Lytle v. Household Manufacturing Inc. Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

August 31, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lytle v. Household Manufacturing Inc. Brief for Petitioner, 1989. c3141929-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fa2762d7-ae29-47df-b9f5-efc276e512bf/lytle-v-household-manufacturing-inc-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

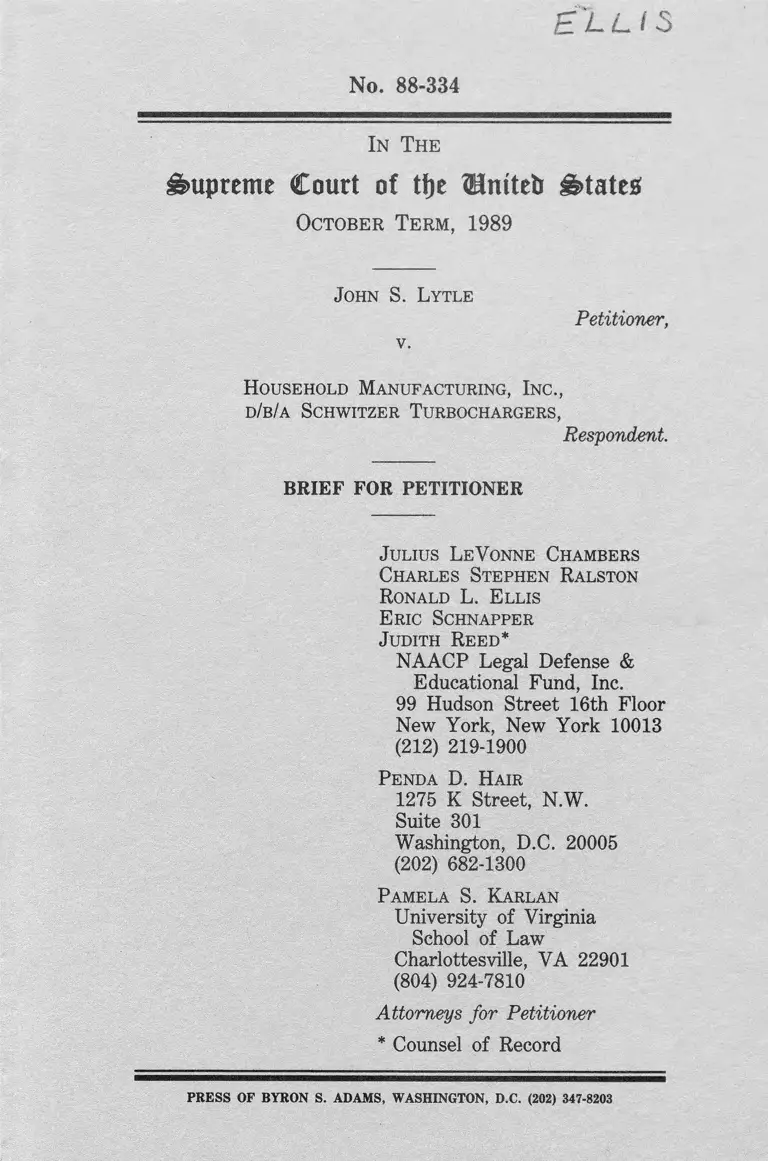

No. 88-334

' L L I O

In The

Supreme Court of tfje Uniteti states

October Term, 1989

John S. Lytle

v.

Petitioner,

Household Manufacturing, Inc.,

d/b/a Schwitzer Turbochargers,

Respondent.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

J ulius LeVonne Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

Ronald L. E llis

E ric Schnapper

J udith Reed*

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Penda D. Hair

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Pamela S. Karlan

University of Virginia

School of Law

Charlottesville, VA 22901

(804) 924-7810

Attorneys for Petitioner

* Counsel of Record

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

QUESTION PRESENTED

Did the Fourth Circuit err in holding violations of

the Seventh Amendment unreviewable on direct appeal

when the district court compounds the violation by decid

ing itself the questions that should have been presented

to the jury?

LIST OF PARTIES

The respondent, Household Manufacturing, Inc., is a

wholly owned subsidiary of Household International, Inc.

All other parties in this matter are set forth in the

caption.

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTION PRESENTED ............................................ i

LIST OF PA RTIES........................................................... ii

OPINIONS B E L O W ...................................................... 1

JURISDICTION............................................................. 1

STATUTES, CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION, AND

RULES INVOLVED.......................................... 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .................................. 5

1. Background.............................................. 5

2. Petitioner’s Term ination......................... 8

3. Respondent’s Retaliation ...................... 13

4. Proceedings in the District C o u rt.......... 14

5. Proceedings in the Court of Appeals . . 19

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................. 22

A RG UM ENT.................................................................. 25

iii

I. THE DECISION BELOW DEPRIVED

PETITIONER OF HIS RIGHTS UNDER THE

SEVENTH A M EN D M EN T...................... 25

A. The District Court Erroneously Deprived

Petitioner of His Right to a Jury Trial on

His § 1981 C la im s........................... 25

B. Petitioner Was Denied the Benefit of the

Fundamental Values Protected by the

Seventh Amendment Right to Trial by

JuD ........................................................... 28

II. THE DENIAL OF SEVENTH AMENDMENT

RIGHTS IS SUBJECT TO REVERSAL PER

SE ON DIRECT A PPEAL................................ 34

A. This Court Has Always Treated Seventh

Amendment Violations as Reversible Per

Se .......................................... 34

A Violation of the Seventh Amendment,

Like Other Errors Which Result in the

Wrong Entity Finding the Facts, Is

Subject To Reversal Per Se . .................. 41

III. THE COURTS BELOW ERRED IN

APPLYING PRINCIPLES OF COLLATERAL

ESTOPPEL TO THIS CASE ......................... . 45

A. Parklane Hosiery Does Not Apply to this

C a s e ............................................................ 45

iv

B. The Fourth Circuit’s Approach Would in

Fact Undermine the Interest in Judicial

Economy that the Doctrine of Collateral

Estoppel Is Intended to S e rv e ............... 52

CONCLUSION................................................................ 55

v

Cases

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Aetna Insurance Co. v. Kennedy,

301 U.S. 389 (1937)...................................................... 54

Aetna Life Ins. Co. v. Lavoie, 475 U.S. 813 (1986) . . . 43

Aetna Life Ins. Co. v. Ward, 140 U.S. 76 (1891).......... 31

Amoco Oil Co. v. Torcomian, 722 F.2d 1099

(3d Cir. 1 9 8 3 ) ............................................................... 36

Arizona v. California, 460 U.S. 605 (1983) .................... 47

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp.,

429 U.S. 252 (1977)...................................................... 31

Bank of Columbia v. Okely, 17 U.S.

(4 Wheat.) 235 (1819) ........................ 35

Baylis v. Travelers’ Ins. Co.,

113 U.S. 316 (1885).......................................... 28, 29, 35

Beacon Theatres, Inc. v. Westover, 359 U.S. 500

(1959) ....................................................................... passim

Bibbs v. Jim Lynch Cadillac, Inc., 653 F.2d 316

(8th Cir. 1981) ............................................ 36

vi

Buzard v. Houston, 119 U.S. 451 (1886) ...................... 35

Cohen v. Beneficial Industrial Loan Corp,,

337 U.S. 541 (1949)............................................... 24, 53

Coopers & Lybrand v. Livesay,

437 U.S. 463 (1978)...................................................... 53

Curtis v. Loether, 415 U.S. 189 (1974)............... 22, 26, 35

Dairy Queen, Inc. v. Wood, 369

U.S. 469 (1962)................................................... 23, 40, 50

Davis & Cox v. Summa Corp.,

751 F.2d 1507 (9th Cir. 1 9 8 5 )..................................... 36

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968) .................... 30

Dwyer v. Smith, 867JF.2d 184 (4th Cir. 1989)............... 45

EEOC v. Corry Jamestown Corp.,

719 F.2d 1219 (3d Cir. 1983) ..................................... 36

Ellis v. Union Pac. R.R. Co., 329 U.S. 649 (1947) . . . . 31

Estes v. Dick Smith Ford, Inc.,

856 F.2d 1097 (8th Cir. 1 9 8 8 )..................................... 32

Bouchet v. National Urban League, 730 F.2d 799

(D.C.Cir. 1984) ..................................................... 48, 49

Flemming v. Nestor, 363 U.S. 603 (1960)...................... 44

vii

Gomez v. United States, 109 S.Ct. 2237 (1989)............ 43

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co.,

107 S.Ct. 2617 (1987).................................................. 27

Granfinanciera S.A. v. Nordberg,

109 S.Ct. 2782

(1989) ......................................................... 23, 36, 37, 47

Gulfstream Aerospace v. Mayacamus Corp.,

109 S.Ct. 1133 (1988).................................................... 52

Hall v. Sharpe, 812 F.2d 644 (11th Cir. 1987).......... 36, 54

Hardin v. Straub, 109 S.Ct. 1998, (1989) ...................... 27

Hildebrand v. Bd. of Trustees of

Michigan State Univ.,

607 F.2d 705 (6th Cir. 1979)....... ...............................36

Hodges v. Easton, 120 U.S. 408 (1882) ............ 22, 29, 36

Hussein v. Oshkosh Motor Truck Co.,

816 F.2d 348 (7th Cir. 1987)........................... 20, 48, 49

Hyde v. Booraem & Co., 41 U.S.

(16 Pet.) 232 (1842)...................................................... 32

Gargiulo v. Delsole, 769 F.2d 77 (2d Cir. 1985) . . . . . 54

Jacob v. City of New York, 315 U.S. 752 (1942) . . . . . 29

viii

Katchen v. Landy, 382 U.S. 323 (1966) ................. 50, 51

Keller v. Prince George’s County,

827 F.2d 952 (4th Cir. 1987)...................... ................ 45

Killian v. Ebbinghaus, 110 U.S. 246 (1884).................... 35

Lauro Lines S.R.L. v. Chasser,

109 S.Ct. 1976

(1989) ........................................................ 25, 41, 42, 53

Lewis v. Cocks, 90 U.S. 70 (1874).................................. 36

Lewis v. Thigpen, 767 F.2d 252 (5th Cir. 1985)............ 36

Liljeberg v. Health Services Acquisition Corp.,

108 S.Ct. 2194 (1988) . . ............................................... 43

Lincoln v. Board of Regents, 697 F.2d 928 (11th Cir.

1983) .............................................................................. 27

Marshak v. Tonetti, 813 F.2d 13 (1st Cir. 1987) .......... 36

Matter of Merrill, 594 F.2d 1064 (5th Cir. 1979)........... 36

Meeker v. Ambassador Oil Corp., 375 U.S. 160

(1963) ....................................................................... passim

Midland Asphalt Corp. v. United States,

109 S.Ct. 1494 (1989).................................................... 52

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency,

421 U.S. 454 (1975)...................................................... 25

ix

Moore v. Sun Oil Co., 636 F.2d 154 (6th Cir. 1980) . . 27

Morgantown v. Royal Insurance Co.,

337 U.S. 264 (1949)....... .......................... .. 53

North v. Madison Area Ass’n for Retarded

Citizens, 844 F.2d 401 (7th Cir. 1988) ....................... 27

Owens v. Okure, 109 S.Ct. 573 (1989)........................... 27

Palmer v. United States,

652 F.2d 893 (9th Cir. 1981)...................... ................ 36

Parklane Hosiery Co. v. Shore, 439 U.S. 322

(1979) .................................................................... passim

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union,

105 L.Ed.2d 132 (1989) .................................. 22, 25, 26

Pennoyer v. Neff, 95 U.S. (5 Otto) 714 (1877) ___ _ . 46

Pernell v. Southall Realty, 416 U.S. 263 (1974)............ 35

Ritter v. Mount St. Mary’s College,

814 F.2d 986 (4th Cir. 1986)........................... 20, 45, 49

Roebuck v. Drexel University,

852 F.2d 715 (3d Cir. 1988) ....................................... 48

Rose v. Clark, 478 U.S. 570 (1 9 8 6 )................................ 41

Schoenthal v. Irving Trust Co., 287 U.S. 92 (1932) . . . 35

x

Setser v. Novack, 638 F.2d 1137 (8th Cir. 1 9 8 1 )..........27

Sibley v. Fulton DeKalb Collection Service,

677 F.2d 830 (11th Cir. 1 982 )..................................... 36

Sioux City & Pacific R.R. Co. v. Stout,

84 U.S. (17 Wall.) 657 (1 874 )............................. 22, 29

Skinner v. Total Petroleum,

859 F.2d 1439 (10th Cir. 1988) .................................. 27

Standard Oil Co. v. Brown 218 U.S. 78 (1 9 1 0 )............ 32

Stevens v. Nichols, 130 U.S. 230 (1889)......................... 44

Swentek v. USAir, 830 F.2d 552 (1987 )........................ 45

Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522 (1975)'...................... 30

Tennant v. Peoria & P^kin Union Ry. Co.,

321 U.S. 29 (1944)........................................................ 31

Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217 (1945) 30, 44

Tull v. United States,

95 L.Ed.2d 365 (1987) .................................. 21, 23, 37,

38, 47

United States v. One 1976 Mercedes Benz 208 S,

618 F.2d 453 (7th Cir. 1980)................................ 30, 36

Scott v. Neely, 140 U.S. 358 (1891)................................ 35

xi

United States v. State of New Mexico,

642 F.2d 397 (10th Cir. 1 9 8 1 )..................................... 36

Volk v. Coler, 845 F.2d 1422 (7th Cir. 1988) . . . ____48

Wade v. Orange County Sheriffs Office,

844 F.2d 951 (2d Cir. 1988) ........................................ 48

Webster v. Reid, 52 U.S. 437 (1850) .................... 36

Western Elec. Co. v. Milgro Electronic Corp,

573 F.2d 255 (5th Cir. 1978)........................................ 53

Williams v. Cerberonics, Inc.,

871 F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1989)..................... ................ 48

Williams v. Owens-Illinois, Inc.,

665 F.2d 918 (9th Cir.),

cert, denied, 459 U.S. 971 (1982) . .............................. 27

Wilson v. Garcia, 471 U.S. 261 (1985)............... ' . . . . . 27

Statutes. Constitutional Provisions and Rules

28 U.S.C. § 455 ................................................................. 43

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) . ........................................................... . 2

28 U.S.C. § 1861.................................................................... 30

42 U.S.C. § 1981 passim

xii

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 ............................................................. 5

Rule 38, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure . . . . 4, 27, 54

Rule 39 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ..........4

Rule 41(b), Federal Rules of Civil P rocedure.......33

Rule 52(a), Federal Rules of Civil P rocedure...... 43

Title VU'of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ...............passim

U.S. Const, amend. VII ...............................................passim

Other Authorities

9 Wright & Miller,

Federal Practice and Procedure § 2322 .................. 54

18 Wright, Miller & Cooper,

Federal Practice and Procedure § 4418

(1989 Supp.)...................................................................... 48

Schnapper, Judges Against Juries --

Appellate Review of Federal Jury Verdicts,

1989 Wis.L.Rev. 237 ..................................

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-(2)(a) .................................................... 3

xiii

31, 32

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the court of appeals is unpublished,

and is set out in the Appendix to the petition for writ of

certiorari ("App.") at pages la-21a. The order of the

court of appeals denying rehearing, which is not

reported, is set out at App. 22a-24a. The district judge’s

bench opinion, which is unreported, is set out at App.

25a-31a and in the Joint Appendix (JA) at pages 56-64.

The order of the district court dismissing the case is set

out at App. 34a-35a.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court of appeals affirming the

district court’s dismissal of the case was entered on

October 20, 1987. App. la. A timely petition for

rehearing was denied on Apri! 27, 1988. On July 19,

1988, Chief Justice Rehnquist entered an order extending

the time for filing a petition for writ of certiorari to and

including August 25, 1988. The petition for writ of

certiorari was filed on August 23, 1988, and was granted

on July 3, 1989. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

STATUTES, CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION,

AND RULES INVOLVED

The Seventh Amendment to the United States

Constitution provides:

In suits at common law, where the value in

controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of

trial by jury shall be preserved and no fact tried by

jury shall be otherwise re-examined in any Court of

the United States, than according to the rules of the

common law.

2

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal

benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of

persons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens,

and shall be subject to like punishment, pains,

penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind,

and to no other.

Section 703(a) of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-(2)(a), provides in pertinent

part:

Section 1981 of 42 U.S.C. provides:

It shall be an unlawful employment practice

for an employer-

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge

any individual, or otherwise to discriminate against

any individual with respect to his compensation,

terms, conditions, or privileges of employment

because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex,

or national origin . . . .

3

Rule 38 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provides

in pertinent part:

(a) Right Preserved. The right of trial by

jury as declared by the Seventh Amendment to the

Constitution or as given by a statute of the United

States shall be preserved to the parties inviolate.

(b) Demand. Any party may demand a trial

by jury of any issue triable of right by a jury by

serving upon the other parties a demand therefor in

writing at any time after the commencement of the

action and not later than 10 days after the service of

the last pleading directed to such issue. Such

demand may be indorsed upon a pleading of the

party.

Rule 39 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provides

in pertinent part:

(a) By Jury. When trial by jury has been

demanded as provided in Rule 38, the action shall

be designated upon the docket as a jury action. The

trial of all issues so demanded shall be by jury,

unless (1) the parties or their attorneys of record, by

written stipulation filed with the court or by an oral

stipulation made in open court and entered in the

record, consent to trial by the court sitting without a

jury or (2) the court upon motion or of its own

initiative finds that a right of trial by jury of some or

4

all of those issues does not exist under the

Constitution or statutes of the United States.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This action involves claims of intentional racial

discrimination in violation of 42 U.S.C. § 1981 and Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42

U.S.C. § 2000e-5. Petitioner John S. Lytle, a black

person, contends that he was fired by respondent on

account of his race and that respondent then retaliated

against him for pursuing his federal equal employment

opportunity claims.

1. Background

Schwitzer Turbochargers, a subsidiary of respondent

Household Manufacturing, Inc. [hereafter referred to as

"Schwitzer"], makes turbochargers and fan drives at its

Arden, North Carolina, plant. Tr. 13. In February 1982,

5

Schwitzer adopted an employee absence policy with the

following salient features. First, workers must report all

anticipated absences to their supervisors "as soon as

possible in advance of the time lost, but not later than

the end of the shift on the previous workday." PX 22, p.

1. Second, certain kinds of absences -- in particular,

those involving personal illness, PX 22, p. 2 - are

characterized as "excused." Third, even though absence

due to illness is excused, an "excessive" level of such

absences - defined as a "total absence level which

exceed[s] 4% of the total available working hours,

excluding overtime," id. at 2-3 - "will, most likely, result

in termination of employment." Id. at 3. Fourth, a

worker also faces termination for excessive absence if he

has "any unexcused absence which exceeds a total of 8

hours (or one scheduled work shift) within the preceding

12-month period." Id.

6

Petitioner is an experienced machine operator.1 Tr.

84. In January 1981, he was hired by respondent as a

machinist trainee at the Arden plant. Less experienced

whites were hired directly into machine operator

positions. Tr. 83-84, 87. Ultimately, petitioner achieved

the highest graded machinist classification. Tr. 87-89. In

his 1982 performance evaluation, he was commended for

his good attendance record, t r . 86; PX 6. Until the

events that precipitated this lawsuit, he had never been

reprimanded or disciplined for attendance problems. Tr.

86-87.

' This discussion of the events pertaining to petitioner’s

discharge claim is based primarily on Lytle’s testimony at trial. The

district court dismissed his discharge claim at the close of

petitioner’s evidence; hence, virtually all the record testimony on

behalf of the respondent goes only to retaliation, not discharge.

7

2. Petitioner’s Termination

In February 1983, petitioner embarked on a rigorous

evening program studying mechanical engineering at

Asheville-Biltmore Technical College. Tr. 90-95.2 By the

summer, he began to suffer health problems. The plant

nurse recommended that he consult a doctor. Tr. 71-72,

121. In June or July, Lytle also informed his supervisor,

Larry Miller, who was white, of his health problems and

stated that for this reason he preferred not to work

overtime. Tr. 120.

At the beginning of August 1983, Lytle cut back his

school program to two evenings per week. Tr. 95.

During the first week of August, Schwitzer machinists

2 On class days, Lytle left work at 3:30 p.m., arrived home

about 4:00 p.m., had something to eat, arrived at the college library

to study at 4:30 or 5:00 p.m., and attended class from 6:30 p.m. until

between 9:00 and 11:00 p.m. Tr. 92. He also frequently found it

necessary to study in the late evening and early morning hours. Tr.

120.

8

were called upon to work a substantial amount of

overtime in order to keep up with production

requirements. Tr. 238.

The next week, Lytle’s health problems worsened,3

and he scheduled an appointment for Friday, August 12,

1983, with a doctor who had been recommended by the

Schwitzer nurse. Tr. 122, 130-131. On Thursday

morning, August 11, Lytle asked his supervisor for

permission to schedule Friday, August 12, as a vacation

day. Tr. 129-132.4

At the time, Miller approved petitioner’s request.

Tr. 130. However, later in the day, Miller told petitioner

that "if you’re off Friday, you have to work on Saturday,"

3 On one occasion he became so dizzy that he fainted. Tr.

132.

4 Although sick leave would have been granted for a

doctor’s appointment, Lytle preferred to have the absence treated as

a vacation day. Tr. 194* Such treatment meant that the day would

not be counted as an absence under Schwitzer’s policy regarding

"excessive absence." Tr. 208.

9

Tr. 131, which was not a normal work day for Lytle, Tr.

132. Lytle "explained that I wanted Friday off to see the

doctor, and I wouldn’t be able to work Saturday because

I was physically unfit." Tr. 131-32. When Miller still

insisted that Lytle work on Saturday, Lytle told him that

he would also take Saturday as a vacation day. Tr. 132.

Miller walked off, without objecting to this suggestion.

Tr. 132. Lytle understood that Friday would be treated

as a vacation day, and that he had sufficiently informed

Miller that he was physically unable to work on Saturday.

Tr. 191. Moreover, Lytle repeated his intentions to the

10

Human Resources Counselor, Judith Boone. Tr. 137-

138.5

Lytle returned to work on Monday, August 15.

After a meeting with Schwitzer’s personnel manager and

Miller, during which Lytle was asked to provide an

explanation for his absence, Lytle was fired. Tr. 142-

143. The apparent reason for the termination was for

alleged excessive unexcused absences, primarily the

Friday and Saturday shifts Lytle had missed as a result of

his health problems.6 JA 8; Tr. 220. Had petitioner’s

Boone confirmed that Lytle had a conversation with

her that day regarding problems with Miller; however, she testified

that she did not recall any mention of vacation scheduling. Tr. 60-

61.

6 In addition to the two days in question, apparently

Schwitzer treated Lytle’s departure on Thursday, August 11, shortly,

after the normal end of his shift, as 1.8 hours of "unexcused

absence," because he did not work two hours of overtime that may

or may not have been scheduled. There was conflicting evidence

concerning whether Lytle was in fact scheduled for overtime on

Thursday and whether his purported failure to inform Miller that he

had to leave was directly attributable to Miller’s behavior toward

Lytle. Tr. 135. In any event, the district judge found Lytle to have

had 9.8 hours of unexcused absence. JA 59-60.

11

absences been properly classified either as vacation days

or as excused absences, he would not have fallen within

the terms of the excessive absence policy. Tr. 252-253.

Moreover, Schwitzer’s records showed that white

employees were not terminated despite "excessive

absence." Instead, these white workers were given

warnings and an opportunity to improve.7

7 Donald Rancourt, a white machinist, received a written

warning from Larry Miller concerning an absence rate of 7.5% in

January', 1983. Tr. 217-18, 222, 230. Rancourt’s April 1983 annual

performance review mentioned an absence problem Tr. 48; PX 15-

C, page 4. Rancourt was not terminated. Tr. 54.

As of March 2, 1984, Jeffrey C. Gregory, a white machinist, had

an annual absence level of 6.3% of total available working hours.

Tr. 57-58; PX 28-B. He was not terminated. Tr. 58. It is not clear

whether he was even counselled concerning his excessive

absenteeism. Tr. 58.

On July 13, 1983, approximately one month prior to Schwitzer’s

termination of Lytle, Rick Farnham, a white machine operator, was

counselled for excessive absenteeism. Tr. 55-56; PX 12-B. At that

time Farnham’s annual absence rate was 4.3%. Tr. 56; PX 12-B.

Farnham was not terminated.

On August 23, 1982, David Calloway, a white machinist, was

given his second warning in three months about excessive

absenteeism. In June, 1982, his absence percentage was 4.5%, and

he was warned that "an immediate improvement must be made." PX

13-B, p. 1. In August, his absence percentage remained at 4.5% He

had been absent for a total of 16.2 hours since the June warning,

and two absences were on consecutive Mondays. Tr. 44. Instead of

termination, Calloway was given an additional sixty days in which to

12

3. Respondent’s Retaliation

On August 23, 1983, Lytle filed a charge of

discrimination with the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission. Tr. 61; PX 1. This charge was received by

Schwitzer’s Human Resources Counselor, Judith Boone,

who is white, shortly thereafter. Tr. 61-62.

At approximately the same time, Lytle began looking

for another job in the Asheville area. Several

prospective employers told him that they were having

difficulty getting an adequate reference from Schwitzer.

Tr. 111. Boone refused to return questionnaires from

correct the problem. PX 13-B.

Finally, Greg Wilson, a white machinist, was absent two

successive days without obtaining prior approval. Tr. 23-24. Of the

sixteen hours of absence, eight were categorized as unexcused. The

second day’s absence was "excused” because Wilson called to inform

his supervisor that he was ill. This two-day absence followed three

unexcused tardies. Thus, as of March, 1983, Wilson had

accumulated excessive unexcused absences. Tr. 67. Yet, Wilson was

not fired, but merely counselled to improve his absence record. PX

14B.

13

two employers. Although Schwitzer claimed that it was

merely applying its normal policy with respect to

references for individuals who have been involuntarily

terminated, Tr. 261, the company had in fact provided a

favorable letter of reference for Joe Carpenter, a white

male, the only other machinist involuntarily terminated

prior to Lytle in 1983. See PX 10.

4. Proceedings in the District Court

Lytle filed a complaint in federal district court

alleging that respondent had fired him because of his

race and retaliated against him for filing a charge of

discrimination with the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission, all in violation of both Title VII and Section

1981. JA 9-10. The notation "Jury Trial Demanded"

appears on the first page of the complaint, JA 4, and at

the end of the complaint was the following statement:

14

"Plaintiff requests a jury trial of all issues triable herein

by a jury." JA 14. The relief requested involved

backpay, damages for "emotional and mental suffering,"

punitive damages, and injunctive relief including

reinstatement.

Respondent answered the complaint and ultimately

moved for summary judgment on several grounds. On

May 17, 1985, the district court denied the motion,

finding that "there is a genuine issue as to material facts."

Dkt. Nr. 19.

On the day of trial, the district court granted

Schwitzer’s motion to dismiss all claims under § 1981,

holding that Title VII provides the exclusive remedy for

employment discrimination. The dismissal of petitioner’s

§ 1981 claims necessarily meant the striking of his jury

15

demand. JA 56-57.8 The court then conducted a bench

trial of petitioner’s Title VII claims.

In essence, the trial revolved around four issues -

whether Lytle had in fact received permission from

Miller not to work on Friday and Saturday, whether the

decision to fire Lytle was based in whole or in part on

impermissible racial motives, whether Schwitzer’s absence

policies had been applied to white workers who were

similarly situated, and whether the refusal to provide a

reference for Lytle involved retaliation for his having

filed a Title VII charge. Resolution of each of these

issues was critically dependent on the factfinder’s

assessment of the credibility of the witnesses and the

plausibility of their conflicting stories.

8 The district court did not rule on the proposal made by

Lytle’s attorney that the court "dismiss the Title VII action and go

to the jury on the 1981 action.” Tr. 4. The district court also

denied Lytle’s motion for reconsideration of the § 1981 dismissal

made on the second day of trial. JA 97-98.

16

At the close of petitioner’s case, the court dismissed

petitioner’s Title VII discriminatory discharge claims,

finding that he had failed to present a prima facie case.

The district judge found that, while Lytle had

demonstrated that one white employee, Greg Wilson, had

exceeded the limit on unexcused absences and that at

least four white employees who violated the excessive

absence policy were only given warnings, the conduct of

these employees was not "substantially similar in

seriousness" to that of petitioner. Tr. 259; JA 59-60.

This determination was based apparently on the judge’s

supposition that Schwitzer treated excused and unexcused

absences differently, and that Wilson’s infraction was de

minimis. However, there was no evidence that the

employer intended to treat the classes of absences

differently as to the ultimate penalty that could be

17

imposed,9 and the record was, by the trial judge’s own

recognition, unclear on the exact amount of Wilson’s

additional absences.10

Following the close of all the evidence, the judge

ruled from the bench in favor of respondent on the

Indeed, the record contradicts such a conclusion in the

several respects. First, Schwitzer’s absence policy itself includes both

excused and unexcused absences in the category for which

termination will "most likely result," when the stated limits are

exceeded. PX 22, p. 2. Second, the policy notes that termination of

employment may result even before maximum limits are reached,

where a pattern of absence, excused or unexcused, is observed. Id.,

p. 3. Finally, Schwitzer has already made a distinction between

unexcused and excused absences by adopting a policy that permits

excused absences to total at least 72 hours, assuming a year

consisting of 48 weeks of 40 hours each, while tolerating only 8

hours of unexcused absences. Id.; Tr. 17 ("On the excused portion

. . . , we have allowed more flexibility there."). The trial judge’s

addition of yet another layer of distinction, by finding that excessive

excused absences are not "serious," in the face of a policy statement

that "absence hurt us all" (PX 22, p. 3), suggests that the trial judge,

was not acting merely as a factfinder, but was drawing a number of

inferences from the evidence. Opposite inferences could have as

easily been drawn. See, infra, Argument, Sec. I.B.

10 The trial judge concluded that Wilson had exceeded the

limit by only six minutes, based on his interpretation of the

documents. Tr. 251-252. ("Frankly, the evidence wouldn’t support

this, but I think that decimal number . . . really means minutes

rather than hundreths.") Cf. PX 14-B; Tr. 39, line 16-17; PX 14-C

(indicating nine tardy incidents during the period of March 1983

through February 1984).

18

retaliation claim.11 App. 26a-31a. The trial judge

subsequently entered a judgment for defendant on all

issues. App. 32a-35a.

5. Proceedings in the Court of Appeals

On appeal to the Fourth Circuit, petitioner argued,

among other things, that the district court’s erroneous

dismissal of his § 1981 claim had denied him his Seventh

Amendment right to a jury trial.

A majority of the Fourth Circuit panel acknowledged

that the district court had erred in dismissing petitioner’s

§ 1981 claim. App. 7a, n.2. But although the Court

recognized that petitioner had been wrongfully denied

the right to present his claims of intentional racial

11 The district judge found that the fact that Schwitzer had

issued a favorable letter of recommendation for a white who was the

only other employee whose employment had been involuntarily

terminated was not sufficient; rather the judge found that instead of

Lytle receiving disparate treatment, the white employee had simply

been treated "disproportionately favorably." Tr. 203.

19

discrimination to a jury, it refused to correct this

constitutional error. Instead, the appellate court followed

Ritter v. Mount St. Mary’s College. 814 F.2d 986 (4th

Cir. 1986), cert, denied. 108 S. Ct. (1987), and held that

the findings made by the district judge during the bench

trial of petitioner’s Title VII claims collaterally estopped

petitioner from litigating his § 1981 claim. App. 8a-9a.

Notably, the Court of Appeals did not conclude that a

jury would necessarily have reached the same factual

conclusions as the district judge. Rather, it determined

only that the. district judge’s findings of fact were "not

clearly erroneous." App. 10a-13a.

Judge Widener, in a dissenting opinion, noted that

the majority’s view of collateral estoppel was inconsistent

with a Seventh Circuit decision on "exactly this issue" in

Hussein v. Oshkosh Motor Truck Co.. 816 F.2d 348 (7th

Cir. 1987), and that it was "not consistent with" the

20

recent decision of this Court in Tull v. United States. 95

L.Ed.2d 365 (1987). App. 19a. He concluded that if the

appellate courts were powerless to correct the erroneous

denial of a jury trial merely because the judge involved

had issued a constitutionally tainted decision of his own

on the merits, "the Seventh Amendment means less today

than it did yesterday." Id. A timely petition for

rehearing and suggestion for rehearing en banc were

denied with Judges Widener, Russell and Murnaghan

voting to rehear the case en banc. Id. at 22a-24a.

21

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. Throughout this nation’s history the right to

trial before a jury of one’s peers has held a revered

place in American jurisprudence. Hodges v. Easton. 120

U.S. 408 (1882). The jurisprudence of this Court has

recognized that juries bring to their evaluation of the

facts a perspective that is distinct from that of judges.

Sioux City & Pacific R.R. Co. v. Stout. 84 U.S. (17 Wall.)

657 (1874).

The Seventh Amendment preserved the right

to a jury in actions at law and therefore those brought to

enforce statutory rights. Curtis v. Loether. 415 U.S. 189

(1974). Thus, plaintiffs possess that right in actions

brought under section 1981, provided that, as here, a

proper demand has been made. Patterson v. McLean

Credit Union. 105 L.Ed.2d 132 (1989). Where legal

22

and equitable claims are joined in the same action, this

Court has held that the right to a jury trial on the legal

claims is not lost, and the jury claims are to be tried first,

absent compelling circumstances. Beacon Theatres. Inc,

v. Westover. 359 U.S. 500 (1959); Dairy Queen. Inc, v.

Wood. 369 U.S. 469 (1962).

II. When a district court flouts this rule, this

Court has consistently reversed the judgment below and

remanded for trial before a jury. This Court has never

sanctioned appellate review that proceeds as if the error

never happened. Granfinanciera S.A. v. Nordberg. 109

S.Ct. 2782 (1989); Tull v. United States. 481 U.S. 412

(1987); Meeker v. Ambassador Oil Corp.. 375 U.S. 160

(1963).

The court of appeals fundamentally misapplied this

Court’s decision in Parklane Hosiery Co. v. Shore. 439

U.S. 322 (1979). Parklane cannot be read, as did the

23

Fourth Circuit, to apply collateral estoppel to preclude

review on direct appeal of a Seventh Amendment

violation. Parklane applies by its terms, as do all

principles of preclusion, to subsequent proceedings rather

than to appellate review in a single proceeding. This

Court has never held that a district court may accomplish

by error what Beacon Theatres prohibits it from doing

purposefully.

III. A rule that an appellate court may not review

violations of the Seventh Amendment, so long as the

district court’s findings are not clearly erroneous, would

fail to serve the interest in judicial repose fostered by the

rules of preclusion. Instead, such a procedure would

increase the burden on appellate courts by requiring

parties to proceed by mandamus or take an interlocutory

appeal, whenever their constitutional right to a jury has

been violated. Lauro Lines S.R.L. v. Chasser. 109 S.Ct.

24

1976 (1989); Cohen v. Beneficial Industrial Loan Corp.,

337 U.S. 541 (1949).

ARGUMENT

I. THE DECISION BELOW D EPR IV ED

PETITIONER OF HIS RIGHTS UNDER THE

SEVENTH AMENDMENT

A. The District Court Erroneously Deprived

Petitioner of His Right to a Jury Trial on His

g 1981 Claims

The Court of Appeals correctly recognized that

petitioner’s complaint stated a claim under § 1981.

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency. 421 U.S. 454 (1975).

In fact, the complaint raised two distinct violations of §

1981.12 It alleged that respondent had fired petitioner on

12 In Patterson v. McLean Credit Union. 105 L.Ed.2d 132

(1989), this Court reaffirmed the application of § 1981 to private

conduct and held that § 1981 covered the making and enforcing of

employment contracts, although it did not cover racial harassment

occurring after the formation of the contract.

25

account of race, and it alleged that respondent had

retaliated against petitioner because petitioner had

pursued his rights under Title VII.

Petitioner was entitled to a jury trial of his § 1981

claims.13 As this Court noted in Curtis v. Loether. 415

U.S. 189 (1974), the "Seventh Amendment . . . applies]

to actions enforcing statutory rights, and requires a jury

trial upon demand, if the statute creates legal rights and

remedies enforceable in an action for damages in the

ordinary courts of law." Id. at 194.14 Applying that

principle, every court of appeals to have addressed the

issue has recognized that the Seventh Amendment

3 The fact that the district court denied respondent’s

summary judgment motion on petitioner’s Title VII claims because

it saw "a genuine issue as to material facts” regarding what in fact

happened, JA 23, strongly substantiates the conclusion that, had the

court not applied erroneous legal principles to petitioner’s § 1981

claims, petitioner would have been entitled to present the facts

underlying those claims at trial.

14 See also, Patterson v. McLean Credit Union. 105

L.Ed.2d 132, 156 (1989) (addressing jury instruction issue).

26

applies to § 1981 actions when the jury demand has been

properly preserved.15 That conclusion is further

buttressed by this Court’s holding that cases under the

Reconstruction Civil Rights Acts resemble traditional tort

actions (which lie within the core of the Seventh

Amendment), and thus that the state statutes of

limitations to "borrow" in § 1981 cases are those used in

tort cases. See, e.g.. Hardin v. Straub. 109 S.Ct. 1998,

2000 (1989); Owens v. Okure. 109 S.Ct. 573 (1989);

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co.. 107 S.Ct. 2617 (1987);

Wilson v. Garcia. 471 U.S. 261 (1985).

It is undisputed in this case that Lytle made a timely

request for a jury trial pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 38,

15 See, e.g.. Moore v. Sun Oil Co.. 636 F.2d 154 (6th Cir.

1980) ; North v. Madison Area Ass’n for Retarded Citizens. 844 F.2d

401 (7th Cir. 1988); Setser v. Novack. 638 F.2d 1137, 1147 (8th Cir.

1981) ; Williams v, Owens-Illinois, Inc., 665 F.2d 918, 929 (9th Cir.),

cert, denied. 459 U.S. 971 (1982) ; Skinner v. Total Petroleum. 859

F.2d 1439 (10th Cir. 1988); Lincoln v. Board of Regents. 697 F.2d

928, 935 (11th Cir. 1983).

27

and that he never waived that demand. In fact, he

continued to object to the denial of his Seventh

Amendment rights even after trial was underway. Thus,

the district court erred by "substituting] itself for the jury

and, passing upon the effect of the evidence, finding] the

facts involved in the issue and rendering] judgment

thereon." Bavlis v. Travelers’ Ins. Co.. 113 U.S. 316, 321

(1885).

B. Petitioner Was Denied the Benefit of the

Fundamental Values Protected bv the Seventh

Amendment Right to Trial by Jury

The Seventh Amendment provides in pertinent part

that ”[i]n suits at common law, where the value in

controversy shall exceed $20, the right of the trial by jury

shall be preserved . . . ." That entitlement holds a

special, privileged position in American jurisprudence as

a "basic and fundamental" right to be jealously guarded.

28

Jacob v. City of New York. 315 U.S. 752 (1942); Bavlis v.

Travelers’ Ins. Co., supra: Hodges v. Easton. 106 U.S.

(16 Otto) 408 (1882).

This Court has long recognized the critical function

juries perform:

[I]t is a matter of judgment and discretion, of

sound inference, what is the deduction to be

drawn from the undisputed facts . . . . It is this

class of cases and those akin to it that the law

commits to the decision of a jury. Twelve men of

the average of the community, comprising men

of education and men of little education, men of

learning and men whose learning consists only in

what they have themselves seen and heard, the

merchant, the mechanic, the farmer, the laborer;

these sit together, consult, apply their separate

experience of the affairs of life to the facts

proven, and draw a unanimous conclusion. This

average judgment thus given it is the great effort

of the law to obtain. It is assumed that twelve

men know more of the more common affairs of

life than does one man, that they can draw wiser

and safer conclusions from admitted facts thus

occurring than can a single judge.

Sioux City & Pacific R.R. Co. v. Stout. 84 U.S. (17 Wall.)

657, 664-64 (1874). It is precisely because the system of

29

adjudication benefits so strongly from "the infusion of the

earthy common sense of a jury," United States v. One

1976 Mercedes Benz 208 S. 618 F.2d 453, 469 (7th Cir.

1980), that the Court and Congress16 have repeatedly

insisted, in both civil and criminal cases, that juries be

drawn from the widest possible section of the community.

See, e.g., Taylor v. Louisiana. 419 U.S. 522 (1975);

Duncan v. Louisiana. 391 U.S. 145 (1968); Thiel v.

Southern Pacific Co.. 328 U.S. 217 (1945). As Chief

Justice Rehnquist noted in his dissent in Parklane

Hosiery Co. v. Shore. 439 U.S. 322, 344 (1979), "juries

represent the layman’s common sense, the ’passional

elements in our nature,’ and thus keep the administration

of law in accord with the wishes and feelings of the

28 U.S.C. § 1861 et seq. (Jury System Improvements

Act of 1978).

30

community. O. Holmes, Collected Legal Papers 237

(1920)."

The right to litigate claims under § 1981 before a

jury can be especially important. When a plaintiffs claim

rests on the assertion that a facially neutral action was

undertaken for invidious racial purposes, the factfinder’s

assessment will often depend on "a sensitive inquiry into

such circumstantial and direct evidence of intent as may

be available." Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 266 (1977). The factfinder will

often be called upon to draw on his or her experience in

the real world in assessing the plausibility of conflicting

testimony,17 and making inferential judgments.18 The

17 Aetna Life Ins. Co. v. Ward. 140 U.S. 76, 88 (1891); Ellis

v. Union Pac. R.R. Co.. 329 U.S. 649, 653 (1947). See, also,

Schnapper, Judges Against Juries - Appellate Review of Federal

Jury Verdicts. 1989 Wis.L.Rev. 237, 265-67.

18 Tennant v. Peoria & Pekin Union Rv. Co.. 321 U.S. 29,

34-35 (1944) ("It is the jury, not the court, which . . . weighs the

contradictory evidence and inferences . . . and draws the ultimate

31

perspectives of lay people, of different racial and ethnic

backgrounds, both male and female, many of whom are

likely to have had employment histories similar to a

plaintiff, are bound often to result in juries reaching

conclusions "that a judge either could not or would not

reach." Parklane Hosiery Co. v. Shore. 439 U.S. at 344

(Rehnquist, J., dissenting). That a factual "dispute

relates to an element of a prima facie case under

McDonnell-Douglas . . . does not make it any less a

matter for resolution by the jury." Estes v. Dick Smith

Ford. Inc.. 856 F.2d 1097, 1101 (8th Cir. 1988).

The instant case, involving straightforward claims but

conclusion as to the facts. The very essence of its function is to

select from among conflicting inferences and conclusions that which

it considers most reasonable."); Standard Oil Co. v. Brown 218 U.S.

78, 86 (1910) (”[W]hat the facts were . . . and what conclusions were

to be drawn from them were for the jury and cannot be reviewed

here."); Hvde v. Booraem & Co.. 41 U.S. (16 Pet.) 232, 236 (1842)

("We have no authority, as an appellate court, upon a writ of error,

to revise the evidence in the court below, in order to ascertain

whether the judge rightly interpreted the evidence or drew right

conclusions from it. That is the proper province of the jury . . . .").

Schnapper, n. 17, at 277-83.

32

conflicting evidence, is precisely the sort of litigation

where a judge and jury might well have reached

diametrically opposite conclusions.19 A jury of

laypersons, who resided in North Carolina and who

worked in a similar setting, might well have concluded,

for example, that Lytle was justified in believing that he

did not have to call in on Saturday, because both Friday

and Saturday were excused.20 Had Miller testified, a jury

might well have decided that his treatment of Lytle was

not free from racial motives, based on credibility-

determinations, inferences from the evidence that racial

discrimination had entered into Lytle’s hiring (supra, p.7),

19 Lytle’s testimony of the events is all that was before the

district, since the trial judge’s Rule 41(b) dismissal truncated the

proof. While it may be presumed that Miller would have disputed

some of this testimony, he has never testified as to his version of

the events of August 11, 1983.

20 The trial judge agreed that such a conclusion would be

a "reasonable interpretation of the evidence." Tr. 252-53. Moreover,

the district court found that at least one of the days in question was

excused. See n. 6, supra.

33

or the fact that white employees were treated differently.

Similarly, with regard to Lytle’s claim of retaliation, a

jury might well have concluded, not that the glowing

letter of reference for Carpenter was inadvertent21 but,

that no such reference was given to Lytle because he had

taken action to redress an alleged violation of his

federally granted rights.

II- THE DENIAL OF SEVENTH AMENDMENT

RIGHTS IS SUBJECT TO REVERSAL PER SE

ON DIRECT APPEAL

A. This Court Has Always Treated Seventh

Amendment Violations as Reversible Per Se

This Court has long recognized that "the claims of

the citizen on the protection of this court [and, since the

Joe Carpenter was fired for falsification of timesheets.

Tr. 214-25. Carpenter, a white machinist who was the only

Schwitzer employee other than Lytle fired in 1983, PX 19. Thus,

although Lane Simpson, Schwitzer’s manager of human resources

testified on direct examination that he confused Carpenter with

somebody else, a jury might have rejected this assertion based on

that fact as well as on statements he made during cross examination.

See, Tr. 271-274.

34

development of the courts of appeals, on those courts as

well] are particularly strong" when a litigant has been

denied his Seventh Amendment rights. Bank of

Columbia v. Okelv. 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 235, 240 (1819).

Thus, the Court has repeatedly and consistently redressed

Seventh Amendment violations by directing that the

issues improperly heard by a judge be retried. before a

jury. This Court has never excused the Seventh

Amendment violation by holding that the judge’s

intervening factual findings pretermit presentation of a

litigant’s case to a jury. See, e.g.. Pernell v, Southall

Realty. 416 U.S. 263 (1974); Curtis v. Loether. 415 U.S.

189 (1974); Meeker v. Ambassador Oil Corp.. 375 U.S.

160 (1963); Schoenthal v. Irving Trust Co.. 287 U.S. 92

(1932); Scott v. Neely. 140 U.S. 358, 360 (1891); Buzard

v. Houston. 119 U.S. 451, 454 (1886); Baylis v. Travelers’

Insurance Co.. 113 U.S. 316 (1885); Killian v.

35

Ebbinghaus, 110 U.S. 246, 248-249 (1884); Webster v.

Reid, 52 U.S. 437 (1850); Lewis v. Cocks. 90 U.S. 70, 71

(1874); Hodges v. Easton. 106 U.S. 408 (1882).22

As recently as last Term, this Court once again

applied this longstanding rule. In Granfinanciera S.A. v.

Nordberg, 109 S.Ct. 2782 (1989), the bankruptcy court

denied the petitioners’ request for a trial by jury,

conducted a bench trial, and entered findings and a

judgment against the petitioners. Id. at 2787. The

district court and court of appeals affirmed the

22 Other than the Fourth Circuit, all courts of appeals to

have addressed this question have also treated Seventh Amendment

violations as reversible per se. See. e.g„ Marshak v. Tonetti. 813

F.2d 13 (1st Cir. 1987); Amoco Oil Co. v. Torcomian. 722 F.2d 1099

(3d Cir. 1983); EEOC v. Cony Jamestown Corp.. 719 F.2d 1219 (3d

Cir. 1983); Lewis v. Thigpen. 767 F.2d 252 (5th Cir. 1985); Matter

of Merrill, 594 F.2d 1064 (5th Cir. 1979); Hildebrand v. Bd. of

Trustees of Michigan State Univ,. 607 F.2d 705 (6th Cir. 1979);

United States v. One 1976 Mercedes Benz. 618 F.2d 453 (7th Cir.

1980) ; Bibbs v. Jim Lynch Cadillac. Inc.. 653 F.2d 316 (8th Cir.

1981) ; Davis & Cox v. Summa Corp.. 751 F.2d 1507 (9th Cir. 1985);

Palmer v. United States. 652 F.2d 893 (9th Cir. 1981); United States

v. State of New Mexico. 642 F.2d 397 (10th Cir. 1981); Hall v.

Sharpe, 812 F.2d 644 (11th Cir. 1987); Sibley v. Fulton DeKalb

Collection Service. 677 F.2d 830 (11th Cir. 1982).

36

bankruptcy judge’s findings.

This Court concluded that the petitioners had been

denied their rights under the Seventh Amendment. Id.

at 2789-2800. Having reached that conclusion, the Court

held that "the Seventh Amendment entitles petitioners to

the jury trial they requested," id. at 2802, reversed the

judgment of the court of appeals, and remanded for

further proceedings, presumably including the jury trial

petitioners had wrongly been denied. Notably, this Court

accorded no weight whatsoever to the bankruptcy court’s

factual findings. Nor, of course, did it direct the court of

appeals to review those improperly entered findings for

correctness. In short, unlike the Fourth Circuit in Lytle’s

case, this Court in Granfinanciera did not hold that

petitioner’s Seventh Amendment claims were precluded

by the decision in the bench trial.

This Court took the same approach in Tull v. United

37

States. 481 U.S. 412 (1987). In that case, the district

court denied Tull’s timely demand for a jury trial in a

suit seeking civil penalties under the Clean Water Act,

conducted a 15-day bench trial, entered findings against

Tull, and imposed substantial fines. Id. at 415. This

Court concluded that Tull had "a constitutional right to a

jury trial to determine his liability on the legal claims," id.

at 425, and remanded for him to be afforded a trial by

jury, id. at 427. Again, in direct contrast to the approach

used by the Fourth Circuit in Lytle’s case, this Court in

Tull afforded no weight whatsoever to the factual

findings entered after the bench trial.23

23 Of particular salience, Tull also involved issues which were

properly assigned to the judge rather than the jury. See 481 U.S. at

425-27 (size of civil fine). But this Court did not find that the

judge’s proper participation in the last stage of the proceeding

immunized his erroneous appropriation of the jury’s role, even

though, in adjudicating the penalty, the judge necessarily revisited

many of the factual issues involved in the finding of liability.

Similarly, the fact that the judge in this case was the

appropriate factfinder on Lytle’s Title VII claims should not

immunize his unwarranted appropriation of the jury’s role in

38

Of this Court’s earlier cases, Meeker Oil v.

Ambassador Oil Corp.. 375 U.S. 160 (1963) (per curiam),

represents a particularly decisive rejection of the Fourth

Circuit’s position. In Beacon Theatres, Inc, v. Westover,

359 U.S. 500 (1959), a case which came before this Court

on a petition for a writ of mandamus, the Court held

that when the pleadings raise both legal and equitable

issues, and a jury trial has been timely requested, the

legal claims must be tried first before a jury, lest a

premature non-jury decision on the equitable claims

preclude a jury trial on those legal issues. Id. at 508-11.

In Meeker, the trial judge, in violation of Beacon

Theatres, decided the equitable claims first, and then

relied on his own decision in favor of defendants to deny

plaintiffs a jury trial, or any other relief, on their legal

claims. The Tenth Circuit affirmed. 308 F.2d 875 (10th

determining Lytle’s § 1981 claims.

39

Cir. 1962). The petition for certiorari in Meeker

challenged ”[t]he error of the Court of Appeals in

holding that the petitioners were in any way estopped or

prohibited from contesting" their legal claims.24 This

Court granted certiorari, and after briefing and argument

reversed the Tenth Circuit per curiam, citing Beacon

Theatres and Dairy Queen. Inc, v. Wood. 369 U.S. 469

(1962).

In all significant respects, the present case is Meeker.

Here, too, the court of appeals has relied on the district

court’s findings on a plaintiffs equitable claims to justify

not presenting legal claims raised in the same action to

the jury. The fact that the district court here dismissed

Lytle’s legal claims before the bench trial, rather than

simply holding them in abeyance pending the outcome of

24 Petition for Writ of Certiorari, October Term 1963, No.

46, p. 5.

40

the bench trial, does not alter the conclusion that the

district court’s errors denied the plaintiff his Seventh

Amendment rights and must be reversed.

B. A Violation of the Seventh Amendment. Like

Other Errors Which Result in the Wrong

Entity Finding the Facts, Is Subject To

Reversal Per Se

This Court has repeatedly held that when "the wrong

entity" has conducted a trial over the objection of a

litigant, reversal is the required appellate response

"regardless of how overwhelming] the evidence . . .

Rose v. Clark. 478 U.S. 570, 578 (1986) (judge cannot

direct verdict for conviction). This principle lies at the

heart of the Court’s decision last Term in Lauro Lines

S.R.L. v. Chasser. 109 S.Ct. 1976 (1989). In Chasser.

respondent sued petitioner in the Southern District of

New York, over petitioner’s objection that a forum-

selection clause on respondent’s ticket required all suits

41

to be brought in Naples, Italy. The Court held that the

denial of petitioner’s motion to dismiss on the basis of

the forum-selection clause was not immediately

appealable. It stated that "[p]etitioner’s claim that it may

be sued only in Naples, while not perfectly secured by

appeal is adequately vindicable at that stage — surely as

effectively vindicable as a claim that the trial court lacked

personal jurisdiction over the defendant . . . ." Id. at

1979. The clear import of the Court’s analysis is that, if

the forum-selection clause was violated, any verdict

obtained in the Southern District will have to be set

aside, regardless of whether the evidence would support

it, because such a verdict will have been obtained from a

factfinder not entitled to adjudicate the claims presented.

The perspective underlying Chasser is reflected in a

wide array of cases in this Court which have rejected the

assumption that the participation of an incorrect

42

factfinder is irrelevant if a proper factfinder could have

reached the same result.25 Cf.. e.g.. Gomez v. United

States. 109 S.Ct. 2237 (1989) (when magistrate, rather

than judge, presided over jury selection, reversal per se is

required regardless of overwhelming evidence of guilt to

support jury verdict); Lilieberg v. Health Services

Acquisition C om . 108 S.Ct. 2194, 2206 n. 16 (1988)

(when judge should have recused himself under 28 U.S.C.

§ 455, new trial was required even though court of

appeals held that his findings of fact had not been clearly

erroneous); Aetna Life Ins. Co. v. Lavoie. 475 U.S. 813,

825-28 (1986) (when judge should have disqualified

25 In any event, the clearly erroneous standard of Rule 52(a)

applied by the court of appeals, see App. 10a-13a, simply cannot be

appropriate to this kind of case. The Fourth Circuit did not decide

that a jury could not or would not have found for Lytle. All its

Rule 52(a) analysis determined was that a jury was not required as

a matter of law to have done so, and thus that the judge’s findings

for the defendant were not wholly unsupportable. This Court has

never held, in the case of a constitutional violation, that the

appropriate standard of review is sufficiency of the evidence.

43

himself, reversal was required without regard to whether

court would have decided the same way in the absence

of the judge); Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217,

225 (1946) (verdict of jury selected from venire from

which daily wage earners had improperly been excluded

had to be set aside regardless of whether plaintiff was in

any way prejudiced by its decision); Stevens v. Nichols,

130 U.S. 230 (1889) (where matter was improperly

removed from state to federal court the latter’s judgment

after trial would be reversed for trial by state court);

Flemming v. Nestor, 363 U.S. 603, 606-607 (1960) (where

a statute mandates a three-judge court, judgment entered

by a single judge must be reversed and remanded for

44

trial before a three-judge court, and consideration of the

merits is precluded).

m . THE COURTS BELOW ERRED IN APPLYING

PRINCIPLES OF COLLATERAL ESTOPPEL TO

THIS CASE

The linchpin of the Fourth Circuit’s analysis was its

fundamentally flawed reading of this Court’s opinion in

Parklane Hosiery Co. v. Shore. 439 U.S. 322 (1979). Not

only did the court of appeals misread Parklane Hosiery,

but its interpretation would in fact fail to serve the

interests in judicial economy embodied in the doctrine of

collateral estoppel.26

26 The Fourth Circuit declined to apply the collateral

estoppel rule, announced in Ritter v. Mount St. Mary’s Colleee. 814

F.2d 986 (4th Cir. 1987), cert, denied. 108 S. Ct. (1987), and

followed by the panel in the instant case, in Swentek v. USAir, 830

F.2d 552, 559 (4th Cir. 1987). See also, Keller v. Prince George’s

County, 827 F.2d 952 (4th Cir. 1987) (applying the traditional rule

that jury' trial claims may be reviewed despite an intervening decision

on the issues by a trial judge, but without referring to Ritter). But

cf. Dwver v. Smith, 867 F.2d 184, 192 (4th Cir. 1989) (noting

inconsistency both within and without circuit, but holding that Ritter

45

A. Parklane Hosiery Does Not Apply to this

Case

The question presented in Parklane Hosiery was

"whether a party who has had issues of fact adjudicated

adversely to it in an equitable action may be collaterally

estopped from relitigating the same issues before a jury

in a subsequent legal action brought against it by a new

party." 439 U.S. at 324 (emphasis added). Parklane

Hosiery Company was the defendant in two lawsuits: the

first, an equitable action by the SEC; the second, a

damages action by its stockholders. The question was

whether the findings entered in the SEC’s non-jury trial,27

preclusion rule is binding in the circuit).

27 In concluding that collateral estoppel was permitted (not,

contrary to the Fourth Circuit’s rule in this case, that it was

required, see 439 U.S. at 331), the Court expressly noted that ”[t]he

petitioners did not have a right to a jury trial in the equitable

injunctive action brought by the SEC." 439 U.S. at 338 n. 24. Thus,

Parklane Hosiery rests on the premise that the first proceeding was

decided in a proper forum. Cf. Pennover v. Neff. 95 U.S. (5 Otto)

46

and affirmed on appeal, id. at 325, could bind Parklane

Hosiery in the later damages action. The Court

answered that question in the affirmative.

Parklane Hosiery clearly says nothing about whether

the denial of the right to trial by jury is reviewable on

direct appeal. Thus, Parklane Hosiery in no way

undermines the force of the Meeker-Tull-Granfinanciera

line of cases. Indeed, application of collateral estoppel

presumes "litigation [which] proceeds through preliminary

stages, generally matures at trial, and produces a

judgment, to which, after appeal, the binding finality of

res judicata and collateral estoppel will attach." Arizona

v. California. 460 U.S. 605, 619 (1983) (emphasis added).

As courts and commentators have recognized, there is a

vast "difference between correction of procedural errors

714 (1877) (when a prior judgment was obtained in an improper

forum, collateral estoppel is inappropriate).

47

on appeal in a single lawsuit and the refusal to inquire

into possible errors when a prior judgment is offered to

support preclusion." 18 Wright, Miller & Cooper,

Federal Practice and Procedure § 4418 (1989 Supp.) at

104 (footnote omitted); see Roebuck v. Drexel

University, 852 F.2d 715, 738 (3d Cir. 1988); Volk v.

Coler. 845 F.2d 1422, 1437 (7th Cir. 1988) (same); Wade

v. Orange County Sheriffs Office. 844 F.2d 951, 954-55

(2d Cir. 1988); Hussein v. Oshkosh Motor Truck Co.. 816

F.2d 348 (7th Cir. 1987) (same); Bouchet v. National

Urban League. 730 F.2d 799 (D.C.Cir. 1984) (same).

See also, Williams v. Cerberonics. Inc.. 871 F.2d 452, 463

(4th Cir. 1989) (Phillips, J., dissenting).28

28 The appellant in Bouchet argued that the district judge

had improperly dismissed her legal claims, and then resolved against

her the similar issues raised by her equitable claims. Writing for the

panel in that case, then-Judge Scalia explained that not only was the

appellant entitled to a jury trial on her legal claims but the

erroneous denial of her

law claims and the consequent denial of her demand for

jury trial would infect the disposition of her [equitable]

48

Thus, as the Seventh Circuit noted in Hussein, a case

whose procedural posture was identical to that of the

present case:

We believe that the present case presents

a substantially different situation than that before

the Supreme Court in Parklane. Here, there is

no earlier valid judgment . . . .

It is hardly "needless litigation" to reverse

a judgment on the ground that the plaintiff was

denied his right to a jury trial through no fault

of his own solely because of the error of the trial

court. It is inappropriate to apply collateral

estoppel to preclude review of an issue on which

the appellant could not have previously sought

r e v ie w .............. The burden on judicial

administration is no more than in other

situations in which legal error is committed and

claim as well, since most if not all of its elements would

have been presented to the wrong trier of fact. Not only

would a jury trial on her tort claims be required, but the

[equitable] judgment -- even if otherwise valid — would

have to be vacated, and the whole case retried, giving

preclusive effect to all findings of fact by the jury.

730 F.2d at 803-04.

The Fourth Circuit has expressly rejected then-Judge Scalia’s

reasoning: "The Bouchet proposition is . . . set forth without

reference to Parklane. despite the clear relevance of that case to the

issues presented. We find th[is] lower court opinio[n] unpersuasive

. . . ." Ritter. 814 F.2d at 991.

49

a retrial is required . . . . We cannot sanction

an application of collateral estoppel which would

permit findings made by a court . . . to bar

further litigation of a legal issue . . . when those

findings were made only because the district

court erroneously dismissed the plaintiffs legal

claim. To permit such an application would

allow the district court to accomplish by error

what Beacon Theatres otherwise prohibits it

from doing.

816 F.2d at 355-57.

Under the Fourth Circuit’s approach, the narrow

Katchen exception29 would swallow up the broad Meeker

Oil-Beacon Theatres-Dairv Queen rule. Faced with cases

raising both legal and equitable claims, it would be the

rare judge indeed who would not try the equitable claims

first. Conducting the bench trial first would avoid the '

expenses and delays associated with jury trials. It would

obviate the need for the kind of evidentiary rulings and

In Katchen v. Landv. 382 U.S. 323 (1966), the Court

held that the Seventh Amendment is not violated by limiting trial to

the court in a specialized bankruptcy scheme.

50

instructions that attend jury trials. And it would save the

judge from facing the vast majority of post-trial motions

for a judgment n.o.v. or for a new trial. Moreover, the

preclusion afforded those bench rulings means that a trial

court faces no costs in denying the right to a jury: even

if the Seventh Amendment right was violated, the trial

judge will not be required ever to conduct a jury trial.

In short, the Fourth Circuit has created a powerful

inducement for trial courts to violate the Seventh

Amendment.

The holding in Parklane Hosiery was clearly not

intended to create a perverse incentive for lower courts

to violate the Seventh Amendment. Indeed, the Court’s

approving citation of Beacon Theatres’ general prudential

rule and the discussion of the limited situations under

which that rule should not be followed, see 439 U.S. at

334-35 (discussing Katchen v. Landv, 382 U.S. 323

51

(1966)), show that Parklane Hosiery cannot be read to

eliminate Seventh Amendment rights whenever bench

trials have occurred.

B. The Fourth Circuit’s Approach Would in Fact

Undermine the Interest in Judicial Economy

that the Doctrine of Collateral Estoppel Is

Intended to Serve

The Seventh Amendment clearly is not a provision

whose violation can be rendered harmless in the normal

course of events by subsequent proceedings. Cf. Midland

Asphalt Corp. v. United States. 109 S.Ct. 1494 (1989).

Thus, the Fourth Circuit’s rule cannot be read to bar ah

appellate review of Seventh Amendment claims. But if

review of final judgments is barred, then appellate review

must necessarily occur at some interlocutory phase of the

litigation — either (1) through mandamus proceedings

prior to trial, see, e.g.. Gulfstream Aerospace v.

52

Mavacamus Corp.. 109 S.Ct. 1133, 1143 n. 13 (1988) (an

"order that deprives a party of the right to trial by jury is

reversible by mandamus"); Beacon Theatres. Inc, v.

Westover. 359 U.S. 500, 510-11 (1959) (same), or (2)

through application of the collateral order doctrine of

Cohen v. Beneficial Industrial Loan Corp.. 337 U.S. 541

(1949).30

In either event, the result is the same: appellate

30 Until now, the collateral order doctrine has been held

inapplicable to denials of jury trials precisely because wrongful

denials of jury trials could be corrected on appeal. See Morgantown

v. Royal Insurance Co.. 337 U.S. 264 (1949); Western Elec. Co. v.

Milgro Electronic Corp. 573 F.2d 255, 256-57 (5th Cir. 1978)

(specifically tying that conclusion to the nonapplicability of collateral

estoppel when the Seventh Amendment had been violated).

But under the Fourth Circuit rule, denials of jury demands will

fall under the collateral order doctrine, since they will satisfy all

three prongs of the Cohen rule. See, e.e.. Lauro Lines, 109 S.Ct. at

1978 (setting out the three conditions); Coopers & Lybrand v.

Livesav, 437 U.S. 463, 468 (1978) (same). First, such orders will

"conclusively determine the disputed question," id., namely, whether

the litigant has the right to trial before a jury. Second, they will

"resolve an important issue completely separate from the merits of

the action," id., since who the factfinder should be is in no sense

equivalent to what the facts are. Finally, the very nature of the

Fourth Circuit rule is to hold such orders entirely "unreviewable on

appeal from final judgment." Id.

53

courts will continue to face claims of Seventh

Amendment violations. The primary effect of the Fourth

Circuit’s rule will be to require interlocutory appellate

review, and to prompt appeals in ah cases in which a

jury demand has been denied (and not only in cases

where the party demanding the jury subsequently loses at

the bench trial),31 since parties whose demands have

been denied will no longer be able to appeal that denial

as part of an appeal from a generally adverse final

31 The availability of collateral review or mandamus does not,

however, mean that an aggrieved party who elects not to utilize

those avenues of review, but instead awaits conclusion of the district

court proceedings, loses the right of review. 9 Wright & Miller,

Federal Practice and Procedure: Civil § 2322 at p. 105 (1971). The

failure to take an immediate appeal of the denial of a Seventh

Amendment right has never been construed as a waiver of that

constitutional right. Rule 38, Fed. R. Civ. P., specifies what

constitutes waiver of the right: failure to make a timely demand.

And such waiver is not to be implied lightly. See, e.g.. Aetna

Insurance Co. v. Kennedy, 301 U.S. 389, 393 (1937) ("the right of

jury trial is fundamental [and] courts [must] indulge every reasonable

presumption against waiver"); Hall v. Sharpe. 812 F.2d 644, 649

(11th Cir. 1987); Gargiulo v, Delsole. 769 F.2d 77, 79 (2d Cir. 1985)

("plaintiffs were not required to walk out of the courtroom rather

than proceed with the bench trial in order to preserve [their right of

appeal]").

54

judgment. Thus, the Fourth Circuit’s rule will have the

ironic consequence of increasing the burden on courts of

appeals.

In short, the Fourth Circuit’s rule does not even

serve the goals it purports to further. In light of the

tremendous costs it imposes on a fundamental

constitutional right, it is entirely unjustified.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the decision below should

be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

RONALD L. ELLIS

ERIC SCHNAPPER

JUDITH REED*

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

55

August, 1989

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

PENDA D. HAIR

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

Suite 301

1275 K Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682 1300

PAMELA S. KARLAN

University of Virginia

School of Law

Charlottesville, VA 22901

(804) 924-7810

Attorneys for Petitioner

* Counsel of Record

56