League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), Council #4434 v. Mattox Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 15, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), Council #4434 v. Mattox Brief Amicus Curiae, 1991. 46ea7ada-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f9f68777-0b83-466c-baa7-98efde490b38/league-of-united-latin-american-citizens-lulac-council-4434-v-mattox-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

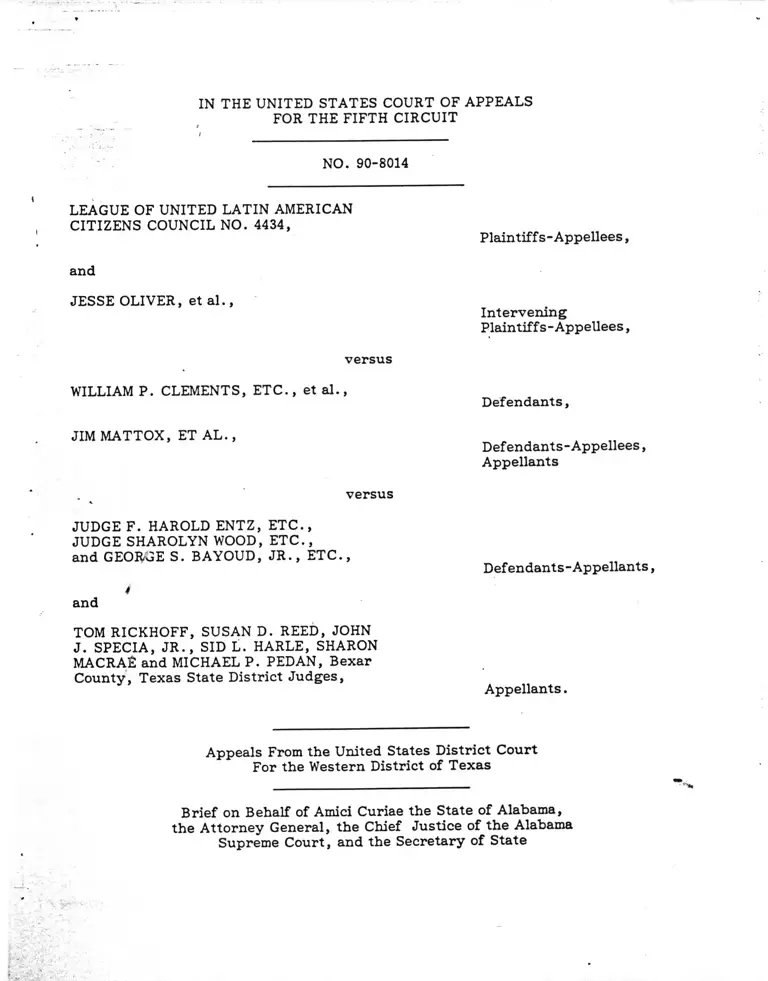

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 90-8014

LEAGUE OF UNITED LATIN AMERICAN

CITIZENS COUNCIL NO. 4434, Plaintiffs-Appellees,

and

JESSE OLIVER, et al., Intervening

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

versus

WILLIAM P. CLEMENTS, ETC., et al., Defendants,

JIM MATTOX, ET A L., Defendants-Appellees,

Appellants

versus

JUDGE F. HAROLD ENTZ, ETC.,

JUDGE SHAROLYN WOOD, ETC.,

and GEORGE S. BAYOUD, JR., ETC., Defendants-Appellants,

4

and

TOM RICKHOFF, SUSAN D. REED, JOHN

J. SPECIA, JR., SID L. HARLE, SHARON

MACRAE and MICHAEL P. PEDAN, Bexar

County, Texas State District Judges,

Appellants.

Appeals From the United States District Court

For the Western District of Texas

Brief on Behalf of Amici Curiae the State of Alabama,

the Attorney General, the Chief Justice of the Alabama

Supreme Court, and the Secretary of State

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 90-8014

LEAGUE OF UNITED LATIN AMERICAN

CITIZENS COUNCIL NO. 4434,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

and

JESSE OLIVER, et a l.,

Intervening

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

versus

WILLIAM P. CLEMENTS, ETC., et al., Defendants,

JIM MATTOX, ET A L., Defendants-Appellees,

Appellants

versus

JUDGE F. HAROLD ENTZ, ETC.,

JUDGE SHAROLYN WOOD, ETC.,

and GEORGE S. BAYOUD, JR., ETC., Defendants-Appellants,

and

TOM RICKHOFF, SUSAN D. REED, JOHN

J. SPECIA, JR., SID L. HARLE, SHARON

MACRAE and MICHAEL P. PEDAN, Bexar

County, Texas State District Judges,

Appellants.

Appeals From the United States District Court

For the Western District of Texas

Brief on Behalf of Amici Curiae the State of Alabama,

the Attorney General, the Chief Justice of the Alabama

Supreme Court, and the Secretary of State

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

I. Minority Interest in Minority Representation

II. State Interests ...........................................

III. Conclusion ....................................................

i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES PAGE

Thornburg v. Gingles,

479 U.S. 30, 45 (1986)

(quoting S. Rep. No. 97-417 at 29 (1982))

OTHER AUTHORITIES

The Triumph of Tokenism: The Voting Rights Act

and the Theory of Black Electoral Success,

89 Michigan Law Review 1077, 1093 (March 1991) . . . .

Maps and Misreadings: The Role of Geographic Compactness

in Racial Vote Dilution Litigation,

24 Harvard Civil Rights - Civil Liberties Law Review 173,

218 (1989) .............................................................................

ii

BRIEF OF THE STATE OF ALABAMA AS AMICUS CURIAE

This Court is well aware that voting rights cases concerning the election of

state judges similar to that which it now considers on remand from the Supreme Court

are currently pending in federal court in Alabama, as well as in several other states.

The decision of the Fifth Circuit in this case will substantially influence the

disposition of these cases. We write, therefore, to supplement the briefs of

defendants with several points that we think bear further emphasis.

The Court's questions for counsel, circulated August 6, 1991, suggest that

it is struggling with the question of how to build the proper analytical framework in

which to consider a host of factors — for example, minority interests, state

interests, racial bloc voting, other traditional Zimmer factors, etc. This brief does

not attempt to respond to those questions or examine possible models for analysis in

a comprehensive way. Rather, Alabama assumes the necessity for some kind of

balancing or totality of the circumstances inquiry in which "'there is no requirement

that any particular number of factors be proved, or that a majority of them point one

way or the o t h e r , Thornburg v. Gingles, 479 U.S. 30, 45 (1986) (quoting S. Rep.

No. 97-417 at 29 (1982)), and in which "other factors [than those enumerated in the

Senate Report] may also be relevant and may be considered." Thornburg, 478 U.S.

at 45. Alabama submits that in the context of judicial elections, the weight and

relevance given to certain factors in whatever analysis the Court adopts should

differ from that afforded in the traditional Section 2 case in several ways.

I.

Minority Interest in Minority Representation

The Court’s first question for counsel implicitly recognizes that assessment

1

of a Section 2 claim necessarily involves some balancing of minority and state

interests ■which, under varying factual circumstances, may have differing weight

and emphasis. In the judicial context, the minority’s interest in equal participation

and influence in the electoral process has been effectively defined - - at least since

the Thornburg decision in 1986 - - as an interest in minority electoral success. See

Thornburg, 478 U.S. at 92-93 (O'Connor, J . , concurring) ("Electoral success has

now emerged, under the Court's standard, as the linchpin of vote dilution claims." ) ;

see also Lani Guinier, The Triumph of Tokenism: The Voting Rights Act and the

Theory of Black Electoral Success, 89 Michigan Law Review 1077, 1093 (March 1991)

("Especially since 1986, the courts have measured black political representation and

participation solely by reference to the number and consistent election of black

candidates."). This is perhaps the primary reason that single-member districting

has enjoyed pride of place as a Section 2 remedy: sub-districts guarantee that a

compact and cohesive minority group can elect an officeholder of its own, and the

concomitant sacrifice of influence by that group on other candidacies in other single

member districts has been thought to be worth the gain in direct representation.

This trade-off of influence must be reexamined in judicial elections because of

structural differences in the offices to be filled. The minority's interest in black

electoral success is logically weakened in this context in two ways. First, no group,

minority or majority, has a strong claim to be represented by its own judges, who -

- as has been exhaustively discussed -- do not speak for and may not "belong to

particular groups consistently with the definition of their offices. To the extent that

there is a participational value to be served by specifically black electoral success,

it is not the powerful value of interest representation for voters, but the relatively

weaker symbolic or exemplary value for the black community of diversity on the

bench - - sometimes discussed in terms of judges' ability to be "role models" or to

2

make litigants feel more comfortable or secure. The latter value is not at all a

negligible one, but neither is it one uniquely important to blacks or clearly protected

as a major voting concern by Section 2. To put this point another way, in the judicial

context, the interest of the minority may be far more closely aligned with that of the

majority - - in this case, every citizen's interest in judicial impartiality, fairness and

independence — than is so in electoral settings in which the minority has a

distinctive claim to representation of its own unique concerns against those of the

larger group.

Second, the minority's interest in election of its own candidates, as opposed

to the alternative of influence on the broader range of officials in a given

jurisdiction, is weakened by the structure of decision making in the judicial office.

Where black voters can propel black candidates onto collegial bodies such as city

councils or county commissions, they may achieve direct and consistent

representation of their interests in all decisions made by that body and realize the

chance to be central to legislative deliberation and coalition-building on each issue

considered. As one voting rights advocate has put it:

It is critical to this process . . . that an advocate of the

distinctive minority perspective be present to advance its

views. In this sense, a strong commitment by a few

persons to address these concerns is preferable to a

weaker commitment by many persons.

Pamela S. Karlan, Mans and Misreadings: The Role of Geographic Compactness in

Racial Vote Dilution Litigation, 24 Harvard Civil Rights - Civil Liberties Law Review

173, 218 (1989).

The structure of the office of trial judges, however, forecloses this

opportunity for direct participation by the minority's representatives in all

deliberations and decisions of a governing body. Because judicial decisions are not

3

made collectively, minority judges will decide only their own cases, and no others.

The odds are low that minority voters will appear exclusively - - or even most

frequently - - before minority judges. The interest in black electoral success in this

context is, thus, diminished; such success brings a great deal less in terms of

participation in ultimate decision-making to minorities than would be the case in non

judicial elections, while influence on the election of non-minority candidates is

concomitantly more important.

There is an additional limitation on black electoral success imposed by the

unique structure of judicial office that may not so much diminish the weight of the

minority interest in such success as alter assessment of that interest's impairment:

qualifications for judicial office. Judges in most states, of course, must be lawyers;

in some states, such as Georgia, lawyers must actually be members of the bar for a

number of years before they qualify for election as judges. See Georgia Const., Art.

VI, Sec. VII, Par. 11(a) (seven year bar membership requirement for superior

judges). In contrast, the legal qualifications for individuals to hold non-judicial

offices typically involve no more than age, residency and citizenship requirements.

When blacks are not represented in the bar in numbers commensurate with their

presence in the general population - - as in Alabama, as well as Texas there is

obviously an inherent limitation on the opportunity for black electoral success in

judicial races not present in non-judicial elections. Thus, the degree of the

minority's interest in the election of minority candidates is bounded by the

availability of black lawyers eligible for such offices.1

1 Alabama is not suggesting that this candidate pool is actually exhausted

although in some counties this is the case. However, there is no reason to suppose

that all black lawyers — or more black than white lawyers - - want to be judges or are

viable candidates (absent any racial considerations) for the office of judge. Thus,

the limitation is a real one.

4

The three ways2 cited above in which the traditional minority interest in black

electoral success is diminished in the judicial context have certain practical

consequences for an assessment of wThether the totality of the circumstances

establishes a violation of Section 2 in this case. The Thornburg Court has identified

"the most important Senate Report factors bearing on §2 challenges to multi-member

districts" as "'the extent to which minority group members have been elected to

public office in the jurisdiction' and the 'extent to which voting in the elections of

the . . . political subdivision is racially polarized.'" Thornburg, 478 U.S. at 48 n. 15

(quoting S. Rep. 28-29). Clearly, proof that blacks are. not represented on the

bench in proportion to their numbers in the population carries less weight here than

would similar proof-in a non-judicial context. Representation is not a goal of the

judiciary, and the minority interest in black representation is, at best, an

attenuated interest in simple diversity, not the stronger, more traditional claim to

elect office-holders to act as responsive ears and distinctive voices for blacks . This

is particularly true when no collegial decision-making body exists to provide black

judges an opportunity for direct influence over every judicial decision - - where, in

fact, black political influence on white judges, who will likely make the majority of

the decisions allocated to judges in a given jurisdiction, and do so without

consultation, may be much more important to overall black influence and participation

then minority electoral success.

Evidence of black representation on the bench in numbers lower than black

presence in the population is also a great deal less meaningful in the judicial than in

the legislative context. Unless black candidates are - - solely because of their race

- to be guaranteed by Section 2 an exponentially greater opportunity than whites to

2 The lack of a one-person one-vote requirement in judicial elections also

imposes a limit on the minority interest in equal participation because equally

weighted votes are not required.

5

serve as elected judges, then the only fair measure of black presence on the bench

is black presence in the pool of qualified candidates for the bench. Accordingly,

proof that for example, in Harris County, Texas, black judges represent 5.1 percent

of the bench, while eligible black lawyers make up only 3.8 percent of the bar, ought

to make a substantial difference in the Court's assessment of black electoral

success.3

Review of the second important Senate factor identified by the Thornburg

Court, racial polarization, should also differ somewhat in the judicial context for

reasons outlined above. Plaintiffs' experts routinely focus exclusively on polarization

in contests in which blacks run against whites. Yet — uniquely in judicial elections -

- the extent to which minority voters are instrumental in choosing those who will

make most judicial decisions turns on minority influence on the election of majority

candidates absent collegial decision-making. Thus, white support for white

candidates who are also committed to be responsive to the black electorate is highly

relevant information for a federal court charged with assessing the legal significance

of racial bloc voting.

II.

State Interests

While the minority's interest in electing black judges is substantially less than

its interest in electing more black representatives in other contexts, the state

interests in maintaining existing systems for electing judges are particularly strong.

Although these interests are ably discussed in other briefs, some amplification here

3 In Alabama, some 3.3 percent of the in-state bar is black, but 4.6 percent of

elected trial judges are black.

6

may be helpful. Indispensable to any analysis of a state's interest in perpetuating

its judicial election system is an assessment of the available alternatives. Choices are

not made in the abstract, and any given system - - rather than being perfect - - may

simply be the lesser of two or three evils, or the best balance of a number of

competing interests that appears to be available.

At-large multi-member systems for electing trial judges reflect such a balance.

The alternatives - - single-member subdistricts, or novel systems such as cumulative

or limited voting - - do perhaps offer to enhance diversity on the bench by adding

more minority judges. We note, however, that this is all those systems offer to the

judiciary. Whereas single-member districts, and even semi-proportional systems like

cumulative or limited voting, have been advocated - - and sometimes employed -- as

viable alternatives commanding popular support for use in city council or legislative

elections, these have never been employed (outside the context of a lawsuit, as in

Mississippi) to elect judges. Independently of these latter day vote dilution cases,

there is no constituency or track record whatsoever for use of such systems in the

judicial context — and with good reason.

The choice to elect trial judges offers an important measure of accountability

and legitimacy to a state judiciary. But a principal evil of such a choice is the threat

of politicization of the judicial function - - the possibility of a constituency-based

system of justice, or the appearance thereof, in which judges are pressured to play

to the gallery for votes, and to sacrifice fairness and impartiality to the demands of

the interests that put them, and keep them, in power. Elections also threaten to

erode the competence and quality of the judiciary; a good lawyer is unlikely to leave

an established practice for a judgeship where elections are always, and often,

contested and single-issue politics may easily prevail.

A state obviously has a compelling interest in checking and curbing these less

7

wholesome tendencies of electoral systems. Its tools include such things as provision

for longer than average terms for judges, strict canons of judicial conduct,

attractive retirement plans - - and, not least, election systems that themselves

reduce politicization and promote the retention of competent judges. At-large

elections, for example, mitigate strongly against the tendency of popular vote to

promote judicial bias and partiality, or pressures towards those ends, by offering

a judge the buffer of a broad electoral base and enabling him or her to withstand,

insofar as possible, the pressures of public opinion — in short, to act with courage

and integrity. The minority interest in a system of this-kind is itself extremely

strong in the judicial context; it is often the powerless and the unpopular that are

protected by judicial independence.

Single-member districts, in contrast, bring judges uncomfortably close to the

electorate. In Alabama, for example, if Jefferson County (Birmingham) were divided

into 24 single-member subdistricts, one for each circuit judge, the number of

electors entitled to vote for each judge would decrease from 488,937 (measured by

voting age population) to 20,372 per judge. In such a situation, there is simply, as

one Alabama judge has put it, no "shock absorber" to aid a judge in "surviving

difficult decisions in controversial cases." A judge who "values his or her career on

the bench, or who is approaching the last election necessary to accumulate vested

retirement benefits, would be foolish indeed not to be aware of (and possibly bend

to) the views of vocal, influential, or powerful interest groups in his or her district

when deciding cases."

Although single-member districts can compromise the appearance (and reality)

of an independent judiciary, they do offer one considerable advantage: incumbent

judges are not all compelled to run against each other in every election. Within any

given district, the incumbent faces a contest only from new challengers, not from his

8

or her colleagues on the bench, and seats may not always be contested. Where, as

in judicial elections, single-member districts are an undesirable alternative,

numbered places in at-large elections also offer the same advantage.

The primary reason for providing a measure of protection to incumbents from

inevitably contested elections is the state’s strong interest in judicial competence.

Unlike legislators, county commissioners, school board members, and many city

officials, judges serve full-time; their jobs are their careers (an arrangement that,

itself, serves the state's independence and competence interests). A career marked

by the threat of perpetual instability, with contested elections guaranteed every six

years, is hardly an attractive one to the best candidates, who typically can rely

on the expectation of greater longevity as well as greater remuneration in private

law practice.

The state's interest in judicial competence is served in at least two other ways

by numbered places. In situations in which an incompetent judge clearly needs to be

removed, it is difficult for the electors to target only that judge for defeat in a pure

at-large system. Since all the judges must run against each other at the same time,

all judges are in jeopardy of defeat where perhaps only one seat would otherwise

have attracted a contest. Further, because contested elections would require judges

to campaign particularly against their colleagues, the collegiality of the bench may

be diminished, and judges encouraged to "keep book" on one another. Good

candidates might again find standing for election less than attractive.

Numbered places in at-large elections can also enhance the independence of

judges, who must be specifically targeted, challenged one-on-one, and voted out by

a substantial segment of voters to be reliably unseated in such a system. This may

make sweeps of elections, or wholesale turnover, less likely, and arguably reduces

the need for judges to play politics. The assurance that not every election will

9

inevitably be contested also reduces candidates’ needs for campaign funds and,

again, offers judges additional insulation from politics.4

Limited and cumulative voting systems are no better than single-member

districts. Indeed, they preserve the disadvantages of such systems without realizing

the advantages of at-large numbered place elections. In a limited vote system the

voter must cast fewer votes than the number of seats to be filled. The form of limited

vote most often advocated by voting rights plaintiffs is the single non-transferrable

vote system (SNTV), in which voters are given only one vote. In an SNTV system

the threshold of exclusion5 (that is, the level of support for a candidate at which

a given group cannot be denied a seat) is lower than that in a comparable at-large,

numbered-place election system - - hence, the appeal for minority voters.

In a cumulative vote system, a voter typically has many votes as there are

seats to fill but he or she can cumulate or aggregate those votes among a smaller

number of candidates, giving a preferred candidate more than one vote. Like limited

voting, cumulative voting reduces the threshold of exclusion, enhancing the ability

of a cohesive minority group to elect a candidate. The threshold of exclusion in such

a system is the same as that for an SNTV system.6

4 Such insulation is particularly important in judicial races, which do not always

generate broad public interest and tend to be financed by lawyers and frequent

litigators - - who perhaps offer the greatest potential threat to judicial independence

or the appearance thereof.

5 The formula for calculating the threshold of exclusion is :

Number of votes each voter can cast

Number of votes each voter can cast plus number of seats to be filled.

6 The formula is:

1

1+ number of seats to be filled.

10

From the standpoint of the judiciary, the problems with the SNTV or

cumulative voting systems are substantial. First, these systems retain the chief

disadvantage of the single-member district system by ensuring that a judge’s

election may be determined by a very small proportion of the population. For

example, in the Tenth Circuit in Alabama, any cohesive group that can marshall

19,557 votes, or roughly four percent of the total voting age population, is assured

a seat. Of course, even a lower number of votes may elect a judge; the threshold of

exclusion represents the level of support at which a group is guaranteed a seat.

Once again, judicial independence - - or the appearance thereof - - may be

compromised by the fact that .this system rewards efforts to attract votes from small,

identifiable, cohesive groups that may, for example, coalesce around single

ideological issues. The need for judicial candidates to appeal broadly to a full range

of voters, and the relative political insulation that broad support provides, is

consequently diminished.

Not only is the state's interest in an independent, unbiased judiciary

compromised in such systems, but its interest in the legitimacy and authority of the

judicial office is adversely affected by public perception that very small groups of

voters are propelling judges into office. It is bad enough for a litigant to know that

he or she will appear before a neighborhood (perhaps not their neighborhood) judge,

as in a single-member district system. It is eminently worse for that litigant to be

aware that his or her case will be heard by the trial lawyers' judge, the NEA's judge,

the chamber of commerce's judge, the Eagle Forum's judge, or the ACLU's judge.

At the same time that limited and cumulative vote preserve, and arguably

enhance, this disadvantage of the single-member district system, they fail to realize

its chief advantage (and the advantage of numbered-places) for judges: the

assurance that elections are not inevitably contested. Incumbents have virtually no

11

protection in these systems. Not only must all the judges run against each other at

each election, but the number of votes required to unseat a judge, and end a career,

is substantially diminished. The incentive for a good candidate to leave private

practice for the bench is considerably undermined.

We note also that the advantages of these systems for racial minorities are not

absolutely clear. These systems require a great deal of cohesion, and highly

strategic voting, to operate properly; a minority group that concentrates its votes,

but still falls below the threshold of exclusion, may end up with no direct

representation at all, and no influence on other candidates whom it did not help elect

- - again, a particular problem where voters are not electing representatives to a

collegial body. There is considerable doubt as to how much these sorts of systems

help their intended beneficiaries.

III.

Conclusion

Alternatives to the present system of electing judges at-large from numbered

places impose unacceptable burdens on compelling state interests in the

independence and competence of the state judiciary. The balance among these

interests that the states have presently struck is crucial to the effective functioning

of the trial bench. Given the minority's diminished interest in electing its own

representatives in the judicial context, the scales should tip in the Court's analysis

toward a finding of no Section 2 violation as a matter of law in the instant case.

12

Respectfully submitted,

h * .S

SUSAN E. RUSS

Special Assistant Attorney General

MILLER, HAMILTON, SNIDER & ODOM

One Commerce Street

Suite 802

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

(205) 834-5550

vrA ?-• fW j & /

DAVID R. BOYD

Special Assistant Attorney General

(Counsel of Record)

BALCH & BINGHAM

Post Office Box 78

Montgomery, Alabama 36101

(205) 834-6500

J- ( k J U , n r h < . t -

FOURNIER J. GALE, III

Special Assistant Attorney General

MAYNARD, COOPER, FRIERSON & GALE

2400 AmSouth Tower - Harbert Plaza

1901 6th Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 36101

(205) 252-2889

13

S- h w

WALTER S. TURNER

RONALD C. FOREHAND

OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

11 South Union Street, Room 303

Montgomery, Alabama 36130

(205) 242-7300

14

CERTIFICATE

I HEREBY CERTIFY that a copy of the foregoing has been served upon the

following: Jim Mattox, Attorney General of Texas, Mary F. Keller, First Assistant

Attorney General, Renea Hicks, Special Assistant Attorney General, and Javier

Juajardo, Assistant Attorney General, P.O. Box 12548, Capitol Station, Austin,

Texas 78711-2548; William L. Garrett, Garrett, Thompson & Chang, 8300 Douglas,

Suite 800, Dallas, Texas 75225; Rolando Rios, Southwest Voter Registration &

Education Project, 201 N. St. Mary's, Suite 521, San Antonio, Texas 78205;

Sherrilyn A. If ill, NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., 99 Hudson

Street, 16th Floor, New York, New York 10013; GabrielleK. McDonald, 301 Congress

Avenue, Suite 2050, Austin, Texas 78701; Edward B. Cloutmann, III, Mullinax,

Wells, Baab & Cloutman, P . C . , 3301 Elm Street, Dallas, Texas 75226-1637; J. Eugene

Clements, Porter & Clements, 700 Louisiana, Suite 3500, Houston, Texas 77002-2730;

Robert H. Mow, Jr . , Hughes & Luce, 2800 Momentum Place, 1717 Main Street, Dallas,

Texas 75201; John L. Hill, Jr. , Liddell, Sapp, Zivley, Hill & LaBoon, 3300 Texas

Commerce Tower, Houston, Texas 77002; Walter L. Irvin, 5787 South Hampton Road,

Suite 210, Lock Box 122, Dallas, Texas 75232-2255; R; James George, J r . , Graves,

Dougherty, Hearon & Moody, P.O. Box 98, Austin, Texas 78767; Seagal ̂ V.

Wheatley, Oppenheimer, Rosenberg, Kelleher & Whatley, Inc. , 711 Navarro, Sixth

Floor, San Antonio, Texas 78205; and John R. Dunne, Assistant Attorney General,

Jessica Dunsay Silver, Mark L. Gross and Susan D. Carle, Attorneys, Department

of Justice, P.O. Box 66078, Washington, D.C. 20035-6078, by depositing the same

in the United States Mail, postage prepaid, properly addressed.

All parties required to be served have been served.

Montgomery County, Alabama, this the I KK__ day of

O r s h l x ^ __________________________ -» 1991-

c2r>v?'&v-) i

OF COUNSEL

15