Declaration of Michael M. Daniel in Support of Motion for Tro Against the USA with Certificate of Service and Attached Manuals

Public Court Documents

September 2, 1992

27 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thompson v. Raiford Hardbacks. Declaration of Michael M. Daniel in Support of Motion for Tro Against the USA with Certificate of Service and Attached Manuals, 1992. 87610cfb-5d40-f011-b4cb-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f92f99ae-d961-42a2-b6dc-a833acd600b7/declaration-of-michael-m-daniel-in-support-of-motion-for-tro-against-the-usa-with-certificate-of-service-and-attached-manuals. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

A

{ | JUR T

y ¢

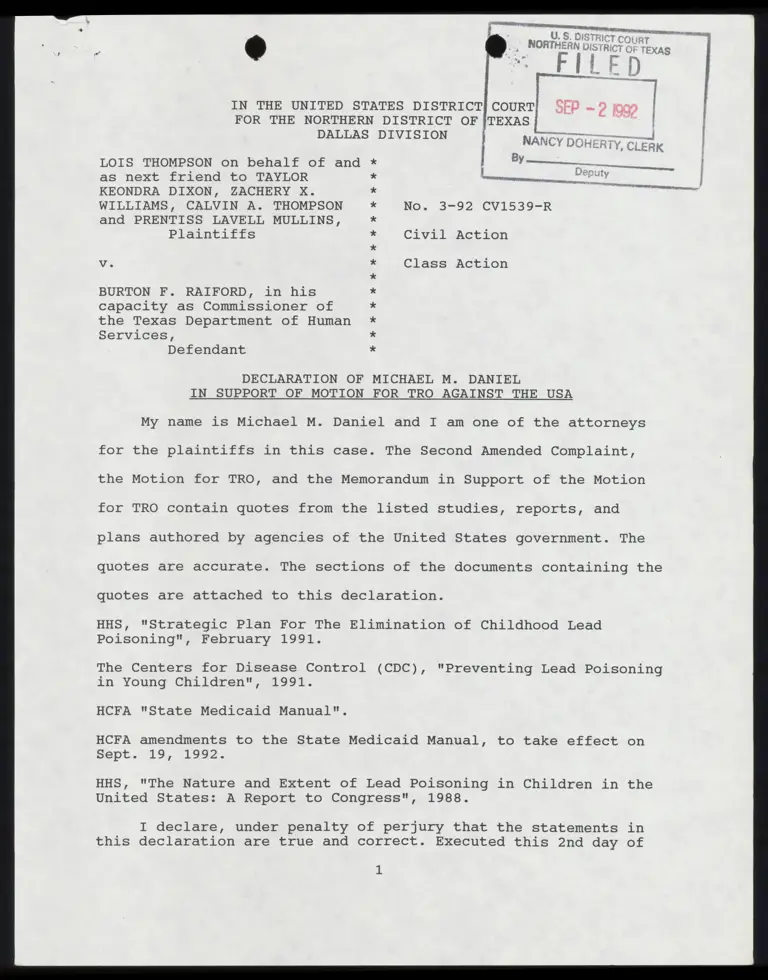

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF

DALLAS DIVISION |

—

NANCY DOHERTY, CLERK

BY

A S——————

D 5 : . y : v a ————

LOIS THOMPSON on behalf of and *

as next friend to TAYLOR

KEONDRA DIXON, ZACHERY X.

WILLIAMS, CALVIN A. THOMPSON

and PRENTISS LAVELL MULLINS,

Plaintiffs

TS.

:

BRS

— J mar

No. 3-92 CV1539-R

Civil Action

Vv. Class Action

BURTON F. RAIFORD, in his

capacity as Commissioner of

the Texas Department of Human

Services,

Defendant ¥

OX

OX

¥

OX

XH

XH

¥

XX

¥

¥

¥

¥*

DECLARATION OF MICHAEL M. DANIEL

IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR TRO AGAINST THE USA

My name is Michael M. Daniel and I am one of the attorneys

for the plaintiffs in this case. The Second Amended Complaint,

the Motion for TRO, and the Memorandum in Support of the Motion

for TRO contain quotes from the listed studies, reports, and

plans authored by agencies of the United States government. The

quotes are accurate. The sections of the documents containing the

quotes are attached to this declaration.

HHS, "Strategic Plan For The Elimination of Childhood Lead

Poisoning", February 1991.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC), "Preventing Lead Poisoning

in Young Children", 1991.

HCFA "State Medicaid Manual".

HCFA amendments to the State Medicaid Manual, to take effect on

Sept. 19, 1992.

HHS, "The Nature and Extent of Lead Poisoning in Children in the

United States: A Report to Congress", 1988.

I declare, under penalty of perjury that the statements in

this declaration are true and correct. Executed this 2nd day of

1

=~ rg »

September, 1992.

WM. \

Michael M. Daniel

Respectfully submitted,

MICHAEL M. DANIEL, P.C.

3301 Elm Street

Dallas, Texas 75226-1637

(214) 939-9230 (telephone)

(214) 939-9229 —-

By: Tho ar OW

Michael M. Daniel

State Bar No. 05360500

By: Xora A. Rapala

Faura B. Beshara

State Bar No. 02261750

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFF

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that a true and correct copy of the above document

was served upon counsel for defendants by FAX and by being placed

in the U.S. Mail, first class postage prepaid, on the 044 day

of Seotemfeh ; 1992.

Ca loo. favfprg

Laura B. Beshara

State Medicaid Manual

Part 5 - Early and Periodic Screening

Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT)

HCFA Pub 45-5

09-92

Rev. 5

Retrieval Title: R5.SM5

REVISED MATERIAL REVISED PAGES REPLACED PAGES

Sec. 5123.2. (Cont .)58-13.~ 5-16.1 (5 pp.) 5-13 - 5-16 (4 pp.)

CHANGED IMPLEMENTING INSTRUCTIONS--EFFECTIVE DATE: 09/19/92

Section 5123.2, Screening Service Content.--Part D of this

section, Appropriate Laboratory Tests, has been revised to update

HCFA policies and provide guidance to States for lead toxicity

screening through the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and

Treatment (EPSDT) program after considering the October 1991

statement of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Public Health

service, Preventing Lead Poisoning in Young Children. The CDC

statement lowered the blood lead level threshold at which followup

and interventions are recommended for children from 25 micrograms

per deciliter (ug/dL) of whole blood to 10 ug/dL.

Given the current state of the art of lead poisoning-related

technology instrumentation and the limitations in resources

available to States for lead poisoning prevention and treatment

efforts, HCFA is issuing this first phase of guidance. In many

States, the public health agency is leading the effort to

implement the new CDC guidelines. HCFA intends to provide enough

flexibility in the screening guidelines to allow State Medicaid

agencies to function within the overall plan of their State health

department.

while HCFA wants to stress that blood lead testing is the

screening test of choice, HCFA acknowledges that it will take some

time for States to make a transition to blood lead testing. The

erythrocyte protoporphyrin (EP) test is not sensitive for blood

lead levels below 25 ug/dL. However, HCFA recognizes that the

capacity may not exist in every community for analyzing blood lead

for every Medicaid eligible child. States continue to have the

option to use the EP test as the initial screening blood test.

However, elevated EP tests must be confirmed with a blood lead

test. Additionally, while HCFA recommends venous blood lead

tests, HCFA understands the hesitation of some practitioners to

perform venous blood tests on small children. In these

circumstances, a capillary specimen may be used for the initial

blood lead test to be followed, if necessary, with a venous blood

lead test. HCFA will consider guidelines for a next phase based

on State or community laboratory testing capacities and any

further revisions to CDC's statement.

A change has been made to Part C, Appropriate Immunizations, by

listing two additional immunizations which should be provided when

medically necessary and appropriate.

:

EARLY AND PERIODIC SCREENING,

09-92 DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT SERVICES 5123.2 (Cont.)

o In screening for developmental assessment, the

examiner incorporates and reviews this information in conjunction

with other information gathered during the physical examination

and makes an objective professional judgement whether the child

is within the expected ranges. Review developmental progress, not

in isolation, but as a component of overall health and well-being,

given the child's age and culture.

o Developmental assessment should be culturally

sensitive and valid. Do not dismiss or excuse improperly

potential problems on grounds of culturally appropriate behavior.

Do not initiate referrals improperly for factors associated with

cultural heritage.

o Programs should not result in..a label or

premature diagnosis of a child. Providers should report only that

a condition was referred or that a type of diagnostic or treatment

service is needed. Results of initial screening should not be

accepted as conclusions and do not represent a diagnosis.

o Refer to appropriate child development resources

for additional assessment, diagnosis, treatment or follow-up when

concerns or questions remain after the screening process.

2. Assessment of Nutritional Status.--This is accomplished

in the basic examination through:

o Questions about dietary practices to identify unusual

eating habits (such as pica or extended use of bottle feedings)

or diets which are deficient or excessive in one or more

nutrients.

o A complete physical examination including an oral

dental examination. Pay special attention to such general features

as pallor, apathy and irritability.

o Accurate measurements of height and weight are among

the most important indices of nutritional status.

o A laboratory test to screen for iron deficiency.

HCFA and PHS recommend that the erythrocyte protoporphyrin (EP)

test be utilized when possible for children ages 1-5. It is a

simple, cost effective tool for screening for iron deficiency.

Where the EP test is not available, use hemoglobin concentration

or hematocrit.

lo) If feasible, screen children over 1 year of age for

serum cholesterol determination, especially those with a family

history of heart disease and/or hypertension and stroke.

If information suggests dietary inadequacy, obesity or other

nutritional problems, further assessment is indicated, including:

o Family, socioeconomic or any community factors,

EARLY AND PERIODIC SCREENING,

5123.2 (Cont.) DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT SERVICES 09-92

o Determining quality and quantity of individual diets

(e.g., dietary intake, food acceptance, meal patterns, methods of

food preparation and preservation, and utilization of food

assistance programs),

o Further physical and laboratory examinations, and

o Preventive, treatment and follow-up services,

including dietary counseling and nutrition education.

B. Comprehensive Unclothed Physical Examination: --This

includes the following:

1. Physical Growth.--Record and compare the child's height

and weight with those considered normal for that age. (In the

first year of life, head circumference measurements are

important). Use a graphic recording sheet to chart height and

weight over time.

2. Unclothed Physical Inspection.--Check the general

appearance of the child to determine overall health status. This

process can pick up obvious physical defects, including orthopedic

disorders, hernia, skin disease, and genital abnormalities.

Physical inspection includes an examination of all organ systems

such as pulmonary, cardiac, and gastrointestinal.

C. Appropriate Immunizations.--Assess whether the child has

been immunized against diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, polio,

measles, rubella, mumps, Haemophilus b Conjugate (HIB) and

hepatitis B and whether booster shots are needed. The child's

immunization record should be available to the provider. When an

immunization or an updating is medically necessary and

appropriate, provide it and so inform the «child's health

supervision provider.

Provide immunizations as recommended by the American Academy of

Pediatrics (AAP) and/or local health departments.

D. Appropriate Laboratory Tests .--Identify, as statewide

screening requirements, the minimum laboratory tests or analyses

to be performed by medical providers for particular age or

population groups. Physicians providing screening/assessment

services under the EPSDT program use their medical judgement in

determining the applicability of the laboratory tests or analyses

to be performed. If any laboratory tests or analyses are medically

contraindicated at the time of screening/assessment, provide them

when no longer medically contraindicated. As appropriate, conduct

the following laboratory tests:

1. Lead Toxicity Screening.--All children ages 6 months to

72 months are considered at risk and must be screened for lead

poisoning. Complete lead screening consists of both a verbal risk

assessment and blood test(s). Each State establishes its own

periodicity schedule after consultation with medical organizations

involved in child health. These periodicity schedules and any

other associated office visits must be used as an opportunity for

anticipatory guidance and risk assessment for lead poisoning. As

part of the nutritional assessment conducted at each periodic

screening, an EP blood test may be done to test for iron

deficiency. This blood test may also be used as the initial

screening blood test for lead toxicity.

a. Risk Assessment. All children from 6 to 72 months

of age are considered at risk and must be screened, unless it can

be shown that the community in which the children live does not

have a childhood lead poisoning problem. Only an official State

or local health authority can declare that a

5-14

Rev. 5

EARLY AND PERIODIC SCREENING,

09-92 DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT SERVICES 5123.2

{Cont .)

geographic community, or part of a community, does not have a

problem. However, all children moving into ‘a "lead-free

community" must be screened. Regardless of their risk, all

families must be given detailed lead poisoning prevention

counselling as part of the anticipatory guidance during the

screening visit.

Beginning at six months of age and at each visit thereafter, the

provider must discuss with the child's parent or guardian

childhood lead poisoning interventions and assess the child's risk

for exposure. Ask the following types of questions at a minimum.

o Does your child live in or regularly visit an old house

built before 19607? was your child's day care

center/preschool/babysitter’'s home built before 1960? Does the

house have peeling or chipping paint?

o Does your child live in a house built before 1960 with

recent, ongoing or planned renovation or remodeling?

o Have any of your children or their playmates had lead

poisoning?

o Does your child frequently come in contact with an adult

who works with lead? Examples are construction, welding, pottery,

or other trades practiced in your community.

o Does your child live near a lead smelter, battery recycling

plant, or other industry likely to release lead such as (give

examples in your community)?

o Do you give your child any home or folk remedies which may

contain lead?

o Does your child live near a heavily travelled major highway

where soil and dust may be contaminated with lead?

o Does your home's plumbing have lead pipes or copper with

lead solder joints?

Ask any additional questions that may be specific to situations

which exist in a particular community.

b. Determining Risk.--Risk is determined from. the

response to the questions which your State requires for verbal

risk assessment.

o If the answers to all questions are negative, a child is

considered low risk for high doses of lead exposure, but must

~

I~

receive blood lead screening by EP or blood lead test at 12 months

of age.

lo) If the answer to any question is positive, a child is

considered high risk for high doses of lead exposure. A blood

lead test must be obtained at the time a child is determined to

be high risk.

Subsequent verbal risk assessments can change a child's risk

category. Any information suggesting increased lead exposure for

previously low risk children must be followed up with a blood lead

test.

Rev. 5

5-15

EARLY AND PERIODIC SCREENING,

5123.2 (Cont.) DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT SERVICES 09-92

Cc. Screening Blood Tests.--The term screening blood

tests refers to blood tests for children who have not previously

been tested for lead with either the EP or blood lead test or who

have been previously tested and found not to have an elevated EP

or blood lead level. If a child is determined by the verbal risk

assessment to be at:

(1) Low Risk.--A screening EP test or a blood lead

test is required at 12 months and a second EP test or a blood lead

test at 24 months.

(2) High Risk.--A blood lead test is required when

a child is identified as being high risk, beginning at six months

of age. If the initial blood lead test results are less than (<)

10 micrograms per deciliter (ug/dL), a screening EP test or blood

lead test is required at every visit prescribed in your EPSDT

periodicity schedule through 72 months of age.

If a child between the ages of 24 months and 72 months has not

received a screening blood test, then that child must receive it

immediately, regardless of being determined at low or high risk.

An elevated EP test must be confirmed with a blood lead test. A

blood lead test result equal to or greater than (>) 10 ug/dL

obtained by capillary specimen (fingerstick) must be confirmed

using a venous blood sample.

d. Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-up.--If a child is

found to have blood lead levels equal to or >10 ug/dL, providers

are to use their professional judgment, with reference to CDC

guidelines covering patient management and treatment, including

follow up blood tests and initiating investigations to the source

of lead, where indicated. Determining the source of lead may be

reimbursable by Medicaid.

e. Coordination With Other Agencies. Coordination with

WIC, Head Start, and other private and public resources enables

elimination of duplicate testing and ensure comprehensive

diagnosis and treatment. Also, public health agencies' Childhood

Lead Poisoning Prevention Programs may be available. These

agencies may have the authority and ability to investigate a lead-

poisoned child's environment and to require remediation.

2. Anemia Test.--The most easily administered test for

anemia is a microhematocrit determination from venous blood or a

fingerstick.

3. Sickle Cell Test.--Diagnosis for sickle cell trait may

be done with sickle cell preparation or a hemoglobin solubility

test. If a child has been properly tested once for sickle cell

EARLY AND PERIODIC SCREENING,

09-92 DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT SERVICES 5123.2

{Cont )

(or guardians) and children is required and is designed to assist

in understanding what to expect in terms of ‘the “child's

development and to provide information about the benefits of

healthy lifestyles and practices as well as accident and disease

prevention.

F. Vision and Hearing Screens.--Vision and hearing services

are subject to their own periodicity schedules (as described in

§5140) . However, where the periodicity schedules coincide with

the schedule for screening services (defined in §5122A), you may

include vision and hearing screens as a part of the required

minimum screening services.

1. Appropriate Vision Screen.--Administer an age-

appropriate vision assessment. Consultation by ophthalmologists

and optometrists can help determine the type of procedures to use

and the criteria for determining when a child is referred for

diagnostic examination.

2. Appropriate Hearing Screen.--Administer an age-

appropriate hearing assessment. Obtain consultation and suitable

procedures for screening and methods of administering them from

audiologists, or from State health or education departments.

G. Dental Screening Services.--Although an oral screening may

be part of a physical examination, it does not substitute for

examination through direct referral to a dentist. A direct dental

referral is required for every child in accordance with your

periodicity schedule and at other intervals as medically

necessary. Prior to enactment of OBRA 1989, HCFA in consultation

with the American Dental Association, the American Academy of

Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Practice, among

other organizations, required direct referral to a dentist

beginning at age 3 or at an earlier age if determined medically

necessary. The law as amended by OBRA 1989 requires that dental

services (including initial direct referral to a dentist) conform

to your periodicity schedule which must be established after

consultation with recognized dental organizations involved in

child health care.

Especially in older children, the periodicity schedule for dental

examinations is not governed by the schedule for medical

examinations. Dental examinations of older children should occur

with greater frequency than is the case with physical

examinations. The referral must be for an encounter with a

dentist, or a professional dental hygienist under the supervision

of a dentist, for diagnosis and treatment. However, where any

screening, even as early as the neonatal examination, indicates

that dental services are needed at an earlier age, provide the

needed dental services.

The requirement of a direct referral to a dentist can be met in

settings other than a dentist's office. The necessary element is

that the child be examined by a dentist or other dental

professional under the supervision of a dentist. In an area where

dentists are scarce or not easy to reach, dental examinations in

a clinic or group setting may make the service more appealing to

recipients while meeting the dental periodicity schedule. 1£

continuing care providers have dentists on their staff, the direct

referral to a dentist requirement is met. Dental

paraprofessionals under direct supervision of a dentist may

perform routine services when in compliance with State practice

acts.

Determine whether the screening provider or the agency does the

direct referral to a dentist. You are ultimately responsible for

assuring that the direct referral is made and that the child gets

to the dentist's office in a timely manner. ;

Developed for the Risk Management Subcommittee, Committee

to Coordinate Environmental Health and Related Programs,

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

February 1991

= U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH

3 AND HUMAN SERVICES

1 Public Health Service

%,

Centers for Disease Control

ayg1a

water, food, and air would help reduce the prevalence of lead poisoning and would help

protect children with blood lead levels below the current definition of lead poisoning

from adverse effects.

The role of exposure to soil lead, both directly and through the contribution of soil lead

to lead in housedust, is still being investigated. The nature and degree of soil lead

abatement that would be appropriate is unclear. The research needed to resolve the soil

lead issues will take years. However, since so many children are being poisoned by

lead-based paint, significant action on lead-based paint abatement should not be delayed

while we await the results of research. Decisions on how to set up rational soil lead

abatement programs will have to be made separately as more data become available.

(However, it is critical not to further contaminate the soil during lead-based paint

abatement efforts.)

We have made substantial progress in reducing exposure to lead; deaths and severe

illness from lead poisoning (e.g., encephalopathy) are now rare. The results of recent

studies indicate, however, that blood lead levels previously believed to be safe are

adversely affecting the health of children. Millions of children in the United States are

believed to have blood lead levels high enough to affect intelligence and development.

The need to deal with preventing exposure at these lower levels will require increased

efforts. The Administration is responding to this problem with increased resources. In

FY 1992, the President’s budget calls for $14.95 million for the lead poisoning prevention

program at the Centers for Disease Control and $25 million for the new HOME

abatement program of the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

In many ways, the tone of this report is one of understatement. The enormity of the task

of eliminating childhood lead poisoning and the extensive public health benefits to be

gained are very clear. This strategic plan is at best a first step. More detailed plans for

implementation must follow, and then the work itself must be done.

Childhood lead poisoning has already affected millions of children, and it could affect

millions more. Its impact on children is real, however silently it damages their brains

and limits their abilities. Deciding to develop a strategic plan for the elimination of

childhood lead poisoning is a bold step, and achieving the goal would be a great

advance.

iii

STRATEGIC PLAN FOR THE

ELIMINATION OF CHILDHOOD LEAD POISONING

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The U.S. Public Health Service Year 1990 and Year 2000 Objectives for the Nation aim

for progressive declines in the numbers of lead-poisoned children in the United States,

leading to the elimination of this disease. We believe that a concerted society-wide

effort could virtually eliminate this disease as a public health problem in 20 years.

This plan, developed for the Committee to Coordinate Environmental Health and

Related Programs of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, provides an

agenda for the first 5 years of a comprehensive society-wide effort to eliminate childhood

lead poisoning. The results and experience from this 5-year program will lead to the

agenda for the following 15 years.

Lead is a poison that affects virtually every system of the body. Results of recent studies

have shown that lead’s adverse effects on the fetus and child occur at blood lead levels

previously thought to be safe; in fact, if there is a threshold for the adverse effects of

lead on the young, it may be close to zero.

Lead poisoning remains the most common and societally devastating environmental

disease of young children. Enormous strides have been made in the past 5 to 10 years

that have increased our understanding of the damaging, long-term effects of lead on

children’s intelligence and behavior. Today in the United States, millions of children

from all geographic areas and socioeconomic strata have lead levels high enough to

cause adverse health effects. Poor, minority children in the inner cities, who are already

disadvantaged by inadequate nutrition and other factors, are particularly vulnerable to

this disease.

Childhood lead exposure costs the United States billions of dollars from medical and

special education costs for poisoned children, decreased future earnings, and mortality of

newborns from intrauterine exposure to lead. Childhood lead poisoning continues in our

society primarily because of lead exposure in the home environment, with lead-based

paint being the principal high-dose source. It is the most important source for the

highest-risk children (e.g., those with blood lead levels > 25 ug/dL); preventive actions

for such exposures should receive the highest priority.

X1

The CDC Categorical Grant Program was authorized by the Lead Contamination

Control Act of 1988. This program provides for childhood lead screening by State and

local agencies, referral of children with elevated blood lead levels for treatment and

environmental interventions, and education about childhood lead poisoning prevention.

Money for this program was first appropriated in FY 1990. The President’s budget for

FY 1992 contains $14.95 million for this program, an increase of $7.16 million from FY

1991.

Other government-funded child health programs also conduct some childhood lead

screening. These programs include Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic,

and Treatment Program (EPSDT); the Supplemental Food Program for Women, Infants,

and Children (WIC); and Head Start.

EPSDT is a comprehensive prevention and treatment program available to

Medicaid-eligible persons under 21 years of age. In 1989, of the 10 million eligible

persons, more than 4 million received initial or periodic screening health examinations.

These are provided at a variety of sites (for example, physician offices, public health

clinics, and community health centers) by private or public sector providers. Screening

services, defined by statute, must include a blood lead assessment "where age and risk

factors indicate it is medically appropriate." (The requirements for a blood lead

assessment are not further defined.) In addition, the EP test is recommended for

children ages 1 to 5 years to screen for iron deficiency. Because this test is also useful in

identifying children with blood lead levels > 25 ug/dL, many children being screened for

iron deficiency are screened for lead poisoning at the same time. The guidelines for

States indicate that environmental investigations for lead-poisoned children are covered

under EPSDT, although abatement is not. However, specific criteria for screening and

the determination of what Medicaid will cover are decided on a State-by-State basis.

Thus, many States do not conduct much screening or do not pay for environmental

investigations for poisoned children. National data are not available on the numbers of

children screened for lead poisoning through EPSDT, since State-reported Medicaid

performance and fiscal data are not broken down to such specific elements.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s WIC program serves pregnant and postpartum

women and children under 5 years of age in low-income households. Program benefits

include supplemental food, nutrition education, and encouragement and coordination for

the use of other existing health services. As of March 1988, an estimated 1.63 million

children ages 1 to 4 years were participating in WIC. Although children must undergo a

medical or nutritional assessment or both to be certified to receive benefits, Federal

WIC regulations permit States to establish their own requirements for WIC certification

examinations. These regulations permit the use of an EP test for certification and define

lead poisoning as a nutritionally-related medical condition that can be the basis of

certifying a child to receive WIC benefits. Most WIC programs that perform EP tests

use them to screen for iron deficiency, although hematocrit or hemoglobin measurements

are most commonly used for this purpose. The nutritional education and supplemental

food provided by WIC are undoubtedly important in reducing lead absorption in many

children and pregnant women.

Page 18

The expansion of screening programs will result in a demand for training programs on

childhood lead screening and the investigation of environmental sources. The Louisville,

Kentucky, training program can serve as a model for other such programs. This program

provides methods for assessing lead poisoning in high-risk populations and demonstrates

the integration of lead screening with basic child health services and the technical and

management skills needed for an effective and efficient childhood lead poisoning

prevention program.

In addition, increased screening will lead to a demand for increased laboratory services.

In 1991 CDC will likely issue new recommendations suggesting that screening programs

attempt to identify children with blood lead levels below 25 ug/dL. This change will

mean that blood lead measurements must be used for childhood lead screening instead

of EP measurements. When this happens, the demand for increased blood lead testing

will far exceed current capacity. In addition, cheaper, easier to use, and portable

instrumentation for blood lead testing will need to be developed. Furthermore, existing

programs for proficiency testing and certification of laboratories will have to be

expanded. With concen about health effects at low blood lead levels, laboratories will

be called upon to do better measurements in the 4 to 5 ug/dL range. As a result, major

efforts will be needed to improve laboratory quality assurance and control at these lower

levels. Reference materials for laboratories performing blood lead measurements and

technical assistance will be required to improve laboratory quality.

Page 23

Studies should be conducted on the cost-effectiveness of different strategies for

childhood lead screening. These strategies include screening in inner-city emergency

rooms to reach children who have no ongoing source of care and "cluster testing” of all

children in multiple dwelling units where cases of childhood lead poisoning have been

identified. The usefulness of screening in day care centers and nursery schools should

also be evaluated. In addition, Federal programs now funding childhood lead screening

should be evaluated to see how they can work together for a most efficient use of

resources.

At present it is much cheaper and easier to perform an EP test than a blood lead

measurement; however, the EP test is not a useful screening test for blood lead levels

below 25 ug/dL. Both because of the expected increase in screening and because of the

concern about the health effects of lower blood lead levels, the demand for blood lead

testing is likely to increase. The development of portable, easy-to-use, cheaper

instrumentation for blood lead measurement is extremely important.

Because capillary (or fingerstick) blood samples may be easily contaminated with lead on

the skin, venous blood must be used to confirm lead poisoning in children. Several

capillary blood collection devices now on the market purport to collect blood free of

surface finger contamination from lead. These devices should be evaluated for ease of

use and ability to collect an uncontaminated sample.

The education of families about lead poisoning by childhood lead poisoning prevention

programs often includes information about the importance of nutrition. Because of our

growing concern about the adverse effects of low blood lead levels, nutritional

interventions are likely to be recommended for more children. A number of nutritional

factors have been shown experimentally to influence the absorption of lead and its

concentrations in tissues. Intervention studies or clinical trials should be conducted to

establish that increasing the regularity of meals and ensuring adequate dietary intake of

iron and calcium can reduce blood lead levels.

Educational strategies for increasing medical care provider and public awareness of lead

poisoning should also be evaluated for their efficacy in reducing children’s blood lead

levels and preventing lead poisoning.

Page 40

i ! VI,

+" 1

{

{

i

( A STATEMENT BY THE CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL — OCTOBER 1991

oR tyvqya

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES / Public Health Service / Centers for Disease Control

RN)

<x

0)

=

~

-'

<

wd

*

°

No

.

51

13

PLAINTIFF'S

EXHIBIT 2

§ CA3-85-,2/0-0

2 WALKER v. NUD

Large numbers of children continue to have blood lead levels high enough to cause

adverse effects.

:

Substantial progress has been made, however, in reducing blood lead levels in the

United States.

Lead-based paint remains the major source of high-dose lead poisoning in the United

States.

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry estimated that in 1984, 17% of all

American preschool children had blood lead levels that exceed 15 pg/dL (ATSDR, 1988).

Although all children are at risk for lead toxicity, poor and minority children are dispropor-

tionately affected. Lead exposure is at once a by-product of poverty and a contributor to the

cycle that perpetuates and deepens the state of being poor.

Substantial progress has been made in reducing blood lead levels in U.S. children. Perhaps

the most important advance has been the virtual elimination of lead from gasoline. Close

correlations have been demonstrated between the decline in the use of leaded gasoline and

declines in the blood lead levels of children and adults between 1976 and 1980 (Annest, 1983)

(Figure 2-5). Levels of lead in food have also declined significantly, as a result both of the

decreased use of lead solder in cans and the decreasing air lead levels.

Lead-based paint remains the major source of high-dose lead poisoning in the United States.

Although the Consumer Products Safety Commission (CPSC) limited the lead content of new

residential paint starting in 1978, millions of houses still contain old leaded paint. The

Department of Housing and Urban Development estimates that about 3.8 million homes with

young children living in them have either nonintact lead-based paint or high levels of lead in

dust (HUD, 1990).

Figure 2-5. Change in blood lead levels in relation to a decline in use of leaded

gasoline, 1976-1980

110

|

: : 16

100 - Lead used in gasoline

Zz

15

ud

- 14

80 { Average blood

lead levels

ro

(1

p/

3r

1)

sp

aa

1

pe

a

po

or

He

sm

y

To

ta

l

Le

ad

Us

ed

Pe

r

6

M

o

n

t

h

Pe

ri

od

(1

00

0

To

ns

)

70 A

60 -

11

50 1 ;

.

- 10

> : I

T T T T T Ir ;

T1976 1977 1978 1979 1980

Year

Source: Annest JL, 1983.

12

f' SCREENING METHOD

Screening should be done using a blood lead test.

Since erythrocyte protoporphyrin (EP) is not sensitive enough to identify more than a small

percentage of children with blood lead levels between 10 and 25 pg/dL. and misses many

children with blood lead levels =25 pg/dL (McElvaine et al., 1991), measurement of blood lead

levels should replace the EP test as the primary screening method. Unless contamination of

capillary blood samples can be prevented, lead levels should be measured on venous samples.

Obtaining capillary specimens is more feasible at many screening sites. Contamination of

capillary specimens obtained by finger prick can be minimized if trained personnel follow

proper technique (see Appendix I for a capillary sampling protocol). Elevated blood lead results

obtained on capillary specimens should be considered presumptive and must be confirmed using

venous blood. At the present time, not all laboratories will measure lead levels on capillary

specimens.

Programs will need to increase their capacity to perform blood lead testing. During the

transition to the use of the blood lead test as the primary screening method, some programs will

temporarily continue to use EP as a screening test. In addition, some nutrition programs (for

example, the Supplemental Food Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC)) use the EP

test to identify children with iron deficiency.

For a discussion of the units used to report EP results (Page 48). All EP test results of =35

pg/dL if standardized using 241 L cm-1 mmol-1, >28 pg/dL if standardized using 297 L cm-1

mmol-1, or =70 pmol 7nPP/mol heme, if the hematofluorometer reports in these units, must be

followed by a blood lead test (preferably venous) and an evaluation for iron deficiency (Page 53).

Work on developing easy-to-use, cheap, portable instruments for blood lead testing is ongoing.

ANTICIPATORY GUIDANCE AND ASSESSING RISK

Anticipatory guidance helps prevent lead poisoning by educating parents on ways to

reduce lead exposure.

Questions about housing and other factors are used to identify which children are at

greatest risk for high-dose lead exposure.

Anticipatory guidance and assessment of risk should be tailored to important sources

and pathways of lead exposure in the child’s community.

4

Guidance on childhood lead poisoning prevention and assessment of the risk of lead poisoning

should be part of routine pediatric care. Anticipatory guidance is discussed in more detail in

Chapter 4. The guidance and risk assessment should emphasize the sources and exposures that

are of greatest concern in the child’s community (Chapter 3). Because lead-based paint has been

used in housing throughout the United States, in most communities it will be necessary to focus

on this source.

41

® - ®

( state medicaid manual Fi in

Part 5 — Early and Periodic Screening, oie fun

Diagnosis, and Treatment

Transmittal No. 4

Date JULY 1990

REVISED MATERIAL REVISED PAGES REPLACED PAGES

Table of Contents

Part 5 5-1 (1 p.) 5-1 (1 p.) Sec. 5123.2 (Cont.) 5-15-5-16(2pp.) 5-15-5-16(2pp.) Sec. 5140 : 5-19 - 5-20(2 pp.) 5-19 - 5-20(2 pp.) Sec. 5320.2 (Cont.) 5-39-5-40 (2 pp.) 5-39-5-40 (2 pp.) Sec. 5350-5360 9-55-5-58 (4 pp.) 5-55 (1 p.)

CORRECTION—EFFECTIVE DATE: April 1, 1990

Section 5§123.2.D.1, Lead Toxicity Screening, is clarified to define lead poisoning and recommended testing.

;

Section 5140, Periodicity Schedule, issued in Transmittal 3, April 1890, incorrectly included a sentence which was inappropriate and misleading in the second paragraph ( under §5140.

NEW PROCEDURE—EFFECTIVE DATE: JULY-1,-1990 Ere ELA

___Sectioh 5320.2.D., Records or Information on Services and Recipients-Program ~~" Reports, is revised to briefly describe the content of the annual report (HCFA-416) which replaces the Quarterly report on the EPSDT program (HCFA-420),

Section 5360, Annual Participation Goals, describes the methods for setting annual and State-specific participation goals for early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment services as required by §1905(r) of the Act, amended by §6403(c) of OBRA 89.

HCFA-Pub. 45-5

|

EARLY AND PERIODIC SCREENING,

07-90 DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT SERVICES, 5123.2(Cont.)

Screen all Medicaid eligible children ages 1-5 for lead poisoning. Lead poisoning is

defined as an elevated venous blood lead level (i.e., greater than or equal to 25

micrograms per deciliter (ug/dl) with an elevated erythrocyte protoporphyrin (EP) level

(greater than or equal to 35 ug/dl of whole blood). In general, use the EP test as the

primary screening test. Perform venous blood lead measurements on children with

elevated EP levels.

Children with lead poisoning require diagnosis and treatment which includes periodic re-

evaluation and environmental evaluation to identify the sources of lead.

2. Anemia Test.—The most easily administered test for anemia is a

microhematocrit determination from venous blood or a fingerstick.

3. Sickle Cell Test.--Diagnosis for sickle cell trait may be done with sickle cell

preparation or a hemoglobin solubility test. If a child has been properly tested once for

sickle cell disease, the test need not be repeated.

4. Tuberculin Test.—Give a tuberculin test to every child who has not received

one within a year. ,

5. Others.—In addition to" the tests above, there are several other tests to

consider, Their appropriateness are determined by an individual's age, sex, health

history, clinical symptoms and exposure to disease. These include a urine screening,

pinworm slide, urine culture (for girls), serological test, drug dependency screening, stool

specimen for parasites, ova,blood, and HIV screening.

E. Health Education.—Health education is a required component of screening

services and includes anticipatory guidance. At the outset, the physical and dental

assessment, or screening, gives you the initial context for providing health education.

Health education and counselling to both parents (or guardians) and children is required

and is designed to assist in understanding what to expect in terms of the child's

development and to provide information about the benefits of healthy lifestyles and

practices as well as accident and disease prevention.

F. Vision and Hearing Screens.—Vision and hearing services are subject to their own

periodicity schedules (as described in §5140). However, where the periodicity schedules

coincide with the schedule for screening services (defined in §5122 A), you may include

vision and hearing screens as a part of the required minimum screening services.

1. Appropriate Vision Screen.—Administer an age-appropriate vision

assessment. Consultation by opthalmologists and optometrists can help determine the

type of procedures to use and the criteria for determining when a child should be referred

for diagnostic examination, :

: 2. Appropriate Hearing Screen.—Administer an age-appropriate hearing

assessment. Obtain consultation and suitable procedures for screening and methods of

administering them from audiologists, or from State health or education departments.

Rev. 4&4 i 5-15

The Nature and Extent of

Lead Poisoning 1 | g in Chi

In the United States: Lelrg

A Report to Congress

on G4 Ean

AR bg fs

Ah) A ALS As,

PLAINTIFF

EXHIBIT Be

(A3- s—]& 107

cer. v NUD

Bl

um

be

rg

No

.

51

13

AR aay

oy oS i tpt

i E wiasd

gh

SRE RE See

\

A

wl

bi

yet be routinely employed in screening programs. The kinetic, toxicological, and practical aspects of biological monitoring and other approaches to assess- ing lead exposure have been extensively discussed by U.S. EPA (1986a).

In young children, effects monitoring for lead exposure is primarily based on lead's impact on the heme biosynthetic pathway, as shown by (1) changes in the activity of key enzymes delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALA-D) and delta-aminolevulinic acid synthetase (ALA-S), (2) the accumulation of copropor- phyrin in urine (CP-U), and (3) the accumulation of protoporphyrin in erythro- cytes (EP). For methodological and practical reasons, the EP measure is the effect index most often used in screening children and other population groups.

Effects monitoring for exposure in general and lead exposure in particular has drawbacks (Friberg, 1985). Effects monitoring is most useful when the endpoint being measured is specific to lead and sensitive to Tow levels of lead. Since EP levels can be elevated by iron deficiency,

young children

the other.

which is common in

, indexing one relationship requires quantitatively adjusting for

An elevated Pb-B level and, consequently, increased lead absorption may exist even when the EP value is within normal limits, now £35 micrograms (ug) EP/deciliter (d1) of whole blood. We might expect that in high-risk, low socioeconomic status (SES),

urban areas,

nutrient (including iron)-deficient children in

chronic Pb-B elevation would invariably accompany persistent EP

Analysis of data from the second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES II) by Mahaffey and Annest (1986) indicates that Pb-B levels in children can be elevated even when EP levels are normal. Of 118 children with Pb-B levels above 30 pg/dl (the CDC criterion level at the time of NHANES II), 47% had EP levels at or below 30 Mg/dl, and 58% (Annest and Mahaffey, 1984) had EP levels less than the current EP cutoff value of 35 ug/dl (cbc, 1985). This means that reliance on EP level for ini

can result in a significant incidence of false ne

toxic Pb-B levels.

elevation.

tial screening

gatives or failures to detect

This finding has important implications for the interpreta- tion of screening data, as discussed in Chapter V.

3. Environmental Sources of Lead in the United States with Reference to

Young Children and Other Risk Groups

As graphically depicted in Figure II-1, several environmental sources of lead exposure pose a risk for young children and fetuses. Many sources not

I1-9