Letter from Higgins to All Counsel RE: Copy of Court’s Opinion and Judgment

Public Court Documents

June 12, 1973

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Letter from Higgins to All Counsel RE: Copy of Court’s Opinion and Judgment, 1973. 38f92826-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f9748077-e807-4fb0-8f47-d1743e32b0dc/letter-from-higgins-to-all-counsel-re-copy-of-court-s-opinion-and-judgment. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

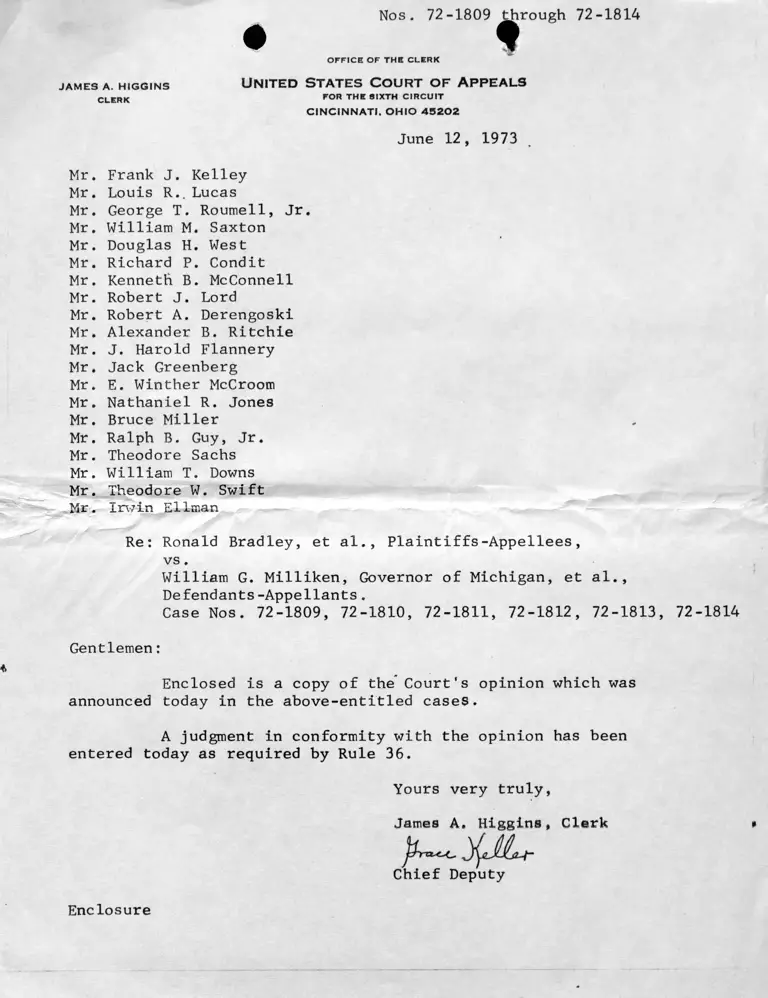

Nos. 72-1809 through 72-1814t

O F F I C E O F T H E C L E R K

J A M E S A. H I G G I N S

C L E R K

U n ite d St a t e s C o u r t o f A p p e a ls

F O R T H E S I X T H C I R C U I T

C I N C I N N A T I . O H I O 4 3 2 0 2

June 12, 1973

Mr. Frank J. Kelley

Mr. Louis R.. Lucas

Mr. George T. Roumell, Jr.

Mr. William M. Saxton

Mr. Douglas H. West

Mr. Richard P. Condit

Mr. Kenneth B. McConnell

Mr. Robert J. Lord

Mr. Robert A. Derengoski

Mr. Alexander B. Ritchie

Mr. J. Harold Flannery

Mr. Jack Greenberg

Mr. E. Winther McCroom

Mr. Nathaniel R. Jones

Mr. Bruce Miller

Mr. Ralph B. Guy, Jr.

Mr. Theodore Sachs

Mr. William T. Downs

Mr. Theodore W. Swift

Mr. Irwin Ellman

Re: Ronald Bradley, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v s .

William G. Milliken, Governor of Michigan, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

Case Nos. 72-1809, 72-1810, 72-1811, 72-1812, 72-1813, 72-1814

Gentlemen:

Enclosed is a copy of the Court's opinion which was

announced today in the above-entitled cases.

A judgment in conformity with the opinion has been

entered today as required by Rule 36.

Yours very truly

James A. Higgins, Clerk

Chief Deputy

Enclosure