Defendant's Response to Interrogatories, Martha Kirkland

Public Court Documents

February 26, 1986

8 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Defendant's Response to Interrogatories, Martha Kirkland, 1986. a5731ba9-b8d8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f8dba87d-238f-4a5f-b7da-994572bcfdfa/defendants-response-to-interrogatories-martha-kirkland. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

NORTHERN DIVISION

JOHN DILLARD, ET Al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs, CIVIL ACTION NO. 85-T-1332-N

CRENSHAW COUNTY, ALABAMA,

ET AL.,

N

p

,

Me

ng

R

p

t

:

Aa

ge

nd

Ru

ng

e:

Sm

go

l

Se

ng

?

N

i

g

No

un

g

Rr

ni

pa

?

Defendants.

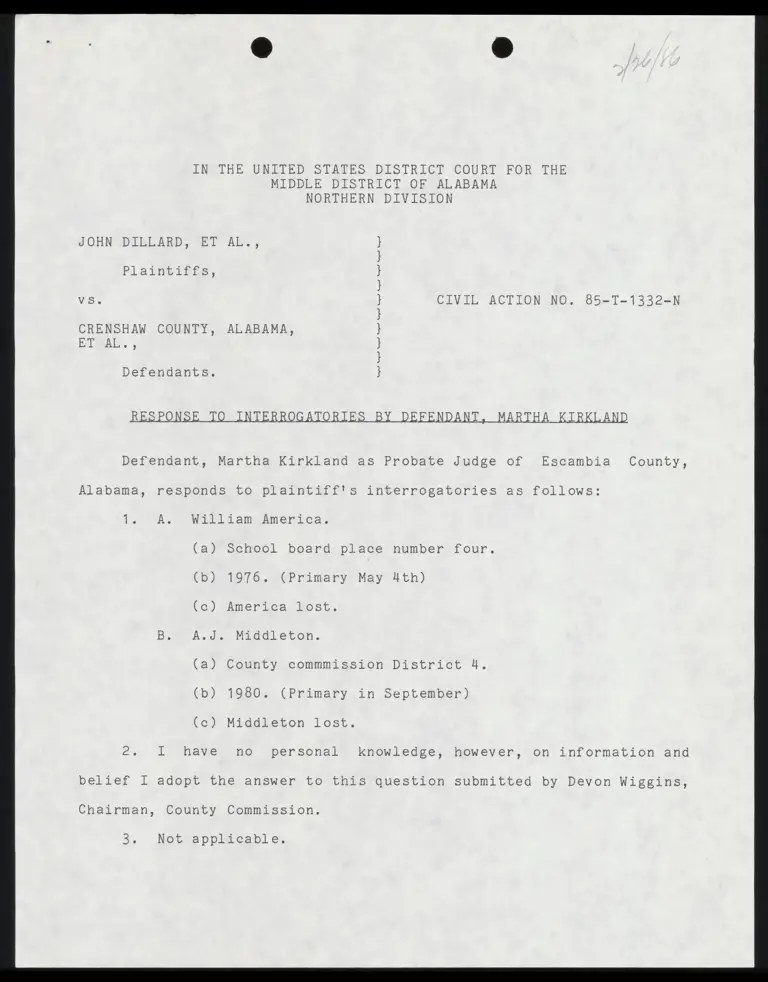

RESPONSE TO INTERROGATORIES BY DEFENDANT, MARTHA KIRKLAND

Defendant, Martha Kirkland as Probate Judge of Escambia County,

Alabama, responds to plaintiff's interrogatories as follows:

1. A. William America.

(a) School board place number four.

(b) 1976. (Primary May 4th)

(c) America lost.

BJ* A.J. Middleton.

(a) County commmission District 4.

(b) 1980. (Primary in September)

(c) Middleton lost.

2. 1 have no personal knowledge, however, on information and

belief I adopt the answer to this question submitted by Devon Wiggins,

Chairman, County Commission.

3. Not applicable.

. 1 have no .personal Knowledge, however, on information and

belief I adopt the answer to this question submitted by Devon Wiggins,

Chairman, County Commission.

5." Yes,

(a) Harris v. Graddick, Civil Action Number 84-T-595,

(b) * Uniged 'Stales District ‘Court, ‘Middle District of

Al abama.

(c) April 31st, 3984,

(d) Class action for appointment of minority citizens as

polls official 5.

6. Not to my knowledge.

T. I have no personal knowledge of ordinances, rules or

regulations of the county commission, however, on information and

belief I adopt the answer to this question submitted by Devon

Wiggins, Chairman of the County Commission.

8. I have no personal knowledge of ordinances, rules or

regulations of the county commission, however, on information and

belief .1 .adopt the . answer to this question submitted by Devon

Wiggins, Chairman of the County Commission.

9. I have no personal knowledge of ordinances, rules or

regulations of the county commission, however, on information and

belief I adopt ‘the answer to this question submitted by Devon

Wiggins, Chairman of the County Commission.

10. I: "have . no’ personal knowledge of ordinances, rules or

regulations of the county commission, however, on information and

belief

Wiggins,

if.

i2.

I

adopt "the answer to “this. ‘question

Chairman of the County Commission.

Not to my knowledge.

A.

rr}

Chairman of the County Commission.

(a) Devon Wiggins, caucasion.

(b) January 17th, 1977 to present.

District one County Commission.

(a) William Cook, caucasion.

(b) January 16th, 1967 to present.

District two County Commission.

(a) James E. Evans, caucasion.

(b) Janaury 15th, 1985 to present.

District three County Commission.

(a) Sammy McGowin, caucasion.

(b) January 16th, 1979 to present.

District four county commission.

(a) Weldon Vickrey, American Indian.

(b) January 15th, 1985 to present.

Probate Judge.

(a) Martha Kirkland, caucasion.

(b) October 1969 to present.

Circuit Clerk.

(a) James Taylor, caucasion.

(b) January 1971 to present.

Sheriff.

submitted by Devon

13.

(a)

(b)

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

(e)

Cf)

(g)

(h)

Timothy Hawsey, caucasion.

January 1983 to present,

Note attached report.

None,

See attached report.

See attached report.

Attached.

ADC Forum Group meetings at Southern Normal ang Paris

Motel 1970 ang 1982. I was introduced ang spoke, I

do not remember who else was there,

McCall's School and Escambia High School. TI paid for

a cake at McCall's School in 1970 and Spoke, + T. do

not remember who else was there,

At Southern Normal I was asked in 1970 about hiring

Practices for blacks.” I promised to give every

Consideration for qualified black applicants.

lI do not remember,

I made an dpbeal to .ali voters.

No campaign staff.

Not applicable,

I do not remember,

I do ‘not remember,

No endorsements that I can recall,

All current reports of campaign expenses are

attached. Prior campaign expense reports are not

retained.

14, Undersigned is Judge of Probate. The campaign reports are recorded in tpe Probate Judge's Office.

15." -nave No personal knowledge, however, on information and belier 1 adopt the answer to the question Submitted by Devon Wiggins, Chairman of the County Commission,

16. I know of no election Characterizeg by racial polarization, 17. Various candidates have Sought and received the ADC backing for many years. I know of no elections in Escambia County that have been Characterizeg by racial bolarization,

18. This depends upon your definition of the "recent past", The School systen to my knowledge in the recent past has been racially integrated,

21.% I have NO personal knowledge, however, on information and belief TI adopt the answer submitted by Devon Wiggins, Chairman of the County Commission,

22. "1 ‘apna member of the First Methodist Church, Escambia County Farm Bureau, Escambia County Cattlemen's Association, Escambia County Association for Retarded Citizens, Escambia County Mental Heal th Association, Escambia County Cancer Society, Southwest Alabama Kidney Auxilliary, Delta Kappa Gamma, ang the University of Montevallo Alumni Association,

23. The county school system is an agency of this State and we do

not maintain this information.

24. The county school system is an agency of this State and we do

not maintain this information.

25. The county school system is an agency of this State and we do

not maintain this information.

26. On information and belief I adopt the answer submitted to

this question by Devon Wiggins, Chairman of the County Commission.

27. I have no personal knowledge of any studies, reports or

proposals regarding changes in the county commission or school board

since 1930. On information and belief I adopt the answer submitted to

this question by Devon Wiggins, Chairman of the County Commission.

28. Attached is "a _ list of all poll officials for the primaries

and elections conducted from 1980 through 1985. The race of each is

marked thereon.

29. Attached is a list of all poll officials for the primaries

and elections conducted from 1980 through 1985. The race of each is

marked thereon.

30. Not known. at this time,

La

MARTHA KIRKLAND

Judge of Probate

ey St arn 1

” Yo 7 4 CT << { D4

Ler Np A Arid

SWORN to and SUBSCRIBED before m his the Lo day of

Cobra, , 1986.

Rete

NOTARY PUBLIC

" JAMES W. WEBB

OF COUNSEL:

Attorney for Martha Kirkland

WEBB, CRUMPTON, McGREGOR, SCHMAELING & WILSON

166 Commerce Street, P.O. Box 238

Montgomery, Alabama 36101

(205) 834-3176

OTTS & MOORE

P.O." Box 467

Brewton, Alabama 36427

(205) 867-7724

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that copies of the foregoing response

to interrogatories by defendant, Martha Kirkland, have been mailed to

Larry T. Menefee, Esquire, James U. Blacksher, Esquire and Wanda J.

Cochran, Esquire, Blacksher, Menefee & Stein, 405 Van Antwerp

Building, P.O, Box 105%, Mobile,’ Alabama 36633, / Terry G. Davis,

Esquire, Seay «&. Davis, 732 Carter Hill Road, P.O. .Box 6125,

Montgomery, Alabama 36106, Deborah Fins, Esquire and Julius L.

Chambers, Esquire, NAACP Legal Defense Fund, 99 Hudson Street, 16th

Floor, New York, New York, 10013, Jack Floyd, Esquire, Floyd, Kenner &

Cusimano, 816 Chestnut Street, Gadsden, Alabama 356999, Alton Turner,

Esquire, Turner & Jones, P.O. Box 207, Luverne, Alabama 36049, D.L.

Martin, Esquire, 215 5S. Main Street, Moulton, Alabama 35650, David R.

Boyd, Esquire, Balch & Bingham, P.O. Box 78, Montgomery, Alabama

36103, . W.0. Kirk, sJr., Esquire, Curry & Kirk, Phoenix Avenue

Carrollton, Alabama 35447, Barry D. Vaughn, Esquire, Proctor & Vaughn,

1217 N. Norton Avenue, Sylacauga, Alabama 35150, H.R. Burnham, Esquire,

Burnham, Klinefelter, Halsey, Jones & Cater, 401 SouthTrust Bank

Building, P.O. Box 1618, Anniston, Alabama 36202, Warren Rowe,

Esquire, Rowe, Rowe & Sawyer, P.O. Box 150, Enterprise, Alabama 36331,

Edward Still, Esquire, 714 South 29th Street, Birmingham, Alabama

35233-2810, Reo Kirkland, Jr., Esquire, P.O. Box 646, Brewton, Alabama

36427, and all defendants not represented by counsel by placing copies

of the same in the United States Mail, postage prepaid this the AL

day of February, 1986, \ i

/ J

{ g / f I'd 7

Janes WW. WebD