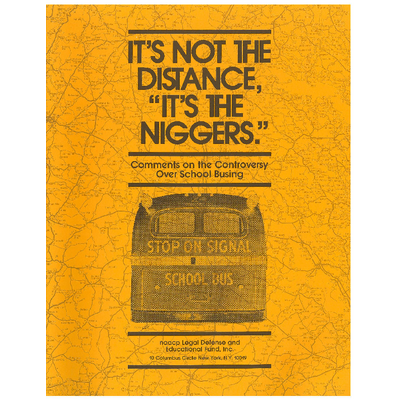

It's Not the Distance - Comments on the Controversy Over School Busing

Reports

May 1, 1972

80 pages

Cite this item

-

Division of Legal Information and Community Service, DLICS Reports. It's Not the Distance - Comments on the Controversy Over School Busing, 1972. a4eeed24-799b-ef11-8a69-6045bdfe0091. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f9f7d893-c88c-414c-b829-0a6ad4a541e7/its-not-the-distance-comments-on-the-controversy-over-school-busing. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

naacp Legal Defense and r

Educational Fund, Inc.

~

RICHMOND'S SCHOOL MERGER

SPAWNS A NEW MELTING POT

Mosby sits atop Church Hill,

a heavily black area in the

city's East End, and Mrs. H.,

a white woman with her grey

hair in green plastic roll

ers says, "I hate her going

to school with them niggers.

They teach everybody in school

nowadays to love one another

and I don't believe in that.

I tell her she's got to go

to school somewhere, but I

hate this busing."

D.A. formerly bused herself

up to predominantly white

Highland Springs Elementary

School in Richmond's North

Side, which was just as far

away as Mosby, but Mrs. H.

says distance isn't the is-

sue: "It's the niggers."

The Washington Post,

January 17, 1972

IT'S NOT lFIE

Dl9'ANCE,

"IT'S lFIE

NIGGERS:'

Comments on the Controversy

Over School Busing

The Division of Legal Information

and Community Service

naacp Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

10 Columbus Circle New York, N.Y. 10019

May 1972

CHAPTER I

I N T R 0 D U C T I 0 N

American children arrive at school via every conceivable

mode of transportation, including horses, snowmobiles, boats and

airplanes. Assuring their arrival on time and safely every day

is big business. A vast transportation system coordinates the

efforts of citizens of all racial and economic groups: trustees,

administrators, patrons and children of public, private and

parochial schools, Indian families on reservations, professionals

who design the often-computerized travel routes, manufacturers,

the suppliers and mechanics who keep the vehicles running, the

safety experts, the 275,000 drivers.1:/

The school bus has now become the business of judges and

politicians. Because judges have declared that the bus is one

among many tools necessary to eliminate racially and illegally

segregated schools, politicians are clamoring for the curtailment

of the power of the judiciary. A serious constitutional crisis

- 2 -

has been precipitated. The Legal Defense Fund is deeply con

cerned about this attack, for it undermines the confidence in the

judiciary which is vital to the effective functioning of our

constitutional system. Having represented black plaintiffs for

over 30 years in most of the nation's school desegregation cases,

LDF lawyers know, perhaps better than any other group of private

citizens, that Federal judges are extremely reluctant to impose

harsh and unreasonable remedies even for clearly unconstitutional

actions.

The proposed moratorium on busing threatens gains which

have been made in the long and painful struggle to fulfill the

constitutional rights of children to equal educational opportunities.

The reopening of school cases would create pandemonium across the

land and undercut the work of those courageous school officials

who have provided professional leadership during the transition

to unitary school systems. These proposals, which would curtail

only one kind of busing - busing to desegregate schools - and

not any other kind of pupil transportatim, barely camouflage their

racist motivation. They signgl the reversal of the momentum

of equal justice which during the 60's ended a century of Con

gressional silence on the legal rights of the nation's racial

minorities.

The politicizing of the busing issue during an election

year is not a mark of leadership. It has polarized our people

- 3 -

It has diverted attention from the urgent need to eradicate ra-

cism. "Instead of cursing the disease (segregation ) ," as Father

Hesbl.rgh has aptly stated, "we curse the medicine, we curse the

doctors."£/ Emotions have been aroused. Wild, unsubstantiated

charges about judges and about busing have been made. They must

be answered. It is not the school bus which is in trouble. What

is at stake is our sanity as a people, the independence and integ-

rity of our courts, the fulfillment of our commitment to equal

justice.

* * * *

our findings demonstrate that the current sentiments

about busing and courts used to justify opposition to further

school desegregation are popularized myths.

* Federal courts have not exceeded Supreme Court

rulings and have not ordered "massive " or "reck

less" busing in order to implement desegregation

plans.

* Increases in busing in some cities have occurred,

but these increases are not always enormous and

sometimes they are due to factors other than de

segregation.

* Busing is not harmful to children. In fact, school

authorities utilize busing to protect young child

ren.

* Transportation for various school purposes is

used to improve the educational program, not to

undermine it.

*

- 4 -

The cost of school busing is minor. It does

not deplete re s ources for better schools.

* * * *

Ev er since Massachusetts enacted the nation's first pupil

transportation law i n 1869, American children hav e been trans-

ported to school under arrangements which hav e been regulated and

subsidized by state authorities. The early horse-drawn vehicles

and the ubiquitous y e llow school bus have bee n symbols of communi-

ties that care for their children . The two major concerns which

have motivated the steady increase in pupil transportation in the

last century have been America's unwillingness to limit a child's

educational opportunities to those a vailable within walking dis-

tance from his home and a concern for his physical safety.

That the school bus is an established institution in

American education which has received tremendous public support

is evident from the following statistics:

* 43.5% of the total public school enrollment

or 18,975,939 pupils are transported to

school daily, acco~ding to HEW statistics.ll

* There has been a steady increase in pupil

transportation, with annual increases in

the last decade of from .5% to 2.5%. The

decades with the largest percentage gains

were: 11.4% from 1939-40 to 1949-504/

9.9% from 1949-50 to 1959-60

* American taxpayers have been willing to

*

- 5 -

invest significant funds in busing. The

National Highway Traffic Safety Administra

tion reports that the total cost including

capital outlay for pupil transportation for

1971-72 is $1.7 billion.2/

256,000 buses are now traveling 2.2 billion

miles.6/

Busing has been motivated not only by a commitment to

further educational, social and humanitarian objectives, but by

school administrators' concern for more efficient utilization of

facilities. The major increases in busing have accompanied the

moves to provide greater educational opportunities by consolidat-

ing rural schools. Urban school districts are increasingly

busing children threatened by traffic hazards, a service which

must usually be provided from local funds because the miles in-

valved do not meet state requirements for reimbursement. Most

states provide for the transportation of handicapped children.

The bus has made it possible for urban school districts

to relieve overcrowded conditions, to use space wherever it is

available in the community, to prevent double sessions and to

reduce class size. The ERIC study reports the St. Louis experience

where "busing was used as an alternative to having double-sessions,

which would have set one set of children free in the morning and

another set in the afternoon. For those transported, the benefits

of the program were obvious, but they were not the only benefi-

ciaries. As a report to the Superintendent of St. Louis Schools

- 6 -

emphasized, 'reduction of class size, through bus transportation

and other expediences ... made it possible for nontransported as

well as transported children residing in the districts of these

seriously overcrowded schools to suffer minimal education loss.' u7 /

Busing has made it possible for school districts to avoid

expensive new school construction and not just because current

available facilities can be used more efficiently. A school

official in Lynchburg stated candidly that the only alternative

to busing in his district would be the building of new schools

in the ghetto - a capital outlay requiring bond issues which he

8/

felt the taxpayers probably would not approve.-

The desire of local school authorities to use the school

bus as a vehicle for enriching the educational program, particu-

l ar ly of disadvantaged children, can be seen in their use of

ESEA Title I funds for this purpose. In 1967-68, $18 million

of Title I money was used nationally for transportation. Sixty

percent of the Title I districts in California and 75% in Massa

chusetts had transportation components.

91

Now that the school bus is the center of public controversy,

it is most unfortunate that there is no longer any public or

private agency which annually collects and reports statistics

on pupil transportation in the U.S. The most current national

figures available are for the 1969-70 school year. These were

- 7 -

reported by the National Association of State Directors of Pupil

Transportation Services, an informal group which has no budget,

office or staff. The U.S. Office of Education collects some

limited information on pupil transportation as part of its larger

biennial survey of educational statistics, but this information is

out of date at the time it is published.

There never has been a national source of data on pupil

transportation by race. Nor are any statistics available nationally

on the numbers of students bused or the number of miles school

buses travel to further various educational objectives, i.e.,

more efficient use of facilities, vocational education, summer

school, field trips and special educational programs.

The current discussion suffers from a lack of uniform,

objective, factual information. In order to collect some informa-

tion from school districts in which desegregation orders have

been implemented in this school year, Legal Defense fund staff

members interviewed local school officials in fifteen districts

which implemented busing plans this year. Four state departments

of education were visited to gather state-wide information on

pupil transportation. In addition, national data and information

were collected from the of=ice of Education and the Office for

Civil Rights in HEW, from the Department of Transportation, the

National Safety Council, the National Education Association, the

National Association of State Directors of Pupil Transportation

- 8 -

Services, and the U.S. Corrunission on civil Rights. Besides

court records, school budgets and monthly transportation reports

were examined.

We trust that our findings from this survey, done between

March 27 and April 17, 1972, will help put busing into its proper

perspective and thus contribute to a rational discussion of i t s

role in fulfilling the constitutional rights of black and brown

children to equal educational opportunities. The quotes whi ch

begin the following chapters are from President Nixon's Message

to Congress on March 17, 1972, the proposed Student Transportation

Moratorium Act of 1972, and the proposed Equal Educational Opportuni

ties Act of 1972, which were submitted by the White House to

Congress.

- 9 -

CHAPTER II

"Many lower court decisions

have gone far beyond .•.

what the Supreme Court said

is necessary .• . •

"Reckless extension of bus

ing requirements . . • .

"Some of the Federal courts

have lately tended toward

extreme remedies .... "

1 . The President's reference is somewhat difficult to

identify, since the Supreme Court said in Swann and Davis (Mobile)

that an adequate desegregation plan would have to achiev e "the

greatest possible degree of actual desegregation consistent with

the practicalities of the situation," and that in measuring the

performance of proposed plans against this goal, there was a

presumption against schools all or virtually all of one race.

It is apparent from a study of district court orders in school

desegregation cases issued after Swann that most lower court

judges have made a conscientious effort to apply these principles

to the systems before them by being willing to consider desegrega-

tion plans requiring proportionately similar amounts of busing

as were approv ed for Charlotte. (Chief Justice Burger's opinion

denying a stay in the Winston-Sal:em case last summer urged caution

in making such comparisons, but the Court eventually declined to

review Winston-Salem on the merits, without any dissent . )

- 10 -

The inunediate impact of Swann was that district judges

insisted upon the incorporation into plans of techniques such as

non-contiguous zoning and pairing, which many had refused to re

quire prior to the Supreme Court's ruling. However, many courts

rejected unusually long bus rides by applying the Swann standards.

In Jacksonville, Fla., the court declined to order busing to the

North Beach schools in the system , finding that the trip would

take one-and-one-half hours each way. And in Nashville, Tenn.,

the court accepted an HEW-drawn plan which the government's experts

said was deliberately designed not to desegregate some schools in

outlying Davidson County areas because of the length of the bus

rides.

2. It is undoubtedly the concern about metropolitan reme

dies to school segregation which the President refers to in his

comment on "extreme remedies." U.S. District Court Judge Merhige

ordered the consolidation of the Richmond, Va., city schools with

the school districts of the surrounding counties of Henrico and

Chesterfield. The Court found that to accomplish the consolida

tion, 78,000 of the 104,000 students in the new system would have

to be transported, about 10,000 more than those in the three

jurisdictions who are now bused. The Court further found that

no additional buses would be necessary and that busing times and

distances would not exceed those already required of the students

- 11 -

10/ in those counties for many years.~

3. In defense of district judges, one must point out

that some comprehensive school integration plans have been initi-

ated by local school boards and have not been compelled by district

courts under a mandate from Swann. The Winston-Salem-Forsyth

County case was on appeal at the time of the Swann decision. The

Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals remanded the case to the district

judge who ordered the school board to prepare a plan which he

subsequently approved and which is currently in effect. The board

subsequently objected to its own plan and has sought to amend it.

The Columbus-Muscogee County, Ga . , school board developed

on its own initiative a comprehensive and complicated racial balance

plan under which much of the busing is done by the children of

military personnel in the area. The court approved it and the

black plaintiffs were pleased to support a plan which had been

locally initiated.

Federal District Judge James B. McMillan entered a find-

ing in the Swann case in October, 1971 that the "feeder plan"

which the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school board had adopted would

require the transportation of 46 , 667 students , while the "Finger

plan", which the school board rejected after it had been approved

11/

by the U.S. Supreme Court, called for transporting 39,080.~

- 12 -

CHAPTER III

"Some (court orders) have

required that pupils be

bused long distances, at

great inconvenience .... "

1. Our investigations do not support the conclusion that

large numbers of children are being bused long distances to im-

plement desegregation plans. There are individual instances of

long rides, but we suspect that these are far fewer than when

schools were segregated. Speaking in Congress on February 28,

1970, Senator Walter Mondale mentioned counties in Georgia and

Mississippi which bused black children 75 miles and 90 miles

respectively to all-black schools . ..!£/

Judicial notice has been taken of the length of bus rides

prior to desegregation. Judge McMillan observed that an analysis

of principals' reports filed in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

had revealed that:

"The average one way bus trip is one hour and

fourteen minutes;

"80% of the buses require more than one hour for

a one way trip;

"75% of1~~e buses make two or more trips each

day .... -

The Honorable Stephen Horn, vice-chairman of the United

States Commission on Civil Rights, testified recently before

Congress:

- 13 -

... before the Charlotte-Mecklenburg decision,

pupils averaged over an hour on the bus. When

the desegregation plan was carried out, however,

bus trips were cut to a maximum of 35 minutes.

Similarly, the Richmond decision would call for

average bus rides of about 30 minutes, which is

less than the current average in an adjacent dis

trict involved in the decision. Where pupils

are bused for the first time, trips are rarely

long. The average travel time reported seems to

be 20-30 minutes. Trips of an hour or more would

be out of the ordinary. A trip of a half hour

or so would not bring the pupil home much later

than if he walked from a neighborhood schoo1.14/

2. In recent testimony before a Congressional committee,

Elliot Richardson, Secretary of the Department of Health, Education

and Welfare, referred to an 80-minute, one-way bus trip in Winston-

Salem, N.C. Prior to the recent court order, there were at least

five bus trips which were 80 minutes or over, one of which was

120 minutes long. Three out of the five schools involved were

overwhelmingly white and had hardly felt the impact of integra-

t

. 15/

ion.~ It is difficult to evaluate how much children are in-

convenienced by these long trips because the mileage reports do

not show how long each child is actually riding. The mileage

begins when the bus leaves the driver's home and ends when he

parks his bus. Children riding varying periods of time have

boarded and left the bus in the meantime.

3. A long bus ride or an inconveniently early departure

time from home does not necessarily reflect a long distance.

Sometimes children must leave home early or travel circuitous

- 14 -

routes because local authorities refuse to provide enough buses.

When it was clear that the court-ordered integration plan for

metropolitan Nashville-Davidson County, Tenn. would increase

the number of bused students from 34,000 to 49,000, Superintendent

Elbert Brooks sought funds from the Metropolitan Council for the

purchase of buses. The Council refused to appropriate these funds,

so the district had to rely on its existing fleet supplemented

only by 18 new buses which had been bought prior to the de

segregation order.

161

According to school officials interviewed

by a Tennessee reporter, the shortage of buses has resulted in

inconvenience and hardships for students:

•.. with buses having to run more than one

route, many children must stand in the dark

to catch buses near their homes in the morn

ing, while others who go to school later get

home after dark .... Some children ride up to

14 mil es in the morning and afternoon , spend

ing up to an hour on the vehicles twice a

day.11./

4. We are indeed concerned about the inconveniences which

children experience, especially when black pupils are expected to

carry a disproportionately heavy share of the busing. In Pinellas

County, Fla., 6.4% of the white students are bused because of the

desegregation order in comparison to 75.2% of the black children. 181

(Sixteen percent of the student population is black.) An official

in Hillsborough County, Fla., reports that of the elementary pupils

transported because of the court order, 8,576 are black and 5,404

- 15 -

19/ .

are white.~ Seventy-five percent of the bused students in

Jackson, Miss., are black.

201

Furthermore, black children are

often bused at an earlier age. When schools are paired or clustered,

it is not unusual for the plan to require black pupils to leave

their neighborhoods for the early elementary grades. The formerly

all-black schools receive the older elementary children, or may

become sixth-grade centers or junior highs for both races - an

arrangement which requires black children to travel in the earliest

years.

5. It is the lack of transportation which is often the

hardship. Local and Federal officials who refuse to provide

transportation to pupils who must travel long distances to school

and archaic state laws which discriminate against cities in their

transportation reimbursements are responsible for inconveniences

to children. Hattiesburg, Miss. and Texarkana, Ark. have plans

which require junior high pupils to travel long distances at their

own expense. Some states do not provide reimbursement for busing

within cities. (See the discussion of Sparrow v. Gill in Chapter

I V.)

The lack of transportation in Norfolk, Va. is a real hard-

ship to students who must pay $63 a year to ride city buses to

school because the district does not operate its own transportation

system. Several hundred students from poor families in Norfolk

~ 16 -

are not in school this year because they do not have transporta-

21/

tion.--

Most of the school districts mentioned in this report have

sought Federal funds for transportation from the Emergency School

Assistance Program (ESAP). Federal officials rejected the request

from Greenville, Miss. for funds to purchase buses to transport

2,000 students who had been reassigned to elementary schools out

. . 22/

of their neighborhoods.--

In 1970-71, Duval County, Fla. received a grant from ESAP

of which over $100,000 was used for pupil transportation. The

district applied for another grant for 1971-72 and requested

several hundred thousand dollars for transportation. The total

application was approved but not the use of the funds for busing .

Accordingly, the school board put over $900,000 of the grant in

escrow and filed suit in Federal court to compel Secretary Richardson

23/

to authorize the use of this money for transportation.--

- 17 -

CHAPTER IV

"Massive Busing"

1. We find no conclusive evidence that the aggregate

amount of busing has increased nationally or regionally as a re-

sult of court-ordered integration. In the absence of data on

pupil transportation by race which would reveal how many white

and black children are being bused to what kinds of schools, it

is impossible to state accurately the number or race of pupils

who are being bused to racially segregated or integrated schools.

The cry of "massive busing" for "forced integration" is completely

irresponsible.

We agree with Donald E. Morrison in his testimony on be-

half of the National Education Association before the House

Committee on the Judiciary: "There is no statistical proof that

desegregation has substantially increased pupil busing, either

24/

nationally or regionally."-

2. HEW has estimated a 3% increase in busing as a result

25/

of integration.- This figure represents the increase in the

Southeastern states in overall pupil transportation between 1967-70

from 52.5% to 55.5%. Our investigation leads us to the conclusion

that this is no more than normal growth. The Southeast has been

subsidizing the transportation of more than 50% of its pupils

since 1957, a larger proportion than any other region. Between

- 18 -

1965 (when HEW's Title VI civil rights enforcement program began)

and 1970, there was a 4% increase in the numbers of pupils trans-

ported in the South. Yet at the same time the percentage of

pupils increased at a more rapid rate in other parts of the nation

. . d f . . 26/ where there were few court orders and limite en orcement activity.~

Nationally 4.9%

North Atlantic 4.9%

Great Lakes 5 .2%

3 .

. 27/ .

The Department of Transportation~ estimates that

the annual increase is attributable to the following causes:

Population growth 95%

Centralization about 3%

Safety less than 1%

Desegregation less than 1%

Other less than 1%

4. Urban school districts which have only bused minimally

or not at all in the past experience a major upsurge when a com-

prehensive plan to eliminate the dual school system is implemented.

Often, however, this does not bring the district up to the state

average. All of the schools in Raleigh, N.C., were effectively

desegregated in 1971-72 under a plan which contributed to the

increase of bused students from 1,342 to 10,126, at least 5,000

of which were Sparrow students. Although the district is now

- 19 -

transporting 46 . 5% of its students, this is less than the North

Carolina state a v erage of 64.9%

281

In Norfolk, Va., where the desegregation order required

most elementary students to travel outside their neighborhoods for

the first time in 1971-72, approx imately 39% of the district's en-

rollment is bused. Yet 63% of all public school students in

29/

Virginia are bused.~·

5. An increase in busing may result from factors which

have nothing to do with integration:

a. There has been an increased use of busing

to protect children from traffic hazards.

In 1971-72, 66,115 students in Florida are

bused at local expense because they do not

meet the 2-mile state reimbursement require-

ment. This is a dramatic increase from 1968-69

when only 40,792 in this category were bused.

Officials report that the main reason is

safety, a concern about busy streets and haz-

ardous walking conditions. The vast majority

of these are elementary pupils . 301

b. Busing is increasing through commitments to

transport younger children. School officials

in Roanoke, Va. took advantage of their new

- 20 -

school buses to provide rides in hazardous

areas for kindergarten children who ordinarily

lk h 1

311 . . . 1973 74 wa to sc oo .-- Beginning in - ,

Florida law will mandate state-supported

kindergartens. All districts will be re-

. d 'd . 32/ quire to provi e transportation.-- Orange

County, Fla. expects to bus 4,000 kinder-

33/

garten pupils that first year.--

c. At the time of desegregation, some school

districts use their newly acquired buses

to further other objectives. Lynchburg, Va .

is transporting students for the first time

this year. The school system's 37 new buses

not only get students to school, they are also

used to provide field trips and to facilitate

string music, choir practice and R.O.T.C.

in high school.

d. The decision of a three-judge Federal Court

34/

in North Carolina in Sparrow v . Gill-- has

increased busing and complicates the effort

to determine the impact of integration on

busing. Prior to the 1970-71 school year,

North Carolina law generally provided that

- 21 -

county children who lived more than a mile

and a half from school would be provided

school bus transportation paid for by the

state. City children, however, living a

mile and a half from school were not pro

vided school bus transportation at state

expense. City children were defined as

those children who lived within the 1957

boundaries of a city. Therefore, those

children who lived in areas of a city which

had been annexed after 1957 and lived more

than one and a half miles from school did

receive bus transportation at state expense.

Additionally, the law was interpreted to

mean that if a school was located outside

of the 1957 limits, then children living

within the 1957 limits more than a mile and

and half from the school were eligible for

transportation. Thus, prior to the 1970-71

school year there was at least some school

bus transportation provided for city children.

Moreover, local boards of education were free

to provide bus transportation at local expense

- 22 -

if they chose to do so. Greensboro, for

instance, has for many years provided trans-

portation for children living more than a

mile and a half from school and has paid

for it out of local funds.

A lawsuit was filed by white children and

their parents in Winston-Salem challenging

the inequity which existed where city children

living more than a mile and a half from school

did not receive bus transportation but county

children living more than a mile and a half

from school did. A three-judge Federal Court

decided that classifying city children differ-

ently from county children in determining who

was to receive bus transportation at public

expense was constitutional. However, the

Court determined that it was unconstitutional

to treat children who lived in the areas of a

-

city prior to 1957 differently from children

who lived in areas of a city annexed after

1957.

The result of the Sparrow decision was that

the State Board of Education required local

- 23 -

school boards to offer transportation to

all city children or to none. If local dis

tricts decided to offer transportation to all

city children living more than a mile and a

half from school, then the state would pro

vide the money for the increased transporta

tion. This new policy went into effect for

the 1970-71 school year. Almost all cities

chose to increase their transportation to in

clude city children. Raleigh was the notable

exception. It began to transport Sparrow

pupils in 1971-72.

The comparison of transportation data before

and after desegregation is complicated by the

effects of the Sparrow decision because de

segregation was beginning to occur in North

Carolina cities at the same time that state

financed transportation was being offered for

the first time for city students. All of the

cities were surveyed by the State Department of

Public Instruction prior to the 1970-71 school

year to determine how many additional children

would be riding school buses to be paid for by

- 24 -

the state. The survey revealed that an

additional 54,000 students, requiring 549

buses, would become eligible throughout the

state as a result of Sparrow. Included in

this figure were 1,900 students (21 buses)

in Asheville, 3,108 pupils (34 buses) in

Winston-Salem-Forsyth County, 6,122 pupils

(68 buses) in Charlotte-Mecklenburg, 2,281

students (25 buses) in Greensboro and 3,801

d (4 ) 1 . h 35/ stu ents 2 buses in Ra eig .~

Therefore, to calculate the extent of in-

creased transportation occasioned by desegre-

gation requirements, it is necessary to sub-

tract the number of children bused in the year

prior to desegregation from the number of child-

ren bused after desegregation and then subtract

the number of additional city children who

would have received transportation under the

new state policy. The resulting figure should

also be discounted further by such factors as

normally expected growth, increases for special

education, and pre-school education, etc .

6. Whether integration brings an overall increase in

busing is difficult to assess . One might expect the implementation

- 25 -

of a busing plan to result in an increase in both the number of

students bused and the mileage . Actually:

*

*

*

*

*

36/

Arlington, Va., buses 1,000 fewer pupils.~

Pinellas County, Fla., buses about the same

number of students but the buses travel 3,200

. . 37/

more miles daily.~

Duval County, Fla . , has increased the number

of pupils bused but there has been a substantial

decrease (11 miles or 20%) in the average num-

38/

ber of miles per day per bus.~

Busing to desegregate in Alabama, according

to the United States Commission on Civil Rights,

has resulted in 1 million fewer passenger miles

h h

. . 39/ tan t e previous year under segregation. · ~

From 1965-66 to 1970-71, the number of pupils

transported in Mississippi has decreased from

40/

312,085 to 292,472.~

- 26 -

CHAPTER V

"Rather than require the spend-

ing of scarce resources on ever

longer bus rides •.. , we should ...

[put] those resources directly in

to education .•••

"Implementation of desegregation

plans will in many cases require

local educational agencies to

expend large amounts of funds for

transportation equipment, which

may be utilized only temporarily,

•.. thus diverting those funds

from improvements in educational

facilities and instruction which

otherwise would be provided."

1. The cost argument against pupil transportation rests

on the assumption that busing costs are so great that they seriously

deplete funds for the regular educational program. But the facts

do not support this assumption. The latest national figures

available show that 3.7% of all educational expenditures in the

United States were spent on pupil transportation of all kinds.

This percentage has declined slightly since the 1953-54 school

year, as the attached table on busing costs 1953-54 through

1967-68 shows. The chart on pupil transportation costs for

individual school districts reveals that even with increased

costs, pupil transportation remains a small percentage of all

educational expenditures.

2. The broad allegations of the cost burden must also

- 27 -

reviewed against the fact that each state reimburses local

school districts for both capital and operating costs. There

are wide variations among states in their patterns of reimburse-

ment, and there is no national average of state reimbursement

of pupil transportation costs. In Florida in the 1970-71 school

year, $11.2 million of the total transportation expenses of more

than $23 million for all school districts were reimbursed by

41/

the state.~

In North Carolina, the state pays a vast majority of all

pupil transportation costs incurred by local school jurisdictions.

For example, the state pays the cost of operating all school buses

which transport students eligible for state reimbursement. It

pays for replacing all school buses. If a local district chooses

to contract with a private company, the state pays the company

even if its charges are higher than the average level of state

reimbursement. The main financial burden for local school dis-

tricts is limited to (1) the initial purchase of the bus , (2)

maintenance and upkeep of facilities, (3) some administrative

costs, and (4) the cost of busing pupils who are not eligible for

42/

state reimbursement.~

3. Cities which have never subsidized busing before de-

segregation claim a terrible financial burden when ordered to

desegregate, yet sometimes the wild projections of costs have

- 28 -

been completely misleading . In the spring of 1971 shortly after

the court ordered desegregation in Pinellas County, Fla., a

local school official was quoted as saying that the order would

require the busing of an additional 11,000 students. In fact,

about 1,700 additional students were transported to comply with

the court order. In Pinellas County, Fla., approximately 2,000

white children left the school system and the district ceased

transporting 1,413 students who were ineligible for busing be-

cause they lived within walking distance of their school. Even

if these 3,413 were transported in addition to the 1,700 who were

bused for desegregation purposes, still less than half of the

43 /

projected 11,000 students would have had to be transported.~

The Raleigh, N.C. school district projected that in order

to comply with its desegregation order, it would have to spend

$980 , 956 from local funds for the 1971-72 school year. Of this

amount, $828,000 was for 138 new buses and $26,500 was for drivers'

44/

salaries.~ The $26,500 represents a local supplement in excess

of state reimbursement for drivers' salaries. In fact, the total

local expenditures required to meet the court order were $643,054 ,

and of that sum, cbout $444,993 represented the cost of buses which

45/

were not delivered in the 1971-72 school year.~

4. The major cost of desegregation is the initial capital

outlay for new buses. This cost can be handled by school authori-

- 29 -

ties in several ways. If the money is spent all in one year,

it represents assets that are carried over a number of years.

However, if the district borrows money for new buses, the actual

cost is carried over the duration of the loan and does not con-

stitute a one-time expense.

School officials in some districts have publicly claimed

enormous expenditures for new buses. While this may sometimes

be true, it may also be that some of the buses were alreadybudg-

eted, that some buses are needed for non-desegregation purposes,

or that some buses paid for in one year are not delivered until

the following year.

5. In some instances, the number of students bused may

vary depending on the management practices in various school dis-

tricts. A Hillsborough County, Fla. school official conunented to

an LDF staff member that his school district transported 10,000

more children with 100 fewer. buses than the Charlotte-Mecklenburg,

. 46/

N.C. district did.--

6. The Norfolk, Va. public schools had not subsidized

bus transportation prior to desegregation. When the school dis-

trict was ordered to desegregate its schools, the school board

and the city council refused to purchase buses to get children

to their assigned schools. The 15,000 children who ride a bus

to get to school must pay $63 per student per year, a financial

- 30 -

burden which families have had to bear. Yet, if Norfolk operated

its own bus fleet, it would cost less than half that much, or

47/

$26.17 (the Virginia cost per pupil for cities),- to trans-

port students. Furthermore, if Norfolk were to operate its own

buses, it would be eligible for 47% of its operating costs from

48/

the state.-

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit on

March 7, 1972, ordered the Norfolk school board to provide free

transportation as a part of its desegregation plan on the grounds

that without transportation to the assigned school, the whole

desegregation plan is a "futile gesture" and a "cruel hoax."

The Court recognized that the cost of transportation would be

a burden, but held that $3 million capital outlay for buses and

maintenance could be amortized over the normal· life of the equip-

ment and that the $600,000 increase in annual operating costs

was reasonable in a district with a total school budget of $35

49/

million.-

7. The decision of this Administration to prohibit the

use of ESAP funds for any transportation costs created severe

problems in a number of school districts. Dr. Elbert Brooks

testified before Congress that at a meeting with southern school

superintendents in Atlanta in July, 1971, he and other superinten-

dents were led to believe by HEW officials that their requests

- 31 -

for help to pay busing costs would be honored by HEW. But in

August, after President Nixon's announcement, HEW refused to

fund any of the requests . .1Q/ Dr. Brooks, as well as other

southern school superintendents, felt betrayed.

8. In other cases, it was not only the President, but

also local municipal authorities who prohibited the use of public

funds to buy school buses to meet the requirements of the court's

order. The Nashville Metropolitan Council refused to approve

new buses for desegregation, and as a result schools are operat-

ing on staggered hours, some extra curricular activities have

been curtailed and students and parents have been inconvenienced.

Despite all these problems, Dr. Brooks reported that "the regular

program should not be hurt • .. W

9. In some instances, school districts may spend extra

money for transportation in order to provide conveniences for

students. North Carolina only reimburses local districts for

"mixed" buses, i.e., buses which carry elementary, junior and

senior high school students at the same time. Winston-Salem-

For$yth County, however, has had a practice for several years

of taking elementary students home in the afternoon before junior

and senior high schools are let out for the day. Thus, the local

board must pay for the costs of transporting these elementary

52/

students from local funds.~

- 32 -

10. Some districts pay busing costs out of local funds

because they undertake supplementary costs which are not state

reimbursed. For example, in 1971-72 Winston-Salem-Forsyth County

dJcided to hire adult bus drivers for the first time. They pay

each adult driver $80 a month more than state reimbursement. The

district projected in September that it would cost them about

53/

$150,000 this year for this driver-salary supplement.~

11. Inflation has caused increases in busing costs. In

North Carolina, for example, state reimbursement for bus driver

salaries has gone up considerably in the past few years after bus

drivers came under the minimum wage laws. Salaries for mechanics

have shown a sharp upward trend recently in North Carolina, as have

54/

the costs of parts and gas.~

12. Two North Carolina school systems - Greensboro and

Asheville - desegregated their schools at no additional expense to

local districts. In Greensboro, the additional busing of 6,000

students in 1971-72 was accomplished by the city's existing fleet,

by county buses already utilized by the city to transport some

city children, and by the borrowing of 86 buses owned by the

county and maintained by the state. In Asheville, no local money

was spent to bus over 2,000 children to accomplish desegregation

because all transportation is done by private bus companies which

55/

are reimbursed by the state.~

I

ii

- 33 -

CHAPTER VI

"Curb busing while expanding

educational opportunity"

1. School officials see busing and expanding educational

opportunities as complementary and not contradictory objectives.

Their views are directly contrary to those of the President who

sees busing as a "symbol of social engineering on the basis of

. 56/ abstractions."- School districts throughout the country use

their transportation systems to promote a variety of educational

and social goals including school consolidation, improved voca-

tional education programs, broadened horizons for their children

through field trips, and expanded summer programs and pre-school

education. No one, to our knowledge, has ever held out these

objectives as "social engineering."

As Donald E. Morrison of NEA has testified:

School systems have not hesitated to bus child

ren to vocational education programs and special

education programs concentrated in particular

geographical areas. School children are regu

larly bused on field trips serving some educa

tional purpose. In some school districts, such

as Cleveland's Shaker Heights, children have

been bused~e for lunch to give teachers duty

free time. 5

2. Educators have supported school busing to promote edu-

cational opportunity. The Council of Chief State School Officers

in November 1971, stated:

Although transportation of students as a method

of achieving desegregation has become a highly

- 34 -

controversial issue throughout the nation, the

members of the Council of Chief State School

Officers believe it is a viable means of achiev

ing equal educational opportunity and should be

supported. 58/

3. Transportation is still a relatively modest percent-

age of all educational expenditures. (See discussion in Chapter

V.) Even if the nation were to re-allocate for compensatory

education all funds currently allocated to pupil transportation,

including those which subsidize affluent, middle-class children

attending suburban schools which have never been involved in

integration, we would have little more than is currently in the

budget for Title I. This program has yet to prove its effective-

ness in raising the levels of academic achievement of educationally

disadvantaged children.

4. The effect of transportation for desegregation on the

regular education program has varied from district to district.

In Pinellas County , Fla. desegregation resulted in a decrease in

extra-curricular activities but not an increase in the number of

pupils bused. 591 But in Roanoke, Va. school authorities report

that because of the new buses required for the desegregation plan,

the district can now "do more in a central location than could

formerly be done in separate places." Roanoke operates five

educational centers for elementary school children, including an

oceanography center and a Japanese garden exhibiting the culture

of the Far East. Students are bused to these centers as part

.,

J

1

- 35 -

of their regular program. The cost of duplicating such centers

in each elementary school would prohibit the use of such educa-

. . . 60/ tional innovations.~

Finally, Lynchburg, Va. school authorities report a 3.5%

increase in school attendance this year over last year. This

is the first year that the city has transported students to school,

and officials say the only factor to which they can attribute

improved attendance is busing.

I.

- 36 -

CHAPTER VII

"The school bus ... has become

a symbol of helplessness,

frustration and outrage - of

a wrenching of children away

from their families ..•• "

1. If this sentiment represented the prevailing attitude,

school systems and local taxpayers would long ago have stopped

busing. Many southern school districts have bused 70-100% of

61/

their students for years prior to desegregation.-

Many school officials are obviously proud of their buses

and pleased with the advantages which busing has brought. When

interviewed by our representative, a Roanoke, Va. official ob-

served that busing has me ant "be tte r control, better schedules,

and h . k ' d ,,62 / appier 1 s. -

Of the students who were bused prior to desegregation,

98% in Winston-Salem-Forsyth County, N.C. and over 90% in Greensboro,

. 63/

N.C. were white.- Did the citizens of those communities see the

school bus as an outrage? We doubt it.

2 . A Hillsborough County, Fla. school official, noting

apparently for the first time that the complete desegregation of

the school system might require a one percent increase in total

expenditures , mused aloud that, "maybe it isn't so bad after all;

maybe it is really worthwhile! 1164/

3. It is true that reports of problems with discipline

- 37 -

and with vandalism involving buses have increased. Whether this

is a concomitant to integration is a mixed picture. Some incidents

have involved persons of the same race. Tensions which occurred

on newly integrated buses have sometimes subsided. Some problems

seem to be the result of having young, inexperienced and untrained

drivers, many of whom are students themselves. Where districts

have employed drivers of a different race from the majority of

pupils, especially white drivers for all-black busloads, they have

invited trouble.

As the bus has become politicized, it has become the

symbol of racial divisiveness. Buses have been turned over and

burned by irate white parents. White hostility against integra

tion has been directed against the bus. However, some officials

whom we interviewed believe that the current problems have little

to do with race. They are convinced that parents lack confidence

in public schools, that the bus as a symbol of the educational

establishment is an easy target, and that those who commit acts of

vandalism are merely reflecting the prevailing disenchantment with

public education.

In view of this problem, citizens have urged the employ

ment of monitors and the training of bus drivers. Norfolk, Va.

sought ESAP funds for monitors and was turned down by HEW officials

who referred to President Nixon's veto of the use of ESAP funds

- 38 -

for any purposes related to transportation. As a direct conse

quence of the President's decision, the Norfolk school board

decided to use city police on the buses for the first month of

school.

,-

- 39 -

CHAPTER VIII

"Excessive transportation of

students creates serious risks

to their health and safety ....

"The risks and harms created by

excessive transportation are

particularly great for children

enrolled in the first six grades."

1. One of the most emotional appeals against busing is

that riding a school bus risks the health and safety of children,

especially those in the first six grades of school. National

safety statistics refute this contention.

Data on student accident rates from the National Safety

Council reveal that it is safer to ride a bus to school than to

walk. The accident rate for boys riding a school bus is .03 per

100,000 student days compared with .09 for walking. For girl

students the accident rate is similar - .03 when riding a bus

66/

and .07 when walking to school.~ These rates for the 1968-69

school year are based on the reports of more than 35,000 school

jurisdiction accidents, that is all types of accidents during a

school day. The National Safety Council warns that since report-

ing is voluntary, the figures may not be representative of the

national accident picture. But the figures do show that of

school accidents reported, risks to student safety on a bus were

much lower than risks to students in other school activities,

such as sports and classroom instruction.

NATIONAL SAFETY COUNCIL, ACCIDENT FACTS, 90-91, (1971 EDITIONo)

Boys - Student Accident Rates by School Grade_!_/

Location and Type Total K.gn. 1-3 Gr. 4-6 Gr. 7-9 Gr. 10-12 Gr.

Going to and from school (MV) .19 .40 .22 .13 .20 .15

School bus .03 .04 .02 .02 • 06 .02

Public carrier (incl. bus) .01 .02 .01 .01 .01 .02

Motor scooter .01 0 0 * .02 .02

Other mot. veh.-pedestrian .09 .33 .16 .08 .04 .02

Other mot. veh.-bicycle .02 0 .02 .02 003 *

Other mot. veh.-other type .03 0 .01 .01 .04 .06

Girls - Student Accident Rates by School Grade_!_/

Going to and from school (MV) .14 .29 .13 .08 .14 .19

School bus .03 .01 .01 .03 .04 .02

Public carrier (incl. bus) .01 .02 0 * .01 .02

Motor scooter .01 .01 * * .01 .02

other mot. veh.-pedestrian .07 .23 .10 .04 .06 .04

other mot. veh.-bicycle * 0 .01 * .01 0

Other mot. veh.-other type .03 .01 .01 .01 002 .10

_!/ The figures in the tables are rates which show the number of accidents per

100,000 student days.

*Less than 0.005

- 40 -

Days Lost

per Inj.

3.56

1.24

3.57

2.42

4.53

3.34

3.01

8.26

2.01

4.31

1.83

14.14

4.50

1.95

- 41 -

The risks to health and safety are presumed b y the

President to be even greater for younger children , those in

the first six grades. This unsupported assumption has risen to

the status of a "finding" set forth in the President ' s legisla-

tion establishing national standards for equal educational oppor-

tunity, yet the chart on the previous page demonstrates that

accident rates on school buses for boys and girls in grades 1

through 6 are slightly ·lower than the total accident rate for

all ages for both sexes.

2. Any discussion of safety must recognize that without

adequate vehicles to transport children to school, students may

be subjected to unwarranted hazards. Dr . Elbert Brooks, the

Director of the Nashville Metropolitan schools , testified before

the Senate Select Committee on Equal Educational Opportunity that

because the school board had been unable to purchase the necessary

number of buses some children left home and returned home in the

darkness of winter days and that some buses made trips on an

inter-state highway to shorten the trip . Dr . Brooks felt that

such practices did create risks , but that such risks were directly

due to the fact that both the Nashville City Council and the

President of the United States had made it impossible for the

school board to purchase enough buses to eliminate these potential

67/

hazards . -

- 42 -

3. School officials are not unmindful of potential risks

to children who walk to the nearest school, but who must cross

busy streets, walk down roads with no sidewalks, and traverse

railroad tracks in order to get to their neighborhood school.

In such instances, local school systems often provide transporta-

tion for these students even though they would not otherwise be

eligible for busing. For example, Roanoke, Va. this school year

purchased 20 new yellow school buses in order to comply with

their desegregation order. These were the first large passenger

buses to be operated by the district itself. The new vehicles

permitted the school system not only to bus children to desegrega-

gated schools, but also to bus kindergarten children who last

68/

year had to walk unsafe streets to get to class.~

4. In the state of Florida during this school year, 66,115

children who are ineligible for state-reimbursed transportation

because they live within walking distance of their school, are

nonetheless bused to school. School officials report that this bus-

ing was done at local expense, that it was done mostly for safety

reasons, and that the vast majority of these children are in the

elementary grades.

69/

The following chart ~ shows, for five Florida school

districts, the number of students who were ineligible for state-

reimbursed transportation but who were bused primarily for reasons

- 43 -

of safety or convenience. Again, the majority of these child

ren are in the elementary grades.

District 1968-69 1969-70 1970-71 1971-72

Duval 3,397 3 I 030 3,630 5,764

Hillsborough 1,879 3,211 5,408 3,565

Pinellas 2,701 3I194 2 I 142 729

Manatee 613 504 748 822

Orange 3,767 4,635 6,347 7,834

Apparently, it is the judgment of local educational officials

that busing elementary school students is not a risk to their

health or safety. Indeed, such busing is deemed a protection of

young children.

I,

I!

I

- 44 -

CHAPTER IX

"A remedy for the historic evil

of racial discrimination has

often created a new evil of dis

rupting communities and impos

ing hardships on children .... "

Who has disrupted communities, imposed hardships, and torn

us apart as a people?

It is not the Federal judges who have exercised judicial

restraint.

It is not black citizens who are still trying to secure

equal educational opportunities for their children.

It is not the school bus.

It is the present Administration which has used the powe r

and majesty and authority of the President's office to stir

dissension, confusion, and uncertainty among us by politicizing

the busing issue.

HILLSBOROUGH COUNTY, FLORIDA - A PROFILE

Florida is a state of metropolitan school districts.

Every city in Florida, no matter how large, is part of the county

school system in which it is located. cities like Miami and

Jacksonville are located in county school systems which also have

rural areas, many municipalities, and burgeoning suburbs. In

spite of the state's size and population, it has only 67 school

districts.

Hillsborough County, which includes Tampa, is a sprawling

metropolitan area, composed of diverse racial and ethnic groups.

About 20% of its 500,000 citizens are black and nearly 20% are

Spanish-speaking. Within its l,034 square miles are some fourteen

municipalities which range in population from 5,500 to almost

40,000. There are also many unincorporated, but heavily populated

areas in this county. Like many metropolitan areas in Florida,

significant population growth has occurred in the county, but

little of that growth has occurred in Tampa itself. The county

has experienced an increase in population from 398,000 in 1960

to nearly 500,000 in 1970, while the Tampa population during that

same period grew from 275,000 to 278,000 persons.

Hillsborough County also has a very large, metropolitan

- l -

school system with about 103,000 students (about 20% black)

attending 129 schools. During the 1969-70 school year, the

dual system was still intact. Freedom of choice had produced

only some token desegregation in a few formerly white schools.

In 1970-71, many other formerly white schools became desegregated

for the first time as a result of a Federal Court order.

In the spring of 1971, black plaintiffs filed a Swann

motion with the U. S. District Court asking that the Hillsborough

County schools be desegregated. Accordingly, the Court directed

the board to devise an appropriate school desegregation plan.

The plan adopted by the board and approved by the Court called

for each school in the system to be about 80% white and 20% black.

The plan, which had the approval of the superintendent, the school

board, the Chamber of Commerce, civic groups and the press, was

a combination of pairing, clustering and non-contiguous zoning.

The clusters were composed of one formerly black school and a few

formerly white schools, with the black schools becoming middle

grade centers and the white schools serving grades 1-5. Thus,

white students now attend formerly black schools in grades 6-7

only, while black students attend formerly white schools for 10

of their 12 school years.

Some resistance to this plan existed prior to the opening

of the current school year. A significant portion of the resistance

- ii -

was in the black community. There were threats of demonstrations

by blacks at the two formerly black high schools. The Court-

ordered Bi-Racial Advisory Committee, which reflected the senti-

ment in the black community, told the Court that the plan "essen

tially establishes a 'community school concept' for white students ....

The plan's undue effort to minimize white flight serves to maxi-

mize black busing." The elimination of the two black high schools,

the Advisory Committee said, " .•. deals a punitive blow to the

black community and by so doing .•. is inconsistent with the short

or long range harmony between the races desired and needed to

implement school desegregation in the community at large." Some

white citizens attempted to thwart the Court's order, but no

major organizations opposed the plan or caused disruptions in

the schools.

In 1969-70, 164 buses were bused to transport more than

27,600 students over 15,200 miles daily. In 1970-71, 179 buses

transported some 32,400 students more than 15,700 miles, an in

crease of about 5,000 students.

Just before the Court approved the current desegregation

plan last summer, the board projected that the proposed plan

would require the additional transportation of about 15,700 ele

mentary, 7,400 junior high and 2,200 senior high school students,

a total of 25,300. The projection was close~ 25,200 students

- iii -

are bused this year for the purpose of desegregation. However,

1,800 fewer elementary students are bused than projected. Of

the 14,000 elementary pupils who are bused, 8,600 are black and

5,400 are white. The total number of secondary students of

both races who are bused is 11,300: 8,500 in junior and almost

2,800 in senior high schools.

Transportation statistics for the 1971-72 school year in

Hillsborough County reflect the increased busing necessary to

implement the desegregation plan.

1. The number of buses used increased from 179

to 339, including 29 spares.

2. There are 907 separate bus trips daily this

year compared with 461 last year.

3. Students were transported to 84 schools last

year and 126 this year.

4. The number of elementary students bused in-

creased from 10,600 to 22,500; junior high

school students increased from 8,800 to

.

16,200~ and senior high school students

from 7,500 to 10,400.

5. Buses traveled 6,000 more "essential miles"*

this year.

* "Essential mile" is a state department term meaning the

number of miles a bus travels with one or more students.

- iv -

6. Total mileage has increased from 15,750 per

day to 32,300 miles per day.

Two schools in the county operate on double sessions. Two

separate administrative units operate within the same facility

each day. The morning session has a different principal and

faculty than the afternoon session. This year double sessions

necessitate an additional $18,000 in bus drivers' salaries and

about 5,200 "non-essential miles".** Double sessions result in

less efficient use of buses. Since only students in particular

grade levels are picked up, buses must travel further to obtain

a full load and they must travel more miles empty.

Other non-essential costs have increased this year be-

cause the state computes mileage from the time a bus begins its

route at the driver's house until it stops at the garage after

dropping off the last student, and because the district has had

difficulty in finding bus drivers who live close to the beginning

of their routes.

During the 1970-71 school year, Hillsborough County spent

$1,206,708 for transportation, or about $37.23 per pupil bused.

This cost represented approximately 1.3% of the district's total

budget. Out of a total budget of over $119 million this year,

** "Non-essential miles" is a state department term indicating

the miles a bus travels without students, or miles a bus

travels off the main bus route if that detour is 1.5 miles

or less one way.

- v -

the school district is spending about $1,973,728 or 1.7%, for

transportation. The cost per pupil bused is $37.38.

The purchase of new buses has been a significant factor

in the increase in transportation costs this year. One hundred

and forty-five regular buses were bought, of which 20 had already

been budgeted. One million dollars was borrowed on a four-year

loan to pay for the new buses.

The Florida State Department of Education recommends that

school buses be replaced every ten years, yet in 1961, 1963, 1964,

1965 and 1966, Hillsborough County purchased no new buses. As

a result of this delay in bus replacement, 71 buses are now 11

or more years old, and 29 buses purchased in 1957 and 1958 are

now used as spares. If buses had been replaced on a regular

basis, Hillsborough County's bus fleet might have more easily

accommodated the increased student transportation and 29 old buses

would not have had to be utilized.

This year's total anticipated educational expenditures of

over $119 million are a considerable increase over 1970-71 when

somewhat more than $89 million· was spent. What is most interest

ing to note, however, is the substantial increase in the allocation

for capital improvements and debt service:

- vi -

Capital Improvements

Debt Service

1970-71

$12,034,617

2,838,883

1971-72 (est.)

$32,847,393

7,741,681

The investment in new buses represents a small percentage indeed

of the total capital outlay for Hillsborough County.

Despite the substantial increase in busing in Hillsborough

County and the reassignment of students to new schools, the

citizens of the metropolitan area, black and white alike, have

accommodated to the change brought by conversion to a desegre

gated school system. School officials have taken steps to ease the

transition. Specialists have been employed with ESAP funds to

work in each secondary school in the county. Bi-racial student

advisory committees have been established at each secondary school,

and together with the specialists, have helped to moderate inter

racial antagonisms. Facilities at the formerly black schools have

been improved. Air conditioning was installed and needed supplies

were increased, thus reducing parent complaints. While many black

students have resented losing their identity with their old high

schools, they have increasingly participated in extra-curricular

activities and sports at their new schools. Buses have been pro

vided to transport students home after regular school hours.

In the first week after school opened in the Fall of 1971,

many white parents did not send their children to school, and

others drove their children to schol and picked them up in the

vii -

afternoon because of fear of disruptions at formerly black

schools. But the disruptions failed to materialize, and after

several weeks white children began riding buses to school.

Approximately 2,000 white students left the public schools this

year. The fact that there was no greater amount of "white

flight" was due to the fact that the private schools in the

county resisted expanding their enrollment for students who

sought to avoid desegregation. Superintendent Raymond Shelton

has noted a trend of white students returning to public schools.***

Hillsborough County is an example of what can be accomplished

when a metropolitan-wide desegregation plan becomes the vehicle

for securing the constitutional rights of black children. Most

encouraging, however, is that the plan is not only working but

that at least one school official believes that, "maybe it isn't

so bad after all; maybe it is really worthwhile! 1164/

***Testimony of Chairman Theodore Hesburgh, U.S. Commission on

Civil Rights before Subcommittee No. 5 of the House Committee

on Judiciary, 6-15 (March l, 1972).

- viii -

NORTH CAROLINA - A PROFILE

North Carolina has several large, urban school districts

and is unique because it is the only state in the South that has

completely desegregated its city school systems. In the past

four years, pupil transportation has increased by 10% in the

state, from 55% of North Carolina's enrollment to 65%. Yet

only a small portion of that increase can be attributed to de

segregation of the urban areas.

In 1968-69 no school districts, including those mentioned

in this report, had desegregated school systems. During that

year over 9,200 school buses transported nearly 611,000 students

(almost 55% of all students in the state) at an annual cost of

over $14.2 million, which included the cost of purchasing bus

replacements. Over 352,000 miles were traveled in that year at

a cost of $23.40 per pupil.

In 1969-70 most North Carolina school systems were still

segregated, including all of the large, urban school districts.

In that year, over 9,400 vehicles transported nearly 630,000

students (over 57% of all the students in the state) at a cost

of over $19.1 million, which included the cost of bus replacements.

Over 357,500 miles were traveled at a cost of $30.39 per pupil.

During this year about 15,000 special education students became

- ix -

eligible, for the first time, for state reimbursed transporta

tion costs.

In 1970-71 Charlotte-Mecklenburg became the first urban

district in the state to approach the elimination of the dual

school system. There were other isolated cases where urban dis

tricts made beginning steps as, for example, Winston-Salem

Forsyth. Other urban districts remained almost totally segre

gated, such as Raleigh and Greensboro.

During 1970-71 nearly 10,000 vehicles were used to trans

port over 683,400 students (62% of all students in the state)

at a cost of over $21.3 million, including bus replacement.

375,370 miles were traveled that year with a per pupil cost of

$31.21. Significantly, this was the year when Sparrow v. Gill

became effective.

By 1971-72 nearly all school districts in the state had

made major steps in achieving unitary school systems. During

this year 10,400 vehicles have transported about 717,000 students

(nearly 65% of all pupils in the state).

As the above figures indicate, there has been a constant

increase during each school year (before and after desegregation)

in the number of vehicles, the cost of operations, the number of

miles traveled annually, the number of pupils transported and

the percent of pupils transported. Some items increased at a

- x -

faster rate than others.

The Sparrow decision resulted in approximately 54,000

additional students (requiring 589 additional buses) becoming

eligible for transportation. In the school year prior to 1968-69,

about 5,000 additional students became eligible for transportation

each year due to normal student population growth. A state

transportation official believes that approximately the same

pattern has existed for each school year since 1968-69.

Based upon our interviews with state officials and upon

our examination of their files and documents, we conclude that

of the approximately 106,200 students now transported who were

not transported in 1968-69 that:

Sparrow

Special education

Growth (6,000 students per

year x 3 ye~rs)

resulted in 54,000

accounted for 15,000

resulted in 18,000

Urban desegregation caused

TOTAL

19,000

106,000

Therefore, approximately 19,000 of the 717,000 students

transported in 1971-72 in North Carolina represents a net in-

crease in pupil transportation because of urban, court-ordered

desegregation. Other desegregation steps have decreased trans-

portation in the state.

- xi -

FOOTNOTES

1. N. Mills, Busing: Who's Being Taken For A Ride, 7

(ERIC-IRCD Urban Disadvantaged Series No. 27,

April, 1972) 0

2 a Testimony of Theodore M. Hesburgh, Chairman, U.S.

Commission on Civil Rights before Subcommittee

No. 5 of the House Committee on the Judiciary, 16

(March 1, 1972).

3. HEW Memorandum, from Constantine Menges to Christopher

Cross, 1 (March 30, 1972).

4. Supra, note 1, at 9.

5. U.S. Department of Transportation, Report on School

Busing, 1 (March 24, 1972).

6. Supra, note 1, at 7.

7. Id. at 12-13.

8. Interview with Harlan C. McNeil, Supervisor, Department

of Transportation, Lynchburg Public Schools, April 6,

1972.

9 o U.S. Office of Education, Elementary and secondary

Education Act of 1965 as Amended, Title I, Assistance

for Educationally Deprived Children, Expenditures

for Pupil Transportation services, Fiscal Year 1968.

10. Bradley v. The School Board of the city of Richmond,

Va., C.Aa No. 3353, F. Supp. (E aD. Va., Jan a 5,

1972) Slip Op. at 23"'7": ~

ll a Swann Va Charlotte-Mecklenburg, No. 1974, F. Supp.

(W.D. N.C a , October 21, 1971) Slip Op a 6.

12 0 Congressional Record, February 28, 1970, S2652-2653.

13 a Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

(W.D a N. c~r. Civ. A. No. 1974; unreported

supplementary Findings of Fact, March 21, 19700 see

petitioner's Appendix to petition for writ of

Certiorari, U.S. Sup. Ct. Oct. Term 1969, Noa 1713,

p. 142a.)

14 0 Testimony of Stephen Horn, Vice Chairman, U.S.

Commission on Civil Rights, before the Committee on

Education and Labor, House of Representatives, 5

(April 11, 1972).

- xii -

15. Winston-Salem-Forsyth county Public Schools,

Principal's Monthly Bus Report, March, 1971.

16. Hearings Before the Select Committee on Egual

Educational Opportunity of the U.S. senate, 92nd

Cong., lsto Sess., Part 18-Pupil Transportation

Costs, 9017 (October 6, 1971).

17 0 Memphis Commercial Appeal, JanQ 30, 1972.

18 0 Speech by c. A. Hunsinger, member, Pinellas County Board

of Education, A Chronology of Pinellas County School

Desegregation, March, 1972.

19. Memorandum from w. P. Patterson, Director of Trans

portation, Hillsborough County Board of Education to

Wayne Hull, Assistant Superintendent for Business,

October 15, 1971.

20. Interview with D. c. Windham, Transportation Supervisor,

Jackson Public Schools, April 10, 1972.

210 Interview with Mrs. Vivian Mason, member Norfolk City

Board of Education, January 24, 1972.

22 0 Remarks of Superintendent w. B. Thompson, Greenville

Municipal Separate School District, Board of Education

Meeting, August, 1971.

23. Interview with Superintendent cecil Hardesty and

Joseph J. Smith, Director of Finance, Duval County

Board of Education, Jan. 17, 1972 and April 4, 1972 0

24 0 Statement of Donald E. Morrison, president, National

Education Association before Subcommittee No. 5 of

the House Committee on Judiciary, 8 (March 2, 1972).

25. Supra, note 3, at 3 o

26. Id. at 2.

270 Supra, note 5.

28. Figures supplied by local and state officials o

29 0 Interview with Dr. John McLaulin, Assistant

Superintendent for Research and Planning, Norfolk