Help Your Child Attend Integrated School... NOW

Reports

January 1, 1965

4 pages

Cite this item

-

Division of Legal Information and Community Service, DLICS Reports. Help Your Child Attend Integrated School... NOW, 1965. 6161083d-799b-ef11-8a69-6045bdfe0091. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fa63427e-309e-4287-8783-087891586693/help-your-child-attend-integrated-school-now. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

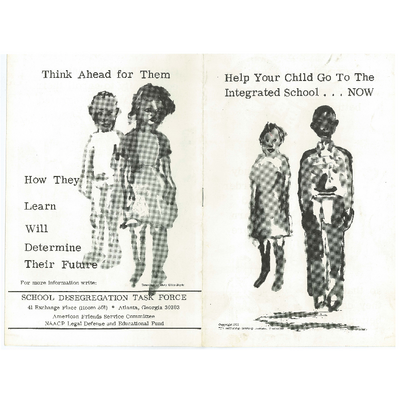

Think Ahead for Them

How The

Learn

Will

Determine

For more information write:

SCHOOL DESEGREGATION

41 Exchange Place (Room 501) * Atlanta, Georgia 30303

American Friends Service Committee

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund

I

Help Your Child Go To The

Integrated School •.. NOW

It-• .... ~·~.

They

will read

better

*

so that

they c'an get

better jobs

study

harder

and

learn

In time they will gain

confidence

to move in the total world

WHO CAN GO?

All children

all grades

should

attempt

to

enroll

The procedures vary from school

district to school district, so

GET THE FACTS

Contact the

School Desegregation

Task ~rce or your

Superintendent of

Education

I

\

What do you have to do?

Get the

Read your

,,

during

registration

period

Follow the procedures

for enrolling your children

Write us

'

PLAN AHEAD!

Get your child's birth certificate

(a certified copy is needed)

Begin to set aside money

now for sch ol supplies

KNOW YOUR RIGHTS I

Your child has a right to an education without

discrimination. This means:

No segregation in school

No segregation on buses

No segregation in sports or

other school activities

..

Get EVERYONE in your

community to enroll their

children at the integrated

scho"

, The Mom(· the BETTER