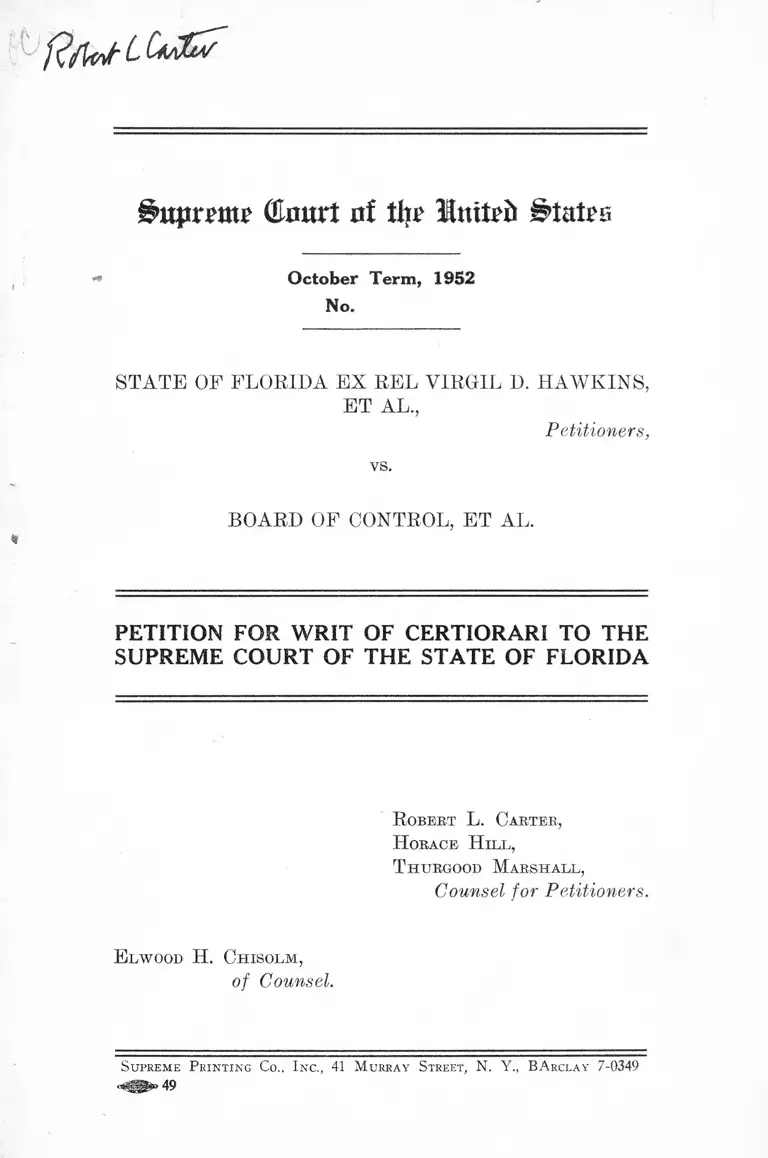

Florida v. Board of Control Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of the State of Florida

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1952

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Florida v. Board of Control Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of the State of Florida, 1952. a0337309-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f9151f6e-e45a-4d3a-95a5-ac987488762f/florida-v-board-of-control-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-the-state-of-florida. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

£§>uttn>mr ( ta r t rtf % luitrfc Stairs

O ctober Term, 1952

No.

STATE OP FLORIDA EX REL VIRGIL I). HAWKINS,

ET AL.,

Petitioners,

vs.

BOARD OF CONTROL, ET AL.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF FLORIDA

Robert L. Carter,

H orace H ill,

T hurgood Marshall,

Counsel for Petitioners.

E lwood H . Chisolm ,

of Counsel.

Supreme F einting Co.. Inc., 41 M urray Street, N. Y., BArclay 7-0349

•W.-3-*- -19

I N D E X

Subject Index

PAGE

Petition for Writ of Certiorari .................................. 1

Opinions Below ........................................................... 1

First Opinion......................................................... 1

Second Opinion ...................................................... 2

Third Opinion ....................................................... 2

Jurisdiction .................................................................. 2

Questions Presented ......................................... 2

Statement ...................................................................... 3

Specification of Error .................................................. 7

Reasons for Allowance of the W rit .............................. 7

Conclusion...................................................................... 9

Table of Cases

McKissiek v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (C. A. 4th

1951) ......................................................................... 8

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637 . . 8, 9

Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 ......... 7

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631.................... 7

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 .................................... 8, 9

Wilson v. Board of Supervisors, 340 U. S. 909 ......... 8

Supreme (tort nf %' Tlhnttb States

October Term, 1952

No.

o-

S tate of F lorida ex rbl V irgil D. H awkins, E t A l .,

vs.

Petitioners,

B oard of Control, E t Al .

---------------- --- o--------------------

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF FLORIDA

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the

United States:

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Florida, entered

in the above-entitled causes on August 1, 1952.

Opinions Below

First Opinion

These cases have now been pending for more than two

years. The first opinions of the Florida Supreme Court

were entered on August 1, 1950. The opinion involving

petitioner Virgil D. Hawkins is reported at 47 So. 2d 608

(R. 25); that involving petitioner Rose Boyd is reported

at 47 So. 2d 619 (R. 25); that involving petitioner Oliver

Maxey is reported at 47 So. 2d 618 (R. 24); and that in

volving petitioner Benjamin Finley is reported at 47 So.

2d 620 (R. 25).

2

Second Opinion

Opinions were again filed by the Florida Supreme Court

on June 15, 1951. The opinion involving petitioner Haw

kins is reported at 53 So. 2d 116 (R. 40); that involving-

petitioner Boyd is reported at 53 So. 2d 120 (R. 28); that

involving petitioner Maxey is reported at 53 So. 2d 119

(R. 27); and that involving petitioner Finley is reported

at 53 So. 2d 119 (R. 28).

Third Opinion

The third and final set of opinions of the Florida

Supreme Court was entered on August 1, 1952. The

opinion involving petitioner Hawkins is reported at 67

So. 2d 162 (R. 47); that involving petitioner Boyd is re

ported at 67 So. 2d 166 (R. 32); that involving petitioner

Maxey is reported at 67 So. 2d 166 (R. 31); and that in

volving petitioner Finley is reported at 67 So. 2d 166

(R. 31).

Jurisdiction

The Supreme Court of Florida, on August 1, 1952,

denied petitioners’ motions for peremptory writs of man

damus, quashed the alternative writs of mandamus hereto

fore issued and dismissed the causes (.Hawkins R. 52;

Boyd R. 32; Maxey R. 31; Finley R. 32). Jurisdiction of

this Court is invoked pursuant to Title 28, United States

Code, Section 1257 (3). At each and every stage of these

proceedings, petitioners have relied upon and pressed their

claims under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Questions Presented

Can the State of Florida refuse to admit petitioners

to the University of Florida for the pursuit of graduate

training in agriculture and chemical engineering, and pro

3

fessional training in law and pharmacy solely because of

their race and color without violating petitioners’ rights to

the equal protection of the laws as guaranteed under the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

Statement

Petitioners Virgil 1). Hawkins, Rose Boyd, Oliver

Maxey and Benjamin Finley brought separate and inde

pendent actions in the court below seeking writs of man

damus ordering their admission to the University of

Florida. Since all four cases involve the same question,

one petition is being filed here.

On April 4, 1949, petitioners made due and timely ap

plication for admission to the University of Florida, a

public institution maintained and operated by the State for

the higher education of its citizenry. Virgil I). Hawkins

applied for admission to the School of Law, Rose Boyd

for admission to the School of Pharmacy, Oliver Maxey

for courses leading to a graduate degree in chemical en

gineering and Benjamin Finley for courses leading to a

graduate degree in agriculture. Petitioners were then and

are now fully qualified in every lawful respect for admis

sion to the University.

Their applications were referred to respondent Board

of Control which governs and operates the university

system maintained by the State. On May 13, 1949, peti

tioners met with the Board of Control and they were

advised that the laws of the State prohibited their admis

sion to the University since it was maintained exclusively

for white persons. The Board offered to pay petitioners’

tuitions to institutions of their choise outside the state

(Hawkins R. 16-17; Finley R. 16; Maxey R. 16; Boyd

R. 16).

4

Petitioners then instituted the instant action by filing-

petitions for alternative writs of mandamus in the Supreme

Court of Florida (R. 1). These petitions were granted

on June 10, 1949 (R. 4). Respondents’ motions to quash

were denied on December 8, 1949 (Hawkins R. 9; Maxey

R. 8, Boyd R. 8-9; Finley R. 8); and on January 7, 1950 they

filed their answers (Hawkins R. 9-24); Maxey R. 8-23;

Boyd R. 9-24; Finley R. 9-24).

Respondents admitted that petitioners were refused

admission to the University of Florida solely because they

are Negroes. They also admitted that at the time of peti

tioners’ applications the University of Florida was the

only state institution offering the desired courses (Haw

kins R, 11; Boyd R. 11; Maxey R. 10; Finley R. 10). Their

answers further alleged that the Board of Control, in a

resolution dated December 21, 1949, had authorized the

establishment of these courses at the Florida A & M Col

lege for Negroes (Hawkins R. 21; Maxey R. 20; Finley

R. 20; Boyd R. 20). The Board Resolution recited that

if these courses were not available at the College when

petitioners made application for admission thereto, and if

the offer of out-of-state aid should be held not to satisfy

the State’s constitutional obligations, petitioners, would

be admitted temporarily to the University on a segregated

basis until such time as the courses in question are pro

vided at the College (Hawkins R. 22-24; Maxey R. 21-23;

Finley R. 22-24; Boyd R. 22-24)}

1 “ * * * tllere js hereby established, at the Florida Agricultural

and Mechanical College for Negroes, schools of law, mechanical

engineering, agriculture at graduate level and pharmacy at graduate

level; and qualifications for admission to said courses shall be the

same as those required for admission to said courses at other State

institutions of higher learning in the State of Florida; and

“ * * * efforts to acquire the necessary personnel, facilities, and

equipment for such courses be reactivated and diligently prosecuted,

with the view of installing said personnel, facilities, and equipment

for such courses at the Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College

5

On January 19, 1950, petitioners filed motions for per

emptory writs of mandamus notwithstanding respondents’

answers (Hawkins 24-25; Finley 24-25; Boyd R. 23-24;

Maxey 24). On August 1, 1950, the court below held these

petitions to be in the nature of demurrers in that they ad-

for Negroes, at Tallahassee, Florida, at the earliest date possible,

thereby to more fully comply with the Constitution and laws of the

State of Florida; and that, in the meantime, and while diligent prep

aration is being made to physically set up said schools and courses at

the Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College for Negroes, at

Tallahassee, Florida, further effort to be made to arrange with said

applicants for out-of-state scholarships or other arrangements agree

able to them, equal to their reasonable individual needs and affording

them full and complete opportunity to obtain the education for which

they have applied, where obtainable, at institutions other than Florida

state operated institutions of learning for white students, and under

circumstances and surroundings fully as good as may be offered at

any State operated institution of higher learning in the State of

Florida; and

“ * * * in the event the court should hold that the foregoing pro

visions are insufficient to satisfy the lawful demands of said applicants,

that temporarily, and only until completion of such acquisition of

personnel, facilities and equipment for installation at the Florida

Agricultural and Mechanical College for Negroes, at Tallahassee,

comparable to those in institutions of higher learning of the State

established for white students, the Florida Agricultural and Mechani

cal College for Negroes shall arrange for supplying said courses to

its enrolled and qualified students at a Florida state operated institu

tion of higher learning, where said courses may be given, and where

the instructional personnel and facilities of such institution in the

requested courses shall be provided and used for the education of said

applicants at such times and places, and in such manner, as the latter

institution may prescribe; and the authorities of such last described

state operated institution of higher learning shall cooperate in making-

such arrangement, to the end that there shall be available to said

students of the Agricultural and Mechanical College for Negroes,

substantially equal opportunity for education in said courses as may

be provided for white students under like circumstances. In provid

ing such education, the authorities of both institutions shall at all times

observe all requirements of the laws of the State of Florida in the

matter of segregation of the races, etc.” (Hawkins, R. 23-24; Maxey,

R. 22-23; Finley, R. 22-24; Boyd, R. 22-23.)

6

mitted the truth of respondents’ allegations of fact and

ruled that the allegations of the Board of Control—(1)

that it had ordered the establishment of schools of law,

pharmacy, graduate agriculture and chemical engineer

ing at Florida A & M College; (2) that it had ordered

“ reactivation” of the necessary effort to secure equip

ment and personnel; and (3) that it offered to temporarily

admit petitioners to the University of Florida on a segre

gated basis until such time as these schools were actually

in operation at the College for Negroes—sufficiently satis

fied the State’s constitutional obligation to furnish equal

educational opportunities (Hmvkins E. 32-38; Finley E. 26 ;

Boyd E. 25; Maxey E. 26). The court refused, however, to

enter a final order and retained jurisdiction of the cases

in order to permit, petitioners or respondents to seek at

some later date whatever further relief might be war

ranted (Hawkins E. 38; Finley E. 26; Boyd E. 26; Maxey

E. 25).

On August 7, 1950, petitioners reapplied to the Univer

sity. On May 16, 1951, not having been admitted to or

enrolled in any institution, petitioners again filed motions

for peremptory writs of mandamus and for further relief in

accordance with the court’s opinions. On June 15, 1951,

these motions were denied (Hawkins E. 40-44; Maxey

E. 27; Boyd E. 28-29; Finley E. 28). Thereupon a peti

tion for writ of certiorari was filed in this Court, and it

was denied for want of final judgment.-----U. S. ------ ,

96 L. ed 65.

Again petitioners applied to the University (Hawkins

E. 45; Boyd E. 31 Maxey E. 29; and Finley E. 30), hut

to date no action has been taken on their applications.

Motions for peremptory writs were filed for a third time

(Hawkins E. 45; Boyd E. 31; Maxey E. 29 and Finley

E. 30). Two years after the initial decision, the court

below, on August 1, 1952, entered final judgments denying

these motions, quashing the alternative writs of man

damus previously issued and dismissing the causes.

7

Specification of Error

The court erred in refusing to grant petitioners’

motions for peremptory writs of mandamus and in refus

ing to order petitioners’ admission to the University of

Florida inasmuch as the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment prohibits a state from making

racial distinctions among graduate and professional

students in its universities.

Reasons for Allowance of the Writ

1. Insofar as the resolution of December 21, 1949

clearly showed that the University of Florida was the only

state institution offering courses of study in law, graduate

agriculture, pharmacy and chemical engineering at the

time of the August 1, 1950 opinion, petitioners were at

that time unquestionably entitled to admission to the Uni

versity. Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337;

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631.

2. The court below, in its final opinion dated August

1, 1952, took “ judicial notice” of the fact that there is

now in actual operation at the Florida A & M College for

Negroes “ a duly established and tax-supported law

school * * # at which are offered law courses similar in

content and quality to those offered at the College of Law

of the University of Florida * # *” (Kata-kins R. 50).

Although no similar statement appears in the opinions

covering the other three cases, the court said that the con

clusions reached as to petitioner Hawkins applied equally

to the other petitioners (Finley R. 31; Maxey R. 31; Boyd

R. 32).

Whether the courses which petitioners seek are now

being offered on a segregated basis is, we submit, beside

the point. Any distinctions based upon race or color at

8

the professional and graduate school level of state uni

versities violate the equal protection clause of the Four

teenth Amendment. Sweatt v. Painter, 339 IT. S. 629;

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637;

Wilson v. Board of Supervisors, 340 U. S. 909; McKissick

v. Carmichael, 187 F 2d 949 (C. A. 4th 1951) ; cert. den.

341 U. S. 951.

In the Sweatt case, the segregated law school had been

in operation for several years; in the Wilson case the

segregated law school had been functioning for at least

five years; and in the McKissick case the law school had

been in continuous operation since 1939. Yet, in all three

decisions the schools were held not to afford equal educa

tional opportunities and the state was required to admit

qualified Negro applicants to the state university.

In the McLtmrin case, appellant had been admitted to

the state university but was required to occupy a special

seat in the classrooms, to eat at a special table in the

cafeteria and to work at a table set apart for his exclusive

use in the library. These restrictions, too, were held to

be a denial of the right to equal educational opportunities,

and the state was required to admit him to the university

subject to the same rules and regulations applicable to all

other students.

Here there wasn’t even a semblance of a segregated

law school, or graduate school, or school of pharmacy when

this litigation began. As late as the original decisions in

these cases, there was but a bare directive by respondent

Board of Control to “ reactivate” and diligently prosecute

efforts to procure necessary equipment, personnel and

facilities to get the desired courses of study functioning

on a segregated basis. This mere declaration was there

held sufficient compliance with the equal protection clause.

Now the court below by judicial notice finds that petitioners

have been provided with equality in fact.

9

We submit that under the decisions of this Court, it is

clear that constitutional equality can only be furnished in

graduate and professional education by the admission of

qualified Negro applicants to state universities on the

same terms and subject to the same conditions applicable

to other students. Sweatt v. Painter, supra; McLaurin

v. Oklahoma State Regents, supra.

Conclusion

W herefore, it is respectfully submitted that this peti

tion should be granted, that the causes should be reversed

and remanded without oral argument, and that respon

dents should be ordered to admit petitioners to the Univer

sity of Florida at once under the same rules and regula

tions applicable to all other students.

R obert L. Carter,

H orace H ill,

T hurgood Marshall,

Counsel for Petitioners.

E lwood H. Chisolm ,

of Counsel.

■