Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corporation Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

April 30, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corporation Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1970. f3843738-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f9cda41d-5631-4d1c-b250-b3834ba4f3f6/phillips-v-martin-marietta-corporation-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

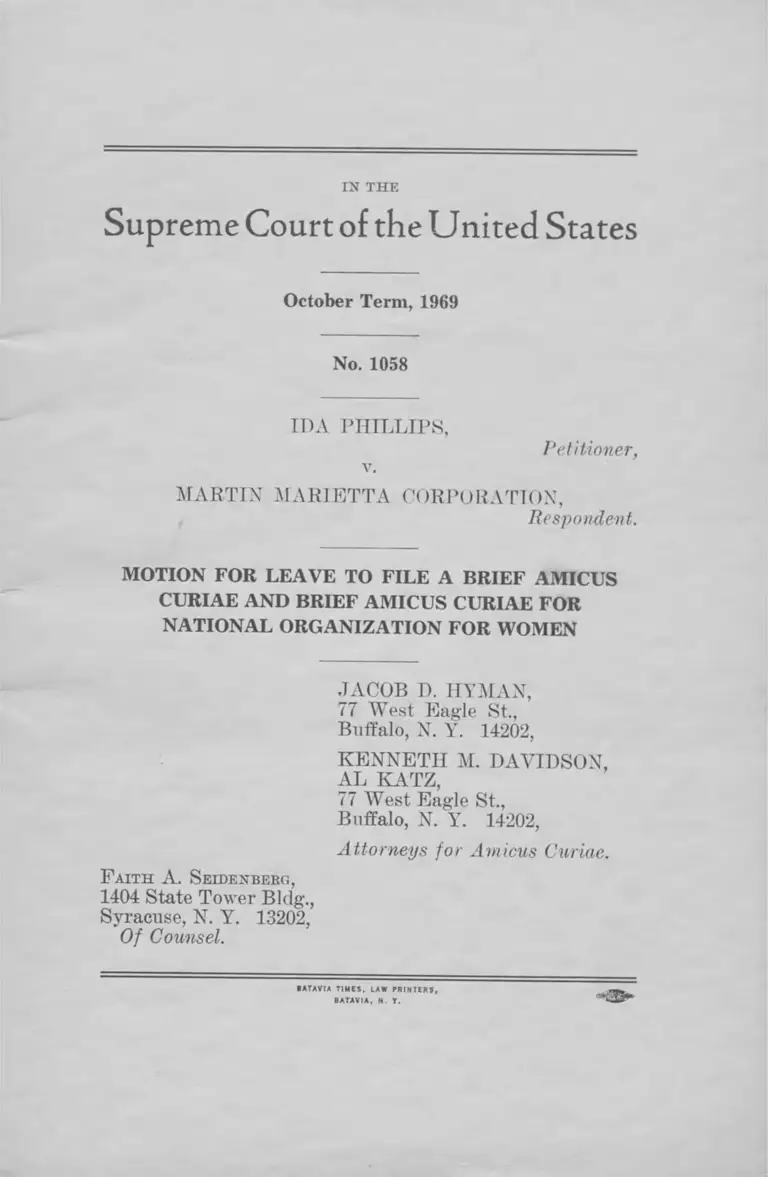

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1969

No. 1058

IDA PHILLIPS,

Petitioner,

v .

MARTIN MARIETTA CORPORATION,

Respondent.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF AMICUS

CURIAE AND BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE FOR

NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN

JACOB D. HYMAN,

77 West Eagle St.,

Buffalo, N. Y. 14202,

KENNETH M. DAVIDSON,

AL KATZ,

77 West Eagle St.,

Buffalo, N. Y. 14202,

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae.

F aith A. Seidenberg,

1404 State Tower Bldg.,

Syracuse, N. Y. 13202,

Of Counsel.

BATAVIA TIMES, LAW PRINTERS,

BATAVIA, N Y.

INDEX.

PAGE

Motion and Interest of Amiens ..................................... 1

Statement of Case ............................................................ 4

Argument .......................................................................... 5

I. The impact of tire decision below on the right of

women to be free from discrimination in em

ployment indicates Congress did not intend the

result reached by the courts below........................ 5

a. The result is inconsistent with the overall

federal policy of enabling women to work. . . 5

b. The number of women who may be adversely

affected by the decision below indicates its in

consistency with Congressional intent ............ 8

TT. The decision below is inconsistent with the lang

uage of the statute and the interpretation of it by

the courts to the extent it requires discrimination

be directed against an entire class to constitute

a violation of § 703(a) ............................................. 10

III. The order on remand should require Respondent

to justify its employment practice under § 703(e). 13

Conclusion ........................................................................ 14

Table of Cases.

Allen Bradley Co. v. Local Union No. 3, 7. B. E. TT'., 325

XL -S. 797 (1945) ............................................................ 0

Bing v. Roadway Express, Inc., 00 CCII Labor Cases

9232 (D. C. Ga.) (1908) ............................................... 12

Cooper v. Delta Airlines, Inc., 274 F. Rupp. 781

(1907) ..............................................................................9,10

Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corporation, 411 F. 2d 1

(1969) ...................................................................4 ,5 ,6 ,9,10

Phillips v. Martin. Marietta Corporation, 410 F. 2d 1257

(1969) .............................................................................. 3,4

Qvarles v. Philip Morris, 279 F. Rupp. 505 (1908)........ 12

i r .

PAGE

United States v. Local 189, United Papermakers and

Paperworkers, 282 F. Supp. 39 (1968) . . . . . . • • • • • •

Universal Camera Corporation v. National Labor Rela

tions Board, 340 U. S. 474 (1951) . . . . . . . •• •••••••

Weeks v. Southern Bell Tel. <& Tel. Co., 408 F. 2d 228

(1969) .............................................................................

12

6

5,14

Statutes.

5 U. S. C. § 7151........

42 U. S. C. § 630 ..........

42 U. S. C. § 2000e-2(a)

42 IT. S. C. § 2000e-2(e)

42 U. S. C. $ 2711........

42 U. S. C. * 2728 ........

77 Stat. 5 6 ...................

.......... 6

.......... 7

4.11,12,13

...5 ,13 ,14

.......... 7

.......... 7

.......... 6

R egulations.

29 C. F. R. 1604.1(2) .......................

(Proposed) 60 C. F. R. 60-20.3(b) . .

33 Fed. Reg. 10026 ...........................

M iscellaneous.

1969 H andbook on W omen W orkers, U. S. Department

of Labor, Women’s Bureau Bulletin 294 ..............2, 3, 8, 9

Federal Fund for Day Care Projects, Women’s Bureau,

IT. S. Department of Labor (1969) ............................. ‘

IN TH E

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1969

No. 1058

TDA PHILLIPS,

v.

Petitioner,

MARTIN MARIETTA CORPORATION,

Respondent.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF AMICUS

CURIAE AND BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE FOR

NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN

Having been denied consent to file a brief amicus curiae

by the Martin Marietta Corporation, the National Organi

zation for Women respectfully prays that the Supreme

Court of the United States grant it leave to file a brief

amicus curiae in the case of Ida Phillips v. Martin Marietta

Corporation now before the court.

Motion for Leave to File a Brief Amicus Curiae

and Interest of Amicus

The National Organization for Women (NOW) was

founded in 1966 by women and men concerned by the

personal and national losses resulting from discrimination

against women. The purpose of the organization is “ to

take action to bring women into full participation in. the

mainstream of American society, now, exercising all the

privileges and responsibilities thereof in truly equal part

nership with men. This purpose includes, but is not limited

to, equal rights and responsibilities in all aspects of citizen

ship, public service, employment, education and family life

and it includes freedom from discrimination because of

marital status or motherhood.” (§2 of Chapter by-laws

of National Organization for Women.)

In an effort to implement its goals the National Organi

zation for Women has taken stands on and worked for the

passage of an equal rights for women amendment to the

United States Constitution, abolition of laws penalizing

abortion, revision of state protective laws for women, and

amendments to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which would

grant the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission the

power to issue cease and desist orders.

In pursuing these goals NOW has solicited a broad

membership guaranteeing the right to join regardless of

race, color, sex, religion, national origin, age or economic

status. The organization has over 50 chapters in more than

24 states and a paid membership in excess of 3000.

The need for an organization to promote and protect the

rights of women, and in particular working women, is

clear. The 1969 H andbook on W omen W orkers (herein

after H andbook) published by the Women’s Bureau of the

United States Department of Labor, reports that while

sixty-five percent of the growth of the national labor force

since 1940 has been due to the increase in number of women

workers (H andbook p. 5), the incomes of women working-

full time is not only less than two-thirds of that earned

by men working full time, but also the gap between men

and women’s income widened during the period between

3

1956 and 1966 (H andbook pp. 133-4). Despite the passage

of the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, the trend in favor of discrimination

does not appear to be abating.

In this context the case of Ida Phillips v. Martin Marietta

Corporation now before the court is of immense impor

tance. As stated by Chief Judge Brown in his dissent

from denial of rehearing and petitioner in his brief, if the

decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit is upheld, “ the Act is dead,” (416 F. 2d 1257,

1260 (1969)) at least for women, and with it the rights

of women will have been severely curtailed.

In their briefs recpiesting writ of certiorari petitioner

and the United States have expressed overriding concern

for the preservation of the entirety of Title VII. They

understand that the decision below would undermine the

efficiency of Title VII with regard to racial, religious and

national origin, as well as sexual discrimination. For this

reason neither petitioner nor the United States has devoted

its full attention to the issue of sex discrimination. Neither

has, for example, explored the effects of the decision below

on other governmental projects, such as day care centers

and work incentive programs, which are designed to assist

and encourage mothers with preschool children to seek and

maintain employment.

NOW, representing a more narrow institutional interest

than either petitioner or the United States, is primarily

concerned with women’s freedom from sex discrimination.

The direct importance of the case to the 14.4 million

mothers with preschool children and the implications for

all American women require the fullest possible considera

tion of the issues. NOW, as an organization dedicated to

4

the equality of women, therefore requests leave to file a

brief amicus curiae in the case of Ida Phillips v. Martin

Marietta Corporation.

Respectfully submitted,

JACOB D. HYMAN,

KENNETH M. DAVIDSON,

AL KATZ,

77 West Eagle St.,

Buffalo, N. Y. 14202,

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae.

F aith A. Seidenberg,

1404 State Tower Bldg.,

Syracuse, N. Y. 13202,

Of Counsel.

Statement of Case

The question before the Court is whether an employer

may escape the prohibitions against discriminating on the

basis of sex contained in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 when it refuses to hire women with preschool

children while at the same time it hires men with preschool

children.

The pertinent provision of the Act states: “ It shall be

an unlawful employment practice for an employer . . . to

. . . refuse to hire . . . any individual . . . because of

such individual’s . . . sex.’ ’ (§ 703(a) of Civil Rights Act

of 1964, (42 U. S. C. 2000(e)-2(a)).

In reviewing petitioner’s claim, the Court ot Appeals

below stated:

“ The evidence presented in the trial court is quite

convincing that no discrimination against women as a

whole or the appellant individually was practiced by

Martin Marietta” (411 F. 2d 1 at 4 (1969)).

The Court concluded that the hiring practices of Martin

Marietta were permissible because they only discriminated

against a sub-class of women, “ i.e., a woman with preschool

age children” (411 F. 2d 1 at 4 (1969)). The effect of these

two statements is that a prima facie violation of the Act

cannot be established unless an employer denies employ

ment to all women.

Thus the initial issue before the court is vot whether the

respondent has violated the Act (although there may be

sufficient facts to make such a determination) nor is the

issue whether the Act envisions circumstances in which

men and women may be lawfully treated differently.

Rather, the initial issue before the court is whether a prima

facie case of discrimination exists against the employer

when he imposes conditions to the hiring of persons of

one sex that are not applied to persons of the other sex.

Once the complainant has established a prima facie case

of discrimination, the burden then shifts to the employer

to show that “ sex . . . is a bona fide occupational qualifica

tion reasonably necessary to the normal operation of that

particular business or enterprise.” § 703(e) of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U. S. C. §2000e-2(e). Weeks v.

Southern Bell Tel. & Tel. Co., 408 F. 2d 228 at 232 (1969).

ARGUMENT

I. The impact of the decision below on the right of

women to be free from discrimination in employment indi

cates Congress did not intend the result reached by the

courts below.

a) The result is inconsistent with the overall federal policy

of enabling women to work.

As the Court below recognized, “ it is well established

administrative law that the construction put on a statute

G

by an agency charged with administering it is entitled to

deference by the courts . . . ” (411 F. 2d 1, 3 (1969)). It

is also well recognized that in construing the provisions

of an act the courts should look to the provisions and inter

pretations of related acts, (Universal Camera v. NLRB,

340 U. S. 474 (1951)) and should take into account the

impact of its interpretation upon related acts. Allen Brad

ley Co. v. Local Union No. 3, 1BEW, 325 XL S. 797 (1945).

The sex discrimination provisions of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 are only a part of the federal statutory scheme

designed to prohibit discrimination against women in em

ployment and promote growth and stability in the national

labor force. In the Equal Pay Act of 1963 the Congress

specifically declared that “wage differentials based on sex

. . . depress wages and living standards . . . prevent the

maximum utilization of . . . labor resources . . . burden

commerce . . . and constitutes an unfair method of com

petition.” 77 Stat. 56 (1963). After the passage of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 the Congress reaffirmed that

” [i]t is the policy of the United States to insure equal

employment opportunity for employees without discrimina

tion because of . . . sex . . . ” 5 U. S. C. §7151 (1966)

and directed the President to use his powers to implement

the policy. By executive order the President charged the

Secretary of Labor with the responsibility of ensuring

that contractors with the United States take affirmative

action so that they null not discriminate on the basis of

sex (Executive Order 11375) and the Civil Service Com

mission with the responsibility of ensuring equal oppor

tunity for women in federal employment (Executive Order

11478).

Beyond the affirmative action involved within the scope

of the executive orders the Congress has specifically re-

I

quired that vocational training programs such as the Job

Corps be open to female applicants (42 IT. S. C. §2711)

and reinforced its determination in the case of the Job

Corps by amending the statute to mandate a minimum

percentage of females in the program (42 U. S. C. § 2728

(b )). The regulations issued under Work Incentive Pro

gram (42 U. S. C. §630 et seq. (1967)), provide vocational

training for mothers who are receiving or might in the

future receive public assistance, and provide day care cen

ters for their preschool children (33 Fed. Reg. 10026

(1968)). The federal government sponsors at least four

teen other programs which help finance child care centers

as well as five programs to train day care personnel and

four programs for experimentation designed to improve

child care.1

National policy to ensure equal employment opportunity

for all women, including mothers with preschool children,

has been reflected in decisions concerning the interpreta

tion of sex discrimination prohibitions. It is not only the

EEOC which has determined that refusal to hire women

with preschool children is discrimination based on sex. The

Labor Department has issued proposed regulations on the

same question:

“ An employer should not deny employment to women

with children . . . unless it has similar exclusionary

policies for men . . . ” (60 C. F. R. 60-20.3(b)).

This determination should also be given deference in deter

mining what constitutes discrimination against women.

Equally important are the effects of the decision below

upon the affirmative Acts which are designed to train women

workers and facilitate their employment. It is against

1 See, Federal Fuads for Pay Care Projects. Women’s Bureau, U. S. De

partment of Labor.

8

common sense to suppose that Congress would guarantee

equal employment opportunity to women, provide for train

ing of women workers, provide support for day care cen

ters, yet intend to allow employment discrimination against

women with preschool children.

b ) The number of women who may be adversely affected

by the decision below indicates its inconsistency with

Congressional intent.

In 1968, 29,204,000 women were in the labor force and

constituted over 37% of the labor force in the United

States. H a n d b o o k p. 9. The following table outlines

selected personal characteristics of women who were in

the labor force in 1967.

Selected Characteristics of Women in the

Labor Force2

Number in Percent of total

millions women in

Characteristic (000,000) labor force

Total Women in Labor Force 27.5 100.0%

Single 5.9 21.5

Married 17.5 63.5

Husband present 15.9 57.8

Husband absent 1.5 5.7

Widowed 2.5 7.0

Divorced 1.6 6.0

Mothers in the labor force

with children under 18 9.7 35.2

with children under 6 3.7 13.4

Child Care Arrangement of Working Mothers

with Children under 6 by percent3

Care in child’s own home 47%

by father 14.4%

by others 32.6%

Care outside child’s home 53%

2 Source, H andbook pp. 23 and 48 (Tables 7 and 21). Totals may not

add exactly due to rounding.

s Source, H andbook p. 49 (Table 22).

9

The decision below would permit any employer to refuse

to hire any of the 3.7 million mothers with children under

six who are currently in the labor force as well as the

additional 10.7 million mothers with children under six

potentially in the labor force.4 The decision takes note of

“ the differences between the normal relationships between

working fathers and working mothers to their preschool

age children . . . ” (411 F. 2d 1 at 4 (1909)) but does not

require the employer to justify his employment practice

either in terms of the needs of the business or in terms of

the disability of the applicant. The rule does not take into

account that over 10% of working women are heads of

families ( H a n d b o o k p. 128, Table 56). Nor does the deci

sion take into account that in families where mothers work,

almost 15% of their husbands care for the children while

the mothers work (see chart above). The decision below

simply says that Title VTT of the Civil Rights Act of 1904

affords no protection to women with preschool children.

Tn support of its position that mothers with preschool

children fall outside the Act, Respondent in its brief in

opposition to the writ of certiorari cites the case of Cooper

v. Delta Airlines, Inc., 274 F. Supp. 781 (1907), for the

proposition that women who are married may be refused

employment on the basis of their marital status without

violating the Act. While the 5th Circuit below charac

terized that case as one which permitted employers to

refuse to hire all married persons, Respondent's reliance

upon it indicates the inevitable implications of the decision

below. Tf an employer need not explain or justify why

women with preschool children are refused employment, if

the employer need only link femininity with some other

characteristic to avoid the Act, then employers who refuse

to hire women who are married must also be outside the

4 Interpolation from H andbook p. 30 (Table 16).

10

scope of the Act. Unlike the determination in Cooper v.

Delta Airlines, Inc., supra, there is no requirement that

the rule apply without regard to sex.

The effect of removing the protection of the Act from

married women would be to deny equal employment oppor

tunity to over 63% of the women in the labor force (see

chart above). Over seventeen million Americans currently

in the labor force would then be subject to discrimination

on the basis of a characteristic—being women—which they

are born into, but which bears no relation to their ability

to perform the work desired by the employer.

Under the reasoning of the court below any of the

selected characteristics listed in the chart above could be

used to avoid the prohibition on sex discrimination of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Court of Appeals decision

allows an employer to discriminate so long as he hires

some class of women without regard even to the size of

that class. It is not reasonable that the Congress would

have passed an act with such limited effect. There is no

evidence that this was their intention and such futility

should never be presumed.

II. The decision below is inconsistent with the lan

guage of the statute and the interpretation of it by the

courts to the extent it requires discrimination he directed

against an entire class to constitute a violation of § 703(a).

The Court of Appeals below stated:

“ When another criterion of employment is added to

one of the classifications listed in the Act, there is no

longer apparent discrimination based solely on race,

color, religion, sex or national origin” (411 U. 2d l

at 3-4 (1969)).

1 1

This means that the employment practice must apply to

the entire class, all women, before a violation of § 703(a)

can be established. Such an interpretation does not make

sense as it would allow a company to refuse to hire women

who are under sixty-five (no discrimination on the basis

of sex) or refuse to hire Italian men who are single (no

discrimination on the basis of national origin) or refuse to

hire Jews who do not have PhD’s in nuclear physics (no

discrimination on the basis of religion) or, refuse to hire

blacks who are not over six and a half feet tall (no dis

crimination on the basis of race or color). The fact that

such results would strip the statute of practical meaning

should have indicated there was a problem in the Fifth

Circuit’s reading of the statute.

If the statute were to read—employment discrimination

against all women shall he unlawful— , then it might be

an open question whether the intent of the statute was

to prohibit “ discriminations only when they apply to all

women” or to prohibit “ all discriminations against each

and every women that was based on her femininity.”

§ 703(a) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, however, did not

frame the statute in that manner. The statute states that

it is unlawful to refuse to hire an individual “because of

such individual’s race, color, religion, sex or national

origin.” The statute makes unlawfulness turn on the basis

by which the employer distinguishes between the person

hired and the person refused. Tf the difference between

the person hired and the person refused is the individual’s

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, then the em

ployment practice is unlawful. In Mrs. Phillips’ case, it

is obvious that the basis of Martin Marietta’s refusal to

hire her was her sex. The District Court found Martin

Marietta “ does employ males with preschool children”

12

(Petitioner’s Appendix p. 23a). Martin Marietta refused

to hire Mrs. Phillips because she had preschool children.

The corporation’s rule distinguishes between applicants

who have preschool children on the basis of the individual’s

sex.

The Court of Appeals “ coupling” rationale ignores the

terms of the statute. It fails to determine the basis on

which the employer distinguishes between similarly situ

ated applicants. Sex-plus hiring practices could only be

held lawful if § 703(a) prohibited discrimination solely

when it was practiced against an entire class. Such an

interpretation is not only inconsistent with the words of

the statute, it is also implicitly inconsistent with previous

cases.

Because it had never been suggested, before the decision

below, that § 703(a) covers only discrimination against

entire classes, the courts have never explicitly ruled upon

the question. Nevertheless decisions concerning the Act

have consistently found violations where less than the en

tire class was subject to discrimination. For example in

Quarles v. Philip Morris, 279 F. Supp. 505 (1968), the

court found a violation even though the discriminatory

seniority system only affected blacks hired prior to pas

sage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Cf. United States v.

Local 18!) United Papermakers and Paperworkers, 282 F.

Supp. 39 (1968), Bing v. Boadirag Express Inc., 60 COH

Labor Cases 9232 (1968) (Not otherwise reported).

These cases were of course more difficult than the case

now before the court. The cases dealt with rules that did

not apply solely to blacks or even affect all black em

ployees ; rather the rules primarily affected some black

employees. Unlike the rule which barred Mrs. Phillips,

13

the rules in those cases were neutral on their face. Only

after a factual determination were the rules characterized

by the courts as being discriminatory and then only as to

some black employees. It was not thought necessary and

indeed would have been impossible to show that all black

employees suffered from the rule. The only factual inquiry

that is necessary is that the employer based his employ

ment practice upon a forbidden criterion—race, color,

religion, sex or national origin. Once such determination

is made a prima facia case of discrimination is established.

The District Court determined that the Martin Marietta

Corporation hired applicants with preschool children ex

cept those of the female sex. This determination should

have compelled the court to find that the Martin Marietta

Corporation had engaged in an employment practice pro

hibited by § 703(a) and constituted a prima facia viola

tion of Title V II of the Civil Rights Act of 1904.

III. The order on remand should require Respondent

to justify its employment practice under § 703(e).

Respondent may feel a determination that it has refused

women employment in violation of § 703(a) is unjust be

cause it has a high percentage of women employees. But

such a determination does not preclude Respondent from

showing that the use of sex as a hiring criterion is justi

fied. § 703(e) of the Act specifically recognizes that an

individual’s religion, sex, or national origin may be an

appropriate hiring criterion in certain instances. For

example sex is appropriate where the employment involves

the portrayal of a member of one sex (29 C. F. R.

1004.1(2)). Respondent has the opportunity to show that

its hiring rule is “ reasonably necessary to the normal

14

operation of [its] business . . . ” (§ 703(e) of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 IT. S. 0. § 2,000e-2(e)).

The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has set out

the basic standard by which Respondent’s justification of

its hiring practice should be judged in Weeks v. Southern

Bell Tel. & Tel. Co., 408 F. 2d 228 (1969).

“ We conclude that the principle of nondiscrimina

tion requires that we hold that in order to rely on the

bona fide occupational qualification exception an em

ployer has the burden of proving that he had reason

able cause to believe, that is, a factual basis for be

lieving, that all or substantially all women would be

unable to perform safely and efficiently the duties of

the job involved.” 408 F. 2d at 235.

Respondent should be required to prove that all or sub

stantially all women with pre-school age children would be

unable to perform the duties of the job involved.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons it is urged that the Court

should reverse the ruling below.

R espectfully subm i tted,

JACOB D. HYMAN,

KENNETH M. DAVIDSON,

AL KATZ,

77 West Eagle Street,

Buffalo, N. Y. 14202,

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae.

F atth A. Seidenberg,

1404 State Tower Bldg.,

Syracuse, N. Y. 13202,

Of Counsel.

15

Certificate of Service

I, Jacob D. Hyman, attorney of record for Amicus

Curiae, and a Member of the Bar of the Supreme Court

of the United States, hereby certify that on the day of

April, 1970, I served the requisite number of copies of the

foregoing Brief upon Jack Greenberg, James M. Nabritt,

ITT, Norman C. Amaker, William L. Robinson, Lowell

Johnston, Velma Martinez Singer, 10 Columbus Circle,

New York, New York 10019, and Earl M. Johnson, 625

West Union Street, Jacksonville, Florida 32202, Attorneys

for Petitioner and William Y. Akerman, Suite 506 First

National Bank Building, P. 0. Box 231, Orlando, Florida

32802, Attorney for Respondent and Erwin Griswold,

Solicitor General, Department of Justice, Washington, D.

C. 20025, by depositing the same in the United States mail,

air mail postage prepaid, and properly addressed to them

at the addresses given.

J

JACOB D. HYMAN,

77 AVest Eagle St.,

Buffalo, N. l r. 14202.