood lead level test at 6 months * Initial blood lead level test at 6 months * Initial blood lead level test at 6 months * EP = or > 35 ug/dL.

* %* *

If test < 10 ug/dL, * |ftest < 10 ug/dL, * |f test < 10 ug/dL, then * All of the retesting standards are in

then blood lead level test every 6 months. * then blood lead level OR EP test according * no rescreening required under periodicity or followup care * terms of the EP test results.

* to State's periodicity schedule [In Texas, never]. * guidelines. * There is no high or low risk determination.

* * * Atleastas of July, 1992, Texas was still

If test = or > 10 ug/dL but <15, * |f test = or >10 ug/dL, then * |f initial blood lead test 10—14, then * following these standards.

then blood lead test every 3 or 4 months until level decreases, * follow up "blood tests" left to professional _* "consider rescreening" under follow-up care guidelines. *

* judgment with reference to CDC Statement. * *

If test = or >15 but <20, then * Both blood lead and EP are "blood tests". * |f initial blood lead test 15—19, then :

then blood lead test every 3 or 4 months until level decreases, * * rescreen in 3 months under follow —up care guidelines. *

* * *

If test = or > 20, then & * |f initial blood lead test 20—69, then *

then blood lead test every 3 or 4 months until level decreases, * * "monitor blood lead" under follow—up care guidelines. *

* * *

Il. Low risk according to questions * |. Low risk according to questions * |I. Low risk according to questions *

- - - x ————— — pv. J -— - -%

initial blood lead level test at 12 months. * |nitial EP OR blood lead test at 12 months. * |nitial blood lead level test at 6 months, x

% * no other blood lead level test required at *

If test < 10 ug/dL, then * * any age under Texas periodicity schedule. The EPtestis *

blood lead level test at 24 months. * * mandatory for each nutritional assessment. *

* * *

If test 10—14 ug/dL, then * * ®

then blood lead test every 3 or 4 months until level decreases, * * Li

* * *

If test = or >15 ug/dL, then x : *

blood lead level test every 3 or4 months. * * x

* * *

Second blood lead level test at 24 months. * Second EP OR blood lead test at 24 months. 3 *

* *

* %* Ill. Rescreening of plaintiffs given initial blood lead test results and assuming high risk status

Taylor's first test was 9 ug/dL [ plaintiffs’ exhibit #9].

Under CDC, she would receive a blood lead

test within 6 months.

Zachery's first test was 21 ug/dL but

he was retested at 7 ug/dL [plaintiffs' ex. #8A]. Under CDC

he would receive another blood lead

test not later than 6 months and possibly

within 3 to 4 months until level decreases.

Calvin's first test was 19 ug/dL but

he was retested at 14 ug/dL [plaintiffs’ ex #9B]. Under CDC

he would receive another blood lead

test within 3 to 4 months until level decreases.

Prentiss’ first test was 18 ug/dL but

he was retested at 14 ug/dL [plaintiffs’ ex #9C]. Under CDC

he would receive another blood lead

test within 3 or 4 months until level decreases. *

%

%

%*

%

%

%

%

%

X

%

%

%

%

%

%

%

*

»

-

(O

F

JA

S

C

E

RE

RE

E

E

S

E

BR

i

N

E

E

L

a

E

BE

BE

ER

SU

L

SS

aE

|

Under HCFA, Taylor could receive a retest

using EP or blood lead according to

the State periodicity schedule.

Under HCFA, Zachery could recieve a retest

using EP or blood lead according to

the State periodicity schedule.

Under HCFA, any followup tests for Calvin

would be "blood tests" with “reference

to CDC statement" and professional

judgment.

Under HCFA, any followup tests for Prentiss

would be "blood tests" with "reference

to CDC statement" and professional

judgment.

Under this State standard, Taylor will

receive no rescreening except for the EP test given as

part of the nutritional assessment.

Under this State standard, Zachery will

receive no rescreening except for the EP test given as

part of the nutritional assessment.

Under this State standard, Calvin will only

be considered for rescreening other than the EP test

given as part of the nutritional assessment.

Under this State standard, Prentiss will only

be considered for rescreening other than the EP test

given as part of the nutritional assessment.

* Under this standard, none of the plaintiffs

* will receive any rescreening except for the

* periodic EP test.

*

*

0%

%*

%

%

%

%

%*

%

¥

%

%

¥

¥

%*